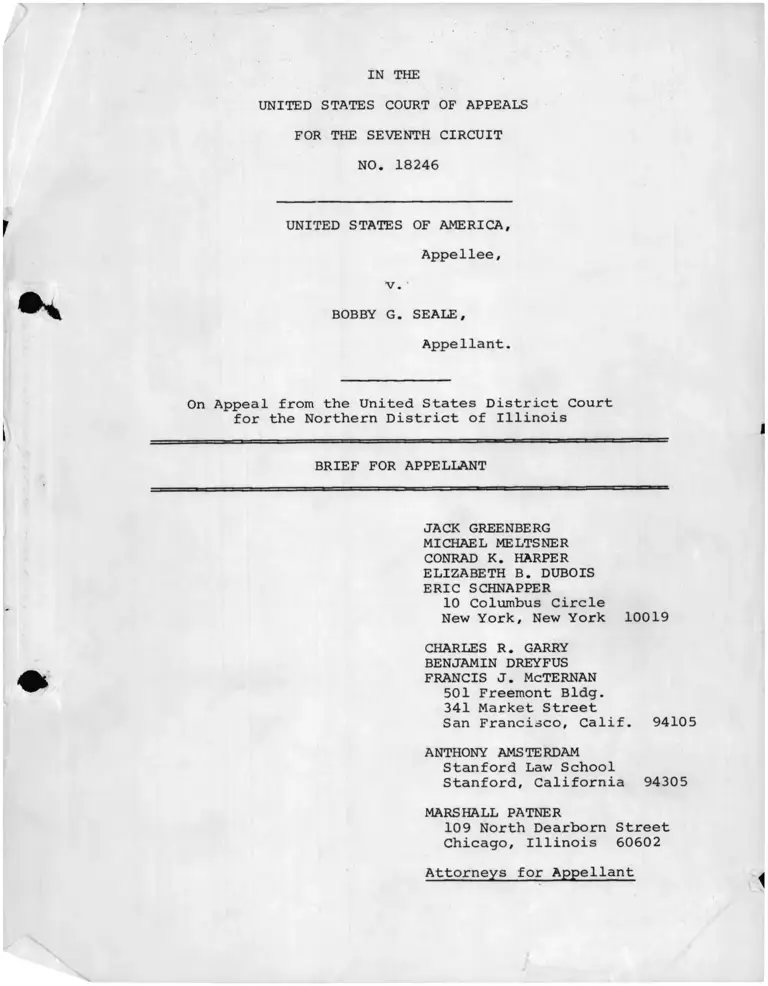

United States v. Seale Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Seale Brief for Appellant, 1970. c7f79fd6-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/681dc7e0-741a-4a00-a31c-f6138bd7fa3f/united-states-v-seale-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 18246

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee,

v.

BOBBY G. SEALE,

Appellant.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Illinois

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

CONRAD K. HARPER

ELIZABETH B. DUBOIS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

CHARLES R. GARRY

BENJAMIN DREYFUS

FRANCIS J. McTERNAN

501 Freemont Bldg.

341 Market Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94105

ANTHONY AMSTERDAM

Stanford Law School

Stanford, California 94305

MARSHALL PATNER

109 North Dearborn Street

Chicago, Illinois 60602

Attorneys for Appellant 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement Of The Issues Presented For Review ......... xix

Statement Of The Case .................................. 1

Summary Of Argument .................................... 4

ARGUMENT:

Introduction ....................... 7

1 < ...............

I. The Court's Wrongful Denial Of Defendant

Seale's Right To Counsel Of His Choice Or,

Alternatively, His Right To Represent Him

self, Requires Reversal Of The Contempt

Conviction ........................................... 1 7

A. The Court Wrongfully Denied Defendant

Seale's Right To Counsel Of His Choice

Or, Alternatively, His Right To RepresentHimself ...................................... 18

Facts .................................... 18

(1) The Court Wrongfully Denied Seale

the Right To Retained Counsel Of His

Choice ...................................... 32

(2) The Court Wrongfully Denied Seale

The Right To Represent Himself ............ 40

B. The Court's Wrongful Denial Of Appellant's

Sixth Amendment Rights Requires Reversal Of

His Contempt Conviction ........................ 49

II. In Imposing An Aggregate Sentence Of Four

Years For Criminal Contempt Without According

Appellant A Jury Trial, The Court Below Vio

lated His Rights As Defined In Bloom v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 194 (1968), and Cheff v. Schnackenbera,

384 U.S. 373 (1966) 54

A. Assuming That 16 Separate Contempts Were

Committed, The Court Erred In Imposing An

Aggregate Sentence In Excess Of Six Months

Without According Appellant A Jury Trial ..... 54

PAGE

B. The Court Erred In Proceeding Against

Appellant On Serious Criminal Contempt

Charges Without According Him A Jury

Trial ........................................... 62

C. Appellant's Conduct Constituted At

Most A Single Contempt And The Court Below

Thus Erred In Imposing A Sentence In

Excess Of Six Months Without According

Appellant A Jury Trial ......................... 65

III. In The Circumstances Of This Case Appellant

Was Entitled To Have His Contempt Charges Heard

By A Judge Other Than The Judge Who Presided

Over The Trial Out Of Which Said Charges Arose .... 77

A. Where Contempt Charges Arise Out Of

A Personal Confrontation With The Trial

Judge And Involve Personal, Critical And

Derogatory Comments About That Judge,

And Where That Judge Finds No Necessity

For Immediate Action, Then The Contemnor

Is Entitled To A Hearing Before Another

Judge ........................................... 79

B. Where The Trial Judge Becomes Per

sonally Embroiled With The Contemnor,

Then The Contemnor Is Entitled To A

Hearing On The Contempt Charges Before

Another Judge ................................... 91

IV. The Court Below Erred In Convicting

Appellant Summarily Rather Than According

Him The Procedural Safeguards Defined In

Rule 42(b) Of The Federal Rules Of Criminal g7

Procedure ...........................................

PAGE

A. Contemnors May Be Summarily Punished

Pursuant To Rule 42(a) Of The Federal

Rules Of Criminal Procedure Only Where

Instant Adjudication Is Found Necessary

To Ensure The Orderly Continuance Of

Trial Proceedings .............................. 98

B. Contemnors May Not Be Summarily

Punished Pursuant To Rule 42(a) Of The

Federal Rules Of Criminal Procedure For

Prior Acts Of Misconduct Where Prejudice

Is Caused By The Delay In Adjudication ........ 108

l i

PAGE

V. Assuming It Was Proper To Proceed Under

Rule 42(a), Appellant Was At Least Entitled

To Some Hearing And The Court Below Erred

In (A) Denying Him Any Opportunity To Pre

sent Evidence Or Argument Going To Guilt,

And (B) Denying Him An Adequate Sentencing

Hearing, Including The Right To Representa

tion By Retained Counsel ...........................

VI. Appellant's Conduct Did Not Constitute

Contempt Within The Scope Of 18 U.S.C. § 401 ..... 119

>• *

VII. Appellant's Conviction Violates Due

Process Because He Was Not Adequately Warned

That His Conduct Would Be Criminally Punished .... 137

VIII. Appellant's Conviction Should Be

Reversed And The Citation For Contempt Dismissed

In The Interests Of Justice ........................ 152

IX. The Matter of Electronic Surveillance ........ 176

Conclusion ............................................. 178

iii

TABLE OF CASES

Adams v. United States, 317 U.S. 269 (1942)............. 41

Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165 (1969)........... 177

Alexander v. Sharpe, 245 A.2d 279 (Me. Sup. Jud. Ct.

1968)...................................................... 1 0 1

Appeal of the S. E. C., 226 F.2d 501

(6th Cir. 1955)..................................... 114,138,152

Bachellar v. Maryland, 38 U.S.L. Wk. 4316 (1970)......... 132Baldwin v. New York, 38 U.S.L. Wk. 4554 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ......... 63

Bayless v. United States, 381 F.2d 67 (9th Cir. 1967) . . 40,43

Bell v. United States, 349 U.S. 81 (1955)........... 66,68,69,72

Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78 (1935)............. 156

Black v. United States, 385 U.S. 26 (1966)............... 177

Blockburger v. United States, 284 U.S. 299 (1932) . . . . 69,76

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S.194 (1968) ................... 14,15,16,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,62

63, 64,65,69,73,110,113,115,173

Bohr v. Purdy, 412 F.2d 321 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ............. 60

Borum v. United States, 409 F.2d 440 (D.C. Cir. 1967) . . 173

Braverman v. United States, 317 U.S. 49 (1942)....... 66

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941)............... 14

Brown v. United States, 359 U.S. 41 (1959)........... 14,104,105

Brown v. United States, 356 U.S. 148 (1958) 69,130,138

Brown v. United States, 264 F.2d 363 (D.C. Cir...................................................... 40,34,45,47

Bullock v. United States, 265 F.2d 683 (6th Cir. 1959). . . 76

Butler v. United States, 317 F.2d 249 (8 th Cir.) cert.

denied, 375 U.S. 838 (1963)............................. 41,46,47

Cafeteria Employees Union v. Angelos, 320 U.S. 293 (1943).. 132

Callan v. Wilson, 127 U.S. 540 (1888)................... 63,65

Page

IV

Cammer v. United States, 223 F.2d 322 (D.C. Cir. 1955),

rev'd, 350 U.S. 399 (1956).......................... ' 1 7 3

Cardona v. Perez, 280 N.Y. Supp. 2d 913 (App. Div.

