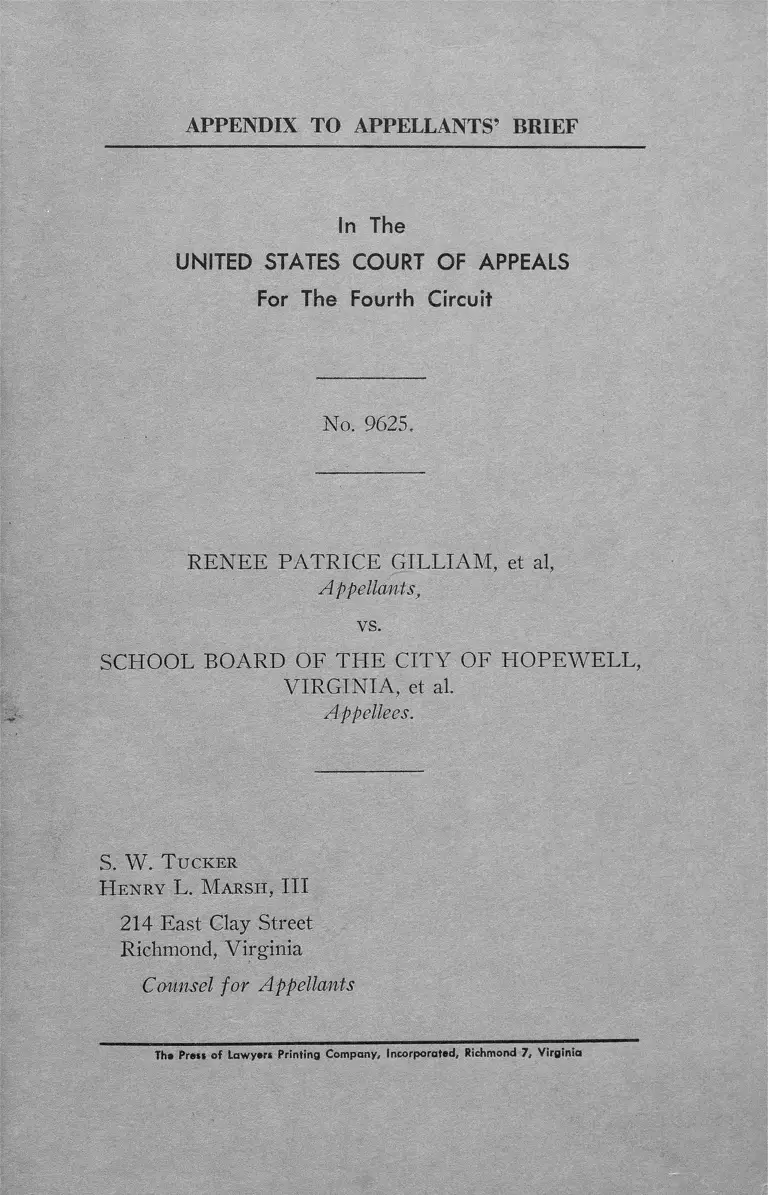

Gilliam v. City of Hopewell, VA School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gilliam v. City of Hopewell, VA School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1965. 82382f5f-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6a09a19f-46a4-4466-9f1f-e17259dc7934/gilliam-v-city-of-hopewell-va-school-board-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 9625.

RENEE PATRICE GILLIAM, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF HOPEWELL,

VIRGINIA, et al.

Appellees.

S. W. T u c k e r

H e n r y L. M a r sh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel for Appellants

The Press of Lawyers Printing Company, Incorporated, Richmond 7, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 8 (School Board Minutes of

October 6, 1960) ....................................................... 2

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 16 (School Board Minutes of

July 23, 1962) .............................................................. 4

Excerpts from Transcript of June 10, 1963 ................... 5

Order entered July 11, 1963 .......................................... 13

Memorandum of the Court filed July 11, 1963 ........... 14

Order entered September 13, 1963 ............................... 21

Ruling of Court delivered from bench September 12,

1963 .............................................................................. 22

Motion to Dismiss Injunction, filed October 22, 1963 .... 29

[First] Plan for Operation of Schools, filed October,

1963 ........................................................................... . 29

Exceptions to Plan, filed December 2, 1963 ............. ..... 32

Motion to Dismiss Injunction, filed June, 1964 .............. 34

[Second] Plan for Operation of Schools, filed June,

1964 .............................................................................. 35

Page

Exceptions to Plan, filed July 2, 1964 ........................... 38

Excerpts from Transcript of April 6, 1964 ......... ..... 39

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1-A, filed April 6, 1964 ................ 54

Ruling of the Court, April 6, 1964 ............................... 55

Affidavit of Charles W. Smith, with attached charts,

filed July 2, 1964 ....................................... .............. 60

Ruling of Court, July 2, 1964 ................................... . 66

Order, entered July 6, 1964 ......................................... . 70

Plaintiffs’ Notice of Appeal, filed July, 1964 ............... 71

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 9625.

RENEE PATRICE GILLIAM, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF HOPEWELL,

VIRGINIA, et al.

Appellees.

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

AN EXACT COPY

Plaintiff’s Exhibit Number 8

Minutes of the Regular Meeting

of the

City of Hopewell School Board

Thursday, October 6, 1960

8:00 P.M.

A map of the City of Hopewell showing present school

attendance areas, a proposed improvement and extension

2

of Palm Street and a proposed ten foot walkway connecting

Palm and Terminal Streets in order to afford an improved

walking route for school children from the Davisville Area

to the Carter G. Woodson School was presented and dis

cussed.

Since the construction of the above mentioned improved

walkway would involve securing a temporary easement

across firestone property, Mr. Broyhill and the Superin

tendent were appointed to conver with Mr. Walter Smith,

local Firestone Company Manager on this matter.

Following presentation of figures showing the number

of pupils now living in the Highland Park Area, grades 1

through 5, and information that a low cost housing project

was soon to be erected on Palm Street adjacent to the

Carter G. Woodson School, it was decided that the School

Board would meet with the City Council to propose the

construction of from 4 to 6 elementary classrooms at the

Carter G. Woodson School in which to house pupils grades

1 through 5 from these areas.

The following additional applications from pupils pres

ently assigned to the Carter G. Woodson and Harry E.

James Schools and apparently wishing to transfer to the

Hopewell High and Patrick Copeland Elementary Schools

were presented and discussed:

1. Applications from Carter G. Woodson to Hopewell

brought to School Board Office by Curtis Harris on

September 26, 1960

a. Curtis West Harris, Jr. 9th Grade

3

209 Terminal Street,

Hopewell, Va.

b. Corliss Maria Roberts 9th Grade

509 Davisville

Hopewell, Va.

c. Mary Alice Bradley 9th Grade

1007 Elm Street

Hopewell, Va.

d. Jacquelin Lefern 10th Grade

1301 Bland Court

Hopewell, Va.

2. Applications sent by registered mail to Patrick Cope

land School brought to School Board Office by Mr.

Harding on Wednesday, September 28th.

a. Mary Louise Jackson 6th Grade

307 Davisville, Hopewell, Va.

b. Faye Ernesting Moore 6th Grade

1301 Bland Court, Hopewell, Va.

c. Cheryl Lorrain Jackson 6th Grade

131 Terminal Street, Hopewell, Va.

Upon motion by Mr. Lee, seconded by Mr. Carrel, and

carried 4 to 1, Mrs. Beach voting No, the Superintendent

was instructed to forward these applications to the State

Pupil Placement Board at Richmond without recommenda

tions.

4

Plaintiff’s Exhibit Number 16

AN ENACT COPY

Minutes of the Regular Meeting

of the

City of Hopewell School Board

Monday, July 23, 1962

8:00 P.M.

