Lacks v. Feguson-Florissant Reorganized School District, R-2 Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

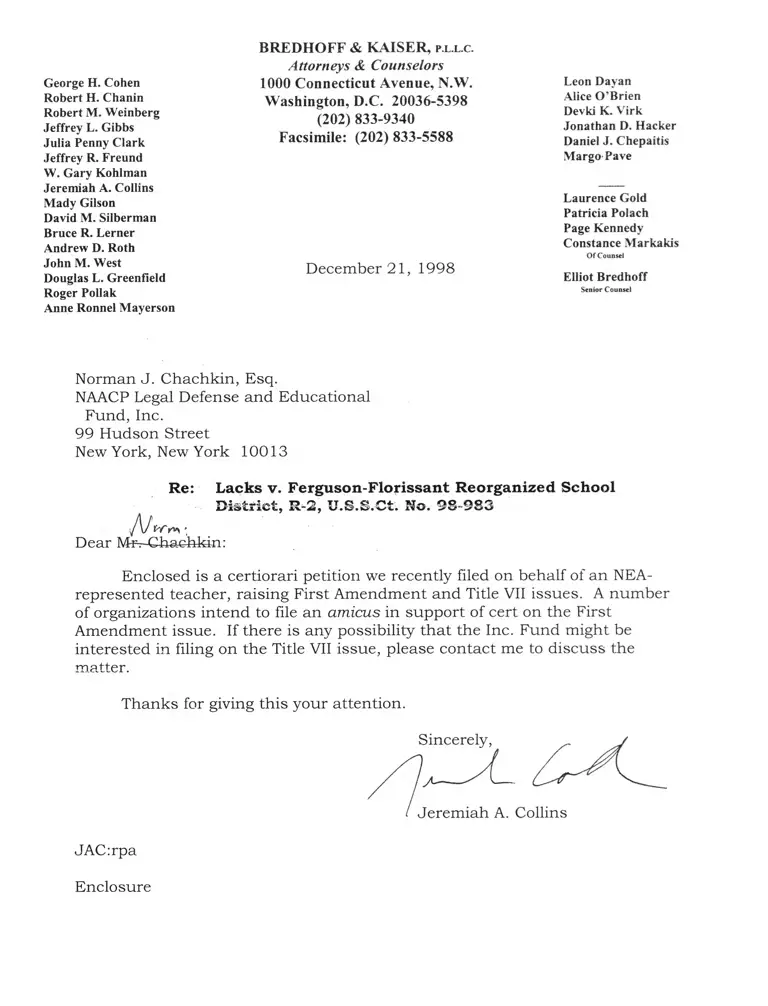

December 21, 1998

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lacks v. Feguson-Florissant Reorganized School District, R-2 Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1998. 28c33f3c-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/695953eb-64f3-4e70-83cd-e1c30fda0cd1/lacks-v-feguson-florissant-reorganized-school-district-r-2-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

George H. Cohen

Robert H. Chanin

Robert M. Weinberg

Jeffrey L. Gibbs

Julia Penny Clark

Jeffrey R. Freund

W. Gary Kohlman

Jeremiah A. Collins

Mady Gilson

David M. Silberman

Bruce R. Lerner

Andrew D. Roth

John M. West

Douglas L. Greenfield

Roger Poliak

Anne Ronnel Mayerson

BREDHOFF & KAISER, p l .l c.

Attorneys & Counselors

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-5398

(202) 833-9340

Facsimile: (202) 833-5588

December 21, 1998

Leon Dayan

Alice O'Brien

Devki K. Virk

Jonathan D. Hacker

Daniel J. Chepaitis

Margo Pave

Laurence Gold

Patricia Polach

Page Kennedy

Constance Markakis

Of Counsel

Elliot Bredhoff

Senior Counsel

Norman J . Chachkin, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 H udson Street

New York, New York 10013

Re: Lacks v. Ferguson-FIorissant Reorganized School

District, R-2, U.S.S.Ct. No. 98-983

J\f tw »> •

Dear Mr—Cha^dikin:

Enclosed is a certiorari petition we recently filed on behalf of an NEA-

represented teacher, raising F irst Am endm ent and Title VII issues. A num ber

of organizations in tend to file an amicus in support of cert on the First

Am endm ent issue. If there is any possibility th a t the Inc. Fund might be

in terested in filing on the Title VII issue, please contact me to d iscuss the

m atter.

T hanks for giving th is your attention.

JAC:rpa

Enclosure

n*53c5«T>

In The

ftupratt? dmtrt of % Ti&mttb ^tato

October T erm , 1998

Cecilia Lacks,

Petitioner,

v.

F erguson-Florissant R eorganized

School D istrict, R-2,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

J eremiah A. Collins *

Leon Dayan

Bredhoff & Kaiser, P.L.L.C.

1000 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 833-9340

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - Epes P r i n t i n g Co., In c . - 789-0096 - W a s h i n g t o n . D.C. 20001

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Where a public school teacher is terminated for

speech that she could not reasonably have understood to

violate a school district policy, is the First Amendment

requirement of reasonable notice satisfied merely because

it is linguistically possible to construe the district’s policy

as prohibiting the speech in question?

2. Where an employee would not have been terminated

but for the racial animus of supervisors who played a

crucial role in the termination process, does the fact that

the ultimate termination decision was made by a body

which was not itself racially motivated preclude holding

the employer liable under Title VII?

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ................ i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ ............ iv

OPINIONS BELOW ................ ............. ............ ................ 1

JURISDICTION....... ....................................................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVI

SIONS INVOLVED.......................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE......................................... 2

A. Overview.................... 2

B. Statement of the Facts.............................................. 4

C. Proceedings in the Eighth Circuit .................... 13

1. The Panel Opinion...... ........... ..................... ......- 13

a. The First Amendment Notice Claim------- 13

b. The Title VII Claim....................................... 14

2. The Dissent from the Denial of Rehearing

En Banc .............................................. 15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT................... 15

I. This Case Raises an Important Question That

Has Divided the Circuits Concerning the Na

ture and Scope of the First Amendment Re

quirement That the Government Must Provide

Teachers With Reasonable Notice as to What

Speech Is Prohibited Before Disciplining Them

for Their Expressive Activities ....... .................. 16

II. This Case Raises an Important Question That

Has Divided the Circuits Concerning Employer

Responsibility Under Title VII for Employment

Actions Infected by Discrimination on the Part

of Supervisors Below the Rank of Final Deci

sionmaker .......... ................................... ..................... 30

CONCLUSION ....... ............ ............ ................................. 30

(hi)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 118 S. Ct.

2257 (1998) .................... 24

City of St. Louis v. Praprotnik, 485 U.S. 112

(1988) ............... 23

Cohen v. San Bernardino Valley College, 92 F.3d

968 (9th Cir. 1996), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 1290

(1997) ..... 19

Cox v. Louisiana (II), 379 U.S. 559 (1965) ____ 20

Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 118 S. Ct. 2275

(1998) .................................... 24

Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent Sch. Dist., 118

S. Ct. 1989 (1998) .... ................... ............. ........... 23,24

Griffin v. Washington Convention Center, 142

F.3d 1308 (D.C. Cir. 1998) ....... ................... . 25, 26

Gusman v. Unisys Corp., 986 F.2d 1146 (7th Cir.

1993) .............. 25

International Society for Krishna Consciousness

v. Eaves, 601 F.2d 809 (5th Cir. 1979) .............. 20

Jett v. Dallas Independent Sch. Dist., 491 U.S. 701

(1989) ....................................................... 23

Keefe v. Geanakos, 418 F.2d 359 (1st Cir. 1969) ..17, 18, 21

Keyishian v. Bocvrd of Regents, 385 U.S. 589

(1967) ................... ............................ ........................ 16, 17

Kramer v. Logan County School District No. R-l,

157 F.3d 620 (8th Cir. 1998) ................................ 29, 30

Mailloux v. Kiley, 448 F.2d 1242 (1st Cir. 1971),

affg 323 F. Supp. 1387 (D. Mass.) ............... ....... 17

Nashville, C. & St. L. Railway v. Browning, 310

U.S. 362 (1940) ............................ ....... ............... 20

Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733 (1974) .... ................. 20

Raley v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 423 (1959) ..... ................. . 20

Roebuck v. Drexel University, 852 F.2d 715 (3rd

Cir. 1988) ....................................... ......................... 25,26

Shager v. Upjohn Co., 913 F,2d 398 (7th Cir.

