Newark Coalition for Low Income Housing v. Newark Redevelopment Housing Authority Memorandum of Law

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newark Coalition for Low Income Housing v. Newark Redevelopment Housing Authority Memorandum of Law, 1989. 7cc0658f-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/680487ab-f33e-4e56-9fd3-f779992922c0/newark-coalition-for-low-income-housing-v-newark-redevelopment-housing-authority-memorandum-of-law. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

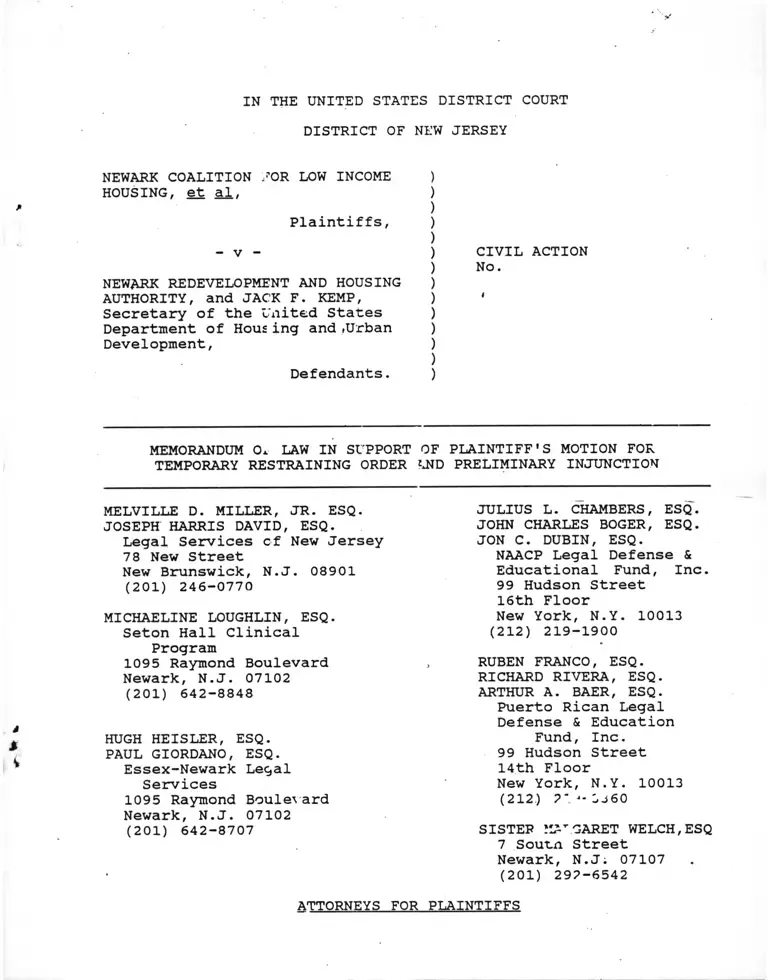

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY

NEWARK COALITION FOR LOW INCOME )

HOUSING, et al, )

)Plaintiffs, )

)- v - ) CIVIL ACTION

) No.

NEWARK REDEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING )

AUTHORITY, and JACK F. KEMP, ) '

Secretary of the United States )

Department of Hous ing and .Urban )

Development, )

)Defendants. )

MEMORANDUM 0. LAW IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF'S MOTION FOR

TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER *LND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

MELVILLE D. MILLER, JR. ESQ.

JOSEPH HARRIS DAVID, ESQ.

Legal Services cf New Jersey

78 New Street

New Brunswick, N.J. 08901

(201) 246-0770

MICHAELINE LOUGHLIN, ESQ.

Seton Hall Clinical

Program

1095 Raymond Boulevard

Newark, N.J. 07102

(201) 642-8848

HUGH HEISLER, ESQ.

PAUL GIORDANO, ESQ.

Essex-Newark Legal

Services

1095 Raymond Boulevard

Newark, N.J. 07102

(201) 642-8707

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS, ESQ.

JOHN CHARLES BOGER, ESQ.

JON C. DUBIN, ESQ.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RUBEN FRANCO, ESQ.

RICHARD RIVERA, ESQ.

ARTHUR A. BAER, ESQ.

Puerto Rican Legal

Defense & Education

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

14th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 2* ■*- 3 J 6 0

SISTER MAUCARET WELCH,ESQ

7 Soutn Street

Newark, N.J; 07107

(201) 292-6542

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ..................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ............................. ..... 2

ARGUMENT .............................'..................... 3.1

s

I. THIS COURT SHOULD ENTER A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

PROHIBITING : (i) THE DEMOLITIONS OF COLUMBUS

HOMES AND KRETCHMER; (ii) ALL DEMOLITION-RELATED

ACTIVITY; AND (iii) THE FAILURE TO RENT VACANT

HABITABLE NHA APARTMENT UNITS, DURING THE PENDENCY

OF TFT? ACTION ....................................... 11

II. THE NHA HAS NOT DEMONSTRATED, NOR COULD HUD PROPERLY

FIND, THAT THE COLUMBUS AND KRETCHMER BUILDINGS

SLATED FOR DEMOLITION ARE OBSOLETE, INFEASIBLE OF

MODIFICATION TO RETURN THEM TO USEFUL LIFE OR IN

THE CASE OF KRETCHMER, NECESSARY TO DEMOLISH TO

ASSURE THE USEFUL LIFE OF THE REMAINDER OF THE

PROJECT IN VIOLATION OF 42 U.S.C. § 1437p(a)......... 21

1. COLUMBUS HOMES .................................. 23

2. KRETCHMER HOMES'................................. 31

III. THE NHA HAS FAILED TO MEET THE REQUIREMENT OF A

ONE-FOR-ONE REPLACEMENT PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED

DEMOLITIONS, IN VIOLATION OF 42 U.S.C.§ 1437 p(b)

AND HUD REGULATIONS................................... 39

A. THE COLUMBUS HOMES REPLACEMENT PLAN VIOLATES

THE 1987 ACT AND REGULATIONS THEREUNDER......... 39

1. The Plan Fails To Identify Or

Assess The Suitability Of The

Proposed Sites For Replacement

Housing In Violation Of HUD

Regulations ................................ 4 0

2. The Plan Does Not Include A

Credible Or Meaningful Schedule For

Its Completion Within Six Years In

Violation Of 42 U.f C.§ 1437

P(b) (3) (D)............................... . . • 42

i

PAGE

3. The Secretary's Commitment of Funds for

The Plan "Subject To Appropriations",

While At The Same Time Recommending To

Congress No Appropriations To Cover His

Commitment, Combined With The Commitment's

Lack Of Detail, Renders It Legally *

Inadequate Under 42 U.S.C. § 1437p(b)..... . 48

4. The Plan Fails To Provide Access For

Handicapped Tenants In The Replacement

Units In Violation of

HUD Regulations. .................. 51

5. The NHA Did Not Properly Consult With

Tenants In Preparation Of The Plan In

Violation Of 42 U.S.C.§

1437 p(b) (1) 51

6. The Plan Fails To Provide For

Appropriate Relocation of Tenants

In Violation of 42 U.S.C.§ 1437

p(b) (3)[F]&[G] And HUD Regulations ____ .... 53

7. The Plan Fails To Ensure That The

Same Number Of Individuals and

Families Will Be Provided Housing

In Violation of 42 U.S.C.§ 1437'

P(b) (3) [E] 54

8. The Plan Fails To Provide

Assurances That The Replacement

Housing Will Be Affordable In

Violation of 42 U.S.C.§ 1437p

(b)(3) ............................ ......... 55

9. The Plan Is So Lacking In Detail That

It Is Neither Credible Nor Realistic ....... 56

B. THE ABSENCE OF A REPLACEMENT PLAN FOR UNITS

TO BE DEMOLISHED AT KRETCHMER HOMES VIOLATES %

42 U.S.C. 5 1437p fb̂ ■ fd) ... ....... ........... 57

4

*1. The 1987 HCDA's Plain Language

Requires Its Application To All

Demo'itxon Activity After February

5, 1988 And It Bars the NHA's

Demolition of Kretchmer Without A

Replacement Plan ............................ 57

l i

PAGE

#

f

2. The 1987 HCDA's Plain Language

Requires Its Application To All

Demolition Activity After February

5, 1988 And' It Prohibits The

S e c r e t a r y From F u r n i s h i n g

Assistance For The Demolition Of

Kretchmer Without A Replacement

Plan ....................................... 61

3. Even Under HUD Regulations In

Effect In 1985, HUD's Approval

Of The N H A 's Application To

Demolish Kretchmer Without Pre

paration Of A Replacement Plan Was

Unlawful ................................... 63

IV. ALL NHA DEMOLITION-RELATED ACTIVITY,

VIOLATES THE HOUSING COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

ACT OF 1987 AND MUST 3E ENJOINED, AS MUST ITS

CONTINUING REFUSAL TO RENT VACANT UNITS . . , ,..... 65

V. THE PROPOSED DEMOLITIONS ARE BARRED BY THE

SECRETARY'S FAILURES TO COMPLY WITH THE

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT, 42 U.S.C.

