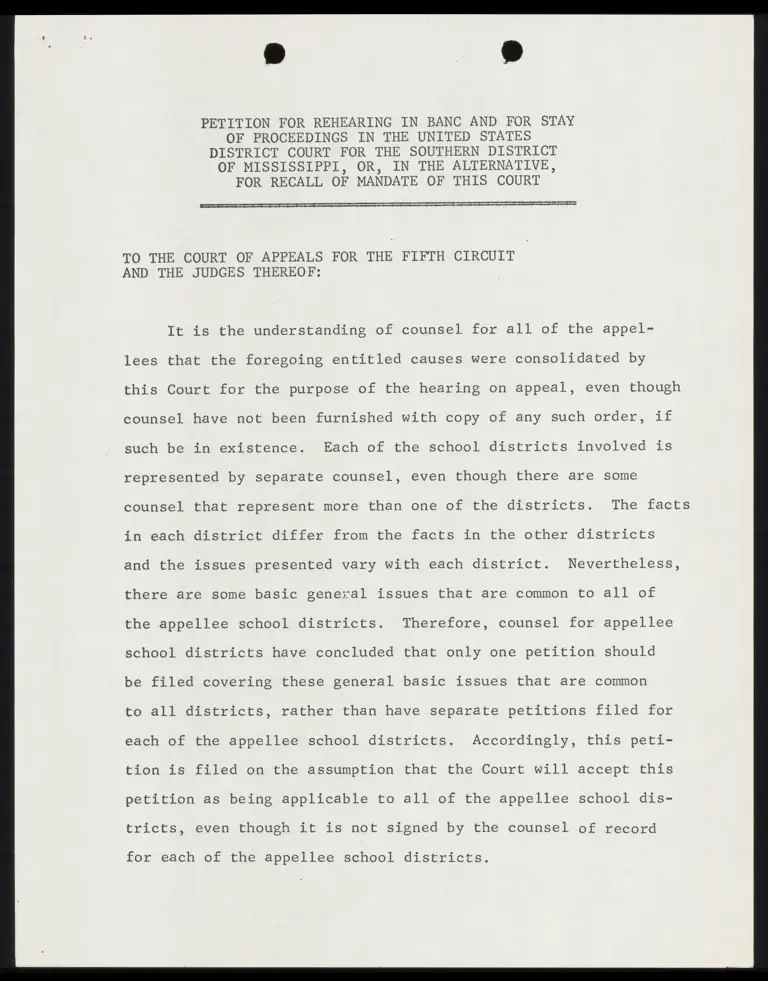

Petition for Rehearing in Banc and for Stay of Proceedings or, in the Alternative, for Recall of Mandate of this Court

Public Court Documents

July 14, 1969

30 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Petition for Rehearing in Banc and for Stay of Proceedings or, in the Alternative, for Recall of Mandate of this Court, 1969. ebb1f81d-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6abfd6b3-646c-4dbd-a7f0-c6282d254ca3/petition-for-rehearing-in-banc-and-for-stay-of-proceedings-or-in-the-alternative-for-recall-of-mandate-of-this-court. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

PETITION FOR REHEARING IN BANC AND FOR STAY

OF PROCEEDINGS IN THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT

OF MISSISSIPPI, OR, IN THE ALTERNATIVE,

FOR RECALL OF MANDATE OF THIS COURT

TO THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

AND THE JUDGES THEREOF:

It is the understanding of counsel for all of the appel-

lees that the foregoing entitled causes were consolidated by

this Court for the purpose of the hearing on appeal, even though

counsel have not been furnished with copy of any such order, if

such be in existence. Each of the school districts involved is

represented by separate counsel, even though there are some

counsel that represent more than one of the districts. The facts

in each district differ from the facts in the other districts

and the issues presented vary with each district. Nevertheless,

there are some basic general issues that are common to all of

the appellee school districts. Therefore, counsel for appellee

school districts have concluded that only one petition should

be filed covering these general basic issues that are common

to all districts, rather than have separate petitions filed for

each of the appellee school districts. Accordingly, this peti-

tion is filed on the assumption that the Court will accept this

petition as being applicable to all of the appellee school dis-

tricts, even though it is not signed by the counsel of record

for each of the appellee school districts.

