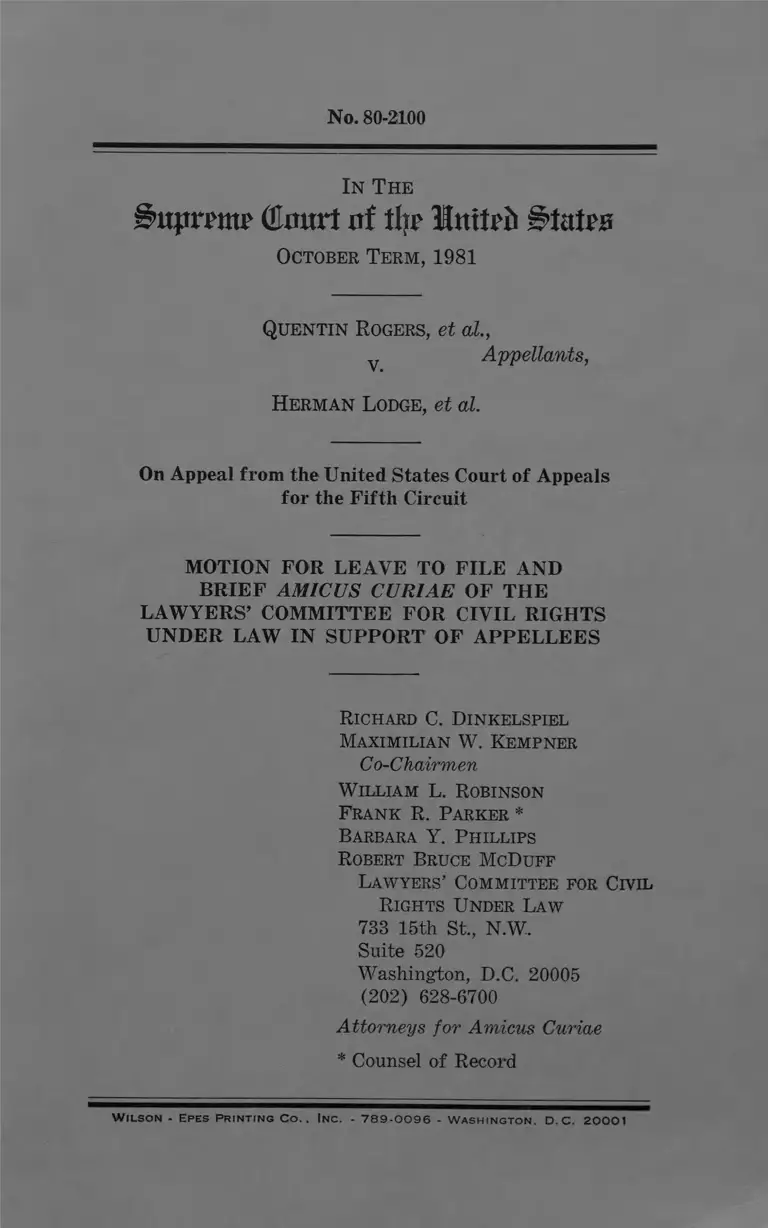

Rogers v Lodge Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1981

39 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v Lodge Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1981. 439bea30-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/675d2e3f-e935-4c27-87c2-492fba4f31fc/rogers-v-lodge-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed December 16, 2025.

Copied!

No. 80-2100

In T he

§>u$rmt (IJmtrt of tfrr lUnlM BttxtiB

October T er m , 1981

Qu e n tin Rogers, et al.,

v Appellants,

H e r m a n L odge, et al.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Maximilian W . Kempner

Co-Chairmen

W illiam L. Robinson

Frank R. Parker *

Barbara Y. Phillips

Robert Bruce McDuff

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 15th St, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W il s o n - Ep e s Pr in t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n . D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

In T he

i>upratt£ (Emtrt vt % Unttpfo i ’tatris

October T er m , 1981

No. 80-2100

Qu e n tin Rogers, et al.,

Appellants,

H er m a n Lodge, et al.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

seeks leave to file the annexed brief as amicus curiae.

The appellees have consented to the filing of this brief,

but appellants have not.

The Lawyers’ Committee was organized in 1963 at the

request of the President of the United States to involve

private attorneys throughout the country in the national

effort to assure civil rights to all Americans. Protec

tion of the voting rights of citizens has been an impor

tant aspect of the work of the Committee; it has pro

vided legal representation to litigants in numerous vot

ing rights cases for the past fifteen years.*

This case presents important issues of proof and legal

standards applicable to challenges to at-large elections

for dilution of black voting strength. The case has im

portance beyond its immediate facts because the ruling

of the Court will affect pending and future litigation

in this area. The Lawyers’ Committee represents black

voter plaintiffs and is otherwise involved in four pending

cases challenging at-large election schemes,** and the

Court’s ruling in this case is likely to have a direct

impact on the outcome of those pending cases.

In our view, the judgment of the Court of Appeals

should be affirmed, but we wish to present arguments

different from those expressed by the Court of Appeals

or likely to be forwarded by the parties. We take the

position that the District Court’s conclusion that at-large

county commission elections are being maintained for an

invidious purpose is amply supported by subsidiary find-

* For example, the Lawyers’ Committee represented a class of

black citizens of Mississippi in reapportionment litigation which

was before this Court on several occasions: Connor v. Johnson,

402 U.S. 690 (1971); Connor v. Williams, 404 U.S. 549 (1972);

Connor v. Waller, 421 U.S. 656 (1975); Connor v. Coleman, 425

U. S. 675 (1976) ; Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977); Connor

V. Coleman, 440 U.S. 612 (1979) ; id., 441 U.S. 792 (1979) ; United

States v. Mississippi, 444 U.S. 1050 (1980). The Lawyers’ Com

mittee also has been granted leave of this Court to file briefs

amicus curiae in a number of important voting rights cases decided

by this Court, including McDaniel V. Sanchez, 68 L. Ed.2d 724

(1981); City of Mobile V. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980); Wise V.

Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978); and East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976).

** Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 506 F. Supp. 491 (S.D. Miss.

1981), aff’d, ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir., December 11, 1981);

Boykins v. City of Hattiesburg, Civil No. H77-0065(C) (S.D.

Miss., filed May 27, 1977) ; Greenville Citizens for More Representa

tive Government v. City of Greenville, Civil No. GC-77-99-S (N.D.

Miss., filed August 30, 1977) ; and Jordan V. City of Greenwood,

Civil No. GC-77-52-K (N.D. Miss., filed May 6, 1977).

mgs of fact and evidence which prior decisions of this

Court have held are sufficient to support a conclusion of

discriminatory purpose. We also argue that at-large

elections in Burke County are unconstitutional because

they perpetuate the present effect of a past purposeful

and intentional denial to blacks of equal access to the

political process, and that proof of the unresponsiveness

of the white elected officials to black interests should not

be a controlling element of proof of the unconstitutional

ity of the at-large election system under which the of

ficials were elected.

Accordingly, the Lawyers’ Committee seeks leave to

file this brief to present questions of law and legal argu

ment that are not likely to be presented by the parties

and which, if accepted, would directly control this Court’s

disposition of this case.

WHEREFORE, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law respectfully moves the Court for

leave to file the attached brief amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Maximilian W . Kempner

Co-Chairmen

W illiam L. Robinson

Frank R. Parker *

Barbara Y. Phillips

Robert Bruce McDuff

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 15th St., N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT_____ _____

ARGUMENT ................

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S CONCLUSION

THAT AT-LARGE ELECTIONS HAVE BEEN

MAINTAINED IN BURKE COUNTY FOR

THE DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE OF

DENYING BLACKS EQUAL ACCESS TO

THE POLITICAL PROCESS IS CORRECT

AND SHOULD BE SUSTAINED ....................

