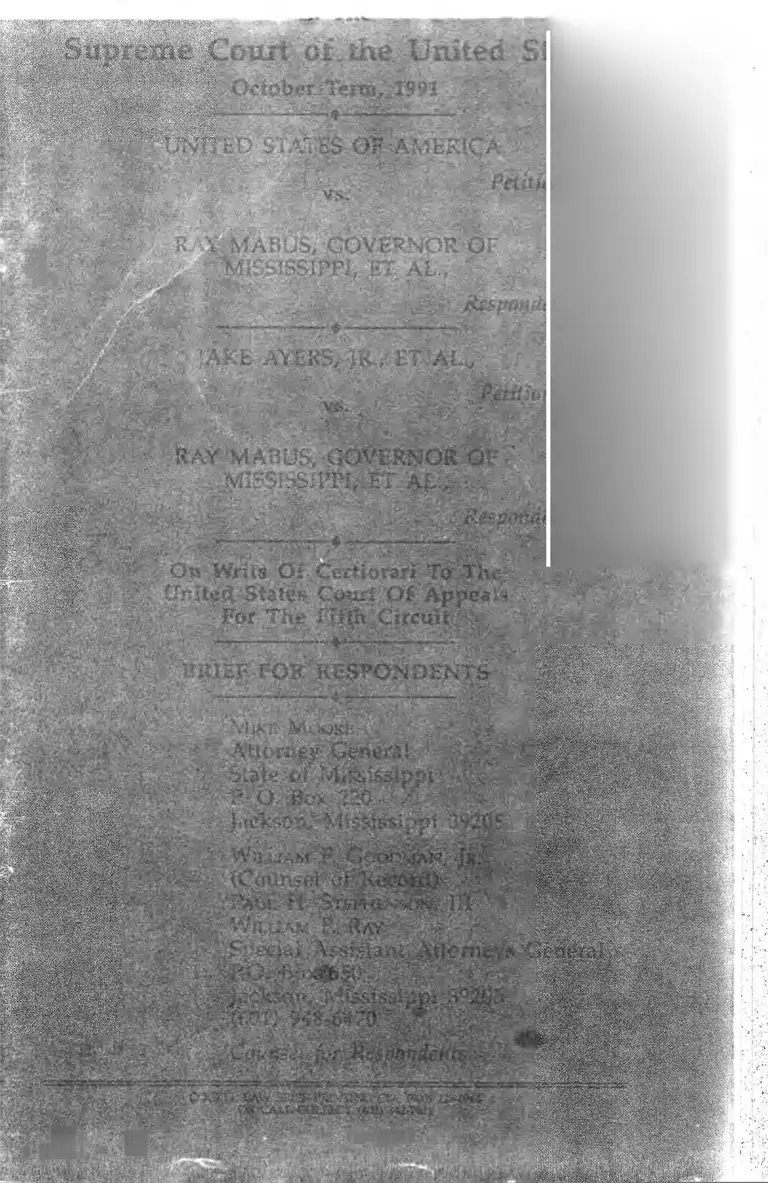

United States v. Mabus Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Mabus Brief for Respondents, 1991. 5465218e-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/695aa8ff-3564-447a-bcac-b733c177925d/united-states-v-mabus-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

<■ • I

4 ‘'- -jft;

. ' i - u 3 ; ' . ' * ' - ' U ' ' •'-■

'■ -•» '•;/̂ *̂ ŝ̂ ■ ̂■ ■

' * ■ ' • - " ' v

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. The private petitioners' question concerning the scope of

the legal duty to disestablish should be more precisely stated

under the court of appeals' opinion as follows:

Whether Mississippi's affirmative duty to

disestablish its prior system of de jure segrega

tion in higher education extends beyond discon

tinuing prior discrim inatory practices and

adopting and implementing for years good-

faith, race-neutral policies and procedures

which afford all students real freedom of choice.

2. The private petitioners' question concerning the appli

cability of Title VI regulation 34 C.RR. § 100.3(b)(6)(i) should

be more precisely stated on this record as follows:

Whether Title VI and 34 CF.R, § 100.3(b)(6)(i)

impose on Mississippi an affirmative duty to dises

tablish its prior system of de jure segregation in

higher education beyond the adoption and years of

implementation of genuine nondiscriminatory poli

cies coupled with substantial affirmative efforts to

promote desegregation which afford all students

real freedom of choice.

3. The United States' question misconstrues the court of

appeals' opinion. The proper question is as follows:

Whether the district court's finding that the

continued racial identifiability of Mississippi

universities persists today as the result of free

and unfettered choice of students and personnel

and despite the State's substantial affirmative

good-faith efforts in "other-race" recruitment

and resource allocation is clearly erroneous.

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS P R E SEN TE D ................................. i

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE............................................... 2

1. The Parties' Contentions at Trial ............. ............ 3

2. The Factual R eco rd ..................................................... 5

a. Student Recruitment............................................. 7

b. Admission Standards........................................... 10

c. Faculty and Staff Employment........................ 16

d. Institutional R esources................... 19

i. M iss io n s ......................................................... 19

ii. Funding.......................................................... 21

iii. Programs............................... 23

iv. Facilities........................................................... 28

3. The District Court's Decision.................................. 29

4. The Court of Appeals' Decision............................ 31

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................................... 33

A RG UM EN T............................................................................... 36

I. Mississippi has fulfilled its duty under the

Fourteenth Amendment to disestablish state-

im posed segregation in higher education

through the adoption and years of implemen

tation of good-faith, genuinely nondiscrimina-

tory policies which do not contribute to

institutional racial identifiability........................... 36

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

A. The constitutional duty to disestablish

state-imposed segregation in higher edu

cation may be satisfied by discontinuing

prior discriminatory practices and imple

menting good-faith, race-neutral policies

and procedures.................................................. .. 36

B. The district court's finding that the contin

ued racial identifiability of Mississippi

universities persists today as the result of

free and unfettered choice of students and

personnel is not clearly erroneous............. 48

1. The nondiscriminatory, educationally

reasonable current admission stan

dards are not the cause of any con

t i n u e d r a c i a l i d e n t i f i a b i l i t y of

universities......................................... 49

2. The educationally reasonable assign

ment of missions and allocation of

resources are not the cause of any con

tinued racial identifiability of the uni

versities........................... ... ............................ 57

II. The duty to disestablish state-imposed segrega

tion in higher education is no greater under Title

VI than under the Constitution. In any event

Mississippi has fulfilled any alleged greater duty

under Title VI through the adoption and years of

implementation of genuine nondiscriminatory

policies coupled with substantial affirmative

efforts to promote desegregation.............................. 64

CO N C LU SIO N ................. ........................................................ 70

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C ases

Alabama State Teachers Ass'n v. Alabama Public

School and College Auth., 289 F.Supp. 784 (M.D.

Ala. 1968), aff'd per curiam, 393 U.S. 400 (1969)

........................................................................................... 31, 39, 40

Alexander v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287 (1985)........................... 64

Artis V. Board of Regents, No. CV 479-251 (S.D. Ga.

Feb. 2, 1 9 8 1 ) ............................................................................ 63

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986)..................... passim

Board of Curators o f the University o f Missouri v.

Horowitz, 435 U.S. 78 (1 9 7 8 ) ............................................ 45

Board of Education v. Dowell, 111 S.Ct. 630 (1991) . . . . 46

Brown v. Board of Education:

347 U.S. 483 (1 9 5 4 ) ........................................ 34, 37, 60, 70

349 U.S. 294 (1 9 5 5 ) ................................................................ 37

City of Richmond v. /. A. Croson Company, 488 U.S.

469 (1989)............................................................................ 41, 45

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979)........................................................................................... 46

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406

(1977).......................................................................... 47

Dcthard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977)....................... 51

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U.S.

