Jett v. Dallas Independent School District Brief of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

November 7, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jett v. Dallas Independent School District Brief of Petitioner, 1988. 9ea518fc-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/67cf0be4-18a5-465d-97a6-1ad8ae72d155/jett-v-dallas-independent-school-district-brief-of-petitioner. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

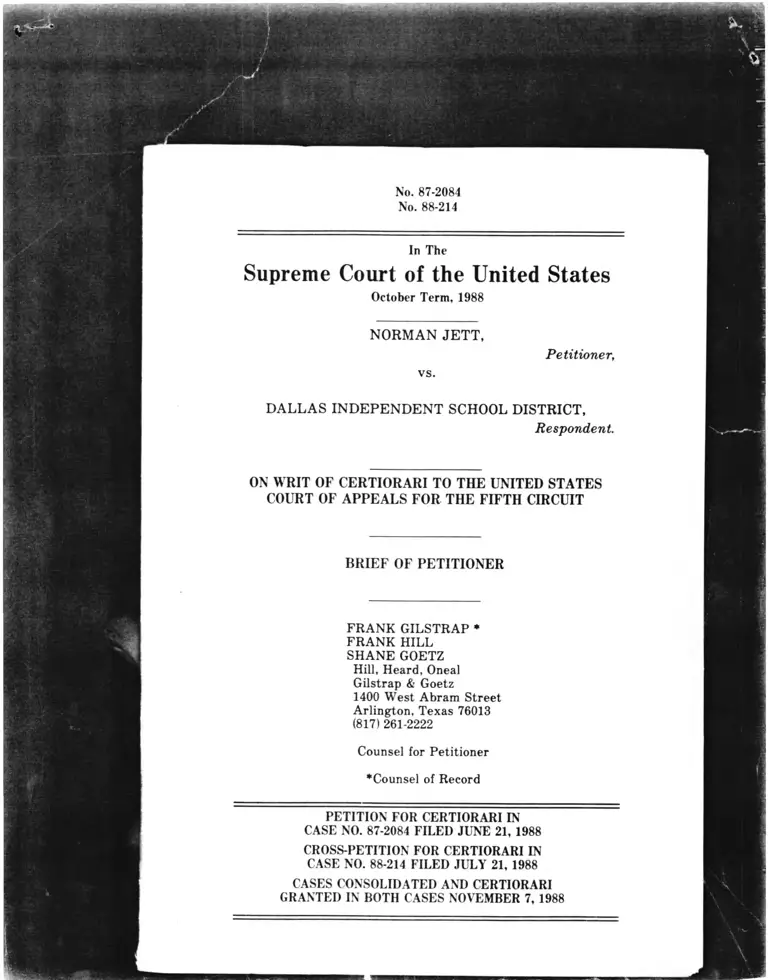

No. 87-2084

No. 88-214

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term. 1988

NORMAN JETT,

Petitioner,

v s .

DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF PETITIONER

FR A N K G ILSTR A P *

FR A N K HILL

SH A N E GOETZ

Hill, H eard, Oneal

G ilstrap & Goetz

1400 W est Abram S treet

A rlington , T exas 76013

(817) 261-2222

Counsel for P etition er

*Counsel of Record

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI IN

CASE NO. 87-2084 FILED JUNE 21, 1988

CROSS-PETITION FOR CERTIORARI IN

CASE NO. 88-214 FILED JULY 21, 1988

CASES CONSOLIDATED AND CERTIORARI

GRANTED IN BOTH CASES NOVEMBER 7, 1988

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Must a local government employee who claims job

discrimination on the basis of race show that the discrimina

tion resulted from official “policy or custom” to recover

from the employer under 42 U.S.C. § 1981?

2. Was the Fifth Circuit’s decision, that a local govern

ment could be liable for damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and

§ 1983 because of an employee transfer decision made by a

non-policymaker, who was not following official policy or

custom, contrary to the recent decision of City of St. Louis

v. Praprotnik,_____ U.S-------- - 108 S. Ct. 915, 99 L.Ed.2d

107 (1988)?

i

LIST OF ALL PARTIES

Petitioner Norman Jett

Respondent Dallas Independent School

District

u

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.......................................... j

LIST OF ALL P A R T IE S .................................................... ^

TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................... m

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................ v

OPINIONS BELOW ................................................ \

JURISDICTION................................................. . . . . . . . . . 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES .2

ST A T E M E N T ........................................................... 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT.......................................... 7

ARGUMENT ................................................................... ........

I. A local government employee who claims job

discrimination on the basis of race need not

show that the discrimination resulted from of

ficial “policy or custom” to recover from the

employer under 42 U.S.C. § 1981........................n

A. The “policy or custom” requirement arose

from the language of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 .........11

1. Background.......................................... n

2. Origin of the "policy or custom” re

quirement ............................................ 12

B. Section 1983 did not amend Section

1981.............................................................. ..

1. Section 1981 was not passed by the

42nd Congress, but by an earlier

Congress............................................. ..

2. Absent clear historical evidence one

cannot conclude that, by passing Sec

tion 1983, Congress imposed a “policy

or custom” requirement on Section

1981.........................................................

3. Congress did not intend for Section

1983 to amend Section 1981.................18

iii

C. The history and language of § 1981 show

that Congress did not intend to include a

“policy or custom” requirement in that

statute .........................................................21

II. The familiar rule of respondeat superior offers

the most suitable standard for § 1981 liability .. 26

A. Considerations of legislative intent require

imposition of a respondeat superior

standard.......................................................26

B. 42 U.S.C. § 1988 also compels adoption of a

respondeat superior standard ...................27

C. Policy arguments favor adoption of a

respondeat superior standard ...................29

1. A rule of respondeat superior will fur

ther the policies of eradicating racial

discrimination, compensating for civil

rights deprivations, and deterring

abuses of power ..................................29

2. Respondeat superior provides a clear,

easily applied standard ...................... 30

3. The policies that favor restricting

liability under Section 1983 do not ap

ply to Section 1981..............................30

4. Other a lternatives..............................31

III. There was evidence from which the jury could

conclude that Superintendent Wright was a

“policymaker” with regard to transfers of

coaches and athletic directors............................ 31

CONCLUSION....................................................................33

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adickes v. S. H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144, 90 S.Ct

1598,2 L.Ed. 142 (1970).....................................................

Bates v. City of Houston, 189 S.W. 2d 17 (Tex. Civ.

App. - Galveston 1945, writ re f d w.o.m.)...................... 29

Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed, Narcotics Agents, 403

U.S. 388,91 S.Ct. 1999,29 L.Ed.2d 619 (1971)..................30

Board of Regents v. Tomanio, 446 U.S. 478, 100 S.Ct

1790,64 L.Ed.2d 440 (1980)....................................... 29

Burnett v. Grattan, 468 U.S. 42, 104 S.Ct. 2924, 82

L.Ed.2d 36 (1984) .......................................................... 29

Butz v. Economou, 483 U.S. 478, 98 S.Ct. 2894 57

L.Ed.2d 895 (1978) ........................................................ 33

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 99

S.Ct. 1946,60 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979).....................................27

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247, 98 S.Ct. 1042, 55

L.Ed.2d 252 (1978) ........................................................... 29

Carlson v. Green, 446 U.S. 14, 100 S.Ct. 1468,

64 .Ed.2d 15 (1980) ..................................................... 29,30

Chapman v. Houston Welfare Rights Organization,

441 U.S. 600,99 S.Ct. 1905,60 L.Ed.2d 508 (1979)......... 17

City of Galveston v. Posnainsky, 62 Tex. 118

(Tex. 1884)....................................................... 29

City of Gladewater v. Pike, 727 S.W.2d 514

(Tex. 1987)........................................................................ g9

City of Houston v. Quinones, 142 Tex. 282,

177 S.W.2d 259(1943)....................................................... 29

City of Midland v. Hamlin, 239 S.W.2d 159

(Tex. Civ. App. - El Paso 1950, no w rit).......................... 29

City of Newport v. Fact Concerts, Inc., 453

U.S. 247,101 S.Ct. 2748,69 L.Ed. 616 (1981)............. 26,30

City of Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808,

105 S.Ct. 2427,85 L.Ed.2d 791 (1985)....................13,27,33

v

Cases Page

City of Orange v. LaCoste, Inc.,

210 F.2d 939 (5th Cir. 1954)............................................. 29

City of Round Rock v. Smith,

687 S.W.2d 300 (Tex. 1985)............................................. 29

City of S t Louis v. Praprotnik,

108 S.Ct. 915,923 (1988)................................... i, 9,12,14

.......................................................................... 27,30,31,32

City of Wichita Falls v. Lewis, 68 S.W.2d 288,

(Tex. Civ. App. - Fort Worth 1934, writ dism’d) ........... 29

ContreUi Trust v. City of McAllen,

465 S.W.2d 804 (Tex 1971).................................. 29

Corfield v. Coryell, 4 Wash. C.C. 371,

6 Fed. Cas. 546 (1823)........................................................19

Corpus Christi Independent School D ist v. Padilla,

709 S.W.2d 700 (Tex. App. - Corpus Christi 1986,

no writ) ............................................................................ 32

Crow v. City of San Antonio, 294 S.W.2d 899 (Tex.

