Avent v. North Carolina Brief of the Respondent, State of North Carolina, in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Avent v. North Carolina Brief of the Respondent, State of North Carolina, in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1960. e943fc78-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6a511854-b007-4c68-8983-51bbdedd36a9/avent-v-north-carolina-brief-of-the-respondent-state-of-north-carolina-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

j /V

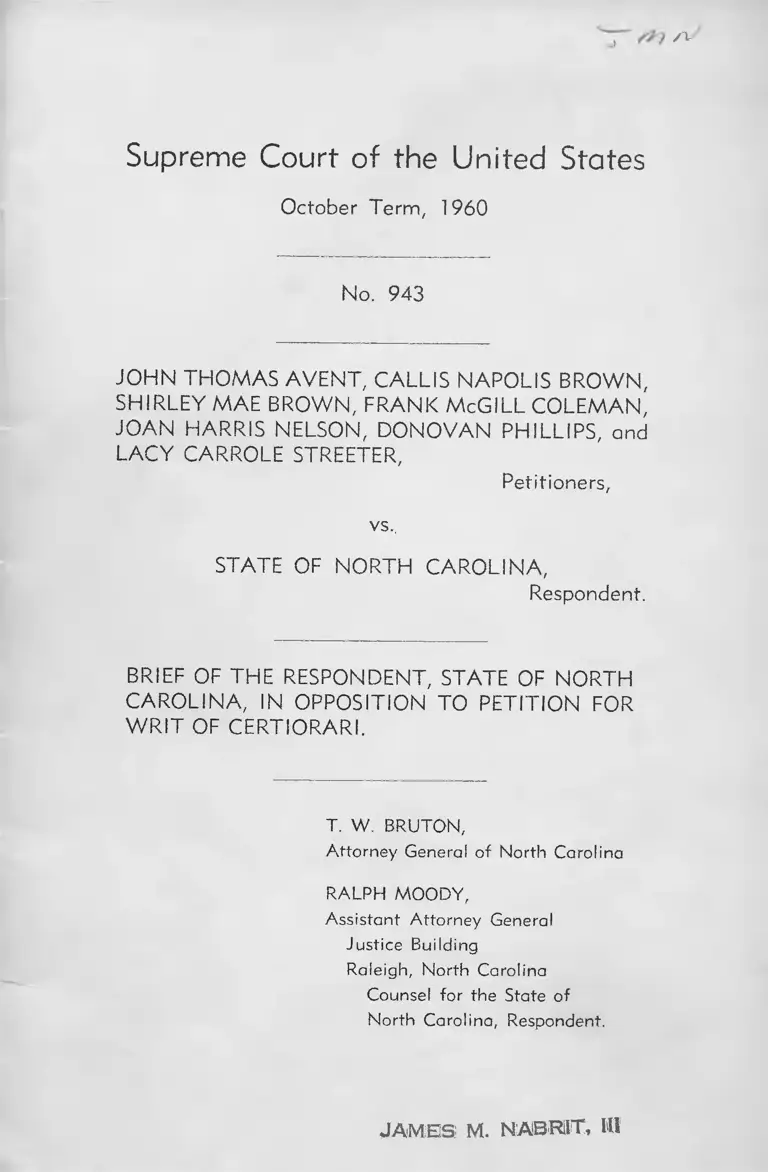

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No. 943

JOHN THOMAS AVENT, CALLIS NAPOL1S BROWN,

SHIRLEY MAE BROWN, FRANK McGILL COLEMAN,

JOAN HARRIS NELSON, DONOVAN PHILLIPS, and

LACY CARROLE STREETER,

Petitioners,

vs.,

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF THE RESPONDENT, STATE OF NORTH

CAROLINA, IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI.

