Wetzel v. Abu-Jamal Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

September 9, 2011

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wetzel v. Abu-Jamal Brief in Opposition, 2011. d14d75e0-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69e1246e-c742-45bd-97c6-5ff70f3ea80c/wetzel-v-abu-jamal-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

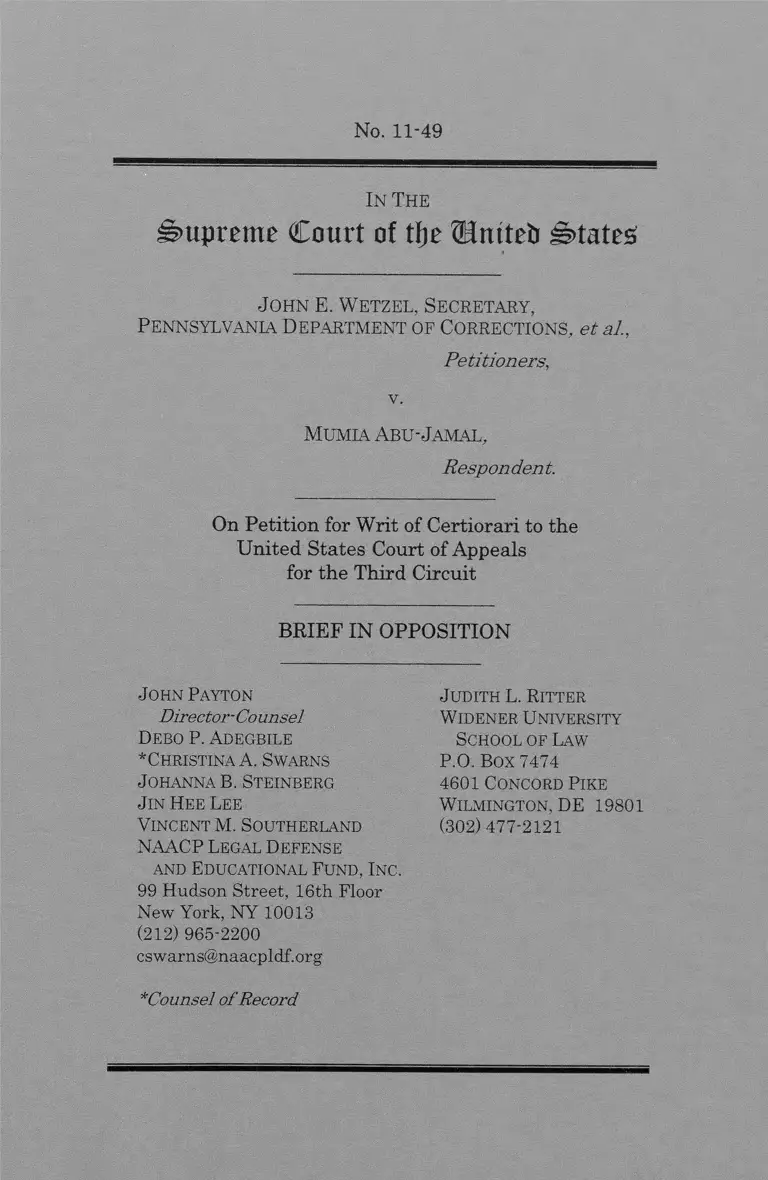

No. 11-49

In The

rnpreme Court of tfje ©mteti States!

John E. W etzel, Secretary ,

Pennsylvania D epartm ent of Corrections , e t al.,

P etitioners,

v.

Mu m ia A b u -Ja m a l ,

R espondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

John Payton

Director-Counsel

Debo P. Adegbile

*ChristinaA. Swarns

Johanna B. Steinberg

Jin Hee Lee

Vincent M. Southerland

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

cswarns@naacpldf.org

Judith L. Ritter

Widener University

School of Law

P.O. Box 7474

4601 Concord Pike

Wilmington, DE 19801

(302) 477-2121

*Counsel o f Record

mailto:cswarns@naacpldf.org

1

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.........................................iv

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..................................... 1

ARGUMENT............................................................. 1

I. The Third Circuit’s Decision on Remand

Is Correct................................................................. 2

A. Procedural History.............................................. 2

1. State Court............... ...............................2

2. District Court............................................3

3. Court of Appeals...................................... 4

4. This Court................................................. 4

5. Court of Appeals on Remand.................. 5

B. The Third Circuit’s Mills Analysis Was

Correct and Supported By the Record..............8

1. The verdict form ’s opening

statement required unanimous

findings by the jury of mitigating

circumstance(s)..........................................9

2. The verdict form provided space

for only one check next to each

mitigating circumstance........................11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(continued)

3. Additional language in the

verdict form required unanimous

finding of mitigating

circumstances...........................................13

4. The verdict form required the

signatures o f all twelve jurors

below the list of mitigating

circumstances....................... 14

5. Aggravating and mitigating

circumstances are treated

identically on the verdict form...............15

6. Mr. Abu-Jamal’s verdict form was

more problematic than the Mills

verdict form .............................................. 15

7. The trial court’s oral instructions

compounded the Mills error ................. 16

8. Changes to Pennsylvania’s capital

jury instructions and verdict form

after Mills underscore the

constitutional error.................................22

C. The Third Circuit Correctly Found That

This Case Is Very Different Than

Spisak...................................................................22

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(continued)

D. The Third Circuit Correctly Found That

the State Court’s Ruling Unreasonably

Applied Mills......................................................27

1. The state court’s exclusive focus

on the verdict form was

objectively unreasonable....................... 28

2. The state court’s Mills analysis

was limited to one portion of the

verdict form .................................. 29

II. This Court Should Deny Certiorari

Because Petitioners’ Quarrel Is with the

Third Circuit’s Application of Properly

Stated Rules of Law to the Facts of this

Case.........................................................................37

III. This Court Should Deny Certiorari

Because the Circuit Court’s Grant of

Mills Relief is Unlikely to Affect Future

Cases....................................................................... 38

CONCLUSION................................................. 41

ADDENDUM.............................................. la

IV

Cases

Page(s)

Abu-Jamal v. Horn,

520 F.3d 272 (3d Cir. 2008).............................. 4, 29

Abu-Jamal v. Horn, No. CIV. A. 99-508,

2001 WL 1609690

(E.D. Pa. Dec. 18, 2001)................................. passim

Abu-Jamal v. Secretary,

643 F.3d 370 (3d Cir. 2011)...........................passim

Albrecht v. Horn,

485 F.3d 103 (3d Cir. 2007)................................... 39

Beard v. Abu-Jamal,

130 S. Ct. 1134 (2010)...................................... 5, 37

Beard v. Banks,

542 U.S. 406 (2004)................................................. 38

Boyde v. California,

494 U.S. 370 (1990)............................................ 8, 32

Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal,

555 A.2d 846 (Pa. 1989)........................................... 2

Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal,

720 A.2d 79 (Pa. 1998)....................................passim

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Commonwealth v. Murphy,

657 A.2d 927 (Pa. 1995)......................................... 34

Cullen u. Pinholster,

131 S. Ct. 1388 (2011)..................................... 27, 28

Fahy u. Horn,

516 F.3d 169 (3d Cir. 2008).................................. 39

Frey v. Fulcomer,

132 F.3d 916 (3d Cir. 1997)..................... 21, 39, 40

Gonzalez v. Justices of Mun. Ct. of Boston,

420 F.3d 5 (1st Cir. 2005)........................................5

Grutter v. Bollinger,

539 U.S. 306, 322 (2003)........................................ 38

Hackett v. Price,

381 F.3d 281 (3d Cir. 2004).................................. 39

Harrington u. Richter,

131 S. Ct. 770 (2011)................ ........ .............. 27, 28

Kelly v. South Carolina,

534 U.S. 246 (2002)................................................ 28

Kindler v. Horn,

542 F.3d 70 (3d Cir. 2008),

vacated and remanded on other grounds,

130 S. Ct. 612 (2009) 39

V I

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Kindler v. Horn,

542 F.3d 70 (3d Cir. 2008),

vacated and remanded on other grounds,

130 S. Ct. 612 (2009).............................................. 39

Mills v. Maryland,

486 U.S. 367 (1988)......................................... passim

Noland v. French, 134 F3d 208 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 525 U.S. 851 (1998).......................... 36

