Jackson v. Marvell School District Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Marvell School District Reply Brief for Appellants, 1969. c92e2df2-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/68722b36-9b2b-4bb4-a7f1-1a2738b757ab/jackson-v-marvell-school-district-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

*

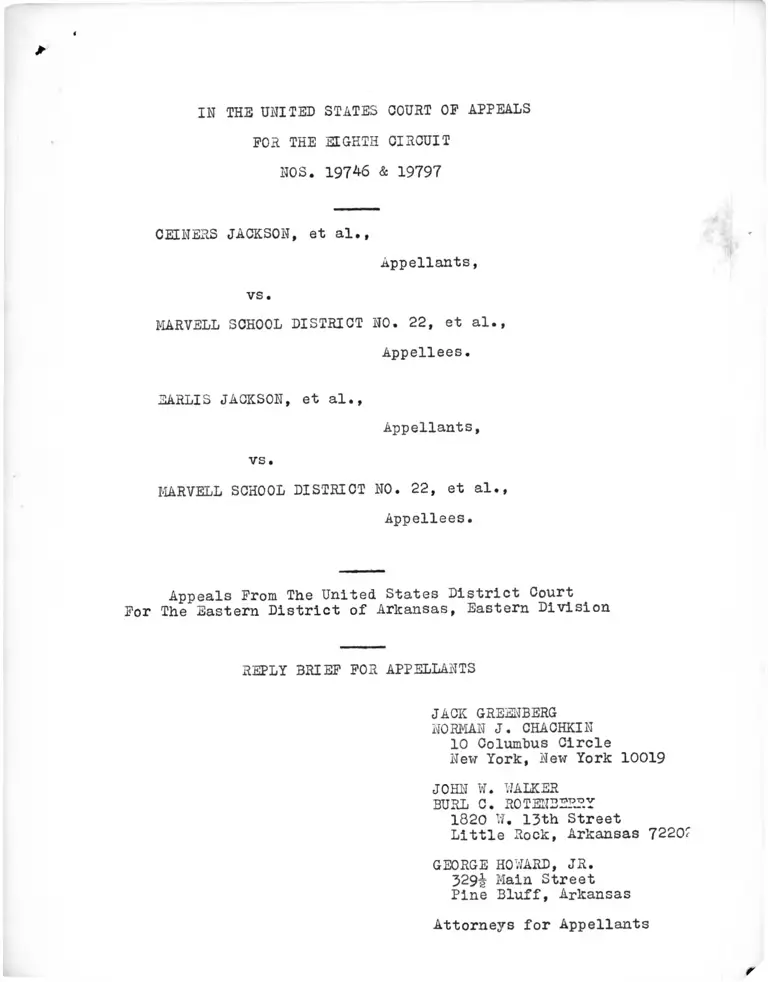

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19746 & 19797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

EARLIS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals Prom The United States District Court

Por The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

REPLY BRIEF POR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENDERRY

1820 W. 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 7220

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329^ Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

r

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19746 & 19797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al..

Appellees.

EARLIS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals Prom The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

VJhile Appellees* Brief only occasionally confronts

the issues in this case, it is replete with omissions and distor

tions of varying degrees. He file this Reply Brief to correct

some of those errors, and to emphasize that acceptance of the

argument profferred by the school district in this case would

be contrary to more than a decade of constitutional adjudication.

*•-

Misinterpretation of a case ordinarily merits no comment,

but we confess to being completely confounded by appellees' descrip

tion of Broussard v. Houston Independent School District* 395 F.2d

817, rehearing en banc denied. 403 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1968) as

having "sustained Houston's freedom-of-choice plan • . . (Ap

pellees' Brief, p. 13). In denying rehearing, Judge Connally

wrote (403 F.2d at 34-35)•

As noted in the original opinion, this action was

filed in the court below as a class action, in

equity, to restrain the expenditure of what^then

remained uncommitteed of the proceeds of a #59

million bond issue for school construction and

improvement. • . • In their petition for rehear

ing plaintiffs contend that though the building

program be complete, upon their request for

"further relief" this Court should remand the

action to the District Court to permit plaintiffs

to seek an order as to how the new buildings

may best be used to further and promote integra

tion. But this action is not the usual school

integration" case wherein the District Court is

charged with the duty of retaining jurisdiction

to shepherd the school district along its path

from segregation to integration. As heretofore

noted, such an action has been pending against

this defendant, in the Southern District of

Texas, for many years where all questions of

this nature appropriately may be raised.

