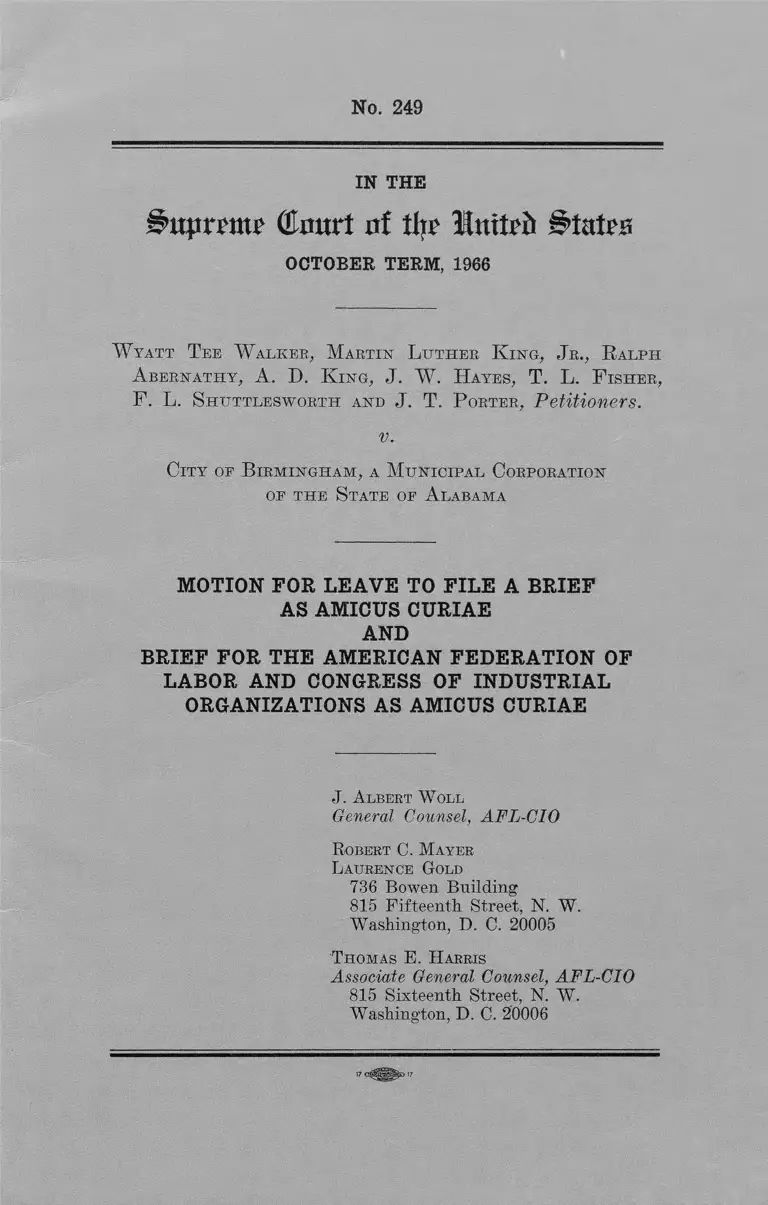

Walker v. City of Birmingham Motion for leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Motion for leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. 3861ad47-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69ac9e3a-3a7e-46aa-a760-b83db3ce1db0/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 249

IN THE

Supreme Court of tiro luttrft ^totro

OCTOBER TERM, 1966

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r., R alph

A bern ath y , A . D . K ing , J. W . H ayes, T. L . F ish er ,

F . L . S h u ttlesw orth and J. T. P orter, Petitioners.

v.

C ity of B ir m in g h a m , a M u n icipal C orporation

of th e S tate of A labama

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF

AS AMICUS CURIAE

AND

BRIEF FOR THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

LABOR AND CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL

ORGANIZATIONS AS AMICUS CURIAE

J. Albert W oll

General Counsel, AFL-CIO

Robert C. Mayer

Laurence Gold

736 Bowen Building

815 Fifteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

Thomas E. H arris

Associate General Counsel, AFL-CIO

815 Sixteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

17 17

INDEX

Page

Motion for Leave to P i le ............................................................. iii

Brief .............................................................................................. 1

Interest of the APL-CIO ............................................................. 1

Reasons for Granting the Petition ............... 3

1. The decision may encourage abuse of the labor injunction 3

2. The decision permits the use of unconstitutional licensing

ordinances to bar unions ......................... 12

3. The decision exalts a state procedural rule over basic sub

stantive federal rights ....................................... 15

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 20

CITATIONS

Cases :

Alabama Cartage Co., Inc. v. Teamsters, 34 So.2d 576, 21

LRRM 2682 ................................................................................ 10

Amalgamated Clothing Workers v. Bichman Bros., 348 TJ.S.

