Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, Inc. Brief for the Petitioners

Public Court Documents

June 30, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, Inc. Brief for the Petitioners, 1972. 4d7c8935-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6987c5b5-3955-46b7-b60c-4c6a432b568f/tillman-v-wheaton-haven-recreation-association-inc-brief-for-the-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

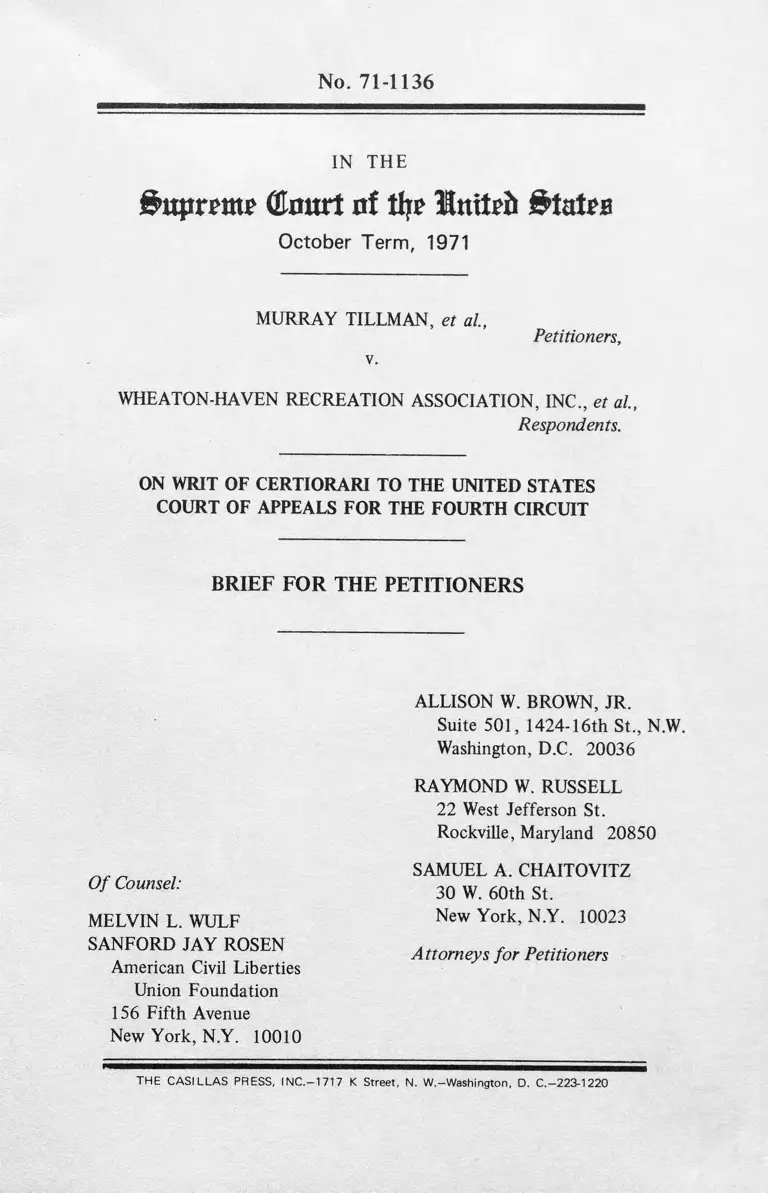

No. 71-1136

IN THE

grtpremr (Erwrt af % Intitb &tat£B

October Term, 1971

MURRAY TILLMAN, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

WHEATON-HAVEN RECREATION ASSOCIATION, INC., et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

Of Counsel:

MELVIN L. WULF

SANFORD JAY ROSEN

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10010

ALLISON W. BROWN, JR.

Suite 501, 1424-16th St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

RAYMOND W. RUSSELL

22 West Jefferson St.

Rockville, Maryland 20850

SAMUEL A. CHAITOVITZ

30 W. 60th St.

New York, N.Y. 10023

Attorneys for Petitioners

THE C A S IL L A S PRESS, IN C .-1717 K Street, N. W.-Washington, D. C.-223-1220

INDEX

OPINIONS BELOW..................................................................... 1

JURISDICTION.......................................................................... 2

QUESTION PRESENTED ....................................................... 2

STATUTES INVOLVED........................................................... 2

STATEMENT ................................................................................ 4

A. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association,

Inc.-its purpose and manner of

o p e ra tio n ........................................................... 4

B. Wheaton-Haven’s racially discriminatory

membership and guest policies......................... 6

C. Proceedings below . ........................................ 7

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT................................................. 8

ARGUMENT............................................................................... 10

I. Wheaton-Haven’s racially discriminatory

policies violate the Civil Rights Act of

1866 (42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1 9 8 2 ) .............................. 10

A. The remedy provided by the Act

of 1866 for racially discriminatory

conduct should be broadly construed . . . 10

B. Rights secured to petitioners by the

Act of 1866 are violated by Wheaton-

Haven’s racially discriminatory member

ship and guest policies. . . . . . . . . 17

(i)

Page

C. Wheaton-Haven lacks the character

istic of exclusiveness associated with

a truly private club, since member

ship is open to all residents of the

area prescribed by its b y -law s......................... 20

D. There are no valid grounds for dis

tinguishing this case from Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park ........................................ 24

II. Wheaton-Haven’s racially discriminatory

policies violate the Civil Rights Act of

1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000a)........................................... 27

CONCLUSION.......................................................................... 29

CITATIONS

Cases:

American Universal Insurance Co.

v. Scherfe Insurance Agency,

135 F. Supp. 407 (S.D. Iowa, 1 9 5 4 ) .............................. 30

Barrows v. Jackson,

346 U.S. 249 ( 1 9 5 3 ) ........................................................... 23

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine

Contracting Co.,

437 F.2d 1011 (C.A. 5, 1971)................................................ 16

Brady v. Bristol-Meyers, Inc.,

decided May 8, 1972, 4 FEP Cases 749 (C.A. 8) . . . 16

Brown v. Balias,

331 F. Supp. 1033 (N.D. Tex., 1 9 7 1 ) .........................16, 30

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F.2d 1377 (C.A. 4, 1972)

(ii)

Page

16

(iii)

Civil Rights Cases,

109 U.S. 3 (1 8 8 3 ) ................................................................ 12

Collyer v. Yonkers Yacht Club,

17 A.D.2d 973,

234 N.Y.S.2d 259 ( 1 9 6 2 ) ................................................. 19

Daniel v. Paul,

395 U.S. 298 ( 1 9 6 9 ) .................................................. 21, 27, 28

Grier v. Specialized Skills, Inc.,

326 F. Supp. 856 (W.D., N.C., 1 9 7 1 ) .............................. 16

Hitchcock v. American Plate Glass Co.,

259 Fed. 948 (C.A. 3, 1 9 1 9 ) ............................................ 30

Hyde v. Woods,

4 Otto 523 (1877 )................................................................ 18

International Brotherhood o f Electrical Workers

v. National Labor Relations Board,

341 U.S. 694 ( 1 9 5 1 ) ........................................................... 28

Jones v. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ................................... 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Knight v. Auciello,

