NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. US Dept of the Army Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

October 16, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. US Dept of the Army Brief of Appellant, 1989. 0c850922-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/68b6f063-a7e2-4c37-8672-a10acca2192c/naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-v-us-dept-of-the-army-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

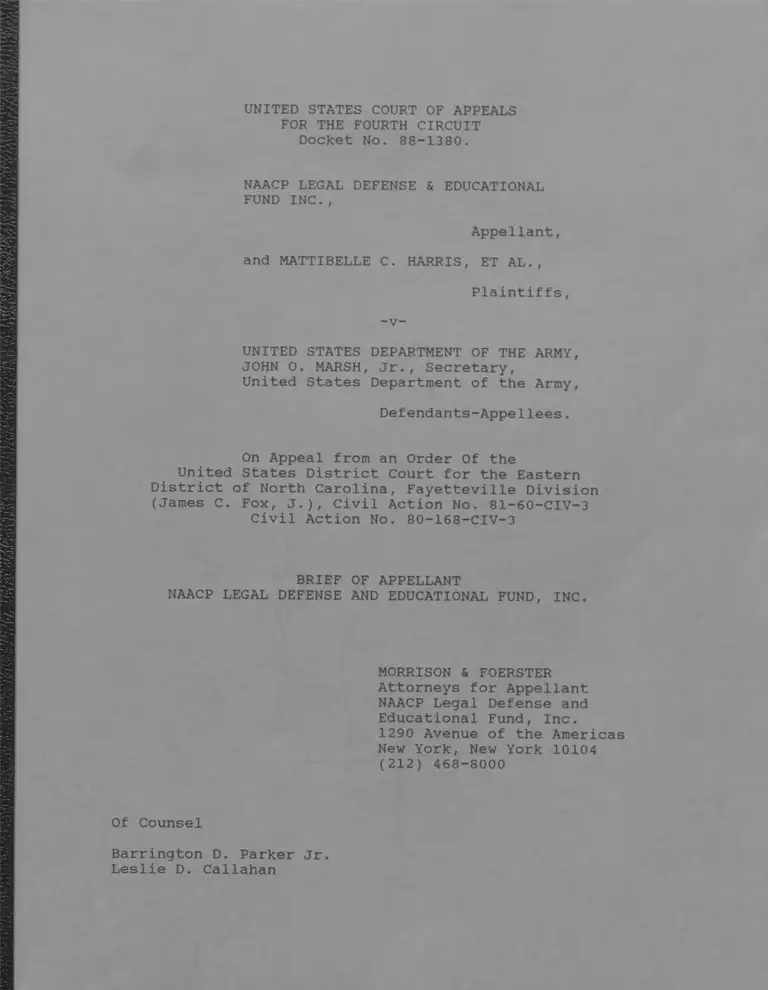

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Docket No. 88-1380.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND INC.,

Appellant,

and MATTIBELLE C. HARRIS, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

-v-

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY,

JOHN 0. MARSH, Jr., Secretary,

United States Department of the Army,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from an Order Of the

United States District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina, Fayetteville Division

(James C. Fox, J.), Civil Action No. 81-60-CIV-3

Civil Action No. 80-168-CIV-3

BRIEF OF APPELLANT

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

MORRISON & FOERSTER

Attorneys for Appellant

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10104

(212) 468-8000

Of Counsel

Barrington D. Parker Jr.

Leslie D. Callahan

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Preliminary Statement............................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES........................... 4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE............................. 5

A. Nature of the Appeal..................... 5

B. The Facts ............................... 6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................... 9

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT VIOLATED

DUE PROCESS BY ENJOINING LDF

WITHOUT PRIOR NOTICE, A HEARING

OR PERSONAL JURISDICTION................. 10

A. LDF received no

notice or hearing

regarding the court

order barring contributions

to the sanctions award............... 10

B. The District Court did not

have personal jurisdiction

over the Legal Defense Fund.......... 12

II. THE DISTRICT COURT HAD NO

LEGAL BASIS FOR AN ORDER

AGAINST LDF.............................. 14

III. BY INTERFERING WITH LDF's

DECISIONS REGARDING

ALLOCATION OF ITS RESOURCES

IN SUPPORT OF CIVIL RIGHTS

LITIGATION, THE DISTRICT

COURT VIOLATED LDF's

FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS

OF FREE SPEECH AND ASSOCIATION 16

Page

A. LDF's right to contribute to

the sanctions award is an

activity protected by the

First Amendment...................... 16

B. No restriction on the

exercise of First Amendment

rights is constitutional

unless it is necessary to

serve a compelling govern

mental interest...................... 20

CONCLUSION........................................ 21

N24520

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

American Civil Liberties Union v.