511 .............................................................................................. 7

Chavez v. Sargent, 52 Col.2d 162, 339 P.2d 8 0 1 ................... 13

Construction & General Laborers’ Union, Local 438 v. Curry,

371 TJ.S. 542 ........................................... ......................... 4, 6, 7,18

Denton v. City of Carrollton, 235 F.2d 4 8 1 ............................... 15

Dombrowshi v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 .......................................... 15

Douglas v. City of Jeanette, 319 U.S. 1 5 7 ................................... 15

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248 ................................. 19

Green, In re, 369 U.S. 689 ................................................... 3,16,19

Greenwood, City of v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 ........................... 6,14

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 ........................................... 19

i

Page

Hattiesburg Building & Trades Council v. Broome, 377 U.S.

126 ........................................................................................... 6,9

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443 ............................................. 17

Hotel Employees Union, Local No. 255 v. Sax Enterprises,

Inc., 358 U.S. 270 ....................................................................... 9

IBEW Local Union 429 v. Farnsworth <& Chambers Co., 353

U.S. 969 ................................................................................ 8

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 ............................................... 19

Kentucky State AFL-CIO v. Puckett, 391 S.W.2d 360, 59

LRRM 2337 ................................................................................ 13

Liner v. Jafco, Inc., 375 U.S. 3 0 1 ............................................. 8,18

Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 ......................................... 13

Porterfield, In re, 28 C'al.2d 91, 168 P.2d 706 ............................ 13

Radio & Television Broadcast Technicians, Local 1264 v.

Broadcast Service of Mobile, 380 U.S. 255 ........................... 6,10

Shuttlesworth v. City of Mobile, 376 U.S. 339 .......................... 18

Starnes v. City of Milledgeville, 56 P. Supp. 956 ................. 15

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 3 1 3 .................... 9,12,14,16,18

Steelworkers v. Bagwell, 239 F. Supp. 626 .............................. 15

Steelworkers v. Fuqua, 253 F.2d 594 ......................................... 15

Teamsters Union, Local No. 327 v. Kerrigan Iron Works, 353

U.S. 968 ...................................................................................... 1>8

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258 ............ 18,19

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 ............................................... 11

Toungdahl v. Rainfair, Inc., 355 U.S. 1 3 1 ................................. 5

Miscellaneous :

BUSINESS WEEK for April 25, 1954 ..................................... 2

THE USE OP STATE COURT INJUCTIONS IN LABOR-MAN

AGEMENT DISPUTES (Senate Document No. 7, 81st Cong.,

2d Sess.) ...................................................................... 4 ,5 ,7 ,9,10

u

IN THE

Supreme (£mtrt nf % Imteii BUUb

OCTOBER TERM, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r., R alph

A bern ath y , A . D . K in g , J. W , H ayes, T . L . F ish er ,

F . L. S h u ttlesw orth and J. T . P orter, Petitioners.

v.

C ity of B ir m in g h am , a M u n icipa l C orporation

of th e S tate of A labama

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF

AS AMICUS CURIAE

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of In

dustrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) hereby respectfully

moves for leave to file a brief as amicus curiae in support

of petitioners ’ petition for a rehearing. The consent of the

attorneys for the petitioners has been obtained. The con

sent of the attorneys for the respondent was requested but

refused.

The AFL-CIO has never before asked leave of this

Court to file an amicus brief urging grant of a petition for

rehearing. We do so now because we are concerned that

the decision of the Court in this ease may furnish local

officials and judges with a means of destroying rights of

free speech and assembly generally, and the right of work

ers to organize in particular. Further, it has been the ex

perience of the AFL-CIO over many years that in some

areas local officials, including, unfortunately, judges, will

seize upon any legal device available to frustrate union

organization.

iii

Counsel for the petitioners have dealt and will deal with

the general impact of the decision on free speech and as

sembly. The memorandum for the United States as Amicus

Curiae likewise covered, admirably we think, that aspect of

the case. While the AFL-CIO is, naturally, deeply con

cerned with those issues, we shall, to avoid duplication,

treat principally the area of our particular concern and

experience.

Hence we ask leave to place before the Court a state

ment of our reasons for believing, on the basis of the ex

perience of AFL-CIO unions, that its decision in this case

may he widely used to destroy the right of workers to or

ganize; that it may facilitate the undercutting by hostile

local officials both of basic constitutional rights and of na

tional labor policies embodied in federal legislation; and

that the decision should, therefore, be reconsidered. A brief

containing such a presentation is tendered with this motion.

Respectfully submitted,

J. A lbert Worn

General Counsel, AFL-CIO

Robert C. Mayer

Laurence Gold

736 Bowen Building'

■ 815 Fifteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

Thomas E. H arris

Associate General Counsel, AFL-CIO

815 Sixteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

July 1967

IV

Bnpmn? (Hmtrt nt tlw ImtBib States

OCTOBER TERM, 1966

IN THE

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bernath y , A . D. K ing , J . W . H ayes, T. L . F isher ,

F. L. S h u ttlesw orth and J . T. P orter, Petitioners.

v.

C it y op B ir m in g h am , a M u n icipa l Corporation

op th e S tate op A labama

BRIEF FOR THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

LABOR AND CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL

ORGANIZATIONS AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AFL-CIO

This brief amicus curiae is tendered for filing by the

American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial

Organizations (AFL-CIO), contingent upon the Court’s

granting the Motion for Leave to File a Brief Amicus

Curiae.