Civ. App. - San Antonio 1956, no writ) ........................... 29

Dilley v. City of Houston, 148 Tex. 191,

222 S.W.2d 992(1949)........................................................29

District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418,

93 S.Ct. 602,34 L.Ed.2d 613 (1973)...................................21

Fielder v. Casey, 108 S.Ct. 2302,

101 L.Ed.2d 123(1988)......................................................29

General Building Contractors Ass'n v. Pennsylvania,

458 U.S. 375,102 S.Ct. 3141,73 L.Ed.2d 835 (1982)........20

Great American Federal Savings & Loan Ass n

v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366, 99 S.Ct. 2345,

60 L.Ed.2d 957 (1979)........................................................18

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88, 104 91 S.Ct.

1790,29 L.Ed.2d 338 (1971).............................................. 24

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 59 S.Ct. 954,

83 L.Ed. 1423 (1939)......................................................... 21

vi

Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409, 96 S.Ct. 984

47 L.Ed.2d 128(1976)...................................................... 26

James v. Bowman, 190 U.S. 127, 23 S.Ct. 678,

47 L.Ed. 979 (1903).......................................................... 24

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454,

95 S.Ct. 1716,44 L.Ed.2d 295 (1975).......................... 27, 28

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409,

88 S.Ct. 2186,20 L.Ed2d 1189 (1968)............ 15,16,19

....................................................................23,25,26,27! 29

Lynch v. Household Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538,

92 S.Ct. 1113,31 L.Ed.2d 424 (1972).....................17,18,20

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 91 S.Ct. 2151,

32 L.Ed.2d 705(1972)........................................................30

Monell v. Dept, of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658,

98 S. Ct. 2018,56 L.Ed.2d 611 (1978)...................8,9,12,14

....................................................................19,22,26,28,30

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 81 S.Ct. 473,

5 L.Ed.2d 492 (1961)....................................... 11,15,28,30

Moore v. County of Alameda, 412 U.S. 693,

93 S.Ct. 1785,36 L.Ed.2d 596 (1973)................................28

N.C.A.A. v. Tarkanian,

109 S.Ct. 454 (1988)......................................................... 14

Occidental Life Ins. Co. v. E.E.O.C., 432 U.S. 355,

97 S.Ct. 2447, 53 L.Ed.2d 402 (1977)................................29

Owen v. City of Independence, 445 U.S. 622,

100 S.Ct. 1398,63 L.Ed.2d 673 (1980)........................ 26,30

Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S. 527,

101 S.Ct. 1908,68 L.Ed.2d 420 (1981)...............................30

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

108 S.Ct. 419 (1988), per curiam .......................................14

Paul v. Davis, 424 U.S. 693,

96 S.Ct. 1155,47 L.Ed.2d 405 (1976).................................30

Pembaur v. City of Cincinnati, 106 S.Ct 1292,

89 L.Ed.2d 452 (1986)............................................9,10,13

........................................................ 14,31,33

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547, 87 S.Ct. 1213,

18 L.Ed.2d 288(1967)....................................................... 26

eases Page

Cases Page

Posadas v. National City Bank, 296 U.S. 497,

56 S.Ct. 349,80 L.Ed. 351 (1936)......................................15

Robertson v. Wegmann, 436 U.S. 584, 98 S.Ct.

1991,56 L.Ed.2d 554 (1978)....................................... 29,30

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

96 S.Ct. 2586,49 L.Ed.2d 415 (1976).....................14,23,27

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1971)................................................................... 18

Sarmiento v. City of Corpus Christi

465 S.W.2d 813 (Tex. Civ. App. - Corpus

Christi 1971, no w rit)........................................................29

Scheurer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 94 S.Ct.

1690,40 L.Ed.2d 90 (1974)................................................ 26

Schroggins v. City of Harlingen, 131 Tex. 237,

112 S.W.2d 1035(1938)......................................................29

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 65 S.Ct. 1031,

89 L.Ed. 1495,162 A.L.R. 1330 (1945) ............................ 22

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall 1136, 83 U.S. 36,

21 L.Ed. 394 (1872)......................................................21,30

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 3% U.S. 229,

90 S.Ct. 400,24 L.Ed.2d 386 (1969)...................................27

Tenny v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367, 71 S.Ct. 783,

95 L.Ed. 1019 (1951)......................................................... 26

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 61 S.Ct. 1031,

85 L.Ed. 1368 (1941)....................................................14,17

United States v. Gradwell, 243 U.S. 476, 37 S.Ct.

407,61 L.Ed. 857 (1917)....................................................17

United States v. Henderson, 78 U.S. 652, 11 Wall 652,

206 L.Ed.2d 235 (1870)......................................................15

United States v. Morris, 125 F. 322

(E.D. Ark. 1903) ............................................................... 19

United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383,

35 S.Ct. 904. 59 L-Ed. 1355 (1915).............................. 16.17

United States v. Price, 393 U.S. 787,

86 S.Ct. 1152,16 L.Ed.2d 267 (1960).....................14,25,26

viii

Cases Page

United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214, 2 Otto, 23 L.Ed.

563(1875).......................................................................... 25

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70, 71 S.Ct.

581,95 L.Ed. 758 (1951)........................................ 16,22,24

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Company, 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970).......................................18

Williams v. Butler, No. 83-2534, No. 83-2641

1988 WL 135650 (8th Cir., filed Dec. 21, 1988)

(en banc)............................................................................ 13

Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 260, 105 S.Ct. 1938,

85 L.Ed.2d 2545 (1985)......................................................29

Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 95 S.Ct. 992,

43 L.Ed.2d 214 (1975)....................................................... 26

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

U.S. Constitution

14th Amendment ..............................................15,25,30

15th Amendment....................................................24,25

STATUTES

United States Code

18 U.S.C.

§241.........................................................................16,24

§242 .............................................................................. 22

28 U.S.C.

§1331............................................................................ 17

§1343(3) ................................................................. 17,18

42 U.S.C.

§1981.................................................................6,7,8,11

....................................14.15,18,21,26,27,28,29,30,31

§1982 ........................................................ 15,23,27

IX

§ 1983 .......................................................... 6,7,8,11,12

......................................... 14,15,17,18,21,22,26,30,31

§1986........................................................................... ....

§ 1988 ........................................................................ 9,27

Revised Statutes

§ 5506 ....................................

§ 5507 ..............................

§ 5508 .......................................................

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866

(c. 31,14 Stat 27)..................................................7,8,14,15

.................................................. 16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27

Civil Rights Act of May 31, 1870

(c. 114,16 Stat 140).......................................... 14,15,16,17

Civil Rights Act of April 20, 1871

(c. 114,17 Stat 13).....................

Texas Education Code

§13.351 .................................................................... 32

§ 23.26 ............................................................................

....7 ,11,12,15

17,18,19,20,21

17.23.24

23.24.25

16,17,23

CONGRESSIONAL GLOBE, 39TH CONG.,

1STSESS ..................................................... 19,20

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1988

No. 87-2084

No. 88-214

NORMAN JETT,

Petitioner,

DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The initial Court of Appeals opinion is reported at 798

F.2d 748, and is reprinted in the Appendix to the Petition

for Writ of Certiorari (“Pet. App.”), at 1A-32A. The Fifth

Circuit’s order on rehearing, supplementing its initial opi

nion, is reported at 837 F.2d 1244, and is reprinted at Pet.

App. 33A-44A. The opinion of the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Texas, Dallas Division, is

unreported and is printed at Pet. App. 45A-63A.

