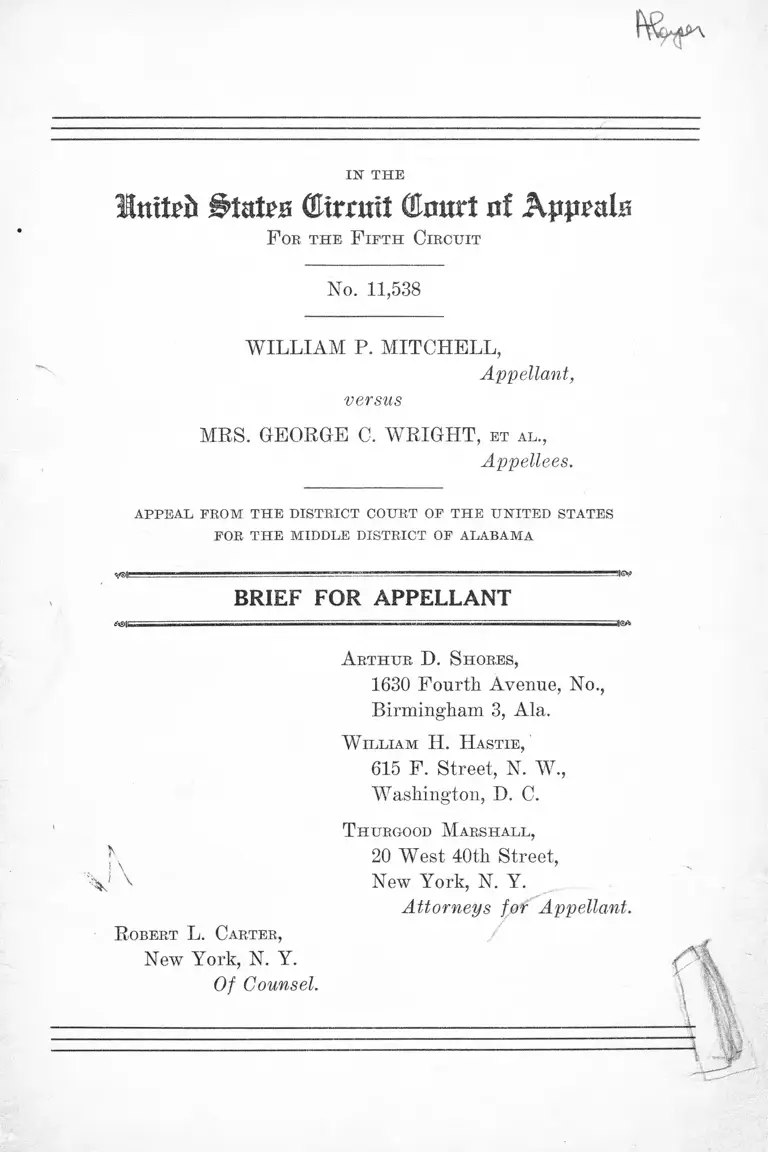

Mitchell v. Wright Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1946

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mitchell v. Wright Brief for Appellant, 1946. ffe9cf0b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6943a6a9-58e8-4533-92ae-4679ab215515/mitchell-v-wright-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Intteft States Ctmtil €mtrt of Kppmhz

F oe t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 11,538

WILLIAM P. MITCHELL,

Appellant,

versus

MRS. GEORGE C. WRIGHT, e t a l .,

Appellees.

A P PE A L FRO M T H E DISTRICT COURT OF T H E U N IT E D STATES

FOR T H E M IDDLE DISTRICT OF A LAB A M A

I » ■; " .........""r'1" ..... - - ..................... V . . ' - ^ ■—pSy

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

-------------: ------------------- r— - - - - - ■ ■■■TT===--r---r— ................v. .....

A r th u r D . S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, No.,

Birmingham 3, Ala.

W illiam II . H astie , '

615 F. Street, N. W.,

Washington, D. C.

! \ V v

R obert L. Carter,

New York, N. Y.

Of Counsel.

T hurgood M arsh all ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Case__________________________________ 1

Statement of Facts____________________________ _____ 2

Specifications of Error______________ 3

Argument __________ _________________________ 5

I Federal Courts Have Jurisdiction of the Present

Cause of Action___ _____________________________ 5

A. Section 41 (11) and (14) of Title 28 of the

United States Code Gives the Federal Courts

Jurisdiction of Appellant’s Cause of Action____ 5

B. Appellant’s Failure to Pursue or Exhaust

His Rights Under State Law Does not Oust the

Federal Courts of Jurisdiction_________________ 7

II Appellees’ Refusal to Register Appellant Solely

Because of His Race or Color Violated the Con

stitution and Laws of the United States---------- 13

A. The Right to Vote is secured by the Fifteenth

Amendment Against Restrictions Based on Race

or C olor_____________________________________ 13

B. The Right of Qualified Electors of the Sev

eral States to Choose Members of Congress Is

Secured and Protected by Article I, Section 2

and by the Seventeenth Amendment of the

United States Constitution___________________ 14

C. The Policy of Requiring Negro Applicants

for Registration to Submit to Tests Not Re

quired of Other Applicants Violates the Four

teenth Amendment ----------------1------------------------ 16 III

III Appellant May Properly Maintain This Suit as a

Class Action Under Rule 23 (a) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure —----------------------------- 19

11

IV Appellant May Properly Seek a Declaratory Judg

PAGE

ment ____________________________ 23

V Action of Appellees in Refusing to Register Appel

lant Makes them Liable to the Appellant for Dam

ages Under the Provisions of Sections 31 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code_______________ 27

Conclusion_________________________________________ 28

Appendix A _____ 31

Appendix B _______________________________________ 41

Appendix C _______________________________________ 51

Appendix D ______________________________________ 52

Table of Cases.

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 U. S. 227, 57

S. Ct. 461, 81 L. Ed. 617 (1937)_L________________ 23, 24

Alston v. School Board, 112 F. (2d) 992 (C. C. A. 4th,

1940) -------------------------------------------------------------- 22,26

Atwood v. Natl. Bank of Lima, 115 F. (2d) 861 (C. 0.

A. 6th, 1940)______ :_____________________________ 22

Bacon v. Rutland R, Co., 232 U. S. 134, 34 S. Ct. 283, 58

L. Ed. 538 (1914)________________________________ 8

Berry v. Davis, 15 F. (2d) 488 (C. C. A. 8th, 1926)___ 6

Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 U. S. 277, 58 S. Ct. 205, 82 L.

Ed. 252 (1937)__________________________________ 14

Chew v. First Presbyterian Church of Wilmington, 237

Fed. 219 (D. C. Del., 1916)_______________________ 20

Clarke et al. v. Goldman, 124 F. (2d) 491 (C. C. A. 2nd,

1941) __________________________________________ 22

Cloyes v. Middlebury Electric Co., 80 Vt. 109, 66 Atl.

1039 (1907) _____________________________________ 22

Cromwell v. Hillsborough T. P., Somerset County, N.

J., 149 F. (2d) 617 (C. C. A. 3d, 1945), aff’d. U. S.

Supreme Court, Oct. Term 1945, decided Jan. 29,

1946 ____________________________________________ 26

PAGE

Davis v. Cook, 55 F. Supp. 1004 (N. D. Ga., 1944),.__ 22,

Devoe v. United States, 103 F. (2d) 584 (C. C. A. 8th,

1939) __________________.________ _______________

Ex Parte Siebold, 100 U. S. 371, 25 L. Ed. 717 (1879)__

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 346 25 L. Ed. 676 (1880)-...

Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651, 4 S. Ct. 152, 28 L.

Ed. 274 (1884)_________ — ____________________ 14,

Farmers Co.-Op. Oil Co. v. Soeony Vacuum Oil Co. Inc.,

133 F. (2d) 101 (C. C. A. 8th, 1942)_______________

Gilchrist v. Interborough Rapid Transit Co., 279 U. S.

159, 49 S. Ct. 282, 73 L. Ed. 652 (1929)____________

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct. 926, 59

L. Ed. 1340 (1915)____________ ...______ ________6,13,

Hawarden v. Youghiogheny & L. Coal Co., I l l Wis.