Tennessee, 496 F.Supp 218

(M.D. Tenn. 1980)........................... 18

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona,

433 U.S. 350, 97 S.Ct. 2691,

reh*q denied, 434 U.S. 881 (1977)........... 18

Page(s)

Bowens v, N.C. Dep't. of Human

Resources, 710 F.2d 1015 (4th Cir. 1983).... 11

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v.

Virginia 377 U.S. 1, 84 S.Ct. 1113,

reh'q denied, 377 U.S. 960 (1964)........... 18

Commercial Security Bank v. Walker

Bank & Trust Co., 456 F.2d 1352

(10th Cir. 1972)............................ 5

Dracos v. Hellenic Lines, Limited

705 F.2d 1392 (4th Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 474 U.S. 975

(1985)...................................... 14

Eilers v. Palmer, 575 F.Supp.

1259 (D. Minn. 1984)....................... 19

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S.

254, 90 S.Ct. 1011, (1970).................. 11

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32,

61 S.Ct. 115 (1940)......................... 13, 14

Harris v. Marsh 123 F.R.D. 204

(E.D.N.C. 1988)............................. 3, 6, 8, 20

Harris v. Marsh, 679 F.Supp.

1204 (E.D.N.C. 1987)........................ 2, 3, 9, 20

Hutchinson v. United States 677 F.2d

1322 (9th Cir. 1982)........................ 14

In re Franklin National Bank

Securities Litigation, 574

F. 2d 662 (2d Cir. 1978)..................... 13

iii

Page(s)

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412,

98 S.Ct. 1893 (1978)........................ 18

Kenny v. Quiqq, 820 F.2d 665

(4th Cir. 1987)............................. 5

Kulko v. Superior Court of California

436 U.S. 84, 98 S.Ct. 1690,

reh'g denied, 438 U.S. 908 (1978) .......... 11

Louisiana v. NAACP,

366 U.S. 293, 81 S.Ct. 1333 (1961).......... 17, 20

Martin v. Wilks, ___ U.S. ___,

109 S.Ct. 2180, reh'g denied,

58 U.S.L.W. 3120 (1989) .................... 13

McKinney v. Alabama, 424 U.S. 669,

96 S.Ct. 1189 (1976)........................ 11

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Div.

V. Craft, 436 U.S. 1, 98 S.Ct.

1554 (1978)................................. 11

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People v. Alabama,

357 U.S. 449, 78 S.Ct. 1163 (1958)........... 17

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 83

S.Ct. 328 (1963)............................ 17

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People v. NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

753 F.2d 131 (D.C. Cir.) cert, denied,

472 U.S. 1021 (1985)....................... 3, 6

Roberts v. United States Jaycees,

468 U.S. 609, 104 S.Ct. 3244

(1984)...................................... 20

Sherrill v. Knight, 569 F.2d

124 (D.C. Cir. 1977)........................ 10

United Mine Workers Of America,

District 12 v. Illinois State

Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217

88 S.Ct. 353 (1967)....................... 18

iv

Page(s )

United States Transportation Union

v. State Bar Of Michigan, 401 U.S.