1

JURISDICTION

The Fifth Circuit entered its judgment on August 27,

1986, and issued its mandate on February 5,1988. Pet. App.

66A-67A. Norman Jett timely filed his petition for writ of

certiorari on June 21, 1988, and the Dallas Independent

School District timely filed its cross-petition on July 21,

1988. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §

1254 (1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

The following statutes and constitutional provisions are

involved in this case:

United States Constitution

- Thirteenth Amendment

- Fourteenth Amendment

(Sections 1 and 5)

- Fifteenth Amendment

United States Code

18 U.S.C. § 241; 18 U.S.C. § 242; 28 U.S.C. § 1331;

28 U.S.C. § 1343; 42 U.S.C § 1981; 42 U.S.C. § 1983;

42 U.S.C. § 1988;

Rexnsed Statutes (1874)

Sections 5506, 5507 and 5508

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of April 9,1866 (c. 31,14 Stat. 27),

the “Civil Rights Act of 1866.”

Civil Rights Act of May 31, 1870 (c. 114, 16 Stat.

140), the “Enforcement Act of 1870.”

Civil Rights Act of April 20, 1871 (c. 114,17 Stat.

13), the “Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.”

The above-cited constitutional provisions and statutes

are reprinted in full in the Joint Appendix (hereafter “Jt.

App.”).

2

STATEMENT

Background

Norman Je tt became an employee of the Dallas Indepen

dent School District ("DISD”) in 1957. In 1962 he became a

teacher and assistant football coach at South Oak Cliff High

School. In 1970 he became head coach and athletic director,

while retaining his teaching position. During this period the

racial composition of the school was changing from

predominantly white to predominantly black. By 1982, when

the events that gave rise to this litigation arose, the South

Oak Cliff student body was virtually all black, and Je tt was

the only white coach.

Je tt apparently served well as a teacher. He was regular

ly evaluated and his marks were uniformly high. Tr.

203-205,264-266. It was as a football coach, however, that he

distinguished himself. During his thirteen years as head

coach, Je tt’s South Oak Cliff teams won over eighty percent

of their games and became the dominant high school team in

Dallas. Two hundred fifty of his players won college scholar

ships and forty three of them went on to play professional

football. Tr. 220-221, 223-224.

What proved to be Je tt’s last game occurred in the late

fall of 1982, when his team lost a playoff game to Plano High

School before a large turnout in the Cotton Bowl. The loss

was a bitter one, and it deeply affected Frederick Todd, who

had served as South Oak Cliff principal since 1975.

Despite the team’s great success, Todd had not been

totally satisfied with Jett. On several occasions Todd had

urged Jett to recruit promising middle school athletes, but

the practice was forbidden by DISD regulations, and Jett

had refused. Je tt’s comments to the local newspapers —

that many of his players could not meet new academic stan

dards for college athletes — also rankled Todd.

Todd recommends Je tt’s removal

Immediately following the Plano loss, Todd criticized Jett

for failing to follow the “game plan.” He also quizzed Jett

about an absurd rumor that Je tt had been bribed to “throw

the game.” Soon afterward he gave Jett an unsatisfactory

teacher evaluation, the first in Je tt’s twenty-six years with

3

DISD. On March 15,1983, Todd summoned Jett to his office

* and told him that he was recommending his removal as

athletic director/head coach.

Two days later Todd sent a letter to John Kincaide, DISD

athletic director, formally recommending that Je tt be

removed as athletic director/head coach. Todd’s purported

reasons, as set forth in this letter and in his testimony, were

Je tt’s “improper” comments to the newspapers, his failure

to recruit junior high school athletes, and his failure to

follow the “game plan” in the Plano game. Tr. 77-79, 86-90,

100-108, 174-175, 204, 207.

The jury would later find that Todd was motivated by

Je tt’s race and by Je tt’s exercise of First Amendment

rights, and that the stated reasons were pretextual. Jt.

App. 36-38, 42-44. These findings were upheld by the Fifth

Circuit and are no longer in dispute. Pet.App. 14A-20A.

DISD policies and practices

Under DISD practices Je tt’s removal as athletic director/

head coach was treated as a “reassignment”. No loss in

salary was contemplated. And, while the DISD Board of

Trustees had approved written policies to deal with teacher

reassignments, it had promulgated none concerning

reassignment of coaches and athletic directors. Jt. Ap.

65-66.

DISD Superintendent Linus Wright described transfers

of athletic directors and coaches as occupying a “gray area,”

where matters were left up to him and his subordinates, and

Wright had instituted “practices” to deal with such

transfers. Jt. App. 68, 70. He could appoint a panel to hear

the matter and make a recommendation, or there could be

an informal hearing before him. Jt. App. 69. In either event

Wright made the final ruling, and there was no appeal from

his decision to transfer an athletic director or coach. Jt.

App. 65, 69-70.

Superintendent Wright

upholds Todd’s decision

Following the March 15 meeting with Todd, Je tt met with

Kincaide. Tr. 21. Kincaide told Jett that, since he had

received nothing in writing, he should return to the school

However, as Jett was leaving Kincaide’s office, he met

4

another administrator, who sent him to meet with John San-

tillo, DISD personnel director. After hearing Je tt’s story,

Santillo told Jett that the damage was done and that he

should allow himself to be removed from South Oak Cliff.

When Jett protested, Santillo took him to meet with

Wright. Tr. 271-275.

During this meeting, Je tt told Wright and Santillo that he

believed that Todd s recommendation was racially

motivated. Jt. App. 71-72, 76. Wright’s response was to sug

gest that Je tt consider leaving the school, since he and Todd

were having difficulty. Wright said that he had every con

fidence in Je tt and that he would find him another position.

Jt. App. 71-72.

On March 25,1983, Wright convened a meeting with San

tillo, Kincaide, Todd, and two other administrators. Jett

was not invited since, according to Wright, the informal

March 15 meeting had constituted the hearing required by

Wright’s transfer policy. Tr. 405. At the end of the meeting

Wright officially ordered Jett removed as athletic/director

coach. Jt. App. 72-73, 77.

The jury found that Wright’s decision was “based wholly

on Todd’s recommendation without any independent in

vestigation. Jt. App. 41, 46. Although there is evidence

that Wright ordered Kincaide to investigate Je tt’s allega

tions, Kincaide apparently did not do this, once he learned

that Je tt had met with Wright and Santillo. Tr. 620, 627.

Santillo testified that no investigation was in fact con

ducted. Jt. App. 77.

There was evidence from which the jury could conclude

that Wright simply resolved the conflict in favor of the

principal and that he made no attempt to decide if there was

any truth to the allegation of racial discrimination. Jt. Add.

68. FF

The Aftermath

Jett was reassigned to the Business Magnet High School

because, he was told, it was the only position available. Tr.

279-280. Jett was undergoing a great deal of emotional

stress, and the Business Magnet principal suggested that

Je tt take some time off. Tr. 291-292. When Santillo learned

of this, he sent a letter to Jett expressing “disappointment”

at Je tt’s attendance. Tr. 292-293.

When Jett received the letter, he went to Santillo, who

5

, again took him to Wright. This time Wright told Jett that

he would be “considered” for any head coaching positions

that might come open. Tr. 293-294, 437-438.

On May 5,1983, Santillo wrote Jett a letter and told him

he was being placed on the “unassigned personnel” budget

and that he had been assigned to the security department.

While Je tt should not expect to be able to remain in the

department next year, Santillo said, Je tt could “pursue”

any available position for which he was certified. Further, if

Je tt was not recommended for a coaching position, he would

be assigned as a classroom teacher. Je tt decided that

Wright did not intend to keep his promise to give him the

next available head coaching job, and filed suit. Tr. 359,

371-372.

Subsequently, a head coaching job did open up at Madison

High School; however, Je tt was not contacted regarding

that position, apparently because he had filed suit. Tr.

317-319, 452, 621-622.

On or about August 4, 1983, Je tt received notice that he

had been assigned to Thomas Jefferson High School as

freshman football/track coach. Tr. 305-306. Je tt resigned

rather than accept this humiliating demotion. Tr. 307-311.

