Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Jenkins et al. in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 28, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Jenkins et al. in Opposition to Certiorari, 1991. c6ffddf3-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/68b61985-291d-4987-9708-4813f75c2c4a/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-of-respondents-jenkins-et-al-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

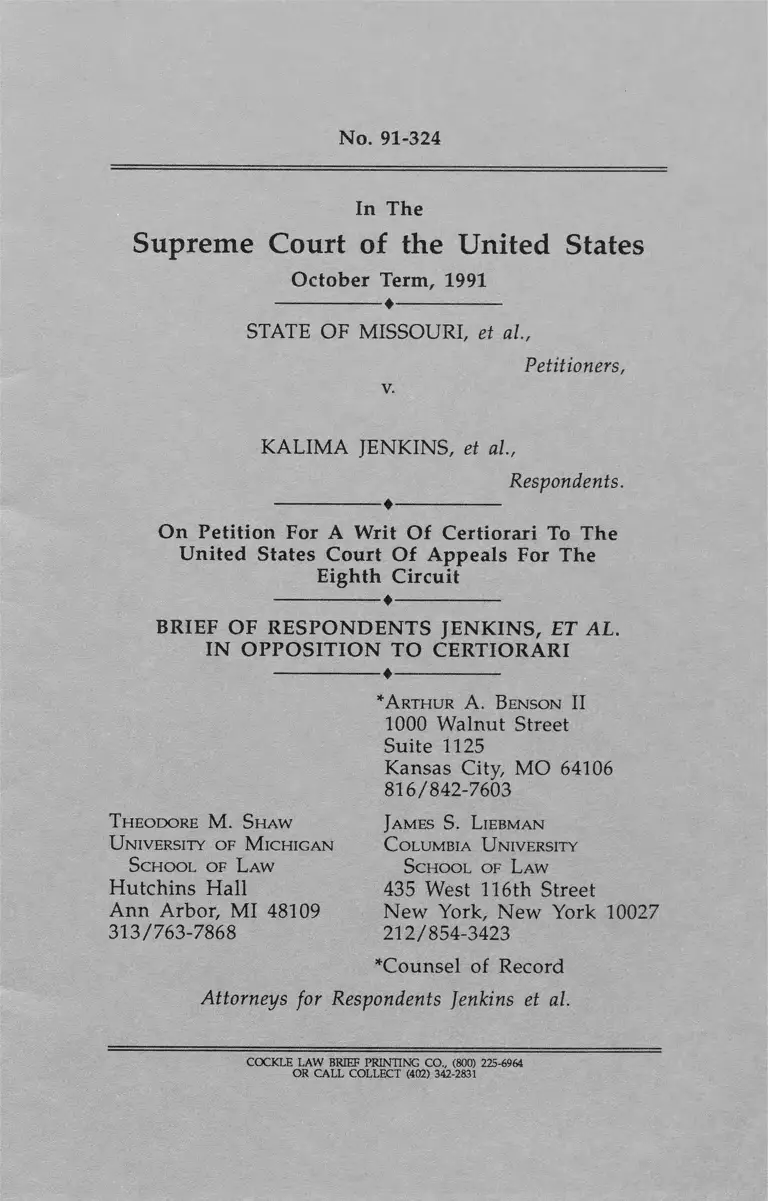

No. 91-324

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

-----------------♦-----------------

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Respondents.

-----------------♦-----------------

On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals For The

Eighth Circuit

-----------------♦-----------------

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS JENKINS, ET AL.

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

- ♦ -----------------------------

"■Arth u r A. B en so n II

1000 Walnut Street

Suite 1125

Kansas City, MO 64106

816/842-7603

J a m es S. L iebm a n

C o lu m bia U n iv ersity

S c h o o l o f L aw

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

212/854-3423

"Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Respondents Jenkins et al.

T h eo d o re M. S haw

U n iv er sity o f M ich ig a n

S c h o o l o f L aw

Hutchins Hall

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

313/763-7868

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

COUN TER-STATEM EN T OF

Q U ESTIO N S PRESEN TED

1. W hether, having found that capital im prove

ments were critical to the success of a school desegrega

tion plan, the courts below erred in requiring the culpable

parties to carry out those improvements in compliance

with applicable provisions of the Asbestos Hazard and

Emergency Response Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 2641-2654 (1988).

2. Whether, having found that construction of a new

high school was critical to the success of the school

desegregation plan, the courts below erred in approving

adjustments to the budget for the school.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions P resen ted ................................................................. i

Table of A u th orities ................................................................. iii

Counter-Statement of the C ase ........................................... 1

Reasons for Denying the W r it .......................................... 19

C onclu sion ................................................................ 30

ii

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C a ses

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir.

1977)................................................................................................. 3

Board o f Educ. v. St. Louis, 149 S.W.2d 878 (Mo.

1941).................................................................................................4

Brown v. Board o f Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

.........................................................................................6, 7, 10, 26

Columbus Board o f Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ..............................................................................21, 23, 25

Dayton Board o f Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 528

(1 9 7 9 )............... ................................................... 21

.............................................................................................21, 23, 28

Jenkins v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984) .passim

Jenkins v. Missouri, 639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo. 1985) .passim

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

Jenkins v. M issouri, 672 F. Supp. 400 (W.D. Mo.

1987>................................................................... 3, 10, 15, 16, 22

Jenkins v. M issouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) (en

banc), cert, denied, 484 U.S. 816 (1987)................... 11, 29

Jenkins v. M issouri, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988),

aff'd, 110 S.Ct. 1651 (1990)......................................... passim

Jenkins v. M issouri, 904 F.2d 415 (8th Cir. 1990)........... 13

Jenkins v. M issouri, 942 F.2d 487 (8th Cir. 1991)...........28

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1 9 7 3 )___ 21

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) . . .12, 20, 21, 22, 28

M illiken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1 9 7 7 ) ........................2, 27

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1 9 4 8 ).....................................9

State o f M issouri v. Kalima Jenkins, 491 U.S. 274

(1 9 8 9 ) ............... 2

State of M issouri v. Kalima Jenkins, 110 S.Ct. 1651

(1990) .................................................................................. 2, 15

Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ) ......................................................................... 5, 21

Watson v. M emphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963)............................ 21

S tatutes

Asbestos Hazard and Emergency Response Act,

15 U.S.C. §§ 2641-2654 (1988)........................................... 18

1889 Mo. Laws 226, expanded in 1909 Mo. Laws

770, 790, 820 ................... 3

No. 91-324

-------4-------

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1991

-----------------❖ -----------------

STATE OF MISSOURI, et ah,

Petitioners,

v.