1990) ............................................................ ............. 27,28

Simpson v. Diversitech, 945 F.2d 156 (6th Cir.

1991) ....... .................. .............................................24, 25, 26

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958) ........... .. 16

iv

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—-Continued

Page

Stachura v. Truzskowski, 763 F.2d 211 (6th Cir.

1985), reev’d and remanded on other issues sub

nom. Memphis Comm. Seh. Dist. v. Stachura,

477 U.S. 299 (1986) ..................................... ..... 17

United States v. Data Translation, Inc., 984 F.2d

1256 (1st Cir. 1992) ............ ................................. 21, 22

Ward v. Hickey, 996 F.2d 448 (1st Cir. 1993)___ 17, 19

Wolf el v. Morris, 972 F.2d 712 (6th Cir. 1992).... 19, 20

STATUTES

28U.S.C. § 1254(1) ................ ......................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1981............................................................. 23

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .................... ...................I...................... 2, 23

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq___________ _____________ 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (a) ......... ..................................... 1

42 U.S.C. §2000e(b )............ ............................ ......... 1

Mo. Ann. St. § 168.114.1....................... ................ ........ 3

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit is reported at 147 F.3d 718 (8 th

Cir. 1998), and is reprinted at App. la-15a. Judge Mc-

Millian wrote an opinion dissenting from the denial of

rehearing en banc, reported at 153 F.3d 904 (8th Cir.

1998) and reprinted at App. 16a-36a. The opinion of

the District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri on

issues decided prior to trial is reported at 936 F. Supp.

676 (E.D. Mo. 1996), and is reprinted at App. 37a-54a.

JURISDICTION

The Court of Appeals entered judgment on June 22,

1998 and denied rehearing and rehearing en banc on Sep

tember 17, 1998. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED'

The First Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion provides in pertinent part that “Congress shall make

no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech.”

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent part that: “[n]o State . .

shall . . . deprive any person of life, liberty, or property

without due process of law.”

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e-2(a), 2000e(b), provides in pertinent part as

follows:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer . . . to discharge any individual, or other

wise to discriminate against any individual with re

spect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or priv

ileges of employment, because of such individual’s

race . . . .

2

The term “employer” means a person engaged in an

industry affecting commerce . . ., and any agent of

such a person.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Overview

Petitioner Cecilia Lacks was an award-winning tenured

teacher who had been employed for more than twenty

years by Respondent Ferguson-Florissant Reorganized

School District (“District”) when the District terminated

her employment on March 23, 1995.

The stated reason for the decision to discharge Lacks

was that she had not disciplined students who, in response

to a drama-writing exercise that Lacks had assigned,

wrote and read aloud in the classroom from scripts in

which the fictional characters created by the students

uttered profanity. According to the District, in refraining

from meting out discipline to the students, Lacks im

properly failed to enforce a prohibition against profanity

set forth in the District’s Student Discipline Code—a pro

hibition that, prior to Lacks’ discharge, had not been

applied or been understood to apply to profanity used in

a work of fiction or creative writing, but only to profanity

that students directed at other persons in real-life inter

actions.

Two claims are at issue in this Petition: (i) a First

Amendment claim brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983,

on the theory that the termination was unconstitutional

because Lacks was not on reasonable notice that the ex

pressive activity for which she was terminated was pro

hibited by District policy;1 and (ii) a Title VII claim 1

1 In addition to the First Amendment claim that is the subject

of this petition, Lacks also presented to the jury a distinct First

Amendment claim predicated on the theory that, even if she had

received adequate notice, the District’s decision to terminate her

was not reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns. The

jury decided in her favor on this claim, but the Eighth Circuit set

the verdict aside. App. lla-12a. Certiorari is not sought as to this

issue.

3

Drought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., on the

theory, inter alia, that supervisors who played crucial roles

in the termination process were motivated by racial ani

mus, and but for that racial animus, Lacks would not

have been terminated.2

Both the First Amendment notice claim and the Title

VII race discrimination claim were tried to a jury. On

the notice claim, the jury found in favor of Lacks, an

swering “no” to a special interrogatory that asked, “Did

plaintiff have reasonable notice that allowing students to

use profanity in their creative writing was prohibited?”

On the Title VII claim, the jury was asked (i) whether

Lacks had proven “by a preponderance of the evidence”

that “plaintiff’s race was a motivating factor in her termi

nation,” and (ii) whether the defendant had “proven by

the preponderance of the evidence that defendant would

have discharged Lacks regardless of her race.” The jury

decided in Lacks’ favor on both questions, answering the

first question “yes,” and the second question “no.”

The District Court entered judgment for Lacks on these

claims in accordance with the jury’s verdict. The Eighth

Circuit, for reasons set forth infra at 13-14, reversed and

ordered that judgment notwithstanding the verdict be en

tered in favor of the District. Petitioner requested rehear

ing en banc, which the Eighth Circuit denied over the

dissent of Judges Theodore McMillian and Morris Shep

pard Arnold.

2 Lacks also brought a state-law claim that her discharge violated

the Missouri Teacher Tenure Act, Mo. Ann. St. § 168.114.1. The

District Court decided that claim in her favor, see App. 44a-48a,

but the Eighth Circuit reversed. App. 6a-9a. Lacks does not peti

tion for certiorari as to that claim.

This action originally was filed in state court but was properly

removed by respondents. App. 5a.

4

B. Statement of the Facts 3

1. In October 1994, Lacks gave the students in her

eleventh grade English class, who were studying a unit on

drama, an assignment that required four groups of students

to write plays about themes that were important to them,

using dialogue natural to the characters created. Tr.

410.4 The students were then to read in the classroom

from the scripts they had written, and those classroom

presentations were to be videotaped so that the students

could see themselves speak and thereby work to improve

their oral presentation skills. Tr. 416.

Lacks did not encourage the students to use profanity

in the plays. Tr. 411. However, three of the four student

groups prepared scripts touching on themes such as gang

violence and inter-gang romances, and those scripts con

tained a great deal of profanity, including the word “fuck,”

as well as frequent uses of the word “nigger.” 5 At least

in part, the students were writing on matters known to

them from experience. Karen Price, the Chairman of

the English Department at Berkeley High School, where

Lacks taught, testified that “many of our students have

experienced violence in their lives. I personally know

that in real life, one of the students on the video was

arrested on a drug charge. In real life, one of the male

students witnessed a random shooting of a child by warring

gangs.” Tr. 953.

3 Because the two claims at issue were decided in Lacks’ favor by

a jury, the court below acknowledged that, on review, the court

was required to credit the testimony of Petitioner’s witnesses and

to accept as true all of the evidence adduced at trial that was

favorable to Petitioner. App. 13a. We do the same in this State

ment of Facts,

4 We cite to the trial transcript as “Tr.,” and to the transcript

of the School Board hearing as “Hrg. Tr.” Trial Exhibits are cited

as “Exh.,” and exhibits introduced at the School Board hearing are

cited as “Hearing Exh.”

5 All of the students in Lacks’ English class were African-

American, as was 98% of the student body of Berkeley High

School. Tr. 1401.

5

2. A District policy— Policy 3043—required “all em

ployees of the district,” including teachers, to “share re

sponsibility for supervising the behavior of the students

and for seeing that they meet the standards of conduct”

set forth in the District’s “Student Discipline Code.” Exh.

96 at 55.