1st Dept. 196 7)........................................... 1 1 4

Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506 (1962)................. 34

Carter v. United States, 135 F.2d 858 (5th Cir. 1943) . . 74

Chambers v. District of Columbia, 194 F.2d 336 (D.C

C i r * 1952) .......................................................... 60

Chandler v. Fretag, 348 U.S. 3 (1954)................... 12,112

Cheff v. Schnackenberg, 384 U.S. 373 (1966) . . . 54,55,63,64,115

Chewning v. Cunningham, 368 U.S. 443 (1962)............. 1 1 3

Chivers v. State, 5 Ga. App. 654, 63 S.E. 703 (1909). . . 38

Clark v. District Court, 125 N.W. 2d 264 (Iowa 1963). . . 69

Coleman v. Alabama, 38 U.S.L. Wk. 4535 (1970)........... 52

Commonwealth v. Langnes, 434 Pa. 478, 255 A.2d 131

(1969), cert granted sub nom. Mayberry v. Pennsylvania,

April 6 , 1970, No. 1389.................................. 57,58

Commonwealth v. Mayberry, 255 A.2d 548 (Pa. Sup.

Ct. 1969).................................................. 57

Connally v. General Const. Co., 269 U.S. 385 (1926) . . . 138

Cooke v. United States, 267 U.S. 517 (1925) . . . 87,100,106,114

Cornish v. United States, 299 F. 283 (6 th Cir. 1924). . . 88

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1964).........126,140,149-50,168

Dancy v. United States, 361 F.2d 75 (D.C. Cir. 1966). . . 51

Daschbach v. United States, 254 F.2d 687

(9th Cir. 1958)........................................... 137,147

Dearinger v. United States, 344 F.2d 309 (9th

cir- 1 9 6 5 ) ................................................ 40,46

DeStefano v. Woods, 392 U.S. 631 (1968).................. 5 7

District of Columbia v. Clawans, 300 U.S. 617 (1937). . . 63,65

Page

Cammer v. United States, 350 U.S. 399 (1956)............. 14

v

District of Columbia v. Colts, 282 U.S. 63 (1930) . . . . 63,64

Donovan v. Dallas, 377 U.S. 408 (1964)............ 172

Duke v. United States, 255 F.2d 721 (9th Cir. 1958) . . . 41

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)................. 63,115

Dunn v. United States, 284 U.S. 390 (1932)....... 67

Dunn v. United States, 388 F.2d 511 (10th Cir. 1968). . . 172

English v. State, 8 Md. App. 330, 259 A.2d 822 (1969) . . 38

Ex parte Craig, 282 Fed. 138 (2d Cir. 1 9 2 2 ) ............ 130

Ex parte Hudgings, 249 U.S. 378 (1919)................... 130,136

Ex parte McLeod, 120 Fed. 130 (N.D. Ala. 1903)........... 152

Ex parte Snow, 120 U.S. 274 (1887)........................ 67,71

Ex parte Terry, 128 U.S. 289 (1888)...................... 100

Franken v. United States, 248 F.2d 789 (4th Cir. 1957). . 38

Gautreaux v. Gautreaux, 220 La. 564, 57 So.2d 188 (1952). . 74,75

Gelling v. Texas, 343 U.S. 960 (1952)................... 138

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)............... 52

Gilmore v. United States, 273 F.2d 79 (D.C. Cir. 1959). . 38

Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942)............ 34,39

Gore v. United States, 357 U.S. 386 (1958)............... 72

Great Lakes Screw Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 409 F.2d 375

(7th Cir. 1969)........................................... 1 3 5

Green v. United States, 356 U.S. 165

(1958)................................... 14,56,99,139,140,155,174

Gregory v. Chicago, 394 U.S. Ill (1969)................. 132

Gridley v. United States, 44 F.2d 716 (6 th Cir. 1930) . . 129

Hallinan v. United States, 182 F.2d 880 (9th

Page

vi

Harrison v. United States, 7 F.2d 259 (2d Cir. 1925). . . 173

Heflin v. United States, 358 U.S. 415 (1959)............. 66,72

Hendrix v. City of Seattle, 456 P.2d 696 (Wash.

Sup. Ct. 1 9 6 9 ) ........................................... 112

Herman v. United States, 289 F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1961) . . 159

Hickinbotham v. Williams, 228 Ark. 46, 305 S.W. 2d

841 (1957)................................................ 71

Hoffa v. United States, 385 U.S. 293 (1966)............. 177

Holt v. United States, 218 U.S. 245 (1910)................. 61

Holt v. Virginia, 381 U.S. 131 (1965)................. 114,120

Illinois v. Allen, 38 U.S.L. Wk. 4247 (1970). . . 62,77,137,141

In re Atterbury, 316 F.2d 106 (6 th Cir. 1 9 6 3 ) ....... 138

In re Brown, 346 F.2d 903 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 5 ) ........... 154

In re Foote, 76 Cal. 543, 18 P. 678 (1888)........... 103

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967)........................ 112

In re Hallinan, 459 P.2d 255 (Cal. 1969)............... 135,137

In re Johnson, 62 Cal. 2d 325, 398 P.2d 420 (1965). . . . 60

In re McConnell, 370 U.S. 230 (1962), reversing

Parmelee Transportation Co. v. Keeshin, 294 F.2d

310 (7th Cir. 1961)...................................... 124

In re Michael, 326 U.S. 224 (1945)...................... 14,140

In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 144 (1955)................... 78,89

In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948)................. 100,114,116

In re Osborne, 344 F.2d 611 (9th Cir. 1965) . . . . 74,109,173

In re Williams, 152 S.E. 2d 317 (N.C. Sup. Ct. 1967). . 114

International Bro. of Teamsters, etc. v. United States,

275 F.2d 610 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 0 ) ............................ 74

Page

Harris v. United States, 382 U.S. 162 (1965)..14,90,103,104,105

vii

James v. Headley, 410 F.2d 325 (5th Cir. 1969)......... 60,115

Joelich v. United States, 342 F.2d 29 (5th

Cir. 1 9 6 5 ) ............................................. 40,43

Johnson v. United States, 344 F.2d 401 (5th Cir.

1965).................................................... 114,138

Johnson v. United States, 318 F.2d 855 {3th Cir. 1963) . . 40

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938)................... 34

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1968)......................... 171

Juelich v. United States, 214 F.2d 950 (5th Cir. 1954). . 61

Kasson v. Hughes, 390 F.2d 183 (3d Cir. 1968) ......... 91,96

Kelley v. United States, 199 F.2d 265 (4th Cir. 1952) . . 173

Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U.S. 168 (1881).................. 155

Kinoy v. District of Columbia, 400 F.2d 761 (D.C.

Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ................................................ 154

Kobey v. United States, 208 F.2d 583 (9th Cir. 1953)... 38

La Buy v. Howes Leather Company, 352 U.S. 249 (1957) . . 155

Ladner v. United States, 385 U.S. 169

Page

(1958) ......................................... 65,66,68,69,72

Lee v. United States, 235 F.2d 219 (D.C. Cir. 1956) . . . 32

Lias v. United States, 51 F.2d 215 (4th Cir. 1931). . . . 38

Long v. State, 119 Ga. App. 82, 166 S.E.2d 365 (1969) . . 38

Longshoreman's Asso. v. Marine Trade Asso., 389 U.S.

64 (1967).................................................. 140

Maclnnis v. United States, 191 F.2d 157 (9th Cir.

1951)..................................................... 101,103

McCarthy v. United States, 394 U.S. 459 (1969)......... 34,35

McConnell v. United States, 375 F.2d 905 (5th

Cir. 1 9 6 7 ) ............................................. 34

McNabb v. United States, 318 U.S. 332 (1943)........... 155

viii

Page

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961)........................ 170

Marxuach v. United States, 398 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1968) . 33,38

Matheson v. Hanna-Schoelkopf Co., 122 Fed. 836 (E.D. Pa.