The Superintendent reported that He, Dr. Hunter, and

Mr. Doeg had met with the State Pupil Placement Board

at Richmond, Virginia, on Wednesday, June 27, 1962 at

which time all applicants for transfer to a school other

than the one to which they had been assigned were denied

and that these applicants had been informed individually

and in writing by the Placement Board of both the de

cision and of reasons for the individual denials.

Subsequently the following seven applicants informed

the Place Board that they wished to protest these decisions

and had requested a hearing before the Board:

1. William Lewis Johnson, Jr., 522 Water Street, from

10th Grade at Carter G. Woodson School to 11th

Grade at Hopewell High School.

2. Helen Marie Wyche, 1101 Maplewood Avenue, from

7th Grade at Harry E. James School to 8th Grade

at Hopewell High School

3. Curtis West Harris, Jr., 209 Terminal Street, from

10th Grade at Carter G. Woodson School to 11th

Grade at Hopewell High School

4. Kenneth Charles Harris, 209 Terminal Street, from

9th Grade at Carter G. Woodson School to 10th

Grade at Hopewell High School

5

5. Faye Ernestine Moore, 1301 Bland Court, from 7th

Grade at Harry E. James School to 8th Grade at

Hopewell High School.

6. Christiana Delores Hall, 1603 Tabb Street, from

9th Grade at Carter G. Woodson School to 10th

Grade at Hopewell High School

7. Corliss Maria Roberts, 1702 Tabb Street, from 10th

Grade at Carter G. Woodson School to 11th Grade

at Hopewell High School

A tentative date for these hearings had been set by the

Placement Board for August 17th.

Following a discussion of this matter it was agreed that

the Superintendent would arrange for a meeting of the

Board with the Hopewell City Council as soon as possible

to inform the Council of developments to date.

EXCERPTS FROM TRANSCRIPT OF JUNE 10, 1963

ik ^

(tr. g) * * *

CHARLES W. SMITH, a defendant, called as a wit

ness by the plaintiffs, being first duly sworn, testified as

follows:

(tr. 12) * * *

BY MR. MARSH:

Q. Throughout the entire time of your services as Su

perintendent, have these boundaries ever been fixed so as

6

to permit Negro children to attend schools of white chil

dren, sir?

A. Not deliberately, no.

Q. What about accidently?

A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. Or have they been fixed so as to permit white chil

dren to attend schools with Negroes?

A. Not to my knowledge.

* * *

(tr. 27) * * *

Q. My first question is with reference to the students

who were to use that walkaway, sir. Were these students

all Negro students?

A. Yes.

Q. And this walkaway was built so that they would be

able to get to two different Negro schools?

A. It was built—it was built in order that students living

in the Harry E. James area would have a better walking

route to the Carter G. Woodson High School.

Q. Would you demonstrate on the map, sir, first, the

area where the students were residing?

A. (Indicating) This is the Harry E. James School

right here, and the students resided in this area, which is

shaded light yellow, and the walkaway—this is Terminal

Street coming right down in front of the Harry E. James

School. Formerly the students had to walk around here

like this, down to Palm Street and down Palm Street to

the Carter G. Woodson School.

We knew that the City was planning to extend Palm

Street and to change it, and we—in order to get a better

walking route to the school, we secured a right-of-way

7

across this property here joining Terminal Street with

(tr. 28) Palm Street in order that the children would

have a better way to get to school.

Q. Would you identify this school here, sir?

A. This school here?

Q. Yes.

A. That is the Patrick Copeland Elementary School.

Q. And this area here indicates that Negro parents are

living here, sir, Negro children?

A. That is true. That shows that the people living in

this area are zoned into this school.

Q. And this area here indicates that these are—

A. All shaded in light yellow goes to that school.

Q. This walkaway here made it easier for all these stu

dents to get to the Carter G. Woodson High School?

A. Yes, I would think it would.

Q. Without the walkaway, these students would have

been closer to the Hopewell High School ?

A. Not to my knowledge. They could or could not be.

The main purpose of this was to establish a walking route.

We didn’t have this particular group in mind. We were

thinking about the people here; to get across here.

Q. Are you saying, sir, that a student living here

wouldn’t be closer to Hopewell School than he would to

Carter G. Woodson without the walkaway?

A. I can’t testify to that. I don’t know.

* * *

8

(tr. 44 ) ̂ ̂ ^

E. J. OGLESBY, called as a witness by and on behalf

of the plaintiffs, having been first duly sworn, testified

as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

(tr. 45) BY MR. TUCKER:

Q. For the record, would you state your name and your

official connection with the Pupil Placement Board?

A. I am E. J. Oglesby, a member of the Pupil Place

ment Board.

Q. The composition of the Pupil Placement Board at

the time these applications in this case were considered is

the same as it is today, is that correct?

A. That is correct.

Q. You are—strike that. We know that some of the

applications in this case were refused, and the reason as

signed in one instance was outside the long established

attendance area. I ask you if your Board had anything to

do with the establishment of these attendance areas.

A. No, we accepted, as reasonable, a plan showed us

by Hopewell, which they said had been in existence for

a long time.

Q. I ask you if your Board has any plan or purpose of

revising the attendance areas in the City of Hopewell?

A. Only in the sense that from now on, in the future,

this Board expects to put everybody in each attendance

area, regardless of race, in the school in that area.

(tr. 46) Q. That wasn’t my question. My question was

if your Board has any plan or purpose of revising the

attendance areas.

9

A. No.

Q. One of the reasons, I see, a child was assigned was

a failure to follow established procedures. Am I correct in

assuming that you were referring to the procedures of the

School Board?

A. That is correct.

Q. And that was a decision that you made on August 14

1962?

A. Wherever we have had—that would be appeal date,

wouldn’t it? No, the date we agreed that we were going

to accept their procedures was when we originally went

over the applications. I believe the date you quoted would

be the date when we had a hearing on some appeals about

a decision we made earlier, but their local procedures, with

respect to who got the applications, where they got them,

and what they did with them, were reasonable adminis

trative procedures, and were accepted by us as being

reasonable procedures.

Q. The determination on the part of your Board that

these procedures had not been followed was a determination

made after the protest hearing, was it not?

A. Not in my recollection. My recollection was that

those were the reasons—part of the reasons given by us,

(tr. 47) the Board, in the placements we made when we

first went over those in June.

Have I made myself clear?

Q. In other words, the reasons assigned for the denial

was a part of the letter of June 27, where you did not

make the placements requested?

A. Yes. The decisions as to why they were put where

they were, were made when we went over the applications

in June. I don’t remember the date.

10

Q. All right. Now we have as a reason also, a distance

of residence from school. As that applies in the City of

Hopewell, it works out that the distance from residence of

school was something that was considered when the Negro

high school students were making application to attend the

Copeland High School, is that correct—or the Hopewell

High School?

A. Actually, I think what we did was give four or five

reasons; whereas one or two reasons were the deciding

things, the administrative procedures, and the question

whether it came in on time, and the attendance district.

Q. Well, as it works out, as long as a white child wanted

to attend the Hopewell High School, a Negro child wanted

to attend the Carter Woodson School, the distance of

residence from school would not matter ? Is that correct ?

A. That is probably correct, except that from now on,

(tr. 48) in those two districts, they are going to go to

those schools regardless of distance.

Q. I am speaking about what was the situation in June

of 1962, when you were considering these, and you con

sidered the distance of the residence of the Negro child

to the Hopewell High School, but you had no parallel con

sideration of the distance of the residence of the white

child.

A. Only because we didn’t have any applications of

that sort.

Q. So it works out, such, that any time you had occasion

to apply that criteria, it was when a child of one race made

application to attend the school for the children of the

other race?

A. I don’t know why that matter of living closer to the

Woodson School was mentioned in there, because it had

nothing to do with the decision.

21

Q. But it was mentioned?

A. It was mentioned in one or two of the letters, be

cause I was looking them over a few minutes ago, and read

that it was.

