Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 30, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. 0424f982-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/67b6ad5a-3db2-43fb-b50a-e2110764b064/newman-v-piggie-park-enterprises-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

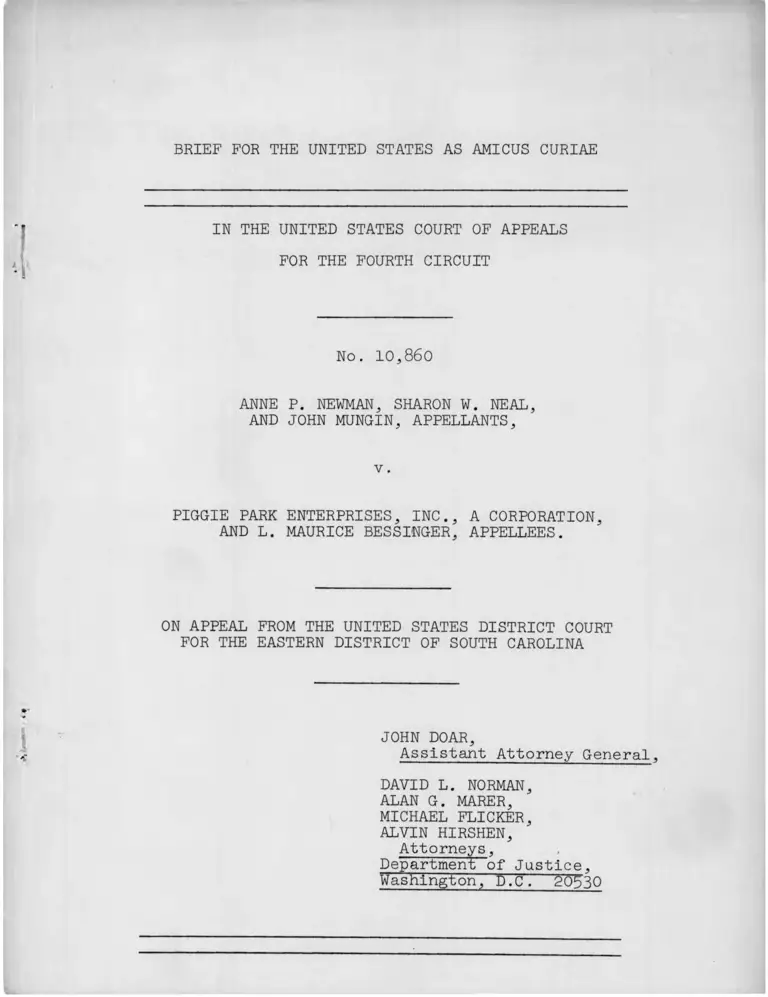

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 10,860

ANNE P. NEWMAN, SHARON W. NEAL,

AND JOHN MUNGIN, APPELLANTS,

v .

PIGGIE PARK ENTERPRISES, INC., A CORPORATION,

AND L. MAURICE BESSINGER, APPELLEES.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

JOHN DOAR,

Assistant Attorney General,

DAVID L. NORMAN,

ALAN G. MARER,

MICHAEL FLICKER,

ALVIN HIRSHEN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530

Interest of the United States -------------------- 1

Statement ---------------------------------------- 2

Specification of Error ----------------------- 7

Argument:

I. Introduction and Summary ------------------- 8

II. The phrase "other facility principally

enSage(i in selling food for consumption

on the premises" was intended to extend

coverage to all establishments like those

enumerated, i.e., to other eating places -- 10

III. The term "principally" excludes only

those establishments engaged in sell

ing food merely as an incident to some other business -- such as,bars and

"Mrs. Murphy" boarding houses ------------- 14

Conclusion---------------------------------------- 27

INDEX

Page

CITATIONS

Cases: page

Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241(1964) ----------------------------------------- 25

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 804(1966) ---------------------------------------- 27

Cuevas v. Sdrales, 344 F. 2d 1019 (C.A. 10,1965) ----------------------------------------- 12,16

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (C.A. 5, 1965) -- 27

Drucker v. Frisina, 219 N.Y.S. 2d 680 (Sup. Ct.1961) ----------------------------------------- 8

Evans v. Fong Poy, 42 Cal. App. 2d 320, 180 P.2d 942 ---------------------------------------- Id

Food Corp. v. Zoning Board of Adjustment, 384Pa. 288, 121 A. 2d 94 ( 1965) -------------- 8

Fraser v. Robin Dee Day Camp, 44 N.J. 480, 210A. 2d 208 ------------------------------------- 26

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) -- 26,27

Lambert v. Mandel's of California, 319 P. 2d469 (Sup. Ct. App. 1957) ------------------------ 25

