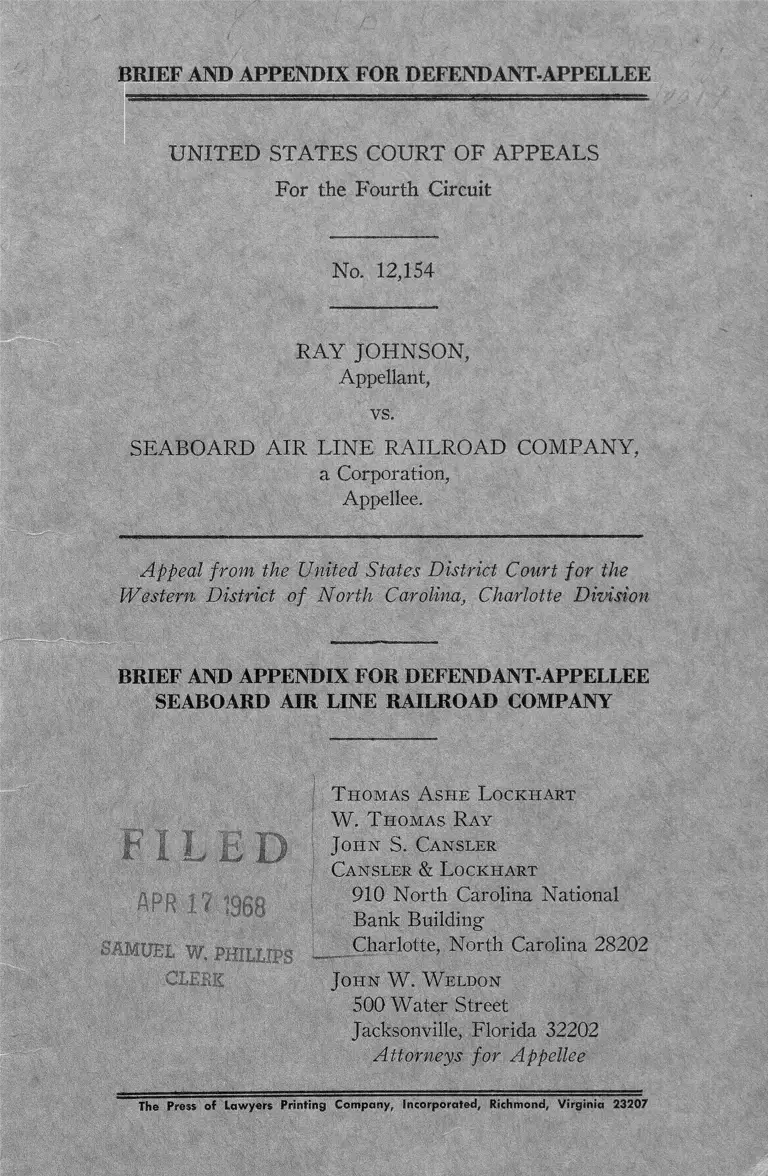

Johnson v. Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company Brief and Appendix for Defendant-Appellee

Public Court Documents

April 17, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company Brief and Appendix for Defendant-Appellee, 1968. 3168751a-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/688bc736-5810-45b0-a614-a0e694fae100/johnson-v-seaboard-air-line-railroad-company-brief-and-appendix-for-defendant-appellee. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLEE

U N IT E D STA TES COURT O F A PPEA LS

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 12,154

RAY JOH N SO N ,

Appellant,

vs.

SEABOARD A IR L IN E RAILROAD COMPANY,

a Corporation,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District o f North Carolina, Charlotte Division

