United States v. Curtis Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 20, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Curtis Brief of Amicus Curiae, 1990. 8bb7d0d3-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6a4c89fe-7b50-47f3-be19-9187cdfe13a7/united-states-v-curtis-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

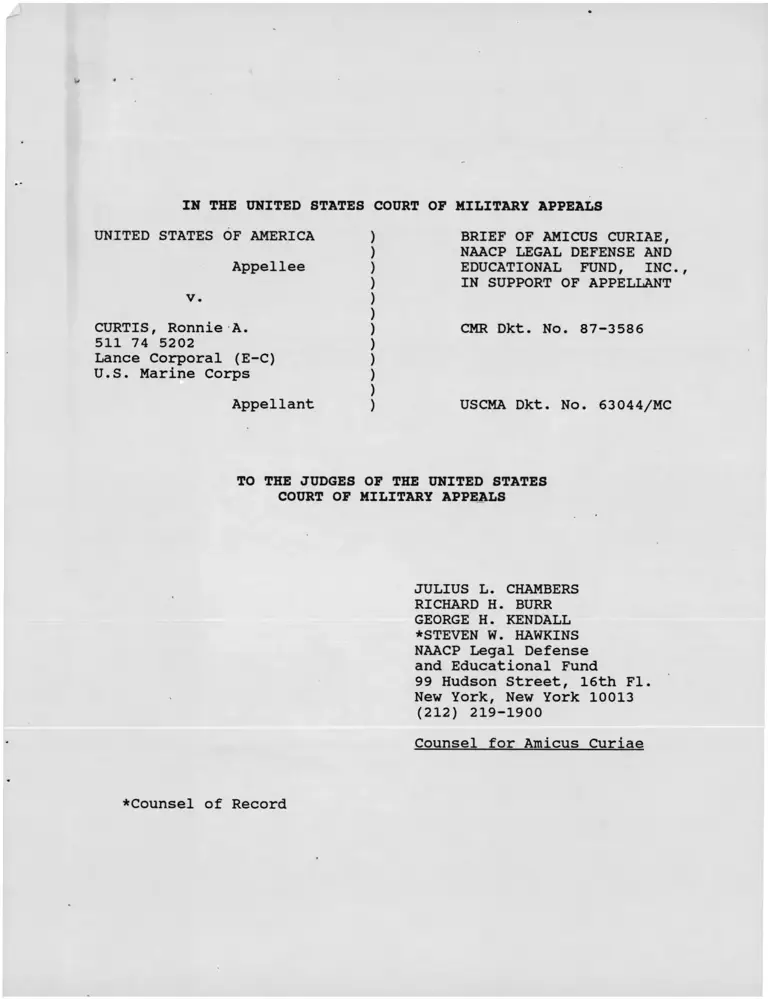

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA )

)

Appellee )

)

v. )

)

CURTIS, Ronnie A. )

511 74 5202 )

Lance Corporal (E-C) )

U.S. Marine Corps )

)

Appellant )

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT

CMR Dkt. No. 87-3586

USCMA Dkt. No. 63044/MC

TO THE JUDGES OF THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

RICHARD H. BURR

GEORGE H. KENDALL

*STEVEN W. HAWKINS

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

♦Counsel of Record

CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ......................................... ii

Introduction ................................................. 1

Argument ...................................................... 3

I. TRIAL COUNSEL DENIED PRIVATE CURTIS EQUAL

PROTECTION BY PEREMPTORILY EXCUSING A

PROSPECTIVE BLACK JUROR ON ACCOUNT OF

HIS RACE ...................................... 3

II. IN VIOLATIONS OF THE FIFTH AND EIGHTH

AMENDMENTS, TRIAL COUNSEL IMPERMISSIBLY

APPEALED TO RACIAL BIAS BY INACCURATELY

PORTRAYING THE INDECENT ASSAULT CHARGE AS

AN INDEPENDENT CRIME, AND BY ENCOURAGING

THE PANEL TO ACT UPON THE RACIAL BIAS

EVOKED BY THE FALSE CHARACTERIZATION OF

THIS INCIDENT ................................. 13

III. IN VIOLATION OF THE FIFTH AND EIGHTH

AMENDMENTS, TRIAL COUNSEL USED RACIAL BIASES

AND STEREOTYPES TO DENIGRATE THE SEVERITY

OF THE RACIAL HARASSMENT ENDURED BY

PRIVATE CURTIS ................................ 22

Conclusion .................................................... 28

i

CASES

Acres v. State. 548 So. 2d 459 Ala. Cr. App. 1987) ....... 10

Batson v. Kentucky. 476 U.S. 79 (1986) ..................... passim

Brown v. State of Alabama. 121 Ala.9, 25 So. 744 (1899) ... 21

Bucklev v. Valeo. 424 U.S. 1 (1976)....................... 5

Gamble v. State. 357 S.E.2d 792 (Ga. 1987) ................ 11

Garrett v. Morris. 815 F.2d 509 (8th Cir. 1987) ........... 10,11

People v. Hall. 672 P.2d 854 (Cal. 1983) ................... 10

State v. Neil. 457 So. 2d 481 (Fla. 1984), clarified sub

nom. State v. Castillo. 486 So. 2d 565 (1986) .......... 7

Powell v. State. 548 So. 2d 590 (Ala. Cr. App. 1988),

affld, 548 So. 2d 605 (Ala. 1989) ....................... 10

Roman v . Abrams. 822 F.2d 214 (2d Cir. 1987) .............. 10

State v. Slappy. 522 So. 2d 18 (Fla.), cert, denied. 108 S.

