Selected School Data (Detroit Public Schools) Plaintiffs Exhibit 91

Public Court Documents

March 5, 1971

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Selected School Data (Detroit Public Schools) Plaintiffs Exhibit 91, 1971. c878ca42-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/692c67f5-7b9b-45f2-a165-e2b0de560eae/selected-school-data-detroit-public-schools-plaintiffs-exhibit-91. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

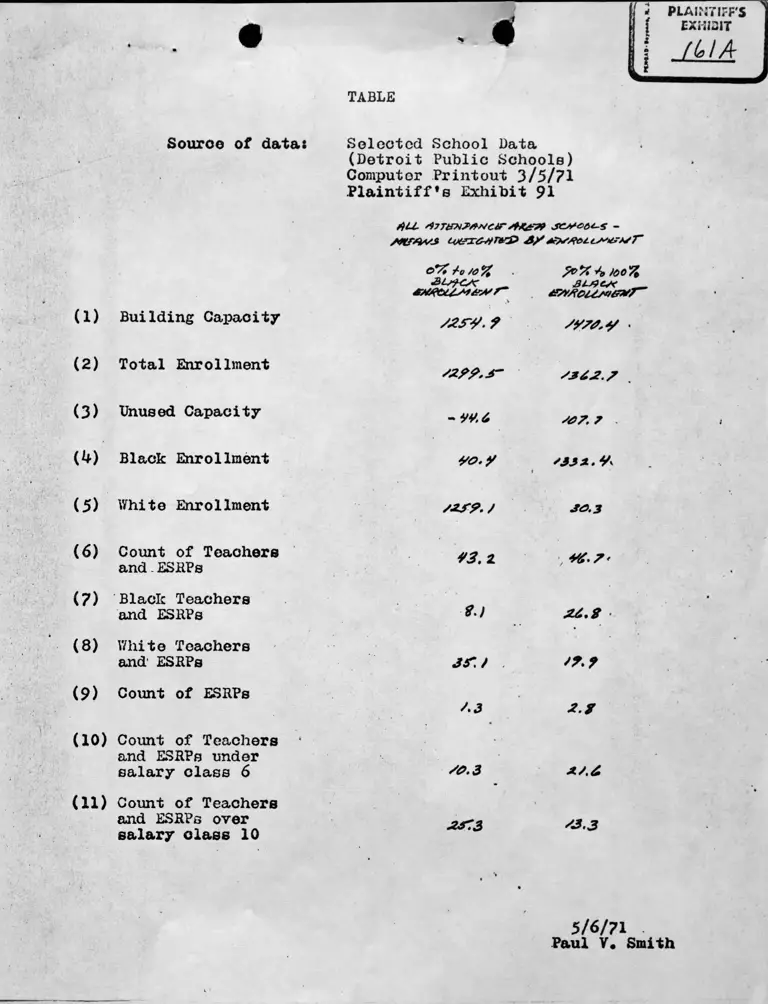

TABLE

2 PLAINTIFF'S

( EXHI31T

I CM

Vi—

Source of data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiffs Exhibit 91

4LL *7T&MJ>#*Cdr SCM66<-S -

o*7* /o /a %

TZOfCSC

\

£Ls?CS<

(1) Building Capacity s x r y . ? s y ? o , y •

(2) Total Enrollment s z ? ? . j r

(3) Unused Capacity - SO ?. 7 -

w Black Enrollment 9 0 . y '3 3 7 . y,

(5) White Enrollment JO . 3

(6) Count of Teaohers

and ESRPs 9 3 . 1 , 9 £ .7 <

(7) Black Teachers

and ESRPs X S . 3

(8) White Teachers

and ESRPs j< r ./

(9) Count of ESRPs

X *

(10) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs under

salary class 6 SO. 3

(11) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs over

salary class 10 JZJT73 S 3 .3

5/6/71Paul V. Smith

# . 4

TABLE

Souroe of data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff’s Exhibit 91

\ t

774T&7J k/£TJH*&f9 ^ 7 4 f& *0 ltA *£ » r

fcr* 0% /o 20/̂

w y o u sn rA /r

3o% /c ;o c%

SRVROtCfiUTMr

(1) Building Capaoity •

J 3 J 7 . / / y jr jr .y

(2) Total Enrollment S J T J .V 73*>3. 2 .

(3) Unused Capaoity - 3 6 . 3 7 7 2 .3

W Black Enrollment S 3 *7 . 31

(5) White Enrollment 7 2 7 9 .3

(6) Count of Teachers

and ES IIP s

(7) Black Teachers

and ESRPs 3 6 .2 .