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLEE

SEABOARD AIR LINE RAILROAD COMPANY

APR 17 1968

;■ ViMUEL W. PHILLIPS

CLERK

T h om a s A s h e L o ckhart

W . T hom as R ay

J o h n S. Ca nsler

Ca nsler & L ockhart

910 North Carolina National

Bank Building

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J o h n W . W eldon

500 W ater Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Appellee

The Press of Lawyers Printing Company, Incorporated, Richmond, Virginia 23207

INDEX

PAGE

QUESTIONS PRESENTED............................................................. 2

STATEMENT OF FACTS............................................................... 2

ARGUMENT

I OPENING STATEMENT........... .. ........................... 7

II THE PROCEDURES ESTABLISHED BY

CONGRESS IN THE ACT TO AFFORD

THE COMMISSION THE OPPORTUNITY

TO ATTEMPT BY ADMINISTRATIVE

ACTION TO CONCILIATE UNLAWFUL

EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES WITH A

VIEW TO OBTAINING VOLUNTARY

COMPLIANCE HAVE NOT BEEN MET

AND THE COURT IS WITHOUT JURIS

DICTION TO CONSIDER JOHNSON’S

MULTIPLE CAUSES................................................. 8

III CONCLUSION............................................................ 15

APPENDIX

December 10, 1965 letter from Railroad to J o h n so n ................ 19

January 1, 1966 letter from Johnson to Commission................ 20

August 8, 1966 letter from Commission to R a ilro a d ........... .. . 23

Affidavit of S. M. Duffer, September 22, 1967 ......................... 23,24

Supplemental Affidavit of C. E. Mervine, Jr., and

Exhibit A th e re to .................................................................... 25,26,27

PAG E

TABLE OF CITATIONS

CASES

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F. Supp. 776, 1967 . . . . 14

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company, et al.,

Defendants. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Inter-

venor. 265 F. Supp. 56, 1967 ...................................................7,10,13

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc. and Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, Intervenor, 268 F. Supp. 29, 1967 . . . 11

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, 251 F. Supp. 184, 1966........... 10

Mickel v. South Carolina State Employment Service andxor

Exide Battery Service, 377 F. 2d 239, 1967 .................................7,8

Moody, et al. v. Albemarle Paper Company, et al., and Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, 271 F. Supp. 27, 1967 12, 13

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842, 1967 . . . . 12,13

Stebbins v. Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company, 382 F.

2d 267, 1967 ........................................................................................ 8

In The

U N ITE D STA TES COURT OF A PPEA LS

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 12,154

RAY JOHNSON,

Appellant,

vs.

SEABOARD AIR L IN E RAILROAD COMPANY,

Appellee.

Appeal by Plaintiff from the United States District Court

for the Western District o f North Carolina

Charlotte Division

Honorable Woodrow W . Jones, Judge Presiding

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANT, SEABOARD AIR LINE

RAILROAD COMPANY

2

Q U ESTIO N PR ESEN TED

Where the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission1

gave notice to Ray Johnson2 it had neither undertaken nor

concluded conciliation efforts with respect to Johnson’s

charge, that the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company3

had violated Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 19644 in

dismissing Johnson from Railroad’s employ, did the Trial

Judge err in dismissing Johnson’s civil action on the ground

that resort to the remedy of conciliation is a jurisdictional

prerequisite to the right to file and maintain a civil action

under the Act?

STA TEM EN T OF FACTS

Johnson was discharged as an employee of the Railroad

on December 10, 1965, “for conduct unbecoming an em

ployee and conduct bringing discredit on” the Railroad,

as developed in the formal investigation held on November

29, 1965 in Atlanta, Georgia (Defendant’s Appendix,

hereinafter referred to as “D X ”, (p, 1).

Johnson was present at the Railroad’s investigation of

the charge he had been convicted of drunk driving, and he

was furnished with a copy of the transcript of the pro

ceedings (R. pp. 98-107).

1 hereinafter called “Commission”'.

2 hereinafter called “Johnson”.

8 hereinafter called “Railroad”.

4 hereinafter called “Act”.

3

By letter dated January 1, 1966, Johnson complained to

the Commission,

i ( >}c 5jc 3jc

“I feel that the dismissal is a denial of my constitu

tional rights as guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the U. S. Constitution and Title V II

of the Civil Rights Law—the section on Prohibited

Employer Practices.

“I am respectfully asking for an investigation of the

causes for my dismissal and your aid in a fight for

reinstatement.

Yours truly,

Ray Johnson”8

By Decision dated July 18, 1966, the Commission found,

“Summary of Charges

“The Charging Party, a Negro, alleges discrimination

on the basis of race in that he was discharged for filing

complaints with various federal agencies protesting the

discriminatory treatment given him as a porter in the

Respondent Company’s employ.

* * *

“Decision

“There is reasonable cause to believe that the Re

spondent violated Title V II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 in dismissing the Charging Party from its

employ.”6

6 full text of Johnson’s letter appears “DX”, p. 20.