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 ------------- 5

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 256 F. Supp. 94l (D.S.C. 1966) --------------------------------- 2

Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) ---------- 26

Robertson v. Johnson, 249 F. Supp.618 (E.D. La.1966) ----------------------------------------- 12,16

Rogers v. Katros, 11 R.R.L.Rep. 1503 (N.D. Ala.1966) ----------------------------------------- 24

Tyson v. Cazes, 238 F. Supp. 937 (E.D. La. 1965),

vacated as moot, 363 F. 2d 742 (C.A. 5, 1966) -- 16

United States v. Alabama, 304 F. 2d 583 (C.A. 51962) , affirmed, 371 U.S. 3 7 ------------------- 26

ii

Page

Gases Cont.:

United States v. Chitwood, et al., No. 2385-N(M.D. Ala. 1966) ------------------------------- 25

United States v. Clark, 249 F. Supp. 720(S.D. Ala. 1965) ------------------------------- 25

United States v. Northwest Louisiana Restaurant

Club, 11 R.R.L.Rep. 1505, 256 F. Supp. 151 (W.D. La. 1966) -------------------------- 24

United States v. Original Knights of the Ku

Klux Klan, 250 F. Supp. 330 (E.D. La. 1965) __ 27

United States v. The Warren Co., et al.,

No. 3437-64 (S.D. Ala. 1965) ----------------- 25

STATUTES

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Title II

Section 201(b) ------------------------------- 10

Section 201(b)(2) ----------------------------- 1 2 11Section 201(c)(2) ----------------------------- 5 *

Section 206 ----------------------------------- 2

Section 207(b) -------------------------------- 25

Title VII

42 U.S.C. 1983 --------------------------------- 2

42 U.S.C. 2000a(b)(2) ---------------------------- 2,5,6

42 U.S.C. 2000a(c)(2) -------------------------- 5

42 U.S.C. 2000a-5 ------------------------------ 2

78 Stat. 243 ----------------------------------- 2

MISCELLANEOUS

82 ALR 2d 986 ----------------------------- 9

110 Cong. Rec. 6533 ----------------------------

110 Cong. Rec. 7384 ---------------------------- 12

iii

Miscellaneous Cont.:

110 Gong. Rec. 7404 ------------------------------ 12

110 Gong. Rec. 7405 ------------------------------ 21

110 Cong. Rec. 7406 ------------------------------ 17,21

110 Cong. Rec. 7407 ------------------------------ 17

Hearings before the Senate Committee on Commerce,

88th Cong., 1st Sess., on S. 1732, Part I ----- 22,23

Hearings before the House subcommittee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess; on H.R. 7152:

Part I, p. 652 ------------------------------ 14

Part IV, p. 2655 ---------------------------- 21

Report of the House Judiciary Committee, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., No. 914, on H.R. 7152:

Part 1 (November 20, 1963) ------------------ 12

Part 2 (December 2, 1963) ------------------- 12

Report of the Senate Committee on Commerce, 88th

Cong., 2d Sess., No. 872, on S. 1732, Part I -- 22

Md. Annot. Code, Art. 49B, §11 (1966 Supp.) ----- 18

Page

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 10,860

ANNE P. NEWMAN, SHARON W. NEAL,

AND JOHN MUNGIN, APPELLANTS,

v .

PIGGIE PARK ENTERPRISES, INC., A CORPORATION,

AND L. MAURICE BESSINGER, APPELLEES.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

This appeal presents a question of first

impression concerning the proper interpretation of an

important provision of federal law, section 201(b)(2)

of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

243, 42 U.S.C. 2000a(b)(2). The Attorney General has

independent responsibilities for enforcement of

section 201 and other provisions of Title II of the

Act. See section 206, 42 U.S.C. 2000a-5• For this

reason the United States has a direct and immediate

interest in the proper interpretation of Title II.

Accordingly, we believe that it is incumbent

upon the United States to express its views on the

important question presented here.

STATEMENT

On July 28, 1966, the District Court for the

District of South Carolina (Columbia Division) denied

plaintiffs' request for an injunction against racial

discrimination in defendants' five drive-in establishments,

and granted an injunction with respect to "Little Joe's

Sandwich Shop," also owned by defendants. 256 F. Supp.

941. This is an appeal by plaintiffs from the court's

ruling on the five drive-in establishments.

On December 18, 1964, plaintiffs, who are Negro

citizens, filed a complaint, on their own behalf and as a

class action on behalf of others similarly situated,

alleging violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title

II, section 201(b)(2) and of 42 U.S.C. 19 8 3. The complaint

2

alleged that defendants engaged in racial discrimination

by denying service to Negroes at its six eating places

and that each of them was covered by Title II. A

temporary and permanent injunction was sought against

any future acts of discrimination in any of the establish

ments owned and operated by defendants.