The remaining issues

Jett claimed several civil rights violations, only three of

which are still before the Court.1 First he alleged that the

decision to transfer him because of his newspaper

statements violated his First Amendment rights, and gave

rise to a cause of action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Next he

claimed that the decision to transfer him because he was

white violated his Fourteenth Amendment equal protection

right, again giving rise to a Section 1983 claim. With regard

to the racially motivated transfer, Jett also claimed a viola

tion of 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Todd’s liability under all three theories has been

established. At issue here is only the liability of DISD.

1 See Pet. App. 7-8 for the disposition of the other claims.

6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

We answer the first question by determining Congres

sional intent. The Fifth Circuit approached the problem

from the wrong direction. It sought the intent of the Con

gress which enacted Section 1983. Instead it should have

sought the intent of the Congress which passed Section

1981.

The forerunner of Section 1983 was passed by the 42nd

Congress in § 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. Section

1981, on the other hand, was enacted by an earlier Con

gress. The Fifth Circuit apparently reasoned that, by pass

ing Section 1983, the 42nd Congress had somehow amended

the earlier statute to impose Section 1983’s “policy or

custom” requirement onto that statute as well.

This reasoning quickly encounters difficulty. Congress

normally amends an existing statute by express act. Absent

this, amendment can only occur through a process

analogous to “repeal by implication.” Such repeals are not

favored, and this is especially so where Reconstruction era

civil rights statutes are involved. In our case there is no

clear expression that the 42nd Congress intended to impose

a “policy or custom” requirement on the already existing

statute. On the contrary, there is strong indication that Con

gress intended for the two statutes to apply differently.

Section 1981 originated as § 1 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act,

and the 1866 Congressional debates indicate that Congress

passed this statute to secure a set of specific rights to the

newly freed slaves. These rights were enumerated in the

statute and, in the legal thinking of the day, were seen as

“fundamental” or “natural” rights.

When the 1871 Congress drafted Section 1983, it modeled

it after § 2 of the 1866 Act. It made an important change in

wording, however. Instead of the specific list of “fundamen

tal rights” secured by the 1866 statute, Section 1983

secured “any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by

the Constitution.” Ultimately this language was held not to

cover the “fundamental rights” protected by the 1866 Act.

Thus the 1871 Congress did not intend to amend Section

1981.

The proper way to construe Section 1981 is by reading

the history and language of that statute, not Section 1983.

7

In other words, we must ask how Section 1981 would be con

strued if Section 1983 had never been passed.

First, however, we must know exactly what to look for.

The question again is this: Does Section 1981 contain a

“policy or custom” requirement? To answer this, we must

first recall just how the Monell Court went about finding a

“policy or custom” requirement in Section 1983. A review of

Monell reveals that the Court derived the “policy or

custom" requirement entirely from certain “crucial terms”

of Section 1983.

These “crucial terms” provide an avenue of inquiry into

the 1866 Civil Rights Act. In fact the “crucial terms” of Sec

tion 1983 come directly from § 2 of the 1866 Act. Does that

mean that Congress intended to include a “policy or

custom” requirement in § 2 of the 1866 Act? Probably not.

Section 2 was a criminal statute, and because of this it’s

unlikely that Congress had a “policy or custom” require

ment in mind in 1866.

Yet, even if we assume that § 2 of the 1866 Act somehow

does embody a “policy or custom” requirement, that doesn’t

mean that a similar requirement appears in § 1.

Of course, the language of § 1 is totally different from § 2,

and Section 1981 comes from § 1 of the 1866 Act, not § 2.

Moreover, the “crucial terms” in § 2 are highly restrictive.

Because this restrictive language was not placed in § 1, nor

in any other part of the 1866 Act aside from § 2, it follows

that Congress did not intend to impose the language-

specific “policy or custom” requirement on § 1, and hence on

the modern Section 1981.

Once we conclude Congress did not intend to impose a

“policy or custom” requirement on Section 1981, we turn to

the task of determining just what Congress did intend. As it

turns out, there is no clear indication of Congressional in

tent that pertains to our problem. Under these cir

cumstances there are two routes we can take. Both lead to

the same place.

The first alternative is to read Section 1981 in the light of

the common law principles that were widely known in 1866.

This is the approach that the Court took in the Section 1983

immunity cases. The prevalent legal doctrine in the middle

of the 19th Century turns out to be respondeat superior.

8

The second approach is to follow 42 U.S.C. § 1988, and

either adopt the rule of the state in which the suit was filed

or fashion a single federal rule. The applicable state law is

Texas law, and there the doctrine of respondeat superior is

strong. On the other hand, if the Court fashions a single

federal rule, then general common law concepts must again

be called upon, and again we wind up with respondeat

superior.

In making its choice the Court is permitted to consider

the policies behind the civil rights statutes. Certainly the

policies of eliminating racial discrimination, discouraging of

ficial misconduct, and compensating civil rights depriva

tions are well established. There are, however, other fac

tors which the Court should also consider.

First, the Court’s decade of struggle with Monell’s

“policy or custom" requirement should illustrate the need

for a simple, widely understood standard. Again the rule of

respondeat superior fits better than any other.

Second, recognition of a respondeat superior standard

will not lead to an expansion of liability under Section 1981,

such as occurred with Section 1983. Section 1983 has grown

because of its broad language, which can arguably encom

pass almost any kind of government activity. Section 1981

has different language, however. It secures a narrow set of

enumerated rights, and there is no danger that the scope of

Section 1981 liability will become unmanageable.

Finally, we turn to the second Question Presented. As

framed, the Question answers itself at least insofar as Sec

tion 1983 is concerned. Obviously we can’t satisfy the

“policy or custom” requirement unless Wright was a

policymaker with regard to transfers of coaches. That’s ex

actly what Pembaur says but, then again, that’s exactly

what the Fifth Circuit said in our case.

Analyzing the facts of our case in the light of Pembaur

and Praprotnik, we ask first where applicable state law

places the policymaking role. Our inquiry is necessarily

brief. Texas statutes don’t say whether school district

superintendents can or cannot make policy. Nor does our

record contain any direct evidence as to whether the DISD

school board actually made such a delegation to Superinten-

9

dent Wright, although that fact can be inferred. The lack of

direct evidence comes as no surprise, since the case was

tried before Pembaur. Obviously, this part of the case must

be retried, hopefully after further clarification of the “policy

or custom” requirement.

10

ARGUMENT

I. A local government employee who claims job

discrimination on the basis of race need not show that

the discrimination resulted from official “policy or

custom” to recover from the employer under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981.

A. The “policy or custom" requirement arose

from the language of 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

1. Background

In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 81 S.Ct. 473, 5 L.Ed.2d

492 (1961), the Court held that Chicago police officers acted

under “color of law” when they invaded and ransacked a

home without a search warrant. They were therefore liable

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.365 U.S., at 171-187. Their municipal

employer, however, was not liable, since Congress did not

intend to include municipalities among the “persons" liable

under Section 1983. 365 U.S., at 187-192.

Both Monroe holdings were based on the Court’s reading

of Congressional intent. Section 1983 “came onto the books

as section 1 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20,1871.17 Stat 13,”

365 U.S., at 171, and the Court relied on the 1871 Congres

sional debates to support its holding that policemen could

act under “color of law”, even though their actions might be

contrary to the “ordinances or regulations” of their

municipal employer. 365 U.S., at 171-183.

The Monroe court also examined the 1871 debates with

regard to its second holding, i.e., that the City of Chicago

was not a “person” liable under § 1983. There the Court

focused on the debates over § 6 of the 1871 statute^ather

than § 1. At issue was the amendment proposed by

Representative Sherman which would have imposed liabili

ty upon “the county, city, or parish” in which certain violent

acts occurred. 365 U.S., at 189 n. 41. The Sherman Amend

ment was defeated, and the Monroe Court concluded that

‘Now 42 U.S.C. § 1986.

11

Congress’ response to the proposed measure “was so an

tagonistic that we cannot believe” that Congress intended

to include municipalities among the “persons” liable under

§1 of the Act. 365 U.S., at 191.

Seventeen years later in Monell v. D ept of Social Ser

vices, 436 U.S. 658, 98 S. Ct. 2018, 56 L.Ed.2d 611 (1978), the

Court re-examined the Sherman Amendment debates and

concluded that it had misread them in Monroe. “Congress

did intend for municipalities and other local government

units to be included among those persons to whom § 1983

applies.” 436 U.S., at 690 (emphasis in original).