6 full text of Commission Decision found in Plaintiff’s Appendix, hereinafter

referred to as “PX”, pp. 3a-5a.

4

By letter dated August 8, 1966, the Commission in

formed the Railroad of its Decision and told the Railroad,

* *

“A conciliator appointed by the Commission will con

tact you soon to discuss means of correcting this dis

crimination and avoiding it in the future.

* *”7

According to the uncontradicted Affidavit of the Railroad’s

Director of Personnel, S. M. Duffer, dated September 22,

1967, immediately before oral argument and submission

of this case to the Trial Judge on September 27, 1967,

no conciliator had contacted the Railroad with respect

to the alleged unlawful employment practice, and there had

been no effort whatever at conciliation by the Commission,

contrary to the Commission’s letter to the Railroad ap

proximately fourteen months prior thereto. (See Affidavit,

DX, pp. 22-23).

The Commission wrote Johnson two letters dated August

:8, 1966, one letter informed Johnson of the Commission’s

finding of “reasonable cause” to believe the Railroad had

■engaged in an unlawful employment practice in dismissing

him from the Railroad’s employ, and in that letter the

Commission told Johnson the Commission will,

“* * * attempt to eliminate this practice by con

ciliation as provided in Title VII. * * *”8

In the Commission’s other letter to Johnson the same day

the Commission told Johnson,

7 full text of letter appears DX, p. 21.

8 full text of letter appears PX, p. 6a.

5

“Due to the heavy workload of the Commission, it has

been impossible to undertake or to conclude conciliation

efforts in the above matter as of this date. However,

the conciliation activities of the Commission will be

undertaken and continued. * * *’'9

On September 7, 1966, Johnson instituted the present

cause alleging his discharge by the Railroad in violation o f

the Act and praying the Court to order his reinstatement in

employment with the Railroad. In addition, Johnson

purports to bring a class action “on his own behalf and on

behalf of others similarly situated” and alleges multiple

acts of discrimination by the Railroad against “other Negro

employees and members of plaintiff’s class with respect

to the terms, wages, conditions, privileges, advantages and

benefits of employment with defendant, to wit:

A. Negro employees are hired primarily for and re

stricted to the job classification of train porter and are

paid lower wages and denied privileges and benefits of

employment given to white employees performing the

same or similar jobs.

B. Defendant maintains separate lines of seniority for

Negro and white employees and denies Negro em

ployees the opportunity of advancement to higher pay

ing positions and conditions of employment, the design,

intent, purpose and effect being to continue and pre

serve the defendant’s long standing policy, practice,

custom and usage of limiting the employment and pro-

9 full text of letter appears PX, pp. la-3a. 10

10 Johnson’s Complaint, sub-paragraph D of paragraph VII and paragraph 2

of the prayer for relief, PX, pp. 10a, 12a.

6

motional opportunities of Negro employees of the de

fendant because of race or color.

C. Defendant maintains separate facilities and con

ditions for its Negro and white employees, the design,

purpose and effect being to maintain and perpetuate

the separate job opportunities, conditions and priv

ileges of the employees on the basis of race and

color.”11

The pertinent portions of the Act necessary to consider

this case are,

“§2000e-5. Enforcement provisions— Charges by per

sons aggrieved or member of Commission;

copy of charges to respondents; investiga

tion of charges; conference, conciliation,

and persuasion for elimination of unlawful

practices; prohibited disclosures; use of

evidence in subsequent proceedings; pen

alties

(a ) Whenever it is charged in writing under oath by

a person claiming to be aggrieved * * * that an

employer * * * has engaged in an unlawful employ

ment practice, the Commission shall furnish such em

ployer * * * with a copy of such charge and shall

make an investigation of such charge, provided that

such charge shall not be made public by the Com

mission. If the. Commission shall determine, after such

investigation, that there is reasonable cause to believe

that the charge is true, the Commission shall endeavor 11

11 Johnson’s Complaint, paragraph VII and sub-paragraph A, B and C

thereof, PX, p. 9a.