576, 91 S.Ct. 1076 (1971)................... 18

Warner Bros., Inc, v. Dae Rim

Trading, Inc., 877 F.2d 1120

( 2d Cir. 1989).............................. 5

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine

Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100,

89 S.Ct. 1562 (1969)........................ 5, 13, 14

Statutes and Rules

Fed. R. Civ. P. 4............................. 13

Fed. R. Civ. P. 11............................ 2, 3, 14

Fed. R. Civ. P. 16............................ 2, 3, 14

Fed. R. Civ. P. 19............................ 13

Fed. R. Civ. P. 65............................ 8, 10

28 U.S.C. SS 1291 and 1292(a)(1)............... 5

28 U.S.C. SS 1331 and 1332................... 14

28 U.S.C. § 1927.............................. 2

42 U.S.C. SS 2000e et seq..................... 2, 5

Other Authorities

9 J. Moore Moore's Federal Practice

1 203.06 (2d ed. 1989)...................... 5

N24531

v

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Docket No. 88-1380.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND INC.,

Appellant,

and MATTIBELLE C. HARRIS, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

-v-

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY,

JOHN 0. MARSH, Jr., Secretary,

United States Department of the Army,

Defendants-Appellees.

Preliminary Statement

Appellant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. ("LDF") submits this brief in support of its appeal

from a sua sponte order of the District Court enjoining LDF

from reimbursing litigants or their counsel any portion of

Rule 11 sanctions imposed on them by that Court.

LDF was not a party to proceedings below. The

District Court's order — which was tantamount to an

injunction — was preceded by neither notice to LDF of

threatened restrictions on its activities nor an opportunity

to be heard and issued in the absence of in personam or

subject matter jurisdiction. The order restricts LDF's

right to spend its money as it chooses in support of civil

rights litigation, a right guaranteed by the First Amendment

and recognized and respected by numerous Courts.

Following trial of various claims for relief

brought pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. Sections 2000e, et seq., United States

District Court Judge James C. Fox entered an order denying

them. Judge Fox then assessed sanctions against Plaintiffs

and their attorneys under Rules 11 and 16, Fed. R. Civ. P.,

under 28 U.S.C. Section 1927, and under the so-called common

law "bad faith" exception. Harris v. Marsh, 679 F. Supp.

1204 (E.D.N.C. 1987).

At the same time the District Court permitted

limited reallocation among the sanctioned parties, it sua

sponte ordered that "no monies may or shall be paid by the

NAACP or its Legal Defense Fund." (sic) 679 F. Supp.

at 1392. The Court explained its rational for restrictions

it felt necessary for the protection of LDF donors as

follows:

"Contributions are made to this

organization and its litigation branches

by members of the public who expect their

money to be used by staff lawyers in a

reasonable manner to pay for meritorious

cases. The NAACP is an historic

institution that has contributed

substantially to the racial progress of

this country. It continues to serve this

vital purpose and the court does not

2

propose to see any money diverted from its crucial mission."

679 F. Supp. at 1392, n.280. In a subsequent order dated

August 31, 1988 modifying the sanctions award in certain

respects, the Court below again ordered that "no monies may

or shall be paid by the NAACP or the LDF." Harris v. Marsh,

123 F.R.D. 204, 228 (E.D.N.C. 1988).

These orders, we respectfully submit, constituted a

conspicuously flagrant disregard of basic, well-established

rules of law and are pock-marked by a host of errors, both

procedural and substantive. LDF, a New York not-for-profit

corporation, was not a party to the proceedings below and

the Court therefore lacked in personam jurisdiction. LDF

was not claimed or found to have violated Rule 11, Rule 16

or to have done anything wrong. No litigant requested

sanctions or limitations of any sort against LDF and it had

no notice that any might be imposed. As a result, LDF had

1 The Court below was, apparently, confused as to

precisely which organization it sought to enjoin. The NAACP

has no Legal Defense Fund or litigation branches. Since

1966 LDF's literature and stationary has made clear that "it

is not a part of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People although it was founded by it

and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for

over 25 years a separate Board, program, staff, office and

budget." See National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People v. N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., 753 F.2d 131, 136 n.48 (D.C. Cir. 1985), cert.

denied, 472 U.S. 1021 (1985).

3

no opportunity to be heard or to present its arguments

against what the Court had in mind to do to it.

But even more objectionable than an injunction

without notice, hearing or jurisdiction, the District

Court's order also violated LDF's right to raise and to

spend money in support of civil rights litigation, a right

congruent with its First Amendment rights of free speech and

association and one that necessarily extends to successful

as well as to unsuccessful civil rights litigation.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Did the District Court's sua sponte injunction

violate due process by issuing without prior notice, a

hearing or personal jurisdiction over LDF?