Schriro v. Landrigan,

550 U.S. 465 (2007)............................................ 7, 37

Smith v. Spisak,

129 S. Ct. 1319 (2009)................................................4

Smith v. Spisak,

130 S. Ct. 676 (2010)....................................... passim

State v. Gumm,

653 N.E.2d 253 (Ohio 1995)................................. 22

State v. Jenkins,

473 N.E.2d 264 (Ohio 1984)................................. 22

Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668 (1984)........................... ........... ......... 27

Stutson v. United States,

516 U.S. 163 (1996).................................................... 5

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Szuchon v. Lehman,

273 F.3d 299 (3d Cir. 2001).................................. 39

Teague v. Lane,

489 U.S. 288 (1989).............................................. . 38

Uttecht v. Brown,

127 S. Ct. 2218 (2007)................................................

Williams v. Taylor,

529 U.S. 362 (2000)........................................ passim

Zettlemoyer v. Fulcomer,

923 F.2d 284 (3d Cir. 1991)............... 24, 35, 36, 39

Docketed Cases

Banks v. Horn,

No. 99-9005 (3d Cir. Aug. 25, 2004).................... 39

Statutes and Rules

Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty

Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d).............................. ..passim

Pa. R. Crim. P. 358 A ................................................. 22

Supreme Court R. 10................... ................................37

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

V l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Other Authorities

Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

Beard v. Abu-Jamal, No, 08-652,

2008 WL 4933629 (U.S. Nov. 14, 1008)

1

In Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367 (1988), this

Court declared that instructions indicating that a

juror cannot “find a particular circumstance to be

mitigating unless all 12 jurors agree[ ] that the

mitigating circumstance ha[s] been prove [n] to

exist,” are unconstitutional. Smith u. Spisak, 130 S.

Ct. 676, 682 (2010) (citing Mills, 486 U.S. at 380-

381). In this case, the United States Court of

Appeals for the Third Circuit, on remand from this

Court, properly found that the verdict form and oral

instructions given to Respondent’s sentencing jury

violated Mills. Specifically, after appropriately

applying the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death

Penalty Act (“AEDPA”), 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d), the

appellate court found that the form and instructions,

taken together, required unanimity in the finding of

mitigation, that the instructions at issue are

materially different from those found to be

acceptable in Spisak, and that the state court’s

decision was objectively unreasonable. Because the

Circuit Court’s decision is appropriately deferential

and amply supported by the record, certiorari review

is inappropriate.

ARGUMENT

This Court should deny certiorari because the

Third Circuit’s decision on remand is correct; the

Circuit applied properly stated rules of law to the

facts of this case; and the Circuit Court’s grant of

Mills relief is unlikely to affect future cases.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The Third Circuit’s Decision on Remand Is

Correct.

The Third Circuit’s conclusion that the Abu-

Jamal jury instructions and verdict form were

significantly different from - and worse than - those

in Spisak and that the state court’s rejection of

Respondent’s Mills claim was objectively

unreasonable, is well supported by the record.

Petitioners mischaracterize the Circuit’s reasoning,

fail to acknowledge substantial differences between

this case and Spisak and incorrectly describe the

state of the law at the time of the state court’s

decision.1

A. Procedural History

The procedural history of Respondent’s Mills

claim demonstrates that the Circuit Court has

consistently and appropriately conducted the

deferential review required by § 2254(d).

1. State Court.

Respondent Mumia Abu-Jamal was sentenced to

death in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The

Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed on direct

appeal, Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal, 555 A.2d 846

(Pa. 1989) (“Abu-Jamal-1”), and denied post

conviction relief, Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal, 720

A.2d 79 (Pa. 1998) (“Abu-Jamal-2”). In the state

post-conviction proceedings, Mr. Abu-Jamal

2

1 As detailed in the Procedural History, supra at pp. 2-8,

both the District Court and the Third Circuit properly

recognized and applied the deferential standard of review set

forth by § 2254(d).

3

exhausted a claim that the capital sentencing verdict

form and jury instructions violated Mills.

2. District Court.

On federal habeas review, the U.S. District Court

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania (the

“District Court”) addressed the Mills claim at length.

Abu-Jamal u. Horn, No. CIV. A. 99-5089, 2001 WL

1609690, *1, *114-*127 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 18, 2001)

(“Abu-Jamal-3”).

The District Court emphasized that it was

applying the deferential standards set forth by the

AEDPA, 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d), as required by this

Court’s ruling in Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362

(2000). Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690, at *10-*11

(Williams “cautioned federal habeas courts against

insufficiently deferential review of state court

decisions”) (citing Williams, 529 U.S. at 409); id. at

*107 (same) (citing Williams, 529 U.S. at 409); id. at

*116 n.82 (“important to reiterate” in addressing a

Mills claim that “a significant degree of deference is

due the state supreme court’s application of federal

law”).

Applying AEDPA, the District Court found that

the jury instructions and verdict sheet violated Mills

and that the state court’s decision on the Mills claim

was objectively unreasonable under § 2254(d)(1),

Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690, at 130.

Accordingly, the District Court vacated the death

sentence. Id.

4

3. Court of Appeals.

The Third Circuit unanimously affirmed the

District Court’s finding of Mills error. Abu-Jamal v.

Horn, 520 F.3d 272 (3d Cir. 2008) (“Abu-Jamal-4”).

It explained that it was applying the deferential

standards of § 2254(d). Id. at 292 & n.21 (describing

AEDPA’s “deferential standard” of review); id. at

278-79 (collateral review requires deference unless

“unreasonable application” threshold under §

2254(d)(1) is met); id. at 279, 287-88 (Mr. Abu-

Jamal’s habeas petition was “subject to AEDPA”); id.

at 300 (“Our review is limited to whether the

Pennsylvania Supreme Court unreasonably applied

Mills.”) (citing § 2254(d)(1) and Williams, 529 U.S. at

405).

After applying Mills and § 2254(d), and

considering the verdict form, the oral instructions,

and the state court’s ruling, the Circuit affirmed the

grant of habeas relief. Id. at 301-304.

4. This Court.

In 2008, Petitioners filed a certiorari petition,

seeking this Court’s review of the Third Circuit’s

ruling. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Beard v. Abu-

Jamal, No. 08-652, 2008 WL 4933629 (U.S. Nov. 14,

1008).

On February 23, 2009, while Petitioners’

certiorari petition was pending, this Court granted

certiorari in Smith v. Spisak, 129 S. Ct. 1319 (2009),

to review, inter alia, the Sixth Circuit’s grant of

relief under Mills. On January 12, 2010, this Court

reversed the Sixth Circuit. Spisak, 130 S. Ct. 676.

5

On January 19, 2010, this Court issued a “GVR”

order in the instant case: “Petition for writ of

certiorari granted. Judgment vacated, and case

remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for

the Third Circuit for further consideration in light of

Smith v. Spisak.” Beard v. Abu-Jamal, 130 S. Ct.