KALIMA JENKINS, et ah,

Respondents.

-----------------♦-----------------

On Petition For A Writ O f Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals For The

Eighth Circuit

-----------------♦-----------------

BR IEF OF RESPO N D EN TS JEN K IN S, ET AL.

IN O PPO SITIO N TO C ERTIO RA RI

-----------------♦-----------------

COUN TER-STATEM EN T OF THE CASE

A. Introduction

Petitioners, officials of the State of Missouri, invite

this Court, on the narrow est of questions, to review

broadly a school desegregation remedy alleged to be

excessive. Understandably, petitioners fail to reveal the

expansive nature and scope of their violations, which

required both the narrow aspects of the remedy that are

actually before the Court and the remedy as a whole.

Because this Court has never reviewed the violations,1

1 Nor has the Court reviewed the remedy in this case.

Previously, this Court has declined to review the school

1

2

and because "the nature of the desegregation remedy is

to be determ ined by the nature and scope of the constitu

tional v io la tio n s]," M illiken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 280

(1977), respondent schoolchildren briefly recount the

lower courts' violation findings and the extensive record

evidence supporting them .2

B. Overview of the D istrict Court's Findings

Prior to 1954 M issouri mandated racially segregated

schools. The district court found that every "school dis

trict in M issouri participated in this dual system ," and

that intentionally segregated "access" to schools and par

ticularly school districts had the effect of concentrating

blacks within the Kansas City, Missouri School District

("KCM SD "). 593 F.Supp. at 1490. The court further found

that M issouri's continuing segregation of schools in the

decade after 1954 "led to white flight from the KCMSD to

suburban districts [of a] large number of students . . . and

that it has caused a wide reduction in student achieve

ment in the schools of KCMSD." Order, August 25, 1986,

at 1-2. As a further result of M issouri's continuing seg

regation of blacks in KCM SD's inferior schools, and of

the consequent refusal of white voters to support the

district financially, the KCM SD's "physical facilities have

literally rotted ," and the "overall cond ition" of the

children's petition seeking a broader, interdistrict remedy,

]enkins v. Missouri, 484 U.S. 816 (1987), and the State's petition

seeking a narrower remedy, 490 U.S. 1034 (1989). This Court has

reviewed issues of attorneys fees 491 U.S. 274 (1989) and fund

ing of remedies, 110 S.Ct. 1651 (1990).

2 In the course of its deliberations on violations and rem

edy, the district court heard evidence from more than 250 wit

nesses over 130 days, amassed a transcript exceeding 40,000

pages and received more than 50,000 pages of documentary

evidence.

3

schools became so "generally depressing . . . fas to]

adversely affectf] the learning environm ent." 672 F.Supp.

at 411, 403.

These findings and the voluminous record evidence

supporting them are discussed in more detail below.

C. Pre-1954 V iolations

From 1865 through 1976 M issou ri's constitu tion

required "sep arate" schools for "children of A frican

descent/'3 and, from 1889 to 1954, the State enforced that

provision with statutes making it a criminal offense for

"any colored child to attend a white sch o o l."4

M issouri superimposed its dual schools on a vast and

intensely fragmented system of individual school dis

tricts. Unlike other southern states that mandated seg

regation, M issouri did not have a small number of large,

county-wide school districts. Instead, like most northern

states, M issouri distributed its schoolchildren among a

large number of small school districts - over 10,000 dis

tricts in 1900, and 8000 as late as 1948 (compared to 546

today). P.Ex. 212.

Because M issouri's black population before 1954 was

widely dispersed among its many small school districts,5

3 Mo. Const. 1865, art. 9, § 2.

4 1889 Mo. Laws 226, expanded in 1909 Mo. Laws 770, 790,

820 to include even private schools. The history of Missouri's de

jure school segregation appears in detail in the decision in

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir. 1977) to which the

district court referred in making its violation findings, 593

F.Supp. at 1485.

5 Before 1954, more than half the State's school-aged black

children lived in 93 counties in each of which fewer than 1,000

black children were widely and thinly dispersed among the

county's 60 to 100 school districts. P.Exs. 208, 210, 184, 184A.

4

the state's racial segregation requirements had a partic

ularly strong residential effect on the state's black school-

children. In particular, most of M issouri's school districts

reserved th eir sin g le sch oolh ou ses for w hites and

required black children to seek an education outside the

district.6 Because M issouri did not require school districts

to educate blacks locally or to reimburse them for tuition

and transportation expenses incurred in getting an educa

tion elsewhere,7 black families with children typically

had no choice but to move to the few urban districts in

the state that provided black, as well as white, schools.8

6 In 1866, the state school superintendent reported that

blacks "are so widely scattered that it is impossible to collect

them in sufficient number to warrant the expense of a school."

P.Ex. 208. In 1914, the superintendent reported that lack of

schools for blacks was "driving these people to towns in order

to educate their children." P.Ex. K28. In 1922, the superinten

dent reported "where there are fewer than fifteen [black] chil

dren in a district . . . the school board is not interested in

assisting these negro children to get an education." P.Ex. K30.

7 Board of Educ. v. St. Louis, 149 S.W.2d 878 (Mo. 1941)

(school districts not required to pay for inter-county transfers).

8 Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1490. For example, in the three

counties around the KCMSD, 55 school districts enumerated

blacks but failed to provide any reimbursement for tuition and

transportation before 1931, when one district started paying.

Only one other district was making payments as of 1945, and

even in 1953 only five districts made such reimbursements.

During much of that time, the KCMSD tuition amounted to one-

fourth of the income of an average black family. Tr. 4313-4,

5355-8. As a result, black families initially tried to collect sub

scriptions to operate private schools. That failing, black parents

next tried to convey their children to KCMSD, at their own

expense, by horse and buggy, taxis, public buses, hired hearses,

and on trains or on foot along routes plied by school buses

reserved for white children only. Eventually, many families

boarded their children with relatives and strangers in the

5

Citing this and other evidence, the district court

found "an inextricable connection between schools and

h o u sin g in the K an sas C ity a re a ." B ecau se b lack

" 'tp leople gravitate[d] toward school facilities/ " the

" 'location of [black] schools in flu enced] the patterns of

residential development of [the] metropolitan area and

ha[d] im portant im pact on com position of inner city

neighborhoods/ " 593 F.Supp. at 1491 and Order of June

5, 1984 at 101, quoting Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg Bd.

o f Educ.., 402 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1971). Between 1900 and 1954

the num ber and ratio of black fam ilies with school-

children in the school districts surrounding the KCMSD

declined precipitously. P.Ex. 53E. Although 21% of black

students in the 3-county area lived outside the KCMSD in

1900, that proportion had fallen to 3% by 1954. Id. The

district court found that access to schools was a "m ajor

factor" in causing blacks to move into the KCMSD.9

"Undeniably," the district court found, "blacks m oved"

out of districts that did not "m aintain the state-required

KCMSD; broke their families into two households, mother and

children in the KCMSD, father working back home; and in the

end, gave up their jobs and homes and moved entire families to

the KCMSD.