2. Did the District Court have any legal basis for

entering an order interfering with the funding decisions of

LDF?

3. Did the District Court's sua sponte injunction

violate LDF's First Amendment rights of free speech and

association by restricting use of its financial resources in

support of civil rights litigation in the absence of a

compelling state interest?

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Nature of the Appeal

This appeal is from orders entered by the District

Court on December 28, 1987 and August 31, 1988 following the

trial of actions brought pursuant to Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. Sections 2000e, et. seq.,

alleging racial discrimination among the civilian work force

at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Although LDF was not a party or an intervenor in

the District Court, this Court, nonetheless, has

jurisdiction since LDF was the subject of, and hence was

aggrieved by, a District Court injunction. Commercial

Security Bank v. Walker Bank & Trust Co., 456 F.2d 1352

(10th Cir. 1972); 9 J. Moore Moore's Federal Practice

H 203.06 at 3-23 (2d ed. 1989); accord Zenith Radio Corp. v.

Hazeltine Research Inc., 395 U.S. 100, 89 S.Ct. 1562 (1969);

Warner Bros., Inc, v. Dae Rim Trading Inc., 877 F.2d 1120

(2d Cir. 1989); Kenny v. Quiqq, 820 F.2d 665 (4th Cir.

1987). This Court has appellate jurisdiction pursuant to

28 U.S.C. Sections 1291 and 1292(a)(1).

5

B. The Facts

LDF is a not-for-profit legal aid corporation

incorporated in 1940 pursuant to the laws of the State of

New York. LDF's purpose is to assist, and to provide

representation in, litigation challenging race

discrimination. The work of LDF is conducted by paid staff

attorneys augmented by attorneys in private practice working

in cooperation with LDF's staff. See National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People v. N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., 753 F.2d 131 (D.C. Cir.

1985), cert, denied, 472 U.S. 1021 (1985); Harris v. Marsh,

123 F.R.D. 204, 219 (E.D.N.C. 1988). These activities are

supported by funds solicited from public donors, foundations

and other funding sources and spent on the litigation and

related efforts LDF's staff and Board of Directors believe

will contribute to the objectives of combatting and reducing

race discrimination.

LDF is governed by a Board of Directors, drawn from

across the country, many of whose members are attorneys.

The Board establishes broad policy goals and priorities for

the organization. The Board of Directors employs a staff of

salaried attorneys who are led by the Director-Counsel.

While the Board of Directors possesses the ultimate

authority to determine which litigation LDF will support,

6

this authority is delegated to LDF's Director-Counsel and to

staff attorneys.

Pursuant to its general practice LDF does not

appear and did not appear in the Court below as a

corporation and did not sign pleadings. Generally LDF

litigates through its staff attorneys or associates with

attorneys admitted locally. In courts in which LDF staff

attorneys are not admitted, they participate in litigation

Pro hac vice. In many cases a LDF staff attorney serves as

lead counsel. In other cases such as this one, a LDF staff

attorney plays a limited role.

Julius L. Chambers, Esq., a subject of the District

Court's sanctions award, has worked over the years as a

cooperating attorney on cases with LDF. At the time this

Title VII litigation was filed against the United States

Army, Mr. Chambers was in private practice in North Carolina

in the firm of Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas & Adkins.

That firm served as lead counsel to the plaintiffs. In

July, 1984, Mr. Chambers left private practice to become

Director-Counsel of LDF. He withdrew as lead in-court

counsel in Harris v. Marsh in February, 1985, although his

former firm continued with the litigation.

LDF did not appear as a corporation in the Court

below and, during the course of Harris v. Marsh,

Mr. Chambers did not appear on behalf of LDF but appeared

7

through his own firm and on behalf of plaintiffs. LDF

Par"ticipated at trial only through the limited work of a

part-time staff attorney, Penda D. Hair, Esq. from July,

1983 until March, 1984. See 123 F.R.D. at 219. The Court

below described Ms. Hair's work as "extremely limited and

episodic," involving "only relatively minor and defined

tasks." "She possessed no decision-making authority or

responsibility for the day-to-day management of the case."

