Ross v. Houston Independent School Appellants Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1982

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ross v. Houston Independent School Appellants Reply Brief, 1982. 097f494f-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6a7c0389-2865-4d37-be76-4351f5560b5c/ross-v-houston-independent-school-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

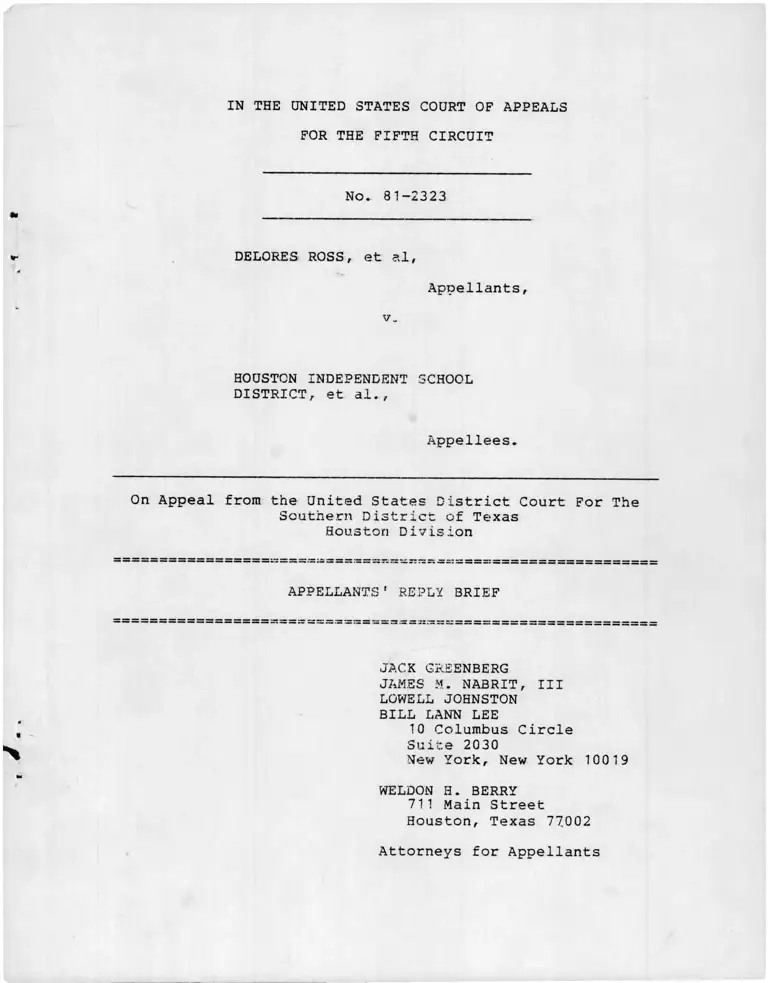

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-2323

DELORES ROSS, et al,

Appellants,

v„

HOUSTON INDEPENDENT SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court For The

Southern District of Texas

Houston Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

LOWELL JOHNSTON

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

WELDON H. BERRY711 Main Street

Houston, Texas 77002

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ................................... ii

>>

ARGUMENT

I Introduction .............................. 1

II The HISD and the District Court

Misconstrue The School District's

Obligations Under Decisions of

The Supreme Court and This Court ......... 2

III The HISD Is Not a Unitary School

District .................................. 8

IV CONCLUSION ................................ 15

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..... 3

Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F.2d 717 (5th Cir. 1975) ........ 14

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S 449

(1979) ........................................... 3

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) .................... 3,5,11,12

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 520

F.2d 1260 (5th Cir. 1978) ..................... 5,10,11,14

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) ................................... 4,10,12

Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S.

430 (1963) ......................................

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ......................................... 7,9,14

Pullman Standard v. Swint, U.S. (Nos. 80-1190

30-1193 April 27, 1982), 50 U.S.L.W. 4425 .....

&

9, 14

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 537

F.2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976) .......................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................ 1,2,3,5,12

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978) ....... 6,10,11

U.S. v. Texas Education Agency, 600 F.2d 518

(5th Cir. 1979) ................................. . 9,10,14

- l l -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-2323

DELORES ROSS, et al,

Appellants,

v.

HOUSTON INDEPENDENT SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court For The

Southern District of Texas

Houston Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

ARGUMENT

I.

Introduction

This is a case in which the last desegregation order was

issued in 1970 before Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), was decided and in which the

learning of that case has never been applied. The limited

pairing ordered in 1970 by this Court involved predominantly

black and hispanic schools, and could not and did not work to

desegregate either the specific schools or the system as a

whole. The only additional desegregation measure undertaken by

HISD since 1970 has been a magnet plan which has proved ineffec

tive.

This is not a case in which all possible Swann remedies

have been considered, or tried and not produced any success.

Rather this is a case in which (a) there was prior legally

imposed segregation; (b) a failure to use recognized desegrega

tion tools; and (c) continuous segregation from 1954 to now.

HISD is different from other southern school districts which

have actually tried to desegregate. A finding of unitary

status is therefore totally illogical: if a district never

tries to desegregate properly, how can a court find that further

desegregation cannot be accomplished?

II.