9 593 F.Supp. at 1490, citing Tr. 16693 (expert testimony that

lack of schools for blacks prompted the "depletion of black

people from surrounding towns" into Kansas City). An expert

for the schoolchildren described the impact of Missouri's sys

tem of school segregation as a lost opportunity to take advan

tage of the naturally high degree of residential integration once

characterizing the 3-county area. Tr. 14,805-6, 15,286-7. Mis

souri's demographer admitted that the "existence of a core of

blacks caused by [governmental segregation] in the Kansas City

area would have long lasting effects [because] . . . blacks tend to

move short distances from the core . . . and in-migration [of

blacks] tends to focus on that black core as a result of . . . infor

mational networks." Tr. 22,076, 22,091.

6

separate schools [for blacks] . . . to districts, including the

KCMSD, that provided black schools." 593 F.Supp. at

1490.

The district court found that the "intensity" of the

"segregation" that resulted from state-mandated shifts in

the black and white population in the Kansas City area

"is dem onstrated by the fact that the average black family

[in Kansas City] lives in a census tract that is 85% black

while the average white family [in the suburbs] lives in a

census tract that is 99% w hite." 593 F.Supp. at 1491.

D. Post-1954 Violations

After ninety years of vigorous crim inal and civil

enforcement of school segregation prior to 1954, Missouri

informed local school districts six weeks after Brown v.

Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954), that they henceforth

could make their own decisions about whether, where,

and how to educate black students.10

The district court found that, notwithstanding the

State's acknowledged ability throughout the period to

"do som ething about this entire m atter of having segre

gated schools in M issouri by requiring reorganization [of

boundaries] where [segregation] o ccu rs ,"11 the State

10 P.Ex. 2322. (June 30, 1954 opinion of the Missouri Attor

ney General informing districts that they "may . . . permit white

and colored children to attend the same schools" but assuring

them that it was up to them to decide "whether [they] must

integrate").

11 State education officials have long acknowledged the

State's ability to solve the problem of its segregated schools.

When a federal court ordered the consolidation of three small

Missouri school districts as a remedy for unconstitutional

school segregation in 1975, and members of the Missouri Gen

7

procrastinated for exactly thirty years after Brown - until

a desegregation order was entered - before taking any

steps to desegregate the black children segregated within

the KCMSD. 593 F.Supp. at 1505 (finding that Missouri

"cannot defend its failure to affirm atively act to eliminate

the structure and effects of its past dual system ").

With the State Attorney General's authorization, and

the State Board and Department of Education's knowl

edge and acquiescence, the KCMSD acted repeatedly dur

ing the twenty years following Brown to extend its dual

system, eventually concentrating more black children in

the district's expanding black core and causing white

families to move from the area to all white attendance

zones just inside or outside the KCM SD's boundaries.12

KCMSD expanded the dual system of schools in the area

eral Assembly inquired about the matter, Missouri's Commis

sioner of Education, in letters to state board of education

members, noted:

It is interesting that members of the General Assem

bly directly associated with this matter are just now

getting involved. However, I guess I am not surprised

because I know the General Assembly would like to

stay out of this area of controversy altogether. I have

tried to keep them out by saying to everyone involved

that the Missouri General Assembly really cannot do

anything about. . . [school segregation]. It is true that

the General Assembly could do something about this entire

matter of having segregated schools in Missouri by requir

ing reorganization where it occurs but I doubt if we'll see

that.

P.Ex. 2463. (Emphasis supplied)

12 In 1977, when this action was filed, 25 of the pre-1954 one

race schools remained 90% or more of the same race and 80% of

all blacks in Kansas City attended schools that were 90% or

more black. Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1492. In 1954 the KCMSD

operated 14 schools for only blacks. At trial, in 1984, 24 schools

had 90% or more black students. Id.

8

by several means: gerrymandering attendance zones;13

turning schools from all-w hite to nearly all black in a

single year;14 explicitly segregating classroom s within

potentially integrated schools;15 letting whites in racially

transitional schools transfer freely to all-white schools

throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s; repeatedly

selecting segregative sites for new schools during the

same period; racially targeting faculty assignments; and

replacing math and science courses in previously all-

white schools with courses, for example, in "janitorial

services" for the black children newly segregated in those

schools.16 The district court found that the direct effects

of branding black children as unfit classmates (or even

recess- or lunch-m ates), and making blacks' education

13 During one short span of time, the district gerryman

dered school attendance boundaries over three hundred times,

usually changing lines by only a block or two, to assure that the

growing black population remained in all-black school atten

dance zones.

14 Ex.K2; Stipulation of February 21, 1984 (by moving

boundaries into the expanding black core ten or fifteen blocks

and by inviting the remaining whites in the new attendance area

to take advantage of the KCMSD's Liberal Transfer Policy to

transfer to all-white schools, the district turned virtually all-

white elementary schools into virtually all-black schools in a

single year). Central High and Junior High Schools were the

first secondary schools that the KCMSD's segregative policies

tipped from all white in 1955 to 95%+ black by 1960. Ex.K2.

15 593 F.Supp. at 1494 (for years black schoolchildren in the

1960s walked to the overcrowded elementary school near their

homes from where they and a black teacher were bused to an

under-utilized white school where they were given their own

all-black classroom and made to take their own separate recess

and lunch periods).

16 Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1493-4. See also Tr. 7018-21,

7338-41, 8624-5, 8969-71, 9419-20; Stipulation 75 of February 21,

1984.

9

inferior were largely demographic: While blacks perforce

remained in their own, expanding, neighborhoods in the

core of KCMSD, the State's and KCMSD's violations "led

to white flight from the KCMSD to suburban districts, [a]

large num ber of students leaving the schools of Kansas

City . . . " 17

The district court also found that the racially restric

tive covenants that M issouri enforced until five years

after Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), the racially

segregated "dual housing m arket" that the State's hous

ing and insurance agencies "encouraged,"18 the State's

explicitly racially segregated relocations of persons dis

placed by highways and urban renewal programs, the

State 's history of discrim inatory actions in regard to

schools, housing, m arriages and other practices, and

KCM SD's continuation of its segregative school policies

in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s with the State's blessing

"created an atm osphere in which private white individ

uals could justify their bias . . . against blacks," thus

encouraging racially discrim inatory redlining, steering

and blockbusting in insurance, real estate and banking

and further steering blacks into the KCMSD and whites

into outlying areas. 593 F.Supp. at 1503.