123 F.R.D. at 219. Another staff attorney, Gail Wright,

Esq., attended the sanction hearings.

During the complex and protracted Title VII

litigation behind this appeal, LDF was never served with any

pleading joining it as a party and certainly with none

indicating that it might be the subject of restrictive

injunctive relief. Despite Appellee's efforts to obtain

sanctions from numerous litigants and attorneys on a wide

variety of claims, no one below ever requested that LDF be

sanctioned or that its activities be subject to any

restrictions and the Court made no finding against LDF of

any misconduct. Thus, the District Court's sua sponte

injunctions were preceded by none of the procedural

safeguards normally afforded litigants by the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure (see e.g., Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. P.) and

by due process.

8

The District Court's sua sponte injunction is

especially unsupportable because it was, at least in the

Court's view, intended to protect, not to punish LDF and its

contributors. In justifying its restrictions, the Court

below acknowledged the NAACP's (sic) "historic mission" and

that it "has contributed substantially to the racial

progress of this country." The restrictions were, according

to the Court, imposed "to serve this vital purpose" since

"the court does not propose to see any money diverted from

its crucial mission." 679 F. Supp. at 1392 n.280. In other

words, the only compelling interest that animated the

District Court was the protection of LDF and its

contributors. But this is simply not a constitutionally

acceptable justification for an interference with LDF's

rights of free expression and association.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Without notice or an opportunity to be heard and

without obtaining personal jurisdiction over LDF, the

District Court sua sponte enjoined LDF from reimbursing any

of the sanctions it imposed. An injunction issued under

such circumstances violates due process as well as numerous

other Rules of Civil Procedure. In addition, LDF's

decisions regarding the allocation of resources in support

9

of civil rights activities are protected by First Amendment

rights of free speech and association. The District Court's

substitution of its judgment for that of LDF on the question

of how best to further civil rights and to protect LDF and

its contributors was highly inappropriate and, we

respectfully submit, comes nowhere near the furtherance of

some compelling government interest, the only basis on which

LDF's First Amendment rights could properly have been

abridged.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE DISTRICT COURT VIOLATED DUE

PROCESS BY ENJOINING LDF WITHOUT PRIOR

NOTICE, A HEARING OR PERSONAL JURISDICTION.

A. LDF received no notice or hearing

regarding the court order barring

contributions to the sanctions award.

The District Court's orders were tantamount to

injunctions issued in the complete absence of normal

procedural safeguards. See Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. P. As is

shown below, the injunctions invaded LDF's First Amendment

rights and . . a first amendment interest undoubtedly

qualifies as liberty which may not be denied without due

process of law under the fifth amendment." Sherrill v.

Knight, 569 F.2d 124, 130-131 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

10

Prior notice and opportunity for a hearing are, of

course, the cornerstones of due process. Notice is an

"elementary and fundamental requirement of due process in

any proceeding which is to be accorded finality" and must be

"reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to

apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and

afford them an opportunity to present their objections."

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Div. v. Craft, 436 U.S. 1, 13, 98

S.Ct. 1554, 1562 (1978). Similarly, an opportunity for a

hearing is a "fundamental requisite of due process."

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 267, 90 S.Ct. 1011, 1020

(1970). See also Kulko v. Superior Court of California,

436 U.S. 84, 98 S.Ct. 1690, reh*q denied, 438 U.S. 908

(1978). Without providing notice and an opportunity for a

hearing, a court cannot bind an entity by its judgment.

McKinney v. Alabama, 424 U.S. 669, 674, 96 S.Ct 1189, 1193

(1976). While the type of notice and hearing may vary

according to the circumstances, "at a minimum, due process

usually requires adequate notice of the charges and a fair

opportunity to meet them." Bowens v. N.C. Dep't. of Human

Resources, 710 F.2d 1015, 1019 (4th Cir. 1983).