413 (1956)................................................................................... 36

Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986)............. 47

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644 (M.D. Term. 1977) . . . . 63

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)......................................................... passim

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission of

City o f New York, 463 U.S. 582 (1983)..................... 64, 65

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985)................... .. 50

Keyes v. School District No. L Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189 (1973 ) ........................................................................ 40

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ...................................................................................... 34, 36

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ............................ 56

M issouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

( 1 9 3 8 ) . . . . . ................................................................................ 36

Norris v. State Council o f Higher Education for Vir

ginia, 327 F.Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va.), aff'd, 404 U.S.

907 (1971)................................................................................... 39

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976 ) ............................................................. , . . . . 42

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978) .................................................................47, 64

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 ) ................................................. .37, 42

Sweatt V. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) .......................... 36

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1956)............... 47

United States v. LULAC, 793 F.2d 636 (5th Cir. 1986) . . . . 56

Watson V. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963)... .37, 38

Wygant v. fackson Board o f Education, 476 U.S. 267

(1986)............................................ ................................... .. 46

S tatutes

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

7 C.F.R. § 15.3(b)(6)(i) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(6)(i)...................... ...64, 65

Nos. 90-1205, 90-6588

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Petitioner,

vs.

RAY MABUS, GOVERNOR OF

MISSISSIPPI, ET AL„

Respondents.

JAKE AYERS, JR., ET AL„

Petitioners,

vs.

RAY MABUS, GOVERNOR OF

MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

Respondents.

On Writs Of Certiorari

To The United States Court Of

Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

The State of Mississippi respondents^ submit this

consolidated response to the briefs separately filed by the

’ Respondents are the Governor, the Commissioner of

Higher Education, the Board of Trustees of State Institutions of

(Continued on following page)

1

private petitioner class of black citizens and the United

States.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The State of Mississippi admittedly maintained a seg

regated system of higher education through at least 1962.

The Board of Trustees and the universities subsequently

im plem en ted , however, nonracia l ad m issions and

employment practices. Moreover, by the mid-1970's State

policies clearly extended beyond the genuine operation of

the universities without regard to race. The Board affir

matively acted to send the unmistakable message that

discriminatory practices were affairs of the past. Since

that time the State has faithfully implemented nonracial

practices coupled with good faith affirmative efforts to

encourage further desegregation.

The petitioners' statem ents of the case unduly

emphasize historical acts of state-imposed segregation of

a long since concluded discriminatory era. While pre

dominantly black and, to a lesser extent, predominantly

white universities do remain, the record, district court

opinion and court of appeals opinion preclude any notion

of mechanical equation of Mississippi's system today

(Continued from previous page)

Higher Learning, the individual members of the Board of

Trustees, Delta State University, Mississippi State University,

Mississippi University for Women, the University of Missis

sippi, the University of Southern Mississippi, and the chief

administrative officer of each of these five universities. Unless

the context otherwise requires, references in this brief to "the

State" include all respondents. References to "the Board"

address the Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher

Learning.

with its distant unconstitutional past. The petitioners'

statements are incomplete; they do not portray fairly the

record as a whole or the lower courts' extensive findings.

Consequently, extensive supplementation is required.

1. The Parties' C ontentions at Trial. Petitioners

advanced their claims for "disestablishment" on two

largely conflicting fronts. First, they asserted the State

unlawfully "discriminated" against the predominantly

b lack u n iv e rs it ie s in the a llo ca t ion of resources.

(Amended Complaint, R. 40-41, Hf 3(b), (c), (d); Com

plaint in Intervention, R. 94, f i b ) Petitioners urged sub

stant ial in st itu t io n a l enhancem ent because of the

predominant presence of blacks at these institutions.

Indeed, private petitioners specifically sought the "equal

ization" of resources between the predominantly black

and predominantly white universities. (Amended Com

plaint, R. 77-78, Prayer for Relief, *1 A(2)) Second, peti

tioners demanded a greater black presence at the

p red om in antly whi t e u n iv ers it ies . Yet petit ioners

advanced no contentions specifying the alleged degree of

racial balance required or what efforts or results would

allegedly be enough to constitute "disestablishment.

2 Thus, petitioners' proof overwhelmingly consisted of

quantitative institutional comparisons according to predomi

nant racial presence. Purported funding, program, facilities

and land grant analyses were driven by race with virtually no

consideration of normative educational criteria. The United

States refused to submit a single government representative for

deposition on any issue. (Notice of 30(b)(6) Deposition, R.

1162-63; Motion for Protective Order, R. 1168-70) No spokes

man for the Department of Education testified at any time.

(Continued on following page)

Mississippi's defenses were primarily represented in

two ultimate alternative contentions: (i) the State has

fulfilled its duty to disestablish state-imposed segrega

tion by implementing and maintaining good faith, non-

discriminatory and nonracial admissions and operational

policies with respect to students, faculty and staff; and

alternatively (ii) given the nondiscriminatory policies, the

State in any event has fulfilled its duty through its affir

mative good faith efforts to attract qualified black stu

dents and personnel to predominantly white universities

and qualified white students and personnel to predomi

nantly black universities. Given the existence of such

genuine policies, the State maintained that the mere con

tinued existence of predominantly black and predomi

nantly white universities is not unlawful considering

individual freedom of choice and the varying objectives

and advantages of such institutions. (Pretrial Order, R.

1376, Exh. F Def. Statement of Contested Issues of Law)

Hence, the State's proof delineated the substantial

efforts expended to further desegregation to the point of

establishing the virtual exhaustion of feasible student,

faculty and staff recruitment procedures. Board witnesses

(Continued from previous page)

The United States even declined to involve the United States

Department of Agriculture which established and adminis

tered many of the land grant policies challenged. Petitioners

simply ignored the State's substantial efforts to increase the

presence of other-race students, faculty and staff. To be sure,

petitioners' standardized testing witness criticized the State's

use of the American College Test (ACT), but he also declined to

address the determinative issue of an appropriate admissions

standard.

focused upon the legitimate educational criteria adhered

to in admission, employment and resource allocation

practices. The State proved the admission policies are not

the cause of any institutional racial identifiability. The

State demonstrated the absence of any racial pattern in

the provision of resources. The record as a whole thereby

reflects a system genuinely untainted by discriminatory

actions, purposes, or effects.

2. The Factual Record. HEW's Office of Civil Rights

contacted the Board in 1969 and the early 1970's in con

junction with OCR's ongoing review of state systems of

higher education once segregated by law. The Board

advised OCR that the Mississippi system already com

plied with all legal requisites. Nevertheless the Board

indicated the State would take further affirmative steps to

enhance desegregation. (Exh. Bd-001, J.A. 898) The Board

and OCR could not agree, however, regarding an accept

able statewide approach to promotion of further deseg

regation.^ The absence of an agreement with OCR

notwithstanding, the Board elected to implement a formal

plan to foster desegregation which became known as the

3 A major sticking point was the absence of a comprehen

sive approach to desegregation of the junior (community) col

lege system. The state-supported establishment for higher

education includes 15 junior colleges and 8 universities. It is

not, however, a single system. Each junior college has its own

local governing board. The pervasive presence of the junior

colleges is significant. They span the entire State. They are

accessible to virtually all Mississippi citizens. They actually

enroll over 60% of all Mississippi high school graduates elect

ing to participate in public higher education. (P.A. 119a; Exh.

Bd-185 at 1-3, J.A. 1201-02)

"Plan of Compliance." (P.A. n9a;4 Exh. Bd-019, Bd-020,

J.A. 904)

From the very outset of Plan development and imple

mentation the Board declared the State's commitment to

equal educational opportunity with irrefutable clarity.