453 F.2d 852 (C.A. 1, 1 9 7 2 ) ........................................ 16, 29

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.,

429 F.2d 290 (C.A. 5, 1970),

444 F.2d 143 (C.A., 1 9 7 1 )............................................ 16, 29

Lobato v. Pay Less Drug Stores, Inc.,

261 F.2d 406 (C.A. 10, 1958)............................................ 30

McLaurin v. Brusturis,

320 F. Supp. 190 (E.D.Wis., 1 9 7 0 ) ................................... 16

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

394 F.2d 342 (C.A. 5, 1968)

Page

28

National Cash Register Co. v. Leland,

94 Fed. 502 (C.A. 1, 1899),

cert, denied, 175 U.S. 724 .................................................. 30

National Fire Insurance Co. v. Thompson,

281 U.S. 331 ( 1 9 3 0 ) ........................................................... 24

National Labor Relations Board v. The Austin Co.,

165 F.2d 592 (C.A. 7, 1 9 4 7 ) ............................................ 28

National Labor Relations Board

v. Local 1423, United Brotherhood o f Carpenters,

238 F.2d 832 (C.A. 5, 1 9 5 6 ) ............................................ 28

National Labor Relations Board v.

National Survey Service,

361 F.2d 199 (C.A. 7, 1 9 6 6 ) ............................................ 28

Nesmith v. Y.M.C.A. o f Raleigh, N.C.,

397 F.2d 96 (C.A. 4, 1 9 6 8 ) ........................................ 21, 29

Page v. Edmunds,

187 U.S. 596 ( 1 9 0 3 ) ........................................................... 18

Rockefeller Center Luncheon Club, Inc. v. Johnson,

131 F. Supp. 703 (S.D.N.Y., 1 9 5 5 ) ................................... 21

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc.,

431 F.2d 1097 (C.A. 5, 1970)............................................ 16

Scott v. Young,

421 F.2d 143 (C.A. 4, 1970),

cert, denied, 398 U.S. 929 ............................................ 16, 28

Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1 9 4 8 ) ................................................................ 23

(iv)

Page

Smith v. Sol D. Adler Realty Co.,

436 F.2d 344 (C.A. 7, 1971) 16, 29

(V)

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park,

396 U.S. 229 (1969) . . . . 2, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19,

20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery,

307 F. Supp. 369 (N.D.Ala., 1 9 6 9 ) ................................... 16

Trounstein v. Bauer, Pogue & Co.,

144 F.2d 379 (C.A. 2, 1944),

cert, denied, 323 U.S. I l l ................................................. 30

United States v. Central Carolina Bank & Trust Co.,

431 F.2d 972 (C.A. 4, 1 9 7 0 ) .........................' 28

United States v. Pink,

315 U.S. 203 ( 1 9 4 2 ) ........................................................... 24

United States v. Richberg,

398 F.2d 523 (C.A. 5, 1 9 6 8 ) ............................................ 21

Walker v. Pointer,

304 F. Supp. 56 (N.D.Tex., 1 9 6 9 ) ................................... 19

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

427 F.2d 476 (C.A. 7, 1970),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 9 1 1 ................................................. 16

Williamson v. Hampton Management Co.,

339 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D., 111., 1 9 7 2 ) .............................. 30

Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co

438 F.2d 757 (C.A. 3, 1 9 7 1 ) .........................i 6

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

Thirteenth Amendment to the C o n s titu tio n ....................12, 14

28 U.S.C. §1254(1)

Page

1

(Vi)

42 U.S.C. §1981........................................2, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13,

15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 27, 28, 29

42 U.S.C. §1982 ........................................ 2, 3, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12,

14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 27, 28, 29

42 U.S.C. §2000a........................................2, 3, 7, 10, 15, 27, 28

42 U.S.C. § 2 0 0 0 e ..................................................................... 16

42 U.S.C. §3601 ........................................................................... 14

Internal Revenue Code,

26 U.S.C. §501 ( c ) ( 7 ) ........................................................... 6

Maryland Code Annotated Art. 81,

§288(d)(8)............................................................................... 6

Page

Miscellaneous:

Larson, The Development of §1981 as a

Remedy for Racial Discrimination in Private

Employment, 7 Harv. Civ. Rights L. Rev.

56 (1 9 7 2 ) ............................................................................... 16

17 Am. Jur. 2d,

Contracts §§302-319 20

Restatement (Second) of Torts

§§330, 332 ( 1 9 6 5 ) ................................................................ 19

(Washington) Evening Star,

April 25, 1969 ..................................................................... 17

Washington Post,

January 12, 1967 17

IN THE

Supreme (tort nt tlj? llnttpii &tat£B

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1136

MURRAY TILLMAN, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

WHEATON-HAVEN RECREATION ASSOCIATION, INC., et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS1

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals (Pet. App. B1 -B31)2

is reported at 451 F.2d 1211. The District Court’s opinion

(Pet. App. Cl-Cl 3) is unreported.

1 Petitioners, in addition to Murray Tillman, are Rosalind N. Tillman,

his wife, Dr. Harry C. Press and Francella Press, his wife, and Mrs. Grace

Rosner. Respondents, in addition to Wheaton-Haven Recreation, Inc.,

are Bernard Katz, Philip S. Trusso, Sidney M. Plitman, Anthony J. De

Simone, Brian Carroll, Albert Friedland, Mrs. Robert Bennington, Mrs.

Anthony Abate, Richard E. McIntyre, James V. Welch, Mrs. Ellen Fen-

stermaker, Walter F. Smith, Jr. and James M. Whittles, individuals who

were officers and/or directors of said corporation at times material herein

(A. 8, 23).

2 64“Pet. App.” refers to the appendix to the petition for a writ of cer

tiorari. “A.” refers to the separate appendix to the briefs.

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on

October 27, 1971. A petition for rehearing and sugges

tion for rehearing en banc was duly filed and the court

of appeals entered its order of denial on December 16,

1971 (A. 40). The petition for a writ of certiorari was

filed on March 13, 1971, and was granted on May 15,

1971. The jurisdiction of this court rests on 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the court of appeals erred in holding a com

munity recreation association to be a private club and

hence exempt from civil rights statutes which prohibit

racial discrimination (42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982 and 42

U.S.C. §2000a), despite the fact that this Court in a pre

vious case (Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229

(1969)) held that an association with virtually identical

characteristics could not lawfully discriminate on the basis

of race with respect to persons seeking to use its facilities.

STATUTES INVOLVED

The relevant provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

as incorporated in 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982, are as follows:

§1981. All persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the same right

in every State and Territory to make and en

force contracts * * * as is enjoyed by white

citizens * * * .

3

§1982. All citizens of the United States shall

have the same right in every State and Terri

tory, as is enjoyed by white citizens thereof to

inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property.

The relevant provisions of Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1946 (42 U.S.C. §2000a) are as follows:

§201(a) (42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000a(a)). All per

sons shall be entitled to the full and equal en

joyment of goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations of any place

of public accommodations as defined in this

section, without discrimination or segregation

on the ground of race, color, religion, or na

tional origin.

