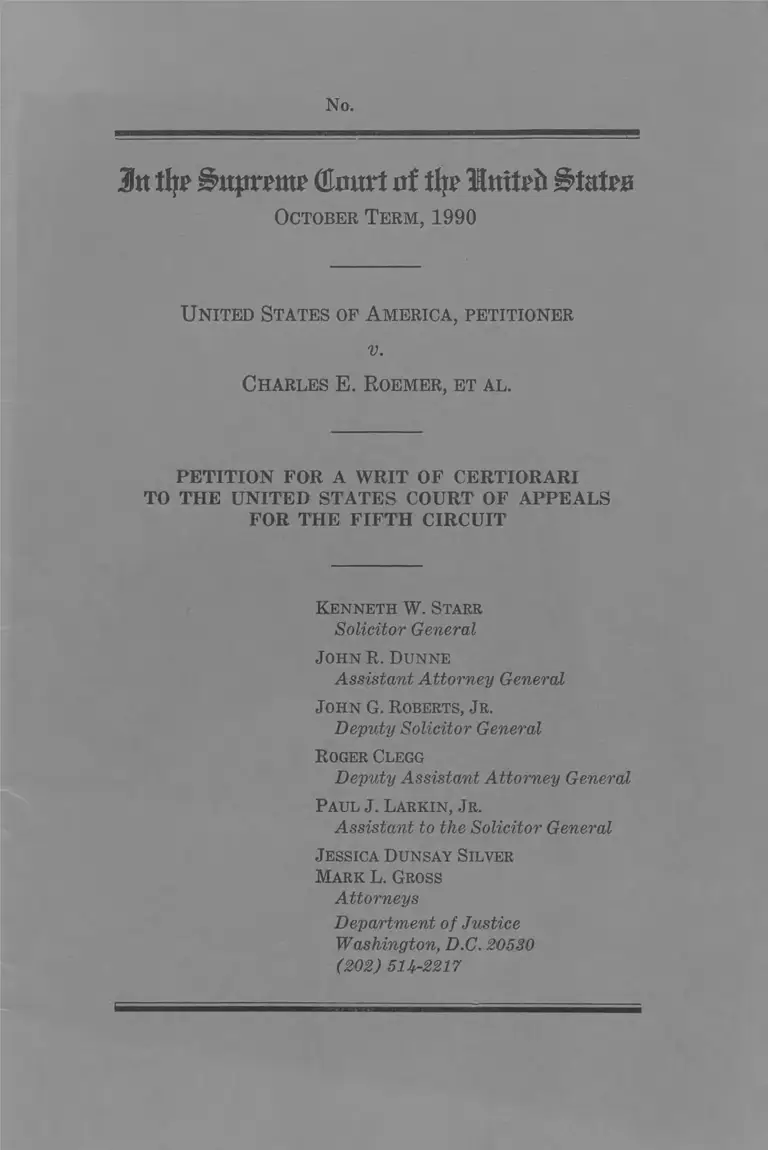

United States v. Roemer Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

December 31, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Roemer Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1990. 76e4a5ca-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69c28e5d-e8cc-4410-9501-9d1a600c2849/united-states-v-roemer-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

In % &nprmv (Emtrt nt % llnxUb States

Oc to ber T e r m , 1990

U n it e d St a t e s of A m e r ic a , p e t it io n e r

v.

C h a r l e s E . R o e m e r , e t a l .

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E FIFTH CIRCUIT

Kenneth W . Starr

Solicitor General

John R. Dunne

Assistant Attorney General

John G. Roberts, Jr.

Deputy Solicitor General

Roger Clegg

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Paul J. Larkin , Jr.

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Mark L. Gross

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 514-2217

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the results test o f Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973, applies to the

election of state court judges.

(i)

n

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS

In addition to the parties listed in the caption, the

following were parties in the courts below: Ronald

Chisom; Marie Bookman; Walter W illard; Marc

Morial; Henry Dillon III; the Louisiana Voter

Registration/Education Crusade; Edwin Edwards,

in his capacity as Governor of the State o f Louisi

ana; W, Fox McKeithen, in his capacity as Secretary

of State of the State o f Louisiana; Jerry M. Fowler,

in his capacity as Commissioner of Elections of the

State o f Louisiana; Pascal F. Calogero, Jr.; and Wal

ter F. Marcus, Jr.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions below ............................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction.................................................................................. 2

Statutory provision involved ................................................ 2

Statement....................................................................................... 3

Reasons for granting the petition........................... 8

Conclusion..................................................................................... 14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969) ................................................................................ 10

Brooks V. Georgia State Bd. of Elections, 111

S. Ct. 13 (1 9 9 0 ).......................................................... 12

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1 9 8 8 ) ................................................................................ 4, 5

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La.

