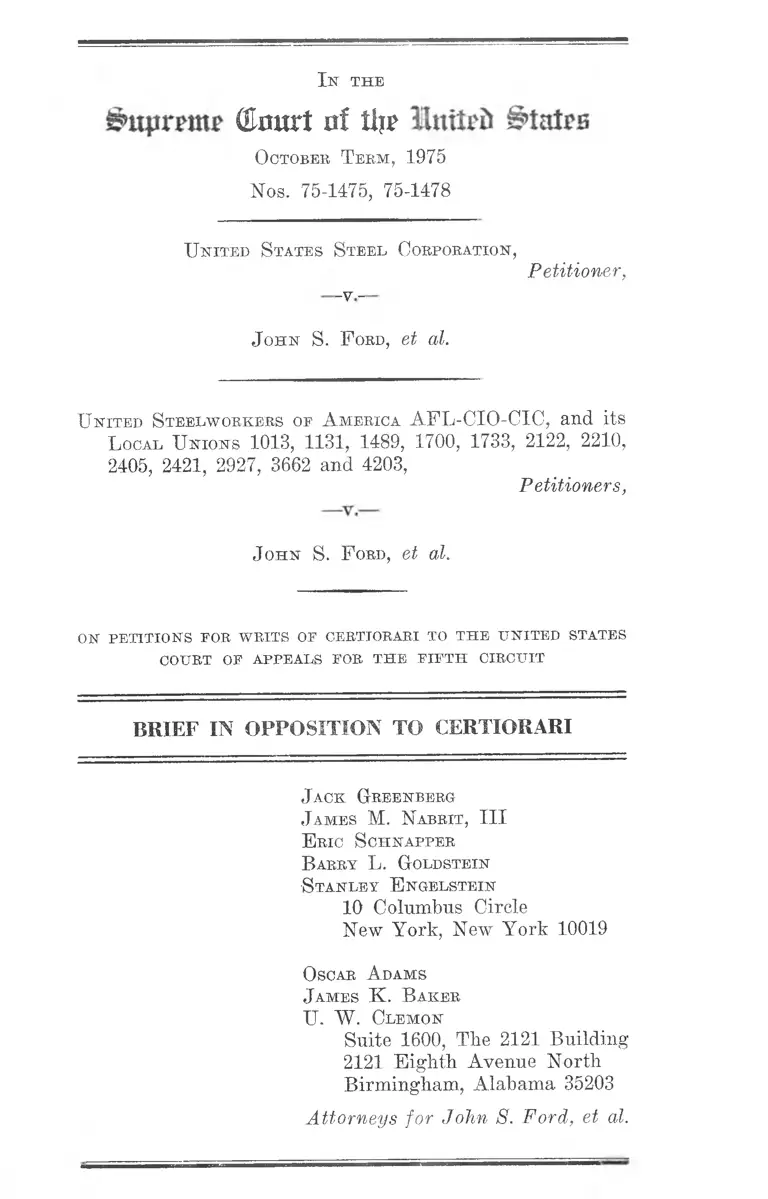

United States Steel Corporation v. Ford Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States Steel Corporation v. Ford Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1975. a516146a-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/674eba02-36b8-4dbf-963f-0a3a969a2272/united-states-steel-corporation-v-ford-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Qlmtrt nf tii?

O ctober T e e m , 1975

Nos. 75-1475, 75-1478

U n it e d S tates S t e e l C orporation ,

Petitioner,

- V -

JoH N S. F ord, et al.

U n it e d S teelw o rk ers of A m erica AFL-CIO-CIC, and i ts

L ocal U n io n s 1013, 1131, 1489, 1700, 1733, 2122, 2210,

2405, 2421, 2927, 3662 and 4203,

Petitioners,

J o h n S. F ord, et al.

