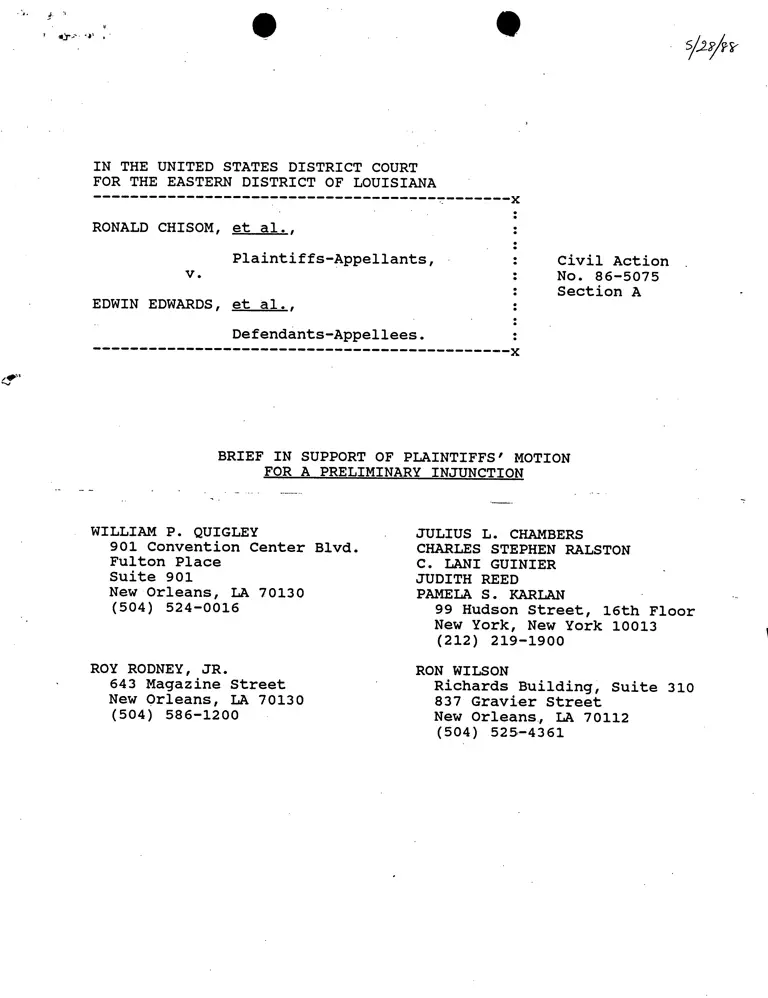

Brief in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for a Preliminary Injunction

Public Court Documents

June 14, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Brief in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, 1988. 9045b842-f211-ef11-9f89-0022482f7547. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/68ca5a0f-2dfa-4654-bf0b-95b57e545b71/brief-in-support-of-plaintiffs-motion-for-a-preliminary-injunction. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

•

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Civil Action

No. 86-5075

Section A

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS' MOTION

FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 901

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

JUDITH REED

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ii

Introduction 1

The Procedural History of this Case 1

Argument 4 -

I. Plaintiffs Are Entitled to a Preliminary Injunction. 4

A. Plaintiffs Are Likely to Succeed on the Merits .5

1. The Appropriate Legal Standard 5

2. The Evidence in this Case 7

a. The Lack of Minority Electoral Success. . 7

b. Racially Polarized Voting 8

c. Evidence Concerning Other Senate

Factors 11

d. The Three-Pronged Gingles Test 14

B. Plaintiffs Face a Substantial Threat of

Irreparable Injury 15

C. The State Will Suffer No Injury If the Upcoming

Election Is Postponed 19

D. The Public Interest Would Best Be Served By

Enjoining the Upcoming Election 20

II. The Possibility of a Petition for Certiorari Should

Not Deter This Court from Imposing a Preliminary

Injunction 22

Conclusion 24

Certificate of Service 25

Appendix 27

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972) 18

Canal Authority v. Callaway, 489 F.2d 567 (5th

Cir. 1974) 4

Chisom V. Edwards, F.2d (5th Cir.

May 27, 1988) 3

Chisom V. Edwards, 831 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988) . 2, 5, 7, 15,

20, 22

Citizens for a Better Gretna V. City of Gretna,

636 F. Supp. 1113 (E.D. La. 1986), aff'd,

834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987) . . . . ....... 8, 9, 12

City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975) . 19, 22,

23

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) 14

Cook v. Luckett, 575 F. Supp. 479 (S.D. Miss. 1983) . 16, 20

Cosner V. Dalton, 522 F. Supp. 350 (E.D. Va. 1981)

(three-judge court) 20

Deerfield Medical Center v. City of Deerfield

Beach, 661 F.2d 328 (5th Cir. 1981) 15

Elrod V. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976) 16

Haith V. Martin, 477 U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559

(1986) 22

Hamer V. Campbell, 358 F.2d 215 (5th Cir. 1966) 3, 21

Harris v. Graddick, 593 F. Supp. 128 (M.D. Ala.

1984) 16

Hendrix V. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626 (M.D. Ala.

1978) 8

Herron V. Koch, 523 F. Supp. 167 (E.D.N.Y. 1981)

(three-judge court) 22

Johnson v. Halifax County, 594 F. Supp. 161

(E.D.N.C. 1984) 4, 17

11.

Kirksey V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss. 1986)

(three-judge court) 19

Kirksey v. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J85-0960(B)

(S.D. Miss. May 28, 1986) 4, 6, 17-19

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) 12

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983)

(three-judge court) 7, 9, 12, 14, 21

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988) 22

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D.

