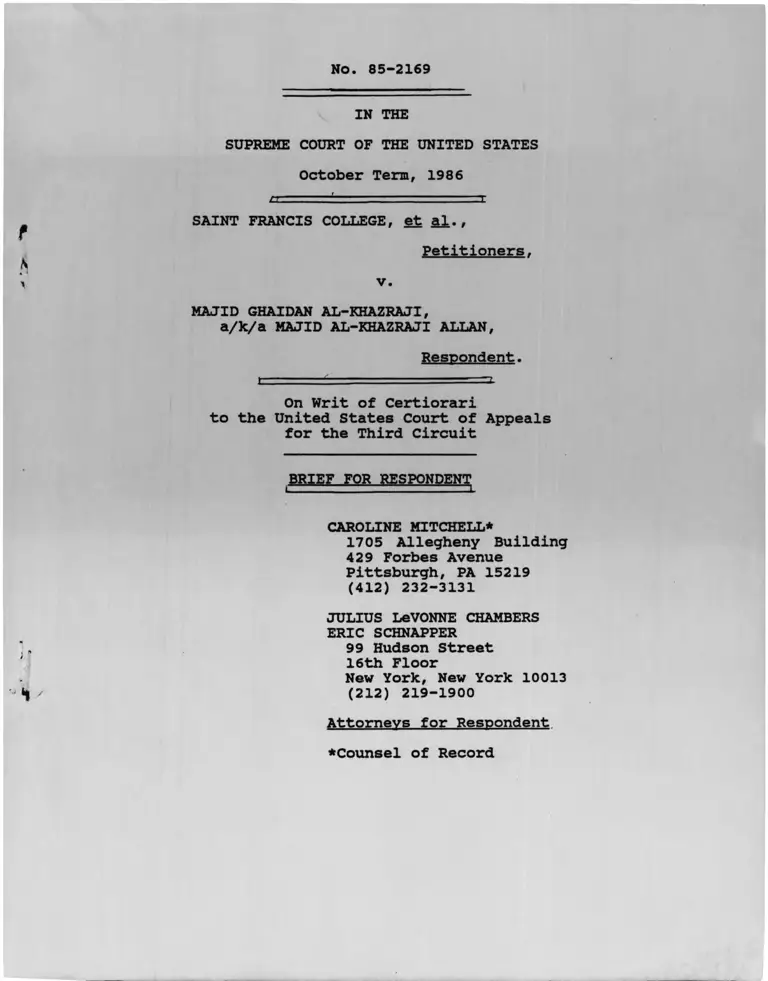

Saint Francis College v Al-Khazraji Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1986

196 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Saint Francis College v Al-Khazraji Brief for Respondent, 1986. 120e8473-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/687e0c0a-98f5-4fa4-9d5d-cf0693eaadef/saint-francis-college-v-al-khazraji-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 85-2169

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1986

SAINT FRANCIS COLLEGE, et al.,

Petitioners.

v.

MAJID GHAIDAN AL-KHAZRAJI,

a/k/a MAJID AL-KHAZRAJI ALLAN,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

BRIEF FOR SEgPQNDENT

CAROLINE MITCHELL*

1705 Allegheny Building

429 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

(412) 232-3131

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Respondent

♦Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does 42 U.S.C. § 1981 prohibit

discrimination on the basis of ancestry?

2. Did the court of appeals err in

refusing to apply retroactively that

court's decision in Goodman v. Lukens

777 F.2d 113 (3d Cir. 1985)?Steel Co

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ......... i

Table of Authorities ........ v

Statement of the Case ....... 1

Summary of Argument ......... 7

ARGUMENT .................... 13

I. The History of Federal

Treatment of Individuals

of Non-European Ancestry 13

II. Section 1981 Prohibits

1 Discrimination on the

Basis of Ancestry..... 3 6

A. Introduction........ 3 6

B. The 1866 Civil Rights

Act and the

Fourteenth Amendment . 46

C. The Etymology of the

word "Race" ......... 50

D. The Legislative

History of Section

1981 ................ 73 f

ii

Page

E. The Difficulties In

herent in Petitioners1

Proposed Construction

of Section 1981 ..... 88

(1) The Definition

of "Caucasian" .... 88

(2) Discrimination on

the Basis of Color 99

III. The Court of Appeals

Properly Refused to Give

Retroactive Effect to its

Decision in Goodman v.

Lukens Steel. 777 F.2d 13

(3d Cir. 1985) ......... 103

Conclusion .................. 129

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Racial Classi

fications Utilized by

the Bureau of Immigration

and Naturalization ..... la

Appendix B: Racial Tables

in the Annual Reports

of the Commissioner

General of Immigration .. 4a

Appendix C: "Racial Classi

fication," Report of the

Commissioner General of

Immigration: 1904, pp.

161-62 ................. 9a

iii

Page

Appendix D: Dictionaries

Cited .................. 12a

Appendix E: Definitions of

"Race" ................. 18a

Appendix F: Definitions of

"Kinsman," "Kinswoman,"

"Kin" and "Kindred" .... 28a

Appendix G: Definitions of

"Family" ............... 32a

Appendix H: Definitions of

"Lineage" .............. 3 6a

Appendix I: Definitions of

"Progeny" .............. 39a

Appendix J: Definitions of

"House" ................ 41a

Appenidx K: Definitions of

"Gypsy" ................ 44a

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Abdulrahim v. Gene B. Glick Co.,

612 F. Supp. 256 (C.D. Ind.

1985) 103

Alizadeh v. Safeway Stores, Inc.

41 FEP Cas. 1556 (5th Cir.

1986) 103

Anandam v. Fort Wayne Community

Schools, 19 F.E.P. Cas. 773

(N.D. Ind. 1978) 102

Annoya v. Hilton Hotels Corp.,

733 F.2d 48 (7th Cir. 1984) . 103

Anton v. Lehpamer, 787 F.2d 1141

(7th Cir. 1986) ............ Ill

Banker v. Time Chemical, Inc.,

579 F. Supp. 1183 (N.D. 111.

1983) 103

Bartholomew v. Fischl, 782 F.2d

782 F.2d 1148 (3d Cir. 1986).108,110

Baruah v. Young, 536 536 F.Supp.

356 (D.Md. 1982) ........... 103

Batson v. Kentucky, 90 L.Ed.2d

90 L. Ed. 2d 69 (1986) ..... 69

v

Pace

Beacon Theatres v. Westover,

359 U.S. 500 (1959) ........

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404

43

U.S. 97 (1971) ...... 107,109,112-13

Davis v. United States Steel

Supply, 581 F.2d 333 (3d.

Cir. 1978) ............. 117,118,119

Delaware State College v. Ricks,

449 U.S. 250 (1980) ....5,39,121,127

DeVargas v. New Mexico, 97 N.M.

563, 642 P. 2d 166 (1982) ... 109

Dow v. United States, 226 F.

145 (4th Cir. 1910) ........ 28

Electrical Workers v. Robbins &

Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229

(1976) ..................... 126

Ex parte Dow, 211 F. 486

(E.D.S.C. (914) ............ 24

Fanner v. Cook, 782 F.2d 780

(8th Cir. 1986) ............ 108

Fitzgerald v. Larson, 741 F.2d

32 (3d Cir. 1984) .......... 119

Flores v. McCoy, 184 Cal. App.

2d 502, 9 Cal. Rptr. 349

(1960) ..................... 34

Fong Yue Ting v. United States,

149 U.S. 698 (1893) ........ 69,70

vi

Page

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448

U.S. 448 (1980) ............ 47

Garcia v. Wilson, 731 F.2d 640

(10th Cir. 1984)............ 114

Gibson v. United States, 781

F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1986) ... Ill

Gonzalez v. Stanford Applied

Engineering, 597 F.2d

1298 (9th Cir. 1979) 103

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Corp.

777 F.2d 113 (3d Cir.

1985) 1,12,106,116,122-25

Hernandez v. State, 251 S.W.

2d 531 (Tex. Crim. App.

1952) 36

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S.

475 (1954) 35,36,47

Herrera v. People, 87 Colo.

360, 287 P.2d 643 (1930) 34

Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U.S. 81 (1943)....... 8,47,48,69

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24

(1948) 9,49

Ibrahim v. New York Dept, of

Health, 581 F.228 (E.D.N.Y.

1984) 103

vii

In re Ahmed Hassan, 48 F.Supp.

843 (E.D. Mich. 1942) 8,32

In re Balsara, 171 F.294

(S.S.N.Y. 1909) 23,26

In re Dow, 213 F.335 (E.D.S.C.