The Plan of Compliance identified its "basic objective" as

"the improvement of educational opportunities for all

citizens of the State of Mississippi with particular

emphasis on equal access and retention for members of

minority races"; the Plan repeatedly asserted as its funda

mental goal the attraction of other-race students, faculty

and staff to each university. (Exh. US-1 at 3, 6, 12, j.A. 66,

68, 73) The Board directed the universities to implement

the Plan to the best of their abilities. The Board pointedly

responded to institutional questions concerning inter

pretation of the commitments under the Plan. For exam

ple, the Board explicitly instructed: "official representa

tives of institutions are not to become directly involved

with employers, schools, realtors, athletic officials, medi

cal care providers, and all others who do not have a

nondiscriminatory policy regarding race"; "recruiting of

students is prohibited at schools that have not filed with

the Board’ . . . a nondiscriminatory policy"; and each

university is to "pay careful attention" to the "commit

ments to employment and promotions of university

Citations to the lower court opinions will be referenced

to the appendices following the United States' petition in

which the opinions have been reproduced. Designations will

be "P.A. [page]."

personnel" identified in the Plan. (Exh. Bd-020, J.A.

904-06) The universities have properly responded.^

a. Student Recruitment. Each institution expends

every reasonable effort to increase other-race student par

ticipation. (Exh. US-960 at 10, J.A. 778-79; Exh. US-965 at

91, J.A. 796-98; Exh. US-962 at 125; Exh. US-964 at 31; T.

3493-94, J.A. 1708; US-967 at 12-13; Exh. Bd-010 thru

Bd-018) It is not just a matter of all student recruiters

seeking other-race students, for the universities also

employ minority recruiters charged with this specific

responsibility. Moreover, the universities do not limit

such desegregative efforts to specifically employed staff;

they involve other-race students, faculty and alumni,

sometimes as multi-racial teams, in their recruitment

efforts. (P.A. 134a; e.g., Exh. Bd-105 at 5, J.A. 913-14;

Bd-069 at 5, Bd-044 at 6-7 & Bd-129 at 18; US-964 at 19-20,

25-26 & 39-40; Exh. US-962 at 9, 22 & 49; Exh. US-961 at

20, 28-29; Exh. US-950 at 17; US-967 at 7, 9 & 47; Exh.

US-965 at 15-16 & 18-22; Exh. US-960 at 20, J.A. 779)

Representatives of the predominantly white universities

annually visit more than 100 predominantly black high

schools, and representatives of the predominantly black

universities expend similar efforts with respect to pre

dominantly white high schools. (P.A. 134a-35a; e.g., Exh.

̂ The Board has required, and the institutions have pro

vided, annual reports exhibiting the affirmative efforts

expended toward increasing other-race presence at each uni

versity. Following a detailed format established by the Board,

the 109 comprehensive "implementation reports" submitted by

the universities as of the time of trial demonstrate not only

these efforts but also each institution's recognition of the

State's serious commitment to affirmative action. (Exh. Bd-021

thru Bd-129)

8

Bd-105 at 41-60, J.A. 946-72; Exh. Bd-033 at Attmt 1; Exh.

Bd-021 thru Bd-129, listings of schools recruited)

University publications and promotional activities

are significant components of the minority recruitment

endeavors. The universities consciously depict other-race

students in recruitment brochures and other university

publications. (E.g., T. 3493, J.A. 1708; Exh. Bd-129 at 18,

Bd-069 at 5 & Appendix, Bd-044 at 7; Exh. US-962 at

19-20) Indeed, they specifically design many such pub

lications exclusively to appeal to other-race students.

(Exh. Bd-133, J.A. 997; Bd-140 thru Bd-144, J. A. 1012-95;

Bd-159, J.A. 1113; Bd-104 at 5, Appendix B; Bd-121, Annex

C; Exh. US-964 at 32-33; Exh. US-965 at 22-24; Exh. US-961

at 37) The universities similarly utilize public media

devices such as news releases, promotional radio spots,

public service announcements, newspaper advertise

ments, and display sponsorships to emphasize other-race

participation in campus life. (P.A. 134a; Exh. Bd-033 at 4;

Exh. Bd-069 at 5-6; Exh. Bd-071 at 3; Exh. Bd-077 at 8;

Exh. US-962 at 19-20) Still additional examples of the

State's commitment to increase other-race enrollment

include financial assistance and minority scholarship pro

grams, consortiums, cooperative, graduate and profes

sional opportunities programs with junior colleges and

universities with substantial other-race enrollment, spon

sorship of programs with particular other-race appeal

such as "Black History Week" and "Black Awareness

Month," and maintenance of campus offices of minority

student affairs. (Exh. Bd-033 at 5; Exh. US-967 at 54; Exh.

US-964 at 35-36; Exh. Bd-102 at 21, 32, 34, Appendix L;

Exh. Bd-104 at 5 & Appendix H; Exh. Bd-058 at 21-22;

Exh. Bd-068 at 14; Exh. Bd-114 at 5-7, 16)

Furthermore, the State's commitment need not be

measured exclusively by efforts to attract other-race stu

dents. Once enrolled, other-race students enjoy com

pletely desegregated campus environments. Minority

students have significantly participated and succeeded at

each institution. They have been elected to the univer

sities' "Hall of Fame," to "Who's Who in American Col

leges and Universities," "Mr. University" and home

coming queen. Blacks have participated in intercollegiate

or intramural athletics, as varsity cheerleaders, in scho

lastic honorary societies, in bands and in performing

groups. They have assumed leadership positions in a host

of student government, school publication, residence hall

and other student associations. (P.A. 135a; T. 3444, J.A.

1691; Exh. Bd-042 at 15; Exh. Bd-101 at 40-45; T. 3509-10,

J.A. 1713-14; Exh. Bd-068 at 9-12; Exh. Bd-083, § 7.g; Exh.

Bd-125 at 14, 22; Exh. Bd-034 at 9-10; Exh. Bd-045 at 10-11,

15-16; Exh. Bd-033 at 6; Exh. Bd-057 at 12-13; Exh. Bd-055

at 15-16; Exh. Bd-101 at 41-43; Exh. Bd-128 at 30-32; Exh.

Bd-042 at 15; Exh. Bd-103 at 24)

Racial percentages are by no means determinative,

but the substantial "statistical success" of the universities

in student recruitment should not be overlooked. The

actual representation of blacks in the freshman classes at

Delta State University, Mississippi State University, Mis

sissippi University for Women, and the University of

Southern Mississippi is statistically in parity with the

representation of blacks in the qualified pools. No statisti

cal distinction according to race can be drawn at these

predominantly white universities; qualified blacks and

10

qualified whites are equally likely to enroll.^’ (T. 4219, J.A.

1856-57)

b. Admission Standards. As in most states, a univer

sity education is not immediately available in Mississippi

to alt high school graduates, white or black. An aspiring

first-time freshman student must complete a university

preparatory curriculum and achieve a satisfactory score

on the ACT.^ Successful completion of certain essential

̂ Private petitioners, but not the United States, attempt to

utilize the University of Mississippi's (UM) absence from this

list of institutions as evidence of discrimination. They of course

ignore the obvious implications of such a blanket contention

for the predominantly black universities. Private petitioners do

also emphasize isolated individual complaints of blacks at UM,

which complaints are largely unfounded. (T. 1393-96, J.A.

1474-76; T. 1441-43, J.A. 1491-93; T. 2693-2705, J.A. 1597-1604; T.

2775, J.A. 1634) Clearly any alleged statistical shortfall or soli

tary grievances at UM cannot be attributed to any lack of

genuine institutional commitment to nondiscriminatory poli

cies and affirmative action. UM's other-race procedures are the

same as, or in some instances even more elaborate than, those

of other predominantly white institutions who may have

enjoyed greater "statistical success." (T. 4118-32, J.A. 1837-46;

Exh. US-962 at 9, 26-30, 119-25; Exh. Bd-094 thru Bd-105; Exh.

Bd-140 thru Bd-147, J.A. 1012-1095; Exh. Bd-104 at 30-31 &

Bd-103 at 28) The achievements of black students at UM are

numerous and demonstrate UM's acceptance of black students

into mainstream campus life. (Exh. Bd-lOO at 80-85 & Bd-101 at

40-46) UM has dedicated over $6,000,000 of its own institu

tional funds to affirmative action. (T. 4132, J.A. 1845) The

district court correctly found no evidence that the compara

tively low black enrollment results from official action. (PA.