1987), rev’d, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied sub nom. Roemer v. Chisom, 488 U.S. 955

(1988) ............................................................................... 6

City of Mobile V. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980)........ 5 ,11

Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C.

1985), aff’d mem., 477 U.S. 901 (1986)................ 5, 12

League of United Latin American Citizens Coun

cil No. UU3J+ v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir.

1990), petition for cert, pending, No. 90-813......6, 7, 8,

12,13

League of United Latin American Citizens Council

No. UU3U V. Mattox, 902 F.2d 293 (5th Cir.

1990).......................... 2

Mallory V. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988)....... 9

Martin V. Haith, 477 U.S. 901 (1986) ... ..................... 12

SCLC V. Siegelman, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala.

1989) ................................................................................... 9

SCLC V. Siegelman, No. 88-D-462-N (M.D. Ala.

Dec. 5, 1990) ................................................................ 9

(III)

IV

Cases— Continued: Page

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1 9 6 6 )............................................................................... 10

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) ................ 6, 11

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La.

1972), aff’d mem., 409 U.S. 1095 (1973)........ . 7

White v. Reg ester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ..................... 11

Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696 F. Supp.

1563 (N.D. 111. 1988).................................................. 9

Constitution, statutes, and regulation:

U.S. Const.:

Amend. X IV (Equal Protection Clause)........... 3, 4

Amend. X V .................................................................. 3, 4

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1971 et seq. :

§ 2, 42 U.S.C. 1973 .................................................... passim

§ 2 (a ), 42 U.S.C. 1973(a)....................................... 2 ,11

§ 2 (b ), 42 U.S.C. 1973 (b ) ................ .................. 2, 6, 8, 11

§ 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c........................................5, 7, 8, 10, 12

§ 1 4 (c )(1 ) , 42 U.S.C. 19731(c)(1) (1976)...... 10

§ 14(c) (1 ), 42 U.S.C. 1973Z(c) (1) ................. . 4, 7

28 C.F.R. 51.55(b) (2) ................................................... 10

Miscellaneous:

Extension of the Voting Rights A ct: Hearings Be

fore the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm, on the Judiciary,

97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1 9 8 1 ).................................... 12

The American Bench (Mr. Hough 4th ed. 1987-

1988) ................................................................................. 9

Voting Rights A ct: Hearings on S. 53, S. 1761,

S. 1975, S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 Before the Sub

comm. on the Constitution of the Senate Comm,

on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982).... 12

3n % Brtjmw (Emtrt rrf %

O ctober T e r m , 1990

No.

U n it e d St a t e s of A m e r ic a , p e t it io n e r

v.

C h a r l e s E . R o e m e r , e t a l .

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The Solicitor General, on behalf of the United

States, petitions for a writ o f certiorari to review the

judgment o f the United States Court o f Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in this case.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (90-757 Pet.

App. la -3 a )] is reported at 917 F.2d 187. The opin

ion of the district court (excerpted at Pet. App. 4a-

64a) is not reported. An earlier opinion of the court

of appeals is reported at 839 F.2d 1056. An earlier

opinion o f the district court is reported at 659 F.

Supp. 183.

1 The petition appendix in No. 90-757 contains the mate

rials required by this Court’s Rule 14.1 (k ). Unless otherwise

noted, we will hereafter use the term “Pet. App.” to refer

to the petition appendix in No. 90-757.

(1 )

2

The panel opinion of the court of appeals in the

related case of League of United Latin American

Citizens Council No. UU%U v. Mattox is reported at

902 F.2d 293. The en banc decision of the court of

appeals in that case is reported at 914 F.2d 620 and

is reprinted in the appendix to the petition (at la -

182a) in No. 90-813.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court o f appeals was entered

on November 2, 1990. The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

STATUTORY PROVISION INVOLVED

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. 1973, provides as follows:

(a ) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall

be imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a de

nial or abridgement of the right of any citizen

of the United States to vote on account of race

or color, or in contravention of the guarantee set

forth in Section 1973b(f) (2 ) of this title, as

provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b ) A violation of subsection (a ) of this sec

tion is established if, based on the totality of cir

cumstances, it is shown that the political proc

esses leading to nomination or election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally

open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a ) of this sec

tion in that its members have less opportunity

than other members of the electorate to partici

pate in the political process and to elect repre

sentatives of their choice. The extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected

3

to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided,

That nothing in this section establishes a right

to have members of a protected class elected in

numbers equal to their proportion in the popu

lation.