This petition for a rehearing of the above entitled causes

is being filed with the belief and conviction that it is essen-

tial that the issues presented herein receive full and complete

consideration by this Court in banc, the proceedings in the

district court must be stayed or the mandate of this Court re-

called. This petition is being filed in accordance with Rule

40 and Rule 35 of the Rules of Appellate Procedure, and in sup-

port of this petition, your petitioners assert as follows:

1. The appellees have not been accorded due process of

law in this appeal.

2. Various panels of this Court have not been consistent

in their interpretation and application of the decision of

this Court rendered, in banc, in United States of America v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, 380 F.2d 385, and this

Court, sitting in banc, should establish what was meant by the

in banc decision of this Court in the Jefferson case, supra.

3 Various panels of this Court have not been consistent

in their interpretation and application of the decisions of the

United States Supreme Court in Green v. County School Board of

New Kent County, Virginia, 319 U.S. 430, 20 L.Ed.2d 716, 88

S.Ct. 1689; Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School District,

301 U.S, 433, 20 L..Fa.2d 727, 88 S.Ct. 1697; and Monroe v, Board

of Commissioners of the City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450,

20 1..Ed.24 733, 88 S.Ct. 1700; and this Court, sitting in banc,

should make an interpretation and application of those decisions

of the United States Suoweiie Court that can be uniformly ap-

plied.

4, These proceedings involve questions of exceptional

importance.

This is a petition, not a brief, and there should not be,

and therefore will not be, any extended discussion of the

issues involved. It is our intent and purpose, however, to

set forth sufficient of the issues to illustrate and demon-

strate the need for the grant of the relief sought by this

petition.

I, THE APPELLEES HAVE NOT BEEN ACCORDED DUE PROCESS OF

LAW IN THIS APPEAL,

The chronology of events in connection with the appeal to

this Circuit is as follows:

A. The district court, consisting of three judges,

for the Southern District of Mississippi, sitting in banc, ren-

dered its opinion on May 13, 1969.

B. The district court entered its order pursuant

to the foregoing opinion on or about May 16, 1969 in each of

the above referenced cases.

C., On May 28, 1969, the district court entered

additional findings of fact.

D. Attorneys for the private plaintiffs filed notice

of appeal and a motion for summary reversal on June 10, 1969.

E. The United States of America filed notice of

appeal on June 12, 1969 in the cases where the United States

d

o

-3e

of America was plaintiff but filed no motion for summary re-

versal in connection with said notice of appeal.

F. On June 10, 1969, notice was issued by the Clerk

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

to the attorneys for the school districts in which there were

private plaintiffs, that the motion for summary reversal would

be presented for ruling without oral argument on or about June

20, 1969, together with any response or opposition that may be

filed by opposing counsel by that date.

G. On June 23, 1969, the United States of America

filed a "Motion for Summary Reversal and Motion to Consolidate

" in the cases in which the United States of Appeals, etc.

America was plaintiff.

H. On June 23, 1969, the Clerk of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit mailed a letter to counsel

of record to the effect that the motion of the United States of

America had been filed and would be presented on or about July 3,

1969 together with any response or opposition that may be filed

by opposing counsel by that date. This notice was received by

some of the counsel on June 24, 1969 and other counsel on later

dates.

I. On June 24, 1969, the district court entered an

"order as to the appellate record" in which the district court

recognized that the record in these cases was voluminous and

that it would be "a Herculean task for the appellate court to

examine such a voluminous record in any reasonable length of

li

time". Accordingly, the district court ordered that appel-

lants' counsel was to file with the Clerk of the court within

five days a designation of so much of the record in each of the

cases that they desired to be used in the appeal. The district

court further ordered that within three days after receipt of

a copy of such designation by appellants' counsel, appellees’

counsel was to file a designation of those parts of the record

not previously designated which they deemed necessary for use

on appeal. The court further ordered that the Clerk should

have thirty days in which to prepare the record and to forward

same to the Clerk for the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

in New Orleans.