The Court below ignored almost all of these basic

rules. Prior to entry of the December 28, 1987 and

August 31, 1988 orders, LDF received no notice that the

District Court contemplated restricting its organizational

11

activities and no party had requested such relief. The

status and organization of LDF, the nature of its

contributions and expenditures and the effect that

restrictions on them might have on the work of LDF were all

important questions that had not been raised or briefed by

any party and, hence, were not properly subject to decision

by the District Court. An injunction issued in this

context, especially one that implicates constitutionally

protected conduct, is, we respectfully submit,

impermissable.

B. The District Court did not have personal

jurisdiction over the Legal Defense Fund.

The Court below had no jurisdiction to enter an

order affecting the rights and obligations of LDF because

LDF was not a party to the action. As a non-party, LDF

could not properly be made subject to, or be bound by, the

District Court's order. As the Supreme Court has recently

stated:

[a]11 agree that it is a principle of general

application in anglo-American jurisprudence that

one is not bound by a judgment in personam in a

litigation in which he is not designated as a party

or to which he has not been made a party by service

of process. A judgment or decree among parties to

a lawsuit resolves issues as among them, but it

does not conclude the rights of strangers to those

proceedings.

12

Martin v. Wilks. __ U.S.___, 109 S.Ct. 2180, 2184, reh'g

denied, 58 U.S.L.W. 3120 (1989). See also Hansberry v. Lee,

311 U.S. 32, 61 S.Ct. 115 (1940); Zenith v . Hazeltine,

supra.

In a closely analogous case, the Second Circuit

held that a District Court could not require non-party

brokerage houses which had not appeared before the court to

send class notices at their own expense. In re Franklin

National Bank Securities Litigation, 574 F.2d 662, 665-666

(2d Cir. 1978). The Court held that because the District

Court lacked personal jurisdiction over the non-parties, it

could not enter an order affecting their rights and

obligations. Id.

Certainly, the fact that the Court sanctioned

Mr. Chambers who later became the employee of LDF did not

give the Court in personam jurisdiction over LDF, a foreign

corporation. See Martin v. Wilks supra; Zenith v.

Hazeltine, supra; Hansberry v. Lee, supra. Jurisdiction

over LDF could conceivably have been achieved by the service

of some process on LDF pursuant to Rule 4, Fed. R. Civ. P.

See Rule 19, Fed. R. Civ. P. Had proper process issued, LDF

might then have been brought before the Court where

restrictions on its First Amendment rights could have been

litigated. That, of course, did not happen. Nothing in

LDF's relationship to the litigation provided any

13

justification for the circumvention of the usual rules for

making a foreign corporation a party to a legal proceeding.

See Zenith v. Hazeltine, supra; Hansberry v. Lee, supra;

Hutchinson v. United States, 677 F.2d 1322 (9th Cir. 1982).

II.

THE DISTRICT COURT HAD NO

LEGAL BASIS FOR AN ORDER AGAINST LDF.

It is undisputed that the District Court made no

finding that LDF did anything wrong. There was no claim or

finding that LDF violated Rule 11, Rule 16 or any other

applicable stricture. In the absence of such a violation

there was no basis for an order limiting LDF's freedom to

pursue its objectives. Indeed there is no subject matter

jurisdiction over LDF. See 28 U.S.C. Sections 1331 and

1332; Dracos v. Hellenic Lines Limited, 705 F.2d 1392 (4th

Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 474 U.S. 945 (1985).

There is nothing in LDF's relationship to the

parties in the proceeding below which provides any legal

basis for an ex parte order dictating how LDF can spend its

money. Nothing in the proceedings below justifies an order

invading Mr. Chambers' financial relationship with his

employer. His compensation is a private matter outside the

purview of the District Court's Rule 11 authority. If

Mr. Chambers is to ultimately pay the sanctions, he must get

the money somewhere. No legal basis exists for a ruling

14

preventing him from getting it from LDF which is both his

employer and an organization dedicated to supporting both

successful and frustrated civil rights lawyers.

We can imagine no rational basis for an order

forbidding a political or fraternal group, or some other

civil rights group or a private individual from contributing

to the sanctions as an expression of political or otherwise

protected views. We suggest that there is nothing in LDF's

relations with the parties or the Court which would give it

any more authority to regulate LDF's contributions to the

parties than the Court would have in the event any of these

other entities sought to make contributions under such

circumstances.