1903)...................................................... 153

Maxwell v. Rives, 11 Nev. 213 (1876)................. 71,72 ,75

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967)................... 52,113

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)................. 52

Moore v. Michigan, 355 U.S. 155 (1957)................... 113

Murrell v. United States, 253 F.2d 267 (5th Cir. 1958). . 173

Musser v. Utah, 223 P.2d 193 (1950)...................... 138

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)................. 139

Nelson v. Holzman, 300 F. Supp. 201 (D. Ore. 1969). . . . 115

Nilva v. United States, 227 F.2d 74 (8th Cir. 1955) . . . 106

Nye v. United States, 313 U.S. 33 (1940)................. 14

O'Brien v. United States, 386 U.S. 345 (1967)........... 177

O'Bryant v. District of Columbia, 223 A.2d 799

(D.C. Mun. Ct. App. 1966)................................ 60

Offutt v. United States, 348 U.S.

11 (1954).............................. 58,88,89,95,107,138,173

Offutt v. United States, 208 F.2d 842 (D.C. Cir. 1953)

rev'd, 348 U.S. 11 (1954).............................58,167,173

Offutt v. United States, 232 F.2d 69 (D.C. Cir.),

cert, denied, 351 U.S. 988 (1956)....................... 107,116

Offutt v. United States, 145 F. Supp. Ill (D.D.C.

1956).................................................... 74,167

Olimpius v. Butler, 248 F.2d 169 (4th Cir. 1957)......... 173

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928)........... 170

McNeill v. United States, 236 F.2d 149

(1st Cir. 1956)........................................... 74

IX

Panico v. United States, 375 U.S. 29 (1963) . . . .

Parmelee Transportation Co. v. Keeshin, 294

F .2d 310 (7th Cir. 1961) rev'd sub nom.

In re McConnell, 370 U.S. 230 (1962) ...............

Pagano v. United States, 224 F.2d 682 (2nd Cir. 1955)

Parmelee Transportation Co. v. Keeshin, 292

F .2d 806 (7th Cir. 1961) ...............

People v. Burson, 11 111. 2d 360, 143 N.E.

2d 239 (1957) .........................................

People v. Burt, 257 111. App. 60 (1930)...............

People v. Crovedi, 53 Cal. Rptr. 284, 417 ...........

People v. Riela, 200 N.Y. Supp. 2d 43, 7 N.Y.

2d 571, 166 N.E. 2d 840 (1960), cert. denied,

364 U.S. 474 (1960) ..................................

People ex rel. Amarante v. McDonnell,

100 N.Y. Supp. 2d 463 (S. Ct. Kings Co. 1950) . . . .

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932).................

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948) ...............

Prince v. United States, 352 U.S. 322 (1957) .........

Raley v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 423 (1959) ...................

Releford v. United States, 288 F.2d 298

(9th Cir. 1961) .......................................

Reynolds v. Cochran, 365 U.S. 525 (1961) .............

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879) .........

Reynolds v. United States, 267 F.2d 235

(9th Cir. 1959) .....................................

Richardson v. State, 288 S.W. 2d 500

(Tex Ct. Crim. App. 1956) ............................

Rollerson v. United States, 343 F.2d 269

(D.C. Cir. 1964).......................................

Sacher v. United States, 343 U.S. 1

(1952), affirming 182 F .2d 416

(2d Cir. 1950) .........................................

x

173

105, 116

59, 124, 135,

173

Page

59, 98, 101,

130

43

103

38, 39

71

72, 75

32

41

72

126, 139, 150

38, 39

32, 112, 113

61

42

38

105, 116

14,58,87,88,8

99,101,102,10

108,109,110,1

138,168,173

Page

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) . . . 36, 37, 162

Schick v. United States, 195 U.S. 65 (1904).......... 66

Scull v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 359 U.S.

344 (1959) 151

Shibley v. United States, 236 F.2d 238

(9th Cir.), cert denied, 352 U.S. 873 (1956) . . . . 74, 109, 138

Shillitani v. United States, 384 U.S. 364 (1966) . . . 140

Shoemaker v. K-Mart, 294 F.Supp. 260

(E.D. Tenn. 1 9 6 8 ) ..................................... 74

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 (1959)............. 139

Smotherman v. United States, 186 F.2d 676

(10th Cir. 1950) 130

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F.Supp. 392

(E.D. La. 1 9 6 8 ) ................................... 162

Solano Acquatic Club v. Superior Court, 131

P.874 (Cal. 1 9 1 3 ) ................................. 71

Sorrells v. United States, 287 U.S. 435 (1932) . . . . 167

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 608 (1967)............. 113

Spencer v. Dixon, 248 La. 604, 181 So.2d 41 (1965) . . 114

State v. Frontier Airlines, Inc.,

174 Neb. 172, 116 N.W. 2d 2 8 1 ........................ 71

State v. Grey, 225 La. 38, 72 So.2d 3 ............... 74

State v. King, 47 La. Ann. 701, 17 So. 288 (1895) . . 71

State v. Lucas, 24 Wis. 2d 82, 128 N.W. 2d

422 (1964) ........................................... 60

State v. Mouser, 208 La. 1093, 24 So. 2d 151 (1945) . . 75

State v. Owens, 54 N.J. 153, 254

A.2d 97 (1969) ....................................... 59, 60

State ex rel Attorney General v. Circuit

Court, 97 Wis. 1, 72 N.W. 193 (1897) ............... 14

Steadman v. Duff, 302 F.Supp. 313 (M.D. Fla.

1969) ................................................ 60

Sanchez v. United States, 311 F.2d 327

(9th Cir. 1 9 6 2 ) ...................................... 41, 47

xi

/ Page

1Strombergjv. California, 283 U.S . 359 (1931)......... 132

(.Tauber v.jGordon, 350 F.2d 843 (3rd Cir. 1965) . . . .

1

74,135,167,1'

Tessmer jr. United States, 328 F.2d 306

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 4 ) .......................................{ 173

Thomas v;. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 (1945)............... 132

Thomas v. United States, 368 F.2d 941

(5th Cir. 1966) ....................................... 155

Tobin v. Pielet, 186 F.2d 886 (7th Cir. 1951)......... 76

Toledo Newspaper Co. v. United States, 247 U.S.

402 (1918) ........................................... 1 0 0

Toussie v. United States, 25 L.Ed 2d 156 (1970) . . . . 76

Townsend v. Burke, 334 U.S. 736 (1948) ............... 113

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927) ................... 95

Ungar v. Sarafite, 376 U.S. 575 (1946) ............... 78,87,90,96,

106,114

Union Producing Co. v. Federal Power

Comm'n., 127 F.Supp. 88 (D.D.C. 1954) ............... 89

United States v. Abbamonte, 348 F.2d 700

(2d Cir. 1965), cert, denied, 382 U.S.

982 (1966) ........................................... 33,44,46

United States v. Abe, 95 F.Supp. 991

(D. Hawaii 1950) ..................................... 75

United States v. Adams, 281 U.S. 202 (1930) ........... 67

United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681 (1964) ......... 56,57,153

United States v. Barnett, 330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963) 61

United States v. Barnett, 346 F .2d 99 (5th Cir. 1965) . 61,153,159,1'

United States v. Bentvena, 319 F.2d 916

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 375 U.S.940

(1963) ................................................ 33,46,47

United States v. Bergamo, 154 F.2d 31 (3d Cir. 1946) . 36

United States v. Birrell, 286 F.Supp.

885 (S.D. N.Y. 1968) .................................. 42,45,47

X l l I

Page

United States v. Bollenbach, 125 F .2d

458 (2d Cir. 1942)...................

United States v. Bradford, 238 F.2d 395

(2d Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 352 U.S.

1002 (1957)..........................

United States v. Bradt, 294 F .2d 879

(6 th Cir. 1 9 6 1 ) ......................

United States v. Brandt, 196 F .2d 653

(2d Cir. 1952) ...................

United States v. Cantor, 217 F.2d 536

(2d Cir. 1954) ................... .

United States v. Cole, 365 F.2d 57

(7th Cir. 1966) ...................

United States v. Coombs, 390 F.2d 426

(6 th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ..........................

United States v. Cores, 356 U.S. 405 (1958)

United States v. Davis, 260 F.Supp. 1009

(E.D. Tenn.), aff'd, 365 F.2d 251

(6 th Cir. 1966) ........................

United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d 201

(2d Cir. 1950) ...................

United States v. Denno, 239 F.Supp. 851 (S.D. N.Y.

1965), aff'd, 348 F.2d 12 (2d Cir. 1965),

cert, denied, 384 U.S. 1007 (1966) ...............

United States v. Denno, 313 F.2d 457

(2d Cir. 1963) ...................................