7

to eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment

practice by informal methods of conference, concilia

tion, and persuasion. * * * (emphasis added)

;{< >{s

(e) If within thirty days after a charge is filed with

the Commission * * *, the Commission has been un

able to obtain voluntary compliance with this sub

chapter, the Commission shall so notify the person

aggrieved and a civil action may, within thirty days

thereafter, be brought against the respondent named in

the charge (I ) by the person claiming to be ag

grieved * * *”

ARGUM ENT

I

O PEN IN G STA TEM EN T

The Trial Judge, himself a former member of the Con

gress, assiduously studied the voluminous briefs filed in the

trial court and conducted his own research as to (1) the

purposes of the Act, (2) the remedies provided by the Act,

and (3) the Congressional intent in its enactment, and he

reached the same general conclusion as did the court in

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company, et al,

265 F. Supp. 56 at 61 (1967), that “some effort or attempt

to obtain voluntary compliance, however minimal” is a

jurisdictional prerequisite to suit in the federal courts. This

Circuit has held that conciliation efforts are a part of the

administrative remedy prescribed by the Act, citing and

discussing the Dent case with approval, in Mickel v. South

Carolina State Employment Service and/or Exide Battery

8

Service, 377 F.2d 239 (1967) and Stebbins v. Nationwide

Mutual Insurance Company, 382 F.2d 267 (1967). Hence,

the Memorandum of Decision and Order appealed from are

consistent with the rule in this Circuit, that an aggrieved

party must exhaust administrative remedies before going

to court, and Judge Jones did not err in dismissing John

son's civil action on the facts of this case.

W e ask the Court to keep in mind (1) that Johnson’s

charge to the Commission in the first instance, (2) the

Commission's Summary of the Charges, and (3) the

Commission’s Decision, all were concerned solely with

Johnson’s dismissal from the employ of the Railroad. How

ever, when the suit was filed Johnson’s dismissal and rein-

tatement are a minor part of his complaint, the overwhelm

ing thrust of which consists of broadside allegations of

essentially every defined unlawful employment practice an

employer could possibly engage in because of an individual’s

race. See 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(a).12

II

T H E PRO CED U RES ESTA B LISH ED BY CON

GRESS IN T H E ACT TO A FFO R D T H E COMMIS

SION T H E 'O PPO R TU N ITY TO A TT EM PT BY

A D M IN ISTR A TIV E ACTION TO CONCILIA TE

U N LA W FU L EM PLO Y M EN T PRA CTICES W IT H

A V IEW TO O BTA IN IN G V OLUNTARY COM

PLIA N CE H A V E NOT BEEN M ET AND T H E

•COURT IS W IT H O U T JU R ISD IC TIO N TO CON

SID ER JO H N SO N ’S M U L TIPLE CAUSES.

12 see again Johnson’s January 1, 1966 letter to the Commission, the Com

mission’s Decision of July 18, 1966, and sub-paragraphs A, B and C of

paragraph VII of the complaint, the pertinent portions of which appear in the

.Railroad’s Statement of Facts, supra.

9

The first opportunity this Circuit had to consider Section

706 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5

was in the Mickel case where the plaintiff had made a

charge to the Commission of a violation of the Act by a

state employment agency, and then sued both the agency

and the purported employer. The Court could have de

cided and disposed of the Mickel case on either of two

preliminary questions, (1) whether a party to a suit under

the Act must have been the “respondent named in the

charge filed with the Commission”, or (2) whether the

employment agency against whom the charge was filed

with the Commission was the agent of the prospective em

ployer for purposes of filing the charge with the Commis

sion under the Act. However, this Court went considerably

further than these questions and examined into, as did the

Trial Judge below, the purpose of the Act and the Con

gressional intent. This Court acknowledged the dual pur

pose of the Act, namely conciliation first, and coercion

second when it said,

“Congress has provided that persons aggrieved by

unlawful practices should first attempt to have the

Commission settle the matter in an atmosphere of

secrecy without resorting to the extreme measure o f

bringing a civil action in the congested federal courts.”

(emphasis added)

By the above statement we understand this Court is

saying that Congress was anxious to effect compliance

with the various provisions of the Act on a voluntary basis

and that resort to the coercive atmosphere of the courts

should be had only after efforts at voluntary compliance

have failed.