ON pe t it io n s fob w r its of certiorari to t h e u n it e d states

court of appea ls for t h e f if t h c ircu it

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abbit , III

E ric S c h n a ppb r

B arry L. G oldstein

■Stanley E n g elstein

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

O scar A dams

J am es K . B aker

U. W. Clem o n

Suite 1600, The 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for John 8. Ford, et al.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statem ent ......... ...................-............................................... 1

Eeasons for Denying the W rit ......................................... 2

1. The Backpay Ruling ............................................. 3

2. Standing of the Named Plaintiff' ..... ................- 4

3. Modification of the Class ..... -............. -......... - ...... 5

4. The Class Action Tolling Rule ----- ---- -............. 6

CoNCLUsioisr ....................-.........—..................................... ...... 8

Appendix .........................- .................... ........... ..................... l a

In t h e

(Emirt of tl|i? Initrib ^tatps

O ctober T e r m , 1975

Nos. 75-1475, 75-1478

U n it e d S tates S te e l Corporation ,

J o h n S . F ord, et al.

Petitioner,

U n ited S teelw o rk ers oe A m erica AFL-CIO-CIC, and its

L ocal U n io n s 1013, 1131, 1489, 1700, 1733, 2122, 2210,

2405, 2421, 2927, 3662 and 4203,

Petitioners,

-- Y.---

J o h n S . F ord, et al.

ON pe t it io n s for w r its of certiorari to t h e u n it e d states

COURT of appeals FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Statement

Tlie district court had found that the defendants Steel

workers and United States Steel Corporation, petitioners

here, had engaged in patterns and practices of racial dis

crimination in employment which required injunctive re

lief designed to remedy the effects of that discrimination

with respect to the seniority and transfer system, train

ing and apprenticeship programs, and selection for plant

protection, clerical and supervisory jobs. (Pet.A18-A41^)

Aeitber the Steelworkers nor U.S. Steel challenged the

district court’s findings of widespread racial discrimina

tion. (See Pet.A77) Eather the Steelworkers and U.S.

Steel have petitioned for review of the Fifth Circuit’s

holding that backpay should be awarded to compensate

those black workers who suffered lost earnings as a re

sult of the discriminatory practices. Additionally, the

Company further petitioned for review of the district

court’s enlargement of the class represented by John S.

Ford et al. to include all the black workers at Fairfield

Works who were not otherwise being represented in a

private class action.

The district court’s enlargement of the Ford class was

not done contemporaneously with the entry of judgment

as U.S. Steel states in its petition. (Pet. at 10). The class

was re-defined in the district court’s decree entered on

May 2, 1973. (Pet.A38) Judgment was not entered by the

district court until August 10, 1973. United States v.

United States Steel Corporation, 6 EPD 8790 (N.D. Ala.

1973). Since neither petitioner included the Judgment of

the district court in the appendix to their petitions, the

respondents have attached it as an appendix to this brief.

(la-4a)

Reasons for Denying the Writ

The six questions presented by U.S. Steel and the three-

part question presented by the Steelworkers challenge two

aspects of the Fifth Circuit’s decision: the reversal of the

district court’s denial of backpay to 2,700 black steelwork

ers who had their employment opportunities restricted by

1 Citations in this form are to the Appendix to the petition for

certiorari filed by United States Steel Corporation in No. 75-1475.

tlie discriminatory practices of the petitioners and the af

firmance of the legality of the district court’s re-definition

of the Ford class.^

1. The Backpay Ruling

The Union in its three-part question and the Company

in its last three questions raise defenses of lack of had

faith, good faith efforts to comply with the law, the un

settled state of the law, the absence of unjust enrichment

to the defendants and the breadth of other affirmative

relief.® No question of law is being raised by these peti

tions that was not settled by this Court in Albemarle Paper

Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). In essence, petitioners

here seek a rehearing of the decision in Albemarle.

Additionally, petitioners argue that the difficulties of

ascertainment of the backpay remedy for individual mem

bers of the class was a lawful basis for the district court’s

̂The Fifth Circuit however vacated the lower court’s definition

of the class and remanded to the lower court to take evidence as

to the class “propriety”, “scope”, “size” and “membership”. The

Fifth Circuit further stated that “the question on remand will be

comprehensive and multifaceted” and suggested that the district

court enter findings of fact in support of its determination. (A

83-84).