T. W. BRUTON,

Attorney General of North Carolina

RALPH MOODY,

Assistant Attorney General

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina

Counsel for the State of

North Carolina, Respondent,

JAM ES M. NABRlT, Ml

INDEX

Opinion Below ........................................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction................................................................................................. 2

Questions Presented.................................................................................. 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved .......................... 2

Respondent’s Statement of the C ase................................................... 2

Argument ................................................................................................... 5

I. The State Prosecution did not Deprive Petitioners of

any Rights Protected by the Fourteenth Amendment....... 5

II. The State Statute is not Unconstitutional for Uncer

tainty and Vagueness ................................................................ 11

III. The Statute as Administered does not violate the

Constitutional Protection of Freedom of Speech................... 13

IV. Conclusion ....................................................................................... 16

TABLE OF CASES

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U.S. 582 ............... 10

Armstrong v. Armstrong, 230 N.C. 201, 52 S.E. 2d 362 ................... 9

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 .................................................... 6

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 .................... .............................. 12

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 .............................................................. 7

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F2d 531 .......................... 6

Bowder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, aff’d 352 U.S. 903 .................. 6

Boynton v. Virginia, ...........U.S............... , 5 L.ed. 2d 206 ................. 9

Brookside-Pratt Min. Co. v. Booth, 211 Ala. 268 .............................. 10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ................................... 7

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 29 U.S. Law

Week 4317........................................................................................... 7

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F.2d 425 .................................. 7

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 .............................................................. 16

Cole v. Arkansas, 338 U.S. 345 .......................................................... 12

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ................................................................ 7

l

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F.2d 922 ............................................... 7

Dawson v. Baltimore, 220 F.2d 386, aff’d 350 U.S. 877 ................... 7

Flemming v. South Carolina Elec. & Gas Co., 224 F.2d 752 ........... 6

Highland Farms Dairy v. Agnew, 300 U.S. 608 .............................. 10

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U.S. 77 .......................................................... 14

Lee v. Stewart, 218 N.C. 287, 10 S.E. 2d 804 .................................... 9

Monroe v. Pape, No. 39, Oct. Term, 1960, Feb. 20, 1961 ................ 6

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies, 312

U.S. 287 ........................................ f....................................................... 14

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 ............................................................ 15

Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373 ....................................................... 13

Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246 ............................................... 10

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 ................................................... 12

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 4 7 ................................................. 14

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 .............................................6,12

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ......................................................... 6,8

Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, Inc., 181 F. Supp.

124, aff’d 284 F.2d 746 ...................................................................... 10

State v. Avent, et als., 253 N.C. 580, 118 S.E. 2d 47 ...................... 1, 7

State v. Baker, 231 N.C. 136, 56 S.E. 2d 424 ..................................... 9

State v. Clyburn, 247 N.C. 455, 101 S.E. 2d 295 ............................ 9,10,11

State v. Cooke et als., 246 N.C. 518, 98 S.E. 2d 885 .......................... 9

State v. Goodson, 235 N.C. 177, 69 S.E. 2d 242 ............................ 9

Terminal Taxicab Co. v. Kutz, 241 U.S. 252 ..................................... 8

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 ................................................... 14

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 ........................................... 8

United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629 ................................................. 8

United States v. Wurzbach, 280 U.S. 396 ......................................... 12

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 ............................................................ 6

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845 ............. 10

Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 9 7 ............................................... 12

ii

CONSTiTUTlONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

Constitution of the United States:

First Amendment..................................................................................... 13

Fourteenth Amendment.........................................................2, 5,6, 7,8,11

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. 1257 (3) ................................................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. 1981 ................................... 6

42 U.S.C. 1982 ............................................................................................. 6

18 U.S.C. 242 ............................................................................................... 12

State Statutes:

Sec. 14 - 134 of General Statutes of North Carolina.................. 2, 9,11

Sec. 14 - 126 of General Statutes of North Carolina........................ 9

LAW REVIEW ARTICLES

Race Relations Law Reporter.............................................................. 6, 7

47 Virginia Law Review 1 .................................................................. 7

46 Virginia Law Review 123 ................................................................ 7

15 U. of Miami Law Review 123 ........................................................ 7

1960 Duke Law Journal 315 .............................................................. 7

109 U. of Pennsylvania Law Review 67 ......................................... 13

62 Harvard Law Review 7 7 .................................................................... 13

40 Cornell Law Quarterly 195 .............................................................. 13

iii

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1960

No. 943

JOHN THOMAS AVENT, CALLIS NAPOLIS BROWN,

SHIRLEY MAE BROWN, FRANK McGILL COLEMAN,

JOAN HARRIS NELSON, DONOVAN PHILLIPS, and

LACY CARROLE STREETER,

Petitioners,

vs.

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF THE RESPONDENT, STATE OF NORTH

CAROLINA, IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina, in

this case, is reported as STATE v. AVENT, et als, 253 N.C.

