Allen v. State Board of Elections Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. State Board of Elections Jurisdictional Statement, 1967. 2be24792-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6746594e-d847-4e4d-8348-eaa17ae5e3a5/allen-v-state-board-of-elections-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

s> ! / I

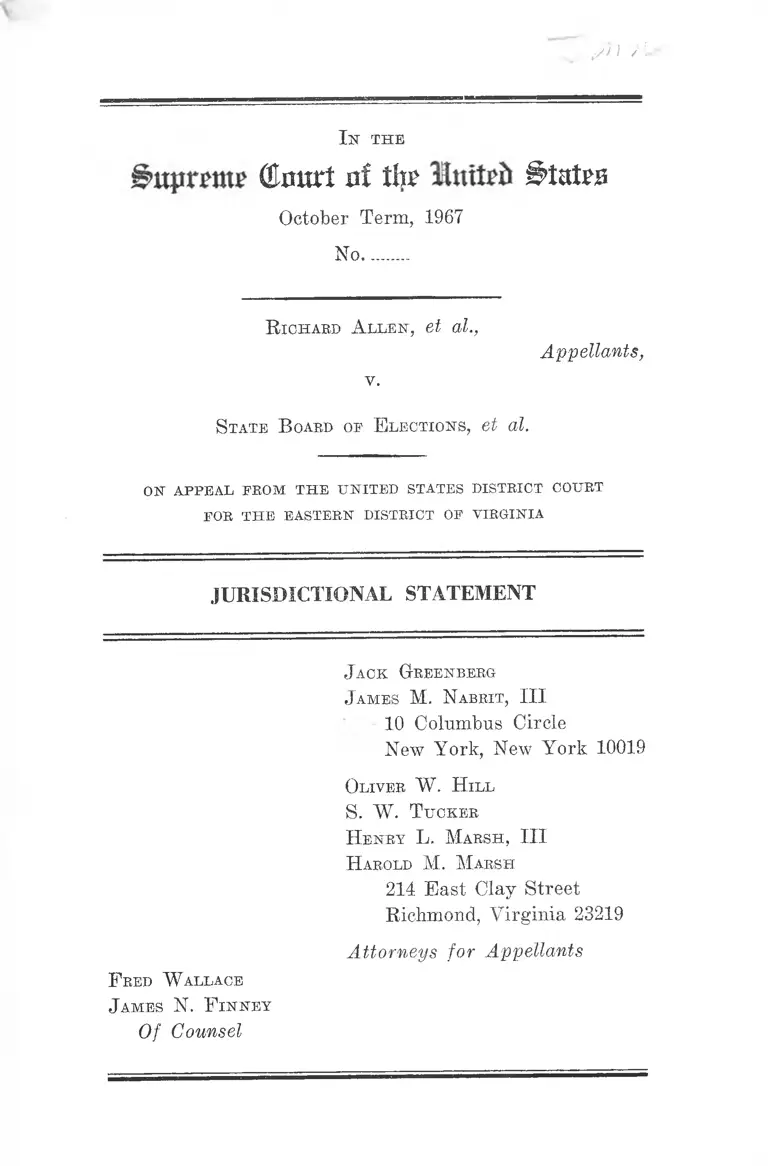

I n t h e

(Emort ni te States

October Term, 1967

No.......

R ichard A l l e n , et al.,

v.

Appellants,

S tate B oard oe E lections, et al.

ON APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, I I I

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Oliver W , H ill

S. W . T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , I I I

H arold M. M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellants

F red W allace

J ames N. F in n ey

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below.................................................- ............. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Questions Presented ...................................................... 9

Statement of the Case .................................................... 10

The Questions Are Substantial:

Introduction ............................................................. 15

I. The Handwriting Requirement of Virginia Code

Section 24-252 Was Suspended by the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 ............- ................................ 18

II. Virginia Code Section 24-252 Hoes Not Afford

Appellants, VTho Are Unable to Spell Accurately

and Write Legibly, Equal Protection for the

Secrecy of Their Ballots..................................... 25

C onclusion ...................................... -............................................... 30

A ppen d ix :

Memorandum Opinion......................-......-........... — la

Judgment ................................. -............................. 2a

11

PAGE

Table of Cases:

Bates v. Little Bock, 361 U.S. 516................................27-28

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89 ................ ................... 22

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651 ................................ 15

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218........... ................. 25

Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528 .......................2,15, 29

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U.S.

713 ............................................................................... 2

In re Massey, 45 F. 629 (E.D. Ark. 1890) ..................... 26

Johnson v. Clark, 25 F. Supp. 285 (N.D. Tex. 1938) .... 26

Lassiter v. Northampton Election Bd., 360 U.S. 45___ 14

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145...... ................ 24

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 .......................... 16, 27

Pearson v. Board of Supervisors of Brunswick County,

91 Va. 334, 21 S.E. 483 (1895) .......... 23

Query v. United States, 316 U.S. 486 ......................... 2

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 ................................... 15

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 ............ ...................... 27, 28

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 ..... ...12,15, 20

Stratton v. St. Louis-Southwestern. Ry. Co., 282 U.S. 10 2

Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60 ................_____............ 16,27

Taylor v. Bleakley, 55 Kan. 1, 39 P. 1045 (1895) ........... 27

Ill

PAGE

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 ............................ 19

United States v. Executive Com. of Dem. P. of Greene

County, Ala., 254 F. Supp. 543 (N.D. & S.D. Ala.

1966) ........................................................................... 24

United States v. Mosely, 238 U.S. 383 ........................ 15,19

Voorhes v. Dempsey, 231 F. Supp. 975 (D. Conn. 1964) 26

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 ................................ 15

Zwickler v. Koota, No. 29, Oct. Term, 1967 ................. 16

Statutes:

Constitution of the United States, Art. I, section 4,

clause 1 ....................................................................... 4, 21

2 U.S.C. §9...............................................................5, 26, 27

28 U.S.C. §1253 ........................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343, 2201 ....................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §2101 (b) .......................... .............................. 2

28 U.S.C. §§2281, 2284 .............................. 2

42 U.S.C. §1971(a)(2)(B) ............................................ 22

42 U.S.C. §1971(a) (3) (A) ........................ 22

42 U.S.C. §1971 (e) ................. 22

42 U.S.C. §1973, Voting Rights Act of 1965 .............. 2

42 U.S.C. §1973b ..................................... 12

42 U.S.C. §1973!)(a) ....... ....5-6,17,18

42 U.S.C. §1973b(b) ............ 7,12

42 U.S.C. §1973b(c) ........ 7,14,18

IV

PAGE

42 U.S.C. §1973c .........................................................7_8; 20

42 IT.S.C. §1973i(a) ....................................................... 9? 19

42 IT.S.C. §1973/(c) (1) ..................................................9 ,18

Act of February 28, 1871, 16 Stat. 440 .... ................... 26

Constitution of Virginia, § 20 ........................ 17 21

Constitution of Virginia, §27...................................4 ,17; 26

Constitution of Virginia, §28.............. 4f 17

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-25 ................... ..... .............. 12

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-30 ........... ........... ...... 16

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-68 ......... ........... ................17; 21

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-71 ............... ....................... 17

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-251 ........... .................... 3? 13; 23

Code of Virginia 1950, §24-252 ..... ......2, 3, 9,10,11,14,18,

19, 20, 21, 25, 28

Other Authorities:

30 Fed. Reg. 9897 ............ ..................... ...... i 2 17

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 3d Sess. (1871) ..... ............. 26, 27

1 st t h e

(&mxt of % In itio States

October Term, 1967

No.............

