Lemon v. International Union of Operating Engineers Local 139 Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 25, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lemon v. International Union of Operating Engineers Local 139 Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees, 2000. 1fb24c11-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/689f571f-3fa5-43bb-b1db-c9ae6cc8f1d0/lemon-v-international-union-of-operating-engineers-local-139-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

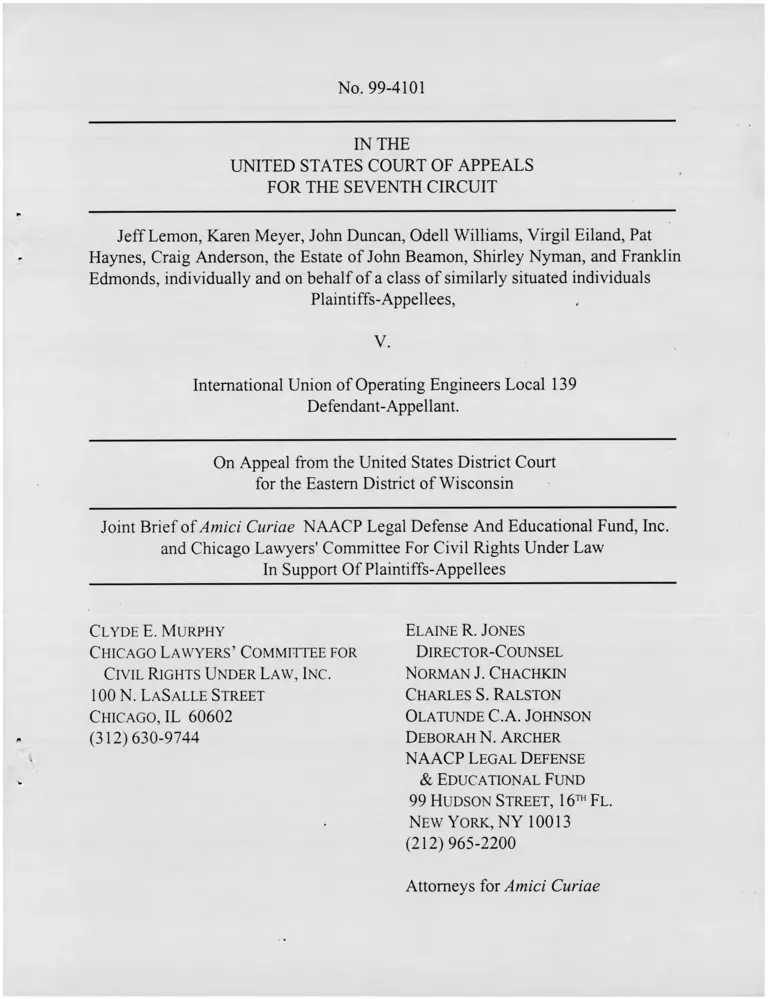

No. 99-4101

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Jeff Lemon, Karen Meyer, John Duncan, Odell Williams, Virgil Eiland, Pat

Haynes, Craig Anderson, the Estate of John Beamon, Shirley Nyman, and Franklin

Edmonds, individually and on behalf of a class of similarly situated individuals

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

International Union of Operating Engineers Local 139

Defendant-Appellant.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Wisconsin

Joint Brief of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense And Educational Fund, Inc.

and Chicago Lawyers' Committee For Civil Rights Under Law

In Support Of Plaintiffs-Appellees

C l y d e E. M u r p h y E l a in e R. J o n e s

C h ic a g o L a w y e r s ’ C o m m it t e e f o r D ir e c t o r -C o u n s e l

C iv il R ig h t s U n d e r L a w , In c . N o r m a n J. C h a c h k in

100 N. L a S a l l e S t r e e t C h a r l e s S . R a l s t o n

C h ic a g o , IL 60602 O l a t u n d e C.A. Jo h n s o n

(312)630-9744 D e b o r a h N. A r c h e r

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e

& E d u c a t io n a l F u n d

99 H u d s o n S t r e e t , 16th F l .

N e w Y o r k , NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Table of Contents

Table of Authorities...................................................................................... jj

Statement of Interest of Amici Curiae ................................................................ 1

Summary of Argument ............................................................... 3

Argument ........................................................................................................ 4

A.