Ct. 2873 (1988) ........................................... 7, 8,

12, 27

Commonwealth v. Soares. 387 N.E.2d 499 cert denied. 444

U.S. 881 (1979) ........... ............................... 7

People v. Thompson. 453 N.Y.S. 739 (1981) .................. 7

People v. Turner. 726 P.2d 102 (Cal. 1986) ................ 11

Stanley v. Maryland. 524 A.2d 1262 (Md. Ct. App. 1988) ..... 12

Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28 (1986) ....................... 18

United States v. Clemmons. 843 F.2d 741 (3d Cir. 1988) .... 12

United States v. Curtis. 28 M.J. 1074 (N.M.C.M.R. 1989) ... 2

United States v. David. 803 F.2d 1567 (11th Cir. 1986) 12

United States v. Davis. 809 F.2d 1194 (1987) 10

United States v. Horsley. 864 F.2d 1543 (11th Cir. 1989) .. 12

United States v. Santiaqo-Davila. 26 M.J. 380 (C.M.A.1988) 4, 5,

12

ii

United States v. Tucker. 836 F.2d 334 (7th Cir. 1988) 11

United States v. Thompson. 827 F.2d 1254 (9th Cir. 1987) .. 10

United States v. Wilson. 853 F.2d 606 (8th Cir. 1988) 10

United States v. Wilson. 884 F.2d 1121 (8th Cir. 1989). 12

Vasouez v. Hillerv. 474 U.S. 254 (1986) .................... 13

People v. Wheeler. 583 P.2d 748 (1978) ..................... 7

MISCELLANEOUS

An American Dilemma (1944) .................................. 22

Black Rage (1968) ............................................ 25, 27

C. Hernton, Sex and Racism in America 4 (1965) ............ 22

Southern Rape Complex: Hundred Year Psychosis (1966) ..... 20

t

\

• • • ill

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA )

)

Appellee )

)

v. )

)

CURTIS, Ronnie A. )

511 74 5202 )

Lance Corporal (E-C) )

U.S. Marine Corps )

)

Appellant )

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT

CMR Dkt. No. 87-3586

USCMA Dkt. No. 63044/MC

TO THE HONORABLE, THE JUDGES OF THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF MILITARY APPEALS

Introduction

The government has sought to portray the conviction and death

sentence of Ronnie A. Curtis as involving a case where there were

three aggravating circumstances warranting death, and no evidence

of mitigation whatsoever. However, this case truly concerns the

devastating and pernicious effects the vestitudes of the

institution of slavery has visited upon our society, and its

accompanying racism that continues to engulf and strangle inter

personal relationships between blacks and whites. These forces

worked to vitiate the fairness of the judicial proceedings below.

The relation between Private Curtis and Lieutenant Lotz took

on a dynamic like that which existed between a slave and his

1

master. Through unrelenting racial harassment, Lieutenant Lotz

stripped Private Curtis of his name, his sense of self-worth, and

his family honor. Private Curtis became invisible, a non-person

who could be summoned by the snap of a finger. Private Curtis'

desire to be treated as a human being was met with unceasing

mockery and indignation by Lieutenant Lotz. Nothing, not even an

official reprimand from a superior, could deter Lieutenant Lotz.

It is inconceivable that any person could love and value

himself or herself and survive as a slave. Private Curtis came to

know his fate as a Hobson's choice; he could suffer the social

death of the subjugated, or strike back at his oppressor. One

night, after a walk around the yard and a pint of alcohol failed

to repress the haunting fact that Lieutenant Lotz treated him as

if he were a dog, Private Curtis decided to end to his suffering.

Tragically, but as surely, the same racism that ultimately

drove Private Curtis to kill Lieutenant Lotz and his wife found its

way into each and every step of his capital trial. First, the

government, in an action that was clearly racially motivated, used

its only peremptory strike to exclude a black person from the jury

who was as qualified as the whites who served. Secondly, the

government sought to evoke racial bigotry and bias in the hearts

and minds of the jury by admitting into evidence highly prejudicial

photographs that had, at best, only the slightest relevance.

Finally, the government embraced racism to cover up racism by

denigrating racial harassment as a substantial mitigating factor.

2

In the decades of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund's involvement

in cases tainted by racial bias and bigotry, the capital trial of

Private Ronnie A. Curtis stands out as one of the most straight

forward instances of where an entire proceeding was infected by

racism. Because Private Curtis was denied a fundamentally fair

trial process, this Court must reverse both his conviction and

sentence.

Argument

I. TRIAL COUNSEL DENIED PRIVATE CURTIS

EQUAL PROTECTION BY PEREMPTORILY

EXCUSING A PROSPECTIVE BLACK JUROR

ON ACCOUNT OF HIS RACE.

After completion of voir dire in Private Curtis' court-

martial proceeding, trial counsel used his only peremptory

challenge to excuse one of the black members of the court, Staff

Sergeant Edwards. Record at 334. Defense counsel objected. Id.

The military judge then recessed the proceeding in order for he

and counsel for the parties to familiarize themselves with Batson

v . Kentucky. 476 U.S. 79 (1986) . After the recess, the defense

counsel articulated the basis for his objection, stating, inter

alia, that the government was aware that one of the theories of

the defense was racial; that it was strange that the government

was using its only,peremptory strike to exclude a black person;

and that the use of the strike created an impression harmful to

the role of the jury as an instrument of fairness. Record at 336-

37.

3

The military judge then asked the prosecutor to explain his

reasons for the challenge. Record at 336-37. Trial counsel

stated:

[I]n my opinion, Staff Sergeant Edwards' response to the

voir dire, while satisfactory, didn't indicate to me to

be the kind of member the government would want on this

case . . . he said that he would consider this a learning

experience which, in the government's opinion, . . .

while not challengeable for cause, that is why the

government chose to exercise its peremptory challenge on

him.

Record at 337. Reasoning that three black members would remain on

the panel with the removal of Sergeant Edwards, the military judge

found the government's challenge to be "understandable" and to have

enough of a foundation to satisfy Batson. Consequently, the judge

overruled the defense counsel's objection to striking Sergeant

Edwards from the court-martial panel. Record at 338.

This Court has previously held that Batson is applicable to

trials by court-martial. United States v. Santiago-Davila. 26 M.J.

380, 389-90 (C.M.A. 1988) . This holding is based on a recognition

that the accused has "an equal-protection right to be tried by a

jury from which no 'cognizable racial group' has been excluded."