1914) 26-27

In re Ellis, 179 F. 1002

(D. Ore. 1910) 24

In re Halladjian, 174 F. 834

(D. Mass. 1909) 8,23-25

In re Mozumdar, 207 F.2d 115

(E.D. Wash. 1913) 24

In re Mudarri, 176 F. 465

(D. Mass. 1910) 23

In re Najour, 174 F. 735

(N.D. Ga. 1909) 23

In re Shahid, 205 F. 812

(E.D.S.C. 1913) 24,28

In re Singh, 246 F. 496

(E.D. Pa. 1917) 24,28

In re Singh, 257 F.2d 209

(S.D.Cal. 1919) 24

Jackson v. City of Bloomfield,

731 F.2d 652 (10th Cir.

1984) 111,112

Page

viii

Page

Jawa v. Fayetteville State

University, 426 F.Supp. 218

* (E.D.N.C. 1976) 102

Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975) ... 42

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968) 39

Jones v. Bechtel, 788 F.2d 571

(9th Cir. 1986) Ill

Jones v. Preuit & Mauldin,

763 F. 2d 1250 (11th Cir.

1985) 108

Jones v. Shankland, 800 F.2d

77 (6th Cir. 1986) 108

Khawaja v. Wyatt, 494 F.Supp.

302 (W.D.N.Y, 1980) 103

Korematsu v. United States,

323 U.S. 214 (1944) 69

Liotta v. National Forge Co.,

629 F.2d 903 (3d Cir. 1980) . 118

Maillard v. Lawrence, 54 U.S.

251 (1853) 50

Marks v. Parra, 785 F.2d

1419 (9th Cir. 1986) 109

Mayers v. Ridley, 465 F.2d 630

(D.C.Cir 1972) (en banc).... 44

ix

Page

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transportation Co., 427

U.S. 273 (1976) ......... .. 37,99-101

Memphis v. Greene, 451 U.S.

100 (1981) .............. .

Meyers v. Pennypack Woods Home

Ownership Ass’n, 559 F.2d

894 (3d Cir. 1977) ....... . ..117,118

Morrison v. California, 291

U.S. 82 (1934) ...........

Mozumdar v. United States,

229 F.240 (9th Cir. 1924) . 31

Mulligan v. Hazard, 54 U.S.L.W.

3808 (1986) ..............

Naraine v. Western Electric

Co., 507 F.2d 590 (8th

Cir. 1974)................

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S.

697 (1931) ...............

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S.

633 (1948) ...............

Plessy v.Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896) .....................

Procunier v. Navarette, 434

U.S. 555 (1978) ..........

Quock Ting v. United States,

140 U.S. 417 (1891) ......

x

Page

Rajender v. University of

Minnesota, 24 F.E.P. Cas.

1051 (D. Minn. 1979) 102

Regents of University of

California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978) 70

Ricks v. Delaware State

College, 605 F.2d 710

(3d Cir. 1979) 5

Ridgway v. Wapello County,

Iowa, 795 F.2d 646 (8th

Cir. 1986) 111,125

Riggin v. Dockweiler, 104 P.2d

367, 15 Cal. 2d 651 (1940) .. 34

Rivera v. Green, 775 F.2d

1381 (9th Cr. 1985) 109

Saad v. Burns International

Security Services, 456

F.Supp. 33 (D.D.C. 1978) .... 103

Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S.

19 (1857) 30

Sethy v. Alameda County Water

Dist., 545 F.2d 1157

(9th Cir. 1988) 102

Shaare Tefila Congregation

v. Cobb, No. 85-2156 ....... 44

Shah v. Halliburton, 627

F.2d 1055 (10th Cir. 1980) .. 102

xi

Page

Shah v. Mt. Zion Hospital, 642

F.2d 268 (9th Cir. 1981).... 102

Skehan v. Board of Trustees of

Bloomsburg State College,

590 F.2d 470 (3d Cir.

1978) 118

Smith v. Pittsburgh, 764 F.2d

188 (3d Cir. 1985) 111,119

State v. Martinez, 673 P.2d

441, 105 Idaho 841 (1983) ... 34

State v. Quigg, 155 Mont.

119, 467 P.2d 692 (1970) 34

Sud v. Import Motors Limited,

Inc., 379 F.Supp. 1064

(W.D. Mich. 1974) 103

Takahashi v. Fish and Game

Commission, 334, U.S.

410 (1948) 38

Tayyari v. New Mexico State

University, 495 F.Supp.

1365 (D.N.M 1980) 103

United States v. Ali, 7 F.2d

728 (E.D. Mich. 1925) 31,32

United States v. Cartozian,

6 F.2d 919 (D. Ore. 1925) ... 31

United States v. Gokhale, 26

F.2d 360 (2d Cir. 1928) .... 31

xii

United States v. Khan, 1 F.2d

1006 (W.D.Pa. 1924) ........ 31

United States v. Pandit, 15

F.2d 285 (9th Cir. 1926) ___ 31

United States v. Thind, 261

U.S. 204 (1923) ..... 8,14,15,28-33,

94,96,101,102

United States v. Wong Kim Ark,

169 U.S. 649 (1898) 39,70

Wilson v. Garcia, 85 L.Ed. 2d

254 (1985) 7,11,104-112,114-116,

119,122,124,125

Wycoff v. Menke, 773 F.2d 983

(8th Cir. 1985) 111,125

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356 (1886) 39

Zuniga v. AMFAC Foods, Inc.

580 F.2d 380 (10th Cir.

1978) 109

Statutes and Constitutional

Provisions:

42 U.S.C. §1981 ................. Passim

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............. 104-05,114

Revised Statutes, §2169 ......... 22,23

Page

xiii

Civil Rights Act of 1866 Passim

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VII ......... .5,41-43,120,128

1 Stat. 103 ............

14 Stat. 27 ............

16 Stat. 256 ...........

39 Stat. 876 ...........

39 Stat. 877............

43 Stat. 159 ...........

66 Stat. 239 ...........

Seventh Amendment ......

Fourteenth Amendment ....

Legislative Materials:

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1866) ... ..10,37,49,74-87

Cong. Globe, 34th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1856) ...

53 Cong. Rec. (1916) ....

Sen. Doc. No. 662, 61st Cong.,

3d Sess. (1911) ............ 20

xiv

Sen. Doc. No. 747, 61st Cong.,

1st Sess. (1911) .......

Page

19,71

H.R. Rep. No. 95, 64th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1916) ........... 21

Dictionaries and

Encyclopedias:

American College Dictionary ..... 65

W. Bolles, An Explanatory and

Phonographic Pronouncing

Dictionary of the English

Language (1847) 55

Century Dictionary and

Cyclopedia (1911) ....... 61-63

Chambers1 Twentieth Century

Definition of the English

Language (1908) 64

H. Clark, A New and

Comprehensive Dictionary

of the English Language

(1855) 55

Encyclopedia Americana (1854) ....9,55-57

Encyclopedia Britannica (1878) ... 59-60

Encyclopedia Britannica (1910) ... 94

Encyclopedia Britannica (1963) ... 93,95-

96,98

Encyclopedia Brittanica (1986) ... 94,98

xv

Page

Funk and Wagnalls New College

Standard Dictionary (1947) .. 65

Samuel Johnson, Dictionary of

the English Language (1768) . 51

New American Cyclopaedia

(1858-63) 57-59,90-91

Odhams Dictionary of the

English Language (1946) 65

Oxford American Dictionary

(1980) 66

Oxford English Dictionary

(1933) 53

E. Partridge, Origins: A

Short Etymological

Dictionary of Modern

English (1966) 65

E.D. Price, the British Empire

Dictionary of the English

Language (c. 1899) ...... 64

Random House Dictionary of

the English Language: the

Unabridged Edition (1966) ... 66

A. Reid, A Dictionary of the

English Language (1846) 55

W. Skeat, An Etymological

Dictionary of the English

Language (1910) 64

xv i

Page

D. Smalley, The American

Phoenetic Dictionary of the

English Language (1855) 54,55

Thorndike Century Senior

Dictionary (1941) 65,66

Thorndike - Barnhart

Comprehensive Desk

Dictionary (1955) 65

N. Webster, An American

Dictionary of the English

Language (1830) 52,53

Webster's Collegiate Dictionary

(1916)........................ 63-64

Webster's Ninth New Collegiate

Dictionary (1985) 65,66

Webster's Second New

International Dictionary

(1956) 67,68

Webster's Seventh New

International Dictionary

(1963) 66

Webster's Third New

International Dictionary

(1981) 67-68

[Webster] William Wheeler,

Dictionary of the English

Language (1876) 54,55

xvii

Page

E. Weekley, An Etymological

Dictionary of Modern

English (1921) ............. 64

Winston Simplified

Dictionary (1919) .......... 64

J. Worcester, A Universal

and Critical Dictionary of

the English Language (1846) . 54,55

H. Wyld, Universal Dictionary

of the English Language

(1932) ..................... 64

Books:

M. Banton and J. Harwood, The

Race Concept (1975) 71

R. A. Billington, The

Protestant Crusade 1800 -

1860: A Study of the Origins

of American Nativism (1963) . 81

I.F. Blumenbach, Elements of

Natural History (1825) 93

F.L. Burdette, The Republican

Party: A Short History

(2d ed. 1972) 82 S.