The AFL-CIO is primarily an association of one hun

dred twenty-nine national and international unions. These

unions are active in organizing and representing employ

ees in collective bargaining throughout the United States,

including the southeastern part of the United States. The

AFL-CIO itself is likewise active in organizing throughout

the United States, and for that purpose maintains a De

partment of Organization comprised of a director, two as

sistant directors, 20 regional directors, 10 assistant regional

directors, and a staff of 124 field representatives. The

AFL-CIO and its affiliated unions thus have had extensive

experience with the obstacles, legal and otherwise, to or

ganizing in the southeastern part of the United States.

(2)

Those obstacles are substantial. A compilation appear

ing in Business Week for April 25, 1964, p. 49, shows that

whereas the percentage of eligible workers in unions is

31% for the country as a whole, the figure for North Caro

lina is 7.4%, for South Carolina 7.8%, for Virginia 11.6%,

for Florida 12.7%, for Georgia 13.4%, and for Mississippi

13.7%. Only Alabama among the southeastern states shows

a figure approaching that for the Nation as a whole, i.e.:

30.2%, and that is because the large steel companies which

have substantial employment in Alabama and whose em

ployees are organized in other parts of the country have

not relentlessly fought unionization as have most employ

ers in the southeast.

In opposing unions employers in the southeast receive

in most instances the full and enthusiastic cooperation of

the local authorities, including the city councils, the courts,

and the police, local or state. Industrial plants are often

enticed to locate in particular communities by being given

free plants or plant sites which are financed by tax exempt

local bond issues, and the local officials and community

leaders undertake, as part of the enticement and to protect

their investment, to bar unions.

As part of this pattern two devices, among others, are

extensively used to deny the right to form unions purport

edly conferred by the National Labor Relations Act and,

for that matter, the rights of free speech and assembly

guaranteed by the Fourteenth and First Amendments.

One device is the issuance of a temporary restraining

order or preliminary injunction in virtually every labor-

dispute, often in complete disregard both of substantive

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment and the National

Labor Relations Act and of the exclusive primary juris

diction of the National Labor Relations Board. The other

device is the enactment of blatantly unconstitutional local

licensing ordinances.

(3)

We believe, and we seek to show, that the decision of

this Conrt in this case may invite the continued use of

these illegal injunctions and ordinances by further weak

ening the already inadequate remedies against them. We

further submit, with all deference, that the decision of the

Court will not promote “ respect for judicial process” or

“ the civilizing hand of law” but will, rather, promote dis

respect for the courts and the law by encouraging the con

tinued abuse of judicial process to deny basic rights.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

1. The decision may encourage abuse of the labor injunc

tion by state courts. While the opinion of the Court in the

present case is not entirely clear, it may be read as requir

ing compliance with an injunction, even if the issuing court

had no jurisdiction because of federal preemption. See

especially the discussion in footnote 6 of In re Green, 369

U.8. 689. The decision clearly requires compliance with

an injunction even though it is invalid under the Four

teenth Amendment as impermissibly restraining free speech

and assembly; and as the dissenting justices point out it is

difficult to believe that the Court meant to accord greater

sanctity to the exclusive primary jurisdiction of the Na

tional Labor Relations Board than to the substantive rights

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. Hence we are

concerned that the decision may require unconditional

obedience to any and every state court injunction. Any

such doctrines would be utterly destructive of any right

to form unions in the southeastern part of the United

States.

The experience of the AFL-CIO and its affiliated unions

and available published materials show that the use of

labor injunctions has steadily increased in the state courts

in the southeastern States, even before the present decision.

(4)

Indeed the use of injunctions in labor disputes seems to

have spread as industrialization has spread.

A monumental study, “ THE USE OF STATE COURT

INJUNCTIONS IN LABOR - MANAGEMENT DIS

PU TES” (Senate Document No. 7, 81st Cong., 2d Sess.),

was published by the Senate Committee on Labor and Pub

lic Welfare in 1951.1 This study found that the use of in

junctions had approximately doubled in the southeastern

States2 during the post-World War II period, as compared

with 1932-45. (Report, p. 96.) Yet at that time injunctions

were still rare in the Carolinas (Report, p. 96), whereas

they are, according to the advices received by the AFL-CIO,

now standard operating procedure there. And the picture

does not seem to be appreciably different in other States in

the area: the petition for certiorari in Construction $ Gen

eral Laborers’ Union, Local 438 v. Curry, 371 U.S. 542,

filed in 1962, listed (pp. 14-20) 46 cases in which prelim

inary injunctions had issued since 1952 in Fulton County

(i.e., Atlanta), Georgia, alone.

In some areas, including, as we are advised, North and

South Carolina, it is the usual practice for the judges to

issue ex parte temporary restraining orders,3 while in

1 The Committee commissioned four universities to study the use

of state court injunctions in labor disputes in four areas of the

country. One of these areas was the southeastern States, the study

there being made by Duke University. In all four areas the surveys

were conducted under the supervision of distinguished scholars, viz.,

Edwin E. Witte, University of Wisconsin; Benjamin Aaron,

U.C.L.A., Milton R. Konvitz, Cornell; and Charles H. Livengood,

Jr., Duke. No comparable study has been made since.