The Student Discipline Code prohibited “[s jtudent be

havior that is disorderly or unacceptable,” and it listed

the following examples of such “behavior”:

tardiness, unexcused absence, leaving school grounds

without permission, cheating, fighting, theft, gam

bling, use of tobacco products in unauthorized areas,

forgery, littering, profanity, insubordination, refusal

to identify self to school officials, verbal abuse, re

fusal to comply with directions of staff, class disrup

tion, inappropriate dress, obscene gestures, lying to

school authorities, inappropriate physical contact be

tween students, possession of glass bottles, and any

other inappropriate behavior as defined by school

officials.

Id. at 109.

3. Prior to Lacks’ case, there were numerous instances,

occurring over a period of many years while the Student

Discipline Code was in effect, in which high school stu

dents in the District, with the awareness of District ad

ministrators, had used profanity in their creative writing.

There were no cases, however, in which a District admin

istrator had ever suggested that the Student Discipline

Code applied to profanity in that context, much less were

there any cases in which the District had imposed any

discipline, either on the students involved or on the

teachers.

On at least two earlier occasions, students in Lacks’

classes had read poetry containing profanity, including

the word “shit” and the word “nigger,” in the presence of

a school administrator, who did not raise any objection.

Tr. 505-06, 512-13, 841. Indeed, on one of those occa

sions the administrator wrote a positive evaluation of the

day’s lesson, stating that the lesson was “effective and in

6

teresting” and that he “was impressed by the fact that the

students were not reluctant to share their writing,” which

he attributed to the “supportive atmosphere [Lacks] cre

ated in the class.” Tr. 513. On another occasion, one of

Lacks’ students wrote a short story containing profanity,

and, despite the profanity, the story was displayed without

objection on the library wall. Tr. 378-79.

On still another occasion, a student of another teacher

in the District wrote a play called “Everything You Al

ways Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to

Try,” and named the characters Freddy Fuck, Peter Prick,

Sally Slut, and Penny Prude. Tr. 2043-44. The assistant

principal read the play and “just laughed about it”; he

disciplined neither the student nor the teacher. Tr. 2044.

(The teacher had given the student an “A” grade for the

play.)

In addition, Vernon Mitchell, the principal of Berkeley

High School and the person who initiated the disciplinary

proceedings against Lacks, did not discipline the students

or the teacher involved in a 1992 student-written school-

sponsored play that, by Mitchell’s own admission, contained

profanity; on the contrary, Mitchell went on stage to

publicly congratulate the students and the teacher after

a performance of the play for parents and the community

at large. Tr. 1380, 1383-86. In addition to profanity, that

play, called “How Ya Livin’,” contained a depiction of a

gang member desecrating the body of a victim of violence,

as well as sexually suggestive dancing and a scene featur

ing a student actor lewdly pulling on his crotch and re

ferring to it as his “thang.” Exhs. 247, 248. The teacher

who sponsored “How Ya Livin’,” Sharita Kyles, is an

African-American, as is Mitchell. Lacks is white.

4. It was undisputed that Lacks diligently enforced the

Student Discipline Code when she encountered students

using profanity in their interactions with others. Tr. 451-

52, 1037. But the understanding not only of Lacks, but

of other District teachers prior to Lacks’ case, and of

administrators as well, was that the Student Discipline

Code did not apply to profanity used by students in their

creative writing.

Thus, Karen Price, the Chairman of the English De

partment at Berkeley High School, testified as follows in

response to a question asking her to state her understand

ing of the Student Discipline Code:

A. I did not think it was related to creative writing

or reading of literature. I thought it had to do with

student behavior.

Q. Would you say that a student writing creative

writing in the classroom no matter what language is

contained in the writing, do you feel that student

would be necessarily misbehaving because they in

clude street language?

A. I don’t think they are misbehaving.

Q. What do you think they are doing?

A. I think that they are trying to put words in a

character’s mouth that reflect what kind of person

they are writing about. . . .

Q. Have you ever known of a teacher to be disci

plined for what was contained in a student’s creative

writing?

A. No.

Q. Or for profanity or street language contained in

the student’s creative writing in the classroom.

A. Never.

Tr. 963-64 (emphasis added).

Two District administrators testified to the same effect.6

Indeed, the only person who claimed to believe that the

6 Dr. Larilyn Lawrence, the District’s Curriculum Coordinator

for Reading and Language Arts, testified as follows:

Q. . . . [A] re you aware of any policy or rule in the Ferguson

Florissant School District that prohibits teachers in the class

room from allowing students to include street language in their

creative writing?

A. No, I am not.

# * * *

7

[Continued]

8

Student Discipline Code applied to profanity in students’

classroom works was one of the administrators who made

the decision to bring the Policy 3043 charge against

Lacks. That administrator, Barbara Davis, stated that, as

she read the Student Discipline Code, it prohibited a stu

dent even from reading profanity aloud from a recognized

work of literature as part of a classroom assignment. Tr.

1700; see also Hrg. Tr. 792. Davis admitted, however,

that the Code never had been applied in the context of

any classroom assignment prior to Lacks’ case. Tr. 1701.

5. The methodology according to which Lacks taught

creative writing at Berkeley High School was one that she

had employed during her entire career with the District—

a methodology that, throughout that time, the District it

self had endorsed and recommended to teachers of crea

tive writing both within the District and nationwide. Tr.

345-46, 348, 350. Referred to at trial as the “student-

centered” method, and originally developed in the 1960’s

by noted educator James Moffett, this method’s central

tenets, as summarized in guidelines distributed to teachers

by the District, are as follows:

Don’t tell writers what should be in their [creative]

writing or worse, write on their pieces. Build on

what writers know and have done, rather than be- 6

6 [Continued]

Q. Well, how is a student including a piece of street language

or profanity in creative writing, do you think, how does the

Student Discipline Code apply to that?

A. I just don’t think it does. We’re talking about here an

assignment where you’re creating characters, and in order to

create them, if you need to use the language, the setting, the

situations that those characters are in, then you create a

script, a play, and that is, I suppose, no different than writing

an essay. It’s a special kind of an assignment. I t’s not just

the back and forth of kids in the classroom without any assign

ment attached.

Tr. 1263-65.

Dolores Graham, who served as a principal in the District for

more than eleven years and as an assistant principal for longer,

gave similar testimony. Tr. 1098-99.

9

moaning what’s not on the page, what’s wrong with

what is there. Resist making judgments about the

writing.

Tr. 348; Exh. 195, pp. 4-5.

As Lacks explained at trial, this method dictates that

the teacher should not attempt to control the content and

language of student creative works—particularly students’

initial creative efforts—

[bjecause from the research and from information

even in our own curriculum, students shut down

when a teacher starts making judgments about the

content. The students simply decide that they are

writing then for the teacher, and the whole concept

of voice that I talked about before just totally dis

appears. Students think they have no voice.

Tr. 351.

Lacks recounted a specific example of how, during the

1992-1993 school year at Berkeley, her use of the student-

centered method led one student, Reginald, to progress

during the semester from total non-participation in class

room activities, to initial efforts at poetry that were highly

disjointed and laden with profanity, to composing accom

plished poems without profanity, including a poem that

won the highest district-wide award for student poetry.

Tr. 367J

Expert witness testimony—including testimony from

the Executive Director of the National Council for Teach

ers of English—established that the student-centered

method is widely used with success in secondary schools

throughout the country, Tr. 1106, 1114-18, and that it is

not unusual to see, particularly in first attempts at creative

writing, profanity of the kind that appeared in the video- 7

7 Judge McMillian’s opinion dissenting from the order denying

en banc rehearing in this case sets forth in full three of Reginald’s

later poems, including the award-winning poem, and quotes exten

sively from the trial testimony concerning how Lacks’ teaching

method was successful in improving Reginald’s writing and getting

him past the use of profanity. App. 23a-33a.

10

taped student drama exercises written by Lacks’ students.