Among the effects of these violations that the district

court found are the following: (i) Black children within

the KCMSD were subjected to system-wide racial isola

tion of great "intensity." 593 F.Supp. at 1485 (rejecting

M issouri's argum ent that factors other than schools

caused the intense segregation), (ii) A "large number of

17 Order, August 25, 1986 at 1; Tr. 8715-6, 8721-30, 9228-32,

9235 (cited at 593 F.Supp. at 1494); Tr. 17,314-16 (admission by

Missouri that KCMSD underwent rapid transformation as

"whites fled the district").

18 Jenkins, 593 F.Supp. at 1491, 1503.

10

[white] students" and their families fled the KCMSD for

"suburban d istricts."19 (iii) As "m any residents of the

KCMSD left the district and moved to the suburbs" with

their children, the KCMSD was left with a white voting

majority that was without children or was unsupportive

of the district's mainly black student population and that

for nearly two decades "refused to approve a tax levy

increase and a bond issue." 672 F.Supp. at 412. (iv) These

financial restrictions on the district led to "rotted" and

"generally depressing" physical facilities. Id. at 403, 411.

As the court of appeals noted:

The findings of fact dem onstrate a spiraling

effect of white children leaving the KCMSD

schools and KCM SD's white constituency with

drawing its financial support from the system.

This process eventually caused the decay of

KCM SD's school buildings, which in turn fed

the cycle.

855 F.2d at 1305. (v) Throughout the 30 years after Brown,

the educational achievem ent of black children suffered,

as the "inferior education indigenous of the state-com

pelled dual school system caused" a "system wide reduc

tion" in student achievem ent in the schools of the

KCMSD, 593 F.Supp. at 1492, 639 F.Supp. at 24. As a

result, the district's educational-quality rating from the

State dropped to lowest in the area, and the district's

ability to retain nonminority students declined further.

639 F.Supp. at 24, 26, 29.

M issouri did not appeal any of the district court's

findings as to the nature and scope of its violations, nor

did it appeal the findings of pervasive, system wide

19 Order, August 25, 1986, at 1-2. See e.g., Tr. 12993-4, P.Ex.

53G, K.Ex.2 (nearly 15,000 whites left KCMSD schools in waves

over 15 years as the defendants' violations spread through the

school district).

11

demographic, physical, and educational effects caused by

those violations.

Although the district court found that these findings

added up to a history of constitutional violations with

"intens[e]" segregative effects, it concluded that the inno

cence of the suburban school district defendants in caus

ing the racial transform ation of area schools and the

absence of sufficient segregative effects in any particular

district, aside from the KCMSD, precluded the inclusion

of the suburban districts in an interdistrict remedy.20 The

district court thereupon ordered proposals for a remedy

limited to the KCMSD, except insofar as voluntary mea

sures might enable black children to attend school in the

suburbs and enable suburban white children to attend

magnet schools in the KCMSD at state expense.

D. The Ordered Rem edies

As the district court began devising a remedy for the

violations it had found, it laid out two legal standards

that it would follow. It noted that "the scope of the

20 593 F.Supp. at 1488 ("plaintiffs simply failed to show that

those [suburban district] defendants had acted in a racially

discriminatory manner that substantially caused racial segrega

tion in another district"). In January, 1985 the schoolchildren

and KCMSD submitted their first proposed remedy, a broad

interdistrict consolidation plan, that would have created fully

integrated schools at comparatively little cost to Missouri.

KCMSD Plan For Remedying Vestiges of Segregated Public

School System, docket no. 1046. The State did not support the

proposal, and the district court declined to consider it, requiring

instead the submission of plans that imposed no obligations

upon surrounding school districts. Order, January 25, 1985. An

equally divided en banc court of appeals affirmed, 807 F.2d 657

(8th Cir. 1986), and this Court denied the schoolchildren's peti

tion for certiorari to review the denial of interdistrict relief. 484

U.S. 816 (1987).

12

remedy is determ ined by the nature and extent of the

constitutional violation," and that the goal of a remedy is

to prohibit new violations and eliminate the "vestiges of

state imposed segregation." 639 F.Supp at 23 (citing M illi-

ken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 744 (1974)). Missouri never

challenged these principles in the district court, the court

of appeals or this Court.

Rejecting the plaintiffs' requests for a remedy involv

ing mandatory interdistrict busing and M issouri's sug

gestions that the remedy focus on busing children from

one part of the 75-percent m inority KCMSD district to

another, the district court in 1985 ordered a plan aimed at

achieving two goals: (i) removal of the educational defi

cits to which the State's intentional segregation had sub

jected the black children within the KCMSD and (ii)

voluntary integration efforts aimed at reversing some of

the racially segregative effects of the State's violations.

639 F.Supp. 19.21

In order to elim inate inferior schooling, the court

directed the KCMSD to implement plans (i) to achieve a

more satisfactory academ ic rating from the State by

improving KCMSD libraries and reducing teaching loads,

(ii) to institute early childhood and remedial summer

school program s, and (iii) to undertake the capital

improvements necessary to assure that these educational

program s operated in adequate buildings. The court

found that such measures were necessary to "restore the

victims of discrim inatory conduct to the position they

would have occupied in the absence of such conduct." Id.

at 23.

21 Two consecutive orders are reported together at 639

F.Supp. 19. The initial remedy order of June 14, 1985 appears at

639 F.Supp. 19-46, aff’d, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986), cert, denied

484 U.S. 816 (1987). The order on pending motions of June 16,

1986 appears at 639 F.Supp. 46-56.

13

In order to reduce the racial isolation of KCMSD's

black children, the court initially invited the State to seek

the voluntary participation of surrounding districts in a

transfer program by which KCMSD's minority students

could volunteer to attend school in cooperating school

districts nearby.22 Id. at 38. In a survey ordered by the

district court, thousands of black children expressed an

interest in transferring out of the KCMSD to suburban

schools. The court hoped that facilitating such transfers

would "serve to provide additional opportunities for

desegregated schools [within the KCMSD] as well as

desegregative educational experiences for KCMSD stu

dents [in surrounding districts]." Id. Educating KCMSD's

black students in the already existing and educationally

appropriate classrooms of surrounding districts to which

the State's violations previously had propelled the dis

trict's white students would have served to avoid the

expense of renovating the KCM SD's "rotted" schools and

of installing costly magnet facilities in the KCMSD to try

to attract white students back from those surrounding

districts.