2 For purposes of the study the southeast was defined (p. 92) as

including the 10 States of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia,

Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee

and Virginia. We use the same definition.

3 The 1951 Senate Committee study states (p. 6) :

“ In the Southeastern States ex parte restraining orders were

issued in 81 of the 96 cases * * * for which information on this

point was obtainable.

(5)

others some notice is given, and in still others the usual

practice is to issue a temporary injunction after a prelim

inary hearing. In any event, anything more than a pre

liminary hearing is extremely rare, because the dispute is

usually settled long before any hearing on the merits can

be obtained. Of the 46 injunction cases listed in the peti

tion for certiorari in Curry not a single case ever went to

hearing on the merits. As the petition explained, pp. 17-18,

in Fulton County, Georgia, a case does not come up for

trial on the merits in less than one year, and by that time

the controversy is invariably entirely moot. The 1951 Sen

ate Labor Committee study similarly found that few labor

injunctions ever are carried beyond the temporary injunc

tion staged

The restraining order or temporary injunction is often

based on generalized allegations of violence or threats of

violence, and that was the practice 25 years ago, too. (See

Senate Report, p. 97.) The injunction is usually in broad

terms, with no attention being paid to this Court’s holding

in Youngdahl v. Rainfair, Inc., 355 TJ.S. 131, that only vio

lence, and not peaceful picketing, may constitutionally be

enjoined. Thus in 41 of the 46 cases listed in the petition in 4

4 The study states (p. 7) :

“ The lack of full hearings in labor injunction eases, in which

witnesses testify in open court and are subject to cross examina

tion, is not due to any ‘ abuse’ of the injunction procedure by the

courts. It arises from the nature of labor-management disputes.

These usually last but a short time and all pending legal pro

ceedings are dismissed when a strike settlement is reached. * * *

Injunctions in labor cases are almost always issued either ex

parte or after only oral arguments in court, with the testimony

confined to the complaint and answer and the supporting affidavits

filed by the two sides. The pleadings and affidavits presented by

the parties are often contradictory, yet the courts generally dis

pose of the litigation of this sort of evidence, without examina

tion of the witnesses in person, unless the case reaches the per

manent injunction stage (which, as noted, is rare).”

(6)

Cxirry, the temporary injunction restrained all picketing

or striking. And the courts often pay little heed to any

claim that the dispute is within the exclusive primary jur

isdiction of the National Labor Eolations Board. See, e.g.,

Construction & General Laborers’ Union, Local 438 v.

Curry, 371 U.S. 542; Hattiesburg Building & Trades Coun

cil v. Broom, 377 U.S. 126 (per curiam); Radio &Television

Broadcast Technicians Local Union 1264 v. Broadcast Serv

ice of Mobile 380 U.S. 255 (per curiam).

The injunction usually narrowly limits the number of

pickets, and it customarily prohibits picketing on the em

ployer’s premises, such as the road into the plant, the park

ing lots, and so forth. Thus the pickets are moved out to

the public highway, where the local police or sheriff’s

deputies harass them for blocking traffic.

Once the strike or organizing campaign is broken, or,

much more rarely, the dispute is settled between the union

and the employer, the legal proceedings languish.

That is the way the labor injunction works in the south

eastern States at the present time.

The remedies now available against even flagrantly il

legal state court labor injunctions are wholly inadequate.

Removal to federal court would be an adequate remedy

but these cases do not fall within the general removal stat

ute (28 U.S.C. §1441) or, under the decisions, of this Court,

within the special removal statute applicable to civil rights

cases, i.e., 28 U.S.C. §1443. See, e.g., City of Greenwood,

Mississippi, 384 U.S. 808. While this Court has not ruled

on whether state court suits for breach of contract under

§301 of the Taft-Hartley Act are removable to federal

court, a decision in favor of removal would not alleviate the

situation with which we are here concerned; for state court

injunctions are used in the southeast to bar unionization,

not to enforce collective bargaining agreements.

(7)

A federal court injunction against state court proceed

ings where the matter is within exclusive primary NLRB

jurisdiction would likewise be an adequate remedy, but is

likewise unavailable under the Court’s decision in Amal

gamated Clothing Workers v. Richman Bros., 348 U.S. 511.

The course seemingly required by the Court’s decision

in the present case, of complying with the temporary re

straining order or preliminary injunction while appealing,

is doubly inadequate.

In the first place, as already shown, the strike or organ

izing campaign will normally be defeated long before ap

pellate review is obtained. This Court so recognized in

Construction & General Laborers’ Union, Local 438 v.

Gurry, 371 U.S. 542, where it held that a preliminary in

junction directed by the Georgia Supreme Court in a labor

dispute properly within exclusive NLRB jurisdiction had

sufficient finality to be reviewable by this Court. This Court

declared (371 U.S. at 550):

“ The truth is that authorizing the issuance of a tem

porary injunction, as is frequently true of temporary

injunctions in labor disputes, may effectively dispose

of petitioner’s rights and render entirely illusory his

right to review here as well as his right to a hearing

before the Labor Board.”