STATEM ENT

1. Louisiana elects its seven justices to the state

supreme court from six judicial districts for ten-year

terms. The First District, which includes Orleans,

St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson Parishes,

elects two justices at-large. Each of the other five

districts elects one justice. Pet. App. 7a-8a.

In September 1986, plaintiffs Ronald Chisom et

al., black registered voters in Orleans Parish, Louisi

ana, filed a complaint, alleging that the system for

electing two state supreme court justices from the

First Judicial District in at-large elections had the

purpose and the effect o f diluting black voting

strength, in violation of Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973, the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and

the Fifteenth Amendment.2 The plaintiffs alleged

that the elections in the First District, in which a

majority of the population and registered voters are

white, had been marked by racial bloc voting and

other effects of past official discrimination; that few

blacks had been elected to public offices in the dis

trict; that there was no justifiable basis for singling

out the First District for multi-member elections;

and that the First District could be divided into two

districts, each of which, like the remaining judicial

districts, would elect one justice. The plaintiffs ar

2 The plaintiffs have filed a petition for writ of certiorari

in this case as well, No. 90-757.

4

gued that an appropriate division along parish lines

would produce one district— Orleans Parish— in

which a majority of the population and registered

voters would be black. Pet. App. 4a-6a.

2. The district court dismissed the complaint, hold

ing that Section 2 o f the Voting Rights Act of 1965

did not apply to judicial elections. Chisom v. Ed

wards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La. 1987). The court

found that Section 2, by its terms, is violated only

when minority voters prove that they lack an equal

opportunity “ to elect representatives of their choice.”

Section 2 therefore does not apply to judicial elec

tions, the court held, since judges are not “ represen

tatives.” 659 F. Supp. at 185-187.3

3. Plaintiffs appealed and the court of appeals re

versed, holding that Section 2 applies to judicial elec

tions. Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1988) (Chisom I). The court stated that the orig

inal language of Section 2, enacted in 1965, prohib

ited discrimination in any “ voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice or proce

dure,” and that Section 1 4 (c ) (1 ) of the Act, 42

U.S.C. 1 9 7 3 £ (c )(l) , defined voting as applying to

“ any primary, special, or general election * * * with

respect to candidates for public or party office and

propositions for which votes are received in an elec

tion,” demonstrating Congress’s intent to prohibit a

broad range of discriminatory electoral practices.

3 The district court also dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, on the

ground that the plaintiffs had not adequately alleged intent to

discriminate. 659 F. Supp. at 187-189. The court of appeals

reversed and reinstated those claims, Chisom v. Edwards, 839

F.2d 1056, 1064-1065 (5th Cir. 1988), but after trial the dis

trict court held that the plaintiffs had not proved intentional

discrimination, Pet. App. 63a-64a. Those claims are no longer

at issue.

5

839 F.2cl at 1059-1060. Because judges are “ candi

dates for public or party office,” the court held that

the 1982 amendments to Section 2, which added the

term “ representatives” on which the district court

relied, still applied to judicial elections. The 1982

amendments, the court concluded, did not limit the

Act’s coverage, but instead enacted the “ results” test

that this Court had rejected in City of Mobile v. Bol

den, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). 839 F.2d at 1059-1061.

The court of appeals rejected the district court’s re

liance on the line o f “ one person, one vote” cases

holding that judges are not representatives, on the

ground that cases involving racial discrimination

are not governed by the same considerations as cases

involving nonracial reapportionment. Id. at 1060-

1061.

The court also found relevant some secondary

sources of congressional intent. For example, the

court saw some indication in the legislative history

of the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendments that Con

gress understood Section 2 to apply to judicial elec

tions. 839 F.2d at 1061-1063. The court found rele

vant the holding in Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp.

410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), summarily aff’d mem., 477

U.S. 901 (1986), that Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973c, which requires pre

clearance of changes in electoral procedures in some

States and which has coverage language nearly iden

tical to that o f Section 2, applies to judicial elections.

839 F.2d at 1063-1064. Finally, the court noted that

the Attorney General has consistently interpreted the

Voting Rights Act as covering judicial elections. Id.

at 1064.

The defendants sought review in this Court, which

denied certiorari sub. nom. Roemer v. Chisom, 488

U.S. 955 (1988).