Judge Simons made the following findings of

fact:

Defendants conceded that they cater to white

patrons only and refuse to serve Negroes at their

restaurants for on-the-premises consumption. Two of

the Negro plaintiffs were refused service at one drive-in

without an explanation. Negro customers are served

if they place and pick up their orders at the kitchen

windows provided they do not consume their purchases on

the premises.

All five drive-ins are located at strategic

positions on main and interstate highways. Although

defendants expended some effort in an attempt to avoid

serving interstate travelers, such travelers were served.

Defendants admitted that 18-25$ of the food that it

sold moved in interstate commerce. That estimate

did not include meat purchased from local suppliers who

procured their livestock from out of state.

3

The defendants' drive-ins were operated in

the following manner. Customers drive onto the premises

and into a parking space. Adjacent to and to the left

of each parking space is a "teletray" with an intercom.

Orders are placed by speaking into the intercom. An

employee inside the building, usually out of sight of

the customer, takes the order. A curb girl delivers

the prepared order to the customer, and payment is made

to her. Foods and beverages are served in disposable

paper plates and cups and may be consumed on the

premises in the customer's automobile or may be carried

off the premises and eaten elsewhere. There are minimal

accommodations for sit-down or counter service at

two drive-ins -- two or three small tables with a

couple of chairs at each.

The defendants offered uncontradicted

testimony that off-the-premises consumption averages

50$ during the year. The amount carried out varies during

the year depending on the season and the weather.

The one restaurant against which the injunction

was granted is not a drive-in but a cafeteria-type

sandwich shop known as "Little Joe's Sandwich Shop."

- 4 -

The district court held that defendants’

operation affected commerce within the meaning of

section 201(c)(2) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000a(c)(2),

because it satisfied both of the alternative require

ments of that subsection, that is, a substantial

portion of the food served had moved in interstate

commerce (18-25$ by defendants' admission and about 40^,

or $90,000 a year by the court's calculations, which

properly included meat purchased from local suppliers,

see Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. at 296) and the

defendants both served and offered to serve interstate

travelers.

The issue upon which the case turned was whether

or not defendants' establishments were within Title II,

§201(b)(2) which covers "any restaurant, cafeteria,

lunchroom, lunch counter, soda fountain, or other facility

principally engaged in selling food for consumption on

the premises...." The court found that "Little Joe's

Sandwich Shop" was covered because it provided facilities

whereby customers could sit down and eat within the

building and food is primarily consumed on the premises.

With respect to the five drive-ins, however, the court

reached a contrary conclusion.

The court first considered whether or not the

drive-ins were "restaurants." It came to no conclusion

5

except to cite a number of sources to the effect that

to be a restaurant a place must serve food to be con

sumed on thepremises. 256 F. Supp. at 952-953. The

court found it unnecessary to decide this issue because

it held that to be covered an establishment must in any

event be "principally engaged in selling food for

consumption on the premises."

The court interpreted the phrase "or other

facility principally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises" as requiring that the food be in fact

chiefly consumed on the premises. The court seems to have

looked at two factors in deciding this issue: (1 ) the

percentage of food which actually was consumed on the

premises, and (2) the number and type of facilities which

would encourage customers to eat on the premises. Using

this approach^ it concluded that the drive-ins were not

covered by §201(b)(2) because on the average 50$ of

the food served during the year was not consumed on the

1_/premises^ and there were no facilities for sit-down

1 / Under the plain meaning of the phrase one

who served 50$ or less (sic) of its food

which is taken away and eaten off the

premises cannot be held to be principally

engaged in selling food for consumption

(continued on following page)

- 6 -

dining "sufficient to accommodate any appreciable

number of patrons."

SPECIFICATION OF ERROR

The court erroneously held that a drive-in

eating establishment where on a yearly average 50$

of the food sold is consumed off the premises is not

subject to the non-discrimination requirements of

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

_ 2 _ /

1 / (continued from preceding page)

on the premises. The uncontradicted evi

dence before the court is that only (sic)

50$ of the food serve at defendant's

drive-ins is consumed off the premises and

all of its patrons are encouraged to take

their orders elsewhere for consumption.

256 F. Supp. at 953-

In this quote the court used "50$ or less"; this appears

to be a misprint. The court probably meant 50$ or more.

2/ The court noted as being significant that there

were no accommodations "for diners to walk into build

ings to be served and to eat inside. They [the drive-

ins] cater entirely to motorized customers who do not

alight from their automobiles to order or eat, whose

orders are served in disposable containers, and 50$

of all foods served to them is consumed off the premises."