R ichard A l l e n , et al.,

V.

Appellants,

S tate B oard of E lections, et al.

on appeal from t h e u n ited states district court

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the final judgment of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

entered on May 2, 1967, denying their prayers for injunc

tive relief and a declaratory judgment and dismissing the

case, and submit this statement to show that the Supreme

Court of the United States has jurisdiction of the appeal

and that substantial questions are presented.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Virginia is reported at 268 F. Supp. 218. Copies

of the Opinion and Judgment of the District Court are

attached hereto, Appendix pp. la to 9a.

2

Jurisdiction

This is an action for injunctive and declaratory relief

in which the jurisdiction of the District Court was invoked

under 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343, 2201 to enforce rights pro

tected by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendent and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C.

§§1973, et seq.). The complaint sought to restrain the

Virginia State Board of Elections and other election offi

cials from enforcing a state statute, Va. Code §24-252,

insofar as it authorized the officials not to count write-in

votes unless they were inserted on the ballot in the voters’

own handwriting. A statutory three-judge court was con

vened pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§2281, 2284 (R. 20).

A final judgment of the court below denying injunctive

relief and dismissing the case was entered May 2, 1967

(R. 90). Timely notice of appeal to this Court was filed

in the court below on June 29, 1967 (28 U.S.C. §2101 (b))

(R. 91). The District Court, by order dated August 24,

1967, extended the time for docketing the appeal in this

Court to September 28, 1967 (R. 96).

The jurisdiction of this Court to review this decision

by direct appeal is conferred by 28 U.S.C. §1253. This

Court’s jurisdiction is sustained by Harman v. Forssenius,

380 U.S. 528, 532-533; see also, Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor

Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U.S. 713; Query v. United States, 316

U.S. 486; Stratton v. St. Louis-Southwestern By. Co.,

282 U.S. 10.

3

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This ease involves the validity of Code of Virginia,

1950, §24-252 (Code of Va. 1964 Repl. Vol. 5, p. 271),

which provides as follows:

§24-252. Insertion of names on ballots.—At all elec

tions except primary elections it shall be lawful for

any voter to place on the official ballot the name of

any person in his own handwriting thereon and to

vote for such other person for any office for which he

may desire to vote and mark the same by a check (y )

or cross ( X or +) mark or a line (—) immediately

preceding the name inserted. Provided, however, that

nothing contained in this section shall affect the oper

ation of §24-251 of the Code of Virginia. No ballot,

with a name or names placed thereon in violation of

this section, shall be counted for such person. (Code

1919, §162; 1936, p. 278; 1952, c. 581; 1962, c. 536.)

2. The following additional provisions are material to

an understanding of the issues presented.

(a) Code of Virginia, §24-251:

§24-251. Judges or others to assist certain voters.—

Any person registered prior to the first of January,

nineteen hundred and four, and any person registered

thereafter who is physically unable to prepare his

ballot without aid, may, if he so requests, be aided

in the preparation of his ballot by one of the judges

of election designated by himself, and any person

registered, who is blind, may, if he so requests, be

aided in the preparation of his ballot by a person of

his choice. The judge of election, or other person, so

4

designated shall assist the elector in the preparation

of his ballot in accordance with his instructions, but

the judge or other person shall not enter the booth

with the voter unless requested by him, and shall not

in any manner divulge or indicate, by signs or other

wise, the name or names of the person or persons for

whom any elector shall vote. For a corrupt violation

of any of the provisions of this section, the person so

violating shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and

be confined in jail not less than one nor more than

twelve months. (Code 1919, §166; 1946, p. 316; 1950,

p. 230.)

(b) Constitution of Virginia, §§27, 28:

“§27. Method of Voting.—All elections by the people

shall be by ballot; * * *

“The ballot box shall be kept in public view during

all elections, and shall not be opened, nor the ballots

canvassed or counted, in secret.

So far as consistent with the provisions of this Con

stitution, the absolute secrecy of the ballot shall be

maintained.”

“§28. Ballots.—The General Assembly shall provide

for ballots without any distinguishing mark or symbol,

for the use in all State, county, city and other elections

by the people, and the form thereof shall be the same

in all places where any such election is held. All ballots

shall contain the names of the candidates and of the

offices to be filled, in clear print and in due and orderly

succession; but any voter may erase any name and

insert another.”

(c) Constitution of the United States, Art. I, Sec

tion 4, Clause 1:

S ection 4. Clause 1. The Times, Places and Man

ner of holding Elections for Senators and Repre-

5

sentatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the

Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time

by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to

the Places of chusing Senators.

(d) Title 2, U.S.C., §9:

§9. Voting for Representatives.—All votes for Rep

resentatives in Congress must be by written or printed

ballot, or voting machine the use of which has been

duly authorized by the State law; and all votes re

ceived or recorded contrary to this section shall be

of no effect. (R. S. §27; Feb. 14, 1899, c. 154, 30 Stat.

836.)

(e) Title 42, U.S.C., §1973b(a), (b), (c ):

%1973b. Suspension of the use of tests or devices in

determining eligibility to vote—Action by state or

political subdivision for declaratory judgment of no

denial or abridgement; three-judge district court; ap

peal to Supreme Court; retention of jurisdiction by

three-judge court

(a) To assure that the right of citizens of the

United States to vote is not denied or abridged on

account of race or color, no citizen shall be denied

the right to vote in any Federal, State, or local elec

tion because of his failure to comply with any test

or device in any State with respect to which the

determinations have been made under subsection (b)

of this section or in any political subdivision with

respect to which such determinations have been made

as a separate unit, unless the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia in an action for a

declaratory judgment brought by such State or sub

division against the United States has determined

that no such test or device has been used during the

6

five years preceding the filing of the action for the

purpose or with the effect of denying or abridging

the right to vote on account of race or color: Pro

vided, That no such declaratory judgment shall issue

with respect to any plaintiff for a period of five

years after the entry of a final judgment of any

court of the United States, other than the denial

of a declaratory judgment under this section, whether

entered prior to or after the enactment of this sub

chapter, determining that denials or abridgments

of the right to vote on account of race or color

through the use of such tests or devices have oc

curred anywhere in the territory of such plaintiff.

An action pursuant to this subsection shall be

heard and determined by a court of three judges in

accordance with the provisions of section 2284 of

Title 28 and any appeal shall lie to the Supreme

Court. The court shall retain jurisdiction of any ac

tion pursuant to this subsection for five years after

judgment and shall reopen the action upon motion of

the Attorney General alleging that a test or device

has been used for the purpose or with the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of race or color.

If the Attorney General determines that he has

no reason to believe that any such test or device has

been used during the five years preceding the filing

of the action for the purpose or with the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account of

race or color, he shall consent to the entry of such,

judgment.

Required factual determinations necessary to allow

suspension of compliance with tests and devices;

publication in Federal Register

7

(b) The provisions of subsection (a) of this sec

tion shall apply in any State or in any political

subdivision of a state which (1) the Attorney Gen

eral determines maintained on November 1, 1964,

any test or device, and with respect to which (2) the

Director of the Census determines that less than

50 per centum of the persons of voting age residing

therein were registered on November 1, 1964, or

that less than 50 per centum of such persons voted

in the presidential election of November 1964.

A determination or certification of the Attorney

General or of the Director of the Census under this

section or under section 1973d or 1973k of this title

shall not be reviewable in any court and shall be

effective upon publication in the Federal Register.