580 (No. 6, Advance Sheets of North Carolina, issued Feb

ruary 15, 1961); 118 S.E. 2d 47. The opinion of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in this case also appears in the

Petitioners’ Appendix attached to their Petition and Brief

at p. la. The Petitioners erroneously attribute the opinion

of the Supreme Court of North Carolina to “Mr. Justice Mal

lard,” when the truth of the matter is that Judge Mallard is

Judge of the Superior Court, which is a court of general

jurisdiction, and he tried the case in the Court below, at the

trial stage. The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Caro-

2

lina was written by Mr. Justice Parker, as will appear on p.

6a of the Petitioners’ Appendix. The Judgment of the Su

perior Court of Durham County, North Carolina, is not

officially reported but appears in the State Record certified

to this Court on p. 15.

JURISDICTION

The Petitioners invoke the jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1257 (3).

The Respondent, North Carolina, denies that this Court has

been presented a sufficient basis in this case for the ex

ercise of its jurisdiction.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The Respondent, North Carolina, will oppose the grant

ing of the Writ herein sought by the Petitioners and for pur

poses of argument the Respondent will assume that the

questions presented by the Petitioners on p. 2 of their

brief are the questions to be considered.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION AND STATUTE

INVOLVED

The Petitioners invoke Section 1 of the Fourteenth A-

mendment to the Constitution of the United States.

The Petitioners also attack Section 14-134 of the General

Statutes of North Carolina, the pertinent part of which is

as follows:

“G.S. 14-134. Trespass on land after being forbidden. If

any person after being forbidden to do so, shall go or enter

upon the lands of another, without a license therefor, he

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction, shall be

fined not exceeding fifty dollars or imprisoned not more

than thirty days.”

RESPONDENT'S STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Record of this case before the Supreme Court of

North Carolina (No. 654— 14th District—Fall Term, 1960)

3

has been certified to this Court by the Clerk of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina, and we will refer to this Record

(State Record) by the designation SR.

The Petitioners were each indicted by the Grand Jury of

Durham County for a violation of G.S. 14-134 in that they

committed a criminal trespass on the land and property of

5. H. Kress & Company, Owner, they having entered unlaw

fully upon said premises and having willfully and unlaw

fully refused to leave the premises after being ordered to do

so by the agent and manager of S. H. Kress & Company.

The indictments (SR-2) were all consolidated for the pur

pose of trial (SR-15); the cases were tried and presented to

the jury, and a verdict of guilty as to each Petitioner was

returned. (SR-15) The Court pronounced judgment in the

various cases which are shown on SR-15, and from these

judgments the Petitioners each appealed to the Supreme

Court of North Carolina.

This case is another facet of the demonstrations which

have occurred in various states and which have been spon

sored by the National Student Association, the Congress of

Racial Equality (CORE), and the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People. The movement was

dominated and led primarily by students of the colored race

and some students of the white race and the objective was

to move into various privately-owned stores and take charge

of the lunch counters which the owners maintained and

operated for customers of the white race and prevent the

white customers from being served at these lunch counters.

According to the evidence of W. K. Boger, Manager of the

Durham Store of S. H. Kress & Company, (SR-20) on May

6, 1960, all of the Petitioners came into the store located on

West Main Street in Durham. The luncheonette was open

for the purpose of serving invited guests and employees and

signs were posted over and about the luncheonette depart

ment stating that the department was operated for employ

ees and guests only; there were iron railings which sep

arated this department from the other departments in the

4

store, and the luncheonette department had chained en

trances. (SR-21) The manager had a conversation with every

one of the Petitioners, (SR-21) and he explained to them

the status of the lunch counter and asked the Petitioners to

leave. Before the Petitioners were seated at the lunch count

er the manager asked them not to take these seats, and when,

in spite of his directions and wishes, the Petitioners seated

themselves at the lunch counter, the manager asked them

to leave. (SR-21) The manager called an officer of the City

Police Department and the officer asked the Petitioners to

leave, and, upon their refusing to do so, each of the Peti

tioners was arrested for trespassing upon the property.

The Petitioner Frank McGill Coleman is a member of the

white race, a student at Duke University, and was engaged

in concerted action with the colored Petitioners. The Peti

tioner Joan Harris Nelson is a freshman at Duke University

and is apparently a white person. All of the actions of the

Petitioners show that they had previously discussed what

they would do and how they would operate in making this

demonstration and in creating a situation which would

afford a test case for the colored Petitioners.

