Letter from Lani Guinier to Elise Smith

Correspondence

November 19, 1982

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Elise Smith, 1982. d10d87a3-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/68498be9-f7e1-4a02-b360-211b5fea28c5/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-elise-smith. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

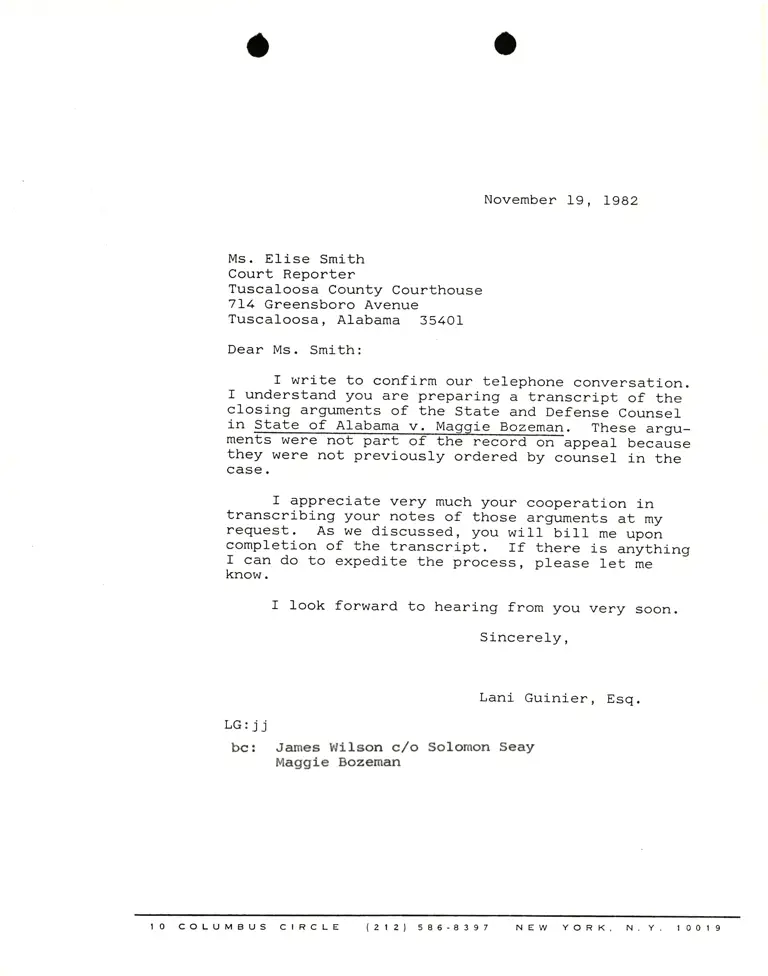

November 19, l9e2

Ms. Elise Smith

Court Reporter

Tuscaloosa County Courthouse

7L4 Greensboro Avenue

Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35401

Dear Ms. Smith:

f write to confirm our telephone conversation.f understand you are preparing a transcript of theclosing arguments of the state and Defense counselin State of Alabama v.- Maggie Bozeman. These argu_

ments were not part of the record-on appeal becausethey were not previously ordered by counsel in the

case.

f appreciate very much your cooperation 1ntranscribing your notes of those arguments at myrequest. As we dlscussed, you will bill me uponcompretion of the transcript. rf there is anytrri-ngI can do to expedite the process, please Iet me

know.

I look forward to hearlng from you very soon.

Sincerely,

LG:jj

bc:

Lani Guinler, Ese.

James Wllson c,/o Solomon Seay

Maggle Bozeman

IO COLUMBUS CIRCLE (ztz) sB5-83s7 NEW YORK, N. Y t0019