® The Union in attempting to argue that the lower courts found

discriminatory steel seniority systems to be lawful under Title VII

misstated the history of that litigation. The Union relies on a

pre-Title VII decision, Whitfield v. United Steelworkers of Amer

ica, but omits its explicit reversal in 1970, Taylor v. Armco Steel

Corporation, 429 P.2d 498 (5th Cir. 1970). Moreover, at the time

when the appeal was argued before the Fifth Circuit in United

States V. H.K. Porter Company, Inc. in April, 1970 “the Court,

from the bench, indicated that major changes in the seniority

and other systems at the plant were required in order to achieve

compliance with Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 . . . ”,

491 P.2d 1105 (1974). Petitioner, in effect, seeks exemption from

liability for backpay under Title VII on the ground that it was

in good faith compliance with pre-Title VII law!

use of its discretion in denying backpay relief for the class.

This is contrary to the rule of this Court in Albemarle

that “given a finding of unlawful discrimination, backpay

should be denied only for reasons, which, if applied gen

erally, would not frustrate the central statutory purposes

of eradicating discrimination throughout the economy and

making persons whole for injuries suffered through past

discrimination.” ̂ (422 U.S. at 421)

2. Standing of the Named Plaintiff

The Company’s challenge to the standing of the named

plaintiff on appeal conflicts with settled law that the cause

of action in a class action survives the mootness of the

claim of the named plaintiff when the issues as to the class

is certain to come before the courts, Sosna v. Iowa, 419

IJ.S. 393 (1975). The instant case satisfies the three cri

teria for the survival of the class action after the satisfac

tion of the named plaintiff’s claim which this Court set

down in Sosna (at 402). It is undisputed that John S.

Ford had standing to sue as the named plaintiff in the

original suit; that the class was certified by the district

court and that the controversy^ is still alive.

On petitioner’s theory it would be possible to scuttle a

class action by simply settling the claim of the named

plaintiff. Denying the right to appeal to the class because

the named plaintiff has been paid would generate precisely

* Petitioner’s seek relief from their obligation to make the in

jured members of the class whole on the ground that a great many

were injured in the context of a complex plant seniority structure

thereby creating difficulties of ascertainment of individual reme

dies. If allowed, this would lead to the anomaly that the only

safe discrimination to practice is mass discrimination. A’s Judge

Thornberry put it, “ . . . the fact that a defendant has man

aged to discriminate against many people instead of a few is no

ticket to freedom from liability to those who suffered less than

the most obvious victims.” (A.90)

the evil of the multiplicity of law suits that class actions

were designed to prevent.

3. Modification of the Class

Petitioner argues that since the class was modified

“after trial at judgment” (IJ.S. Steel Pet. at 2, 10) it was

in violation of Rule 23(c) (1) which permits alteration or

amendment of the class “before the decision on the

merits”.

a) Petitioner’s question is premature. The proper

class has yet to be defined. The Fifth Circuit va

cated the lower court’s definition of the class and

remanded for a hearing on this “comprehensive and

multifaceted” question to determine the “jiropri-

ety”, “size”, “scope” and “membership” of the

class. (A 83-84)

b) Petitioner is in error on the facts, in any case. The

decree modifying the class was entered on May 2,

1973. The Judgment of the court was rendered on

August 10, 1973. The class was therefore altered

“before the decision on the merits” in compliance

with Rule 23(c) (1).“ See supra at n. 2.

c) Finally petitioner’s reliance on Rule 23(c) (1) is

misplaced. In a (b) (2) class action, such as the

case at bar, the relevant rule on the timing of the

5 Even if the class had been amended at the time of judgment,

as petitioner incorrectly asserts, there would still have been com

pliance with Rule 23(c)(1) as Seventh Circuit explained in

Jimenez v. Weinberger, 523 P.2d 689 (1975): . the ex

plicit permission to alter or amend a certification order before

decision on the merits plainly implies disapproval of such alter

ation or amendment thereafter. On the other hand, that degree

of flexibility permitted before the merits are decided also indi

cate that in some cases the final certification need not be made

until the moment the merits are decided.” (at 697)

determination of the scope of the class is Rule

23(c)(3). That rule states; “the judgment in an

action maintained as a class action under subdivi

sion (b)(1) or (b)(2), whether or not favorable to

the class, shall include and describe those whom the

court finds to be members of the class.” (emphasis

added) When Judge Pointer in his Decree of May

2, 1973 described those whom he found to be mem

bers of the class, he was in strict compliance with

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.''

d) Petitioner’s additional complaint of lack of notice

and hearing as violative of its right to due process

is clearly frivolous. There was no element of sur

prise or prejudice to the petitioner when the class

represented by Ford, et al. was expanded to in

clude individuals who were represented by the

United States in a “pattern and practice” suit con

solidated for trial with Ford, and vdiose claims had

been thoroughly litigated at a lengthy trial at which

petitioner had full opxoortunity to present evidence.''