II. t h e c o n s t it u t io n p r o h ib it s a t -

l a r g e ELECTIONS WHICH HAVE THE

EFFECT OF PERPETUATING OFFICIAL

AND INTENTIONAL DENIAL TO BLACKS

OF EQUAL ACCESS TO THE POLITICAL

PROCESS ................ ................................... ........

III. THE OPINION OF THE COURT OF AP

PEALS IS INCORRECT INSOFAR AS IT

REQUIRES A SHOWING OF UNRESPON

SIVENESS TO SUSTAIN A CHALLENGE TO

AT-LARGE ELECTIONS ............

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .....................................

CONCLUSION

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969) ..................................... .............. ..................... 4, 5, 10

Avery V. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) .... 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ............................. 29

Chapman v. King, 154 F.2d 460 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 327 U.S. 800 (1946) ........................ ......... 21

City of Mobile v. Bolden 446 U.S. 55 (1980) ....1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

6, 8, 9, 10,11,12, 14,15, 16, 26, 28, 29

City of Rome, Georgia V. United States, 446 U.S.

156 (1980) .................... is

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449 (1979) .......... 7 ,8 ,19

Connor V. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977) ..................... 4,10

Connor V. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971) _________ 4

Dayton Board of Education V. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) ................................................. .............. 7, 18, 19

East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976) ................... .......... ................. . 4

Flax v. Potts, 404 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 409 U.S. 1002 (1972) .............................. 19

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969) ................ 23

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)................. .............. ................. 17

Keyes V. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ............ ............... ................. ........ ............ . is

Kirksey V. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

Mississippi, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.) (en banc),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977) ...............15, 16, 23, 24

Lodge V. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981) ... 3,19,

24, 28

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).... 16, 17

McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d

277 (5th Cir. 1976) ................................................ 21

McMillan v. Escambia County, Florida, 639 F.2d

1239 (5th Cir. 1981) 21, 29

1U

Page

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts V.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 265 (1979) ....... ............ -......... 4,20

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967)........ — 15

Smith V. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) .......... . 25

Stewart v. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206 (N.D. Miss.

1975) (three-judge court) — ....................... - 14

Swann V. Charlotte-MecJclenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ...... ................................... 18,19

Village of Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan De

velopment Corporation, 429 U.S. 252 (1977)...5 ,7 ,9 ,

14, 15, 20, 29

Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....... 1, 3, 5, 6,

15,16, 20

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) ............ 2

White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ....... 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

15,16, 17,19, 25

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) ..... ................ ........... -.............................. .....15,16, 28

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ....

Ga. Code § 2-403 ...

Ga. Code § 34-1015

Ga. Code §34-1513

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Other

Campbell, A., et. al., The A merican V oter

(1960) ...... ......... ............... -.......- ...................-----...... 24

Campbell, A., et. ah, The V oter Decides (1954).. 24

Davidson, C. and Korbel, G., At-Large Elections

and Minority Group Representation: A Re-

Examination of Historical and Contemporary

Evidence, 43 J. OF POL. 982 (Nov. 1981) ............ 6

Engstrom, R. and McDonald, M., The Election of

Blacks to City Councils: Clarifying the Impact

of Electoral Arrangements on the Seats/Popu

lation Relationship, 75 A m . Political Sci. Rev.

344 (June 1981) .... — ..............................-.............

8, 9, 22, 23

23

....7, 14, 27

....7, 14, 27

6

IV

Page

Erbe, W ., Social Involvement and Political Ac

tivity: A Replication and Elaboration, 29 A m .

Soc. Rev. 198 (1964) ............................................. . 24

Hays, S., The Politics of Reform in Municipal

Government in the Progressive Era, 55 Pac.

N orthwest Q. 157 (1964) ..................... .............. . 12

Jones, C., The Impact of Local Election Systems

on Black Political Representation, 11 Urb. A ff.

Q. 345 (March 1976) ..................... ............... ........... 6

Kousser, J., The Shaping of Southern Politics

(1 9 7 4 )_______________ __________ ____ __________ _ 21

Kamig, A., Black Representation on City Councils,

12 Urb. A ff. Q. 223 (Dec. 1976) ......................... 6

Milbraight, L., Political Participation (1965).. 24

Note, The Supreme Court, 1979 Term, 94 Harv.

L. Rev. 75 (1980) ...... ............ .................................. 3

Rice, B., Progressive Cities: The Commission

Government Movement in A merica, 1901-

1920 (1977) .......... ....... ............ ..................................... 12, 13

Robinson, T. and Dye, T., Reformism and Black

Representation on City Councils, 59 Soc. SCI. Q.

133 (June 1978) ......................................................... 6

Silver, J., M ississippi: The Closed Society

(1964) ...................... ...................... ...... ........................ . 21

Taebel, D., Minority Representation on City Coun

cils, 59 SOC. Sci. Q. 143 (June 1978) ........ ........... 6

United States Bureau of the Census, Governing

Boards of County Government: 1973 (1974).... 12

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The

V oting Rights A c t : Ten Y ears A fter (1975).. 10

Weinstein, J., The Corporate Ideal in the Lib

eral State, 1900-1918 (1968) ............................... 12

Weinstein, J., Organized Business and the City

Commissioner and Management Movements, 28

J.S. H ist. 166 (1962) ............................ ................. . 12

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

In T h e

ilitjtmttp (SJrnul nf % llmtTi* States

October Term , 1981

80-2100

Qu e n tin Rogers, et al,

v Appellants,

H e r m a n L odge, et al.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law in this matter is set out in the Motion

for Leave to File this brief which is appended hereto.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The evidence in the record amply supports the find

ing of the District Court that at-large elections for the

County Commission of Burke County, Georgia have been

maintained with the intent of continuing the historical

exclusion of black citizens in Burke County from the

political processes. This is clear because the evidence

and findings are comparable to the indications of dis

criminatory intent found in White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973), which was reaffirmed by City of Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). Moreover, the evidence and

findings conform to a number of factors which this

Court, in a line of cases since Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229 (1976), has said provide strong indicia of dis

criminatory intent.

2

2. Even if the evidence does not show discriminatory

intent in the direct adoption or maintenance of this at-

large election plan, the plan is nevertheless unconstitu

tional because it perpetuates the present effect of a prior

intentional and unconstitutional exclusion of black citi

zens from the political process. This standard comports

with the Court’s previous decisions in vote dilution and

school desegregation cases, and also focuses on the issue

of discriminatory intent as required by the Court’s hold

ings in equal protection cases. As found by the District

Court, prior intentional and unconstitutional discrimina

tion has excluded the black citizens of Burke County,

Georgia from the political process, and the at-large plan

for electing county commissioners in Burke County per

petuates that exclusion.

3. The Court of Appeals incorrectly held that proof

of unresponsiveness is necessary to the successful main

tenance of a constitutional challenge based on grounds of

racial vote dilution. This conclusion, unnecessary to the

resolution of the instant case, is based on a misreading

of the plurality opinion in Mobile, and is inconsistent

with previous holdings of this Court.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S CONCLUSION THAT

AT-LARGE ELECTIONS HAVE BEEN MAIN

TAINED IN BURKE COUNTY FOR THE DIS

CRIMINATORY PURPOSE OF DENYING BLACKS

EQUAL ACCESS TO THE POLITICAL PROCESS IS

CORRECT AND SHOULD BE SUSTAINED.

At-large voting is not unconstitutional per se, but is

unconstitutional if it has been conceived, operated, or

retained “ invidiously to minimize or cancel out the vot

ing potential of racial or ethnic minorities.” City of

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 66 (1980) (plurality

opinion) ; see also, White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 765

(1973) ; Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 149 (1971).