Miss. 1987) 19

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037

(11th Cir. 1984) 8

Middleton-Keirn v. Stone, 655 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1981) . 16

Mississippi State Chapter, Operation PUSH

V. Allain, 674 F. Supp. 1245 (N.D.

Miss. 1987) 13

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) 16

Smith v. Paris, 386 F.2d 979-(5th Cir. 1967)

(per curiam) 20, 21

South Carolina v. United States, 585 F. Supp. 418

(D.D.C.) (three-judge court), appeal dism'd,

469 U.S. 875 (1984) 18

Taylor v. Haywood County, Tennessee, 544 F. Supp.

1122 (W.D. Tenn. 1982) 4, 17

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d

25 (1986) 5, 6, 10, 14, 15

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979) 11

Valteau v. Edwards, 466 U.S. 909 (1984) 18

Valteau v. Edwards, Civ. Act. No. 84-1293 (E. D.

La. Mar. 21, 1984) (three-judge court) • 19

Watson v. Commissioners Court of Harrison

County, 616 F.2d 105, 107 (5th Cir.

1980) (per curiam) 16, 21

Yick Wo. V. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) 16

iii

Zimmer v. McKeithan, 485 F.2d 1297, 1306 (5th Cir.

1974) (en banc), aff'd on other grounds sub

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam) 12, 13

Legislative History

128 Cong. Rec. S6716, 6718 (daily ed. June 14, 1982) 23

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227 (1982) 14

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982) 5, 6, 13, 14

Other

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After (1975) 14

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Civil Action

No. 86-5075

Section A

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR

SUMMARY JUDGMENT OR, IN THE ALTERNATIVE

FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Introduction

Plaintiffs Ronald Chisom et al., black registered voters in

Orleans Parish, Louisiana, have moved for a preliminary

_

injunction restraining defendants (hereafter "the State") from

conducting any elections to fill positions on the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First Supreme Court Judicial District

until the disposition of plaintiffs' challenge to the current use

of a multimember election district. 1

The Procedural History of this Case

The Louisiana Supreme Court consists of seven justices.

Five are elected from single-member districts. The other two are

elected from the only multimember district--the First Supreme

1 Plaintiffs have challenged the present election scheme

under both section 2 of the Voting Rights Act •of 1965 as amended

in 1982, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the Constitution. They seek a preliminary

injunction on only their section 2 results claim.

Court District. The First District contains Orleans, St.

Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson Parishes. Justices serve

ten-year terms. One of the two justiceships allocated to the

First Supreme Court District--the one now held by Justice

Calogero--is scheduled to be filled by election in the fall of

1988; the other seat--the one now held by Justice Marcus--is to

be filled by election in the fall of 1990.

On September 19, 1986, two years before the first scheduled

election, plaintiffs filed a complaint in this Court. It

challenged the use of an election scheme that submerged Orleans

Parish's predominantly black electorate in a majority-white

multimember district under both the "results" prong of section 2

and the intent standard of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. In an opinion and order dated May 1, 1987, and

subsequently amended on July 10, 1987, this Court granted the

State's motion to dismiss plaintiffs' section 2 claims on the

ground that section 2 does not cover judicial elections.

On February 29, 1988, the Court of Appeals reversed

unanimously, holding both that section 2 applies to judicial

elections and that plaintiffs' complaint had adequately pleaded

its constitutional allegations. Chisom v. Edwards, 831 F.2d 1056

(5th Cir. 1988). The State petitioned for rehearing and

rehearing en banc. Plaintiffs responded by moving either for an

injunction against the upcoming election or for issuance of the

mandate to permit them to seek immediate preliminary injunctive

relief in this Court.

2

On May 27, 1988, the Court of Appeals unanimously denied the

State's petition for rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc. In addition', despite the State's announced intention to

petition for certiorari, see Opposition to Plaintiff-Appellants'

Motion for an Injunction Pending Appeal at 16, 30, and the

provisions of Fed. R. App. P. 41(a) and (b) that postpone

issuance of the mandate to allow parties seeking certiorari to

receive a stay, the Court of Appeals ordered the immediate

issuance of the mandate.

The same day, the panel issued an opinion denying

plaintiffs' motion for an injunction pending appeal "[i]n

accordance with Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a), which provides that an

injunction request must ordinarily be made in the district court

on first instance," 2 Chisom v. Edwards, F.2d (5th Cir.

May 27, 1988), slip op. at 1, and dismissing as moot plaintiffs'

motion for issuance of the mandate. In that opinion, the Court

stated that:

In the event the plaintiffs assert their injunction

request to the district court, whichever way the

district court rules, this Court notes that any

election held under an elections scheme which this

Court later finds to be unconstitutional or in

violation of the Voting Rights Act is subject to being

set aside and the office declared to be vacant. See

Hamer v. Campbell, 358 F.2d 215 (5th Cir. 1966).

Slip op. at 1-2.

2 At the time plaintiffs sought injunctive relief from

the Court of Appeals, they could not have sought such relief from

this Court since this case had been closed following the entry of

the Court's June 8, 1987, judgment. See Record Excerpts on

Appeal at 3.

Argument

I. Plaintiffs Are Entitled to a Preliminary Injunction

The test for whether this Court should issue a preliminary

injunction focuses on four issues: (1) whether plaintiffs are

likely to prevail on the merits; (2) whether there is a

substantial threat of irreparable injury; (3) whether the

threatened injury outweighs the threatened harm an injunction

might do to the defendant; and (4) whether granting an

injunction will serve the public interest. Canal Authority v.

Callaway, 489 F.2d 567, 572 (5th Cir. 1974).

In Kirksey V. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J85-0960(B) (S.D. Miss.

May 28, 1986), 3 Judge Barbour, applying the Callaway criteria,

enjoined judicial elections throughout the state of Mississippi

pending the adjudication of the plaintiffs' section 2 claims; see

also, e.g., Johnson V. Halifax County, 594 F. Supp. 161 (E.D.N.C.

1984) (granting preliminary injunction stopping elections for

county commission in face of section 2 challenge); Taylor v.

