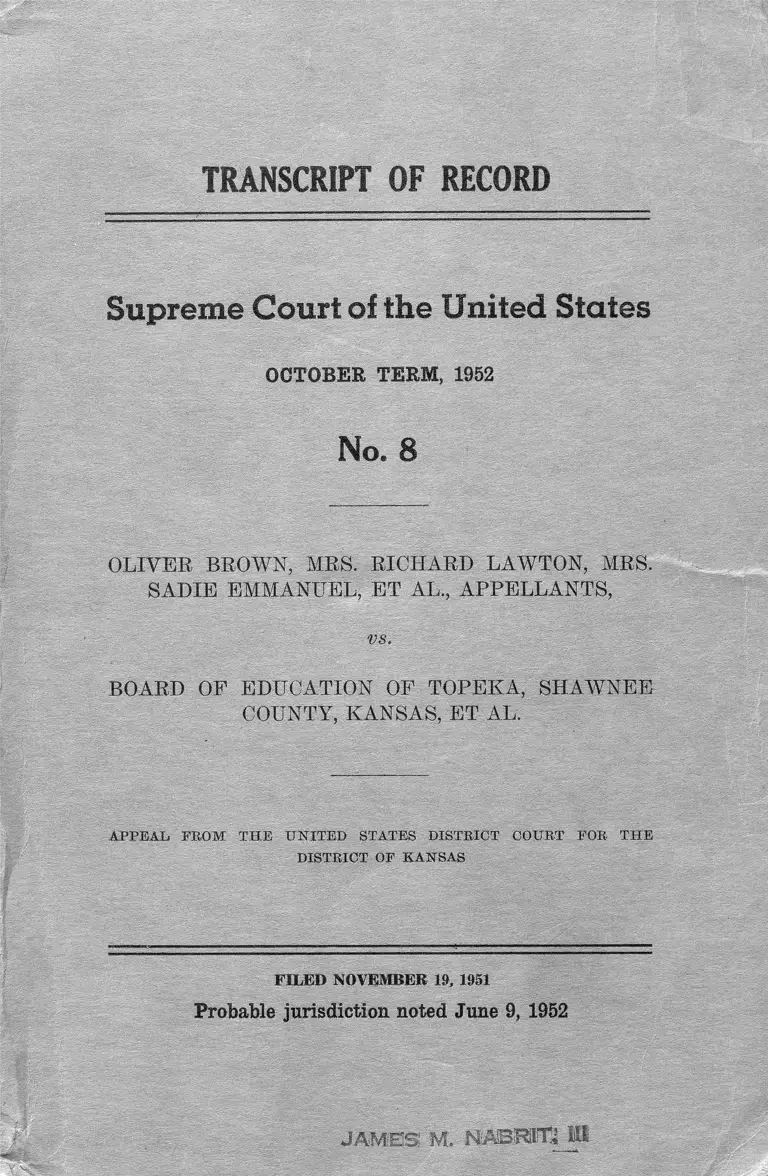

Brown v. Board of Education Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

November 19, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Transcript of Record, 1951. 65d4ddd5-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69c57503-d5dc-4526-a4ad-e851c6b9699d/brown-v-board-of-education-transcript-of-record. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1952

No. 8

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, MRS.

SADIE EMMANUEL, ET AL., APPELLANTS,

vs.

BOARD OP EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

DISTRICT OF KANSAS

FILED NOVEMBER 19, 1951

Probable jurisdiction noted June 9, 1952

JAM ES M. H

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1952

No. 8

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, MRS.

SADIE EMMANUEL, ET AL., APPELLANTS,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.

APPEAL, FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT1 COURT FOR THE

DISTRICT OF KANSAS

INDEX

Record from U.S.D.C. for the District of Kansas..............

Caption .................................... (omitted in printing) . .

Amended complaint .......................... ..............................

Motion for a more definite statement and to strike. . . .

Docket entry— Motion denied, except as to paragraph

8, which is to be amended............................................

Amendment to paragraph 8 of amended complaint. . . .

Answer to amended complaint as amended in para

graph 8 thereof...............................................................

Separate answer of the State of Kansas........................

Transcript o f procedings of pre-trial conference........

Appearances .............................................................

Colloquy between court and counsel......................

Reporter’s certificate.............. (omitted in printing) . .

Original Print

1 i

a

1 1

8 8

11 10

12 10

13 11

17 14

19 15

19 15

21 16

98

J udd & Defwbiler ( I nc.) , P rintees, W ashington, D. C., J udy 8, 1952.

— 2734

11 INDEX

Record from U.S.D.C. for the District of Kansas— Con

tinued Original Print

Order correcting transcript of record.............. -............. 99 62

Transcript of proceedings, June 25, 1951...................... 105 63

Caption ....................................................................... 106 63

Colloquy between Court and counsel...................... 107 63

Offers in evidence ..................................................... 108 64

Testimony of Arthur H. Saville . . . ........................ 115 68

Kenneth McFarland ............................ 121 72

Lena Mae C arper.................................. 136 81

Katherine Carper ................................ 141 85

Oliver L. Brown .................................... 145 88

Darlene Watson .................................... 155 94

Alma Jean Galloway ............................ 158 96

Sadie Emanuel ...................................... 160 97

Shirley Mae H odison ............................ 164 100

James Y. Richardson............................ 167 102

Lucinda Todd ........................................ 169 103

Marguerite Emmerson ........................ 171 104

Zelma H enderson.................................. 173 105

Silas Hardwick F lem ing...................... 176 107

Hugh W. Speer.................................. 182 111

James H. Buchanan.......................... 233 143

R. S. B. English.................................... 248 153

Wilbur B. Brookover............................ 263 162

Louisa H o l t ................................... 272 168

John J. Kane ........................................ 283 175

Bettie Belk ............................................ 291 180

Dorothy Crawford ............................ 303 187

Clarence G. Grimes .......................... 309 191

Thelma Mifflin ...................................... 317 196

Kenneth McFarland (Recalled) . . . . 331 205

Ernest M anheim................................ 342 213

Colloquy between court on counsel.......................... 347 216

Opening argument on behalf of plaintiff.............. 349 217

Argument on behalf of defendants........................ 363 225

Closing argument on behalf of plaintiff................ 372 231

Colloquy between Court and counsel.......................... 377 233

Reporter’s certificate.............. (omitted in printing). . 384

Clerk’s certificate...................... (omitted in printing) . . 385

Opinion, Huxman, J .......................................................... 386 238

Findings of fact and conclusions of law............................ 393 244

Deeree ................................................................................. 397 247

Petition for a p p ea l........................................................... 398 248

Assignment of errors and prayer for reversal.............. 400 249

Order allowing appeal ..................................................... 403 251

Citation on appeal.................. (omitted in printing) . . 405

Note re cost bond............................................................... 406 252

Statement required by paragraph 2 rule 12 o f the rules

of the Supreme Court (omitted in printing)............ 407

INDEX 111

Record from U.S.D.C. for the District of Kansas— Con

tinued Original

Praecipe for transcript.......... (omitted in printing) . . 412

Order extending time to file and docket record on ap

peal ................................................................................. 414

Clerk’s certificate.................... (omitted in printing) . . 415

Statement of points to be relied upon and designation of

parts of record to be printed................................................ 416

Order noting probable jurisdiction......................................... 418

Print

253

254

1

[fol. a]

IN UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

DISTRICT OF KANSAS

[Caption omitted]

O liver B r o w n , Mrs. R ichard L a w to n , Mrs. S a m e E m m a n

u e l , Mrs. Lucinda Todd, Mrs. Iona Richardson, Mrs.