B.

C.

Denying Class Certification in Actions Seeking Damages as well as Injunctive

Relief Would Undermine the Purposes of Title VII, and Frustrate Attempts

to Combat Employment Discrimination............................................................ 4

1 .

2 .

Congress Intended to Authorize Class Action Title VII Suits to Achieve the

Goals o f Eliminating Employment Discrimination and Providing Effective

Redress to Victims o f Discriminatory Practices as Efficiently as Possible,

Without the Necessity o f Individual Actions................................................... 4

Congress's Expansion o f Title VII to Allow Compensatory and Punitive

Damages Does Not Preclude Plaintiffs from Bringing Rule 23 Class

Actions.............................................................................. 5

3. Allison v. Citgo Should be Rejected by This Court............................ .......... 7

Injunctive Actions Seeking Compensatory and Punitive Damages May be

Certified Under Rule 23(b)(2)...........................................................................9

Bifurcation of Liability and Damages Claims Does Not Offend The 7th

Amendment........................................................................................ 12

CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... ..

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

Alaniz v. California Processors, 73 F.R.D. 269 (N.D. Cal. 1976) ................................................ 10

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).......................................................... 1, 4, 6, 8

Allison v. Citgo Petroleum, 151 F.3d 402 (5th Cir. 1998)...................................................... passim

Arnold v. United Artists Theatre Circuit, 158 F.R.D. 439 (N.D. Cal. 1994)................................ 12

Barefeld v. Chevron, 1988 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15816,48 Fair Emp. Prac. Case (BNA) 907 (N D Cal

1988) ...................................................................................................................................................... 7

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive, 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1 9 6 9 )...................................................... 4, 5, 8

Boyd v. Bechtel, 485 F. Supp. 610 (N.D. Cal. 1979 )..........................................................................7

Butler v. Home Depot, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3370 (N.D. Cal. 1996) ................................ 11-12

Coates v. Johnson & Johnson, 756 F.2d 524 (7th Cir. 1985) ........................ .......................... 13, 14

Cooper v. Federal Reser\’e Board, 467 U.S. 867 (1984)................................................................. 14

Crocket v. Green, 534 F.2d 715 (7th Cir. 1976) ................................................................................ 4

Edmondson v. Simon, 86 F.R.D. 375 (N.D. 111. 1980)................................................................... 7 9

Eubanks v. Billington, 110 F.3d 87 (D.C. Cir. 1997) ..................................................................... 10

Fontana v. Elrod, 826 F.2d 729 (7th Cir. 1987) .......................................................................... 9 12

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976)...................................................... 4 5

Gasoline Products Co., Inc. v. Champlin Refining Co., 283 U.S. 494 (1931) ............................ 12

Gulf Oil Co. v. Bernard, 452 U.S. 89 (1981).......................................................................... 4

Hoffman v. Honda o f America, 1999 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16553 (S.D. Ohio 1999) ...................... 11

Holmes v. Continental Can Co., 706 F.2d 1144 (11th Cir. 1983 ).................................................. 10

-ii-

. 13

13

13

12

12-

11

. 7

13

. 5

. 8

.4

.4

11

10

,5

13

11

-6

12

5

Houseman v. United States Aviation Underwriters, 171 F.3d 1117 (7th Cir. 1999)

In re Innotron Diagnostics, 800 F.2d 1077 (Fed. Cir. 1986).....................................

In re Paoli R.R. Yard, 113 F.3d 444 (3rd Cir. 1997)..................................................

In re Rhone-Poulenc Inc., 51 F.3d 1293 (7th Cir. 1995)

International Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)

Jefferson v. Ingersoll Intern. Inc., 195 F.3d 894 (7th Cir. 1999)..............................

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975)

King v. General Elec. Co., 960 F.2d 617 (7th Cir. 1992) .........................................

Kolstad v. American Dental 'n, 119 S. Ct. 2118 (1999)

Lowery’ v. Circuit City’ Stores, Inc., 158 F.3d 742 (4th Cir. 1998)............................