The evidence of the State, as well as the evidence of the

Petitioners, establishes certain facts, as follows:

(1) That prior to the sit-in demonstrations which re

sulted in the present arrests and indictments of the Peti

tioners, the Petitioners had counsel and had consulted

counsel while the demonstration was in its organizational

process. (SR-38)

(2) The Petitioners had previously been engaged in

picketing this store and in urging a boycott unless their

demands for luncheon service were met. (SR-37, 41, 42, 44,

48, 49, 50.)

(3) It is clear from the evidence of Callis Napolis Brown

(SR-46) that there was an organization for this purpose,

that the organization had leaders, and that a meeting was

5

held on the night before May 6, 1960, and it was decided and

planned to make a purchase in some other part of the store

before going down and attempting to secure lunch counter

service. (SR-46)

(4) Purchases were made by these defendants according

to this previously agreed upon design or plan. (SR-36, 40,

43, 45, 48, 49)

(5) It is plain that the Petitioners expected and anticipat

ed that they would not be served at the lunch counter and

that they intended to remain until they were arrested. It is

also clear that they solicited the aid of the two white stu

dents for the purpose of having an entering wedge into the

seats of the lunch counter and for the purpose of confusing

the situation by having the white students purchase the food

and give it to the colored students.

(6) It is further clear that counsel had been consulted

and cooperated in all these movements even to the point

of providing bonds for the Petitioners after they were ar

rested. (See SR. 39, where Lacy Carrole Streeter testified:

“I left the matter of a bond to my attorneys. I employed my

attorneys in February. I started consulting with my attor

neys in February. I kept them retained until May 6, I960.”)

ARGUMENT

THE STATE PROSECUTION DID NOT DEPRIVE P E T I

TIONERS OF ANY RIGHTS PROTECTED BY THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

Petitioners in their Brief assert several propositions relat

ing to race discriminations prohibited by the Fourteenth

Amendment about which there is no contest and which do

not come within the ambit of the issues to be resolved in

this case. Some of these propositions, about which there is

no controversy, are as follows:

6

(1) The Respondent admits that action by the judicial

branch of a state government can be such a type of state

action that offends against the prohibitory provisions of

the Fourteenth Amendment (SH ELLEY v. KRAEMER, 334

U. S. 1; BARROWS v. JACKSON, 346 U. S. 249; Race Rela

tions Law Reporter, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 613, 622). We still

think there is such a thing as valid state action by the

judicial branch of a state government.

(2) The Respondent admits that the provisions of the

Fourteenth Amendment extend to and reach the conduct of

state police officers (MONROE v. PAPE, No. 39, Oct. Term,

1960, Feb. 20, 1961; SCREWS v. UNITED STATES, 325

U. S. 91). We deny that it extends to and reaches valid

conduct of state police officers exercised under valid state

authority.

(3) We admit that there can be unlawful state action by

a police officer acting under “color of law” where a state

has enacted a Civil Rights statute which prohibits the denial

of accommodations or privileges to a person because of color

in places of amusement or in restaurants. (VALLE v. STEN

GEL, CCA-3, 176 F. 2d 697, 701). We think the rule can

be different where a state has no such statute.

(4) We admit that where a state grants a franchise to a

public utility there cannot be discrimination in the use of

facilities or services furnished the patrons because of color

nor can the state enforce such discriminations by delegating

the power to make rules or by criminal sanctions (BOMAN

v. BIRMINGHAM TRANSIT CO., CCA-5, 280 F. 2d 531;

BOWDER v. GAYLE, 142 F. Supp. 707, aff’d 352 U. S. 903;

FLEMING v. SOUTH CAROLINA ELEC. & GAS CO., CCA-

4, 224 F. 2d 752). We deny that this rule applies to business

under private ownership.

(5) We admit that all citizens, white and colored, have

the right to contract, acquire and own property, are entitled

to security of person and property, and to inherit, purchase,

lease, hold and convey real and personal property as set

forth in R.S. 1977, 42 USC 1981, and R.S. 1978, 42 USC

7

1982. We do not admit that any person, white or colored,

can be constitutionally forced to sell any private property

or product to another person, or that one person is forced

to negotiate with another person in or about any property

or business transaction.