The Mobile plurality concluded that plaintiffs’ burden is

to prove “ that the disputed plan was ‘conceived or oper

3

ated as tail purposeful devic[e] to further racial . . .

discrimination.’ ” 446 U.S. at 66. However, the opinion

of the plurality has been criticized as failing to provide

adequate guidance to the lower courts in determining

discriminatory purpose in vote dilution cases, and in

particular “because it refused to draw inferences that

are reasonable in light of the Court’s intent decisions

since Washington v. Davis, [426 U.S. 229 (1976)].”

Note, The Supreme Court, 1979 Term, 94 Harv. L. Rev.

75, 147 (1980). This case gives this Court an oppor

tunity to clarify Mobile and provide additional guidance.

We respectfully submit that the trial court’s finding

of intentional discrimination in the maintenance of

Burke County’s at-large election scheme was properly

affirmed below on two separate grounds: first, because

the proof that blacks were excluded from the political

process in Burke County met the requirements of White

v. Regester; and second, because the evidence more than

amply established intent under more recent decisions of

this Court. Our discussion of the evidence in the in

stant case will focus on the indicia of intent identified in

those more recent decisions.

As the Court of Appeals in this case1 correctly points

out,

In a voting dilution case in which the challenged

system was created at a time when discrimination

may or may not have been its purpose, it is unlikely

that plaintiffs could ever uncover direct proof that

such system was being maintained for the purpose of

discrimination.

Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358, 1363 (5th Cir. 1981)

(footnotes omitted). “ Quite simply, there will be no

‘smoking gun.’ ” Id. at 1363 n. 8. This Court has made

it clear from Washington v. Davis that: “ Necessarily,

an invidious discriminatory purpose may often be in

ferred from the totality of the relevant facts . ” 426

U.S. at 242.

4

Indeed, this Court has never required proof of overt

racial statements or a subjective state of mind of racial

intent. “ Proof of discriminatory intent must necessarily

rely on objective factors,” Personnel Adm’r of Mass. v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 265, 279 n. 24 (1979), and requires

“ a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available.” Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Homing Dev. Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977). Furthermore, to prevail,

plaintiffs need not prove that a racial purpose was the

sole, dominant, or even the primary purpose for a chal

lenged action, but only that it “has been a motivating

factor in the decision.” Arlington Heights, supra, 429

U.S. at 265-266. “ Discriminatory intent is simply not

amenable to calibration. It either is a factor that has

influenced the legislative choice or it is not.” Personnel

Adm’r of Massachmetts V. Feeney, supra, 442 U.S. at

277 (1979).

While the evidence in the instant case certainly proves

a constitutional violation in light of a White v. Regester

analysis,1 which was reaffirmed by the Mobile plurality

1 The Mobile plurality’s suggestion that a constitutional distinc

tion may exist between multi-member legislative districts and local

at-large governments, 446 U.S. at 70, is untenable and, at the: very

least, inapplicable to this case. There is nothing in White V.

Regester or this Court’s other cases to indicate that the White V.

Regester analysis hinged on the presence of legislative districts as

opposed to other units of government. The potential harm in

volved— the submersion of electoral minorities^—is present both in

multi-member legislative districts and local at-large election plans,

see Connor V. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 415 (1977), and Allen V. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 569 (1969), and this Court has

therefore expressed its strong preference for single-member dis

tricts in court-ordered reapportionment plans in both the legislative

and local government contexts. See Connor V. Johnson, 402 U.S.

690 (1971), and East Carroll Parish School Bd. V. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976). Furthermore, there is no distinction expressed

in this Court’s malapportionment cases, which, like racial dilution

cases, involve claims of diminished voting power. Allen, supra,

393 U.S. at 569. The malapportionment doctrine applies in like

5

(446 U.S. at 69-70),2 it also supports a finding of dis

criminatory intent reached by considering factors identi

fied in decisions of this Court since Washington v. Davis.

It is those factors upon which this discussion will focus,

rather than a White v. Regester factual analysis. As de

tailed below, the District Court’s conclusion, affirmed by the

Fifth Circuit, that “ the present scheme of electing county

commissioners . . . is being maintained for invidious

purposes” (J.S., App. 71a) is amply supported by sub

sidiary findings of fact and evidence giving rise to infer

ences which this Court has held in prior cases are suffi

cient to support a conclusion of discriminatory purpose.

1. Discriminatory impact. In determining whether or

not at-large voting is being retained for a discriminatory

purpose, “ [t]he impact of the official action— whether it

fashion to local governments and state legislatures. Avery v.

Midland County, 390 U.S. 474, 485 (1968).

The Mobile plurality’s intimation of a constitutional distinction

was accompanied by two observations apparently thought to give

support to that distinction: (1) that the Mobile City Commission

exercised not only legislative policymaking power, but also executive

and administrative power, therefore requiring that each city voter

cast an at-large ballot for each of the city commissioners, all of

whom would exercise citywide administrative and executive func

tions; and (2) that at-large municipal elections were once “ uni

versally” heralded as good-government reforms. 446 U.S. at 70 and

n. 15. The two observations are irrelevant to the present case—

the first because the Eurke County Commission exercises only

legislative policymaking power, and not executive or administrative

functions, and the second because it pertains to the history of

municipal governments and not county governments. Additionally,

as demonstrated later in this brief, the accuracy of the plurality’s

historical conclusion is highly questionable in light of recent his

torical research. And even if good-government reform played some

part in the institution of the commission form of government in

some American cities, that is no basis for making constitutional

distinctions which affect the standards governing voting rights

cases in all local governments, city and county.

2 Justice Stevens appears also to have reaffirmed White v.

Regester. 446 U.S. at 84, n. 2, as did Justice Blackmun and the

Mobile dissenters.

6

‘bears more heavily on one race than another/ Washing

ton v. Davis [426 U.S.] at 242— may provide an impor

tant starting point.” Mobile, supra, 446 U.S. at 70. As

Justice Stevens aptly noted in Washington v. Davis,

Frequently the most probative evidence of intent will

be objective evidence of what actually happened

rather than evidence describing the subjective state

of mind of the actor. For normally the actor is pre

sumed to have intended the natural consequences of

his deeds.

426 U.S. at 253 (concurring opinion).

Here the District Court found that no black candidate

has ever been elected to the County Commission, despite

the fact that Burke County has historically been major

ity black in population (J.S., App. 66a). The District

Court also found that when blacks ran for the County

Commission, they carried majority black districts, but

lost in countywide voting [id,, App. 72a-73a), and that

when at-large elections were abolished in Waynesboro,

the county seat, and single-member districts were im

plemented, there was an increase in black representation

on the city council (id., App. 73a) .3

The District Court also found that the discriminatory

impact of countrywide voting was enhanced by the large

3 Among social scientists, there is little question that at-large

voting is racially discriminatory. Numerous empirical studies

based on data collected from throughout the nation have found a

direct causal relationship between at-large elections and exclusion

of minority representation. See, e.g., C. Davidson and G. Korbel,

At-Large Elections and Minority-Group Representation: A Re-

Examination of Historical and Contemporary Evidence, 43 J. of

Pol. 982-1005 (Nov. 1981); R. Engstrom and M. McDonald, The

Election of Blacks to City Councils: Clarifying the Impact of Elec

toral Arrangements on the Seats /Population Relationship, 75 A m .

Pol. Sci. Rev. 344-354 (June 1981) ; D. Taebel, Minority Repre

sentation on City Councils, 59 Soc. SCI. Q. 143-52 (June 1978) ;

T. Robinson and T. Dye, Reformism and Black Representation on

City Councils, 59 Soc. Sci. Q. 133-41 (June 1978); A. Karnig, Black

Representation on City Councils, 12 Urb. Aff. Q. 233-43 (Dec.

1976); C. Jones, The Impact of Local Election Systems on Black

Political Representation, 11 Urb. Aff. Q. 345-56 (March 1976).