For several years after the district court's initial rem

edy in 1985, M issouri did not act on the district court's

order to develop a voluntary transfer plan. In 1986, the

district court admonished the State for its inaction. 639

F.Supp. at 51 (warning the State that continued inaction

will result in the court seeking "other methods of [deseg

regation] at the State's expense"). In 1990, after continued

inaction by the State, the court of appeals ordered sub

mission of a transfer plan. 904 F.2d at 419. The plan

22 Numerous school districts are nearby. In addition to the

KCMSD, the City of Kansas City includes all or parts of 12

school districts. A dozen others are nearby.

14

submitted in 1990 resulted in only ten KCMSD black

students transfering to a single suburban district.

Having decided against the mandatory busing of stu

dents to and from the suburbs, Order, January 25, 1985,

and to and from the KCM SD's predominantly minority

schools, 639 F.Supp. at 35, and faced with M issouri's

failure even to try to induce voluntary transfer efforts,

the district court considered other plans. It found that

only two other devises were available to cure the State's

intentional segregation of blacks within the KCMSD:

m agnet sch ools d esigned to d esegregate K C M SD 's

schools voluntarily by attracting back some of the whites

whom the violation had caused to leave the district, and

capital improvements designed to repair the "generally

depressing" physical condition in which the State and

KCMSD's violation had left the district's facilities and

thus to remove one cause of white abandonment of the

district as a result of the violation.

The district court thereupon ordered the KCMSD to

convert to magnet schools in order to "generate voluntary

student transfers resulting in greater desegregation in the

district schools" and "draw non-minority students from

the private schools . . . and draw in additional non

m inority students from the suburbs." Order, November

12, 1986, at 3, aff'd, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

490 U.S. 1034 (1989). The court of appeals affirmed the

district court's findings that the violations had directly

caused the segregation of blacks within the KCMSD and

whites outside the district, and also affirmed the district

court s determ ination that the "com prehensiveness of the

15

[magnet] plan was a step in the right direction" of undo

ing that unlawful segregation. 855 F.2d at 1304. In partic

ular, the court of appeals determined that the magnet

school orders were:

bolstered by the district court's findings that the

preponderance of black students in the district

was due to the State and KCMSD's constitu

tional violations, which caused white flight. . . .

These findings that the unconstitutional

segregation caused the KCMSD to lose certain

students form the basis for a remedy designed

to attract them back.

Id. at 1302. The court of appeals found that the magnet

school plan was "am ply supported by the State's own

evidence." The court of appeals further concluded that

there was no evidence to support M issouri's contention

that the magnet schools would not achieve voluntary

desegregation of KCMSD schools. Id. This Court declined

to review the magnet school judgments of the lower

courts. 490 U.S. 1034 (1989).

In 1987 the district court next addressed the financial

effects of the violation, namely, white voters' chronic

refusal to vote funds for the district, and the consequent

need for capital improvement. The court first requested

the parties' assistance in suggesting ways that the chron

ically underfunded d istrict could meet the financial

requirements of the desegregation remedy. Order, July 16,

1987 at 16. M issouri replied, asking that the KCMSD,

rather than the State, be required to pay the full 50 per

cent share of the remedial expenses originally allocated to

the district, and acquiescing in proposals for mandatory

local tax increases, which the court thereupon ordered.23

23 672 F.Supp. 400. The court of appeals affirmed, modify

ing the manner in which the taxes were to be increased. 855 F.2d

16

The district court next ordered a capital improvement

plan to cure the financial and physical effects on the

KCMSD of the State 's violations and the consequent

desertion of the district by white families and voters. The

court found that unconstitutional segregation was in part

responsible for the massive decay of school district build

ings because the concentration of blacks and degradation

of the district's educational programs made it impossible

for the m ajority black district to secure the votes needed,

from the still m ajority white voting population, to pro

vide funds for repair and maintenance of its buildings.

672 F.Supp. at 403. In particular, the court found that the

violations contributed to "num erous health and safety

hazards, educational environment hazards," "inadequate

lighting," "odors from unventilated restrooms with rot

ted, corroded toilet fixtures," "noisy classroom s" because

of poor acoustical treatm ent, "faulty heating and electri

cal system s," and "inadequate fire safety system s." Id.

Overall, the court found that buildings were in such

disrepair as a result of the violation that even principals

would not send their own children to them. Repairing

those facilities was thus found to be "crucial" to the

success of the voluntary desegregation plan.

The district court found that renovations of some and

replacem ent of other buildings were necessary to (i)

restore to victim s of segregation the facilities denied to

them by the violations, (ii) undo some of the educational

harms caused by the violation, and (iii) upgrade facilities

to a level that would not continue to discourage white

enrollment. The district court further found that capital

improvements were "crucial to the overall success of [the]

desegregation plan." Id.

1295. This Court affirmed the tax increase as modified by the

appeals court, 110 S.Ct. 1651 (1990).

17

The court of appeals affirmed findings that the defen

dants were to blame for the deteriorated facilities of the

school district, that the improvements were necessary to

achieve the desegregation of the district, and that the

capital plan was not excessive to the requirements of the

desegregation plan nor beyond the scope of the viola

tions. Id. 855 F.2d at 1304-5.

E. M issouri's Specific Com plaints

Central High School was the first high school that the

State's and KCM SD's post-1954 violations caused to turn

from an all-w hite to all-black school in the space of a few

years. See supra note 14 and accompanying text. By the

time the court had adjudicated the violation and was

devising a remedy, Central was an all-black high school

located in the center of an all-black residential corridor

created by the State's housing violations and the district's

school violations. Pet. App. at A42. See supra pp. 6-9. By

then, the school was virtually falling down around its

students. As the court found, restoring the integrated

student population that Central would have had in 1954

had the district and the State required the integrated

populations living near the school to attend it posed a

"challenge" thirty years later. In the magnet school order

not here at issue, the court directed that Central be reno

vated or replaced. Order, November 12, 1986. That plan

provided for a dual theme magnet high school featuring a

computer-based educational plan and a "Classical Greek"

theme featuring a combination of rigorous academic and

athletic program s. The d istrict court noted that the

"extensive" facilities and budget provided for in the plan

were "necessary" to achieve "the difficult task of deseg

regating Central High School." Pet. App. at A49.