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co., 513 U.S. 352 (1995)

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968) ................. ..........

Orlowski v. Dominick’s Finer Foods, 172 F.R.D. 370 (N.D. 111. 1997)

Probe v. State Teachers ’ Retirement Systems, 780 F.2d 776 (9th Cir. 1986)

Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625 (4th Cir. 1978) .......................................

Stewart General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445 (7th Cir. 1976)................................

Warned v. Ford Motor Company, 189 F.R.D. 383 (N.D. 111. 1999)

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance, 508 F.2d 239 (3rd Cir. 1975)............................

Williams v. Burlington Northern, 832 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1987)

Wright v. Universal Maritime, 119 S. Ct. 391 (1998)

-in-

FEDERAL STATUTES

Civil Rights Act of 1991, P.L. 102-166......................................................................................passim

Pub. L No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 ............................................................................................... 5, 7

42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(n) (1 9 9 1 )...................................................................................................... 7

OTHER AUTHORITIES

H.R. Rep. No. 102-40(1), reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. (105 Stat................................................7

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 27 (1 9 7 2 )................................................................................ 5

Subcommittee on Labor, Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

OF 1972, 92d Cong......................................................................................................................... 6

RULES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2) .............................................................................................................. passim

Fed. R. C iv. P. 23(b)(2) advisory committee’s note, 39 F.R.D. 69, 102-03 (1966)................... 5, 9

Fed. R. C iv. P. 23(b)(3) ..................................................................................................................... 10

-iv-

Statement of Interest of Amici Curiae

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ("the Legal Defense Fund") is a non

profit corporation that was established for the purpose o f assisting African Americans in securing

their constitutional and civil rights. The Supreme Court has noted the Legal Defense Fund's

"reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that frequently

arise in civil rights litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963). The Legal Defense

Fund has taken a leading role in the development of the law of employment discrimination under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other statutes, acting as counsel in many of the leading

cases brought under these statutes. See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971);

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975); and McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co., 513 U.S. 352 (1995).

The Legal Defense Fund has a particular interest in the issue of certification of class actions

in employment discrimination cases, since it has for many years specialized in bringing class actions

in EEO cases and has been involved in many of the leading cases regarding class certification and

the rights o f class members. See. e.g., Coopery. Federal Reserve Board, 467 U.S. 867(1984); Gulf

Od Co. v. Bernard, 452 U.S. 89 (1981); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra; Bazcmore v. Friday, 848 F.2d 476 (4th Cir. 1988).

The Chicago Lawyers' Committee was founded in 1969 as a cooperative effort of Chicago's

major law firms to ameliorate poverty and discrimination by providing legal assistance to the poor,

and to members of minority and other disadv antaged groups seeking equal access to employment,

public accommodations, housing and quality education. The Chicago Lawyers' Committee focuses

its efforts on civil rights cases and projects that will benefit the community at large. Since its

inception, the Chicago Lawyers' Committee has enlisted the pro bono services of many hundreds of

attorneys from Chicago law firms in addressing a wide range of legal problems, including

employment discrimination.

2

Summary of Argument

Appellant s argument against class certification of Title VII actions that request injunctive

relief as well as compensatory and/or punitive damages is wholly inconsistent with the explicit

purposes of Title VII and of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, P.L. 102-166. Congress has long endorsed

the use of class actions as a mechanism for redressing systemic employment discrimination and has

forcefully rejected attempts to limit the availability of the class action mechanism. The 1991 Act,

in allowing plaintiffs to recover both compensatory and punitive damages, sought to expand the

arsenal o f remedies available to plaintiffs, and contains no hint that the use of class actions should

in any way be curtailed. Not only would the interpretation urged by Appellants do violence to the

purposes of Title VII and the 1991 Act, but it contravenes the plain language of Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 23. Specifically, nothing in 23(b)(2) forbids class certification for injunctive relief actions

that also seek compensatory and punitive damages, and, to the extent that the Fifth Circuit’s decision

in Allison v. Citgo Petroleum, 151 F.3d 402 (5,h Cir. 1998), adopts a blanket rule to the contrary, that

decision should be rejected by this Court. Finally, damages actions certified under Rule 23(b)(2)

can be managed by employing the bifurcated framework of International Bhd. o f Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), commonly used in employment discrimination cases. Because

such a framework does not require the jury deciding damages to revisit any issues decided by the

first jury in determining liability, it does not offend the Seventh Amendment.