S. C. Busey, Immigration: Its

Evils and Consequences

(1856) 10,80

xviii

Page

H.J. Desmond, The Know Nothing

Party (1904) 81

J.B. James, The Framing of the

Fourteenth Amendment (1908) . 82

A. Montague, The Concept of

Race (1964) 71

A. Montague, Man's Most

Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy

of Race (1942) 72

S.G. Morton, Types of Mankind

(1854) 90

A. Tennyson, Poems (1853) 52

M.E. Thomas, Nativism in the

Old Northwest, 1850-60

(1936) 81,82

Miscellaneous

Materials:

Annual Report of the

Commissioner - General of

Immigration: 1899 .......... 16,17

Annual Report of the

Commissioner - General of

Immigration: 1906 .......... 18

Bureau of the Census,

Fifteenth Annual Census of

the United States, 1930,

v. iii (1932) .......... 34

xix

Page

Immigration and Naturalization

Service, Monthly Bulletin,

v.l, no.4, (October, 1943) .. 33

Brief in Opposition, No. 406,

October Term, 1953 .... 36

Brief for Petitioner, No. 406,

October Term, 1953 ......... 35

Brief for United States,

Wadia v. United States. 101

F. 2d 7 (2d Cir. 1939) ...... 31

Note, Aliens' Right to Work:

State and Federal

Discrimination, 45 Fordham

L. Rev. 835 (1977) ......... 15

O'Connor, Constitutional

Protection of the Alien's

Right to Work, 18 N.Y.U.L.Q.

Rev. 483 (1941) ............ 15

X X

No. 85-2169

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1986

SAINT FRANCIS COLLEGE, et al.,

Petitioners.

v.

MAJID GHAIDAN AL-KHAZRAJI,

a/k/a MAJID AL-KHAZRAJI ALLAN,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondent is a naturalized American

citizen born in Iraq of Arab ancestry.

Respondent came to the United States more

than two decades ago to complete his

education; he received his bachelor's

2

degree from Cornell University and his

Ph. D. from the University of Wisconsin.

Respondent was hired in 1971 as a member

of the faculty of St. Francis College,

and taught in the Sociology Department

until 1979. In 1977 the Sociology

Department unanimously recommended that

respondent be awarded tenure; according

to the complaint, in every other case in

the history of the school such a

unanimous departmental recommendation had

been accepted by the college. (J. App.

63). However, the complaint also alleged

that as of 1978 St. Francis had never

awarded tenure to any faculty member of

non-European ancestry. (J. App. 63).

On February 10, 1978 the college's

tenure committee, ignoring the views of

respondent's own colleagues, urged that

St. Francis College deny respondent

3

tenure; later that month the college's

board of trustees voted to deny

respondent tenure. Respondent requested

that this decision be reconsidered, and

in September 1978 the faculty senate

voted to authorize the faculty affairs

committee to review the recommendation of

the tenure committee. The faculty

affairs committee in January, 1979,

recommended that the faculty senate

request reconsideration of the tenure

decision, and the senate did so. On

February 6, 1979, however, the tenure

committee met and decided not to

reconsider respondent's application for

tenure. (Pet. App. 2a-3a).

During 1978 and early 1979

respondent contacted the Pennsylvania

Human Relations Commission ("PHRC") and

attempted to file a complaint of

4

discrimination. Although respondent

provided the Commission with written

material documenting his allegation, PHRC

expressly refused to formally "docket11

any complaint. Prior to 198 0 it was

PHRC1s express policy to refuse to

process a complaint based on a denial of

tenure until the complainant had ceased

working for the school involved. (Pet.

App. 3a-5a). On May 26, 1979,

respondent's employment by St. Francis

college ended; 24 days later respondent

duly filed a charge with PHRC. On May

19, 1980,. however, PHRC dismissed

respondent's 1979 complaint as untimely,

holding that he should have filed his

charge in 1978, when PHRC itself had

forbidden respondent to do so. (Pet.

App. 3a-4a). PHRC's decision was

squarely contrary to then prevailing

5

third circuit law, which held that the

Title VII limitations period began to

run, not when an employee was denied

tenure, but only when the employee ceased

working for his or her employer. Ricks

v. Delaware State College. 605 F.2d 7710

(3d Cir. 1979), rev'd. 449 U.S. 250

(December 15, 1980).

Following dismissal of his charge by

PHRC, respondent obtained an EEOC right

to sue letter, and commenced this action

on October 30, 1980. Six weeks later

this Court decided Delaware State College

v. Ricks, holding that the discriminatory

act in a case such as this is the final

decision to deny tenure. 449 U.S. at

256-59. The district court, applying in

Ricks retrospectively, dismissed the

Title VII claim as untimely. (Pet. App..

51a-55a). The court of appeals affirmed,

6

agreeing that Ricks should be applied

retroactively. (Pet. App. 9a-12a).

Respondent also asserted a claim

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. The original pro

se complaint, and subsequent amended

complaints, asserted inter alia that

respondent had been discriminated against

because of his ancestry, Arabian, and his

national origin, Iraqi. One of the

complaints alleged that respondent had

been denied tenure because of his " race

(Arabian)." (J. App. 16, 22, 51). The

district court dismissed the complaint,

holding that section 1981 does not forbid

discrimination on the basis of ancestry.

(Pet. App. 37a-39a) . The court of

appeals reversed, holding that section

1981 forbids discrimination against any

•'group that is ethnically and

physiognomically distinctive." (Pet.

7

App. 24a) . The court of appeals also

declined to apply retroactively Wilson v.

Garcia. 85 L.Ed.2d 254 (1985) reasoning

that respondent had been entitled prior

to Wilson to rely on "absolutely clear"

circuit precedent establishing a longer

period of limitations than is appropriate

under Wilson. (Pet. App. 15a-16a).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The interpretation of

section 1981 must take into account the

ease with which racial concepts can be

manipulated to reflect popular

prejudices. For most of the first half

of this century the United States

government insisted that Arabs were not

"white". The Justice Department urged

that "the average man in the street would

find no difficulty in assigning to the

yellow race a ... Syrian with as much

8

ease as he would bestow the designation

on a Chinaman or a Korean." In re

Hallad-iian. 174 F. 834, 838 (1909). This

Court upheld that approach, insisting

that the "whites" eligible for

naturalization under federal law were

generally limited to Europeans. United

States v. Thind. 261 U.S. 204 (1923).

Lower court decisions applying Thind

refused to permit natural iza-t ion of Arabs

because in part of their "dark skin." In

re Ahmed Hassan. 48 F. Supp. 843, 845

(E.D.Mich. 1942).

II. Section 1981, like the

Fourteenth Amendment, prohibits

discrimination on the basis of ancestry.

Discrimination on the basis of ancestry

is racial discrimination within the

meaning of the Equal Protection Clause.

Hirabavashi v. United States. 320 U.S.

9

81, 100 (1943). Section 1981

presumptively prohibits the same types of

discrimination forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment. Hurd v . Hodge. 3 34

U.S. 24 (1948).

A review of 50 English dictionaries

printed between 1750 and 1985

demonstrates that in 1866 "race" meant

"ancestry" or "ethnic group." This usage

is clearly reflected in mid-nineteenth

century publications. The 1854

Encyclopedia Americana. for example,

characterized Arabs, Bedouins, Berbers,

Hebrews, Tartars, Finns, and gypsies all

as distinct races. (See pp. 55-57,

infra). Members of the thirty-ninth

Congress, which adopted the 1866 Civil

Rights Act, referred variously to "the

Scandinavian races," "the Chinese race,"

"the Latin races," "the Spanish race" and

10

the "Anglo-Saxon race." (See pp. 73-76,

infra).

The 1866 Civil Rights Act was

adopted in part to prohibit the sort of

discrimination on the basis of ancestry

which had been expressly advocated in the

1850's by the Know Nothing Party. One

prominent Know Nothing tract denounced

the Germans and Irish as "degenerated

races" unfit to live with native

Americans. S. Busey, Immigration: Its

Evils and Consequences, p. 23, 39, 42

(1855) . In response to such proposals,

Senator Shellabarger emphasized that the

1866 Act would forbid discrimination

against "the German race." Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess., 1294.