545, 87 N. W. 472 (1901)_______________ ________20,

Henderson Water Co. v. Corporation Commission, 269

U. S. 279, 46 S. Ct, 112, 70 L. Ed. 273 (1925)_______

Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227

U. S. 278, 33 St. Ct. 312, 57 L. Ed. 510 (1913)______

Hunter v. Southern Indemnity Underwriters, 47 F.

Supp. 242 (E. D. Ky., 1942)________________ ______

Independence Shares Carp, et al. v. Deekert, et al.,

108 F. (2d) 51 (C. C. A. 3rd, 1939)--.,___________20,

Iowa-Des Moines Natl. Bank v. Bennett, 284 U. S. 239,

52 S. Ct. 133, 76 L. Ed. 265 (1931)________________

Heavy v. Anderson, 2 F. R. D. 19 (R. I., 1941)________

Kvello v. Lisbon, 38 N. D. 71, 164 N. W. 305 (1917)____

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S, Ct. 872, 83 L. Ed.

1281 (1939) ____________________ 6, 8, 9,10,12,13,14,

McDaniel v. Board of Public Instruction, 39 F. Supp.

638 (N. D. Fla., 1941) - . . .___________...___________22,

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368, 35 S. Ct. 932, 59 L.

‘ Ed. 1349 (1915)— — ______________________ 13,14,

Natural Gas Pipeline Co. v. Slattery, 302 U. S. 300, 58

S. Ct. 199, 82 L. Ed. 276 (1937)____________________

Natl. Hairdressers & Cosmetologists Assn. Inc. v. Phil.

Co., 41 F. Supp. 701 (D. C. Del., 1941)____________20,

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73, 52 S. Ct. 484, 76 L. Ed.

984 (1932) ____________________ __________________6,

26

15

15

16

15

22

9

14

22

9

17

20

22

17

22

22

28

26

28

8

22

19

IV

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 47 S. Ct. 446, 71 L. Ed.

759 (1927) _______________________________ _______6,19

Oppenheimer, et al. v. F. J. Young & Co. Inc., 144 F.

(2d) 387 (C. C. A. 2d, 1944)_____________________ 20, 22

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, 265

U. S. 196, 44 S. Ct. 553, 68 L. Ed. 975 (1924)____8, 9,10

Porter v. Investors Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461, 52 S. Ct.

617, 76 L. Ed. 1226 (1932) aff’d on rehearing 287

IT. S. 346, 53 S. Ct. 132, 77 L. Ed. 354 (1932)______ 8

Prentiss v. Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 IT. S. 210, 29

S. Ct. 67, 53 L. Ed. 150 (1908)___________________ 8,9

Railroad & Warehouse Commission Co. v. Duluth Street

R. Co., 273 U. S. 625, 47 S. Ct. 489, 71 L. Ed. 807

(1927) _______________________________________ ___ 9

Skinner v. Mitchell, 108 Kan. 861, 197 P. 569 (1921) _ 22

Smith v. Allwright, 321 IT. S. 649, 64 S. Ct. 757, 88 L.

Ed. 987 (1943)_____________________ 13,14,15,18, 21, 28

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1, 64 S. Ct. 397, 88 L. Ed.

497 (1944) _______ .1_____________________________ 19

State Corporation Commission v. Wichita, 290 U. S.

561, 54 S. Ct. 321, 78 L. Ed. 500 (1934)._________ - - 8,10

Trade Press Pub. Co. v. Milwaukee Type Union, 180

Wis. 449, 193 N. W. 507 (1923)________________ 22

Trice Products Corp. v. Anderson Co., 147 F. (2d) 721

(C. C. A. 7th, 1945)_____________________________ 24

Trudeau v. Barnes, 65 F. (2d) 563 (C. C. A. 5th, 1933)Ml, 12

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, 61 S. Ct. 1031,

85 L. Ed. 1368 (1941)____________________ 14,15,18,19

United States v. Mosely, 238 U. S. 383, 35 S. Ct. 904, 59

L. Ed. 1335 (1915)....______________________________ 14

United States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214, 23 L. Ed. 563

(1876)___________ _______________ -_____ „_______ 13,14

United States v. Sing Tuck, 194 U. S. 161, 24 S. Ct. 621,

48 L. Ed. 917 (1904)____________________________ 9

Weeks v. Bareco Oil Co., 125 F. (2d) 84 (C. C. A. 7th,

1941)____________________________ _____________ 20, 22

Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58, 21 S. Ct. 17, 45 L. Ed. 84

(1899)___________________________________________ 14

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064, 30 L.

Ed. 220 (1886)_______________________ -_________16,19

York v. Guaranty Trust Co. of New York, 143 F. (2d)

503 (C. C. A. 2d, 1944)___________________________ 22

PAGE

V

United States Constitution.

PAGE

Section 2, Article I___________________________3, 5, 6,13,14

Fourteenth Amendment_______________________4, 6,11,16

Fifteenth Amendment __________________ 5, 6,11,13,14, 21

Seventeenth Amendment______________________ 5, 6,13,14

Alabama Constitution.

Section 177, Article VIII____________ 3

Section 178, Article VIII__________ 3

Section 181, Article VIII________________________ 3

Section 182, Article VIII___________________________ 3

Section 184, Article VIII___________________________ 13

Section 186, Article VIII—__________________,_______ 3,18

Louisiana Constitution.

Section 5, Article VIII_____________________________ 11

Statutes.

Section 31, Title 8, U. S. Code_____________4, 5, 7,15, 27, 28

Section 43, Title 8, U. S. Code_____________4, 5, 7,15, 27, 28

Section 400, Title 28, U. S. Code (Section 274, Judicial

Cod©) __________ _ __ __ 23 33

Section 41 (11), Title 28, U. S. Code__________________ 4, 5

Section 41 (14), Title 28, U. S. Code_____________ 4, 5, 6

Section 51, Title 18, U. S. Code________________________ 15, 34

Section 54, Title 18, U. S. Code________________________ 15, 34

Section 55, Title 18, U. S. Code__________ 15

Section 56, Title 18, U. S. Code____________ _■_________ 15

Section 57, Title 18, U. S. Code____________________ 15

Section 58, Title 18, U. S. Code_____________________ 35

Sections 61a-h, Title 18, U. S. Code__________________ 15

Section 21, Title 17, Alabama Code 1940___13,16,18

Section 24, Title 17, Alabama Code 1940_______ 18

Section 32, Title 17, Alabama Code 1940______ 3

Section 35, Title 17, Alabama Code 1940____________ 7, 9,18

26 Okla. Stat. Sec. 74_______________________<________9; 52

Treatises and Articles.

Anderson, Declaratory Judgments (1940)____________ 23

Borchard, Declaratory Judgments (2nd Ed. 1941)_____ 23

Wheaton, Representative Suits Involving Numerous

Litigants, 19 Corn L. Q. 399, 407, 433 (1934)_______ 20

Moore, Federal Practice (1938)____________________ 20, 21

18 Am. Jur. 332, Section 62_________________________ 23

IN TH E

luitrfr ^fatru Ctmrit Court of Appraio

F oe th e F if t h C ircu it .

No. 11,538

W il l ia m P. M it c h e l l ,

Appellant,

vs.

M es. G eoege C. W eig h t , et al .,

Appellees.

A P PE A L FR O M T H E DISTRICT COURT OF T H E U N IT E D STATES

FOR T H E M IDDLE DISTRICT OF ALAB A M A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

P A R T O N E

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal by the appellant, William P. Mitchell,

from an order below entered in the District Court of the

United States for the Middle District of Alabama on

October 12, 1945 (E. 35) in the above entitled cause on mo

tion to dismiss appellant’s complaint, as amended.