Haywood County, Tennessee, 544 F. Supp. 1122 (W.D. Tenn. 1982)

(granting preliminary injunction stopping elections for county

road commission in face of section 2 and constitutional

challenges).

3 A copy of the district court's unpublished order in

Kirksey is attached to this Brief as Appendix A.

4

A. Plaintiffs Are Likely To Succeed on the Merits

1. The Appropriate Legal Standard

In its unanimous opinion

judicial elections, the Court

its express terms, extends to

839 F.2d at 1060. One of the

of Appeals relied in reaching

holding that'section 2 applies to

of Appeals held that "section 2, by

state judicial elections." Chisom,

primary sources

this conclusion

history of the 1982 amendments to section 2.

The purpose of those 1982 amendments was

on which the Court

was the legislative

See id. at 1061-63.

to eliminate the

requirement that plaintiffs show that challenged voting practices

are the product of purposeful discrimination. Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 37, 42 (1986). The Senate

Report accompanying the 1982 amendments, which Gingles

characterized as an "authoritative source" for interpreting

section 2, Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 42 n. 7, listed nine "[t]ypical

factors" that can serve to show 'a violation of section 2's

"results test." S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 28 (1982) ["Senate

Report"]. 4

4 These factors are:

"1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political subdivision

that touched the right of the members of the minority

group to register, to vote, or otherwise to participate

in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of

the state or political subdivision is racially

polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political

subdivision has used unusually large election

districts, majority vote requirements, anti-single shot

provisions, or other voting practices or procedures

5

In cases challenging the use of at-large elections, "the

most important Senate Report factors . . are the 'extent to

which members of the minority group have been elected to public

office in the jurisdiction' and the 'extent to which voting in

the elections of the state or political subdivision is racially

polarized." Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 45, n. 15. The other

factors are "supportive of, but not essential to, a minority

voter's claim." Id.

In Kirksey v. Allain, the district court found that

plaintiffs had shown a likelihood of success on the merits

because

that may enhance the opportunity for discriMination

against the minority;

4. if there is a candidate slating_process,

whether the members of the minority group have been

denied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority

group in the state or political subdivision bear the

effects of discrimination in such areas as education,

employment and health, which hinder their ability to

participate effectively in the political process;

6. whether political campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority

group have been elected to public office in the

jurisdiction.

[8.] whether there is a significant lack of

responsiveness on the part of elected officials to the

particularized needs of the members of the minority

group.

[9.] whether the policy underlying the state or

political subdivision's use of such voting

qualification, prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice or procedure is tenuous."

S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp. 28-29 (1982). "[T]here is no requirement

that any particular number of factors be proved, or that a

majority of them point one way or the other." Id. at 29.

6

they will probably prove a history of past racial

discrimination in Mississippi . . . ; racially

polarized voting in Mississippi elections; socio-

economic disparities between black and white citizens

of Mississippi, with blacks being less affluent and

less well educated; a lack of prior electoral success

by black judicial candidates in contested elections;

and that at the trial on the merits the key issue will

be the continued use of multi-member districts.

Slip op. at 2-3.

In this case, the evidence concerning those same relevant

factors is undisputed. Indeed, much of the evidence is reflected

in the opinion of the 'three-judge district court in Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983). At the hearing before

Judge Collins on November 6, 1986, concerning attorneys' fees in

Major v. Treen, the State disputed plaintiffs' requested award on

the grounds that the Major plaintiffs should have sought summary

judgment rather than going to trial because the evidence in their

favor was so overwhelming. If that is so, then preliminary

relief is surely appropriate in this case, where the Court has

the advantage of being able to rely upon Major v. Treen's

findings, made after a trial on the merits involving essentially

the same parties.

2. The Evidence in this Case

a. The Lack of Minority Electoral Success

With regard to the first of the factors identified as

critical in Gingles, the evidence is undisputed and, as the Court

of Appeals observed, "particularly significant," Chisom, 839 F.2d

at 1058: "[N]o black person has ever been elected to the

7

Louisiana Supreme Court, either from the First Supreme Court

District or from any one of the other_five judicial districts."

Id.

Indeed, no black candidate has run. The affidavits of

Judges Ortique and Augustine attached to Plaintiffs' Motion for a

Preliminary Injunction explain why: the current configuration of

the First Supreme Court District denies black voters an

opportunity , to elect the candidate of their choice and thus

deters black candidates from running. In cases such as this one,

"the lack of black candidates is a likely result of a racially

discriminatory system." McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d

1037, 1045 (11th Cir. 1984). See, e.g., Citizens for a Better

Gretna V. City of Gretna, 636 F. Supp. 1113, 1119 (E.D. La. 1986)

("axiomatic" that when minorities are faced with dilutive

electoral structures "candidacy rates tend to drop'") (quoting

Minority Vote Dilution 15 (C. Davidson ed. 1984)), aff'd, 834

F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987); Hendrix V. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626,

631-32 (M.D. Ala. 1978), (fact of racial bloc voting, when

combined with at-large elections for county commission

"undoubtedly discourages black candidates because they face the

certain prospect of defeat").

b. Racially Polarized Voting

With regard to the second factor--the presence of racially

polarized voting--the evidence is also clear. Elections in the

parishes that constitute the current First Supreme Court

District, particularly judicial elections, are characterized by

8

racial bloc voting.

Major v. Treen struck down a congressional districting

scheme which diluted the strength of Orleans Parish's

predominantly black electorate by splitting that electorate in

half and submerging the two parts in majority-white suburban

congressional districts. The combined area of the two

congressional districts involved in Major v. Treen constituted

essentially the First Supreme Court District being challenged in

this case. See 574 F. Supp. at 328. The Court there found "a

substantial degree of racial polarization exhibited in the voting

patterns of Orleans Parish." Id. at 337. It also held that

voting preferences in the "adjacent suburban parishes, whose

recently enhanced populations can be partially ascribed to the

exodus from New Orleans of white families seeking to avoid court-

ordered desegregation of the city's public schools" made those

parishes even less receptive to black candidates. Id. at 339;

see also, e.g., Citizens for a Better Gretna, 636 F. Supp. at

1124-30 (finding racially polarized voting in Jefferson Parish

municipality).