Tr. 1181. One expert in student play-writing, when asked

about her reaction to the videotape, stated that “[tjhere

was nothing surprising in that. The language was appro

priate for the characters, and this is language that we

have seen in classrooms across the country.” Tr. 1181.

6. The disciplinary process that led to Lacks’ termina

tion was initiated by Principal Vernon Mitchell, who

learned of the existence of the videotaped drama exercise

in January, 1995, three months after the exercise had

taken place. As Mitchell admitted at trial, he saw the

drama exercise from the outset of his investigation in

racial terms, viz, as “black students acting a fool and

white folks videotaping it.” Tr. 1392. Mitchell testified

that he used those words when he was telling one of

Lacks’ African-American students, Everette, what it was

that had “offended” Mitchell about the incident. Tr.

1393*

Quite apart from his reaction to the videotape, there

was evidence that Mitchell “had displayed signs of hos

tility to white teachers at Berkeley because Mitchell be

lieved that some white teachers did not care about the

students.” App. 13a. See also Tr. 1492 (testimony from

School Board member that there had been “several” com

plaints from teachers to the effect that Mitchell was prej

udiced against white teachers). And, as we have noted,

Mitchell did not take any adverse action against Sharita

Kyles, the African-American teacher who sponsored the

production of “How Ya Livin’,” the student-written play

that contained profanity and obscene gestures.8 9

8 Mitchell used similar racial terminology when speaking about

the incident with District Curriculum Coordinator Larilyn Law

rence. Tr. 1269.

9 The record also reflects that, in the spring of 1994, an African-

American substitute teacher, John Mitchell (who, unbeknown to

Lacks, was Vernon Mitchell’s nephew) showed a Louis Farrakhan

videotape to Lacks’ class and made anti-semitic remarks directed

in part at Lacks, whom Mitchell knew to be -Jewish. Tr. 495. In

response to an assignment from Lacks to write a journal entry

11

As the Eighth Circuit stated in the decision below,

there was evidence at trial that the District’s Assistant

Superintendent for Personnel, John Wright, who also was

African-American, likewise viewed the videotaping inci

dent in racial terms. App. 13a. It was Wright who con

ducted an investigation of the taped drama exercises after

Mitchell brought the matter to his attention, and Wright

drafted the charges against Lacks that were presented to

the School Board.

7. Under the Missouri Teacher Tenure Act, Lacks had

a right to a pre-termination hearing before the School

Board, and she exercised that right by requesting a hear

ing.

At the beginning of the hearing, the District announced

that it was pursuing just one charge of misconduct: that

Lacks had willfully violated School District Policy 3043

by failing to enforce the Student Discipline Code to dis

cipline students who used profanity in their creative

works.10 It was undisputed at the hearing, and it has

relating to the day that the substitute teacher was present, a stu

dent wrote a paper which said:

We read out loud about Louis Farrakhan and how the white

people and the Jews tried to persecute them. But Louis

wouldn’t have it so he told them honkies and them Jews and

them chinks that if they mess with his people, he mess with

them, and also, Louis Farakhan [sic] believed that all white

peoples are devils, and I agree, because all they want to do is

use you for their own use. But check this, I ever seen a white

or a Jew touch me, I ’m going to kill the monkey crackers and

them chinks because I hate them all. And another thing, I

don’t care what Hitler did to you. That was in Russia, and

this is the U.S., and they love you all and hate us. Tr. 495.

Upon receiving this piece of writing, Lacks showed it to Mitchell

and explained the circumstances under which it had been created.

Tr. 496. Despite the profanity and racial hatred conveyed in the

piece, Mitchell did not suggest that either the student or the sub

stitute teacher be disciplined, Tr. 498, 501, nor in fact were they.

to The District’s case was focused on the videotaped drama exer

cises, but the District also contended that Reginald’s initial poems,

see supra at 9, written in the 1992-1993 school, year, constituted

12

remained undisputed, that, under Missouri law, for a

school district to terminate a tenured teacher on such a

ground, it is necessary for the district to establish a “will

ful” violation of a written regulation, which, in the case

of Lacks, meant that the District had to prove “that Lacks

violated the board policy prohibiting profanity, and that

she knew that the board policy applied to the profanity

used by her students.” App. 6a (emphasis added).

At the Board hearing, as at trial, Lacks testified that

she did not believe that the Student Discipline Code ap

plied to profanity in student creative works, that no one

had ever suggested to her that the Code was applicable

in that context, and that she had never heard of any

instance in which any student had been disciplined for

using profanity in that context, let alone any teacher for

allowing it. Hrg. Tr. 484, 630-31. And, as at trial, Lacks

called to the stand teachers and administrators who testi

fied that they likewise had not understood it to be a viola

tion of any policy for a teacher to permit students to use

profanity in their creative writing. Hrg. Tr. 813, 823,

845; see also App. 44a-47a. Lacks also introduced evi

dence regarding Principal Mitchell’s disparate treatment

of her and Sharita Kyles, Hrg. Tr. 212, 215, and

Mitchell’s statement that what offended him about the

videotape of Lacks’ students was that it was “black stu

dents acting a fool and white folks videotaping it.” Hrg.

Tr. 221.

In its written decision terminating Lacks, the only evi

dence cited by the Board in support of its finding that

Lacks’ violation was “willful” was Mitchell’s testimony

regarding warnings he claimed to have given Lacks in

her capacity as faculty sponsor of the school newspaper,

concerning the use of profanity in the paper. Exh. 217.

Mitchell’s testimony on this subject was impeached in the

Board hearing and was thoroughly discredited at trial.11 * ll

violations of the Student Discipline Code, and that Lacks should

have disciplined Eeginald for writing those poems.

l l In the Board hearing, Mitchell testified that he had warned

Lacks about the use of certain words in the newspaper; yet the

But in any event, Mitchell did not even contend that he

had told Lacks that students’ use of profanity in the

newspaper—or in other written work—would constitute

a violation of the Student Discipline Code}2

Although, as noted, Lacks raised the issue of Mitchell’s

racial bias at the hearing, the Board members “never dis

cussed any alleged racial discrimination” in their delibera

tions. App. 14a.

C. Proceedings in the Eighth Circuit

1. The Panel Opinion

a. The First Amendment Notice Claim

The jury answered “no” to the question whether Lacks

had “reasonable notice that allowing students to use pro

fanity in their creative writing was prohibited.” App. 9a.

The Eighth Circuit, however, held that the jury was re

quired to answer “yes.” In so holding, the Eighth Circuit

specifically acknowledged that the jury was free to dis

believe Mitchell’s testimony that he had warned Lacks 12

newspapers were introduced into evidence, and they did not contain

any of the words Mitchell cited. See Hrg. Exh. 14. Mitchell’s

memoranda to Lacks concerning the newspaper also were in evi

dence at the Board hearing, and they made no mention of any con

cern about profanity. See Hrg. Exhs. 36, 37. At trial, Mitchell

was forced to admit that his testimony before the Board about

the newspapers was inaccurate. Tr. 1363.

12 The District had a separate policy, applicable only to the news

paper, which broadly required the newspaper’s faculty advisors to

“monitor style, grammar, format, and appropriateness of mate

rials,” and to “edit material considered obscene [or] libelous.”

Exh. 96; 46a-47a n.l. If what Mitchell claimed to have told Lacks

•—viz., that it was “inappropriate” for the student newspaper to

include “profanity . . ., negative reflections on teachers, things like

that,” Hrg. Tr. 174—could be understood as a reference to any

particular policy of the District, that policy was the one applicable

to the editing of the student newspaper, not the Student Discipline

Code. See Hrg. Tr. 184-85 (testimony of Vernon Mitchell) (what

Mitchell “mentioned about the paper [was] not only the profanity

but just the inappropriateness of the materials”) ; Hrg. Tr. 174,

175, 178, 179, 182, 190-91, 240.

