Hairston v. McLean Trucking Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 16, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hairston v. McLean Trucking Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1974. f3466115-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/67de046a-7553-4893-93cd-760e76a95071/hairston-v-mclean-trucking-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

c

LV . . . . ssidTOU-taa TEfiai aiqaoxTcTdy Aa pojxoddns

qoN oxy puy pxoooH sxqj, VO potqxqcup 3°H

oxv Aod XOG9 oj, popqxq^S oxon sjjxquxspa

. pouieM oq.L 30 °*‘M ^Tu 0 qeqj, &uxpi‘V[ouop uj

qxtioo qoxxqsxa 3^1 AH pouSxssy s u o s g o h 3ltl I

i NHNflOH V

................ gV2l-I 3G q-UDuiAopdaia , sj3xquxGpd ‘01

............................ a inn x o j su g xj, o n ' 6

............... ...............o [ na oxx ipn on ‘ 8

Y£ . . . . . . (suoxsxAOXd qoexquoo) = :j0 qpnsoH

V sy S'ZI‘1 puy ueaaoN 3V sqop ueoMqog

quaiuoAOW ooAopduia uo suoxqoxxqsaH ‘ £

.........uoogoK puy SVW 9V spxspucqs Bu x x t h ‘9

. .................. oanpaoojd Bu x x t h qpf *9

.......................... sVrl qy Guxqsod qor ‘ V

g-j- • • •ooxqoexd Buxxxq Ax oq o u x urr x o o x a Ax i c x o g h

poqqxiupy sqi puy SAN JV ooxoj X^°M *£

£ ............... * .............sxoAxxa pa oh S',/

sqoGia oxxi-I. oj, Buxsnjan JO ooxqoexd

paq.q.TUipv sqi PUV uusqoN qy ooxoa qx^M 2

. .................. .. SqoHd punoxfiqoaa ' I

(3

r . . ............................................. . . . g ^ o s j 9 i {3 j o q u a u io q s q s * I I

0

T7 .................................Mopog sbuxpaaooxd *1

̂ ............. ....................... asvo ana jo iKai-iaavas

....................................... . jo a^awaivis

TT.C ........................ ................... sasvo ao aaav.L

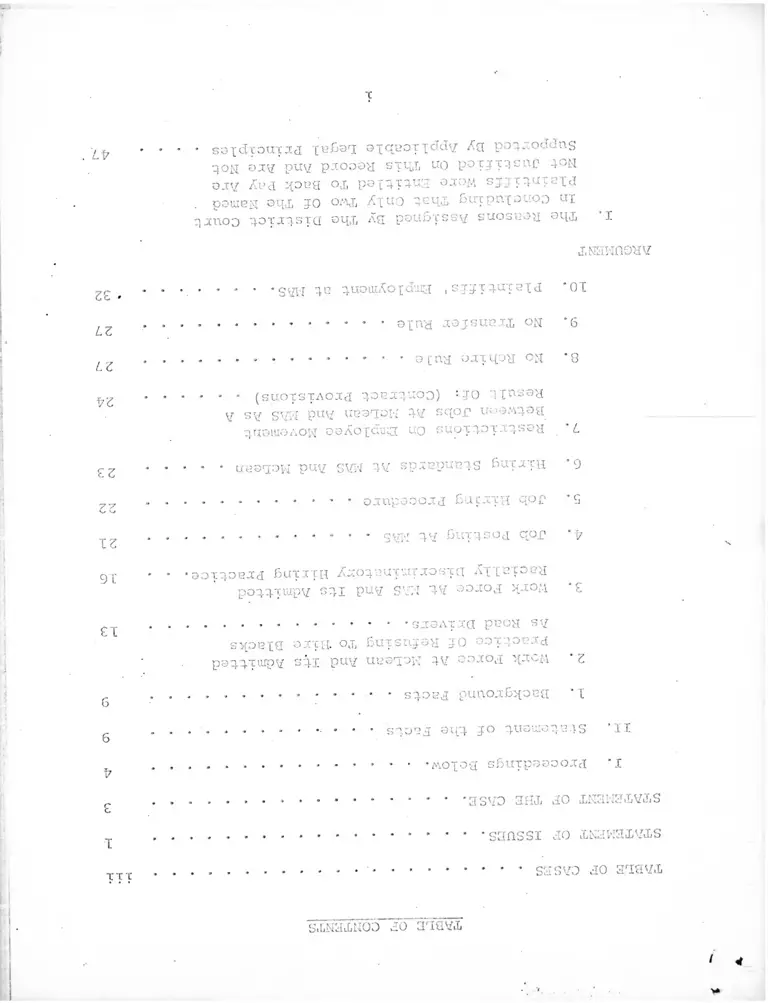

S,LN JiLNOO u O .1 IGViL

>*

I <

II.

III.

IV.

CONCLUS

1. None Of.the Other Plaintiffs Subjectively

And Objectively Sought A Change In

Their Employment ...............................

2. Some Rejected Offered Opportunities...........

3. The Pay Differentials Do Not Vary Greatly

Because Job Progression At MAS Is Set Up

On An Industrial Union Rather Than On A

Craft Union Basis...............................

4. Computation Of Back Pay. . .May Well

Prove To Be An Adventure In Speculation. . . .

The District Court Was Not Justified In

Limiting The Back Pay Award For* Plaintiff

Warren To A Beginning Point In 1968. . . -

The Continuation Of The Job Classiricauion

Seniority Standard Is Not Mandated By

Business Necessity ........................

The District Court Erred In

p c c- f v- t_ q l i n c f P 3 a j n

Jobs At McLean .

iffs To Transfer To Road

. 65

ION 66

ii

f

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896

(7th Cir. 1973).....................................

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711.

(7th Cir. 1969).........- ..........................

Bush v. Lone Star Steel, 373 F.Supp. 526

(E.D. Tex. 1 9 7 4 ) ................. .......... • • • •

Cypress v. Newport News General •& Nonsectarian

Hosp. Ass 'n. , 375 F.2d 648 (4th Cir. 1.96/) . . . .

Diaz v. Pan American Airways, Inc., 346 F.Supp.

1301 (S.D. Fla. 1972). . . ........................

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 017

(5th Cir. 1974)............. ................. * * -

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225

(4th Cir. 1970)............................ .. • • •

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 4 01 U.S. 424 (.19 71) .

Head v. Timkin Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d

870 (6 th' Cir. 1973). ........................... • -

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 435 F.2d

390 (5th Cir. 1974). . ........................ • •

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ...............................

Jones v. Leeway Motor Freight, Inc., 431 F.2d

245 (10th Cir. 1970) . . . . . ................. ■

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 301 F.Supp. 97

(M .D .K .C . 1969), aft'd in pertinent part, 483

F .2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971).......................... .

Local 189, United Papermnkers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969).............

51

51

61

53

61

54,

4 7

51

51

51

53

53

47,

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 2 FEP Cases G58

(N.D. Ga. 1970). . . . . .......................... 65

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134

(4th Cir. 1973)..................................... 50, 51, 52, 58

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F . 2 d 211 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ............ ............. 50, 51, 59, 64

Robey v. Sun Record Co., 242 F.2d 684

(5th Cir. 1957).................................... 59

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 -F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 197.1), cert. den. 404 U.S. 1006 (1971). . . . 47, 51, 61, 64-

Story Parchment Co. v. Patterson Parchment

Paper Co., 282 U.S. 555 (1931) .................... 59

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d

1194 (7th Cir. 1971) .. .......................... 61

United Sheet Metals Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 12 3 (8th Cir. 1969) ...................... .. . 53

United States v. C. & 0. Ry. Co., 471 F.2d 582

(4th Cir. 1972), cert. den. 411 U.S. 939 ......... 63

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Co., 446 F.2d

652 (2nd Cir. 1971).'.............................. ' 65

Young v. Edgcomb Steel Co., No. 73-2347 (4th

Cir. July 11, 1974)................................ 56

Statute

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. Section 2 000e et seg..................... 47

I

iv

k

■

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TIIE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1750

PATRICK T. HAIRSTON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

MCLEAN TRUCKING COMPANY,

INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF

TEAMSTERS, WAREHOUSEMEN AND

HELPERS OF AMERICA, LOCAL 391;

and MODERN AUTOMOTIVE SERVICE,

INC. ,

Appellees

On Anneal From The United States Dj^trict^Cgurt _ < _

For T h e District Of Horth_Carolijia^Winst^

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Whether the district court erred in denying the hack

pay claims of all class members except plaintiffs Hairston and

Warren?

2. Whether the district court erred in limiting the hacK

pay award for plaintiff Warren to 19.68?

-2-

c 1 a s

ment

cl as:

3. Whether the district court

ification seniority provision

of affected class members at M

erred in

to govern

AS?

continuing the

the upward move-

4 . Kl-iether 'the district court erred in limiting affected

3 members mho were employees of HAS to consideration for

-road driving positions at McLean.vacancies in over-the

-3-

STATEMEFT OF TUB CASH

This is an appeal by the plaintiffs below, appellants

herein, from certain portions of the January 23, 1974 Judg

ment .(A. I pp. 90-99— ■‘ ) of the United States District Court for

the Middle District of North Carolina, raising issues concern

ing the relief entered in favor.of the plaintiffs in an action

brought under Title VII of the Civil Rignts Act o .l 196-:-, 42

U.S.C. Section 2000e et sea., after the district court found

that the "defendants have intentionally engaged in and are

engaged in unlawful employment practices" .as described in the

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law entered September 4,

1973 (7̂. 1 pp. 52-39) .