The HISD and the District Court

Misconstrue The School District's

Obligations Under Decisions of

The Supreme Court and This Court

The HISD disputes the extent to which it is required by

Swann to attempt to utilize the student assignment techniques

discussed in that case. It suggests that the attempt to

utilize those techniques is not required, and that what Swann

says is that their utilization is merely permissible.

2

(Appellees' Brief pp. 15-16). This characterization of the

school district's duty misstates its obligations under decisions

of the Supreme Court and this Court, and the extent to which

school districts are obligated to attempt to eliminate the

vestiges of former dual systems. All of the decisions of

the Supreme Court since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954), have made forcefully clear that school districts

dismantling former dual systems are to make maximum efforts to

eliminate the effects of those former discriminatory systems.

In Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968),

the Supreme Court said that school authorities are "clearly

charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps might

be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial

discrimination would be eliminated root and branch." 391

U.S. at 437-38. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq Board of

Education, supra 402 U.S. 1, Chief Justice 3urger for the

unanimous Court stated that the school ooard's objective

is to "eliminate from the public school all vestiges of state

imposed segregation." 402 U.S. at 15. In Davis v. Board

of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971),

the Court similarly held that ". . . the District Judge or

school authority should make every effort to achieve the

greatest possible degree of actual desegregation, taking

into account the practicalities of the situation." 402 U.S. at

37. In Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S 449

(1979), the Supreme Court affirmed that "the Board's continuing

3

affirmative duty to disestablish the dual system [is] beyond

question." 443 U.S. at 460.

Where a racially discriminatory school

system has been found to exist, Brown II

imposes the duty on local school boards

to 'effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system.' 349 U.S.

[2941], 301 ...

'Brown II was a call for the dismantling of

well-entrenched dual systems,' and school

boards operating such systems were 'clearly

charged with the affirmative duty to take

whatever steps might be necessary to convert

to a unitary system in which racial dis

crimination would be eliminated root and

branch.' Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430, 437-438. Each instance of a

failure or refusal to fulfill this affirma

tive duty continues the violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. 443 U.S. at 458-9.

Finally, in Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) the duty of a school board to provide effective

nondiscriminatory relief from the vestiges of a former dual

system was emphasized once again. The Court stated that,

[T]he measure of the post-Brown I conduct

of a school board under an unsatisfied duty

to liquidate a dual system is the effective

ness, not the purpose, of the actions in

decreasing or increasing the segregation

caused by the dual system. . . . As was

clearly established in Keyes and Swann, the

Board had to do more than abandon its prior

discriminatory purpose . . . The board has

an affirmative responsibility to see that

pupil assingment policies and school con

struction and abandonment policies 'are not

used and do not serve to perpetuate or

reestablish a dual school system,' Columbus, ante, at 460. . . 433 U.S. at 538.

4

In meeting these obligations, Swann makes clear that

school districts must "necessarily be concerned with the

elimination of one-race schools." 402 U.S. at 26.

No per se rule can adequately embrace all

the difficulties of reconciling the com

peting interests involved; but in a system

with a history of segregation the need for

remedial criteria of sufficient specificity

to assure school authority's compliance with

its constitutional duty warrants a presump

tion against schools that are substantially

disproportionate in their racial composi

tion. Where the school authority's proposed

plan for conversion from a dual to a unitary

system contemplates the continued existence of

some schools that are all or predominantly of

one race, they have the burden of showing that

such school assignments are genuinely nondis-

criminatory. The court should scrutinize

such schools, and the burden upon the school

authorities will be to satisfy the court that

their racial composition is not the result of

present or past discrimintory action on their

part. Id.

In construing this particular requirement of Swann, this Court

made clear what it would require in Davis v. East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board, 520 F.2d 1260 (5th Cir. 1978).

In the absence of explicit and specific find

ings by the district- court, we are unable to

determine whether the school board has met its

burden and whether these schools have been

subjected to the close scrutiny that was re

quired prior to declaring that a school system

passes constitutional muster . . . At a

minimum, the district court on remand must

evaluate whether any of the essentially one-

race schools would be eliminated by the remedial

altering of attendance zones or the pairing

and clustering of noncontiguous school zones.

See Swann, 402 U.S. at 27-29 and n.10; [cita

tions omitted]. These are only examples of

the permissible tools that may be used to

integrate a school system. The district

court is directed to consider the possible

5

alternatives to the neighborhood school concept

and to make findings regarding the feasibility

and efficacy of implmenting one or a combina

tion of these alternatives. As this Court has

repeatedly stated, 'The findings and conclu

sions we review must be expressed with suffi

cient particularity to allow us to determine

rather than speculate that the law has been

correctly applied.' Gulf City, Inc, v. Wilson

Sporting Goods Co., 555 F.2d 426, 433 (5th Cir.

1977) (quoting Hydro Space Challenger, Inc, v.

Tracor/MAS, Inc., 520 F.2d 1030, 1034 (5th Cir.

1975) ). 570 F.2d at 1264.

See also, Tasby v. Estes. 572 F.2d 1010, 1014-15 (5th Cir. 1978)

(Quoted in Appellant's Brief at 23-24).—^

A school board does not escape its obligation to "make

every effort" to eliminate all vestiges of the former dual

system by showing that the continued existence of numbers of

one—race schools is the result of patterns of residential

segregation. The Supreme Court has noted the profound effect

that discrimination in the operation of public schools has

on residential patterns.