In Tennessee, according to the 1951 Senate Committee

study, p. 94:

“ An appeal cannot be made from a temporary re

straining order and a defendant cannot move to dis

solve except on hearing. Motions to dissolve are placed

on the regular court docket and wait their turn to be

heard. ’ ’

The remedy of appeal through the state courts is thus

even more clearly futile in Tennessee than elsewhere.

In Teamsters Union, Local No. 327 v. Kerrigan Iron Works,

(8)

353 U.S. 968, a temporary injunction against picketing was

issued, and a motion to dismiss because of exclusive NLRB

jurisdiction was denied, by the Chancellor, on January 12,

1953. Tbe case was beard on the merits by the same Chan

cellor on June 28, 1955, and the injunction was made per

manent on that date. The Tennessee Court of Appeals af

firmed on June 29, 1956 (41 Tenn. 467, 296 S.W. 2d 379, 38

LRRM 2499), and this Court granted certiorari and re

versed per curiam on May 27, 1957.

Plainly, in cases like these, appellate review, whether in

the state courts or by this Court, is only of precedential

value, and is meaningless as respects affecting the outcome

of the particular controversy. Indeed in Liner v. Jafco,

Inc., 375 U.S. 301, the Tennessee Court of Appeals affirmed

an injunction against peaceful picketing in part on the

ground that the case was moot because the construction

project had been completed. This Court reversed, holding

that the dispute was within NLRB jurisdiction and that

the Court was not bound by the state court’s finding of

mootness. The Court said (375 U.S. at 307):

“ It would encourage such interference with the federal

agency’s exclusive jurisdiction if a state court’s hold

ing of mootness based on the chance event of comple

tion of construction barred this Court’s review of the

state court’s adverse decision on the claim of federal

preemption. ’ ’

See also IBEW Local Union 429 v. Farnsworth & Cham

bers Co., 353 U.S. 969, reversing per curiam the Supreme

Court of Tennessee.

In the second place, the appellate remedy is illusory be

cause there is no ground for believing that state appellate

courts in the southeast have any greater concern than do

state trial courts for constitutional rights of free speech

and assembly, or for the exclusive jurisdiction of the

NLRB. To be blunt, it is a case of out of the frying pan

into the fire.

In Curry the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia,

which, as the petition for certiorari recited, had issued

preliminary injunctions totally prohibiting picketing or

striking in 41 cases in the preceding 10 years, for once

refused to issue an injunction in deference to NLRB juris

diction; but the Georgia Supreme Court reversed and or

dered an injunction. The Georgia appellate courts like

wise flagrantly refused to protect the basic constitutional

rights of workers and unions in Staub v. City of Baxley,

355 U.S. 313.

The situation is not different in other southeastern States.

In Florida, the state trial courts repeatedly refused to en

join peaceful organizational picketing of resort hotels, and

the Florida Supreme Court repeatedly ordered that the

injunctions issue. Finally this Court reversed per curiam,

holding that the state courts were without jurisdiction.

Hotel Employees Union, Local No. 255 v. Sax Enterprises,

Inc., 358 U.S. 270. See also Hattiesburg Building & Trades

Council v. Broome, 377 U.S. 126, reversing per curiam the

Supreme Court of Mississippi.

In Alabama the remedy of appeal through the state

courts seems to be worse than useless in labor injunction

cases, at least from the union standpoint. The 1951 Senate

Committee study contains the following passage (p. 93):

“ A complainant has the right in Alabama, however, to

re-present its bill of complaint to a higher court if the

lower court refuses to grant relief without a hearing.

Several cases were found where the court of appeals

or supreme court (Alabama has an intermediate and

supreme court) granted ex parte orders, previously

denied and set for hearing in the circuit court. The

union attorneys claim the circuit is then reluctant to

(9)

(10)

dissolve the higher court’s ex parte order when it

comes to a hearing for a temporary injunction.12

12 The inference is that the circuit court judge may feel a modi

fication or dissolution of the higher court’s order will not stand if

appealed. A reported ease serves as an illustration.

'The circuit court denied an ex parte request in which the em

ployer sought to restrain a strike and all picketing on charges

of a union breach of contract. Within a day the Alabama Court

of Appeals granted the order ex parte. Upon hearing, the circuit

court modified the order to allow truthful and peaceful picketing,

although the strike was still enjoined. Upon appeal, the picketing

was again enjoined (Alabama Cartage Company, Inc. v. Team

sters, 34 So.2d 576, 21 L.R.R.M. 2682; Jefferson County Circuit

Court, June 20, 1947.)”

Here again, the situation does not seem to have changed

since 1951. Consider, for example, Radio & Television

Broadcast Technicians Local Union 1284 v. Broadcast

Service of Mobile, 380 U.S. 255. There the Circuit Court

of Mobile County issued a temporary injunction against

peaceful picketing on September 13, 1962; but on May 23,

1963, after hearing on the merits, it dissolved the injunc

tion in deference to NLRB jurisdiction. But on December

12, 1963, the Alabama Supreme Court unanimously re

versed, and directed that the temporary restraining order

be reinstated. Its opinion declares (55 LRRM 2005): “ It

should be made clear that we have made no attempt to

decide the merits of this case * * On March 15, 1965,

this Court reversed per curiam.