§ 4231 et seq...... ......................... . 67

VI. THE NHA'S PROPOSED DEMOLITIONS AND REFUSAL

TO RENT VACANT UNITS HAVE HAD AND WILL HAVE

DISPARATE RACIAL EFFECTS IN VIOLATION OF

TITLE VIII OF THE FAIR HOUSING ACT OF 1968,

42 U.S.C.§ 3601 et sea. AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964, 42 U.S.C.§ 2000d ................... 71

VII. THE SECRETARY'S FAILURE TO PROPERLY CONSIDER

OR AVERT THE RACIAL IMPACT OF THE PROPOSED

DEMOLITIONS IS VIOLATIVE OF HIS AFFIRMATIVE

DUTY TO FURTHER THE PURPOSES OF TITLE VIII OF

THE FAIR HOUSING ACT, 42 U.S.C. §3608 (e)(5)..... 82

VIII. THE NHA'S PROPOSED DEMOLITION OF KRETCHMER

AND COLUMBUS HOMES AND BLANKET REFUSAL TO

RENT VACANT UNITS VIOLATE THE NEW JERSEY

CONSTITUTION ..................................... 84

A. Article I, Paragraphs 1 and 2, of

the New Jersey Constitution

Embodies a Fundamental Right To

Housing That Precludes NHA's Course

Course Of Conduct .......................... 84

in

PAGE

B. Article I, Paragraphs 1 and 2,

Requires That NHA Utilize Scarce

Housing Resources in a Manner

Consistent with The General

Welfare .................................... 87

CONCLUSION ........ .......... .......... .............. . . • • • 92 *

*

IV

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This is a class action brought pursuant to the United States Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. 1437 et sea.; the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. 702 et sea.;

Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. 3601 et sea^; Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d; the National Environmental Policy

Act, 42 U.S.C. 4321 et sea.; and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution, as well as state constitutional and statutory

provisions under this Court's prerogative to exercise pendent jurisdiction.

Plaintiffs seek injunctive and declaratory relief against the Newark Housing

Authority (NHA), the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD), and the Secretary of HUD, halting the destruction, demolition,

disposition and mismanagement of public housing in derogation of law.

This brief is in support of plaintiffs' motion for a temporary restraining

order and preliminary injunction, pursuant to Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure.1 Plaintiffs seek to enjoin defendants from demolishing any of

the nearly 2000 public housing apartment units slated for imminent destruction

at the Columbus Homes and Kretchmer Homes projects; taking any action in

preparation or in anticipation of such demolition or disposition activities at

Columbus and Kretchmer, and failing to rent vacant habitable units. The

preliminary relief plaintiffs seek would prevent the irretrievable loss of

scarce low income housing and ongoing and future irreparable hardships, while

simply requiring defendants to comply with their ctatutorily imposed duties.

1 Since plaintiffs are indigents, this Court should waive any requirement

of a bond on this motion. See Bass v. Richardson. 338 F Supp. 478, 490

(S.D.N.Y. 1971); See also Powelton Civic Home Ass'n v . HUD. 284 F. Supp. 809,

840 (E.D. Pa. 1968)

1

In July of 1988 many of plaintiffs, together with a number of

organizations, filed a complaint in the Superior Court of New Jersey, Essex

County, against the NHA. This state court action sought relief barring the NHA

from taking further steps toward demolition at any of its projects, compelling

the NHA to rent vacant habitable units, and ordering the NHA to properly manage

its projects. The action was based on both state and federal law claims.

Subsequent to the filing of the state complaint, the NHA submitted and HUD

approved an application for the demolition of Columbus Homes, consisting of

1,506 housing units. This development, together with demolition preparations

and activities at Kretchmer Homes and other NHA projects, violated, inter al ia.

recent amendments to the United States Housing Act. Because of HUD's approval

of and acquiescence in these activities, and because the actions involve very

substantial violations of federal law, plaintiffs are filing this United States

District Court action against HUD and its Secretary, in addition to the NHA.

The prior state court action is being vo1untarily dismissed without prejudice

on plaintiffs' motion, with the consent of defendant NHA.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Desperate Affordable Housing and Homelessness Crises in Newark

Since 1985, the NHA, with HUD's approval and acquiescence, has embarked

on the most massive demolition program in the history of public housing,

involving the attempted destruction of over 5000 apartment units. Considered in

isolation, the elimination of so many units without adequate replacement is

profoundly disturbing; considered against the backdrop of the Newark area's

deepening housing and homelessness crisis, the magnitude of this loss is

staggei ing.

The numbers alone are shocking. Newark, a city of 316,240 (United States

2

department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book 1988.

582 (1988)), is estimated to have a homeless population of over 16,000, a

-lomolessness rate among the highest of any major city in the nation. The NHA's

public housing waiting list is currently estimated at over 7,000 families, and

was as high as 13,000 in 1986. See Affidavit of Victor DeLuca, dated March 10,

1989 at par. 9, Exh.2.2

The plaintiffs have few, if any, alternatives to public housing, given

Newark's critical shortage of affordable housing of even poor quality. Nearly

19,000 low and very low-income tenants are paying unaffordable rents. Newark

lousing Assistance Plan (HAP) at 7-11, Exh. 12. The city possesses 14,055

substandard occupied units, Id. at 7. These conditions qualify Newark's

housing stock as or.e of the worst in the nation. See Burchell, Housing and

Economic Change in Newark. Report Prepared for the New Jersey Department of the

Public Advocate, at 6 (1986), Exh. 16.

In addition to these grim economic realities the plaintiffs'

opportunities to f-nd adequate housing in the county and city are further

restricted by continuing racial discrimination and residential segregation. See

general 1y National Urban League, State of Black America 1989. (January 1989),

at 77-106 (citing studies of continuing residential segregation in several

cities including Newark). The city's HAP specifically found "a critical

shortage of housing for low/moderate income and minority groups11 and

"discrimination in ownership, rental, and financing of housing." HAP at 3, Exh.

12. (emphasis added).

Background of NHA's Demolition Program

2. 1986 HUD Audit of NHA, at Overview P. 2, Exh. 14.

3

The grave implications of NHA's current demolition activity should be

assessed by placing it within its proper context: a massive demolition program,

embarked up on by the NHA in 1985, the largest in the history of the nation's

public housing program. Notwithstanding that nearly half of its 13,000 public

housing units were in mid-rise and high-rise buildings, during the early 1980's

the NHA decided to abandon the use of its high-rises as family dwellings. This

theoretical position was as breathtaking in its sweep as it was unsupported by

the experiences of a number of ether public housing authorities, which had made

high-rises work for families.

In 1985 the NHA adopted as its guide the Public Housing Master Plan.

Newark. New Jersey (December 1984) (hereinafter Master Plan), Exh. 9. The 1984

Master Plan acknowledged that the city's public housing vacancy rate was the

highest of any major housing authority in the country and that its level of

deterioration was among the most serious in the nation. Id. at 12.

In the Master Plan, the NHA acted on its conclusion that high-rise

buildings were inappropriate, by announcing a five year effort to demolish the

city's family high-rise projects. Id. at 1-2. In fact, the NHA had begun to

abandon the high-rises well before the formal announcement in the Master Plan,

allowing large numbers of units to remain vacant and deteriorate. The NHA's

desire to assist the gentrification of Newark, an upgrading of property values

which forces poor residents to move from the city, appears a prominent motive

behind the Master Plan and the overall demolition program. The NHA observed that

the city could not be expected to devote "a major share of its meager resources"

to a public housing system (and its low-income population) already overburdening

city services. Master Plan at 32.

The NHA has continued to adhere to this philosophy of demolition. In June

4

1987 the NHA filed a "Comprehensive Modernization Plan," announcing that "five

family high-rise projects comprised of thirty-nine buildings should be

demolished and replaced by townhouses or sold to developers." 1987 Comprehensive

Modernization Plan at 1, Exh. 7. In March 1988 a seco-id Comprehensive

Modernization Plan proposed an even more sweeping course: the elimination of

over 5,000 units out of-an original 13,133 units, with only minimal replacement.