People gravitate toward school facilities,

just as schools are located in response to the needs of people. The location of

schools may thus influence the patterns of

residential development of a metropolitan

area and have important impact on composi

tion of inner city neighborhoods. Swann,

supra, 402 U.S. at 20-21.

1/ HISD suggests that this case law is inapplicable because

of the district's size (p. 18). This is insupportable. The

principle of these cases — that an order relieving a former de

3 system from the obligation to take further action to

eliminate the vestiges of the dual system must be grounded in

explicit and specific findings that all practicable steps have

been taken — is appropriate regardless of the size or other

characteristics of a school district.

6

Similarly, in the Denver case, the Court said,

. . . [T]he practice of building a school

. . . to a certain size and in a certain

location, 'with conscious knowledge that

it would be a segregated school,' . . .

has a substantial reciprocal effect on the

racial composition of other nearby schools.

So also, the use of mobile classrooms, the

drafting of student transfer policies, the

transportation of students, and the assign

ment of faculty and staff, on racially

identifiable bases, have the clear effect

of earmarking schools according to their

racial composition, and this, in turn,

together with the elements of student assignment and school construction, may

have a profound reciprocal effect on the

racial composition of residential neigh

borhoods within a metropolitan area,

thereby causing further racial concentra

tion within schools. Keyes v. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 201-202

(1973).

In view of this obvious connection between school board

actions and residential patterns, the burden on a school board

is an extremely heavy one. It was spelled out in Keyes.

Intentional school segregation in the past

may have been a factor in creating a natural

environment for the growth of further segregation. Thus, if respondent School Board

cannot disprove segregative intent, it can

rebut the prima facie case only by showing

that its [present and] past segregative

acts did not create or contribute to the

current segregated condition of the core city

schools. 413 U.S. at 211.

Thus, it is not enough for a school board to suggest that one-

race schools are the result of housing patterns. It is the

burden of school authorities to show that "the current segrega

tion is in no way the result of [its] past segregative actions

413 U.S. at 211, n.17 (emphasis added). Thus a school board

must show by a preponderance of the evidence that its discrimina

tory actions in operating the public schools did not contribute

in any way to existing segregation. U.S. v. Texas Education

Agency, 600 F.2d 518 (5th Cir. 1979).

Ill

The HISD Is Not a Unitary School District

The district court did not, and could not, from the present

record, make the requisite findings to support its conclusion

that HISD has taken all practicable steps to eliminate the

2/vestiges of the former dual system.-

In our Brief for Appellants we contend that HISD and the

district court blamed the continued existence of large numbers

of one-race schools on white flight (p. 26). HISD disputes this

3/contention m their brief (Appellees' Brief at 19-20). - instead

2/ During the 1970's the original plaintiffs depended on the

leadership of the federal government, with its greater resources

for the prosecution of this action. Because no appeal was taken

by the government from the district court's orders involved

herein plaintiffs have reassumed the leading role.

3/ The record is replete with references to white flight as

being a principal cause of the continued existence of the dual

system (See Supt. Reagan, Tr. 1774; 1976-8; J. Angle, Tr.

1756-7). Moreover, Supt. Reagan relies on the mere spectre of white flight as an excuse for HISD not even attempting to

do more to eliminate the vestiges of the dual system (Tr.

1772-4). See, Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 537

F.2d 800, 802 (5th Cir. 1976), "In choosing between various

permissible plans a chancellor may ... elect one calculated to

minimize white boycotts.... He may not refuse to adopt a permissible plan and elect or confect one which preserves a dual

system because of such fears."

8

HISD contends that the continued presence of large numbers of

one-race schools is due to housing patterns for which it is not

responsible (Appellees' Brief at 20-22). The district court's

finding also on this basis that the "one-race schools remaining in

the HISD are not vestiges of the dual system” (R. 818, p. 30)

is clearly erroneous* Pullman Standard v. Swint, ___ U.S. ___

(Nos. 80-1190 & 80-1193 April 27, 1982), 50 U.S.L.W. 4425. As

we have argued above (pp. 6 to 8), due to the obvious connection

between school board actions and residential patterns, the

burden on school officials is an extremely heavy one when it

contends that it is absolved of any further duty to attempt to

eliminate one-race schools because of patterns of housing

segregation. It must show that "the current segregation

is in no way the result of [its] past segregative actions."

Keyes v. School District No. 1, supra 413 U.S. at 211, n.17

(emphasis added). This the district court failed to do. While

a voluminous amount of testimony was offered by HISD concerning

the location of schools, none of it addressed this issue, e.g.,

the extent to which school board action has contributed to

patterns of residential segregation. On cross examination,

defendants' own expert, Dr. Barton A. Smith, affirmed that

segregation in the public schools contributes to segregated

housing patterns. (Tr. 1315-17; 1325-28). The district

court's decision should therefore be reversed and remanded

based on the of this Court's approach in U.S. v. Texas Education

Agency, supra 600 F.2d at 527-8, with instructions

9

to determine how much "incremental segregative effect" the School Board's intentional discrimi

natory acts had on the residential distribution of the ... school population as presently

constituted, when the distribution is compared

to what it would have been in the absence of such intentional segregative acts. Dayton I,

supra, 433 D.S. at 420. In making specific

findings concerning the effects, if any, of the

intentional discriminatory acts on ... housing

patterns, the district court should also spe

cifically find: (1) whether it is significant

that the minority schools unaffected by the

order are in close proximity to schools at which

intentional segregation was found, and (2)

whether the location of the schools in question

in areas near the original de jure segregated

schools indicate that such segregation con

tributed to the current segregative conditions.