256 F. Supp. at 952.

- 7 -

ARGUMENT

I . Introduction and Summary

In our view all of the drive-in restaurants

involved in this case are subject to the federal public

accommodations law. To sustain this position we need

not urge that the phrase "principally engaged in serving

food for consumption on the premises" does not modify

"restaurant/' although that is certainly a plausible reading

of the Act. Instead^, we put that question to one side be

cause we think that, in any event, a drive-in restaurant

is an "other facility principally engaged in serving food

for consumption on the premises."

Preliminarily, we observe that a drive-in

restaurant has "premises," i .e . , the parking area where

people are served and may and do conveniently eat in their

cars. Compare Drucker v. Frisina, 219 N.Y.S. 2d 680

(Sup. Ct. 19 6 1); Food Corp. v. Zoning Board of Adjustment,

384 Pa. 288, 121 A. 2d 9^j 95 (1965)- The Food Corporation

case held in a matter involving a zoning law that

a drive-in is to be treated like any other restaurant

- 8 -

"since the food will be consumed there even though it

be in automobiles stationed thereon." (emphasis in the

original). And in Drucker, another zoning case, it was

held that "customers served by carhops or by outside counter

service will nonetheless be on the premises, not on the

public thoroughfare, when the food is served and consumed."

3 /219 N.Y.S. 2d at 682.

We understand the district judge to share the

view that the parking area is a drive-in's premises within

the meaning of title II, for the necessary implication

of his holding that 50$ of the food is consumed off the

premises is that the other 50$ is consumed thereon --

which could only mean the parking area. So, too, the brief

for appellees states that "... as a matter of fact, at

least 50$ of the food sold is consumed away from the

premises ...," and again, in phrasing the question presented,

appellees maintain that "at least fifty per cent of the

food sold is carried away from the premises for consumption

3/ See also Annot., 82 ALR 2d 989, note 2, p. 990;

■^he terms 'restaurant,' 'diner,' and ’drive-in' have

been used [in the annotation] to connote any business

establishment serving edibles for consumption on the

premises at a profit, since this seems to have been the

meaning attributed to those terms in most of the case."

- 9 -

. (Brief for Appellees at 5>6). This must mean that

the other half was eaten on the premises.

So much being conceded,, it seems to us that the

drive-ins here involved are covered. Our position is that

"for consumption on the premises" means suitable for

consumption thereon, or which may conveniently be eaten

thereon, so long as some customers do in fact eat there.

The term "principally", in this view, serves only the

function of eliminating from coverage places whose

main business is not serving food -- typically bars,

cocktail lounges, and taverns -- but which do serve

minimal amounts of food as an incident to some other

activity. We submit that the statutory scheme, the

legislative history, and the policies underlying the Act

all support this interpretation.

II. The phrase "other facility principally engaged in

selling food for consumption on the' premises" was

intended to extend coverage to all establishment's

like those enumerated, i.e., to other eating places

Section 201(b) of the Act makes the prohibition

on discrimination applicable (assuming a "commerce" nexus,

which is not in dispute here) to:

(1 ) any inn, hotel, motel, or other establishment

which provides lodging to transient guests....;

10

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility princi

pally engaged In selling food for consumption on

the premises . . . .

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert

hall, sports arena, stadium or other place of

exhibition or entertainment ....

The underscored phrases are obviously catchalls intended

to extend coverage to establishments similar to those

enumerated. There is no basis whatever for appellees'

suggestion that "the plain and simple language used in

the Act restricts coverage to those facilities

specifically enumerated" (Br. for Appellees at 8-9).

The very opposite is true, since otherwise there would

have been no point to including the general clauses at the

end of each category of listed establishments. As the

House Report said, Section 201(b)(2) covers "restaurants,

lunch counters, and similar establishments." (emphasis

37added). Similarly, Senator Magnuson said on the floor

4 / Senator Magnuson was the Chairman of the Senate

Commerce Committee which reported out one version of a

public accommodations bill, and the principal spokesman

for the House version of Title II when it reached the

Senate floor.

11

that it covered "restaurants, Lunch counters, and other

food-service facilities," LLO Gong. Rec. at 7384, and

again at another point he referred to coverage of

"restaurants, Lunch counters, and similar establishments."

Id. at 7404. Other similar descriptions are to be found

_ v.m the reports.

Both the language and the legislative history,

therefore, indicate that the catchalls are to be read in

accordance with the usual doctrine of ejusdem generis

to reach places like those mentioned but not places quite

dissimilar. See Cuevas v. Sdrales, 344 F. 2d 1019, L020,

(G.A. 10, 1965); Robertson v. Johnston, 249 F. Supp. 618,

622 (E.D. La. 1965) (both applying ejusdem generis to

the catchall phrases following respectively, the restaurant

and amusement clauses). As the Court of Appeals for the

Tenth Circuit said, construing the "principally engaged

etc." clause, "[ajll the places specifically designated

are facilities where food is sold to be eaten," and

went on to say that "[tjhe obvious purpose of Section 201(b)

is to prevent discrimination in places where food is sold

to be eaten." Cuevas v. Sdrales, supra at 1020, 1021. a

drive-in restaurant is also such a place, and it should

therefore be held within the law so long as

5 / See "Additional Majority Views" of Congressman

Kastenmeier (bill covers "eating places"), House Rpt. No.