Definition of test or device

(c) The phrase “test or device” shall mean any

requirement that a person as a prerequisite for

voting or registration for voting (1) demonstrate

the ability to read, write, understand, or interpret

any matter, (2) demonstrate any educational achieve

ment or his knowledge of any particular subject,

(3) possess good moral character, or (4) prove his

qualifications by the voucher of registered voters

or members of any other class.

(f) Title 42, U.S.C., §1973c:

§1973c. Alteration of voting qualifications and

procedures; action by state or political subdivision

for declaratory judgment of no denial or abridgement

of voting rights; three-judge district court; appeal to

Supreme Court

Whenever a State or political subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in sec-

8

tion 1973b(a) of this title are in effect shall enact

or seek to administer any voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure with respect to voting different from that

in force or effect on November 1, 1964, such State

or subdivision may institute an action in the United

States District Court for the District of Columbia

for a declaratory judgment that such qualification,

prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure does

not have the purpose and will not have the effect

of denying or abridging the right to vote on account

of race or color, and unless and until the court en

ters such judgment no person shall be denied the

right to vote for failure to comply with such qualifi

cation, prerequisite, standard, practice, or proce

dure: Provided, That such qualification, prerequi

site, standard, practice, or procedure may be en

forced without such proceeding if the qualification,

prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure has

been submitted by the chief legal officer or other

appropriate official of such State or subdivision to

the Attorney G-eneral and the Attorney General has

not interposed an objection within sixty days after

such submission, except that neither the Attorney

General’s failure to object nor a declaratory judg

ment entered under this section shall bar a subse

quent action to enjoin enforcement of such qualifi

cation, prerequisite, standard, practice, or proce

dure. Any action under this section shall be heard

and determined by a court of three judges in ac

cordance with the provisions of section 2284 of

Title 28 and any appeal shall lie to the Supreme

Court. Pub.L. 89-110, §5, Aug. 6, 1965, 79 Stat. 439.

9

(g) Title 42, U.S.C., 1973Z(c)(l):

Definitions

(c) (1) The terms “vote” or “voting” shall include

all action necessary to make a vote effective in any

primary, special, or general election, including, but

not limited to, registration, listing pursuant to this

sub-chapter, or other action required by law prereq

uisite to voting, casting a ballot, and having such

ballot counted properly and included in the appro

priate totals of votes cast with respect to candidates

for public or party office and propositions for which

votes are received in an election.

(h) Title 42, U.S.C., §1973i(a):

§1973i. Prohibited acts—Failure or refusal to per

mit casting or tabulation of vote

(a) No person acting under color of law shall fail

or refuse to permit any person to vote who is en

titled to vote under any provision of this sub

chapter or is otherwise qualified to vote, or willfully

fail or refuse to tabulate, count, and report such

person’s vote.

Questions Presented

I.

Whether the requirement of Virginia Code section 24-252,

that write-in votes be in the voters’ own handwriting, is

in conflict with the provisions of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 forbidding denial of the right to vote for failure

to comply with “tests or devices” as defined in the Act?

10

II.

Whether Virginia Code section 24-252 unconstitutionally

discriminates against illiterates by failing to provide equal

protection for the secrecy of their ballots in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States?

Statement of the Case

This litigation involves the claim of certain illiterate

registered voters, newly eligible to vote because of the pro

visions of the Voting Eights Act of 1965, that Virginia

election law unlawfully discriminated against them. They

object to the lack of any procedures for protecting the

privacy and secrecy of illiterates’ write-in votes from dis

closure to state officials. The issues arose in the context

of a general election for members of the House of Repre-

sentatives which was held November 8, 1966, in Virginia’s

Fourth Congressional District. Rep. Watkins M. Abbitt,

the incumbent, and Edward J. Silverman were the candi

dates listed on the ballot. The plaintiff-appellants were

supporters of S. W. Tucker, a well-known civil rights at

torney in Virginia who was a write-in candidate for Con

gress. The plaintiffs, as the court below found, were

“unable to spell accurately or to write legibly” (268 F.

Supp. at 219). They sought to vote for S. W. Tucker by

pasting a sticker, upon which his name was printed, on

the official ballot under the names of the listed candidates,

and then making the appropriate marking preceding his

name (R. 9-17). The defendant election officials did not

count the votes for Tucker on ballots marked with the

Tucker stickers. They disallowed the ballots, relying on

Virginia Code section 24-252, which permits the insertion

of names on general election ballots in the voter’s “own

11

handwriting,” and provides that ballots with a name placed

thereon “in violation” of the section shall not be counted

for such person. According to the statement published

by the defendant Board of Elections, the 1966 congres

sional election was won by Rep. Abbitt with 45,226 votes;

Mr. Silverman drew 14,827 votes, and 7,907 write-in votes

were counted (R. 61, Pi’s Exhibit No. 2, p. 9).

This action was commenced November 28, 1966, shortly

after the election. Plaintiffs prayed in their complaint,

inter alia, for a judgment declaring Virginia Code section

24-252 invalid and in conflict with the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and also the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, insofar as the Virginia law “purports

to deny any voter, solely because of his inability to write,

the privilege of casting a secret ballot for a person whose

name is not printed on the official ballots and having such

ballot counted in the appropriate returns; . . .” (R. 7);

and prayed that the court enjoin defendants from failing

and refusing to count votes inserted on official ballots “by

means other than handwriting” in the November 1966

election, and such votes “hereafter given” in future elec

tions (R. 8). By their subsequent motion for summary

judgment, appellants indicated that they mainly sought

relief for future elections and not for the 1966 election

(R. 69).

A statutory three-judge district court was convened to

hear and determine the case (R. 20-21). The plaintiffs

submitted requests for admissions under Rule 36 (R. 38-

47), none of which were denied under oath by the defen

dants (R. 49-56). The defendant State Board of Elections

had the statutory duty to supervise and coordinate the

work of county and city electoral boards to obtain uni

formity in their practices and proceedings and to make

rules and regulations for their functioning. (Code of

12

Virginia, 1950, §24-25.) The other defendants were judges

of election and clerks of election in precincts in which the

plaintiffs resided. The requests for admissions developed

the facts with respect to the use of Tucker stickers by

illiterate voters in several areas where paper ballots were

used, and that such votes were not counted. The court

below treated the facts as undisputed (268 F. Supp. at

219).

By way of defense, the State Board of Elections offered

in evidence several letters or bulletins which it had dis

tributed to local voting officials during the summer of 1965

after the passage of the Voting Bights Act. One letter to

all voting registrars advised that Virginia’s prior registra

tion procedures could no longer be used, and that if appli

cants were unable to complete registration forms the

registrar should orally examine the applicant and assist

him in completing the registration forms (B. 65). The

Voting Bights Act provisions which prompted the above

mentioned letter were those which temporarily forbade the

use of literacy tests or devices in states to which the Act

was made applicable. (42 U.S.C. §1973b.) And, of course,

the Voting Bights Act, designed to end racial discrimina

tion in voting, was applicable in Virginia.1

1 The designation of Virginia under §1973b(b) was published in the

Federal Register on August 7, 1965, 30 Fed. Reg. 9897. in describing the

history which led to passage of the Act this Court said in South Carolina

v. Katzenbaeh, 383 U.S. 301, 310-311:

Meanwhile, beginning in 1890, the States of Alabama, Georgia,

Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia

enacted tests still in use which were specifically designed to prevent

Negroes from voting. Typically, they made the ability to read and

write a registration qualification and also required completion of a

registration form. These laws were based on the fact that as of 1890

in each of the named States, more than two-thirds of the adult Negroes

were illiterate while less than one-quarter of the adult whites were un

able to read or write. (Footnotes omitted.)