138

36

91,138,173

159

43

38, 43

91, 96

66

40,42,43

46,47,137,13*

40,47,49

119

United States v. Empsak, 95 F.Supp. 1012

(D. Del. 1951)......................................... 67, 71, 75

United States v. Follette, 270 F.Supp. 507

(S.D. N.Y. 1967)....................................... 34

United States v. Galante, 298 F.2d 72

(2d Cir. 1962)............................................ 58,109,135,1

United States v. Gougis, 374 F.2d 758

(7th Cir. 1 9 6 7 ) ....................................... 39

United States v. Grleen, 176 F.2d 169

(2d Cir.) cert, denied, 338 U.S. 851 (1949)......... 138

X l l l

United States v. Hall, 176 F.2d 163 (2d Cir- 1949) . . 101,103

United States v. Harris, 367 F.2d 826 (2d Cir.1966). . 61

United States v. Johnson, 323 U.S. 273 (1944)......... 67

United States v. Johnston, 318 F .2d 288 (6 th Cir.

1 9 6 3 ) .................................................. 32

United States v. Jones, 369 F.2d 217

(7th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ....................................... 33

United States v. Landes, 97 F .2d 378 (2d Cir. 1938). . 173

United States v. McMann, 386 F.2d 611 (2d Cir.1967). . 33

United States v. Maragas, 390 F.2d 88

(6 th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ....................................... 172,173

United States v. Maresca, 266 Fed. 713 (S.D. N.Y.

1 9 2 0 ) ................................................. 156

United States v. Maroney, 220 F.Supp. 801

(W.D. Pa. 1 9 6 3 ) ...................................... 43

United States v. Mesarosh, 116 F.Supp.

345 (W.D. Pa. 1 9 5 3 ) ..................................... 34,43

United States v. Midstate Horticultural Co.,

306 U.S. 161 (1939)..................................... 66,76

United States v. Mitchell, 354 F.2d 767

(2d Cir. 1966) ................................... 32

United States v. Mitchell, 138 F.2d 831

(2d Cir. 1943)................................... 47

United States v. Pace, 371 F .2d 810

(2d Cir. 1967) ....................................... 14,90,104

United States v. Piccolo, 395 F.Supp. 955

(D. Conn. 1 9 6 7 ) ....................................... 138

United States v. Plattner, 330 F.2d 271,

(2d Cir. 1964)......................................... 40,44,45,46,4

United States v. Private Brands, Inc.,

250 F . 2d 554 (2d Cir. 1 9 5 7 ) .......................... 41

United States v. Rinieri, 308 F.2d 24 (2d Cir.1962)

cert, denied, 371 U.S. 935 (1962)................... 138

Page

United States v. Gutterman, 147 F.2d 540

(2d Cir. 1945) ....................................... 41

xiv

United States v. Rosenberg, 157 F.Supp.

654 (E.D. Pa. 1958), aff'd, 257 F.2d

760 (3d Cir. 1958), aff'd. 360 U.S. 367 (1959). . . . 33

United States v. Sacher, 182 F.2d 416

(2d Cir. 1950), aff'd, 343 U.S. 1, (1952)........... 7,75,106,116

United States v. Schiffer, 351 F.2d 91

(6 th Cir. 1965), cert. denied, 384

U.S. 1003 (1966) ..................................... 74,109,126,13

United States v. Sopher, 347 F.2d 415

(7th Cir. 1 9 6 5 ) ....................................... 173

United States v. Sternmah, 415 F.2d

1165 (6 th Cir. 1969) ................................ 138

United States v. Temple, 349 F.2d 116 (4th Cir. 1965). 91

United States v. Thompson, 214 F.2d 545 (2d Cir.)

cert. denied, 348 U.S. 41 (1954)...................... 57

United States v. Universal C.I.T.

Credit Corp., 344 U.S. 218 (1952) .................... 66,67,72,76

United States ex rel Robson v. Malone, 412

F . 2d 848 (7th Cir. 1969) ............................ 14,104,115,13

174

Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178 (1957)......... 155

White v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 59 (1963)................. 52

Widger v. United States, 244 F.2d 103

(5th Cir. 1 9 5 7 ) ....................................... 108,116

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949)............. 113

Wilson v. United States, 369 F.2d 198 (D.C. Cir. 1966) 154

Wong Gim Ying v. United States, 231

E 2d 776 (D.C. Cir. 1956) ........................ 138

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962)................. 75

Yates v. United States, 355 U.S. 66 (1957)........... 67,71,73,75,1

173

Yates v. United States, 227 F .2d 848 (9th Cir.1955). . 59,137,147

Page

xv

LA. REV. STAT. § 15:11 (1951)

22 Stat. 3 .................

S tatutes:

2 u . s . c . § 192 .

2 u . s . c . § 194 .

10 u . s . c . § 848 .

12 u . s . c . § 592 .

18 u . s . c . § 88 .

18 u . s . c . § I l l .

18 u . s . c . § 254 .

18 u . s . c . § 401 .

18 U.S.C. § 1114

18 U.S.C. § 1282

18 U.S.C. § 1503

18 U.S.C. § 1504

18 u . s . c . § 1506

18 u . s . c . § 1508

18 u . s . c . § 1621

18 u . s . c . § 1622

18 u . s . c . § 2421

22 u . s . c . § 703 .

28 u . s . c . § 519 .

28 u . s . c . § 547 .

28 u . s . c . § 1654

68

67

154

154

71

67

66

139

66

5,49,55,66,

67,68,69,80,

71,72,73,76,

119,131,135,138

140,151,167

139

66

139

139

139

139

139

139

66

71

154

154

Page

40

xvi

29 U.S.C. § 216 66

49 U.S.C. § 4 1 1 ....................................... 66

Other Authorities:

American Bar Association, Canons of Judicial Ethics . 159

American Bar Association, Canons of Professional

E t h i c s ............................................. 156

American Bar Association, Code of Professional

Responsibility ..................................... 156

Anno., Construction of Provision in Federal Criminal

Procedure Rule 42(b) That if Contempt Charges Involve

Disrespect to or Criticism of Judge , He Is Disqual

ified from Presiding at Trial or Hearing Except with

Defendant's Consent, 3 A.L.R. Fed. 420 (1970) . . . 78,79

Anno., Disqualification of Judge in Proceedings to

Punish Contempt, 64 A.L.R.2d 600 (1959) 78

Anno., Right of Defendant in Criminal Case to Conduct

Defense in Person, or to Participate with Counsel,

77 A.L.R.2d 1238 (1961)............................ 41,42

Anno., 99 L.Ed. 19 (1955)............................ 89

Anno., 3 L.Ed.2d 1855 (1959) ........................ 89

IV BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES ............................. 65

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4 3 ................. 124

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4 6 ................. 120

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 42 ............... 2,5,61,78,97,

98,99,101,103,

104,105,106,10E

112,114,115,152

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 4 4 ............... 40

Frankfurter & Corcoran, Petty Federal Offenses and

the Constitutional Guaranty of Trial by Jury, 39

HARV. L. REV. 917 (1926) .......................... 63,65

Page

29 U.S.C. § 2 1 5 ...................................... 66

xvii

Page

General Rules of the Northern District of Illinois . . 21,36

GOLDFARB, THE CONTEMPT POWER (1963) ................. 5 5

8A MOORE, FEDERAL PRACTICE ............................ I7 3

Note, Contempt Proceedings: Disgualification of Judge

for Bias, 44 CALIF. L. REV. 425 (1956)............. 89

Note, Procedures for Trying Contempts in the Federal

Courts, 73 HARV. L. REV. 353 (1959) ............... 57,89

Note, The Right of an Accused to Proceed Without

Counsel, 49 MINN. L. REV. 1133 (1965) ............. 47

Note, 37 CORN. L. Q. 795 (1952) ...................... 102,103

Note, 1966 DUKE L. J. 8 1 4 ............................ 103

Note, 1967 DUKE L. J. 632 ............................ 56,57,59

Note, 63 MICH. L. REV. 700 (1965) ................... 59

Note, 2 STAN. L. REV. 763 (1950)...................... 102,103

Note, 109 U. PA. L. REV. 67 (1960)................... 1 3 9

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (Hon. Otto Kerner. Chairman^ (1968) 7~. . 172

3 STEPHEN, A HISTORY OF THE CRIMINAL LAW OF ENGLAND . 65

TIME Magazine, April 6 , 1970 .......................... 171,172

Webster's New International Dictionary, 2d Ed......... 68

3 WRIGHT, Federal Practice and Procedure, Criminal

(1969) ................................................ 39,102,103

(

Statement of the Issue! Presented for Review

1. Whether the: court belc

right to counsel of his choic

to self-representation, and v

1 wrongfully denied appellant's

2 or, alternatively, his right

lether his resulting contempt

convictions must therefore be! reversed.

2. Whether the court belc

a jury trial because the coni

suited in an aggregate four-}

misconduct, and (c) constitut

/ wrongfully denied appellant

jmptuous acts charged (a) re-

jar sentence, (b) involved serious

■id at most a single violation

of 18 U.S.C. §401(1).