186a)

̂ The current admission standards are set forth in exhibit

Bd-183a. (J.A. 1174) They have been pointedly summarized by

(Continued on following page)

11

academic courses in high school significantly contributes

to academic readiness for the university experience. (T.

3573-84) The ACT is indisputably a reliable instrument

used nationwide as an integral component of college

admission standards. Not an aptitude test, the ACT is a

standardized measurement of developed academic abili

ties deemed important for success in college. (T. 3711-14,

J.A. 1759-61) The positive relationship between perform

ance on the ACT and academic achievement has been

clearly demonstrated at Mississippi universities. (P.A.

129a; T. 3458-59, 3726-28, 3763-64; US-967 at 75-78; Exh.

Bd-275)

The universities' particular curriculum and ACT req

uisites are in no respect rigorous. No specific grade point

average is even required. The ACT scores needed for

automatic admission are extremely modest levels of

achievement. Scores of 15 are only on the verge of a

freshman reading level. (P.A. 130a; Exh. Bd-190 at 5-10)

Nonetheless, students who score as low as 9 on the ACT

are still considered for admission under exceptions poli

cies. Students who achieve a 9 on the ACT English and

social studies tests are only reading at a ninth grade

level.« (T. 3732-33, J.A. 1769) Thus, the requisite score

(Continued from previous page)

both lower courts. (P.A. 7a-8a, 126a-28a) These present stan

dards are plainly not limited to performance on standardized

tests. It should probably be noted that the ACT organization

has changed the test grading practices since trial. For example,

a score of 15 in 1987 would be an 18 in 1991. This change is,

however, of no substantive consequence here.

® Ninety-five percent of all students tested nationwide

score 9 or above and over 70% of all students score 15 or

above. (P.A. 130a; Exh. US-874 at 9) Nine out of every ten ACT-

(Continued on following page)

12

levels at Mississippi universities differ dramatically from

institutions having highly selective or even selective poli

cies. (T. 3729-30, J.A. 1768) The Board's admission stan

dards are also less demanding than NCAA Proposition

48, the well-known national policy for athletes.® (P.A.

131a-32a; T. 358-485, J.A. 1730-31)

Furthermore, no applicant to a public university is

ever ultimately denied the opportunity to obtain a uni

versity degree for failure to achieve a particular ACT

score, including even the 9. Admission is at most

deferred. Students may attend a public junior college

without test score requirements and transfer after suc

cessful completion of as few as 15 hours. Thousands of

students elect to attend junior colleges in Mississippi;

substantial numbers of these students subsequently

transfer to public universities. (P.A. 133a; Exh. Bd-185,

J.A. 1201-06; T. 3445-46, J.A. 1692; T. 3504-05, J.A. 1711; T.

3724-25, J.A. 1767)

(Continued from previous page)

tested students in Mississippi, including 80% of all black stu

dents, score 9 or above. (T. 3730-31, J.A. 1768-69) The mean

ACT score for blacks who evidence genuine aspirations for a

university education by completing the high school college

preparatory curriculum was 14.3 in 1986. (P.A. 132a; Exh.

Bd-170) An expert for the United States appropriately charac

terized scores of 10 and 11 as "drastically low" and certainly

not indicative of academic readiness for university instruction.

(P.A. 130a-31a; Exh, Bd-463 at 160-61, J.A. 1304-05)

® The Court should recall when evaluating the petitioners'

admission challenges that the NCAA standard of an ACT score

of 15 plus a 2.0 high school grade average with no exceptions

applies uniformly to universities nationwide. (T. 3584-85, J.A.

1730-31)

13

An ACT regional vice president with extensive expe

rience in utilization of the ACT in college admissions

standards persuasively testified to the reasonableness of

the Board's present standards, including specifically the

use of the ACT. While acknowledging that Board prac

tices may not comport precisely with every ACT sugges

tion, the ACT executive repeatedly emphasized the

reasonableness of the standards. He appropriately evalu

ated the Board's use of the ACT in the context of the

scores required, other educational criteria considered,

and transfer policies. (T. 3698-3710, 3715-33, J.A. 1753-69;

Exh. US-970 at 124-26, 133-34, Dep. Exh. 5) The ACT

executive directly confronted the very ACT-published

statement on which petitioners so heavily rely. In his

professional judgment the admission standards in their

totality (i.e., the inclusion of modest ACT scores, high

school academic achievement as measured by courses

taken, multiple "high risk" criteria such as high school

grades, class rank, extracurricular activities, special tal

ents, and recommendations, and liberal transfer policies)

are consistent with ACT's encouragement of utilization of

criteria in addition to test scores in making admission

decisions. (T. 3735-36, J.A. 1769-70)

Today's admission standards simply cannot be credi

bly attributed to State actions of the now distant early

1960's. The relevant admission standard actions have

been taken by an altogether different Board under totally

different circumstances based upon different, reasonable

educational criteria and with different, reasonable educa

tional objectives. Nothing in Board actions evidences pur

poseful discrimination or any impermissible perpetuation

of ACT utilization.

14

The Board implemented the pertinent admission

standards in 1976 out of a systemwide concern for stu

dent quality. This concern addressed not just the quality

of entering students but also the level of university

instruction and quality of graduates. The Board under

standably lacked confidence in grades due to grade infla

tion and lack of uniform course content in Mississippi

high schools. It selected the ACT test and composite

scores of 15 and 9 only after consultation with ACT.

Moreover, the Board has always viewed the ACT require

ments as modest to terribly low. The Board in any event

has always recognized the substantial presence of open

admission junior colleges and implemented liberal trans

fer policies. (P.A. 121a-23a, 179a; T. 3550-63, J.A. 1717-24;

Exh. Bd-180)

Furthermore, except for Mississippi University for

Women, modifications to the admission standards since

1976 have not included an increase in ACT score require

ment at the predominantly white universities. Rather, the

Board has mandated exceptions to the minimum for

unqualified admission involving multiple education crite

ria. It first confronted the continued inability of low

achieving students to perform adequately in college not

by raising admission standards but by implementation of

costly developmental education programs. The Board

implemented the high school course requirements, a

measure of academic achievement in addition to the ACT,

only after surveying high school educators to confirm the

availability of such a college preparatory curriculum to

all students. (P.A. 123a-25a; T. 3566-67, 3571-81, J.A.

1726-30) Furthermore, all relevant admission standard

actions have been taken at times when the Board's and

15

institutions' substantial commitments to increase minor

ity presence were otherwise evident.

Nor can it be legitimately asserted that the admission

standards discriminatorily affect blacks. Black students

do on the average score somewhat lower on the ACT than

do white students, but a variety of socioeconomic factors,

and not simply race, affect a student's level of academic

development. (P.A. 130a; Exh. Bd-172 at 3, 10; Exh.

US-874 at 7-8) Blacks' disproportionate elections in high

school not to take a college preparatory curriculum con

tribute to the disparity. (P.A. 130a; T. 2284, 2314) Nonethe

less, virtually no black students are denied admission to

the predominantly white universities for low ACT scores.

For example in 1986, Mississippi State University denied

admission to no applicant scoring above 11 on the'ACT;

the University of Mississippi denied admission to only

nine black freshmen applicants who completed the

admission process; and the University of Southern Mis

sissippi has been unable in recent years to fill its quota of

students who score below 15 because of an insufficient

number of applicants whose high school record otherwise

warranted admission. (P.A. 131a; T. 3440-41, J.A. 1688-89;

T. 4165-66, J.A. 1846; Exh. US-964 at 140, 144-45)

The record similarly establishes that utilization of the

ACT composite score of 15 is simply not the cause of the

racial identity of the predominantly black institutions. An

eminently qualified statistician demonstrated at trial that

these institutions are not predominantly black because

black students who first prefer to attend a predominantly

white institution were "channeled" to black universities

after failing to obtain a 15. (P.A. 184a; T. 4228-29, J.A.