Petitioners argument that

"Caucasians" are not "protected persons"

insurmountable practicalpresents

11

problems. (Pet. Br. 16, 28) . By 1866

ethnologists propounded a dozen different

theories regarding the appropriate

definition of Caucasian; under most

classification systems neither Jews nor

Arabs were then classified as Caucasian.

The proposed definition of Caucasian has

varied widely over the last 120 years; at

the turn of the century, for example,

Finns, Turks and Lapps were all regarded

as orientals. It is inconceivable that

the scope of the protections established

by section 1981 shift with such changes

in ethnological thinking.

III. Wilson v. Garcia. 85 L.Ed.2d

254 (1985) , held that the appropriate

limitations period for a section 1983

action should be that established by

state law for an action for damages for

personal injuries. In Pennsylvania that

12

limitation period is two years. This

Court has granted certiorari to decide

whether the limitations rule in a section

1981 case should be based on the

limitation period applicable to a

personal injury action, or to an action

in contract. Goodman v. Lukens Steel

Co.. No. 85-1626.

However Goodman may be resolved, it

should not be applied retroactively to

the instant case. As the court of

appeals observed, when the instant case

arose it was "absolutely clear" under

third circuit decisions that a section

1981 action was subject to a six year

period of limitations in Pennsylvania.

(Pet. App. 15a-16a). A circuit court's

reading of its own past decisions is

entitled to considerable deference. The

minor changes that occurred in the

13

Pennsylvania statutes in 1978 did not

vitiate the precedental significance of

the third circuit's decisions.

ARGUMENT

I. THE HISTORY OF FEDERAL TREATMENT

OF INDIVIDUALS OF NON-EUROPEAN

ANCESTRY

The interpretation of section 1981,

like that of the Equal Protection Clause,

must take into account the ease with

which racial concepts have in the past

been manipulated to fit the prejudices of

the day, and the danger that such changes

could occur again. Over the course of

modern history the problems of racial

discrimination have been inextricably

interrelated with shifting popular

theories as to which groups constitute

distinct races. Today few Americans

would, out of either insensitivity or ill

will, describe Arabs or Jews as a "race,"

14

or suggest that either group is somehow

distinct from the "white race." But it

was not always so.

Sixty-four years ago this Court

ruled unanimously that a Caucasian native

of the continent of Asia was, as a matter

of federal law, not "white," and was thus

absolutely ineligible for naturalization

as a United States citizen, solely

because his ancestry was Asian rather

than European. United States v. Thind.

261 U.S. 204 (1923) . Although the

individual declared non'-white in that

case was an Asian Indian, both the

Department of Justice and the lower

courts interpreted Thind to mean that any

Arab born in Asia was also as a matter of

federal law non-white. An Arab or Indian

excluded from naturalization by Thind was

subject as a consequence to a host of

15

discriminatory state statutes, including

laws barring such individuals from many

public and private jobs, and from

practicing a number of professions.3- In

the instant case petitioners urge this

Court to rule that employment

discrimination against Asian Indians,

Arabs and others is permitted by section

1981, and to ground that result on a

holding that Arabs, Indians, and other

non-European "Caucasians'' are now, as a

matter of federal law, to be declared to

be officially "white."

The decision in Thind. and the

Justice Department racial theories which

Thind endorsed and perpetuated, had their

roots in the virulent hostility that

1 See Note, Aliens' Right to Work:

State and Federal Discrimination, 45

Fordham L.Rev. 835 (1977); O'Conner,

Constitutional Protection of the Alien's

Right to Work, 18 N. Y.U.L.O. Rev. 483 (1941).

16

emerged at the turn of the century

towards the waves of immigrants then

arriving from southern Asia, northern

Africa, and central and southern Europe.

In 1899 the reports of the Bureau of

Immigration began to list new immigrants

by "race” as well as nationality; the

Bureau explained that

[A]n Englishman does not lose his

race characteristics by coming from

South Africa, a German his by coming

from France, or a Hebrew his, though

he come from any country on the

globe.2

The 1899 report classified immigrants

into 49 races, including "Syrian" and

"Hebrew." Hispanics were divided into

six races; "Spanish," "Cuban," "Mexican,"

"South American," "Central American" and

"West Indian," and Italians were divided

2 Annual_____ Report_____ of_____ the

Commissioner-General of Immigration:

1899, 5.

17

into two races "Italian (northern)" and

"Italian (southern)."3 This official

list of races remained in use by federal

immigration authorities for over 35

years, with the intermittent addition of

additional races, including "Arabian" and

"Spanish-American." (See Appendices A

and B) . In 1904 the Bureau of

Immigration promulgated an official

ethnological theory, dividing these 49

races into six "well-recognized

divisions;" the Syrian race was placed in

the Iberic division together with the

Spanish and South Italian races, the

Hebrew race was part of the Slavic

division together with most eastern

European races, and the North Italian

race was classified in the Celtic

division, which included the Irish and

3 Id. 6-7.

18

French races (See Appendix C) . In 1906

the Bureau called attention to a

"startling” shift in the sources of

immigration away from northern European

nations "inhabited by races nearly akin

to our own;" southern and eastern Europe

and Asia Minor, the Bureau warned, were

the "racial sources [from which] the

blood is drawn that is being constantly

injected into the veins of our own

race."4

In 1911 an Immigration Commission

established by Congress issued an

exhaustive report on the character of the

new "races" of immigrants from central

and southern Europe and asiatic Turkey.

It concluded

The new immigration as a class is

4 Annual_____ Report_____ of_____ the

Commissioner-General of Immigration:

1906, 5.

19

far less intelligent than the old

... Racially they are for the most

part essentially unlike the British,

German, and other peoples who came

here during the period prior to

1880, and generally speaking they

are actuated in coming by different

ideals...5

The Commission recommend the imposition

of a "limitation of the number of each

race arriving each year to a certain

percentage of the average of that race

arriving during a given period of years."

The Commission also urged that the

immigration of undesirable races be

curbed by adoption of a literacy

requirement, explaining there were six

races of immigrants half or more of whom

could be turned away by means of this

test, including the "Syrian," "Mexican,"

and "South Italian" races.6 The

5 Sen. Doc. No. 747, 61st Cong.,

1st Sess., 14 (1911).

6 Id. 47, 99.

20

Commission published a separate volume

describing in detail the racial

characteristics of over 600 different

races, explaining, for example, that

members of the North Italian race were

"cool, deliberate, patient, practicable,

and ... capable of great progress," while

the South Italian race, "closely related

to be Iberians of Spain and the Berbers

of northern Africa," and possibly with

"traces of African blood," was

"excitable, . . . impulsive, highly

imaginative, impracticable, having little

adaptability to highly organized

society." 7

The Commission's avowedly racial

proposals soon became law. In 1917 a

literacy test was enacted for the avowed

7 Sen. Doc. No. 662, 61st Cong. 3d

Sess., 82 (1911).

21

purpose of excluding undesirable

"races".8

8 The 1916 House Report, expressly

relying on the 1911 Commission Report,

explained that the literacy test was

designed in particular to stem

immigration by southern and eastern

Europeans, particularly Italians, who it

described as prone to "crimes of personal

violence." H.R. No. 95, 64th Cong., 1st

Sess., 4-5 (1916). Speaking in favor of

the literacy requirement, Representative

McKenzie explained that the newer

immigrants were unlike the earlier

"Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Germanic .. .

races":

"The congenial assimilation of races

so different in temperament and

traditions as those of southern

Europe and oriental countries with

the races of northern and western

• Europe is a practical

impossibility."

53 Cong. Rec. 4776-77 (1916). See also

id. at 4783 (remarks of Rep. Hood)

(citing Immigration Commission's racial

views) 4789 (remarks of Rep. Vinson)

(emphasizing "the difference between the

north and south Italians"), 4796 (remarks

of Rep. Wilson) (literacy test needed to

end immigration of illiterate "European

... races"), 4806 (remarks of Rep. Focht)

(favors admission of "the Jew, the

Armenian, and the Dago, and any other

(continued...)

22

39 Stat. 877. The 1917 act also created

what came to be called the "Asiatic

Precluded Zone," forbidding any

immigration whatever from the Moslem

regions of Asian Russia and part of the

Arabian peninsula, as well as from Indo

china and the Indian subcontinent. 39

Stat. 876. Immigration quotas largely

excluding non-Europeans were enacted in

1924. 43 Stat. 159.

The same racial views that shaped

federal policy towards future immigration

also affected federal treatment of

immigrants who had already reached our

shores. The vehicle for the latter

policy was section 2169 of the Revised 8

8(...continued)

race" only if literate), 4810-11

(literacy of immigrant "races," including

Syrian, etc.), 4881-3 (remarks of Rep.

Chandler) criticizing racial purpose of

literacy test).