On remand, the School Board continues to bear

the burden to show that its intentional segrega

tive acts did not contribute to the current

segregation of those schools.

We also argued in our brief (pp. 26-7) that' the

district court's decision should be reversed based on its

failure to comply with the requirements of this Court's decision

in Tasby v. Estes, supra 572 F.2d 1010. See also Davis v. East

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, supra 520 F.2d 1260. The

object of school desegregation litigation is "to restore the

victims of discriminatory conduct to the position they would have

occupied in the absence of such conduct." U.S. v. Texas Educa

tion Agency, supra 600 F.2d at 527. And the measure of the

conduct of a school board under an unsatisfied duty to liquidate

a dual system is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of the

action in decreasing or increasing the segregation caused by the

dual system." Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, supra 443

U.S. at 558.

10

The record in this case cannot support an inference that

'maximum efforts" were made to eliminate the effects of the

former system, even taking into account the practicalities of the

situation. Davis v. Board of Education of Mobile County, supra

402 U.S. at 37. The district court failed completely to make

any of the specific findings required by Tasby or Davis v. East

Baton Rouge School Board that would make its unitary finding

reviewable. No analysis was done of racially identifiable

schools by HISD or the district court to determine whether their

4/status could be changed by use of any of the Swann tools.-

Superintendent Reagan conceded that this wasn't done from

1975-79 (Tr. 2065-6), but suggested that the 1974-75 Citizens

Task Force might have done so (Appellees' Brief, p. 25).

However, the only member of the Task Force to testify at the

1979 hearing, Macario Ramirez, said such an analysis had not

been done (Tr. 2708-10, 2750-51).

HISD's rejection of any consideration of the use of

pairing is entirely disingenuous. Superintendent Reagan rejects

it categorically because of HISD's experience with pairing in

the 1970 plan. The pairing at that time was ordered by this

Court and resulted in the pairing of minority schools (Tr. 1773—

74; Appellees' Brief at 27). Under Tasby and Davis v. East

4/ Appellees' suggestion (p. 12) that this Court could

determine the infeasibility of any busing by "a review at the

maps of existing transportation routes" is improper and should

be rejected.

Baton Rouge School Board, such a categorical rejection of

pairing based on this indeterminate first experience cannot be

sustained. A different approach to pairing might produce

a different, and satisfactory result.

HISD's contention that its reliance on a voluntary plan

based on magnet schools and a majority to minority transfer pro

vision is sufficient should also be rejected. (See Appellants'

Brief at 20-31). It may be that in some circumstances, such an

approach would be acceptable "taking into account the practi

calities of the situation.” Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, supra 402 U.S. at 37. On this record,

however, in light of the absence of findings with the necessary spe

cificity as to the feasibility of other approaches, such a plan is

inadequate. While the Citizens' Task Force that recommended

the magnet school approach may have acted in good faith, it is

the effectiveness, not the purpose of such a plan in accomplish

ing desegregation that is dispositive. Dayton Board of Education

v. Brinkman, supra 443 U.S. at 538. HISD's magnet school

approach is not acceptable when other of the Swann tools might

be both practicable and more successful in eliminating the

dual system. Since the magnet approach, by itself, is demon

strably unsuccessful (see Appendix A-D for a historical analysis

of the success of the magnet school approach), HISD is obligated

to consider other remedies.

12

Appellees exaggerate the success of the magnet school

program as a desegregation device when they assert that the

total number of students "impacted by the magnet school programs

in 1979 was 69,393 "(Appellees' Brief at 11). In fact, only

3,292 were majority to minority transfers that enhanced desegrega

tion (HISD Ex. 68, p. 6; Tr. 1027-28). Moreover, as was suggested

by plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Gary Orfield, and the studies of Mark

. 5/D. Smylie (Appellants' Brief at 28-30), there is at a minimum

no basis for concluding that the magnet program would not be

more effective when combined with clustering, non-contiguous

pairing, educational parks, and similar techniques.

Similarly, while HISD's efforts to enhance the quality of

education are laudable and to be encouraged, these efforts do

not relieve the district from its constitutional obligation to

remove the dual system.

Although efforts to improve the quality of

education for all students is desirable,

this emphasis fundamentally misapprehends

the constitutional requirement of achiev

ing a unitary school system. The achieve

ment of quality education is not premised

on the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Prior to Brown v.

Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 ... (1954), it

had been urged that quality education

could be made available to all students

without integration. Separate but equal

5/ In their brief appellees challenge the validity of the

Smylie Study (p. 30). The reference to "1980" in the Study

about which they complain refers to the year the data in the

Study was reported to HEW. The 1980 data were the enrollment

figures for the 1980-81 school year. This information was

confirmed by Mark A. Smylie in a conversation with the under

signed counsel.

-1 3

concepts have now long been rejected.

Federal courts lack jurisdiction under

the Fourteenth Amemdment to require qual

ity education in state school districts

other than to erase the effects of prior

school segregation. The sole goal of

Brown is to erase the dual educational

system and achieve unitary schools.

Liddell v. Caldwell, 546 F.2d 76 , 77

n.10 (8th Cir. 1976).

The district court's finding that HISD has done all things

practicabel to eliminate the dual system should therefore be

rejected as clearly erroneous, Pullman Standard v. Swint, supra

50 U.S.L.W. 4425, and the case remanded with instructions to the

district court to consider the feasibility of other remedies in

conformity with this Court's decision in U.S. v. Texas Education

Agency, supra, Davis v. East Baton Rouge School Board, supra,

6/and Tasby v. Estes, supra.~

6/ To the extent appellees rely on the decision in Calhoun v.

Cook, 522 F.2d 717 (5th Cir. 1975), we submit it was wrongly

decided. See Keyes v. School District No. 1, suora 413 U.S. at 200, n.1.

14

IV

CONCLUSION

For all the reasons stated above and in Appellants' Brief

the decision of the district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG1

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

LOWELL JOHNSTON

BILL LANN LEE

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

WELDON H. BERRY

711 Main Street

Houston, Texas 77002

Attorneys for Appellants

15

DE JURE BLACK SCHOOLS INTO WHICH MAGNETS WERE PUT

BURRUS EL.

YEAR B H W I %B %MI

1974-75 543 101 35 679 80 95

75-76 755 41 40 836 90 95

76-77 701 42 36 779 90 95

77-78 747 52 43 842 89 95

78-79 793 81 40 914 87 96

1980-81 630 68 34 733 86 95

1981-82 625 67 37 730 86 95

BRUCE EL.

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974-75 611 129 1 611 79 100

75-76 461 22 6 461 94 99

76-77 502 65 18 502 84 96

77-78 534 108 54 534 68 90

78-79 655 124 151 655 58 77

1980-81 337 175 11 624 54 82

1981-82 307 182 10 604 51 98

APPENDIX A

CRAWFORD EL

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974-75 423 289 3 715 59 100

75-76 402 5 6 413 97 98

76-77 425 5 5 435 98 99

77-78 460 36 15 511 90 97

78-79 490 48 11 549 89 98

1980-81 436 60 6 502 87 99

1981-82 374 49 25 448 84 94

DODSON EL. -

YEAR E H W I %B %MIN ,

1974-75 551 278 44 873 63 95

• 75-76 949 24 5 978 97 100

76-77 753 46 35 834 90 96

77-78 789 57 37 883 89 96

78-79 772 48 45 865 89 95

1980-81 586 ';9 54 749 78 93

1981-82 502 82. 69 728 69 90.5

J . W. JONES EL •

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN .

1974-75 326 37 6 369 88 98

75-76 342 47 9 398 86 98

76-77 355 72 22 449 79 95

77-78 375 68 18 461 81 96

78-79 379 73 24 476 80 95

1980-81 281 80 20 381 74 95

1981-82 411 128 24 563 73 96

APPFNDTX A —7

PLEASANTVILLE EL

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974.-75 312 105 66 483 65 86

75-76 482 19 50 551 88 91

76-77 482 78 46 606 80 92

77-78 482 49 63 592 81 89

78-79 465 35 54 554 84 90

1980-81 393 62 64 524 75 88

1981-82 371 62 43 481 77 91

FLEMING JR. HIGH

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974-75 860 110 0 970 89 100

75-76 897 86 0 983 91 100

76-77 934 131 24 1089 86 98

77-78 975 146 37 1158 84 97

78-79 920 189 36 1145 80 97

1980-81 807 184 66 1086 74 94

1981-82 803 199 59 1090 74 95

MC WILLIAMS JR. HIGH

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN ,

1974-75 477 12 15 504 95 97

75-76 521 5 15 541 96 97

76-77 491 12 12 515 95 98

77-78 503 4 4 511 98 99

78-79 477 3 9 489 98 98

1980-81 561 13 16 591 95 97

1981-82 591 14 9 614 96 98

APPENDIX A—3

BT WASHINGTON H.S

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974-75 786 2 12 800 98 98

75-76 916 3 12 931 98 98

76-77 863 11 27 901 96 97

77-78 708 46 114 868 82 87

78-79 1614 54 71 1739 93 96

1980-81 1470 74 100 1662 88 94

1981-82 1559 81 98 1759 89 94

YATES H.S.

YEAR B H W I %B %MIN

1974-75 1617 0 4 1621 100 100

75-76 1446 0 0 1446 100 100

76-77 1328 0 1 1329 100 100

77-78 1443 0 0 1443 100 100

78-79 1337 0 3 1340 100 100

1980-81 2395 20 20 2435 98 99

1981-82 2412 22 29 2467 98 99

APPENDIX A-4

SCHOOLS WITH MAJORITY MINORITY ENROLLMENTS (OVER 90%)*

BY 1974--75 IN WHICH MAGNETS WERE PUT

A. JONES EL.

Year B H W T % B % W % Min.