1134 (2010) (“Abu-Jamal-5”).2

5. Court of Appeals on Remand.

After new briefing and oral argument, the Third

Circuit again unanimously found that the jury

instructions and verdict form violated Mills, that the

state court unreasonably applied clearly established

federal law, and that habeas relief was required

under § 2254(d)(1). Abu-Jamal v. Secretary, 643

F.3d 370, 372 (3d Cir. 2011) (“Abu-Jamal-ff’). '

The Third Circuit again emphasized that it was

applying the deferential standards of AEDPA’s §

2254(d):

Our review on remand is limited to

whether the Pennsylvania Supreme

Court unreasonably applied United

States Supreme Court precedent in

finding no constitutional defect in the

jury instructions and verdict form

employed in the sentencing phase of

Abu-Jamal’s trial. See 28 U.S.C. §

zThis Court’s “GVR” order was what Justice Scalia has

suggested “might be called [a] ‘no-fault V & R’: vacation of a

judgment and remand without any determination of error in

the judgment below.” Stutson v. United States, 516 U.S. 163.

178 (1996) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (emphasis in original); see

Gonzalez v. Justices of Mun. Ct. of Boston, 420 F.3d 5, 7 (1st

Cir. 2005).

6

2254(d)(1); Williams [ ], 529 U.S. [at]

405-06 . . . . Pursuant to the Supreme

Court’s order, we consider this question

in light of Spisak . . . .

Under [§ 2254(d)], a state prisoner’s

application for a writ of habeas corpus

will be denied unless the adjudication of

a claim in state court proceedings ‘‘(1)

resulted in a decision that was contrary

to, or involved an unreasonable

application of, clearly established

Federal law, as determined by the

Supreme Court of the United States; or

(2) resulted in a decision that was based

on an unreasonable determination of

the facts in light of the evidence

presented in the State court

proceeding.” 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(l)-(2).

Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 373. The Circuit

explained that because the state court properly

identified and applied Mills to Respondent’s claim,

its decision was not “contrary to” clearly established

law. Id. at 374 (citing Williams, 529 U.S. at 405).

The Circuit therefore considered whether the state

court’s decision involved an “unreasonable

application” of federal law under § 2254(d)(1), and

noted that:

“a federal habeas court may not issue

the writ simply because that court

concludes in its independent judgment

that the relevant state-court decision

applied clearly established federal law

erroneously or incorrectly. Rather, that

7

Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 374. Thus:

in making this inquiry, we “should ask

whether the state court’s application of

clearly established federal law was

objectively unreasonable.” Williams,

529 U.S. at 409.

Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 374.

The Circuit then observed that its specific task on

remand was to reconsider its earlier ruling in light of

Spisak. Because this Court found no Mills violation

in Spisak, the Circuit first “evaluate[d] whether a

Mills violation has occurred, and then proceeded] to

examine whether the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s

application of Mills was objectively unreasonable

under the second clause of § 2254(d)(1).” Id. at 374.

After carefully comparing the Mills and Abu-

Jamal verdict sheets and jury instructions, id. at

374-77, the Circuit concluded that “the [.Abu-Jamal]

verdict form together with the jury instructions”

indicated that the jury could only consider the

mitigating circumstances that it found unanimously.

Id. at 377.

It then compared the Abu-Jamal and Spisak

instructions and verdict forms, id. at 377-81, and

found that the “verdict form and judge’s instructions

used in the sentencing phase of Abu-Jamal’s trial are

materially different and easily distinguished from

those at issue in Spisak,” id. at 379. Thus, the

application must also be unreasonable.”

Williams, 529 U.S. at 411; see Schriro v.

Landrigan, 550 U.S. 465, 473 [ ] (2007).

8

Circuit concluded that its finding of a Mills violation

was “consistent with Spisak.” Id. at 380-81.

Finally, the Third Circuit applied AEDPA’s

deferential standards to the state court’s decision on

the Mills claim and concluded that it was objectively

unreasonable. Id. at 374, 381. Thus, the Third

Circuit again affirmed the District Court’s grant of

habeas relief as to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s death sentence.

Id. at 383.

B. The Third Circuit’s Mills Analysis Was

Correct and Supported By the Record.

The Circuit unanimously found that the “verdict

form together with the jury instructions read that

unanimity was required in the consideration of

mitigating circumstances and that there is a

substantial probability3 the jurors believed they

were precluded from independent consideration of

mitigating circumstances in violation of Mills.” Id.

at 377.

3 The Third Circuit noted that in Spisak, this Court

described the relevant standard to be a “substantial possibility”

but concluded that since Mills termed the standard to be

“substantial probability,” this Court’s use of the word,

“possibility” was likely inadvertent. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at

374 n.3. In Boyde v. California, 494 U.S. 370 (1990), this

Court clarified that the relevant legal standard was “whether

there is a reasonable likelihood that the jury has applied the

challenged instruction in a way that prevents consideration of

constitutionally relevant evidence.” Id. at 378. The Third

Circuit found that a ‘“substantial probability’, is neither more

nor less than [the Boyde standard of] a ‘reasonable likelihood’”

and that it would utilize the “substantial probability” standard

to be consistent with Spisak. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 375 n.4.

9

Petitioners assert that requiring unanimity for

the weighing result does not violate Mills. Petition at

12. Respondent agrees. Read in isolation from the

rest of the instructions and verdict form, the

weighing instruction correctly stated the law.

Petitioners erroneously contend, however, that

the Third Circuit found a Mills violation based solely

on this weighing language. Id. at 11; see id. at 10,

12, 24. Contrary to Petitioners’ claims, the opinion

makes clear that it was the rest of the verdict form

along with the oral instructions that created a

substantial probability that the jury would believe it

could only consider and weigh unanimously found

mitigating circumstances against the aggravating

circumstances. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 375-76.

The Circuit’s finding that the state court was

objectively unreasonable in “conduct [ing] an

incomplete analysis of only a portion of the verdict

form, rather than the entire form,” id. at 381, offers

further proof that it did not rely solely on the

weighing instruction as the basis for granting Mills

relief. As in Mills, Mr. Abu-Jamal’s jury was misled

regarding the task that preceded the ultimate

weighing — the process of identifying and considering

mitigation.

Accordingly, the appellate court’s finding of a

Mills violation was correct.

1. The verdict form’s opening

statement required unanimous

findings by the jury of mitigating

circumstance (s).

The opening language on Page One of the verdict

form reads as follows:

10

We, the jury, having heretofore

determined that the above-named

defendant is guilty of murder of the

first degree, do hereby further find that:

App. 131. That language is followed by:

(1) We, the jury, unanimously

sentence the defendant to

El death

□ life imprisonment.

(2) (To be used only if the aforesaid

sentence is death)

We, the jury, have found

unanimously

□ at least one aggravating

circumstance and no mitigating

circumstance. The aggravating

circumstance(s) is/are

3 one or more aggravating

circumstances which outweigh

any mitigating circumstances.

The aggravating circumstance(s)

is/are A .

The mitigating circumstance(s)

is/are A .

Id. at 131-32.

11

By opening with “fwje, the jury, having heretofore

determined that the defendant is guilty of murder of

the first degree, do hereby further find that-”, id. at

131 (emphasis added), the verdict form required that

everything marked on it be found by the same jury

that found Mr. Abu-Jamal guilty — i.e., the

unanimous jury. The form did not allow an

individual juror to find anything on his own,

including a mitigating circumstance.

Page One of the verdict form required the jury to

specify the sentence; what u[t]he aggravating

circumstance(s) is/are and what “ [t]he

mitigating circumstance(s) is/are Id. at 131-32.

(emphasis added). Because the opening statement

required all verdict form findings to be unanimous,

the form mandated that the sentence, the

aggravating circumstances and the mitigating

circumstances be unanimously found. While the

first two requirements are proper, the third violates

Mills.

2. The verdict form provided space

for only one check next to each

mitigating circumstance.

Pages Two and Three of the verdict form read as

follows:

AGGRAVATING AND MITIGATING

CIRCUMSTANCES

AGGRAVATING CIRCUMSTANCED:

(a) The victim was a fireman,

peace officer or public servant

concerned in official detention

12

who was killed in the

performance of his duties. (*'')

[nine more statutory aggravating

circumstances, labeled (b)-(j) and

followed by a ( ), not checked by

the jury]

MITIGATING CIRCUMSTANCE(S):

(a) The defendant has no

significant history of prior

criminal convictions (S)

[seven more statutory mitigating

circumstances, labeled (b)-(h) and

followed by a ( ), not checked by

the jury]

[twelve lines with signatures of all

jurors]

App. 132-35.