7

geographic size of the county which “has made it more

difficult for blacks to get to polling places or to cam

paign for office” {id,., App. 91a), by the Georgia statu

tory majority vote requirement (Ga. Code Ann. § 34-

1513) which “ tends to submerge the will of the minority

and to deny the minority’s access to the system” {id.,

App. 92a), by the numbered post requirement (Ga. Code

Ann. § 34-1015) which “ enhance[s] plaintiffs’ lack of

access to the system” {id.), and by the lack of any dis

trict residency requirement, so that “ [a] 11 candidates

could reside in Waynesboro, or in ‘lilly-white’ neighbor

hoods” {id., App. 93a).

The record in this case shows not only that the county

wide voting scheme has a racially disproportionate im

pact, but also that local white officials responsible for

maintaining at-large voting concede and are fully aware

that no black can get elected to the County Commission

under this at-large system. (Tr., p. 168). This Court

has recognized that “ actions having foreseeable and anti

cipated disparate impact are relevant evidence to prove

the ultimate fact, forbidden purpose.” Columbus Bd. of

Educ. v. Penick, 433 U.S. 449, 464 (1979) ; see also,

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman {Dayton II), 443 U.S.

526, 536 n. 9 (1979) (“proof of foreseeable consequences

is one type of quite relevant evidence of racially dis

criminatory purpose” ). Since the responsible officials

were aware and could reasonably foresee that the main

tenance of this at-large election system would continue

the historic exclusion of black representation from

county government, it was appropriate for the District

Court to infer that this discriminatory impact was

intended.

2. Pattern and practice of racial discrimination. In

proving discriminatory purpose, this Court has held:

“ The historical background of the decision is one evi

dentiary source, particulary if it reveals a series of

official actions taken for invidious purposes.” Arlington

Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 267. The findings of the Dis

trict Court indicate that black citizens in Burke County

8

have been discriminated against and segregated in every

aspect of public life, including political and electoral af

fairs, and that this racial discrimination and segrega

tion is continuing down to the present time. Prior to

the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, blacks in

Burke County were denied the right to register and vote

by literacy tests, poll taxes, and white primaries, all

maintained by county officials under color of state law

(J.S., App. 71a-72a, 86a). Since the enactment of the

Voting Rights Act, the County Commission has con

tinued to deny the county’s black citizens polling places

and the opportunity to register and vote (J.S., App. 81a).

In addition, the District Court found that the County

Commission continues to discriminate against black citi

zens in appointments to boards and commissions which

oversee the execution of county government (J.S. App. 76a,

78a), in judicial appointments {id., App. 78a-79a), by

maintaining a discriminatory hiring policy for county

employment {id., App. 75a,-76a, 79a), in paving of

county roads {id., App. 79a-80a), and by participating in

the establishment of the Edmund Burke Academy, a

segregated, all-white private school established to cir

cumvent public school desegregation {id., App. 81a-82a).

The county’s practice of racial discrimination in grand

jury selection continued until 1977, when it was termi

nated under compulsion of court order {id., App. 75a).

In short, whenever officials in Burke County came to

a “ crossroads where [they] could either turn toward

[burdening minorities] or away from it,” Columbus Bd.

of Educ. V. Penick, supra, 443 U.S. at 463, n. 12, they

consistently chose the alternative with the greatest dis

criminatory impact. Such evidence is highly probative

of discriminatory intent. Id.

Indeed, this proof goes beyond the mere fact of unre

sponsiveness of the elected county officials to black needs

and interests, which the Mobile plurality said “ is rele

vant only as the most tenuous and circumstantial evi

dence of the constitutional invalidity of the electoral sys-

tern under which they attained their offices” (446 U.S. at

74), and the “ original sin” (id.) of past discrimina

tion. The findings of the District Court clearly demon

strate an official county policy of excluding black citi

zens from full participation in county government, a

policy which is furthered and enhanced by the county’s

discriminatory at-large voting system, and of which at-

large voting is an integral part. Moreover, in contrast

to Mobile, the record here shows that blacks in Burke

County do not always register and vote “ without hind

rance.” See Mobile, supra, 446 U.S. at 73. Thus, this

evidence of historic and present invidious discrimination

against the black community gives rise to an inference,

which was drawn by the District Court and affirmed by

the Court of Appeals, that the county’s at-large election

scheme which excludes any opportunity for black repre

sentation is being maintained specifically for an invidious

racial purpose.

3. Lack of an adequate, nonracial reason. The absence

of a legitimate nonracial reason for a challenged action

is probative of discriminatory intent, “particularly if

the factors usually considered important by the decision-

makers strongly favor a decision contrary to the one

reached.” Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 267

(footnote omitted). In at-large election challenges, this

inquiry involves an analysis of the context in which at-

large voting is maintained. See, e.g., Mobile, supra, 446

U.S. at 60-61 (plurality opinion).

Following the passage of the Voting Rights Act, giv

ing blacks in Georgia the right to vote for the first time

since Reconstruction, 18 Georgia counties switched from

district elections to at-large elections. (T. 398-99). This

pattern also was evident in other states covered by the

Voting Rights Act,4 providing evidence of discrimina

tory motivation behind at-large countywide voting.

4 For example, in Mississippi, 13 counties attempted to switch to

at-large voting for members of boards of supervisors, the county

governing board, and 22 counties attempted to switch to at-large

9

10

The District Court did not find any countervailing

legitimate, nonraeial reason for maintaining at-large

countywide county commission elections in Burke County.

It further found that the adoption of single-member dis

tricts would not impair the county’s ability to function

and could be reasonably accomplished (J.S., App. 91a,

96a). The system of government involved in this case,

then, contrasts sharply with the system challenged in

Mobile, in which “ an entire system of local governance

[was] brought into question” (446 U.S. at 70).

In Mobile, the fact that each of the Mobile, Alabama

city commissioners was vested with both executive and

administrative powers was alluded to by this Court as a

potential non-racial justification for a system under which

all voters cast ballots for all members of the city commis

sion, inasmuch as it would be anomalous to elect a pub

lic official with a particular executive and administra

tive responsibility for the entire city (such as the com

missioner in charge of public safety) from a limited

geographic portion of the city. See Mobile, supra, 446

U.S. at 70. This is in contrast to a purely legislative

policy-making body in which the responsibilities of each

member are the same, and where each citizen is con

sidered to have an adequate voice by voting for a single

legislator who represents a specific geographic area. See

Connor v. Finch, supra, 431 U.S. at 415. Unlike the

Mobile City Commission, the Burke County, Georgia

Board of Commissioners is purely a policymaking body,

where each member’s responsibilities are alike, and none

possess executive or administrative functions.® Thus,

there is no non-racial justification based on executive 5

elections for county school board elections. See Fairley v. Patter

son, decided sub. nom. Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S.

544, 550, 569, 574-576 (1969); U.S. Commission on Civil R ights,

T he Voting R ights A c t : Ten Y ears A fter 271 (1975).

5 Executive duties are vested in the County Administrator, who is

appointed.

11

and administrative responsibilities wmch underlies at-

large elections in Burke County.’6

Because of this distinction, “ purpose” and “ effect” are

much more closely related in the instant case than in

Mobile. There, the plurality said:

The impact of the official action— whether it bears

more heavily on one race than another—may provide

an important starting point . . . But where the char

acter of a law is readily explainable on grounds

apart from race, as would nearly always be true

where, as here, an entire system of local governance

is brought into question, disproportionate impact

alone cannot be decisive, and courts must look to

other evidence to support a finding of discriminatory

purpose.