Lena Carper, Mrs. Shirley Hodison, Mrs. Alma Lewis,

Mrs. Darlene Brown, Mrs. Shirla Fleming, Mrs. Andrew

Henderson, Mrs. Vivian Scales, Mrs. Marguerite Fmmer-

son, and

L inda Carol B r o w n , an infant, by Oliver Brown, her father

and next friend,

V ictoria J ean L aw ton and Carol K ay L a w to n , infants, by

Mrs. Richard Lawton, their mother and next friend,

J am es M eldon E m m a n u e l , an infant, b y Mrs. Sadie Em

manuel, his mother and next friend,

N an c y J an e T odd, an infant, by Mrs. Lucinda Todd, her

mother and next friend,

R onald D ouglas R ichardson , an infant, b y Mrs. Iona

Richardson, his mother and next friend,

K ath er in e L ouise Carper, an infant, by Mrs. Lena Carper,

her mother and next friend,

C harles H odison, an infant, by Mrs. Shirley Hodison, his

mother and next friend,

[ fo l . b ] T heron L ew is , M arth a J ean L ew is , A r th u r L ew is

and Frances Lewis, infants, by Mrs. Alma Lewis, their

mother and next friend,

S aundria D orstella B r o w n , an infant, b y Mrs. Darlene

Brown, her mother and next friend,

D uane D ean F lem in g and S ilas H abdrick F lem in g , infants,

by Mrs. Shirla Fleming, their mother and next friend,

D onald A ndrew H enderson and V ic k i A n n H enderson ,

infants, by Mrs. Andrew Henderson, their mother and

next friend,

1—8

2

R u t h A n n S cales, an infant, by Mrs. Vivian Scales, her

mother and next friend,

Claude A r t h u r E m m erson and G eorge R obert E m m erso n ,

infants, by Mrs. Marguerite Emmerson, their mother and

next friend, Plaintiffs,

vs.

B oard op E ducation op T opeka , S h a w n e e C o u n t y , K ansas ;

Kenneth McFarland, Superintendent of Schools of

Topeka, Kansas; and Frank Wilson, Principal of Sumner

Elementary School, Defendants,

and

T h e S tate op K ansas, Intervening Defendant

No. T-316 Civil

[fol. 1] A mended C o m plain t— Filed March 22,1951

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, section 1, and the Act of May 31, 1870,

Chapter 114, section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 8, United States

Code, section 41), as hereinafter more fully appears. The

matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and

costs, the sum or value of Three Thousand Dollars

($3000.00).

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1343. This action is

authorized by the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, section

1, 17 Stat. 13 (Title 8, United States Code, section 43), to be

commenced by any citizen of the United States or other

persons within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the depri

vation, under color of a state law, statute, ordinance, regu

lation, custom or usage, or rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, section 1, and by the Act of May 31,

1870, Chapter 114, section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 8, United

States Code, section 41), providing for the equal rights of

citizens and of all other persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States, as hereinafter more fully appears.

3

(c) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 2281. This is an action

for an interlocutory injunction and a permanent injunction

restraining the enforcement, operation and execution of

statutes of the State of Kansas by restraining the action of

defendants, officers of such state, in the enforcement and

execution of such statutes.

2. This is a proceeding for a declaratory judgment and

injunction under Title 28, United States Code, section 2201,

for the purpose of determining questions in actual eontro-

[fol. 2] versy between the parties to wit:

(a) The question of whether the state statute, ch. 72-1724

of the General Statutes of Kansas 1935, is unconstitutional

in that it gives to defendants the power to organize and

maintain separate schools for the education of white and

colored children in the City of Topeka, Kansas.

(b) The question of whether the customs and practices of

the defendants operating under Ch. 72-1724 of the General

Statutes of Kansas, 1935, are unconstitutional in that they

deny infant plaintiffs the rights and privileges of enrolling

in, attending and receiving instruction in public schools of

the district within which they live while such rights and

privileges are granted to white children similarly situated;

where the basis of this refusal and grant is the race and

color of the children, and that alone.

(c) The question of whether the denial to infant plaintiffs,

solely because of race, of educational opportunities equal to

those afforded white children is in contravention of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

as being a denial of the equal protection of the laws.

3. (a) Infant plaintiffs are citizens of the United States,

the State of Kansas, and Shawnee County, the City of

Topeka, Kansas. They are among those classified as

Negroes. They reside within various school districts in the

City of Topeka, satisfy all requirements for admission to

schools within the districts within which they live, have

presented themselves for enrollment and registration at the

proper times and places, and were denied the right to enroll

therein, on account of their race and color. Instead, they

4

are required, solely because of race, to attend schools where

they do not and cannot receive educational advantages, op

portunities and facilities equal to those furnished white

ffol. 3] children.

(b) Adult plaintiffs are citizens of the United States and

the State of Kansas, are residents of and domiciled in

Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, are taxpayers of said

county, of the State of Kansas, and of the United States.

They are the parents and natural guardians of infant

plaintiffs named herein. By being compelled to send their

children to schools outside the districts wherein they live

rather than to schools within said districts, they must bear

certain burdens and forego certain advantages, neither of

which is suffered by parents of white children situated simi

larly to children of plaintiffs.

(c) Plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf and

also on behalf of all citizens similarly situated and affected,

pursuant to Rule 23A of the Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure, there being common questions of law and fact affecting

the rights of all Negro citizens of the United States simi

larly situated who reside in cities in the State of Kansas in

which separate public schools are maintained for white and

Negro children of public school age, and who are so numer

ous as to make it impracticable to bring them all before the

Court.

4. The State of Kansas has declared public education a

state function in the Constitution of the State of Kansas,

Article 6, Sections 1 and 2. Pursuant to this mandate, the

Legislature of Kansas has established a system of free

public schools in the State of Kansas, according to a plan

set out in Chapter 72 of the General Statutes of Kansas,

1935, and supplements thereto. The establishment, mainte

nance, and administration of the public school system of

Kansas is vested in a Superintendent of Public Instruction,

County Superintendent of Schools, and City School Boards.

(Constitution of Kansas, Article 6, section 1.)

[fol. 4] 5. The public schools of Topeka, Shawnee County,

Kansas are under the control and supervision of the de

fendants.

5

(a) Defendant, Board of Education, is under a duty to

enforce the school laws of the State of Kansas

6/22/51 ̂ 1949

amended at (General Statutes of Kansas, 1935, [and sup-

Pre-Trial 72-1724

A.J.M. plements thereto,] # section 72-1809) ; to

maintain an efficient system of public schools

in Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas; to determine the

studies pursued, the methods of teaching, and to establish

such schools as may be necessary to the completeness and

efficiency of the school system. It is an administrative de

partment of the State of Kansas, which discharges govern

mental functions pursuant to the Constitution and the laws

of the State of Kansas. (Constitution of Kansas, Article 6,

sections 1 and 2, General Statutes, 1935, and supplements

thereto of Kansas, section 72-1601). It is declared by law

to be a body corporate and is sued in its governmental

capacity.

(b) Defendant Kenneth McFarland is Superintendent of

Schools, and holds office pursuant to the Constitution and

the laws of the State of Kansas, as an administrative officer

of the free public school system of the State of Kansas. He

has immediate control of the operation of public schools in

Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas. He is sued in his official

capacity.

6. Defendant, Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee

County, Kansas, has established and at the present time

maintains in the City of Topeka, State of Kansas, elemen

tary schools for the education of the school children of the

City of Topeka. They are located within different districts

of the City of Topeka, whose boundaries are designated by

the defendant, Board of Education.

7. White Children of elementary school age go to the

school within the designated boundaries of the district in

which they live.

[fol. 5] Infant plaintiffs live within the boundaries of these

districts, but they are required to leave the districts within

which they live and travel from one and one-half miles to

* Struck out in copy.