Thus, the jury was presented with a list of ten

possible aggravating circumstances, and a list of

eight possible mitigating circumstances, with a “( )”

next to each aggravating and mitigating

circumstance to be checked, if found. The space

provided next to each mitigating circumstance is too

small for any marking beyond a single checkmark.

Also, the form did not provide a mechanism for any

individual juror to find, or indicate that s/he has

found, independent of other jurors, a mitigating

circumstance. These factors reinforce the notion

that only unanimously found mitigating

13

circumstances were to be considered. Read together

with the opening statement that directed the jury to

record only those items that are were unanimously

found, the verdict form led the jury to believe that it

could only consider an aggravating or mitigating

circumstance that was unanimously found.

3. Additional language in the

verdict form required

unanimous finding of mitigating

circumstances.

Just below the lines calling for the jury’s

sentence, the following express unanimity

requirement appears on Page One of the verdict

form:

We, the jury, have found

unanimously

□ at least one aggravating

circumstance and no mitigating

circumstance. The aggravating

circumstance(s) is/are_________ .

I5D one or more aggravating

circumstances which outweigh

any mitigating circumstances.

The aggravating circumstance(s)

is/are A .

The mitigating circumstance(s)

is/are A

App. 131-32 (emphasis added).

This portion of the form also requires the jury to

find and consider only the aggravating and

14

mitigating circumstances that it has “found

unanimously.” Id. at 131 (emphasis added). Because

this language was read in conjunction with the

verdict form’s opening statement requiring the jury

to note only those findings that “we, the jury, have

found unanimously,” and the list of choices, each

with one corresponding box that could be checked,

directly underneath the opening statement, the only

plausible interpretation is that the specifications of

aggravators and mitigators on the lines provided

required unanimous findings.

4. The verdict form required the

signatures of all twelve jurors

below the list of mitigating

circumstances.

The end of the verdict form, just below the list of

mitigating circumstances on Page Three, requires

the signatures of all twelve jurors. Id. at 135. This

also ensured that only unanimously found

mitigating circumstances are considered. If fewer

than twelve jurors found a mitigating circumstance,

checked it on the checklist on Page Three (although

the form opens with a requirement that only

findings of the unanimous jury be recorded), and

wrote it on Page One (although Page One states “We

the jury have found unanimously . . . [t]he mitigating

circumstanee(s) is/are ___”, id. at 131-32), then the

jurors who disagreed could not sign the verdict form

without violating their oaths. The presence of all

twelve signatures confirms the form’s direction to

unanimously consider and find mitigating

circumstances.

15

5. Aggravating and mitigating

circumstances are treated

identically on the verdict form.

The unanimous finding of mitigating

circumstances was also required by the verdict

form’s consistently identical treatment of

aggravating and mitigating circumstances. To

comply with Mills, the jury would have had to ignore

this and believe, contrary to the form’s plain

language and without any rational basis, that

aggravation and mitigation should be treated

differently. The court must “presume that, unless

instructed to the contrary, the jury would read

similar language throughout the form consistently.”

Mills, 486 U.S. at 378.

6. Mr. Ahu-Jamal’s verdict form

was more problematic than the

Mills verdict form.

In finding constitutional error, the Third Circuit

relied upon the similarities between the Mills and

Abu-Jamal verdict forms, Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at

375-77. However, for several reasons, the Abu-Jamal

form was more likely than the Mills form to be

understood to require a unanimous mitigation

finding.

The Mills form allowed the jury to mark “yes” or

“no” for each listed mitigating circumstance, and the

list was prefaced with: “ [W]e unanimously find that

each of the following mitigating circumstances which

is marked ‘yes’ has been proven to exist . . . and each

mitigating circumstance marked ‘no’ has not been

proven . . . .” Id. at 375. Maryland’s high court

interpreted the jury’s “no” entries as showing that

16

the jury unanimously rejected the “no”-marked

mitigating circumstance. See id. at 372. So-

interpreted, the death sentence was constitutional —

if the jury unanimously rejected each mitigating

circumstance, no individual juror found a mitigating

circumstance and no juror was prevented from

giving effect to mitigation that s/he believed to exist.

This Court found the Maryland court’s

interpretation of the form “plausible” in light of the

form’s language. It was nevertheless declared

unconstitutional because it was unclear that the jury

interpreted the form the same way as the Maryland

court. See id. at 375-76.

The Abu-Jamal form is not even susceptible to

the “plausible” interpretation that the Maryland

court gave the Mills form. Unlike in Mills, Mr. Abu-

Jamal’s jury’s only options were to check a

mitigating circumstance if it was found, or leave it

blank. The failure to check plainly signifies the

jury’s failure to unanimously find a mitigating

circumstance. Thus, the Mills violation is clearer in

Abu-Jamal than it was in Mills itself.

7. The trial court’s oral

instructions compounded the

Mills error.

As the Third Circuit recognized, “the instructions

throughout and repeatedly emphasized unanimity.”

Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 377. The judge told the

jury: “You will be given a verdict slip upon which to

record your verdict and findings.” App. 127. Here,

and throughout, the judge made no distinction

between “findings” of aggravating circumstances and

“findings” of mitigating circumstances, except for

17

different burdens of proof. See infra. Section I. B. 7.

Thus, the jury had no reason to believe that there

were any differences (other than burdens of proof)

between the processes for finding aggravating and

mitigating circumstances — the instructions required

both to be found unanimously.

The judge also instructed the jury on how to use

the checklist of aggravating circumstances on Page

Two and how to identify aggravating circumstances

on Page One:

[W]hat you do, you go to Page 2. Page 2

lists all the aggravating circumstances.

They go from small letter (a) to small

letter (j). Whichever one of these that

you find, you put an “X” or check mark

there and then, put it in the front.

Don’t spell it out, the whole thing, just

what letter you might have found.

App. 128.

The judge then used materially identical

language to explain how to use Page Three’s

checklist of mitigating circumstances and how to

complete Page One’s identification of the mitigating

circumstances:

[Tjhose mitigating circumstances

appear on the third page here, they run

from a little (a) to a little letter (h).

And whichever ones you find there, you

will put an “X” mark or check mark and

then, put it on the front here at the

bottom, which says mitigating

circumstances. And you will notice that

18

on the third or last page, it has a spot

for each and every one of you to sign his

or her name on here as jurors . . . .

App. 129.

These instructions, like the verdict form itself,

treat aggravating and mitigating circumstances

identically - both were to be “found” and recorded by

a unanimous jury. As the Third Circuit found, “in

light of the language and parallel structure of the

form and instructions in relation to aggravating and

mitigating circumstances, it is notable that neither

the verdict form nor the judge’s charge said or in any

way suggested that the jury should apply the

unanimity requirement to its findings of aggravating

but not mitigating circumstances.” Abu-Jamal-6,

643 F.3d at 377. The instructions do not even hint

that the jury must unanimously find an aggravating

circumstance, but not a mitigating one. Instead, the

last instruction on finding mitigating circumstances

and signing the form “places in the closest temporal

proximity the task of finding the existence of

mitigating circumstances and the requirement that

each juror indicate his or her agreement with the

findings of the jury” by signing the form. Abu-

Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690, at *125. The judge’s

instructions on how to use the verdict form thus

exacerbated the form’s Mills error.

Other oral instructions also led the jury to treat

aggravating and mitigating circumstances in the

same manner:

Members of the jury, you must now

decide whether the defendant is to be

19

sentenced to death or life

imprisonment. The sentence will

depend upon your findings concerning

aggravating and mitigating

circumstances. The Crimes Code

provides that the verdict must be a

sentence of death if the jury

unanimously finds at least one

aggravating circumstance and no

mitigating circumstance, or if the jury

unanimously finds one or more

aggravating circumstances which

outweigh any mitigating circumstances.