(8) White Teachers

and ESRPs

■ v\ ^

3 7 .3 7 7 .7

(9) Count of ESRPs 7 .7 2 . 3

(10) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs under

salary class 6

* ■

7 0 ,7

(11) Count of Teaohors

and ESRPs over

salary olass 10

3 6 .6 7 3 . 9

516/71Paul V« Smith

4

TABLE

Souroe of data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff's Exhibit 91

AM. /97~r/rv&tosc£r s c m /o a s —

OO&MLL ***’T4*7*rX> & y :

SZVOOLS'

UHjrrtr

JC^OOJ.4*

ol tsotr*/7m2

(1) Building Capaoity / 3 3 3 .S ~ / y t * . /

(2) Total Enrollment 7 3 7 7 . X S 3 y

(3) Unused Capaoity - J Z 7 S i . 7

W Black Enrollment z r y . / 7 2 / 6 .4i

(5)

i

White Enrollment 7 4 7 7 . / A t ? . S

(6) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs & ./ * 7 .2

(7) Black Teachers

and ESRPs 7 4 .? * y j

(8) White Teachers

and ESEPs 3 S lX 2 2 . 9

(9) Count of ESRPs 7 4

(10) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs under

salary class 6 7 2 - 9 X / . 4

(11) Count of Teachers

and ESRPs over

salary olass 10

* 3 ? y y - 7

5/ 6/71Paul V* Smith

TABLE-

# 7 - PLAlM7t?f'S [ EXHIBIT

5 K ? £ A

Sourgo of Data: Selected School Data

(Dotroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71 Plaintiff's Exhibit 91

S/£'/?A'S 4/&r&#r£2> 3 / M£#7~

Number per 1000 total

students enrolled: .

"to SO ̂

&U9CK. •’

£/SKO LL/*£A/r

/#>%

$LACJ^

a)

%

Teachers and ESRPs 3 3 . 1 ' 3 S '. 3

(2) Black Teachers

and ESRPs 6. 2. 2.J.2

(3) V/hito Teachers

and'ESRPs JU.9 / * . /

•

(if) Teachers and ESRPs

under salary class 6 2 . Y

(5) Teachers and ESRPs

over salary class 10 / ? . 7 / o . t

•

(6) ESRPs j-i Z . 3

(7) Acres in sohool site 4 - 2 s T .J

5/ 6/ 71Paul V. Smith

TABLE

Source of Data: Selcctod School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff*s Exhibit 91

Number per 1000 total

students enrolled: .

(1) Teachers and ESRPs

(2) Black Teachers

and ESRPs

(3) White Teachers

and ESRPs

(̂ ) Teachers and ESRPs

under salary class 6

(5) Teachers and ESRPs

over salary class 10

(6) ESRPs

(7) Acres in sohool site

M & w s u>tf-rw r<rj> tr^ o c L ^ t^ r"

O *% to 16%

B L4C * •

3 o % to /# > %

8LAC.K

£XXOLXJ*i£Mr

■ 3 3 . 3 ' 3 3 7 2 .

7 f .O

47. o 7 7 . 2• i

2 .7 » 2

/ r .3 s & . y

A V 2 . 3

■ /.

j r . j

5/ 6/71Paul V* Smith

• #

TABLE-

PLAINTIFF'S }

EXHIBIT

— *- * -— ♦ i

I b H C

Souroo of Data; Seloctod School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71 Plaintiff’s Exhibit 91

j i t /?rr^ -W P M tr/r ‘r e b o o t s

Ai'/rW MS h/tnrM r< rJ> 3 / :

Number per 1000 total

students enrolled; .

f'CS/OOj.S J

h )» j'7 *r'

jsy to iL M & srs £?S/?oU AttzA/ry

(i) %Teachers and ESRPs ' . 33.6 ' 3*r, 0

(2) Black Teachers

and ESRPs ^•3 ; ? . z

(3) White Teachers

and ESRPs /s’. 9• *

W Teachers and ESRPs

undor salary class 6 /f-.s-

(5) Teachers and ESRPs

over salary olass 10 szy / / . /

(6) ESRPs

<

A S * 2 . 2 .

(7) Acres in sohool site * 7 " s r ./

5/ 6/71Paul V# Smith

s s *

TABLE

PLAINTIFFS

EXHIBIT

1 6 & A

Source of Data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Publio Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71 Plaintiff’s Exhibit 91

s?ll & spools -

Costs per Pupil: 0%8L#cJe h /oeZB09C./< 7~

(l) Teachers

'C . • . •

wz. >*r

(2) ESRPs ' '

i * ■

/ass A/.J?