The amended complaint, tiled on October 3, 1945, alleged

that on July 5, 1945, the defendants below, as the registrars

of voters of Macon County, Alabama, pursuant to a general

policy, custom or usage of refusing to register qualified

Negro electors, refused to register plaintiff below solely

2

on account of race and color (R. 6). It is also alleged that

the defendants below have maintained a policy, custom or

usage of denying to plaintiff below and other qualified Negro

electors, the equal protection of the laws by requiring them

to submit to tests not required of white electors and re

fusing to register qualified Negro electors while at the same

time registering white electors with less qualifications than

Negro electors (R. 5). In addition the allegation was made

that this refusal and denial violate the Constitution and

laws of the United States (R. 3). The complaint prayed

for a declaratory judgment, a permanent injunction and

Five Thousand dollars in damages (R. 7). The appellees

filed a motion to dismiss on August 30, 1945 (R. 9-21), an

amendment to such motion on September 20, 1945 (R. 21-

23), and a motion to dismiss the amended complaint on

October 5, 1945 (R. 23-24). On October 12, 1945, Judge

C. B. K ennaner issued an order sustaining appellees’

motion to dismiss and dismissing the complaint as amended

(R. 35), and filed an opinion setting forth reasons and

authority for the issuance of the aforesaid order (R. 25-35).

Statement of Facts

The complaint, as amended, alleges that: appellant is

a colored person of African descent and Negro blood. He

is a native-born citizen of the United States, a bona fide

resident of the State of Alabama and is over twenty-one

years of age. He is a taxpayer of the aforesaid state, pays

taxes on real property with an assessed evaluation in ex

cess of three hundred dollars ($300.00) and has paid in full

the taxes due on said property prior to the time he offered

to register. He is neither an idiot nor an insane person;

nor has he been convicted of any felony or crime. He is

able to read and write any passage in the United States

Constitution in the English language. In short, appellant

3

possesses all the qualifications and none of the disquali

fications requisite for registration and voting under the

Constitution and laws of the United States and of the State

of Alabama. (The Constitution of United States, Article I,

Section 2 and the Seventeenth Amendment. The Constitu

tion of Alabama Sections 177, 178, 181, 182, 186; Alabama,

Code of 1940, Section 32 of Title 17.) All parties to this ac

tion, both appellant and appellees, are citizens of the United

States and are residents of and domiciled in the State of

Alabama (R. 3). Appellees are the duly appointed, quali

fied and active registrars of voters of Macon County,

Alabama (R. 4), and were acting in that capacity on July

5, 1945 when appellant presented himself and made appli

cation for registration at the Macon County Court House,

the regular place for the registration of persons qualified

to register. Appellant filled out the required form for

registration, produced two persons to vouch for him as re

quired by appellees, correctly answered such questions as

were asked in proof of his qualifications and was ready,

willing and able to give any further information and evi

dence necessary to entitle him to be registered (R. 6).

Appellees did not require white persons presenting them

selves for registration to present other persons to vouch

for them but registered such persons forthwith (R. 6).

Appellant, however, was required to wait long hours before

being permitted to file his application and was required to

present persons to vouch for him as aforesaid (R. 6) . In

presenting himself at the Macon County Court House on

July 5, 1945 to register, appellant was seeking to qualify

to vote in any forthcoming election of federal or state

officers (R. 6). Despite the fact that appellant possessed

those qualifications necessary to entitle him to register, ap

pellees refused to register appellant solely on the basis of

his race and color (R. 6).

4

P A R T T W O

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred:

1. In sustaining appellees’ motion to dismiss and in dis

missing appellant’s amended complaint.

2. In sustaining appellees’ motion to dismiss the com

plaint, as amended, on the grounds that appellant could

not properly bring this action as a class suit under Rule

23 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

3. In sustaining appellees’ motion to dismiss on the

ground that appellant could not properly maintain this suit

in the form of an action seeking a declaratory judgment.

4. In refusing to issue a permanent injunction forever

restraining and enjoining the appellees from subjecting

Negroes to tests not required of white applicants as a pre

requisite to registration.

5. In refusing to find that the Court had jurisdiction

under subdivisions 11 and 14 of Section 41 of Title 28, and

under Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8, of the United States

Code.

6. In refusing to deny appellees’ motion to dismiss

since appellant’s complaint clearly shows that appellees

wrongful acts deprived appellant and all those similarly

situated of the equal protection of the laws in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion.

7. In refusing to deny appellees’ motion to dismiss

since appellant’s complaint clearly shows that by virtue of

appellees’ wrongful acts, appellant and others similarly

situated, were denied rights secured to all citizens of the

5

United States by Section 2, Article I and by the Seven

teenth Amendment of the United States Constitution to

participate in elections of federal officers.

8. In refusing to deny appellees’ motion to dismiss

since appellant clearly shows in his complaint that the

acts of appellees deprived appellant of the right to vote

solely on account of race and color in violation of the Fif

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

9. In refusing to deny appellees’ motion to dismiss

the complaint since appellant clearly shows in his complaint

that the appellees’ conduct made them liable to appellant

in damages under the provisions of Section 31 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code.

P A R T T H R E E

ARGUMENT

I

Federal Courts Have Jurisdiction of the Present

Cause of Action.

A . Section 41 (1 1 ) and (1 4 ) of Title 28 of the

United States Code Gives the Federal Courts

Jurisdiction of the Appellant’s Cause of Action.

Jurisdiction is invoked pursuant to subdivisions 11 and

14 of Section 41 of Title 28 of the United States Code. Sub

division 11 of Section 41 provides:

“ The district courts shall have original jurisdic

tion as follows: . . . ‘ Of all suits brought by any

person to recover damages for any injury to his per

son or property on account of any act done by him,

under any law of the United States, for the protec

tion or collection of any of the revenues thereof, or

6

to enforce the right of citizens of the United States

to vote in the several states.’ ” (Italics ours.)

This is an action to recover damages for the refusal of

appellees, who are registrars of voters in Macon County,

Alabama, to register appellant and qualified Negro appli

cants similarly situated, solely on account of their race and

color. Since such registration is a prerequisite to the right

of a citizen of the United States to vote in any election in

the State of Alabama including the election of federal offi

cers, appellees ’ refusal was an effective deprivation of the

voting privileges. As such the federal courts have undis

puted jurisdiction. Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S, 536, 47 S.

Ct. 446, 71 L. Ed. 759 (1927); Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S.

73, 52 S. Ct. 484, 76 L. Ed. 984 (1932); Lane v. Wilson, 307

U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L. Ed. 1281 (1939); Guinn v.

United States, 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct. 926, 59 L. Ed. 1340

(1915); Berry v. Davis, 15 F. (2d) 488 (C. C. A. 8th, 1926).

Subdivision 14 of section 41 of Title 28 provides:

“ The district court shall have original jurisdic

tion as follows: . . . ‘ Of all suits at law or in equity

authorized by law to be brought by any person to

redress the deprivation, under color of any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of

any State, of any right, privilege, or immunity, se

cured by the Constitution of the United States, or

of any right secured by any law of the United States

providing for equal rights of citizens of the United

States or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States.’ ’ ’

Appellant’s suit also is an action at law to redress the

deprivation under color of law, statute, regulation, custom

or usage of a right, privilege, or immunity secured by the

United States Constitution, namely Section 2, of Article I,

the Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Seventeenth Amendments,

7

and of a right secured by law of the United States providing

for equal rights of citizens, namely, Sections 31 and 43 of

Title 8 of United States Code.

b / a ,

/ R

Appellant’s Refusal to Pursue or Exhaust His

Rights Under State Law Does Not Oust the

Federal Courts of Jurisdiction.

The S^ate of Alabama, under Section 35 of Title 17 of

the Alabama Code of 1940 gives the right of appeal when

registration's denied as follows:

/ “ Any person to whom registration is denied shall

have the right to appeal, without giving security for

costs, within thirty days after such denial, by filing

a petition in the circuit Court or Court of like juris

diction held for the county in which he or she seeks

to register, to have his or her qualifications as an

elector determined. Upon the filing of the petition,

the clerk of the Court shall give notice thereof to

the solicitor authorized to represent the state in said

county, who shall appear and defend against the

petition on behalf of the state. Upon such trial the

Court shall charge the jury only as to what consti

tutes the qualifications that entitle the applicant to

become an elector at the time he or she applied for

registration, and the jury shall determine the weight

and effect of the evidence, and return a verdict.

From the judgment rendered an appeal will lie to

the supreme Court in favor of the petition to be

taken within thirty days. Final judgment in favor

of the petitioner shall entitle him or her to regis

tration as of the date of his or her application to

the registrars.”