914, part 1 at 40; "Additional Views" of Congressmen

McCulloch, Lindsay, et al. ("eating establishments"),

House Rpt. No. 914, part 2, at 12-13; "Separate Minority

Views" of Congressmen Poff and Cramer ("eating establishments"), House Rpt. No. 914, part 1 at 98, 99.

12

it sells prepared food and any of that food is consumed on the

premises. Of course any of the enumerated places may

be expected to have a carry-out business, so that is no

ground for excluding drive-ins.

In fact, an examination of the bill as introduced

reveals that the phrase "for consumption on the premises"

was probably included only to distinguish the catchall

"engaged in selling food" from other catchall phrases,

later deleted, appearing in the same subsection of the

bill as introduced and which also covered places selling

J j

unprepared food, notably "markets." It was, then,

a matter of symmetry of draftmanship, rather than any

concern about carry-out service, which explains the

initial inclusion of the "premises" phrase.

Since drive-in restaurants are similar to the

enumerated establishments, they must be held to come within

6 / Of course, a place like a market which is engaged

exclusively in selling unprepared food to be taken home

for preparation is not covered. Compare n. 7 and text

p. 19 and n. 10, infra.

7/ As introduced this section read:

Any retail shop, department store, market,

drug store, gasoline station, or other place

which keeps goods for sale, any restaurant,

lunchroom, lunch counter, soda fountain, or

other public place engaged in selling food for

consumption on the premises, and any other

establishment where goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, or accommodations are

held out to the public for sale, use, rent, or

hire .

(continued on following page)

13

the catchall unless the term "principally" somehow

compels a different result. We show, next, that its

insertion in the bill oy the House Committee was

not intended to deal at all with the relative percentages

of on-and-off premises consumption, but with an entirely

different problem.

Ill. The term "principally" excludes only those

establishments engaged in selling food merely

as an incident to some other Business __

"such as,bars and hMrs. Murphy" boarding houses

In our view the emphasis in the phrase

"principally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises" is properly on the word "food." The

term "principally" did not appear in the bill as intro

duced. It was added by the House Judiciary Committee

and retained in the same form when the House version of

the coverage provisions was ultimately adopted in the

Senate. Its inclusion was not intended to have any

7 / (continued from preceding page)

See Hearings before the House Subcommittee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 652 (part I).

Unless "for consumption on the premises" had

been added to "engaged in selling food" the latter would

overlap "market ... or other place which keeps goods for

sale," as well as the last catchall.

- 14

bearing upon the percentage of food consumed on

the premises, out was intended only to exclude from

coverage places where food service was incidental to.

some other business. One such category of businesses

was bars. Another was small motels and tourist homes

wherein the owner resides which were exempted by the

"Mrs. Murphy" clause from the lodging provisions of

the Act. Congress did not want "Mrs. Murphy" to be

inadvertently covered by the food service provision

in the event she served a minimal amount of food to

her lodgers.

To be sure, there is no explanation in the

House Report as to why "principally" was inserted.

But as introduced the oill would have covered bars, as the

Attorney General testified. See Senate Hearings at 62. Obviously,

- 15 -

if a bar sold peanuts, popcorn or even sandwiches to

its patrons it would have been "engaged in selling food

for consumption on the premises" if the catchall were

read literally. Cf. Evans v. Fong Poy, 42 Cal. App. 2d

320, 321, 180 P. 2d 942, 943 (holding bars included in

a general catchall clause of a state public accommodations

law.) After the bill was passed, however, the legislative

history showed -- and the courts have held -- that bars

were excluded. E.g., statement of Senator Magnuson,

Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee and principal

floor spokesman in the Senate for Title II, that "[a]

bar, in the strict sense of that word, would not be

covered by title II, since it is not 'principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the premises.'"

(110 Cong. Rec. 7406); Cuevas v. Sdrales, 344 F. 2d 1019

(C.A. 10, 1965); Tyson v. Cazes, 238F. Supp. 937(E.D. La.

1965), vacated as moot, 363 F. 2d 742 (C.A. 5); Robertson

v. Johnson, 249 F. Supp. 618 (E.D. La. 1966).

Given the intention of congress to eliminate

bars, the meaning of "principally” comes into clear focus,

for nothing else in the law or in any revisions between

introduction and enactment would have eliminated bars

(and other places) serving food as an incident to other

business -- except the term "principally."