446 U.S. at 70 (emphasis added). Since, in this case, “an

entire system of local governance” is not at issue, dispro

portionate impact will be more probative of discriminatory

intent, for a non-racial justification is not apparent. In

deed, the showing of racial impact is extremely relevant to

a finding of purpose in the present lawsuit because the gov

ernmental decision at issue involves not a choice of an en

tire local governance system, but only a choice regarding

electoral districting. Any such districting decision is

merely a determination of which groups of voters will have

the deciding votes in electing particular public officials. In

essence, the goal of an apportionment scheme is the allo

cation of political power. Apportionment decisions are

directly reflected in the resulting distribution of electoral

power: which groups of voters possess power and which

ones do not. The purpose, therefore, is commensurate

6 Justice Stevens expressed the view in Mobile that there can

always be “ a substantial neutral justification for a municipality’s

choice of a commission form of government . . . .” 446 U.S. at 92,

n. 14 (concurring opinion). Insofar as that justification consists of

the desire to have all city voters participate in the choice of offiicals

who will exercise citywide executive and administrative power,

it is unavailing to the defendants in this case.

with the result, and the result is a strong indication of

the purpose.

Finally, and contrary to appellants’ submission, (Br.

32, 41), the Mobile plurality’s observations concerning

the popularity and historical development of at-large

municipal elections are irrelevant here, since they relate

only to the development of municipal governments in

America and not to at-large elections for county gov

ernment.7 Moreover, the thesis that at-large municipal

elections were “ universally heralded not many years ago

as a praiseworthy and progressive reform of corrupt

municipal government” (Mobile, supra, 446 U.S. at 70

n. 15) is flatly contradicted by the most recent and ex

haustive research on the subject, contained in Rice,

P rogressive C it ie s : T h e Co m m is sio n Go v e r n m e n t

M o v e m e n t in A m e r ic a , 1901-1920 (University of Texas

Press, 1977).

Dr. Rice’s detailed historical analysis shows that the

adoption of at-large voting under commission forms of

municipal government in the early 1900s was generally

the result of power struggles for the control of municipal

government in which the white “ business elites” (his

term) used at-large elections to wrest political control

from working class, ethnic, and minority citizens. Id. at

xvi, 4-18, 26-29, 34-51, 60-61, and passim,8 Far from

7 Unlike municipalities, a majority of which maintain at-large,

citywide election systems (Mobile, supra, 446 U.S. at 61),

[A ] majority of all counties in the Nation are governed by

popularly elected officials who represent districts or areas

within their respective counties.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Governing Boards of County Govern

ment: 1973 (Series SS No. 68) 4 (1974).

8 Dr. Rice’s research and conclusions are amply supported by

prior research in the field. See, e.g., J. Weinstein, T he Corporate

Ideal in the L iberal State, 1900-1918, ch. 4 (1968); S. Hays, The

Politics of Reform in Municipal Government in the Progressive

Era, 55 PAC. N.W. Q. 157-69 (1964) ; J. Weinstein, Organized Busi

ness and the City Commissioner and Management Movements, 28

J. S. H ist. 166-82 (1962).

12

being “universally heralded” as a progressive reform

measure, the spread of at-large municipal elections was

bitterly opposed by organized labor (with some excep

tions), working class elements, and ethnic and racial

minorities who feared, quite correctly, that at-large vot

ing would exclude them from participation in municipal

government. Id. at 27-29, 47, 78, 84-89. Indeed, Rice

concludes that a causal relationship can be inferred be

tween black population in cities and the adoption of the

commission form of municipal government {id. at 89),

and notes: “ Ethnic minorities were rightly suspicious of

at-large elections that ended their close association with

ward politics” {id. at 88).

A number of social reformers of the day fought the

move to at-large voting for the reason that it diminished

the impact of ethnic and minority votes {id. at 85), and

Charles Beard, the noted contemporary political scien

tist, cautioned against at-large voting in his 1912 text

book on municipal government, stating that it “ substan

tially excludes minority representation” {id. at 78).

Dr. Rice’s research also cautions against any assump

tion that the initiation or continuation of at-large gov

ernmental schemes in municipal America was motivated

only by good-government considerations. In many cities,

at-large governments failed to increase efficiency or to

eliminate factional bickering and boss politics. Id. at

88-99, 111. Although there was evidence of improvement

in some municipalities, contemporary writers also criti

cized commission government municipalities for poor debt

management, internal strife, extravagance, and lack of

expert management. Id. at 96-97.

In some cities the populace had simply traded the

logrolling and political tradeoffs of ward politics for

similar tactics among semi-autonomous departments.

Id. at 91.

Thus, even if this case involved a city rather than

a county government, we would urge the Court to reject

13

the notion that the Mobile panel’s generalized observa

tion— which should in any event be reevaluated in light

of relevant historical scholarship— can furnish a legiti

mate, non-raeial reason for the perpetuation of at-large

voting for Burke County Commissioners. Even less sup

portable is the suggestion that the plurality’s generaliza

tion outweighs or rebuts the other substantial evidence

of discriminatory intent in the record, or that it can

substitute for a particularized inquiry— as was per

formed by the District Court here— into the motivation

for retaining an at-large election scheme in a specific

locality. Cf. Stewart v. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206 (N.D.

Miss. 1975) (three-judge court).

4. Sequence of Events. According to the court’s deci

sion in Arlington Heights: “ The specific sequence of

events leading up to the challenged decision also may

shed some light on the decisionmaker’s purposes.” 429

U.S. at 267.

In 1964, as the Civil Rights Movement reached its

zenith and voter registration drives were underway in

Georgia, the state legislature instituted majority vote

and numbered post requirements—both of which disad

vantage black voters—for all at-large county commis

sion elections in Georgia, including those in Burke

County. (J.S. App., 65a, n. 2 ). This matter of tim ing9

is one of the pieces of evidence which shows that at-large

elections were maintained for racially discriminatory

reasons, for both measures have a discriminatory effect

on black political participation.10

14

9 See Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 267, n. 16 and accom

panying text.

10 Of course, plaintiffs here challenge the entire at-large scheme

in Burke County, not just these particular characteristics. But

evidence about the characteristics is highly relevant to the ultimate

issue, for if they were adopted for a racially discriminatory reason,

then the electoral system of which they are a part was obviously

maintained for purposes of racial discrimination.

Moreover, the addition of these provisions indicates a

substantive departure from normal state policy, in the Ar

lington Heights sense, since they were obviously considered

unnecessary to the functioning of at-large elections prior to

1964. Indeed, there is no adequate non-racial explanation

for the majority vote and numbered post requirements

and the absence of a residency requirement— all of which

disadvantage black voters—for there is nothing in the

nature of at-large election schemes which requires these

characteristics. See generally, City of Rome, Georgia

V. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 183-185 and nn. 19-21

(1980) ; White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S. at 766.

Because the District Court’s conclusion of discriminatory

purpose— affirmed by the Court of Appeals— relies on

findings and evidence which sufficiently portray uncon

stitutional intent as defined by previous decisions of this

Court, the judgment below should be affirmed.

II. THE CONSTITUTION PROHIBITS AT-LARGE

ELECTIONS WHICH HAVE THE EFFECT OF

PERPETUATING OFFICIAL AND INTENTIONAL

DENIAL TO BLACKS OF EQUAL ACCESS TO THE

POLITICAL PROCESS.

An at-large voting system, though itself racially neu

tral, violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

if it perpetuates an intentional and purposeful racially

discriminatory denial of access to the political process.

This perpetuation standard, which was approved in

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, Mis

sissippi, 554 F.2d 139, 143-144, 146 (5th Cir. 1977)

(en banc), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977), properly

examines the “ historical context and conditions” of a

challenged governmental action. Reitman v. Mulkey, 387

U.S. 369, 373 (1967). Additionally, it focuses on the

issue of discriminatory intent, and thereby meets the

Fourteenth Amendment requisites of Washington v.

Davis, and the plurality opinion in Mobile.“ The Kirksey

Court explained: 11

15

11 Kirksey is consistent with the opinions and the decision in

Mobile. Rather than relying on the type of Zimmer v. McKeithen

16

If a neutral plan were permitted to have this dis

criminatory effect, minorities presently denied access

to political life for unconstitutional reasons could be

walled off from relief against continuation of that

denial. The redistricting body would only need to

adopt a racially benign plan that permitted the rec

ord of the past to continue unabated. Such a rule

would sub silentio overrule White v. Regester. It

would emasculate the efforts of racial minorities to

break out of patterns of political discrimination.