16

1859) Moreover, petitioners' conclusory contentions that

the State's use of the ACT "perpetuates duality" wholly

fail to account for the existence of large numbers of

whites who themselves score below 15. Indeed, there are

greater numbers of whites than blacks at such low levels

of academic development who certainly have the same

opportunity as black students to choose a predominantly

black university. (Exh. US-894i, 894j, J.A. 639-40, 645)

The petitioners' challenges to utilization of the ACT

should also be examined in light of the United States

Secretary of Education's confrontation of the well-known

educational crisis facing this Nation. The National Com

mission on Excellence in Education created by the Secre

tary unequivocally recommends that universities "adopt

more rigorous and measurable standards, and higher

expectations, for academic performance and student con

duct . . . and raise their requirements for admission." The

Secretary specifically directs that "standardized tests of

a c h i e v e me n t (not to be c onf us e d wi t h a pt i t ude

tests) . . . be administered . . . particularly from high

school to college . . . to certify the student's credentials."

(Exh. Bd-201 at 9, I f , 12, 27 & 28, J.A. 1216-23) The

admission concerns confronted by the Board over the

past decade and the remedial actions taken are among the

various findings and implementing recommendations of

the Secretary's blue ribbon task force. (T. 3585-91,

3600-02, 3618-20, 3625)

c. Faculty and Staff Employment. At trial petitioners

did not challenge the significant statistical presence of

other-race faculty at the predominantly black univer

sities. The United States abandoned its faculty and staff

employment contentions altogether before the court of

appeals and does so again before this Court. Private

petitioners do continue to allege underrepresentation of

17

black faculty at the predominantly white institutions.

They do so, however, in the teeth of overwhelming proof

of considerable affirmative efforts to attract, employ, and

retain black faculty and in utter disregard of State satis

faction of any realistic statistical expectation.

The predominantly white universities have deployed

a host of strategies to attract and retain qualified black

faculty. (P.A. 136a) For example, they maintain formal

equal employment opportunity and affirmative action

programs and employ equal opportunity officers. (T.

3431, J.A. 1683; T. 3498-99, |.A. 1710; T. 4119, j.A. 1837-38)

Positions are widely publicized in the prominent higher

education publications, including publications of special

minority interest. (Exh. US-758, US-946 at 114, j.A. 772;

US-959 at 14) The universities actively recruit at the grad

uate schools of predominantly black universities, partici

pate in cooperative and faculty exchange programs, and

develop black faculty from the ranks of their own gradu

ate students. The severe financial crisis notwithstanding,

special funds are allocated to minorities for salary incen

tives, supplementation and support. (T. 3425-26, J.A.

1681-83; T. 3947, J.A. 1832; Exh. US-946 at 115, J.A. 772-73;

Exh. Bd-041 at 18, Bd-066 at 19, Bd-067 at 18, Bd-104 at

26-27) The universities prefer minority faculty in applica

tion for faculty housing. (T. 4130-31, J.A. 1844; Exh. Bd.

104 at 25)

There simply is no other recruitment procedure

which the State could implement which would assure

greater minority faculty representation at the predomi

nantly white i ns t i t ut i ons . ( P. A. 199a; T. 3950-51, J.A.

Nor have petitioners attempted to identify any appre

ciably different strategies. They do suggest a faculty

(Continued on following page)

18

1834) Indeed, Mississippi's efforts are very similar to

what institutions are doing in the recruitment of minority

faculty throughout the Nation. This nationwide effort in

higher education to employ minority faculty and admin

istrators understandably significantly hampers the State's

efforts. The vigorous competition of business and indus

try for the extremely limited supply of blacks holding

terminal degrees compounds the difficulty. Moreover, the

State's lower salaries particularly impede employment of

black faculty who, due to high demand, enjoy substantial

leverage in negotiations. The State's competitive disad

vantages likewise make it difficult to retain black faculty

when hired. (P.A. 136a-38a; T. 3425-26, J.A. 1681-83; T.

3940-50, J.A. 1827-34)

The imposing difficulties confronting the predomi

nantly white universities notwithstanding, there is com

pelling statistical evidence of affirmative action in the

hiring process. Since 1974, the percentage of blacks hired

significantly exceeds the black representation in the qual

ified labor pool. Despite the higher turnover rate for

blacks than for whites, black representation statistically

comports with the relevant nationwide labor market for

faculty employed since 1974.” (P.A. 138a, 199a; T.

4237-42, J.A. 1861-65)

(Continued from previous page)

clearinghouse. Yet the State implemented one for a time and it

did not work. (T. 951-53, J.A. 1445-47)

While such statistical evidence does not specifically

apply to administrative positions alone, private petitioners'

administrative staff contentions improperly extricate adminis

tration from the State's overall affirmative nondiscriminatory

employment commitments. Private petitioners also improperly

(Continued on following page)

19

d. Institutional Resources. The State disputes the rele

vance of institutional differences in a diverse statewide

system of public higher education with genuine non-

discriminatory admissions and operational policies. The

United States' comparison of resources according to pre

dominant racial presence notwithstanding, the United

States ultimately agrees that there is no legal obligation

"to correct disparities between what was provided histor

ically black schools - in terms of funding, programs,

facilities, and so forth - and what was provided histori

cally white schools." (U.S. Brief at 32) Private petitioners

still insist, however, that resources must be redistributed

to remedy the alleged "discrimination in resource alloca

tion" to which blacks are subjected. Institutional differ

ences do exist, but the record establishes such differences

do not establish "discrimination." Blacks themselves are

substantial beneficiaries of the educational opportunities

nondiscriminatorily afforded by the comprehensive uni

versities possessed of "superior" resources.

i. M issions. Definition of mission defines institu

tional purpose and scope in relationship to instruction of

students, research and public service. There is no dispute

(Continued from previous page)

emphasize the presence of substantial numbers of black faculty

at the predominantly black universities. The "pull of the

umbilical cord" to return to predominantly black institutions

no doubt substantially contributes to such black faculty pres

ence; many feel very strongly about the preservation of pre

dominantly black institutions; they possess a missionary

commitment to the young blacks in attendance at such institu

tions. (T. 3964-67) In any event this circumstance cannot be

attributed to State failure to expend reasonable efforts to

attract cpalified black faculty to the predominantly white uni

versities.

20

that distinctions in institutional mission are commonplace

within public systems of higher education;^^ jhat the

Board's assignment of differential missions is educa

tionally reasonable; and that the distinctive mission

assignments do not evidence purposeful discrimination.

(P.A. 193a) Private petitioners do erroneously assert that

the 1981 mission designations discriminate against blacks

by preserving a less expansive program scope at the

predominantly black universities.

Again, this private petitioner assertion is first an

institutional contention. It ignores the fact that many

blacks enjoy the educational opportunities at the compre

hensive universities. It is true that the 1981 mission desig

nations limited the predominantly black universities. It is

equally true, however, that the scope of the designations

"put boundaries around all institutions." (T. 3654-56, J.A.

1744-45) Moreover, the 1981 mission designations con

templated a "more comprehensive" status for predomi

nant l y b l ac k J a c k s o n St at e Uni ve r s i t y t han for

predominantly white Delta State University and Missis

sippi University for Women. (Exh. Bd-274, J.A. 1253) Fur

thermore, the Board envisions continued enhancement of

Jackson State University's urban m i s s i o n , including

’2 In the words of one of petitioners' key experts: "The

unique character of American higher education is embodied in

the concept of diversity. Diversity is the quality that differenti

ates among colleges and universities. It is the quality of dis

tinctiveness. This quality says that there is no better or best

kind of collegiate institution; there are only different kinds,

often with different expenses." (T. 608, J.A. 1400-01; Exh.