§201 (b) (42 U.S.C. §2000a(b)). Each of the

following establishments which serves the public

is a place of public accommodation within the

meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce * * * ;

* * *

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert

hall, sports arena, stadium or other place of ex

hibition or entertainment; * * *

* * *

§201 (c) (42 U.S.C. §2000a(c)). The operations

of an establishment affect commerce within the

meaning of this title if * * * (3) in the case

of an establishment described in paragraph (3)

of subsection (b), it customarily presents films,

4

performances, athletic teams, exhibitions, or

other sources of entertainment which move in

commerce; * * *

* * *

§201(e) (42 U.S.C. §2000a(e)). The provis

ions of this title shall not apply to a private

club or other establishment not in fact open

to the public * * *

* * *

STATEMENT3

A. WHEATON-HAVEN RECREATION ASSOCIATION,

INC.- ITS PURPOSE AND MANNER OF OPER

ATION

Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, Inc. is a non

profit Maryland corporation organized in 1958 for the

purpose of operating a swimming pool in an area of Sil

ver Spring, Maryland (Pet. App. C l; A. 7-8, 23). The pool

was financed by subscriptions for membership collected

from persons residing in the area. The pool presently

charges a $375 initiation fee and an annual dues of $150-

$160 (Pet. App. C1-C2; A. 44). The by-laws of the as

sociation provide that membership “shall be open to bona

fide residents (whether or not homeowners) of the area

within a three-quarter mile radius of the pool” (Art. Ill,

§1, Pet. App. C2; A. 43). Members may be taken from

̂ The facts stated herein are based on the district court’s find

ings as modified by the court of appeals.

5

outside the three-quarter mile radius upon the recommen

dation of a member as long as members from outside the

area do not exceed 30 percent of the total membership

(Pet. App. C2; A. 43)5 In either event, the by-laws pro

vide that applicants for membership must be approved by

“an affirmative vote of a majority of those present at a

regular membership meeting, or a regular meeting of the

Board of Directors, or a special meeting of either group

called for this purpose” (Art. Ill, §3, Pet. App. C2; A. 43).

Membership, which is by family units rather than by in

dividuals, is limited to 325 families (Art. Ill, §§6, 7, Pet.

App. C2; A. 43-44). If a member who is also a home-

owner sells his property and resigns his membership, his

purchaser receives a first option to purchase his member

ship, subject to the approval of the Board of Directors

(Art. VI, Pet. App. C2; A. 47).

Only members and their guests are admitted to the pool.

Members of the general public cannot gain admittance by

payment of an entrance fee (Pet. App. C2-C3; A. 42-43).

The Wheaton-Haven pool was constructed in 1958-1959

by a contractor from outside the State of Maryland (Pet.

App. C3; A. 9, 23, 87, 92). The pool’s operation involves

the use of pumps, a motor and a chlorine feeder, all manu

factured outside of Maryland. There are also snack vend

ing machines. All of these facilities are in an enclosed

area accessible only to members and their guests (Pet. App.

C3; A. 41, 122-123).

^ At times when the membership rolls are full, applicants for

membership are limited to the geographic area within a three-quarter

mile radius of the pool, and such applications are considered in chro

nological order of receipt (Art. V, §3, A. 46).

6

The pool was constructed pursuant to a “special excep

tion” granted by the Montgomery County Board of Ap

peals under the county’s zoning ordinance (Pet. App. C3-

C4; A. 8, 23, 96, 98).5 Prior to granting the exception,

the zoning authority required Wheaton-Haven to demon

strate its financial responsibility by submitting evidence

that 60 percent of its projected construction costs were

obligated or subscribed (A. 96, 99).

Wheaton-Haven pays state and local property taxes, but

is exempt from state and federal income taxes under Mary

land Code Ann. Art. 81, §288(d)(8), and §501(c)(7) of the

Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. §501 (c)(7)) exempting

non-profit, membership-owned and controlled recreational

facilities (Pet. App. C4; A. 97, 99).

B. WHEATON-HAVEN’S RACIALLY DISCRIMINA

TORY MEMBERSHIP AND GUEST POLICIES

Dr. and Mrs. Harry C. Press, two of the Negro plaintiffs,

own a home within the three-quarter mile radius of the

pool (Pet. App. C3; A. 11-12). The previous owner of

the home was not a member of Wheaton-Haven. In the

spring of 1968, Dr. Press sought to obtain a membership

application from members of the association’s Board of

Directors, who declined to furnish him with an application

5 The provisions of the zoning ordinance applicable to Wheaton-

Haven was enacted by the Montgomery County Council as Ordinance

No. 3-28, dated May 24, 1955. In the ordinance, the Council stated,

“ . . . this action sets up the community swimming pools as a special

exception . . . Council strongly endorses the interests of the various

communities in attempting to organize and promote their own recre

ational facilities, and believes that the County will be generally bene

fited by such development” (A. 9, 62, 96, 98).

7

(Pet. App. C3; A. 11, 97, 99). The stipulated reason for

their refusal was his race (Pet. App. C3; A. 90, 95).

Mr. and Mrs. Murray Tillman are white members of

Wheaton-Haven. On July 19, 1968, the Tillmans brought

Mrs. Grace Rosner, a Negro, to the pool as their guest.

She was admitted (Pet. App. C3; A. 12). The following

day, at a special meeting, the Board of Directors promul

gated a rule limiting guests to relatives of members (Pet.

App. C3; A. 12, 97, 99). Mrs. Rosner has been refused

admission as a guest of the Tillmans since then (Pet. App.

C3; A. 12, 90, 95). The new guest policy was adopted

in response to the Tillman’s bringing a Negro guest to the

pool, though it was intended also to reduce the burgeoning

number of guests using the pool (Pet. App. C3; A. 12, 90,

95, 115-117).6

At a meeting of the association’s members in the fall of

1968, a resolution was adopted reaffirming Wheaton-Haven’*

policy of not admitting Negroes to its facilities (Pet. App.

B30; A. 109, 90, 95).

C. PROCEEDINGS BELOW

Petitioners brought their complaint in the United States

District Court for the District of Maryland, seeking decla

ratory and injunctive relief, as well as damages. They

claimed that Wheaton-Haven’s racially discriminatory policies

violated their rights under the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982 and under the Civil Rights Act of

1964 (42 U.S.C. 2000a).