Also, educational qualifications were mentioned in one

or two cases. As was pointed out, that child was not quali

fied to go to the school he has applied to, but it wasn’t used

as a part of the decision, because, by then, we knew that we

(tr. 49) couldn’t.

Q. So that now what you are saying is that your only

basis for refusing these applications was the zone basis?

A. The zone basis and the lack of following what seemed

to be perfectly reasonable local administrative procedure

in connection with how blanks were handled, and I believe

in one case—two cases—I’m not sure, but I will have to

look it up—where they did not turn them in on time, they

used proper blanks.

Q. Now on this procedure, in June, was there any evi

dence presented to the Board as to what was this local

procedure, or is it not a fact—

A. It was. It is just that I have forgotten. I don’t have

it written down, and I have forgotten just exactly what

that procedure was. The evidence was it should come from

the people on the local level, because we, as a Pupil Place

ment Board, handle that all over the State. They handle

it locally, and it differs from place to place. It seemed to

be reasonable. What I mean by “differs” is this: one school

system may say these blanks must be gotten from the

school where the child is going; somebody else may say

it has got to be gotten from the school to which the child

is going. As long as it is a reasonable procedure made

known to everybody, we are willing to accept it as a way

of carrying out the details of this procedure.

12

Q. But minutes have been put into evidence here today,

(tr. SO) minutes of August 13 meeting, showing that on

that date they adopted—the School Board adopted a pro

cedure for the 1962-63 school session. Are you aware of

that fact?

MR. SCOTT: If Your Honor please, Mr. Oglesby is

not bound by any minutes of the local School Board.

FITE COURT: The question isn’t whether he is bound

by them. The objection is overruled.

A. Well, I will try to answer it. We were told it was a

local procedure. At the time we first went over this thing,

it was explained to us. W'e believed it was reasonable.

What may have happened in the way of changing that

first decision to the latter, I don’t know. That had nothing

to do with these decisions we made.

Q. As a matter of fact, you did not, then, know, and

do not yet know, that there was any procedure adopted

prior to August 13, 1962?

A. Oh, yes. I am sure that we acted on the procedure

we were told about by the local people in June.

Q. That was verbally? You were told that by word of

mouth ?

A. They did not bring the minutes to us and show us

that they had adopted minutes. They said, “This is the

procedure.” It seemed a reasonable procedure. They did

not present us with any written rules outlining that pro-

dure. I don’t remember whether they were written or not,

(tr 51) but they were made very clear to us, and they

had not been lived up to.

Q. So you don’t even know whether that procedure

that you had in mind in June of 1962, had been disseminated

13

to the people of Hopewell of not ?

A. No, I do not.

* * *

ORDER

[Entered July 11, 1963]

All matters of law and fact having' been submitted to

the Court; upon consideration whereof, for reasons ap

pearing in the Memorandum of the Court this day filed,

the Court doth ADJUDGE, ORDER and DECREE as

follows:

1. The defendants, and each of them, their successors

in office, agents, servants and employees, and those persons

in active concert or participation with them who receive

actual notice of this order, are enjoined and restrained

from denying the plaintiffs, and each of them, admission

to the public schools for the 1963-64 school session to

which application has been made, as set forth in Schedule A

of the complaint.

2. The defendants, and each of them, their successors

in office, agents, servants and employees, and those persons

in active concert or participation with them who receive

actual notice of this order, are enjoined and restrained from

the further use of racially discriminatory criterion, includ

ing the use of the present attendance areas, in the assign

ment of pupils to public schools in the City effective with

the beginning of the 1963-64 school session.

3. The School Board of the City of Hopewell and the

Division Superintendent of Schools, however, are granted

leave to file with the Court within 90 days a plan to provide

14

for immediate steps to terminate discriminatory practices

in the assignment of pupils to the schools in the City. If

a plan is submitted and approved, the injunction mentioned

in paragraph 2 of this order shall be suspended and the ad

mission of Negro students may be in accordance with the

plan.

4. The plaintiffs’ motion for counsel fees is denied.

Defendants shall pay the costs incident to the prosecution

of this case.

5. This cause is retained on the docket.

Let the Clerk send copies of this order and the Memo

randum of the Court to counsel of record.

/S / J o h n D. B u tz n er

United States District Judge

July 11, 1963

MEMORANDUM OF THE COURT

[Filed July 11. 1963]

Nine Negro students and their parents instituted this

action to require the defendants to transfer the students

from Negro public schools to white public schools. The

plaintiffs filed their suit as a class action on behalf of all

persons similarly situated and prayed that the defendants

be enjoined from denying any students admission to a

white school on the basis of race.

The defendants answered, generally denying that the

plaintiffs are entitled to the relief which they seek.

15

The City of Hopewell operates the following public

schools which are attended by white pupils:

Capacity A ttendance

Patrick Copeland Elementary 740 770

DuPont Elementary 870 832

Woodlawn Elementary 720 649

Hopewell High School 1,075 1,279

The City also operates the following schools which are

attended by Negro pupils:

Capacity A ttendance

Harry E. James Elementary 330 167

Arlington Elementary 270 395

Carter G. Woodson 300 286

Carter G. Woodson High School 350 257

The plaintiffs, who sought transfer to Hopewell High

School, were denied assignment primarily because they

lived outside the “long established attendance area”. As

signments to public schools in Hopewell are made accord

ing to geographical attendance areas. The Pupil Placement

Board usually makes formal assignment upon the recom

mendation of the City School Board.

The attendance areas for the several schools were estab

lished prior to the decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Minor changes have been made

from time to time. The areas follow the distribution of

Negro and white residences in the city. In some instances

the areas are defined by natural boundaries; in others there

is no distinction other than the racial composition of the

neighborhoods.

16

The attendance areas for Arlington School, Carter G.

Woodson School and Harry E. James School lie generally

south of the Norfolk and Western Railway tracks. The

Harry E. James School attendance area is bounded on the

west by the railway classification yard. The Seaboard Air

Line Railroad forms the boundary between Arlington

School and Carter G. Woodson School. The defendants

argue that for reasons of safety and convenience the tracks

form natural boundaries for these areas. Some of the Harry

E. James School attendance area lies to the north of the

tracks. A ravine isolates a part of this area from the

Patrick Copeland School area.

If the boundaries of the attendance areas had been lo

cated only with reference to the tracks and ravine, the

defendants’ argument would have considerable merit. How

ever, the tracks have not been used consistently as boun

daries. The same Norfolk and Western tracks bisect the

Woodlawn school attendance area. The Seaboard Air

Line tracks cross the DuPont School area. Portions of

the DuPont and Patrick Copeland school areas lie south

of the Norfolk and Western tracks, and part of the Harry

E. James School area lies north of the tracks. Also there is

no natural barrier between the Woodlawn School area and

the Arlington School area.

The capacity of the schools, compared with the attend

ance of the students, provides no rational criterion for the

boundaries which have been selected. For example, the

Patrick Copeland School has a capacity of 740 students,

with attendance of 770. Adjacent to this school area is the

Harry E. James School with a capacity of 330 but only

167 in attendance. Nevertheless a portion of the Patrick

Copeland School area flows across the railway tracks into

17

the Harry E. James School area. Hopewell High School

for white students has approximately 200 students over its

capacity. The Carter G. Woodson High School for Negro

students has approximately 100 students less than capacity.