23

Statutes, which provided that the

procedures for naturalization were open

only to "aliens being free white persons

and to aliens of African nativity and to

persons of African descent."9 Begin

ning in 1909, the Department of Justice

initiated an aggressive campaign to

utilize section 2169 to prevent the

naturalization of immigrants from

southern and western Asia. Between 1909

and 1923 a majority of the reported

section 2169 cases involving non-Oriental

Asians were directed at preventing the

naturalization of Syrian Arabs.10

9 See 1 Stat. 103, 16 Stat. 256.

10 In re Balsara. 171 F. 294

(S.D.N.Y. 1909) (Indian; dicta forbidding

naturalization of Arabs); In re Naiour.

174 F. 735 (N.D.Ga. 1909) (Syrian Arab) ;

In re Hallad~iian. 174 F. 834, 844 (D.

Mass. 1909) (Armenian; noting the

existence of three unreported cases

involving Arabs); In re Mudarri. 176 F.

(continued...)

24

The Justice Department's

extraordinary racial theories were quoted

at length in In re Halladiian. 174 F. 834

(D.Mass. 1909). According to the

government, the non-Negro peoples were

divided into two races, the white or

European race, and the "Asiatic or yellow

race." 174 F. at 837-38. "European, or

its analogous term white," the Department

argued, referred

not merely to the local habitat of

the person to who it applied, but

... [to] the prevailing ideals,

standards, and aspirations of the

people of Europe. 174 F. at 837.

The "Asiatic or yellow race," included 10

10(...continued)

465 (D.Mass. 1910) (Syrian Arab); In re

Ellis. 179 F. 1002 (D.Ore. 1910) (Syrian

Arab); In re Shahid. 205 F. 812 (E.D.S.C.

1913) (Syrian Arab); In re Mozumdar. 207

F. 115 (E.D. Wash. 1913) (Indian); Ex

parte Dow. 211 F. 486 (E.D.S.C. 1914),

213 F. 355 (E.D.S.C. 1914) (Syrian Arab);

In re Singh. 246 F. 496 (E.D.Pa. 1917)

(Indian); In re Singh. 257 F.2d 209

(S.D.Cal. 1919) (Indian).

25

"substantially all the aboriginal peoples

of Asia." 174 F. at 838. The racial

identity of particular individuals,

according to the government, was self-

evident to ordinary citizens:

[T]he average man in the street ...

would find no difficulty in

assigning to the yellow race a Turk

or Syrian with as much ease as he

would bestow the designation on a

Chinaman or a Korean. 174 F. at

838.

Asian Indians were to be excluded from

naturalization, the United States

contended, "because many Englishmen treat

them with contempt and call them

•niggers.'" 174 F. at 838. The Justice

Department apparently agreed that the

Jewish people, like Turks or Syrians, had

their origins in Asia, but insisted that

Jews were "white" because they had

"become westernized and readily adaptable

to European standards." 174 F. at 841.

26

The federal decisions holding that

Arabs were not white relied primarily on

the fact that their native Syria had in

earlier times been occupied by the

Mongols, and more recently by the Turks,

who were then generally regarded as an

oriental race.11 Syrians were said to

have a complexion with "a yellow tinge

more characteristic of the Turk and

Mongol than the olive of southern

Europe." In re Dow. 213 F. at 3 62 .

While it was possible that some Arabs of

the region had no such oriental blood,

the court in Dow emphasized that "[t]here

is no known ocular, microscopic, Philo

logical, ethnological, physiological, or

historical test that can settle the race

11 In re Shahid. 205 F. 812, 816

(E.D.S.C. 1913); In re Dow. 213 F. 355,

361-62 (E.D.S.C. 1914); see also In re

Balsara. 171 F. 294, 295 (S.D.N.Y. 1909).

27

of the modern Syrian." 213 F. at 3 62.

The Syrian petitioner in Dow argued in

vain that Arabs were members of the same

Semitic family as Jews, whose eligibility

for naturalization had not been

questioned. The court reasoned:

The European Jew has become

racially, physiologically ,and

psychologically a part of the

peoples he lives among .... [N]o

one can tell how much so-called

Aryan blood runs in the veins of the

modern European Jew.... The Jew of

Northern Germany and Northern

Russian is frequently blue eyed and

fair haired.... But there are

communities professing the Jewish

religion in Northern Africa and the

east who are as dark as Negroes or

the peoples among whom they live,

and who probably by intermixture of

blood are physiologically the same.

The European Jew is as white as the

peoples among whom he lives and the

African or Asiatic Jew as dark....

A professing Jew from Syria who was

not of European nativity or descent

would be as equally an Asiatic as

the present applicant, and as such

not within the terms of the statute.

213 F. at 363.

Prior to Thind. however, the Justice

28

Department's litigation campaign was

largely unsuccessful. The decision in

Dow was reversed on appeal,12 and the

government prevailed in only two of the

reported cases in which it opposed the

naturalization of a non-oriental Asian.13

But Thind largely sustained the

government's interpretation of section

2169 and expressly spurned the suggestion

of the lower courts that all "Caucasians"

be deemed legally "white." 261 U.S. at

208-11. There was, this Court reasoned,

an obvious "racial difference" between

Hindus and European whites; white

Americans would react with "astonishment"

to any suggestion they belonged to the

12 Dow v. United States. 226 F. 145

(4th Cir. 1910).

13 In re Shahid and In re Singh

(E.D.pa. 1917), supra.

29

same race as Indians, Polynesians, or

"the Hamites of north Africa,"14 whose

complexion ranged "from brown to black."

261 U.S. at 211, 215. Although the

original "Aryan" invaders of India may

have been fair skinned, they had failed

"to preserve their racial purity" because

"the rules of caste ... seem not to have

been entirely successful." 261 U.S. at

213.

Thind concluded that Congress had

intended to limit the privilege of

American citizenship to the white peoples

of Europe — "bone of their bone and

flesh of their flesh." 261 U.S. at 213.

A decade later this Court explained that

under Thind "men are not white if the

strain of colored blood in them is a half

14 The Hamites are Arab inhabitants

of northern Africa.

30

or a quarter, or, not improbably, even

less ... Cf. the decisions in the days of

slavery." Morrison v. California. 291

U.S. 82, 86 (1934). Morrison noted that,

because of the "strain of Indian blood in

many of the inhabitants of Mexico as well

as in the peoples of Central and South

America," it was an "unsettled question"

whether Mexican immigrants were legally

white and thus eligible for

naturalization. 291 U.S. at 96 n. 5.

Few decisions of this Court since Dred

Scott v. Sanford. 60 U.S. 19 (1857) have

been as overtly racial in their reasoning

or conclusion.

Not content with having won in Thind

a prohibition against future

naturalization of non-European

immigrants, the Justice Department after

1923 embarked on a campaign to

31

denaturalize Indians, Arabs and Armenians

who had been formally naturalized as much

as 12 years earlier. Those singled out

for this vindictive action included the

chief research engineer of the General

Electric Corporation and an affluent

California attorney with a Ph. D.15 The

Justice Department insisted, usually with

success, that Thind had held "that

Asiatics generally ... were excluded as

racial groups, regardless of the origin

of their foundation stock or the

speculations of ethnologists."16 Relying

15 United States v. Gokhale. 26 F.

2d 360 (2d Cir. 1928) ; United States v.

Pandit. 15 F.2d 285 (9th Cir. 1926); see

also United States v. Cartozian. 6 F.2d

919 (D.Ore. 1925) ; United States v. Ali.

7 F.2d 728 (E.D.Mich. 1929), 20 F.2d 998

(E.D.Mich. 1927) ; United States v. Khan.

1 F.2d 1006 (W.D.Pa. 1924); Mozumdar v.

United States. 299 F. 240 (9th Cir. 1924) .

16 Brief for United States, Wadia

v. United States. 101 F.2d 7 (2d Cir.

1939), p. 6.

32

on Thind. several lower court cases held

that Arabs as a class were not white and

were therefore ineligible for

naturalization:

Apart from the dark skin of the

Arabs, it is well known that they

are a part of the Mohammedan world

and that a wide gulf separates their

culture from that of the

predominantly Christian peoples of

Europe. It cannot be expected that

they would readily intermarry with

our population and be assimilated

into our civilization.... Arabia,

moreover, is not immediately

contiguous to Europe or even to the

Mediterranean..17

It was not until after the outbreak of

World War II that the Immigration and

Naturalization Service, noting that then

recent events had made "disastrously

apparent” "the evil results of race

discrimination," ruled that Arabs were

17 In re Ahmed Hassan. 48 F. Supp.

843, 845 (E.D.Mich. 1942); see also

United States v. Ali. 7 F.2d 728, 732

(E.D.Mich. 1925) (emphasizing that skin

of Arab involved was "unmistakably dark").