Indeed, the action to which Judge Connally referred was pending in

his own court I On July 23, 1969, after an extensive trial, Judge

Connally ruled that Houston must submit a new plan not based upon

freedom of choice. Ross v. Bckels. Civ. Ho. 10444 (S.D. Texas,

. 1/

July 23, 1969)(oral comments of Connally, J.).

1/ Appellees skip far too lightly over Broussard and United Spates

v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin Countv. Georgia, Ho. 272ol v5th

Cir., July 9, 1 9 ^ 9 ) . In both school districts Involved, there was

extremely rigid residential segregation, which led the Court in

- 2-

Appellees persist in representing that we seek the impo

sition of a "racial balance" and the elimination of all-Negro

schools (See Appellees* Brief, pp. 12, 14-15, 19) • l;Je state again,

as we did in our Brief (n. 27, pp. 21-22; see also, n. 24, p. 15),

that appellants* objective is the eradication of the dual school

system based on race. In a district with only two schools, the

continued operation of one as an all-Negro institution, against a

background of past state-imposed segregation, inescapably signals

the failure to dismantle the dual system. In fact, appellants

expert witness testified that there was no educational support for

the operation of more than one school in Marvell, and that the only

2/reason for maintaining two schools was racial.”"

Baldwin County to conclude that drawing geographic zones would not

further the disestablishment of the dual system. There is no such

rigid residential segregation throughout the Marvell School Dist

rict, but zoning is inefficient and objectionable because of the

extremely small size of the district and the consequent lack of

educational opportunity which it entails. At any rate, neither

case gave any sort of blanket approval to freedom of choice.

We also urge the Court to compare Judge Bell’s dissenting opinion

in Jefferson II (cited in Appellees* Brief at p. 94 seealso n. 10_

at p. 19) with his opinion for the Court in Jefferson,III ~ United

States v. Jefferson County nd. of Educ.. No. 27444 (5th Cir., June

26, 1969)(slip opinion at pp. 5, 7):

It is clear that freedom of choice has not disestablished

the dual school systems in Bessemer or Jefferson County.

The district court was of the view that it would in time

but this probability will not meet the test of Creen if

there are other methods available which will disestablish

the dual system now. . . . 2/ There was testimony that

white students would not attend formerly Negro schools.

This is not a legal argument. Cf. Cooper v. Aaron. 358

U.S. 1 (1958).

2/ Although the district had every opportunity over the course of

*" two hearings in this matter to introduce such testimony as it

desired and to make whatever it desired, the Brief seeks to bolster

appellees’ arguments with newspaper and magazine references con

cerned with other cities and other districts. See n. 5 infra.

- 3 -

Jp

Appellees seek to excuse their failure to meet consti

tutional requirements by pointing out that there will be Negro and

white students on each of the three school sites they operated,

admitting that there will be no Negroes attending Tate High School.

A high school is a basic educational unit.

When racially identifiable under freedom of

choice it is not a unitized desegregated school

even if children of the opposite race attend

elementary school classes in the same building.

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd.. ___ F. Supp. _ Civ.

No. 15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969)(Slip Opinion, p. 5).

. . . (A) school composed of white classes and

black classes is not desegregated. Students must

be assigned to classes even as they must be assigned

to schools, in a racially nondiscriminatory fashion

and no classes may be racially identifiable.

Id. at 7.

Appellants are unable to accept any portion of the white

flight" argument advanced by appellees.

First, it cannot be said (Appellees’ Brief, p. 4) that

we "do not really challenge the factual proposition that any al-

*

ternative method of student assignment in this district will

result in the abandonment of the public schools by the white stu

dents."*^ We have never addressed ourselves directly to this

2/ Appellees seek support for their position from the Report of the

United States Civil Rights Commission (Appellees' Brief, p. 7)*

The cited discussion of "tipping points" related to districts in

which one or more schools developed an increasingly large black

enrollment, leading white parents to feel they were being treated

unfairly because the schools attended by their children "bore the

brunt of integration." The Commission’s conclusions are fhr less

susceptible of application to a unitary district in Marvell, Arkan

sas which would operate only one twelve-grade school and thereby

offer all of its enrolees an equal opportunity.