14

about profanity that he claimed had appeared in the

school newspaper. App. 11a. Notwithstanding that—

and notwithstanding the evidence canvassed above show

ing that, prior to Lacks’ case, the Student Discipline Code

had been understood by teachers and District administra

tors as having no application to student creative works—

the court of appeals held “as a matter of law” that, be

cause the language of the Student Discipline Code “con

tains no exception for creative activities,” App. 10a,

Lacks “took the risk that the board would enforce the

policy as written.” App. 11a.

b. The Title VII Claim

The Eighth Circuit also overturned the jury’s verdict

in favor of Lacks on her Title YII claim. In so doing,

the court acknowledged that the jury properly could have

concluded that Principal Mitchell and Assistant Super

intendent Wright were motivated by race in pressing

charges against Lacks. App. 13a. And the court ac

knowledged that the jury properly could have found that

Mitchell was lying when he testified to the Board that

he had warned Lacks about profanity in the school news

paper. App. 11a. That testimony, as the court further

acknowledged, was explicitly relied upon by the Board

in finding that Lacks acted with the “willfulness” neces

sary to sustain the termination of a tenured teacher for

misconduct under Missouri law. App. 8a. Indeed, it was

undisputed that the Board relied on no evidence other

than Mitchell’s testimony to establish that point.

But the Eighth Circuit held that the jury’s verdict that

Lacks was terminated because of her race could not

stand, because “Mitchell and Wright did not make the

decision to terminate Lacks; that decision was made by

the school board.” App. 13a. The court found it disposi

tive that neither Mitchell nor Wright made any specific

“recommendaftion]” in the Board hearing, and “the board

made an independent determination as to whether Lacks

should be terminated and did not serve merely as a con

duit for the desires of school administrators.” App. 13a-

14a.

2. The Dissent From the Denial of Rehearing En Banc

Judge MeMillian and Judge Morris Sheppard Arnold

dissented from the Eighth Circuit’s denial of rehearing en

banc. In Judge McMillian’s opinion in support of en banc

rehearing, he reasoned that the Student Discipline Code

“was not explicit with respect to [prohibiting profanity

in] classroom creative assignments,” and that, “in light of

evidence that profanity in other student creative works—

including one student-written play—was apparently con

doned,” it could not fairly be concluded as a matter of

law that Lacks was on reasonable notice that “the pro

fanity prohibition applied to creative writing assignments.”

App. 22a. As Judge MeMillian saw it, upholding the

termination of Lacks based on invocation of the Student

Discipline Code in these circumstances implicated “issues

of exceptional importance,” App. 16a, because a legal

regime that would permit a teacher to be fired for trans

gressing a policy that she justifiably “never even knew

was there” would threaten to chill all teaching that might

prove controversial, and would thereby threaten to

“scare[] away” “all innovative and well-meaning teachers.”

App. 34a, 36a.

Judge MeMillian emphasized that he would have “no

quarrel with a school policy that clearly and strictly pro

hibits students from using profanity in all school-related

activities,” including creative writing, but he concluded

that the District here did not have such a policy, and

therefore Lacks was, in essence, terminated because she

did not “pick [her] way through a mine field of compet

ing and conflicting expectations, and changing and elusive

legal standards.” App. 35a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This case raises two recurring issues of exceptional im

portance as to which this Court has not spoken and as

to which the courts of appeal have issued inconsistent,

and in some instances directly contradictory, decisions.

The first question involves the nature and scope of the

First Amendment doctrine that requires reasonable notice

15

16

before the government may punish a person—particularly

a public school teacher—for her speech. The second

question is that of employer liability under Title YII for

an employment decision made by high level managers

who are not themselves motivated by racial animus, but

whose decision is brought about by the racial animus of

other agents of the employer. Both questions, squarely

presented in this case, warrant review by this Court.

I. This Case Raises an Important Question That Has

Divided the Circuits Concerning the Nature and Scope

of the First Amendment Requirement That the Gov

ernment Must Provide Teachers With Reasonable

Notice as to What Speech Is Prohibited Before Dis

ciplining Them for Their Expressive Activties.

1. This Court long has held that, “ ‘because First

Amendment freedoms need breathing space to survive,’ ”

the government may not penalize someone from engaging

in speech unless it has provided notice sufficient to “clearly

inform” the person as to what speech is prohibited.

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 604

(1967) (quoting N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415,

438 (1963)). In Keyishian, the Court held that this re

quirement of fair notice must be enforced with particular

vigilance in cases involving the discipline of teachers,

because

Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding

academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to

all of us and not merely to the teachers concerned.

That freedom is therefore a special concern of the

First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that

cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.

* :f: * *

When one must guess what conduct or utterance

may lose him his position, one necessarily will “steer

far wider of the unlawful zone . . . .” Speiser v.

Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 526 [(1958)]. For “[t]he

threat of sanctions may deter . . . almost as potently

as the actual application of sanctions.” N.A.A.C.P.

v. Button, supra, at 433. The danger of that chilling

17

effect upon the exercise of vital First Amendment

rights must be guarded against by sensitive tools

which clearly inform teachers what is being pro

scribed.

385 U.S. at 603-04.

Although Keyishian involved the rights of faculty mem

bers of public colleges, subsequent decisions have held

that the requirement of clear notice applies equally to dis

ciplinary actions taken against high school teachers for

expressive activities. Shortly after Keyishian was decided,

the First Circuit held in a pair of cases that the notice re

quirement is essential in both settings. See Keefe v.

Geanakos, 418 F.2d 359, 362-63 (1st Cir. 1969);

Mailioux v. Kiley, 448 F.2d 1242, 1243 (1st Cir. 1971),

aff’g 323 F. Supp. 1387, 1392 (D. Mass.) (Wyzanski,

J.). More recently, the First Circuit reaffirmed its hold

ings on this subject in Ward v. Hickey, 996 F,2d 448,

453-54 (1st Cir. 1993). And other courts as well have

held that the notice requirement applies in the high school

setting. See, e.g., Stachura v. Truzskowski, 763 F.2d 211,

215 (6th Cir. 1985), rev’d and remanded on other issues

sub nom. Memphis Comm. Sch. Dist. v. Stachura, A ll

U.S. 299 (1986).

2. The Eighth Circuit purported to apply the notice

requirement in this case, App. 10a, but the court in fact

cut the heart out of the doctrine, and adopted an ap

proach directly at odds with that of other circuits, by

treating the notice inquiry as an abstract exercise in

linguistics that can be performed by examining a partic

ular regulation in a vacuum.

As we have noted, the jury specifically found that

Lacks did not have “reasonable notice that allowing stu

dents to use profanity in their creative writing was pro

hibited.” The jury reached that result on a record that is

replete with evidence that District administrators had reg

ularly tolerated, and even applauded, student works that

contained profanity, and that neither teachers nor admin

istrators had understood the Student Discipline Code as

applying to students’ creative writing. See supra at 5-8.

18

The court of appeals did not deny that the record con

tained such evidence; and the court acknowledged that

the jury was free to discredit the only testimony that, if

believed, might tend to establish that Lacks was on notice

that profanity was prohibited in student writing—the testi

mony of Principal Mitchell concerning alleged use of pro

fanity in the student newspaper. App. 11a. But the court

dismissed all of the evidence of how the District’s policy

had in fact been understood and applied, saying:

Even so, the policy against profanity was explicit. . . .

In acting as [Lacks] did, she took the risk that the

board would enforce the policy as written.

App. 11a.13 The Eighth Circuit thus held that, “as a mat

ter of law,” App. 9a, the First Amendment notice require

ment is satisfied as long as a written policy can linguisti

cally be construed to prohibit the expressive activity at

issue, no matter how strong the evidence may be that the

individual who has been punished could not reasonably

have understood the policy to be applicable.