Santiago-Davila. 26 M.J. at 390 (quoting Batson. 476 U.S. at 96).1

In Batson. 476 U.S. 79 (1986), the Supreme Court held "that

a defendant may establish a prima facie case of purposeful

discrimination in selection of the petit jury solely on evidence

1 The equal protection principles of the Fourteenth Amendment

are implicit in the Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause and are

therefore applicable to the federal government. See Buckley v.

Valeo. 424 U.S. 1 (1976)(per curiam)("Equal protection analysis in

the Fifth Amendment area is the same as that under the Fourteenth

Amendment.")

4

concerning the prosecutor's exercise of peremptory challenges at

the defendant's trial." 476 U.S. at 96.

The Court set out a multi-part test to determine whether a

defendant had established a prima facie case:

[T]he defendant first must show that he is a member of

a cognizable racial group . . . and that the prosecutor

has exercised peremptory challenges to remove from the

venire members of the defendant's race. Second, the

defendant is entitled to rely on the fact that, as to

which there can be no dispute, peremptory challenges

constitute a jury selection practice that permits 'those

to discriminate who are of a mind to discriminate.' . .

. Finally, the defendant must show that these facts and

any other relevant circumstances raise an inference that

the prosecutor used that practice to exclude the

veniremen from the petit jury on account of their race.

476 U.S. at 96 (quoting Avery v. Georgia. 345 U.S. 559, 562

(1953)). The Court added that, "[i]n deciding whether the

I

defendant has made the requisite showing, the trial court should

consider all relevant circumstances." Id. "For example, a

'pattern' of strikes against black jurors" or "the prosecutor's

questions and statements during voir dire examination and in

exercising his challenges" may provide clues indicating whether the

prosecutor has intentionally discriminated. 476 U.S. at 97.

The record clearly demonstrates that Private Curtis has

established a prima facie case of intentional discrimination under

Batson. Private Curtis satisfies the first portion of the Batson

test because he is a member of a cognizable racial group, and the

government struck a member of his race from the jury panel. He is

entitled to a presumption with respect to the second part of the

test. Finally, after completion of voir dire and all challenges

for cause, the trial counsel used his only peremptory strike to

5

exclude a member of Private Curtis' race in a capital case

involving a black defendant and white victims. In light of the

prosecution's trial strategy — which included a significant

attempt to evoke racial stereotyping and racial bias against Mr.

Curtis, see points II and III, infra — this exercise of the

peremptory challenge was plainly racially-motivated. The use of

the government's strike under the relevant circumstances of this

case, therefore, is sufficient "to raise an inference" that the

juror was excluded "on account of [his] race," thereby satisfying

the final portion of the Batson test. 476 U.S. at 96.

The Batson court held that "[o]nce the defendant makes a prima

facie showing, the burden shifts to the [government] to come

forward with a neutral explanation" for its apparent racially

motivated challenge. 476 U.S. at 97. The Court emphasized that

the prosecutor's explanation need not rise to the level

justifying exercise of a challenge for cause. . . . But

the prosecutor may not rebut the defendant's prima facie

case of discrimination by stating merely that he

challenged juror of the defendant's race on the

assumption — or his intuitive judgment — that they

would be partial to the defendant because of their shared

race. . . . Nor may the prosecutor rebut the defendant's

case merely by denying that he had a discriminatory

motive or affirming his good faith in individual

selections.

476 U.S. at 97-98 (citing Alexander v. Louisiana. 405 U.S. 625, 632

(1972)). Instead, the prosecutor "must articulate a neutral

explanation related to the particular case to be tried," 476 U.S.

at 98, giving a "'clear and reasonably specific' explanation of his

'legitimate reasons' for exercising the challenges," id. at n. 20

(quoting Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine. 450 U.S.

6

248, 258 (1981)). Accordingly, a questioned challenge is only

permissible when, first, it is neutral and reasonable, and, second,

not a pretext.

The Florida Supreme Court has adopted a five-factor test for

determining the legitimacy of a race-neutral explanation which we

urge this Court also to adopt. That Court's judgment is due a

level of deference since Florida was one of the jurisdictions that

recognized a protection against improper bias in the selection of

juries that preceded Batson.2 In State v. Slappy. 522 So.2d 18

(Fla.), cert, denied. 108 S.Ct. 2873 (1988), the Court held that

one or more of the following factors would tend to show that the

prosecutor's race-neutral explanation was either not supported in

the record or was merely pretext:

(1) alleged group bias not shown to be shared by the

juror in question, (2) failure to examine the juror or

perfunctory examination, assuming neither the trial court

nor the opposing counsel had questioned the juror, (3)

singling the juror out for special questioning designed

to evoke a certain response, (4) the prosecutor's reason

is unrelated to the facts of the case, and (5) a

challenge based on reasons equally applicable to juror[s]

who were not challenged.

522 So.2d at 22. When the Slappy criteria are applied to the facts

of this case, the government's sole reason for excluding Sergeant

Edwards fails to stand up as a racially neutral explanation.

By analogy to the first Slappy factor, the purported rationale

See State v. Neil. 457 So.2d 481 (Fla. 1984), clarified

sub nom. State v. Castillo. 486 So.2d 565 (1986). Neil followed

the adoption of similar standards in California, People v. Wheeler.

583 P.2d 748 (1978), Massachusetts, Commonwealth v. Soares. 387

N.E.2d 499, cert denied. 444 U.S. 881 (1979) , and New York, People

v. Thompson. 453 N.Y.S. 739 (1981).

7

for striking Sergeant Edwards — i.e., he did not understand the

jury process — loses legitimacy when Sergeant Edwards' remarks in

voir dire are fully examined. In response to trial counsel's

question concerning how he felt about sitting as a member of the

court-martial in Private Curtis' case, Sergeant Edwards responded:

I feel, sir, basically that it would be to me a learning

experience. And coming in with an open mind, being able

to give everything, weighing out everything, and

listening to all the facts before I finally sav whether

a person is innocent or guilty, it would be a good

experience for me and something that I would like to go

through, sir.

Record at 257. Sergeant Edward's response clearly demonstrates

that he understood the critical nature of the duty he was being

asked to perform. Therefore, he did not possess the "trait" that

was the government's premise for striking him from the panel.