The remedy herein provided cannot be considered ad

ministrative. On the contrary, it is the type of proceeding

traditionally considered judicial. The aggrieved party may

go into the circuit court or a court of like jurisdiction in

the county in which he seeks to have his registration deter

8

mined. The solicitor of the state is authorized to appear

as the representative of the state and defend the action

of the registrars on behalf of the state. A trial by jury is

provided, and the court is required to charge the jury as

to what constitutes the qualifications entitling an applicant

to become an elector at the time of his application for regis

tration. The jury is required to determine the weight and

effect of the evidence and return a verdict. An appeal to

the Supreme Court of the State may be taken from an

adverse decision in the circuit court. It is difficult to con

ceive of a procedure having more of the earmarks of an

ordinary and conventional judicial proceeding than that

provided herein.

State remedies that are judicial in nature need not be

pursued or exhausted before an action can be maintained

in the federal courts. State Corporation Commission v.

Wichita, 290 U. S. 561, 54 S. Ct. 321, 78 L. Ed. 500 (1934);

Porter v. Investors Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461, 52 S. Ct. 617,

76 L. Ed. 1226 (1932) aff’d on rehearing, 287 U. S. 346, 53

S. Ct. 132, 77 L. Ed. 354 (1932); Bacon v. Rutland R. Co.,

232 U. S. 134, 34 S. Ct. 283, 58 L. Ed. 538 (1914); Pacific

Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, 265 U. S. 196,

44 S. Ct. 553, 68 L. Ed. 975 (1924); Lane v. Wilson, supra.

Whenever the question has been presented the United

States Supreme Court has examined the remedy provided

to determine whether it was legislative or judicial in nature.

Prentiss v. Atlantic Coast Line Co., 211 TJ. S. 210, 29 S. Ct.

67, 53 L. Ed. 150 (1908); Lane v. Wilson, supra; Pacific

Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, supra; Porter v.

Investors Syndicate, supra. Only in the former instance

was it deemed necessary that the remedy be exhausted

before suits could be perfected in the federal courts. Nat

ural Gas Pipeline Co. v. Slattery, 302 U. S. 300, 58 S. Ct.

199, 82 L. Ed. 276 (1937); Porter v. Investors Syndicate,

9

supra; Gilchrist v. Interborough Rapid Transit Co., 279

U. S. 159, 49 S. Ct. 282, 73 L. Ed. 652 (1929); Railroad and

Warehouse Commission Co. v. Duluth Street R. Co., 273

IT. S. 625, 47 S. Ct. 489, 71 L. Ed. 807 (1927); Henderson

Water Co. v. Corporation Commission, 269 U. S. 279, 46 S.

Ct. 112, 70 L. Ed. 273 (1925); Pacific Telephone & Tele

graph Co. v. Kuykendall, supra; Prentiss v. Atlantic Coast

Line Co., supra; United States v. Sing Tuck, 194 U. S. 161,

24 S. Ct. 621, 48 L. Ed. 917 (U " ' x

In its opinion sustaining appeiiees’ motion to dismiss

the court below attempted to distinguish this proceeding

from that before the United States Supreme Court in Lane

v. Wilson, supra, on the grounds that in the latter case the

“ law itself worked discrimination against the colored race”

(II. 34). Counsel for appellant after a careful examination

of the facts before the Court and the opinion in Lane v.

Wilson can find no conceivable basis for this attempted dis

tinction.

In Lane v. Wilson there was before the Court an Okla

homa statute (26 Okla. Stat. Sec. 74) which in effect denied

to Negroes the right to register and vote solely on the basis

of race and color. The state provided an appeal from the

refusal of a registration officer to register a qualified elector

similar to that provided by the Alabama Code, supra.1 In

answer to objections that the remedies provided by the

state should have been exhausted before the instant pro

1 The Oklahoma Statute (26 Okla. Stat. Sec. 74) provided in

part: “ and provided further, that wherever any elector is refused

registration by any registration officer such action may be reviewed

by the district court of the county by the aggrieved elector by his

filing within ten days a petition with the Clerk of said Court where

upon summons shall be issued to said registrar requiring him to

answer within ten days, and the district court shall be (give an) an

expeditious hearing and from his judgment an appeal will lie at the

instance of either party to the Supreme Court of the State as in civil

cases. * * * ”

10

ceeding could be maintained in the federal courts, Mr. Jus

tice F raxkftjrteb, speaking for the Court, said at page 274:

“ Normally, the state legislative process, some

times exercised through administrative powers con

ferred in state courts, must be completed before

resort to the federal courts can be had. . . . But

the state procedure open for one in the plaintiff's

situation . . . has all the indicia of a conventional

judicial proceeding and does not confer upon the

Oklahoma courts any of the discretionary or initia

tory functions that are characteristic of adminis

trative agencies, . . . Barring only exceptional cir

cumstances, . . . or explicit statutory requirements,

. . . resort to a federal court may he had without

exhausting the judicial remedies of state courts

(Italics ours.)

The Supreme Court did not indicate that its ruling—

that judicial remedies need not be exhausted before resort

could be had to a federal court—would apply only where a

statute involved was discriminatory on its face. On the con

trary, the opinion expressly states that the rule would be

applicable except in unusual circumstances or by virtue of

explicit statutory requirements. The remedy provided by

Alabama for an appeal for refusal to register a qualified

elector, even more so than that under consideration in

Lane v. Wilson, has all the distinguishing characteristics

which England and America have come to associate with

a judicial proceeding. Under the rule of Lane v. Wilson,

supra; State Corporation Commission v. Wichita, supra;

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, supra,

appellant is authorized to institute an action in the federal

courts for wrongful refusal of appellees to register him

without first pursuing or exhausting the remedy provided

by the State of Alabama.

11

The court below also cites Trudeau v. Barnes, 65 F. (2d)

563 (C. C. A. 5th, 1933) as authority for its position that

appellant must first pursue the remedies open in the State

of Alabama before being allowed to seek redress in the

federal courts. This case was an appeal from a judgment

in the court below dismissing a petition to recover damages

for the deprivation of the right of appellant to register as

a voter in the State of Louisiana. Petitioner attempted

to pursue two inconsistent causes of action. In one the

arbitrary refusal of the registrars to register appellant

was contested on the ground that such action was contrary

to the Constitution and laws of Louisiana. The other at

tempted to show that the “ understanding clause” of the

Louisiana Constitution violated the Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. This

Court found, as to the first cause of action, that the peti

tion failed to state facts sufficient to show that the applicant

was entitled to register. As to the second cause of action,

this Court found that the “ understanding clause” of the

Louisiana Constitution did not violate any provision of the

Federal Constitution since it applied equally to all appli

cants for registration and was not based on race or color.

However, in considering Article 8, Section 5 of the Louisi

ana Constitution 2 which provides a state remedy to appeal

2 Article 8, Section 5, La. Constitution provides: “ Any person

possessing the qualifications for voting prescribed by this Constitu

tion, who may be denied registration, shall have the right to apply

for relief to the district court having jurisdiction of civil causes for

the parish in which he offers to register. Said court shall then try

the cause, giving it preference over all other cases, before a jury of

twelve, nine of whom must concur to render a verdict. This verdict

shall be a final determination of the cause. The trial court may,

however, grant one new trial by jury. In no cases shall any appeal

lie or any other court exercise the right of review * * *.

12

the refusal of a registrar to register an applicant, Judge

B ryan of this Court said:

“ It is idle to say that the defendant as registrar

had the arbitrary power to deny plaintiff the right

to vote. We cannot say and refuse to assume, that, if

the plaintiff had pursued the administrative remedy

that was open to him, he would not have received

any relief to which he was entitled. At any rate, be

fore going into Court to sue for damages, he was

hound to exhaust the remedy afforded him by the

Louisiana Constitution.” (Italics ours.)

If this portion of the opinion means that all state reme

dies, whether judicial or administrative, must he exhausted

before resort can be had to the federal courts, it is in

consistent with Lane v. Wilson, supra, and the long line

of decisions cited ante which have held that only where

the state remedy was legislative did it have to be com

pleted before the federal courts could entertain juris

diction. Trudeau v. Barnes, therefore, cannot he consid

ered persuasive or authoritative if contrary to these rul

ings and precedents of the United States Supreme Court.