6

two miles to separate all-Negro schools, solely because of

their race and color and in violation of their rights under

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

8. The educational opportunities provided by defendants

for infant plaintiffs in the separate all-Negro schools are

inferior to those provided for white school children simi

larly situated in violation of the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

9. Adult plaintiffs are required to send their children

outside the school districts in which they reside to separate

all-Negro schools, whereas parents of white children are

permitted to send their children to schools close at hand

within the district in which they live, solely because of race

and color. Thus adult plaintiffs are being denied the equal

protection of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

10. Infant plaintiffs and adult plaintiffs are thereby

being wilfully and unlawfully discriminated against by the

defendants on account of their race and color, in that infant

plaintiffs are compelled to attend schools outside the school

districts in which they live, while white children similarly

situated are not so compelled; infant plaintiffs and adult

plaintiffs are being deprived of their rights guaranteed by

the Constitution and laws of the United States.

11. Plaintiffs are suffering irreparable injury and face

irreparable injury in the future by reason of the acts herein

complained of. They have no plain, adequate or complete

remedy to redress the wrongs and illegal acts herein com

plained of, other than this suit for a declaration of rights

[fol. 6] and an injunction. Any other remedy to which

plaintiffs might be remitted would be attended by such

uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial relief;

would involve a multiplicity of suits; and would cause fur

ther irreparable injury not only to plaintiffs, but to defend

ants as governmental agencies.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that:

1. The Honorable Court, upon filing of this complaint,

notify the Chief Judge of this Circuit as required by 28

U. 8. C. A., section 2284, so that the Chief Judge may desig

7

nate two other judges to serve as members of a three-judge

court as required by Title 28, U. S. C. A., section 2281, to

hear and determine this action.

2. The Honorable Court enter a judgment or decree

declaring that. the General Statutes of Kansas, 1935,

72-1724, is unconstitutional insofar as it empowers defend

ants to set up separate schools for Negro and white school

children.

3. The Honorable Court enter a judgment or decree de

claring that the policy, custom, usage and practice of de

fendants in operating under Ch. 72-1724, General Statutes

of Kansas, 1935, in denying plaintiffs and other Negro

children residing in Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas,

solely because of race or color, the right and privilege of

enrolling in, attending and receiving instruction in schools

within the district within which they reside as is provided

for white children of like qualifications, are denials of the

equal protection clause of the United States Constitution

and are therefore unconstitutional and void.

4. The Honorable Court issue a permanent injunction

forever restraining and enjoining the defendants from

executing so much of Ch. 72-1724, General Statutes of

Kansas, 1935, as empowers them to set up separate schools

for Negro and white school children.

[fol. 7] 5. The Honorable Court issue a permanent in

junction forever restraining defendants from denying the

Negro school children of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas,

on account of their race or color, the right and privilege of

attending public schools within the district wherein they

live, and from making any distinction based upon race or

color in the opportunities which the defendants provide for

public education.

6. The Honorable Court will allow plaintiffs their costs

herein, reasonable fees for attorneys, and such other and

further relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable

and just.

7. The Honorable Court retain jurisdiction of this cause

after judgment to render such relief as may become neces

sary in the future.

Bledsoe, Scott, Scott & Scott, by Chas. E. Bledsoe,

Charles S. Scott, John J. Scott, Attorneys for

Plaintiffs.

8

Duly sworn to by Charles E. Bledsoe. Jurat omitted in

printing.

[ fo l . 8 ] 1st U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

D efen d an ts ’ M otion for a M ore D e fin ite S tatem en t and

to S trik e :— Filed May 15, 1951

Defendants move the court for an order, as follows:

1. Requiring plaintiffs to amend their amended com

plaint, paragraph 3 (a), last sentence thereof, which reads

as follows: “ Instead, they are required, solely because of

race, to attend schools where they do not and cannot receive

educational advantages, opportunities and facilities equal

to those furnished white children. ’ ’ by making a more defi

nite statement therein setting forth the facts upon which

plaintiffs base their conclusion as to unequal advantages,

opportunities and facilities, for the reason that the present

statement is so vague or ambiguous that defendants cannot

reasonably be required to frame a responsive pleading

thereto.

2. Requiring plaintiffs to amend their amended com

plaint, paragraph 3 (b), last sentence thereof, which reads

as follows:

“ By being compelled to send their children to schools

outside the districts wherein they live rather than to

schools within said districts, they must bear certain

burdens and forego certain advantages, neither of

which is suffered by parents of white children situated

similarly to children of plaintiffs.”

by making a more definite statement therein setting forth

the facts upon which plaintiffs base their conclusion that

adult plaintiffs must bear certain burdens and forego cer

tain benefits; for the reason that the present statement is

so vague and ambiguous that defendants cannot reasonably

be required to frame a responsive pleading thereto.

3. Requiring plaintiffs to strike from their amended com

plaint the following language in paragraph 7 thereof:

“ and in violation of their rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”

9

[fol. 9] for the reason that the same is a conclusion and is

redundant.

4. Requiring plaintiffs to amend the eighth paragraph

of their amended complaint, which reads as follows:

“ The educational opportunities provided by defend

ants for infant plaintiffs in the separate all-Negro

schools are inferior to those provided for white school

children similarly situated in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.”

by making a more definite statement therein setting forth

the facts upon which plaintiffs base their conclusion that

educational opportunities claimed therein are inferior to

those provided for white children; for the reason that the

present statement is so vague and ambiguous that defend

ants cannot reasonably be required to frame a responsive

pleading thereto, and further requiring plaintiffs to strike

from said paragraph 8, the following language:

“ in violation of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.”

for the reason that the same is a conclusion and is re

dundant.

5. Requiring plaintiffs to strike from paragraph 9 of

the amended complaint the last sentence thereof which

reads as follows:

“ Thus adult plaintiffs are being denied the equal pro

tection of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”

for the reason that the same is a conclusion and is re

dundant.

6. By requiring plaintiffs to amend their amended com

plaint by striking all of paragraph 10 thereof, which reads

as follows:

“ Infant plaintiffs and adult plaintiffs are thereby

being wilfully and unlawfully discriminated against by

the defendants on account of their race and color, in

10

that infant plaintiffs are compelled to attend schools

outside the school districts in which they live, while

white children similarly situated are not so compelled;

infant plaintiffs and adult plaintiffs are being deprived

[fol. 10] of their rights guaranteed by the Constitution

and laws of the United States.”

for the reason that the same is a conclusion and is re

dundant.

Lester M. Goodell, George M. Brewster, 401 Colum

bian Building, Topeka, Kansas, Attorneys for

Defendants.

[fol. 11] I n U nited States D istrict Court

D ocket E n try

“ May 25, 1951. At Topeka, before Huxman, Mellott, and

Hill, J J .: Defendants’ Motion for more definite statement

and to Strike denied except as to paragraph 8 which is to

be amended; plaintiffs given five days to amend paragraph

8 and defendants to have five days to plead or ten days to

answer. ’ ’

[ fo l . 12] I n U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

A m e n d m en t to P aragraph E ig h t of t h e A mended

C o m plain t— Filed May 29, 1951

8. The educational opportunities provided by defendants

for infant plaintiffs in the separate all-Negro schools are

inferior to those provided for white school children simi

larly situated in violation of the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. The respects in which these opportunities

are inferior include the physical facilities, curricula, teach

ing, resources, student personnel services, access and all

other educational factors, tangible and intangible, offered

to school children in Topeka. Apart from all other factors,

the racial segregation herein practiced in and of itself con

stitutes an inferiority in educational opportunity offered

11

to Negroes, when compared to educational opportunity

offered to whites.

Bledsoe, Scott, Scott & Scott, by Chas. E. Bledsoe.

Duly sworn to by Charles E. Bledsoe. Jurat omitted in

printing.

[ fo l . 13] I n U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

A nsw er of D efendants to A mended C o m plain t as

A mended in P aragraph 8 T hereof—Filed June 7, 1951

1. Defendants admit the allegations stated in paragraphs

4 and 6 of the Amended Complaint, except that defendants

allege that the City of Topeka is one school district, as

hereinafter set forth. Defendants deny all the allegations

stated in Amendments to paragraph 8 of the Amended

Complaint, and further deny all the allegations stated in

paragraphs 9, 10 and 11 of the Amended Complaint.