3

Argument

A. Denying Class Certification in Actions Seeking Damages as well as Injunctive Relief

Would Undermine the Purposes of Title VII, and Frustrate Attempts to Combat

Employment Discrimination.

Appellant’s argument that cases brought pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, in

which compensatory and/or punitive damages are requested, are unsuitable for class certification

pursuant to Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 23 is inconsistent with both the underlying purposes of

Title VII and the legislative history of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 in particular.

1. Congress Intended to Authorize Class Action Title VII Suits to Achieve the Goals o f

Eliminating Employment Discrimination and Providing Effective Redress to Victims

o f Discriminatory Practices as Efficiently as Possible, Without the Necessity o f

Individual Actions.

Congress designed Title VII to serve the dual purpose of ending systemic employment

discrimination and providing full relief for all the victims of prohibited discrimination. See

McKennon v. Nashville Banner, 513 U.S. 352, 358 (1995); Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975). Decisions of the Supreme Court and of the Courts of Appeals, including

this Court, have recognized the importance of class actions as the most effective means for achieving

this dual purpose. See, e.g., Gulf Oil v. Bernard, 452 U.S. 89, 99 n.l 1 (1981); Franks v. Bowman

Transportation, 424 U.S. 747, 771 (1976); Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625, 634 (4th Cir.

1978), cert, denied, 440 U.S. 981 (1979); Crocket v. Green, 534 F.2d 715, 718 (7th Cir. 1976);

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance, 508 F.2d 239, 250 (3rd Cir. 1975); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive,

416 F.2d 711,719 (7th Cir. 1969); Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir.

1968). The consistent theme of these decisions is that relief to all members of a class of persons who

4

have been the victims of employment discrimination is essential both to the vindication of the

important public policies underlying Title VII and to carrying out the goal of making such victims

whole and placing them, to the extent possible, in the same position they would have been in the

absence of discrimination. See Franks, 424 U.S. at 763-64; Sledge, 585 F.2d at 643-44. In recent

years, the Supreme Court has been hostile to attempts by lower courts to cut back the available

remedies, and thus the effectiveness, of Title VII. See, e.g., Kolstadv. American Dental Ass ’n, 119

S. Ct. 2118, 2124 (1999); Wright v. Universal Maritime,119 S. Ct. 391, 396 (19,98).

Class actions have been the primary means of achieving the dual purposes of Title VII. In

that regard, this Court has emphasized that "[a] suit for violation o f Title VII is necessarily a class

action as the evil sought to be ended is discrimination on the basis of a class characteristic." Bowe,

416 F.2d at 719; see also Wetzel, 508 F.2d at 250. Indeed, the specific purpose of section 23(b)(2),

first adopted when Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure was amended in 1966, was to

facilitate the bringing of class actions in civil rights cases. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2) advisory

committee’s note, 39 F.R.D. 69, 102-03 (1966). Thus, the Advisory Committee's note cites a series

of civil rights decisions as examples of cases intended to be certified under Rule 23(b)(2). Id. at 102.

The 1972 Amendments to Title VII specifically endorsed the use o f class actions in Title VII

cases and rejected proposed efforts to curtail Title VII class actions. See S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong.,

Is1 Sess., 27 (1972). The Senate Report stated:

This section [706] is not intended in any way to restrict the filing o f class complaints.

The committee agrees with the courts that title VII actions are by their very nature

class complaints], and that any restriction on such actions would greatly undermine

the effectiveness of title VII.

5

Id. at 27. Congress further emphasized that:

[t]he courts have been particularly cognizant of the fact that claims under Title VII involve

the vindication of a major public interest, and that any action under the Act involves

considerations beyond those raised by the individual claimant. As a consequence, the

leading cases in this area to date have recognized that many Title VII claims are necessarily

class action complaints and that, accordingly, it is not necessary that each individual entitled

to relief be named in the original charge or in the claim for relief.