The district court (Northrop, J.) denied the relief sought

by plaintiffs, and granted summary judgment to defendants

below (Pet. App. Cl-Cl 3). Before the court of appeals,

8

plaintiffs’ motion for summary reversal was denied, and

following consideration of the merits, a majority of the

panel (Haynsworth, Chief Judge, and Boreman, Circuit

Judge) affirmed the district court, holding that Wheaton-

Haven is a “private club” and hence exempt from the

Civil Rights Act of 1866 as well as the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (Pet. App. B1-B23). Judge Butzner, dissenting,

would have granted plaintiffs motion for summary rever

sal of the district court. He found the case to be “indis

tinguishable in all material aspects” from Sullivan v. Little

Hunting Park, supra, and hence termed the majority deci

sion “a marked departure from authoritative precedent”

(Pet. App. B23). Judges Winter and Craven dissented from

the court’s denial of rehearing en banc, and expressed

their agreement with Judge Butzner’s view that the case

is indistinguishable from Sullivan (Pet. App. B31). Finally,

all three dissenting judges deplored the majority’s holding

that the 1866 Act was impliedly repealed in part by the

1964 Act.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case involves the question whether a community

recreation association established to operate a swimming pool

for the benefit of all residents of a neighborhood may exclude

persons otherwise eligible on the basis of race. In Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park, supra, 396 U.S. 229, the Court

held that such an association, which has no other criteria

for membership than residence within a prescribed area, is

not a “private club” because it lacks a “plan or purpose

of exclusiveness,” and therefore is subject to applicable

laws prohibiting racial discrimination.

Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, Inc., whose ra

cially discriminatory membership and guest policies are at

9

issue here, is typical of many such non-profit associations

organized in suburban neighborhoods by residents who con

tribute their time and energy to establish neighborhood rec

reational facilities for themselves and their families. Whea-

ton-Haven’s by-laws specify that membership in the associ

ation is open to everyone residing within a three-quarter

mile radius of its swimming pool. Community recreation

facilities, particularly a swimming pool, obviously are a

major factor affecting the desirability and attractiveness

of residential property. The availability of such facilities

for all white residents of a neighborhood and the routine

exclusion of Negroes, will both discourage the latter from

buying in that community and make any purchase they

do make a poorer bargain than a white citizen could ob

tain. To thus allow an association such as Wheaton-Haven

to exclude Negroes from community recreation facilities

places in the hands of this private group the power to

control the racial composition of a neighborhood, a result

comparable to enforcement of a racially restrictive cove

nant.

The close relationship between membership in Wheaton-

Haven and the ownership of property in the neighborhood

served by the pool is shown by the provision of the associ

ation’s by-laws giving a member who sells his home the

right to make his membership available for purchase by

the buyer of his home, despite the fact that there may be

a waiting list of persons who have been seeking member

ships for a substantial period of time. This nexus between

membership in the pool and the passage of title to real

property in the neighborhood which it serves, and the fact

that the home buyer in such circumstances has priority in

obtaining a membership over those on the waiting list, evi

dences the fact that the organizers of Wheaton-Haven were

well aware that the availability of a pool membership

10

would add to the attractiveness and value of their homes.

This provision of Wheaton-Haven’s by-laws refutes any claim

of exclusiveness the association might make, since one’s eligi

bility for membership in such circumstances is entirely a func

tion of who he buys his house from.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982)

protects Negroes against private acts of discrimination in

transactions based on contract, and in matters involving

the ownership or possession of real or personal property.

Rights of petitioners secured by the Act of 1866 are vio

lated by Wheaton-Haven’s racially discriminatory member

ship and guest policies. Wheaton-Haven’s racist policies

also violate plaintiffs’ rights under the Civil Rights Act of

1964 (42 U.S.C. 2000a).

This case is indistinguishable in all material aspects from

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, supra, and the court be

low erred in failing to follow that precedent. The court

assumed differences between the two cases where in fact

none exist, and it relied on an invalid factual analysis of

the two cases to support its determination not to be

bound by Sullivan.

ARGUMENT

I. WHEATON-HAVEN’S RACIALLY DISCRIMINA

TORY POLICIES VIOLATE THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OP 1866 (42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982)

A. The remedy provided by the Act of 1886

for racially discriminatory conduct should

be broadly construed

Section 1 of the Act of April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 27, en

titled “An Act to protect all Persons in the United States

11

in their Civil Rights, and furnish the means of their Vin

dication,” provides as follows:

That all persons bom in the United States

and not subject to any foreign power, exclud

ing Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to

be citizens of the United States; and such citi

zens of every race and color without regard to

any previous condition of slavery or involun

tary servitude, except as a punishment for

crime whereof the party shall have been duly

convicted, shall have the same right, in every

State and Territory in the United States to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties,

and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease,

sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty, and to full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of person and

property, as is enjoyed by white citizens and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains and

penalties, and to none other, any law, statute,

ordinance, regulation or custom, to the con

trary notwithstanding.

In codifying this section, it was divided into two parts, 42

U.S.C. §§1981 and 1982, but the language remained es

sentially unchanged with §1981 securing the right to “make

and enforce contracts” and §1982 securing the right to “in

herit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and per

sonal property.”

In Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), the Court

exhaustively reviewed the legislative history of Section 1

of the Act of 1866. The congressional debates and his

torical circumstances attending passage of the law were

12

examined in detail, leading the Court to conclude that,

“In light of the concerns that led Congress to adopt it

and the contents of the debates that preceded its passage,

it is clear that the Act was designed to do just what its

terms suggest: to prohibit all racial discrimination, whether

or not under color of law, with respect to the rights enu

merated therein * * *” 392 U.S. at 436.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was enacted by Congress

pursuant to the Thirteenth Amendment which, as its te x t6"7

reveals, “is not a mere prohibition of State laws establish

ing or upholding slavery, but an absolute declaration that

slavery or involuntary servitude shall not exist in any part

of the United States.” Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 ,20

(1883). Not only did the Thirteenth Amendment, abolish

slavery and establish universal freedom, but it did much

more. As the Court has stated, its enabling clause “clothed

‘Congress with power to pass all laws necessary and proper

for abolishing all badges and incidents o f slavery in the

United States” '1 (emphasis in original). Jones v. Mayer Co.,

supra, 392 U.S. at 439, quoting Civil Rights Cases, supra,

109 U.S. at 20. Under the Thirteenth Amendment, the

Court held, Congress has the power “rationally to deter

mine what are the badges and incidents of slavery and to

The Thirteenth Amendment states:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servi

tude, except punishment for crime whereof the party

shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the

United States, or any place subject to their jurisdic

tion.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce

this article by appropriate legislation.

13

translate that determination into effective legislation.”

Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392 U.S. at 440.

The Congress that passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

as the Court has noted, “had before it an imposing body

of evidence pointing to the mistreatment of Negroes by

private individuals and unofficial groups * * *. The con

gressional debates are replete with references to private

injustices against Negroes — references to white employers

who refused to pay their Negro workers, white planters

who agreed among themselves not to hire freed slaves

without permission of their former masters, white citizens

who assaulted Negroes or who combined to drive them

out of their communities” (footnotes omitted). Id. at 427-

428. The history of the 1866 Act, therefore, reveals con

gressional objectives for the legislation that “belie any at

tempt to read it narrowly.” Id., at 431. Senator Turn-

bull, the author of the Act, declared that it was intended

to affirmatively secure for all men, whatever their race or

color, “great fundamental rights,” including “the right to

acquire property, the right to go and come at pleasure,

the right to enforce rights in the courts, to make contracts,

and to inherit and dispose of property.” Id., at 431-432.

As to those basic civil rights,” the Court has noted, the

Act was intended to “break down all discrimination be

tween black men and white men” (emphasis in original).

Id., at 432.