The appellees herein, defendants belov.' are: (1) McLean

Trucking Company, a North Carolina corporation (hereinafter

"McLean"); (2) Modern Automotive Services, Inc., a North

Carolina corporation and a wholly ov/ned subsidiary of McLean

(hereinafter "MAS"); and (3) the International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, Chauffeurs, V.sre.oousomen and HeIperc of America,

Local 391 (hereinafter "Local 391").

— 'Vne printed appendix consists of three separate volumes

designated "I", "II"/ and "III." Citations to the parts of the

record reproduced in the appendix will be "A.I", "A.II", or

"A.Ill" followed by the page of the appendix at which those

parts appear. Appendix page numbers are centered at the top^

of the page. Other numbers are the page numbers of the original

documents.

* s u o t TJ.OIU J O *[BTU0p o q j u o

.r 0 — rn^rTrTn o'-' • frtr t * r •? Tnr"0 />0 'i TOO— / r?Q ‘ 7*>Qb lI[4 u»iuj.ui4 j i l *- ̂ v-*-v-'*.v v o *- ̂ l ̂̂ "* ■'»* ' ~'' v - . — • *

•Q-H -J 29 9 2 poguodox si uoxgoui sxqg GuxAuop xopxo gsug oqg,

* 9 i -ON A x q UO q o q O O p OOS - p O T U O p 9 JCOA SUOigOUI S U O U E A OGOUX

" [ 8 6 1 u o x g o o s ' D ' S ' n Zv ? ° s u o t - g i o t a o 5 op-[i? 0 9 guxexGuioo

xpoqg puouis’og poAOui sggxguxexd s u o t s g o o o -[g.toaos uq / 7

pogxg sggxguxsxd '396T '8 c e u n 8 uo ’ ( L ~9 I'V) 9[9TI>

go uoxgsxoxA ux soE-i xxoigp. go osnsooq sqosgq go saxxxungxoddo

quouiAoxduio oug Buxgxuixx go ooxgosxd oxuiogsAs e ux pofiefiuo

o x o a X6 e [Gooq pus ueoqow goqg poCopTc guxsxduioo xsux8x;to oqj,

* (AI 'Baud ' c i • y) useqow go „Axsxpxsqns poux.o Axioq.'-\ s

' • o u i 'S0OTAJ3S OATgou.iog.nw u x o p o q 5° guom gxeaoQ o x x x oqg ux

qg ■gsqg guxs [duioo

/ -— • vX.'Oi:\OAOP[ • (e I' V)

U.l t2U '69cq ' z ounp

[GUxGxxo oqg,

UOTgoos xopun ons

o qa so '' Agguonbos

s s I S£ g sooq pus

r«u>iO a.sqo ons-xsdos s

>qg uo * T clot Xsooqpagxg u o .x xe m oxopooq.L ggxguxsid 'Asp ov.ies oqg uq

pus usoqoN uxoxoqg squopuodsox ss Buxursu 0033 W A ooxeqo c j-O

buxgxg oqg ux psuxoC- sggxguxs[d oqg go q s Z.96T 'T£ uq

•Mogog; sDUxqoooooxq 'i

• gyX'I go guouigxsdop SutdaGOOJ

oxxg oqg ux poAogdiuo ouixg ouo gs oxom u:oq.n go n s sooAogaiuo

xoiuxog .to sooAogduio qosgq uooguoAOS oxs sggxguxegd oqx

-V-

oqj jo sjoquraui put? 'uoxjob sscjo t? st? axqt?UTGjUTem„ sbm uoxjob

oqj jeqq. pojn.x ueqj Aoxubjs oBptvp • ([26X '5X eunp) xgtjj

jg oouopxAO , sjj-cjuxe[d jo osojo sqj TXjun AjxjxqsuxGjuxetu

ssgjo eqa uo opeui sew uoxsxoop os ■ ££~Z£ I * d :II ’ £Xt?d

'V I ’M QOS -OanpoDOUci XTAT8> jo sopon TGJopaj '(2 )(q) £ 2 oing

xopun uoxjob ssgto t? s b .uoxjob sxuj jqBnouq sjjxjuiajd

"6951 '81 jsn&ny uo poxuop s j o a suoxjouj osoqj,

•ueoqow jo soodojduio jou q j s m sjjxjuxt?xd oqj auqj pus doss qjTM

GjjxjuxG'[d oqu Aq pojxj soBxnqo oqj ux juapuodsoj; b sb Sxa ps"iBU

qou psq sjjxjUTBjd jt?qq purtoxB oqj uo ssxtusxp oj poAOu ubojoi-t

put? sv:W xojjoo.xoq.L * X68 xeocq put? ueaqcq; Aq oj pojuosuoo

uop.xo ue jo Aajuo oj juunuund jusouojop t? so sdd BuxuxoC

juxBiduioo popuouiB puooos B poijj sjjxjuxGld 6951 ' z our.n uq

8951 '08 T T ^ d

uo pojxj xop.xo ub ut Ao[Ut?as oSpnp Aq poxuop ore:-\ suctjoiu

osoqj, ’(08-62 I'd -ZZ~TZ I'd) jucpuojop b sb Sdd uxcC oq

popxBj psq sjjxjuxejd osnt?ooq ' spuno.xB aoqjo Buouib 'u o x j o b

otri ssxutsxp oj poAOiu put? juxBTdutoo aqj ux suoxjt?£oxie o a x j u b j s

-qns oqj poxuop sjuepuojop osoqj jo qjog ’ (08-^8 '88-91 I'd)

juxBiduioo oqj oj s j o m s u i ? popxj ' a j o a x joodso.x T5£ [cocq

put? UGOjOd '8961 '62 xoqojoQ put? 8951 'Ll -xoqojoo uo

' (5I-8I I'd)

sjjxjuxt?xd oqj oj uoxjejuosoxdox xxgj jo Aunp sjx pojt?jOTA

peq X68 xeooq jGqj oBoxxe oj juxt?[du:oo popuouit? js.xxj xxoqj

-6-

class are those Negroes now employed, or who have at any

time in the past been employed, or who may hereafter seek

employment, in the tire department of the maintenance depart

ment of MAS" (A.II 459).

Judge Ward, before whom the case was submitted for

decision redefined the class as:

(a) In regard to discrimination practiced by

McLean in not hiring blacks for over-the-

road truck driving jobs, the class includes

all blacks now employed, or who were employees

on or after July 2, 1965, either at MAS, or

at McLean's terminal in Winston-Salem, provided

such persons were hired prior to October, 1967,

the date McLean began hiring black over-the-

road drivers.

(b) In regard to the discrimination and segre

gation practiced by MAS in confining blacks to

the garageman and janitoria1 classifications,

the class includes all blacks now employed, or

who were employees on or after July 2, 1965, at

MAS, provided such persons were hired prior to

April 1, 1970, the date the collective bargain

ing contract for the maintenance employees and

the memorandum of understanding for the janitors

permitted garagemen and janitors to transfer

into other departments at MAS.

(A. I 00) .

The case was tried before Judge Stanley in June,1971

who died before rendering a decision on the merits. There

after the parties agreed by stipulation to submit the case

before Judge Hiram II. Ward for decision on the record. The

parties were given the opportunity to present oral argument

before Judge Ward on November 30, 1973.

-7-

On September 4, 1974 Judge Ward entered Findings of

3/

Fact and Conclusions of Law (A.I 52-89 ). Judge Ward found

(1) unlawful discrimination by McLean in its admitted practice

of refusing to hire blacks as over-the-road drivers prior to

October, 1967; (2) unlawful discrimination by MAS in its

admitted practice of hiring blacks into only the garageman

and janitorial classifications prior to May, 1969; (3) MAS and

McLean must be treated as a single employer for the purpose

of this case because of their use of a single hiring hell,

and the coordination of employment regulations exemplified by

the no-rehire and no-transfer rules when taken in conjunction

with the discriminatory practices of the two employers; and (4)

that the policies and practices [i.e. seniority provisions] set

forth in the collective bargaining agreements and memoranda

of understanding between MAS and Local 391 acted as a deterrent

to members of the class as ultimately defined and perpetuated the

prior racial hiring and assignment.

The practices found to be unlawful were also round to be

"intentional" within the meaning of Section 706(g) of the Act.

Conclusions of Law No. 0, A.I 87.

On January 23, 1974 Judge Ward entered a judgment in

_4/

favor of the plaintiffs (A. I 90-99' ). The judgment provided,

^Thc Findings of Fact and Conclusions of.Law are

reported at 62 F.R.D. 642, 651-669.

The Judgment is reported at 62 F.R.D. 642, 669-673,

_4/

-8-

inter alia, that affected class members'at MAS could transfer

to helper positions in the formerly all-white departments

based on company seniority but that their promotions within the

new departments would be governed by classification seniority.

Lay-offs would also be governed by company seniority.

Affected class members at MAS were also given the option of

► to McLean with full company seniority but only

to cver-the-road driver jobs.