With respect to the fifth Slappy factor, trial counsel's

purported explanation for Edwards' exclusion is pretextual since

the challenge was based on a reason equally applicable to a white

prospective member who was not challenged. The voir dire of

Sergeant Justice, a white member of the panel, clearly showed that

he did not understand the most basic rules governing the trial:

ATC: . . . [D]o you agree that the accused has no

obligation, whatsoever to present any evidence or the

accused has no burden of proof?

MEM (SGT JUSTICE): I don't really understand.

ATC: The accused starts out, he's innocent before the

court today.

MEM (SGT JUSTICE): Yes, sir.

ATC: The government has the burden to prove the accused's

guilt. Do you agree with that proposition of law and do

you believe that the accused has no burden to put on

8

evidence, that the government has the burden?

MEM (SGT JUSTICE): To prove his innocence.

ATC: To prove his guilt.

MEM (SGT JUSTICE): To prove his guilt.

ATC: The accused has no burden to prove his innocence.

MEM (SGT JUSTICE) : I have a hard time with, sir — maybe

I'm just nervous. I don't know. I can't — for some

reason I can't think of what your — accused and the

terms as far as — are you asking me this, sir, that if

the government has to prove the individual guilty, okay?

ATC: Yes.

MEM (SGT JUSTICE) : And that he does not have to prove

himself to be innocent?

ATC: Yes.

Record at 262-63.

The record shows that Sergeant Justice had limited knowledge

about the most basic rules governing the trial. While Sergeant

Edwards at least had an interest in learning the trial process and

performing a juror's duty properly in that process, the record of

Sergeant Justice's voir dire gives no indication that he had any

such interest. From the perspective of whether the prospective

juror already had an understanding of the trial process, Sergeant

Justice certainly was no more worthy of being a member of the jury

than Sergeant Edwards. The military judge should have recognized -

- based on the answers given by both Sergeants Edwards and Justice

to questions during voir dire — that the government possessed no

legitimate basis for using its peremptory challenge since both

Sergeants Edwards and Justice were equally objectionable on the

grounds given for Sergeant Edwards' exclusion.

9

Numerous state and federal courts have used this test of

comparing black and white venirepersons to ferret out whether the

prosecutor's actions were racially motivated. See. e.g.. United

States v. Wilson. 853 F.2d 606, 610-12 (8th Cir.

1988)(comparability under Batson principle); United States v.

Thompson. 827 F.2d 1254, 1260-61 (9th Cir. 1987)(same); see also

Roman v. Abrams. 822 F.2d 214, 228 (2d Cir. 1987) (comparability

under a sixth amendment analysis); Garrett v. Morris. 815 F.2d 509,

514 (8th Cir. 1987)(comparability under application of Swain v.

Alabama. 380 U.S. 202 (1965)). Generally, courts have found

pretext where the reasons proffered for striking blacks from the

venire were applicable to whites who were not stricken. See United

States v. Wilson. 853 F.2d at 611; Powell v. State. 548 So.2d 590,

593-94 (Ala. Cr. App. 1988), aff'd. 548 So. 2d 605 (Ala. 1989);

Acres v. State. 548 So.2d 459, 473-74 (Ala. Cr. App. 1987); People

v. Hall. 672 P.2d 854, 858-59 (Cal. 1983) (in banc). Cf. United

States v. Davis. 809 F.2d 1194, 1203 (1987)(legitimate reasons for

exclusion since applicable to black and white venirepersons alike).

Specifically, both federal and state appellate courts have refused

to credit the prosecutor's explanation for striking blacks with

"low education" or "lack of knowledge" when unexcused whites were

found to have comparable levels of intelligence. See Garrett v.

Morris. 815 F.2d at 513-14; Gamble v. State. 357 S.E.2d 792, 795-

77 (Ga. 1987); People v. Turner. 726 P.2d 102, 109-110 (Cal.

1986) (in banc). Cf. United States v. Tucker. 836 F.2d 334, 340

(7th Cir. 1988)(exclusion of four black venirepersons from

10

complicated commercial case deemed legitimate since solely based

on their limited education).

In stark contrast, the military judge in Private Curtis' case

employed no meaningful evaluation to determine if the purportedly

neutral justification given by the government for striking Sergeant

Edwards was legitimate. Instead, the judge accepted it at face

value, merely noting that the government's reason for excluding

Sergeant Edwards was "understandable" and that "it appear[ed] to

have enough foundation to satisfy the rule announced in Batson v.

Kentucky." Record at 338 (emphasis added). In conducting such

cursory review of alleged racial motivations in the striking of a

black person from the panel, the military judge "failed to

discharge this] duty to inguire into and carefully evaluate the

explanation[] offered by the prosecutor." People v. Turner. 726

P.2d at 112.

Likewise, this Court must reject the rationale of the trial

judge in allowing the exclusion of Sergeant Edwards. In overruling

the defense counsel's objection to the strike, the judge noted that

"[w]ith the challenge of Staff Sergeant Edwards there would still

be three black members" on the jury panel. Record at 338. This

Court has previously rejected an argument by the government that

a prima facie case under Batson could not be established unless the

prosecution struck all members of the cognizable racial group from

the jury. See Santiaoo-Davila. 26 M.J. at 380 ("we do not think

that it is decisive that a prosecutor runs out of his peremptory

challenges before he can exclude all the members of a particular

11

group").

Numerous other courts have universally condemned any notion

that the Constitution would tolerate even a minuscule amount of

discrimination in the exercise of peremptory strikes. See United

States v. Wilson. 884 F.2d 1121, 1122-23 (8th Cir. 1989) (en

banc)(under Batson, the striking of one black juror for a racial

reason violates the Equal Protection Clause, even where other black

jurors are seated, and even when valid reasons for the striking of

some black jurors are shown); United States v. Horsley. 864 F.2d

1543, 1546 (11th Cir. 1989); United States v. Clemmons. 843 F.2d

741, 746 (3d Cir. 1988); Stanley v. Maryland. 542 A.2d 1267, 1277-

78 (Md. Ct. App. 1988); State v. Slappy. 522 So.2d at 21.