In Jones v. Mayer Co., the Court held that the Act of

1866 must be accorded “a sweep as broad as its language.”

Id., at 437. Summarizing the broad import of the statute

in language reiterated in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park,

supra, 396 U.S. at 235-236, the Court stated (392 U.S.

at 443):

14

Negro citizens, North and South, who saw

in the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of

freedom — freedom to “go and come at pleas

ure” and to “buy and sell when they please”

— would be left with “a mere paper guaran

tee” if Congress were powerless to assure that

a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase

the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a

white man. At the very least, the freedom

that Congress is empowered to secure under

the Thirteenth Amendment includes the free

dom to buy whatever a white man can buy,

the right to live wherever a white man can

live. If Congress cannot say that being a free

man means at least this much, then the Thir

teenth Amendment made a promise the na

tion cannot keep (footnotes omitted).

The refusal to sell a home to a person because of his

race was held in Jones v. Mayer Co. to be violative of 42

U.S.C. §1982. In Sullivan v. Little Hunting Turk the Court

held that a membership share in a community recreation

association which had been assigned as part of a lease for

the use of the tenant fell within the protection of §1982,

and hence could not be disapproved by the association’s

board of directors merely because the tenant was a Negro.

Significantly, in both cases the Court, specifically rejected

the assertion that, by enacting comprehensive civil rights

legislation in recent years, Congress impliedly repealed the

Act of 1866. Thus, the Fair Housing Title (Title VIII) of

the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (42 U.S.C. §§3601, et seq.)

is quite different in scope of coverage and method of en

forcement from the Act of 1866. Further, Congress was

aware of the earlier law’s provisions at the time it adopted

15

the 1968 statute. Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392 U.S. at

413-417. Likewise, in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park the

Court held that the Act of 1866 is not superseded by the

Public Accommodations provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (42 U.S.C. 2000a). The two laws are “plainly

‘not inconsistent’ ” and the later law in no way impairs

the sanction of the earlier. 396 U.S. at 237-238.8

Since the decision in Jones v. Mayer Co., a considerable

body of case law has developed giving further importance

to the Act of 1866 as a means of securing equality for

Negroes. In Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, the Court re

emphasized the “broad and sweeping nature of the protec

tion meant to be afforded by §1 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1866,” and admonished against a “narrow construction”

of the statutory language. 396 U.S. at 237. Hence, the

1866 Act has been applied by lower courts to prohibit

racially discriminatory practices in employment, housing,

public accommodations and education.

To date, five circuit courts of appeals have recognized

42 U.S.C. §1981 as a basis for relief from private racial

discrimination in employment. In giving effect to the rem

edy, provided by this section, these courts have uniformly

O

This express holding by the Court in Sullivan was disregarded

by the court of appeals in the case at bar. Taking a position di

rectly contrary to this Court’s ruling, the majority below held that

because the 1964 Public Accommodation provisions contain an ex

emption for private dubs, a like exemption is to be read into the

1866 Act. The majority stated, “This exception to the ban on racial

discrimination of necessity operates as an exception to the Act of

1866 in any case where the Act prohibits the same conduct which is

saved as lawful by the terms of the 1964 Act” (Pet. App. B6). This

is one of several examples, as discussed more fully below, of the court

of appeals’ demonstrated lack of regard for precedent set by this Court.

16

rejected the contention that the subsequent enactment of

Title VII (Fair Employment Title) of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.) invalidated the earlier law.

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (C.A. 5, 1970);

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co., 437 F.2d

1011, 1016-1017 (C.A. 5, 1911); Brady v. Bristol-Meyers, Inc.,

decided May 8, 1972, 4 FEP Cases 749 (C.A. 8); Brown

v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(C.A. 4, 1972); Young v. International Telephone & Tele

graph Co., 438 F.2d 757, 758-763 (C.A. 3, 1971); Waters

v. Wisconsin Steel MIorks, 427 F.2d 476, 481-488 (C.A. 7,

1970) , cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911. See also Larson, The

Development o f §1981 as a Remedy for Racial Discrimina

tion in Private Employment, 7 Flarv. Civ. Rights L. Rev.

56 (1972).

§§1981 and 1982 of the 42 U.S.C. have also been ap

plied by courts to remedy racial discrimination in housing

(e.g., Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 290

(C.A. 5, 1970), 444 F.2d 143 (C.A. 5, 1971); Smith v. Sol

D. Adler Realty Co., 436 F.2d 344, 349 (C.A. 7, 1971),

Knight v. Auciello, 453 F.2d 852 (C.A. 1, 1972);McLaurin

v. Brusturis, 320 F. Supp. 190 (E.D. Wis., 1970); Brown v.

Balias, 331 F. Supp. 1033 (N.D. Tex., 1971)); in connec

tion with admission to an outdoor recreational facility

{Scott v. Young, 421 F.2d 143, 145 (C.A. 4, 1970), cert,

denied, 398 U.S. 929); admission to a trade school {Grier

v. Specialized Skills, Inc., 326 F. Supp. 856 (W.D.N.C.,

1971) , and in the purchase of a cemetery plot {Terry v.

Elmwood Cemetery, 307 F. Supp. 369 (N.D. Ala., 1969)).

17

B. Rights secured to petitioners by the Act of

1866 are violated by Wheaton-Haven’s racially

discriminatory membership and guest policies

Wheaton-Haven Recreation Association, Inc. is all but in

distinguishable from Little Hunting Park, Inc., the organiza

tion which was at issue in the Sullivan case. Each is a

voluntary association organized to operate a community

recreation facility, primarily a swimming pool, for residents

of a prescribed neighborhood.9 Here, as in the Sullivan

case, the structure and function of the recreation associ

ation compel the conclusion that reliance on racially dis

criminatory criteria for determining those eligible to use

its facilities is violative of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

As shown supra, p. 7, solely because they are Negroes,

Dr. and Mrs. Press were denied the right, which is avail

able to others living in the neighborhood, to purchase a

Wheaton-Haven membership share and thereby use the as

sociation’s recreational facilities. Since the purchase of such

a share involves making a contract, the denial to the Press’

on the basis of race of the right to enter into such a trans

action violated their right secured by §1981 not to be dis

criminated against in such matters. Likewise, because under

common law principles a membership share in Wheaton-Haven,

9 Such cooperatively established recreation associations formed to

operate neighborhood swimming pools are particularly common in

areas where public swimming pools and beaches are not readily ac

cessible. Petitioners’ brief to this Court in the Sullivan case (p. 24)

noted that in the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C.,

where Little Hunting Park is located there are about 50 community

pool associations; there are about 42 such associations in Montgom

ery County, Maryland, where Wheaton-Haven is located. The Wash

ington Post, p. A-20, June 12, 1967; The (Washington) Evening Star,

p. B-l, Noon edition, April 25, 1969.

18

a non-stock corporation, constitutes personal property,10 the

discriminatory refusal to permit Dr. and Mrs. Press to pur

chase such property on the same basis as white persons

constituted a violation of §1982. Real property interests

subject to the protection of §1982 are also adversely af

fected by Wheaton-Haven’s refusal to allow Dr. and Mrs.