Back pay was denied to all members of the class as re

defined except two of the plaintiffs on the grounds that (1 )

rone of the other plaintiffs subjectively and objectively

sought a change in their employment; (2 ) some rejected offered

opportunities; (3) pay differentials at MAS do not vary

greatly since job progression is set up on an industrial union

basis rather than on a craft union basis; (4) computation of

the back pay claims might prove to be an adventure in specula

tion; and (5 ) the cost of administration in relation to any

foreseeable return. Findings of Fact Los. 24 and A.i 6 -r

70; Conclusions of Law Ko. 10, A.I 87-89.

Back pay for Warren and Hairston was assessed against

McLean and MAS only, each being required to pay one half of

the amount (A.I 89).

Costs, reasonable attorneys' fees and expenses were

awarded in favor of plaintiffs, one third each as to MAS,

McLean and Local 391 (A.I 97).

Subsequent to the entry of the judgment Local 391, on

February 1, 1974, moved for reconsideration and to reopen the

record. This motion was denied on April 18, 1974. See 62

F.R.D. 642, 674-676.

On May 20, 1974 plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal

from the January 23, 1974 judgment insofar as it (1) denies

back pay to all affected class members except plaintiffs

Hairston and Warren (A.I 98); (2) limits transfer to McLean

for MAS affected class members at MAS to vacancies in over-

the-road positions only (Id. 93); (3) limits the back pay

award for plaintiff Warren to a time beginning in 1968 (Id.

1 0 2 ); and (4) provides for the continuation c; : 1 t 1 C'.l 1.ion

seniority for the upward movement of affected class members at

MAS who transfer to formerly all white departments (A. I 93-94)

II. Statement of the Facts.

1. Background Facts

The plaintiffs are seventeen black employees or former

employees of MAS. At the time the complaint was filed, all

resided in Winston-Salem, Forth Carolina, and worked at the

tire recapping department at MAS. The dates on which plaintiff

commenced their employment encompass time both before and after

the effective date of the Title VII (A.Ill 613). They are or

were members of Local 391.

-10-

15cLoan oocrates as a motor common carrier in the

eastern, southern and midwestern parts of the United States.

It is a North Carolina corporation with its principal place or

business in Winston-Salem. It has three categories of employees

(1 ) general office,— (2) over-the-road drivers, and (3)

terminal employees.

The over-the-road drivers and the terminal employees wotk

under separate contracts. The over-the-road drivers transport

freight between terminals, usually by tractor-trailers. .Lnc,\

perform the long haul work and receive compensation, basically

for the miles they drive (A.Ill 616). They are not assigned

regular routes, nor do they work regular hours. This unit

constitutes a recognized bargaining unit by the National Labor

Relations Board, and it operates under a collective bargaining

contract. The National Master Freight Agreement and the

Carolina Freight Council Over-The-Rcad Supplemental Agreement

cover the drivers at the Winston-Salem terminal (A.1 54).

The terminal employees work under a collective bargaining

agreement which is termed the city cartage contract. McLean

divides its city cartage employees into three major classifi

cations: (1 ) switchers or (2 ) checkers, who handle freight on

the terminal's dock, and (3) city drivers, who haul goods from

— -^The court held that this case does not concern itself

with employees in the general office (A.I 54). However, the

co_ u r t relied on the statistical evidence about the racial

staffing in the general office to further support plaintiffs

claim. See A.I 57-58.

-li

the terminal to the customer. These workers constitute a

separate “bargaining unit recognized as such for collective

bargaining purposes by the National Labor Relations board.

The Winston-Salem employees are covered by the National Master

Freight Agreement and the Carolina Freight Council City

Cartage Supplemental Agreement. They work regular hours and

shifts, and receive compensation on a per hour basis (Jjg3.) .

MAS is a North Carolina corporation with its principal

place of business in Winston-Salem. McLean formed MAS in

1 9 4 7 as a wholly-owned subsidiary in order to have a firm to

service its equipment. MAS business consists mainly of repair,

maintenance, and service of tractor—trailer units end ocher

automotive equipment, along with selling and providing parts

for such equipment; its principal customer is McLean, although

it will provide service and sell parts to other parties (A.I

54-55).

In its operations MAS utilizes the fo1lowing departments,

automotive, unit rebuild, body, paint, trailer, parts, service

lane, tire recapping and janitorial. It classifies its

employees as mechanics, helpers, clerks, garagemen, or janitors

A H janitors work in the janitorial department. All garagemen

work either in the service lane or the tire recapping depart

ment, which is the only classification in those two depart

ments . The garagemen perform work similar to that c.one in a

-12

filling station, e.g., fueling equipment, changing oil and

filters, replacing light bulbs, washing equipment, and

changing tires. In the remainder of the departments the

employees are classified as mechanics, helpers, and clerks.

They do reoair and maintenance work or fill stock orders

(A. I 55-55).

The court found that while MAS

r cVc 3 bu s inesses, they do to som

'll. O CLs. Thus, the off icers and

capacities

order to a

comoanies sometimes serve both companies, albert in different

officers of each company eo work tcg^i-nsr in

p-ca their common purposes, such as formulating

arcs and coordinating maintenance work with

ds. Personnel records are kept by McLean for both

There is a joint recreational program j-or both

■ H s_.

M cLcm n s .. c

comoanies.

com. ran res I a5}

Lo^al 391 is the baroaining representative for trie Wins con-

Salem over-ths-road drivers and terminal workers at McLean and

for the employees at MLS. Local 391 has its offices in

Greensboro, north Carolina. Blacks constitute fifteen to

twenty per cent cf its membership (A.I 55).

Tie maintenance emplovees at MAS were first organised in

1955. Since 1953, the bargaining for maintenance, as well as

-13-

road and terminal employees, has been conducted between multi-

employer and multi-union representatives. The janitors, who

also belong to Local 391, are covered by a memorandum of

understanding entered into between MAS and Local 391 and based

upon the results of the maintenance contract negotiations

(A. I 56) .

2 . Work Force At MrLejjn_And_ Its Admitted Pract.ice_Of

Refvsing To Hire Blacks As Road Drivers

As of November,1970 McLean had 701 terminal employees

classified as road drivers, city drivers, switchers, and

checkers. The racial breakdown as to each classification was

as follows

Road driver

City driver

Checker

Switcher

Tot a_l

4 7 9“

60

.141

21

701

6 /

White

46S

60

107

18

653

Black

O3?

0

34 '

_3

46

(A.I 58; Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 9, pp. 9-13).

The court found that while blacks have worked beside

whites at the Winston-Salem terminal as switchers and checkers,

no black has ever held the job of city driver. See A.Ill 646.

Miles Carter, Field Employment Manager for McLean, testified

“ ^The total also includes two American Indians,

(Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 9, pp. 9-12)

,‘Z.96T qnoqe uoxqonuqsux Aiu qe poacxq 3 io«

sqoejq qsaxj oqq 'suo qsuxq oqq - qxqun

s.xoAxup peou qoexq ajxq qou pxp oa\ qoA

qnq -afipopMOuq Am oq SVM qe auo£[„ [qpuequqa]

:JOMSuq

„ c S W I

qe sqoC uxequoo pue ueoqoq qc sqoC

uxequao uoq sqoeqq Buxuapxsuoo qou qo

aoxqoeud e s b m axoqq qou 1 0 uoqqaqA

' S ® pue uesqoM qqxA\ uoxqexoosse jcnoA

aouxs 'qpuequqa -j h 'Tieoaac noA ocr„ :uoxqsanQ

: s/AOXI oq se poxqxqsaq ' (2£8 III*q) saxox qod Buxarxq Buxqqas joq

Aqxxxqxsuodsou: aqq peq oqA\ pue svr»'I pue ueaqoR qqoq .xoq .xafieuew

suoxqexoq XGxuqsnpui p>ue quapxsouj ooxa ' qp-xequqa •£> nassriH

s.iOAtjp peo.x uoq sqoexq uapxsuoo u o a s jo s i t u oq Buxsnqau

qo ooxqoeud paueqoap e peq ueaqor.-i— h a aqqxq qo oqep aAxqoaqqa

aqq uaqqe sateaA o«q ueqq oiooi— L96T '-Xaqoqoo oq tot.tj

*(6S~3S I ’V) squoqqa

uxaqq uoq uoxqesuadiuoo euqxa ou s a t o o s j Aoqq uaqM spuezeq Bux

-Aixp Buxoeq pue xaqqeaM oqq ux quo Buxoq qo uop.xnq qeuoxqxppe

aqq Buxumsse ux paqsauaqux qou aue uoiu oqq asneoeq Aouboba

.xaAxup Aqxo e no pxq oq sxoqooqo BuxqqaB ux Aqxnoxqqxx)

peq seq ueaqoi-j ‘(.9^9 m * v ) Aed auies oxpx aAxaoou— suaAxup

Aqxo pue ' suaxpqx/AS ' sxoqooqo 'sx qeqq-soaAox'diuo xouxuuxa.i

auxsop Aoqq qx uaAXup qo qoC aqq xio Bux£>pxq uoq suoxqeoxqxperib

aAeq sqoexq aiuos pue 'qoC xoAxup Aqxo e _xoq pxq ueo qoop

aqq uo fiuxquo/A saaAoxduiq • • d ' 9 1 * oq qxqxqxq .sqqxquxepa

•suaAXJcp Aqxo qoepq Aue uaoq j o a au seq auaqq oBpoq:AOuq

sxxi oq qeqq pue 2961 oouxs ueoqon qqxA\ xrooq seq oq qeqq

-15-

Question : “Is it your testimony that until around

1967 you had a practice of not consid

ering blacks for road driver positions?"

