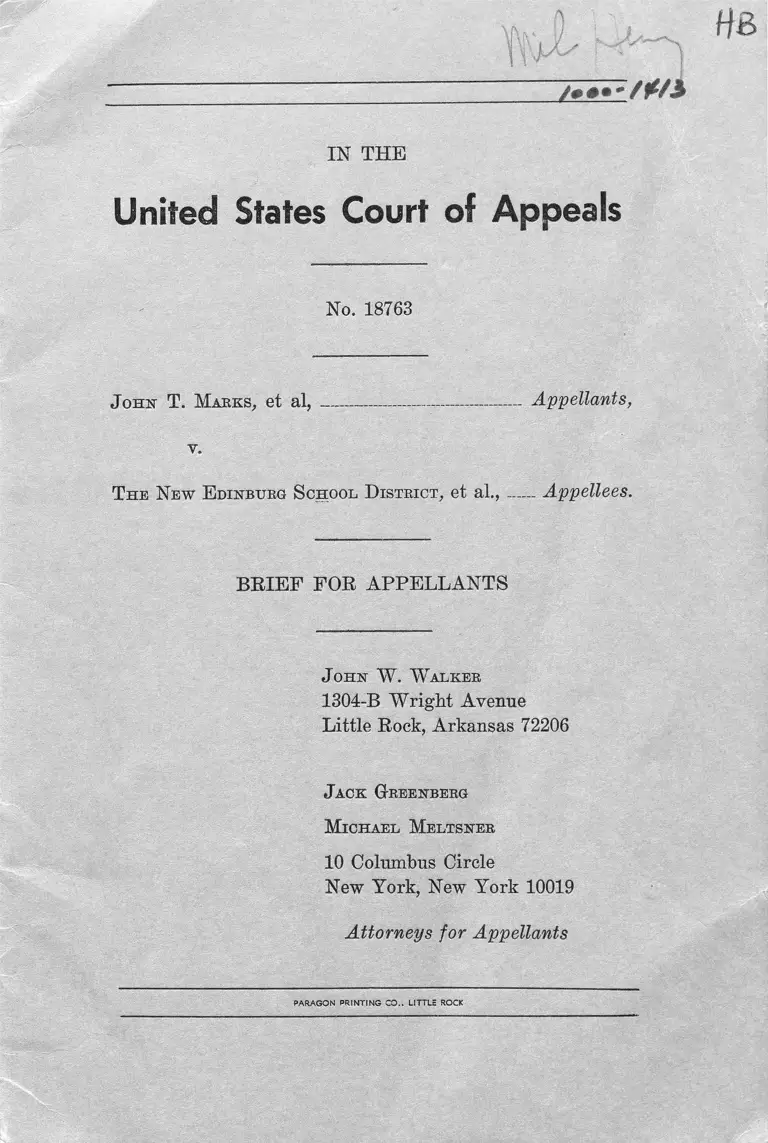

Marks v The New Edinburg School District Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 17, 1967

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marks v The New Edinburg School District Brief for Appellants, 1967. 52306b0e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/67f7d669-178f-421c-80ee-52ac93815b2a/marks-v-the-new-edinburg-school-district-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

, ) v . H&

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

No. 18763

J o h n T . M ark s , et al, ---------------------------------------- Appellants,

V.

T h e N e w E dinburg S chool D istrict , et a l . , ----- Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J o h n W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

J ack G reenberg

M ich ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

PARAGON PRINTING CO.. LITTLE ROCK

f.

INDEX

Page

Page

Statement of Case ---------------------- -------------------------------------------- 1

Preliminary Statement _______________________________________ 8

Statement of Points to be Argued ___________ __________________ 10

Argument

I The failure of the District Court to require the

admission of Negro pupils residing in the New

Edinburg School District to the New Edinburg

School denies Negro students equal protection of

the laws------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- 12

II The desegregation plan approved by the District

Court is contrary to the ruling of this Court in

Kelley v. Altheimer. ___________________________________ 13

III Appellants are entitled to attorneys’ fees _____________ 16

Conclusion_____________________________________________________ 17

TABLE OF CASES

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va., 4th Cir.,

1963, 321 F. 2d 494 _________________________________________ 16

Board of Education v. Dowell, No. 8523 (10th Cir., Jan.

