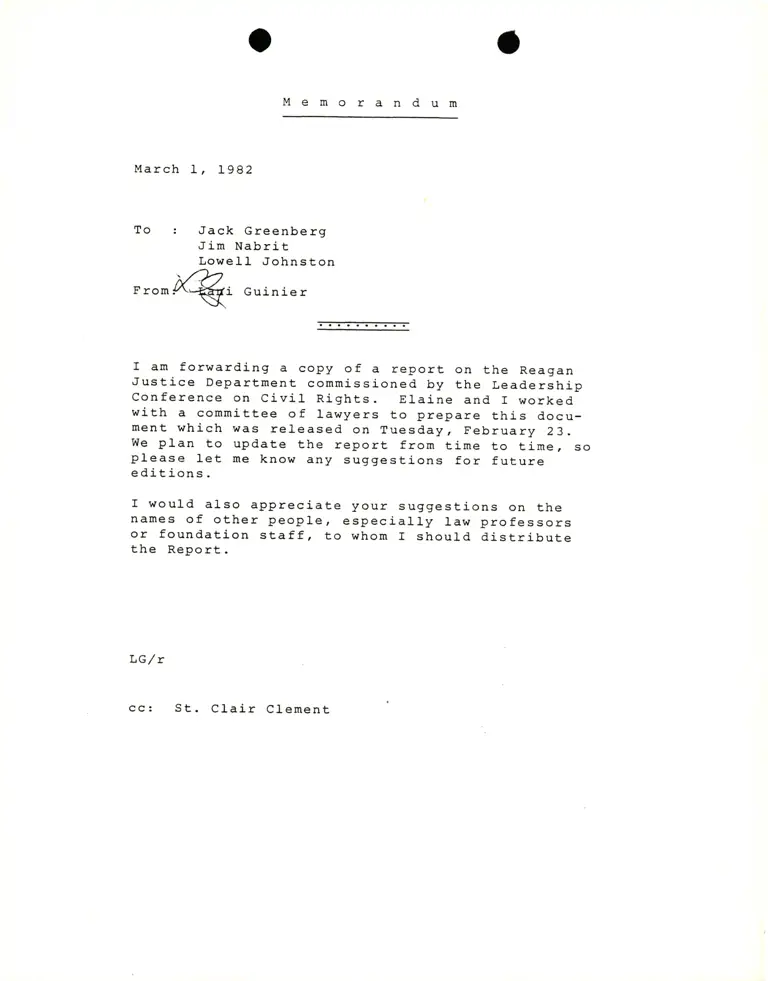

Memo from Lani Guinier to Greenberg, Nabrit and Johnston RE: Reagan Justice Department

Correspondence

March 1, 1982

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Memo from Lani Guinier to Greenberg, Nabrit and Johnston RE: Reagan Justice Department, 1982. e034d335-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/69eb5566-8590-48aa-aa1d-64c86dbd3e6f/memo-from-lani-guinier-to-greenberg-nabrit-and-johnston-re-reagan-justice-department. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Memotandum

March L, L982

: Jack Greenberg

Jin Nabrit

Lowel1 Johnston

To

From &, Gu'nler

I aa forwarding a copy of a report on the Reagan

Justice Department commissioned by the Lead,ership

Conference on Civil Rights. Elaine and I worked

with a committee of lawyers to prepare this docu-

nent which was released on Tuesday, February 23.

We plan to update the report from time to time r soplease let me know any suggestions for future

editions.

I would also appreciate your suggestions on the

names of other people, eapecially law professors

or foundation staff, to whom f should distribute

the Report.

LG/t

cc3 St. Clair Clement