On one occasion white students whose family moved into

a Negro lesidential area were enrolled in a white school

instead of the school which served the attendance area of

their residence. This was done, in part, because the family

intended to build a home in a white residential area.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300

(1955), the Court said:

While giving weight to these public and private

considerations, the courts will require that the defend

ants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such

a start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defendants

to establish that such time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date. To that end, the courts

may consider problems related to administration, aris

ing from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, revision

of school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission

to the public schools on a non-racial basis, and revision

of local laws and regulations which may be necessary

in solving the foregoing problems. They will also con

sider the adequacy of any plans the defendants may

propose to meet these problems and to effectuate a

18

transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school sys

tem. During- this period of transition, the courts will

retain jurisdiction of these cases.”

d his case falls within the language of Brown pertaining

to "revision of school districts and attendance areas into

compact units to achieve a system of determining admis

sion to the public schools on a nonracial basis.”

The racial composition of neighborhoods may result in

predominantly white or predominantly Negro school dis

tricts even after the areas have been reshaped to comply with

the mandate of Brown. This, in itself, would not be a badge

of unconstitutionality. Thompson v. County School Board

of Arlington County, Virginia, 204 F.Supp. 620 (E.D.Va.

1962). The existence of this situation was recognized in

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 808

F.2d 920 ( 4th Cir. 1962). The vice of the Charlottesville

plan was not the composition of its attendance areas. The

plan was invalid because of its unconstitutional provision

for the transfer of students who found themselves in a

racial minority. Goss v. Board of Education, 31 U.S.L.

Week 4559 (U.S. June 3, 1963).

The use of race to establish residential requirements for

school assignments has been held invalid in this Circuit.

In Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, Virginia,

304 F.2d 118, 122 (4th Cir. 1962), Chief Judge Sobeloff

wrote:

“This court has on several occasions recognized

that residence and aptitude or scholastic achievement

criteria may be used by school authorities in determin

ing what schools pupils shall attend, so long as racial

19

or other arbitrary or discriminatory factors are not

considered. See, e.g., Dodson v. School Board of City

of Charlottesville, Virginia, 289 F.2d 439, 442 (4th

Cir., 1961); Jones v. School Board of City of Alex

andria, Virginia, 278 F.2d 72, 75 (4th Cir., 1960).

But if these criteria, otherwise lawful, are used in a

racially discriminatory manner, the resulting assign

ment is not saved from illegality. As we have more

than once made clear, school assignments, to be con

stitutional, must not be based in whole or in part on

consideration of race.”

In Evans v. Buchanan, 207 F.Supp. 820, 824 (D. Del.

1962), the distinction between valid and invalid attendance

areas is clearly drawn:

“There have been many lower court decisions since

the Brown case held children may not be denied en

trance to public schools solely on the basis of race.

One of the teachings of these cases is that whether

Negro children are deprived of their constitutional

rights is a question of fact. Criteria such as trans

portation, geography and access roads are rational

bases for establishing public attendance areas or desig

nating school districts. If, however, these criteria are

merely camouflage and school officials have placed

children in particular districts solely because of race,

a cause of action under the Constitution exists.”

The Court concludes that the application of the fore

going principles to the facts in this case demonstrates that

the present attendance areas do not satisfy the requirements

set forth in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294,

300 (1955).

20

̂ The plaintiffs, who sought admission to Hopewell High

School, also were denied assignment to that school because

of the distance from their residences to the school. White

students were admitted to Hopewell High School regardless

of the distance of their residences from the school.

The Court concludes that the reasons assigned for de-

nying admission to the plaintiffs were constitutionally dis

criminatory.

1 hese students were also denied admission for failure

to follow established procedure. Two students seeking ad

mission to Patrick Copeland Elementary School were de

nied admission because they failed to apply on an official

blank. One application to Hopewell High School was “filed

too late . It is quite obvious, however, that the primary

reason that all students were denied admission was be

cause of the defendants’ rigid adherence to the long estab

lished attendance areas. Under these circumstances it is

well settled that failure to exhaust administrative remedies

is not a defense. McNeese v. Board of Education, 31 U.S.L.

Week 4567 (U.S. June 3, 1963); Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Virginia, No. 8944 (4th Cir June 29

1963).

The Court further concludes that a general injunction

should be granted against the school officials prohibiting

racial discrimination in the admission of students to schools

and from assigning students on the basis of the school

attendance areas currently existing. The defendants may

submit to the Court a more definite plan providing for

immediate steps looking to the termination of discrimina

tory systems and practices. Bradley v. The School Board

of the City of Richmond, Virginia, No. 8757 (4th Cir. May

10, 1963.)

21

The plaintiffs also pray that the defendants be required

to pay costs and attorneys’ fees. In Bell v. School Board of

Powhatan County, Virginia, No. 8944 ( 4th Cir. June 29,

1963), the Court of Appeals, pointing to “* * * the long

continued pattern of evasion and obstruction * * *” on the

part of the defendants, allowed attorneys’ fees. The Court

does not find that the same situation exists in this case, and

the prayer for attorneys’ fees is denied. Costs will be al

lowed.

/S / J o h n D. B u t z n e r , J r .

United States District Judge

July 11, 1963

ORDER

[Entered September 13, 1963]

Upon consideration of the plaintiffs’ motion for further

relief, the testimony, affidavits and exhibits presented Sep

tember 12, 1963, and upon the stipulation of counsel that

the Court shall grant or deny the permanent injunction at

this time without further proceedings; it is ADJUDGED

and ORDERED:

1. The defendants, and each of them, their successors

in office, agents, servants and employees, and those persons

in active concert or participation with them who receive

actual notice of this order, are enjoined and restrained

from denying the pupils mentioned in said motion, and

each of them, admission to the public schools to which

application has been made, as set forth in said motion, on

Monday, September 16, 1963, and thereafter.

22

2. The findings of fact and conclusions of law stated by

the Court from the bench after hearing the motion for a

temporary restraining order, are adopted by the Court as

the findings and conclusions for this permanent injunction.

3- On January 17, 1964 at 2:30 P.M., the Court will

consider the City of Hopewell’s plan for which provision

is made in «} 3 of the order of this Court entered July 11,

1963, the plaintiffs’ motion for counsel fees and costs and

all other matters which either party desires to present.

4. All further motions to be considered on January 17,

1964 must be filed prior to December 1, 1963.

5. The defendants shall file briefs on the proposed

plan on or before October 20, 1963. The plaintiffs shall

file exceptions to the plan and briefs thereon on or before

December 1, 1963. Counsel are requested to furnish op

posing counsel copies of briefs upon filing the same.

Let the Clerk mail copies of this order to counsel of

record.

September 13, 1963

/S / J o h n D. B u t z n e r , J r .

United States District Judge

RULING OF COURT

[Delivered from Bench September 12. 1963]

(tr. 41) * * *

THE COURT: Gentlemen, I am required by the Rules

to state findings of fact and conclusions of law, and I will

welcome any interruption by counsel if you find that I am

23

misstating any of the facts. As for conclusions, you will

have to appeal rather than interrupt them. They are my

responsibility. But 1 will appreciate counsel's help with

the facts.

The Court finds that prior to May 31, 1963, the following

children made application to attend Carter G. Woodson

School—

MR. GRAY: To attend Patrick Copeland School.

THE COURT: To attend Patrick Copeland School.

—Pamela Fay Satterwhite, Merthan Satterwhite, Dorrie

Satterwhite, Ronald Ivory Hayes, Joanne Harris, Steven

DuWayne Hayes, William Bolden Spratley, Jr., and

Patricia Jones.

Those applications were duly forwarded by the school

officials of the City of Hopewell to the Pupil Placement

Board of Virginia, and on August 15, the Board advised

the respective children that on August 12 it had met and

denied the applications because the residence of the child

is in the immediate proximity to the school in which he is

enrolled, or she is enrolled, and no students enrolled else

where were similarly situated.

The Court finds further that on August 27, without

(tr. 42) having made previous application to the Pupil

Placement Board, Cecelia Lynette Claiborne, Huey Bliz

zard, Addie Louise Hall, Barbara Ann Johnson, Carl

David Johnson, Barbara D. Wyche, and Audrey L. Wyche,

who were attending Carter G. Woodson School, sought

admission to Hopewell High School. They were permitted

to register, but were told that the assignment would have

to be approved by the Pupil Placement Board.