- 4 -

Jr

speculation because (a) it is nothing more than speculation- and

(b) it is irrelevant. If we were compelled to express our opinion

we would say that we are not at all so sure as the appellees that

establishing a unitary school system in Marvell, Arkansas will

cause a mass exodus of whites from the district;-^ we are certain

that a school board which was truly interested in the welfare of

its students could provide the enlightened leadership to prevent

this^ At any rate, it seems elementary to us that the public

school system can be preserved only by operating it in accordance

1/with the law of the land.

4/

4/ Of, United States v. Hinds County 3d. of Educ., No. 28030 (5th

Cir., July 3, 19^9)(slip opinion at p. 7 JV

5/ The record of other districts is also of questionable relevance.

There is no certainty that the experience of one district will

be repeated jjn any other. For example, when Alabama schools opened

this year with substantial increases in integration, whites stayed

away from classes in large numbers in only one district. See H.I.

Times, Sept. 7, 1969, §1 P- 32.

6/ Appellees suggest that it would not be prejudice which would

motivate white parents to withdraw their children from the

schools, but an unwillingness to send white children to schools

"where the dominant culture is so different from their own. Up-

pellees* Brief, p. 10). (This is probably not true — although

the majority of students might be Negro, the dominant culture in

any school today is a reflection of the dominant national culture

white). But the Board never considered this an obstacle so long as

Negro students were the ones who had to cross purported cultural

lines.

j/ Appellees refer to Congressional statements of "national policy

and to administrative announcements of a slowdown in school de

segregation (Appellees* Brief, pp. 14-18) and accuse us of ignor-|(

(ing) the foregoing executive and legislative pronouncements . . •

Ignore them we do not, but we are firm that they are not the pole

star of constitutional interpretation. This Court has long recog

nized, and specifically in the context of school desegregation

cases, that the judiciary, and not the executive or the legislative,

is the expositor of the Constitution. Kemp v. Beasley. 352 F. d

14, 18-19 (8th Cir. 1965).

- 5-

Second, we do not comprehend why the requirements of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States should

differ dependent upon whether a school district has a majority of

white or black students* Yet this is exactly the implication of

appellees’ repeated entreaties for special consideration because

8/this is a majority-Negro school district.”

The position of appellees is different only in degree, not

in kind, from the position of the Little Rock School Board in 1958.

Instead of white resistance to any integration, we now have:

These parents are willing to have their children

attend schools with (a few) Negroes, but they

are not willing to expose their children to the

consequences of being a minority in a school

where the dominant culture is so different from

their own.

(Appellees’ Brief, p. 10). Thus, this district is still unwilling

to offer educational opportunity to Negro students except on its

own terms -- percentage-wise or otherwise. And, as noted before,

the same arguments were made to the United States Supreme Court in

1968 and rejected by them. Rane.v v. Board of Uduc. of Could. 391

U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson. Tennessee.

391 U.S. 450 (1968); accord. Anthony v. liarshall County Bd. of

Educ.. No. 26432,(5th Cir., April 15, 1969); United States v.

Hinds County Bd. of Educ.. supra: United States v. Jefferson County;

8/ " . . . in spite of the fact that approximately 15% of the

students in this rural school district are Negro, . . .

(Appellees’ Brief, p. 2); " (i)t is an understatement to char

acterize the problems of desegregating a predominantly Negro

school district as delicate and difficult' (p. 5)•

Bd. of Educ.. supra: Walker v. County School Bd. of Brunswick

County. No. 13,283 (4th Oir.t July 11, 1969).

Judicial integrity and preservation of the Constitution

demand that the same arguments be rejected in this case.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

1820 W. 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants

- 7 -

' % ; 7 7 « *

72

,4-Ci'V'-<- ,r

^ 1 tfvlA^ ’jr r 'v

/

* **~P • • • ;

■V̂ .,

^ . .

y</vv fw - t y ) — /2>ĉ 7 71' /77)̂ ̂ , y, ̂ _y

. . V ' , , « % - ' . - - - U l*.*,

t ? ' < f c ? , K • « • « * * * . .

/ V

I ^ l p i < t - « * # • ..' U . j?

: .£ — £ < M o w -f M**

Mi ^ '{ j j bo1- 7 3 o / " ~ ~

C /^ CT-*t^ u . -■* ? o f , r a r Q , / L- y i C - ^ o i

^ H sU a}

jt

V a -c)

,7 ^ 7 j ' ^ " ' -[ t v

d y c j i c c' ^

V . y > - 5 j V y v - y t

VA.̂flb