(6) We admit that there is an abundance of legal author

ity to the effect that a state or a subdivision of a state which

operates restaurants or other facilities, or operates play

grounds or parks, or facilities of this nature, cannot by the

device of a lease to private persons or firms discriminate

against colored persons who desire to use such facilities, and

that “the proscriptions of the Fourteenth Amendment must

be complied with by the lessee as certainly as though they

were binding covenants written into the agreement itself.”

(BURTON v. WILMINGTON PARKING AUTHORITY, 29

U. S. Law Week 4317, No. 164, Oct. Term 1960, April 17,

1961; DERRINGTON v. PLUMMER, CCA-5, 240 F. 2d 922;

CITY OF GREENSBORO v. SIMKINS, CCA-4, 246 F. 2d

425; DAWSON v. BALTIMORE, CCA-4, 220 F. 2d 386, aff’d

350 U. S. 877).

(7) We don’t think the cases on discrimination in public

schools have anything to do with this case, but we admit

there can be no state action which supports racial discrimi

nation in this field and as set forth in the cases of BROWN

v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 347 U. S. 483, BOLLING v.

SHARPE, 347 U. S. 497, and COOPER v. AARON, 358 U. S.

1 .

Our contentions and the concepts that we believe to be

sound have been fully stated by Mr. Justice Parker in

STATE v. AYENT et als., 253 N. C. 580 (N. C. Advance

Sheets No. 6, issued Feb. 15, 1961), 118 S. E. 2d 47, Peti

tioners’ Appendix p. 2a. The matter has been considered

by the law review writers (47 Virginia Law Review—No. 1,

Jan. 1961, p. 1; 46 Virginia Law Review - 1960 - p. 123; 15

U. of Miami Law Review - No. 2 - 123; Race Relations Law

Reporter, Vol. 5, No. 3 - Fall 1960 - p. 935; 1960 Duke Law

Journal 315).

8

We assert that private citizens or persons have the right

to practice private discrimination for or against each other.

This runs all through the fabric of society and life. Clubs,

lodges and secret societies will accept some as members and

reject others. The country club people do not associate with

the people that live in slum areas and across the railroad

track. The people of some races will have no dealings with

people of other races. Discriminations are practiced inside

the race group. The colored insurance men, doctors and

bankers do not have social affairs that are open to the cot

ton and cornfield Negroes. We further assert that any color

ed citizen can refuse to transact business with a white per

son or to have him on his business premises and the rule

applies in reverse. Up to the present time, in private busi

ness, no man has been compelled to sell his product, goods

or services to another unless he desired to so do. The rea

sons or motives that prompt his choice of action are irrele

vant. The same private rights in the use and enjoyment of

property are available to all. The protection of these private

rights is not an “indiscriminate imposition of inequalities”.

As said by Mr. Justice Holmes (TERMINAL TAXICAB CO.

v. KUTZ, 241 U. S. 252, 256):

“It is true that all business, and for the matter of that,

every life in all its details, has a public aspect, some

bearing on the welfare of the community in which it is

passed. But however it may have been in earlier days

as to the common callings, it is assumed in our time

that an invitation to the public to buy does not neces

sarily entail an obligation to sell. It is assumed that an

ordinary shopkeeper may refuse his wares arbitrarily

to a customer whom he dislikes * *

This court carefully stated (SH ELLEY v. KRAEMER,

334 U. S. 1):

“That Amendment erects no shield against merely priv

ate conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful.” (cit

ing in the note: UNITED STATES v. HARRIS, 106

U. S. 629; UNITED STATES v. CRUIKSHANK, 92 U. S.

542.)

9

In BOYNTON v. VIRGINIA, 5 L. ed. 2d 206, ______

U. S . _______, this Court said:

“We are not holding that every time a bus stops at a

wholly independent roadside restaurant the Interstate

Commerce Act requires that restaurant service be sup

plied in harmony with the provisions of that Act.”

But if there existed another vital, and primary constitu

tional principle that required that restaurant service be

supplied by the roadside restaurant to a colored man, then

there would seem to be no reason why this Court should

pass it by and not settle the question.