554 F.2d at 147. This Court itself has acknowledged

that, in the area of voting rights, the proper response to

prior unconstitutional acts includes eliminating “ the dis

criminatory effects of the past.” Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965).

This constitutional analysis comports with the Court’s

unanimous decision in White v. Regester, which was re

affirmed in Mobile.12 The ultimate proof required by

White v. Regester was exclusion from the political sys

tem— a showing that “ the political processes leading to

nomination and election were not equally open to par

ticipation by the group in question.” 412 U.S. at 766.

This could be done, according to the Court, by proof of

current exclusionary effect along with a demonstration

of prior official discrimination— political and otherwise.

Thus, of evidentiary importance were such things as a 12

(485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)) laundry-list presumption disap

proved by the Mobile plurality, the Kirksey Court focused on intent

and found prior intentional discrimination, the exclusionary effects

of which were perpetuated by the electoral scheme at issue.

To the extent that Kirksey relied upon or reflected the Zimmer

analysis, it can be disregarded, allowing the perpetuation standard

forwarded here to be viewed independently of Zimmer.

12 It is clear that all of the opinions in Mobile approved the result

in White V. Regester. The Mobile plurality concluded that White

V. Regester rested upon an intent standard consistent with IVash-

ington v. Davis, and Justice Stevens’ separate opinion did not dis

agree with White V. Regester, nor did Justice Blackmun or the

dissenters.

17

history of official discrimination which touched on the

political processes, historical exemption of blacks from

the political party process, prior use of the poll tax and

restrictive voter registration procedures, and historical

discrimination which resulted in present low levels of

minority voter registration. The perpetuation of the

purposeful political exclusion caused by these prior in

stances of official discrimination compelled the Court to

declare the multi-member districts at issue in violation

of the constitution. It should be noted that the Court

did not undertake an examination of the Texas govern

ment’s motivation in 1970 in designing the districts. Nor

was it considered necessary to demonstrate a causal link

between the particularized effects of the multi-member

districts and prior discrimination. It sufficed to show

that prior purposeful official discrimination caused polit

ical exclusion of racial minorities, that the exclusion

remained, and that it was perpetuated by the multi

member districts.18

A similar perpetuation standard has been consistently

employed in school desegregation cases. In Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968), the Court articulated the duty of a school board

to disestablish an unconstitutional dual school system.

Green said that “ freedom of choice” plans are not un

constitutional per se, but must be invalidated if they

continue the segregative effect of the prior statutorily

mandated dual school system. 13

13 This Court described with approval the District Court’s action

with regard to Bexar County, Texas: “ Single-member districts

were thought required to remedy ‘the effects of past and present

discrimination against Mexican-Americans,’ [343 F. Supp. 704,

733], and to bring the community into the full stream of political

life of the county and state by encouraging their further registra

tion, voting, and other political activities.” White v. Regester,

supra, 412 U.S. at 769. Obviously, the Court felt that the Con

stitution requires eradication of the effects of past and present

discrimination. See Louisiana v. United States, supra, 380 U.S.

at 154.

18

Three years later, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971), emphasized that a

school district has the constitutional duty to eliminate

every vestige of state-imposed segregation. The Court

noted that the Constitution is not satisfied by racially

“ neutral” government actions which allow the effects of

prior unconstitutional discrimination to remain.

“ Racially neutral” assignment plans proposed by

school authorities to a district court may be inade

quate; such plans may fail to counteract the continu

ing effects of past school segregation resulting from

discriminatory location of school sites or distortion

of school size in order to achieve or maintain an

artificial racial separation. When school authorities

present a district court with a “ loaded game board,”

affirmative action in the form of remedial altering of

attendance zones is proper to achieve truly nondis-

criminatory assignments. In short, an assignment

plan is not acceptable simply because it appears to be

neutral.

402 U.S. at 28 (emphasis added). See also Keyes v.

School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 188 (1973). Similarly,

when prior intentional discrimination in the area of vot

ing rights presents black citizens with a “ loaded game

board,” it is constitutionally insufficient to justify as

racially “ neutral” an electoral scheme which leaves the

game board loaded by perpetuating past discrimination.

Only recently, in Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman

{Dayton II), supra, the Court reiterated that a school board

guilty of past intentional discrimination must avoid ac

tions which have “ the effect of increasing or perpetuating

segregation.” The measure of conduct under that duty

“ is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of the actions in

decreasing or increasing the segregation caused by the

system.” Thus, the school board must “ do more than

abandon its prior discriminatory purpose.” It must see

that pupil assignment policies and school construction

and abandonment practices ‘are not used and do not

19

serve to perpetuate or re-establish the dual school sys

tem.’ ” 443 U.S. at 538, quoting Columbus Bd. of Educ. v.

Penick, supra, 443 U.S. at 460.

Dayton II and the other school cases illustrate that

plaintiffs need not prove a direct causal link between

prior discrimination and the discriminatory effects of

the particular decision being challenged. For instance,

if a challenge were brought to a neutrally motivated de

cision about the location of a new school in a formerly

dual— and not yet unitary— system, plaintiffs would not

be required to show that the particular and isolated dis

criminatory effect of the location (such as the projected

one-race character of the school’s enrollment) was the

direct result of prior intentional discrimination; rather,

it need only he demonstrated that the location perpetu

ates the segregation which has resulted from past main

tenance of the dual system. 443 U.S. at 538. See also,

e.g., Flax v. Potts, 404 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 1002 (1972). Similarly, plaintiffs herein need

not show that the effects of the at-large scheme itself

directly resulted from prior discrimination;14 they need

only show that it actually perpetuates the direct effects

of the past intentional discrimination.15

This Court has already made clear that the perpetua

tion principle is not limited to school desegregation cases.

As Chief Justice Burger noted for a unanimous court

in Swann, school cases do not differ from other types of

litigation when it comes to the repair of a denial of

constitutional rights. 402 U.S. at 15-16. Furthermore,

the use of the perpetuation standard in the school deci

14 Certainly there is evidence to make that proof, even though

it is not required. For past discrimination directly caused current

low voter registration levels for blacks and current bloc voting,

both of which severely disadvantage blacks under the at-large

electoral system.

15 As previously noted, this point was also made by the Court’s

analysis in White v. Regester.

20

sions accords with this Court’s emphasis on intent in

other types of equal protection cases. Washington v.

Davis specifically noted that the school desegregation

cases have “ adhered to the basic equal protection prin

ciple that the invidious quality of a law claimed to be

racially discriminatory must ultimately he traced to a

racially discriminatory purpose.” 426 U.S. at 240 (em

phasis added) .18

Moreover, the perpetuation standard was not rejected

in Washington v. Davis, Arlington Heights, and Person

nel Administrator v. Feeney, all of which examined only

the present intent behind challenged enactments, and

not the perpetuation of prior discrimination.* 17 Finally,

by allowing evidence of past history and current impact

in the search for “ ultimate” intent, Washington v. Davis

and Arlington Heights obviously permit application of

the perpetuation standard which links prior intentional

discrimination with the maintenance of discriminatory

effects. Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 242;

Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 267.

The record below and findings of the District Court

amply support the conclusions that (1) prior purpose

ful discrimination resulted in the denial of equal access

to the political process; (2) the effects of the intentional

denial remain; and (3) the denial of equal access is per

petuated by the at-large system.

18 See also Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, supra, 442 U.S.

at 272 ( “ if a neutral law has a, disproportionately adverse impact

upon a racial minority, it is unconstitutional under the Equal

Protection Clause . . . if that impact can be traced to a discrimina

tory purpose.” (emphasis added)).