Major v. Treen's finding of legally significant racial

polarization rested in significant part on the existence of

racial bloc voting in local judicial elections. The court

expressly relied on a regression analysis performed by

plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Gordon Henderson, which studied the

results of thirty-nine elections in Orleans Parish during the

period 1976 to 1982 in which black candidates ran. See 574 F.

9

Supp. at 337-38. Thirteen, or one-third, of these elections

involved judicial positions.

Racial bloc voting in judicial elections for positions on

lower courts within the First Supreme Court District continues to

this day. Dr. Richard L. Engstrom, a nationally recognized

expert in the quantitative analysis of racial voting patterns,

see Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 48 n. 20, 50 & 60 (citing Dr.

Engstrom's scholarly writings with approval), analyzed judicial

election contests involving black and white candidates during the

period 1978 to 1987 on behalf of the plaintiffs in Clark v.

Edwards, No. 86-435-A (M.D. La.), a case challenging the method

of electing Louisiana district court judges. Dr. Engstrom used

the analytic techniques--bivariate ecological regression and

extreme case analysis--approved by the Supreme Court in Gingles,

92 L.Ed.2d at 48. As part of his analysis, Dr. Engstrom analyzed

election returns from the geographic area relevant to this case

involving thirty-one black candidates in twenty-seven separate

contests. In twenty-five of twenty-seven races, a black

candidate was the preferred choice of black voters. 5 In no

election was a black candidate the choice of white voters. In

the twenty-five contests in which the black community supported a

black candidate, an average of 77.06 percent of the black

5 In twenty-three elections, a black candidate received

an outright majority of the votes cast by black voters. In the

other two--the Feb. 6, 1982, Orleans-Criminal I election and the

Sept. 29, 1984, Orleans Juvenile Court C, election--a black

candidate was the plurality choice.

10

electorate voted for the preferred black candidate, 6 while only

13.76 percent of white voters voted for the preferred black

candidate.

c. Evidence Concerning Other Senate Factors

This Court may take judicial notice of findings by other

courts and census data with regard to several of the other,

historical and socio-economic factors mentioned in the Senate

Report. Fed. R. Evid. 201; see United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443

U.S. 193, 198 n. 1 (1979) (findings of discrimination in craft

unions were so numerous as to be a proper subject for judicial

notice).

1. A history of official discrimination touching upon the

right to vote. --Louisiana's pervasive efforts to prevent blacks

from participating in the political process cannot seriously be

disputed. As Judge Politz, writing for the three-judge court in

Major v. Treen noted, from 1898 to 1965, the State used a variety

6 Four of these races involved more than one black

candidate. In the first (the Feb. 2, 1982 election for Orleans-

Criminal I), Julien was the plurality victor among black voters,

and 72.3 percent of black voters preferred one of the black

candidates. Julien subsequently received over 88 percent of the

black vote in the runoff. In the second (the Feb. 1, 1986

election for Orleans-Civil F), Magee was the choice of 75.3

percent of black voters, and 97.1 percent of black voters

preferred one of the black candidates. In the third (the Sept.

16, 1978, race for Orleans Parish Juvenile Court B), Douglas was

the choice of 57.1 percent of black voters, and 80.9 percent of

black voters preferred one of the black candidates. In the

fourth (the Sept. 24, 1984, election for Orleans Parish Juvenile

Court A), Gray received 68.9 percent of the black vote, and 88.6

percent of black voters preferred one of the black candidates.

Gray subsequently received 95.7 percent of the black vote in the

runoff.

11

of stratagems, including educational and property requirements

for voting, a "grandfather" clause, an "understanding" clause,

poll taxes, discriminatory purging procedures, an all-white

primary, a ban on single-shot voting, and a majority-vote

requirement to "suppres[s] black political involvement . • • .11

574 F. Supp. at 340; see also, e.g., Louisiana V. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965) (discussing Louisiana's long history of

racial discrimination in voting); Zimmer v. McKeithan, 485 F.2d

1297, 1306 (5th dr. 1974) (en banc), aff'd on other grounds sub

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636

(1976) (per curiam); Citizens for a Better Gretna, 636 F. Supp.

at 1116-17.

2. Socio-economic disparities--Both Major v. Treen and

Citizens for a Better Gretna recognized that the black citizens

of Orleans and Jefferson Parishes suffer from the effects of

discrimination in such areas as education and employment and that

their depressed socio-economic status hinders their ability to

participate effectively in the political process. See Citizens

for a Better Gretna, 636 F. Supp. at 1117; Major V. Treen, 574 F.

Supp. at 341.

Census figures for 1980 (the last year for which racial

breakdowns were compiled) show that while over 70 percent of the

•white adults (age 25 and over) in New Orleans are high school

graduates, less than half of the black adults are. Moreover, the

percentage of black adult residents who have completed fewer than

eight years of schooling (21.78) is nearly twice the percentage

12

of white residents with a similarly limited education.

According to the 1980 Census, black per capita income in

Orleans Parish was only 40 percent of white per capita income.

The percentage of black families living below poverty level

(33.4) was roughly four-and-one half times the percentage of

white families living below poverty level. And over twice the

percentage of black-occupied housing units as white-occupied

housing units lacked telephones and motor vehicles--two critical

resources for political mobilization, see, e.g., Mississippi

State Chapter, Operation PUSH v. Allain, 674 F. Supp. 1245, 1256

(N.D. Miss. 1987).