The State Statute here under consideration is an old

statute and has been passed upon by the Supreme Court

of North Carolina many times. It appears in the State code

as G. S. 14 - 134 and we refer the Court to certain cases, as

follows: STATE v. CLYBURN, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d

295; STATE v. COOKE et als., 246 N. C. 518, 98 S. E. 2d 885;

STATE v. GOODSON, 235 N. C. 177, 69 S. E. 2d 242; ARM

STRONG v. ARMSTRONG, 230 N. C. 201, 52 S. E. 2d 362;

L EE v. STEWART, 218 N. C. 287, 10 S. E. 2d 804; STATE

v. BAKER, 231 N. C. 136, 56 S. E. 2d 424. See also cases

cited in annotation to Sec. 14 - 134 in General Statutes of

North Carolina, and the 1959 Supplement thereto. A related

statute is G. S. 14 - 126 which is as follows:

“No one shall make entry into any lands and tenements,

or term for years, but in case where entry is given by

law; and in such case, not with strong hand nor with

multitude of people but only in a peaceable and easy

manner; and if any man do the contrary, he shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor.”

This statute was borrowed from English law and in sub

stance is 5 Richard II, c. 8, and in fact it would appear that

this statute and the one under consideration are formulations

of the common law.

10

The statute now attacked by Petitioners is a neutral sta

tute and has no connection with the color of persons. We

challenge the Petitioners to trace the reported decisions and

show that in its judicial administration it has been applied

to colored persons and not to white persons. It is available

to the colored man if a white man will not leave his premises

when requested to do so.

The implied invitation to the general public to come into

a shop or store can lawfully be revoked. On this aspect of

the case the Supreme Court of North Carolina (253 N. C.

580, 588) said:

“In an Annotation in 9 A.L.R., p. 379, it is said: ‘It

seems to be well settled that, although the general pub

lic have an implied license to enter a retail store, the

proprietor is at liberty to revoke this license at any time

as to any individual, and to eject such individual from

the store if he refuses to leave when requested to do

so.’ The Annotation cites cases from eight states sup

porting the statement. See to the same effect, BROOK-

SIDE-PRATT MIN. CO. v. BOOTH, 211 Ala. 268, 100

So. 240, 33 A.L.R. 417, and Annotations in 33 A.L.R. 421”.

Leaving aside the question of void-for-vagueness, the in

terpretation of the highest appellate Court of a state should

be accepted by the Federal Courts (AMERICAN FEDERA

TION OF LABOR v. WATSON, 327 U. S. 582; PH ILLIPS v.

UNITED STATES, 312 U. S. 246; HIGHLAND FARMS

DAIRY v. AGNEW, 300 U. S. 608).

The Petitioners have not cited any case dealing with priv

ate discrimination which supports their position, and indeed

they cannot do so. Up to the present time the Courts that

have considered the matter support our position (STATE

v. CLYBURN, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. 2d 295; WILLIAMS

v. HOWARD JOHNSON’S RESTAURANT, 268 F. 2d 845;

SLACK v. ATLANTIC W HITE TOWER SYSTEM, INC.,

181 F. Supp. 124, aff’d 284 F. 2d 746; see also cases cited

in opinion of Supreme Court of North Carolina in this case,

and in law review articles cited supra).

11

As we see the matter, up to the present time, wherever

the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment have been

invoked there has been a clear, established right to be pro

tected from state action or from any discrimination aided

or assisted by state action. Up to the present time in this

case the Petitioners are starting from a position where they

have no clear, established right to be protected by constitu

tional guarantees. They are asking the Court to invent, create

or conjure up the claimed right and then say it is entitled

to the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment. If it shall

be said that the State court cannot exert its power to protect

the property rights of either race but will leave the parties

to their own devices, or to the exercise of personal force,

then the result will be something that neither the white or

colored race really desires.

II

THE STATE STATUTE IS NOT UNCONSTITUTIONAL

FOR UNCERTAINTY AND VAGUENESS.

The Petitioners’ next attack on the statute comes under

the so-called void-for-vagueness doctrine. Here we enter into

a field of constitutional law which it seems to us is measured

entirely by subjective tests.

There is one thing sure however—the Petitioners were

engaged in a previously organized campaign and there is

strong reason to believe from the evidence that they had

the advice of counsel. The Supreme Court of North Carolina

has construed G. S. 14 - 134 many times to include the situ

ation where a person enters upon lands or premises without

protest and is later told by the owner or proprietor to leave

the premises. The case of STATE v. CLYBURN, 247 N. C.