2. Defendants admit the allegations stated in paragraph

1 (a) of the Amended Complaint, except defendants deny

that the amount in controversy, exclusive of interest and

costs, exceeds $3,000.00.

3. Defendants admit the allegations stated in paragraph

2, except defendants deny that infant plaintiffs are denied

rights and privileges of enrolling in, attending and receiv

ing instruction in public schools within the district in which

they live; and deny that they have denied infant plaintiffs

educational opportunities equal to those afforded white

children.

4. Defendants allege that the City of Topeka, Kansas,

is in and of itself one school district; that acting pursuant

to authority vested in it, defendants have designated and

defined 22 separate territories within the City of Topeka

and in each of said territories have established and main

tain a public elementary school, and white children are

required to attend the elementary school located in the

territory in which they live; that defendants have also

established and maintain four separate elementary schools

for colored children within said district, and only colored

children in the City of Topeka may attend said four schools,

[fol. 14] Defendants further allege that the colored school

12

children, including infant plaintiffs, may attend any one of

these four schools.

5. Defendants allege that said separate schools are estab

lished and maintained pursuant to the laws of the State of

Kansas, G. S. 1949, 72-1724, and separate schools are pro

vided only for elementary school children, to-wit, the first

six grades.

6. Defendants allege that they have established and main

tain junior high schools throughout the City of Topeka and

have designated and defined territories for each of said

schools; that both colored and white children may attend

these schools and are required to attend the jiinior high

school located within the territory in which they live.

7. Defendants allege that transportation facilities are

provided for colored school children attending the four

colored schools mentioned in paragraph 4 hereof, and said

transportation facilities are furnished any colored school

child attending elementary schools, upon request; that no

transportation is furnished white children by the defend

ants.

8. Defendants admit the allegations stated in paragraph

3 (b) that adult plaintiffs are citizens of the United States,

the State of Kansas, Shawnee County and the City of

Topeka, Kansas, and deny the remainder of said paragraph.

Defendants further deny that adult plaintiffs are compelled

to send their children to schools outside the district wherein

they live.

9. Defendants admit the allegations stated in paragraph

3 (a) that infant plaintiffs are citizens of the United States,

State of Kansas, Shawnee County and the City of Topeka,

Kansas, and that they are among those classified as negroes,

[fol. 15] Defendants allege that infant plaintiffs have pre

sented themselves for enrollment and registration in ele

mentary schools for white children but were denied the

right to enroll therein. Defendants allege that infant plain

tiffs, because of race and color, do not satisfy the require

ments for admission to schools for white children and by

reason thereof they were denied admission. Defendants

deny the remainder of paragraph 3 (a).

10. Defendants allege that they are without knowledge

or information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of

the allegations stated in paragraph 3 (c) of the Amended

13

Complaint, or that adult plaintiffs are taxpayers of

Shawnee County, the State of Kansas, and the United

States, as stated in paragraph 3 (b).

11. Defendants admit the allegations stated in para

graph 5 of the Amended Complaint, but deny that they are

governed by General Statutes 1935, and supplements

thereto, section 72-1809, for the reason that said statute

applies to public schools in cities of the second class and not

to public schools in cities of the first class to which class

the City of Topeka belongs.

12. Defendants deny the allegations stated in paragraph

7 of the Amended Complaint, and allege that white school

children of elementary school age in the City of Topeka are

required to go to the elementary schools within the desig

nated boundaries of the territory in which they live, and

that these schools are within the school district of the City

of Topeka; that infant plaintiffs go to elementary schools

within the district in which they live, namely, the school dis

trict of the City of Topeka, Kansas, and they may attend

any of the colored elementary schools within the City of

Topeka, as set forth in paragraph 4 hereof. Defendants

further allege that the distance traveled by colored children

[fol. 16] in reaching the schools they attend is not on the

average greater than the distance white children are re

quired to travel.

Wherefore, Defendants pray that plaintiffs take naught;

and that defendants have judgment and costs.

Lester M. Goodell, George M. Brewster, Topeka,

Kansas, Attorneys for Defendants.

Duly sworn to by Lester M. Goodell. Jural omitted in

printing.

[fol. 17] [File endorsement omitted]

In U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

[Title omitted]

S eparate A n sw er of t h e S tate of K ansas— Filed June

15, 1951

Comes now the State of Kansas, an intervening defend

ant, by Edward F. Arn, Governor of said State, and Har

old E. Fatzer, the Attorney General thereof, and for its

answer to the amended complaint herein alleges as follows:

I

That the amended complaint in said cause fails to state

a claim or cause of action against this intervening defend

ant upon which relief may be granted to the plaintiffs.

II

This intervening defendant admits the allegations con

tained in paragraph 1 of the amended complaint except

that it denies the amount in controversy exceeds, exclu

sive of interest and costs, the sum or value of $3,000.00.

III

This intervening defendant admits the allegations con

tained in paragraph 2 (a) of the amended complaint ex

cept that it expressly denies Chapter 72-1724 of the Gen

eral Statutes of Kansas, 1935 (1949), is unconstitutional.

This defendant is without knowledge or information to

either admit or deny the truth or the allegations contained

in paragraph 2 (b), (c), and paragraph 3 (a), (b) of the

amended complaint.

[fol. 18] IV

This defendant admits the allegations contained in para

graphs 4 and 5 of the amended complaint, but denies that

the defendant, Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee

County, Kansas, is governed by the General Statutes of

Kansas, 1935, and supplements thereto, Section 72-1809,

for the reason that said statute has no application to pub-

14

15

lie schools in cities of the first class to which class the

city of Topeka belongs.

V

For further answer herein this intervening defendant

states it is without knowledge or information to either

admit or deny the truth of the allegations contained in

paragraphs 6, 7, 8 as amended, 9 or 10 of the amended com

plaint. All other allegations contained in the amended

complaint which are not hereinbefore admitted or ex

plained are hereby expressly denied.

Wherefore this intervening defendant prays that plain

tiffs take naught by this action and that defendants have

judgment for all costs herein expended.

Harold R, Fatzer, Attorney General for the State

of Kansas; Willis H. McQueary, Assistant Attor

ney General for the State of Kansas; C. Harold

Hughes, Assistant Attorney General of the State

of Kansas.

[Verified by Willis H. McQueary.]

[ fo l . 19] In U niTEo S tates D istrict C ourt

[Title omitted]

Transcript of Proceedings of Pre-Trial Conference—Filed

October 30,1951

APPEARANCES :

Hon. Walter A. Huxman, Judge, United States Court

of Appeals, Tenth Circuit,

Hon. Arthur J. Mellott, Judge, United States District

Court, District of Kansas.

Charles S. Scott, Topeka, Kansas; John Scott, Topeka,

Kansas; Charles Bledsoe, Topeka, Kansas; Robert L. Car

ter, New York, New York, and Jack Greenberg, New York,

New York. Appeared on behalf of Plaintiffs.

Lester M. Goodell, Topeka, Kansas, and George M.

Brewster, Topeka, Kansas. Appeared on behalf of De

16

fendants, Board of Education, Topeka, Shawnee County,

Kansas, et al.

Harold R. Fatzer, Attorney General, State of Kansas,

by Willis H. McQueary and Charles H. Hobart, Assistant

Attorneys General, State of Kansas, Topeka, Kansas. Ap

peared on behalf of State of Kansas.

Harold Pittell, Official Reporter.

[fol. 20] Be it remembered, on this 22nd day of June,

A.D. 1951, the above matter coming on for hearing before

Honorable Walter A. Huxman, .Judge, United States Court

of Appeals, Tenth Circuit and Honorable Arthur J. Mellott,

Judge, United States District Court, District of Kansas,

and the parties appearing in person and/or by counsel, as

hereinabove set forth, the following proceedings were had:

̂ ̂ ̂ ̂ •if*

[ fo l . 21] C olloquy B etw een C ourt and C ounsel

Judge Mellott: Do you have the appearances, Mr. Re

porter?