17 Feeney held that the Massachusetts legislature was not uncon

stitutionally motivated simply because it adopted a veteran’s pref

erence which had the foreseeable effect of perpetuating the fed

eral government’s intentional discrimination against women through

its military policy. But Feeney did not involve a situation where,

as here, the challenged decision is that of the particular govern

mental units whose own prior discrimination is being perpetuated.

21

1. Prior purposeful discrimination

It was not long after the Civil War ended that the

State of Georgia began its successful efforts to disfran

chise the newly freed black citizens. A poll tax was in

stituted in 1871, followed by a cumulative poll tax in

1877 which was specifically designed to eliminate blacks

from the voter registration rolls. The white primary

began its life in Georgia in 1898, with the final blow ad

ministered in 1908 by the passage of a comprehensive

state constitutional suffrage amendment, which included

manipulable tests for literacy and understanding, a prop

erty ownership requirement, and a grandfather clause.

The overwhelming historical evidence shows that all of

these measures were adopted with the express purpose

of preventing blacks from voting.18

The white primary was not struck down until 1946

(J.S. at 74a; Chapman v. King, 154 F.2d 460 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 327 U.S. 800 (1946)), and even after that

blacks remained totally disfranchised in Georgia because

of a combination of state and county government actions,

including the poll tax and arbitrary administration of

the literacy test. (J.S. App., 86a). It was 1965, with 18

18 J. Morgan Kousser, T he Shaping of Southern Politics,

(Yale University Press, 1974), pp. 209-223, 239. It is interesting to

note that the historical background of the 1908 Georgia Amendment

clearly refutes the reasoning of those courts which automatically

conclude that voting measures passed during a time of widespread

black disfranchisement could not have been tainted by discrimina

tory intent. See e.g., McMillan V. Escambia County, Florida, 638

F.2d. 1239, 1244 (5th Cir. 1981); McGill V. Gadsden County Com

mission, 535 F.2d 277, 280-281 (5th Cir. 1976). Despite the fact

that only a few blacks were able to vote immediately prior to 1908

because of the existent poll tax and white primary, the suffrage

amendment was nevertheless passed with the express purpose of

providing extra insurance against blacks ever voting again. Kousser,

supra, at 221. Governments caught in the grip of a period of

racist fever often react with extreme and duplicative measures

which far exceed that which is necessary to accomplish their in

vidious ends. See James Silver, Mississippi: T he Closed Society

(Harcourt, Brace & World, 1964).

22

the passage of the Voting Rights Act, before blacks were

even able to begin registering in significant numbers.

However, in Burke County, Georgia, governmental au

thorities did not give up their fight against black suf

frage, and intentional obstacles continued to be thrown

in the path of black political participation well into the

1970s,1® The County attempted to eliminate all but one

polling place (PI. Ex. 11; T. 42) and maintained only

one registration site for years (J.S. App., 81a), thus

making it difficult for the disproportionately impover

ished black citizens to travel for the purpose of exercis

ing their electoral rights. Voter registration was limited

to one day, with an additional short period on Saturday

morning which itself was later eliminated. (PI. Ex. 7,

10, 41; T. 39, 41, 56).

Furthermore, the District Court’s findings of fact

show that the registration of potential black voters was

being hindered by the County Commissioners’ “ sluggish

ness’ even after commencement of this lawsuit. (J.S.

App., 81a). According to the evidence, blacks for ten

years sought registration sites in each of the 15 voting

districts, but were falsely told by county officials that

registration was illegal unless conducted at the court

house; intervention from the Georgia Secretary of State

was sought before this charade ended. (T. 734). Three

additional sites were finally approved, but were open

only for a few days prior to the 1976 election. (PL Ex.

99; T. 639; see J.S. App., 81a). Even then, there were

instances of intentional efforts by county officials to pre

vent blacks from registering. (T. 319-321, 952).120 The

county steadfastly refused to appoint black deputy regis- * 20

w The Court of Appeals noted that the Burke County Commis

sioners made it necessary for blacks to go to court in an effort

to obtain the right to register and vote. 639 F.2d at 1376-1377.

20 These instances, along with other evidence of political exclu

sion, show that this case is unlike Mobile, where the District Court

found that blacks register and vote “without hinderance.” 446 U S

at 73.

23

trars, despite the willingness of several black citizens to

serve voluntarily. (T. 724, 953-956).

Literacy and understanding tests, long the tools of

black disfranchisement, were readopted by the 1976

Georgia Constitution, Ga. Code § 2-403, and are inopera

tive only because of the Voting Rights Act.

In addition to discrimination touching directly on the

political processes, there is extensive evidence and find

ings regarding the plethora of past official discrimina

tion which pervaded Georgia21 and Burke County in all

walks of life, and which was found by the District to

have caused blacks to suffer inadequate educational op

portunities and overall socioeconomic disparities, which,

in turn, affect their ability to participate in the polit

ical process. (J.S. App. 74a, 81a-84a).22 Cf. Gaston

Comity V. United States, 395 U.S. 285, 297 (1969) (in a

county which previously provided blacks with inferior

educations in segregated schools, “ ‘ [ijmpartial’ adminis

tration of the literacy test today would serve only to

perpetuate these inequities in a different form.” ) .

2. The effects o f the intentional denial remain

As all of this evidence of historical and recent inten

tional discrimination shows, blacks were totally excluded

from the political process until 1965, and continue to

be excluded to a greater degree than whites because of

the discrimination. The District Court specifically found,

21 The District Court took judicial notice of Georgia laws indica

tive of discriminatory intent. (J.S. App., 76a).

22 Based in part on expert testimony, the district court found

that black citizens, suffering from disproportionately greater poverty

than whites, have a generally heightened struggle for the means of

daily sustenance, thereby reducing the time, energy, and opportunity

for participation in the political process. This was held to be a

result of past intentional discrimination. (J.S. App., 83-84 and

n. 19). See Kirksey, supra, 554 F.2d at 145, n. 13.

24

and the Court of Appeals agreed,2,3 that the intentional

exclusion of blacks directly resulted in relatively low

voter registration rates,23 24 * * * * 29 (J.S. App., 71-72; 639 F.2d

at 1377-1378), thus inhibiting the efforts of blacks to

elect candidates who share their political interests. This

low level of registration takes on added significance in

light of the fact that blacks constitute a majority of

the county population. By prior intentional discrimina

tion, government officials have kept black voter registra

tion disproportionately low, thus preventing blacks from

exercising significant political power.

Another consequence of the intentional racial segrega

tion and discrimination practiced for years in Georgia

and Burke County is bloc voting. As the District Court’s

finding indicates, official discrimination created distinct

racial interests which manifest themselves at the polling

places. (J.S. App., 72-73). Blacks, having suffered so

long from the invidious discrimination thrust upon them,

23 All of the relevant district court findings of fact were affirmed

by the Court of Appeals.

24 As previously noted, the district court also found that official

discrimination causing inadequate educational opportunities and

socio-economic disparities which burden black citizens was manifest

in low voter registration levels. The Fifth Circuit recognized the

myriad ways in which racial discrimination can influence such

political factors as voter registration levels: “ Failure to register

may be, for example, a residual effect of past non-access, or of dis

proportionate education, employment, income level or living condi

tions. Or it may be in whole or in part attributable to bloc voting

by the white majority, i.e., a black may think it futile to register.”

Kirksey, supra, 554 F.2d at 145, n. 13.

The principle that low socioeconomic status and deprivations in

education, income, employment and other areas have a negative

impact on opportunities for political participation is firmly estab

lished by numerous studies in political science. See, e.g., L. Mil-

braight, Political Participation, ch. V (1965); W. Erbe-, Social

Involvement and Political Activity: A Replication and Elaboration,

29 A m . Sociological Rev. 198 (1964); A Campbell, et ah, T he

A merican V oter, ch. 17 (1960); A. Campbell, G. Gurin, & W.

Miller, T he V oter Decides 187-99 (1954).