3. The presence of voting practices that enhance the

opportunity for racial discrimination. --All three practices

expressly identified by Congress as tending to exacerbate the

discriminatory impact of at-large elections, see Senate Report at

29, are present in this case. First, the First Supreme Court

District is an "unusually large election distric[t]," Id. It is

far larger in population than any other Louisiana Supreme Court

District. Moreover, it is the only multimember district, and

thus departs from the standard Supreme Court District, which

elects a single justice. Second, Louisiana has a majority-vote

requirement for judicial elections. See Zimmer, supra

(discussing majority vote requirement); Senate Report at 29.

This means that even if the majority white electorate were to

split its votes among several candidates, a black candidate would

not have the opportunity to win by a plurality. According to

13

Major v. Treen, this requirement "inhibits political

participation by black candidates and voters" and "substantially

diminishes the opportunity for black voters to elect the

candidate of their choice." 574 F. Supp. at 339. Third,

elections from the First Supreme Court District are subject to

the functional equivalent of an "anti-single shot" provision,

Senate Report at 29. Single-shot voting requires multi-position

races. See City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 184

(1980). But because the terms of the two justices from the First

Supreme Court District are staggered, only one seat is filled at

any election. Thus "the opportunity for single-shot voting will

never arise." Id. at 185 n. 21 (internal quotation marks

omitted; quoting U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After 208 (1975)); see also, e.g., H.R. Rep. No.

97-227, p. 18 (1982) (condemning staggered'terms).

d. The Three-Pronged Gingles Test

In Gingles, the Supreme Court used a three-pronged test for

assessing whether the choice of multimember, rather than single-

member, districts "impede[s] the ability of minority voters to

elect representatives of their choice." Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at

45:

First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate

that it is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single-member

district. . . . Second, the minority group must be able

to show it is politically cohesive. . . . Third, the

minority must be able to demonstrate that the white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it

14

. . . usually to defeat the minority's preferred

candidate.

Id. at 46, 47.

The second two prongs of this test ask, in essence, whether

voting is racially polarized. See Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 50.

For the reasons discussed above, plaintiffs satisfy these two

prongs.

With regard to the first prong, the evidence is also

undisputed. Over half the First Supreme Court District's

population lives in Orleans Parish, and, as of March 31, 1988,

slightly over 52 percent of the registered voters in Orleans

Parish were black. See Affidavit of Silas Lee, III. Judicial

districts are not required to comply with the requirement of one-

person, one-vote. See Chisom, 839 F.2d at 1060. Thus, there is

no -need--particularly in assessing whether plaintiffs have shown

a sufficient likelihood of success on the merits, as opposed to

actually imposing a remedial plan after a final determination of

section 2 liability--for this Court to address the precise

contours of a proper division of the present First Supreme Court

District.

B. Plaintiffs Face a Substantial Threat of Irreparable

Injury

The Court of Appeals has held that an injury is irreparable

"if it cannot be undone through monetary remedies." Deerfield

Medical Center v. City of Deerfield Beach, 661 F.2d 328, 338 (5th

Cir. 1981). The right at issue in this case is entirely

15

nonpecuniary, and no amount of financial compensation can redress

its deprivation.

The right to vote is the "fundamental political right,

because preservative of all rights." Yick Wo. V. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356, 370 (1886). That right "can be denied by a debasement

or dilution of the weight of a citizen's vote just as effectively

as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise."

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555 (1964).

The courts have long recognized that conducting elections

under systems that impermissibly dilute the voting strength of an

identifiable group works an irreparable injury on both that group

and the entire fabric of representative government. See, e.g.,

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. at 585; Watson v. Commissioners Court

of Harrison County, 616 F.2d 105, 107 (5th Cir. 1980) (per

curiam) (ordering district court to enjoin elections because

failure to do so would subject county residents to four more

years of government by an improperly elected body); Harris v.

Graddick, 593 F. Supp. 128 (M.D. Ala. 1984) (impediment to right

to vote "would by its nature be an irreparable injury"); Cook v.

Luckett, 575 F. Suppe 479, 484 (S.D. Miss. 1983) (noting the

"irreparable injury inherent in perpetuating voter dilution");

cf. Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 373 (1976) (denial of rights

under the First Amendment "unquestionably constitutes irreparable

injury"); Middleton-Keirn V. Stone, 655 F.2d 609, 611 (5th Cir.

1981) (irreparable injury to both black workers and Nation's

labor force as a whole is presumed in Title VII cases). And,

16

contrary to the State's suggestion in the Court of Appeals,

district courts have found a sufficient threat of irreparable

injury in cases in which a final determination of invalidity has

not yet been made. See, e.g., Kirksey v. Allain, slip op. at 3;

Johnson, 594 F. Supp. at 171; Taylor, 544 F. Supp. at 1134.

There is a substantial threat in this case of such a

dilution of black voting strength in the October 1, 1988,

election. First, the voting strength of Orleans Parish's

predominantly black electorate will be subsumed within the

larger, majority-white suburban electorate. See supra.

Second, as the affidavits of Judges Augustine and Ortique

show, the present election scheme will deter candidates who rely

primarily on the support of black voters from running. And those

candidates will be unable to obtain the financial backing

necessary for a credible candidacy as long as the present

district configuration continues. Thus, black voters will not

even have an equal opportunity to vote for candidates of their

choice, let alone the equal opportunity to elect such candidates

promised by section 2. If the Court does not grant preliminary

injunctive relief, the merits will not be determined in time for

the October 1, 1988, election, let alone far enough before the

election for potential candidates who enjoy the support of the

black community to meet filing requirements, raise sufficient

funds, and run serious campaigns.

Forcing candidates to expend considerable time, energy, and

resources campaigning in a district whose configuration violates

17

the Voting Rights Act both injures the candidates, see, e.g.,

South Carolina v. United States, 585 F. Supp. 418, 423 (D.D.C.)