2. Origin of the “policy or

custom" requirement

In Part II of Monell the Court began to define the newly

recognized governmental liability. First it held that “a

municipality cannot be held liable under § 1983 on a

respondeat superior theory." 436 U.S., at 691. It then for

mulated the standard by which local governments could be

held liable—the now familiar “policy or custom” require

ment. Id., at 694-695. The Sherman Amendment debates,

crucial to Part I of Monell, were called upon only once in

Part II, to bolster the rejection of respondeat superior. 436

U.S. at 691 n. 57. They played no role in formulating the

“policy or custom” requirement. Instead, throughout Part II

of Monell, the Court relied exclusively on “the language of §

1983 as originally passed,” i.e., § 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act

of 1871, which read as follows:

[Afny person who, under color of any law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of any

State, shall subject or cause to be subjected. . .

436 U.S., at 691 (emphasis the Court’s). The Court wrote

that this language “imposes liability on a government that,

under color of some official policy, ‘causes’ an employee to

violate another’s constitutional rights.” 436 U.S., at 692.

In City of S t Louis v. Praprotnik, 108 S.Ct. 915, (1988),

the Court again emphasized this language. There it wrote

that “the crucial terms of the statute are those that provide

for liability when a government ‘subjects [a person], or

causes [that person] to be subjected,’ to a deprivation of con

stitutional rights." 108 S.Ct., at 923 (plurality). Thus, the

12

Court has twice emphasized the phrase “subject or cause to

be subjected” and, understandably, this has led lower

courts to focus on this phrase as the source of the “policy or

custom” requirement. See, e.g., Williams v. Butler, No.

83-2534, No. 83-2641,1988 WL 135650 (8th Cir., filed Dec. 21,

1988) (en banc).’ Yet the Court has never said that this

language alone comprises the “crucial terms" giving rise to

the policy or custom requirement and, upon examination, it

appears that the phrase “color of law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage” also plays a role.

Apparently the Court reads section 1983 quite literally.

The “person” is the local government; the phrase “under

color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

usage” means pursuant to “policy or custom”; and the

phrase “subject or cause to be subjected” requires a causal

relationship between this “policy or custom” on the one

hand and the constitutional deprivation on the other. Cf. Ci

ty of Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808, 818, 105 S.Ct.

2427, 2433 (1985) (“This language tracks the language of the

statute.”), and Pembaur v. City of Cincinnati, 106 S.Ct.

1292, 1299, n. 10, 89 L.Ed. 2d 452 (1986).

Thus the phrase “under color of any law, statute, or

dinance, regulation, custom or usage” is, if anything, more

“crucial” to the “policy or custom” requirement than the

“subject or cause to be subjected” language. Unfortunately,

this “color of law” language has been given other meanings

' On remand from. City of Little Rock v. Williams, 108 S. Ct. 1102 (1988),

vacating, Williams v. Butler, 802 F.2d 296 (8th Cir. 1986) (en banc), on

remand from. City of Little Rock v. Williams, 475 UJS. 1105, 106 S.Ct.

1508, 89 L.Ed.2d 909 (1986), vacating, Williams v. Butler, 762 F.2d 73

(8th Cir. 1985) (en banc), affg, 746 F.2d 431 (8th Cir. 1984).

13

in other contexts.4 This may be why the Court coined the

phrase “policy or custom”, as opposed to quoting the actual

language of the statute.* This perhaps may also be why,

when discussing the actual language of the statute, the

Court has emphasized the phrase “subject or cause to be

subjected.”

B. Section 1983 did not amend Section 1981

1. Section 1981 was not passed by the 42nd

Congress, but by an earlier Congress.

In Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160,168,96 S.Ct. 2586,49

L.Ed.2d 415 (1976), the Court held that Section 1981

originated as § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of April 9,1866, c.

31, 14 Stat 27. The Runyon dissent, however, argued that

Section 1981 originated with § 16 of the Enforcement Act of

May 31,1870, c. 114,16 Stat 144. 427 U.S., at 195 (White, J.,

dissenting). While the court is presently reconsidering

Runyon,* the final resolution of that controversy can make

no difference here. Regardless of whether Section 1981

* In Section 1983 cases the phrase “color of any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage” “has consistently been treated as the

same thing as state action required by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

United States v. Price, 393 U.S. 787, 794 n. 7,86 S.Ct. 1152,16 L.Ed^d

267 (1960). See also, N.C.A.A. v. Tarkanian, 109 S.Ct. 454, n.4 (1988), and

cases there cited. Cf. Adickes v. S. H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144,166-167,

90 S.Ct. 1598, 2 L.Ed. 142 (1970). Compare these cases with Monroe,

where it was argued that the Chicago policemen could not have acted

under “color of law" since their actions in invading and ransacking the

home were contrary to local law. 365 U.S., at 172. The Court rejected

this argument, holding that “[misuse of power, possessed by virtue of

state law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with

the authority of state law, is action taken ‘under color of state law.’ ”

365 U.S., at 184, quoting United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 326, 61

S.Ct. 1031, 85 LJSd. 1368 (1941). Thus, because the Chicago policemen

misused the power given them by state law, they acted “under color of

law." Yet, under Monell these same policemen, almost certainly, would

not have been acting pursuant to their employer’s “policy or custom.”

Cf. Praprotnik, 108 S.Ct., at 946 n. 19 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

* Cf. Pembaur, 106 S.Ct., at 1302 n.l (Stevens, J., concurring).

* See Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 108 S.Ct. 1419 (1988), per

curiam.

14

originated with the 39th Congress in 1866, or with the 41st

Congress in 1870, the fact remains that, when the 42nd Con

gress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871, Section 1981

was already, to use the words of Monroe, “on the books."

2. Absent clear historical evidence, one

cannot conclude that, by passing Section

1983, Congress imposed a “policy or

custom” requirement on Section 1981.

In our case, the Court of Appeals reasoned that “in 1871

when Congress enacted what is now codified as section

1983, which was five years after it had enacted the statute

that became section 1981, Congress did not intend

municipalities to be held liable for constitutional torts com

mitted by its employees in the absence of official municipal

policy.” 798 F.2d, at 762, Pet. App. 29A. Apparently the

Fifth Circuit concluded that, when Congress passed the Ku

Klux Klan Act in 1871, it intended to modify Section 1981 by

imposing a “policy or custom” requirement on the already

existing statute. Since Section 1981 was already “on the

books” this argument raises all the difficult problems of

repeal by implication.” Generally “repeals by implication

are not favored, 7 and the Court has uniformly rejected

them in other cases involving Reconstruction era civil

rights statutes.

In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer, Co., 392 U.S. 409, 88 S.Ct.

2186, 20 L.Ed.2d 1189 (1968), the Court considered whether

42 U.S.C. § 1982, which prohibits discrimination in the sale

of housing, applies to private parties. Section 1982

originated with § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, c. 31,14

Stat 27, and it was re-enacted four years later by § 18 of the

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114, 16 Stat 141. 392

U.S., at 423. In the interval between the two statutes, the

States ratified the 14th Amendment which is, of course,

limited to “state action.” It was argued in Jones that, by re

enacting the 1866 Act as part of the 1870 Act, Congress

’ Posadas v. National City Bank, 296 U.S. 497, 503, 56 S.Ct. 349, 80 L.Ed.

351 (1936); United States v. Henderson, 78 U.S. 652, 565-658, 11 Wall

652, 20 L.Ed.2d 235 (1870); and annotation at 4 L.R.A. 308.

15

meant to incorporate a “state action” requirement into the

statute . 392 U.S., at 436. The Court rejected this argument.

Citing the absence of historical support, the Court refused

to conclude “that Congress made a silent decision in 1870 to

exempt private discrimination from the operation of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866.” 392 U.S., at 437.

In United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383,386-387,35 S.Ct.

904, 59 L.Ed. 1355 (1915), two Oklahoma election judges

were charged with conspiring not to count votes in a Con

gressional election. The charge was brought under § 6 of the

Act of May 31,1870, which made it a crime for two or more

persons to conspire “to injure, oppress, threaten, or in

timidate any citizen with intent to prevent or hinder his

free exercise and enjoyment of any right or privilege

granted or secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the

United States.”'

Here, unlike Jones, there was abundant historical

evidence that Congress had intended to repeal § 6 of the

1870 Act, at least insofar as it applied to voting. In 1894 Con

gress had passed “An Act to repeal all statutes relating to

supervisors of elections.. . ” 28 Stat. at L. 36, ch. 25, Comp.