J. On June 25, 1969, the Clerk of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit addressed a letter to

counsel of record in all cases, including those in which there

were private plaintiffs and those in which the plaintiff was

the United States of America, to the effect that the Court would

hear oral argument on all of these cases '"'on the motion for

summary reversal and the merits in all of the cases both pri-

vate plaintiffs and those of the United States'. (Emphasis

added). This letter further advised that the argument would

be held in New Orleans beginning at 9:30 A.M., July 2, 1969,

and any memoranda or responses would have to be filed in the

office of the Clerk by noon, July 1, 1969, In this letter, it

was recited that the Court had taken notice of the district

court's order with respect to the record but that since appeal

was being expedited on the original record, the United States

attorney should make arrangements with the District Clerk to

transmit to the Clerk of the Court of Appeals the entire record

of the district court so that same would be available to the

Court if needed during the argument and summation. It was fur-

ther stated that the Court recognizes that ''this is a huge

record involving a large number of parties and matters of great

public interest and importance’.

K. The foregoing letter dated June 25, 1969 was re-

ceived by some of the counsel of record on June 26, 1969 and

by others on June 27, 1969. This meant that counsel had, at

best, Friday June 27, Saturday June 28, Sunday June 29, and

Monday June 30 to prepare any response, since it had to be filed

by noon, July 1, 1969.

L. Briefs filed by the United States of America

were received by some of the counsel on Monday, June 30, 1969

and by others on Tuesday, July 1, 1969. In addition, supple-

ments to the brief were delivered to counsel on the morning of

the hearing, July 2, 1969. Thus, counsel were afforded no oppor-

tunity whatsoever to examine or inspect same in order to reply

thereto either in writing or orally.

M. The proposed opinion-orders as submitted by the

private plaintiffs and the United States of America were not

submitted to nor seen by opposing counsel until the morning of

the hearing, July 2. Accordingly, there was no opportunity to

examine same or make any meaningful comments in regard thereto.

“Bw

N. The record in the district court was brought

into the courtroom and was present during the argument on

July 2. It is the understanding of counsel that this record

consisted of four large packing boxes and that these boxes

were still sealed as same had been sealed by the Clerk of the

district court and remained sealed during the entire argument.

0, The oral argument of counsel was concluded

during the middle of the afternoon of July 2.

P. The opinion of the panel of this Court was

entered July 3, 1969, applying to all of the cases.

It is submitted that the record in these cases has not

been examined by any member of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals. Yet, on July 1, 1969, another panel of the Fifth Cir~

cuit in Cause No. 27281, styled United States of America wv.

Board of Education of Baldwin County, Georgia, rendered an

opinion in which it was stated as follows:

"In the case now before the Court, we conclude, after

a study of the record, that the district court cor-

rectly decided that a freedom of choice plan was more

suitable than a zoning plan for Baldwin County, Georgia.

We base this conclusion on the county's racial resi-

dential patterns, the location of the schools and the

projections for 1969-70."

Thus, we have a clearcut illustration and demonstration

of, in one case, a panel of this Court examining the record

of a case and, after analysis of the facts of that particular

case, reaching a conclusion. No consideration was given by

the panel deciding these cases as to the facts as they exist

in any of these cases other than bare statistics;

and, in the panel's opinion which purported to cover statis-

tics in each of the districts involved, the Court omitted any

findings of statistics as to a number of the school districts

which were appellees.

VARIOUS PANELS OF THIS COURT HAVE NOT BEEN CON-

SISTENT IN THEIR INTERPRETATION AND APPLICATION OF

THE DECISION OF THIS COURT RENDERED, IN BANC, IN

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA V. JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION, 380 F.2d 385, AND THIS COURT, SITTING

IN BANC, SHOULD ESTABLISH WHAT WAS MEANT BY THE IN

BANC DECISION OF THIS COURT IN THE JEFFERSON CASE,

SUPRA,

More than sixteen decisions have been rendered by various

panels of this Court construing, restricting, extending, vary-

ing, or violating the principles laid down by the in banc deci-

sim of this Court in the Jefferson case, supra. For the

convenience of the Court, these decisions are listed in reverse

chronological order as follows: U.S.A. v. Hinds County School

Boaxd, et al., Nos. 28030 & 28042, July 3, 1969; U.S.A. v, Board

of Education of Baldwin County, Georgia, et al., No. 27281, July

1, 1969; U.S.A., et al. v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

et al,., No. 26584, July 1, 1969; U.8,A,, et al. v. Choctaw County

Board of Fducation, et al,, No. 27297, June 26, 1969; U.S.A, v.