24

MR. GRAY: If Your Honor please, I question whether

they were permitted to register. The affidavit of the school

superintendent is to the effect that they did fill in some

preregistration forms, but they were not, in fact, registered.

I don’t know which way you want to find the facts.

THE COURT: I will accept that amendment. I think

that is pi obably what happened. They were not actually

registered or accepted into school; their names were taken.

MR. MARSH: Your Honor, my understanding is they

filled out the forms and even talked with their counsellors,

and that is why the affidavit was worded that way.

THE COURT: Well, I don’t think it is a material fact,

m any event. They ultimately, after conferring with the

local officials, were not admitted to the school; and the Pupil

Placement Board, acting upon Memorandum 34, declined

to enroll them at that school at a meeting on September 9.

MR. SCOT1 : If Your Honor please, without prejudice

(tr. 43) to their rights to apply—I think it says—in

timely fashion for the next school session.

THE COURT: Yes. The Court notes that the letter

which is in evidence did deny them without prejudice to

their right to apply prior to June 1 of 1964.

The Court finds that by Memorandum No. 34, the ap

plications must be filed with the local division superintendent

of schools prior to June 1.

The Court also finds that the children mentioned do live

closer to the schools to which the Pupil Placement Board

assigned them than to the schools to which they sought

entry.

The Court also finds that the School Board interpreted

the Court’s order of July 11, 1963, on the advice of counsel,

2 ,:

as permitting them to use geographic standards, or residen

tial standards which were not the same as those—in all

respects—as those the Court had held improper; but that

they would use geographic standards for the placement

of schools during the 1963-64 school term; and that those

geographic standards apply to both white and Negro

students.

The Memo No. 34, to which the Court has previously—

MR. GRAY: Your Honor, may I interrupt a minute.

It may not be clear. It may be what Your Honor intended. I

(tr. 44) hope that what I portrayed to the Court—the

affidavit portrays to the Court—is, not only must the areas,

as drawn, apply to both races, but that the areas, in being-

drawn, must be drawn without regard to race. It is not

only after they are established that they must be applied

without respect to race, but in establishing them must be

established without respect to race.

THE COURT: Well, I do not think it is material at

this time. That may come in when we got to the approval

of the plan. Suffice it to say that those areas which they did

use, they applied to both races. I am not approving or dis

approving the plan at this time.

MR. GRAY: Yes.

THE COURT: And nothing I say today has any bearing

on the merits of the plan because it is not before me, and

I have not studied it.

The Court also finds that the memo of the Pupil Place

ment Board, No. 34, has been applied during the 1963

year to both white and Negro children.

We come now to the conclusions.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

26

Circuit, in Bradley v. School Board, City of Richmond,

8757, decided May 10, 1963, said in part as follows, in

speaking of an injunction and of the plan, which is con

templated by their decision. On page 19 of the slip sheet,

(tr. 45) it is stated:

“As we clearly stated in Jeffers vs. Whitley, 309 F.2d

621, 629 (4th Cir. 1962), the appellants are not entitled

to an order requiring the defendants to effect a general in

termixture of the races in the schools, but they are entitled

to an order enjoining the defendants from refusing admis

sion to any school of any pupil because of the pupil’s race.

The order should prohibit the defendants conditioning the

grant of a requested transfer upon the applicant’s submis

sion to futile, burdensome or discriminatory procedures.”

Now, the two significant items are: First, they are

entitled to an order enjoining the defendants from re

fusing admission to any school of any pupil because of the

pupil’s race. And then the second about the discriminatory

administrative procedures.

The Court plainly said that if a white child is attending

a school, then a Negro child can attend that school.

Now, this is not under the plan. This is not speaking of

the State Pupil Placement Board, the general law. It is

speaking of the scope of an injunction.

It also said in regard to the administrative procedures

that they could not be discriminatory.

Now, discriminatory is a word which the Court very

(tr. 46) carefully used, and, possibly, is defined most care

fully in the Roanoke cases. I am confident that in using

the word “discriminatory” in this manner, they were re

ferring to the word as they applied it in this long list of

decisions pertaining to the schools.

27

Now, going on, they speak of the plan:

“If there is to be an absolute abandonment of the dual

attendance area and ‘feeder’ system—” The plan contem

plates these, but—“If there is to be an absolute abandon

ment of the dual attendance area and ‘feeder’ system, if

initial assignments are to be on a nondiscriminatory and

voluntary basis, and if there is to be a right of free choice

at reasonable intervals thereafter, consistent with proper

administrative procedures as may be determined by the

defendants with the approval of the District Court, the

pupils, their parents and the public generally should be

so informed.”

Well, they are speaking there of the plan, not the in

junction; and I think that is, possibly, where some confu

sion has crept into the matter in interpreting that.

Then they say:

“If, upon remand, the defendants desire to submit to

the District Court a more definite plan, providing for im

mediate steps looking to the termination of the discrimina-

(tr. 47) tory system and practices ‘with all deliberate

speed,’ they should not only be permitted but encouraged

to do so.”

Now, the Court believes that the language is very dear;

and as far as the Court knows, that is about the most re

cent expression on the injunction.

The injunction in this case restrained the further use

of racially discriminatory criteria, including the use of the

present attendance areas in the assignment of children to

the public schools in the City effective with the beginning of

the 1963-64 school session. The injunction did not condition

that upon prior application on May 31.

28

Now, possibly in this case it would be unnecessary, to

take up the May 31 deadline, because those who did apply

were denied; and as has been pointed out by the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and by this Court, if that

happens, those who don’t apply are treated as though they

would have been denied. So that is the reason we do not

have the May 31 deadline before us in actual full impact.

The Court is of the opinion that in view of the injunc

tion, in view of the language of the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit stating exactly what these injunctions

mean—and this injunction follows that language very

closely, although it does not quote it—that the children

whose names the Court has mentioned and who have sought

(tr. 48) admission to the schools, should be admitted to

the schools forthwith to which they have applied.

Now, as the Court pointed out in the Richmond case,

that does not mean the children could transfer in mid

term. We are talking about enrollment. And, as the Court

pointed out in the Richmond case, that does not mean that

the May 31 deadline is inapplicable in cases where there is

no injunction. The Court mentions this because the ruling

pertains to cases only where there is an injunction. The

Court wants counsel for the Pupil Placement Board to

understand that. The Board must have knowledge of the

ground rules which are changing rapidly.

The Court is not expressing any opinion of the May 31

deadline, if it is embraced in the plan, nor on the deadline

if there is no injunction. These questions are not before

the Court at all. The question before the Court is the in

junction without a plan. And the injunction is not condi

tioned by any prior applications. When a plan is submitted

and approved, why then the plan, of course, takes the place

of the injunction.

29

MOTION TO DISMISS INJUNCTION

The defendants, School Board of the City of Hopewell

and Charles W. Smith, Superintendent of Schools, submit

herewith a duly adopted plan for the operation of schools

in the City of Hopewell and respectfully move this Court

to dissolve the injunction entered against them herein.

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY

OF HOPEWELL and CHARLES

W. SMITH, SUPERINTENDENT

OF SCHOOLS

F red erick T. Gray

Of Counsel

PLAN FOR OPERATION OF SCHOOLS BY

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF HOPEWELL

[1] By order dated July 11, 1963, the Judge of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia, Richmond Division, granted leave to the School

Board of the City of Hopewell and the Division Superin

tendent of Schools to file with the Court “a plan to provide

for immediate steps to terminate discriminatory practices

in the assignment of pupils to the schools in the City.”