1974--75 165 122 4- 291 57 1 99

1975-76 201 259 33 4-93 XI 7 93

1976-77 222 335 4-1 598 37 7 93

1977-78 205 363 71 639 32 11 89

1978-79 171 4-11 88 670 26 13 87

1980-81 177 4-22 14- 729 24- 2 98

1981-82 114- 333 6 571 20 1 99

MacGREGOR EL.

Year B H W T °/£ B % W % Min.

1974--75 339 19 31 389 87 8 92

1975-76 412 17 64 493 84 13 87

1976-77 446 12 58 516 87 11 89

1977-78 450 22 81 553 81 15 85

1978-79 433 29 92 554 78 17 83

1980-81 457 27 41 527 87 8 92

1981-82 453 32 29 515 88 6 94

LANTRIP EL.

Year B H W T °/£ B % W % Min.

1974-75 319 324 79 722 44 11 89

1975-76 38 650 128 816 5 16 84

1976-77 65 716 140 921 7 15 85

1977-78 63 762 83 908 7 9 91

1978-79 47 825 74 946 5 8 92

1980-81 29 973 68 1090 3 6 94

1981-82

PORT HOUSTON EL.

Year B H W T °/6 B % W % Min.

1974— 75 163 167 21 351 46 6 94

1975-76 10 293 32 335 3 10 90

1976-77 15 317 50 382 4 13 87

1977-78 16 312 53 381 4 14 86

1978-79 28 336 60 424 7 14 86

1980-81 42 278 22 368 11 6 94

1981-82 11 339 31 412 3 8 92

*A11 schools were over 90% minority in 1974.-75 except 1 —

it was 89% minority (Lantrip)

APPENDIX B

PUGH EL

Year B H W T % B % W % Min

1974-75 351 343 44 738 48 6 94

1975-76 4-5 666 64 775 6 8 92

1976-77 39 705 63 807 5 8 92

1977-78 30 772 52 854 4 6 94

1978-79 19 724 40 783 2 5 95

1980-81 16 688 33 785 2 4 96

1981-82 31 748 31 902 3 3 97

Year B H

ROSS

W

EL.

T % B % W % Min

1974-75 323 240 17 580 56 3 97

1975-76 526 80 16 622 85 3 97

1976-77 578 72 27 677 85 4 96

1977-78 568 81 38 687 83 6 94

1978-79 524 85 42 651 31 6 94

1980-81 545 121 40 706 77 6 94

1981-82 500 128 56 685 73 8 92

SCROGGINS EL.

Year B H W T % B % W % Min

1974-75 200 555 62 817 25 8 92

1975-76 59 567 55 681 9 8 921976-77 58 589 57 704 8 a 92

1977-78 55 598 60 713 8 8 921978-79 84 580 59 723 12 3 921980-81 54 586 29 673 8 4 961981-82 60 597 56 718 8 8 92

Year B H

JONES HS

W T % B % W % Min

1974-75 1521 77 89 1687 90 5 951975-76 1524 55 63 1642 93 4 961976-77 1622 18 30 1670 97 2 981977-78 1877 24 71 1972 95 4 961978-79 1899 23 95 2017 94 5 951980-81 1557 29 78 1672 93 5 951981-82 1453 40 58 1562 93 4 96

APPENDIX B-2

DAVIS HS

Year B H W T % B % W % MIN

1974.-75 594- 677 83 1354 44 6 94

1975-76 517 629 68 1214 43 6 941976-77 563 668 78 1309 43 6 941977-78 516 657 54 1227 42 4 961978-79 454- 627 40 1121 41 4 96

1980-81 4-44- 570 24 1069 42 2 981981-82 516 821 26 1435 36 2 98

APPENDIX B-3

WHITE* OR POST 1974-75 SCHOOLS

INTO WHICH MAGNETS PUT

Year

1976- 77

1977- 78

1978- 79

1980- 81

1981- 82

Year

1978-79

1980- 81

1981- 82

Year

1978-79

1980- 81

1981- 82

Year

1974- 75

1975- 76

1976- 77

1977- 78

1978- 79

1930-31

1981-32

*A11 the

ASKEW EL.

B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

36 21 499 NA 556 6 10 9049 36 715 NA 800 6 11 89117 64 971 NA 1152 10 6 84139 110 710 48 1007 14 30 70176 126 719 60 1081 16 33 67

K. BELL EL.

B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

75 16 560 NA 651 12 14 86182 35 520 112 849 21 39 61168 49 427 94 738 23 42 58

B H

CODWELL EL.

W 0 T % B % Min. % W

719 2 3 NA 724' 99 100 0780 4 10 0 794 98 99 1735 4 29 0 768 96 96 4

LONGFELLOW EL.

B H W 0 T % B «& Min. % W

13 23 279 NA 315 4 11 8916 30 263 NA 309 5 15 85111 36 255 NA 402 28 37 63128 33 244 NA 405 32 40 60176 ■ 31 221 NA 428 41 48 52206 54 187 15 462 45 59 41143 54 163 18 378 38 57 43

pre-1974 schools on this list were above 74% white.