10

This Court in the Mickel case also recognized and

adopted the underlying principle of the Dent case, that

conciliation attempts are a jurisdictional prerequisite to the

institution of a civil action under the Act, when it said,

“In a recent well-considered case, Dent v. St. Louis -

San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F.Supp. 56 (N.D. Ala.

Mar. 10, 1967), it was held that, conciliation attempts

were a ‘jurisdictional prerequisite to the institution

of a civil action under Title V II and that the actions

instituted without this prerequisite must accordingly

be dismissed.’ The court dismissed an action under

Title V II because plaintiff had not resorted to the

Commission’s conciliation procedures prior to court

action. This conclusion also finds support in Hall v.

Werthan Bag Corporation, 251 F.Supp. 184 (M.D.

Tenn. 1966).”

That Congress intended exhaustion of administrative

remedies within the Commission by persons claiming dis

crimination in employment prior to bringing civil actions

is abundantly clear from the research of the courts in Dent

and Mickel, where in the latter the Court said,

“The decision in Dent, supra, 265 F.Supp. 56, pains

takingly discusses the legislative history of this portion

of the Civil Rights Act. The opinion presents over

whelming authority culled from Congressional com

mittee reports and the statements of key legislators

to support the conclusion that Congress intended that

persons claiming discrimination in employment should

first exhaust their remedies within the Commission

created for that purpose. Furthermore, the original

bill contained a clause permitting the bringing of civil

11

actions prior to seeking conciliation but this provision

was eliminated by a blouse amendment in order to

insure that conciliatory efforts would be made.4”13

The only other reported decision of this Court directly

dealing with the question presented in this appeal is the

Stebbins case where before Circuit Judges Sobeloff, Bryan

and Winter, in a Per Curiam opinion affirming summary

judgment against a Negro employment applicant, the Court

said it had reviewed both the legislative history of the

Act, as well as its language, and concluded,

“* * * Congress established comprehensive and de

tailed procedures to afford the EEOC the opportunity

to attempt by administrative action to conciliate and

mediate unlawful employment practices with a view

to obtaining voluntary compliance. The plaintiff must

therefore seek his administrative remedies before

instituting court action against the alleged discrim

inator.” 382 F. 2d 267 at 268.

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc. and Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission, 268 F. Supp. 29 (1967)

is heavily relied upon by Johnson in his brief, but is clearly

distinguishable from the Johnson case because in Evenson:

1. Prior to filing suit on January 20, 1966, on Decem

ber 16, 1965, or prior thereto, a Commission rep

resentative had discussed the complaint (to the

13 fn. 4 from the above quotation from the Mickel case stated, “Representative

Celler, sponsor of the bill and Chairman of the Judiciary Committee which

reported upon it favorably, explained that the deletion was made to insure

‘that there will be a resort by the Commission to conciliatory efforts before

it resorts to a court for enforcement.’ 110 Cong. Rec. 2566 (1964).”

12

Commission) with a representative of the Com

pany for the purpose of urging the Company to

comply with the Act.

2. The Commission notified the complaining party

“that conciliation efforts had failed”.

3. In construing the provisions of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-

5 (a) as to the obligation of the Commission to

endeavor to eliminate such alleged unlawful em

ployment practice by informal methods of con

ference, conciliation, and persuasion, the Court,

noting that the Commission had endeavored to

employ such methods, said, “ ‘To endeavor’ means

to attempt or to undertake.”

Not only are all three of the foregoing fact conditions

impossible in the Johnson case, but in Johnson the Com

mission notified him it had been impossible “to undertake”

conciliation efforts due to the Commission’s heavy work

load. Moreover, the court’s definition of “to endeavor” in

the Evenson case is one of the exact points contended by

the Railroad in this case. Hence, the Railroad urges that

the Evenson case is consistent with the Dent case and the

Memorandum of Decision of Judge Jones in this case, as

applied to the facts in Johnson’s case.

Plaintiff Johnson also relies upon Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842 (1967) and Moody et al v.

Albemarle Paper Company, 271 F. Supp. 27 (1967), but

again there is a substantial and controlling difference

between the facts in the Johnson case where the Com

mission frankly told Johnson it had not undertaken con

ciliation because its workload was too heavy,14 and the facts

14 see Railroad’s Statement of Facts, supra, and full text of Commission’s

letter, PX, pp. la-3a.