1988 Comprehensive Modernization Plan at 2-6, Exh. 18. To date, the NHA has

actually demolished 816 units at the Scudder Homes site, without creating a

single new unit (ground has recently been broken in June 1988 for a mere 101

units at the Scudder Homes site).

Current Demo!ition. Activity

The planned demolitions of Kretchmer and Columbus Homes would withdraw

nearly 2,000 low-incume units from a city already facing this deepening housing

and homelessness crisis. The Kretchmer projects, where 372 units are slated for

imminent destruction, are conveniently located in a quiet tree-lined residential

area, bordering the City of Elizabeth, within easy walking distance of grocery

and drug stores, a community health center, churches, and a park. Affidavit of

Vic DeLuca, par. 15 ,Exh. 2. Columbus Homes, where over 1500 units are to be

destroyed, has ready access to public transportation, including bus and railroad

lines an important feature for low-income families unable to purchase or

maintain automobiles. A major city park, shopping center, clinic, and

neighborhood schools are all located within walking distance. IcL at par. 17.

The area adjacent to the Columbus site is experiencing gentrification,

and substantial private developer activity and interest. See 0KM Columbus Homes

Rep't at 45, Exh. 1. Both Columbus and Kretchmer provide a more socially and

economically integrated environment than the majority of Newark's public

5

housing, situated in the city's economically and racially impacted Central Ward.

The area east and west of the Columbus project, for example, abuts the

Colonnade, a private high-rise apartment complex. See NHA Columbus Demolition

Application, at 6, Exh. 3. The elevated Interstate Route 280 and Lackawanna

railroad tracks pass by the project on its southerly side, creating natural

barriers between the city's gentrifying North Ward and its racially impacted

Central Ward. IcL

Despite the city's critical shortage of safe, sanitary, and affordable

housing and the highly desirable location of both Kretchmer and Columbus Homes,

the NHA has slated both projects for demolition. In September 1985 the NHA

obtained HUD approval for the demolition of three Kretchmer buildings. Exh. 6.

The NHA has stated that it will not replace them.

In October 1988 HUD approved the demolition oi? over 1500 Columbus Homes

units. HUD approval decision, Exh. 4. The required replacement plan for these

targeted units is woefully inadequate. Moreover, the NHA intends to sell the

Calumbus site to a private developer for market-rate housing, rather than retain

tiiis increasingly valuable land for use in housing the poor, as the NHA's

mssion would appear to require.

Racial Impact of Planned Demolitions

The demolitions will have a devastating impact on racial minorities0 in

a variety of ways. The supply of scarce low-income housing resources will be

reduced sharply for thousands of desperately needy overwhelmingly minority

3

The term "racial minorities"

Hispanic individuals.

as used herein, shall refer to Black or

6

homeless and inadequately housed people.** The planned demolitions of Columbus

and Kretchmer a^ne would remove nearly 2000 units from housing sites located

in places .advantageous to low-income minority households. Finally, these plans

will' increase segregation in the city by relocating displaced tenants and

placing new replacement public housing in the racially and economically impacted

Central Ward, and by removing 2000 units from more integrated areas of the

city.^ Nonetheless, neither HUD's demolition approval determinations, nor any * 5

̂ Members of racial minority groups comprise a disproportionate share of

the homeless and inadequately housed persons in Essex County. Those eligible

to apply for NHA-operated housing include not only residents of Newark but also

residents from other towns in Essex County, including Belleville, Bloomfield,

Irvington, and Nutley. In 1980, Blacks comprised 44.36% of this group of cities

and towns, and Latinos comprised 13.74%. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of

the Census, Countv and City Data Book 1983. 740-50 (1983). In comparison, the

homeless population of Essex County is overwhelmingly Black. Estimates place

the percentage of county Black homeless at 95%. Affidavit of Eileen Finan,

4, Exh. 8. Hispanics also are dramatically overrepresented among the county's

poor. In 1980, 18.4% of the population of Essex County living below the poverty

line was Hispanic even though Hispanics represented only 9.08% of the county

population. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, General Social and

Economic Characteristics: 1980 Census of the Population. Chap. C, pt. 32 (July

1982). In view of the economic realities indicated by these bleak statistics,

the withdrawal of low-income housing units in a scarce nrarket has had and will

continue to have an adverse impact on both Blacks and Hispanics.

5

Unlike the majority of the city's public housing located in the racially

and economically impacted traditional Central Ward, both Kretchmer and Columbus

are located in areas with more integrated residential patterns. Kretchmer is

located in the East Ward, which borders Elizabeth, a city over 75% white. County

and City Data Book 1983 at 740. Although public housing tenants in the East Ward

are predominantly minorities, several hundred tenants, amounting to nearly one

third of the area's public housing tenants, are white. See Exh. 13, map and NHA

demographics. Although as a result of redistricting, Columbus is technically

now part of the new Central Ward, the area where Columbus is located is more

racially and economically diverse than the traditional Central Ward. Although

the immediate area is predominately minority, it does not contain much public

housing other than Columbus. Moreover, it borders on areas that are not

predominantly minority.

Over 70% of the units provided for the relocation of plaintiffs whose units

are to be demolished are in the Central Ward. HAP at Exh. B, Exh. 12. A similar

percentage of the acreage listed as available as sites for new replacement

housing units are also there. Id at A, Exh. 12. The comparative numbers of

7

of the documents presented in the NHA's demolition applications, as much as

mention, much less thoughtfully weigh, these impacts, nor do they contain

analysis of alternative courses of action which would have less detrimental

impact on housing opportunities for racial minorities.

Warehousing of Vacant Units

The NHA's 1984 Master Plan acknowledged that the city's public housing vacancy

rate was the highest of any major housing authority in the country. Master Plan

at 32, Exh 9. By September, 1987, the NHA's vacancy rate had increased by 945

percent over the past decade. Complaint, at par. 62 (e). Currently, nearly 40

percent of the NHA's entire housing stock lies vacant.®

HUD is well aware of the NHA's acute vacancy problem, but has failed to

take effective corrective measures. In a 1986 audit of the NHA, HUD found there

Wpro 5285 vacahcies in NHA housing, and noted that 1200 of the vacancies were

at family low-rises or elderly high-rises. The HUD officer stated:

Judging- from the volume of inquiries this office receives from

applicants, it would appear that all habitable units could be

filled.

Black and Whites in these census tracts comprising the Central Ward, in which

the majority of the city's low-income housing projects are already clustered,

follow:

Census tract 31

39

63

65

66

5421 Blacks 12 Whites

2595 B1acks 5 Whites

4499 Blacks 14 Whites

1972 Blacks 115 Whites

3748 Blacks 85 Whites

Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, 1980 Census of Population and

Housing. Census Tracts Newark. N.J, Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area No.

PHC*)-2-261 (July 1983) at 96-98, Exh. 49.

® Under HUD regulations, a vacancy rate in excess of 3% (occupancy rate

below 97%) is considered abnormal and requires the housing authority to prepare

a five-year comprehensive occupancy plan demonstrating how it will return to full

occupancy. 24 C.F.R. 990.118.

8

HUD 1986 audit at Finding #3, Exh. 14. Eleven months later, NHA director Milton

Buck responded that 2600 units were deliberately held vacant due to plans for

their demolition, 1100 units are in projects undergoing modernization, and thus

less than 1400 units were vacant without justification. Letter from Milton hiick

to Walter J. Johnson, August 4, 1987, Exh. 15. (Emphasis added). HUD, to date,

has not taken significant corrective measures in response to the NHA's startling

revelation.

Mismanagement of Newark's Public Housing

Newark's public housing system has been beset by a long and unbroken

history of inept management and maintenance. Vacancies have soared; essential

repairs and security have been neglected; construction and modernization has

lagged or gone uncompleted; and modernization funds have been lost for timely

failure to commit.

The NHA's construction record has been nothing short of abysmal. In 1974

and 1978 the NHA received funding for the construction of approximately 516

units of new housing; 372 units eventually became available for occupancy in

1987 and 1988, ten years after HUD first approved and reserved funding for them.

Some of these units still remain unoccupied. During this time HUD recaptured

80 units due to delay, and the NHA had to abandon completely 47 units due to

inappropriate site selection. The NHA's record of modernization is equally

bleak. In 1983, for example, after warnings from HUD, $5,000,000 were

recaptured "due to the NHA's failure to make more than minimal use of available

modernization funds." HUD 1984 Audit, o. 32, Exh. 21.

Despite HUD's ongoing awareness- of the NHA's history of management and

maintenance problems, HUD has failed to take appropriate corrective measures.