Press access to its facilities. Thus, occupancy of their

home is rendered less valuable and enjoyable when use of

the community swimming pool, which is available to all

white residents of the neighborhood, is denied to them be

cause they are black. Further, since under Wheaton-Haven’s

by-laws the purchaser of a home has the first option to

buy the pool membership of his seller, a home obviously

may be more valuable on the market if it carries with it

an option to purchase such a membership. However, this

increment in property value is denied to Negro home-

owners such as Dr. and Mrs. Press, since they can have no

option to convey. Finally, since membership priority in

Wheaton-Haven is given to persons residing within a three-

quarter mile radius of the pool, homeowners within that

area, of whatever race, who decide to sell to a Negro must

be prepared to accept any loss in value to their property

resulting from the racial restriction on use of the swim

ming pool.

Mr. and Mrs. Murray Tillman have a property interest in

Wheaton-Haven’s pool and recreation facilities as a result

of being shareholders, as well as a contractual relationship

with the association based on the by-laws and rules and

regulations applicable to all members. Under the by-laws

and rules, members generally have a right to bring guests

10 Hyde v. Woods, 4 Otto 523 (1877); Page v. Edmunds, 187 US

596 (1903).

19

to the pool. The association, by adopting the rule limit

ing guest privileges to relatives of members, at least par

tially, in order to impose a racial limitation on the right

to bring guests and thereby prohibit Mr. and Mrs. Tillman

from taking Mrs. Grace Rosner, a Negro, or for that matter

any Negro, to the pool, has created an unlawful racial re

striction on the Tillman’s property interests, as well as on

their contractual relationship with the association. This

racial restriction is plainly impermissible in the face of

§§1981 and 1982. Since, as shown above, the racial re

striction also limits the market for the sale of the Till

man’s home and thereby diminishes its value, the restric

tion is further violative of §1982. Although the Tillmans

are white, since they stand in the role of persons seeking

“to vindicate the rights of minorities” protected by the

statute, they have standing to maintain this action. Sulli

van v. Little Hunting Park, supra, 396 U.S. at 237; Walker

v. Pointer, 304 F. Supp. 56, 58-61 (N.D. Tex., 1969).

Mrs. Grace Rosner, as the Negro guest of the Tillmans,

similarly has rights under §§1981 and 1982, which were

violated by respondents. As the Court held in Walker v.

Pointer, supra, 304 F. Supp. at 60-62, a guest has an im

plied easement of ingress and egress, or a license, which

constitutes property. Hence, to apply the association’s ra

cially restrictive guest policy is to deny prospective Negro

guests the right to acquire and enjoy such an easement, as

well as the opportunity to receive from members a license

or other possessory interest concerning permissible actions

while on association property. See Collver v. Yonkers

Yacht Club, 17 A.D. 2d 973, 234 N.Y.S. 2d 259 (1962).

(social guest of members of club is business invitee); Re

statement (Second) of Torts, §§330, 332 (1965). It should

be further noted that Mrs. Rosner stood in the role of a

20

third person beneficiary to the contract between the Till

mans and Wheaton-Haven, which incorporated a general

policy of permitting members to take guests to the pool.

See generally 17 Am. Jur. 2d Contracts, §§302-319. As a

third person beneficiary, Mrs. Rosner had the right under

§1981 not to be denied performance of the contract be

cause of the imposition of a racial condition.

C. Wheaton-Haven lacks the characteristic of ex

clusiveness associated with a truly private club,

since membership is open to all residents of

the area prescribed by its by-laws.

By sanctioning the exclusion of Negroes from the com

munity recreation facilities operated by Wheaton-Haven,

the court of appeals has squarely contravened this Court’s

decision in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park. Both this case

and Sullivan involve voluntary associations organized by

residents of neighborhood to provide opportunities for rec

reation for themselves and others in the area, principally

by the construction and operation of a swimming pool.

In each instance membership in the association, and hence,

use of its facilities, is available to everyone residing in the

area defined by its by-laws. In neither case did the associ

ation pursue a policy of exclusiveness until a black resident

of the neighborhood sought the privileges of membership

for himself and his family. In Sullivan, as here, the court

below held that the association could properly exclude the

black applicant on the ground that the association was a

“private club.” In Sullivan, however, this Court declared

that it found “nothing of the kind on this record.” 396

U.S. at 236. The Court continued (ibid.):

There was no plan or purpose of exclusive

ness. It is open to every white person within

21

the geographic area, there being no selective

element other than race.

Wheaton-Haven similarly has “no plan or purpose of

exclusiveness.” Its by-laws specify that membership “shall

be open to bona fide residents (whether or not home-

owners) of the area within a three-quarter mile radius of

the pool.” Unlike the conventional social club, fraternal

lodge, or similar organization, personal compatibility with

other members is not a qualification for membership in

Wheaton-Haven. In conventional social or fraternal organ

izations — those having as their principal purpose the fos

tering of fellowship and camaraderie - friendship, tradi

tion and common social, educational or occupational back

grounds play a major role in determining membership eligi

bility. For Wheaton-Haven, however, the sole determinant

of membership is residence within the prescribed area. No

further qualification, recommendation, or nomination is re

quired. It is inconsistent with the nature of a truly pri

vate club for an organization, in determining membership

eligibility, to rely solely on geography, to the exclusion

of all other factors — except race. Nesmith v. Y.M.C.A.

o f Raleigh, N.C., 397 F.2d 96, 102 (C.A. 4, 1968); and

see United States v. Richberg, 398 F.2d 523 (C.A. 5,

1968); Rockefeller Center Luncheon Club, Inc. v. John

son, 131 F. Supp. 703, 705 (S.D. N.Y., 1955). Wheaton-

Haven is functionally similar to the recreational facility in

Daniel v. Paul, 395 U.S. 298 (1969). The Court there

held that an establishment which is “open in general” to

“all members of the white race” may not masquerade as

a private club merely in order to exclude Negroes from

its facilities. 395 U.S. at 302.

Nor is the missing element of selectivity supplied by the

fact that under Wheaton-Haven’s by-laws, in addition to

22

the residence requirement, membership applications are

subject to approval by a majority vote at a meeting of

the membership or of the Board of Directors. There is

no evidence that any factor other than area of residence

or race has ever been considered as a basis for such votes.

Indeed, it is clear that membership approvals are given as

a routine matter, as shown by the fact that in Wheaton-

Haven’s 11-year history prior to the events herein, only

one person had ever been rejected for membership. The

record does not disclose either the race of that applicant

or place of residence at the time of the rejection (Pet. App.

B21; A. 88, 93).11

Any claim of exclusivity by Wheaton-Haven has a par

ticularly hollow ring, in view of its by-laws provision which

gives a member who sells his home the right to make his

membership share available for purchase by his vendee, not

withstanding the fact that there may be a waiting list con

sisting of persons who have been seeking memberships for

a substantial period of time.12 The accident of who one

buys his home from, therefore, determines membership eli

gibility in those circumstances. This by-laws provision

1 The court of appeals erroneously relied on the unsubstan

tiated claim of defendants’ counsel at oral argument that “numer

ous” other unidentified white persons were informally rejected for

membership by being denied an application form (Pet. App. B21,

n. 23). This claim is contradicted by defendants’ sworn answer to

plaintiffs’ interrogatory No. 17, which reflects only one rejection

for membership, formal or informal, and gives no indication that

there were others whose identity was unknown (A. 88, 93).