When a union which is conducting an organizing cam

paign or strike is faced with an injunction against picket

ing or striking, and its counsel believes that the court had

no jurisdiction to issue the injunction, or that the injunc

tion violates the Fourteenth Amendment, what is the union

to do? The opinion of the Court in this case seems to say

that the union should obey the injunction, while seeking to

have it modified or set aside by the state trial or appellate

(11)

courts. But all experience shows that this course is illusory.

If an organizing campaign or strike is stopped, it cannot

be turned on again like a water spigot. The organizing

campaign will have lost its momentum and the strike have

been broken. Months and years will pass while the illegal

injunction continues in effect until the union disappears.

To say in this context that a union must always obey an

injunction is to permit state courts to stultify the National

Labor Relations Act and even the Constitution of the Unit

ed States, and the courts of several States have shown

that that is just what they will do.

Unless the right to organize is to be completely destroyed

over wide areas of the country, a union which is conducting

an organizing campaign or strike must have the right to

ignore, though at its peril, an injunction against picketing

or striking- which it believes to be illegal. If the injunction

is ultimately adjudged to be lawful, the union can be pun

ished for contempt, but if the injunction is ultimately ad

judged to be unlawful there is no reason why the union

should be subject to punishment for having refused to

surrender the most basic rights of workers in deference

to an illegal decree.

This doctrine which we urge has long prevailed in many

States, and it has not produced any breakdown of law and

order, for the evident reason that a union will not usually

risk punishment for contempt by disobeying an injunction

unless it is sure of its legal ground. According to the

Court’s opinion, the legality of an injunction may be chal

lenged on contempt in Wisconsin but not in Alabama. Does

the Court really think that these divergent rules insure

“ respect for judicial process” and “ the civilizing hand of

law” in Alabama, and not in Wisconsin!

Indeed the right to question the legality of an injunction

in contempt proceedings is itself a feeble and inadequate

(12)

remedy. Unions or employees ignoring an injunction will

do so at peril of fine and perhaps imprisonment if the in

junction is ultimately held lawful. The job of the em

ployees will also he at hazard. Moreover in the southeast,

and particularly its rural areas, those ignoring an in

junction, or striking or picketing at all for that matter, do

so at peril of rough treatment from the police.

The reasons we want the right to ignore an illegal in

junction— so perilous a proceeding can hardly be called a

remedy—are that that is the only course which may keep

a strike or organizing campaign alive, and that the contrary

rule will encourage even more flagrant abuses of the labor

injunction by state courts.

2. The decision permits the use of unconstitutional li

censing ordinances to bar unions. A second legal, or rather

illegal, device which is widely used in southeastern States

to bar unions from particular localities is a municipal

licensing ordinance. These ordinances make it a crime for a

union or union organizer to solicit anyone to join a union

without first securing a license. Usually an exorbitant license

fee is fixed, and sometimes a daily fee or a fee for each per

son joining. It has long been settled, or as settled as the

decisions of this Court can make it, that these ordinances

are unconstitutional, yet they continue to be used to break

up organizing campaigns; and we are fearful that the deci

sion of the Court in the present case will encourage the use

of these ordinances by compelling compliance with injunc

tions against organizing without a license, even though the

licensing ordinance is unconstitutional on its face.

Normally no effort is made to give even a pretense of con

stitutionality to these ordinances. Thus the ordinance,

adopted in 1954, which the Court held invalid in Staub v.

City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313, not only gave the mayor and

city council complete discretion to grant or -withhold a

(13)

license, but required payment of a license fee of $2,000 per

year, plus $500 for each member obtained. No lawyer could

have supposed, in view of such prior decisions as Lovell v.

City of Griffin, 303 U.S. 444, that the Baxley ordinance

would survive, but it served its purpose, which was to stop

a particular union organizing drive.

Here, too, as in the use of labor injunctions, the AFL-CIO

and its affiliates encounter a regular pattern. In many in

stances as soon as an organizing campaign gets under way

an ordinance like the Baxley ordinance is passed, 5 and the

union organizers are arrested, and the organizing campaign

is effectively arrested too. The organizers are usually re

leased on bond after a few days, but are afraid to resume

organizing in view of the likelihood of recurrent arrests,

and leave town. Prosecutions under these ordinances are

usually dropped as soon as the organizing drive is aban

doned, and few cases involving them find their way into the

appellate courts.6

That being so, it is difficult to say how prevalent these

ordinances are. For example, files of the AFL-CIO show that

8 Several years ago AFL-CIO organizers were arrested in Flor

ence, South Carolina, purportedly under a local licensing ordi

nance. When the attorney retained by the AFL-CIO sought to ob

tain the text of the ordinance he met with evasion, but was

eventually told that “ the ordinance hasn’t been passed yet.”