Subcommittee on Labor, Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

OF 1972, 92d Cong., at 1773; see also Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 414 n.8 (noting Congress’s explicit

rejection of limitations on class actions in Title VII cases).

2. Congress's Expansion o f Title VII to Allow Compensatory and Punitive Damages

Does Not Preclude Plaintiffs from Bringing Rule 23 Class Actions.

Appellant’s argument for a blanket prohibition against class actions in Title VII damages

cases also lacks any support in the legislative history of the Civil Rights Act of 1991. There is no

evidence that Congress, in amending Title VII to allow recovery of compensatory and punitive

damages, sought in any way to curtail use of class actions by plaintiffs. To the contrary, Congress’s

clear purpose in passing the 1991 Act was to expand available remedies so that plaintiffs could better

vindicate their rights. See Pub. L No. 102-166, §3, 105 Stat. 1071 (Act’s purpose is “(1) to provide

appropriate remedies for intentional discrimination and unlawful harassment in the workplace.”).

In that regard. Congress not only sought to add compensatory and punitive damages to the arsenal

of a\ailable remedies so that plaintiffs could better “deter unlawful harassment and intentional

discrimination in the workplace,” id. §2, but it also reversed several Supreme Court decisions that

sought to limit the scope of Title VII, § 3. In fact, the only change made by Congress that had any

direct effect on class actions enured to the benefit of civil rights plaintiffs, by limiting collateral

6

attacks on judicial decrees rendered in employment discrimination class actions, see id. §108

(codified at 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(n) (1991)).

Moreover, Congress’s clear intent in passing the 1991 Act was to provide victims of

employment discrimination the same right to compensatory and punitive damages under Title VII

that had long been provided to plaintiffs under section 1981 pursuant to Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 421 U.S. 454, 460 (1975). See H.R. Rep. No . 102-40(1), reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N.

(105 Stat.) 603. Given that under section 1981, plaintiff classes sought compensatory or punitive

damage awards — see, e.g., Barefield v. Chevron, 1988 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15816, at *13, 48 Fair

Emp. Prac. Case (BNA) 907,910-11 (N.D. Cal. 1988); Boyd v. Bechtel, 485 F. Supp. 610,613 (N.D.

Cal. 1979); Edmondson v. Simon, 86 F.R.D. 375, 383 (N.D. 111. 1980) — and that Congress sought

to expand Title VII to allow the same recovery permissible under section 1981, it is inconceivable

that Congress could have perceived such damage awards to be inconsistent with Rule 23. Certainly,

nothing in the legislative history of 1991 Act suggests this.

3. Allison v. Citgo Should be Rejected by This Court.

Appellant urges this Court to follow the Fifth Circuit’s recent decision in Allison v. Citgo

Petroleum, 151 F.3d 402 (5lh Cir. 1998), and adopt a blanket rule prohibiting plaintiffs in Title VII

cases from seeking both injunctive relief and compensatory damages in a class action. This Court’s

adoption of such a ruling would have a deleterious effect on the ability of Title VII plaintiffs to

eradicate employment discrimination by erecting unnecessary barriers to class actions that will have

a deep and far reaching impact. By imposing this restriction on the scope of class action litigation,

the ruling in Allison places class-action plaintiffs in the untenable position of choosing either to

forfeit their right to seek compensatory' damages in order to challenge systemic discrimination, or

7

to pursue "make whole" relief in the form of compensatory damages for themselves while leaving

institutionalized discrimination intact. This not only bars plaintiffs from exercising their rights to

the full extent permitted by law but also undermines Congress’s intent that Title VII provide

effective and complete remedies to victims of employment discrimination.

As discussed above, because "[t]he clear purpose of Title VII is to bring an end to the

proscribed discriminatory practices and to make whole, in a pecuniary fashion, those who have

suffered by it, [permitting] only injunctive relief in the class action would frustrate the

implementation of the strong Congressional purpose expressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

Bowe, 416 F.2d at 720. Allowing plaintiffs to seek injunctive relief and compensatory damages has

an obvious connection with this purpose: "If employers faced only the prospect of an injunctive

order, they would have little incentive to shun practices of dubious legality." Albermarle, 422 U.S.

at 417.