455, 101 S. E. 2d 295, was decided on January 10, 1958, and

Petitioners and their counsel had ample warning of this

construction of the statute. We have heretofore cited above

many cases in which the Supreme Court of North Carolina

has construed the statute. This Court has said in substance

that impossible standards of definition are not required and

12

that it is sufficient if the language “conveys sufficiently

definite warning as to the proscribed conduct when measur

ed by common understanding and practices.” On this point,

see ROTH v. UNITED STATES, 354 U. S. 476, and see an

notation in 1 L. ed 2nd, p. 1511.

This State statute is certainly no more vague or uncertain

than 18 USCA 242, which reads as follows:

“Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, or custom, willfully subjects, or causes to

be subjected, any inhabitant of any State, Territory,

or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges,

or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution

and laws of the United States, or to different punish

ments, pains, or penalties, on account of such inhabitant

being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than

are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be

fined not more than $1,000.00, or imprisoned not more

than one year, or both.”

This Court reviewed the statute and its history and up

held the statute against an attack based on unconstitutional

vagueness in SCREWS v. UNITED STATES, 325 U. S. 91.

For other causes in which statutes have been upheld

against such an attack see: BEAUHARNAIS v. ILLINOIS,

343 U. S. 250, COLE v. ARKANSAS, 338 U. S. 345, W IL

LIAMS v. UNITED STATES, 341 U. S. 97, UNITED

STATES v. WURZBACH, 280 U. S. 396.

As a practical matter, an ordinary layman has trouble with

any statute no matter how precise its standards of conduct

and no matter how clear it may be in the informational pro

cess. Statutes really are written for lawyers to read and to

form opinions and advise clients thereon, and the statute

now under attack when considered with the constructions

of the highest appellate Court of the State clearly informs

Counsel for Petitioners what the consequences could be.

There must be some latitude in statutory language be-

13

cause statutes are drafted for the most part in an attempt

to take care of unanticipaed situations as well as those that

may be in contemplation when the drafting process is first

initiated. In NASH v. UNITED STATES, 229 U. S. 373, Mr.

Justice Holmes summed up the situation as follows:

“But, apart from the common law as to the restraint of

trade thus taken up by the statute, the law is full of

instances where a man’s fate depends on his estimating

rightly, that is, as the jury subsequently estimates it,

some matter of degree. If his judgment is wrong, not

only may he incur a fine or a short imprisonment, as

here; he may incur the penalty of death.’

This question has also been written about extensively by

the law review writers and in closing this portion of the

argument we cite a few of these articles but this is not to

be construed by the Court as meaning that we approve all

the criticisms and conclusions of the authors (109 University

of Pennsylvania Law Review - No. 1, November 1960 - p. 67,

62 Harvard Law Review 77, 40 Cornell Law Quarterly 195).

Ill

THE STATUTE AS ADMINISTERED DOES NOT VIO

LATE THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION OF

FREEDOM OF SPEECH.

We assume here that the Petitioners are dealing with the

principles of the First Amendment insofar as they may be

incorporated in the Fourteenth Amendment. The evidence

shows that Petitioners exercised their right of free speech

to the fullest extent. Petitioners and their adherents had

for days been exercising their right to protest and the right

of freedom of speech by writings and slogans on placards

which they carried up and down the streets in front of the

stores. This was certainly true in the AVENT case and in

both cases there is no evidence to show that they had been

restrained in any manner in the exercise of this right. The

use of the streets and sidewalks of the town and city con-

14

cerned had been utilized by Petitioners in the AYENT case

and there is no reason to believe that any restraints would

have been placed upon Petitioners in the exercise of free

speech in any proper place. Of course, free speech is not a

mighty shield that insulates a person from liability in all

types of criminal conduct. Such a logic would extend free

speech as a protection from the penalty of murder and would

act as a complete and conclusive defense for the commission

of all criminal acts. This is explained by a paragraph in

KOVACS v. COOPER, 336 U. S. 77, where this Court said:

“Of course, even the fundamental rights of the Bill of

Rights are not absolute. The SAIA case recognized that

in this field by stating ‘The hours and place of public

discussion can be controlled.’ It was said decades ago

in an opinion of this Court delivered by Mr. Justice

Holmes, SCHENCK v. UNITED STATES, 249 U. S. 47,

52, 63 L. Ed 470, 473, 39 S Ct 247, that: ‘The most

stringent protection of free speech would not protect

a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing

a panic. It does not even protect a man from an in

junction against uttering words that may have all the

effect of force.’