13

The State Board of Elections also introduced a bulletin

to election judges dated October 15, 1965 (R. 68). The

bulletin was supplied to voting registrars and secretaries

of electoral boards for them to distribute to judges of

elections (R. 66-67). The bulletin stated:

B ulletin- F rom S tate B oard of E lections

To A ll J udges oe E l e c t io n :

On August 6, 1965, the “Voting Rights Act of 1965”

enacted by the Congress of the United States became

effective and is now in force in Virginia. Under the

provisions of this Act, any person qualified to vote

in the General Election to be held November 2, 1965,

who is unable to mark or cast his ballot, in whole or

in part, because of a lack of literacy (in addition to

any of the reasons set forth in Section 24-251 of the

Virginia Code) shall, if he so requests, be aided in the

preparation of his ballot by one of the judges of elec

tion selected by the voter. The judge of election shall

assist the voter, upon his request, in the preparation

of his ballot in accordance with the voter’s instruc

tions, and shall not in any manner divulge or indicate,

by signs or otherwise, the name or names of the per

son or persons for whom any voter shall vote.

These instructions also apply to precincts in which

voting machines are used.

There was no evidence in the record indicating to what

extent, if any, the public was advised of the rule and policy

set forth in the bulletin to election judges. Neither is

there anything in the record indicating whether or not any

instructions similar to those stated in the 1965 bulletin

were reissued at the time of the 1966 congressional election

or whether voters had any way of knowing that election

14

judges were instructed to assist illiterates in completing

their ballots. The court below merely found that “The

Attorney General of Virginia asserted, and the plaintiffs

do not controvert, that these instructions apply while the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 is effective in the state.” (268

F. Supp. at 221.)

The district court denied the relief prayed and dis

missed the case. The court rejected appellants’ claim of

unconstitutional discrimination against illiterates, citing

the decision in Lassiter v. Northampton Election Bd., 360

U.S. 45, for the proposition that discrimination between

illiterate and literate voters does not violate the Four

teenth Amendment. (268 F. Supp. at 220.) The court also

rejected appellants’ argument that Virginia Code section

24-252 was rendered invalid by the Voting Rights Act of

1965. The court held that the Virginia requirement that

the write-in candidate’s name be inserted in the voter’s

own handwriting was “not a test or device defined in 42

U.S.C. §1973b(c).” (268 F. Supp. at 221.) The court said

that the requirement did not prevent the appellants from

registering and voting, and that the Board of Elections’

bulletin provided for them to be assisted by election judges

in casting ballots.

15

The Questions Are Substantial

Introduction

At stake in this ease are the claims of educationally de

prived voters, who cannot spell accurately or write legibly,

that they have the same right to vote for the candidates of

their choice, to have their votes counted, and to protect the

secrecy of their ballots from state election judges as do

other voters.

The questions presented are of public importance from

several points of view. First, of course, the right to vote

and have one’s vote counted is at stake. The Court has

long recognized the constitutional protection for such rights

(Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651; United States v.

Mosely, 238 U.S. 383), and has on innumerable occasions

stated the importance of protecting the right to vote. See,

e.g., Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370, calling the

right to vote important “because preservative of all rights.”

And see Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555; Harman v.

Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528.

Second, the case involves the rights of numerous persons

newly enfranchised by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, who

had long been disenfranchised by a host of discriminatory

measures in Virginia and other states,2 and presents serious

questions regarding the interpretation and application of

that important federal law. It is appropriate that this

Court give guidance by construing the law.

Third, the case involves the secrecy of the ballot. The

Court has not, to our knowledge, had a previous occasion

to deal with threats to the secrecy of the ballot, but it has,

2 See, e.g., Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528; South Carolina v.

Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 310-311 (quoted supra, note 1).

16

of course, dealt with the kindred question of the right to

anonymity in political expression, Talley v. California, 362

U.S. 60; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 TJ.S. 449, and has

agreed to hear a case this term involving attempted sup

pression of anonymous election literature. Zwickler v.

Koota, No. 29, Oct. Term 1967. The right of a secret ballot

is of considerable practical moment for political dissidents,

such as appellants, who were supporters of a write-in can

didate opposing an incumbent who had served ten consecu

tive terms.3 In such circumstances the right to keep one’s

vote secret from a state election judge belonging to the

dominant political group is of more than abstract im

portance. Virginia election judges are appointed by local

electoral boards under a statute which directs that repre

sentation be given to the two leading political parties in the

last election, Va. Code §24-30.

This controversy arises from the fact that Virginia, hav

ing been required to permit illiterates to vote by the Voting

Eights Act of 1965 because the state permitted only white

illiterates to vote in the past, failed to provide a method

to protect the secrecy of illiterates’ votes from state officials,

and disallowed the votes of appellant who sought to vote

secretly for a write-in candidate by inserting paper stickers

bearing the candidate’s name, on their ballots. By way of

introduction to the issue presented, we point out several

undisputed matters. First, it is agreed that in accordance

with the Voting Eights Act of 1965 appellants are entitled

to vote in their respective counties, notwithstanding their

illiteracy. Until 1965 Virginia excluded illiterates from

voting; the state Constitution and statutes required that

applicants for voting registration, except those physically

3 The Hon. Watkins Abbitt, Representative from Virginia’s Fourth

Congressional District has served in office since the 80th Congress.

17

unable, must apply in their “own handwriting.”4 But those

provisions were suspended by the federal Voting Bights

Act of 1965 which became applicable in Virginia August

7, 1965. 42 U.S.C. §1973b(a); 30 Fed. Beg. 9897. Second,

the facts are not in dispute, and it was found by the court

below that appellants were unable to write, that they did

insert votes for a write-in candidate, S. W. Tucker, by using

gummed stickers or labels bearing his name, and that their

votes were not tabulated or counted for Tucker. Third, the

background of Virginia law relevant to the case includes

(1) a state constitutional provision that elections “shall be

by ballot” and that “the absolute secrecy of the ballot shall

be maintained” (Const, of Va., §27); and (2) a state con

stitutional provision permitting write-in votes (Const, of

Va., §28).

4 Constitution of Virginia, section 20, provides in part, as follows:

§ 20. Who may register.—Every citizen of the United States, hav

ing the qualifications of age and residence required in section eight

een, shall be entitled to register, provided:

Second. That, unless physically unable, he make application to

register in his own handwriting, on a form which may be provided

by the registration officer, without aid, suggestion, or other memo

randum, in the presence of the registration officer, stating therein his

name, age, date and place of birth, residence and occupation at the

time and for the one year next preceding, and whether he has previ

ously voted, and, if so, the State, county, and precinct in which he

voted last; and, * * *”

The provision was implemented by statutes. Virginia Code of 1950, sec

tions 24-68, 24-71.

18

I

The Handwriting Requirement Of Virginia Code Sec

tion 24-252 Was Suspended By The Voting Rights Act

Of 1965.

It is appellants’ submission that the Virginia Statute

which authorized the election officials not to count their

ballots (Code section 24-252) was suspended on August 7,

1965 when Virginia was brought under the coverage of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965. They seek an injunction and a

declaratory judgment holding that statute invalid and re

straining its enforcement on this statutory ground as well

as on the constitutional grounds argued in Part II, infra.

Appellants’ constitutional argument involves the secrecy of

the ballot. The Voting Rights Act argument does not turn

on the secrecy issue but does strike at the state law which

was used to invalidate appellants’ ballots and thus supports

their right to vote effectively and in secret.