As the school district developed its design docu

ments for C entral, it discovered errors and incorrect

18

assumptions in the estim ates underlying the court's origi

nal budget and sought the district court's approval for a

revised budget. In approving the adjustments, the district

court found that the school district had used proper

budgeting procedures, had eliminated nonessential fea

tures of the plan, and had reduced costs wherever possi

ble. Pet. App. at A49. It found a second time that the

desegregative magnet program for Central "could not be

successfully implemented in a lesser facility." Id.

On appeal, the court of appeals held that the condi

tions the district court identified as requiring a budget

adjustment were properly found as a matter of fact. The

appellate court accordingly concluded that the district

court had properly m odified the prior injunction "in the

exercise of equitable discretion," and affirmed the mod

ified Central High School plan. Pet. App. at A32-34.

The State did not seek a stay of the district court's

order, and the KCMSD thereupon completed construction

of Central High School. Nearly 1200 students are now

enrolled in Central, including a significant and growing

number of nonm inorities.24

2. Asbestos. The capital improvements that the dis

trict court found were necessary to cure the educational,

fin an cial, and dem ographic effects of the v iolation

required the KCMSD to renovate certain structures and to

dem olish others. Federal law 25 in turn required the

KCMSD, in carrying out those renovation and demolition

24 Central, in this its first year in the new school, has 31.2%

nonminority enrollment in the Classical Greek theme and 13.2%

in the computers theme. Before the remedy was ordered Central

was 99.7% minority. Ex.K2.

2o Asbestos Hazard and Emergency Response Act, 15

U.S.C. §§2641-2654 (1988).

19

orders, to meet certain standards concerning the abate

ment of asbestos in public buildings undergoing con

stru ction and repair. F inding that the S ta te 's and

KCM SD's constitutional violations were the reason why

renovations were required and, thus, were the reason

why federally mandated asbestos abatement had to occur,

and finding that elim inating health hazards was an

important component of a cure for the district's educa

tional deficits and necessary to the success of the deseg

regation plan, Pet. App. at A56, the district court found

that the expense of m eeting the asbestos abatem ent

requirements of federal law was a part of the overall

desegregation expense. The court accordingly ordered the

State and the KCMSD to share equally in the cost of

abating asbestos that was likely to be dislodged in the

course of com pleting the capital improvement plan.26

The court of appeals affirmed. Pet. App. at A24-26. It

found that, in the "unique circumstances presented here,"

asbestos abatement during building work was necessary

to assure "safe and healthy school facilities that are not

an obstacle to education or to desegregation." Pet. App.

at A-25.

The asbestos abatement tasks in the capital improve

ment work ordered by the district court are now virtually

complete.

REA SO N S FOR DENYING THE W RIT

Unasham edly candid in its petition, the State of Mis

souri all but admits that the questions it here presents are

26 Similarly, the school district's capital program ordered

by the court includes the cost of compliance with minimum and

prevailing wage laws,. OSHA's construction safety standards,

and air quality standards. The State does not challenge those

components of the plan.

20

not them selves worthy of this Court's plenary attention.

Scrutiny of M issouri's petition yields not a hint of a

conflict in the circuits nor even a suggestion of an im por

tant federal question presented by the budget-adjustment

and asbestos-abatem ent matters that are all that is actu

ally before the Court. Instead, Missouri freights two nar

row, technical orders with the full weight of a remedy

devised over alm ost a decade and grounded firmly in the

nature and scope of the unique set of violations that

necessitated the remedy. In the process, the State asks the

Court to review (i) the district court's violation findings,

which the State never appealed; (ii) the district court's 1984,

1985, 1986, and 1987 findings detailing the various educa

tional, financial, physical, and racially segregative effects

of the State's violations, which the State never appealed ;

(iii) the district court's 1985, 1986, and 1987 remedy

orders, which the State either never appealed or as to

which this Court previously has denied certiorari; and (iv)

two more recent technical orders requiring certain reme

dial adjustments and details, as which the State never

sought a stay and which accordingly are now, or soon to

be, entirely completed.

The uninteresting, and now almost entirely academic,

questions (whether, in the course of capital improve

ments, it was proper to make the school district adhere to

federal asbestos-abatem ent safety standards and whether

it was proper to correct estim ation errors in the budget

for a construction project previously affirmed on appeal)

do not themselves m erit this Court's review and cannot

bear the weight of the many long-since-resolved issues

that M issouri attem pts to load upon them. Nor is there

any reason to bootstrap a wider review of previously

unappealed orders onto those two mundane questions.

21

A. THE LEGAL STAN D A RD S ON W HICH THE D IS

T R IC T COURT RELIED IN SHAPING THE REM

ED Y A RE U N O B JE C T A B L E , M A N D A TE TH E

R E M E D Y O R D E R E D , A N D W E R E N E V E R

APPEALED BY THE STATE.

In its first remedy order in 1985 the district court

adopted as its guiding principles the very constitutional

lim itations on rem edies that the State claim s were

ignored.27 The court insisted that "th e scope of the

remedy [be] determined by the nature and extent of the

violation" and that the remedy eliminate "the vestiges of

state imposed segregation." 639 F.Supp. at 23 (citing Mil-

liken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 744 (1974)). M issouri has

never challenged the appropriateness of these principles.

The court then proceeded to make findings of fact

that linked violations to effects and linked effects to each

component of the remedy the court ordered. Specifically,

the court first found intentional segregation of blacks in

the KCMSD and intentional degradation of the district's

education program. The district court next found that

these violations caused an "in tense!]" concentration of

blacks within the KCMSD, "inferior" educational oppor

tu n ities, and a "sy stem w ide redu ction in stu dent

achievem ent," 639 F.Supp. at 24, which in turn, caused

"large num bers" of whites to flee from the KCMSD to

suburban districts. Order of August 25, 1986. Next, the

court found that in the absence of feasible and legally

warranted m andatory-busing plans, and given the State's

refusal to arrange for a transfer of blacks to the suburbs,

27 6 39 F.Supp. at 23 (relying on Milliken, Columbus Bd. of

Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979), Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brink-

man, 433 U.S. 406 (1976), Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971), Keyes v. School District No. I, 413 U.S. 189

(1973), Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963)).

22

only a magnet school plan could be a valuable and effec

tive means of desegregating the district by attracting back

a voluntarily integrated enrollment. Order of November

12, 1986. Finally, the court found that improving the

buildings of the school district was "crucial to the overall

success of the desegregation plan" and to overcoming the

educational and physical effects of the violation. 672

F.Supp. at 403. None of those fact findings has ever been

challenged by the State as erroneous.