“Hecklers may be expelled from assemblies and relig

ious worship may not be disturbed by those anxious

to preach a doctrine of atheism. The right to speak one’s

mind would often be an empty privilege in a place and

at a time beyond the protecting hand of the guardians

of public order.”

In the case of MILK WAGON DRIVERS UNION v.

MEADOWMOOR DAIRIES, 312 U. S. 287, 61 S. Ct. 552, 85

L. ed 836, the Court sustained an injunction against picket

ing where there was a history of past violence against a

plea of freedom of speech and distinguished the case from

that of THORNHILL v. ALABAMA, cited by the Petition

ers, and said:

“This is precisely the kind of situation which the Thorn

hill opinion excluded from its scope. ‘We are not now

15

concerned with picketing en masse or otherwise con

ducted which might occasion such imminent and ag

gravated danger . . . as to justify a statute narrowly

drawn to cover the precise situation giving rise to the

danger.’ 310 U. S. 105, 84 L. Ed. 1104, 60 S. Ct. 736. We

would not strike down a statute which authorized the

courts of Illinois to prohibit picketing when they should

find that violence had given to the picketing a coersive

effect whereby it would operate destructively as force

and intimidation. Such a situation is presented by this

record. It distorts the meaning of things to generalize

the terms of an injunction derived from and directed

towards violent misconduct as though it were an ab

stract prohibition of all picketing wholly unrelated to

the violence involved.”

We shall not burden the Court with further citations from

case law but it is sufficient to say that the injuctions

sustained by this Court in labor disputes where violence

and destruction of property were involved are certainly not

constitutionally invalid because those who were engaged in

picketing carried banners and mottoes and other writings

in the exercise of communications and freedom of speech.

The case of MARSH v. ALABAMA, supra, is no excep

tion to this rule. The defendants in the MARSH case were

distributing religious literature and engaged in talking to

persons on the streets of a company-owned town. They were

not in stores interfering with the businesses of private pro

prietors. The Supreme Court of the United States simply

said that where a company owned the streets and sidewalks

the people of the town were compelled to use them in com

munity affairs, that these streets and sidewalks were con

stitutionally dedicated to the public in the same manner as

the streets of a municipal corporation.

16

IV

CONCLUSION

This Court in these cases is being asked to take a step

which has never before been taken with reference to the use

and enjoyment of property rights. To grant the request of

the Petitioners opens the door to the socialization of all

property and would mean that while a proprietor may

have the privilege of holding the bare legal title yet the

property would be subjected by the State to so many social

demands that it would be almost analogous to property

held in the corporative state organized and administered

for awhile by Mussolini. Petitioners realize that their logic,

as derived from their premises, leads to great extremes and

they try to hedge against these extremes. For example, must

the Petitioners be given entrance to the office of the man

ager and must they be allowed to go to the stockroom?

Suppose the clerks tell Petitioners that they do not have

certain articles and the Petitioners think they can find some

of the articles in the stockroom, can they go to the stock-

room over the p r o t e s t of the management? Suppose

private properietors are compelled to sell to Petitioners, at

what price must they sell? If a private properietor sold

articles or food to his friends at no cost or at a cheaper

rate than usual, would this violate Petitioners’ civil rights?

Under their own theory, why should not Petitioners be

allowed to enter into any private home they desire so long

as they say that they are protesting and exercising free

speech? The Petitioners’ request should not be granted un

less the Court thinks we should have a completely socialized

state. There should be left to an individual some property

rights that he can call his own or else why should we have

the institution of private property. We ask the Court not

to take such a step and in this connection we again remind

the Court of the langauage this Court used in civil rights

cases (109 U.S. 3) when it said:

“When a man has emerged from slavery, and by the aid

of beneficient legislation has shaken off the inseparable

17

concomitants of that state, there must be some stage

in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank

of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of

the laws, and when his rights, as a citizen or a man,

are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other

men’s rights are protected.”

Respectfully submitted,

T. W. BRUTON

Attorney General of North Carolina

RALPH MOODY

Assistant Attorney General

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina

Counsel for the State of North Carolina

Respondent