6 The L.R.R.M. digests (key no. 73-50) list about 15 appellate

decisions from 1943 to date. All of the reported decisions are from

the southeastern States or Kentucky, except for In re Porterfield,

28 Cal.2d 91, 168 P.2d 706 (Calif. Sup. Ct., 1946), holding a li

censing ordinance invalid. Several anti-union municipalities in

rural California, and more recently in rural Kentucky, adopted

“ right-to-work” ordinances, but these ordinances were held in

valid. Chavez v. Sargent, 52 Cal.2d 162, 339 P.2d 801 (Calif. Sup.

Ct., 1959) ; Kentucky State AFL-CIO v. Puckett, 391 S.W.2d

360, 59 L.R.R.M. 2337 (Ky. Ct. App., 1965). Presumably these

ordinances were meant to lay a basis for enjoining strikes and

picketing as seeking an illegal union shop, i.e., the technique dis

approved by this Court in Curry.

(14)

five separate cities in Arkansas enacted licensing ordinances

and that several convictions resulted, but in all instances the

cases were dropped when the unions appealed, so that no re

ported decision resulted. City ordinances are not compiled

anywhere, or even printed except in the case of the larger

cities. Often the only record of municipal ordinances is a

typed file kept at the city hall, and even the attorneys prac

ticing in a State do not know which towns have union

licensing ordinances, or whether a particular town con

siders that its ordinance is still in effect or not. Sometimes

licensing ordinances are repealed when union organizing

is no longer imminent, while at other times they languish in

limbo.

However, it is the belief of the AFL-CIO that a substan

tial number of these ordinances are still in existence, prin

cipally in the southeastern States. The brief for the appel

lant in Staub v. City of Baxley listed, beginning on p, 31,

30 of these ordinances. Perhaps a half dozen ordinances a

year come to the attention of the AFL-CIO legal staff in

Washington, but, as stated, we have no way of knowing

which ordinances are considered to be still in effect.

In any event, and no matter how flagrantly unconstitu

tional the ordinance, there is even now no clearly available

adequate remedy. And, as stated, we are fearful that the

decision of this Court in the present case will make these

ordinances even more effective by encouraging the device

of incorporating them in injunctions, just as the parade

ordinance was transformed into an injunction in the present

case.

If prosecutions for organizing without a license could be

removed to federal court, that would be an effective remedy,

but they cannot. See City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384

IJ.S. 808.

(15)

A federal district court injunction against enforcement

of a licensing ordinance would likewise be an effective rem

edy, and it may be that such a suit will lie under the recent

decision of this Court in Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S.

479. However, such earlier decisions as Douglas v. City of

Jeanette, 319 U.S. 157, seemed to preclude an injunction,

and they have usually been denied in the lower federal

courts.7

Hence the only remedy which has clearly been held avail

able to contest the constitutionality of these licensing ordi

nances is an appeal from a criminal conviction, as in Staub.

As stated, even this remedy is quite ineffective because in

the meantime arrests will have broken up the organizing

drive.

However, we are concerned that even this inadequate

remedy will be undercut by the decision of this Court in this

case. The opinion of the Court acknowledges that the Bir

mingham parade ordinance was of doubtful constitutional

ity, but nevertheless holds that the petitioners were bound

to obey the injunction against parading without a license.

Any such doctrine will be utterly destructive in numerous

towns and cities, of any right to organize, or, for that mat

ter, to carry on any sort of agitation not acceptable to the

municipal authorities.

3. The decision exalts a state procedural, rule over basic

substantive federal rights. We submit that in several re

spects the decision in the present case is wholly inconsistent

with long established and sound Supreme Court doctrine.

7 Injunctions were denied in Steelworkers v. Fuqua, 253 F. 2d

594 (6th Cir., 1958); Steelworkers v. Bagwell, 239 F. Supp. 626,

(W.D.N.C., 1965); and Starnes v. City of Milledgeville, 56 F.

Supp. 956 (M.D. Ga., 1944). An injunction was granted in Den

ton v. City of Carrollton, 235 F. 2d 481 (5th Cir., 1956).

(16)

In the first place no state procedure can be regarded as

valid, so that resort to it is required, if the procedure itself

demands a substantial relinquishment of constitutional or

other important federal rights.

The opinion of the Court holds that the defendants were

required to comply with the parade ordinance by applying

for a permit, notwithstanding the delay involved and even

assuming that the ordinance was unconstitutional, and that

they were even more compelled to comply with the tem

porary injunction, unless and until it was set aside on

appeal, even if both injunction and underlying ordinance

were unconstitutional. Yet resort to those procedures would

have required that the defendants forego their constitu

tional rights of free speech and assembly, at the behest

of an illegal ordinance and order, during the height of the

controversy in which they were engaged. It would have

required them to postpone exercising their vital constitu

tional rights in deference to unconstitutional demands dur

ing the very period when the vindication of those rights

was most important to them.

In a labor relations context this doctrine means that

unions and workers must forego their right to picket or

strike, in deference to an unconstitutional ordinance or an

illegal injunction, at the height of a strike or organizing

campaign. It means that an unscrupulous city council or

judge can break any strike or organizing campaign, even

if the organizers or strikers are so sure that the ordinance

or injunction is illegal that they are ready to risk jail if

they are wrong. We submit that any state procedural rule

which requires forfeiture of federal rights in deference to

an illegal ordinance or court order is itself an invalid re

straint. That is what this Court held in Staub v. City of

Baxley and In re Green, 369 TT.S. 689.