Bd-459 at 28, J.A. 1284-85)

Jackson State University has also enjoyed past substan

tial mission enhancement. For example, during a 17-year

(Continued on following page)

21

meaningful graduate offerings with an urban emphasis

and increased enrollments of better prepared students. (T.

938-43, ].A. 1442-43; Exh. Bd-274, ].A. 1255-56; Exh.

US-683 at 8-10, J.A, 273-75)

The present missions of the State's universities are a

product of historical development. Yet this circumstance

is true of public institutions everywhere. There was no

comprehensive black university during the de jure era,

but the mere absence today of a major doctoral granting,

predominantly black university does not indicate dis

criminatory mission assignments. Petitioners' own expert

acknowledged that Jackson State is much more compre

hensive than Delta State University and Mississippi Uni

versity for Women. (T. 289, J.A. 1340) While they share

the same mission designation, predominantly black

Alcorn State University is more comprehensive than pre

dominantly white Mississippi University for Women. (T.

272-73) Petitioners offered no evidence addressing the

educational justification for, or the educational feasibility

of, a fourth and predominantly black major doctoral

granting institution or any reassignment of existing insti

tution missions.

ii. Funding. State funding of basic university opera

tions is based upon a formula appropriately tied to the

(Continued from previous page)

period through 1984: student enrollment tripled; faculty size

and quality materially increased; five new schools were estab

lished; the graduate school grew from a single master's degree

in school administration to 35 master's degrees, 15 specialist's

degrees and a doctorate in early childhood education; monu

mental physical expansion occurred. (P.A. 139a; T. 4381-84, J.A.

1877-79) One United States expert went so far as to state that

"Jackson State has made about as much progress as any institu

tion in the country." (Exh. Bd-463 at 108-09, J.A. 1302)

22

educational activities of the respective universities.'"* It is

undisputed that the Board's funding process adheres to

commonly applied, reasonable educational criteria. The

educational expectation is that institutions with greater

program breadth and research emphasis receive greater

funding and thereby reflect the higher per student total

revenues and expenditures. (P.A. 196a)

The Board so explained its funding practices. To fur

ther prove the absence of discrimination the Board com

pared M ississippi's institutions with their regional

"peers." These unchallenged analyses reveal that at least

for the past decade the State's comprehensive universities

have been underfunded when compared to institutions of

similar mission. They further revealed, however, that

Jackson State University and the four regional univer

sities, two of which are predominantly black, have been

overfunded under similar c o mp a r i s o n s . ( R A . 162a; T.

3347-55, J.A. 1677-78) Thus, while funding for the three

comprehensive universities is the predominant basis for

petitioners' assertions, these institutions are the very ones

being treated least favorably financially upon any consid

eration of institutional mission.

Private petitioners fare no better by comparing stu

dents rather than institutions. Their broad allegation

regarding alleged less favorable financial treatment of

black students than white students obviously does not

'"* At the time of trial the academic discipline, student

credit hours, and level of instruction primarily drove the for

mula.

*5 Further, no racial correlation whatever can be inferred

from an analysis of the four institutions designated as regional

universities. Petitioners' comparisons of these institutions with

each other yielded in their own words a "very mixed pattern."

(T. 542-43)

23

hold true under their own premise for the thousands of

black students enrolled in the predominantly white com

prehensive universities. Such an attempted direct focus

upon students, while preferable to the irrelevant institu

tional analyses, nonetheless itself demonstrates an inher

ent fallacy in petitioners' resource contentions. Black

students are allegedly "treated better financially" than

other black students, white students better than other

white students, white students better than some black

students, and black students better than some white stu

dents. (P.A. 196a-97a; T. 640-41, J.A. 1406-07) This would

obviously be true in any system of universities with

differential missions.''’

iii. Programs. Since the mid-1970's the State has sub

jected the quality, number and distribution of academic

programs to much professional study. Doctoral programs

were thoroughly reviewed from 1976 through 1979; they

were again reviewed in 1985 and 1986. All programs

below the doctoral level except certain professional

Petitioners declined to assess the educational justifica

tion for Board allocation of funds or the relative financial

abilities of institutions to fulfill their educational missions.

Further, the alleged "accumulated deficit" is not among the

noncomprehensive universities. There is no correlation by race

among the noncomprehensive universities in funding or with

respect to areas in which funds have historically been

expended. Yet, petitioners' own expert had written prior to his

engagement in this case that comparisons of institutions with

different missions "are largely without merit. They compare

the proverbial 'apples and oranges,' for [such] universities are

not similar; they are expected to do quite different things."

Consequently, in studies before this litigation the expert was

careful to adjust for distinctions in mission when making any

comparisons across mission lines. (T. 604-18, J.A. 1398-1405;

Exh. Bd-459 at 28, J.A. 1285)

24

programs were subject to an extensive six-year review

commenced in 1980. The process involved not just sub

stantial institutional participation but also extensive out

side professional consultation. (P.A. 142a-43a; T. 3602-13,

J.A. 1733-38)

The comprehensive review process resulted in the

elimination of over 450 degree programs. Doctoral offer

ings at the predominantly white comprehensive univer

sities have been reduced 50%. The overall offerings at all

universities have been reduced by 1 /3 with 69% of these

terminated offerings having been at the predominantly

white comprehensive universities. Only 11% of the pro

grams eliminated were at predominantly black institu

tions. (T. 3608-10, J.A. 1736; Exh. Bd-263, Chap. I at 5, J.A.

1244-45) The Board concluded that the programs remain

ing were “of the highest quality possible with the avail

able resources." (Exh. Bd-263 at Introd., J.A. 1237)

The question of unnecessary duplication was of "cen

tral concern" to the Board in the process. The Board was

and remains highly conscious of its statutory charge to

offer " t he broad est p oss ib le educat i onal o p p o r

tunities . . . without inefficient and needless duplication."

(Exh. Bd-263 at Introd., J.A. 1237) Following the review,

the Board concluded further elimination of programs in

significant numbers would both endanger institutional

abilities to fulfill their missions and materially decrease

access to quality academic offerings. (Exh. Bd-263 Chap.

11 at 5, J.A. 1245)

The United States asserts that "Mississippi's unneces

sary duplication of programs at historically white and

historically black schools serves no useful academic func

tion while continuing and reinforcing Mississippi's dual

system of higher education." The United States did not

genuinely attempt, however, to prove such circumstances.

25

Instead, petitioners predicated their challenge upon a

quantitative listing of programs as between the predomi

nantly white and predominantly black universities. Peti

tioners did not evaluate program need, demand, cost,

courses, faculty or level of difficulty of instruction. (T.

256- 57, j.A. 1332-33; T. 266-67, J.A. 1336-37) Petitioners

failed to investigate whether elimination of any addi

tional program would affect access to higher education

for Mississippi citizens. They scrupulously avoided any

judgment as to whether any program should have been

awarded, terminated, consolidated or t r ans f e r r e d. ( T .

257- 58, l.A. 1333)

Petitioners' definition of "duplication" had nothing

to do with the educational rationale for a program's

existence. Petitioners elected to define "duplication" as

any instance where at least one predominantly black uni

versity and one predominantly white university offered

courses in the same HEGIS discipline.’*̂ (T. 268, J.A. 1337)

According to petitioners, "unnecessary" program dupli

cation includes any offering by more than one institution

in any d iscip line outside the basic core arts and

17 Furthermore, petitioners' institutional comparisons

were not even based upon educational criteria but rather upon

mere racial identifiability of institutions. Indeed, the witness

"could not think" of any alleged basis but race for his group

comparisons of the three predominantly black universities

with the five predominantly white universities. (T. 263-64, J.A.