9

In 1979 HUD designated the NHA as an operationally troubled authority. In the

1980's HUD conducted three audits of the NHA, all sharply critical of the

authority on a number of. grounds, ranging from its soaring vacancy rate to its

failure to timely complete modernization projects. This history demonstrates

that HUD was acutely aware of the NHA's woeful construction, modernization,

management and maintenance track records; nevertheless, it approved the Columbus

replacement plan, an endeavor of unprecedented scope, without the slightest

analysis or discussion of the NHA's ability to perform any aspect of this

proposal.

Renovation Alternatives to Demolition

Plaintiffs' nationally recognized experts on public housing management and

rehabilitation, OKM Associates, Inc. (hereinafter OKM) and On-Site Insight, Inc.

(hereinafter 0511), have conducted on-site inspections of Kretchmer and Columbus

Homes., and have determined that the rehabilitation of both Columbus and *

The 1982 HUD audit criticized the NHA for its failure to comply with

prescribed time frames for the completion of modernization projects. The 1984

HUD audit again underscored the authority's troubling "[l]ack of urgency in

developing an overall planning strategy and timetable for expending available

modernization funds totaling $68,641,239.11 1984 Audit, at 32, Exh. 21. The 1986

HUD audit found that the NHA still had $55 million in unobligated modernization

funds and noted that the NHA's failure to submit implementation plans "again

calls into question the NHA's modernization capability." HUD 1986 Audit, finding

#5, Exh. 14. This same audit also found the NHA to have the highest vacancy rate

of any major public housing authority in the country, despite a more than ample

number of applicants to fill all habitable units. See HUD 1986 audit, finding

#3, Exh. 14. In February 1988, HUD yet again noted the NHA's poor planning,

implementation, and progress, despite frequent HUD warnings regarding impending

deadlines. Letter from Johnson to Clark dated February 17, 1988. Exh. 34.

HUD's only response in the face of such consistent ineptitude has been to

require the NHA to enter a "Memorandum of Understanding." The NHA's failure to

fulfill its legal obligations, and HUD's acquiescence in that failure, have taken

a heavy toll upon thousands of inadequately housed and homeless individuals in

the city of Newark, who must continue to live without safe, sanitary, and

affordable housing, and without the benefits of residence in a socially

integrated environment.

10

Kretchmer is feasible from a structural and design perspective. Exh 1, Aff. of

Dr. Thomas Nutt-Powell at pa^. 13. They also identified several renovation

alternatives to the proposed demolitions at both Columbus and Kretchmer. Id.

at OKM and OSI Kretchmer and Columbus Homes Reports. Plaintiffs' experts have

provided substantial documentation in support of these alternatives to

demolition; their extensive analyses are enclosed herein. Id. In addition,

plaintiffs' experts have reviewed the NHA's meager submissions to HUD .and have

found no competent documentation supporting the defendants' conclusion that

renovation cannot be feasibly pursued. Id.

ARGUMENT

POINT I

THIS COURT SHOULD ENTER A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

PROHIBITING: p) THE DEMOLITION OF COLUMBUS HOMES AND

KRETCHMER; (ii) ALL DEMOLITION-RELATED ACTIVITY AND

(iii) THE FAILURE TO RENT VACANT HABITABLE NHA APARTMENT

UNITS, DURING THE PENDENCY OF THIS ACTION

The plaintiffs are entitled to a preliminary injunction pursuant to Fed.

R. Civ. 65. A grant of such injunctive rel ef is required where the moving

party demonstrates that "irreparable injury will occur if relief is not granted

to maintain the status quo until a final adjudication on the merits can be made

and that there is a reasonable probability of eventual success on the merits."

Continental Group. Inc, v. Amoco Chem. Corp.. 614 F.2d 351, 356 (3rd Cir. 1980).

In addition, the court must weigh the possibility of harm to other interested

persons from the grant or denial of injunctive relief, as well as considerations

of public interest. Id. at 356. These four factors structure the court's

inquiry; however, no single aspect is dispositive. A proper judgmp..t entails

a "delicate balancing of all the elements." See Constructors Asr.'n of Western

Pennsylvania v. Kreps. 573 F.2d 811, 815 (3rd Cir. 1978).

11

As demonstrated below, an injunction is plainly appropriate, based on each

of the four factors to be considered. Regarding the first factor, plaintiff and

their classes are suffering continuing irreparable harm caused by homelessness

or inadequate housing, for which a monetary award at some future date cannot

afford adequate relief. Moreover, they are irreparably harmed if the threatened

units are in fact demolished, because an already scarce housing supply will be

drastically reduced. These units would then no longer be available for

renovation, as plaintiffs contend is required by law, nor i.> there a likelihood,

let alone a certainty, that they can be replaced.

Second, the plaintiffs have a strong probability of eventual success on

their numerous claims, as set forth in detail in the following points of this

brief.®

Third, defendants constitute the public authorities charged by law wit.n

the responsibility of preserving, maintaining, developing and expanding the

supply of decent and affordable low-income housing in Newark, and with

furthering housing opportunities for racial minorities. They cannot be viewed

as harmed by virtue of an order requiring them to fulfill these legally required

duties.

Finally, the public interest will be far better served by the maintenance

and expansion of scarce affordable housing, rather than by its demolition,

misuse, reduction, and increased segregation in a city and county with critical

o

Plaintiffs' legal claims are extremely compel 1ing, as will be demonstrated.

But even if this were not the case, where as here the remaining three factors

decidedly favor the moving party, that party need not demonstrate as strong a

likelihood of success on the merits as would otherwise be required. The public

interest and balance of hardship tips decidedly in plaintiffs' favor and mandates

the issuance of a preliminary injunction. Constructors Association, Supra, at

815. See also Jackson Dairy. Inc, v. H.P. Hood & Sons. Inc.. 596 F.2d 70, 72

(2d Cir. 1979).

12

low-income housing needs.

For plaintiffs and their classes--the present and prospective applicants

and the current tenants alike--the low-income public housing projects operated

by the NHA constitute the major source of affordable units in the City of

Newark. The lives of Ernestine Betts, Aida Guzman, Nereida Varela and Elaine

Williams graphically depict the irreparable harm suffered by these named

plaintiffs, and by the classes of present and -prospective applicants they

represent.

Plaintiff Ernestine Betts has been unable to find a decent affordable

apartment, although she has been seeking suitable housing for years. Betts and

her two daughters have been forced to leave at least eight different apartments

due to unsafe and unsanitary conditions. At one dilapidated apartment, the

family was without electricity and water; in another, the kitchen floor

collapsed; others were infested with rodents.

Betts and her family currenfy live in a small overcrowded basement

apartment which has an unbearable noxious odor due to a sewage backup in the

nearby cellar. Betts Aff. dated March 22, 1989, par. 6-10, Exh. 50. Because

of this she has given her landlady notice, and her landlady told her she must

leave in April. Id. at par. 10. Her seventeen-year-old daughter, while

attending remedial high school classes, has become discouraged, no longer

wishing to continue her education. Id. at par. 14, 15.

Plaintiff Aida Guzman has been on the waiting list for public housing

since 1979. Guzman Aff. at par. 9, Exh. 7. She presently resides in an severely

overcrowded one-^oom apartment with her three children. Id at par. 6. Because

she and her J.ildren suffer from severe bronchial asthma, her doctor has

certified that the family is in need of a larger apartment with greater air

13

circulation for medical reasons. Id. at par. 6 and Attachment A.

Plaintiff Varela lives in substandard private housing. There is

frequently no heat in her apartment, and she and her children often get sick

from the cold. Varela affidavit at par. 13, Exh. 7. There are also leaks in

the living room when it rains; the lock to one of the doors downstairs is

broken; there are large cracks in the ceiling and wall of the children's bedroom

soaking the bedroom with rain; the radiator in the kitchen leaks, spilling water

over the floor when it is turned on; the winter wind blows through the bathroom

ceiling window; the faucet in the bathtub is defective so that children may get

burned if they turn it on; and there has been a broken window since the summer.

Id. at par. 9. For approximately three to four months there were big rats in

her apartment, but since she got a cat the problem has ended. IcL Because of

the stress of her living conditions and poverty, Varela's health is suffering.

Exh. id. at par. 12.

Plaintiff Elaine Williams has resided in the Lincoln Motel in East Orange,

New Jersey, since June, 1987. Affidavit of E. Williams at par. 1, Exh. 7. She

would like to leave the motel, which has roaches and mice, and which is without

cooking facilities. Id. at par. 14. Williams receives food vouchers that are

supposed to last two weeks, but they only buy five or six days worth of food for

her family of three. IdL at par. 10.