Stat 1913, § 1015. At one stroke it systematically repealed

every federal statute which expressly dealt with voting.

The list of repealed statutes included § 4 of the 1870 Act,

which made it a crime to use “force, bribery, threats, in

timidation, or other unlawful means [to] hinder, delay, pre

vent, or obstruct... any citizen” from voting or qualifying to

' 16 Stat 141, § 6, later R. S. § 5508. By the time of Mosley this section

had become § 19 of the Criminal Code of March 4,1909, c. 321, 35 Stat.

at L. 1092. It’s now 18 U.S.C. § 241. See, generally, United States v.

Williams, 341 U.S. 70. 83, 71 S.Ct. 581, 95 L.Ed. 758 (1951).

16

vote.' See Mosley, 238 U.S. at 389 (Lamar, J., dissenting);

United States v. Gradwell, 243 U.S. 476, 483-484, 37 S.Ct.

407, 61 L.Ed. 857 (1917); and United States v. Classic, 313

U.S. 299, 334-335, 61 S.Ct. 1031, 85 L.Ed. 1368 (1940).

Moreover, the 1894 Congressional debates reflected a clear

intent to exclude all aspects of voting from the protection of

the civil rights laws. 238 U.S., at 390-391. Despite this

manifestation of legislative intent, the Mosley Court con

cluded that § 6 had not been repealed or narrowed by the

1894 statute. It thus permitted the election judges to be pro

secuted.

As a final example, we turn to Lynch v. Household

Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538, 92 S.Ct. 1113, 31 L.Ed^d 424

(1972), where the Court considered the history of 28 U.S.C. §

1343(3), the “jurisdictional counterpart” of § 1983. 405 U.S.,

at 543. That statute gives federal courts jurisdiction over

“any civil action” to redress a deprivation of civil rights, and

it contains no amount-in-controversy requirement. See,

generally, Lynch, 405 U.S., at 543 n. 7, and Chapman v.

Houston Welfare Rights Organization, 441 U.S. 600, 607, 99

S.Ct. 1905, 60 L.Ed.2d 508 (1979). In 1875 Congress passed

the forerunner of 28 U.S.C. § 1331 which, for the first time,

gave federal courts general jurisdiction over all civil suits

“arising under the Constitution and laws of the United

States.” 405 U.S. at 546. That statute originally imposed a

minimum jurisdictional limit of $500, which was periodically

increased until it had reached $10,000 at the time of Lynch.

405 U.S., at 546 n. 12.'°

Early cases construed these statutes by distinguishing

between “personal rights” and “property rights”. Suits to

redress deprivations of “personal rights” were covered by

the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act . Actions involving “property

rights", on the other hand, were deemed to arise under the

* In the Revised Statutes, §§ 4 and 6 of the 1870 Act were placed in Title

70, Chapter Seven, entitled “Crimes Against the Elective Franchise

and Civil Rights of Citizens.” Thus, § 4 of the 1870 statute became R.S.

§ 5506, while § 6 became R.S. § 5508. See Revisor’s Notes to ch. 7 of

Revised Statutes.

" The amount in controversy requirement was deleted in 1980. Pub. L.

96-486, § 2 (a), 94 Stat 2349.

17

1875 federal question statute, and thus had to meet its

amount-in-controvesy requirement. 405 U.S., at 546-547.

The Lynch Court overruled these cases. The two statutes

were independent, and the 1871 statute covered suits to

redress deprivations of “any rights, privileges, or im

munities secured by the Constitution,” including “property

rights.” To hold otherwise, one would have to reason that,

when it enacted the 1875 statute, Congress “intended to

narrow the scope of a provision passed four years earlier as

part of major civil rights legislation.” 405 U.S., at 548. The

Court, citing the prohibition against repeals by implication,

“refus[ed] to pare down § 1343(3) jurisdiction.” 405 U.S., at

549.

Finally, the Court has generally refused to conclude that

modern civil rights statutes have narrowed the scope of the

Reconstruction era statutes. See, Great American Federal

Savings & Loan Assn v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366, 377, 99

S.Ct. 2345, 2351, 60 L.Ed.2d 957 (1979), and Id., 442 U.S., at

391 (White, J., dissenting). See also, Sanders v. Dobbs

Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097,1100 (5th Cir. 1971), and Waters

v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvestor Com

pany, 427 F.2d 476, 484 (7th Cir. 1970), cert denied, 400 U.S.

911 (1970).

These principles apply to our case. We cannot assume

that the 42nd Congress made a silent decision to impose a

“policy or custom” requirement onto Section 1981 when it

enacted Section 1983. To conclude that Section 1983

somehow amended Section 1981, we must have clear

historical evidence. The historical evidence that does exist,

however, points in the opposite direction.

3. Congress did not intend for Section 1983

to amend Section 1981.

The Fifth Circuit concluded in our case that “Congress

did not intend to impose different types of liability on a

municipality based on the particular ‘federal’ wrong

asserted.” Pet. App. 29A. However, even if that were so it

would not justify a repeal by implication which, as we have

seen, requires strong evidence of an affirmative intent to

repeal. Even so, the Fifth Circuit’s reading of Congressional

intent is probably wrong. There’s evidence that the rights

18

secured by the 1866 Act were viewed quite differently from

the rights secured by the 1871 Act and that the two statutes

were passed to meet different needs. And while the views

involved may not have survived as viable legal theories,

they do reveal the intent of those that held them. Cf.

Monell, 436 U.S., at 676.

As the 1866 debates make clear, the Civil Rights Act of

1866 was intended to secure certain specific rights to the

newly freed slaves. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 41

(remarks of Rep. Sherman), 474-475 (Sen. Trumbull), 504

(Sen. Howard). These rights were regarded as “fundamen

tal” or “inalienable” or “natural”. Id., 474-475 (Sen. Trum

bull), 1118-1119 (Rep. Wilson). The idea had been discussed

by Justice Washington, on circuit, in Corfield v. Coryell, 4

Wash. C.C. 371, 6 Fed. Cas. 546, 551-552 (1823), and Senator

Trumbull read from that opinion on the Senate floor. Cong.

Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 475. See, generally, United

States v. Morris, 125 F. 322, 325-326 (E.D. Ark. 1903), and

cases there cited. See also, Jones, 392 U.S., at 441, 465, 466.

Section 1 of the statute, as originally introduced, read as

follows:

There shall be no discrimination in civil rights or

immunities among the inhabitants of any State or

Territory of the United States on account of race,

color or previous condition of slavery; but the in

habitants of every race and color, without regard

to any previous condition of slavery or involun

tary servitude, except as punishment for crime . . .

shall have the same right to make and enforce con

tracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to in

herit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real

and personal property, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security

of persons and property, and shall be subject to

like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or

custom to the contrary notwithstanding.

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st sess., 211 (emphasis added).

During the ensuing debate questions were raised concern

ing the scope of the phrase “civil rights and immunities.”

The Act’s proponents insisted that this language referred

19

to "fundamental rights.” Opponents, however, feared it

might also encompass “political rights”, including the right

to vote.

Thus, after Sen. Trumbull had equated “civil rights and

immunities” with “fundamental rights”, Id., 474-475, the

following exchange took place:

MR. McDOUGALL:. . . Do I understand that it is

not designed to involve the question of political

rights?

MR. TRUMBULL: This bill has nothing to do with

the political rights or status of parties. It is confin

ed exclusively to their civil rights such as apper

tain to every free man.

Id., 476. Opponents were not convinced by Senator Trum

bull’s assurances, however. Senator Saulsbury drew the

distinction between “rights which we derive from nature”

and “rights which we derive from government.” Id., 477. He

went on to note that “[t]he right to vote is not a natural

right.” Id., 478. He then read the “civil rights and im

munities” language and remarked that “the question is not

what [Sen. Trumbull] means but what the courts will say the

law means.” Id., 478. See also, Id., 1117, 1151.

Eventually there was a compromise. On the eve of final

passage, the bill was amended to delete the reference to

“civil rights or immunities”. Id., 1367-1368. See also,

General Bldg. Contractors A ss’n v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S.

375, 388 n. 15, 102 S.Ct. 3141, 3149, 73 L.Ed.2d 835 (1982).

This left § 1 as protecting a specific list of enumerated

rights, which Congress viewed as “natural rights.”