Answer: "That is right."

(A. Ill 896).

McLean's intentional practice of refusing to hire blacks

as road drivers was abandoned in 1967 only after a series of

meetings with EEOC and the Post Office Department (Id. 845).

The first black road driver hired and assigned to the Winston-

Salem terminal was around October, 1967. Blacks had applied

for positions as road, drivers prior to 196/; all of them had

been rejected for the ostensible reason that they were not

_7 /qualified.

All of the plaintiffs and other black employees of McLean

and MAS hired before 1967 were denied the opportunity solely

because of their race to be employed as road drivers because

of I-lcLean's overt practice of refusing to hire blacks and

because of the no—rehire and no—transfer policies of McLean

and MAS. See 7m III 845-846.

— Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 9, deposition of Brenegar,

Employment Manager at McLean, pp. 10—11. Not reproduced in

the appendix.

No special skills are required for over-the-road drivers.

In fact, McLean prefers to train its road drivers. It is one

of the few companies having a driver's training school for its

truck drivers. All drivers, regardless of their past

experience, nust attend the school. The only driving experience

necessary is to have driven a vehicle, including a car, during

the four seasons for a period of one year (A.I 63).

-16-

Cnly in 1967 did McLean start making an affirmative

effort to recruit blacks for ovcr-the-raod jobs. It advertised

in naoers circulated predominantly in the black community/

contacted urban leagues, and requested help from its employees

(A . I 59) .

The court found that in 1965 McLean had a reputation in

the black community of Winston-Sdlem of not hiring blacks to

drive trucks, and MAS nad a reputation or giving the good joos

to whites. At the time of the trial in 1971, the reputations

of the two companies had improved (A. I 59 ) .

3 Uor't Force at MAS And Its Admitted Racially

Discrinfnatory Hiring Practice

All of the departments at MAS except service lane, tire

recapping and janitorial have at leasu two or more different

job classifications. The only classification in the tire

recapping and service lane departments is garageman and the

only classification in the janitorial department is janitor.

The racial composition of employees in the various

departments at MAS as of December, 1969 was as follows

8/

0/■The hourly wage rates for the various

as of December, 1969 were as follows:

Mechanic A) Automotive, Unit Rebuild,

Mechanic 3) Body, Paint

job classification

Hourly Rate

$4.03

3.88

Trailer

Trailer

Mechanic .A)

Mechanic B)

Trailer 3.93

3.78

Trailer Helper) Trailer 3.73

-17-

Department Total Vvh i t e Black

Automotive 52 52

Unit Rebuild 15 15 —

Body 7 7

Paint 2 2 —

Trailer 43 43 —

Parts 17 17 —

Service Lane 37 22 15

Tire Recapping 20 3 17

Janitor 6 ■ — 6

(A.III 595; 603-615).

The racial composition of employees by department, job

classification and the hourly rates for each job classification

as of November, 1970 was as follows:

Hourly

White Black Rate

Automotive )

Unit Rebuild ) Mechanic

Body )

Paint )

40 . $4.53

Trailer ) Mechanic 33 4.43

Parts

Journeyman 8 4.33

Helper 1 0 3.88

8/Cent'd . Hourly Rate

Parts Man A )

Parts Man 13 ) Parts $3.83

3.68

Garageman ) Tire Recapping and

) Service Lane

3.64

Janitor 2.72

*G9L I I I ' V o o s * 6 9 6 1 ' Ab n j o i i s paAoxduia s a e w CX6I

' naquiaAoy jo s b paAoxduia uouioBcjcbB ©qxu.n a u 9 jo Y lV ___

' " “ /OX

* ( 8 0 1 I I I ’ V) 0 X61 'A n en n q ay

ux panxq sew quauiqnedap naxxenq ©q9 ux qoepq suo eqj,

/ 6 '

u o u u g d *g oorf qeqq uoxqdsox© oqq. qq.xM

'SX3 AOO ax eaxt? aqq qfinonqq ' 09 naja.x

no A ©uo ©i.[9 09 j b x x mi s si qaxu.n '0X61

'x ns0 0 9 0 0 paqsp 'qsyx Apxnoxuos 9UBpd

fiuxddeoan anx9 e 09. £nxnnajax uib 1 „ :uoavsuv

„ 2 6 9 6 1 ' 9 2 A e h 09

noxnd 'qanpq on a a quauiqnedap deaon

©nxp au_9 ux uauia&B.XBfi so poxjxssBxo

sosAopdiu© aqq 1 0 xiR Alva uosea.x oqq

'Aou^^ no A it 'uxBX'dxa noA pxnojq,, : uox 9 s a nQ

:s a o x x°3 sb

psx: 1 9 3 3 9 gyxx 9 ° quapxsanq ©o x a 'qnBj pneucaq • qoauiqnBdap sxqq.

1 0 1 suos.xad qoBxq Apuo anxq 09 anuxquoo on Aoxxod pans[aop pue

Xccox9uanux us psqdope 'qaarq ano.n qu©;u:}.xad©p fiuxddsoon anxq aqq

u.x saaAoxdiua xie quqq ©5p©x^ouq XInJ qqx*A Sdrl 'G96T ui

•snoqxuBC dub uauiafiGnsfi 1 0 snox9 2a.xqssoxa qoC

pxed qsaMoq aip9 ux paAoxduia an a a 'suo 9 do oxa 'OXbl ' xaqjiOAoq

90 sb sdi'I 9 0 s0©Aoxdui© qoBxq ©qq 9 0 xiE '©Aoqs u.noqs sy

• (GSX-6XX I I I ' V )

Vl'V VI IS (uauiaoBJBD) aueq aoxAnas

Vl’V 81 __VI (uauiaBexEO) BuTddeoay axxj,

/ox

£Z'V$ I 82 sqtranqnBdoci ia[xsi,l pus

/ 6 9uxBti 'Apog ' PX xnqay 9xun

'OAxqouoqny oqq ux snsdxan

09 cy qonxy 39X1X9

Axunon

-81-

-19-

resigned to enter into a disability

situation. You will note, in referring

to the seniority list that you have,

that there is a break in employment

from June 11 - a break in employment

in terms of adding additional people

to the tire recapping plant - from

June 11, 1950, until May 13, 1963. I

cannot attest as to hiring practices or

standards prior to May 30, I960. During

.1963, when the work load at the entire

tire recapping plant dictated a higher

availability of production man-hours, I

met with Hr. J. P. McEachin - that's

spelled M-c-E-a-c-h-i-n - to discuss

whether or not we would continue hiring

all Negro employees in this area."

Question: "That is 1963?"

Answer: "Yes. And it was my specific recommenda-

v tion to Mr. McEachin at that time that

we begin a program of integrating pro

duction employees in this area of

responsibility. Mr McEachin did not

disagree with my position in terms of

the reasons stated during out conversa

tion. He did point out to me, however,

that the approximately ten people - I

believe there's one or two people off

the seniority list that was there at

that time - but the approximately ten

or eleven people that were employed in

the tire recapping plant worked as a

very closely-knit group. As a group,

their production per man-hour was not

equaled by any other group or department

in the maintenance complex."

Question: "When you say maintenance complex, would

that be all of MAS?"

Answer: "MAS, Yes. These men, by association, by

attitude, seemed to exude great pride

in their accomplishnients . They worked

as a team. The absentee rate in that

n

-20-

area was comparatively long among

production employees, by department, at

MAS. The exception to this was a couple

of employees - Joe Ceasar was one; I

forget the other - who had serious

physical ailments. Mr. Ceasar ultimately

had to retire because of his heart condi

tion. These men also, as a group,

participated in company programs of

solicitation to a higher degree than any

other group. The other programs of

solicitation - the only programs of direct

solicitation - on the property, which you

might say are sponsored by the company,

Red Cross Bloodmobile and United Fund.

After consider "- and omitting a portion -

"I considered Mr. KcEachin's suggestions

that, if possible, we maintain a Negro

production force with the thinking that

we might retain the continuous pride in

workmanship, pride in company association,

which had been indicated across the years."

"After reviewing in detail various

reasons offered by Mr. McEachin, I con

curred with his suggestion. This is why

from May 13, 1953, through May 25, 1969,

we continued to hire only Negro employees

in the tire recapping plant."

Question: "Is it your testimony, Mr. Park, that at

least between 1963 and 1969, that you

considered blacks - only considered blacks -

for the position in the tire recap depart

ment as garagemen?"

Answer: "The answer would have to be yes."

(A.Ill 761-764).

Park further testified that although he was not associated

with MAS until 1960, the racial composition of the various

departments were substantially the same in 1955 as they were in

November, 1970 (A.Ill 798-799).

ti

-21-

Frcn July 2, 1965, to December, 1969/ rĴ S hired 2o ncrf

envoi oyees in departments other than tire recapping and

n /janitorial; all of tnem were white. No blacks, including

the plaintiffs, were offered the opportunity to fill vacancies

in these departments.