(three-judge court), appeal dism'd, 469 U.S. 875 (1984), and

deprives the voters who support those candidates of their

fundamental constitutional right to a racially fair electoral

process. As the Supreme Court recognized in Bullock v. Carter,

405 U.S. 134, 143-44 (1972), the impact of placing heavy

financial burdens on candidates is closely "related to the

resources of the voters supporting a particular candidate," and

such burdens may therefore deny economically disadvantaged voters

the ability to support and elect the candidates of their choice.

In this case, allowing the elections to go forward will have one

of two results: (1) black candidates will once again be deterred

from running by both the cost of campaigning throughout the First

Supreme Court District and the virtual impossibility of winning

in the overwhelmingly white district,and black voters will once

again be deprived of the ability even to vote for a candidate of

their choice; or (2) if black candidates run, the resources

available from the black community to contest a special election

will be diminished by the expenditure of effort in an essentially

meaningless contest in 1988. See Kirksey v. Allain, slip op. at

3 (finding irreparable injury to plaintiff-intervenors--incumbent

judges--"should elections go forward, campaign expenses be

incurred, and such elections be nullified by subsequent order of

this court"). Indeed, in Valteau V. Edwards, 466 U.S. 909 (1984)

(denying application for stay), the State of Louisiana argued, in

18

seeking a stay of an order compelling it to hold a presidential

preferential primary, that it would "suffer irreparable harm" if

it were forced to expend approximately $2 million to conduct

elections whose results were later overturned. Application for

Stay at 5. 7

C. The State Will Suffer No Iniury If the Upcoming

Election Is Postponed

The State will not be adversely affected in any way if the

1988 election is postponed until the merits of plaintiffs' claims

are determined. Such a postponement would continue the terms of

the two sitting justices from the First Supreme Court District.

Cf. City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 365 (1975)

(city council elected in 1970 remained in office until 1975

during pendency of Voting Rights Act challenge to annexations);

Kirksey v. Allain, supra; 8 Kirksey V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347

7 Valteau involved a challenge, under section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act, to Louisiana's attempt to suspend the

operation of its presidential primary in 1984 and to have

political parties select delegates to their national conventions

through• caucuses instead. The district court entered an

injunction requiring the State to conduct a primary. Valteau v.

Edwards, Civ. Act. No. 84-1293 (E.D. La. Mar. 21, 1984) (three-

judge court). The State sought a stay of the district court's

order from the Supreme Court, arguing that it was possible that

the Department of Justice would preclear the switch to caucuses

thus rendering the results of the primary nugatory.

8 Subsequently, in Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183

(S.D. Miss. 1987) (Kirksey was consolidated with Martin, a case

challenging judicial elections in districts containing Hinds

County), the district court found that Mississippi's use of

multi-member, numbered post judicial districts in certain parts

of the state violated section 2. At the present time, remedy

proceedings are underway, and judicial elections in the affected

districts have been postponed for the past two years.

19

(S.D. Miss. 1986) (three-judge court) (enjoining judicial

elections for unprecleared jurisdictions). Thus, the Louisiana

Supreme Court will be able to continue its work unaffected.

The only potential injury defendants might suffer is the

expense of conducting a special election, should the district

court ultimately conclude that such an election is required. See

Cook, 575 F. Supp. at 485. It is entirely possible, however,

that any future election*to fill seats on the Supreme Court can

be coordinated with regularly scheduled elections, and such

expense avoided entirely. See, e.g., Smith V. Paris, 386 F.2d

979 (5th Cir. 1967) (per curiam) (shortening terms of officials

elected under discriminatory at-large scheme so that new

elections would coincide with next regularly scheduled

elections); Cosner v. Dalton, 522 F. Supp. 350, 364 (E.D. Va.

1981) (three-judge court) (shortening terms of state legislators

elected under invalid apportionment scheme). Moreover, that

injury is entirely counterbalanced by the danger of additional

expense in conducting a special election should the current

election proceed and plaintiffs then establish liability.

D. The Public Interest Would Best Be Served By

Enjoining the Upcoming Election

The public interest in a racially fair election scheme is

absolutely fundamental. "The right to vote, the right to an

effective voice in our society cannot be impaired on the basis of

race in any instance wherein the will of the majority is

expressed by popular vote." Chisom, 831 F.2d at 1065.

20

Because plaintiffs sought relief over two years before the

scheduled election, if this Court denies an injunction pending

appeal and plaintiffs ultimately prevail on the merits, the

results of the upcoming election will have to be set aside as the

Court of Appeals recognized in its per curiam opinion of May 27,

1988. Slip op. at 1, citing Hamer v. Campbell, suDra. A justice

elected in 1988 pursuant to an election system that dilutes black

political power cannot be permitted to serve for 10 years, until

1998 when the term would normally expire. See, e.g., Watson, 616

F.2d at 107 (service for another four years too long); Smith v.

Paris, 386 F.2d at 980 (ordering special election at next

regularly scheduled election, in two years); Hamer v. Campbell,

358 F.2d at 222 (service for another four years too long). And

the public interest in having a judiciary free from racial

discrimination in its selection is obviously of the highest

importance, as the Court of Appeals decision in Chisom

recognized.

In light of plaintiffs' likely success on the merits, the

public interest would best be served in not conducting an

election in 1988. First, such an election would likely have to

be repeated in two years. This possibility might dampen interest

both in seeking office and in voting and might decrease financial

support for candidates. Second, given the probable illegitimacy

of the present system, it would be unfair for a candidate to run

under the present scheme and thereby have an unfair advantage as

an incumbent only two years later. Cf. Major v. Treen, 574 F.

21

Supp. at 355. Third, the qualities of deliberation and non-

politicization that the decade-long term of office now serves

might be undermined by creating, in essence, a two-year term.