The District Court's order cannot be upheld on the

ground that it seeks to prevent LDF's charitable resources

from being used to pay sanctions for which LDF was not

liable. It is the right of LDF's Board of Directors to

determine the proper allocation of its resources — within

its corporate purposes — and it was a clear usurpation of

that authority for the District Court to override the LDF

Board's choice about how best to support civil rights

activities.

Neither can the order be justified by an argument

that the Harris case is not a meritorious civil rights case.

Whatever the weight of the District Court's findings on the

15

merits of the Harris case, it simply has no right to prevent

LDF from expressing disagreement with those findings. If

LDF's governing body concludes that the District Judge is

wrong for some reason, or that his sanctions against the

clients or lawyers were an improper over-reaction to

difficult civil rights advocacy, the LDF Board has the right

to spend its money in support of these conclusions. That is

the essence of constitutionally protected speech and

association and is something uniquely ill-suited to judicial

second-guessing.

III.

BY INTERFERING WITH LDF'S DECISIONS

REGARDING ALLOCATION OF ITS RESOURCES

IN SUPPORT OF CIVIL RIGHTS LITIGATION,

THE DISTRICT COURT VIOLATED LDF's FIRST

AMENDMENT RIGHTS OF FREE SPEECH AND ASSOCIATION.

A. LDF's right to contribute to the

sanctions award is an activity

protected by the First Amendment.

The United States Supreme Court has long recognized

that civil rights litigation is protected by the First

Amendment and cannot be regulated except perhaps to serve a

compelling government need, and only then if the regulation

is narrowly tailored.

In 1963, the Supreme Court held that NAACP

activities in counseling litigants and referring them to

NAACP attorneys for the purpose of instituting desegregation

16

suits were protected by the First Amendment. National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 83 S.Ct. 328 (1963). The Court explained

that:

In the context of NAACP objectives, litigation is

not a technique of resolving private differences;

it is a means for achieving the lawful objectives

of equality of treatment by all government,

federal, state and local for the members of the

Negro community in this country. It is thus a form of political expression.

371 U.S. at 429, 83 S.Ct. at 336.

Rejecting the claimed need to enjoin the NAACP's

activities because of the state's interest in prohibiting

solicitation of clients, the Supreme Court emphasized that

"a state may not, under the guise of prohibiting

professional misconduct, ignore constitutional rights.'' Id.

371 U.S. at 439, 83 S. Ct. at 341. Because Virginia had not

shown a compelling interest in regulating the NAACP's

litigation activities, the Court held that the statute

unconstitutionally interfered with the NAACP's freedom of

expression and freedom of association. Id. See generally

Louisiana v. NAACP. 366 U.S. 293, 81 S.Ct. 1333 (1961);

NAACP V. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 78 S.Ct. 1163 (1958).

In numerous cases since then the Supreme Court, as

well as lower courts, have applied this principle. Thus,

First Amendment protection includes a union's right to have

its legal department advise employees and their families and

17

refer them to competent counsel. Brotherhood of Railroad

Trainmen v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1, 84 S.Ct. 1113, reh'q

denied, 377 U.S. 960 (1964). Similarly, this First

Amendment right extends to a union employing a salaried

attorney to assist members with compensation claims. United

Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar

Association. 389 U.S. 217, 88 S.Ct. 353 (1967).

The Supreme Court has emphasized that "collective

activity undertaken to obtain meaningful access to the

courts is a fundamental right within the protection of the

First Amendment." United States Transportation Union v.

State Bar of Michigan. 401 U.S. 576, 585, 91 S.Ct. 1076,

1082 (1971). Such First Amendment protection also includes

soliciting a party as a plaintiff in public interest

litigation for the purpose of vindicating that party's

rights. In re Primus. 436 U.S. 412, 426, 98 S.Ct. 1893,

1901 (1978). See Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S.

350, 376, 97 S.Ct. 2691, 2705, reh'q denied, 434 U.S. 881

(1977) .

Lower courts have reached similar conclusions. In

American Civil Liberties Union v. Tennessee, 496 F. Supp.

218 (M.D. Tenn. 1980), the court rejected a challenge to a

public interest litigation group's funding of litigation

based upon a claimed paramount state interest in preventing

18

barratry and held that the group's funding activities were

protected by the First Amendment. Id. at 222.