23, 1967 __________________________________________________ 13

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ______ 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) _______________ 12

Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 661 (8th Cir.,

(1966) _____________________________________________________ 14

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Va.,

177 F. 2d 924 (4th Cir., 1949) ______________________________ 12

Goins v. County School Board of Grayson County, Va.,

186 F. Supp. 753 (W. D. Va., 1960) ________________________ 12

Kelley v. Altheimer, No. 18,528 (8th Cir., April 12, 1967) 14

INDEX — (Continued)

Page

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir., 1965) _________________ 14

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950) ------ -- 13

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) ----------- 13

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) _____________________________ 14

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. R. Co., 186 F. 2d 473 (4th

Cir., 1951) ___________ ______________________________________ 16

School Board of Warren County, Va., v. Kilby, 259 F.

2d 497 (4th Cir., 1960); ___________________________________ 12

Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 131 (1948) ________________________ 13

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770

(8th Cir., 1966) ____________________________________________ 14

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) __________________________ 13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

Civil No. 23345 (5th Cir., Dec. 29, 1966), reaffirmed

en banc (Mar. 29, 1967) ------------------------------------------------------ 13

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

No. 18763

J o h n T. M ark s , et al, Appellants,

V.

T h e N ew E dinburg S chool D istrict , et al., — Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF CASE

This is an Arkansas school desegregation suit filed

by Negro plaintiffs on August 30, 1966, seeking injunctive

relief to have the public schools of New Edinburg, Ar

kansas desegregated (R.l-5). New Edinburg is a small

school district which, during the 1965-66 school year, had

a total pupil enumeration of between 350 and 370 (R.

30). It operated two schools: (a) the “ A ” rated (R.

181) New Edinburg school, a modern brick building (R.

10, 14) attended solely by 160 white pupils in grades one

through twelve, and staffed solely by 11 white teachers

and one white principal (R .ll, 13); and (b) the “ C”

rated (R.181) St. Paul school, a small inferior and in

adequate frame building (R.9, 10, 33, 35, 109, 137, 161,

162) which presented health and life hazards (R.131) at

2

tended solely by between 65 (R.71) and 75 (R.9) Negro

pupils in grades one through six, and staffed solely by

three Negro teachers who received lower wages than the

white teachers (R.9, 77).

New Edinburg did not operate a high school for Negro

pupils in grades seven through twelve. Instead the 55

Negro pupils in those grades attended the all-Negro J. E.

Wallace School in the adjacent Fordyce School District

pursuant to a tuition arrangement between the two dis

tricts (R.71, 73, 74). New Edinburg, however, provided

bus transportation for the Negro pupils (R.12, 79, 89).

This arrangement was approved by the state and county

Boards of Education (R.79, 80).

New Edinburg committed itself to the United States

Office of Education to begin desegregation under the

Office’s “ Guidelines on School Desegregation” at the

start of the 1965-66 school term. The first plan sub

mitted by New Edinburg to the Office of Education called

for discontinuation of the tuition arrangement with

Fordyce and assigning all Negro pupils in grades seven

through twelve to New Edinburg. This could have been

done without major difficulty to the district (R.16). The

lower six grades were to be desegregated on a “ three-

three” basis the next two years (R.15).

New Edinburg rescinded its first approved plan and

substituted in its place a three year “ freedom of choice”

plan of desegregation at the rate of four grades per year

(R.24). The “ free-choice” plan was adopted by de

fendants in the hope and expectation that it would fail

(R.43, 73, 74). In so doing, New Edinburg represented

to the Office of Education that ‘ ‘ Three years is a minimum

period of accomodation and acclimation of the patrons

of the district of both races to achieve a good faith ac-

3

ceptance of desegregation of this important aspect of com

munity life” (R.26). New Edinburg also represented

to the Office of Education that the additional time was

needed to construct additional facilities which wms not

true (R.28-30). On the basis of these representations

the Office of Education approved New Edinburg’s sub

stituted plan thereby permitting the district to continue

its interdistrict, racial assignment policy.

New Edinburg’s first year of desegregation, 1965-66,

in which no desegregation was achieved, worked “ beau

tifully” said Superintendant Splawn (R.27, 31, 32, 34).

All assignments that year were made on a purely racial

basis (R.113).