Section 4(a) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§1973b(a) (quoted supra pp. 5-6) provides that “no citizen

shall be denied the right to vote . . . because of his failure

to comply with any test or device.” Section 4(c) of the

Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973b(c) (supra p. 7), defines the phrase

“test or device” to mean “any requirement that a person

as a prerequisite for voting or registration for voting (1)

demonstrate the ability to read, write, understand, or in

terpret any matter, (2) demonstrate any educational

achievement or his knowledge of any particular subject.. . .”

Section 14(c) (1) of the act, 42 U.S.C. §19731(c) (1) (quoted

at p. 9 above), defines the terms “vote” and “voting” to

“include all action necessary to make a vote effective . . .

including, but not limited to registration, listing pursuant

to this Act, or other action required by law prerequisite to

19

voting, casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted

properly and included in the appropriate totals of votes

cast . . (emphasis added). Finally, section 11(a) of the

Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973i(a) (quoted above, p. 9), prohibits

a refusal to count the vote of anyone who is entitled to vote

under the Act.

The court below held that the requirement of Ya. Code

section 24-252, that write-in votes be inserted in the voters

“own handwriting,” was not a “test or device” within the

meaning of section 4 of the Voting Eights Act. The court

seemed to rest its conclusion on the assertion that “ [t’Jhe

requirement of [Ya. Code §24-252] did not preclude the

plaintiffs from registering or from voting” (268 F. Supp.

at 221-222). This answer, we submit, is plainly insufficient.

The appellants were precluded from voting, if “voting” is

defined as in the Voting Eights Act and in normal usage to

mean casting an effective ballot and having it counted. As

indicated above, section 14(c)(1) of the Voting Eights Act

of 1965 includes everything necessary to have a vote counted

within the term “voting.” Moreover, this usage is consistent

with that in decisions of this Court over a long period of

years. See United States v. Mosely, 238 U.S. 383; United

States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 315.

The opinion below seeks, in part, to avoid the thrust of

appellants’ argument that the handwriting requirement is

a “test or device” under Section 4 of the Voting Eights Act

by pointing to the fact that on October 15, 1965 the Board

of Elections ordered election judges to aid illiterates. But

this argument is not responsive to the question whether

Section 24-252 was suspended as a matter of law on August

7, 1965 several months before the election board’s reaction.

If Section 24-252 was suspended, no basis for disallowing

appellants’ votes remains and they are entitled to an order

enjoining its enforcement. There is no ground for conclud-

20

mg that Section 24-252 was only partially suspended, so as

to save the last sentence which allows votes not to be

counted.

The Court below did not discuss another question which

was necessarily raised by its view of the October 15th bulle

tin as a sort of amendment of Virginia’s voting laws. If

this bulletin in effect replaced a suspended statute then the

procedure set forth in the bulletin was also suspended auto

matically by another provision of the Voting Eights Act of

1965, e.g. Section 5. That provision suspends all new voting

regulations in states covered by the Act pending review by

federal authorities to determine whether their use would

be racially discriminatory. South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301, 334-335. The new Virginia procedure comes

within Section 5 which refers to a “standard, practice or

procedure with respect to voting different from that in force

or effect on November 1, 1964” (42 U.S.C. §1973c). There

is no allegation by the State that the October 15th bulletin

was approved by the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia, or was submitted to the Attorney

General without objection as provided in Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act. Thus, in accord with Section 5 “no per

son shall be denied the right to vote for failure to comply

with such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice or

procedure.”

Two additional comments should be made about the

Board of Election’s new procedure set forth in the October

15, 1965 bulletin. At first blush it seems to be an attempt

to conform to and obey the Voting Eights Act, but this rec

ord shows that in practice it conditions the rights of illiter

ates to vote upon their willingness to divulge their votes to

state election judges. The constitutionality of that condi

tion is explored further in argument II below. Second, we

submit that the reasonableness of the procedures must be

21

appraised from the standpoint of the illiterate voters.

There is not any showing in this record that they had any

way of even knowing about the new procedures set up in

the election board’s internal bulletin.

Application of the Voting- Eights Act to suspend the

handwriting requirement of Va. Code section 24-252, is

fully in accord with the Congressional purpose, and should

be adopted to support the policy of the Act. We urge four

separate considerations which support the desirability of a

ruling that Section 24-252 was suspended.

First, an interpretation of the Act to permit the hand

writing requirement to continue in effect creates a plainly

anomalous result, considering that it is conceded that the

handwriting requirements for voter registration (contained

in Virginia Constitution section 20, and in Virginia Code

section 24-68) are suspended by the Voting Rights Act.

The handwriting requirement of Code section 24-252, is

not materially different from that in the other provisions

and should also be suspended. Nothing in the Voting Rights

Act supports the result of suspending two of the handwrit

ing requirement laws and not suspending the third.

Second, this controversy involves the “manner of holding

elections for Senators and Representatives,” a matter which

under the Constitution of the United States (Article I, sec

tion 4, clause 1) is committed to the ultimate control of the

Congress. Congress is fully authorized under the Constitu

tion to “make or alter” rules regarding the manner of con

ducting a federal election. A federal law intended to be

protective of the right to vote in federal elections should

be liberally construed as against a state enactment which

narrowly and technically restricts the right to cast effective

votes. As the whole area of federal election mechanics is

committed to Congressional control there is no problem of

infringement of States’ rights underlying the controversy.

22

Third, the policy against rules which thwart the right to

vote on the basis of the technicalities of state law has been

stated very plainly by the Congress. The provisions of 42

U.S.C. §1971 (a) (2) (B), forbid the denial of the right to

vote “because of an error or omission on any record or

paper relating to any application, registration, or other

act requisite to voting, if such error or omission is not

material in determining whether such individual is quali

fied under state law to vote in such election.” 5 There is no

justification, in terms of administrative convenience, for

disallowing ballots on such an overly technical ground as

that used by appellees. As the Court said a few terms ago

in another context involving a threat to the right to vote

in Carrington v. Bash, 380 U.S. 89, 96:

We deal here with matters close to the core of our

constitutional system. “The right. . . to choose,” United

States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 314, that this Court has

been so zealous to protect, means, at the least, that

States may not casually deprive a class of individuals

of the vote because of some remote administrative

benefit to the State. Oyarna v. California, 332 U.S. 633.

Fourth, the appellants’ use of stickers to indicate their

votes was entirely reasonable under the circumstances and

the States’ invalidation of their ballots was unreasonable.

The Voting Rights Act should be construed to block un

reasonable measures which disfranchise voters where it

may be reasonably construed to accomplish this end. The

appellants were presented with a dilemma in the 1966

election; they face the same problem in future contests.

They desired to vote write-in ballots for S. W. Tucker.

6 The right to “vote,” in this statute also, includes “all action necessary

to make a vote effective,” including having the ballot “counted and in

cluded in the appropriate totals of votes cast.” See 42 U.S.C. § 1971(a)

(3) (A), incorporating' the definition in 42 U.S.C. § 1971(e).

