Jackson v. Rawdon Appellees' Brief

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Rawdon Appellees' Brief, 1956. a18e9efe-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/695a9e2e-cd8d-49cc-9a2f-016ca3ea2984/jackson-v-rawdon-appellees-brief. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

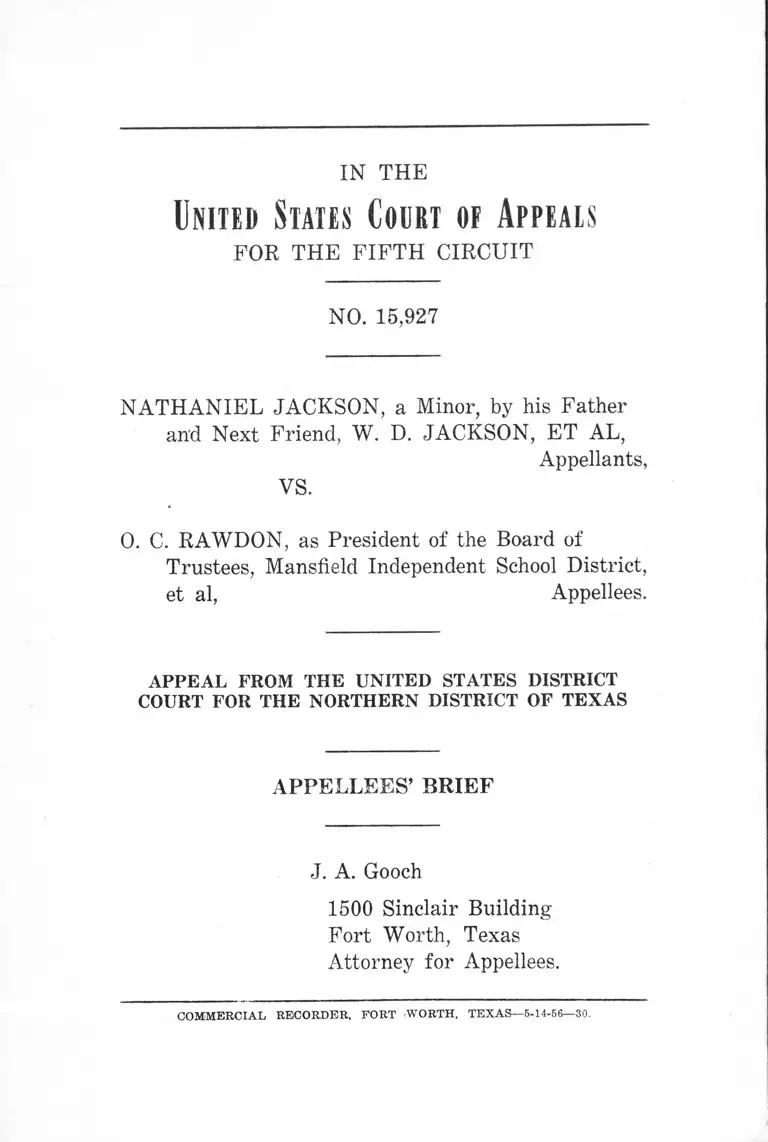

IN T H E

U n it e d S tates C o u r t of A p p e a l s

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 15,927

NATHANIEL JACKSON, a Minor, by his Father

and Next Friend, W. D. JACKSON, ET AL,

Appellants,

VS.

0. C. RAWDON, as President of the Board of

Trustees, Mansfield Independent School District,

et al, Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

J. A. Gooch

1500 Sinclair Building

Fort Worth, Texas

Attorney for Appellees.

COMMERCIAL RECORDER. PORT WORTH, TEXAS—5-14-56—30.

U n i t e d States C o u r t of A p p e a l s

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN T H E

NO. 15,927

NATHANIEL JACKSON, a Minor, by his Father

and Next Friend, W. D. JACKSON, ET AL,

Appellants,

VS.

0. C. RAWDON, as President of the Board of

Trustees, Mansfield Independent School District,

et al, Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPELLEES’ BRIEF

■2—

TO THE HONORABLE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS:

Appellees are the administrative officers of a rural

independent school district in a farming community

in Tarrant County, Texas, and have, to the best of

their ability, administered the affairs of such school

district in complete obedience to all laws of the land

for many years.

Through the medium of the press and other modern

means of communication, appellees were informed of

the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States

in the Brown case (Brown et al v. Board of Education

et al, 347 U.S. 483; 74 S.Ct. 686 (1954), 349 U.S.

294, 75 S.Ct. 753 (1955)), and upon later receiving

a copy of such opinion, read, digested and as best they

could, understood the meaning of such a decision.

Accordingly they set about forthwith to obey the de

mands and teachings as were present in such ruling.

It was, however, quite a shock to such persons, be

cause the opinion in the Brown case completely re

versed the former decision of the Supreme Court which

had stood as the law of the land for approximately fifty

years. At the same time, appellees were cognizant

of the laws of the State of Texas which, in unmistak

able words made it a crime for a school board such as

that of the Mansfield. Independent School District, to

integrate the clases of people spoken of in the Supreme

Court ruling.

— 3-

Appellees, upon reading the decision and being in

formed that they must take steps to comply, began a

serious study of local problems and a serious study

of the means of solving such problems, to the end that

the least possible friction* could be averted and to the

end that violence and tempers would be curbed. As

we view the language of the Brown case, supra, we

perceive from it the same meaning as did the school

board, to-wit, that it was up to the local school boards,

with as much haste as possible, to seek out the prob

lems involved in integration, sooth as best they could

the ruffled tempers of the more irate, and to allow

the matter to work itself out gradually, rather than

to split a community wide open and thereby damage

the relationships that had formerly existed between

friends and neighbors.