(3) Teachers and ESRPs JZ2.03

. '

Average Annual Rate: ■ > •

w Teachers and

• ESRPs average annual salary /*, 4/ /// ess.jry

5/ 6/71Paul V. Smith

Source of Data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff's l$xhihit 91

4 I t A TTVM p/W C Jr fCSSOOl— S -

»

tuirx<£+>r*v> & /

Costs nor Pupil: o Z >/2o%

£*/?OLLM yy/r~

&o% h> Jt»%

J3L4CJK.

(1) Teachers

4 " 2 . 4 / 3 6 2 . 3 6

(2) ESRPs /4/z / 7 . ? 6

(3) Teachers and

ESRPs # 2 9 . r s 3 * 0 * 6 6

; •

Average Annual Date:

(̂ ) Teachers and

*.r

•. ESRPs average

annual salary ' /«, 4 * 3 . r a

5/ 6/71' Paul V* Smith

\

*

TABLE

i

ii

o

•i

U ? 3 ( L

PLAINTIFFS

EXHIBIT

Source of Datas Selooted Sohool Data

(Detroit Publio Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff*s Ĵ xhibit 91

ALL /?rray*p**J€ir/9/tdr/t jfc#*>oLS

^i/sn^AL u wrro-HTuD a y t

Costs per Pupils SCAtoOLS J J£Mooi.SJw loux 7tr su a c x

a)

J

Teachers

o t ie/isrj'

3 4 7 . 6 6

(2)

1 r

ESRPs S X . / S - sC . 7&

(3) . JTeachers and # * / . 6 0

• •

ESRPs j r t . 3 *

Aver acre Annual Bates «

(̂ ) Teaohers and • •

• ESRPs average

annual salary / Z jS S O ./ L / //, ay/. 2 #

t 5/6/71Paul V. Smith

A

TABLE

»

i

IF: J-L 1

PLAIMTIFF5

EXHID1T

l lo V f r

Source of Bata: Solocted School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiffs Exhibit 91

/le t. A rn--> jd F ^ c t r sW r* s p o o l s

B y eV tKO LU A W T

•

/Q/£

31j9Lf <

ie#A0U-M’Ur»fT$

9o 70 4o )00%

' hL*C.J<

a*/r o l l avt/j t s

(1) Enrollment y z p p . j r

t

7 3 6 Z . 7

(2) Teachers and ESRPs

per 1000 students

J

3 3 . i 3

(3) Pupil/Teacher Ratio

>

J a ^

\

W Average Teacher

and ESRP annual

salary

sz,rtf. o / / , o r f . j r v

(5) Teacher and ESRP

cost per pupil M 9 . 7/ 3 S X . O *

516/71

Paul V* Smith

TABLE

* PLAINTIFFS

( EXHIBIT

K d ^G>

Source of Bata: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71

Plaintiff's Exhibit 91

rfLL A-TTtrW&A/<U*' S C jic o L * '

//£WsVJ LO<sfG.»TG& & y £>/^PUS~Ur/*T~

(1) Enrollment

0 % 26%

2W40LL+'/ r —

S3?3. *

& o% t*» ibcY*

T~

' 3 * 3 . £

(2) Teachers and ESRPs

per 1000 students 33.3 33*, 2.

(3) Pupil/Teacher Ratio 30.2* A?. 3

w Average Teacher

and ESRP annual

salary

(5) Teacher and ESRP oost per pupil

22, 9/2, 9o // , 0 2 3 , 3 2

330, 06

5/ 6/71Paul V. Smith

/

(1)

(2)

(3)

W

(5)

# •

TABLE

d*

«l

S

a3 M L

PLAINTIFFS

EXHIBIT

Source of Data: Selected School Data

(Detroit Public Schools)

Computer Printout 3/5/71 Plaintifffs Exhibit 91

A LL /P7TWD&VC4C AKITA SCHOOLS

c u s k a l l By*

• SCHOOLS *

CVHXTtr

dHAOLLHHkmA/rmS

Sc h o o le *

OLfCSK.

S h Ro llj ̂tr^r%

Enrollment

S3 7 ? .

Teachers and ESRPs

per 1000 students 3 3 . C, 32*. O

Pupil/Teacher Ratio 3 0 * 0 3 9 . 3

Average Teacher

and ESRP annual

salary

Teacher and ESRP cost per pupil

S Z s ff fO . Z i JJ, 2 .1). 2 9

# g / .£ o 3 * & . * r

516/71Paul V. Smith