II. The Possibility of a Petition for Certiorari Should Not

Deter This Court from Imposing a Preliminary Injunction

This Court should not decline to order preliminary

injunctive relief on the ground that the State is likely to seek

certiorari on the question whether section 2 applies to judicial

elections. See Opposition to Plaintiff-Appellants' Motion for an

Injunction Pending Appeal at 16, 30 (announcing intention to

petition for certiorari). Plaintiffs believe that a grant of

certiorari in this case is unlikely. Both Courts of Appeals to

have addressed the question have concluded that judicial

elections are covered by section 2. See Chisom; Mallory v.

Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988). Those decisions are

entirely consonant with the Supreme Court's decision in Haith v.

Martin, 477 U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986), that section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial elections. 9 Thus,

there is neither a conflict among the circuits, nor a conflict

with any Supreme Court precedent.

Nonetheless, the timing of the State's petition will result

in a substantial lapse of time before the Supreme Court disposes

of the petition. The State's petition is unlikely to be filed

9 And in fact, under section 5 courts have consistently

enjoined elections pending disposition of plaintiffs' challenges.

See, e.g., City of Richmond v. United States, supra; Herron v.

Koch, 523 F. Supp. 167 (E.D.N.Y. 1981) (three-judge court).

22

until at least the end of June. Given the manner in which the

Supreme Court schedules petitions for consideration at

Conference, it is unlikely, even if plaintiffs were to waive

their right to respond or to file an opposition long before their

30 days to reply had run, that the case could be considered

before the Supreme Court recesses for the summer at the end of

June. Thus, the petition for certiorari will not be disposed of

before the first Monday in October, after the scheduled election.

In any event, the fact that a petition for certiorari is

pending, or even has been granted, does not affect the need to

preserve the status quo pending resolution of the question

whether conducting the upcoming election using the current First

Supreme Court District violates section 2. Cf. City of Richmond,

422 U.S. at 365 (keeping city council in office for five years

pending decision on legality of new election scheme).

The Court of Appeals' decision to issue the mandate

immediately, thus preventing the State from obtaining an

automatic stay of the mandate until the Supreme Court rules,

strongly suggests that it did not intend for this Court to let

the pendency, intended or actual, of a petition for certiorari

deter it from addressing the merits of plaintiffs' request for

injunctive relief.

No public interest could be more important than the

eradication of racial discrimination that impairs the right to

23

vote. 1° Thus, plaintiffs have satisfied all four prongs of the

test for a preliminary injunction and this Court should therefore

order the postponement of the upcoming elections.

Conclusion

Two years ago, plaintiffs filed a lawsuit challenging the

method of electing justices from the First Supreme Court District

in the hope that by 1988 a fair election system would be in

place. They now face the threat that once again their voices

will not be heard equally in the election process. Accordingly,

they ask this Court to provide them with preliminary relief.

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 901

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

Dated: June 14, 1988

tfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

JUDITH REED

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

Counsel for Plaintiffs

10 See 128 Cong. Rec. S6716, 6718 (daily ed. June 14,

1982) (remarks of Sen. Moynihan) (Voting Right Act is intended

"to reaffirm this Nation's commitment to that most basic and

fundamental guarantee . . . which is the right of every citizen

to exercise his or her right to vote for those who would

represent them in 'Government").

24

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on June 14, 1988, I served copies of

the foregoing brief upon the attorneys listed below via United

States mail, first class, postage prepaid:

William J. Guste, Jr., Esq.

Atty. General

La. Dept. of Justice

234 Loyola Ave., Suite 700

New Orleans, LA 70112-2096

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, LA 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Robert G. Pugh

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

Robert Berman

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66128

Washington, D.C. 20035

Michael H. Rubin, Esq.

Rubin, Curry, Colvin & Joseph

Suite 1400

One American Place

Baton Rouge, LA 70825

25

•

Peter Butler

Butler, Heebe & Hirsch

712 American Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Charles A. Kronlage, Jr.

717 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

26

Counsel for Plaintiffs

APPENDIX

27

SOUMERN DisTRICT 0/-

FILED

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT OURT-

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MIS issiWY 28 1985

JACKSON DIVISION

HENRY KIRKSEY, et al.,

on behalf of themselves

and all others similarly

situated,

Plaintiffs,

NATHAN P. ADAMS, JR. AND

NAT W. BULLARD,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors,

CLARENCE A. PIERCE. CLERK

BY

DEPUTY

v. CIVIL ACTION NO. J85-0960(B)

WILLIAM A. ALLAIN, Governor of

Mississippi, et al.,

Defendants.

ORDER

This civil action came on for hearing on May 27,

1986, on the plaintiffs' Motion for A Temporary

Restraining Order and/or Preliminary and/or Permanent

Injunction which the court and the parties have treated as

a request for preliminary injunctive relief enjoining the

defendants from conducting any elections for the offices

of circuit judge in the State of Mississippi, chancery

judge in the State of Mississippi, and county judge in

only Harrison County, Hinds County, and Jackson County,

Mississippi, pending this court's trial and decision on

the merits of the plaintiffs' claims for relief under

•

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in

1982, 42 U.S.C. S 1973, 42 U.S.C. S 1983, and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution and the entry of a future order of the court

rescheduling such elections.