13

of the Moody and Quarles cases where the Commission

notified the aggrieved party voluntary compliance had not

been effected or achieved. The most obvious distinguishing

feature between the Johnson case, and the Quarles and

Moody cases is the substance of the Commission’s notice

to the aggrieved party. In Quarles and Moody the Com

mission’s notice led the complaining party to believe con

ciliation endeavors had been initiated at least, but in the

Johnson case the Commission openly told Johnson it had

not undertaken conciliation, and he forthwith filed suit.

Moody, Quarles and Dent agree that sub-paragraphs (a )

and (e) of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 under the general heading

of “Enforcement provisions” must be construed together.

In addition to his attempt to assert that the Act as well

as its legislative history and the court decisions interpreting

the Act do not require “conciliation” as a jurisdictional

prerequisite to institution of a civil action, Johnson urges

two reasons for not requiring “conciliation” in his case,

(1) the administrative remedy is inherently inadequate or

ineffective, and (2) he has done all that the Act requires

of him before allowing him to institute suit. W ith respect

to the adequacy of the administrative remedy of concilia

tion, fit cannot be said that conciliation is inherently in-

' adequate or ineffective, since it has been tried. This same

argument was advanced in the Dent case, where the court

said . it has never been the function of the courts to dis

regard statutory requirements on the basis of which side

can present the most moving emotional argument and

pointed out that the complaining party was not being de

prived of his day in court, saying,

he will be entitled to proceed with a civil action

once the prerequisite of conciliation has been satisfied,

if, indeed, conciliation should not resolve the dispute.

Furthermore, Congress did not lose sight of the un

14

fairness which would result to parties against whom

charges are filed if they could be brought into court

without the conciliation step, and the courts certainly

should not lose sight of this fact.” 265 F.Supp. 56

at 62.

The adequacy of conciliation as an effective remedy to

Johnson’s claim will not be known until it is tried. W ith

respect to Johnson’s contention that he has done everything

he could to meet the requirements of the Act entitling him

to bring suit, the Railroad says that I'm addition to the

protection of the employee/applicant against the unlawful

employment practices defined in the Act, another sub

stantial purpose of the Act is the protection of the public

through the protection of both the employee and the em

ployer, which is accomplished first by means of “con

ciliation” designed to effect voluntary compliance, and

second by means of “coercion”, i.e. litigation. ; As stated

in the Hall case, the Act has a “split personality”, and the

interests of the public and the alleged discriminator must

also be protected by the courts. As recently stated by the

court in Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F. Supp.

781 (1967),

“* * * The statutory purpose of preventing discrim

ination in employment is tempered by an equally

cogent need to protect employers and other persons

subject to the Act’s mandate from subjection to the

burden of frivolous charges, claims and demands.

jjc

15 it should be noted that the court in the Choate case quotes with approval

from the Dent, Hall and Mickel cases, that conciliation is a jurisdictional

prerequisite to court action.

15

III

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Railroad urges that both “the letter

and the spirit” of the Act require exhaustion of the ad

ministrative remedies provided by the Act prior to suit

in the federal courts. Conciliation efforts are an essential

ingredient of these administrative remedies, and a juris

dictional prerequisite to suit in the federal courts. The

jurisdictional prerequisite of conciliation is lacking in each

of the multiple claims included in Johnson’s complaint in

the suit, the fact being that the only charge made to the

Commission was his dismissal from the Railroad’s employ.

Johnson’s dismissal was the sole charge investigated by

the Commission and included in its decision, and the Com

mission gave Johnson advance notice it had not undertaken

to eliminate the alleged unlawful employment practice, i.e.

Johnson’s dismissal, by informal methods of conference,

conciliation and persuasion, on the patently irresponsible

premise its workload was too heavy.

For the reasons herein set forth, as well as the Mem

orandum of Decision of the Trial Judge, the Order ap

pealed from should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

T hom as A sh e L ockhart

W. T hom as R ay

J o h n S. Cansler

Cansler & L ockhart

910 North Carolina National

Bank Building

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J o h n W. W eldon

500 W ater Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Appellee

A PPEN D IX

19

Letterhead of

SEABOARD A IR L IN E RAILROAD COMPANY

Office of Superintendent

Georgia Division

C. H. Lineberger

Superintendent

990 Chattahoochee Avenue, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30318

December 10, 1965 4f

T-1012

Certified Mail—Return Receipt Requested

Mr. Ray Johnson

Train Porter

503 Boyette Street

Monroe, N. C.