- 16

The legislative history makes clear that

elimination of bars and other places selling food only

incidentally was the object Congress had in mind in

inserting the term. Thus, in discussing "Mrs. Murphy"

establishments Senator Magnuson said (110 Cong. Rec.

at 7406):

Nor would an individual operating an

exempted tourist home or motel lose the

exemption if he served breakfast as an

accommodation to guests. Title II would

cover only those eating places which

served the public and which were facili

ties 'principally engaged in selling food

for consumption on the premises.' The

food-service facility there would not fall

within that coverage, and would have no

effect on the exemption of the lodging facility.

The situation described by Senator Magnuson was one where

food was being sold "for consumption on the premises."

His explanation, therefore, was not that "principally"

had any thing to do with the "on-off-premises" problem,

but that it related to whether a place was "principally"

engaged in something other than selling food -- i.e., in

8 /

furnishing lodging. Indeed, we know of no legislative

8/ See also Senator Magnuson ’ s statement (llo Cons. Rec. at 7407):

A few weeks ago the Senator from Louisiana

stated that he was not clear as to when bars

or nightclubs would be subject to the provi

sions of title II. As a general rule, estab

lishments of this kind will not come within

the scope of the title. But a bar or night

club physically located in a covered hotel

(Gont. on next page)

17

history even suggesting that "principally" was inserted

to eliminate eating places doing a predominant carry-out

service. The total absence of any legislative history

to support such an exemption speaks loudly against it.

The Cuevas decision of the Tenth Circuit also

shows the function "principally" was intended to perform.

The Court of Appeals said that "the section covered eating

establishments and not those principally engaged in selling

drinks," and that the law did not cover "bars and taverns

where the sale of drinks is the principal business."

3 J(emphasis added.) 344 F. 2d at 1022,1023.

8/ (Cont. from preceding page)

will be ocvered, if it is open to patrons of

the hotel. A nightclub might also be covered

under section 201(b)(3), if it customarily

offers entertainment which moves in interstate

commerce. A business which describes itself

as a bar or nightclub would also be covered

if it is "principally engaged in selling food for consumption on the premises." ****(emphasis added).

9/ The court also said that "it was shown that the tav

ern was primarily engaged in selling beer for consumption on the premises.

Compare the Maryland public accommodations law

enacted just the year before Congress passed title II:

For the purpose of this subtitle, a place of

public accommodations means any hotel, res

taurant, inn, motel or an establishment

commonly known or recognized as regularly

engaged in the business of providing sleep

ing accommodations, or serving food ... and

(Cont. on next page)

18

Bars and other places where food service was

merely incidental, and retail stores, including food

markest selling unprepared food, seem to be the only

categories covered by section 202(a)(3) of the bill as

1 0/introduced that the House Committee decided to exclude.

They were excluded for policy reasons not at all appli

cable to drive-in restaurants -- retail stores, food

markets, and the like because discrimination in them

(except in lunch counters) was not a problem (llo Cong.

Rec. 6533, Senator Humphrey); bars for the obvious reason,

we suppose, that the customers of a place mainly devoted

to drinking might be in a frame of mind uniquely

unreceptive to radical

9/ (Cont. from preceding page)

which is open to the general public; except

that premises or portions of premises primarily devoted to the sale of alcoholic

beverages and generally described as bars,

taverns, or cocktail lounges are not places

of public accommodation for the purposes of

this subtitle, (emphasis added) Md. Ann. Code,Art. 49B, §11 (19b6 Supp.).

_10/ Retail markets and other retail stores were eliminated

by striking the clause expressly covering them and the gen

eral catchall at the end of Section 202(a)(3). It is hardly

possible that ''principally'* was also inserted to exclude

food stores, since "engaged in serving food for consumption

on the premises" was alone sufficient to do that and, of course, striking the language expressly covering such

places made what was already clear doubly so. Thus

insertion of "principally" can only be explained as we suggest above. See supra n. J.

- 19 -

revision of long-standing customs; and "Mrs. Murphy"

places because of the countervailing privacy interests

involved. None of these reasons could have motivated

Congress to exclude drive-in restaurants.

Aside from the fact that the legislative history

fails to suggest a reason to exclude places where 50^

of prepared food is carried out, that reading would

exclude other places (apart from drive-ins) which Congress

plainly wanted to cover. If the percentage of carry-out

business is the measure of coverage, then a typical

sit-down restaurant serving large numbers of persons at

tables on the premises would be exempted if it could

show that even more customers carried the food home.

Yet, nothing could be plainer than that Congress intended

to cover all such places, the constitution permitting.

Tested by its application to these other places it must

necessarily extend to, therefore, the district court’s

reading of the Act cannot stand.