[2] In compliance with that order, the School Board of

the City of Hopewell and the Division Superintendent sub

mit the following report and plan:

[a] The School Board of the City of Hopewell has

adopted a policy that in the future all assignments to schools

in the City of Hopewell will be made solely on the basis of

30

residence without regard to race. This policy was put into

effect prior to the commencement of the 1963-64 school

year and is currently the policy of the School Board.

[b] The School Board has carefully reviewed its school

attendance areas in the light of the opinion of the District

Court and has prepared a new map of attendance areas

which is filed herewith as a part of the plan for the opera

tion of schools within the City of Hopewell. These at

tendance areas will become effective at the commencement

of the next school year in September, 1964.

[c] The School Board of Hopewell presently operates

six elementary schools, one of which is located in each of the

school attendance areas. The school attendance areas have

been set up as far as possible on the basis of natural

neighborhoods which in turn reflect actual geographical

boundaries such as railroads and major traffic arteries.

In establishing the areas, consideration was given to school

capacities and to present attendance and anticipated growth.

For example, in some zones the residental development

is complete with no land available for further expansion.

In such zones the full capacity of the schools can be utilized.

In other zones there is considerable land available for ex

pected residential growth and schools in such zones may

not be currently used to capacity as they were designed to

meet future growth.

[d] The School Board operates two high schools. As

signments to the respective high schools will be determined

strictly in accordance with residence. High school students

living in the zone for Arlington, Carter Woodson and

Harry E. James Elementary Schools will be assigned to

Carter Woodson High School. High school students living

31

in the zone for Patrick Copeland, DuPont and Woodlawn

Elementary Schools will be assigned to Hopewell High

School.

[e] In the past the School Board has on occasion been

requested to permit a particular child to transfer from the

school to which he was assigned by virtue of residence for

some specific reason. As an example, one mother was em

ployed at a school outside the school zone in which she

resided. The child had a physical handicap and the mother

preferred to transport the child to and from school. As a

matter of convenience to the family a transfer to the school

at which the mother was employed was granted. The Board

will consider such applications in the future, but the race

of the applicant will not be regarded as a factor in the

granting or refusal of such transfers.

[f] Notwithstanding the provisions of the above para

graph, it is the opinion of the School Board that in some

instances it would not be to the best interest of the health

and welfare of children of the colored race and would in

fact be detrimental to their educational advancement to

require them to attend a school in which they might by

reason of residence be in the racial minority. The School

Board, therefore, has adopted as a severable portion of this

plan of operation a provision that should the parents of

any colored child, assigned by reason of residence to a

school in which he is in the racial minority, be of opinion

that such assignment is detrimental to the health, welfare

or educational opportunity of such child application for

transfer may be made and if the School Board concurs

in the opinion of the parent, transfer will be permitted. If

the Court be of opinion that this provision is unconstitu

tional or violative of the Court’s injunction, then its elimina-

32

lion shall not affect the operations of the remainder of the

plan.

[3] Under applicable provisions of Virginia law, ap

proval of this plan by the Virginia Pupil Placement Board

is required. The School Board has been assured that it can

expect approval of the proposed plan by the Pupil Placement

Board if the plan meets with the approval of the Court.

EXCEPTIONS TO PLAN

(filed December 2, 1963)

Plaintiffs, by their attorneys, respectfully object to the

plan filed in this cause by the School Board of the City of

Hopewell and Charles W. Smith, Division Superintendent

of Schools.

For convenience, the plaintiffs supply numerical and

alphabetical designations to the several paragraphs of this

document captioned PLAN FOR OPERATION OF

SCHOOLS BY SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

HOPEWELL, viz: on the first page thereof 1,2, (a), (b),

(c), on the second page thereof (d), (e), and on the third

page thereof (f), 3. The plaintiffs specify the following

as their grounds of objection:

1. The provisions of the paragraph designated (a) are

contradicted by the paragraphs designated (e) and ( f ) ;

there being nothing in the history of the school system or

in the history of this litigation to lead one to believe that

the provisions of the paragraph designated (e) will be

applied to permit a Negro child to attend a predominantly

white school or a white child to attend a predominantly

Negro school or that they will not be applied to permit a

33

white child to escape assignment to a predominantly Negro

school. The paragraph designated (e) confers on the school

administration unlimited discretion to transfer pupils, in

cluding racially determined transfers, thus rendering the

caveat against racial discrimination meaningless.

2. The paragraph designated (f) is patently unconstitu

tional, as the defendants recognize.

3. The map referred to in the paragraph designated

(b) is not a new map but merely represents an attempt to

continue the discrimination previously enjoined by the

Court in an order entered on July 11, 1963.

The attendance areas referred to in the paragraph de

signated (b) have not been revised with the end of achiev

ing a system of determining admission to the public schools

on a non-racial basis; rather they have been adjusted with

the end of achieving the opposite result.

4. The paragraph designated (d) merely provides for

a “feeder system” to perpetuate racial segregation.

5. Furthermore, the plan as a whole is inadequate in that

it fails to make provision for assignment or reassignment

of teachers and other professional personnel on a non-

racial basis and for the elimination of the present practice

of assigning such personnel on a racial basis. In this con

nection plaintiffs assert their personal rights to attend a

school system in which there is no racial segregation and

discrimination.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray that the Court enter an

order:

34

1. disapproving the plan submitted by the defendants

on the ground that it is inadequate and invalid under the

Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment;

2. directing the defendant Board to promptly submit

a new alternative, or amended plan within a specified time

period;

3. granting the relief prayed in the Complaint and such

other and further relief as the Court may deem just and

proper.

H en r y L. M a r sh , III

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

MOTION TO DISMISS INJUNCTION

The defendants, School Board of the City of Hope-

well and Charles W. Smith, Superintendent of Schools,

submit herewith a duly adopted plan for the operation of

schools in the City of Hopewell and respectfully move this

Court to dissolve the injunction entered against them

herein.

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY

OF HOPEWELL and CHARLES

W. SMITH, SUPERINTENDENT

OF SCHOOLS

F retjerick T. Gray

Of Counsel

35

PLAN FOR OPERATION OF SCHOOLS BY

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF HOPEWELL

I

By order dated July 11, 1963, the Judge of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Vir

ginia, Richmond Division, granted leave to the School Board

of the City of Hopewell and the Division Superintendent

of Schools to file with the Court “a plan to provide for

immediate steps to terminate discriminatory practices in

the assignment of pupils to the schools in the City.”

II

In compliance with that order, the School Board of the

City of Hopewell and the Division Superintendent submit

the following report and plan:

III

The School Board of the City of Hopewell has adopted

a policy that in the future all assignments to schools in the

City of Hopewell will be made solely on the basis of resi

dence without regard to race. This policy was put into effect

prior to the commencement of the 1963-64 school year and

is currently the policy of the School Board. It will be the

policy under this Plan.

IV

Effective at the commencement of the next school year

in September, 1964, school attendance areas in Hopewell

will be as outlined on the map of attendance areas filed

36

herein on October 21, 1963. Assignment to elementary

schools will be made solely on the basis of residence with

out regard to race and each child eligible for attendance

in an elementary school will be initially assigned to the

school zone which embraces his residence. Any such child

residing in the zone for either the Arlington or the Wood-

lawn Elementary Schools whose residence is nearer an ele

mentary school in a zone other than the zone which embraces

his residence shall be entitled, upon application properly

made under the procedures of the State Pupil Placement-

Law, to' transfer to the school nearest his residence. For the

first year of this Plan such applications must be filed with

in thirty (30) days of the approval of this Plan by the

Court. In subsequent years, applications must be made

within the time prescribed for Pupil Placement Applica

tions.