23

They also desired to keep their ballots secret. Virginia

law, on the face of the statute books, still absolutely for

bade them to vote except in their own handwriting. The

statutes themselves made no exception for illiterates to be

aided even by election judges. An Election Board bulletin

directed election judges to aid them on request. But the

Election Board had no power to enact any criminal law

which might be a deterrent to a voting judge breaching a

voter’s confidence, and did not purport to do so. Thus, il

literates were not offered even the limited protections which

were offered to handicapped and blind voters by Virginia

Code section 24-251.6 Voters who could not read had the

problem, which physically handicapped voters did not have,

of not having any available means of knowing whether or

not the election judge was faithfully carrying out their

directions. Blind voters were offered the option of being

assisted by a trusted friend; appellants were not given this

choice. Voters with physical handicaps other than blindness

could at least observe and comprehend the actions of the

election judges who cast their votes. Only illiterate voters

were placed entirely at the mercy of election judges who

were not even bound by any statute of the state to follow

their instructions or keep their confidence. It is no sufficient

answer here to say that it is presumed that the election

6 The existence of such criminal sanctions was thought by a Virginia

court to be essential to the validity of a similar 19th century Virginia

law which was challenged because of the threat to the secret ballot.

Pearson v. Board of Supervisors of Brunswick County, 91 Va. 334, 21

S.E. 483 (1895). In Pearson, the Court sustained an 1894 Virginia law

which included a provision that at the request of an elector physically or

educationally unable to vote a special constable could aid him in preparing

his ballot. The law was attacked as an infringement of the secret ballot.

The Court acknowledged “that very great power is placed in the hands

of this special constable, that a great trust is reported in him, and that

wherever confidence is given it is liable to be abused” (Pearson, supra,

21 S.E. at 485). But, the Court sustained the law relying on the fact

that the constables were “under the sanction of an oath” and wmre subject

to “severe penalties” for violating their duties.

24

judges will function honestly and do their duties. The

Voting Rights Act of 1965 was necessary precisely because

all other efforts to halt racial discrimination by voting of

ficials had failed. The Virginia statutes give election offi

cials no directions and prescribe no duties for them with

respect to aiding illiterates. Laws and procedures which

gave state officials total discretion were a principal means

of preventing Negroes from voting. Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 152-153. After the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 was enacted, the United States found it necessary

in some communities for federal observers to watch state

officials while they assist illiterates in voting. See United

States v. Executive Com. of Dem. P. of Greene Co., Ala.,

254 F. Supp. 543 (N2D. and S.D. Ala. 1966).

Appellants chose a reasonable method of solving their

problem by using stickers to indicate their votes. As the

court below acknowledged in its opinion, this is a method

approved in a number of state courts (268 F. Supp. at 220).

Of course, the state might prescribe some method other than

the use of stickers, or permitting voters to be assisted by

persons they choose, that would afford protection for the

secrecy of the ballots of persons unable to write legibly.

The complaint here is simply that Virgina has not furnished

any such method. The Voting Rights Act should be con

strued so as to aid appellants in voting effectively and

secretly. A finding that the Virginia handwriting require

ment is suspended provides that protection for appellants.

As appellants made clear in the court below, they seek

relief to protect their votes in future elections (R. 7-8, 69,

73). The future application of the Virginia rule will have

a chilling effect on political participation by all illiterate

persons who oppose the dominant political organization in

an area. Illiterates who support unpopular candidates are

the ones who will feel the pinch of Virginia’s law. It will

25

take no great courage for an illiterate to seek help from

an election judge when he wishes to vote for the State’s

dominant political forces. It may be another matter en

tirely when the illiterate supporter of a dissident minority

candidate arrives at the polls in some areas of the Fourth

Congressional District such as Prince Edward County

Virginia. Cf. Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218.

Thus, for all these reasons, in addition to the plain lan

guage of the statute, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 should

be construed to invalidate Virginia’s statute permitting

write-in ballots, to be discounted unless they are in “hand

writing.”

II

Virginia Code Section 24>252 Does Not Alford Appel

lants, Who Are Unable To Spell Accurately And Write

Legibly, Equal Protection For The Secrecy Of Their

Ballots.

Appellants seek protection for the secrecy of their bal

lots in federal elections. They object to a Virginia statute,

which has been applied to deny them the opportunity to

vote effectively for write-in candidates unless they are will

ing to disclose their votes to state election judges. They

urge that the State denies them equal protection by failing

to afford them any of the number of available procedures

by which they might receive the same protections for the

secrecy of their ballots which Virginia gives to voters who

are able to write legibly and spell accurately. Indeed, they

are not even given the protection available for blind voters,

e.g., the right to be aided by someone other than an election

judge if they choose.

As we have pointed out earlier, Virginia’s Constitution

protects the secrecy of the ballot (Constitution of Virginia,

26

section 27), and for literate voters there is, in the words

of the Constitution, “absolute secrecy.” The right to a

secret ballot also finds support in relevant federal law.

Congress enacted the law now codified as 2 U.S.C. §9 nearly

100 years ago. This section (quoted supra at p. 5) requir

ing that all votes in congressional elections be “by written

or printed ballot” has been construed to require a secret

ballot. See Johnson v. Clark, 25 F. Supp. 285 (N.D. Tex.

1938); cf. Voorhes v. Dempsey, 231 F. Supp. 975 (D. Conn.

1964).

It seems rather clear that when the Congress enacted 2

U.S.C. §9, in 1871, it intended to provide a secret ballot as

opposed to the viva voce method of voting. During the

debates on the Act (the provision was originally section 19

of the Act of February 28, 1871, 16 Stat. 440, c. 99, §19)

Congressman Bingham said: “What objection can there be

to the ballot? . . . It occurs to me that there is but a single

State in the Union to-day that tolerates the old method of

voting viva voce.” Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3d Sess. 1284

(1871). Secrecy was clearly a part of the contemporary

19th Century understanding of the word ballot as evidenced

by judicial usage. For example, as the Court stated in In

re Massey, 45 F. 629, 634-635 (E.D. Ark. 1890):

That the word “ballot” implies secrecy is unquestioned,

and, if it was provided that the election shall be by

ballot, and nothing further was said, then it would be

without doubt the right of the elector to have the

secrecy of the ballot preserved from impertinent or

improper inspection . . .

The objective of the 41st Congress was to introduce the

authority of the federal government into the fight to

secure and preserve the integrity of federal elections. It

could not but have concurred in the conclusion which had

27

been reached by the majority of State legislatures that

secrecy, as the fundamentally distinguishable characteristic

of voting by ballot, was an efficacious tool to enlist in the

war against a variety of electoral evils being practiced

throughout the country.7

Moreover, the right of a secret ballot is obviously bound

up in a close relationship with the right of privacy of as

sociation for the advancement of political beliefs which is

plainly protected by the Constitution. N.A.A.C.P. v. Ala

bama, 357 U.S. 449; Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60;

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479; Bates v. Littl-e Rock, 361

7 The attitude of the majority of states on the efficacy of secrecy has

been succinctly summarized:

“Absolute secrecy in voting reaches effectively a great number of evils,

including violence, intimidation, bribery and corrupt practice, dicta

tion by employers or organizations, the fear of ridicule and dislike or

of social or commerce injury—in fact all coercive and improper in

fluence of every sort depending on a knowledge of the voter’s political

action.” Taylor v. Bleakley, 55 Kan. 1, 39 P. 1045 (1895).

That the 41st Congress was confronted with many of these evils emerges

from the debate on 2 U.S.C. § 9:

“A few words as to its [the act’s] necessity . . . we all know that

Ku Klux outrages have been committed, not only in North Carolina

. . . but in other states of the South; and that in more than one city

of this Union enormous frauds have been perpetrated upon the ballot

box . . .” Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 3d Sess. 1275 (1871) (Remarks

of Rep. Churchill).