6

4. A fter trial,4 the district court held that the

plaintiffs had failed to prove a violation of Section 2

under the standards set forth in Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1986). Specifically, the court held that

plaintiffs had failed to prove that black voters are

geographically compact or politically cohesive, or that

there was significant racial bloc voting. Pet. App.

16a-62a.

5. The plaintiffs and the United States appealed,

claiming that the district court’s factual findings

were clearly erroneous. Before the appeal was de

cided, however, the Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc,

decided League of United Latin American Citizens

Council No. M3U (LULAC) v. Clements, 914 F.2d

620 (1990) (reprinted at 90-813 Pet. App. la-182a).

The plaintiffs in LULAC alleged that the at-large

election o f trial judges in nine Texas counties diluted

the ability of minority populations in each county to

elect candidates o f their choice, in violation of Sec

tion 2. In LULAC, the en banc Fifth Circuit, by a

7-6 vote, held that the Section 2 vote dilution test

does not apply to the election of judges, and expressly

overruled Chisom I.

The majority held that while Section 2 generally

applies to judicial elections the vote dilution test of

Section 2 (b ) does not, since judges are not “ repre

sentatives” under Section 2 (b ) or as a general mat

ter. LULAC, 914 F.2d at 625-627. As support for

its interpretation, the majority pointed out that the

concept of minority vote dilution was modeled on the

vote dilution standards developed in “ one-person, one-

vote” cases, id. at 627-628, and that by 1982 at least

4 The United States intervened in the district court after

the remand for trial. The United States had participated in

the earlier stages of the litigation as an amicus curiae.

7

15 federal court decisions, including a decision by

this Court— Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453

(M.D. La. 1972) (three-judge court), summarily

aff’d mem., 409 U.S. 1095 (1973)— had ruled that

“ the judicial office is not a representative one, most

often in the context of deciding whether the one-

man, one-vote rubric applied to judicial elections,”

914 F.2d at 626; id. at 626 n.9. Applying the canon

of construction that Congress is presumed to be aware

of and endorse “ the uniform construction” placed on

a term, the majority determined that Congress used

the term “ representative” in order to apply the new

results test of Section 2 to elections for representa

tive, political offices but not to vote dilution claims

in judicial contests. Id. at 628-629. The majority

found unpersuasive the fact that the definitional pro

vision of the Act, 42 U.S.C. 1 9 7 3 Z (c )(l), defined

“ voting” by reference to “ candidates for public or

party office,” because the term “ representative” in

Section 2 was more specific. LULAC, 914 F.2d at

629. Because Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act does

not use the word “ representatives,” the majority also

found irrelevant the fact that Section 5 applies to

judicial elections. Ibid.

Six members of the en banc court, in three separate

opinions, concluded that the dilution test of Section 2

applies to judicial elections. Judge Higginbotham,

joined by three other judges, concluded that the

term “ representatives” encompasses elected judges.

LULAC, 914 F.2d at 635-645. He nevertheless con

cluded that the at-large election o f trial judges in

Texas does not violate Section 2 since each trial

judge, like each governor, occupies a so-called “ single

person office” whose electorate cannot be further sub

divided. In such instances, he said, electing all trial

8

judges on an at-large basis does not dilute minority

voting strength. Id. at 645-651. Concurring spe

cially, Chief Judge Clark said that he agreed with

Judge Higginbotham, adding that vote dilution anal

ysis might be appropriate when a State elects its

judges from single-member districts. Id. at 631-634.

Judge Johnson dissented. In his view, the Section

2 (b ) vote dilution test applies to judicial elections,

and the “ single-person office” exception did not apply

in the LULAC setting, because at the trial court

level there were multiple officeholders. 914 F.2d at

651-671.

6. Thereafter, the court of appeals issued a per

curiam opinion in this case. Relying on LULAC, the

court remanded this case to the district court with

directions to dismiss the Voting Rights Act claims

for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be

granted. Pet. App. la-3a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

The court of appeals has erroneously decided a

question of considerable public importance in a man

ner that expressly conflicts with a decision of an

other court of appeals. By holding that the vote di

lution test of Section 2 (b ) of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 does not apply to the election of judges, the

court of appeals has erroneously exempted a signifi

cant category of elections from the broadly worded

text o f that law. By single-mindedly focusing on the

term “ representatives,” the court of appeals con

strued Section 2 in a manner that is in tension with

this Court’s interpretation of Section 5 o f the Act,

and contrary to the broad remedial purposes under

lying the 1982 amendments to Section 2. Moreover,

the question presented will recur with regularity

since a majority of the States elect at least some

9

judges at the trial or appellate levels. Accordingly,

review by this Court is clearly warranted.