Clearly, "the command of Batson is to eliminate, not merely

to minimize, racial discrimination in jury selection." United

States v. David. 803 F.2d 1567, 1571 (11th Cir. 1986). This Court

would thus dishonor the command of Batson if it were to sanction

the prosecution's striking of Sergeant Edwards under the facts of

this case. The court would send a clear message to prosecutors

that it will permit "a little bit" of race discrimination. It

would be granting a license to those trial counsel who are of a

mind to discriminate to use the single peremptory strike afforded

them to exclude from the panel a member of a cognizable racial

group in every single case they try without any fear of

repercussion.

The record demonstrates that the government has failed to meet

its burden of showing a racially neutral reason for the exclusion

12

of Sergeant Edwards. In an analogous setting, the Supreme Court

held, in Vasouez v. Hillerv. 474 U.S. 254 (1986), that the

exclusion of blacks from a grand jury venire was a grave

constitutional error since it "call[ed] into question the

objectivity of those charged with bringing a defendant to

judgment." 474 U.S. at 263. The Court appropriately concluded

that its only recourse was to reverse the judgment of conviction

since it could "neither indulge a presumption of regularity nor

evaluate the resulting harm." Id. This reasoning is even more

pertinent in this case since it concerns the racially motivated

exclusion of a black from the jury that actually tries and convicts

a criminal defendant.

Accordingly, this Court must reverse Private Curtis's

conviction and sentence.

II. IN VIOLATION OF THE FIFTH AND EIGHTH

AMENDMENTS, TRIAL COUNSEL IMPERMISSIBLY

APPEALED TO RACIAL BIAS BY INACCURATELY

PORTRAYING THE INDECENT ASSAULT CHARGE AS

AN INDEPENDENT CRIME, AND BY ENCOURAGING

THE PANEL TO ACT UPON THE RACIAL BIAS

EVOKED BY THE FALSE CHARACTERIZATION OF

THIS INCIDENT.

Based on his statements taken at the time of his arrest and

from his testimony at trial, Private Curtis' actions on the night

of April 17 were all centered on Lieutenant Lotz. Private Curtis'

only thoughts that night were to end the racial harassment that

had caused him so much psycho-emotional pain and suffering, by

killing Lieutenant Lotz. Record at 542. He killed and assaulted

Mrs. Lotz not because of any animus he felt towards her, but

13

purely as a vav of further hurting Lt. Lotz. This fact is

reflected in Private Curtis' answers to the questions posed by his

attorney during direct examination:

Q. What were you thinking about Mrs. Lotz when you

stabbed her?

A . That she was part of . . . Lieutenant Lotz.

Q. How did you feel after this was all over, Lance

Corporal Curtis?

A. Felt like it was just . . . a madness, you know.

And I ripped off her panties and he saw me and [I]

said to myself, . . . You wanted a dog, you snapped

you fingers, you called me names, you wanted a dog,

here's vour dog right here.

Record at 544 (emphasis added). The emphasized segments of Private

Curtis' questions revealed the proper context in which his acts

against Mrs. Lotz had to be evaluated: he stabbed Mrs. Lotz because

she was "part of" the man against whom he felt enormous rage, and

he fondled her solely to humiliate the person who had so often

humiliated him. His acts against Mrs. Lotz were in no way

motivated by feelings about her — sexual or otherwise. She had

the misfortune of being "part of" the Lieutenant.

The trial counsel was erroneously permitted to rip the

indecent assault charge against Private Curtis for fondling Mrs.

Lotz out of context. In the total context of the crime, the

assault charge — viewed as an independent crime — was only a

minor offense. Its significance lay only in its illumination of

the rage and anger that Mr. Curtis directed toward Lieutenant Lotz.

However, the prosecutor was permitted to make it a centerpiece of

the government's case. In a pre-trial motion, defense counsel

tried to prevent this abuse from happening by moving for the

14

military judge to use his discretionary authority under the Rules

of Court Martial to sever the indecent assault charge from the rest

of the charges against Private Curtis in order to prevent a

manifest injustice. As defense counsel prudently cautioned:

[W]e're concerned that even if Lance Corporal Curtis

were to be found not guilty of that charge, it would

inherently prejudice the members in determining whether

or not Lance Corporal Curtis should live or die.

Record at 36. Trial counsel's rejoinder was that the charge was

merely part of the circumstances surrounding the event; however,

he then went so far as to propose a charge on the lesser offense

of "attempted indecent assault" in order to preserve the sexual

charge in the case. Record at 36-37.

The defense pointed out to the military judge the ulterior

motive behind the government's position, explaining that

there is one and only one reason for this offense being

on the charge sheet: . . . [it] is simply to inflame the

prejudice of the jury, because it's not an aggravating

factor, but everyone here knows good and well that sexual

assault has an extremely inflammatory effect upon a jury

and that's . . . why [the government is] adding it, even

though it's very nebulous.

Record at 37-38. The import of defense counsel's warning with

respect to how the indecent assault could be abused was lost on the

military judge. His only reaction was that "it is the more minor

variety of sexual assault certainly as it is alleged." Record at

38. Moreover, the military judge believed that any harm could be

cured through the government's proposed lesser-included charge.

Id. Consequently, he denied the defense counsel's motion for

severance.

As predicted, the government used the indecent assault charge

15

as a vehicle to inflame the prejudices of the court-martial panel.

By manipulating the evidence and presenting inflammatory argument,

trial counsel held up for the jury a vision of Ronnie Curtis

sexually assaulting Mrs. Lotz which created a false impression.

This impression — that there was an independent sexual assault by

a black man against a white woman — was then repeatedly paraded

before the jury by reference to the symbols of the assault, in an

effort to stir up one of the primordial components of racial bias

in this country: the belief that black men will take any

opportunity to sexually ravish white women.

Trial counsel began to evoke racial bias by trying to

introduce a photograph of Mrs. Lotz lying naked on the floor with

her bloody panties next to her. The defense moved to exclude the

admission of this picture prior to trial, arguing that it was

irrelevant since it showed no stab wounds, unlike other pictures

that the government sought to admit, and that the only reason the

picture was being used was to inflame the passions of the panel.