33

legally "white," at least if they came

from areas outside the Asian Precluded

Zone.18

The position now advanced by

petitioners is of course precisely the

opposite of the ruling in Thind. but

petitioners1 arguments and .reasoning of

Thind are entirely consistent in

demonstrating the ease with which racial

myths and categories can be manipulated

to legitimize purposeful discrimination.

This Court has refused in the past to

permit such manipulation to eviscerate

the principle of non-discrimiation.

Texas authorities for over a century

regarded Mexican-Americans as a distinct

18 Immigration and Naturalization

Service, Monthly Bulletin, v. 1, No. 4,

pp. 12-16 (October 1943). The underlying

statute was finally repealed in 1952. 66

Stat. 239.

34

and inferior race;19 state forms asked

individuals to list their races as

"white,” "negro," or "Mexican,", Mexican-

Americans were directed by state

officials to use public facilities for

blacks rather than those for whites,

Mexican-American children were required

to attend separate segregated schools,

and Mexican-Americans were largely

19 Officials of other states also

regarded Mexican-Americans as a distinct

race. See, e.q. . State v. Martinez. 673

P.2d 441, 443, 105 Idaho 841 (1983);

Riqqin v. Dockweiler. 104 P.2d 367, 367,

15 Cal.2d 651 (1940); State v. Ouiqq. 155

Mont. 119, 147, 467 P.2d 692 (1970);

Herrera v. People. 87 Colo. 360, 361, 287

P.2d 643 (1930); Flores v. . McCoy. 186

Cal. App.. 2d 502, 504, 9 Cal.Rptr. 349

(1960) . See also 53 Cong. Rec. 4846

(remarks of Rep. Slayden) ("Down in the

Southwestern states ... we employ the

word 'Mexican' to define a race rather

than a nationality.") (1916); U.S.

Department of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, Fifteenth Census of the United

States, 1930, v.iii, parts 1 and 2 (1932)

(data on "Mexican race").

35

excluded from participation on juries.20

When the constitutionality of the latter

practice was challenged, however, the

Texas courts held, and the Attorney

General of that state argued in this

Court, that deliberate state

discrimination against Mexican-Americans

was entirely permissible because, they

asserted, the state's invidious racial

theories were simply mistaken; Mexican-

Americans, counsel for the state argued,

could be discriminated against because,

contrary to the belief which pervaded all

aspects of Texas policy, members of that

minority were "not a separate race" but

merely "white people of Spanish

20 Hernandez v. Texas. 347 U.S.

475, 479-80, 479 n. 9 (1954) ; Brief for

Petitioner, No. 406, October Term, 1953,

pp. 13, 37-41.

36

descent."21 In Hernandez v. Texas. 347

U.S. 475 (1954), this Court unanimously

rejected that brazen defense, and it

should do so again in the instant case.

II. SECTION 1981 PROHIBITS DISCRIMINA

TION ON THE BASIS OF ANCESTRY

A. Introduction

The central substantive problem

presented by this appeal is to determine

what the thirty-ninth Congress meant by

discrimination on the basis of "race".

The original language of section 1 of the

1866 Civil Rights Act provided that

"there shall be no discrimination in

civil rights or immunities ... on account

of race." 14 Stat. 27. Senator Trumbull,

in introducing the bill ultimately

enacted in 1866, described it as a

21 Hernandez v. State. 251 S.W. 2d

531, 535 (Tex. Crim. App. 1952); Brief in

Opposition, No. 406, October Term, 1953,

p. 12.

37

measure to protect "every race and

color". Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 211 (1866). The legislative

history of the act is replete with

references to "race" as the prohibited

basis of discrimination. McDonald v.

Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co. , 427

U.S. 273, 287-96 (1976).

Petitioners contend that the term

"race" in the 1866 Civil Rights Act, and

in the congressional debates of that

year, should be construed in the manner

in which that word would be used by a

late twentieth century ethnologist — to

refer to the 4 or 5 major divisions of

mankind currently recognized by

scientists, i.e., Caucasian, black,

oriental, and American Indian.22 The

22This narrow reading of section

1981 of the 1866 Act is necessarily

(continued...)

38

third circuit rejected that reading of

the language and history of section 1981,

reasoning that the framers of the 18 66

Act did not use the term"' race' ... in a

crabbed fashion or to signify only those

races identified by anthropologists as

distinct." (Pet. App. 22a). We believe

that the court of appeals was correct; we

maintain that the term "race" was

understood by the framers of the 1866

Civil Rights Act to refer to an

individual's ancestry, the ethnic group

to which he or she belongs.

Our contention that section 1981

forbids discrimination on the basis of

ancestry is not controlled by the 22

22(...continued)

inconsistent with this Court's decision

in Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission.

334 U.S. 410, 420 (1948), that section

1981 prohibits discrimination on the

basis of alienage.

39

conflicting dicta in this Court's past

decisions regarding whether section 1981

prohibits discrimination on the basis of

national origin.23 An individual's

ancestry, the ethnic group from which he

and his ancestors are descended, is not

necessarily the same as that individual's

national origin, the country from which

the individual or his forbearers

23 Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. .

392 U.S. 409, 413 (1968), asserts in

dicta that section 1982 does not forbid

discrimination on the basis of national

origin. In Yick Wo v. Hopkins. 1218 U.S.

356 (1886), on the other hand, the Court

observed that the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibited discrimination on the basis of

race, color, or nationality, and that

"[i]t is accordingly enacted ... that

'All persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States shall have the same

right to make and enforce contracts

...,'" quoting section 1981. 118 U.S. at

369 (emphasis added). See also United

States v. Wong Kim Ark. 169 U.S. 649,

695-96 (1898). Most recently Delaware

State College v. Ricks. 449 U.S. 250, 256

n. 6 (1980) , regarded the issue as an

open question.

40

emigrated to the United States. Although

an individual1s ancestry and national

origin are in some instances identical,

as in the case of a Greek from Greece,

that often is not the case. Some

distinct groups, such as Arabs, Jews, and

gypsies, have lived in and emigrated to

the United States from a large number of

different countries. Other groups, such

as the Welsh or the Basques, constituted

a distinct minority within their native

lands, and were not in modern times part

of a distinct Welsh or Basque nation.

Even where an ethnic group constitutes

the primary stock of one country, members

of the same group may also be native to

other nations; there are indigenous

Hungarians in Rumania and Irishmen in the

United Kingdom. Thus an employer which

had no policy of discriminating on the

41

basis of national origin against

immigrants from the United Kingdom could

conceivably discriminate on the basis of

ancestry against an Irishman from

Belfast, a Jew from London, or a Welshman

from Cardiff. In the instant case the

district court expressly noted that

respondent's national origin, Iraqi, was

different than his ancestry, Arabian.

(Pet. App. 38a).

Nor is our proposed construction of

section 1981 precluded simply because of

the existence of Title VII. Petitioners,

although conceding as they must that

Title VII did not repeal section 1981 in

its entirety, urge that section 1981

should be construed narrowly in light of

the availability of other remedies under

Title VII. (Pet. Br. 20-21, 39-40). But

to interpret section 1981 in a more

42

constricted manner than would have been

appropriate had Title VII not been

enacted would be to violate the express

intent of Congres "that the two

procedures augment each other and ... not

[be] mutually exclusive." Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency. 421 U.S. 454, 459

(1975). Section 1981 provides a number

of important remedies and procedures not

available under Title VII. First, the

retrospective relief provided to a

complainant in a section 1981 action is

not limited to equitable back pay, but

includes both actual and punitive

damages. Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency. 421 U.S. at 460. Second,

although both Title VII and section 1981

prohibit racial harassment of an

employee, Title VII provides no monetary

remedy for a harassed employee who lost

43

no income as a consequence of that

discrimination; the only monetary redress

available for any mental suffering in

such a case must come under section 1981.

Third, in a section 1981 action for

compensatory relief, unlike a Title VII

for back pay action, the plaintiff would

be entitled to a jury trial; if the

plaintiff seeks relief under both section

1981 and Title VII for the same alleged

discrimination, the Seventh Amendment

requires the trial judge adjudicating the

Title VII claim to defer to the liability

findings of the jury in the section 1981

action. Beacon Theatres v. Westover. 359

U.S. 500 (1959).