The Reporter : Yes, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: Gentlemen, the purpose of this session

this morning is to hold a pre-trial conference to see whether

we can simplify the matters and what can be agreed to

before we go to trial next Monday.

Judge Mellott has called my attention to Rule 16. It

provides for conference to simplify the issues, whether

there is any necessity for amendments to the pleadings

and to inquire into the possibility of obtaining admissions

of fact concerning which there can be no dispute, limita

tion of the number of expert witnesses, the advisability

of a preliminary reference of the issues to a master for

findings and any such other matters as may simplify the

issues at the time of the trial.

All the parties have entered—are in court and have

filed pleadings; that is true of the State of Kansas, is it

not?

Mr. McQueary: It is, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: Is there a desire on the part of any

body to amend the pleadings in any manner; any necessity

for amendment of pleadings?

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes, if the Court please. We have

one amendment we desire to make.

[fol. 22] Judge Mellott: To what paragraph?

Mr. Charles Scott: Paragraph 5, sub-paragraph (a)

of the plaintiffs’ amended complaint.

Mr. Goodell: What was that again?

Mr. Charles Scott: Paragraph 5, sub-paragraph (a).

Judge Huxman: Paragraph 5 what?

Mr. Charles Scott: Paragraph 5(a).

Judge Mellott: Let me orient myself and Judge Hux

man. Did you file a complete amended complaint?

Mr. Charles Scott: No, sir.

Judge Mellott: You filed an original complaint.

Mr. Charles Scott: And an amended complaint and------

Judge Mellott : And then in the amended complaint—

there was an amendment to the amended complaint.

Mr. Goodell: I interpret that they did file——

Judge Mellott: You did file an amended complaint on

March 22nd, didn’t you?

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes.

Judge Mellott: The motion to make more definite was

addressed to that amended complaint.

[fol. 23] Mr. Charles Scott: That is correct.

Judge Mellott: And then you filed an amendment to

the amended complaint, under date of May 29th, did you

not?

Mr. Charles Scott: That is correct, sir.

Judge Huxman: What do you desire presently?

Mr. Charles Scott: We desire to correct the statute of

72-1809 of the General Statutes of 1935 and the supple

ments thereto.

Judge Mellott: Let me get this in the pleading here.

You are now talking about your original amended com

plaint, aren’t you?

Mr. Charles Scott: The original amended complaint.

Judge Mellott: And you say you want to refer to para

graph 5 of that.

Mr. Charles Scott: 5(a).

Judge Mellott: 5(a). Your amendment is what; you

want to make reference to the General Statutes of ’49 in

stead of 1935, is that what you are saying?

2—8

17

18

Mr. Charles Scott: We also want to make reference to

the General Statutes of 1949 and also strike therefrom Sec

tion 72-1809 and insert therein 72-1724.

Judge Mellott: 72-1724.

Mr. Charles Scott: That is correct.

[fol. 24] Judge Mellott: And does that read, then, that

that is the General Statutes of Kansas for 1949?

Mr. Charles Scott: That is correct.

Judge Mellott: You wish to leave out the words, “ and

supplements thereto.”

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes, we can take that out, that’s true.

Judge Mellott: Let me see if I understand what you are

doing. Paragraph 5(a), as amended, now reads: “ De

fendant, Board of Education, is under a duty to enforce

the school laws of the State of Kansas (General Statutes

of Kansas, 1949, Section 72-1724) ” , is that the amendment

you are making ?

Mr. Charles Scott: That is correct, sir.

Judge Mellott: Any other amendments!

Mr. Charles Scott: That is all we have.

Judge Huxman: Any objections to that? No objections;

the amendment will be------

Mr. Goodell: If I understand his point, he cited in his

amended complaint, which he now desires to correct, a

statute which applies to cities of second class, erroneously

when he intended to use—so we have no objection.

Judge Huxman: All right; the amendment will be ordered.

Judge Mellott: The Court will make the amendment by

[fol. 25] interlineation.

Judge Huxman: Any other amendment to the pleadings?

Mr. Goodell: We have none, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: No further amendments to any of the

pleadings.

Mr. Bledsoe: If the Court please, at this time I would

like to inform the Court we have two attorneys who are

interested in this case with the plaintiffs, and they are

here now, and I would like to present them to the Court

at this time.

Judge Huxman: I will ask Judge Mellott to handle that

because he knows how that matter is handled.

Judge Mellott: Very well. You may introduce them, if

you will, and tell me who they are.

19

Mr. Bledsoe: They would like to be admitted for the

purpose of this case only.

Judge Mellott: Present them.

Mr. Bledsoe: If the Court please, this gentleman! here is

Robert Carter, from New York. This, gentlemen, is Judge

Huxman of the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals; the gentle

man over here is Jack Greenberg, of New York, and this is

Judge Mellott of the District of Kansas Federal Court.

Judge Mellott: Are these gentlemen members of the bar?

[fob 26] Mr. Bledsoe: They are.

Judge Mellott: In what state!

Mr. Bledsoe: New York.

Judge Mellott: In good standing?

Mr. Bledsoe: They are.

Judge Mellott: And are they admitted to practice in

federal courts and courts such as this in their home jurisdic

tion ?

Mr. Bledsoe: They are.

Judge Mellott: Never been disbarred. You vouch for

them.

Mr. Bledsoe: I do.

Judge Mellott: Without further formality, then, they

will be permitted to appear as counsel, along with the other

gentlemen who presently appear as counsel in this case.

Thank you, gentlemen; you may be seated.

Judge Huxman: Unless there is something else pre

liminary, we might------

Mr. Carter: Your Honor, if I may, I would like to raise

one point. I don’t think an amendment would be necessary

to our pleadings, but we erroneously refer to school dis

tricts in Topeka, where it should be “ territories” , and, we

were going to make a stipulation with the defendants that

they are territories rather than districts—and there is one

school district.

[fol. 27] Judge Huxman: I think that is covered.

Mr. Carter: I just want to be sure.

Judge Mellott: I suppose, if necessary, for all proper

purposes in this case, the Court can consider that where

you use the word “ district” in your pleading, that really

what you are referring to is “ territories.” I believe I sug

gested that at an earlier proceeding here. It -was my under

2 0

standing Topeka was one school district, so you were re

ferring to territories.

Judge Hnxman: There is one other matter that might

come up during the trial—at least I think the Court might

want to make inquiry—will either or any of the parties to

this litigation want to use expert witnesses?

Mr. Carter: Well, Your Honor------

Judge Huxman: For what purpose?

Mr. Carter: We want to use expert witnesses for the

general purpose of showing that the segregation, which is

the- issue in the case, the segregation of the plaintiffs and

of the class they represent in the negro schools is in fact a

denial to them of their right to equal educational oppor

tunities, that they are not getting equal educational

opportunities by virtue of that. That is the purpose of

our expert testimony.

Judge Huxman: Will there be any opposition to expert

witnesses?

[fol. 28] Mr. Goodeh: The------

Judge Huxman: —the use of expert witnesses by the

plaintiffs?

Mr. Groodell: The way the question was stated, we will

certainly object to that. We think that is a question of law.

I, of course, don’t know what turn it will take.

Judge Huxman: Well, the question of whether such testi

mony is competent, does not need to be decided at this time.

The purpose of this inquiry is to ascertain how many such

witnesses you will request and whether there shall be a

limit. How many witnesses do you gentlemen desire on

that question, assuming that the Court rules it is competent.

Mr. Carter: Well, Your Honor, I think that we were not

certain of the exact number but approximately nine. We

have approximately nine or ten people who we want to call

who have made studies of this.