12

Thus, Article VI of the by-laws provides that when the mem

bership rolls are full, the association is required to purchase the share

of the vendor who wishes to transfer his share to his vendee. Upon

receipt of the vendor’s resignation, the association must give the

vendee first option to purchase the share (A. 47).

23

further demonstrates that the organizers of Wheaton-Haven

were well aware of the important asset that the swimming

pool would be to their neighborhood, and that they would

increase the attractiveness and value of their homes by be

ing able to assure a potential purchaser not only of the

availability of a pool membership, but that if there was a

waiting list, the buyer would have the unqualified right to

purchase the seller’s pool membership.

In view of the membership priority thus given to per

sons purchasing homes from Wheaton-Haven members, and

the priority given generally to persons residing within a

three-quarter mile radius of the pool, it is apparent that

use of Wheaton-Haven’s facilities is in fact an incident of

“residence” in the neighborhood served by the pool. Hence,

the association’s racially discriminatory admission policies

cannot be disassociated from other factors generally re

sponsible for residential segregation by race which, unfor

tunately, is still all too prevalent in this country. The

enactment of numerous fair housing laws, federal, state

and local, in recent years reflects the national commitment

to combat this problem. However, it is clear that the rou

tine exclusion of Negroes from neighborhood recreation

facilities would both discourage them from buying in that

neighborhood, and make any purchase they did make a

poorer bargain than that a white citizen can make. “Solely

because of their race, non-Caucasians will be unable to pur

chase, own, and enjoy property on the same terms as Cau

casians.” Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 254 (1953).

As the Court stated in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, su

pra, 396 U.S. at 236, “What we have here is a device func

tionally comparable to a racially restrictive covenant, the

judicial enforcement of which was struck down in Shelley

r. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 [1948] * * *”

24

D. There are no valid grounds for distinguishing

this case from Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park

Faced with the compelling precedent of Sullivan v. Lit

tle Hunting Park, and the unassailable conclusion of Judges

Butzner, Winter and Craven, in dissent, that this case is

“indistinguishable” from Sullivan, the majority of the court

below nevertheless assumed differences between the two

cases where in fact none exist, and constructed a false

factual analysis of the two cases to support its determina

tion not to be bound by Sullivan.13

1. The court of appeals made the clearly erroneous

assumption that Little Hunting Park’s recreation facilities,

which were involved in Sullivan, were built by the same

real estate developers who built the subdivisions named

in that organization’s by-laws, and that therefore the right

to use those facilities is incidental to the acquisition of a

lot in one of those subdivisions (Pet. App. B9, n. 8,B16).

This assumption is belied by the record of the Sullivan

proceeding in this Court, which was before the court of

appeals.14 The court of appeals’ attention was called to

1 ̂ The court of appeals did not rely on the district court’s rea

sons for determining that Wheaton-Haven is a private club, but in

stead stated its own grounds to support its conclusion.

14 The printed appendix to the briefs used in this Court in the

Sullivan case was submitted to the court of appeals at oral argu

ment by petitioners’ counsel, and was relied upon by the court in

writing its opinion. In addition, excerpts from the Sullivan appen

dix, have been designated by petitioners for inclusion in the appen

dix to the briefs in the instant case (A. 64-84). Petitioners respect

fully request this Court to take judicial notice of those portions of

the Sullivan record. United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 216 (1942);

National Fire Insurance Co. v. Thompson, 281 U.S. 331, 336(1930)

25

the fact that there was no connection between Little Hunt

ing Park and any commercial builder, and that the associ

ation there, like Wheaton-Haven, is a voluntary organiza

tion formed by residents of an area who joined together

to build and operate a .neighborhood recreation facility

(A. 65-76, 77-78).

2. The court of appeals made the clearly erroneous

assumption that in order to be eligible for membership in

Little Hunting Park one is required to own property within

a prescribed geographic area (Supp. App. B15). The rec

ord of the Sullivan case shows that out of an authorized

membership of 600, 133 members resided in areas outside

of the prescribed area at the time they acquired member

ship, and there is no evidence that at the time of acquir

ing membership any of them owned property in that area

(A. 84). A similar situation exists with respect to Wheaton-

Haven which allows persons residing outside the three-quar

ter mile eligibility area to join upon the recommendation

of a member as long as such persons do not exceed 30

percent of the total membership {supra, pp. 4-5).15

3. The court of appeals made the clearly erroneous

assumption that Wheaton-Haven has a greater degree of

“exclusivity” than Little Hunting Park, which distinguishes

5 Contrary to the court of appeals’ supposition (Supp. App.

B15, n. 17), the Little Hunting Park eligibility area was extended

several times to include areas in addition to the four subdivisions

specified in the by-laws (A. 82-84). Further, there is no basis for

the court’s the “leap to suppose” (Supp. App. B15, n. 17) that

such additional areas were opened by the same developers who had

opened the original four. As shown above, the subdivisions sur

rounding Little Hunting Park were built long before the recreation

association was organized, and builders had nothing to do with its

formation.

26

this case from Sullivan and gives Wheaton-Haven license

to discriminate against Negroes. The court relies on the

fact that in Wheaton-Haven’s 11-year history one applicant

for membership was rejected (Supp. App. B20-B21). The

court, however, completely ignores the fact from the Sul

livan record, which was brought to its attention, that in

the 12 years of Little Hunting Park’s existence one ap

plicant for membership was also rejected (A. 79).16

4. The court of appeals made the clearly erroneous

finding that the option to buy a membership in Wheaton-

Haven which the purchaser of a home obtains when his

vendor resigns his membership is “utterly without use or

value” (Supp. App. B13). The court arrived at this find

ing by erroneously relying on the unsubstantiated claim of

defendant’s counsel at oral argument that Wheaton-Haven’s

membership had been 260 families for several years, less

than its maximum limit of 325 (Supp. App. B2, n. 1).

The Court reasoned that the option has no value unless

the membership rolls are full. When it was pointed out

in the petition for rehearing that the membership rolls

were full to the 325 maximum in the spring of 1968 when

Dr. Press sought membership, and that he would have been

placed on the waiting list, if he had not been discriminated

against, the court corrected its findings to reflect full mem

bership at that time (Supp. App. B30; A. 88, 92, 105-106).

However, the court did not alter its conclusion that the

option is of no use or value.

16 The court of appeals, in Part III of its opinion, cited various

features of Wheaton-Haven as “indicators of its private nature” (B18).

Every one of the factors referred to, however, is also characteristic of

Little Hunting Park, which was held by this Court not to be a pri

vate club.

27

The court’s adherence to its conclusion, despite the dem

onstrated error of its underlying factual finding illustrates

the erroneous approach taken by the court to this case.