Approximately 450 to 500 families live in welfare motels in Essex County.

DeLuca Affidavit at par. 9, Exh. 2. Families living in welfare motels are

incapable of providing nutritious meals for their children due to the fact that

they have no refrigeration or cooking facilities IcL at par. 11. These same

families spend an inordinate amount of thei. welfare payments and rood stamp

allocations to buy smaller quantities of food from motel restaurants or

14

convenience shops, deceasing even further the small amount they have to spend

on other necessary items, such as clothing and transportation. kL Without

cooking facilities, the type of food consumed is limited, and nutrition suffers,

since almost all those living in welfare motels are families with children. IcL

Inadequate nutrition can have long-term health consequences. Id.

Persons who have no shelter often are depressed and anxious about their

future. Id. at par. 12. They typically feel a sense of hopelessness,

disorientation and humiliation at their situation. Id. Frequently homeless

parents suffer intense stress from uncertainty about meeting the daily needs of

their children. Id. If 2,000 units of NHA public housing are destroyed without

realistic replacement housing and if 400 of NHA housing units are permitted to

continue to stand vacant without justification, these homeless and inadequately

housed plaintiffs will suffer irreparable injury for wf.ch future monetary

damages will not afford sufficient relief. Even a few details from the

plaintiffs' daily round of hardships dramatize the extent to which homelessness

and inadequate housing jeopardize and impair the mental health and physical

well-being of adults and children, the integrity of the family, and the

education and future opportunities of children. See general 1y Newark Pre-School

Council Association for Children of New Jersey, Not Enough jo. Live On, in Report

of the Governor's Task Force on the Home!ess 33-39 (1985); National Social

Science and Law Project, Jhe Cost of an Adequate Living Standard j_n N.J.: An

Update, in Report of tjie Governor's Task Force on the Homeless 40-43 (1985).

As the New Jersey Appellate Division aptly stated in commenting on Essex

County's and Newark's homelessness crisis:

There appears to be no governmentaliy provided emergency group shelters

in Newark or elsewhere in Essex County, and t^e few privately maintained

ones are seriously over-crowded, overstressed, and unable to respond to

the overwhelming need. In short, the record in this case describes a

15

catalog of human suffering, illness, disease, degradation, humiliation,

and despair which shakes the foundations of a common belief in a

compassionate, moral, just, and decent society.

Rodgers v. Gibson. 218 N.J. Super 452, 457 (App. Div. 1987).

When the hazards of the plaintiffs' daily living conditions are considered

in conjunction with their physical and psychological toll, it is small wonder

that other courts have found that critical shortage of housing impose

irreparable injury on low-income families. See Sworob v, Harris. 451 F. Supp.

96 (E.D. Pa. 1978), aff'd mem., 578 F.2d 1376 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied. 439 li.S.

1089 (1979); Resident Advisory Bd.v.Rizzo. 429 F. Supp. 222, "226 (E.D. Pa.

1977; (in light of the urgent need for decent low-income housing, "[fjurther

delay in the construction of these 120 townhouses will undoubtedly injure the

plaintiffs, even though everyone recognizes that the construction of 120 houses

does not come close to satisfying the needs of approximately 14,000 families on

the waiting list for housing."), modified. 564 F.2d 126 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied

sub nom. Whitman Area Improvement Council v. Resident Advisory Bd.. 435 U.S.

908 (1978). Accord North Avondale Neighborhood Ass'n v. Cincinnati Metro.

Housing Authority, 464 F.2d 486, 488 (6th Cir. 1972) (per curiam) (city's

serious housing shortage imposes substantial harm).

Courts have found plaintiffs suffered irreparable harm in several cases

which are factually similar to the present case. In Tenants for Justice v.

Hills, 413 F. Supp. 389 (E.D. Penn. 1975), the court issued a preliminary

injunction enjoining evictions of tenants after HUD's sale of low-income housing

property. HUD sold the property to a private developer without imposing any

condition on the rent charged the low-and moderate-income tenants who lived at

the project. After repeated increases in rent, the tenants staged a rent

strike, and the new owner subsequently threatened to evict striking tenants who

16

did not pay the new rent in full.

The court found, inter alia. that tenants were deprived of due process

rights when HUD disposed of the property without notice or hearing; that HUD

violated its own regulations by failing to consider alternative methods of

disposition which would have preserved the property as low-income housing; and

that HUD violated its own regulations and the Environmental Protection Act by

failing to prepare and process an environmental impact statement. The court

found that unless the evictions were stayed, "plaintiffs will clearly suffer

great and irreparable harm. While this would probably be true with respect to

ariv public housing pro.iect. it is particularly clear in the present case, in

view of the demonstrated absence of available housing for low and moderate

income families in the ... area." Id. at 393 (emphasis added).

In Cole v. Lvnn. 389 F. Supp. 99 (D.D.C. 1975), feints of a housing

project sued HUD when it decided to demolish the project without holding a

hearing for tenants and without articulating rational reasons for its decision

to demolish. The court ordered a halt to all demolition, as well as required

HUD to take affirmative steps to restore tenants to their prior status before

demolition was begun, by directing HUD to begin restoration work, replace

appliances, and provide security, among other things. Id. at 105-106.

In Kent Farm Co. v. Hills, 417 F. Supp. 297 (D.D.C. 1976;, the court

granted a preliminary injunction to the owner of a low- and moderate-income

housing project to enjoin foreclosure proceedings. The court required HUD to

articulate rational factors motivating its decision to foreclose, and to

consider national housing policy in determining whether foreclosure was

appropri ate.

In TOOR v. U.S. Dept, of HUD. 406 F. Supp. 1024 (N.D.Cal. 1973), plaintiff

17

residents of a redevelopment area and an organization sought an injunction

prohibiting a redevelopment agency from relocating them out of the redevelopment

area and prohibiting HUD from further funding redevelopment of the area until

the agency had observed plaintiffs' rights. The court granted a preliminary

injunction prohibiting relocation of plaintiffs and demolition until the

defendant redevelopment agency submitted a relocation plan that was in

accordance with law. Id. at 1041-42. The injunction subsequently was dissolved

by consent, id. at 1045, and a similar order reissued, jji at 1051. Plaintiffs'

subsequent motion for a preliminary injunction was deemed unnecessary due to a

similar injunction in place at the time in another case. TcL at 1053-55.

Moreover, even in the absence of this concrete factual showing of

irreparable harm, defendants' violations of federal anti-discrimination laws,

presumptively constitute such injury. See Gresham v. Windrush Partners. 730

F.2d 1417, 1423 (11th Cir.) (Title VUI), cert, denied sub nom. Windrush

Partners. Ltd, v. Metro Fair Housing Servs.. 469 U.S. 882 (1984); Bolthouse v.

Continental Wingate Co.. Inc.. 656 F Supp. 620, 628 (W.D. Mich. 1987)

(Rehabilitation Act).

The current tenants of the NHA-operated projects are likewise suffering

and will suffer further injury. Defendants' refusal to fill vacant apartments,

and failure to maintain and rehabilitate other units, have led to a decline in

the overall physical environment. It is well-known that under-occupied, poorly

maintained projects present an open invitation to crime. Courts have considered

such conditions to constitute irreparable injury requiring injunctive relief.

See Cole v. Lvnn. 389 F. Supp. 99, 105 (D.D.C. 1975). See Cole v. Hills.

396 F; Supp. 1235, 1238 (D.D.C. 1975). Plaintiffs likewise suffer irreparably

"if they must live in inadequate, often health endangering housing for any

18

period of time." Johnson v. United States Dep't oi Aqric., 734 F.2d 774, 789

(11th Cir. 1984).

Moreover, the relocation tenants face as a consequence of defendants'

policies of vacating and demolishing buildings has also been deemed to

constitute irreparable harm. See Johnson v. United States Dep't of Aqric..

supra 734 F. 2d at 788 (noting the "intangible value" of a person's home and

the uprooting caused by relocation). As one court has noted, "It is axiomatic

that wrongful eviction constitutes irreparable injury." Brown v. Artery Pro..

Inc., 654 F. Supp. 1,106, 1,118 (D.D.C. 1987) (granting preliminary injunction

in Title VIII action by tenants in low-rent apartment complex seeking to avoid

ouster during conversion to high-rent units); modified. f>91 F. Supp. 1459

(D.D.C. 1987) (upholding grant of preliminary injunction). Finally, the

discriminatory impact of defendants' policies upon the tenant class, forcing

relocation of many tenants into more segregated housing and neighborhoods, also

Q

''iolates Title VIII, invoking the Gresham presumption. See Trafficante v.