New Edinburg signed a 441-B assurance of compli

ance form with the Office of Education early in 1966.

Thereunder, appellees agreed to abide by the revised

“ Guidelines” (R.36, 154). Under the Guidelines for

1966, a choice period of thirty days was to be held between

January 1 and April 30. New Edinburg did not hold a

choice period during that time and thus failed to send

parents notice and choice forms as required by the ‘ ‘ Guide

lines” . On April 18, 1966, Negro parents, acting on the

belief that a choice could be made in any manner of writ

ing which sufficiently identified the student and indicated

a choice of schools, filed a petition on behalf of 119 of

their school age children in grades one through twelve

which stated:

“ We the undersigned citizens of the New Edin

burg School District, Cleveland County, Arkansas,

do hereby request that our children whose names

are listed below be registered at the New Edin

burg School for the year commencing September,

1966” (R.132).

4

After receiving the petition, appellees decided to hold

a 30 day choice period beginning May 4, 1966, in violation

of the “ Guidelines” (R.70). Thereunder, “ 93 white

students returned those forms choosing to attend New

Edinburg School out of 122 forms sent. Of a total of 114

forms sent to Negro students, 20 returned the forms

choosing to attend the New Edinburg School and 21 re

turned the forms choosing to attend either St. Paul School

or J. E. Wallace High School” (R.89). Thus, by the ap

pellees’ figures, 29 white pupils and 73 Negro pupils

failed to sign choice forms; these pupils were then as

signed to the school formerly attended (R.113, 114).

The “ second” choice period was given because the

board had not expected so many Negro pupils to choose

the white school and it hoped to reduce the number of

transfers with the second choice (R.43, 44). The board

took the position, however, that the choices expressed in

the petition were not intelligently made, that the sponsors

of the petition acted on the basis of misunderstanding, and

thus, the choices were invalid (R.49, 50, 88). There was

no competent testimony introduced to support the Board’s

position. In fact, testimony presented supported a con

trary position (R.140-142, 150, 151).

The Petitioners did not participate in the “ second”

choice period because they had already made a choiec (R.

148) and were not advised by New Edinburg that their

choices made via petition on April 18 would not be honored

until August 20, 1966 (R.46). This was after the Office

of Education had advised New Edinburg that the petition

was a valid choice expression under the “ Guidelines”

(R.41, 156, 159, 160).

By August 20, 1966, appellees knew that they were in

non-compliance with the Guidelines and that their federal

0

funds would be withdrawn (R.52, 53). Indeed, as at

tested by Mr. Baldo of the Office of Education, apjjellees

violated the guidelines by: (1) refusing to accept the

petition as a valid choice of the parents and pupils; (2)

failing to hold a choice period during the prescribed

time; (3) sending Negro pupils in the high school grades

to a. school outside the district; (4) refusing or failing

to close the small, inferior and inadequate all-Negro St.

Paul School; and (5) not desegregating its faculty (R.

161). Appellees, by refusing to honor their commit

ments to the patrons of the District and to the Office

of Education to follow the “ Guidelines” , forced the Negro

pupils assigned to the all-Negro St. Paul and J. E. Wallace

schools to take legal action to secure relief.

In their complaint, appellants sought to require ap

pellees to implement the Guidelines or equal alternative

relief including the invalidation of interdistrict transfers

which had the effect of perpetuating racial segregation.

They also prayed for cost and attorney’s fees. After

two hearings (R.5-85, 101-206) the court made the fol

lowing rulings, among others, on September 16, 1967:

(1) it would not “ require the district to comply with

the guidelines of the Office of Education” (See also 201-

202)

(2) that Negro high school pupils in the eleventh and

twelfth grades would be given ten days in which to make

a new freedom of choice between the J. E. Wallace School

and the New Edinburg School; and

(3) that appellees present a modified desegregation

plan within 20 days.

The District responded with a modified “ free choice”

plan (R.218-221) whereby: (1) in April or May of 1967,

6

pupils in grades one through twelve would be given

an opportunity to make a choice of schools for the next

school year. The choice period would be fifteen days;

(2) commencing with the 1967-68 school year, pupils in

grades one and seven would be required each year to

make choices; (3) although the district was opposed to

lateral transfers, such would be granted except when

they would result in over-crowding; and (4) faculty

vacancies would be filled without regard to the race or

color of the applicant.