This holding creates a square conflict with the First

Circuit’s decisions regarding the notice doctrine. In

Keefe, for example, a school district sought to terminate

a teacher for assigning to a class of high school students

a magazine article containing the word “motherfucker”

and for leading a classroom discussion in which the

teacher said the word aloud. The school district claimed

that the teacher was on notice that his conduct was pro

hibited because there was a regulation in place that pro

vided that “[tjeachers shall use all possible care in safe

guarding the health and moral welfare of their pupils,

discountenancing promptly and emphatically: vandalism,

falsehood, profanity, cruelty, or other form of vice.” 418

F.2d at 362 n.10. The First Circuit determined never

theless that the teacher was not on reasonable notice, be

cause profanity had been tolerated in other educational

13 See also App. 10a (“The Student Discipline Code clearly pro

hibits profanity and obscene gestures, and it contains no exception

for creative aetivites,”)

19

contexts at the school and because the regulation did not

appear to be “apposite” to the conduct at issue. Id. at

362.

Thus, as the First Circuit recently reaffirmed in Ward,

that Circuit takes the view that “t[h]e relevant inquiry is:

based on existing regulations, policies, discussions, and

other forms of communication between school administra

tion and teachers, was it reasonable for the school to

expect the teacher to know that her conduct was pro

hibited?” 996 F.2d at 454 (emphasis added).

The Eighth Circuit’s decision here also is in conflict

with the decision of the Ninth Circuit in Cohen v. San

Benardino Valley College, 92 F.3d 968 (9th Cir. 1996),

cert, denied, 117 S. Ct. 1290 (1997). There, the court

held that it was impermissible under the First Amendment

for officials of a public college to apply a “[pjolicy’s

nebulous outer reaches to punish teaching methods that

[the teacher] had used for many years,” when those meth

ods “had apparently been considered pedagogically sound

and within the bounds of teaching methodology permitted

at the College” prior to the adverse employment act at

issue. Id. at 972. In reaching that conclusion, the Ninth

Circuit did not suggest that the college’s policy was by its

terms inapplicable to the teacher’s speech.

Cases in other contexts besides public education also

have rejected the Eighth Circuit’s notion that, where First

Amendment activity is at issue, a person must “t[ake]

the risk that the [government] would enforce [a] policy

as written,” App. 11a, regardless of the circumstances

that would lead a reasonable person to think that the

policy would not be so applied. Indeed, the approach

taken by the court below has been rejected even in the

prison context, where the notice doctrine is most circum

scribed. Thus, in Wolf el v. Morris, 972 F.2d 712 (6th

Cir. 1992), the Sixth Circuit held that, although a prison

regulation required inmates to obtain prior approval from

the warden before commencing any “group organizing

activity,” prison officials transgressed the notice require

20

ment when they disciplined inmates who had circulated a

petition without obtaining such approval, because, at the

prison in question, “inmates . . . ha[d] been allowed to

circulate numerous petitions over the years while the rele

vant regulations were in force” without obtaining prior

approval, and the plaintiffs therefore “had no reason to

believe that they were engaging in activity prohibited by

prison regulations when they circulated the petitions.” Id.

at 717.

The Fifth Circuit likewise has held that actual enforce

ment practices under a government regulation or policy

must be considered in determining whether an individual

was on reasonable notice that her expressive activities

might be found to constitute a violation, even where the

terms of the regulation or policy might appear to prohibit

those activities:

Over time—indeed, probably fairly quickly—certain

patterns of enforcement and tacit understandings will

develop. This “less formalized custom and usage,”

Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733, 754 (1974), will

clarify much of the inevitable imprecision. Supreme

Court decisions strongly suggest that the authorities

will not be permitted to prosecute conduct permitted

by those understandings, see, e.g., id.; Cox v. Louis

iana (II), 379 U.S. 559, 568-73 (1965); Raley v.

Ohio, 360 U.S. 423 (1959), even if it is apparently

proscribed by the ordinance itself. “Deeply embedded

traditional ways of carrying out state policy . . . are

often tougher and truer law than the dead words of

the written text.” Nashville, C. & St. L. Ry. v.

Browning, 310 U.S. 362, 369 (1940).

International Society for Krishna Consciousness v. Eaves,

601 F.2d 809, 831 (5th Cir. 1979) (emphasis added).

3. The essential fallacy that underlies the Eighth Cir

cuit’s contrary reasoning is the notion that, when a par

ticular regulation or prohibition contains “no exceptions,”

it naturally should be read to apply to every activity that

conceivably could be covered by its literal language.

Even putting aside First Amendment concerns—and even

21

in the absence of evidence regarding the actual applica

tion and interpretation of a policy such as was presented

in this case—that is not always the natural way to read

a regulation. As then-judge Breyer explained in United-

States v. Data Translation, Inc., 984 F.2d 1256, 1261

(1st Cir. 1992):

Exaggerating to explain our point, we find the Gov

ernment’s interpretation a little like that of, say, a

park keeper who tells people that the sign “No Ani

mals in the Park” applies literally and comprehen

sively, not only to pets, but also to toy animals,

[and] insects. . . . If one met such a park keeper,

one would find his interpretation so surprisingly broad

that one simply would not know what he really

meant or what to do.

In the present case, a teacher reading a Disciplinary

Code applicable to student “behavior,” and covering such

matters as “theft, gambling . . ., littering . . . [and] pos

session of glass bottles,” see supra at 5, cannot fairly

be expected to assume—-in the face of extensive contrary

evidence—that classroom creative writing is part of the

“behavior” addressed by the Code.

Whatever may be true in other contexts, where the issue

of notice arises in the context of First Amendment activity,

the Eighth Circuit’s approach is entirely out of place,

and cannot be reconciled with the teaching of Keyishian

and the holdings of other circuits. The crucial under

standing that has guided this Court’s recognition of rea

sonable notice as a First Amendment requirement, par

ticularly in the sphere of public education, is the impor

tance of ensuring that individuals not be induced by fear

of possible penalties to “steer far wider of the unlawful

zone” than the government actually intends or may prop

erly demand. Keyishian, 385 U.S. at 604, quoting

Speiser, 357 U.S. at 526. One circumstance in which

that problem comes to the fore is where, as in Keyishian,

a regulation uses vague terms. But the same problem can

arise from “the exhaustiveness of the . . . language [of a

22

policy if read] literally,” Data Translation, 984 F.2d at

1261, particularly where the government’s actual enforce

ment of the policy suggests a narrower applicability than

a literal reading of the policy might permit. If an indi

vidual confronted with a vague policy, or with a policy

that has not been applied literally, is subject to punish

ment unless he or she acts in accordance with the most

expansive possible reading of the policy, the result will be

the very chilling effect that the First Amendment notice

requirement seeks to prevent.

4. The context in which the notice issues arises in this

case is both a recurring one and one that provides a par

ticularly cogent illustration of the point just made. The

Student Discipline Code involved in this case is a garden-

variety code of student conduct such as exists in virtually

every school district. See supra at 5 (quoting text of the

Code). It certainly is not the case that every school dis

trict that prohibits swearing in the hallways would wish

to have its teachers discipline students for any and all

use of profanity in their creative works: undoubtedly

many districts would agree with the testimony of the Ex

ecutive Director of the National Council for Teachers of

English, Tr. 1106, 1114-18, that such an approach would

be educationally unsound. Yet the plain import of the

Eighth Circuit’s decision is that, in every school district

that has a student discipline code, a teacher “t[akes] the

risk” of punishment if she does not treat classroom cre

ative writing as subject to the same prohibition of the use

of profanity as applies to hallway cursing.

Thus, the Eighth Circuit’s ruling on the notice issue

conflicts with the decisions of other circuits, and, if not

reversed by this Court, is likely to induce teachers across

the country to “steer far wider of the unlawful zone” by

prohibiting or punishing student speech that, in many

instances, school officials would not actually wish to pro

hibit. Certiorari should be granted to review this ruling.

23

II. This Case Raises an Important Question That Has

Divided the Circuits Concerning Employer Respon

sibility Under Title VII for Employment Actions

Infected by Discrimination on the Part of Supervisors

Below the Rank of Final Decisionmaker.