Judge Huxman: Well, the Court feels that nine witnesses

on that one issue is too: many witnesses. In other words,

the issue is whether segregation itself, I presume, is not a

denial of due process, irrespective of whether everything

else is equal, to that furnished in. the white schools, is that

not your general contention?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: Because of the effect it has upon the

21

[fol. 29] mind, upon the student, upon his outlook; I pre

sume that would be your position.

Mr. Carter: That is absolutely correct, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: Could nine witnesses give different testi

mony, or would their testimony be largely the same?

Mr. Carter: I doubt that, Your Honor. Our testimony

will not be cumulative. Our purpose of getting these people

was in order to give a rounded picture with respect to the

subject that we have just raised. Now, we will have some

witnesses who will testify as to tangible and physical

inequalities also among those people, so that I think that

it would be a great hardship to us if wTe were limited.

We have no intention of merely bringing on witnesses to

be cumulative.

Judge Mellott: That is the thing the Court thinks it should

avoid. We shouldn’t hear nine witnesses testify cumula

tively even as experts, it seems to me, on the same thing.

Mr. Carter: I agree, but, Your Honor, we have no—we

are not going to have duplication. Each of the people that

we are asking to come here to testify will handle a different

phase of this.

Judge Mellott: Then we should not limit you if that is

what you expect to do.

[fol. 30] Judge Huxman: The Court feels this way, that

it ’s difficult for it at this time to see where nine witnesses

could testify on this one subject, to nine different sets of

facts, unrelated facts, but you may be right; we do not

intend to deny you the right to fully present your ease. The

Court, however, feels that after it has heard five witnesses,

expert witnesses, if the Court then feels that the witnesses

that you are offering thereafter are merely duplicating what

has been said, an objection to their testimony on that ground

will be sustained. If, on the other hand, the testimony is

clearly different from what has been given, why you then

should have the right to present your nine witnesses. But

at the end of five, the Court will certainly scrutinize the

testimony of the other four quite carefully to see whether

it is duplication or additional testimony.

Mr. Carter: All right, sir.

Judge Huxman: Do you gentlemen then stipulate that,

in any event, the expert witnesses which you request will be

limited in number to nine.

22

Mr. Carter: Your Honor, frankly, our difficulty in making

any stipulation like that is that Mr. Greenberg and I have

just gotten here from New York this morning about------

Judge Huxman: This isn’t the first case of this kind you

were in. You were in the South Carolina case, weren’t

[fol. 31] you?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir; but the thing is we haven’t really

had an opportunity to go over this.. I would not want to

make that stipulation. What I will say and what Your

Honor has ruled is that after five, you will scrutinize what

ever testimony we present for duplication, and we will

certainly attempt to avoid that, but I wouldn’t want to say

that we would only have nine.

Judge Huxman: That was your statement in response.

_ Mr. Carter: I said approximately; I didn’t want to be

tied down to that number at all.

Judge Mellott: How much leeway do you want ?

Mr. Carter: Well, I frankly think that we won’t have

more than nine, but I just would prefer not to be tied down.

I am not going to, believe me, Your Honor, we are not going

to parade a lot of witnesses here merely to keep you tied

down.

Mr. Goodell: It would be under ninety, wouldn’t it?

Mr. Carter: It will be under fifteen.

Mr. Goodell: Nine to ninety.

Judge Huxman: It would be the order of the Court that

expert witnesses on behalf of the plaintiff, in the first

[fol. 32] instance, will be limited to five, but if at that

point the plaintiffs have additional witnesses which they

feel have testimony to offer which has not been covered by

these five, they will not be denied the right to present that

testimony, is that correct, judge?

Judge Mellott : Yes, at this time, I think.

Judge Huxman: But that after five have been heard,

the Court will reserve the right to reject any further evi

dence if it should feel that the evidence that is being offered

is cumulative and not additional to what the first five have

testified, is that fair to you boys ?

In view of the fact that there has been a statement that

plaintiffs will offer expert witnesses on this subject,

assuming that the testimony will be received, will the de

23

fendants, or any of them, want to on their part offer expert

testimony along this same line!

Mr. Goodell: Well, I am a little at a handicap of know

ing exactly what their line is. They mention there is to be

testimony from experts, as I understood it, on some physical

facts which, of course, I don’t know what they are referring*

to except I take it to mean that inferiority to—as to some

—something relating to the school system and, of course,

if that comes up, we will probably want to rebut that, not

with experts, I don’t think.

[fob 33J Judge Huxman: Judge Mellott-----

Mr. Goodell: As to the other phase which I understand

is the psychological aspect and sociological, until I have

heard their testimony, I am at a loss to know whether we

will want to rebut it or attempt to rebut it.

Judge Mellott: Well, would it not be proper if the Court

thought in terms of the same basic premise that in the event

you do decide to offer experts rebutting the testimony of

the plaintiffs’ experts, that a limitation somewhat along the

line suggested by Judge Huxman to the plaintiff should,

likewise, apply to you.

Mr. Goodell: I certainly think so.

Judge Huxman: All right; that will be the order of the

Court at this time.

Now, is there anything else, gentlemen, as to preliminary

matters that we want to discuss before we go into these

requests for admissions. Anything else that might be help

ful in shaping the issues, shortening this trial.

I may state for myself, as a member of this court, that it

would certainly be my purpose to afford the parties a full

and complete hearing and an opportunity to present the

issues fully and completely but, on the other hand, I would

be very loathe to just permit the introduction of a great

mass of testimony for any purpose whatever that has no

bearing upon the issues; it merely prolongs and drags out

[fol. 34] this trial.

Anything else preliminary? Do you care to say anything

more?

Judge Mellott: I am quite sure Judge Hill and I concur

entirely as to what you have just said, though my authority,

of course, to speak is only to speak for myself.

Judge Huxman: In a preliminary conference, Judge

24

Mellott, to bring yon np to date, purely informal, with attor

neys for the plaintiffs and the defendants, I suggested that,

as a preliminary to this pre-trial conference, each side pre

pare requested admissions of fact and serve them on the

other side.

Judge Mellott: I am sure that was quite helpful.

Judge Huxman: We have that here this morning and,

if there is nothing further, suppose, gentlemen, we proceed

to see how many of these requests we can agree upon.

We will take up the defendants’ requests for stipulations

first.

No. 1 is a request for an agreement that the City of

Topeka, Kansas, constitutes one school district.

Mr. Carter: We agree.

Judge Huxman: That is agreed to.

Judge Mellott: Thank you, gentlemen.

[fol. 35] Judge Huxman: Request No. 2:

“ That defendants have designated within the City of

Topeka, Kansas, eighteen territories and in each of these

territories have established and maintain a public elemen

tary school for white children only; in addition thereto

defendants have established and maintain in the City of

Topeka, Kansas, four separate elementary schools for

colored children and attendance at these four schools is

restricted to colored children. Exhibit A, which is made

a part hereof by reference, is a map of the City of Topeka

and adjacent territories attached to Topeka School District

for school purposes only. Said Exhibit A correctly desig

nates the school territory for white schools for the City

of Topeka, Kansas. Said map also designates the four

colored schools, which are Buchanan, McKinley, Monroe

and Washington. Colored school children in the City of

Topeka, Kansas, may attend any one of these four colored

schools, and the choice of schools is made by the colored

school children or their parents. The territory colored blue

on Exhibit A represents areas not within the City of Topeka

except for school purposes, and children residing in said

areas attend schools in the City of Topeka, Kansas.”

Now, before you make any request, Judge Mellott has

not seen Exhibit “ A ” . As a preliminary question, may

I ask, Mr. Goodell, who prepared that exhibit!

25

[fol. 36] Mr. Goodell: The clerk of the Topeka Board of

Education.

Judge Huxman: Do you vouch for its territorial correct

ness and integrity?

Mr. Goodell: Absolutely.

Judge Huxman: All right. With that preliminary state

ment, is there any objection to the admission requested in

request No. 2?