Five years later, when Congress drafted § 1 of the Ku

Klux Klan Act, it modeled it after § 2 of the 1866 Act,11

which read as follows:

That any person who, under color of any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, shall

subject or cause to be subjected, any inhabitant of

any State or Territory to the deprivation of any

right secured by this ac t . . . shall be deemed guil

ty of a misdemeanor . . .

" See Lynch, 405 U.S., at 545.

20

c. 114,14 Stat 27, § 2 (emphasis added). The “rights secured

by this act” were obviously the "natural rights”

enumerated in § 1. The 1871 Congress, however, deleted

that language and substituted the phrase “any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution.”

While there was controversy as to what these words

meant, their meaning was ultimately decided, to quote

Senator Saulsbury, by “what the Courts will say.” In the

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36, 75-80, 16 Wall 1136, 21

L.Ed. 394 (1872), the Court construed the Fourteenth

Amendment’s “privileges and immunities” clause to include

only those rights which arose or grew out of the citizen’s

relationship with the national government. The Court ex

pressly rejected the argument that “privileges and im

munities” includes “natural rights,” 83 U.S. at 75-76, and

this same construction was later given the “rights,

privileges, and immunities” language of § 1983. See Hague

v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496,511,59 S.Ct. 954,83 L.Ed. 1423 (1939),

and 307 U.S., at 520 (Stone, J., concurring).

Thus, we can conclude that Congress did not intend, by

enacting § 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act, to secure the same

rights secured by the 1866 Act. See, generally, District of

Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418, 93 S.Ct. 602, 34 L.Ed.2d

613 (1973), and cases cited at our Petition, p.15.

C. The history and language of Section 1981

show that Congress did not intend to include

a “policy or custom” requirement in that

statute.

To construe Section 1981, we must look to the history and

language of that statute, not Section 1983. Unfortunately,

the legislative debates are not helpful. Thus, we turn to the

other guidepost in this difficult area, statutory language.

We know that the Monell Court relied exclusively on the

language of Section 1983 to derive the “policy or custom” re

quirement. See Part IA2 above. We also know that Section

1983 was modeled after § 2 of the 1866 Act. See part IB3.

This hints that § 2 of the 1866 Act might itself contain a

“policy or custom” requirement. This possibility deserves

examiniation, since Section 1981 originated in the preceding

section (§ 1) of that same 1866 Act.

21

Again, we examine the specific language of § 2 of the 1866

Act:

That any person who, under color of any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, shall

subject or cause to be subjected, any inhabitant of

any State or Territory to the deprivation of any

right secured by this a c t. . . shall be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor.

c. 114, 14 Stat 27, § 2 (emphasis added). Obviously, the em

phasized language comprises the “crucial terms” from

which the Monell Court inferred the “policy or custom” re

quirement. See Part IA2 above. Yet, there is a vast dif

ference between § 2 of the 1866 Act and the modern Section

1983. The former was a criminal statute, the direct ancestor

of the modern 18 U.S.C. § 242.12 Since the notion of criminal

liability of a city was unknown at the time, it seems unlikely

that the 39th Congress had any kind of “policy or custom”

requirement in mind when it enacted § 2 of the 1866 Act.

If the Court agrees, then this part of the argument need

not continue. Since the “policy or custom” requirement

arises from the “crucial terms” of § 1983, and since Con

gress could not have meant “policy or custom” at the only

place where it used those “crucial terms” in the 1866 Act,

then Congress could not have intended to impose a “policy

or custom” requirement anywhere in that statute.

If, on the other hand, we assume that, by including the

“crucial terms” in § 2 of the 1866 Act, Congress did intend

to impose a “policy or custom" requirement on that section,

it does not follow that such a requirement should be read in

to § 1 as well. Indeed, it’s more plausible to conclude that

Congress did not intend to impose such a requirement on §

1, or on any other part of the 1866 Act, except for § 2.

The restrictive language of § 2 stands in sharp contrast to

the rest of the 1866 Act. Neither the phrase “color of any

law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom”, nor the

words “subject or cause to be subjected”, are found in any 11

11 See Screws t>. United States, 325 U.S. 91. 98, 65 S.Ct. 1031, 89 L.Ed.

1495,162 A.L.R. 1330 (1945); United States v. Williams, 341 U.S., at 83;

and Classic, 313 U.S., at 327 n. 10.

22

of the other sections. And while the Court has not dealt with

the absence of the phrase “subject or cause to be

subjected,” it has on several occasions drawn meaning from

the fact that the “color of law” language appears only in § 2.

It is to these cases that we now turn.1*

Again our simplest example is found in Jones, 392 U.S.

409, which construed Section 1982, a statute that also arose

from § 1 of the 1866 Act. In deciding that § 1 of the 1866 Act

reaches private conduct, the Court reasoned that, if § 1 had

been intended to reach only governmental conduct, “then

much of § 2 would have made no sense at all.” 392 U.S., at

424. The Court illustrated its point by quoting § 2 verbatim

and emphasizing the “color of law” language. 392 U.S., at

424 n. 32. Since the “color of law” language was present in §

2, but not in § 1, Congress must have intended for § 1 to

reach more than conduct committed under “color of law”,

i.e., private conduct.

Congress also omitted the “color of law" and "subject or

cause to be subjected” language from § 6 of the 1866 Act,

which imposed criminal penalties on “any person who shall

knowingly and willfully obstruct, hinder, or prevent” the ar

rest of a person charged with violating the statute, c. 31,14

Stat 28, § 6.

While we find no case construing § 6, both it and § 2 were

carried forward to the 1870 Act.'* There § 17 (re-enacting §

2 of the 1866 Act) contains the “color of law” and “subject or

cause to be subjected” language, while § 11 (re-enacting § 6

of the 1866 Act) still applies to "any person.” c. 114,16 Stat

142, § 11,144 § 17. Moreover, the 1870 Act contains several

new sections which, like § 11, also impose criminal penalties

on “any person” or “persons.” These are §§ 4, 5, and 6, c.

114, 16 Stat. 141, which became §§ 5506, 5507, and 5508 of

the Revised Statutes.

11 Bearing in mind, of course, the ambiguous nature of the “color of law”

language. See footnote 4 above.

14 This part of the argument is particularly important if the view of the

Runyon dissent should prevail. Under that view § 1981 arose from § 16

of the 1870 Act, and not § 1 of the 1866 Act. See Runyon, 427 U.S., at

195-211 (White, J., dissenting).

23

Section 6 of the 1870 Act (R.S. § 5508) made it a crime if

“two or more persons shall band or conspire together, or go

in disguise upon the public highway, or upon the premises of

another, with intent to violate any provision of this act, or to

injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any citizen with in

tent to prevent or hinder his free exercise and enjoyment of

any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the Con

stitution or laws of the United States.” This is the original

version of the modern 18 U.S.C. § 241, United States v.

Williams, 341 U.S. 70, at 83, 71 S.Ct. 581, 95 L.Ed. 758

(1950), and it has long been settled that § 241 reaches

private conduct. 341 U.S., at 75-76 (plurality), Id., at 93

(Douglas, J., concurring).

Again this conclusion depends on the absence of the “col

or of law" language from § 6. Since conspiracies under color

of law are reached by § 17 of the 1870 statute (§ 2 of the 1866

Act), it follows that “the principal purpose of § 6, unlike § 17,

was to reach private action rather than officers of a State.”

341 U.S. at 75-76 (plurality). See, generally, Griffin v.

Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88,104,91 S.Ct. 1790,29 L.Ed.2d 388

(1971), and cases there cited.

_ Finally, we note §§ 4 and 5 of the 1870 Act (R.S. §§ 5506 &

5507), which also apply to “any person.” These sections

were passed to enforce the 15th Amendment, which pro

vides that “[t]he right of Citizens of the United States to

vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or

by any state on account of race, color or previous condition

of servitude.” (emphasis added)

In James v. Bowman, 190 U.S. 127, 23 S.Ct. 678, 47 L.Ed.

979 (1903), the Court considered an indictment brought

under § 5 of the 1870 statute (R.S. § 5507), which made it an

offense for “any person” to “prevent, hinder, control, or in

timidate, any person from exercising . . . the right of suf-

ferage, to whom the right of sufferage is secured or

guaranteed by the [15th Amendment].” c. 114, 16 Stat 141,

§5.