APPENDIX C

OAK FOREST EL

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1974—75 35 72 516 NA 623 6 17 83

1975-76 51 85 4-83 NA 619 8 22 781976-77 82 95 437 NA 614 13 29 71

1977-78 125 98 426 NA 649 19 34 66

1978-79 120 115 403 NA 638 19 37 631980-81 178 125 268 4 575 31 53 47

1981-82 179 125 264 7 575 31 54 46

Year B H W

PARKER EL.

0 T % B % Min. % W

1974-75 16 23 745 NA 784 2 5 951975-76 121 41 712 NA 874 14 19 811976-77 134 64 641 NA 839 16 24 761977-78 177 73 552 NA 802 22 31 691978-79 196 96 556 NA 848 23 34 661980-81 290 106 440 7 843 34 48 521981-82 244 112 360 13 729 34 51 49

Year B H

ROBERTS EL.

W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1974-75 105 13 342 NA 460 23 26 741975-76 105 15 290 NA 410 26 29 711976-77 163 21 265 NA 449 36 41 591977-78 199 24 265 NA 488 41 46 541978-79 188 27 268 NA 483 39 44 561980-81 233 37 195 22 487 48 60 401981-82 179 44 134 10 367 49 63 37

T. H. ROGERS EL .

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1980- 81

1981- 82

12 4 123 12 151 8 18 82

APPENDIX C-2

WAINWRIGHT EL.

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1974-75 31 65 544 NA 640 5 15 85

1975-76 67 60 502 NA 629 11 20 80

1976-77 74 59 488 NA 621 12 21 79

1977-78 76 76 412 NA 564 14 27 73

1978-79 100 103 382 NA 585 17 35 65

1980-81 93 101 250 13 457 20 45 55

1981-82 95 112 201 17 425 22 53 47

CLIFTON MIDDLE

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1980-81 339 318 575 25 1257 27 54 461981-82 419 306 610 18 1353 31 55 45

HOLLAND MIDDLE

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1980-81 341 409 284 8 1042 33 73 27

1981-82 457 414 251 48 1170 39 79 21

REVERE MIDDLE

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1980-81 138 150 1513 95 1896 7 20 801981-82 198 169 1483 102 1952 10 24 76

WELCH JR. HIGH

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1980-81 527 155 713 61 1456 36 51 49

1981-82 535 180 822 78 1615 33 49 51

APPENDIX C-3

BELLAIRE HS

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1974-75 76 57 2118 NA 2251 4 6 941975-76 110 78 2074 NA 2262 5 8 921976-77 152 116 2035 NA 2303 7 12 881977-78 175 137 1889 NA 2201 8 14 861978-79 197 133 1721 NA 2051 10 16 841980-81 242 146 1367 96 1851 13 26 741981-82 280 200 1736 157 2373 12 27 73

MILBY HS

Year B H W 0 T % B % Min. % W

1974-75 100 392 1511 NA 2003 5 25 751975-76 117 407 1407 NA 1931 6 2 7 731976-77 132 453 1324 NA 1909 7 31 691977-78 159 503 1181 NA 1843 9 36 641978-79 192 571 1049 NA 1812 11 42 581980-81 431 1063 923 63 2480 17 63 371981-82 466 1280 764 96 2606 18 71 29

APPENDIX C-4

INTEGRATED SCHOOLS INTO WHICH MAGNETS WERE PUT

Cornelius El.

Year 3 H W T %B %W %Min

1974-75 92 148 271 511 18 5 3 47

75-76 117 127 267 513 23 52 437 6-77 122 143 236 561 33 42 5877-78 225 159 239 623 36 38 6278-79 319 165 236 720 44 33 67

30-81 329 264 143 749 44 19 8181-82 275 272 219 772 36 28 72

3erry El.

Year 3 H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 302 268 279 849 36 33 6775-76 306 279 259 844 36 31 6976-77 297 296 251 844 35 30 7077-78 302 316 222 840 36 26 7473-79 309 387 186 882 35 21 7980-81 313 526 135 976 32 14 8681-82 33 6 5 29 138 1104 30 13 87

Burbank El.

Year 3 H w T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 141 235 502 878 16 56 4475-76 157 256 463 876 18 53 4776-77 139 301 490 930 15 53 4777-78 124 281 501 906 14 55 4578-79 169 333 475 977 17 49 5180-31 2Q9 443 393 1061 20 37 5 331-82 250 491 357 1110 23 32 58

APPENDIX D

Garden Villas El.

Year 3 H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 263 103 339 705 37 48 5275-75 315 109 271 695 45 39 6176-77 292 113 234 639 46 37 6377-78 302 146 215 6 6 3 46 32 6878-79 273 144 195 612 45 32 6830-81 308 207 187 710 43 26 7481-82 315 184 205 711 44 29 71

Poe> El.

Year 3 H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 207 12 198 417 50 48 5275-76 218 22 276 516 42 53 4776-77 197 46 364 607 33 60 4077-78 224 55 428 707 32 61 3978-79 252 83 409 744 34 55 4580-81 328 117 338 792 41 43 57

31-82 249 123 263 644 39 41 59

Year B H

River

W

Oaks El.