There this Court properly stated the rule that adminis

trative remedies had to be exhausted before resort could

be had to the federal courts. The rule, however, was wrong

fully applied since the state remedy under consideration

was judicial and not administrative. Lane v. Wilson, supra.

Further than that, as will be developed in a subsequent por

tion of this brief, the instant litigation is the especial con

cern of the federal courts since appellant and those similarly

situated were attempting to qualify as electors in order to

participate in the election of federal as well as of state

officers.

13

II

Appellees’ Refusal to Register Appellant Solely

Because of His Race or Color Violated the

Constitution and Laws of the United States.

A. The Right to Vote Is Secured by the Fifteenth

Amendment Against Restrictions Based on

Race or Color.

The State of Alabama makes registration a prerequisite

to the right to qualify as an elector and vote in any election

held within the State. Constitution of Alabama, Section

184, Alabama Code of 1940, Title 17, Section 21. This re

quirement by the very terms of Article I, Section 2 and

the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion is incorporated therein and becomes a prerequisite for

voting in any election in the State held to choose Alabama’s

Congressional and Senatorial representatives.3

Precedents of the United States Supreme Court have

firmly fixed the rule that regulations which are designed to

prevent persons from qualifying to vote solely on the basis

of race or color cannot stand in the face of the express

terms of the Fifteenth Amendment. Lane v. Wilson, supra;

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368, 35 S. Ct. 932, 59 L. Ed.

1349 (1915); Guinn v. United States, supra. This constitu

tional guaranty still leaves the states free to enact reason

able regulations concerning suffrage and to demand that

its electors meet reasonable requirements and standards

as long as such regulations, requirements and standards

are not based on considerations of race or color. United

States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214, 23 L. Ed. 563 (1876); Lane v.

Wilson, supra; Guinn v. United States, supra; Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. S. 649, 64 S. Ct. 757, 88 L. Ed. 987 (1943).4

3 See infra, pp. 14-16.

1 See annotation on effect of the Fifteenth Amendment in 23 L.

Ed. 563.

14

Despite the wide authority and discretion which a state

may validly exercise in regulating the election process, the

right to vote is considered a right grounded in the Fed

eral Constitution. United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299,

61 S. Ct. 1031, 85 L. Ed. 1368 (1941); Ex parte Yarbrough,

110 IT. S. 651, 4 S. Ct. 152, 28 L. Ed. 274 (1884); Wiley v.

Sinkler, 179 TJ. S. 58, 21 S. Ct. 17, 45 L. Ed. 84 (1899);

United States v. Mosely, 238 U. S. 383, 35 S. Ct. 904, 59 L.

Ed. 1355 (1915). But cf. United States v. Reese, supra;

Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 U. S. 277, 58 S. Ct. 205, 82 L. Ed.

252 (1937), and annotation in 23 L. Ed. 563, on the effect of

the Fifteenth Amendment.

It is now clearly settled that the provisions of the Fif

teenth Amendment may effectively reach each and every

stage of the electoral process. Wherever in that process

restrictions of race or color are erected, such restrictions

violate the Fifteenth Amendment. Myers v. Anderson,

supra; Guinn v. United States, supra; Lane v. Wilson,

supra; United States v. Classic, supra; Smith v. AUwright,

supra. Refusal to permit one to register, therefore, solely

on the basis of race and color is clearly within the prohibi

tions of the Fifteenth Amendment and has been so held.

Lane v. Wilson, supra; Myers v. Anderson, supra; Guinn

v. United States, supra.

B. The Right of Qualified Electors of the Several

States to Choose Members of Congress Is Se

cured and Protected by Article / , Section 2 and

by the Seventeenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution.

Section 2 of Article I of the Constitution of the United

States provides that members of the House of Represen

tatives shall be chosen every second year by the people of

the several states and that the electors in each state shall

15

have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most

numerous branch of the state legislature.

The right of electors of the several states to choose their

representatives is a right secured and guaranteed by the

Federal Constitution to those citizens of the several states

entitled to exercise that power. Since these constitutional

provisions are without qualifying limitations, the rights

therein guaranteed run against individual as well as state

action. Ex parte Yarbrough, supra; United States v. Clas

sic, supra.

Registration is a prerequisite to participate in any elec

tion held in the State of Alabama for the election of federal

officers and is an integral part of the electoral process.

Failure of appellant to be a registered elector prior to such

forthcoming federal elections will disqualify him to cast

his vote for the election of federal representatives of the

State of Alabama, The protection of the right of a citizen

of the United States to participate in the election of federal

officers has long been considered the particular and especial

concern of the United States Government. Ex parte Siebold,

100 U. S. 371, 25 L. Ed. 717 (1879); Ex parte Yarbrough,

supra; United States v. Classic, supra; Smith v. Allwright,

supra; Devoe v. United States, 103 F. (2d) 584 ( 0. C. A. 8th,

1939). The federal government has also been deemed to

have sufficient authority under the Constitution to enact

legislation designed to keep the federal elections free from

fraud, force and coercion. Title 18, Sections 51, 54, 56, 57,

58 and 61 and Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8 of the U. S.

Code.

Appellant therefore is no requesting this Court to per

form any new or unusual duty but is requesting that the

Court exercise its authority over a subject matter which has

been traditionally considered within the jurisdiction of the

federal courts.

16

C. The Policy of Requiring Negro Applicants for

Registration to Submit to Tests Not Required

of Other Applicants Violates the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Appellees in the instant proceedings are state officers

and hold such office pursuant to provisions of Section 21,

Title 17 of the Alabama Code of 1940. The acts of appel

lees were committed in the course of the performance of

their administrative duties of registering all qualified elec

tors within Macon County pursuant to the constitution and

laws of the State of Alabama. In requiring appellant to

submit to tests not required of white applicants, and in re

fusing to register appellant solely on the basis of race and

color, appellees violated the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, which provides that “ . . . No state

shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.” This provision is clearly violated

where a law, however fair on its face, is administered in a

discriminatory manner. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S.

356, 6 S. Ct. 1064, 30 L. Ed. 220 (1886). Although this

amendment only reaches state action, such action within

the meaning of its provisions is the action of any agent who

is a repository of state authority, whether a part of exec

utive, legislative or judicial departments of the state gov

ernment. As the United States Supreme Court said in Ex

parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 313, 346, 347, 25 L. Ed. 676, 679

(1880):

“ We have said the prohibitions of the Fourteenth

Amendment are addressed to the States. . . . They

have reference to actions of the political body de

nominated a State, by whatever instruments or in

whatever modes that action may be taken. A State

acts by its legislative, its executive or its judicial

authorities. It can act in no other way. The consti

tutional provision, therefore, must mean that no

17

agency of the State or of the officers or agents by

whom its powers are exerted, shall deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws. Whoever, by virtue of public position

under a State government, deprives another of prop

erty, life, or liberty, without due process of law, or

denies or takes away the equal protection of the laws,

violates the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts

in the name and for the State, and is clothed with

the State’s power, his act is that of the State. This

must be so, or the constitutional prohibition has no

meaning. Then the State has clothed one of its

agents with power to annul or to evade it.”

In Home Telephone & Telegraph Company v. City of

Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278, 287, 33 S. Ct. 312, 57 L. Ed. 510,

515 (1913), the Court speaking through Chief Justice

W h ite said:

“ . . . the theory of the [14] Amendment is that

where an officer or other representative of a state,

in the exercise of the authority with which he is

clothed, misuses the power possessed to do a wrong

forbidden by the Amendment, inquiry concerning

whether the state has authorized the wrong is irrele

vant, and the Federal judicial power is competent

to afford redress for the wrong by dealing with the

officer and the result of his exertion of power . . .

In lowa-Hes Moines National Bank v. Bennett, 284 U. S.

239, 246, 52 S. Ct. 133, 76 L. Ed. 265, 272 (1931), the United

States Supreme Court said:

“ . . . When a state official, acting under color of

state authority, invades, in the course of his duties,

a private right secured by the Federal Constitution,

that right is violated, even if the state officer not

only exceeded his authority but disregarded special

commands of the state law.”

18

Recently in United States v. Classic, supra, the Court

said:

“ Misuse of power, possessed by virtue of State

law and made possible only because the wrong-doer

is clothed with the authority of State law, is action

taken ‘ under color o f ’ State law.”