Metropolitan Life Ins.. Co.. 409 U.S. 205, 209-210 (1972) (recognizing harm from

the loss of the "important benefits of interracial associations").

Regina Latimore, a tenant in Kretchmer Homes, likes living in an

integrated area because it gives her access to different ideas and people.

Latimore Aff. at par. 9, Exh. 7. Kretchmer is located on the border of

Elizabeth, which is over 75% white. The area is also racially and ethnically

diverse.

Plaintiff Theresa Williams of Kretchmer Homes has recently had her

apartment fully renovated by the NHA, yet the NHA now is asking her to leave as

9See page 18, supra.

19

it intends to demolish the building. T. Williams Aff. at 3, 5, Exh. 7. She

likes her apartment and does not want to move. She has lived in Kretchmer Homes

for 23 years, likes living in an integrated area, has many friends in the area,

and does not want to start all over again. Ld^ at par. 2, 10, 14. Indeed,

Kretchmer tenants unanimously opposed demolition and relocation. Aff. of

Estrella Johnson and attached petition of Kretchmer tenants, Exh. 7.

The other factors of the Rule 65 balancing test, harm to others and the

public interest, unquestionably favor the grant of a preliminary injunction.

Defendants cannot complain of harm from an order requiring them to carry out

their functions to provide affordable, snfe, and sanitary housing in a city with

desperate housing needs. See Resident Advisory Bd. v. Rizzo. 429 F. Supp. at

226. It is indisputably in the public interest for social welfare laws to be

implemented (see Johnson v. United States Dep't of Aqric.. supra 734 F.2d at

788), for the city's acute, shortage of decent, sanitary, low-income housing to

be remedied (see Cole v. Lvnn. supra 389 F. Supp. at 102, 105) and for low-

income tenants not to be needlessly displaced (see Richland Park Homeowners

Ass'n., Inc, v. Pierce. 671 F.2d 935, 943 (5th Cir. 1985)).

Plaintiffs' Likelihood of Success on the Merits

The remaining points of this brief address each of plaintiffs' legal

claims supporting this request for a temporary restraining order and preliminary

injunction.

Under the Administrative Procedure Act, 5. U.S.C. 701 et sefl. an agency's

"decision must be overturned if it was arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of

discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law', or if the decision failed

to meet '.tatutory, procedural or constitutional requirements." Business

Association of University City v. Landrieu, 660 F.2d 867, 873 (3d Cir. 1981).

20

Tht district court must make a "searching and careful" inquiry into the facts

umerTying the agency's decision. See Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v.

Vope, 401 U.S. 402, 416 (1971). Moreover, "[w]hen an administrative decision

is made without consideration of all relevant factors it must be set aside."

Shannon v. U.S. Dept, of Housing and Urban Dev., 436 F.2d 809 at 819 (3d Cir.

1970). As discussed below, the Secretary's actions and decisions at issue on

this application must be immediately suspended because they are not in

accordance with the National Housing Act, as amended by the Housing and

Conmunity Development Act of 1987, because they fail to take into account

numerous relevant factors, and because they are contrary to the facts *nd the

evidence. Similarly, the challenged NHA actions violate numerous provisions of

applicable law, and must be enjoined.

POINT II

THE NHA HAS NOT DEMONSTRATED, NOR COULD HUD PROPERLY

FIND, THAT THE COLUMBUS AND KRETCHMER BUILDINGS SLATED

FOR DEMOLITION ARE OBSOLETE, INFEASIBLE OF MODIFICATION

TO RETURN THEM TO USEFUL LIFE, OR, IN THE CASE OF

KRETCHMER, NECESSARY TO DEMOLISH TO HELP ASSURE THE

USEFUL LIFE OF THE REMAINDER OF THE PROJECT.

42 U.S.C. § 1437o(a), as amended by the Housing and Community Development

Act of 1987, provides that the Secretary may not approve an application for

demolition of a project or a portion thereof unless a determination has been

made that:

. . . the project or a portion of the project is

obsolete as to physical condition, location or other

factors making it unusable for housing purposes, and no

reasonable program of modification is feasible to return

the project or a portion of the project to useful life;

or in the case of an an-l-.Cation proposing the

demolition of only a portior of the project, the

demolition will help to assu^ the useful life of the

remaining portion of the .project. (Emphasis supplied.)

21

The 1987 Act thus requires, as a precondition to demolition, a finding

that a project be obsolete, and that there are no reasonable programs of

modification. The conjunction "and" was added by the 1987 Act, replacing the

earlier disjunctive "or." This change makes demolition much more difficult to

sustain; under the previous version of this section a housing authority seeking

demolition had to satisfy only one of these tests (obsolescence, infeasibility

of modification, or necessity to assure the useful life of the remainder of the

project).

The relevant legislative history of the successive versions of the

National Housing Act demonstrates that Congress intended demolition or

disposition only as an absolute last resort.^ "Given the desperate need for

^ The National Housing Act has long emphasized the need to preserve and

expand the supply of low income housing. In the United States Housing Act of

1949, Congress set a national goal of "a decent home and suitable living

environment for every American family." 42 U.S.C. Section 1441. Frustrated with

the slow national progress toward this goal, Congress in 1968 reaffirmed it

explicitly. 42 U.S.C. Section 1441(a). In 1974, Congress found the nation

still lagging in its pursuit of the goal of increasing the quality and quantity

of low income housing, and was particularly concened about the increasing

abandonment and neglect of such housing. 42 U.S.C. Section 1441a(b). Congress,

therefore amended the Act in 1974 to require "a greater effort . . . to encourage

the preservation of existing housing . . . . " 42 U.S.C. 1441a(c).

The Housing and Community Development Act (HCDA) of 1987; strengthened the

express federal commitment to preservation, as well as recognizing even greater

needs for increasing the supply of public and subsidized housing. Congress 0

specifically found that recent reductions in federal assistance have contributed

to a "deepening housing crisis for low and moderate income families," 42 U.S.C.

Section 5301 (note), Pub. L. No. 100-242, Section 2(a)(1), 101 Stat. 1819 (1987),

and that "the national tragedy of homelessness" dramatically demonstrates the

few available alternatives for shelter for "people living on the economic margins

of society." Section 2 (a)(3). Congress therefore declared the purposes of the

Act: (1) "to reaffirm the principle that decent affordable shelter is a basic

necessity" and to remedy a "serious" housing shortage; (2) to make federal

housing assistance more equitable by providing for "the less affluent people of

the nation," (3) "to provide needed housing assistance for homeless people'1, and

others "who lack affordable decent, safe and sanitary housing;" and (4) to reform

existing programs to ensure the most effici''o+ delivery of federal assistance.

Section 2(b).

22

affordable housing for lower-income families, care must be taken not to sell or

demolish these units unless no way can be devised to make the units livable. "

(Emphasis added.) H.R. REP. NO. 122, 100th Cong., 1st Sess. 25 (1987), and H.R.

REP. NO. 230, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 28 (1985). The legislative history of an

earlier version of this section sounds this same theme: "(I)t must be

emphasized that the demolition or sale of any public housing project in this

country should only be permitted as last resort.” (Emphasis added.)^

Columbus Homes

In approving the Columbus Homes demolition application, HUD found that the

project was "obsolete as to physical condition making it unusable for housing

and that no reasonable program of modifications is feasible to return the

project to useful life." Exh. 4. Although the statute requires a demonstration

of both obsolescence and infeasiblity, there is simply no competent evidence

before HUD to support either of these determinations. The NHA presented .no

professional detailed analysis of feasible renovation alternatives for Columbus

Homes.

It axiomatic that HUD's discretion "must be exercised in a manner

consistent with the national housing objectives set forth in the several

applicable statutes." Kirby v. U.S. Dept, of HUD. 675 F. 2nd 60, 68 (3rd Cir.

1982); Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Lynn. 501 F. 2nd 848,855 (D.C. Cir. 1975);

Cole v. Lynn, 389 F. Supp. at 102.

^ Staff of the House Subcommittee on Housing and Community Development

of the Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, 98th Corg., 1st Sess.

Compilation of the Domestic Housing and International Recovery and Financial

Stability Act of 1983 at 319 (Comm, print 1984). "(T)he Committee believes that

every effort should be made to retain the present stock of public housing." S.

REP. No. 142 98th Cong., 1st Sess. 26 (1982) reprinted in 1983 U.S. Code Cong,

and Admin. News 1768, 1809. "The purpose of this provision is to ensure th't

the public housing stock remains available for housing for low-income families."