The effect of the inability of victims of discrimination to pursue both compensatory and

injunctive relief through class actions is exacerbated by the potential inability o f such victims to

receive complete relief through individual EEO suits. In Lowery• v. Circuit City/ Stores, Inc., 158

F.3d 742 (4th Cir. 1998), vacated on other grounds, 119 S. Ct. 2388 (1999), the Fourth Circuit held

that individual plaintiffs "do not have a private, non-class cause of action for pattern or practice

discrimination" under Title VII. Id. at 759. Thus, if read in conjunction with Lowery, the rule in

Allison would prevent Title VII plaintiffs, in any forum, from seeking both compensatory and broad

injunctive relief and would severely retard Title VII’s ability to end systemic employment

discrimination and secure full relief for all the victims of discrimination.

8

B. Injunctive Actions Seeking Compensatory and Punitive Damages May be Certified

Under Rule 23(b)(2).

Any suggestion that actions for injunctive relief and damages, as a matter o f law, cannot be

certified pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) must also be rejected. Class actions in employment

discrimination cases have historically been certified under Rule 23(b)(2), because these actions seek

primarily injunctive and declaratory relief. But even where compensatory and punitive damages are

sought in addition to equitable relief, Rule 23(b)(2) remains an appropriate vehicle.

By its terms, Rule 23(b)(2) requires only that “final relief of an injunctive nature or a

corresponding declaratory nature, settling the legality of behavior with respect to the class as a

whole, [be] appropriate.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2). The accompanying guidance in the Advisory

Committee notes specify that “[t]he subdivision does not extend to cases in which the appropriate

final relief relates exclusively or predominantly to money damages.” Fed. R. Civ . P. 23(b)(2)

advisory committee’s note, 39 F.R.D. at 102. Thus courts allow certification under this subsection

where declaratory and injunctive relief is the predominant relief requested. See, e.g., Warnell v.

Ford Motor Company, 189 F.R.D. 383, 388-89 (N.D. 111. 1999); Edmondson v. Simon, 86 F.R.D.

375, 383 (N.D. 111. 1980). However, nothing in the language of the Rule - or the Advisory

Committee notes - can be read to imply that when damages are sought in addition to declaratory or

injunctive relief Rule 23(b)(2) certification is inappropriate. See Fontana v. Elrod, 826 F.2d 729,

732 (7!h Cir. 1987) (approving class certification procedures in 23(b)(2) action requesting punitive

damages); Edmondson, 86 F.R.D. at 383 (certifying class requesting compensatory and punitive

damages under section 1981). As the Ninth Circuit held in the context of a request for legal damages

in a case brought under both the Equal Pay Act and Title VII, “Rule 23(b)(2) is not limited to actions

9

requesting only injunctive or declaratory relief, but may include cases that also seek monetary

damages” Probe v. State Teachers ’ Retirement Systems, 780 F.2d 776, 780 (9th Cir.) (emphasis

added), cert, denied, 476 U.S. 1170 (1986); see also Holmes v. Continental Can Co., 706 F.2d 1144,

1152 (11th Cir. 1983). In fact, courts in employment discrimination cases have long permitted

certification under this rule even where substantial — and often complicated — monetary relief

remains a significant part of the remedy. See, e.g., Eubanks v. Billington, 110 F.3d 87, 95- 97 (D.C.

Cir. 1997); Alaniz v. California Processors, 73 F.R.D. 269, 281-86 (N.D. CaL 1976); see also

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445, 451-54 (7th Cir. 1976) (discussing mechanics of

awarding classwide backpay).