Mr. Carter: Well, Your Honor, this is the first—I think

we have no objection on Exhibit “ A ” , but going over on to

page 2—about the fifth line from the top------

Judge Huxman: Fifth line from the top on page 2.

Mr. Carter: ‘ ‘ and the choice of schools is made by the

colored school children or their parents.” I should think

we have to get more information on that before we could

agree. With that exception, we will agree.

Mr. Goodell: For clarity, what is meant there, of course,

is choice of which of the four colored schools. It doesn’t

mean to say------

Mr. Carter: It is a question in our minds as to whether

that is true.

Judge Huxman: Do you have testimony to the effect

that that is not true?

Mr. Carter: We may.

[fol. 37] Judge Huxman: You may.

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: Well, do you have reasons to believe

that it is not true?

Mr. Carter: Well, the only thing I can say at this time,

Your Honor, is that up to—as far as this is concerned, we

have to know—we would have to make a little further in

vestigation on this ourselves. We might stipulate, agree,

that this is true by Monday, but I don’t think we can do it

today.

Judge Huxman: All right, I just feel this way, that

there ought to be a perfect willingness on the part of both

parties to freely and frankly agree to facts concerning

which there just can’t be any dispute. Now, if there is a

question about a fact, that should not be agreed to, of

course, but you have local colored counsel here who no

doubt went to schools here, these segregated schools.

26

Mr. Carter: That is------

Judge Huxman: Do you agree to the request with the

exception of that portion starting—with this exception:

“ Colored school children in the City of Topeka, Kansas,

may attend any one of these four colored schools, and the

choice of schools is made by the colored school children or

their parents.”

Mr. Carter: All we reject is of the choice.

[fol. 38] Judge Huxman: Do you agree to everything

but that!

Mr. Carter: We agree with the first part of the state

ment. All we don’t know about is the choice.

Judge Huxman: I am just taking the one sentence. I

don’t like to divide a sentence. You want to reserve the

agreement to that until Monday.

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: And, in the meantime, you will make

an investigation and if you find that that is a fact------

Mr. Carter: We will agree to it.

Judge Huxman: Mr. Scott, you have been a resident of

Topeka all your life.

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: Are you able to say whether that is or

is not a fact as the schools are administered.

Mr. Charles Scott: Qualified, Your Honor. We are al

lowed to go to the schools that are closest to our home.

Now*, whether or not the school board has any control over

that or not, I don’t know, but, as a practical matter, natu

rally, the colored students go to the school closest to their

home.

Judge Huxman: I tell you what I wish you would do with

your New York counsel. I wish you would have a confer-

[fol. 39] ence with the members of the school board between

now and Monday and ask them if a colored student wants

to attend any one of these four schools whether there is

any restriction upon his right to do so.

Mr. Charles Scott: I will do that, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: And then come in Monday morning------

Mr. Coodell: Of course, my information came from the

board and the administrative officers on all these matters.

Judge Huxman: They should have the right to get that

information themselves.

27

It is agreed, then, that request for admission No. 2 is

argeed to with the exception of that portion which has just

been read by the Court and, as to that portion, inquiry will

be made by Monday and a statement by counsel for plain

tiffs will be made then as to whether they agree to that por

tion which is presently eliminated.

We will take up No. 3:

“ That the same curriculum is used in the elementary

colored schools in the City of Topeka, Kansas, as is used

in the elementary white schools in said city. ’ ’

Mr. Carter: After conference, Your Honor, we cannot

stipulate to that.

[fol. 40] Judge Huxman: Do you claim that that is not so?

Mr. Carter: We would change in the first sentence where

it reads, “ That the same curricula is used” , we would

change that to “ prescribed” as long as curricula is under

stood to mean courses of study.

Judge Huxman: That is what the curricula means, isn’t

it, courses of study.

Mr. Gfoodell: That is what I intended by it.

Mr. Carter: I am not sure.

Judge Huxman: Do you have a different meaning of

curricula ?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: Is there any objection to the elimination

of the word “ curricula” and the substitution of the

“ studies are used” ?

Mr. Carter: “ Prescribed” is what we want to use.

Judge Huxman: That wouldn’t be any admission. The

question is, is it actually used, that is the test.

Mr. Carter: We are advised that that is not true, Your

Honor.

Judg*e Huxman: How?

[fol. 41] Mr. Carter: We at this table don’t feel that we

can stipulate to that at this time.

Judge Huxman: Well, do you intend to offer evidence

to show that that is not so?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: In what respect do you contend that

there is a difference?

Mr. Carter: Well, there are several things that I have

28

right now at my fingertips that I can indicate. One is that

there is a difference in terms of the special teachers and

the special—there are special teachers that are used at the

White schools. No special teachers or special courses for

certain classes of the student body are at the Negro School.

Judge Huxman: The teachers have nothing to do with

the courses of study?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir. They have set up, as we under

stand it, Your Honor, set up at the White school a special

course of study for children who are somewhat retarded

who are not able to come up to the part of their class. Now,

no such course is available at the Negro school. We also

have a question right now as to whether even though the

same courses of study are prescribed, and we think that

we have evidence to show that it is not used, that this is

not followed out at the Negro school generally.

[fol. 42] Judge Huxman: Mr. Goodell, what do you say

with regard to the statement that special courses prescribed

in white schools for sub-normal children are not in colored

schools?

Mr. Goodell: I don’t think that is curricula that is special

—that comes under a heading later in our brief about spe

cial services which they cover in paragraph 8, which I don’t

think is embraced in the question of curricula.

Judge Mellott: I am wondering if you gentlemen perhaps

are in dispute primarily about the definition of the word

‘ ‘ curricula. ’ ’ I wonder if that is your difficulty.

Mr. Goodell: I think—my interpretation of it and the

use I intended is the—as meaning the subjects taught, pro

grams used in the school and the subjects taught, courses

of study.

Judge Mellott : Well, do you wish to rephrase it so that

it does limit it to those particular terms? Maybe your

adversary will agree if you rephrase it.

Mr. Goodell: I am willing to change it, Your Honor, by

striking out the word “ curricula” and substituting there

for “ that the same course of study” —“ courses of study” .

Judge Mellott: I suggest that counsel for the plaintiff

give attention to what is being said.

[fol. 43] Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: He is suggesting that perhaps a change

in the word “ curricula” might make this understandable

29

so you do agree upon its meaning and perhaps get closer

to a stipulation.

Mr. Goodell: “ That the same course of study is used

in the elementary colored schools in the City of Topeka as

is used in the elementary white schools.” It will read,

Your Honor, my suggested amendment.

Judge Huy man: Also keep in mind, gentlemen, that

under Mr. Goodell’s explanation this special matter which

you mentioned for abnormal children is not meant to be

included in here, and the agreement to this stipulation

would not bar you from showing that some special services

are rendered to white children that are not rendered to

colored children. With that statement, are you willing to

agree with this ?

Mr. Charles Scott: At this time, Your Honor, I don’t

think we are inclined to accept it.

Judge Mellott: Your associates think they are. They

say if you limit it to simply saying that the same course

of study is used, that they don’t have any objection.

Mr. Charles Scott: Well, this is the reason, Your Honor:

We have examined a greater portion of the curricula, as

prescribed by the school board, and we have found that

[fob 44] there are some differences, certain course of

studies are offered in some schools and are not offered in

some of the colored schools, and so I don’t think we are in

clined to accept it on those basis.

Judge Huxman: Can you name a specific instance?

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: All right, let’s have it.

Mr. Charles Scott: They have a course entitled “ Litera

ture Appreciation” that is offered in the fifth and sixth

grades in several of the white schools, and it is not offered

in one or two of the colored schools. Then you have------

Judge Huxman: Is that shown by the exhibits ?

Mr. Charles Scott: Yes, sir.

Judge Huxman: All right. What would you say to this:

Would you agree that the courses of study as outlined in

these exhibits—what are the exhibits?

Mr. Charles Scott: If the Court please, now they

label------

Judge Huxman: Are the courses of studies that are used.