(17)

We respectfully urge that the Court adopt the following

formulation of Mr. Justice Clark, dissenting in Williams v.

Georgia, 349 U.S. 375, 399:

“A purported state ground is not independent and

adequate in two instances. First, where the circum

stances give rise to an inference that the state court

is guilty of an evasion—an interpretation of state law

with the specific intent to deprive a litigant of a federal

right. Second, where the state law, honestly applied

though it may be, and even dictated by the precedents,

throws such obstacles in the way of enforcement of fed-

ral rights that it must be struck down as unreasonably

interfering with the vindication of such rights.”

If, however, these state procedural rules are not them

selves unconstitutional, surely then the issue becomes one

of weighing the state interest against the federal right. As

the court said in Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443, 447-

448:

“ [A] litigant’s procedural defaults in state proceed

ings do not prevent vindication of his federal rights

unless the State’s insistence on compliance with its

procedural rule serves a legitimate state interest. In

every case we must inquire whether the enforcment of a

procedural forfeiture serves such a state interest. If it

does not, the state procedural rule ought not be per

mitted to bar vindication of important federal rights.”

Here the state interest is in compelling respect for even

illegal court decrees or city ordinances until set aside, while

the federal rights involved are basic constitutional rights

of freedom of speech, assembly, etc. We submit that in any

such weighing the federal rights should prevail. That is

additionally so because the state interest is adequately in

sured by the fact that any person ignoring an injunction or

an ordinance will do so on pain of criminal punishment if

he is mistaken in his belief of invalidity.

(18)

Numerous state procedural rules, which may be valid in

themselves, have been held to rest on a state interest too in

substantial to preclude vindication by this Court of constitu

tional or other federal rights. See, e.g., Staub v. City of

Baxley, 355 U.S. 313; Liner v. Jafco, Inc., 375 U.S. 301;

Construction & General Laborers Union, Local 438 v.

Curry, 371 U.S. 542; Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham,

376 U.S. 339.

Finally, it should be noted that the result so far reached

in this case is neither dictated nor even supported by

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258. No

member of the Court in that case even suggested that its

holding was meant to give trial courts an unreviewable

power to punish for contempt of injunctions issued without

jurisdiction or in violation of constitutional limitations. To

the contrary Mr. Justice Frankfurter in his concurring

opinion, joined by Justice Jackson, declared (330 U.S. at

310):

“To be sure, an obvious limitation upon a court can-

cannot be circumvented by a frivolous inquiry into the

existence of a power that has unquestionably been with

held. Thus, the explicit withdrawal from federal dis

trict courts of the power to issue injunctions in an

ordinary labor dispute between a private employer

and his employees cannot be defeated, and an existing

right to strike thereby impaired, by pretending to en

tertain a suit for such an injunction in order to decide

whether the court has jurisdiction. In such a case, a

judge would not be acting as a court. He would be a

pretender to, not a wielder of, judicial power.”

The opinion of Mr. Chief Justice Vinson8 likewise declared

8 This opinion is labeled “ Opinion of the Court” but had the

assent only of Justices Vinson, Burton and Reed.

(19)

that an injunction need not be respected (330 U.S. at 293)

“were the question of the jurisdiction frivolous and not

substantial,” and that an order must be obeyed only if

“ issued by a court with jurisdiction over the subject matter

and person.”

Subsequent decisions of the Court have made it clear that

the Mine Workers doctrine does not require obedience to

any and every injunction. A majority in In re Green, 369

U.S. 689, clearly held that an injunction issued by a state

court which lacked jurisdiction because of federal preemp

tion could be challenged in contempt proceedings. Indeed

Justices Harlan and Clark dissented on the ground that the

Court’s opinion gave (369 IJ.S. at 693) “ only a passing

glance at the Mine Workers decision.”

In Johnson v. Virginia, 373 IJ.S. 61, this Court set aside

per curiam a contempt conviction where the defendant had

refused to obey an order of a state judge to observe segre

gated seating in the courtroom. The Court did not so much

as advert to any such proposition as that the judge’s order

bad to be obeyed until set aside; and of course the Court

was correct, for not only was the order unconstitutional

but even temporary compliance with it would have de

prived the defendant of a basic constitutional right.

Similarly in Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650, the

Court reversed per currant a contempt conviction of a wit

ness who bad refused to answer questions until the pro

secuting attorney would address her as “ Miss.” Here

again there is no suggestion in the Court’s opinion that the

witness was bound to comply with the Court’s order until

it was set aside. That case came from the same jurisdiction

as the present, i.e., Alabama; and see also Fields v. City

of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248.

CONCLUSION

(20)

For the reasons stated it is respectfully submitted that

the petition for rehearing should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J. A lbert W oll

General Counsel, AFL-CIO

Robert C. Mater

L aurence Gold

736 Bowen Building

815 Fifteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

Thomas E. H arris

Associate General Counsel, AFL-CIO

815 Sixteenth Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

July 1967