Similarly, in Eilers v. Palmer, 575 F.Supp. 1259,

1261 (D. Minn. 1984), the court rejected attempts to

discover the identity of parties funding litigation holding

that financial support of litigation is a "form of

expression and association protected by the First

Amendment." The Eilers court further emphasized that any

restrictions on these protected activities are subject to

close scrutiny. Id.

A constitutionally protected right to support civil

rights litigation means a right to spend money on it. If

the right exists, how it is best exercised is a

determination for the LDF Board, not the Court, and

certainly not through a sua sponte, ex parte order. No one

could seriously argue that Judge Fox could have barred LDF

from properly spending its money on legal research, court

reporter bills, salaries or expert witness fees in a civil

rights case. Where the First Amendment is implicated,

spending money on sanctions is analytically no different

from spending money in any of these other areas.

Unless the District Court's order is reversed, it

will undoubtedly chill participation in future civil rights

litigation, much of which has become complex, expensive,

technical and beyond the reach of many practitioners. To

19

continue effectively to support litigation, LDF must be able

to offer and deliver assistance to civil rights attorneys

not only when they win, but also when they lose. If a

constitutional right to financially support litigation does

not apply when civil rights attorneys are unsuccessful or

when, as here, a court concludes that a case was mishandled,

then the right has disappeared.

B. No restriction on the exercise of

First Amendment rights is constitutional

unless it is necessary to serve

a compelling governmental interest._____

Even if some restriction on LDF's First Amendment

activities were permissible — a proposition we deny — in

order to pass constitutional muster, any such regulation

must serve a compelling government interest. See Roberts v.

United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 104 S.Ct. 3244 (1984);

Louisiana v. NAACP, supra; Button, supra.

The sole rationale articulated by the Court below

for its restrictions was the protection of LDF's

contributors. Significantly, the District Court did not

suggest that LDF was barred from reimbursing sanctions

because of some interest in imposing the entire obligation

upon the individual attorneys. On the contrary, the Court

expressly provided that the firms of the sanctioned

attorneys could contribute a portion of the award. Harris,

679 F. Supp. at 1392; Harris, 123 F.R.D. at 228. Having

20

determined that the attorneys would not be required to bear

the entire sanctions award, the District Court

unquestionably had no compelling interest in prohibiting LDF

from reimbursing any of it.

By any calculus, the lower Court's paternalistic

concern for LDF's contributors is not a compelling interest.

LDF has a large and responsible Board that is fully able to

protect the corporation and to make informed decisions about

the allocation of its resources. Abridging LDF's First

Amendment rights is no way to protect those rights.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the District Court's

orders barring LDF from reimbursing the sanctions it imposed

should be reversed.

Dated: New York, New York

October 16, 1989

Respectfully submitted

MORRISON & FOERSTER

By:

Jr.

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10104

(212) 468-8000

Attorneys for Appellant

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

N22955

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that two true and correct copies of the

foregoing BRIEF OF APPELLANT NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. were served by first class mail,

postage pre-paid, on October 16, 1989, on the following

individuals:

Geraldine Sumpter, Esq.

Ferguson, Stein, Watt,

Wallas & Adkins, P.A.

Suite 730

700 East Stonewall Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Bonnie Kayatta-Steingart, Esq.

Fried, Frank, Harris, Schriver

& Jacobson

One New York Plaza

New York, New York 10004-1980

Prof. George Cochran

Law Center

University of Mississippi

University, Mississippi 38677

William C. McNeil, III, Esq.

Employment Law Center

Suite 400

1663 Mission Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Cressie Thigpen, Esq.

Thigpen, Blue, Stephens

and Fellers

205 Fayetteville Street Mall Suite 300

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Sidney S. Rosdeitcher, Esq.

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton

& Garrison

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

Robert S. Greenspan, Esq.

Thomas M. Bondy, Esq.

U.S. Department of Justice

Civil Division, Appellate Staff Room 3617

Washington, D.C. 20530

Dated: New York, New York

October 16, 1989

i7" p.

Barrington D. Parker, Jr.