V

The School P>oard operates two high schools. Assign

ments to the respective high schools will be determined

strictly in accordance with residence. High school students

living in the zone for Arlington, Carter Woodson and

Harry E. James Elementary Schools will be initially as

signed to Carter Woodson High School. High school

students living in the zone for Patrick Copeland, DuPont

and Woodlawn Elementary Schools will be initially assigned

to Hopewell High School. Any high school child whose

residence is nearer a high school other than the one to

which he is initially assigned on the basis of residence shall

be entitled, upon application properly made under the pro

cedures of the State Pupil Placement Law, to transfer to

the school nearest his residence. For the first year of this

Plan such applications must be filed within thirty (30) days

37

of the approval of this Plan by the Court. In subsequent

years, applications must be made within the time prescribed

for Pupil Placement Applications.

VI

In the past the School Board has on occasion been re

quested to permit a particular child to transfer from the

school to which he was assigned by virtue of residence for

some specific reason. As an example, one mother was

employed at a school outside the school zone in which she

resided. The child had a physical handicap and the mother

preferred to transport the child to and from school. As a

matter of convenience to the family a transfer to the school

at which the mother was employed was granted. The Board

will consider such applications in the future, but the race

of the applicant will not be regarded as a factor in the

granting or refusal of such transfers.

VII

Under applicable provisions of Virginia law, approval

of this Plan by the Virginia Pupil Placement Board is

required. The School Board has been assured that it can

expect approval of the proposed plan by the Pupil Place

ment Board if the Plan meets with the approval of the

Court.

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY

OF HOPEWELL

F red erick T. Gray

Of Counsel

38

EXCEPTIONS TO PLAN

(filed July 2, 1964)

Plaintiffs, by their attorneys, respectfully object to the

amended plan filed in this cause by the School Board of

the City of Hopewell and Charles W. Smith. Division

Superintendent of Schools.

1. Inasmuch as the plan of June 4, 1964, adopts with

certain modifications the plan previously filed with this

Court by the school board, plaintiffs adopt their exceptions

previously filed on December 2, 1963, as exceptions to this

amended plan to the extent that they are applicable.

2. Plaintiffs object to paragraph IV of the amended plan

as it fails to eliminate the irregular boundary between the

Arlington and Woodlawn zones. This provision merely

facilitates the continued existence of the segregated

character of these two schools.

3. Paragraph V of the amended plan continues the feeder

system of schools for the high schools in the City of Hope-

well. This provision places the burden of escaping from

this “feeder system” on the parents of the Negro child.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray that the amended plan

be disapproved.

H en r y L. M a r sh , III

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

39

EXCERPTS FROM TRANSCRIPT OF APRIL 6, 1964

* >K *

(tr. 2) * * *

CHARLES W. SMITH, called as a witness by and on

behalf of the defendants, being first duly sworn, testified as

follows:

BY MR. GRAY:

Q. Mr. Smith, would you come over to the map, please,

so that you can orient yourself.

(Witness stepped to map.)

His Honor had asked you while you were on the stand

before to explain the selection of the boundary line be-

(tr. 3) tween the Arlington School area, which is in the

green, and the Woodlawn School area, which is in the

blue; and you had explained, to some extent, the reason

for the selection of Wall Street.

Now, I want to go back to that for just a moment and

ask you, because it is not clear to me, and I am certain it

is not clear to the Court, is Wall Street going to go into

Palm Street as Palm Street is being relocated and im

proved? Will it flow directly into Palm Street?

A. Wall Street will not go directly into Palm Street as

is now' being constructed. It was first thought that it

would, but it will not go directly.

Q. What is going to be the traffic situation from Wall

Street going into, around Palm Street ?

A. Wall Street will end at this street here, which is

designated as Tinsley.

40

THE COURT: Just a minute, please, so I can follow

on the map.

All right, sir.

A. It will terminate at the—

THE COURT: What was the street you were referring

tO'?

THE W ITNESS: Talking about Wall. Wall Avenue,

and later it is Wall Street down near the area of Kolar

(tr. 4) Street.

THE COURT: Yes, sir.

THE W I1NESS: Now, Wall Avenue will terminate

at Tinsley. The street or avenue that is shown there, but

actually, Tinsley Avenue is undeveloped. It is non-existent.

Now, it is my understanding that Tinsley will be open

probably down to Palm, but the natural flow of traffic from

any one leaving from Kolar Street over to Palm, and there

are a good many houses right in there, would be back to

Kolar Street, down Kolar Street to Palm.

BY MR. GRAY:

Q. Well, for people living on Wall Street, what will be

the natural traffic movement for people on that street, even

if they were going west in the city?

A. Probably down to Arlington Road.

Q. Why is that true? Does Wall Street go through in

either direction?

A. Wall Street is not a through street, neither going

towards Tinsley, nor is it a through street coming back

41

towards, say, Granby and Trenton Street. It is sort of a

half street there.

Q. All right, sir. So it is your conclusion that the people

(tr. 5) living to the east of Wall Street, the natural move

ment on that would be to flow down into Arlington Road ?

A. To Arlington Road, because to that, is a hilly situa

tion. It is an uphill proposition going up.

Q. All right, sir. Now, what is the character of the land

lying to the northwest, directly to the northwest of Wall

Street ?

A. Directly to the northwest is an undeveloped area which

is marked by showing the ends of these streets, Pine, and so

on, coming over to meet, and by, Palm Street, improved,

which will go up through that.

Q. Well, is it—

i\. Excuse me.

Q. Is it flat country, or what is it ?

A. It is a ravine. Hilly down in there, and it is flat along

side Palm, but getting towards this, it’s a ravine.

Q. Now, Mr. Smith, with respect to before you get over

to the Wall Street area between the green and the blue,

but as Court House Road swings into Berry Street, why did

not the School Board determine to have the area of Arling

ton School come over across Court House Road into this

blue section, which seems to jet down into the green area?

A. Well, we didn’t do that for the reason that old Court

House Road, turning into Berry Street down near the

(tr. 6) Arlington School seems to be a natural boundary

line. It is the city-county line, and then it runs into Berry,

and from the Arlington School, about the location of the

Arlington School over into this way, and down into Arling

ton—down to Arlington Road there is a very heavily popu

42

lated area which would completely overrun this school had

we taken it in.

Q. Now, what is the size of the school?

A. This school has nine classrooms. Figure 30 to a class

room, would be 270.

Q. All right. Have you, since our last—since you last

testified, have you made any count of the houses in any

part of this area over here to try to estimate what it would

do to the school population?

A. Yes, I have. To my general knowledge, it was true

that this was a very heavily populated area in here, but

to verify that, I have made a count of the houses existing in

there from Roanoke Street down to Pine and over to

Granby.

Q. From Roanoke down to Pine and going north to

Granby ?

A. Down to Granby.

THE COURT: Let me see, where is Roanoke?

THE WITNESS: Could you show him?

MR. GRAY: Could I ?

It is just six streets coming—

(tr. 7) THE WITNESS: Off Berry Street.

MR. GRAY: Here, Your Honor (indicating).

THE WITNESS: About 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 streets up, north.

THE COURT: I found it. Roanoke. And what was

the other ?

MR. GRAY: And Granby would be the third street in.

THE W ITNESS: Over to Granby and down Granby

43

to Arlington, to Pine Street. There are 117 houses in that

area, by count—by actual count.

BY MR. GRAY:

Q. And what would you, from your general knowl

edge of the student population in this type of area, what

would you estimate to be the average number of students ?

A. Well, I think, naturally—it is a count of one and a

half students to the house, but in this area, it would run

closer to two. Two students to the house.

Q. All right, sir. Now, is there any other feature, for

example if you had attempted to use, let’s say, High

Street or Tabb Street, instead of Wall Street, and go

across to; Palm, what exists here at the corner of High

Street and Palm Street?

A. There is a trailer court down in the flat area right

(tr. 8) along side of Palm Street, a rather large trailer

court.

Q. And what is your experience with respect to the

student population coming out of trailer courts?