Record at 315-16.

Trial counsel did not stop with the introduction of this

picture. He went further, attempting to introduce into evidence

the blood-soaked panties. The defense counsel's motion in limine

sought to exclude the panties' admission, first on grounds that it

would be merely cumulative evidence if the picture of Mrs. Lotz

were admitted. Record at 316. Second, the defense counsel clearly

explained that

anytime you put a woman's undergarments in, especially

covered with blood, they can't help but excite the

16

passions of the members. Immediately, connotations come

to mind of, oh, rape or whatever type of heinous sex

crime that could possibly have been committed.

Id. Once again, however, the import of the inherent racial

prejudice in the admission of the picture and bloody panties was

lost on the military judge. He consequently denied the defense

counsel's motions without any limiting instructions.3 Record at

322.

The Supreme Court has recognized that any evidence of

interracial violence, even when related to a constitutionally

legitimate, aggravating factor — as distinct from its role in this

case — carries with it a very high potential for evoking race bias

and prejudice: "[f]ear of blacks, which could easily be stirred

up by the violent facts of petitioner's crime, ... might incline

a juror to favor the death penalty." Turner v . Murray. 476 U.S.

28, 35 (1986). In the face of the acknowledged potential for

evidence of the sort relied on by trial counsel to evoke racial

concerns, trial counsel took no steps to guard against its

evocation. To the contrary, he did all he could to maximize the

i In making his decision to deny the defense counsel's

motions, the military judge relied on cases where this Court found

no abuse of discretion in the admission of victims' photographs.

Apart from the fact that the descriptions of the pictures allowed

into evidence in those cases were highly distinguishable from the

photographs in the case at bar, the judge could not simply base his

decision to admit the picture of Mrs. Lotz and her bloody panties

on the basis of past cases. Military Rules of Evidence Rule 403

required him to conduct an independent balancing test that would

examine the admission of such evidence under the facts and

circumstances of this case. Because he never performed the

required balancing test, the judge erred, as a matter of law, in

admitting this evidence. Therefore, his decision to deny defense

counsel's motions to exclude the evidence are subject to plenary

review.

17

potential of the sexual assault charge to stir up racial passions.

Trial counsel immediately began to exploit race bias and

prejudice in his opening statement by portraying the assault

against Mrs. Lotz as an independent crime:

[Private Curtis] grabbed [Mrs. Lotz] by the legs, he

pulled her towards him, and he ripped off her panties,

and he not only ripped them off, he couldn't get them

off, so he used a knife, and then he indecently assaulted

her as she lay in her last moments . . . .

Record at 354.

This statement was followed by unrelenting reference to the

indecent assault charge throughout the trial. Since the picture

of Mrs. Lotz had no clinical value, trial counsel had to introduce

it4 through testimony of Naval Investigative Officer, Robert John

Vankuiken. Record at 414-16. Although not trained as a

pathologist, Special Agent Vankuiken's opinion about blood seepage

from stab wounds was erroneously used to substantiate the charge

that Private Curtis dragged Mrs. Lotz by the legs. Id. Trial

counsel next made continuous references to Mrs. Lotz's panties

during the course of testimony by his witnesses. Mr. Vankuiken so

testified. Record at 415. Special Agent Jackson so testified.

Record at 440. And David B. Flohr, a chemist with the Army Crime

Lab, so testified. Record at 465-467. After Mr. Flohr testified

about the tests he performed to determine that the panties had been

ripped and cut to produce "separations which the agents had noted

in the fabric," id. at 466, the panties were finally admitted into

4 Marked as Prosecution Exhibit 13.

18

evidence.5 Id. at 474-75. Still, mention of Mrs. Lotz panties

arose thereafter in the numerous persons' testimony. See, e .q. .

Record at 488, 528.

However, the trial counsel did not stop his race baiting at

this point. He further exploited race bias and prejudice through

the testimony of Special Agent Dobbs, who claimed that Mrs. Lotz

had pleaded with Curtis to stop stabbing her; had asked him what

she and her husband had ever done to him; and had called him by his

name. Record at 523. Supposedly, Private Curtis had given Special

Agent Dobbs this account, but it was not part of the Curtis'

statement admitted into evidence by the prosecution. Id.

Unquestionably, this hearsay statement painted for the jury a vivid

picture of a black man brutally assaulting and sexually molesting

an innocent white woman as she pled for Jher life. It was

specifically introduced for that purpose since it was the only

pertinent question asked of Special Agent Dobbs, whose entire

testimony was 1 1/2 pages. Record at 523-24.

Trial counsel's closing argument at the guilt-innocence phase

of the trial took full advantage of the racial prejudice that could

be evoked from the charge of sexual assault. He made certain that

the panel focused on the claim that

as [Mrs. Lotz] fell, [Private Curtis] grabbed her by the

legs and dragged her to him. . . . And then he ripped

her panties off. .- . . And then what did he do? He

placed his hand in her vaginal area and fondled her.

Record at 695. And during his closing argument at the sentencing

5 Marked as Prosecution's Exhibit 24.

19

phase, trial counsel pushed race bias and fear to the ultimate

level, reminding the panel of the stereotype of black men as

"savages" in their lust of white woman:, "[a]nd then he [Private

Curtis] committed the ultimate act of savagery, he violated her,

indecently assaulted her." Record at 815.

This Court can ill afford to sanction the injection of racial

bias and prejudice into this case by ignoring trial counsel's

flagrant misconduct in creating a false impression concerning the

indecent assault charge. The mere accusation that a black man has

sexually assaulted a white woman invariably unleashes racial bias.

Social scientists have documented for many years the role that

racial bias has played when such a charge is made. Indeed, it is

the archetypical example of the criminal charge that readily

inflames the prejudices of white jurors and interferes with their

ability to treat the black defendant fairly. In his classic study,

Southern Rape Complex: Hundred Year Psychosis (1966), Laurence Alan

Baughman chronicled a century's worth of cases where appeals to

racial bigotry, inflamed by allegations of inter-racial sexual

encounter, filled in the evidentiary gaps for whatever the

prosecution sought to prove. Id. at 110-36.