The oractice of MAS of employing blacks only in the tir<

recapoir.e department continued until May, 1969— almost four

year

7 Pi T P» 'yea

after the effective date of Title VII and more than a

:r this lav;suit was filed. The first white was hired

into the tire recapping department.on May 26, 1969 (A. Ill

763; 613).

~ q}“ p v ‘ • V'i Q

Since the early 1960 ’s, MAS hud a policy of not posuing

12/

gob vacancies. 3 cl XT G■isult of no-pcsting policy, the black

11/

nu

Ur.

tor.otrve

it Rebuild

(A.Ill

K

MAS po:

entire

helper

infra,

B

T i

Pa

cL ;

> /

sailer

rts

-625),

13

5

2

2

4

lore have been two exceptions to that rule. In 1970

.2 an evening for a tire truck delivery job to the

ck force. MAS posted notice about mechanic’s

job - done on a one time basis (A.I 61, n.4). See

32-46 , section 8 , Individual plaintiffs.

-22-

employees had no knowledge of any job openings in the other

departments at MAS, except on a perchance basis. The court

below found that this practice deprived the black community

of Winston-Salem of information about job vacancies in the

all-white departments at MAS (A.I 60-71).

5. Joint Hiring Procedure

McLean and MAS have a joint hiring operation. McLean

does the initial screening and testing of applicants. The

personnel office where these operations take place is located

on McLean's property and staffed with McLean employees. The

personnel files for both McLean and MAS employees are kept in

that office. The same application form is used for both McLean

and MAS. The form has the heading "McLean Trucking Company,

Winston-Salem, Worth Carolina, Application for Employment."

After a person passes the screening and testing process, he is

referred to a department supervisor at either MAS or McLean for

final approval. MAS and McLean signervisors make the final

decision in hiring their employees but have no control over

who is referred to them for hiring (A.I 61).

The officials who interview applicants testified that they

refer applicants to specific jobs on the basis of work orders

from the departments at McLean and MAS and on the basis of an

applicant's request. If no job openings exist at the time, the

interviewer places the application in piles, differentiating

-2 3-

between those applicants who have special skills and those who

do not. No attempt is made to demarcate between potential MAS

employees or potential McLean employees. One interviewer

testified that he refers an applicant to a particular job

based on his' evaluation of the applicant’s interest, education,

and past experience. He said that he never gave an applicant

an option of taking a particular job. He said it was incon

ceivable that a person would be cjualifiod for more than one

position at either McLean or MAS. Another interviewer stated

that if two jobs were open at the time, he would ask an

applicant about his job preference and would give him the

choice of which job to take. (A.I 62; see also plaintiffs’

Exhibit 9 and 16).

The application form also has a space for listing job

preferences. However, the interviewers do not explain the

different job categories at MAS or McLean to the applicants.

^ • Hi ring .St andards at MAS And McLean

Since the mid-1950's, MAS has required that new employees

meet certain qualifications. They must have a high school

education or its equivalent, be twenty-one years old, not be

related to another employee, and have had no previous employ

ment with either MAS or McLean. MAS also requires that the

applicant obtain a minimum score on a Wonderlie test, which

measures mechanical aptitudes kills and motor dexterity. The

-24-

minimun score needed on the commercial tests given is the

national cutoff or a lower score, as determined by the test

maker (A.Ill 584-590; 760; 898). The only employees needing

a special skill are the ones assigned to the trailer depart

ment,' in which case they must know how to weld (A.Ill 760).

Otherwise, the qualifications are the same for every other

position at MAS.

Aside from numerical differences in the test scores or ago

of the indivi cu at, the general qualifications

road or termiii a 1 job at McLean are about the s

588-590. ho special skills are required for t‘

fact, McLean prefers to train its over-the-roa

It is one of the few companies having a driver

hose jobs. In

for its truck drivers. All drivers, regardless of their past

experience, must attend the school (Id. 860). The program lasts

three weeks and includes classroom and road driving training.

The only driving experience necessary is to have driven a

vehicl

drivir

during the four sea

gxDGm ionc0 need not

is needed, or in fa

B e s t r 5 c t i 0 0n E:

•’c! an aiL Cl i'bib i. s suit Of:

a. Contract Provisions

To a limited extent, the collective bargaining con

tracts covering employees at McLean and MAS determined their

-25-

mobility between jobs at the companies. The contracts them

selves neither permit nor prohibit an employee from seeking

another job position. However, the contracts do afj.ect.

mobility in that they contain seniority provisions which affect

bidding and layoff rights and other valuable rights an employee

may accumulate via longevity at a particular position (A. I

12-13) .

At least since 1964, all three of Local 391's contracts

with McLean and MAS have seniority provisions. The over-the-

road supplement, the city cartage supplement, and the main

tenance contracts all provide for company seniority measured

from the last date of hire with the company. Company seniority

13/ , „

is used for determining vacation rights only. The over t e~

road supplement provides for terminal seniority for McLean

drivers determined by the length of employment at the terminal

14/

for purposes of bidding on runs and for layoffs and recalls.

The April 1, 1967-March 31, 1970 city cartage supplement for

terminal employees (switchers, checkers, local or city drivers)

had two types of seniority: terminal seniority which governed

vacation rights and classification seniority which governed

promotions and layoffs— 7 . Under the April 1, 1970-June 30, 1973

collective bargaining agreements.

13/See Plaintiffs1 Exhibit 29, Article 5, Section 2, p.10

(the June 1, 1967-March 31, 1970 maintenance contract).

*1 4 /See Plaintiffs' Exhibit 27, Article 5, Section 2, p.59

(the April 1, 1967 to March 31, 1970 over-the-road contract).

1 5 / . _ . . • ~ .r I n..t ’bi J. no a v f- ■? r» ] r» 4 0 T TO „ 50 — 61.— See Plaxntins

-26-

classification seniority was eliminated and promotions and

demotions were governed by terminal seniority

Under the maintenance agreement covering MAS employees

there are two types of seniority in addition to company

seniority. One is departmental seniority which is the

length of time spent in

other is classification

17/

a particular department. The

seniority which is the length of

t ime in

partment.

a particular classification within a particular de~

18/

Under the maintenance contract classification

seniority is used for selection of shift, workweek prefer

ence. As vacancies in higher classifications within a depart

went occur, preference is given to the employee in the next

lower job who has the greatest classification seniority.

Departmental seniority is used for layoff and recall. In

the event of layoff, an employee who had fully exhausted his

departmental seniority could use any departmental and classi

fication seniority he acquired in another department to bump

19/

back into that department. In the event MAS promoted an

employee in a particular department into a higher classifica-

16/

95-98.

See Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 30, Article 42, pp.

>OG £.£. Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 29, Article 5, § 1.

18/ — Id.

19/id . at pp. 10-13.

-2 7-

tion within that department were given the right to bid on

the opening ahead of new hirings. The seniority provisions

governing promotions did not affect plaintiffs in any way

because there was only one job classification in the tire

recapping department.

8 . No Rehire Rn .1 e

McLean and MAS had, until enjoined by the court on

January 2 3, 1974, two rules that prevented job movement be

tween and within the two companies. The first one was the

no-rehire rule. Both companies had a policy of not rehir

ing an employee who had quit his job. Neither McLean nor

HAS would hire back one of its former employees nor hire a

former employee of the other (A.III. 587 (Para. No. 3);

838-839). The court found that while the rationale of the

rule appeared to concern mostly the experience McLean has

had with its over-the-road drivers, the rule was applied

to all departments of.McLean and MAS (A.I 65, Finding No.

17).

9. No Transfer Rul.e

McLean and MAS had a policy, also enjoined by the court,

which prevented transfers between the two companies and be

tween different departments within the same company. As

with the no-rehire rule, nothing in the collective bargaining

contract mandated this position taken by the companies

(A.I 65, Finding No. 18).