Appellants objected to each aspect of appellees’ mod

ified plan (R.221, 223). Judge Harris thereupon re

quired certain modifications and sought to ascertain

whether appellees proposed to continue utilizing the J. E.

Wallace School in Fordyce and whether improvements

were being made to the St. Paul School.

Appellees’ subsequent modifications re J. E. Wallace,

as approved by the Court, read as follows:

“ This District wall continue to pay tuition and

provide transportation for students in grades seven

through twelve who choose to attend J. E. Wallace

High School as long as a sufficient number elect

to attend that school to justify operating a school

bus for this purpose” (R.228).

Despite the manifest bad faith of appellees and the

fact that there were no meaningful obstacles to full de

segregation in New Edinburg (R.20-24), the district court

approved appellees’ modified plan, retaining jurisdiction

during the period of transition, thereby completely

thwarting, without cause, the Office of Education’s reason

able attempt to enforce Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act. In so doing, the district court invalidated choices

I

made on April 18, 1966, by the petition filed which

had been approved by the Office of Education. Thus,

instead of at least 119 Negro pupils being assigned to

New Edinburg during 1966 only 8 were assigned thereto

by the Court approved plan. Moreover, the district

court order aborted the Office of Education’s requirement

that the grossly inferior, inadequate and unsafe St. Paul

school for 65 to 75 Negro pupils in grades one through

six be closed despite its own finding that St. Paul was

inferior (R.216). The only relief granted by the Court

on this point was a new toilet (R.224). The District

Court further upheld appellees’ interdistrict transfer plan

even though it found “ that the curriculum in the J. E.

Wallace school is somewhat different and to some extent

inferior to the New Edinburg School” (R.216). Finally,

the Court approved a shorter choice period — fifteen

days — than that required under the “ Guidelines” —

thirty days, did not require actual faculty desegregation,

failed to require appellees to make assignments on a non-

racial basis where pupils failed to make choices and failed

to rule on appellants prayer for attorney’s fees.

Notice of appeal was filed by appellants January 20,

1967.

8

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This is another Arkansas case where a School Dis

trict sought and received sanctuary in the federal courts

to avoid complying with the Guidelines on school deseg

regation promulgated by the Department of Health, Edu

cation, and Welfare and enforced by the Office of Edu

cation of that department. This District should long

ago have desegregated completely because it operated a

grossly inferior and inadequate elementary school within

the District for a handful of Negro pupils and it required

the Negroes in the high school grades to obtain their edu

cation in another school district. This District agreed

in 1965, however, to implement the Office of Education

“ Guidelines” and submitted several plans which were

approved by that office. However, absolutely no deseg

regation occured in the first year of the plan, 1965, and

in 1966, when more Negroes chose to attend the white

school than the District expected, the District decided not

to follow the Guidelines. It, therefore forced the Negro

pupils into court for redress.

When the matter was presented to the District Court,

the school board could not reasonably justify its decision

not to implement the Guidelines or to grant the choices

made by the Negro pupils. The manifest bad faith and

arrogance of the District in its treatment of Negro pupils

is evident in the record and has now been given judicial

approval. The District Court, without any justification

whatever, determined that it did not require the Guide

lines to be implemented in this District although the Dis

trict had been committed for two years to follow them.

The fear expressed in Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th

Cir. 1965), has become a reality and another school dis

trict in Arkansas has reaped a benefit for its foot-dragging

9

and opposition to the principle of desegregation. The

tragedy is that it was given federal judicial approval.

Appellants, therefore, respectfully submit that New

Edinburg is a clear example of the type of situation to

which the Fifth Circuit addressed itself in United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, ........ . F. 2 d _____

(5th Cir. Dec. 29, 1966), reaffirmed en banc (March 29,

1967) :

The announcement in H.E.W. regulations that

the Commissioner would accept a final school de

segregation order as proof of the school’s eligibil

ity for federal aid prompted a number of schools to

seek refuge in the federal courts. Many of these

had not moved a single inch toward desegregation.

In Louisiana alone twenty school boards obtained

quick decrees providing for desegregation accord

ing to plans greatly at variance with the guide

lines.

We shall not nermit the Courts to be used to

destroy or dilute the effectiveness of the Congres

sional policy expressed in Title VI. There is no

bonus for foot-dragging.