(A 42-43)

4. The Class Action Tolling Rule

Petitioner cites the rule in American Pipe and Construc

tion Co. V. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974) as authority that the

statute of limitations had run for the 2,700 individuals

thereby precluding their entry into the class.

® In Jimenez, ibid., the Seventh Circuit construed 23(c)(3) as

follows: “the language of subparagraph (c)(3) would seem to

permit the entry of a 'single order determining both the merits

and the identity of the class. Certainly there is nothing in the

rule expressly depriving the district court of power to enter such

an order.” (523 P.2d at 698)

The petitioner, United States Steel Corporation, put on evi

dence for approximately thirty-five days of trial.

In American Pipe, a class certification was denied and

tlie suit went forward as a private action. The issue before

this Court was whether the statute of limitations had run

for those individuals, who would have been members of

the class had it been certified, with respect to their right to

intervene in the private action. The cpiestion of the rights

of interveners to get into court where a class action has

been denied is irrelevant to the issue of the appropriate

inclusion in an aleady certified class of new members whose

claims had already been litigated at a consolidated trial.

Petitioner strives for relevance by quoting American

Pipe as follows; “We are convinced that the rule most

consistent with federal class action procedures must be

that commencement of a class action susjjends the statute

of limitation as to all asserted members of the class . . .”

(Pg. 11 of petition: emphasis by petitioner). Therefore

petitioner suggests that since the added members of the

new Ford class had not been the “asserted” members of

the old Ford class, then the statute of limitations had run

for them. But petitioner’s quotation omits the second part

of the sentence which reads, “who would have been parties

had the suit been permitted to continue as a class action.”

(414 U.S. 538, 554). Thus, even if the rule in American

Pipe is relevant, this omitted part of the sentence suggests

that the statute of limitations ivould have been tolled for

the 2,700 blacks who were not in the class originally be

cause they clearly “would have been members of the class

had the suit been permitted to continue as a class action.”

In the instant case a class action was permitted and the

new members were in fact included in the class prior to

the entry of judgment. As this Court stated in American

Pipe, “Thus, the commencement of the [class] action sat

isfied the purpose of the limitation provision as to all

those who might subsequently participate in the suit as

well as for the named plaintiffs.” (at 551). Not only were

the 2,700 blacks “those who might subsequently participate

in the suit”, they were in fact those who had already par

ticipated in the suit. A fortiori the statute of limitations

tolled for them. The court below properly, indeed neces

sarily, included them in the class to which the judgment

would apply to avoid the possibility of 2,700 private law

suits.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the petitions for certiorari should be denied.

J ack G-beenbeeg

J am es M. N a b eit , III

E bic S c h n a p p e e

B aeey L. G oldstein

S ta n ley E n g e l st e in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

OscAE A dams

J am es K. B a k ee

TJ. W . Clem o n

Suite 1600, The 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for John 8. Ford, et al.

la

APPENDIX

U n it e d S tates D istrict C ourt

N o r th er n D istr ic t of A labama

Southern Division

Civil Action No. 70-906

U n it e d S tates of A m erica ,

Civil Action No. 66-343

L u t h e r M cK in s t r y , et al.,

Civil Action 66-423

W illia m H ardy, et al.,

Civil Action No. 66-625

J o h n S . F ord, et al.,

Civil Action No. 67-121

E lder B r o w n , et al.,

Civil Action No. 68-204

E lbx P . L ove, et al.,

Civil Action No. 69-165

J am es D onald , et al.,

— v̂s.—

Plaintiff;

Plaintiffs;

Plaintiffs;

Plaintiffs;

Plaintiffs;

Plaintiffs;

Plaintiffs;

U n ited S tates S t e e l C orporation , et al..

Defendants.