3. Whether appellant was j

charges heard by another judgl

I

out of a personal confrontatit

involved personal, critical a?j.

that judge, and he found no ntj

tion; and (b) the trial judge

ntitled to have his contempt

where (a) the charges arose

n with the trial judge,

d derogatory comments about

cessity for instant adjudica-

became personally embroiled.

4. Whether the trial court erred in proceeding under

F.R.Cr.P. 42(a) rather than 42(b) where (a) there was no

necessity for instant adjudication, and (b) summary imposi

tion of punishment was prejudicial.

5. Whether appellant was at least entitled to some

rudimentary hearing on the issues of guilt and penalty,

xix

including representation by retained counsel.

6 . Whether appellant's conduct constituted the crime of

contempt as defined by 18 U.S.C. § 401.

7. Whether the court's failure adequately to warn appel

lant that his conduct subjected him to criminal contempt

penalties requires reversal.

8 . Whether misconduct by the trial court and prosecuting

attorneys requires reversal in the interests of justice.

xx

1I

j

i

i

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 18246

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee,

v.

BOBBY G. SEALE,

Appellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Illinois

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

March 20, 1969, appellant and seven other persons were

indicted for violating the federal anti-riot statute, 18 U.S.C.

§ 2101, and for conspiracy to violate that statute, 18 U.S.C.

§ 371. The indictments charged that violations had occurred

at the time of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in

Chicago. (Record on Appeal, Item No. 2) United States v .

-j3ellinger> 69 CR 180. April 9, 1969, defendants were arraigned

before the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Illinois. Trial was set for September 24, 1969

(Record on Appeal, Item No. 7), and was never thereafter

continued.

Appellant moved prior to trial for a continuance on the

ground that his chosen attorney, Charles R. Garry, could not

attend a September 24 trial but these motions were denied and

trial began on the date scheduled. Appellant again moved at

the beginning of trial for a continuance so that he could be

represented by Garry, and requested alternatively that he be

allowed to represent himself, specifically firing his attorneys

of record other than Garry. The court denied appellant a

continuance, and the right to represent himself. Trial

proceeded without any defense being presented on appellant's

behalf.

November 5, 1969, acting under Rule 42(a) of the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure, the trial court summarily adjudged

appellant guilty of 16 acts of contempt, all arising out of

his objections to Garry's absence and his attempts to represent

himself during trial. The court then imposed 16 consecutive

three-month terms, a total of four years. Simultaneously the

court on its own motion declared a mistrial as to appellant

„ . vand severed his trial from that of his co-defendants

1/ The court fixed April 23, 1970, for appellant's second trial

on the riot and conspiracy charges, before the same district judge

that date was eventually postponed at the government's request and

over appellant's objection.

2

(TR 5409-5484).

Details of various aspects of the proceedings below

appear in connection with the relevant arguments, infra.

Notice of appeal from the trial court's judgment

and order was timely filed November 6 , 1969 (Record on

Appeal, Item No. 62).

2/

2 / Since a deferred appendix is being filed pursuant to

Rule 30(c) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, all

citations are to pages of the parts of the record involved.

Proceedings on September 24 and 25 consisted of pre-trial

motions and jury selection. The trial began on September 26

and its transcript is separately paginated. Hereinafter we

shall refer to the September 24 and 25 transcript as TR*,

and to the trial transcript as TR. Presentation of appellant's

September 26 motion for a continuance took place prior to

trial proceedings that day and its transcript is also

separately paginated. Hereinafter it shall be referred to as Sept. 26 TR.

3

Summary of Argument

Argument I, infra pp. 17-53, argues that the court

wrongfully denied appellant the right to counsel of his choice

and, alternatively, the right to represent himself. Appellant

contends that contempt convictions resulting from a trial at

which he was denied the fundamental right to present a defense

and denied the advice of counsel regarding the propriety of

his conduct during trial, must be reversed. Arguments II - VIII

require reversal of the contempt convictions

regardless of whether appellant was wrongfully denied his right

to counsel of his choice or to self-representation. But since

appellant's Sixth Amendment claims were central to the entire

controversy between him and the court, and the resulting

contempt convictions, the court's error in this respect gives

added force to all of appellant's arguments.

Argument II, infra pp. 54-76, contends that reversal is

required on the ground that appellant was wrongfully denied

his right to a jury trial because: (A) the court imposed an

aggregate term in excess of six months; (B) wholly apart from

the aggregate term imposed, the case involved a serious crime,

in which a jury trial is a matter of right; (C) appellant's

conduct constituted at most a single contempt, for which a term

in excess of six months cannot be imposed without a jury trial.

Arguments III, IV and V contend that appellant's con

victions must be reversed because the court below wrongfully

denied him essential procedural safeguards. In Argument III,

4

infra pp. 77-96, appellant urges that he was entitled to a

hearing before another judge because: (A) the contempt charges

arose out of a personal confrontation with the trial court

under circumstances with an enormous potential for bias; and

(B) the trial judge was actively embroiled in a bitter clash

with appellant throughout the trial. Argument IV, infra

pp. 97-111, contends that the court erred in proceeding under

Rule 42(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure rather

than Rule 42(b) because: (A) there was no necessity for instant

adjudication; and (b ) summary imposition of punishment for prior

acts of misconduct was prejudicial. Argument V, infra pp. 112-18

contends that, even assuming it was proper to proceed under

Rule 4 2 (a), appellant was at least entitled to some hearing

and it was error to deny him any opportunity to present evidence

or argument going to guilt, and an adequate sentencing hearing,

including the assistance of retained counsel.

Arguments VI, VII, and VIII contend that appellant is

entitled to reversal and a dismissal of the charges. in

Argument VI, infra pp. 119-36, appellant urges that his conduct

did not constitute the crime of contempt as defined by 18 U.S.C.

§ 401(1). Argument VII, infra pp. 137-51, urges that the

court's failure adequately to warn appellant that his conduct

subjected him to criminal contempt penalties requires reversal.

And in Argument VIII, infra pp. 152-75, appellant argues that

5

misconduct on the part of the trial court and prosecuting

attorneys requires reversal in the interest of justice.

Finally, appellant directs the court's attention to

those facts that are within his knowledge concerning

electronic surveillance relevant to the contempt conviction.

(IX, infra pp. 176-77)

6

ARGUMENT

Introduction

One initial point is basic to an understanding of the

issues raised by this appeal. The occurrences in the dis

trict court during the trial of United States v. Dellinger,

for which appellant was convicted on 16 specifications of

contempt and sentenced to an astounding four years in prison,

are the subject of a serious factual dispute. That dispute

relates, not to the stenographically reported verbal exchanges

which comprise the record, but to their basic interpretation.

Put simply, the district court took the view, and made

the formal finding, that appellant Bobby Seale engaged in a

course of conduct deliberately designed to obstruct and defeat

the administration of justice and to "sabotage the function

ing of the Federal Judicial System." (TR 5411, 5413) In the

trial court's opinion, appellant was guilty not simply of the

16 specified incidents that disturbed his trial. He was guilty

of something far more sinister and serious — an unspecified

general specification of contempt of the sort reversed by the

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in United States v. Sacher,'

3/ The Second Circuit reversed Specification I which charged

"a wilful, deliberate and concerted effort to delay and obstruct

the trial." Judge Frank noted that since this charged a conspiracy

essentially, out-of-court evidence was relevant and procedural

regularity essential. (182 F.2d at 455, Frank, J. concurring;

see also 182 F.2d at 423, 430).

7

182 F . 2d 416 (2nd Cir. 1950), aff'd , 343 U.S. 1 (1952), involving

a purposeful and calculated attack on the court and the entire

judicial system.

In diametric opposition to this view is appellant's own

understanding of what happened at his trial. Again put

simply, Bobby Seale, a black man facing a serious criminal charge,

was inexplicably denied the one attorney whom he trusted,

wanted and had chosen to represent him: Charles Garry. Instead

he was told by the court that another attorney, William Kunstler,

whom he had not chosen and did not want, represented him. He

objected vigorously, first asking for Garry and then asking,

in Garry's absence, to represent himself. These requests were

refused and, again and again, the same scene was repeated:

Seale objecting to Kunstler's representation, demanding his

right to Garry or to represent himself; the court insisting

that Kunstler was his lawyer; Seale protesting that Kunstler

was not his lawyer; the court stifling him without explaining

that his record was made; Seale therefore protesting once

more at the next point where, in his layman's judgment, he had

to do so in order to protect his rights.