For the reasons stated in Jefferson County and in

Kemp, and for sound public policy reasons, appellants

urge this Court to require that no less than the minimum

standards set forth in the Guidelines on school desegre

gation be implemented by the district courts when re

calcitrant school districts seek to avoid H.E.W. require

ments by resorting to the federal courts.

10

STATEMENT OF POINTS TO BE ARGUED

i

The failure of the District Court to require the admission

of Negro pupils residing in the Neiv Edinburg

School District to the New Edinburg School denies

Negro students equal protection of the laws.

Goins v. County School Board of Grayson County, Va., 186

F. Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960);

School Board of Warren County, Va. v. Kilby, 259 F. 2d

497 (4th Cir. 1960);

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Va.,

177 F. 2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ;

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938);

Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 131 (1948);

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ;

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).

ii

The desegregation plan approved by the District Court is

contrary to the ruling of this Court in Kelley v.

Altheimer.

Kelley v. Altheimer, No. 18, 528 (8th Cir., April 12, 1967)

11

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

Civil No. 23345 (5th Cir., Dec. 29, 1966), reaffirmed

en banc (Mar. 29, 1967);

Board of Education v. Dowell, No. 8523 (10th Cir., Jan

23, 1967);

Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 661 (8th Cir., 1966)

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770

(8th Cir., 1966);

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965);

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965);

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965).

in

Appellants are entitled to attorneys’ fees.

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va.,321 F. 2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963)

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. R. Co., 186 F. 2d 473

(4th Cir. 1951).

12

ARGUMENT

i

The failure of the District Court to require the admission

of Negro pupils residing in the New Edinburg

School District to the New Edinburg School denies

Negro students equal protection of the latvs.

Until 1966-67 New Edinburg required its 55 Negro

pupils to attend the all-Negro J. E. Wallace School op

erated by the adjacent Fordyce School District. The

New Edinburg School District provided bus transporta

tion for them. White pupils were provided high school

education within the District. Prior to the beginning of

the 1966-67 school year, however, most of the Negro

pupils being transported to Fordyce expressed a choice

under the “ Guidelines” to attend school in New Edin

burg. Their choices were rejected. Moreover, defend

ants proposed to continue offering Negro pupils a choice

between the New Edinburg and Fordyce Schools. This

practice has long been condemned. As was said in Goins

v. County School Board of Grayson County, Va., 186 F.

Supp. 753 (W. D. Va. 1960), at 754:

(T)he practice of sending these plaintiffs out

side of their own county to attend school and

denying them solely on account of their race the

right to be educated within a high school in their

own county under the same conditions as white

children is something which cannot be legally de

fended.

See also, School Board of Warren County, Va. v. Kilby,

259 F. 2d 497 (4th Cir. 1960) and Corbin v. County School

Board of Pulaski County, Fa., 177 F. 2d 924 (4th Cir.

1949). Even before Brown v. Board of Education, the

13

Supreme Court invalidated analogous practices in higher

education; in 1938, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337; in 1948, Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 131;

in 1950, Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 620, and McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637.

New Edinburg Negro pupils have been assigned or

permitted to attend the J. E. Wallace School in Fordyce

solely because of their race. They have a present right

to attend the New Edinburg School.

ri

The desegregation plan approved by the District Court is

contrary to the ruling of this Court in Kelley v.

Altheimer.

In Kelley v. Altheimer, No. 18,528 (8th Cir., April

12, 1967), this Court declared that no plan of desegrega

tion could be considered adequate if its provisions were

less stringent than the H.E.W. Guidelines. In addition,

specific requirements for desegregation plans in the area

of “ choice” plans, faculty desegregation, use of facil

ities, and school equalization were laid down in the Court ’s

decree. The plan approved below does not meet these

requirements, and conflicts both with earlier decisions of

this Circuit and with the Guidelines. A comprehensive

decree equivalent to that entered in the Kelley case is,

therefore, appropriate to ensure the actual desegregation

of New Edinburg schools. Cf. United States v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, Civil No. 23345 (5th

Cir., Dec. 29, 1966), reaffirmed en banc (Mar. 29, 1967);

Board of Education v. Dowell, No. 8523 (10th Cir., Jan.