H. R. REP No. 123, 98th Cong., 1st Sess. 3C (1983).

23

In contrast, plaintiffs' nationally recognized public housing experts (see

jjrfra). headed by Jeffrey Lines of OKM Associates and Dr. Thomas Nutt-Powell of

On-Site Insight, conducted an extensive inspection and analysis, and concluded

that the rehabilitation of Columbus Homes is feasible from a structural and

design perspective. Exh. 1, Nutt-Powell Aff. at par. 13. They have also

identified specific renovation alternatives.

Mr. Lines has extensive experience in the management and rehabilitation

of distressed public housing developments. Lines Aff. at par. 7, Exh. 1. Dr.

Nutt-Powell has extensive experience in assessing the rehabilitation and

physical needs of distressed public housing developments. Nutt-Powell Aff. at

par. 5, Exh. 1. His firm, OST, has served as the lead infection team for a HUD

survey of the nation's public housing stock, id. at par. 4. The affidavits and

resumes of Mr. Lines and Dr. Nutt-Powell, and the incorporated reports of OKM

and OSI on Columbus Homes, are contained in Exh. 1. OKM's and OSI's reports

contain substantial detailed analysis, and include site, unit, and building

renovation and reconfiguration diagrams, detailed cost estimates of renovation

alternatives, and numerous attachments and supporting documentation.

The OKM/OSI reports are based on a physical inspection of Columbus Homes,

and on a review of the architectural diagrams. The reports demonstrate that

there are feasible renovation alternatives for the rehabilitation of Columbus

Homes to provide decent housing for the poor. OKM founc that "there are a

number of design and modernization options which could be pursued that may offer

significant opportunities for preserving the Columbus Homes housing development

as a viable housing resource." Exh. 1, OKM Columbus Homes Report at 1. OSI

24

presented a detailed analysis of four* 1 such

Lines noted that "(e)ach of the options

cases substantially below, the estimated

guidelines which would apply to the NHA's

at 4.

Significantly, the NHA did not

analysis,and presented no expert studies

1 ?options. As to renovation costs,

(except one) are below, and in some

new public housing development cost

replacement application. . . ." Id.

conduct a similar inspection and

to HUD justifying the demolition or

12 These options are:

1. Rehabilitate Columbus Homes "as is" without

substantial redesign of the site or

structures and no reduction in total number

of units at the development.

2. Major rehabilitation with modest redesign

of buildings and site with a reduction of

approximately 17 percent of the total number

of units and a net loss of two buildings on

site.

3. Major rehabilitation with major redesign of

buildings and site with a reduction of

approximately 34 percent of the total number

of units including demolition of selected

existing structures and construction of new

buildings.

4. Major rehabilitation with major redesigning

of each and every component of the property

including major demolition of buildings

(approximately one-half) leaving a total of

864 units consisting of one and two bedroom

apartments the development which can if

desired, be renamed and managed separately.

Further site design has been given oome

substantial attention in order to iua\e the

site more useful and beneri. .a 1 to

residents.

25

1 o

ruling out renovation alternatives for Columbus Homes. Such study must occur

before such a massive elimination of housing stock is proposed or approved. As

stated by Mr. Lines, the OSI options for rehabilitation and constriction "are

presented as examples of items which the NHA could recommend and should have

analyzed thoroughly before proceeding with plans for demolition." Id at 4.

Indeed the NHA's Master Plan stated that a study would be undertaken on

Columbus; it never occurred. Exh. 9, at 26.

The explicit consideration of alternatives and explanation as to why a

specific alternative is rejected is particularly warranted here, since past NHA

documents state that all or part of Columbus is viable. The 1984 Master Plan

stated:

Reconfiguration of family high-rises to

house families with children in walk-up and

duplex units on the lower floors and

childless households in elevator-accessed

units on the upper floors is a viable option

at all six family high-rise projects.

Exh. 9, at 20.

The NHA Master plan also mentioned as a "high priority" the "completion

of the redesign of Columbus Homes . . . which (is) scheduled to enter the

construction phase within one year, but (has not) been funded " (Emphasis 13

13 The only arguably relevant document in the application is a two-page

letter from Mr. Alvin Zach, (City of Newark's Director of Engineering) suggesting

in a clau<;e that the buildings are "unsafe as to structural aspects." Exh. 3

at Enclosure #4. Commenting on this letter, Mr. Lines stated: "There is no

analysis that we could find in the application that supports this statement.

The needed background to support such a determination or implication is not

documented in the statement, and we have not reviewed any outside professional

study which supports this statement." Exh. 1, OKM Columbus Rep't at 8.

In addition-, HUD was aware of the NHA's extremely poor management record.

See Exhs. 14, 20, and 21. This poor record increased HUD's responsibility to

require preparation of a detailed professional study examining all alternatives,

before approving demolition. HUD's failure to do so was arbitrary ancf

capricious.

26

added.) ■ Id. at 38. Indeed, as late as July, 1987, the NHA's Comprehensive

Occupancy Plan stated that the NHA intended to retain 582 units at the Columbus

site. Exh. 1, OKM Columbus Homes Rep't at 3. Moreover, when the NHA solicited

proposals for the development of Columbus Homes, two development teams proposed

retaining major, portions of the existing site and structures. Id. at 8-9."

In view of the strong evidence that Columbus Homes can be rehabilitated,

the absence of any detailed professional study before HUD to the contrary, and

the NHA's own documents suggesting the viability and desirability of renovating

all or part of Columbus Homes, there was no evidentiary basis supporting HUU's

determination that "no reasonable program of modification is feasible to return

the project or a portion of the project to useful life."

In addition, HUD's failure to consider relevant factors provides an

alternative basis for suspending it* demolition approval under Section 1437p(a).

In Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe. 401 U.S. 402, 416 (1971), the

Supreme Court held that a district court reviewing an agency decision must

determine "whether the decision was based on a consideration of the relevant

factors. . . . " Accord. Shannon v. U.S. Dept, of HUD, 436 F. 2d 809, 819 (3d

Cir. 1970). The NHA's application to HUD to demolish Columbus Homes contained

no discussion of alternatives to demolition. In approving the NHA's demolition

request, HUD made no reference to any alternatives to demolition. It must be

concluded that HUD did not consider alternatives to demolition, and that there

is a strong likelihood that HUD's decision will be set aside on the merits. See,

e.q.. Silva v. East Providence Housing Authority. 565 F. 2d 1217, 1223-25 (1st

Cir. 1977) (where record of HUD's decision-making prior to termination of low-

income housing project was defective for failure of HUD to consider unexplored

alternatives, prospective tenants of project were entitled to remand to HUD.

27

In addition to actually considering alternatives to demolition, HUD is

also required to provide reasoning for rejecting those alternatives. In Price

v. Pierce. 615 F. Supp. 173, 184-85 (M.D. 111. 1985), HUD's decision to

eliminate ninety units from an assisted housing project was found not properly

based on consideration of all relevant factors where HUD failed to explain fully

its reasons for approval of reductions, and thus plaintiffs, and applicants for

assisted housing were entitled to have the decision vacated and remanded. In

Cole v. Lvnn. 389 F. Supp. 99, 102 (D.D.C. 1975), a court held tenants entitled

to a preliminary injunction to prevent further demolition of a low-income

housing project, and to restore the project to pro-demolition condition, where,

inter alia. HUD failed to explain whv alternatives to demolition were

disregarded or deemed impractical "A rational statement of the ultimate

decision and the reasons for it must be provided, which will then be reviewable

by the courts for abuses of discretion." Id. at 104 (citation omitted). See

also Kent Farm Co. v. Hills. 417 F. Supp. 297, 302 (D.n ,C. 1976) (significant

final agency decision should be documented by a record of factors rationally

considered by agency; "'Courts should require administrative officers to

articulate the standards and principles that govern their discretionary

decisions in as much detail as possible.'")

HUD clearly failed to articulate the reason for rejecting alternatives to

demolition. Where, as plaintiffs have demonstrated, clear alternatives to

demolition exist, and where indeed the NHA was aware of alternatives to

demolition, HUD's failure to explain in detail the basis for its decision and

the reasons for rejecting alternative'' and demolition is a substantial and

reversible error.

In addition to failing to demonstrate infeasibility of renovation,

defendants also lack competent documentation that the buildings are obsolete as

required by 42 U.S.C. 1437p(a). The statute requires a determination that the

project is obsolete as to "physical condition, location, or other factors." In

approving the Columbus demolition, the Secretary found that the project is

obsolete as to "physical condition."*4

Such structural deficiency has not been demonstrated at Columbus Homes.