30

Mr. Charles Scott: They call it the school program, but it

appears to be the course of study.

[fol. 45] Judge Huxman: That is quibbling about words,

isn’t it?

Mr. Charles Scott: Well------

Mr. Goodell: I am willing to limit that again. I am not

familiar with that matter he points out—to have it read,

“ That the same course of study required by the Kansas” —

by law—“ by the Kansas statute is given.” I think what

he is talking about is some extra-curricular subject that

some teachers of their own volition give, like outside read

ing, reference texts, and so forth, rather than a prescribed

course of study.

Mr. Charles Scott: No, I beg to differ with counsel. This

is prescribed by the school board and sent down.

Mr. Goodell: I am talking about what the state law re

quires to be taught in our Kansas elementary public school

system.

(Colloquy was here had between counsel off the record.)

Mr. Goodell: If we are going to have a lawsuit here and

pursue factual inquiry as to—as to school by school, of

which there are twenty-two, we will be chasing down each

textbook for outside reading that Miss Jones may pre

scribe at Randolph which Miss Baker at another school

doesn’t like, and she prescribes another text for outside

[fol. 46] reading. Suppose they are taking history; one

likes this for outside reading and another teacher likes

another. That will frequently occur.

Judge Mellott: Do you have a printed course of study?

Mr. Goodell: Absolutely.

Judge Mellott: Do you have one?

Mr. Goodell: I have it attached as an exhibit here. And

what I meant to convey and what I mean by this stipula

tion and will reframe it------

Judge Mellott: Where is it attached?

Mr. Brewster: Exhibit “ F ” .

Mr. Goodell: That the course of study required by our

Kansas statute is followed in all of the schools without any

distinction between the white and colored elementary

schools.

31

(Colloquy was here had between counsel off the record.)

Judge Huxman: Shall we then eliminate request No. 3?

Mr. Goodell: Let’s pass that, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: We will pass request No. 3 and take up

No. 4:

“ That the same school hooks are used in the elementary

colored schools in the City of Topeka, Kansas, as are used in

[fol. 47] the elementary white schools in said city.”

Is that not related to 3 and also covered by your exhibits ?

Mr. Goodell: Yes.

Judge Huxman: Shall we pass it?

Mr. Goodell: Yes, that is satisfactory.

Mr. Carter: Your Honor, we are having one of our

expert witnesses, that is going to be a librarian, who is at

the present time checking the holdings of all the schools.

Judge Huxman: Is what?

Mr. Carter: The holdings, the library holdings of all of

the schools, and we therefore are not—we can’t------

Judge Huxman: We passed 4.

Mr. Goodell: I would like to amend, in view of his re

marks, I would like to amend that to read, ‘ ‘ The same text

books” —“ school textbooks” —so that it doesn’t------

Judge Huxman: All right, that will be permitted.

Judge Mellott: Do you agree that the same textbooks are

used ?

Mr. Carter: I think we will agree.

Judge Mellott: Very well.

Judge Huxman: Did you, Mr. Reporter, get request No.

[fol. 48] 4, as amended?

The Reporter: Yes, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: We will take No. 5:

“ That each of the four colored elementary schools in the

City of Topeka, Kansas, is situated in neighborhoods where

the population is predominantly colored. ”

Mr. John Scott: That is agreeable, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: That is agreed to.

Judge Huxman: No. 6:

“ That transportation to and from school is furnished

colored children in the elementary schools of the City of

32

Topeka, Kansas, without cost to said children or their

parents. No such transportation is furnished white chil

dren in the elementary schools of the City of Topeka.”

It would seem to me that is either a fact or isn’t a fact.

Mr. Charles Scott: We will agree to that.

Judge Huxman: All right. No. 6 is agreed to.

No. 7:

“ That the same services are offered to colored and white

elementary schools by the school authorities of the City of

Topeka, Kansas, except in the case of transportation, as

[fol. 49] set out in the preceding paragraph hereof.”

Now, before you speak on that, I would like to ask a pre

liminary question: I am not sure that I understand, Mr.

Goodell, what you mean by the “ same services.”

Mr. Goddell: I mean services like supervised play of the

children at recess and noon period; I mean services of pub

lic health, nursing, which is furnished the elementary

schools, both white and colored alike; I mean services that

are entailed in departmental heads calling on the ele

mentary school system, such as music department, and giv

ing supervision and advice to the teachers. That is what I

mean.

Judge Huxman: Is there anything else that you include

in services ?

Mr. Goodell: No, that is what I mean.

Judge Huxman: All right. And your request, requested

admission, that these services which you have mentioned

are furnished both in the colored schools and in the white

schools.

Mr. Goodell: That is correct.

Mr. John Scott: We don’t accept that, if Your Honor

please. I think that is a little too indefinite; we need a lit

tle more definite and certain------

Judge Huxman: That is the reason I asked you to state

[fol. 50] specifically the kind of services he had in mind.

Mr. John Scott: Yes, Your Honor, I understand that, but,

as it stands in the stipulation at the present time, we

wouldn’t have a way of knowing.

Judge Huxman: The stipulation as it reads in the

printed record isn’t going to be the record. The record

33

that is made is as modified by the statements of Mr. Goodell.

They are the ones that go into the record.

All right; is that agreed to, then?

Mr. Carter: That is agreeable, Your Honor.

Judge Huxman: That is agreeable.

Judge Mellott: Well, are there any other services that

either side thinks should be incorporated. Now, I have in

my mind some three or four services. Now, in order to

make that complete, do you wish to give us a more detailed

or do you wish to add anything to the services which Mr.

Goodell has referred to?

Mr. Carter: No, sir. We have one item that I think I

spoke of before. I think that Mr. Goodell indicated that it

was a service, but he doesn’t include that in his special

statements. The statement is satisfactory to us.

Judge Mellott: The word “ services” is rather big and

broad and all-inclusive.

Judge Huxman: Of course, it—all right, that is agreed

[fol. 51] to, then, as modified by the explanation; the fur

nishing of services as stated is agreed to.

We will take up No. 8:

“ That the distance traveled by colored children in reach

ing the schools they attend is not on the average greater

than the distance wdiite children are required to travel to

reach the schools they attend.”

Mr. Carter: Well, Your Honor, I don’t think we want to

stipulate on this. I don’t think it has anything to do with

the case. I think it ’s irrelevant.

Mr. Goodell: If the Court please, on that point, it is

merely a mathematical proposition. That map, Exhibit

“ A ” , shows the whole City of Topeka and territory out

side of the city is in blue, which is in Topeka for school

purposes. We have marked on the map, Exhibit “ A ” , each

school territory. It shows, of course, the physical facts

of distances which appear on this city map and can be com

puted. Children, in other words, living, for example—tak

ing Exhibit “ A ” —in the blue territory over here in the

corner (indicating) their school that they would have to go

to, white children, would be Randolph, and all of that. Of

course the matter of various school distances are written in

3— 8

34

on the map—are identified. Of course to get at it any more

accurately, which would be almost an intolerable job, Would

be to get each child that went to the city schools and get the

[fob 52] actual distance travelled divided by the number of

children, and then you would get the average, and then

get each colored child and get the actual distance divided by

number of children, and then you would have the average.

Judge Huxman: Mr. Goodell, I doubt whether the Court

would want that kind of a stipulation agreed to. That

might be mathematically correct when you take an outlying

territory. Now, to reach that result, you take territory that

is not in the city limits and that------

Mr. Goodell: I have done some computing with a ruler,

and I have taken the school population of the various

schools, and I have taken distances in various different

territories, and I know that as a matter of fact, it’s a con

servative statement, it ’s on the conservative side.

Judge Huxman: Well, now you may be right, but I

wouldn’t want this, as far as I am concerned; I wouldn’t be

content to have it established by stipulation that you can

have four schools in the City of Topeka for one group of

people and eighteen for another in that same territorial