Jefferson County Board of Edw ation, No. 27444, June 26, 1969;

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, No.

26886, June 3, 1969; Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board,

No. 26450, May 28, 1969; Anthony v. Marshall County Board of

Education, No. 26432, April 15, 1969; U.S.A. v. Indianola

Municipal Separate School District, No. 25655, April 11, 1969;

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District, No.

23255, March 6, 1969; Duval County Board of Public Instruction

v. Braxton, 402 F.2d 900, August 29, 1968; Adams v. Mathews,

403 F.2d 181, August 20, 1968; Acree v. Board of Education Rich-

mond County, 399 F.2d 151, July 18, 1958; U,8.A, v. Board of

Education of the City of Bessemer, 396 F.2d 44, June 3, 1968;

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District, 395 F.2d 817,

May 30, 1968.

In one of these cases, the U.S.A. v. Board of Education of

the City of Bessemer, supra, it was stated that the decision of

this Court in the Jefferson case, supra, had the status of an

in banc decision and could not be varied by any panel of the

Circuit. 1It is respectfully submitted that such has not been

the case. Certainly the decisions of this Court have not been

uniform or consistent in the application of what each respective

panel considered to be the controlling principle enunciated by

this Court sitting in banc in the Jefferson case, supra.

As an illustration, and solely as an illustration of this

point, we call the attention of the Court to the following:

A. There were originally before a panel of this

Court for an administration decision thirty-eight school dis-

tricts in the State of Louisiana and most of the districts in

Mississippi that are involved in this proceeding. After hear-

ings in the district court, a separate decision was rendered

by one panel in connection with the Louisiana cases and now

we

another opinion has been rendered by another panel in the Mis-

sissippi cases. The decision in the Louisiana cases is Hall

v. St. Helena Parish School Board, being Cause No. 26450, and

was rendered on May 28, 1969. In the Hall case, supra, the

panel stated that it was urged by appellant to.

"order on a plenary basis for all these school dis-

tricts that the District Court must reject freedom

of choice as an acceptable ingredient of any desegre-

gation plan."

The panel considering those cases declined to so order, refer-

ring to the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the

Green case, supra, and stated as follows:

"Again, the statistical evidence makes abundantly

clear that the freedom of choice plans as presently

constituted, administered and operating, are failing

to eradicate the dual system. (Emphasis added).

Thus, the district court was free to consider freedom of choice

plans that might be changed in the administration or operation.

Yet, in the decision of the panel considering these cases,

where obviously there has been no opportunity to examine and

review the record, this panel stated as follows:

"We hold that these school districts will no longer

be able to rely on freedom of choice as the method

for disestablishing the dual system."

We again point out that just two days before, on July 1

b]

1969, another panel of this Court in the Baldwin County case,

supra, decided that, based upon the facts as they existed in that

particular school district, which facts did not deal with sta-

tistics, the freedom of choice plan was more suitable than any

other plan available to the district. This was done even though

it was acknowledged there would still be all-Negro schools in

the district. It is submitted that an examination of the

opinions of the various panels of this Court in the decisions

of U.S.A. v. Jefferson County Board of Education, Cause No.

26584, decided July 1, 1969; U.S.A. v. Choctaw County Board of

Education, Cause No. 27297, decided June 26, 1969; and U.S.A.

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, Cause No. 27444, decided

June 26, 1969; along with the decision of the panel in the case

of U.S.A. v. Board of Education of Baldwin County, Cause No.

27281, decided July 1, 1969, demonstrates an inconsistent appli-

cation of the various panels of this Court as to what is con-

sidered to be the principles enunciated by this Court sitting

in banc in the Jefferson case, supra. In fact, there is an

obvious conflict between the opinion of the panel that rendered

the decision in these cases wherein they completely forbid the

consideration of a freedom of choice plan, and the other decisions

wherein freedom of choice may still be considered. It is submitted

that this difference cannot be justified by any reference to

the record in these cases, since, as previously submitted, it

is apparent that the panel in these cases had not had an oppor-

tunity to even examine the record.