2a

Appendix

m ent

It is Oedeked , A djudged and D ecreed as follows:

1. McKinstry v. TJ. 8. Steel Corp., CA 66-343.—

(a) Bach pay. The defendants United States Steel

Corporation and Local Union 1013, United Steel

workers of America, APL-CIO-CLC, shall each pay to

the eight class members named on the attachment

hereto one-half of the amount shown thereon opposite

such member’s name and badge number. Payments

shall be subject to reduction for employment taxes and

withholding as may be required by applicable law.

(b) Attorney’s fees. Said defendants shall each pay

to U. W. demon, as attorney’s fees for the plaintiffs

in such case, under 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-5(j), the sum

of $29,250 (of which $4,250 represents reimbursement

of expenses).

2. Hardy v. U. 8. Steel Corp., CA 66-423.—

(a) Bach pay. The defendants United States Steel

Corporation and Local Union 1489, United Steel

workers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC, shall each pay

to the twenty class members named on the attachment

hereto one-half of the amount shown thereon opposite

such member’s name and badge number. Payments

shall be subject to reduction for tax veithliolding and

employment taxes as may be required by aioplicable

laws.

(b) Attorney’s fees. Said defendants shall each pay

to Oscar W. Adams, Jr., as attorney’s fees for the

plaintiffs in such case, under 42 U.S.C.A. §2000e-5(j),

3a

Appendix

the sum of $26,500 (of whidi $4,000 represents reim

bursement of expenses).

3. Ford V. U. 8. Steel Corp., CA 66-625.—

(a) Back pay. The defendants United States Steel

Corporation and Local Union 1733, United Steel

workers of America, AFL-CIO-CLG, shall each pay to

the thirty-three class members named on the attach

ment hereto one-half of the amount shown thereon

opposite such member’s name and badge number. Pay

ments shall be subject to reduction for tax withholding

and employment taxes as may be required by ap

plicable laws.

(b) Attorney’s fees. Said defendants shall each pay

to James K. Baker, as attorney’s fees for the plaintiffs

in such case, under 42 U.S.C.A. 2000e-5(j), the sum of

$29,250 (of which $4,250 represents reimbursement of

expenses).

4. Brown v. U. 8. Steel Corp., CA 67-121.—The defen

dants United States Steel Corporation and Local Union

1733, United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC,

shall each pay to J. Kichmond Pearson, as Attorney’s fees

for the plaintiffs in such case, under 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

5(j), the sum of $4,500.00.

5. Love V . U. 8. Steel Corp., CA 68-204.—The defen

dants United States Steel Corporation and Local Union

1489, United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC,

shall each pay to J. Richmond Pearson, as attorney’s fees

for the plaintiffs in such case, under 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

5(j), the sum of $4,500.00.

6. Donald v. II. 8. Steel Corp., CA 69-165.—The defen

dants United States Steel Corporation and Local Union

4a

Appendix

1013, United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC,

shall each pay to Demetrius C. Newton, as attorney’s fees

for the plaintiffs in such case under 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

5(j), the sum of $8,500.00.

7. Denial of other claims.—All claims for hack pay and

attorney’s fees are, except as provided in paragraphs 1

through 6 hereof, denied.

8. Line of Progression Modification.—Attached hereto is

a Line of Progression for Unit 1201, No. 4 Galvanizing

Line, Fairfield Steel Plant, which is hereby substituted for

the line of progression chart for such unit as contained in

the decree dated May 2, 1973. Such change is effective as

of August 1, 1973, notwithstanding the 60-day notice provi

sion contained in paragraph 4 of the May 2, 1973, decree.

9. Order under Rule 54(h).—In paragraph 15 of the

May 2, 1973, order the court severed those claims in civil

action 70-906 relating to testing procedures, and such

claims have not been determined by this court but remain

for further consideration. As to all other claims in the

cases appearing th^ style of this judgment, the court now

under Eule 54(b) expressly determines that there is no

just reason for delay and expressly directs that judgment,

as contained in the decree of May 2, 1973 and this judg

ment, be entered as a final judgment as against all parties.

Final judgments have previously, on May 2, 1973, been

entered in CA 69-68 and CA 71-131, which had been con

solidated for trial with the cases appearing in the style

of this judgment.

Done this the 10th day of August, 1973.

/s / S am C. P o in t e r , J r .

United States District Judge

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219