A. Well, that is about the same as housing. Sometimes

a little heavier.

Q. So you would anticipate at least one and a half,

probably two children for each trailer?

A. Right. That is correct.

Q. And do you have any idea how many trailers in there ?

A. More than fifty. I didn’t actually count them.

Q. I see. So that it was your—was the conclusion of the

Board that if they attempted to come across Court House

Road, the population is too heavy for this small school?

A. That is right. That was our conclusion.

44

Q. All right, I believe you can take your seat now.

(AYitness resumed witness stand.)

Q. Now, Mr. Smith, in the brief in support of this plan

which was filed by counsel, the statement was made, “in

the area of the Woodson School, there is a housing pro

ject under construction.”

Is that an accurate statement?

A. In the area of which school?

Q. Carter Woodson.

(tr. 9) A. No. The housing project has now been com

pleted. Now it is occupied.

Q. All right. Now, as I understood the answer that you

made the other day, you said that the Davisville housing

project, that that had been—the building had been destroyed.

Is that completely accurate ?

A. Not the Davisville housing project itself. There was

an auxiliary project to the permanent housing project. It

was an old Army barrack, and that has been demolished,

moved from there.

Q. Now, is there any building construction of any kind,

or residential construction of any kind going on in the

area of Harry James School?

A. Some, yes. Between, say, Wood’s Dairy and the

school itself, there are some houses back in there, in the

rear of the school.

Q. Now, I will ask you just one further question, Mr.

Smith. How would you characterize the street in Hope-

well which is known as West Broadway? I don’t believe

you have to go to the map to know that.

A. I believe I can do that from here, sir. West Broad

45

way is a through street from downtown Hopewell, all the

way to the west, to the railroad track in the extreme west.

Q. Is that the boundary line between the Patrick Cope-

(tr. 10) land School and the Dupont School for a good

deal of this distance?

A. That is.

MR. GRAY: All right, sir, that is all.

Thank you, Your Honor.

CROSS-EXAMINATION

BY MR. MARSH:

Q. Mr. Smith, you have seen this.

Mr. Smith, I hand you a comparison of the capacity,

average attendance, and pupil-teacher ratio in the Hope-

well High Schools. I believe you have seen that before the

hearing ?

THE COURT: Do you have a copy for me?

MR. MARSH: Yes. I was going to pass the original

up to you, sir.

THE COURT: That is all right. I can use the copy.

A. May I hang onto this ? I want to make a comment.

BY MR. MARSH:

Q. Do you recognize this to be the pupil-teacher ratio

and attendance figures?

46

A. It seems to be, yes. Generally, I’d say it is correct,

without checking it in detail.

(tr. 11) Q. Thank you.

A. Except for one item. The James School is listed at

330 pupil capacity. Actually, the James School has only ten

classrooms, which would be 300, There is a space over in

another building adjoining the school which has now been

turned back to the city, in which there was a space that a

classroom might be held. But, actually, in the school itself,

as it is now being used by the School Board, the capacity

is 300, rather than 330.

Q. I believe it is listed as 300 as of September, sir, and

it is listed as 330 as of last May ?

A. That is right.

Q. This was taken from the figures that you submitted

in evidence ?

A. That is right. In the plan we submitted it as 300.

Q. Well, I believe this is accurate, then?

A. 300 is accurate, then.

Q. Yes, we have it as 300 as of September.

A. Instead of 330.

THE CLERK: Defendant’s No. 5.

(A listing of the capacity, attendance, and pupil-teacher

ratio for the Hopewell schools was marked Defendant’s

(tr. 12) Exhibit No. 5 and received in evidence.)

BY MR. MARSH:

O. Now, Mr. Smith, at the present time, aside from the

original plaintiffs who were ordered admitted by the Court

4 7

last June, and the fifteen intervenors who were admitted to

white schools in September, are there any other Negro

pupils attending so-called white schools in the City of

Hopewell ?

A. If your question includes those that were voluntarily

let in and those that were let in by Court order, that is

right. There are no others. I think there were two or three

let in voluntarily. ,

Q. What do you mean “voluntarily,” sir?

A. I mean they were admitted because others had been

let in by a Court order in that immediate vicinity, and we

thought it wise not to contest other children who lived in

that same vicinity who wanted to.

Q. These children had applied, but they did not have

to come to Court?

A. That is right.

Q. I believe there were two or three that applied and

you agreed to let them in ?

A. That is right.

Q. But aside from those two or three, then, there are

no others?

(tr. 13) A. That is right.

Q. Are there any white pupils in attendance at any of

the all Negro schools?

A. No. Some were assigned, but they did not attend.

Q. I believe they were assigned in September when

you put your new attendance areas into effect?

A. I believe that is correct.

Q. Now, about how many were assigned at that time,

sir ?

A. As I recall it, there was some five.

48

Q. Five. And I believe those five all reside in the tri

angle bounded by South 15th Avenue, the Norfolk &

Western Railway, and the Seaboard Airline Railway?

A. The majority. I believe two are on the east side of

15th Avenue, in that same general vicinity.

O. What happened to those children after they were

assigned there, sir?

A. To my knowledge, one or two families moved, and

the others were sent to private schools, I believe.

Q. Now, are the Negro schools staffed solely by

Negroes as teachers and principals, sir?

A. Yes.

Q. And the predominantly white schools are staffed

solely by white teachers and principals ?

(tr. 14) A. Right.

Q. Now, 1 believe you testified, sir, that—you did not

testify, sir.

Would you come to the map, please?

A. Right.

(Witness stepped to the map.)

Q. Would you give us the racial composition of this

neighborhood in the area of the Arlington School? Is it

not a fact, sir, that the boundary line between the Wood-

lawn School, as shown on this map, and the Arlington

School separates the races? Is it not true that the white

live on this side, in the Woodlawn section of the zone,

and the Negroes live in the Arlington section, sir?

A. No, that is not true. There are some white houses

on Arlington Road. Several white houses on Arlington

Road, which is below the Wall Street, which we drew.

Also, there are white houses on Wall Street.

49

Q. Now, the white houses on Arlington Road, sir, are

they beyond the Miles Avenue? Are they not in the

County ?

A. The white houses on Arlington Road are between

Trenton Avenue and I believe Granby. Back along there,

somewhere. It is on this section after the curve in Arling-

ton Road coming back to 15th Avenue.

Q. This is Wall Street, sir, isn’t it? The boundary line

(tr. 15) here?

A. This is Wall Street. Arlington Road is here.

Q. Yes.

A. Right.

Q. Now, you are saying that there are several—

A. There are several white houses on Arlington Road

in the vicinity, say, of Freeman Street, between Freeman

Street and, say, Granby.

Q. About how many, sir, would you say?

A. I think there are about three.

Q. Now, south from those three?

A. I don’t know exactly how many there are.

Q. Aside from those three, is not the racial composition

of this area entirely white?

A. On Wall Street there are several white houses. I

don’t know how many.

Q. I know, but I am speaking now southeast of—

A. From Wall Street back towards the Woodlawn

School, yes.

Q. That is entirely white?

A. Yes.

Q. And from Wall Street northwest, in this direction,

50

aside from those three, the area is—the population is

entirely Negro?

(tr. 16) A. That is true, yes; as far as I know, that is

true.

Q. And this area down here, the persons who live in

this area, are Negro also?

A. Yes, as far as I know.

Q. Yes, and now I am speaking of—I am pointing to

the area in the vicinity—direct vicinity of the Arlington

School?

A. Right.

Q. I believe there was some discussion about the free

way that would run as an extension of Palm Street. Would

you indicate on this map in pencil, sir, where the freeway

connects from 15 th Avenue, and would you draw it from

this extension from 15 th Avenue all the way into Palm

Street ?

A. Well, you are speaking of Palm Street Extended

when you say freeway. It is not a freeway, actually.