1. The Fifth Circuit’s decisions in this case and

in LTJLAC directly conflict with the Sixth Circuit’s

decision in Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (1988).5

In Mallory, the Sixth Circuit held that the Section 2

vote dilution test applies to the election of municipal

judges, expressly rejecting the argument that judges

are not “ representatives” within the meaning of Sec

tion 2. In fact, the Sixth Circuit’s analysis in Mal

lory of the Section 2 question was identical to the

Fifth Circuit’s analysis of the same issue in Chisom,

I, which that court overuled in LULAC. Compare

Mallory, 839 F.2d at 277-281, with Chisom I, 839

F.2d at 1059-1064. This square conflict between the

Fifth and Sixth Circuits warrants review by this

Court.

2. The question presented is of sufficient national

importance and will recur with a sufficient degree of

regularity that review is warranted. Forty-one States

elect some or all of their judges, see The American

Bench (M. Hough 4th ed. 1987-1988), and suits have

been filed in ten States alleging that the election of

judges dilutes minority voting strength in violation

of Section 2. 90-757 Pet. 14-15. Resolution of this

question is therefore o f substantial interest to the

United States, which has primary responsibility for

enforcing Section 2. In addition, the Attorney Gen

5 District courts in the Seventh and Eleventh Circuits have

also held that the Section 2 vote dilution test applies to

judicial elections. Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696

F. Supp. 1563 (N.D. 111. 1988) ; SCLC v. Siegelman, 714

F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989). The district court in Siegel

man recently reaffirmed its earlier decision and noted its

disagreement with LULAC. SCLC V. Siegelman, No. 88-D-

462-N (Dec. 5, 1990).

10

eral is responsible under Section 5 for reviewing vot

ing changes, and must withhold preclearance if he

concludes such action “ is necessary to prevent a clear

violation of amended section 2.” 28 C.F.R. 51.55

(b ) (2 ) . A decision that Section 2’s dilution stand

ard does not apply to judicial elections thus affects

the manner in which the government reviews pro

posed voting changes in judicial election procedures

under Section 5.

3. The Fifth Circuit in LULAC erred in ruling

that the vote dilution test of Section 2 does not ap

ply to judicial elections. Congress enacted the Vot

ing Rights Act of 1965 in order to “ rid the country

of racial discrimination in voting.” South Carolina

v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 365 (1966). The orig

inal text of Section 2 stated that “ [n ]o voting quali

fication or prerequisite to voting, or standard, prac

tice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any

State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the

rights of any citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race or color.” The 1965 Act defined the

term “ voting” as “ any primary, special, or general

election * * * with respect to candidates for public

or party office * * *.” 42 U.S.C. 1 9 7 3 £ (c )(l) (1976).

That definition was sufficiently broad to encompass

elections of any type for any office, including elec

tions for judges. See Allen v. State Bd. of Elections,

393 U.S. 544, 567 (1969) (Congress intended “ to

give the Act the broadest possible scope” ). A can

didate who stands in a primary or in the general

election for a position on the state supreme court

easily fits within that definition. Thus, it is clear

that the elections at issue here were covered by the

original version of Section 2.

The 1982 amendments to Section 2 did not change

that result. Congress did not amend Section 2 to

11

shorten the reach of that law; instead, Congress

amended Section 2 in order to enact the “ results”

test that this Court had rejected in City of Mobile v.

Bolden, supra. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.

30, 35 (1986). Congress accomplished that result by

dividing Section 2 into two parts, adding to subsec

tion (a ) the term “ results,” and defining the new re

sults test in subsection (b ). At the same time, Con

gress did not alter that portion of the text of Section

2 defining the reach of the law (i.e., the language re

ferring to “ :[n]o voting qualification” , etc.). Thus,

subsection (a ) , like its predecessor, the 1965 version

o f the Act, encompasses elections of every stripe;

nothing excludes judicial elections.

In reaching the contrary result, the Fifth Circuit

relied heavily on Congress’s use of the term “ repre

sentatives” in subsection (b ). This was mistaken.