The verdict must be a sentence of life

imprisonment in all other cases.

Remember, that your verdict must be a

sentence of death if you unanimously

find at least one aggravating

circumstance and no mitigating

circumstance. Or, if you unanimously

find one or more aggravating

circumstances which outweigh any

mitigating circumstances. In all other

cases, your verdict must be a sentence

of life imprisonment.

App. 124-25; 126-27. In these instructions, like all of

the instructions, aggravating and mitigating

circumstances are treated identically as matters to

be “found” by the unanimous jury or not considered

at all. Nothing in the instructions would allow the

jury to reasonably conclude that mitigating and

20

aggravating circumstances should be treated

differently.

The Third Circuit also found that the failure to

distinguish between the process of finding

aggravators and mitigators was “notable because the

trial court distinguished between the two with

respect to the proper burden of proof the jury should

apply.” Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 377. In this

regard, the court instructed the jury that:

Whether you sentence the defendant to

death or to life imprisonment will

depend upon what, if any, aggravating

or mitigating circumstances you find

are present in this case.

[Aggravating circumstances must be

proved by the Commonwealth beyond a

reasonable doubt, while mitigating

circumstances must be proved by the

defendant by a preponderance of the

evidence.

Addendum at 2a.

The Commonwealth has the burden of

proving aggravating circumstances

beyond a reasonable doubt. The

defendant has the burden of proving

mitigating circumstances, but only by a

preponderance of the evidence. This is

a lesser burden of proof than beyond a

reasonable doubt.

App. 126.

21

Since the instructions stressed the different

burdens for proving aggravating and mitigating

circumstances, but were silent as to any differences

in the manner of proof, jurors would naturally

conclude that both “aggravating and mitigating

circumstances must be discussed and unanimously

agreed to, as is typically the case when considering

whether a burden of proof has been met.” See Frey v.

Fulcomer, 132 F.3d 916, 924 (3d Cir. 1997)

(emphasis in original). Thus, the burden of proof

instructions “likely cemented the jury’s mistaken

impression that it was obligated not to consider a

mitigating circumstance that was found to exist by

anything other than the entire panel.” Abu-Jamal-3,

2001 WL 1609690, at *119 (emphasis in original).

The jury instructions were also problematic

because the judge repeatedly used the pronoun “you”

to refer without distinction to the entity that “finds”

the defendant guilty, “finds” a sentence, “finds”

aggravating circumstances, and “finds” mitigating

circumstances.4 To satisfy Mills, the jury would

have to have know that “you” meant the “unanimous

jury” for the first three matters, but meant “each

individual juror ’ for the last. However, the “natural

interpretation,” Mills, 486 U.S. at 381, of the

instructions was that the same “you” - the

unanimous jury — must make all of these findings.

4 See also App. 1224-29.

22

8. Changes to Pennsylvania’s

capital jury instructions and

verdict form after Mills

underscore the constitutional

error.

Just as this Court did in Mills, the Third Circuit

noted that Pennsylvania adopted a new uniform

sentencing verdict form for capital cases after Mills

was decided. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 382 (citing

Pa. R. Crim. P. 358 A). “ [T]he new form . . . makes

explicit that unanimity is not required in

determining the existence of mitigating

circumstances.” Id.

The Pennsylvania Suggested Standard Criminal

Jury Instructions were likewise amended in

response to Mills and now make clear that the jury

needs to be unanimous before finding an aggravating

circumstance, but need not be unanimous to consider

or find a mitigating circumstance. See id. “ [Tjhese

clarifications highlight the ambiguity at issue in this

case.” Id. at 383.

C. The Third Circuit Correctly Found That

This Case Is Very Different Than Spisak.

This Court found that the Spisak jury

instructions and verdict form did not violate Mills.

Mr. Spisak’s trial was in Ohio where capital juries

find the presence or absence of aggravating factors

at the guilt phase. Spisak, 130 S. Ct. at 680, 683. 5

Thus, after the penalty phase evidence was

presented, the legal instructions and form given to

5 See State u. Gumm, 653 N.E.2d 253, 260 (Ohio 1995);

State v. Jenkins, 473 N.E.2d 264, 277 (Ohio 1984).

the jury were brief. They can be summarized as

follows:

1. Oral Instructions:

a. Explanation and examples of

mitigating factors;

b. Weighing instruction — aggravating

circumstances against mitigating

circumstances.

2. Verdict Form:

a. Two forms for each murder count —

both solely addressed weighing;

b. One form read, in its entirety: “We

the jury in this case . . . do find

beyond a reasonable doubt that the

aggravating circumstances which

the defendant . . . was found guilty

of committing were sufficient to

outweigh the mitigating factors

present in this case. We the jury

recommend that the sentence of

death be imposed.”

c. The other form read, in its entirety:

“We the jury in this case . . . do find

beyond a reasonable doubt that the

aggravating circumstance which the

defendant . . . was found guilty of

committing are not sufficient to

outweigh the mitigating factors

present in this case. We the jury

23

24

recommend that the defendant . . .

be sentenced to life imprisonment.”

Id. at 683-84.

Petitioners argue that the weighing instructions

in Spisak (2b and 2c above) are virtually identical to

the weighing instruction given here6 7 therefore there

was no Mills violation in Mr. Abu-Jamal’s trial. See

Petition at 9. However, this argument completely

ignores the additional instructions and language in

Mr. Abu-Jamal’s verdict form, none of which were

present in Spisak. As the Third Circuit recognized,

“ [b]y contrast with Spisak, the identified language of

unanimity here indisputably addresses more than

the final balancing of aggravating and mitigating

factors.” Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 379.

The most significant difference between Abu-

Jamal and Spisak is that the Abu-Jamal verdict

form contains express unanimity requirements for

finding mitigating circumstances, and demands that

the jury specify which mitigating circumstances it

has unanimously found. See App. 131-32, 134-35.

The Spisak form, on the other hand, did not require

the jury to make any findings about mitigating

circumstances, and certainly did not require the jury

to specify what mitigating circumstances were

found. See 130 S. Ct. at 684. Instead, the only

finding the Spisak form required the jury to make

was the ultimate sentence. IdP

6 This is not entirely true. The word, “unanimous” does not

appear on the verdict forms in Spisak.

7 While the Spisak form is radically different from the Abu-

Jamal form, it is similar to the form in Zettlemoyer v. Fulcomer,

25

Petitioners argue that there “is no distinction”

between the fact that Mr. Abu-Jamal's jury had to

find and report on found mitigating circumstances

and the Spisak jury did not because the Spisak jury

still had to decide on mitigation. See Petition at 15.

This entirely misses the point. The Mills and Abu-

Jamal juries (but not the Spisak jury) were required

to specify the mitigating circumstances that were

found. The Abu-Jamal jury instructions and verdict

form that purported to explain how to find, and

specify in writing, the proven mitigating

circumstances ultimately produced the Mills

violation. See supra Section 1, B. Indeed, the format

of the Abu-Jamal verdict form made it virtually

impossible for the jury to record or communicate

mitigation not found unanimously. The Spisak

verdict form had no such problem even though the

jury in that case considered the question of

mitigation.

Abu-Jamal’s requirement that the jury specify

the found aggravators and mitigators created

additional Mills problems. A pervasive feature of

the Abu-Jamal verdict form and jury instructions,

which contributed to the Third Circuit’s conclusion

that they violate Mills, is their identical treatment

(aside from burden of proof) of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances to be found by the jury.

The natural conclusion is that, apart from burdens of

proof, aggravating and mitigating circumstances

should be found in the same way - unanimously. See

Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 377.