1. It is common in both the public and private sectors

for an employer to make certain personnel decisions—

including in particular promotions and terminations—

through a process in which various agents of the employer

play different roles. Often the ultimate decision is made

by high ranking managers or supervisors, but the decision

is strongly affected by the actions of supervisors at lower

levels in initiating charges or recommendations, providing

information or evaluations, and otherwise participating

in the decisionmaking process. Where the ultimate de

cisionmakers had no impermissible motive, but supervisors

who played a crucial role in the process acted out of

racial animus or some other unlawful purpose, the ques

tion whether to impose liability on the employing entity

gives rise to difficult issues that have commanded this

Court’s attention under a number of different federal civil

rights statutes.

For example, in City of St. Louis v. Praprotnik, 485

U.S. 112 (1988), the Court held that municipalities are

not liable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for wrongful employ

ment actions taken at the instance of an official who lacks

final policymaking authority over such actions, even if the

subordinate official’s actions are simply rubber-stamped

without any substantive review by the final decision

maker. See id. at 128 (plurality opinion); id. at 137

(opinion of Brennan, J., concurring on this point). The

Court adopted similar principles of employer responsi

bility under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 in Jett v. Dallas Indep. Sch.

Dist., 491 U.S. 701, 737-38 (1989).

More recently, in Gebser v. Lago Vista Indep. Sch.

Dist., 118 S. Ct. 1989 (1998), the Court held that, under

Title IX of the Civil Rights Act, a school district is legally

responsible for sexual harassment of a student by an

employee only where an official with the authority to in

stitute corrective measures on the employer’s behalf knows

about the wrongful conduct and acts with “deliberate

indifference” to it—a standard the Court noted was con

sistent with its standard of employer responsibility under

§ 1983. 118 S. Ct. at 1999.

In Gebser, however, the Court was careful to emphasize

that Title VII is governed by different principles of em

ployer responsibility, inasmuch as Title VII “explicitly

defines ‘employer’ to include ‘any agent’ ” of an em

ployer for the purpose of its prohibition against acts

of employment discrimination undertaken by an “em

ployer.” Id. at 1996. The Court has not yet addressed

under Title VII the question of employer responsibility

for decisions that are made by unbiased final decision

makers but that have been infected in one way or another

by the discriminatory animus of supervisors at a lower

level.

The Court’s recent decisions in Burlington Industries,

Inc. v. Ellerth, 118 S. Ct. 2257 (1998), and Faragher

v. City of Boca Raton, 118 S. Ct. 2275 (1998), illus

trate that the apparent simplicity of Title VII’s statu

tory employer-responsibility language is not matched by

a simplicity of application where the wrongfulness of the

behavior in question stems from, the dereliction of agents

who are not at the top of the employer’s hierarchy. But

the analysis and holdings in Ellerth and Faragher are con

fined to the unique context of sexual harassment, and do

not provide clear guidance with respect to the very differ

ent questions presented by the numerous cases, such as

this one, in which high ranking officers of an entity have

taken adverse employment action without any discrim

inatory intent, but the discriminatory animus of subordi

nate agents has affected the decisionmaking process—

whether because those agents applied racially discrimina

tory standards in determining whether to initiate investi

gations of possible employee misconduct in the first in

stance, see, e.g., Simpson v. Diversitech, 945 F.2d 156

(6th Cir. 1991); or because they presented false or dis

24

25

torted accounts of the employee’s conduct or performance

to the final decisionmaker, see, e.g., Griffin v. Washing

ton Convention Center, 142 F.3d 1308 (D.C. Cir, 1998);

Gusman v. Unisys Corp., 986 F.2d 1146 (7th Cir. 1993);

Roebuck v. Drexel University, 852 F.2d 715 (3rd Cir.

1988); or because they distorted the decisionmaking proc

ess in some other racially-motivated manner.

2. In the absence of guidance from this Court, the

decisions of the courts of appeal in this area have been

inconsistent in their results and unclear as to their under

lying rationales.

Many courts have simply assumed that if a supervisor’s

animus plays any causative role in an employee’s termina

tion, the employer is liable for the consequences of the

termination, notwithstanding the innocence or good faith

of the employer’s final decisionmakers. For example, in

Simpson v. Diversitech, supra, an African-American em

ployee was discharged after having committed three sep

arate disciplinary offenses. The investigation of the second

of those three offenses was initiated out of racial ani

mosity by a supervisor, but that supervisor played no role

either in the final decision to discipline the employee for

that particular offense or in the later decision to terminate

the employee for the combined effect of having committed

three offenses. Even though those decisions were all

made by high-level managers who made an “independent

assessment and judgment” of the facts giving rise to the

charges of misconduct, the Sixth Circuit found the em

ployer liable for the employee’s discharge because, but for

the supervisor’s animus, the employee would not have been

reported for the second offense and would not have been

terminated as a result of the third offense. 945 F.2d

at 159.

Judge Cornelia Kennedy dissented from the Sixth Cir

cuit’s decision in Simpson, rejecting the proposition that

liability flows to the employer under Title VII whenever

a supervisor’s discriminatory motive is the “but for” cause

of an adverse employment action. Id. at 162. According

to Judge Kennedy, liability should attach to an employer

under Title VII only when the persons who actually made

the termination decision acted out of a discriminatory

motive. Id. at 163.

The District of Columbia Circuit’s recent decision in

Griffin is to the same effect as Simpson. In Griffin, the

final decisionmaker consulted with several of her subordi

nates in addition to the biased supervisor, and with the

employee’s union representative as well, before deciding

to fire the employee. The court of appeals held that, even

though the final decisionmaker did not accord automatic

deference to the supervisor—indeed, the decisionmaker

had rejected an earlier recommendation by the supervisor

that the employee be terminated—the employer never

theless was not entitled to judgment as a matter of law,

because the biased supervisor was the decisionmaker’s

“chief source of information” about the employee. 142

F.3d at 1311.

The Third Circuit’s decision in Roebuck goes even

farther in finding employer responsibility. Under the

multi-level tenure review process followed by the defend

ant university in that case, “each successive evaluator

performed a de novo review of [the] candidacy,” yet the

court held that the finder of fact was entitled to conclude

that the university’s decision to deny tenure to the plaintiff

was tainted by discrimination at a low level in the process,

because each evaluator “considered the reports and recom

mendations of each previous evaluator.” 852 F.2d at 727.

3. In sharp contrast to the decisions of other circuits,

the court below held that the School District was insulated

from liability for any racially motivated actions taken by

Principal Mitchell or by Assistant Superintendent Wright

in connection with the decisionmaking process that re

sulted in Lacks’ termination, because the Board did not

itself act out of racial animus, and the Board did not

“defer” to any “recommendation” made by Mitchell or

Wright. App. 13a-14a. The court found it conclusive

that “the school board never discussed any racial discrim-

26

ination against Lacks by school administrators,” and that

“the board made an independent determination as to

whether Lacks should be terminated.” App. 14a.

In reaching this result, the Eighth Circuit did not pur

port to determine that the jury lacked sufficient evidence

for its specific findings that Lacks would not have been

terminated but for her race. See supra at 3 (quoting

the special interrogatories answered by the jury on this

point). As we have noted, Lacks could not be terminated

unless the Board found that she “willfully” violated Dis

trict policy; Mitchell’s testimony was the sole evidence on

which the Board relied in finding willfulness; Mitchell’s

testimony was false; and there was evidence from which

the jury could find that Mitchell was racially motivated.

The jury therefore properly could have found that, but

for the racially-motivated false accusations of Principal

Mitchell, the Board would not have found Lacks to have

engaged in any willful violation, and would not have termi

nated her. The jury also properly could have found that,

but for the racial animus of Mitchell and Wright, who

conducted the investigation into Lacks’ conduct and

drafted the charges against her, charges never would have

been brought to the Board in the first place.