Appellant’s argument that injunctive actions that include requests for compensatory and

punitive damages will always be inappropriate for Rule 23(b)(2) certification— and indeed for

certification under 23(b)(3)— should be rejected. For this argument, Appellant again places great

reliance on the Fifth Circuit’s singular decision in Allison v. Citgo Petroleum. As an initial matter,

the contours of the Allison decision itself are not clear. While Appellant interprets the Fifth Circuit

to announce a blanket rule that actions for compensatory and punitive damages are not proper

23(b)(2) actions, the Allison Court simply expounds, in much of its opinion, on the unremarkable

proposition that 23(b)(2) certification is inappropriate where requests for money damages are the

predominant relief sought. See, e.g., 151 F.3d at 414-17. The Allison Court, consistent with the

ruling of other courts, leaves the determination of whether a “given monetary remedy qualifies as

incidental damages to the discretion of the trial court. See id. at 416 (“We recognize that, as a

matter of degree, whether a given monetary remedy qualifies as incidental damages will not always

be a precise determination . . . . The district courts, in the exercise o f their discretion, are in the best

10

position to assess whether a monetary remedy is sufficiently incidental to a claim for injunctive or

declaratory relief to be appropriate in a (b)(2) class action.”).

The Allison court’s subsequent determination that (b)(2) and (b)(3) certification were

inappropriate stemmed in substantial part from the difficulty of determining damages in the case

before it — one which called for the certification of a class o f a “thousand potential plaintiffs spread

across two separate facilities, represented by six different departments, challenging various policies

and practices over a period of nearly twenty years.” Id. at 417; see also id. at 419-20. Moreover,

the Fifth Circuit on rehearing maintained that the panel majority’s decision was not even about rule

23. According to the Court, “[t]he trial court utilized consolidation under rule 42 rather than class

certification under rule 2j> to manage this case. We review that decision for abuse of discretion and

we find no abuse in this case.” Id. at 434. Thus, the Allison court’s pronouncements on Rule 23

appear to be dicta with no precedential value in the Fifth Circuit, much less in other Circuits.

This Court’s recent query in Jefferson v. Ingersoll Intern. Inc., 195 F.3d 894, 897-98 {7th Cir.

1999) as to whether 23(b)(2) certification is ever appropriate for actions that request both injunctive

relief and damages should thus be answered in the affirmative. As explained above, a blanket rule

that any request for compensator)' and punitive damages — or at least one that might necessitate

bifurcation — is inconsistent with Rule 23(b)(2), is not supported by either the language of Title VII

or the language of Rule 23 . And, contrary to Appellant’s assertions, most courts that have addressed

the issue have declined to adopt such a rule. See. e.g.. Hoffman v. Honda o f America, 1999 U.S.

Dist. LEXIS 16553, at *2-25 (S.D. Ohio 1999); Warnell v. Ford Motor Co., 189 F.R.D. 383, 389

(N.D. 111. 1999); Orlowskiv. Dominick's Finer Foods, 172 F.R.D. 370, 374 (N.D. 111. 1997); Butler

11

V. Home Depot, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3370, at *13-15 (N.D. Cal. 1996); Arnold v. United Artists

Theatre Circuit, 158 F.R.D. 439, 464 (N.D. Cal. 1994).

Finally, it is worth noting that if a class is certified under Rule 23(b)(2), a court has power

under Rule 23(d) to require the provision of notice to class members to inform them of their

individual monetary claims. See Williams v. Burlington Northern, 832 F.2d 100, 103-04 (7th Cir.

1987); Elrod, 826 F.2d at 732. In any event, the provision o f notice is not at issue in this case:

Plaintiff-Appellees have agreed to provide notice and opt-out rights to class mpmbers. Brief of

Appellees, at 21.

C. Bifurcation of Liability and Damages Claims Does Not Offend The 7th Amendment.

Plaintiff-Appellees’ suggestion that the liability phase of this case be tried to a jury and that,

if necessary, a second jury try the damages claims, does not offend the Constitution. Bifurcation

of liability and damages phases of trial, approved in International Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 361 (1977), has long been the procedure for adjudicating classwide and

individual relief claims in employment discrimination contexts. Under Teamsters, at the liability

stage, the plaintiff class has the burden of showing that the employer has engaged in a regular

practice of discrimination, after which classwide injunctive relief may be ordered. Id. at 361. To

get individual relief, the trial court “must usually conduct additional proceedings after the liability

phase,” at which point the burden then rests on the defendant to show that “the individual applicant

was denied an employment opportunity for lawful reasons.” Id. at 361-62. To the extent that the

classwide liability claims and the class members' damages claims may depend on common issues

of fact, the court must simply instruct the jury in the second stage not to revisit the issues decided

in the first phase. See Gasoline Products Co.. Inc. v. Champlin Refining Co., 283 U.S. 494, 497-99

12

(1931 );see also In re Rhone-PoulencInc., 51 F.3d 1293,1303 (7th Cir. 1995). Courts have routinely

applied this procedure in employment discrimination class actions. See, e.g., King v. General Elec.