923 F.2d 284 (3d Cir. 1991), which the Third Circuit held did

not violate Mills. Id. at 308. See also infra Section I. D. 2.

26

The Spisak verdict form and jury instructions

lacked this similar treatment of aggravating and

mitigating factors, mainly because the structure of

the Ohio capital sentencing scheme in Spisak

rendered any similarities between proof of

aggravating and mitigating factors highly unlikely.

As explained above, in Spisak - as in every Ohio

capital case - the aggravating factors were

introduced to and found by the jury at the guilt

phase; at capital sentencing, the judge then

“instructed the jury that the aggravating factors

they would consider were the specifications that the

jury had found proved beyond a reasonable doubt at

the guilt phase.” Spisak, 130 S. Ct. at 683. Because

the aggravating factors were found at the guilt

phase, the jury had no reason to believe that

consideration of mitigating circumstances, which

were first introduced at the sentencing phase, had

anything in common with the manner in which

aggravating factors were proved. The contrast with

Abu-Jamal — where aggravating and mitigating

circumstances were introduced together at sentencing

and treated iden tically, apart from burden of proof —

is profound.

Another important distinction between Spisak

and Abu-Jamal is that Mr. Abu-Jamal’s verdict form

required the signatures of all twelve jurors just

below the checklist on which the jury must record its

findings of mitigating circumstances. The natural

reading of this is that all twelve jurors must agree

that a mitigating factor exists, just as all twelve

must agree as to the existence of each aggravating

factor and the ultimate sentence. See supra Section

I. B. 4. This natural reading of the signatures

27

requirement was reinforced by the judge’s oral

instructions on how to use the form, which expressly

connected the signatures requirement with finding

mitigating circumstances. See supra Section I. B. 7.

Although the Spisak form required the signatures of

all twelve jurors, this fact was wholly insignificant

because the verdict form did not require the jury to

specify what mitigating circumstances were found

and the oral instructions did not connect the

signatures requirement to finding mitigating

circumstances. 130 S. Ct. at 684. As a consequence,

signing the Spisak form signified nothing about an

individual juror’s finding or consideration of

mitigation.

Thus, upon remand for consideration of Spisak’s

impact on its earlier ruling, the Third Circuit

correctly noted the many differences between Abu-

Jamal and Spisak and properly determined that

these differences were crucial to Mr. Abu-Jamal’s

right to have his sentencing jury consider mitigation.

D. The Third Circuit Correctly Found That

the State Court’s Ruling Unreasonably

Applied Mills.

On remand from this Court, the Third Circuit

again found that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

unreasonably applied Mills.8 Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d

8 Petitioners contend that the Third Circuit’s review of the

state court’s decision should have been “doubly deferential.”

Petition at 13 (citing Cullen v. Pinholster, 131 S. Ct. 1388, 1403

(2011); Harrington v. Richter, 131 S. Ct. at 770, 788 (2011)).

Petitioners are mistaken - the “double deference” requirement

governs only claims of ineffective assistance of counsel under

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984). See

28

at 372. This conclusion rested upon two primary

factors: (1) the state court failed to evaluate the

combined effect of the verdict form and the oral

instructions and (2) the state court “conducted an

incomplete analysis of only a portion of the verdict

form, rather than the entire form.” Id. at 381.9

1. The state court’s exclusive focus

on the verdict form was

objectively unreasonable.

The Third Circuit recognized that by the time Mr.

Abu-Jamal’s jury reached the final weighing and

verdict stages of its deliberations, the court’s oral

instructions combined with the verdict form to create

a substantial probability that the jury would only

weigh mitigating circumstances that were found

Harrington, 131 S. Ct. at 788; Pinholster at 1410-11.

Furthermore, as detailed in the Procedural History and

elsewhere above, the Third Circuit, in finding the state court’s

decision objectively unreasonable, properly identified and

applied the deferential standard of review required by § 2254.

Thus, Petitioners’ assertion that the Circuit failed to accord

appropriate deference to the state court decision, Petition at 13-

14, 18, 19, 25, 29, is false. In order to accept Petitioners’

arguments this Court would have to believe that the deference

language repeatedly cited by the Circuit was a smokescreen to

hide its bad faith decisionmaking.

9 It was also objectively unreasonable and contrary to this

Court’s precedent for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to fault

Mr. Abu-Jamal for offering “absolutely no evidence in support

of this claim at the PCRA hearing.” Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at

119. See Mills, 486 U.S. at 381 (“There is, of course, no

extrinsic evidence of what the jury in this case actually

thought. We have before us only the verdict form and the

judge’s instructions.”); Kelly v. South Carolina, 534 U.S. 246,

256 (2002). Here, as in Mills and most cases challenging jury

instructions, the claim is based upon “the verdict form and the

judge’s instructions.” Mills, 486 U.S. at 381.

29

unanimously. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 381-82.

Even if the verdict form’s language on weighing,

taken in isolation, was proper, by ignoring the

impact of the misleading oral instructions and other

parts of the form, the state court failed to account for

the “effect on the jury of being instructed identically

and contemporaneously with respect to the making

of individual determinations regarding mitigating

and aggravating circumstances.” Id. at 381. See

supra Section I. B. 7.

Petitioners contend that the Circuit’s criticism of

the state court’s failure to consider the oral jury

instructions is unfair because Mr. Abu-Jamal’s state

post-conviction appeal relied only on the verdict

form. Petition at 20. This is untrue. Indeed, the

Third Circuit rejected this exact argument and found

that Mr. Abu-Jamal’s state court pleadings “raised a

Mills claim based on both the verdict form and the

jury instructions.” Abu-Jamal-4, 520 F.3d at 299-

300.

2. The state court’s Mills analysis

was limited to one portion of the

verdict form.

The Circuit found the state court’s conclusions

about the verdict form to be objectively unreasonable

because the state court only considered one portion

of that form. Abu-Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 381-82. In

Section I. B above, Mr. Abu-Jamal has presented in

significant detail the Mills-related problems

presented by the verdict form in his trial. Almost

none of these problems were addressed by the state

court because it did not address the entire the form.

For example, the Third Circuit found it objectively

30

unreasonable that the state court failed to “address

the likely effect on the jury of having to choose

aggravating and mitigating circumstances from

visually identical lists and represent its findings as

to each in an identical manner.” Id. at 382.

Instead, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s

decision merely noted that the verdict form

“consisted of three pages” and reached a series of

conclusions that unreasonably focused on language

viewed in isolation from the complete form and the

oral instructions. Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at 119. By

ignoring the ways in which the verdict form imposed

a “requirement of unanimity,” the state court

unreasonably applied Mills. See Williams, 529 U.S.

at 397-98 (state court decision “unreasonable insofar

as it failed to evaluate the totality o f ’ relevant facts).

(a) The state court inaccurately found that the

“requirement of unanimity is found only at Page One

in the section wherein the jury is to indicate its

sentence.” Id. In addition to stating “We, the jury

unanimously sentence the defendant to death,” Page

One also states, “We, the jury, have found

unanimously . . . The aggravating circumstance(s)

is /a re____ A____ . The mitigating circumstance(s)

is/are____A .” App. 131-32. Thus, Page One’s

“requirement of unanimity” expressly applied to the

finding of both aggravating and mitigating

circumstances.

In addition to the express use of the word

“unanimously,” the verdict form opens with the

requirement that everything on the form be the

“findings]” of “the jury” that found Mr. Abu-Jamal

guilty — i.e., the unanimous jury. This applies to

31

Page One’s findings of “mitigating circumstance(s)”

and to Page Three’s checklist of mitigating

circumstances, just as clearly as it applies to Page

One’s findings of “aggravating circumstance(s)” and

Page Two’s checklist of aggravating circumstances.

Moreover, the verdict form closes with the required

signatures of all twelve jurors, reinforcing the

opening statement that all findings - including

mitigation - must be made unanimously. The state

court, however, “never addressed the effect of the

lead-in language.” Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690,

at *126 n.91.