20

Furthermore, the legislative history indicates

that a proprietor of a restaurant should be able to know

with substantial certainty if he is covered, and shows

that Congress thought he would need to determine only if

he met the "commerce" tests. There was no suggestion,

so far as we are aware, that a proprietor also would have

to calculate the relative percentages of on-and-off

premises consumption. Thus, Senator Magnuson said (110

Cong. Rec. at 7405, 7406):

The types of establishments covered are clearly

and explicitly described in the four numbered

subparagraphs of section 201(b). An establish

ment should have little difficulty in determin

ing whether it falls in one of these categories.

.... Establishments which sell food on the

premises, and gasoline stations, may be expected

to know whether they serve or offer to serve

interstate travelers, or whether a substantial

portion of the products they sell have moved in

commerce.

* * ■* * ■*

At any rate, it is clear that few, if any, pro

prietors of restaurants and the like would have

any doubt whether they must comply with the

requirements of title II.

Since, as this record shows, the percentage of consumption

on the premises is fluctuating figure depending on the sea

son, weather, and other variables, and is hardly capable of

exact calculation, to make coverage turn on that would be

contrary to congress' intention to make coverage certain.

Nor was the proprietor's need to know if his

establishment was covered the only consideration. As the

Attorney General said (House Hearings, Part IV, at 2655),

"the areas of coverage should be clear to both the pro

prietors and the public."

21

Under the district court's fifty percent test prospective

Negro customers would have no idea whether a drive-in was

covered or not -- thus leaving Negro travelers in much

the same uncertain position, at least with respect to

drive-ins, in which they found themselves prior to passage

of the act. See Senate Report, at 16.

The effort to achieve certainty of coverage was

also directly related to the Congressional desire to end

disputes about who must serve Negroes (compare Senate

Report at 11; Senate Hearings at 215) and, more

importantly, to eliminate the fear that if one proprietor

served Negroes he would lose white customers to like

places that continued to discriminate. Thus, Senator

Magnuson, shortly after noting that "few, if any

proprietors of restaurants and the like would have any

doubt whether they must comply with the requirements of

title II," said that (110 Cong. Rec. at 7406):

It is argued that a formerly segregated restaurant

would lose all its white patrons as a result of

complying with title II. As a practical matter,

that would be a most unlikely occurrence, since

the white customers of the restaurant minded to

leave it would, no doubt, find that its com

petitors were also required by title II to

desegregate; and thus they would gain nothing

by leaving.

But under the district court's construction many drive-

ins would not be covered, yet they would be

22

to all outward appearances the same as those

covered, thus putting the latter at the very

competitive disadvantage Congress was anxious

to avoid. This idea -- that all like places be treated

alike because none could afford to desegregate unless

all did at once -- was a recurrent theme in the course

of the hearings and debates. See, e . g., testimony of

Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall, Senate

Hearings, at 216:

MR. MARSHALL: Senator, it is our experience,

in discussing this with businessmen, over the

past month and a half, in a large number of

meetings, at the White House and with the Attorney

General and businessmen, that in overwhelming numbers

they want to get this problem behind them and that

the reason they don't do it voluntarily is because

they are all fearful that they will have to move

themselves alone, that someone else will lag back

and it will result in loss of business to them ...

it is largely a question of everyone moving at

once, more than any other single thing.

See also, id. at 206; 325-326.

In this connection it is interesting to note that

-r since 1964 many drive-in restaurants have been ordered to

desegregate in compliance with the law, and evidently

none thought to raise the defense sustained below although

23

some, at Least, must have had. a high percentage of

iycarry-out business. See, for example, United States

v. Northwest Louisiana Restaurant Club, 11 R.R.L. Rep.

1505, 256 F. Supp. 151 (W.D. La. 1966), where a decree

was entered enjoining discrimination by the following

listed places, among many others: the "Frosty Kream,"

"Danny’s Drive-In," the "Fairy Queen Super Drive-In,"

the "Frostop Drive-In," the "Ko Ko Mo Drive-In

Restaurant," "Nick’s Linwood Drive-In,” the "Shamrock

Drive-In," and the "Amber Inn Drive-In.” See also

Rogers v. Katros, 11 R.R.L.Rep. 1503. (N.D. Ala. 1966),

where an injunction under title II was entered against

IV We do not find persuasive the suggestion_in appellees

brief that, because chinaware and silverware is not sup

plied, "waitresses [do not return] to inquire whether the

customer is getting along all right ....", and certain

other amenities of service are ignored, these places are

"unique among drive-in facilities" and should not be

covered for that reason. (Brief for Appellees, at 8).