The decision below does not purport to conclude that the

jury could not properly have made such findings on this

record. Rather, the Eighth Circuit’s holding is that, as a

matter of law, the District cannot be held liable in this

case because the Board itself was not biased, and Mitchell

and Wright did not make a formal recommendation

that was rubber-stamped by the Board. App. 13a-14a.

Under Praprotnik and Jett, that rationale would be

defensible if this case were brought under §§ 1983 or

1981. But the decision below offers no explanation as to

how Title VII’s very different statutory language admits of

the approach the court here adopted.

In explaining its decision, the court cited Shager v.

Upjohn Co., 913 F.2d 398 (7th Cir. 1990), in which, after

ruling in favor of the plaintiff on the ground that a final

27

28

decisionmakers lack of a discriminatory animus is not

sufficient to insulate an employer from liability under the

Age Discrimination in Employment Act where the deci

sionmaker’s review of the statements of a biased super

visor is “perfunctory,” id. at 405, the Seventh Circuit went

on to suggest in dicta that an employer should be insulated

from liability if its decision to terminate the employee is

‘independent,” id. at 406, The Shager court did not elab

orate on what qualifies as an “independent” decision for

this purpose, except to say that blind deference, in the

form of a “rubber stamp” review process, does not qualify.

Id. Judge Posner’s opinion in Shager is the only court of

appeals decision besides this one to suggest possible lim

iting principles for employer liability in a case of this

nature; but, like the decision below, Shager neither articu

lated a clear standard of employer liabilty nor explained

how the standard applied was derived.

Whether or not the decision below is consistent with

Shager,14 it clearly is in conflict with the decisions of the 14

14 In Shager, the court reversed a grant of summary judgment

in favor of the employer on the basis that a reasonable jury could

find the following: that the employee’s supervisor was biased

against older workers; that the supervisor submited a report to

the employer’s final decisionmaking committee in which he portrayed

the employee’s performance in the “worst possible light” ; that the

supervisor’s account of the employee’s performance in the report

was facially “plausible” ; and that the committee “was not con

versant with the possible age animus that may have motivated” the

supervisor’s report. Id. at 405 (emphasis added). The phrase in

italics appears to presuppose that a properly functioning decision

making body “conversant” with the evidence of a supervisor’s

animus must, at a bare minimum, explore the possible effect of that

animus on the credibility of the supervisor’s representations re

garding the employee before accepting the supervisor’s version of

disputed events as true.

That did not happen in this case. Here, as the court below

stated, the evidence showed that the Board “never discussed any

alleged racial discrimination” in its deliberations. App. 14a. That

fact, far from relieving the employer of liability under the ration

ale of Shager as the court below appeared to believe, id., instead

more firmly suggests a basis for liability under that rationale.

29

Third, Sixth, and District of Columbia Circuits in Roe

buck, Simpson, and Griffin, supra. In Roebuck and Grif

fin, reliance by the final decisionmaker on facts filtered

through a biased subordinate was held sufficient to give

rise to employer liability, see supra at 26; and in Simpson,

the sole fact that the supervisor initiated the charges out of

racial animosity was deemed sufficient to render the em

ployer liable, see supra at 25. Here, Principal Mitchell

gave crucial false testimony on which the Board relied; and

both Mitchell and Assistant Superintendent Wright were

responsible for initiating the charges against Lacks and

moving them forward. Thus, the conflict between the

decision in this case and Roebuck, Simpson, and Griffin

could not be clearer.

4. Not only do the circuit court decisions on the ques

tion presented here reach inconsistent results, but the

opinions that the courts have rendered in this area of the

law are sketchy and conclusory in their discussions of the

employer responsibility issue, with the result that no com

prehensive framework of analysis has emerged that can

aid the decision of future cases. In that regard, the deci

sion below is typical: the court reached its conclusion

without any discussion of how its view of the law could

be derived from the language and purposes of Title VII

or from any principles of agency law.

This lack of a comprehensible analytic framework can

only be expected to compound the existing confusion in

the law, leaving employers and employees uncertain as to

their responsibilities and their rights under Title VII, and

resulting in decisions that cannot be reconciled in any

principled way.15 In some cases, like Roebuck, Simpson

15 Indeed, in the short time since the Eighth Circuit rendered its

decision in this case, the confusion in the law has been further

compounded by that court’s 2-1 decision in Kramer v. Logan County

School District No. R-l, 157 F.3d 620 (8th Cir. 1998), where the

court upheld a Title VII jury verdict against the employer school

district, even though the employee had a full hearing before an

unbiased school board before she was terminated. The dissenting

30

and Griffin, the employer will be held liable even though

the ultimate decisionmaker acted without racial animus

and made an independent judgment; in other cases, like

this one, an employee who would not have been terminated

but for the racially motivated actions of an agent of

the employer will be left without redress. Certiorari should

be granted so that this Court can clarify the law on this

important and recurring question.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, a writ of certiorari should

issue to decide both questions presented in this Petition.

Judge in Kramer, who sat on the panel in the case sub judice,

found the two cases to be indistinguishable. Id. at 629 (“Our recent

precedent in Lacks demands that we set aside the jury’s verdict.” )

The majority opinion by Judge Limbaugh, on the other hand, did

not even cite the decision in this case. Judge Richard Arnold, who

wrote the opinion below, penned a separate concurring opinion in

Kramer for himself only, in which he purported to reconcile Kramer

and Lacks on the basis that, in his view, “ [t]he evidence of bias on

the part of the administrators in Lacks was very weak, and the

misconduct of the teacher (or what the board regarded as mis

conduct) was egregious.” Id. at 627.

Judge Arnold’s effort in Kramer to explain the result in this case

only adds to the confusion in the law. No court of appeals has sug

gested that, where there is sufficient evidence of bias on the part

of a supervisor to create a jury question—and the court’s opinion

below is predicated on the acknowledgement that there was such

evidence with regard to Mitchell and Wright—the reviewing court’s

perception of the strength of that evidence somehow becomes a

factor in determining whether the employer may be held liable for

the supervisor’s act. Nor has any court found the perceived “egre

giousness” of the employee’s alleged misconduct to be a relevant—•

much less a dispositive—factor in that regard. If the decision below

were read with the gloss subsequently placed on it by Judge Arnold

in Kramer, the lower-court law would only devolve into an even

greater state of disarray.

Respectfully submitted,

J eremiah A. Collins *

Leon Dayan

Bredhoff & Kaiser, P.L.L.C.

1000 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 833-9340

* Counsel of Record

APPENDICES

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 97-1859EM

Cecilia L acks,

Appellee,

F erguson R eorganized School D istrict R-2,

________ Appellant.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri

Submitted: January 12, 1998

Filed: June 22, 1998

Before RICHARD S. ARNOLD,1 Chief Judge, WOLL-

MAN and HANSEN, Circuit Judges.

RICHARD S. ARNOLD, Chief Judge.

In this case Ferguson-Florissant Reorganized School

District (“the school board”) appeals the District Court’s

grant of summary judgment in favor of the plaintiff,

Cecilia Lacks, on Lacks’s claim under Missouri law that

her termination by the board was not supported by sub-

l The Hon. Richard S. Arnold stepped down as Chief Judge of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit at the

close of business on April 17, 1998. He has been succeeded by the

Hon. Pasco M. Bowman II.

2a

stantial evidence. The school board also appeals a jury

verdict in favor of Lacks on First Amendment and race

discrimination claims. We reverse and remand for the

entry of judgment in favor of the defendant school district.

We hold, among other things, that a school district does

not violate the First Amendment when it disciplines a

teacher for allowing students to use profanity repetitiously

and egregiously in their written work.

I.

Cecilia Lacks began teaching at Berkeley Senior Fligh

School in the fall of 1992 after teaching at other schools

in the same school district since 1972. Lacks taught

English and journalism classes, and she sponsored the

school newspaper. In October 1994, Lacks divided her

junior English class into small groups and directed them

to write short plays, which were to be performed for the

other students in the class and videotaped. The plays