You are hereby dismissed, effective this date, from the

service of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company for

conduct unbecoming an employee and conduct bringing

discredit on the Seaboard Railroad, as developed in formal

investigation held on November 29, 1965 in Atlanta,

Georgia.

A transcript of the investigation referred to is attached.

Please turn in to Mr. E, C. Miller, Trainmaster at

Monroe, any Company property you have in your posses

sion, including annual passes Nos. ER 9400, 9401 and 9402

favor yourself, your wife and son Raymond H. Johnson.

s / C. H. L ineberger

C. H. L ineberger

Superintendent

20

503 Boyte Street

Monroe, North Carolina

January 1, 1966

To The Chairman

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Washington, D. C.

Dear S ir :

The writer of this letter is Ray Johnson, Train Porter

(with 25 years seniority) of the Seaboard Airline Rail

road Company until notified of my dismissal from the

services on December 10, 1965. This notification came two

days after I began a 26 day vacation period.

This dismissal, I feel is a punishment for my protests

against illegal practices of the railroad; i.e. I have been

classified in a way which has. for 25 years been a dep

rivation as well as adversely affecting my status as an

employee of the Railroad.

Although the reason given by the company is the result

of a conviction of a misdemeanor: The incident which led

to the conviction took place while I was off duty from

work and not on company property. I lost no time off from

w ork; nor was I negligent in my duties.

I feel that the dismissal is a denial of my constitutional

rights as guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the U.S. Constitution and Title V II of the Civil Rights

Law—the section on Prohibited Employer Practices.

I am respectfully asking for an investigation of the

causes for my dismissal and your aid in a fight for rein

statement.

Yours truly,

R ay J o hn son

21

Letterhead of

e q u a l e m p l o y m e n t o p p o r t u n i t y

COM M ISSION

Washington, D. C. 20506

In Reply Refer to:

5-12-3850

Seaboard Air Line

Railroad Company

Richmond, Virginia

Gentlemen:

This will inform you that, after investigation, the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission has determined that

there is reasonable cause to believe that you have engaged

in an unlawful employment practice within the meaning

of Section 703 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A copy

of the Commission Decision is enclosed.

A conciliator appointed by the Commission will contact

you soon to discuss means of correcting this discrimination

and avoiding it in the future.

Under Section 1601.24 of the Procedural Regulations of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Nothing

that is said or done during and as a part of the endeavors

of the Commission to eliminate unlawful employment prac

tices by informal methods of conference, conciliation, and

persuasion may be made a matter of public information

by the Commission without the written consent of the

parties, or used as evidence in a subsequent proceeding.”

22

' Since the charges in this case were filed in the early

phases of the administration of Title V II of the Civil Rights „

Act of 1964, the Commission has been unable to conduct

a conciliation during the sixty day period provided in Sec

tion 706. The Commission is, accordingly, obligated to ad

vise the charging party of his right to bring a civil action

pursuant to Section 706(e).

Nevertheless we believe it may serve the purposes of the

law and your interests to meet with our conciliator to see

if a just settlement can be agreed upon and a lawsuit

avoided.

We are hopeful that you will cooperate with us in

achieving the objectives of the Civil Rights Act and that

we will be able to resolve the matter quickly and satis

factorily to all concerned.

Very truly yours,

s / K e n n e t h F. H olbert

K e n n e t h F. H olbert

Acting Director of Compliance

A FF ID A V IT

RAY JOHNSON,

Plaintiff,

vs.

SEABOARD A IR L IN E RAILROAD COMPANY,

a corporation,

Defendant.

23

S. M. D U FFER, being first duly sworn, deposes and

says:

1. Fie is Director of Personnel of Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Company, successor to Seaboard Air Line Rail

road Company, with which predecessor Company he also

was Director of Personnel, and is fully authorized and

empowered to make this Affidavit on behalf of the de

fendant.