These two opposing points of view are dramatically

illustrated by the following exchanges:

8

THE COURT: As I think everyone who has attended

the various sessions of this trial must if he is

fair understand, the Court has done its best to

prevent or [not] to have repeated efforts to delay

and obstruct this trial which I think have been

made for the purpose of causing such disorder an

confusion as would prevent a verdict. • • ■conru ̂ ̂ ̂ fchat the actS/ statements

and’conduct of the defendant Seale which I shall

specify here each constitute a separate contemp

of this Court; that each constituted a deliberate

and wilful attack upon the administration of justice

in an attempt to sabotage the functioning of the

federal judicial system. , .MR. SEALE: That is a lie. I stood up and spoke

behalf of myself. . . - and made motions and re

quests • V ght tQ speak and make requests and

make arguments to demonstrate the fact I want o

cross examine. When you say I disrupt, I aye .

never tried to strike anybody, I have never tried

to hit anybody. I have never. You know that.

(TR 5409, 5411, 5412-13)

THE COURT: You may speak to the matters I have

discussed here today, matters dealing with your

contemptuous conduct. The^law obligates me to

call on you to speak at this time.

MR. SEALE: About what? About the fact that I

want a right to defend myself? That's all I am

speaking about.

THE COURT: No, about possible punishment for con

tempt of this court. .

MR. SEALE: Punishment? . . . I have n°thin9about that. I have something to say about the tact

that I want to defend myself still. I want my

rights, to be able to stand up and cross-examine

the witnesses. I want that, so I don't know what

you're talking about.THE COURT: I have tried to make it clear.

MR. SEALE: All you make clear to me is that you

don't want me, you refuse to let me, you will not

qo by my persuasion, or my arguments, my motions, my

requests to be, to the extent of even having to

9

shout loud enough to get on that record for that

record so that they can hear me half the time.

You don't want to listen to me. You don't want

to let a man stand up, contend to you that that

man is not my lawyer, show you and point out to

you that fact, in fact, made motions and told you

that I fired the man.

And to stand up here and say, "Look, I have the

right to defend myself," continuously over and over,

even to the point just recently on Friday you

recognized that I did have only one lawyer by letting

this man and Thomas Hayden to go and to talk to

Charles R. Garry to see about coming out here for

me, which begin to show me that I was beginning to

persuade you to do something, at least allow some

body to investigate my situation. Now what are you

talking about? Now all of a sudden on the record?

MR. SEALE: Well, the first thing, I'm not in no

contempt of court. I know that. I know that I as

a person and a human being have the right to stand

up in a court and use his constitutional right to

speak in behalf of his constitutional rights. That

is very clear, I hope. That's all I have to say.

I still want to cross-examine the witnesses, I make

those requests. I make my motions, and I make those

requests, and I will continue to make those requests,

hoping that once in one way along this trial, you

will recognize my rights as a human being . . .

(TR 5476-79)

Now obviously the court punished appellant with a four-year

prison term — without notice, hearing or counsel — in accordance

with its view that he was guilty of extremely serious misconduct

amounting to an intentional assault upon the administration of

justice. But in appellant's view he was guilty of nothing more

than attempting to assert his claims to be represented by Charles

Garry or, alternatively, to represent himself, preserve his

objections to the denial of those claims, and protest the

fact that his trial proceeded without any defense whatsoever

, . 4/being presented on his behalf.

4/ See, e_._g. , the following exchanges, included in the incidents cited by the court as contemptuous:

MR. SEALE: If you let me defend myself, you could

instruct me on the proceedings that I can act, but I have to just —

THE COURT: You will have to be quiet.

MR. SEALE: All I have to do is clear the record.

I want to defend myself in behalf of my constitutional rights.

THE COURT: Let the record show that the defendant

Seale has refused to be quiet in the face of

the admonition and direction of the Court.

MR. SEALE: Let the record show that Bobby Seale

speaks out in behalf of his constitutional rights,

his right to defend himself, his right to speak in

behalf of himself in this courtroom.

(Incident 7) (TR 3642)

MR. SEALE: I object to that because my lawyer

is not here. I have been denied my right to defend

myself in this courtroom. I object to this man's

testimony against me because I have not been allowed

my constitutional rights.

THE COURT: I repeat to you, sir, you have a lawyer.

Your lawyer is Mr. Kunstler, who represented to the

Court that he represents you.

MR. SEALE: He does not represent me.

THE COURT: And he has filed an appearance. . . .

MR. KUNSTLER: May I say I have withdrawn or

attempted to withdraw.

MR. SEALE: The defense filed a motion before the

jury ever heard any evidence, and I object to that testimony.

THE COURT: For your information, sir, I do not hear

parties to a case who are not represented by lawyers.

You are represented by a lawyer.

11

We submit that the record is completely consistent with

this latter view. Appellant, an untutored layman, who was

4/ (Cont'd)

MR. SEALE: I am not represented by a lawyer. I am

not represented by Charles Garry for your information.

THE MARSHALL: Sit down, Mr. Seale.

THE COURT: Now you just keep on this way and —

MR. SEALE: Keep on what? Keep on what?

THE COURT: Just sit down.

MR. SEALE: Keep on what? Keep on getting denied

my constitutional rights?

THE COURT: Will you be quiet?

MR. SEALE: I object to that man's — can't I object

to that man there sitting up there testifying against

me and my constitutional rights denied to my lawyer

being here?

(Incident 9) (TR 4342-44)

MR. SEALE: If a witness is on the stand and testi

fies against me and I stand up and speak out in

behalf of my right to have my lawyer and to defend

myself and you deny me that, I have a right to make

those requests. I have a right to make those demands

on my constitutional rights.

(Incident 11) (TR 4641)

THE COURT: Now I want to tell you, Mr. Seale, again —

I thought you were going to adhere to my directions.

You sat there and did not during this afternoon

intrude into the proceedings in an improper way.

MR. SEALE: I never intruded until it was the proper

time for me to ask and request and demand that I

have a right to defend myself and I have a right to

cross-examine the witness. I sit through other cross-

examinations and after the cross-examinations were

over, I request, demanded my right to cross-examine

the witness, and in turn demanded my right to defend

myself, since you cannot sit up here — you cannot

sit up here and continue to deny me my constitutional

rights to cross-examine the witness, my constitutional

right to defend myself. I sit throughout other cross-

examinations, I never said anything, and I am not

attempting to disrupt this trial. I am attempting

to get my rights to defend myself recognized by you.

(Incident 15) (TR 4932-33) (emphasis added)

12

in fact receiving no representation, was simply attempting to

protect his interests as best he knew how. Faced with a trial

court which, instead of instructing him that he had raised

5/objections and that they would be preserved for appeal,

insisted that he was properly represented, it is understandable

that appellant would insist on his rights and protest their

denial as best he knew how. For this reason we believe that

the record fails to support the judgments of contempt,

and appellant's conviction must therefore be vacated.

(Arguments I, VI-VIII, infra)

But regardless of whether he is entitled to such relief,

it is clear that the procedures by which the conflict between

appellant's view and the radically different view of the court

was resolved, violated his rights. Precisely because two

such conflicting views of the facts were entertainable, it was

essential that fair and regular procedures be used to determine

appellant's guilt. The procedures used below were markedly

deficient under present-day standards for the trial of serious

contempts in the federal courts, and for this reason also

reversal is required. (Arguments II-V, infra)

5/ Indeed the government finally urged the court to tell

Mr. Seale that his Sixth Amendment claims were properly preserved

for appeal. (TR 4746) However this was not until the twenty-fourth

day of trial, after thirteen of the sixteen allegedly contemptuous

incidents had occurred.

13

For in recent years there has been gradual recognition

of the need to restrict both the substantive scope of

§yoffenses subject to the contempt power and the manner in

2/which that power is exercised. This development has culminated

in a number of recent decisions by the United States Supreme

Court, most notably Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1968) and

Harris v. United States, 382 U.S. 162 (1965). These decisions

, 8/signal a new approach to the law of contempt, for they

9/ 10/

have overruled or undermined previous cases, and vindicated

those who have long condemned the essentially despotic nature

of the traditional power of judges to summarily punish for12/criminal contempt.

6/ See, e .g ., Nye v. United States, 313 U.S. 33, 44-48 (1940);

In re Michael, 326 U.S. 224 (1945); Gammer v. United States. 350

U.S. 399, 407-08 (1956); Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941).

7/ See generally Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194, 202-06 (1968).

8/ See e.g., United States v. Pace, 371 F.2d 810, 811 (2nd Cir.

1967); see also United States ex rel Robson v. Malone, 412 F.2d

848 (7th Cir. 1969).

9 / E.g., Bloom, supra, overruled Green v. United States, 356

U.S. 165 (1958); Harris, supra, overruled Brown v. United States,

359 U.S. 41 (1959),

10/ Thus while Sacher v. United States. 343 U.S. 1 (1952), has

never been specifically overruled, we will argue infra that it

has been effectively emasculated.

1 1 / See especially Mr. Justice Black's dissent in Green v .

United States, supra n. 9. See also

State ex rel Attorney General v. Circuit Court. 97 Wis. 1, 8,

72 N.W. 193, 194-95 (1897),, characterizing the power of a judge

to punish summarily for criminal contempt as "perhaps, nearest akin

to despotic power of any power existing under our form of government.