23, 1967). At a minimum, a decree must correct the

following defects of the plan:

14

A. Faculty Desegregation. The plan approved

below provides that “ vacancies on the teaching and pro

fessional staff shall be filled by employment of the best

qualified available applicant without regard to race, and

it is hereby declared to be the policy of this district to

accept and consider all applications for such professional

employment without regard to race” (R.221). Thus

approved, the plan is but a declaration of intention and

does not comport with the specific requirements of this

Court in Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 661 (8th

Cir., 1966); Kelley v. Altheimer, supra; Kemp v. Beasley,

supra; and Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton,

365 F. 2d 770 (8th Cir., 1966). These opinions stand

for the clear proposition that affirmative action must be

taken by the Board of Education to eliminate segrega

tion of the faculty. See also, Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S.

198 (1965); Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965). Appellants submit that under the

Kelley case, specific action according to a predetermined

plan which guarantees rather than speculates performance

is required to insure that faculty desegregation be

promptly achieved.

B. Freedom of Choice Plan, The plan approved

provides for mandatory “ freedom of choice” to be ex

ercised by all pupils in the New Edinburg District for

the 1967-68 school term. Thereafter, only pupils enter

ing the 1st and 7th grades shall be required to make a

choice of schools. Pupils in other grades may apply for

“ lateral transfers” which will be granted unless over

crowding results at the school chosen, in which case they

will continue at their presently attended school. How

ever, the plan does not provide for the annual choice op

portunity required in Kemp v. Beasley, supra, and in

Clark v. Board of Education, supra, at p. 668.

15

C. Inferior Facilities. Under the Guidelines and the

opinion in Kelley v. Altheimer, supra, small and inade

quate schools must be closed. The District Court, how

ever, permits such a school to he operated into the indef

inite future. Such a school would have been unconsti

tutional under the “ separate but equal” doctrine and

cannot be sustained now. Kelley v. Altheimer, supra-

See also, U.S. v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., supra;

Rogers v. Paul, supra.

D. Method of Exercising Choice. The “ Guidelines”

provide that exercise of choice may also be made by the

submission . . . of any . . . writing which sufficiently

identifies the student and indicates that he has made a

choice of schools. This provision has gained judicial

approval, along with the other Guidelines provisions, in

the Kelley and Jefferson Comity cases, supra, and is

clearly reasonable.

Moreover, in communities where the segregation

tradition is strong, individual Negro parents may over

come their fear and be bolstered in their desire to obtain

desegregation for their children if they can express their

choices as a group by petition. There was no showing-

in this case that the petition of the parents was unintelli

gible or vague. The reason for defendants’ rejection

of the petition was simply that they did not expect or

want to accept 119 Negro pupils into the white school.

This reason was insufficient to justify the District Court’s

decision to void the petition and require another choice

period.

16

hi

Appellants are entitled to attorneys’ fees

New Edinburg began a plan of pupil desegregation

pursuant to the H.E.W. Guidelines in order to continue

receiving federal assistance. Under their plan no de

segregation occurred during 1965-66. Prior to 1966-67

school term, 119 Negro pupils made choices to attend the

all-white New Edinburg School, in April of 1966. New

Edinburg waited until August 20, 1966, approximately

10 days prior to the opening of school, to advise them

that their choices would not be accepted and thereby

forced appellants into court for relief. Under the facts

of this case, set forth supra, New Edinburg’s conduct is

clearly discreditable and warrants the equitable relief,

under the circumstances, of attorneys’ fees. Bell v.

School Board of Powhatan County, Va-, 321 F. 2d 494,

500 (4th Cir. 1963); Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. R. Co.,

186 F. 2d 473, 481 (4th Cir. 1951).

17

CONCLUSION

Appellants respectfully pray that this court reverse

the District Court and remand the case to the District

Court for the entry of an order requiring appellees to

grant them the relief promised by the Guidelines of the

Office of Education, Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare, and for other appropriate relief.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W. W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

J ack G reenberg

M ich ael M eltsner

Suite 2030 — 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

18

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, John W. Walker, hereby certify that I have served

a copy of the foregoing Brief of Appellants upon the

attorney for appellees, by personally handing it to said

attorney, Robert V. Light, Esq., at his office at 1100

Boyle Building, Little Rock, Arkansas, this 17th day of

July, 1967.