pGOx-oqq-xoAO oourg • quouiqucdop ouigs oqq uiq^tw sqoC fiuxfjucqo

utoxq saoAoqduia qxqxqo.xd qou pxp aqua' xoqsuuxq-ou oqj,

•(Z9Z-15Z ‘9VZ-WZ TL'M) °TU-‘C

aojsue.xq-ou oqq jo uoxqefjoxap quaxGddc ux 'uoxqooxxp quautofiG

—ugui uo quamq.XEdop qoexq Tie ug 'quoutqxEdap BuxcTcigoox o.xxq oqq

oq poxxajsuExq s e a u o u u e q 'xoqex x e oA ouo 'oxnx oxxqox-ou oqq

:ro uoxqsioxA quoxsddE ux ‘ (poxxq ax a a sqoEqq qaxqw ux squoiuqxEd

~op aoxqq sqq 5 0 ouo) ouoq s d t a x s s oqq ux qxo/-\ oq s ® °d °:r'-‘q

m s u 13 so pQGT ux pouxxtqax oq -oouoquos uosxxd e o a x o s oq £561

ux qxoq puE quouiqxsdop axxq oqq ux 0S6I ux poxxq s ea oq q^qq

paxqxqsoq u o u u e o qqxqxcxnx'd 'uoxqxppE uj * (p * ojsi * Bxej *Pl) S W

qt> quautq.xndop oqq ux uguio6 g x g 6 e oq UEoqow qu .xoqxueL xo uoxq

-xsod oqq uioxq xaqsuExq oq pottoXTG sea ocp\ (quAqj 'I sauisr) 3{OSiq

ouo oq paxqddE suoxqdaoxa oqq, 'ooAo[diuo oqq qo uioqq°ud xsuosxad

X'Exoods autos jo osnaoaq paqqxutxod o x o a puo 0961 ouoqeq poxxnooo

uiaqq _qo qsovj • [ZV * °N qxqTLLxa . sjqxquxEXd] Aaxfod , saxueduioo oqq

uioxq suoxqcxAop qons qqfixa saoi[s pioosi oqi, "oquu xoqsucxq-ou

ox[q pue aqnx oxxqox-ou oqq oq suoxqdaoxa uooq pau oxsqj,

(99-59 ‘PI)

squauiaoxSE aouEuaquxEiu xo 'aBsqxEa Aqxo ' peox-aqq-xaAO Aq

poxaAOo sqoC oqq uooMqaq xaqsuExq qou pqnoo ooAoqdiua ue ' snqq

* soxuGdutoo oqq uxqqxA\ pue uooAqoq sxoqsuaxq oq paxqddE a [ n.x olUi

•xaqqoue oq qxun qouxquoa ouo iuoxj sooAoxdiuo Aq sxojsuExq 6ux

-qxqxqoxd Aox [od e paq s ® puc ueaqow '0961 qsEOq qG uioxq

-2 9-

drivers comprise an entire department and a single classifica

tion, the exception to the rule di.d not apply to them. It did,

however, permit transfers within departments under the city

2 0/

cartage and maintenance agreements.

At least beginning with the 1964 contract, employees

under the city cartage contract could transfer within that de

partment between classifications. For example, a person could

transfer from being a switcher to a city driver job. In 1960

McLean posted a notice at the terminal requesting applications

for the position of city driver. (A.Ill)

In the 1960's an employee at MAS could transfer within

his department to different classifications. However, until

1964 the employee would lose his seniority if he, for example,

moved from a helper classification to mechanic in his depart

ment. Inter-departmental transfers were not permitted, and

further job openings were not posted. After 1964 an employee

could move within his department to a different classification

and retain his departmental seniority so that in event of a ,

layoff, an employee can exercise his full departmental senior

ity to bump back into a lower classification he previously

held in that same department.

Since the only classification in the tire recapping and

2 0/

Various reasons were assigned by officers of McLean and

MAS for the no-rehire and no-transfer policies and each reason

was rejected by the court below as a basis to deny relief in

this case. See (A.I 66-67 ).

. j

j

m

-30-

service lane departments is that of garageman, and the only

classification in the janitorial department was janitor, an

employee had no place to move in those departments. The no

transfer rule prevented him from moving to another department

in m a s or to another job or department at McLean (Id.)

In 1970 MLS and Local 391 agreed to a contract provision

under which garagemen (tire recapping and'service lane employees)

at MLS were given the opportunity to bid on vacanc.it.,: in helper

positions arising at MAS before the company could hire off the

street. That provision, Article 5, Section 2 or the April. 1,

1970 to June 30, 1S73 contract provided (Plaintiffs' Exh. 32):

(c) Job Vacancy and Promotion

When the company mates a

classification within a

men by seniority in the

promotion to a higher

department, qualified

next lower classifica

tion of that department will be given the op

portunity for promotion ahead of new h ir ing s .

Where there is a need for an additional helper

in any department covered by this Agreement,

any employee classified as garageman who is

qualified as set out in Article 23, Section 4,

or 6 (b), shall have the right to bid for such

work. The senior qualified employee bidding

shall be awarded the work, but he shall become

junior in the new department, for all purposes,

except he shall, have Company seniority for

fringe benefits.

If any qualified employee refuses a promotion into

a higher classification when offered by the em

ployer, he shall not thereafter be eligible for

promotion during the term of this agreement.

In event the Company and Local 391 could not agree on

the garageman's qualifications, a qualifications committee was

set up to determine the qualifications, if necessary. Shift

and workweqk preference under the new provision was based on

an employee's departmental seniority. Employees retain their

old departmental seniority, and in event of a layoff, they

could exercise that seniority to bump back into their old de

partment, if they had acquired .enough seniority within the old

department to do so. See Plaintiffs' Exh. No. 32, Section 2(a),

p. 1 1 .

New employees hired directly into job classifications at

MAS other than garageman or janitor were not required to appear

before the qualifications committee (A.Ill 577). A Vice Presi

dent of MAS testified that the plaintiffs Hairston, Henry, Kim-

ber, Warren (no longer employed), Brown, Caldwell, Landrum,

Grier and- Olstead were qualified for helper positions in depart

ments other than the trailer shop and that Olstead, because of

his previous experience as a welder, had potential to move into

the trailer shop (A.Ill 765). MAS, through Park, admitted that

these plaintiffs based on their "recorded pre-employment" (Id.)

were qualified even without the necessity of appearing before

the qualifications committee.

Before MAS established its current day hiring standards

in the early 1960's all of the employees except the garagemen

had been given the opportunity to move into higher paying classi

-32-

fications. Park further testified that black garagemen and jani

tors were not given this opportunity because MAS and Local 391

were engaged in "lengthy meetings" about an apprenticeship pro

gram for garagemen and that these meetings had been going on

over a period of nine years (A.Ill 804-807). None of the white

emplovees had been required to go through apprenticeship pro—

gr See Plaintiffs' Exh. Nos. 29, Article 40, and

32, Article 40, p . 62.

10. Plaintiffs 1 Employment at MAS

The court below summarized plaintiffs' employment with

MAS in Findings Nos. 24, 25 and 26 (A.I 63). This summary ap

parently was the basis on which the court concluded that except

for nairston Wax're: no evio ,~as presented 'others

subjectively or objectively sought a xn

and some even rejecte

detailed statement of

. offered opportunities

plaintiffs’ testimony

ii

their employment

(A. I 8 8 ). A more

therefore neces

sary .

Before dealing with the individual testimony of the

plaintiffs we set out here several undisputed facts that bear

on the back pay issues before the Court:

(A) None of the plaintiffs were offered the opportunity

to move out of the tire shop prior to January, 1970 when the

tire delivery job was posted (See A.Ill 753; 1007-1012).

(b) Between July 2, 1965 and December, 1969, 26 white

employees were employed in the automotive, unit rebuild, paint,

-33-

trailer and parts departments (A.Ill 603-615). None of the

plaintiffs were offered these opportunities even though the

vice president of MAS had knowledge that cit least some of the

plaintiffs had the "indicated potential" to move into these

departments (A.Ill 765).

(C) Plaintiffs had no way of knowing when vacancies

occurred in other departments because notices of vacancies were

not posted.

(D) The no-rehire and no-transfers policies of MAS and

McLean were a complete bar to any efforts on the part of the

plaintiffs to seek upward movement at MAS or re-employment in

any job at McLean.

(E) MAS admitted that it intentionally made and kept

the tire department all black from 1963 until May 1969, the

later date being almost four years after the effective date of

Title VII (A.Ill 761-763).

(F) Plaintiffs could not file a grievance with com

plaining about racial discrimination because the president of

Local 391 testified that there was no contractual provision on

which to base such a grievance (A. II 548). A non-discrimination'

provision was included in the maintenance contract until the

1970-73 contract. Compare Plaintiffs' Exh. No. 29, p. 55 and

Plaintiffs' Exh. No. 32, p. 6 c Article 37.

Prelow E. V7vnecoff

Wynecoff has been employed in the tire department since

-34-

Juno 11, 1950 (A.Ill 595 [Tire Recapping Roster]). In about

1962 (A. II 179) lie asked his supervisor about the opportunity

to transfer to the tire delivery job after the white employee

then holding the job left. Ills supervisor told him that lie could

not transfer out of the tire shop (A .'II 171-174; 183).

Wynecoff also testified that he and plaintiff Allen talked

with the president of Local 391 , Ralph Durham, in .1970 about-

transferring out of the tire shop. Durham told Wynecoff he

would talk with Ehrliardt. Durham reported to Wynecoff that

Ehrhardt said it was not possible to transfer out of the tire

shop (A.II 176-177; 187-188). Wynecoff had lost interest be

cause of age (45) in the tire truck delivery job when it was

posted for the very first time in 1970 (A.Ill 179). Wynecoff

signed up for the helper's job posted in 1970 but he did not

appear before the qualification committee (A.II 180). Although

Wynecoff wanted the helper's job, he was not enthusiastic about

it if it required working the night shift or being off Tuesdays

or Wednesdays instead of Saturdays and Sundays (A.II 192).

Elmo Fries

Fries started with MAS on July 8 , 1949 and was one of the

original employees in the tire shop— (A . II 196). At the time

of trial, he had about twenty-two years at MAS. Two white

2 1/

Fries "came along with the equipment" from MAS's

predecessor in interest (A.II 202).