14

In Bloom v . Illinois, supra, the Supreme Court finally

brought the criminal contempt power within the bounds of our

traditional criminal jurisprudence in ruling that "criminal

contempt is a crime in the ordinary sense . . .," and "con

victions for criminal contempt, not infrequently resulting

in extremely serious penalties . . ., are indistinguishable

from those obtained under ordinary criminal laws" (391 U.S.

at 201, 207-08). The Court concluded that the criminal con-

temnor must therefore be accorded the traditional procedural

12/protections of our system of criminal justice.

The trial judge's action in the instant case represents

an extreme example of the potential for abuse inherent in the

power to imprison for contempt. Appellant was sentenced to

four years imprisonment at the conclusion of a summary pro

ceeding, at which he was accorded none of the traditional

12/

We cannot say that the need to further

respect for judges and courts is entitled

to more consideration than the interest of

the individual not to be subjected to serious

criminal punishment without the benefit of all

the procedural protections worked out carefully

over the years and deemed fundamental to our

system of justice. Genuine respect, which

alone can lend true dignity to our judicial

establishment, will be engendered, not by the

fear of unlimited authority, but by the firm

administration of the law through those

institutionalized procedures which have been

worked out over the centuries. (391 U.S. at 208)

Bloom overruled a 150-year line of authority which had held

that an individual charged with contempt was not constitutionally entitled to a jury trial.

15

procedural safeguards of the criminal law for acts arising

out of a personal clash between him and the man who then

purported to act as prosecutor, judge and fact-finder. This

is completely inconsistent with the spirit and philosophy of

Bloom v. Illinois, supra, and can only erode the respect for

the judicial system which the contempt power purports to serve.

16

I

THE COURT'S WRONGFUL DENIAL OF DEFENDANT

SEALE'S RIGHT TO COUNSEL OF HIS CHOICE OR,

ALTERNATIVELY, HIS RIGHT TO REPRESENT HIM

SELF, REQUIRES REVERSAL OF THE CONTEMPT

CONVICTION

THE COURT:

MR. SEALE:

THE COURT:

MR. SEALE:

THE COURT:

Mr. Seale, you have a right to speak

now, I will hear you.

For myself?

In your own behalf, yes.

How come I couldn't speak before?

This is a special occasion. (TR 5475)

(After Seale was adjudged guilty of

contempt)

Appellant's claim that he was entitled to be represented

by Charles Garry or, at the least, to present his own defense,

was central to the entire controversy between Seale and the

court and virtually all of the resulting 16 contempt convictions.

It is our contention in Arguments II - VIII, infra, that the

contempt convictions must be reversed regardless of whether

Seale or the court was right on this basic issue. But there

can be little question that the court erred in denying defendant

Seale opportunity to present a defense either through retained

counsel of his choice or through self-representation. This

action by the court, in violation of Seale's constitutional

and statutory rights, gives added support to Arguments II -

VIII and also constitutes an independent ground for reversal

(IB, infra pp. 49-53).

17

A. THE COURT WRONGFULLY DENIED DEFENDANT SEALE'S

RIGHT TO COUNSEL OF HIS CHOICE OR, ALTERNATIVELY,

HIS RIGHT TO REPRESENT HIMSELF.

Facts

August 27, 1969 the defendants in the case of United

States v. Dellinger moved for a continuance on the ground that

attorneys Charles Garry and William Kunstler, because of other

trial engagements, would be unable to participate if the trial

took place September 24, alleging that their participation was

"absolutely essential to assure the defendants herein adequate

representation at their trial." Garry's attached affidavit

alleged specifically that (1) he had been designated chief trial

counsel by the defendants, and (2) he was attorney of record for13/

defendant Seale "whom I have represented for several years."

This motion was denied that same day by the trial court. (Record

on Appeal, Items No. 26, 28)

September 9, 1969 the defense presented a renewed emergency

motion for a continuance until November 15, 1969 on the ground

that Garry had developed a serious medical condition requiring

immediate surgery which would make it impossible for him to

13/ The attached affidavit of attorney Leonard Weinglass

alleged that Seale's incarceration in San Francisco on a

Connecticut murder charge had made it "virtually impossible

for . . . [Garry] to represent his client adequately in con

nection with the charges against [him] pending before this

Court," and had prevented Seale from "indispensable consulta

tion with his co-defendants."

18

participate in a trial commencing September 24. Supporting

affidavits by Garry and Seale alleged that Seale had selected

Garry as his trial attorney and refused to go to trial with

out him, requesting a severance if necessary, because Garry

had demonstrated "unique professional ability, particularly

in courtroom strategy and tactics, to provide proper and

15/

adequate defense to a black militant charged with crime."

14/

14/ Record on Appeal, Item No. 29. Supporting affidavits by

Garry and his physicians gave details of his medical condition

indicating that he was taken seriously ill and hospitalized

August 25, 1969 for a gall bladder condition requiring surgical

removal of the bladder at the earliest possible date, and that

the required hospitalization and recuperation would prevent him

from trying any cases prior to November 15, 1969.

15/ Garry's affidavit alleged that Seale "insists that I defend

him upon the indictment herein, and I am willing and able to do

so, on or after Nov. 15, 1969;" and consequently was moving "for

a continuance of trial, or alternatively, for severance and

continuance." Seale's supporting affidavit explained why Garry

was his chosen trial attorney:

My attorney in the . . . . [instant case],

and generally, is CHARLES R. GARRY of San

Francisco, California, whom I have carefully

selected and chosen as my attorney based on

extensive valuable experience.

* * * *

. . . Many of my colleagues in the Black

Panther Party, and I, have been subjected to

intense harrassment by the white racist prose

cuting authorities throughout the country. . . .

Defense against these attacks has required able,

experienced and imaginative counsel. Charles R.

Garry has demonstrated to me an unique professional

ability, particularly in courtroom strategy and

tactics, to provide proper and adequate defense to

a black militant charged with crime.

Charles R. Garry is my attorney and I cannot go

19

The trial court denied the renewed motion for continuance

(Record on Appeal, Item No. 30) noting that Seale had "of

record for him," attorneys Michael Tigar, Irving Birnbaum

and Stanley Bass, in addition to Garry. The court held that

absence of "lead counsel" due to illness did not necessitate

a continuance until his recovery and that, where a defendant

had some counsel, there was no need to grant him opportunity

to secure other counsel. The court deemed irrelevant the fact

that such other counsel had been engaged only for pre-trial

motions stating: "We don't have limited appearances in

criminal cases." Garry stated that if defendant Seale were

ordered to appear on September 24 he would be "without counsel

16/

at that time." (Sept. 9 Hearing, TR 60, 61, 69)

15/ (Cont'd)

to trial, nor be put on trial, on the indictment

herein until my said attorney is physically able

to appear and to defend me.

A supporting affidavit by Rennard C. Davis alleged that all the

defendants had selected Garry as chief trial counsel.

16/ Garry underwent surgery during the last week of September,

was hospitalized or confined to his home for many weeks there

after, and never appeared at the trial.

20

On or about September 15 appellant uappellant, who for several

months had been incarcerated in San

n San Francisco on another

matter, was transferred bv car e

under th CaUfornia to Chicagounder the supervision of federal • ■

almost a week- thro h orities. The trip took

his ' thr°UghOUt aPPeHant was out of touch with

counsel. (t r 3137- 38)

“ • « » ■ .. Co

co beale m the lock-nn ̂ ,

P ' lled an aPPearance for Seale n *-•

specifically on the form that hi n°tlng

q his appearance was "pro tern "September 24 t-ho ^ ^— i§m*' the daY scheduled for trial vria1' Kunstler filed

another appearance. (Record on Appea! It^PPeai, items No. 31 3

But the record makes clear a 1es clear, although the issue was ■

xnto by the trial court that Sea, “ qUlred

or anv la "eV6r authoriaed Kunstleror any lawyer other than Garry to ™

rry' to represent him at trial,

the opening of the proceedings September 24 prior

to the selection or ' prior

filed an a 3 indicated that he had

n aPPearance for Seale as well as all „

that he and Weinglass 6 °ther defenda*ts,

d _ „ COndUCt the defense. but that a n

defendants objected on the ground of G a r r y s ab O v r y s absence. (t r *

Kunstler's repeated rmi f------ £aaa§^ - ^ 2 T J a ch defendant

only for pre-triai motions. ( T R ^ S ^ h“d been

21

allowed to speak for the record as to why he felt his right

to counsel was thereby denied were refused by the court.

When Weinglass contended that defendant Seale was in fact not

represented at all, the court refused even to hear his argument.