In reviewing the remedy orders, the court of appeals

relied on the same principles, 855 F.2d at 1299, approved

the d istrict court's fact findings, tested the remedies

adopted against the lim iting principles in M illiken and

other cases, and affirmed the remedies.

To this date, M issouri has never claimed that the legal

standards the courts below applied are incorrect, nor that

the district's "v iolation" findings are incorrect, nor that

the district court's effects (or "vestiges") findings are

in correct, nor that there should be no educational

improvements to cure some of these effects, nor that

magnet schools and voluntary transfers are impermissible

means of curing other effects, nor that capital improve

ments are anything other than "crucial" to the success of

the overall plan to cure the violations, nor that Central

High School should not be replaced, nor even that

asbestos should not be abated when necessary restora

tions take place.28 Because the parties are in agreement on

the applicable legal standards, because those standards

28 Indeed, before the district court entered the order now at

issue, the State proposed its own asbestos abatement program,

including its own request that the State be ordered to fund that

abatement. State's Ex. 9 (August, 1987). Furthermore, as the

court of appeals found, Missouri "did not appeal earlier orders

of the district court and this court that included asbestos abate

ment costs." Pet.App. at A26.

23

premise an appropriate remedy on the district court's

findings of violations, effects and necessary measures to

cure those effects, and because the district court made,

the court of appeals affirm ed, and in most cases the State

never appealed the requisite findings, there is no ques

tion of interest that is presented by this case.

B. The State's D efaults Since The Rem edial Process

Began, and Not Any Error by the Lower Courts, Are

R esponsib le for the Rem edial Expense.

The d istrict co u rt's findings of u nconstitu tional

school segregation placed M issouri immediately under an

"affirm ative duty to take whatever steps might be neces

sary" to cure the segregative, educational and other

effects of that violation. Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449, 459, (1979) (quoting Green v. County School

Bd., 391 U.S. 430, 437-38 (1968)). Explicitly invoking the

State's constitutional obligation, the district court con

cluded its findings of violations by calling upon the State,

on its own, to remedy the effects of its violation. 593

F.Supp. at 1505. Most specifically, the Court noted that

the M issouri General Assembly "established the school

districts and if it deems necessary, can change them " to

achieve desegregation. Although the State's chief state

school officer reached the same conclusion even before

the d istrict cou rt rendered its d ecisio n ,29 M issouri

ignored the court's invitation.

In 1985 the school district and the Jenkins class pro

posed a com prehensive remedy that would have consoli

dated area districts and achieved desegregation instantly

and at very little cost to the State. Missouri opposed a

mandatory interdistrict remedy, and the district court

rejected it. Order, January 25, 1985. In 1985 the district

29 See supra note 11 and accompanying text.

24

court invited plans for magnet schools, 639 F.Supp. at 34,

but again M issouri chose to submit no plan whatsoever,

leaving the district court with no alternative but to work

from the plan jointly submitted by the plaintiff school-

children and the KCMSD.

Also in 1985, the court asked the State to use its good

offices to establish a transfer plan for m inorities to attend

school in volunteering suburban school districts. 639

F.Supp. at 38. Among the beneficial features of such a

plan to overcome the State's "intensive" concentration of

blacks in the KCMSD would be its minimal cost, inas

much as integrated sets of students could be educated in

existing and educationally attractive facilities in the sub

urbs, in lieu of requiring the KCMSD to tear down old

schools (abating asbestos in the process) and build new

ones (among them Central High). Again, the State did not

act. In 1986 the district court admonished the State to act,

threatening to find "other methods of accomplishing this

task at the State's expense." Id. at 51. Still, the State failed

to establish a transfer program even though its success

would have greatly reduced the expenses of the volun

tary KCMSD plan about which it continues to complain.

Similarly, when the district court in 1987 sought sug

gestions for helping the KCMSD fund its share of the

desegregation costs, the State offered no plan, expressed

no opposition to the schoolchildren's motion for a court-

ordered tax increase, and insisted that means be found to

enable the school district to pay its own share. Yet, when

the district court adopted the only proposal before it, in

which the State previously had acquiesced, the State sud

denly objected and brought the matter to this Court - still

without alternative suggestions.

In summary, over and over again for nearly 40 years

now, the State has adhered to a single unconstitutional

and unhelpful pattern of action in this case: defaulting in

25

its prim ary duty to cure the effects of its violation;

defaulting in its fail-back duty to propose remedies for

the court's consideration; w ithholding objection from,

and even supporting, aspects of the remedy that the

Court is considering; and then complaining after-the-fact

about the expense of remedies that it never previously

opposed and that were necessitated by the extent and

continuation of its violations and by its rejection of less

costly remedial options.

Now, M issouri again attacks a remedy for which it

has proposed no alternative of its own, as to which it has

resisted every alternative remedy proposed by others,

and about which it has limited its contribution to after-

the-fact com plaints about expense. The violations found

against M issouri, and never appealed, caused "a large

number of w hites" to flee the school district to the sub

urbs, degraded the educational opportunities for the

m inority students left behind, and literally "rotted" the

district's instructional plan. Missouri accordingly placed

itself under a continuing obligation to the schoolchildren,

and to the courts, to eliminate those effects, an obligation

satisfied only by effective actions to decrease the effects

of its segregation. Columbus, 443 U.S. at 459. Yet, in this

Court, as consistently below, Missouri fails to identify

how the schoolchildren will be relieved of harms that no

party denies the State caused and that no party doubts

still exist.

Moreover, the State itself is responsible for the single

aspect of the remedy about which it complains, namely,

cost. According to the district court's findings, the State

intentionally segregated blacks within the KCMSD for

120 years prior to Septem ber 1984, causing the system-

wide racial segregation of the district, generating perva

sive education decline, and resulting in massive physical

decay. The cost of curing these illegally caused conditions

26

is undoubtedly expensive. But how could a cure for 120

years of determ ined and racially, educationally, and phys

ically costly violations be other than expensive?

Accordingly, whether because of its ongoing consti

tutional default, its unclean hands, or its having repeat

edly sandbagged the district court, the State has no valid

com plaint about a remedy that its unlawful pre- and

post-Brown actions required or a remedial expense that its

post-1984 inaction has singlehandedly inflated.

C. The Rem edy is M anifestly W ithin the Court's D is

cretion G iven its Avoidance of Rem edial Burdens

on Parties O ther Than Those D irectly R esponsible

for the V iolation and its Effectiveness.