There is no proof that they are so unique; it is common

knowledge that many other drive-ins use paper cups instead

of chinaware, for example. And it would be absurd if

coverage was to turn on such seemingly insignificant de

tails in operation. So long as patrons eat on the premises

(as half of appellees’ customers in fact do) and the pro

prietor makes it possible for them to do so, we see no

basis for distinguishing these places from any other drive-

in. Of course, if such a distinction were to be drawn it

would lead directly to the kind of uncertainty of coverage, consequent competitive disadvantage to substantially_iden

tical places that do serve Negroes, and continuing disputes

and demonstrations that Congress sought to avoid.

Nor do we think it relevant --as the district court evidently did -- that the proprietor's intention is to encourage his customers to carry the food home. Nothing

in the statute makes coverage dependent on such an inten

tion, especially when at the same time the proprietor makes

available a convenient place for them to eat on the

premises.

24 -

the proprietors of the "Kanora Drive-In" and the "Dari

King "; United States v. Chitwood, et al. , No. 2385-N

(M.D. Ala. 1966), where an injunction under Title II was

issued against the proprietors of the "Prattville Dairy

Queen"; United States v. the Warren Co., et al.,

No. 3437-64 (S.D. Ala. 1965), issuing orders to

desegregate against the "Thirsty Boy Drive-In Restaurant,"

the "Chick-N-Treat Drive-In", and the "Glass House Drive-

In;" and United States v. Clark, 249 F. Supp. 720, 724,

727 (S.D. Ala. 19 6 5) where the court held that the

"Thirsty Boy Drive-In" was covered by title II.

Title II is enforceable against proprietors solely

by civil remedies; they cannot be criminally prosecuted for

violating it. See section 207(b). There is thus no reason

to construe it grudgingly and narrowly. As Justice Black,

concurring, said in Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379

U.S. 241, 273 (1964), "Congress exclud[ ed] some

establishments from the Act either for reasons of policy

or because it believed its powers to regulate and protect

interstate commerce did not extend so far." There

is no doubt about the constitutional power of Congress

to reach these drive-ins; and neither appellees nor the district

court have been able to point to any "reason of policy"

to exclude them. Put another way, the law ought to be

liberally construed. Cf. Lambert v. Mandel's of

25

California, 319 P. 2d 469 (Sup. Ct. App. 1957) (state

public accommodations law to be given "a liberal not

12/

a strict, construction"); Fraser v. Robin Dee Day

Camp, 44 N.J. 480, 486, 210 A. 2d 208 (same). The

Civil Rights Act of 1957 has seen given a liberal

construction by the courts. E.g., United States v.

Alabama, 304 F. 2d 583, 591 (C.A. 5, 1962), affirmed

371 U.S. 3 7. And in the varied situations involving

Title II which have come before the appellate courts

it has been broadly applied, except where, as in

Cuevas, the language and legislative history plainly

required a contrary result. See Hamm v . City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306 (1964) (Title II applied retroactively to

invalidate sit-in convictions obtained prior to its

enactment); Rachel v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) (Title

II read broadly to authorize removal of State "sit-in"

prosecution to federal court although other types of

12/ Lambert gave a broad reading to the phrase "all

other places of public accommodation" in the California

law, holding a retail shoe store within the coverage

because it was like enumerated places selling food since

each "is open to the public generally for the purchase of goods."

- 26

prosecution are not removable; compare City of Greenwood

v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808); Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d

226 (C.A. 5, 1965), (Title

II creates exception to anti-injunction statute to permit

federal courts to enjoin pending State "sit-in" prosecution)

United States v. Original Knights of the Klu Klux Klan,

250 F. Supp. 330, 335 (E.D. La. 1965) (three-judge court)

(any douot about Attorney General's standing to enforce

Titles II and VII to be resolved in favor of standing).

It is appropriate thus to read the statute liberally since

its "great purpose" was "to obliterate the effect of a

distressing chapter of our history." Hamm v. City of

Rock Hill, supra at 315•

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully

submitted that the judgment of the district court should

be reversed insofar as it failed to grant relief against

appellees' five drive-in restaurants.

JOHN DOAR,

Assistant Attorney General.

DAVID L. NORMAN,

ALAN G. MARER,

MICHAEL FLICKER,

ALVIN HIRSHEN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530

JANUARY 1967.

- 27 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing

Brief has been served this date by United States air

mail, special delivery, in accordance with the rules

of this Court, to each of the attorneys for the

appellants and the appellees as follows:

Attorneys for Appellants:

Jack Greenberg, Esq.

Michael Meltsner, Esq.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Matthew J. Perry, Esq.

Lincoln C. Jenkins, Jr., Esq.

Hemphill P. Pride, II, Esq.

1107 1/2 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorney for Appellees:

Samuel B. Ray, Jr., Esq.

Barnwell, South Carolina

28 -