(TR * 4-6, 14-16, 24)

The morning of September 26, after the jury had been

selected but prior to opening statements and to the swearing

of any witness, Seale filed a pro se motion requesting a con

tinuance on the grounds that he had been denied the right to

speak in his own behalf and denied counsel of his choice,

Garry; and specifically firing all other attorneys purporting

18/

to represent him. Following Seale's presentation of the motion * I

18/ The handwritten motion reads as follows (spelling and

grammar as in the original):

. . . I, Bobby G. Seale being one of the

defendants of eight has been, by denied motion,

the right to speak out in my behalf where my

constitutional right to have "Legal council of

my choice who is effective", namely, Attorney

Charles R. Garry who is on record in this court

as my defense council that I have made agreement

with by my choice only that he will assist me in

my defense during this trial.

I submit to Judge Julius Hoffman that the

trial be postponed until a later date where

I, Bobby G. Seale, can have the "legal council

of my choice who is effective", Attorney Charles

R. Garry and if my constitutional rights are not

respected by this court then other lawyers on

record here representing me, except Charles R.

Garry, do not speak for me or represent me as of

this date, 9-26-69. I fire them now until

Charles R. Garry can be made available as chief

council in this trial of so-called "conspiracy

to riot" and in fact be my legal council of

22

and another request for continuance by Kunstler on behalf

of all defendants, the court denied the motion without making

any inquiry into the relevant underlying facts. When Seale

then complained that his constitutional rights were being

denied he was told he could not speak out at all -- that he

could speak only through his attorneys. (Sept. 26 TR 19)

When Attorneys Kunstler and Weinglass concluded their

opening statements to the jury, Seale requested an opportunity

to make his own opening statement. Asked by the court who his

lawyer was, he replied Charles R. Garry. Without further inquiry,

the court denied Seale's request on the sole ground that Kunstler

had filed an appearance for him. Kunstler refused to make an

opening statement on Seale's behalf, because of Seale's posi

tion that Garry was his lawyer. (TR 76-78)

The court subsequently consented to the withdrawal of

attorneys Tigar and Bass, on September 29 and 30

18/ (Cont'd)

choice who is effective" in assisting me in

my defense. The only defense attorney I know

of who can defend me and be effective is

Charles R. Garry who is presently my attorney

on record in this court. . . .

/s/ BOBBY SEALE Chairman Black Panther Party.

(Record on Appeal, Item No. 47)

23

respectively. (Birnbaum was later excused from daily

attendance. TR 3022-35)

September 30, attorneys Kunstler and Birnbaum again made

it clear to the court that Seale had fired them and that they

could not under those circumstances represent him. That

afternoon, in chambers and out of the presence of the defendants,

attorneys Kunstler and Weinglass again informed the court that

Seale was not represented since he had fired Kunstler, arguing

that Seale ought be present since he was pro se. Kunstler

alleged that the only reason he and Birnbaum had not formally

withdrawn was so that they could provide Seale some access to

the outside world. The court indicated doubt as to whether

a defendant could fire his lawyer once trial had begun and

concluded the discussion, still in Seale's absence, by saying

it regarded Kunstler and Birnbaum as Seale's lawyers. (TR 425-

29)

October 2, 1969, in response to Seale's request for law

books so that he could conduct his own defense, the

court said that a defendant had no right to fire his attorney

19/

jL£/ The court at first refused to consent to Tigar's withdrawal

(or to that of attorneys Gerald Lefcourt, Michael Kennedy and

Dennis Roberts) without an admission by defendants that they were

represented. (TR 147-56) Only after the government said it

would not oppose withdrawal did the court permit it without

insisting on a waiver by defendants of Sixth Amendment objections

to Garry's absence. (TR 158-70)

September 30, when attorney Bass moved to withdraw and the

defendants were asked whether they objected, Seale said that he

had "fired all of these lawyers a long time ago" and repeated

his claim that he was represented only by Garry. (TR 391-92)

24

"in the midst of a trial." Seale literally pleaded to be

allowed to speak to this issue but was denied any opportunity

to do so. (TR 694-98)

Throughout the trial, until the declaration of mistrial,

this pattern was repeated. Seale objected to being tried in

the absence of his chosen counsel and attempted to represent

himself at points where some defense was clearly essential;

the court denied him this right and ruled that he was repre

sented by Kunstler on the sole ground that he had filed an

appearance -- without ever inquiring of Seale, or Kunstler,

whether Seale had authorized the appearance and if so with

what intention, and without allowing Seale to make any state

ment regarding the issue. Despite the court's attempts to

silence Seale, and to coerce a confession that he was properly

represented, it became evident that Seale had always intended

Garry to be his trial attorney, and had never agreed to trial

representation by any other attorney in Garry's absence,

20/

20/ Tr 696. Birnbaum repeated his claim that he had been

engaged only as local counsel and further stated that Seale

had refused to consult with him. Kunstler again stated that

his representation had been limited to providing Seale access

to the outside world. (TR 695-98)

25

or consulted with any other attorney regarding his IVdefense.

22/ Thus on October 8 Seale objected to a prosecution witness'

testimony involving him on the ground that Garry was not present*

The court silenced the objection noting that Kunstler had filed

an appearance. (TR 1409-10; see also TR 1486-88) When Seale

claimed that Kunstler was not his lawyer,

the court simply warned Kunstler that

he could be punished for filing unauthorized appearances.

Kunstler made it clear that the reason he had initially filed

an appearance was because he was not allowed to see Seale until

he did so. (TR 1489)

October 10, Weinglass said that Seale was unrepresented and

wished to cross-examine a prosecution witness who had testified

against him. The court denied the request. (TR 1993-95)

October 14, Weinglass asked that Seale be allowed to argue in

opposition to a government motion involving Seale. The court

denied the request on the sole ground that Kunstler had filed

an appearance for Seale. Seale argued that he had no lawyer

and that he wanted counsel of his choice and leave to represent

himself. The court refused to hear his argument, noting that

it was the "middle of the trial", (tr 2204-09)

October 20, Birnbaum's motion to be excused from daily

attendance but to continue as local counsel, on the ground that

he had originally filed an appearance on behalf of all defendants

only to satisfy local rules and to perform certain pre-trial

duties, was granted. Seale noted that he had already fired

Birnbaum. (TR 3022-35)

October 21, Seale's request that the court ask a prosecu

tion witness a question for him was refused. Kunstler refused

to cross-examine the witness on Seale's behalf. (TR 3368-69)

October 27, Seale again demanded the right to defend

himself. (TR 4218-21) On October 28, the court denied Seale's

handwritten, pro se motion for a free daily copy of the trial

transcript so that he could help protect his interests and prove

his innocence. (Record on Appeal, Items No. 54, 55; TR 4388)

That same day the court ruled that it would not permit

either Kunstler or Weinglass to go to California to consult

with Garry unless Seale would acknowledge that he was in fact

represented by Kunstler. (TR 4395) October 29, the court

threatened to revoke the bail of those defendants who supported

Seale's position that he had a right to defend himself.

(TR 4726)

Seale's attempts to argue about his right to defend himself

26

October 20 Seale presented another handwritten, pro se

21/ (Cont'd)

resulted finally in his being bound and gagged. (Tr 4752-4766)

October 30, Seale's written objection to the government

refusal to turn over certain materials was rejected on the

ground that the court would hear only from counsel. (TR 4882-

83)

November 3, the court denied a motion made on behalf of

the other defendants for Seale to be allowed to represent

himself, refusing again to allow Seale to be heard on the issue

and relying solely on the fact that Kunstler had entered an

appearance. (TR 5009-14)

November 4, Seale was denied his right to cross-examine

a prosecution witness who had testified against him. (TR 5233)

Seale subsequently objected to testimony regarding him by

another prosecution witness on the grounds that he had no lawyer

and was not allowed to defend himself. When Kunstler later

refused to cross-examine this witness at all on the ground that

his testimony related only to Seale, Seale's attempt to cross-

examine was denied. (TR 5356-8; 5397-5406) Seale told the

court he had never had a pre-trial conference with Kunstler?

that Garry was the only lawyer he had talked to regarding his

case (TR 5357-58); that he was never asked regarding Kunstler*s

filing of an appearance; and that Kunstler had appeared on his

own accord, without any request by or consultation with Seale;

You never asked me: did I ask him to put in

an appearance for me? This man made an appearance

on his own accord. He signed something to come

into jail before this trial started.

I did not ask this man. I did not consult

this man. I do not want this man for my

lawyer at all, and you are forcing me to keep

him .

(TR 5363)

27

motion, claiming as essential to the right to represent

himself the right to cross-examine opposing witnesses, call

witnesses of his own, and make necessary motions, and asking

for release on bail so that he would be able to defend himself

effectively. (Record on Appeal, item No. 50) In support of

this motion, Seale alleged that at his arraignment April 9

it was his understanding that Garry would be his trial

attorney, and that he thought that his other attorneys of