Initially, the Jenkins class of schoolchildren favored

and sought an interdistrict remedy but the district court

denied consolidation relief, concluding that the remedy

would excessively intrude the court in the affairs of the

suburban school districts. The court then noted that the

M issouri General Assembly had created those districts

and could easily and integratively reorganize them if it

chose. "If such legislation is the only means by which the

State can fulfill its fourteenth amendment obligations,"

the court wrote, "then such legislation is mandatory." 593

F.Supp. at 1504. The General Assembly chose not to act,

however, and the court chose not to make it act - again

given the extent to which such an order, although sup

portive of the least expensive and most effective remedial

option, might intrude on the interests of innocent subur

ban jurisdictions and citizens.

The district court next asked the State to use its good

offices to secure voluntary participation by the suburbs in

a volu ntary in terd istrict desegregation remedy. 639

F.Supp. at 38. W hile more expensive than a remedy that

simply redrew boundary lines, such a plan still would

27

have been less expensive than having to build magnet

schools and refurbish facilities in the KCMSD. Nonethe

less, despite repeated orders by the district court, the

State refused to act. Absent action by the State, and

barring pressure by the court on innocent suburban dis

tricts, parents, and children, the remedial constraint on

involving innocent parties trumped the remedial require

ment of effective removal of segregative vestiges, and no

interdistrict transfer was implemented.

In early 1985, the State proposed a mandatory infra

district remedy to move the plaintiff schoolchildren from

one inferior facility with substandard educational ser

vices and a m ajority black student body to another. Id. at

35. The district court rejected this approach as well - on

grounds that the State 's proposal not only burdened

innocent victim s of the violations but also would have

been entirely ineffective in removing the segregative and

educational effects of the State's violation.

Having rejected all these remedies as excessively

intrusive on the interests of innocent individuals and

suburban school districts and having rejected the State's

single proposal on the additional ground of remedial

ineffectiveness, the district court instead ordered a less

intrusive remedy: academic programs and ancillary relief

to rem edy the segregation-caused inferior education

available to students in the mostly minority KCMSD as

approved in M illiken v. Bradley II, 433 U.S. 267 (1977);

voluntary transfers of nonminorities to magnet schools as

also approved in id.; and refurbished buildings in the

KCMSD to reverse some of the physical, educational and

segregative effects of the State's violations.

It is true that the remedy imposed was more expen

sive than the other proposals. It also is true, as plaintiffs

have repeatedly made clear to the district court, that this

remedy is (and rem ains) less satisfactory to them -

28

because it is less im mediately effective - than either a

mandatory interdistrict consolidation plan or a manda

tory interdistrict transfer plan or even a m eaningful vol

untary interdistrict transfer plan. But the plan the court

chose has another virtue, which is legally decisive under

the this Court's rem edial-effectiveness decision in Green,

391 U.S. at 437-39, and its remedial-limits decision in

M illiken, 433 U.S. at 280, as interpreted by the district

court: among all the available plans, the one the court

imposed is the only one that holds out even a hope of

removing the vestiges of the State's violations and, at the

same time, does not m andatorily involve school districts

and schoolchildren who were not responsible for those

violations.

The district court can hardly be said to have abused

its discretion in selecting the only educationally and

desegregatively effective option that is available.

D. The Remedy Is Working

Having eschewed the broader, mandatory, and more

intrusive plans first presented to it, and having declined

M issouri's requests that the violations be left essentially

without a remedy, the district court adopted a middle

course and ordered a voluntary plan. As the court of

appeals noted, although the "KCM SD has only begun its

vast efforts to remedy the vestiges of the dual system of

education in the school district," 942 F.2d at 491, the

district court's plan already is bearing fruit. This year 913

new nonm inority students from the suburbs have been

attracted to the KCM SD's magnet schools - Central High

School among them - joining 778 nonminority students

who have re-enrolled from previous years. These 1,691

students have caused for the first time in two decades a

29

significant increase in the percentage of nonminority stu

dents in the KCMSD. September, 1991 Census of Students.

The educational programs and improved facilities tar

geted for the mostly minority students in the KCMSD also

show early signs of working. Science and math scores in

many schools have especially shown dramatic improvement,

reversing trends suffered in most urban schools.30

E. The Asbestos Abatement And Budget Adjustments to

Which the State Objects Are Necessary, Proper, and

Entirely Non-Controversial Components of the Reme

dial Effort

If, as Missouri never disputes, magnet schools are

appropriate remedies for its violations, and if, as Missouri

never disputes, buildings must be renovated to house those

schools, and if as federal law requires and both courts found

below, asbestos necessarily must be abated from buildings

being renovated, then what possible objection can there be to

include abatement in the remedial budget? Unable to chal

lenge the fact findings that some construction is required as a

part of the magnet remedy, that abatement is then required,

and that the costs of abatement are thus necessarily costs of

the magnet remedy, the State is reduced to attacking the

overall price tag on a set of remedies that are not before the

Court, in which the State has largely acquiesced, and as to

which the State has no legally or equitably sound objection.

Similarly as to the Central High costs estimates, if con

struction of a new school is required by the magnet school

remedy, the district court may estimate construction costs

and change them upon appropriate fact findings to correct

errors. No more than that was done by the lower courts, and

30 "Since 1987, KCMSD scores have improved on every

subtest at every grade level" except two. Missouri Mastery and

Achievement Tests, Spring, 1991 Performance at 2.

30

none of it is here challenged by Missouri for being based on

erroneous findings. Thus, as to Central also, the State finds it

must attack the remedy itself.

The original 1985 remedy order, 639 F.Supp. 19, pro

vided for both magnet schools and capital improvements.

The State did not appeal the magnet school order and the

provision for capital improvements was affirmed, 807 F.2d at

685, and Missouri did not seek certiorari. Missouri thus seeks

relief from principles established in orders entered nearly

seven years ago, principles it does not challenge, and from

fact findings implementing those principles, fact findings it

does not challenge as erroneous. There is thus no basis for

accepting Missouri's invitation to use two narrow orders as

the means for a broad and wholesale review of a remedy

properly adopted years ago and appropriately implemented

ever since.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the writs should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

" A rth u r A. B en so n II

1000 Walnut Street

Suite 1125

Kansas City, MO 64106

816/842-7603

T h eo d o re M. S haw

University of Michigan

School of Law

Hutchins Hall

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

313/763-7868

J a m es S. L iebm an

Columbia University

School of Law

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

212/854-3423

"■Counsel of Record

October 28, 1991 Attorneys for Respondents Jenkins et al.