The Brown case contains, to both the trained and

the untrained mind, clear and unequivocal mandates,

particularly that part reading as follows:

“Full implementation of these constitutional

principles may require solution of varied local

school problems. School authorities have the pri

mary responsibility for elucidating, assessing,

and solving these problems; courts will have to

consider whether the action of school authorities

constitutes good faith implementation of the gov

erning constitutional principles. Because of their

proximity to local conditions and the possible

need for further hearings, the courts which orig

inally heard these cases can best perform this

4

judicial appraisal. Accordingly, we believe it

appropriate to remand the cases to those courts.

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees,

the courts will be guided by equitable principles.

Traditionally, equity has been characterized by a

practical flexibility in shaping its remedies and

by a facility for adjusting and reconciling public

and private needs. These cases call for the exer

cise of these traditional attributes of equity

power. * * *”

This language was read and understood by these

appellees, and forthwith they did find themselves con

fronted with problems, the solution of which was not

an easy one. They began a system of conversations,

talks, meetings and education of the people affected

in their community. The appointed a committee to

act as a clearing house. The School Board, in its own

meetings, received the problems and began a serious

effort to obey the mandate of the Supreme Court, and

found that in their honest opinion, with this decision

coming down in May 1955, that the time was too short

to integrate at the next term of school, beginning in

September 1955. The understandable language of the

Supreme Court in its mandate to them was in simple

terms:

1. That they, as the local administrators of

the Mansfield Independent School District, were

to determine their own local problems.

2. They were told that as the Governing Body

of the School District, they had the primary re

sponsibility for finding out their problems, evalu

ating and solving them.

3. They were told that their actions in deter

mining and solving their problems would be sub

ject to scrutiny of their local Federal District

Court upon demand by either group.

4. They were told that their local court, be

cause of proximity and judicial knowledge of

local problems, would be the judge as to whether

or not their actions toward integration were in

the nature of procrastination or were in good

faith, and were further told that their local court

would be the final arbiter on the question of good

faith.

These appellees, knowing the thoughts and ideas of

their friends and neighbors by virtue of having lived

in the small community for substantially their life

times, and having had expressed to them these thoughts

and ideas, set about, by talks, meetings and thought

ful purpose, to bring to their community the know

ledge that the Brown case was the law of the land

and that same had to be obeyed as long as it remained

the law of the land, and appellees found in their tribu

lation's extremists on both sides of the case, which is

the cause in all instances of the disruption of the af

fairs of any community.

— 6 -—

This Honorable Court judicially knows, and the

lower court at the time of the proceeding there, ju

dicially knew that an established social law of more

than fifty years standing could not be abruptly over

turned without upsetting a great majority of the

people in' this country, and particularly in the South.

The Supreme Court must have realized this situation,

for there was over a year’s difference between the time

of the original opinion of the Supreme Court and the

final order with respect thereto. Had the Supreme

Court not taken cognizance of the problems that would

arise by a forced integration, it had the power to and

could have abruptly ended segregation by the stroke

of a pen and could have fixed a time within which all

persons must comply with the rule. The Supreme

Court did neither of these things, in the 1954 or the

1955 decisions, but, as stated in its opinion, advised

that the rules of equity must apply in obeying its man

date, and prescribed certain rules which they them

selves called flexible in admonishing compliance with

its order.

This court, as did the court below, knows of vio

lence and regretable incidents occurring by reason of

the action of pressure groups on both sides of the ques

tion where hasty action has been taken or suggested.

Appellants in their brief make light of the prayers

of appellees, wherein Divine guidance was sought in

the solution of their problems (Appellants’ brief, page

1.0). Certainly, the seeking of Divine guidance is a

— 7—

manifestation of good faith, as it is from that source

that all good originates.

The local trial court, under the mandate of the Su

preme Court, has on substantial and uncontradicted

evidence held that appellees have acted and are act

ing in good faith to comply with the edict of the Su

preme Court. Had the Supreme Court wished to

place n'on-segregation in immediate effect, it could,

as above set forth, have done so by establishing a dead

line. Therefore, the Supreme Court itself recognized

that there would be many and varied problems and

many and varied jurisdictions and therefore decreed

that the enforcement of its rule be accomplished on

a sane, sensible and thoughtful basis, and by its very

pronouncement left the issue of good faith working

toward the ultimate end to the local trial courts in

each community.

Since the trial court in its wisdom and upon the

record in the case has determined that appellees have

complied and are complying with both the letter and

the spirit of the law, the judgment in this case should

not be disturbed.

Appellants seem to have ample talent, time and fi

nances for the advancement of their cause, and, with

out any cause whatsoever, seem to be impatient, dom

ineering and demanding, so it goes without saying

that they can and will express themselves again by

the refiling of their suit if perchance they think the

— 8 —

acts of appellees have changed from good faith to

procrastination.

It is without dispute that the individual plaintilfs

in the case below had little or no interest in integra

tion for themselves alone. It does not take either

testimony or imagination to reveal that the pressure

in this and similar cases comes from a highly organ

ized minority who find fault with the equity principles

prescribed by the Supreme Court leading toward

compliance.

We respectfully submit that the decision of the trial

court was correct.

Respectfully submitted,

J. A. Gooch

1500 Sinclair Building

Fort Worth, Texas

Attorney for Appellees.

— 9—

Certificate of Service

I, J. A. Gooch, hereby certify that I have this the

-------- day of May, 1956, placed copies of appellees’

brief in the United States Mail, postage paid, ad

dressed to the following attorneys for appellants:

L. Clifford Davis,

401% East 9th Street

Fort Worth, Texas

U. Simpson Tate

2600 Flora Street

Dallas, Texas

Robert L. Carter

Thurgood Marshall

107 West 43rd Street

New York, New York

J. A. Gooch