(b) The state court described the second page of

the verdict form as containing “all the statutorily

enumerated aggravating circumstances and . . . a

designated space for the jury to mark those

circumstances found.” Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at 119.

It unreasonably failed to recognize that the list of

mitigating circumstances on Page Three is identical

in format to this list of aggravating circumstances

and, therefore, “the natural interpretation of the

form,” Mills, 486 U.S. at 381, was that both

mitigating and aggravating circumstances must be

unanimously found.

(c) The state court unreasonably relied on the

fact that Page Three, which contains the mitigating

circumstances checklist, “includes no reference to a

finding of unanimity.” Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at

119. As stated above, the verdict form opens with a

requirement that everything therein be found by the

unanimous jury; and the form ends - on Page Three,

just below the checklist of mitigating circumstances

- with a requirement that all twelve jurors sign,

indicating their unanimous agreement with

32

everything on the form. Furthermore, although

Page Two’s list of aggravating circumstances also

contains no “reference to a finding of unanimity,” it

is undisputed that the jury knew it had to find

aggravators unanimously. This identical treatment

of aggravating and mitigating circumstances creates

a “reasonable likelihood,” Boyde, 494 U.S. at 378,

that the jury believed it had to find mitigating

circumstances unanimously.

Furthermore, the state court itself observed that

Page Three is the “section where the jury is to

checkmark those mitigating circumstances found?

Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at 119 (emphasis added).

There is a “reasonable likelihood” that the jury

understood Page Three in exactly that way — that

only mitigating circumstances “found” by “the jury” -

not individual jurors - should be checked and

considered. In order to read Page Three consistent

with Mills, the jury would have to know that each

individual juror should check those mitigating

circumstances s/he found, even if the other jurors

disagreed. To say the least, that is an odd reading of

the verdict form. Moreover, since the jury was to

turn in one verdict form, not twelve, it would have

no way of knowing how to communicate the lack of

unanimity for any mitigating factor. In addition, the

jury would have had to give this treatment to

mitigating circumstances but not aggravating

circumstances, despite the fact that aggravating and

mitigating circumstances are treated identically on

the form.

(d) The state court noted that Pages Two and

Three, containing the lists of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances, include no printed

33

instructions, Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at 119, but

unreasonably failed to recognize that this

contributes to the Mills error. Without instructions

accompanying the lists of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances, the jury had to look to

other parts of the verdict form, the overall structure

of the form, and the judge’s instructions to

understand how to use those lists. As set forth

herein, those factors indicated that aggravating and

mitigating factors must be unanimously found.

(e) The state court unreasonably concluded that

Page Three’s signatures-of-all-jurors requirement

was irrelevant “since those signature lines naturally

appear at the conclusion of the form and have no

explicit correlation to the checklist of mitigating

circumstances.” Abu-Jamal-2, 720 A.2d at 119. The

reason it is “natural0” for the twelve signatures to

“appear at the conclusion of the form” is that it

signifies the agreement of all twelve jurors to the

findings recorded on the form. This is especially

obvious here, where the form opens with a

requirement that everything noted thereon be the

findings of the jurj ,̂ not individual jurors.

To the extent the signatures “have no explicit

correlation to the checklist of mitigating

circumstances,” exactly the same is true for the

checklist of aggravating circumstances and the

sentence. To satisfy Mills, the jurors would have to

know that signing the form signaled agreement to

the sentence entered on Page One and agreement to

the findings of aggravating circumstances entered on

Page Two, but was meaningless with respect to

mitigating circumstances on Page Three — the very

page upon which they were to enter their signatures.

Nothing in the verdict form or instructions conveyed

that illogical concept.

Even if the state court’s “reasoning” about the

signatures made any sense in isolation, it

unreasonably failed to consider the trial judge’s oral

“explanation of th[e] form”. Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL

1609690, at *125. As stated above, the oral

instructions on how to use Page Three made an

“explicit correlation” between the signatures and the

mitigating circumstances and, thereby, cemented the

Mills-violation that is apparent on the face of the

verdict form. The state court unreasonably failed to

consider the effect of the oral instructions on the

jury’s understanding of the form.

(f) The state court’s previous approval, in

Commonwealth u. Murphy, 657 A.2d 927 (Pa. 1995),

of a “verdict slip [] similar to” Mr. Abu-Jamal’s does

not make its decision reasonable. Abu-Jamal-2, 720

A.2d at 119. The entire discussion of the verdict slip

in Murphy is that “the portion of the verdict slip

where the jury is to list mitigating circumstances is

set apart from sections A and B of the verdict slip

which do require a finding of unanimity.” 657 A.2d

at 936. There is no description of what the Murphy

verdict slip actually said.

Petitioners argue that the Circuit’s conclusion

that the state court unreasonably applied Mills is

erroneous because the state court correctly applied

Zettlemoyer, the Circuit’s then-governing Mills

precedent. See Petition at 20-26. This is false. Abu-

Jamal is as different from Zettlemoyer as it is from

Spisak.

34

35

Petitioners incorrectly claim that the Zettlemoyer

instructions were “virtually identical to those here”

and, in support, quote one sentence of the oral

instructions given in Zettlemoyer. Petition at 20-21.

While this single sentence is similar to one part of the

Abu-Jamal oral instructions, there are “important

distinctions” between the two instructions as a

whole. Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690, at 120; see

id. at *123.

More significantly, there are vast differences

between the verdict forms in Zettlemoyer and Abu-

Jamal. See Abu-Jamal-3, 2001 WL 1609690, at *126

n.92. Although Petitioners declare that “the most

cursory” comparison of the forms show they were

“saying exactly the same thing,” Petition at 23

(emphasis added), there are substantial differences

between the verdict forms in Abu-Jamal and

Zettlemoyer.

In finding the Zettlemoyer verdict form

constitutional, the Third Circuit stressed two factors

which materially distinguish it from Abu-Jamal.

First, the Zettlemoyer form said “We the jury

have found unanimously . . . The aggravating

circumstance i s __,” but there was no such language

for mitigating circumstances. 923 F.2d at 308. “The

absence of a similar instruction for mitigating

circumstances indicates that unanimity is not

required.” Id. In sharp contrast, the Abu-Jamal

form contains identical language for aggravating

and mitigating circumstances. App. 131-32. Thus,

the presence on the Abu-Jamal form of “a similar

instruction for mitigating circumstances indicates

that unaninimity” is required.

36

Second, on the Zettlemoyer verdict form, “the jury

was obliged to specify the aggravating circumstance

it found,” but “it had no such duty with respect to

mitigating circumstances, thus suggesting that

consideration of mitigating circumstances was broad

and unrestricted.” 923 F.2d at 308. Again, the Abu-

Jamal form is very different - it required the jury to

specify both the aggravating and mitigating

circumstances it found, with no distinction made

between the two. Thus, the Abu-Jamal verdict form

required both aggravating and mitigating

circumstances be unanimously found.

In short, the Abu-Jamal form suffers from the

exact Mills-violating features that the Third Circuit

found absent from the Zettlemoyer form. Moreover,

the Abu-Jamal form requires a unanimous

mitigation finding for the additional reasons, see

supra Section I. B that also were absent from the

Zettlemoyer form.

The state court’s Mills decision was objectively

unreasonable.10

10 Petitioners contend that Noland v. French, 134 F.3d 208,

213-214 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 525 U.S. 851 (1998), supports

the state court’s decision because it finds that a general

unanimity instruction did not cause the jury to believe it had to

be unanimous in finding mitigation. Petition at 26. Petitioners

are wrong. In Noland, the instructions included an express

unanimity requirement for aggravating circumstances (and the

sentence), but the word “unanimously” was not used on the

verdict form question regarding mitigating circumstances.