“Tour ‘repeaters,’ your ‘ballot-box staffers,’ your ‘Ku Klux Klans,’

intimidation of loyal citizens—these and numberless other agencies

of wrong and fraud on the ballot, overturning the power and will

of the people, will continue to run riot in the land unless prevented

by some such legislation as this . . . We have seen the elector’s of

states defrauded out of the honest expression of their choice of candi

dates at the ballot-box, and in others we have seen similar results

from terrorism, intimidation, and violence.” Id. at 1276 (Remarks

of Rep. Lawrence).

“The object of the bill is very manifest, and in my judgment just

as it is manifest. I t is to prevent, under the law and by virtue of the

law, any violation of the rights of the citizen by fraud or corruption

on the part of any one to whom is intrusted the conduct of the elec

tion or the registration of voters.” Id. at 1284 (Remarks of Rep.

Bingham).

28

IT.S. 516. Accordingly, any state invasion of the privacy of

the ballot must be justified by some compelling showing.

“Where there is a significant encroachment upon personal

liberty the State may prevail only upon showing a subordi

nating interest which is compelling.” Bates v. Little Rock,

361 U.S. 516, 524. “ [Ejven though the governmental pur

pose be legitimate and substantial, that purpose cannot be

pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal

liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved.”

Shelton v. Tucker, supra, 364 U.S. at 488.

Quite plainly, the secret ballot is a valuable privilege

which cannot be denied or infringed on a discriminatory

basis. The Virginia discrimination against illiterates serves

no overriding governmental purpose which can justify the

differential treatment. It should be noted that the Virginia

statutes contain no specific and direct prohibition against

the use of voting stickers. The appellees found the prohibi

tion implied from the requirement that write-in candidates’

names be inserted in the voter’s own handwriting, Va. Code

§24-252. But the Virginia election officials are apparently

quite prepared to accept the handwriting of an election

judge in lieu of the voter’s handwriting, just as the Virginia

laws accepts the handwriting of any friend brought into the

voting booth by a blind voter. The state’s legislative and

administrative scheme shows no consistent concern for

whose handwriting appears on the ballot; only a concern

that names be inserted in someone’s handwriting. But there

has been no showing or argument forthcoming from the

State which demonstrates why the State has such a great

interest in the insertion being done in handwriting as op

posed to printing or some other method, or why the sub

scription for illiterates must be done in the handwriting of

an election judge and not by some other person who is not

a state official. The State has not carried the burden of

29

demonstrating that the handwriting requirement is so “nec

essary to the proper administration of its election laws”

that the interest may be elevated above the constitutionally

protected right of a citizen to vote and have his vote

counted. Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528, 543. The

handwriting requirement is merely a remaining vestige of

Virginia’s long-lived system of enforcing a literacy pre

requisite for voting, a system designed from its inception

to prevent Negroes from voting. Harman v. Forssenius,

supra, 380 U.S. at 543.

The opinion below states that illiterates have no Four

teenth Amendment right to vote and apparently concluded

from this proposition that discrimination against illiterates

does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment (268 F. Supp.

at 220). But illiterates now have a right to register and

vote in Virginia under the Voting Rights Act, which was

made applicable to the State under the congressional for

mula designating those states where literacy tests had been

used to discriminate against Negroes. An unjustifiable dis

crimination among those equally entitled to vote under the

operative law establishing voting qualifications is nonethe

less a denial of equal protection of the laws whatever might

be the rule if voting qualifications were different. When

the law affords a right it must be afforded on equal terms.

The State should not be permitted to invade the right of a

secret ballot where there are plainly available methods

which can assure voters’ privacy from state election officials.

30

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that this case presents sub

stantial questions which justify full briefing and plenary

consideration by the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

F eed W allace

J ames N. F in n e y

Of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Oliver W. H ill

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

H arold M. M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Opinion by Butzner, O.j.

UNITED STATES DICTRICT COURT

E . D. V lB G IN IA

R ichm ond D ivision

May 2, 1967

Civ. A. No. 5041

R ichabd A l l e n , L ena W . D u n n , W ashington M oobe,

M cK in l e y D u n n , N oba T yleb, J ames G ilbebt T yleb,

F a n n ie M. B eow n , P atbick H. B bown and J ames

D o n ik en s ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

S tate B oabd oe E lections, M ask Gbizzabd, F obest L a n k -

eobd, B e n ja m in Gb ie e in , R obebt E . Gabnett, J. S.

L ipscomb , T homas B bown a n d P aul B ell ,

Defendants.

M emoeandum op t h e C oubt

B efo re B byan a n d W in t e b , Circuit Judges, an d B u tzn ee ,

District Judge.

B u t zn e e , District Judge:

The plaintiffs, registered voters who are unable to

spell accurately or to write legibly, attempted to cast

their votes for a write-in candidate in the 1966 congres

sional election. Each pasted a sticker, upon which the

write-in candidate’s name was printed, on the official ballot

2a

Opinion by Butsner, D.J.

under the names of listed candidates and appropriately

marked the ballot immediately preceding the sticker.

These ballots were not tabulated for the write-in candi

date. Upon these undisputed facts, the plaintiffs seek a

declaratory judgment that the Fourteenth Amendment’s

equal protection clause and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

(42 U.S.C. §1973 et seq.) invalidates §24-252, Code of

Virginia 1950, insofar as this section denies to any voter,

solely because of his inability to write, the privilege of

casting a secret ballot for a candidate whose name is not

printed on the official ballot. The plaintiffs pray that

the defendants be enjoined from refusing to count any

vote because the candidate’s name was inserted on the

official ballot by means other than the voter’s handwriting.

We canclude that the relief sought by the plaintiffs should

be denied.

Pertinent provisions of the Virginia Constitution are:

“§ 27: Method of Voting.—All elections by the

people shall be by ballot; * * *

“The ballot box shall be kept in public view during

all elections, and shall not be opened, nor the ballots

canvassed or counted, in secret.

So far as consistent with the provisions of this

Constitution, the absolute secrecy of the ballot shall

be maintained.”

“§ 28. Ballots.—The General Assembly shall pro

vide for ballots without any distinguishing mark or

symbol, for the use in all State, county, city and other

elections by the people, and the form thereof shall

be the same in all places where any such election is

held. All ballots shall contain the names of the candi-

3a

Opinion by Butzner, D.J.

dates and of the offices to be filled, in clear print and

in due and orderly succession; but any voter may erase

any name and insert another.”

Section 24-252, Code of Virginia 1950, provides:

“Insertion of names on ballots.—At all elections

except primary elections it shall be lawful for any

voter to place on the official ballot the name of any

person in his own handwriting thereon and to vote

for such other person for any office for which he

may desire to vote and mark the same by a check

(V ) or cross (X or +) or a line (—) immediately

preceding the name inserted. Provided, however, that

nothing contained in this section shall affect the op

eration of § 24-251 of the Code of Virginia. No ballot,

with a name or names placed thereon in violation of

this section, shall be counted for such person.”

The propriety of stickers is a matter for legislative,

not judicial determination. Arguments for and against

their use abound. Stickers have been lauded for facilitat

ing voting and denounced as conducive to fraud and con

fusion. Their use has been approved under statutes per

mitting write-ins. Pace v. Hickey, 236 Ark. 792, 370 S.W.

2d 66 (1963); O’Brien v. Board of Elections Comm’rs, 257

Mass. 332, 153 N.E. 553 (1926); Dewalt v. Bartley, 146 Pa.

529, 24 A. 185, 15 L.R.A. 771 (1892); State on Complaint

of Tank v. Anderson, 191 Wis. 538, 211 X.V. 938 (1927).