Co., 960 F.2d 617, 621-24 (7th Cir. 1992)\ Coates v. Johnson & Johnson, 756 F.2d 524, 533 (7th Cir.

1985); Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445, 451 (7th Cir. 1976) (employing Teamsters

framework), cert, denied, 433 U.S. 919 (1977).

This practice does not offend a defendant’s Seventh Amendment right to a fair trial, which

only forbids separatejuries from examining the same issue. See Houseman v. United States Aviation

Underwriters, 171 F.3d 1117, 1126 (7th Cir. 1999); see also Champlin, 284 U.S. at 499. In a Title

VII action for compensatory damages, the issue of whether the employee has been “actually injured”

by an unlawful discriminatory policy does not, given proper instructions by the judge, require ajury

to revisit the question of whether the defendant in fact has a discriminatory policy. See Butler v.

Home Depot, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3370. at *16 (N.D. Cal. 1996) (bifurcation of class liability and

individual damage claims does not offend Seventh Amendment); see also Allison, 151 F.3d at 433

(Dennis, J., dissenting) (where the court clearly instructs the second jury not to revisit issues decided

by the jury in the first phase, the Seventh Amendment is not violated). That separatejuries may

consider “overlapping evidence” does not offend the Constitution, see Houseman, 171 F.3d at 1126,

nor does the fact that some of the same evidence must be presented, as long as the two juries don’t

decide the same essential issues. See In re Paoli R.R. Yard, 113 F.3d 444, 452-53 n.5 (3rd Cir.

1997); In re Innotron Diagnostics, 800 F.2d 1077, 1086 (Fed. Cir. 1986).

In the final analysis, the Seventh Amendment concern raised by Appellant is essentially a

red herring: it is difficult to see how an adjudication of the individual claims for damages in a

proceeding by a second jury could unfairly benefit any party but the employer. If the jury fails to

13

find classwide liability, the individual claimants are bound by the ruling that the employer did not

engage in a pattern and practice of discrimination in any subsequent litigation, see Cooper v. Federal

Reserve Bank o f Richmond, 467 U.S. 867 (1984); Coates, 756 F.2d at 553. Conversely, if the jury

does find classwide liability, a jury that were to unconstitutionally reexamine the determination of

a discriminatory employment pattern decided in the first phase of trial would be likely to conclude

that none of the individual plaintiffs were actually injured, in which case the employer, again, would

benefit.

*

CONCLUSION

Amici respectfully urge this Court to reject a rule prohibiting Rule (23)(b)(2) class

certification in Title VII actions in which compensatory and punitive damages are requested, and to

affirm the District Court’s grant of class certification in this case.

14

January 25, 2000

Respectfully submitted,

Clyde E. Murphy

Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law , Inc.

100 N. LaSalle Street

Chicago, IL 60602

(312) 630-9744

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Olatunde C.A. Johnson

DeborahN. Archer

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212)965-2200

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

15

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the accompanying Motion fo r Leave to File B rief as Amicus

Curiae and Brief o f Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund and Chicago

Lawyer s Commiteefor Civil Rights In Support o f Plaintiff-Appellees have been served by depositing

same in the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, on January 25, 2000 to the following:

Marianne Goldstein Robbins

John J. Brennan

Previant, Goldberg, Uelmen, Gratz

Miller, & Brueggeman, s.c.

1555 N. RiverCenter Drive, Suite 202

P.O. Box 12993

Milwaukee, WI 53212

Charles Barnhill, Jr.,

Miner, Barnhill & Galland, P.C

64 East Mifflin St., Suite 803

Madison, WI 53703

Judson Miner

Miner, Barnhill & Galland, P.C.

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, IL 60610

OLATUNDE C.A. JOHNSON