-35-

persons started at HAS on the same day as Fries, Thompson and

Petrov, doing the same kind of work. Petrov eventually retired

but Thompson who was still employed had been promoted to a super

visory position (-fi.il 197). Lewis Naylor, also white, at one time

also worked with.Fries (A.II 199-200). Naylor was employed on

June la, 1954 and on July 13, 1956 was transferred to the trailer

department (A.II 609). As of 1969, Naylor was an A mechanic,

earning $3.93 per hour whereas Fries, still a garageman,' was

earning $3.64 per hour (A.Ill 602). Fries applied neither for

the tire delivery job nor the helper's position (A.II 203-204).

tries was employed prior to the "current day" hiring standard

of i-.AS (a . Ill 765-766). Had Fries applied for and been assigned

to the v_ire delivery position, he still would have been assigned

to the tire, recapping department. When James Odel Shore, white,

had this position in 1969, it was assigned to the parts depart

ment (A.Ill 612); and the notices posted in January and Febru

ary, 1970 stated than this job was being assigned to the tire

recapping department and would constitute a separate seniority

list (A.Ill 1007, Para. 2).

Robert C, Klmber

Kimber was employed in the tire shop on May .13, 1964

(n.il 20o; A.Ill 613). In 1966 or 1967 he asked his supervisor

about transferring to the.tire delivery job but was told he

could not transfer (A.II 203 [135]). At this time the tire

delivery job was in the parts department (A. Ill 612).

-36-

In .1967 or 1968— when Park and Ehrhardt mot with the

black employees to reprimand them because they were not properly

performing their jobs, the black employees advised Park and E'ni-

hardt that they felt that they were not being treated fairly be

cause they were black and because they were stuck in dead end

jobs.” In response to this concern, Kimber1s uncontradicted

testimony is that Park stated "The sarnie qooi is open that you

camethrough when you came in" and "if we don't like it, ... we

knew what we can do" (A.II 212). MAS presented no evidence to

24/the contrary.'

Kimber admitted that Park told him that he would not

lose his seniority if he had taken the tire delivery job (A.II

p;i9 ). But then this job had been assigned to the tire recap

ping department and would not involve transfer to another de

partment (A. Ill 1007).. Moreover, Park had stated that he had

considered the reason given by Kimber for. refusing the tire

--— Kimber testified the reprimand meeting took place in

1967; Ehrhardt testified this meeting took place in 1967 or

.1968 (A. Ill 867-868).

23/Ehrhardt was also at this meeting. When asked whether•

ho recalled black employees had stated to him that they felt

they were stuck in dead-end jobs because they were black,

stated "1 do not recall such a statement," (A.Ill 867).

2 4 / Compare

c a l l e d a s a w i t n e s

Simmons, a w i t n e s s

i t was p o s s i b l e t o

the testimony of Rigsby Satterfield (A.II 462)

s for McLean to rebut the testimony of Roy L.

for the plaintiffs that Satterfield had said

earn $18,000.00 as a road driver (A.II 145).

-37

delivery job "good and sufficient"(A.Ill 749-750).

Kiirber applied for the helper's job after it was posted

25/

subsequent to April 1, 1970. He did not appear before the

cualifications committee when requested to do so (A.II [150-151])

However, Park testified that timber was already qualified for the

helper's position (A.Ill 765).

Dewello C . Counts

Counts was initially employed at MAS on May 11, 1954

(A.Ill 595). He never asked any official about the opportunity

to transfer out. of the tiro shop (A.-II 241 [168]). Counts is

the onlv plaintiff who testified that he never wanted a job

other than that of garageman (A.II 244 [171]).

Loo D.__Cannon

Cannon was employed in the tire recapping department on

March 3, 1950. After serving a prison term for about eight

months in 1953, he was re-employed on May 11, 1954 (A.II 251;

A.Ill 613). He testified about two white'employees, Naylor and

Manning, who at one time were working with him, but who were sub

sequently transferred to other departments at MAS (A.II 247-

248). Cannon retired on March 3, 1970 (A.II 252), and about

a month later blacks in the tire shop were, for the time, given

the opportunity for other jobs. Cannon testified that he had

fL-v Garagemon were given the opportunity to bid for helpers

positions for the first time under the April 1, 1970 - June 30,

1973 collective bargaining agreement.

-38-

never applied for a road job but that he had "seen times when

he wanted one"(a.II 254-255). Cannon's entire career with MAS

was during the period of time when MAS was openly engaged in rac

ially discriminatory practices.

Willie Neal, Jr.

Peal was employed on June 6 , 1958 (A.II 260). Peal's un

contradicted testimony is that in 1969, he saw the tire delivery

truck setting idly and told Park he would like the job if it was

available. Park told him "there is no way you can drive it be

cause vou're already working for the Company"(A.II 263). Neal

then expressed his concern about wanting to grow as the company

grew, but Park told him "hell, that's just the Company policy.

"he don't transfer" (A.II 263-264).

lifter the notice about the helper. position was posted,

in 1970, Neal spoke with Durham, president of Local 391. Durham-

told ileal he would not qualify for the position if he failed to

sign the notice (A. II 267-268). Neal further stated that lie

did not bid for the helper's position because the notice did

not state the department it was in (A. IT. 267-268).

Neal did not attempt to bid for the tire delivery job

because he was told that he could not return to the tire re

capping department if he took the job and found out that he

could not do it (A.II 281).

In response to questions by Judge Stanley about "how

the cornuany had treated [him] wrong," Neal testified that on

-39-

ono occasion he was told he could not transfer to the tire de

livery job and on another occasion he was told that he could.

He further stated that he didn't want to take the job with the

possibility of losing his 12 years of seniority if he did not

prove successful on the job and end up being forced to leave

or being fired (A. II 283-284). He further stated that other

employees [whites] had been on the tire delivery job and when

their health declined, they returned to their old jobs, but

MAS would not assure him that he would get similar treatment.

On cross-examination Neal denied that he had failed to

apply for the helper's position because he might have to work

Saturdays and Sundays. He testified that as far as he was con

cerned "five days is just five days"(A.II 289). His main reason

for not bidding for the helper's position is that he would not

get the benefit of his full company seniority and that he would

have to start in a new department as the "bottom man"(A.II 289-

290), and would have to stay in the helper's position for two

years before he could move up.

Richard A. Landrum, Sr.

Landrum was employed by MAS on September 30, 1963 (A.II

2 9 3 ). lie testified that he never had any in-depth discussion

with any official of MAS because of the 1967 or 1968 meeting

with Park and Ehrhardt when transfers were discouraged and

plaintiffs were told they could not transfer (7i.II 296-297).

lie did not apply for the tire delivery job because he did not

-40-

believe that he was physically capable of doing the job (A. II

298-299). He also did not apply for the helper's job. If Lan

drum had applied, he would have been subject to review by the

qualification committee, even though Park testified that Lan

drum was already-qualified for a helper's position in any other

department except the trailer department (A.Ill 7S5).

Josep?i P . Jack'son

Jackson was employed on January 20, 1957 (A.II 324-325).

He made no efforts to try to transfer out of the tire shop be

cause ''a few of the fellows" that he ̂ worked with had tried to

transfer; 'they didn't get any results from it" so he didn't

try (A.II 325). He did not apply for the tire delivery job be

cause it was not costed until after the lawsuit was filed (A.II.

an a a ?

Bobby L. Grier

Grier was employed by HAS on June 22, 1964 (A.Ill 595).

In 1957, Grier discussed the matter of the opportunity of blacks

transferring with the president of Local 391. The vice presi

dent simply told him that MAS did not allow inter-departmental

transfers (A,II 339-340).

Grier did not apply for the tire delivery job because he

does not know how to drive (A.II 340). He applied for the

helper's position, but a union representative told him he did not

have to take any additional tests because he was already quali

fied (A. II. 340-341). then Grier learned that MAS had set up

an apprenticeship program at Forsyth Tech and that persons coming

-41-

out of that program were being hired into helper's positions,

ho again contacted Local 391 and apparently Local 391

intervened (A.II 341-342). Grier did not appear before the

qualifications committee, even though he was specifically re

quested to do so (A.II 349-350), but Park testified that Grier

was already qualified for the helper's position (A.Ill 765).

Robert_L. Henry

Henry was employed by MAS on July 22, 1963 (A.II 354).

His employment had been specifically solicited by MAS (A.II

345-355). There were two openings at the time he was employed,

1 t1C 0 X* CC 0p ping -1 -J-d C MAS and the dock at McLean. The interviewer

encouraged him to take the?. tire recaprDing department (Id.).

Henry d ?. d not• nnolv for t h e t i r e deliver'7' vacancy because

he did not think $.09 more per hour was enough money for driving

a truck on the road, being away from home and doing a] 1 the

work by himself (A.II 356-375). He did not apply for the

helper's position because he did not want to lose his seniority

(Id. 366), Henry further testified that he had not specifically

requested the opportunity to move out of the tire shop but he

was present when this matter was discussed with the president

of Local 391 and that he "just took it for granted that there

wouldn't be any use"; he didn't believe in "bumping his head

against a stone wall" (A.II 356). In 1947 Henry had applied

for a road driver job (A.II 362) but this was during the time

-42-

when McLean had a practice of refusing to hire blacks for this

position. By the time of trial he was no longer interested in

a road job because he was then 42 years old (A. II 367).