1335-36) He, however, "said nothing at all about the reasoning

or motivation" underlying program actions. (T. 266, J.A. 1336)

18 "HEGIS" refers merely to a classification system fre

quently used in higher education to identify the general subject

matter of programs. It does not address the specifics of course

content, instruction or other fundamentals which would reflect

the actual scope of the program. (T. 73-74)

26

sc ien ces .P e tit io n ers also maintained that all duplication

at the master's level, regardless of discipline, is unnecess

ary. (T. 275-76, J.A. 1338-39) Thus, they advanced a statis

tically meaningless concept of common curricula within

the system. Every institution duplicates other institu

tions.

The record clearly reveals there is no pattern of

duplication associated with the racial identification of

institutions. There is no more duplication between the

predominantly black institutions and the predominantly

white institutions than one would expect to find when

comparing any three institutions with any five institu

tions regardless of racial identification. Among the non-

comprehensive universities, the three predominantly

black universities are duplicated less than any other set

of noncom prehensive inst i tutions. (T. 4198-99, J.A.

1851-52; T. 4203-04)

Petitioners' distinctions in program quality or pur

ported findings of program inequality are also solely

This wholly unrealistic definition means that petitioners

considered any instance of a predominantly black and predom

inantly white university offering a course in, for example,

business and commerce, accounting, business statistics, bank

ing and finance, investment and securities, business manage

ment and administration, real estate, insurance, elementary

education, or secondary education to be "unnecessary" pro

gram duplication. Stated differently, eight institutions could

offer Russian, anthropology, or astrophysics without unnecess

ary duplication, but no two institutions could offer accounting,

banking and finance or secondary education. (T. 275-77, J.A.

1338-39)

20 The Board proved there are some 162 dual curricular

systems in Mississippi under petitioners' definition. (T.

4197-98, J.A. 1851)

27

functions of institutional mission. The differences in peti

tioners' measures of program quality are not associated

with race, but simply demonstrate the difference between

com prehensive anci noncomprehensive universities.

There is no pattern among the noncomprehensive univer

sities with respect to race. (T. 4206-07, J.A. 1852-53) Fur

ther, the pattern of program reduction resulting from

program review has been less among the predominantly

black institutions than among the predominantly white

institutions. (T. 4213-14, J.A. 1853-54)

Private petitioners challenge the State's land grant

programs because the predominantly white Mississippi

State University possesses greater land grant resources

than predominantly black Alcorn State University. Deseg

regation within Mississippi's land grant community is

clearly not their focus. They ignore the blacks studying

agriculture at MSU. They did not even attempt to address

the motive, intent, good faith or educational justification

underlying the State's present allocation of land grant

resources. (T. 835-41, J.A. 1428-31) It was the State, and

not petitioners, who pursued USDA input in this pro

ceeding. Through the former administrative heads of the

USDA's Cooperative State Research Service and Exten

sion Service, the State proved its operation of these two

fundamental programs was entirely consistent with

USDA policies and practices.^’ (T. 3123-29, 3142-46, J.A.

21 These findings likewise rebut the United States one-

sentence challenge alleging “extraordinary duplication."

Under federal oversight the two universities jointly developed

a single comprehensive program of agricultural research for

the State. (P.A. 154a; T. 3104, J.A. 1414-15; T. 3142-46, J.A.

1664-67) The Extension Service of the USDA has insured that

the two universities' extension programs are supplementary

and not duplicative. (T. 3284, J.A. 1672) See Exh. Bd-263 at

Chapter II (Board explanation for agriculture programs).

28

1661-67; T. 3295-99, J.A. 1673-76) The record plainly estab

lishes that land grant resources have been non-

discriminatorily allocated consistent with legitimate

educational and federal government criteria .22 (P.A.

150a-56a, 198a)

iv. Facilities. Private petitioners' facilities conten

tions perhaps prove better than any other their refusal to

acknowledge that substantial State efforts eventually sat

isfy the duty to disestablish, no matter how defined. The

record makes clear no racial inference can be drawn from

the distribution of facilities. (P.A. 163a-66a, 195a; T.

3862-98, J.A. 1806-15) Jackson State University's president

attested to the "monumental physical expansion" enjoyed

by the institution during his 17 year tenure, (supra at

20-21 n .l3) Petitioners' own expert readily admitted;

"There has been equitable treatment in recent years" of the

predominantly black institutions, for "it's clear that physi

cal facilities resources in the past 30 years in Mississippi

have been allocated equitably from the viewpoint of

racial characteristics of the institutions." (T. 493-94, J.A.

1379) Petitioners' assertion of the "inferior character" of

the predominantly black universities' facilities is at most

a function of institutional mission. They do not bother to

dispute, apart from their mission challenge, the district

22 Petitioners' references to program offerings at off-

campus centers are misleading and pointless. The Board has

almost entirely curtailed predominantly white institution par

ticipation in off-campus centers. Indeed, Board actions were

such that petitioners limited their "off-campus center" proof to

the pre-1981 period. Despite the district court's stated expecta

tion and United States counsel's assurance that any such peti

tioner contentions would be brought current, petitioners failed

to do so. (T. 938-40, J.A. 1442-43; T. 3432-35, J.A. 1683-86; T.

77-79, 251-53; Exh. U.S. 757)

29

court's finding that these universities possessed facilities

of a "character" commensurate with their mission. (P.A.

166a)

3. The District Court's Decision. The district court

conducted a five-week bench trial and comprehensively

considered the testimony of 71 witnesses and some 56,700

pages of exhibits. (P.A. 109a) The court ultimately held

that the "current actions on the part of the [State] demon

strate conclusively that the [State is] fulfilling [its] affirma

tive duty to disestablish the former de jure segregated

system of higher education." (P.A. 201a) In so holding,

the court flatly stated that "the affirmative duty to dis

mantle a racially dual structure in the elementary and

secondary levels applies also in the higher education

context." (P.A. 170a-71a) Recognizing, however, the dis

tinct attributes of higher education, the court declined to

find any "level of racial mixture" to be "necessary to

'effectively' desegregate the system." (P.A. 171a) Nev

ertheless, the court plainly concluded that student enroll

ment, faculty employment, and staff hiring patterns must

be exam ined. It sim ply determ ined that "greater

emphasis, should instead be placed on current state

higher education policies and practices in order to insure

that such policies and practices are racially neutral,

developed and implemented in good faith, and do not

substantially contribute to the continued racial identi-

fiability of individual institutions." (P.A. 177a)

The court found that the State had indeed imple

mented "race-neutral policies and procedures" involving

student admission, student recruitment, faculty employ

ment, staff hiring, and resource allocation. Moreover, the

court concluded the State "[has] also undertaken substan

tial affirmative efforts in the areas of other-race student

and faculty-staff recruitment and funding and facility

30

allocation."23 (RA. 201a) The court noted petitioners'

institutional enhancement claims sounded much like the

assertion of Fourteenth Amendment rights on behalf of

state political subdivisions, rights which just do not exist.

(P.A. 190a-91a) Nonetheless, the court made the institu

tional analyses suggested by petitioners but found no

disparities in resources related to the "racial identi-

fiability" of institutions.