The Court read the 15th Amendment as giving Con

gress only the authority to legislate with regard to actions

taken “by the United States or by any state,” a requirement

analogous to the “state action” requirement of the

24

14th Amendment, 190 U.S., at 136-137. Since § 5 of the 1870

Act (R.S. § 5507) did not confine itself to “state action” it

was overbroad. Moreover, the Court refused to preserve its

constitutionality by reading in a “state action” requirement.

There were “no words of limitation, or reference, even, that

can be construed as manifesting any intention to confine its

provisions to the terms of the 15th Amendment.” 190 U.S.,

at 140, quoting United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214, 2 Otto

214, 23 L.Ed. 563 (1875). Obviously, the missing “words of

limitation” were to be found in the “color of law” language,

then located in § 17 of the 1870 Act (§ 2 of the 1866 Act). The

Court said it “must take these sections of the statute as

they are,” 190 U.S., at 141, and it refused to “disregard . . .

words that are in the section” and to “in se rt. . . words that

are not in the section.” “The language is plain,” the Court

wrote. “There is no room for construction.” Id. See also,

United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214, which struck down § 4

of the 1870 Act (R.S. § 5506) on similar grounds.

We have seen in Part IA2 that the “policy or custom” re

quirement stems from certain "crucial terms." These cases

here show that, if Congress really meant to impose a “policy

or custom” requirement by including these “crucial terms”

in § 2 of the 1866 Act, then its decision not to include them in

§ 1, or any other part of the 1866 Act, means that Congress

intended that § 1 —hence Section 1981—would not contain a

“policy or custom” requirement.

We also note that the literal reading given the sections in

volved in these cases is consistent with the maxim that a

Reconstruction era civil rights statute must be given “a

sweep as broad as its language”, Jones, 392 U.S., at 437,

quoting, United States v. Price, 393 U.S. 787, at 801, 86 S.Ct.

1152,16 L.Ed.2d 267 (1960). To read the "crucial terms” into

§ 1 of the 1866 Act, when they simply do not appear there,

25

would fly in the face of this established approach to the

Reconstruction era statutes. Ultimately, to read a “policy or

custom” requirement into Section 1981 would be “to seek in

genious analytical instruments” to carve an exception from

Section 1981 that simply was never intended. Jones, 392

U.S., at 437, quoting Price, 383 U.S., at 801.

II. The familiar rule of respondeat superior offers the

most suitable standard for § 1981 liability.

In Part I we demonstrated that Congress did not intend

to impose a Monell style “policy or custom” requirement on

Section 1981. Now we inquire as to what Congress did in

tend.

A. Considerations of legislative intent re

quire imposition of a respondeat

superior standard.

Legislative intent can be drawn from Congress’ silence.

This was the approach taken in the Section 1983 cases in

volving immunities. There, although the statute was silent

on the immunity issue, the Court inferred legislative intent

from the fact that, in the year 1871, questions of legislative

and judicial immunity were viewed as “settled principles.”

Pierson v. Pay, 386 U.S. 547, 554, 87 S.Ct. 1213,18 L.Ed.2d

288 (1967) (judicial immunity). The Court refused to believe

that Congress "would impinge on a tradition so well ground

ed in history and reason” without mentioning it in the

language of the statute. Penny v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367,

376, 71 S.Ct. 783, 95 L.Ed. 1019 (1951) (legislative

immunity).1* On the other hand, the Court found “no tradi

tion” of qualified good faith immunity for municipal corpora

tions and thus refused to impose it. Owen v. City of In

dependence, 445 U.S. 622, 638, 100 S.Ct. 1398, 63 L.Ed.2d

673 (^so).1*

“ See alto, Scheurer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 243-245, 94 S.Ct. 1683, 40

L.Ed. 90 (1974); Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 316-319,95 S.Ct. 992,

43 L.Ed.2d 214 (1975); and Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409,417-424,96

S.Ct. 984, 47 L.Ed.2d 128 (1976).

" cf- CitV of Newport v. Fact Concerts,Inc., 453 U.S. 247,101 S.Ct. 2748,

69 L.Ed. 616 (1981) (city immune from punitive damages).

26

This approach allows Section 1981 to be read in light of

the “settled principles” of 1866 (or 1870 if the Runyon dis

sent is correct). As it turns out, the prevailing notion of

municipal liability in the middle of the 19th Century was the

familiar rule of respondeat superior. This was

demonstrated by the Tuttle dissent, 471 U.S., at 834-839

(Stevens, J., dissenting)17, and this area has been ably ex

plored in Part I B of the amicus curiae brief of the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund in our case. Of course, Tuttle was a Sec

tion 1983 case, and the dissent there could not overcome the

language of the statute. Here matters are different.

B. 42 U.S.C. § 1988 also compels adoption

of a respondeat superior standard

A second avenue of. inquiry acknowledges the fact that

private causes of action under Sections 1981 and 1982 do not

arise from the express language of those statutes. Rather in

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229, 90 S.Ct. 400,

24 L.Ed.2d 386 (1969), the Court held that in “[t]he existence

of a statutory right implies the existence of all necessary

and appropriate remedies.” Id., at 239.1' The Sullivan Court

went on to say that in fashioning a private remedy under

Sections 1981 and 1982, “both federal and state rules on

damages may be utilized, whichever better serves the

policies expressed in the federal statutes.” 396 U.S., at 240.

In support of its approach, the Court cited 42 U.S.C. § 1988,

which directs the district courts to exercise their jurisdic-

" We incorrectly cited Praprotnik, 108 U.S. 937 (Stevens, J., dissenting),

for this proposition in our Petition, p. 26.

“ See also, Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S., at 414 & n.13, and

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454, 459-460, 95 S.Ct.

1716, 44 L.Ed.2d 295 (1975) (§ 1981). See, generally. Cannon v. Universi

ty of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677,99 S.Ct. 1946,60 L.Ed.2d 560 (1979). One can

also argue that Section 1981 and 1982 claims are expressly allowed by §

3 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, which provides that “the district courts

of the United States shall have . . . cognizance . . . of all causes, civil and

criminal, affecting persons who are denied. . . any of the rights secured

to them by the first section of this act.” c. 31,14 Stat 27. See Cannon,

441 U.S., at 736 n. 7 (Powell, J., dissenting). For purposes of our argu

ment, however, that approach leads to the same place as the argument

based upon the implied cause of action, i.e., to 42 U.S.C. § 1988, the

modern version of § 3 of the 1866 Act.

27

*

tion to enforce the civil rights law s.. .

. . . in conformity with the laws of the United

States, so far as such laws are suitable to carry the

same into effect; but in all cases where they are

not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the

provisions necessary to furnish suitable remedies

and punish offenses against the law, the common

law, as modified and changed by the constitution

and statutes of the State wherein the court having

jurisdiction of such civil and criminal cause is held,

so far as the same is not inconsistent with the Con

stitution and laws of the United States, shall be

extended to and govern the said courts in the trial

and disposition of the cause . . .

After Sullivan, the Court applied Section 1988 to hold

that questions of limitations under Section 1981 are to be

governed by “appropriate” state law. Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454,462,95 S.Ct. 1716,44 L.Ed.2d

295 (1975). The Court cautioned, however, that “considera

tions of state law may be displaced where their application

would be inconsistent with the federal policy underlying the

cause of action under consideration.” 421 U.S., at 465.

This was also the approach in Moor v. County of

Alameda, 411 U.S. 693, 93 S.Ct. 1785, 36 L.Ed.2d 596 (1973),

where the Court refused to allow a county to be held liable

under Section 1983 for the constitutional torts of its sheriff.

While state law expressly allowed counties to be held liable

for the civil rights violations, this feature could not be incor

porated into Section 1983, since the result would be “less

than consistent” with Monroe v. Pape. 411 U.S., at 706. The

Moor Court reasoned that, because of the Monroe decision,

its case was “a wholly different case from those in which,

lacking any clear expression of congressional will, we have

been called upon to decide whether it is appropriate to look

to state law or to fashion a single federal rule in order to fill

the interstices of federal law.” Id., 411 U.S., at 701 n. 12.

Of course, in our case there is no “clear expression of Con

gressional will”. As we showed in Part I, Monell’s “policy or

custom” requirement is inapposite to Section 1981. Thus,

the Court is perfectly free to look to state law or to fashion

28

“a single federal rule.”1*

Texas law leads us unhesitatingly to a rule of respondeat

superior.10 Similarly, in adopting a single federal standard