If, as we urge, the section 1981

prohibition against racial discrimination

encompasses a ban on discrimination on

the basis of ancestry, dismissal of

44

respondent's claim was necessarily

improper. The district court expressly

and correctly acknowledged that

respondent had claimed that he had been

discriminated against because of his Arab

ancestry. (Pet. App. 38a). Similarly,

the anti-Semitic incident in Shaare

Tefila was manifestly based on the Jewish

ancestry of the individual petitioners

and other members of the petitioners1

synagogue, rather than on their religious

views. As one amicus has observed, most

anti-Semitism during the last century has

been based on the ancestry and purported

"racial” character of the Jewish people24

24 See also Mavers v. Ridlev. 465

F.2d 630, 631 n.l (D.C. Cir. 1972) (en

banc) (quoting restrictive covenant

forbidding sale or lease of property "to

any person of the Semitic race, blood or

origin, which racial description shall be

deemed to include Armenians, Jews,

Hebrews, Persians and Syrians....)

45

rather than on theological differences

with the religious tenets of Judaism.25

We ground our proposed

interpretation of section 1981 on four

distinct arguments. First, we urge that

because the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibits discrimination on the basis of

ancestry, the 1866 Civil Rights Act

should be read in the same manner, since

the Congress which adopted both measures

understood them to contain similar

prohibitions. (Pp. 46-49, infra).

Second, we contend that during the

nineteenth century "race" had a meaning

similar to "ancestry" or "ethnic group"

in modern English, and that Arabs and

Jews, for example, were commonly referred

to as races. (Pp. 50-73, infra). Third,

25 Brief Amicus Curiae of the Anti-

Defamation League, etc., et al., p. 15.

46

we argue that the framers of section 1981

used the term "race" in this manner, and

expressly intended that statute to

prohibit discrimination by the Know

Nothings against particular white ethnic

groups, such as "the German race.” (Pp.

73-88, infra). Finally, we suggest that

the interpretation of section 1981

proposed by petitioners would be

unworkable in practice. (Pp. 88-103,

infra).

B. The 1866 Civil Rights Act and the

Fourteenth Amendment

The non-discrimination principle

embodied in the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment has never

been tied to any technical ethnological

meaning. This Court has repeatedly held

that the equal protection clause forbids

discrimination on the basis of

47

ancestry.26 Hirabavashi v. United

States. 320 U.S. 81 (1943), which first

ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment

forbids discrimination on account of

ancestry, was expressly premised on the

view that discrimination on the basis of

ancestry constitutes racial

discrimination within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment:

Distinctions between citizens solely

because of their ancestry are by

their very nature odious to a free

people whose institutions are

founded upon the doctrine of

equality. For that reason, legisla

tive classification or discrimina

tion based on race alone has often

been held to be a denial of equal

protection. 320 U.S. at 100.

(Emphasis added).

26 Fullilove v. Klutznick. 448 U.S.

448, 491 (1980) (discrimination on the

basis of "ethnic criteria"); Hernandez v.

Texas. 347 U.S. 475, 479 (1954)

(discrimination on the basis of

"ancestry"); Ovama v. California. 332

U.S. 633, 646 (1948) (discrimination on

the basis of "ancestry"); Hirabavashi v.

United States. 320 U.S. 81, 100 (1943).

48

If, as Hirabavashi reasoned, the

"racial" discrimination prohibited by the

Fourteenth Amendment encompasses discrim

ination on the basis of ancestry, it

would be surprising indeed if the 1866

Civil Rights Act's similar prohibition

against racial discrimination, enacted

less than three months before Congress

approved the Fourteenth Amendment, had

any different meaning. The fact that the

Fourteenth Amendment itself prohibits

discrimination on the basis of ancestry

is weighty evidence that the 1866 Civil

Rights Act does so as well:

In considering .. . the kind of

governmental action which the first

section of the Civil Rights Act of

1866 was intended to prohibit,

reference must be made to the scope

and purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment; for that statute and the

Amendment were closely related both

in inception and in the objectives

which Congress sought to achieve...

It is clear that in many significant

49

respects the statute and the

Amendment were expressions of the

same general congressional policy.

Hurd v . Hodge. 334 U.S. 24, 32 (1948).

The thirty-ninth Congress adopted the

Fourteenth Amendment in part to assure

that the Civil Rights Act's prohibition

against government discrimination could

not be repealed by a simple majority of a

later Congress. Section one of the

Amendment, Representative Thayer noted,

was "but incorporating in the

Constitution of the United States the

principle of the civil rights bill which

has lately become law."27

27 Cong Globe, 39th Cong.,

Sess., 2465 (1866).

1st

50

B. The Etymology of the Word "Race11

When Congress frames a statute with

words which enjoy a meaning familiar and

intelligible to ordinary members of the

public, the statute must be interpreted

in light of that common understanding,

not on the basis of some possibly

different definition used by scientists.

Mail lard v. Lawrence. 54 U.S. (16 How.)

251, 261 (1853). The interpretation of

statutes enacted a century or more ago

requires particular caution, for the

words chosen by Congress, like any other

part of the English language, may have

had a significantly different common

meaning 50 or 100 years ago than they do

today. The word "race" is a term whose

meaning has indeed changed substantially

over the course of the last 150 years.

We set out in Appendix E the definitions

51

of "race" contained in 50 dictionaries

published between 1750 and 1985.28 As we

explain at length below, this Appendix

demonstrates that the term race has had

three quite distinct meanings over that

period of time — in 1800 "race" meant

"family", between roughly 1850 and 1950

"race" was generally understood to denote

an individual's ancestry or ethnic

background, and only in the last several

decades has "race" been widely understood

among laymen to refer to one of the 4 or

5 basic divisions of mankind. Prior

to 1850 the primary meaning of "race" was

family. Samuel Johnson's 1768 Dictionary

of the English Language defines race as

28 A chronological list of the

dictionaries cited is set forth in

Appendix D. The brief citations which

follow refer to the author or title and

date of publication; the full citation

can be found in that appendix.

52

"[a] family ascending ... [a] family

descending ... a collective family." The

first edition of Noah Webster's American

Dictionary, published in 1830, defines

race as " [t]he lineage of a family, or

continued series of descendants from a

parent who is called the stock." In

Alfred Lord Tennyson's 1832 poem

"Locksley Hall" the protagonist uses the

term in this sense, declaring "I shall

take some savage woman, and she shall

rear my dusky race".29 Consistent with

this meaning, the most common definition

of "kinsman" until early in the twentieth

century was "man of the same race";

"kin," "kinfolk" and "kindred" were

29 A. Tennyson, Poems. 282 (1853).

The reference appears to be to an Asian

Indian woman; an earlier line refers to

"Mahratta," (Maratha), a people and

region of south central India. The

protagonist of the poems is an

Englishman.

53

similarly defined as referring to persons

of "the same race". See Appendix F.

"Race" was frequently given as a synonym

for "family," "lineage," and "progeny."

See Appendices G, H, I. "House", which

at times still denotes a family ("The

House of Windsor"), was also defined as a

"race". See Appendix J.

The use of the term race to refer to

an ethnic group dates from at least

160030, but it appears to have been

relatively uncommon until the middle of

the nineteenth century. The earliest

instance in which any English language

dictionary clearly utilized "race" in

this sense appears to be the 1830 edition

of Websters, which defines gypsies as "a

30The Oxford English Dictionary cites

references to "the British race" (c.

1600), the "Pigmean race" (1667), and

"Troy's whole race" (1713). V. 8, p. 87

(1933) .

54

race of vagabonds which infest Europe,

Africa and Asia." Four other

dictionaries published prior to 1850 also

refer to gypsies as a "race", a usage

which may well reflect the fact that the

small bands of gypsies more closely

resembled families than the large ethnic

groups that would later be characterized

as races. See Appendix K. The other

- ethnic group to be defined as a race

prior to 1850 was the Semites.31

American dictionaries published in 1846

and 1855 expanded the definition of

"race" to include "ancestry" as well as

"family,"32 and the definition of race in

the 1876 edition of Websters was altered

to include a "tribe, people, or nation,

believed or presumed to belong to the

31Worcester (1846), p. 656.

32Id., p. 585; Smalley (1855) p. 381.

55

same stock.”33 After 1840 "race" also

begins to appear as a synonym for words

which clearly refer to groups larger than

blood relatives, such as stock34,

tribe35, and even nation36.

The use of the term race to refer to

an individual1s ethnic background is

clearly reflected in the encyclopedias of

the era. The 1854 edition of the

Encyclopedia Americana. for example,

explained in a description of northern

Africa:

33Webster (1876), p. 589.

34Reid (1846), p. 391; Worcester

(1846), p. 698; Bolles (1847), p. 715;

Smallev (1855), p. 506.

35Reid (1846), p. 420; Worcester

(1846), p. 754; Boaq (1847), p. 1357;

Craig (1849), p. 920; Smallev (1855), p.

571.

36 Clark (1855), p. 255 (nation

defined as "a great body of people born

of the same race, as the English in

England and America”).

56

The Arab natives are, for the most

part, a wandering race, dwelling in

tents . . . Their business is war;

their income is plunder. (V. 1, p.