23 Among its many specific factual findings substantiating

its ultimate conclusions, the district court found with respect to

student admission and recruitment; (i) the State's current

admission policies were adopted for nondiscriminatory pur

poses and are "inherently reasonable and educationally sound"

(RA. 179a, 181a, 185a); (ii) "the State has used every reasonable

means at its disposal in its recruitment efforts" (P.A. 187a); and

(iii) the continued identifiability of institutions by student

racial makeup is the "result of a free and unfettered choice on

the part of individual students." (P.A. 187a) The court likewise

concluded that no "additional minority faculty and staff

recruitment procedures" exist which the State "could imple

ment which would assure greater minority faculty and staff

representation at the predominantly white institutions and

minority staff representation with the Board of Trustees' own

organization." (PA. 199a)

24 For example, the court's factual findings included: (i) "the

current mission designations are rationally based on sound educa

tional policies" (P.A. 193a); (ii) petitioners failed fo prove any

placement of academic programs associated with race or that any

program reallocation "would be feasible, educationally reasonable,

or would offer any hope of substantial impact on student choice"

(P.A. 194a); (iii) no racial pattern exists with respect to the provi

sion or condition of physical facilities (P.A. 195a); (iv) "while

differences in level of funding obviously exist, these differences are

not accountable in terms of race, but rather are explained by

legitimate educational distinctions among institutions" (PA. 196a);

and (v) the differentiations made in land grant programs are

"educationally sound and are not motivated by discriminatory

motive." (P.A. 198a)

31

4. The Court o f Appeals' D ecision. The court of

appeals plainly stated at the outset of its opinion the

ultimate basis for its affirmance; "Finding that the record

makes clear that Mississippi has adopted and implemented

race neutral policies for operating its colleges and univer

sities and-that all students have real freedom of choice to

attend the college or university they wish, we affirm."

(P.A. 2a) (emphasis added). Like the district court, the

court of ap p eals acknow led ged that "M iss iss ip p i

was . . . constitutionally required to eliminate invidious

racial distinctions and dismantle its dual system." (P.A.

13a) Similar to the district court, the appellate court

emphasized, however, that "universities are not simply

institutions for advanced education. They differ in char

acter fundam entally from primary and secondary

schools." (P.A. 23a) The court concluded that delineation

of the duty to disestablish must necessarily honor the

distinctive attributes of higher education, particularly

freedom of choice and institutional diversity. (P.A.

23a-26a) The appellate court read Bazemoref^^ in conjunc

tion with ASTA,'^^ to be the proper assessment of this

" 'wholly different milieu' of a voluntary association."

(P.A. 25a) Because Mississippi, in thought, word and

deed, discontinued "prior discriminatory practices" and

adopted and implemented "good-faith, race-neutral poli

cies and procedures," the court of appeals held that the

State had satisfied its affirmative duty to disestablish.

(P.A. 26a)

It cannot be overlooked that the court of appeals did

not stop with definition of the legal duty to disestablish;

25 Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986).

26 Alabama State Teachers Ass'n v. Alabama Public School and

College Auth., 289 F. Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala. 1968), aff'd per curiam,

393 U.S. 400 (1969).

32

it scrutinized the record to assure the presence of, and the

use and encouragement of, genuine good-faith, race-neu

tral policies which afford "real freedom of choice." The

court saw two components of the system as bearing most

directly on the presence of "true" student choice; institu

tional mission designation and student admissions poli

cies. The court of appeals found "the record amply

supports the findings of the district court that the [insti

tutional mission] designations are commonly used, edu

cationally sound, and not motivated by discriminatory

intent." (P.A. 31a) The court held "the district court gave

full consideration to all aspects of the admissions pro

cess"; and it concluded district court findings that the

"current admissions policies and procedures in effect in

Mississippi universities were adopted and developed in

good faith and for nondiscriminatory purposes" were not

clearly erroneous. (P.A. 34a-35a)

The en banc court also found statistical parity in

respondents' faculty employment, noted the genuine

commitment to increase black employment at the pre

dominantly white universities, and acknowledged the

substantial d ifficulties inherent in minority faculty

recruitment. (P.A. 35a-36a) The court of appeals had

"nothing to add" to district court findings concerning

alleged "disparities between the historically black and

historically white institutions regarding program offer

ings and duplication among universities and branch cen

ters, faculty, funding, library volumes, facilities, and land

grant programs," with only one exception. (P.A. 36a) The

court of appeals did find institutional "disparities" today

to be "reminiscent" of the segregated system, but only in

the sense that present institutional mission designations

cannot be totally extricated from an institution's past. The

court stated that such institutional distinctions do not

33

"den[y] equal educational opportunity or equal protec

tion of law/' for respondents "have adopted good-faith,

race-neutral policies and procedures and have fulfilled or

exceeded their duty to open Mississippi universities to all

citizens regardless of race." (P.A. 37a) (emphasis added).

The en banc court rejected outright the private petitioner

suggestion that such institutional differences require

resource allocations to universities according to race to

make the predominantly black universities "equal" to the

predominantly white comprehensive universities. (P.A.

37a)

SUM M ARY OF ARGUM ENT

The legal principles which govern this controversy

are not best analyzed in the abstract. They are inextrica

bly tied to the facts in Mississippi. Just as Mississippi

once promoted an unconstitutional system of higher edu

cation with schools of higher learning reserved solely for

whites or solely for blacks, the State now affords real

freedom of choice extending to all students and to all

schools. Today's system, in policy and in fact, provides

open, unimpeded access for all with no barrier on

account of race. More than mere race neutral policy pre

vails; for most of two decades there has been admirable

State encouragement directed to desegregation. It may be

that Mississippi was not required to go beyond adoption

and implementation of race neutral policies so as to pro

mote and encourage the exercise of choice in favor of an

"other-race" institution. But it did. Thus, the State does

not have the burden of arguing a legal standard applica

ble to less persuasive facts.

The duty imposed on Mississippi to dismantle or

disestablish its former system of de jure segregation has

34

been fulfilled. Mississippi's existing system is constitu

tional because there is no evidence of present intentional

discrimination. Continuing racial identifiability of institu

tions resulting from individual student choice does not

equate to unconstitutionality because the constitutional

vice of state-imposed segregation has been eliminated.

There exists unfettered, individual choice in Mississippi.

The trial record reflects a commitment to the operation of

a statewide system dedicated to the enhancement of inte

grated higher education opportunities coupled with the

goal of quality education.

Bazenwre best speaks to the fulfillment of the State's

duty to disestablish in a setting, i.e., public higher educa

tion, where individual choice traditionally plays a signifi

cant role and, indeed, is consistent with laudable

edu cational o b jectives . Bazernore heeds M cLaurin .

Bazenwre honors Brown. Bazernore appropriately distin

guishes Green. Equal protection is a fact where equal

opportunities afforded by the State are genuinely avail

able to all on equal terms. Neither the Constitution nor

Title VI require more than the fact of equal protection.

The United States challenges the standards for

admission to the respective universities but in doing so,

necessarily ignores the record. Present-day admissions

standards exist for reasons unrelated to the "Meredith

era." Even so, they are distressingly modest. The evi

dence is that virtually all black applicants to predomi

nantly white universities are accepted. There is no

evidence that black students are forced to apply to a

predominantly black university. Admission standards are

no more unconstitutional "vestiges" or "remnants" of

past de jure segregation than class attendance and class

examination requirements.

35

The United States contends, again in the teeth of the

findings below, that there are so-called "duplicative" pro

grams in place which arguably impede further desegrega

tion. Stripped of rhetoric, the contention is that it is

unconstitutional for a single predominantly black and a

single predominantly white university to both offer a

course in business or education. A choice among institu

tions which offer business and education is no more an

unconstitutional "vestige" or "remnant" than a choice

between institutions which offer English, history, mathe

matics, social studies and science.

The private petitioners alone continue to press for

more than free choice among all institutions including the

comprehensive universities. The United States does not

join in the suggestion of the private petitioners that black

students have a constitutional right not only to choose a

predominantly black institution but also a constitutional

right upon enrollment to find buildings, grounds, pro

grams and accoutrements equal to the comprehensive

university the students could have chosen in the first

place. Putting aside questions of educational policy and

educational reasonableness or financial capability, the

assertion that the Court must compel the State to provide

at least equal resources to schools with a predominantly

black population as a matter of constitutional or statutory

necessity deserves short shrift.

36

ARGUM ENT

I. Mississippi has fulfilled its duty under the Four

teenth A m endm ent to disestablish state-imposed

segregation in higher education through the adop

tion and years of implementation of good-faith, gen

uinely n on d iscrim in atory policies which do not

contribute to institutional racial identifiability.

A. The constitutional duty to disestablish state-

imposed segregation in higher education may