For example, the actions of the prosecutor in the case of

Brown v. State of Alabama. 25 So. 744 (1899), bear a frightening

resemblance to the behavior of the trial counsel in Private Curtis'

case. Brown, a black male, was charged with an assault with intent

to rape a young white girl. In his closing statement, the

prosecutor characterized Brown as "a fiend and a demon having a

20

foul heart." 25 So. at 745. Upon Brown's conviction, his attorney

appealed on grounds that the prosecution's attack on Brown was

clearly prejudicial. The appellate court denied relief, holding

that the solicitor's statements were proper because the charge

against Brown disclosed that he was a "fiendish" and "demoniacal"

person. Id. One hundred years later, this Court cannot tolerate

the use of such terms as "savagery" in a prosecutor's closing

argument in a case involving a black defendant and white victim.

As in 1899, the use of such terms as "savage" and "demon" is not

innocuous. It is a purposeful effort by the prosecutor to

stigmatize black men as something less than human, and to evoke

racial animus, rather than dispassionate analysis, as the basis for

<

decisionmaking. 1

The profoundly prejudicial impact of the government's abuse

of the indecent assault charge cannot be discounted by this court.

While we would all hope that racial bigotry with respect to inter

racial sex was on the wane, it is deeply rooted in the American

psyche. In his classic study, An American Dilemma (1944), Gunnar

Myrdal noted that when he asked Southern whites what they thought

blacks wanted most, they ranked "intermarriage and sex[ual]

intercourse" at the very top. Id. at 60-61. Another scholar has

similarly observed that "[t]he white man, especially the

Southerner, is overtly obsessed by the idea of [blacks] desiring

sexual relations with whites." C. Hernton, Sex and Racism in

America 4 (1965).

The record of Private Curtis' trial reflects that the

21

prosecutor transformed an incident that was motivated wholly by the

anger that drove Private Curtis to kill Lieutenant Lotz into an

independent crime against Mrs. Lotz that was motivated by sexual

passion — in blatant disregard of the facts. The reason for such

egregious misconduct was to interject racial bias against Private

Curtis in order to assure conviction and imposition of the death

sentence. The inflaming of racial prejudice was accomplished

through the picture of Mrs. Lotz lying naked on the floor, the

admission into evidence of her blood-soaked panties, and the

closing argument by the prosecutor. For these reasons, Private

Curtis's conviction and death sentence must be reversed. There was

an unacceptable risk that racial prejudice may have infected his

entire capital trial. Turner v. Murray. 476 U.S. at 37.

III. IN VIOLATION OF THE FIFTH AND

EIGHTH AMENDMENTS, TRIAL

COUNSEL USED RACIAL BIASES AND

STEREOTYPES TO DENIGRATE THE

SEVERITY OF THE RACIAL

HARASSMENT ENDURED BY PRIVATE

CURTIS.

Defense counsel presented overwhelming evidence of the racial

harassment to which Private Curtis was subjected on a continual

basis by Lieutenant Lotz. Shortly after Private Curtis reported

for duty in January 1985, Lieutenant Lotz began calling Private

Curtis names such as "Bebop Curtis" and "Curtis Blow." Record at

534-35, 580, 634. At first Private Curtis thought that the

Lieutenant was merely joking, but he soon discovered that the

22

Lieutenant was a racist who was always going to refer to him in a

derogatory fashion.

Contrary to the view of the U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Court of

Military Review, the Amicus respectfully asserts that Lieutenant

Lotz1s behavior towards Private Curtis was not the innocent

mistake of an inexperienced junior officer who had become too

familiar with his subordinates in an effort to be accepted.6 If he

merely wanted to be accepted, he would not have continued to

. /

insult Private Curtis and subject him relentlessly to indignities

after being told by Private Curtis that he found the Lieutenant's

behavior to be offensive. Record at 535, 581.

Indeed, the Lieutenant was fond of using racist terms to

describe his subordinates who were people of color. He would use

such despicable comments as "fuzzy-headed foreigner" and "dark

green Marine." Record at 632-36. Even though he was reprimanded

for this intolerable conduct, Record at 650-51, 689, Lieutenant

Lotz ignored the chain of command and continued his racist ways.

The Lieutenant's racist insults continued unabated against

Private Curtis. He would imitate a walk and style of talk that

symbolized the racist stereotypes of African-Americans and then

have the audacity to ask: " [I]s that how they do it Curtis?"

Record at 582. The racist image of a black man with a rag tied on

his head was also one of his favorite insults. Id. at 537. He

also got great joy out of portraying Private Curtis as some

6 See U.S. v. Curtis. N.M.C.M. 87-8586, slip op. at 21

(N.M.C.M.R. June 30, 1989).

23

stupid, confused person. He would call him "the lost one" and

relate to everyone in the supply office how "lost" Private Curtis

was when he arrived. Id. at 536.

Having stripped Lieutenant Curtis of his identity and his

dignity, Lieutenant Lotz also sought to cheapen and delegitimize

his family. He began by offensively referring to Private Curtis'

mother by her first name, although he had never met her. Record

at 538-39. Private Curtis told the Lieutenant to please refer to

his mother as "Mrs. Curtis," but the Lieutenant, having crossed

the boundaries of human decency, callously ignored the request and

continued to inquire about "Marie." Id.

Recounting the practices of past slavemasters, Lieutenant

Lotz successfully objectified Private Curtis by taking away his

name, his sense of self and his .family honor. Treating Private

Curtis in the same way slaves were treated, Lieutenant Lotz began

to refer to him as if he were merely chattel. He began summoning

him as if he were a dog by snapping his fingers. Record at 538-

39. If Private Curtis protested against such degradation, Lotz

would accuse him of having an "attitude" problem. Id. When he

could no longer bear the psycho-emotional pressure caused by Lt.

Lotz's unrelentless racial harassment, Private Curtis exploded.

Afterwards, unable to understand what had possessed him to do the

terrible deeds he committed, Private Curtis tried to find a guh in

the Lotz's home. If he had found a gun, Private Curtis would have

killed himself. Record at 544.