25

maintain their own political agenda geared in part to

escaping racial oppression, and the majority of Burke

County’s white voters obviously do not support that

agenda.'25

Additionally, the Democratic Party in Burke County,

which maintained segregation through the white primary

and other devices of intentional discrimination, is a near

reflection of its former self: the Burke County Demo

cratic Executive Committee was for years all white and

only recently added one black member. The District

Court found that past official electoral discrimination

within and without the party process accounted for the

current dearth of black political participation in party

affairs, which are closely linked to success in the electoral

system as a whole. (J.S. App., 74a-75a, 87a-88a).26

Past intentional discrimination, according to the de

tailed findings of the District Court, also led to the pau

city of appointments of black citizens to the various gov

ernmental boards whose membership is controlled by the

Burke County Commissioners. (J.S. App., 76a, 78a-79a).

This itself is a measure of exclusion of blacks from the

process of government. Moreover, there can be no denial

that service in appointed government positions can pro

vide the familiarity with government and public expo- 25 26

25 This distinguishes the black citizens in Burke County from

other political and special interest groups. Republicans cannot

ascribe their political differences with Democrats to the burdens

of past state-supported racial discrimination. Bloc voting in the

black-white context, by contrast, is the vestige of such discrimina

tion, and therefore, takes on constitutional significance. Certainly,

without past segregation and discrimination, the political interests

of whites and blacks would be much more closely intertwined.

26 The activities of political parties are sufficiently intertwined

with the political process to be considered highly relevant in a case

such as this. See White V. Regester, 412 U.S. at 766-767. See also

Smith V. Allwright, 321 U.S. 642 (1944).

26

sure that is helpful to electoral bids for public office.

Blacks are rarely able to avail themselves of such oppor

tunities because of the exclusionary actions of the Burke

County Commissioners.

All of this intentional discrimination, and its well-

documented effects, combine to create a situation where

blacks were and still are seriously excluded from the

political process.

3. Denial o f equal access is perpetuated by the at-large

system

Even when some black citizens escaped the most bla

tant forms of discrimination, and were able to register

and vote, they found themselves confronted by an at-

large system of electing county commissioners which,

when combined with bloc voting— a continued vestige of

racial discrimination— left their vote devoid of meaning

in the Burke County Commissioners race.27 It is no small

frustration to work for years against the most flagrant

forms of racial injustice to finally gain the freedom to

physically place a ballot in the ballot box, only to see the

power of that ballot consistently emasculated by a more

27 Justice Stevens writes in Mobile that voters from a racial

minority may have a critical impact” on municipal or county-wide

at-large elections, and that their votes are therefore not rendered

meaningless. 446 U.S. at 85, n. 5. This observation is valid only

if black voters choose to provide the “ swing vote” between compet

ing white candidates. But, as indicated by the evidence of racial

bloc voting in the instant case and in others, blacks who have long

suffered from discrimination at the hands of white officials, and

who have long been excluded from the political process cannot

realistically be expected to cast their votes for an unwanted candi

date whose chance for electoral victory hinges upon the fact that

he is white. Moreover, the evidence has shown that even a white

candidate who identifies with black interests in Burke County,

thereby giving blacks a reason to cast their swing vote for him,

will surely suffer defeat at the hands of the bloc-voting white

majority. (J.S. App., 73a).

27

subtle at-large election scheme, which the government

can simply defend as racially “ neutral.”

Rather than seek to ameliorate the effects of political

exclusion, the state and county governments have con

sistently chosen a path which disfavors black citizens.

In addition to the refusal to appoint black deputy regis

trars, the delay in expansion of registration sites, the

failure to appoint black members of government com

mittees, etc., there has been the maintenance of at-large

elections, the exclusionary effects of which were height

ened in the 1960s— after black registration increased—

by the addition of majority-vote and numbered-post re

quirements. (J.S. App., 65, n.2).28

In sum, the government has knowingly perpetuated

the tragic effects of prior intentional racial discrimina

tion against black citizens in Burke County and the

intentional exclusion of those citizens from the political

process by maintaining at-large elections in such a way

that blacks cannot elect candidates of their choice,

whereas in a districting system, such electoral success

would be possible.29

28 The Mobile plurality discounted the significance of numbered

post and majority vote requirements by saying “ they tend nat

urally to disadvantage any voting minority.” 466 U.S. at 74. That

point is irrelevant to the instant analysis, for however those fea

tures impact other voting groups, it is clear that in this case they

disadvantage a racial minority whose political exclusion is directly

caused by intentional discrimination. The fact that they also dis

advantage other groups— say Republicans—whose relative political

exclusion is caused by factors unlinked to lawless discrimination

is of no constitutional consequence.

29 It is not proportional representation which the black citizens

of Burke County seek. Were the black population spread evenly

throughout the county, electoral success would be prevented even

in a districting system because of geographic factors unrelated to

the method of election. The plaintiifs would then have no case.

But the Burke County black population is not so dispersed, and

the plaintiffs seek only that which would occur in the absence of

the at-large system.

28

III. THE OPINION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS IS

INCORRECT INSOFAR AS IT REQUIRES A SHOW

ING OF UNRESPONSIVENESS TO SUSTAIN A

CHALLENGE TO AT-LARGE ELECTIONS.

In an unprecedented departure from decisions of this

Court, the Court of Appeals stated that proof of unre

sponsiveness is a 'prerequisite to a successful dilution

claim, despite the fact that the issue is unnecessary to

resolution of the instant case. Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d

at 1373-1374.®°

Underlying the appeals court’s conclusion was an effort

to understand the Mobile plurality’s treatment of Zim

mer v. McKeithen. According to the Fifth Circuit panel,

the refusal by the Mobile plurality to accept Zimmer in

its entirety reflected disapproval of the failure of the

Zimmer plaintiffs to prove unresponsiveness. But the

Mobile plurality implied no such thing. It disapproved

of Zimmer to the extent that proof of the “Zimmer

criteria” had been construed to necessarily create a pre

sumption of discriminatory intent. 446 U.S. at 73.

Nothing was said about responsiveness in terms of the

Zimmer decision.

Indeed, the Mobile plurality’s statements about unre

sponsiveness flatly contradict the Court of Appeals’ con

clusion. According to the plurality, unresponsiveness “ is

relevant only as the most tenuous and circumstantial

evidence” of the constitutional validity of at-large sys-

30 Since unresponsiveness was clearly proven by the plaintiffs,

according to the District Court and the Court of Appeals, the effect

of the absence of such proof need not be decided in this case. Un

fortunately, however, the Court of Appeals’ decision on this issue

needs to be addressed by this Court in the context of this case, lest

the Court of Appeals and the District Courts within the Fifth Cir

cuit labor in future cases under the misapprehension that it con

stitutes a correct application of the law.

29

terns. 446 U.S. at 74. Certainly, the plurality cannot

be thought to imply that “ tenuous” evidence is a neces

sary prerequisite to a successful lawsuit.

Thus, in an opinion which preceded the Court of Ap

peals’ decision below, another panel of the Fifth Cir

cuit concluded that “ [ajfter Bolden . . . [wjhether cur

rent office holders are responsive to black needs . . . is

simply irrelevant . . .; a slave with a benevolent mas

ter is nonetheless a slave.” McMillan v. Escambia

County, Florida, supra, 638 F.2d at 1249 (5th Cir.

1981).

In other areas “ responsiveness” has been rejected as

an element which defeats a claim of discrimination.

For example, in Arlington Heights, this Court said that

“ a consistent pattern of official racial discrimination”

is not a necessary predicate to a constitutional violation.

“A single invidiously discriminatory government act . . .

would not necessarily be immunized by the absence of

such discrimination in the making of other comparable

decisions.” 429 U.S. at 266, n. 14.

What the Court of Appeals’ ruling condones is the main

tenance of an otherwise discriminatory exclusion of black