Henry stated in his deposition taken in 1970 that he was

not then interested in another job but he also further testified

that if he had been given the opportunity to "build the seniority

that [he has] now, he would have taken it (A.. II 366).

W il hi am N. CaIdwe !Q

Coldwell was emp 1 oye<1 on May 13, 1963 (A . II 371). He did

not apply for the tire delivery job because he saw no advantage

for the $.09 difference (A. II 373). He did not apply for the

mechanic's helper job because he wasn't interested in it, but

he was interested in a position in unit rebuild (engine room)

(A. II 374; 376; 378). Caldwell had not indicated his prior

experience with engines because the application requested in

formation only about the immediate past three employers (A. II

374). Caldwell affirmatively disclaimed that the possibility

of working on Saturdays and Sundays played any part in his

decision not to apply for the mechanic's helper job (A. II 380-

381). In fact, shortly before trial he had been shifted from

his Monday through Friday garageman's schedule (A. II 380).

43-

t i re r e cap p i ; ig and s e r v

COu r a g e d Bro' ...rtj from j___

Br own It

i . ta: 1 1 i f y o u do

da v s yo u O (C g o i n g t o V

g o i n g t o g e t / t h e s âme

Brov,rp f-e s t i f i e d D L'

W ilero3 t h e su b j c c t rra t t e

sh o p wa s di.3 cu[S S €1(3 mV1

C lint on Brown

Brown was employed on S e p t e m b e r 12, 1966 (A. H 383;

A III 595). There were several jobs open-dock at ^cLean and

,ice lane at HAS. The interviewer dis-

ra taking the dock service lane jobs by telling

do to the dock/ . . . you don't know which

off; you don't know what shift you're

3 the service lane" (A. II 335-386),

about a meeting vJith officials in 1967

of advancement for blacks' m the tire

group was told they could not transfer

because it was against company policy (A. H 386). arown

testified about a meeting of a group of the plaintiffs with the

president of Local 391 on an occasion in 1970 where the subject

matter of transfers, among other things was discussed, e.nu

president told the group that it was against company policy to

allow transfers (A. II 386-387). lie recalls however that the

plaintiff had raised the issue of transferring and he told them

he would speak with an appropriate official. Tne President

later reported back to the group only to relay the message that

it was against company policy to allow transfers U d - )•

Brown did not apply for the tire delivery job because he

was already earning $6 ,0 0 0.0 0-$7 ,0 0 0 . 0 0 per year and the job

-44-

did not pay much more than that, whereas over-the-road drivers

were earning $15,000-$16,000 per year (A. II 388); further

hG ,aw no future in that job (Id.). At trial Brown affirmatively

stated that lie was interested in a road driving position (A. II

390 ), or any job other than garageman (A. II 397).

jamos Olstead

01stead was employed on January 6 , 1954 (A. II 399). Prior

to his employment at MAS Olstead had completed a welding course

at New York Trade School. Thereafter he had worked at Bethlehem

Steel (New Jersey), Gary Tank Corporation (Now York) over a

bout eight and one half years doing welding and

4U0). Olstead had discussed

period of aboi

shop work (A. II

r- r.' y\ "1 r'i 'i rt <~» V —

perionce with the interviewer at the time he applied (A. II

400-401).

In the summer of 1970, two years after this suit was filed,

Olstead was offered a position in the trailer shop at an in

crease of $.79 per hour. He was told that if he took'the job,

he would have to go to the bottom of the seniority roster and

for bidding purposes he would have "to work at night or what

ever was left over" (A. II 401-402). Olstead declined the

offer because he didn’t know what effect the acceptance would

have on this lawsuit and he did not relish the idea of working

at night and being away from his family (Id.). The fact that

-4 5-

he may have ha cl to work weekends in no way influenced his de

cision to decline the offer (A. II 403); nor did the possibility

that he may have had to buy his own tools (A. II 408-409).

Between the time of Olstead's employment i.n January , ldo4

and the offer in 1970 at least twenty-one whites had been hired

into the trailer department. Three or these had advanced above

the helper's classification (Wassum, Wagner and Worsham) (A.

Ill 609-510). In less than three years Worsham had advanced to

Iv e hiohest osv position as Trailer mechanic h at the rate of

$3.93 per box r; whereas Olstead was earning only $3.64 per hour

(A. Ill 602).

•.an L. Cut lire 11

Cuthrell was employed on August 14, 1957 (A. II 165).

There is nothing -in the record about' why Cuthrell did not apply

either for the tire delivery job or the helper s position, -se

A. II 165-169.

W i H i e C. Allen,' Jr.

/illen was employed on December 9, 1953 (A. II 99 j ) , he

left voluntarily in October, 1969, but after this action was

filed. lie never asked about transferring out of the tire shop,

but he is one of the plaintiffs who Park stated had potential

for the helper's position (A. II 765). All spoke with the

^resident of Local 391 and was advised it was against company

-46-

policy to transfer (A. Ill 1006).

Thcodore R . Warren

Warren was granted back pay by the court below because the

court found he had been discriminated against because of the

refusal of MAS and McLean to permit him to become a road driver

(A. I 88 ). The only issue in this appeal as to Warren is

the 1968 date allowed by the court from which back pay is to

begin to run.

Warren was employed on June 22, 1964 (h. Ill 595). He had

truck driving experience prior to his employment (A. II 117-

118). The charge Warren filed with EEOC on May 31, 1967 stated

that he haa asked for an over—the—road job as early as

September, 1965 and had been told there were no openings. [See

Plaintiffs'- Exhibit No. 1], When he made further efforts in

1968 he was told the same thing; he then requested the opportunity

to fill out an application, but was told the only way lie could

get a driving job was to resign his job at MAS and re-apply.

He eventually did resign, he was not given any consideration be

cause of the non—rehire policies of MAS and McLean. Warren

had also tallied with the president of Local 391 in 1967 about

a road driving position (A. II 544). Between 1965 and 1970

McLean hired well over 75 white over-the-road drivers. (See

A. Ill 617; 622-625).

ARGUMENT

I

THE REASONS ASSIGNED BY TIIE DISTRICT

COURT IN CONCLUDING THAT ONLY TWO OF

THE NAMED PLAINTIFFS WERE ENTITLED TO

b a c k p a y a r e n o t j u s t i f i e d o n t hi s

RECORD AND ARE NOT SUPPORTED BY APPLICABLE

LEGAL PRINCIPLES.

A. The Record Clearly Demonstrates That Plaintiffs And Other

BlacAs Suffered Economic Loss Because Of The Admitted

Racial Hiring Practices Of NAS And McLean.

Section 706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(g)

provides that

If the court finds that the respondent has

intentionally engaged in or is intentionally

engaged in an unlawful practice charged in

the complaint, the court iuay enjoin the

respondent from engaging in such practice,

and order suet affirmative relief as may he

appropriate . . . with or without hack pay.

"Intentionally" as used in Section 706(g) has been construed

to require only that the defendant meant to do what he dicl,

that is, his employment practices were not accidental. Robinson

v. Lori Hard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 796 (4th Cir. 1971), cert.

dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); Local 189 United Papermakers

and Pap°n,'n^ffi-s. AFL-CIO. CLC V- United States, 416 F .2d 980,

Cir. 1969), cert., denied, 39 7

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 4 2 4

-40-

Not onlv was the unlawful racial discrimination practiced

aaainst all the plaintiffs and other blacks here "not

accidental;" it was encaged in purposely and deliberately.

Leonard Park, vice-president of MLS, met with the supervisor

of the plaintiffs in 1963, two years before the effective date

of Title VII, to discuss whether MLS "would -continue" to hire

blacks only for the tire recapping department. The supervisor

recommended that MLS should. Park "concurred" notwithstanding

Vj-: :■ specific recomrnendation that MLS "begin a program to integrate

production emoloyeos in this area of responsibility (.A. Ill 761-

- y a . \> m

xkll of the plaintiffs were hired into the tire recapping

deT"S'‘tment at a time when MLS had an admitted practice of

discrimination

■t— U O I V :

P a r k f u r t h e r t e s t i f i e d t h a t t h e d e c i s i o n was

'the spring o f IS0.^0 t o b e g i n a p r o g r a m o f

h i r i n g C a u c a s i a n e m p l o y e e s i n t h e t i r e r e c a p p i n g p l a n t i n an

e f f o r t t o , i n seme way, b r i n g a b o u t an i n c r e a s e i n p r o d u c t i o n

p e r m an -h o u r t r e n d i n g t o w a r d h i s t o r i c a l levels" (A.Ill 763).

The clear implication of this testimony is but for the decline

in the production and workmanship of the plaintiffs, MAS would

have continued its admitted racially discriminatory hiring

practices weli bevono May, 196S.

Once the plaintiffs were hired their employment future

with MAS and with McLean was foredoomed because of the no-rehire

-49

and no-transfer policies. Janitors and garagemen were the

lowest paying -jobs in the bargaining unit at MAS (A. Ill G02).

Until 1970 all of the blacks at MAS were in these two jobs.

There were no advancement opportunities because garageman

was the only classification in the department (A.Ill 613).

The plaintiffs could not transfer to any other departments at

MAS under any circumstances. Nor could they leave MAS and

seek employment with McLean. Plaintiff Warren tried this route