Private Curtis was a victim of oppression who finally lashed

24

back at his oppressor in a fit of uncontrollable anger. In their

seminal work, Black Rage (1968), William H. Grier and Price M.

Cobbs, two black psychiatrists, examined how racism could impact

on the psyche of black people to the extent that it did on Private

Curtis. They undertook their study because of the powerful

psycho-emotional dynamic they saw existing between whites and

blacks in the United States as a result of the institution of

slavery. They observed:

White citizens have grown up with the identity of

an American and, with that, the unresolved conflicts of

the slaveholder. White Americans are born into a culture

which contains the hatred of blacks as an integral part.

Blacks are no longer the economic underpinnings of

the nation. But they continue to be available as victims

and therefore a ready object for the projection of

hostile feelings. . . .

Because there has been so little change in the

attitudes, the children of bondage continue to suffer the

effects of slavery. There is a timeless quality to the

unconscious which transforms yesterday into today. The

obsessions of slave and master continue a deadly struggle

of which neither is aware. It would seem that for most

black people emancipation has yet to come.

Id. at 27.

This type of tension described by Grier and Cobbs defined the

relationship between Lt. Lotz and Private Curtis. Lt. Lotz assumed

the role of the tormenter, the slavemaster, and Private Curtis

assumed the role of the tormented, the slave. Ultimately, the

oppressed struck back at the oppressor. While Private Curtis'

response to his oppression was extreme, it was neither

unpredictable nor reflective of the moral bankruptcy of the

premeditated, mean-spirited murderer. As Grier and Cobbs noted:

25

"Oppression which is capable of producing fear and paranoia may

under slightly different circumstances produce the deadliest of

enemies." Id. at 93. They believed this to be true because

"[oppressed people] reduced to the status of non-persons and

removed from the protection of the social code can hardly be

expected to honor the responsibilities imposed by that code." Id.

The psychological phenomenon that Grier and Cobbs would

attribute to Private Curtis' actions in this case is analogous to

the recognized phenomenon of "battered wife syndrome." Both share

the elements of fear and vulnerability that are common to all

victims of oppression. Compare State v. Wanrow. 559 P.2d 548,

(Wash. 1977) (respondent was entitled to have the jury consider her

t

claim of self-defense in light of our nation's' "long and

unfortunate history of sex discrimination.")(quoting Frontiero v.

Richardson. 411 U.S. 677, 684 (1973)), with State v. Lamar. 698

P. 2d 735, 740 (Ariz. App. 1984) (jury asked to consider

reasonableness of black youths' reaction to white police officers

in light of their perception about the actions of police officers

being different from that of whites).

Moreover, such states as Florida and texas recognize, by

statute, that a victim's participation in the defendant's conduct

is a basis for mitigation in capital sentencing. See §

921.141(6)(c), Fla. Stat. (1983); Tex. Code Crim. Proc., Art.

37.071(b)(3) (Vernon 1981). Under those states' laws, Private

Curtis' conduct in light of Lieutenant Lotz's racial harassment,

though less than reasonable to support a claim of self-defense,

26

would clearly be mitigated by the Lieutenant's provocation.

However, trial counsel denigrated the significance of the

Lieutenant's racial harassment by once again appealing to racial

biases and prejudices. In his closing argument at the guilt-

innocence stage of Private Curtis' trial, the prosecutor tried to

portray the talks Private Curtis had with Trooper Addison, Major

Freeman and Special Agents Butler and Green as some kind of special

"black-to-black" talks in which Private Curtis would have allegedly

told them that racial prejudice was the reason why he killed

Lieutenant Lotz if it were. Record at 707-08. The trial counsel

discounted the offensiveness of the racist terms that Lieutenant

Lotz used to describe Private Curtis by telling the jury to think

of them as merely "nicknames." Id. at 709. He used the comments

of someone who was not African-American — and thus would have no

reason to be insulted by the term "fuzzy-headed foreigner" — to

sanitize the usage of that term to describe black people. Id.

Finally, and most shockingly, trial counsel injected pure racism

into the jury's deliberations by claiming that it was universally

recognized that some marines "were a darker green than others" and

that Lotz's use of the term "dark green marine" could not be

offensive to anyone. Id.

The government thus reverted to racial bias to portray the

comments made by Lieutenant Lotz as merely terms that anybody would

use to describe African-Americans. And in so doing, the government

doubled — and added its authority to — the racial mistreatment

of Private Curtis. The first form of racial mistreatment —

27

Lieutenant Lotz's unrelenting harassment — was the deeply tragic

legacy of slavery, which wounded Private Curtis so deeply that he

ultimately lashed out at the source of his injury. Except by its

relative inaction, the government bore no official responsibility

for this racial mistreatment. The second form, however — the

prosecutor's attempt to make light of Lieutenant Lotz's racial

harassment — was the sole responsibility of the government. The

Constitution cannot readily prevent persons like Lieutenant Lotz

from heaping their abuse upon others. It can — and must —

however, prevent the government from following suit. Accordingly,

the Constitution dictates that Private Curtis' conviction and death

sentence be reversed.

Conclusion

Because racial bias impermissibly tainted the entire trial,

through the racially motivated exclusion of a black from the jury

panel, through the appeal to prejudice by the prosecutor's abusive

manipulation of the indecent assault charge, and through the

prosecutor's impermissible denigration of racial harassment as a

mitigating factor, Private Curtis' conviction and sentence must be

reversed.

28

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

RICHARD H. BURR

GEORGE H. KENDALL

♦STEVEN W. HAWKINS

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

♦Counsel of Record

29

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that the foregoing Motion was filed in

the Court of Military Appeals, and copies were served upon counsel

for the parties by first class mail addressed to:

SUSAN K. MILLIKEN

LCDR, JAGC, SUN

Appellate Defense Division

Namara, JAG, Bldg. Ill, WNY

Washington, D.C. 20374

T.W. OSBORNE

CDR, JAGC, USN

Appellate Government Div.

NAMARA-JAG, Bldg. Ill, WNY

Washington, D.C. 20374

This day of April, 1990

Steven Hawkins

30

»

f