2. (a ) By letter dated August 8, 1966, the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission advised Seaboard Air

Line Railroad Company that the Commission had decided

there was “reasonable cause” to believe the defendant had

engaged in an unlawful employment practice within the

meaning of Section 703 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

with respect to the plaintiff, and in the second paragraph

of that letter, the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission advised the defendant,

“A conciliator appointed by the Commission will con

tact you soon to discuss means of correcting this

discrimination and avoiding it in the future.” (em

phasis added)

(b) Contrary to the advice contained in said letter, no

conciliator has contacted the defendant with respect to the

alleged unlawful employment practice, and there has been

no subsequent effort whatever at conciliation by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission.

A copy of said letter and the Commission Decision are

attached as Exhibits A and B hereto.1

1 Exhibits A and B appear in PX, pp. 1A and 3A.

24

3. In paragraph 3 of the plaintiff’s “Charge of Dis

crimination” to the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, he stated that the discrimination complained of

took place on July 6, 1965, and the Charge of Discrimination

was dated, subscribed and sworn to on January 12, 1966,

and marked received by the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission on January 14, 1966, all as appear from

the facsimile copy of the Charge of Discrimination hereto

attached as Exhibit C.

4. As a former employee of the defendant, the plaintiff

was a Passenger Train Porter, and the terms, conditions

and provisions of the plaintiff’s employment were deter

mined according to the agreement between the defendant

and the International Association of Railway Employees,

which appears as Exhibit A to the defendant’s Motion filed

herein on September 20, 1967, and such terms, conditions

and provisions of employment were not determined by

agreement direct between the plaintiff and the defendant.

Plaintiff made no appeal from the termination of his em

ployment as provided in said agreement. A total of forty-

one members of said association are employed by the de

fendant.

s / S. M. D u ffe r

S. M. D u ffer

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this 22nd day of September, 1967.

S. W. W orley

Notary Public

My commission expires: 7/17/70

(Affix Notary Seal here)

25

FILED

Oct. 9, 1967

Thos. E. Rhodes, Clerk

U. S. District Court

W estern Dist. of N. C.

RAY JOHNSON,

Plaintiff,

vs.

SEABOARD A IR L IN E RAILROAD COMPANY,

a corporation,

Defendant.

SU PPLEM EN TA L A FFID A V IT

OF C. E. M ERV IN E, JR. ON

D E F EN D A N T’S M OTION TO DISM ISS

C. E. M ERVINE, JR., being first duly sworn, deposes

and says:

1. He is Director of Labor Relations of Seaboard Coast

Line Railroad Company, and is fully authorized and em

powered to make this Supplemental Affidavit on behalf of

the defendant.

2. The defendant has more than 22,546 employees, and

negotiates with 20 bargaining agencies, a. list of which

appears as Exhibit A hereto, in arriving at the compensa

tion, terms, conditions, advantages, privileges, benefits

and provisions of employment for the employment of more

than 19,610 of said employees, the compensation, terms,

conditions, advantages, privileges, benefits and provisions

26

of employment for more than 2,936 employees being de

termined by direct arrangement or negotiation between

the defendant and each such employee.

s / C. E. M e r v in e , Jr.

C. E. M e r v in e , J r.

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this 5th day of October, 1967.

Carolyn R. F ra n c is

Notary Public

My Commission Expires:

Notary Public, State of Florida at Large

My Commission expires July 13, 1971

(Affix Notary Seal Here)

Exhibit A

1. Brotherhood of Locomotve Engineers.

2. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen.

3. Order of Railway Conductors and Brakemen.

4. Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen.

5. Brotherhood of Railway, Airline and Steamship

Clerks, Freight Handlers, Express and Station Em

ployees.

6. American Train Dispatchers Association.

7. Brotherhood of Maintenance of W ay Employees.

8. Brotherhood of Railroad Signalmen.

9. Transportation-Communication Employees Union.

27

10. Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

11. Hotel & Restaurant Employees & Bartenders Interna

tional Union.

12. American Railway Supervisors Association.

13. Brotherhood Railway Carmen of America.

14. International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

15. Sheet Metal W orkers’ International Association.

16. International Association of Machinists and Aero

space Workers.

17. International Association of Railway Employees.

18. International Brotherhood of Firemen & Oilers.

19. Railroad Yardmasters of North America, Inc.

20. The International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron

Ship Builders, Blacksmiths, Forgers and Helpers.