Its opinion is based on previously arrived at determina

tions, and facts were fashioned to provide their justifica

tion. In actuality, the question of whether Wheaton-Haven’s

membership rolls are full, or not full, at any given time

has nothing to do with whether the purchase of a mem

bership share involves contractual and property rights fall

ing under the protection of 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982. How

ever, by seizing on this and other irrelevant factors in ana

lyzing this case and Sullivan, the court relied upon wholly

invalid grounds for distinguishing the two cases.

II. WHEATON-HAVEN’S RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

POLICIES VIOLATE THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF

1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000a)

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. Sec.

2000a) prohibits racial discrimination in “any place of

public accommodation,” which is defined to include any

“place of entertainment” if its “operations affect com

merce” . In Daniel v. Paul, supra, 395 U.S. 298, the Court

held that a recreational establishment in which persons are

not passive spectators, but are direct participants, is a “place

of entertainment” within the meaning of the statute. The

Court also held in Daniel that recreational equipment and

apparatus originating out of the state constituted “sources

of entertainment which move in commerce” for the pur

poses of subsection (c)(3) of the statute. In reaching the

latter conclusion, the Court adopted the view previously

taken by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit that

the phrase “move in commerce” in subsection (c)(3) in

cludes sources of entertainment, such as equipment and

28

supplies, which had moved in interstate commerce but

which have come to rest at the place of entertainment. See

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394 F.2d, 342, 351-352

(C.A. 5, 1968). Accord: Scott v. Young, supra, 421 F.2d at

144 (C.A. 4). United States v. Central Carolina Bank & Trust

Co., 431 F.2d 972 (C.A. 4, 1970).

In the instant case, as shown supra, p. 5, the Wheaton-

Haven pool was constructed by a contractor from outside

the State of Maryland and the operations of the pool in

volve the use of machinery and equipment manufactured

in other states. Hence, there can be no question under

the relevant authorities that the necessary link to inter

state commerce is present. Daniel v. Paul, supra; Scott v.

Young, supra11

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 has a specific provision

exempting from coverage “a private club or other estab

lishment not in fact open to the public.” Consistent with

its holding that Wheaton-Haven is not subject to the Act

of 1866 because of its status as a private club, the court

below held that the Act of 1964 similarly is inapplicable

because of the private club exemption. This Court’s hold

ing in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, and the discussion

supra, pp. 20-27, amply demonstrate, we believe, that

Wheaton-Haven lacks the degree of exclusiveness sufficient

to exempt it from coverage of the 1964 Act. Nor can it 17

17 The performance of services by a contractor from another

state suffices to bring a facility within the scope of interstate commerce.

International Brotherhood o f Electrical Workers v. National Labor Re

lations Board, 341 U.S. 694, 699 (1951); National Labor Relations

Board v. National Survey Service, 361 F.2d 199, 203-204 (C.A. 7,

1966), and cases cited; National Labor Relations Board v. Local 1423,

United Brotherhood o f Carpenters, 238 F.2d 832, 835 (C.A. 5,1956);

National Labor Relations Board v. The Austin Co., 165 F.2d 592,

594 (C.A. 7, 1947).

29

be maintained that Wheaton-Haven is “not in fact open to

the public.” For the record shows that it is open to every

one residing within the three-quarter mile radius which it

serves. The numerical limit on memberships to 325 fami

lies does not compel a contrary conclusion, for that is

merely a means of preventing overcrowding of the facili

ties. The observance of such a limitation in the interest

of health and safety is no more indicative of private club

status for Wheaton-Haven than it is for a theatre or restau

rant which similarly limits its number of patrons. Nor is

it significant that Wheaton-Haven requires payment of an

annual fee, rather than individual admission charges, for the

use of its facilities. The fact is that the Wheaton-Haven

pool is “open to any white individual” or family residing

within the prescribed area “who can afford the yearly mem

bership rates.” Nesmith v. Y.M.C.A. o f Raleigh, N.C., su

pra, 397 F.2d at 101 (C.A. 4).

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be re

versed, and the case should be remanded to that court

with directions to remand to the district court for further

appropriate proceedings.18

1 Q

Since the district court took no evidence on the question of

damages, this issue, as well as the liability for damages of individual

directors of Wheaton-Haven, requires a further hearing. It is clear

that an award of monetary damages is an appropriate remedy for vio

lations of 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982. Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park,

supra, 396 U.S. at 238-240; Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., su

pra, 429 F.2d at 293-295 (C.A. 5); Smith v. Sol D. Adler Realty

Co., supra, 436 F.2d at 350-351 (C.A. 7); Knight v. Auciello, supra,

(continued)

30

Respectfully submitted,

ALLISON W. BROWN, JR.

Suite 501, 1424 - 16th St.,N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

RAYMOND W. RUSSELL

22 West Jefferson Street

Rockville, Maryland 20850

SAMUEL A. CHAITOV1TZ

30 W. 60th Street

New York, N.Y. 10023

Of Counsel: Attorneys for Petitioners

MELVIN L. WULF

American Civil Liberties Union

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10010

June 1972.

^ (continued) 453 F.2d 852 (C.A. 1); Brown v. Balias, supra,

331 F. Supp. at 1037 (N.D. Tex.); Williamson v. Hampton Manage

ment Co., 339 F. Supp. 1146, 1149 (N.D. 111., 1972). Moreover,

on the basis of the complaint’s allegations, the directors who par

ticipated in the discrimination against petitioners are liable for

damages, along with the corporation, based on their roles in the

wrongful conduct. See National Cash Register Co. v. Leland, 94

Fed. 502, 508-511 (C.A. 1, 1899), cert, denied, 175 U.S. 724;

Trounstine v. Bauer, Pogue & Co., 144 F.2d 379, 382 (C.A. 2,

1944), cert, denied, 323 U.S. I l l ; Hitchcock v. American Plate

Glass Co., 259 Fed. 948, 952-953 (C.A. 3, 1919); Lobato v. Pay

Less Drug Stores, Inc., 261 F.2d 406, 408-409 (C.A. 10, 1958);

American Universal Insurance Co. v. Scherfe Insurance Agency, 135

F. Supp. 407, 415416 (S.D. Iowa, 1954).

(continued)

31

1 Q

(continued)

One director, Richard E. McIntyre, who has been separately rep

resented in this litigation, argues that the case should be dismissed

as to him because he did not agree with the board of directors’

racial policies and because he did not participate in the discrimina

tion. This, of course, is a matter for determination upon the taking

of evidence in the trial court. In any event, McIntyre’s deposition

shows that he knew of Dr. and Mrs. Press’ desire to become mem

bers, that he told them they were unacceptable to the board be

cause of their race, and that he never made any formal move at a

board meeting to admit them to membership (A. 104-105). In ad

dition, at one board meeting in the summer of 1968, when Wheaton-

Haven’s guest policy was under discussion, McIntyre admittedly,

made a motion “to bar all Negro guests” (A. 116). McIntyre was

at the board meeting on July 20, 1968, when the vote was taken

to adopt the racially discriminatory guest policy. He claims he did

not vote, but the official minutes of the meeting record him as

being present and state that the vote for the guest policy was unan

imous (A. 41-42).