The instant case is similar in context to the situation

presented in the Classic case, and in Smith v. Allwright.

The rationale of the decision in the Classic case applies

to the instant proceedings since there can be no doubt that

appellees were officers of the state. Section 21 of Title 17

of the Alabama Code of 1940 and Section 186 of the Alabama

Constitution provide that registrars shall be appointed by

the Governor and the commissioners of agriculture and of

industries, or by a majority of these officers acting as a

board of appointment. Section 24 of Title 17 of the Alabama

Code provides that the state shall pay to each registrar

five dollars for each day’s attendance upon the sessions of

the Board. Section 35 of Title 17 of the Alabama Code and

Section 186 of the State Constitution provide that wherever

an appeal is taken under its provisions by any person to

whom registration is denied the solicitor authorized to rep

resent the State shall appear and defend the action of the

registrars on behalf of the State. Registration, being a pre

requisite to voting, is an integral part of the election process

and in performing the duties of registering qualified appli

cants, appellees are performing an important state function.

Appellees were pursuing a policy, custom or usage of sub

jecting qualified Negro electors to tests not required of white

applicants, nor by the laws and constitution of the State in

determining the qualifications of an elector. Appellees

further were pursuing a policy, custom, and usage of deny

ing to Negro qualified applicants the right to register, while

at the same time registering white electors with less qualifi

19

cations than those possessed by colored applicants. This

is clearly a denial of the equal protection clause within the

meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. Nixon v. Herndon,

supra; Nixon v. Condon, supra; United States v. Classic,

supra. See also Snowden v. Hughes, 321 II. S. 1, 88 L. Ed.

497, 64 S. Ct. 397 (1944); Yick Wo v. Hopkins, supra. As

such it is within the reach of federal power.

Ill

Appellant May Properly Maintain This Suit as a

Class Action Under Rule 23 (a) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Under Rule 23 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure one or more persons, adequately representative of

all, may bring an action on behalf of all members of a class,

where the persons constituting the class are sufficiently

numerous to make it impracticable to bring them all before

the court, and where the character of the right under litiga

tion is “ several, and a common relief is sought” . Appel

lant instituted the present proceeding in the Court below

on behalf of himself and as a representative of a class, com

posed of Negro citizens of the United States, residents and

citizens of the State of Alabama and of Macon County

similarly situated, who are qualified to register as voters

in Macon County of the aforesaid State, under the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States and of the State of Ala

bama (R. 3). The question herein presented—whether

registrars individually or a Board of Registrars collectively

may maintain a policy, custom or usage of denying to mem

bers of this class the equal protection of the laws, by re

quiring them because of their race and color to submit to

tests not required of white electors, and of refusing to regis

ter them on grounds not required by the Constitution and

laws of the United States and of the State of Alabama—

20

involve rights of common and general interest to all mem

bers of the class represented by appellant.

The class suit evolved early in English equity5 as a

device to escape the difficulties inherent in compulsory

joinder and to permit a single litigation of group injuries

in cases of common interest.6 With federal Rule 23 (a)

this doctrine was reformulated to suit the needs of modern

practice.7

Under this provision it is not necessary that all mem

bers of the class join in the suit. It is merely necessary

that one or more persons adequately representative of the

entire class institute the litigation. The other members of

the class may join as they see lit.8 The present litigation is

that type of class action labeled “ spurious” , Independence

Shares Corp. et al. v. Deckert, et al., 108 F. (2d) 51, (C. C.

A. 3rd, 1939); Weeks v. Bareco Oil Co., 125 F. (2d) 84 (C.

C. A. 7th, 1941); see Hunter v. Southern Indemnity Under-

luriters, 47 F. Supp. 242 (E. D. Ky., 1942); Natl. Hair

dressers & Cosmetologists Assn. Inc. v. Phil. Co., 41 F.

Supp. 701 (D. C. Del., 1941); Oppenheimer, et- al. v. F. J.

5 See on whole development 2 Moore, Federal Practice (1938)

2224 et seq.

6 Common interest has been variously defined. See Wheaton,

Representative Suits Involving Numerous Litigants (1934) 19 Com.

L. Q. 399, 407, 433. (Composite definitions of common interest.)

In addition to the difficulty in defining common interest, the courts

have been in disagreement as to whether the common interest need

be, only in questions of law, Hawarden v. Youghiogheny & L.

Coal Co., I l l Wis. 545, 87 N. W . 472 (1902), or in both questions

of law and fact, Chew v. First Presbyterian Church of Wilmington.

237 Fed. 219 (D . C. Del. 1916). The codifiers of Rule 23 (a ) must

have been aware of these conflicts and difficulties, however, for it is

expressly provided that the common interest may be either in law

or fact.

7 Every state today has a statute permitting class actions. The

provision common to all these statutes is the “ common or general

interest” of many persons. See Wheaton, op. cit. supra. Note 4.

8 See Moore, op. cit. supra.. Note 3.

21

Young & Co. Inc., 144 F. (2d) 387 (C. C. A. 2d, 1944); see

also 2 Moore op. cit. supra note 3, and requires nothing

more than a group with a common interest, seeking com

mon relief, to constitute the class.

The instant proceeding cannot be viewed merely as the

discriminatory practices of individual state officers against

an individual seeking to qualify for registration but must

be viewed in context as part of a scheme or device to effec

tively disfranchise all qualified Negro electors. Although

the Fifteenth Amendment was specifically designed to pre

vent barriers to the franchise being imposed based on race

or color, it has been necessary for the United States Su

preme Court to invalidate hurdle after hurdle erected to

circumvent this constitutional guaranty and deprive Ne

groes of the right to vote. The last of these barriers, the

right to participate in a primary election, was leveled in

Smith v. Allwright, supra. Under the authority of that

decision, Negro citizens of the United States and residents

of Alabama possessing the necessary qualifications of elec

tors attempted to register as voters.

In refusing to register appellant and in subjecting him

to tests not required by the Constitution and laws of the

United States and of the State of Alabama, and to which

white applicants were not subjected, appellees were pursu

ing a policy, custom, or usage of denying registration to

Negro applicants solely on the basis of race or color. All

Negroes similarly situated to appellant have a common in

terest in the questions herein presented because of appel

lees ’ wrongful acts, and in having these questions clarified

and determined as they affect the exercise of a fundamental

right secured by the Federal Constitution. The courts

have never based their decision on the propriety of a class

suit on whether the persons similarly situated actually

formed a class in esse before the injury complained of oc

22

curred, but only on whether the proceeding under inquiry

met the statutory requirements. See York v. Guaranty

Trust Co. of New York, 143 F. (2d) 503 (C. C. A. 2nd,

1944); Keavy v. Anderson, 2 F. (2d) 19 (1941); Atwood v.

Natl. Bank of Lima, 115 F. (2d) 861 (C. C. A. 6th, 1940);

Farmers Co.-Op. Oil Co. v. Socony Vacuum Oil Co. Inc.,

133 F. (2d) 101 (C. C. A. 8th, 1942) ; Clarke, et al. v. Gold

man, 124 F. (2d) 491 (C. C. A. 2nd, 1941). Where a group

of people are similarly injured by common practices of an

other, it is recognized that scope of the injury creates the

required class.9 Although registration concededly presents

individual questions, these individual issues have not been

considered relevant in determining whether a class suit

could be instituted, so long as apart from the independent

questions which had to be settled, there was presented some

fundamental question of common interest. See York v.

Guaranty Trust Co., supra; Independence Shares Corp. v.

Deckert, et al., supra; Oppenheimer, et al. v. T. J. Young

Co. Inc., supra; Alston v. School Board, 112 F. (2d) 992

(C. C. A. 4th, 1940); McDaniel v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, 39 F. Supp. 638 (N. D. Fla., 1941); Davis v. Cook, 55

F. Supp. 1004 (N. D. Ga., 1944).

As the Court said in Weeks v. Bareco Oil Co., supra:

“ The history of class suit litigation, its history

over a century of growth, the origin and status of

9Hawarden v. Youghiogheny, 111 Wis. 545, 87 N. W . 472

(1902) ; Trade Press Pub. Co. v. Milwaukee Type Union, 180 Wis.