Thus, Noland does not undermine the Third Circuit’s finding

here because in Abu-Jamal, no distinction was made between

findings of aggravating and mitigating circumstances, and the

verdict form required that both be unanimously found.

37

II. This Court Should Deny Certiorari Because

Petitioners’ Quarrel Is with the Third

Circuit’s Application of Properly Stated

Rules of Law to the Facts of this Case.

Certiorari “is rarely granted when the asserted

error consists of . . . the misapplication of a properly

stated rule of law.” Supreme Court Rule 10. Here,

the Third Circuit applied “properly stated rule[s] of

law” to the facts of this case for both the

constitutional merits of the Mills claim and the

deference due state court decisions under AEDPA.

It is undisputed that the applicable rule of federal

constitutional law is derived from Mills v. Maryland,

“in light of Smith v. Spisak.” Abu-Jamal-5, 130 S.

Ct. at 1134. The Third Circuit expressly recognized

that Mills and Spisak set forth the applicable

constitutional rule; applied Mills and Spisak to the

facts of Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case; and applied no other

substantive law or lower court interpretations of

Mills or Spisak. See supra Section I. A.

It is also undisputed that the applicable rule of

deference under AEDPA is 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1), as

interpreted by this Court. The Third Circuit

expressly recognized that § 2254(d)(1) sets forth the

applicable rule of deference; acknowledged this

Court’s interpretations of § 2254(d)(1) in cases such

as Williams, 529 U.S. 362 and Landrigan, 550 U.S.

465; and applied these deferential standards to this

case. See supra Section I. A.

Because the Circuit clearly identified and applied

the correct rules of constitutional law and § 2254(d)

deference, Petitioners’ request for certiorari review

should be denied.

38

III. This Court Should Deny Certiorari

Because the Circuit Court’s Grant of Mills

Relief is Unlikely to Affect Future Cases.

This Court grants certiorari in order to review

“question[s] of national importance.” Grutter v.

Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 322 (2003). This is not such

a case because the error is unlikely to affect future

cases.

For several reasons, very few Pennsylvania

capital cases are eligible for Mills relief under

Respondent’s circumstances:

First, over 22 years ago - in February 1989 -

Pennsylvania’s courts stopped using the verdict

forms and jury instructions now at issue. And, in

response to Mills, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

promulgated a new standard verdict form and jury

instructions that are MiZZs-compliant. See Abu-

Jamal-6, 643 F.3d at 382-83.

Second, the applicability of Mills is limited by the

anti-retroactivity rule of Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S.

288 (1989). Because Mills announced a “new rule,”

it is only available to habeas petitioners whose

convictions became final after this Court decided

Mills on June 6, 1988. Beard v. Banks, 542 U.S. 406

(2004).

Thus, in order for another prisoner to benefit

from the Circuit’s decision, the case cannot be “too

new” — it had to be tried before Mills, or at least

before the official change in the verdict form on

February 1, 1989. This eliminates every case tried

in the last 22 years. At the same time, the case

cannot be “too old” - it had to be final after Mills.

This also eliminates a significant body of cases.

39

Third, to benefit from the Circuit’s decision a

Mills claim must survive all other habeas-related

barriers, such as the exhaustion requirement and

procedural default rules. Very few cases could

survive this filtering and properly present the issues

on which Petitioners seek review. Few if any are

likely to present themselves to the Third Circuit in

the future.

Finally, the limited relevance of Mills error in

Pennsylvania is reflected by the decisions of the

Third Circuit. Apart from Respondent’s case, the

Third Circuit has addressed Mills claims in only

eight other Pennsylvania capital cases: Zettlemoyer,

923 F.2d at 306-08; Frey, 132 F.3d at 920-25;

Szuchon v. Lehman, 273 F.3d 299, 320-24 (3d Cir.

2001); Hackett, 381 F.3d 281 (3d Cir. 2004); Albrecht

v. Horn, 485 F.3d 103, 116-20 (3d Cir. 2007); Fahy u.

Horn, 516 F.3d 169, 175-76 (3d Cir. 2008); Banks v.

Horn, No. 99-9005 (3d Cir. Aug. 25, 2004); and

Kindlier v. Horn, 542 F.3d 70, 80-83 (3d Cir. 2008),

vacated and remanded on other grounds, 130 S. Ct.

612 (2009).

In six of these cases — Zettlemoyer, Szuchon,

Hackett, Albrecht, Fahy, and Banks - the Third

Circuit denied relief on the Mills claim. In three of

these cases - Banks, Albrecht, and Fahy - the

Circuit found that the Mills claim was barred by

Teague. In one — Szuchon — the Circuit held that the

Mills claim was procedurally defaulted. In two, the

Circuit denied the Mills claim on the merits — under

pre-AEDPA de novo review in Zettlemoyer and under

AEDPA's § 2254(d) in Hackett.

40

In just two of the eight cases, Frey and Kindler,

did the Third Circuit grant relief under Mills. In

both cases, habeas review was de novo, not under

AEDPA’s § 2254(d). In Frey, the claim would have

been denied under Teague had Petitioners not

waived their Teague defense. 132 F.3d at 920 n.4.

Thus, the Third Circuit’s Mills decisions

highlight the limited availability of Mills relief in

Pennsylvania due to the above-described

combination of non-retroactivity under Teague, post-

Mills changes to Pennsylvania’s verdict forms and

jury instructions, and other procedural issues. The

rulings also show that even when the rare Mills

claim survives those obstacles, the Third Circuit

takes a nuanced approach that has led to habeas

relief in some cases and denial of relief in others.

Mr. Abu-Jamal’s meritorious Mills claim is,

therefore, a rarity even in Pennsylvania, and Mills

claims will scarcely ever be presented in future

cases. Accordingly, this Court should not waste its

rarely granted certiorari jurisdiction on this case.

CONCLUSION

41

For the reasons stated herein, certiorari

should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

John Payton

Director-Counsel

Debo P. Adegbile

^Christina A. Swarns

Johanna B. Steinberg

Jin Hee Lee

Vincent M. Southerland

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965.2200

cswarns@naacpldf.org

Judith L. Ritter

W idener University

School of Law

P.O. Box 7474

4601 Concord Pike

Wilmington, DE 19801

(302)477-2121

September 9, 2011 * Counsel of Record

mailto:cswarns@naacpldf.org

ADDENDUM

la

In the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia

Criminal Trial Division

(EXCERPTS)

January Term, 1982

Nos.

Commonwealth 1357 Poss Instru of Crime

Gen

vs. Poss Instru of Crime

Concealed Weapon

Mumia Abu-Jamal

1358 Murder

aka Voluntary Manslaughter

Wesley Cook 1359 Involuntary

Manslaughter

July 3, 1982

Courtroom 253, City Hall

Jury trial

Before: Honorable Albert F. Sabo, Judge

2a

Page 2.

THE COURT: Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, you

have found the defendant guilty of murder in the

first degree, and your verdict has been recorded.

We are now going to hold a sentencing hearing

during which counsel may present additional

evidence and arguments and you will decide whether

the defendant is to be sentenced to death or life

imprisonment.

Whether you sentence the defendant to death or to

life imprisonment will depend upon what, if any,

aggravating or mitigating

Page 3.

circumstances you find are present in this case.

Loosely speaking, aggravating and mitigating

circumstances are circumstances concerning the

killing and the killer which make a first degree

murder case either more serious or less serious. The

crimes code defines more precisely what constitutes

aggravating and mitigating circumstances. Although

I will give you detailed instructions later in this

hearing, I will tell you now that aggravating

circumstances must be proved by the

Commonwealth beyond a reasonable doubt, while

mitigating circumstances must be proved by the

defendant by a preponderance of the evidence.

Mr. McGill, are you ready to proceed?

3a

MR. MCGILL: Yes, your honor, if it please the court.

Your honor, the Commonwealth’s witness will be

Miss Pat Beato.

PATRICIA BEATO, (SWORN)