Having considered the motion, the supporting and

opposing briefs, the documentary evidence received into

evidence at the hearing, and the four well-established

prerequisites for the granting of a preliminary

injunction, see, e.g., Canal Authority v. Callaway, 489

F.2d 567, 572-77 (5th Cir. 1974), the court rendered

bench opinion at the conclusion of the hearing in which it

stated its findings - f fact and conclusions- of law

required by Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a). For the reasons stated

in that bench opinion, the court hereby rules that

plaintiffs have satisfied the conditions for a preliminary

injunction:

1. Plaintiffs have shown a likelihood of success on

the merits. In light of the exhibits presented to this

court, plaintiffs have shown that they will probably prove

a history of past racial discrimination in Mississippi

which has an effect upon the ability of black citizens of

Mississippi to elect judicial candidates of their choice;

racially polarized voting in Mississippi elections;

socio-economic disparities between black and white

citizens of Mississippi, with blacks being less affluent

and less well educated; a lack of prior electoral success

by black judicial candidates in contested elections; and

that at the trial on the merits the key issue will be the

continued use of multi-member districts. Plaintiffs have

therefore shown some probability of success on the

merits.

2. Irreparable injury will ensue to the black

plaintiff class should elections go forward and the

present electoral system ultimately be found in violation

of the rights protected by the Voting Rights Act and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. Additionally, irreparable injury will

befall plaintiff-intervenors, the incumbent Chancery Court

judges for the Ninth District, should elections go

forward, campaign expenses be incurred, and such elections

be nullified by subsequent order of this court.

3. The relative harm to plaintiffs from the denial

of an injunction will exceed the harm to defendants from

the granting of such an injunction. Defendants have

pointed to the risk of lower vote turnout should the

elections not be held as scheduled as the only

identifiable potential harm to the state defendants.

4. The public interest will best be served by the

granting of an injunction. In light of the order of April

3, 1986, by a three-judge' court in this matter enjoining

•-•

*1,

some of the judicial elections under Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S 1973c, the risk of

confusion to the voters of divergent election dates for

the challenged judgeships, the need to hold new elections

should plaintiffs prevail, and the possible preclusion of

special appointments of incumbent judges who were defeated

it the polls, this court finds that the best interests of

all concerned are met by entering the following

injunction.

Therefore, the court finds and concludes that the

plaintiffs' motion is meritorious and should be granted.

IT IS, THEREFORE, ORDERED AND ADJUDGED:

1. That, pending a final decision by this court in

this action and the entry of a future order of this court

scheduling elections for the affected judicial offices,

defendants William A. Allain, in his official capacity as

Governor of Mississippi and as a member of the State Board

of Election Commissioners; Edwin L. Pittman, in his

official capacity as the Attorney General of Mississippi

and as a member of the State Board of Election

Commissioners; Dick Molpus, in his official capacity as

Secretary of State of Mississippi and as a member of the

State Board of Election Commissioners; the Mississippi

State Board of Election Commissioners; the Democratic

\.

Party of the State of Mississippi State Executive

Committee; and the State of Mississippi Republican Party

State Executive Committee, and their officers, agents,

servants, employees, and attorneys (the defendants) are

hereby ENJOINED AND PROHIBITED from conducting any primary

election or general election in the State of Mississippi

for all circuit judge offices in the State of Mississippi,

all chancery judge offices in the State of Mississippi,

and the county court judge offices in Harrison, Hinds, and

Jackson Counties;

2. That, given the nearness of the June 3, 1986,

primary and the fact that ballots have been prepared for

the primary election which include the offices subject to

this injunction, the court hereby directs how the

defendants and all other election officials may comply

with the injunction contained in Paragraph 1 above:

A. That, in the event that any ballots have not been

finalized, the defendants and all other election officials

are directed to delete from any such ballot the offices

subject to the injunction contained in Paragraph 1 above;

B. That, in the event that ballots have been

prepared which include the offices subject to the

injunction contained in Paragraph 1, the defendants and

all other election . officials need not prepare new

ballots. However, the defendants and all other election

officials are hereby directed not to tabulate, total,

tally, recap, publish, disclose, reveal, or otherwise

disseminate any votes or the number of votes which may be

cast for the offices which are subject to this

injunction;

C. That, in those counties utilizing voting machines

which can "block out" from voting by the electors these

particular offices subject to this injunction, the

defendants and all other election officials are directed

to "block out" such offices; and

D. That, in those counties utilizing voting machines

which cannot mechanically "block out" selected offices on

the previously prepared ballot, the defendants and all

other election officials are enjoined not to publish,

disclose, reveal, or otherwise disseminate any totals or

tallies which may be automatically , recorded by such

machines for the particular offices which are subject to

this injunction;

3. That the defendant Secretary of State is hereby

directed to give. prompt telephonic notification to all

state and county Democratic and Republican Party Executive

Committees and all circuit clerks/county registrars of the

provisions of this injunction and the Secretary of State

shall follow-up on such telephonic notification by mailing

a written notice; and

4. That the injunction contained in

applies only to all

of Mississippi, all

of Mississippi, and

offices of circuit judge

offices of chancery judge

all county judge offices

this order

in the State

in the State

in Harrison,

Hinds, and Jackson Counties, Mississippi. This order does

not apply to any other offices which may be on the ballot

on June 3, 1986, or thereafter, and it specifically does

not apply to or affect the election of:

Supreme Court Justices;

County Judge in those counties which have

court and only one county judge: Adams, Bolivar,

DeSoto, Forrest, Jones, Lauderdale, Lee, Leflore,

a county

Coahoma,

Lowndes,

Madison, Pike, Rankin, Warren, Washington, and Yazoo

Counties;

Youth Court Judge in Clay County; or

Family Court Judge in Harrison County.

SO ORDERED AND ADJUDGED, on this, the

May, 1986.

AP ROVED AS TO

Carroll Rhodes

Attorney for Plaintiffs

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Samuel Issacharq.e

Attorneys for Praintiffs

day of

e hen J. irchma r

Deputy torney General

Attorney for State

Defendants

cpiqlgaLadaoi a' l

Hubbard T. Saunders, IV

Attorney for State

Defendants

A TRUE COPY, I HEREBY CERTIFY

Clarence A. Pierce, QLERK

— 7 — By:

••••=0 "

BMW Mak