T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 123 53 321 497 22 67 3375-76 146 80 285 511 29 56 4476-77 193 99 290 5 S 2 33 50 5077-78 203 106 271 580 35 47 5378-79 247 136 242 625 40 39 6180-31 236 167 167 594 40 28 7281-32 149 163 201 5 6 4 26 36 64

Year 3 H

Roge

W

rs El.

T %3 %W %Min.19 73"-T5 169 33 305 507 33 50 4075-76 228 45 313 586 39 53 4776-77 282 101 254 637 44 40 6077-78 213 85 166 464 46 36 6478-79 195 75 125 395 49 32 6880-81 194 162 170 535 36 32 6831-82 257 186 158 624 41 25 75

APPENDIX D-2

Roosevelt El

Year B H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 215 94 47 356 60 13 8775-76 127 223 131 481. 26 27 7376-77 159 258 157 574 28 27 7377-78 147 301 138 586 25 24 7678-79 146 346 119 611 24 20 8080-81 170 442 88 704 24 13 8781-82 170 463 88 721 24 12 88

Wilson El -

Year 3 H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 3 105 215 323 1 67 3375-76 3 84 183 270 1 68 3276-77 20 115 163 298 7 55 4577-78 20 74 145 239 8 61 3978-79 6 6 106 161 333 20 48 5280-81 63 121 135 344 18 40 6081-82 61 84 110 283 22 39 61

Windsor Village El.

Year B H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 251 109 254 614 41 41 5975-76 272 108 199 579 47 34 6676-77 326 122 200 648 50 31 6977-78 326 115 184 625 52 29 7178-79 393 139 191 723 54 26 7480-81 429 140 142 727 59 20 8031-82 393 118 162 710 55 23

Hamilton Jr. High

Year 3 H W T $3 %W %Min.

1974-75 322 338 768 1428 23 54 4675-76 354 396 781 1531 23 51 4976-77 40 7 451 731 1589 26 46 5477-78 430 467 607 1504 29 40 6078-79 548 442 509 1499 37 34 6680-81 501 412 304 1233 41 25 7581-82 393 437 292 1155 24 25 75

APPENDIX D-3

Lanier Jr. High

Year H W T %B %W %Min.

1.9 74-75 397 137 457 991 40 46 5475-76 485 261 658 1404 35 47 5376-77 522 230 629 1381 38 46 5477-78 544 253 550 1347 40 41 5978-79- 536 270 494 1300 41 38 6280-81 585 323 352 1313 45 27 7381-8 2 679 336 430 1510 45 29 71

Hartman Jr. High

Year B H W T %E %W %Min.

1974-75 1147 208 689 2044 56 34 6 675-76 1300 220 508 2028 64 25 7576-77 1301 196 316 1813 72 18 8277-78 1386 213 248 1847 75 14 3 678-79 1283 208 198 1689 76 12 8880-81 1029 177 120 1331 77 9 9181-82 1036 204 120 1370 76 9 91

Burbank Jr. High

Year B H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 461 277 438 1176 39 37 5 375-76 464 331 396 1191 39 33 5776-77 506 366 360 1232 41 29 7177-78 523 328 254 1105 47 23 7778-79 486 366 232 1084 45 21 7980-31 418 437 243 1109 38 22 7881-82 367 547 256 1177 31 22 73

Reagan Sr. HS

Year B H W T %B %W %Min.

1974-75 260 357 691 1308 20 53 4 775-76 261 422 574 1257 21 46 5476-77 304 488 517 1309 23 40 6 077-78 337 585 479 1401 24 34 6678-79 330 648 410 1388 24 30 7080-81 457 309 364 1723 27 21 7981-82 445 822 324 1729 26 19 81

Sterling HS

Year 3 H W T %B %W % M m .

1974-75 1106 38 303 1441 77 21 7975-76 1161 40 199 1400 83 14 8676-77 1244 36 146 1426 87 10 9077-78 1294 47 103 1444 90 7 9 378-79 1396 58 84 1538 91 5 9580-81 1389 73 61 1529 91 4 9681-82 1393 57 76 1532 91 5 95

l U D U H n T V r v _ / 1

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on this the J day of July,

1982, two copies of the foregoing REPLY BRIEF were served

on counsel to the parties by United States mail, postage

prepaid, addressed as follows:

William Key Wilde

Kelly Frels

2900 South Tower Pennzoil Plaza

Houston, Texas 77002

Burt Dougherty

Q.S. Justice Department

Civil Rights Division

Washington, D.C. 20001

Peter D. Roos

Mexican-American Legal Defense &

Educational Fund

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

Robert E. Hall

Bob Hall & Associates

5850 San Felipe

Houston, Texas 77057

Joseph D. Jamail

3300 One Allen Center

Houston, Texas 77002

Edward Mallett

Pape & Mallett

Suite 600

1929 Allen Parkway

Houston, Texas 77019

Sydney L. Ravkind

Mandell & Wright

21st Floor

806 Main Street

Houston, Texas 77002

3 t

\ - / J A ' { S IjT3

Attorney for Plaintiffs