Congress patterned the phrasing of the results test in

subsection (b ) after a passage in White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 755 (1973). White involved a challenge to

the election of state legislators, and the relevant pas

sage focused on whether minority voters “ had less

opportunity than did other residents in the district

to participate in the political processes and to elect

legislators o f their choice.” Id. at 766. Congress in

corporated that principle into subsection (b ), but

substituted the term “ representatives” for “ legisla

tors.” Although use of the term “ legislators” would

not have included judges, the term “ representative”

does not necessarily exclude them. Because nothing

in the legislative history of the 1982 amendments in

dicates that the election of judges is excluded from

the scope of Section 2 (in fact, there is some evidence

12

that Congress knew that Section 2 applied to such

elections6), the Court can give the term “ representa

tive” the natural interpretation that the facts of this

case show to be reasonable.

The Fifth Circuit’s decisions in this case and

LULAC create an anomaly in the application of Sec

tions 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act. This Court

has twice held that the Section 5 preclearance re

quirements apply to judicial elections, Martin v.

Haith, 477 U.S. 901 (1986 ); Brooks v. Georgia State

Bd. of Elections, 111 S. Ct. 13 (1990), but the Fifth

Circuit has now ruled that the vote dilution analysis

of Section 2 does not apply. The Fifth Circuit’s de

cisions lead to the “ incongruous result,” as Judge

Higginbotham noted in LULAC, 914 F.2d at 645,

that a covered State cannot implement a discrimina

tory voting procedure, but an existing discriminatory

procedure cannot be challenged under the very law

6 The House and Senate hearings contain various refer

ences to judicial elections, principally in the context of statis

tics indicating the progress made by minorities under the Act

up to 1982. See, e.g., Extension of the Voting Rights Act:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st

Sess. 38, 193, 239, 280, 503, 574, 804, 937, 1182, 1188, 1515,

1535, 1745, 1839, 2647 (1981) ; and Voting Rights A ct: Hear

ings on S. 53, S. 1761, S. 1975, S. 1992, and H.R. 3112 Before

the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 669, 748, 788-789 (1982). The

majority in LTJLAC dismissed the significance of these refer

ences, 914 F.2d at 629-630, but the importance of those refer

ences is not that they resolved the issue presented here. In

stead, they show that some members of Congress knew in

1982 that many state judges were elected, yet no one sug

gested that the Act should be redrafted to exclude judicial

elections.

13

Congress intended to be used as the vehicle to redress

such illegality.

The majority in LULAC erred in relying on the

line of cases holding, in the reapportionment context,

that judges do not have a “ representative” function.

Section 2 did not codify the “ one-person, one-vote”

inquiry; rather, it sought to ensure that minority

votes are not cancelled out by means of dilutive elec

toral systems. For that reason, there is no require

ment that the term “ representative” be read to ex

clude judges.

4. As noted above, the plaintiffs in this case have

filed a certiorari petition seeking review of the judg

ment below, Chisom v. Roemer, No. 90-757. In addi

tion, the plaintiffs in LULAC have also filed a certio

rari petition seeking review of the Fifth Circuit’s

judgment there. Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Mattox,

No. 90-813. This case involves the election of appel

late judges on a district-by-district basis, while

LULAC involves the at-large election o f trial judges.

The LULAC case also involves a question not pre

sented in this case, namely, whether the “ single

member office” exception applies to the election of

Texas trial court judges. This case and LULAC,

taken together, afford the Court an opportunity to

consider whether Section 2 applies to judicial elec

tions in a complete factual context. For that reason,

we urge the Court to grant all three petitions, to con

solidate for argument our petition in this case with

the petition filed by the private plaintiffs in No. 90-

757, and to set this case for oral argument in tandem

with the petition in No. 90-813. (Petitioners in No.

90-757 and in Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Mattox,

14

No. 90-813, have also urged the Court to grant re

view in both cases.) 7

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be

granted. The petition in Chisom v. Roemer, No. 90-

757, should also be granted, and it should be consoli

dated for oral argument with this petition. In addi

tion, the petition in Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Mat

tox, No. 90-813, should be granted, and that case

should be heard in tandem with this case and No.

90-757.

Respectfully submitted.

Kenneth W . Starr

Solicitor General

John R. Dunne

Assistant Attorney General

John G. Roberts, Jr.

Deputy Solicitor General

Roger Clegg

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Paul J. Larkin , Jr.

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Mark L. Gross

Attorneys

December 1990

7 Petitioners in Clark v. Roemer, No. 90-898, have filed a

petition for a writ of certiorari before judgment to the

Fifth Circuit. That case involves trial level judges and one

appellate district in Louisiana. That case, however, adds

nothing to the factual scenarios presented by Chisom and

LULAC, so separate review is not called for in that case.

☆ U . s . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE; 1 9 9 0 2 8 2 0 6 1 2 0 2 7 0