563) (Emphasis added).

Amongst the Berbers, the encyclopedia

explained, "[a]11 the branches of this

race are distinguished by beards." (v.l,

p. 563) (emphasis added). The Bedouins

were "a numerous Mohammedan race, which

dwells in the deserts of Arabia, Egypt

and Northern Africa" (v. 2, p. 79)

(emphasis added), and the Copts of Egypt

were "evidently a distinct race" (v.3, p.

526) (emphasis added). The description

of "Hebrews", although less perjorative

than the discussion of Arabs, was equally

racial;

This singular people ... presents

the wonderful spectacle of a race

preserving its peculiarities of

worship, doctrine, language and

57

feelings in a dispersion of 1800

years over the whole globe.37

The Encyclopedia____ Americana also

characterized as distinct races Finns,

gypsies, "Hindoos", Basques, Sclavonians,

Tatars, Georgians, and Samoiedes.38

The New American Cyclopaedia.

published in the years 1858-63, refers to

Arabs as a race in nine different

entries,39 and characterized the Arab

peoples as comprised in turn of a number

of subsidiary races:

[T]he various races and tribes known

collectively as Arabs comprise

37V .6, p. 209 (emphasis added).

Another passage characterized Jews as a

race. V.ll, p. 118.

38 V. 5, p. 123; v.6, pp. 123, 333-

4; v.ll, p. 118. "Samoiedes" appears to

be a reference to the Samoyeds, a people

inhabiting northeastern European Europe

and northwestern Siberia.

39V . 1, p. 739; v.2, p. 610; v.3, p.

158; v. 5, p. 697; v.7, p. 34; v.9, p.

742; v. 13, p. 159; v. 15, pp. 603, 653.

58

nearly seven-eights of the

population [of Arabia]. Of the

Arabs... the ... Bedouins are a

wandering race, living in tents and

moving in troops from place to

place.40

[T]he Berbers are an interesting

race ... [r]ude, warlike, and

nomadic.41

[T]he Copts are beyond question the

best representatives of the ancient

Egyptian race42.

Druses ... [are] a race and a

religious sect of Syria, chiefly in

the southern ranges of Lebanon43.

The Jews were described as "a people of

the Semitic race".44 The New American

Cyclopaedia refers in all to more than 20

40 v.i, P- 739 (emphasis added).

41 V. 3 , P- 158 (emphasis added).

42 V. 5, P- 697 (emphasis added).

43 V. 6, P- 630 (emphasis added).

44 V. 9, p. :27; see also v.2r

610 (Jews one of the six races inhabiting

the Barbary states), v.ll, p. 742 (Jews

one of the six races inhabiting Morocco),

v.15, p. 603 (Jews one of the seven races

inhabiting Tripoli).

59

different ethnic groups as constituting

races, including Afghans, Celts, Danes,

Swedes, Norwegians, Germans, Greeks,

Italians, Wallachians, Magyars, Persians,

Kurds, Spaniards, Portuguese, Russians,

Turks, and Tatars.45

The 1878 American edition of the

Encyclopedia Britannica also used "race"

to refer to what we would now describe as

ethnic groups:

The origin of the Arab race ... can

only be a matter of conjecture ...

[T]he first certain fact is the ...

division of the Arab race into two

branches, the "Arab", or pure; and

the "Mostareb", or adscititious.46

BARBARY ... The name is derived from

the Berbers, one of the most

45 V. 1, p. 166; V . 4, p. 638; V . 6 ,

p. 382; V . 7, pp. 335-37, 655; v.9, p.

335-6; v.13, pp. 159-60, 506; v.14, pp.

225-26, 804; V.15, pp. 216, 264, 603, 653.

46V.2, p. 245 (emphasis added); see

also v.1, p. 564.

60

remarkable races in the region.47

The Druses are a mysterious people

. .. The mere fact that they possess

a knowledge of the Celestial Empire

in such contrast to the geographical

ignorance of the other Syrian races

is in itself remarkable ... the rise

and progress of the religion which

gives unity to the race can be

stated with considerable

precision.48

Jews were expressly referred to as a

race, as were Afghans, Turks, Germans,

Poles, Croatians, Servians, Danes, Finns,

Germans, Hungarian, Greeks, Albanians,

and the Persians.49

The definition of "race" urged by

petitioners, denoting one of a small

number of branches of mankind, does not

appear in an English language dictionary

47V.4, p. 363 (emphasis added); see

also v.1, p. 564.

48v .7, p. 483

49v,. 1, pp. 23 6, 564; V . 3 , P- 118;

V.7, P- 84; v. 9, p. 216; v.10, P- 473 ;v. 11, P- 83; V.12, p. 365; v.18, p. 627.

61

until the publication at the turn of the

century50 51 of the Century Dictionary and

Cyclopedia. The eight volume Century

Dictionary expressly distinguished three

separate meanings of the word "race":

(1) "[a] geneological line .

family; kindred;" (2) "[a] tribal or

national stock ... as, the Celtic race;

the Finnic race ...; the English, French

and Spani[sh] ... races;" and (3) "a

great division of mankind ... as, the

Caucasian race.1,51 The editors of the

Century Dictionary made clear by their

own use of words, however, that they

regarded the second meaning as the most

50 Counsel for respondents were able

to locate a 1911 edition of this multi

volume publication. There appears to

have been an 1891 edition, but we have

not been able to locate a copy ascertain

its contents.

51 V. 8,

original)

p. 4926 (emphasis in

62

widely used and accepted. Thus in other

definitions the Century Dictionary refers

to "[t]he English race," "the Arabic

race," "the ancient Egyptian race or

races," "the Irish race," "the Italian

race," "the French race," "the Spanish

race," "the German race," "the Hungarian

race," "the Greek race," "the Finnic

race," "the Slavic race," "the native

race of India," "the races speaking

Iranian languages," and "a race

inhabiting Kafiristan."52 A Moor was

described as "[o]ne of a dark race

dwelling in Barbary ... a mixed race,

chiefly of Arab and Mauritanian origin",

and "Semitic" was defined as "pertaining

to the Hebrew race or any of those

52 V. 1, p. 214; v. 3, pp. 1856,

1933; V. 4, pp. 2226, 2373, 2499, 2614,

2823; V. 5, pp. 2920, 3058, 3180, 3202,

3261; v. 8, pp. 5279, 5794.

63

kindred to it, as the Arabians...."53

The definition of race in the 1876

edition of Webster1s. quoted earlier,

remained essentially unchanged for 40

years. In 1916 the editors for the first

time noted that the term had acquired a

new scientific meaning in addition to the

meaning understood by laymen. The

additional entry read "6. Ethnol r ocrvl .

A division- of mankind possessing constant

traits, transmissible by descent,

sufficient to characterize it as a

distinct human type." But the editors

themselves continued to use "race" in the

popular sense of ethnic group. Thus an

Iraq was defined as "[0]ne of the natives

of Iraq, chiefly of the Arabic race", and

a Hamite was defined as "[a] member of

53 V. 6, p. 3852; V. 8, p. 5487.

64

the chief race of North Africa."54 Among

the definitions of "race" in the other

dictionaries published between the turn

of the century and 1940, four do not

include division of mankind as an

alternative meaning, two characterize

that meaning as a use peculiar to

ethnologists, and only one characterizes

that meaning as found common parlance.55

The editors of all of these dictionaries,

moreover, continued themselves to use the

word race to refer to ethnic groups.56

54 Webster (1916), pp. 450, 532; see

also id. at 224 (Copt) , 472 (Hindu) , 510

(Indian), 740 (Persian).

55 Price (c. 1899) , 608 (no such

meaning); Chambers (1908) 762(no such

meaning); Skeat (1910) 494 (no such

meaning); Winston (1919) , 502 (an

alternative meaning); Weekley (1921),

1190 (no such meaning); Universal (1932),

955 (ethnological term).

56 See, e.q.. Winston (1919) pp.

21, 28, 56, 135, 273, 342, 346, 502.

65

World War II marks the beginning of

a decided shift in the common usage of

the term race. Virtually all English

dictionaries published after 1940 offer

"division of mankind" as a possible

meaning of "race", and in most instances

this is a popular rather a scientific

definition, although the earlier

definition of race as "stock",

"ancestry", or "ethnic group" remains.57

Among dictionaries published during the

1940's, references to ethnic groups as

"races" continue, but those groups are

referred to with equal frequency as

57 Thorndike (1941), p. 751 (common

meaning); Odham (1946), p. 862 (common

meaning); Funk and Waanalls (1947), p.

964 (common meaning); Thorndike-Barnhart

(1955), p. 639 (common meaning); Random

House (1966) , p. 1184 (ethnology) ;

Webster1s (1985), p. 969 (common

meaning); but see American College