Illinois forbade their use, Fletcher v. Wall, 172 111. 426,

50 N.E. 230, 40 L.B.A. 617 (1898), and the constitutionality

of this ban has been upheld. Blackman v. Stone, 101 F.2d

500, 504 (7th Cir. 1939).

The plaintiffs’ contention that § 24-252 violates the

Fourteenth Amendment because it discriminates against

4a

Opinion by Butsner, D.J.

illiterates is not supported by authority. To the contrary,

exclusion of illiterate persons from voting, if no other

discrimination is practiced, does not violate the Four

teenth Amendment.

In Lassiter v. Northampton Election Bd., 360 TJ.S. 45,

51, 79 S.Ct. 985, 990, 3 L.Ed.2d 1072 (1959), the Court

said:

“We do not suggest that any standards which a

State desires to adopt may be required of voters. But

there is wide scope for exercise of its jurisdiction.

Residence requirements, age, previous criminal record

* * * are obvious examples indicating factors which a

State may take into consideration in determining the

qualifications of voters. The ability to read and write

likewise has some relation to standards designed to

promote intelligent use of the ballot. Literacy and

illiteracy are neutral on race, creed, color, and sex,

as reports around the world show. Literacy and in

telligence are obviously not synonymous. Illiterate

people may be intelligent voters. Yet in our society

where newspapers, periodicals, books, and other

printed matter canvass and debate campaign issues,

a State might conclude that only those who are

literate should exercise the franchise. * * # It was

said last century in Massachusetts that a literacy

test was designed to insure an ‘independent and in

telligent’ exercise of the right of suffrage. * # * North

Carolina agrees. We do not sit in judgment on the

wisdom of that policy. We cannot say, however, that

it is not an allowable one measured by constitutional

standards.”

5a

Opinion by Butzner, D.J.

Lassiter warns that “ * * * a literacy test, fair on its

face, may be employed to perpetuate that discrimination

which the Fifteenth Amendment was designed to uproot.”

360 XT.S. 53, 79 S.Ct. 991. No evidence has been presented

that Virginia’s prohibition of stickers had been adminis

tered in a discriminatory manner. It has not been used

to disfranchise any class of citizens. We conclude that

§ 24-252 does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment by

discriminating between literate and illiterate voters.

The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the Fifteenth Amendment are not the only

standards by which state legislation governing the fran

chise must be measured. State laws affecting the right

of suffrage must not contravene “ # * # any restriction

that Congress, acting pursuant to its constitutional powers,

has imposed.” Harper v. Virginia Bd. of Elections, 383

IT.S. 663, 665, 86 S.Ct. 1079, 1081, 16 L.Ed.2d 169 (1966);

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 86 S.Ct. 1731, 16

L.Ed.2d 828 (1966). The plaintiffs urge that requiring

the name of the write-in candidate to be inserted in the

voter’s own handwriting violates the Voting Bights Act

of 1965 (42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq.). The constitutionality

of pertinent sections of the Act is not in dispute. Cf. State

of South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 86 S.Ct.

803, 15 L.Ed.2d 769 (1966).

Virginia is subject to the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(b). Until

the state is removed from the Act’s provisions, all tests

or devices for determining eligibility to vote are sus

pended. 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(a).

The plaintiffs rely on these sections of the Act:

42 U.S.C. § 1973b(a):

“ # * * no citizen shall be denied the right to vote

in any Federal, State, or local election because of his

6a

Opinion by Butsner, D.J.

failure to comply with any test or device in any

State * * * .”

42 U.S.C. § 1973b (c):

“The phrase ‘test or device’ shall mean any require

ment that a person as a prerequisite for voting or

registration for voting (1) demonstrate the ability to

read, write, understand, or interpret any matter, (2)

demonstrate any educational achievement or his knowl

edge of any particular subject, (3) possess good moral

character, or (4) prove his qualifications by the

voucher of registered voters or members of any other

class.”

42 U.S.C.A. §1973i(a):

“No person acting under color of law shall fail or

refuse to permit any person to vote who is entitled

to vote under any provision of this subchapter or is

otherwise qualified to vote, or willfully fail or refuse

to tabulate, count, and report such person’s vote.”

Section 24-251, Code of Virginia 1950, authorizes a

judge of election, upon request, to assist a physically

handicapped voter prepare his ballot, and allows a blind

voter to be aided by a person of his choice. The assistants

are enjoined to secrecy. For any corrupt violation of their

duties, they may be punished by confinement in jail for

not less than one nor more than twelve months. No provi

sion was made for helping an illiterate person because

under Virginia law all voters had to demonstrate ability

to read and write.

After the enactment of the Voting Eights Act of 1965,

Virginia directed its registrars to help illiterate persons

7a

Opinion by Butsner, D.J.

register. The Board of Elections recognized that illiterates

might need assistance with their ballots. For this reason,

it instructed all judges of election:

“On August 6, 1965, the ‘Voting Rights Act of

1965’ enacted by the Congress of the United States

became effective and is now in force in Virginia.

Under the provisions of this Act, any person qualified

to vote in the General Election to be held November 2,

1965, who is unable to mark or cast his ballot, in

whole or in part, because of a lack of literacy (in

addition to any of the reasons set forth in Section

24-251 of the Virginia Code) shall, if he so requests,

be aided in the preparation of his ballot by one of

the judges of election selected by the voter. The

judge of election shall assist the voter, upon his

request, in the preparation of his ballot in accordance

with the voter’s instructions, and shall not in any

manner divulge or indicate, by signs or otherwise,

the name or names of the person or persons for whom

any voter shall vote.

These instructions also apply to precincts in which

voting machines are used.”

The Attorney General of Virginia asserted, and the

plaintiffs do not controvert, that these instructions apply

while the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is effective in the

state.

The requirement that a write-in candidate’s name be

inserted in the voter’s handwriting is not a test or device

defined in 42 U.S.C. §1973b(c). The requirement did not

preclude the plaintiffs from registering or from voting.

Under present Virginia statutes and regulations of the

8a

Opinion by Butzner, D.J.

Board of Elections, an illiterate can cast a valid write-in

ballot by enlisting the assistance of a jndge of election.

No evidence was offered that any Judge of election denied

any illiterate voter the confidential assistance to which

he is entitled.

Judgment will be entered for the defendants.

9a

Judgment

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob t h e E astern D istrict of V irginia

R ich m o nd D ivision

Civil Action No. 5041

R ichard A l l e n , L ena W. D u n n , W ashington M oore,

M cK in l e y D u n n , N ora T yler, J ambs G ilbert T yler,

F a n n ie M. B row n , P atrick H. B rown and J ames

D on ik bn s ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

S tate B oard of E lections, M ark Grizzard, F orest L ank

ford, B e n ja m in Gr if f in , R obert E . Garnett, J. S.

L ipscomb, T homas B rown a n d P aul B ell ,

Defendants.

For reasons stated in the opinion of the court this day

filed;

It is A djudged and Ordered th a t th e p ra y e r o f th e p la in

ti f f s ’ co m p la in t is den ied , th e co m p la in t is d ism issed , an d

th e ac tio n is s tr ic k e n fro m th e docket w ith costs tax ed

a g a in s t th e p la in tif fs .

May 2, 1967

/ s / A lbert V. B ryan

United States Circuit Judge

/ s / H arrison W inter

United States Circuit Judge

/ s / J ohn D. B u tzn er , J r.

United States District Judge

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C . - 'C IS ' ' 219