Nor is Columbus obsolete as to its physical design. The Stella Wright Housing

Project, a project similar in design and size to Columbus, is currently

providing housing to 800 tenants. There are 401 vacant units in Stella Wright,

which the NHA is planning to rehabilitate and use for relocating Columbus Homes

displaces. See HAP at Exh. A, Exh. 12. To address problems of crime and

security, the city located a Newark police station in Stella Wright to address

those concerns. The NHA has offered no rationale why an increased police

presence cannot also be implemented and effective at Columbus. See Exh. 18,

Comp. Mod. Plan at 87 ("Furthermore, a new poli:e substation with a complement

of over 50 officers and Soul-0-House, a full service outpatient, drug

rehabilitation center, have recently been relocated to Stella Wright Homes.")

(Emphasis in original).

After a review, of the evidence before HUD. this Court must conclude that

the agency decision approving demolition was arbitrary and capricious, and an

abuse of discretion. Mr. Lines, after reviewing many relevant documents and the

NHA application to demolish Columbus Homes, stated that:

. . . we have reviewed the complete NHA demolition

*4 There was no finding of obsolescence as to 'location" or "othe- factors.

The location of Columbus Homes is a choice one, located near the train station,

and near public transportation for down^wn. It is ideally located for low-

income people who frequently cannot afford automobiles. See DeLuca Affidavit

at 17, Exh. 2, see also OKM Columbus report at 4-5, Exh. 1.

29

application submitted to and approved by HUD, and no

study is contained in this application. However, there

is a two-page letter from Mr. Alvin Zach (City of

Newark's Director of Engineering) which has merely a

conclusory statement that the buildings are unsafe as

to structural aspects. There is no analysis that we

could find in the application which supports this

statement. Further . . . the needed background to

support such a determination or implication is not

documented in the statement and we have not reviewed any

outside professional study which supports this

statement.

Exh. 1, OKM Columbus Homes Rep't at 3,8.

Mr. Lines also debunks the NHA's sweeping dismissal of high rises as

suitable housing for families:

NHA has not presented any persuasive evidence that the

renovation of highrise units in the City of Newark is

not feasible. In fact, in the case of the Stella Wright

housing development it appears that the NHA is

requesting that the highrise units be preserved. Tn the

Comprehensive Plan for Modernization (CPM) and the

Comprehensive Occupancy Plan (COP) the NHA does not

appear to provide any strong evidence that the high rise

developments should be destroyed. The process of

addressing management and physical deficiencies through

the wholesale demolition of substantial numbers of

housing units is extreme and does not appear to be fully

supported in either the CPM or COP.

Id. at 8.

Finally, the destruction of the buildings is just the first step in a

planned disposition of the property. The demolition is simply designed to clear

the land so that it is more attractive for private developers. Indeed, before

NHA had even filed its demolition application for Columbus, it had already

entered into a contract with a private party (a firm led by Kenneth A. Gibson

and Peter Macco) to sell the cleared site. (Exhs. 61, 62) Nonetheless, the

planned disposition was not part of the demolition application, oven though both

the statute and HUD regulations have distinct criteria guiding the Secretary's

30

consideration of whether to approve the proposed disposition of a public housing

site.

There is no indication that the planned disposition would meet the

requirements of 42 U.S.C. 1437p(a)(2), nor did the Secretary of HUD so find.

For defendant HUD to have approved a demolition of a project when it was

expressly part and parcel of a planned disposition of that project, without any

consideration or decision whether the integrally-related disposition itself

satisfied the statute and regulations thereunder, was a serious abuse of

discretion and violation of applicable law. Without evaluating the demolition

and disposition an integrated scheme, there is no basis to judge, inter al_ia,

the effect on overall availability of public housing land and units in Newark,

just one part of the evaluation required by law.

KRETCHMER HOMES

The Kretchmer Homes housing project consists of five eight-story and the

two low-rise buildings, located near the Elizabeth bcrder, containing 730 units.

In September, 1985, HUD approved the demolition of three eight-story buildings,

with 372 units. With reference to the three statutory tests, the Secretary made

no finding as to obsolescence. He did determine "that the demolition of a

portion of these projects will help to assure the useful life of the remain

portions." Exh. 5. In addition, he determined "that it is not economically or

socially feasible to rehabilitate these projects to their original condition."

Id. In approximately April, 1988, two and one-half years after this approval,

the NHA solicited bids from demolition companies. On March 16, 1989 the NHA

ratified demolition contracts for the three buildings.

Notwithstanding the Secretary's determination that partial demolition of

Kretchmer would help assure the useful life of the remainder, in July, 1988 the

31

NHA announced plans to sell or demolish the remaininq five buildings of

Kretchmer Homos (358 units). Exh. 3 at Ends. 5 and 5. It has been relocating

tenants from one of those these buildings as a prelude to demolition. See Exh.

7. Affidavit of Regina Latimore. The NHA has yet to submit an application for

this total demolition or disposition, and HUD has not approved it.

OKM arid OSI also conducted a detailed inspection of Kretchmer Homes. They

concluded that "(r)ehabilitation of Kretchmer (Homes) is feasible from a

structural and design perspective." Exh. 1, OSI Kretchmer Rep't at 1; See OKM

Kretcnmer Rep't. at 8. OSI further stated:

(T)here are many feasible options for

modernization and/or redevelopment of

Kretchmer Homes using the existing

structures. There appears to be no reason

from a structural or design option

perspective to abandon and/or demolish all

or part of the development. This

observation does not rule out some or even

substantial reconfiguration to some or all

of the buildings.

Ibid. OSI kretchmer Rep't. at 1. (Emphasis added.) Similarly OKM concluded:

TWle strongly believe that the renovation

of all buildings at Kretchmer Homes can be

accomplished in such a manner as to enhance

the overall development. As indicated in

the attached report from OSI there are a

number of design, renovation and occupancy

options1which if pursued could address any

problem with respect to density of

buildings, units or households at Kretchmer

Homes.

Ibid. OKM Kretchmer Rept at 8. (Emphasis added.) Moreover, in the opinion of

OKM, Kretchmer Homes is a strong candidate for receiving substantial

32

modernization money.^

Similarly, the NHA's own documents and studies support the contention that

Kretchmer Homes is a viable project. First, the NHA's original 1984 Master Plan

called for the rehabilitation and reconfiguration of Kretchmer; it did not

envisage demolition. See Exh. 9 at 19. ("The reconfiguration of Kretchmer

Homes (NJ2-10) is to begin in mid-1987 and completed by early 1989.") Exh. 9,

at p. 38, See also id. at 20. Second, the NHA's own consultants studied

Kretchmer Homes and set forth at least one feasible alternative for

rehabilitation that did not involve widespread demolition. See discussion at pp.

36-37 infra. (See Exh. 48 at 9).

Subsequent to HUD's approval of the partial demolition of Kretchmer, The

HCDA of 1987 became effective on February 5, 1988. Defendants take the position

that the 1987 Act does not apply to the Kretchmer approval, since it occurred

before the effective date of the Act.

Plaintiffs disagree, and contend in any event that the Secretary's

decision violates both the HCDA of 1987, and the pre-1987 version of 42 U.S.C. 15

15. OKM stated:

It should be noted, in a recent Congressional hearing

the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Public Housing stated

that the per unit rehabilitation cost for public housing

under the HUD Major Rehabilitation of Obsolete

Properties (MROP) is about the same as that estimated

for renovating Kretchmer Homes. MROP (which uses

housing development funds) and the Comprehensive

Improvement Assistance Program (CIAP) are two important

sources of funds which could be used to renovate this

property. Since there are strong redesign and

modernization alternatives (see attachment) and the

neighborhood area where Kretchmer Homes is located seems

stable, this property would likely be considered a

strong candidate for receiving CIAP or' MROP funding.

Id. at 6-7, Exh. 1.

33

143 7p.

The 1987 Act applies to Kretchmer Homes, notwithstanding the prior

approval, because subsequent to the effective date of the 1987 Act, the NHA is

taking - and HUD is approving - steps to demolish the buildings, thus invoking

the plain language of subsection (d) of the 1987 Act:

A public housing agency shal1 not take action to

demolish or dispose of a public housing project or a

portion of a public housing project without obtaining

the approval of the Secretary and satisfying the

conditions specified in subsections (a) and (bl of this

section.

See the discussion of the applicability of the 1987 Act to Kretchmer at

56-60, infra. Therefore, unless the NHA can show that it has met the

requirements of subsections (a) and (b), it cannot proceed with demolition. As

discussed at the beginning of this Point, the 1987 amendments changed the

disjunctive linking the requirements in subsection (a), meaning that all the

tests in the subsection must be satisfied.