449, 193 N. W . 507 (1923), class action permitted to enjoin a wrong

ful conspiracy; W eeks v. Bareco Oil Co., supra, class action per

mitted to recover damages caused by unlawful conspiracy; Cloyes v.

Middlebury Electric Co., 80 Vt. 109, 66 Atl. 1039 (1907), class suit

permitted to enjoin a nuisance; Natl. Hairdressers & Cosmetologists

Assn. Inc. v. Philad Co., supra, class suit permitted to declare patent

invalid and to enjoin defendants from asserting that plaintiff’s in

fringed their patent rights; Skinner v. Mitchell, 108 Kan. 861, 197

P. 569 (1921 ); Kvello v. Lisbon, 38 N. D. 71, 164 N. W . 305 (1917),

class action permitted to enjoin an invalid tax.

23

present Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure, are all persuasive of the necessity of a liberal

construction of this Rule 23, and its application to

this class of litigation. It should be construed to

permit a class suit where several persons jointly act

to the injury of many persons so numerous that their

voluntarily, unanimously joining in a suit is eon-

cededly improbable and impracticable. Under such

circumstances injured parties who are so mindful

may present the grievance to Court on behalf of all,

and the remaining members of the class may join as

they see fit.”

IV

Appellant May Properly Seek a Declaratory Judgment.

Judicial Code, Section 274d (28 U. S. C. 400) provides:

“ In cases of actual controversy (except with re

spect to federal taxes) the courts of the United

States shall have power upon petition, declaration,

complaint, or other appropriate pleadings to declare

rights and other legal relations of any interested

party petitioning for such declaration, whether or not

further relief is or could be prayed and such declara

tion shall have the force and effect of a final judgment

or decree and be reviewable as such.”

It is well established that a prayer for relief by declara

tory judgment may be joined with prayers for consequential

relief. Anderson on Declaratory Judgments (1940, at p.

253); Borchard on Declaratory Judgments (2d ed. 1941)

at 432; 18 Am. Jur. (Declaratory Judgments) sec. 62, p.

332; see also Rule 18, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The leading case on declaratory judgments is the case

of Aetna Life Insurance Company v. Haworth, 300 U. S. 227,

24

57 S. Ct. 461, 81 L. Ed. 617 (1937), where the Court speak

ing through Mr. Chief Justice H ughes stated:

“ The Declaratory Judgment Act of 1934, in its

limitation to ‘ cases of actual controversy’ manifestly

has regard to the constitutional provision and is

operative only in respect to controversies which are

such in the constitutional sense. The word ‘ actual’

is one of emphasis rather than of definition. Thus

the operation of the Declaratory Judgment Act is

procedural only. In providing remedies and defining

procedure in relation to cases and controversies in

the constitutional sense the Congress is acting within

its delegated power over the jurisdiction of the fed

eral courts which the Congress is authorized to

establish . . . Exercising this control of practice

and procedure the Congress is not confined to tradi

tional remedies. The judiciary clause of the Con

stitution ‘ did not crystallize into changeless form

the procedure of 1789 as the only possible means

for presenting a case or controversy otherwise cog

nizable by the federal courts.’ Nashville, C. & St. L.

Ry. Co. v. Wallace, 288 U. S. 249, 264. In dealing

with methods within its sphere of remedial action

the Congress may create and improve as well as

abolish or restrict. The Declaratory Judgment Act

must be deemed to fall within this ambit of congres

sional power, so far as it authorizes relief which is

consonant with the exercise of the judicial function

in the determination of controversies to which under

the Constitution the judicial power extends.”

The decision in the Aetna case has been uniformly followed.

In one of the latest Circuit Court of Appeals’ decisions,

Trice Products Corporation v. Anderson Co., 147 F. (2d)

721 (C. C. A. 7th, 1945), following this case in upholding

the right to a declaratory judgment in a cross-complaint

in a patent case it was stated:

“ Equity abhors multiplicity of actions and when

it takes jurisdiction for one purpose should do so for

25

all germane purposes and dispose of all issues neces

sary to a complete final adjudication. We agree, there

fore, with the reasoning of the decision cited and with

that of Cover v. Schwarts, 2 Cir. 133 F. 2d 54.”

The Amended Complaint herein alleges that registra

tion is a prerequisite to voting in any election in Alabama;

that appellees are maintaining a policy, custom and usage

of requiring Negro applicants to submit to tests not re

quired of white electors and of refusing to register qualified

Negro electors while at the same time registering white

electors with less qualifications on account of race and color

(R. 5 ); that during the regular registration period while

appellees were conducting registration, appellant presented

himself at the regular registration place and requested to

be registered; that appellant is ready, able and willing to

comply with all lawful requirements for registration; that

instead of registering appellant, appellees required appel

lant to wait long hours and to present two persons to vouch

for him; that although appellant was ready and willing to

answer all questions and give all information necessary

for his registration, appellees illegally and wrongfully re

fused to register him (R. 6) ; that white persons present

ing themselves for registration were not required to wait

or to present persons to vouch for them but were registered

forthwith (R. '6) ; that appellees acting pursuant to policy,

custom and usage set out above denied appellant’s appli

cation and wrongfully refused to register him solely on

account of race and color, and in so doing followed the

general policy custom and usage of the Board of Registrars,

including these appellees and their predecessors in office ■

(R. 6). It is clear that appellant would be entitled to a

declaratory judgment declaring unconstitutional a statute

which would provide that Negro applicants for registration

be required to submit to tests not required of white ap

26

plicants or that white applicants for registration could have

less qualifications than is required of Negroes. The only

allegations necessary to support relief in such a case would

be the statute, qualifications of the applicant and an alle

gation that he was refused registration because of the

statute. In the instant case we do not have such a statute

but have a policy,, custom and usage of a state officer equiva

lent thereto.

The case of Cromwell v. Hillsborough TP of Somerset

County, N. J., 149 F. (2d) 617 (C. G. A. 3d, 1945), aff’d

by U. S. Supreme Ct, Oct. term 1945, decided Jan. 29, 1946,

affirmed the decision of the district court in issuing a decla

ratory judgment against the policy of state officers in

assessing plaintiff’s property higher than like property as

being in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the line of cases on the question of the equalization

of teachers’ salaries it has been uniformly held that Negro

teachers as a class have a right to a declaratory judgment

declaring unconstitutional the practice, custom and usage

of paying Negro teachers less salary than paid to white

teachers, Alston v. School Board, supra; McDaniel v. Board

of Public Instruction, supra, Davis v. Cool, supra.

The allegations in the complaint herein set out a claim

for relief by way of damages and an injunction. There

fore, the same allegations are sufficient to set forth an

actual controversy within the meaning of Declaratory

Judgment Act.

27

V

Action of Appellees in Refusing to Register Appellant

Makes Them Liable to the Appellant for Damages

Under the Provisions of Sections 31 and 43 of Title

8 of the United States Code.

Section 31 of Title 8 provides:

“ Race, color, or previous condition not to affect

right to vote.

“ All citizens of the United States who are other

wise qualified by law to vote at any election by the

people in any State, Territory, district, county, city,

parish, township, school district, municipality, or

other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled' and

allowed to vote at all such elections, without distinc

tion of race, color, or previous condition of servitude;

any constitution law, custom, usage, or regulation of

any State or Territory, or by or under its authority,

to the contrary notwithstanding. R. S. sec. 2004. ’ ’

and Section 43 of Title 8 provides:

“ Civil action for deprivation of rights.

“ Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State

or Territory, subjects or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Con

stitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper

proceeding for redress. R. S. sec. 1979.”

H. R. 1293, 41st Congress, Second Session, which was

later amended in the Senate and which includes Sections 31

and 43 of Title 8, was originally entitled, “ A bill to enforce

the right of citizens of the United States to vote in the sev

eral States of this Union who have hitherto been denied

28

that right on account of race, color or previous condition

of servitude.” When the bill came to the Senate its title

was amended and adopted to read, “ A bill to enforce the

right of citizens of the United States to vote in the several

States of this Union and for other purposes.”

The language of Section 31 is so clear as to leave no

doubt as to its purpose. Section 43 of Title 8 has been used

repeatedly to enforce the right of citizens to vote. See

Myers v. Anderson, supra; Lane v. Wilson, supra.

In the recent decision of Smith v. Allwright, supra, a suit

for damages under these sections was sustained by the

United States Supreme Court. The facts in the instant case

are basically similar to those in the Smith v. Allwright,

supra.

Since registration is a prerequisite to voting, the

refusal of appellees to register appellant and those simi

larly situated solely on account of race and color gives rise

to an action for damages and an injunction under Sections

31 and 43 of Title 8.

CONCLUSION

The present cause of action arises as the result of at

tempts on part of state officers to circumvent the mandate

of the United States Supreme Court in Smith v. Allwright.

It is another of the many efforts to keep Negroes from exer

cising their rights and performing their political duties as

citizens of a democracy by voting and taking part in the

selection of their governmental representatives. Freedom

to exercise such rights and to perform such duties is con

sidered one of the basic virtues and blessings of our politi

cal system and fundamental to our way of life. Action

such as that under present inquiry, therefore, which at

tempts to interfere with that freedom must be declared in

valid if our democratic institutions are to prosper. Wher

29

ever restrictions to the exercise of the voting privilege are

erected based on race and color, whether open or devious,

simple minded or sophisticated, they run counter to our

fundamental law and must be struck down.

Wherefore it is respectfully submitted that this

Court reverse the judgment of the court below dis

missing appellant’s amended complaint.

A rth u r D , S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, No.,

Birmingham 3, Ala.

W illiam H . H astie,

615 F. Street, N. W.,

Washington, D. C.

T htjroood M arsh all ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellant.

R obert L . Carter,

New York, N. Y.

Of Counsel.

[A ppendices F ollow ]

31

APPENDIX A

Constitution of the United States— 1787

ARTICLE I

Section 2.—The House of Representatives shall be com

posed of Members chosen every second Year by the People

of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall

have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most

numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

A m e n d m en t 14

Section 1.—All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens

of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

A m en d m en t 15

Section 1.—The right of citizens of the United States to

vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States

or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condi

tion of servitude.

Section 2.—The Congress shall have power to enforce

this article by appropriate legislation.

A m en d m en t 17

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of

two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof,

32

for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The

electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite

for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legis

latures.

United States Code

Title 8—Section 31—Race, color, or previous condition

not to affect right to vote.

All citizens of the United States who are otherwise quali

fied by law to vote at any election by the people in any

State, Territory, district, county, city, parish, township,

school district, municipality, or other territorial sub-divi

sion, shall be entitled and allowed to vote at all such elec

tions, without distinction of race, color, or previous condi

tion of servitude; any constitution, law, custom, usage, or

regulation of any State or Territory, or by or under its

authority, to the contrary notwithstanding. R. S. Sec. 2004.

Section 43— Civil action for deprivation of rights.

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, sub

jects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United

States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to

the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities se

cured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the

party injured in an action at law, suit in equity or other

proper proceeding for redress. R. S. Sec. 1979.

Title 28—Section 41—Subdivision 11—-Suits for injuries

on account of acts done under laws of United States.—

Eleventh.

Of all suits brought by any person to recover damages

for any injury to his person or property on account of any

act done by him, under any law of the United States, for

33

the protection or collection of any of the revenues thereof,

or to enforce the right of citizens of the United States to

vote in the several States. R. S. Sec. 629.

Subdivision 14—Suits to redress deprivation of civil

rights.—Fourteenth.

Of all suits at law or in equity authorized by law to be

brought by any person to redress the deprivation, under

color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or

usage, of any State, of any right, privilege, or immunity,

secured by the Constitution of the United States, or of any

right secured by any law of the United States providing for

equal rights of citizens of the United States, or of all per

sons within the jurisdiction of the United States. R. S.

Sec. 563.

Title 28—Section 400—Declaratory judgments author

ized; procedure.

(1) In cases of actual controversy (except with respect

to Federal taxes) the courts of the United States shall have

power upon petition, declaration, complaint, or other ap

propriate pleadings to declare rights and other legal rela

tions of any interested party petitioning for such declara

tion, whether or not further relief is or could be prayed,

and such declaration shall have the force and effect of a

final judgment or decree and be reviewable as such.

(2) Further relief based on a declaratory judgment or

decree may be granted whenever necessary or proper. The

application shall be by petition to a court having jurisdic

tion to grant the relief. If the application be deemed suffi

cient, the court shall, on reasonable notice, require any

adverse party, whose rights have been adjudicated by the

declaration, to show cause why further relief should not be

granted forthwith.

34

(3) When a declaration of right or the granting of

further relief based thereon shall involve the determination

of issues of fact triable by a jury, such issues may be sub

mitted to a jury in the form of interrogatories, with proper

instructions by the court, whether a general verdict be re

quired or not.

Title 18—Chapter 3—Offenses Against Elective Fran

chise and Civil Rights of Citizens.

Section 51. Conspiracy to injure persons in exercise of

civil rights.

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress,

threaten, or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or

enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the

Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of

his having so exercised the same, or if two or more per

sons go in disguise on the highway, or on the premises of

another, with intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise

or enjoyment of any right or privilege so secured, they

shall be fined not more than $5,000 and imprisoned not

more than ten years, and shall, moreover, be thereafter

ineligible to any office, or place of honor, profit, or trust

created by the Constitution or laws of the United States.

R. S. 5508.

Section 54. Conspiring to prevent officer from perform

ing duties.

If two or more persons in any State, Territory, or Dis

trict conspire to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat,

any person from accepting or holding any office, trust, or

place of confidence under the United States, or from dis

charging any duties thereof; or to induce by like means any

officer of the United States to leave any State, Territory,

District, or place, where his duties as an officer are required

to be performed, or to injure him in his person or property

35

on account of his lawful discharge of the duties of his office,

or while engaged in the lawful discharge thereof, or to in

jure his property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder, or im

pede him in the discharge of his official duties, each of such

persons shall be fined not more than $5,000, or imprisoned

not more than six years, or both. R. S. 5518.

Section 55. Unlawful presence of troops at polls.

Every officer of the Army or Navy, or other person in

the civil, military, or naval service of the United States,

who orders, brings, keeps, or has under his authority or

control any troops or armed men at any place where a

general or special election is held in any State, unless such

force be necessary to repel armed enemies of the United

States, shall be fined not more than $5,000 and imprisoned

not more than five years. R. S. 5528.

Section 56. Intimidating voters by Army or Navy offi

cers.

Every officer or other person in the military or naval

service of the United States who, by force, threat, intimi

dation, order, advice, or otherwise, prevents, or attempts

to prevent, any qualified voter of any State from freely

exercising the right of suffrage at any general or special

election in such State shall be fined not more than $5,000

and imprisoned not more than five years. R. S. 5529.

Section 57. Army or Navy officers prescribing qualifi

cations of voters.

Every officer of the Army or Navy who prescribes or

fixes, or attempts to prescribe or fix, whether by procla

mation, order, or otherwise, the qualifications of voters at

any election in any State shall be punished as provided in

Section 56 of this title. R. S. 5530.

36

Section 58. Interfering with election officers by Army

or Navy officers.

Every officer or other person in the military or naval

service of the United States who, by force, threat, intimi

dation, order, or otherwise, compels, or attempts to compel,

any officer holding an election in any State to receive a

vote from a person not legally qualified to vote, or who

imposes, or attempts to impose, any regulations for con

ducting any general or special election in a State different

from those prescribed by law, or who interferes in any man

ner with any officer of an election in the discharge of his

duty, shall be punished as provided in section 56 of this

title. R. S. 5531.

Section 61. Intimidating or coercing voters; Presiden

tial and Congressional elections.

It shall be unlawful for any person to intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or to attempt to intimidate, threaten,

or coerce, any other person for the purpose of interfering

with the right of such other person to vote or to vote as he

may choose, or of causing such other person to vote for

or not to vote for, any candidate for the office of President,

Yice President, Presidential elector, Member of the Senate,

or Member of the House of Representatives at any election

held solely or in part for the purpose of selecting a Presi

dent, a Vice President, a Presidential elector, or any Mem

ber of the Senate or any Member of the House of Represen