It is submitted that the opinion of the panel of this

Court in Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181, decided August 20,

1968, which opinion has been cited by numerous panels of this

Court, involved only a motion to dismiss appeal from the docket

setting. The Adams decision, supra, was rendered without any

evidence whatsoever and without any record whatsoever setting

forth the facts as they pertain to any of the districts involved.

The motion to dismiss and remand was sustained. Nevertheless,

without a record and without the school districts involved hav-

ing an opportunity for a hearing on the merits, the panel of

this Court in Adams, supra, announced principles which are now

being referred to as the law in this Circuit, even though it was

interpreting the Jefferson in banc decision. We submit that the

principles enunciated in Adams are not in conformity with the

principles set forth by this Court sitting in banc in the Jefferson,

supra, decision, and this fact is demonstrated by the concurring

opinion of Justice Coleman in the in banc decision in Jefferson,

supra, in which he set forth what he understood the Court to be say-

ing in the majority opinion. There appears to be an obvious conflict

between what Justice Coleman thought this Court, sitting in banc,

was saying in the Jefferson case, supra, and what the panel in the

Adams decision, supra, considered to be the effect of that decision.

It is submitted that it is essential that this Court consider

these cases in banc in view of the lack of uniformity by the vari-

ous panels of this Court in interpreting and applying the decision

of this Court in its in banc decision in Jefferson, supra.

3. VARIOUS PANELS OFTHIS COURT HAVE NOT BEEN CONSISTENT

IN THEIR INTERPRETATIONS AND APPLICATION OF THE DECI-

SIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT IN GREEN V.

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF NEW KENT COUNTY, VIRGINIA,

S19U.8. 430, 20 1.Bd4.20 776, 88 5.Ct. 1639: “RANEY V.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF GOULD SCHOOL, DISTRICT, 391 0.5.

433,720 1.54.24 727, 33 5.01. 15697: and MONROE V., BOARD

OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF JACKSON, TENNESSEE,

3917 U.S. 450, 20" 1.4.24 733, 88 3.Ct. 1/00; AND THIS

COURT, SITTING IN BANC, SHOULD MAKE AN INTERPRETATION

AND APPLICATION OF THOSE DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES

SUPREME COURT THAT CAN BE UNIFORMLY APPLIED.

The United States Supreme Court in the Green case, supra,

Raney case, supra, and Monroe case, supra, clearly enunciated

the basic principles that the Constitution requires all districts

to be operated on a unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory basis

and that, in districts having a history of de jure segregation,

the school boards operating such school systems were required

to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school

system. In this context, the Supreme Court stated that steps

must be taken in which racial discrimination would be eliminated,

root and branch. These decisions, it is submitted, clearly es-

tablish that each school district of the nation must be operated

as a unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory school district and

that, in districts that have a history of de jure segregation,

the trustees of the school district have the affirmative duty

of "eradicating the last vestiges of the dual system'. The

confusion and misunderstanding now rampant in this Circuit grows

out of the interpretation and application of these basic concepts.

It is essential that this confusion be eliminated. Literally

hundreds of thousands of children are involved, as well as the

entire educational system. The interpretation and application

of these basic concepts, it is submitted, is probably the most

important question facing the courts of this nation today.

Involved in the answer to this question is whether the schools

will be operated, in their day to day operations, by a federal

department under the supervision and guidance of the federal

judiciary, or whether the officials of the districts can, through

qualified educators, operate the schools in conformity with the

concepts of the applicable provisions of the Constitution as

defined by the courts,

The two concepts are as follows: (A) a unitary, nonracial,

nondiscriminatory school system, and (B) the vestiges of a dual

system which must be removed by the trustees of the school dis-

tricts. We will briefly discuss these two concepts with the

thought in mind of at least demonstrating the necessity for a

clearcut, understandable judicial definition =-- a definition

that is based upon constitutional principles and not upon the

changing guidlines of a department of the executive branch of

our government dealing with the expenditure of funds.

A. What is a unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory

school system?

It is submitted that the answer to this question is not too

difficult. It is a school system which is open and free to all

pupils and in which race is not a factor. In fact, 1f it is

to be "nonracial'", then it is a contradiction on its face to

take action that is motivated by the race of the pupil. One

panel of the Fifth Circuit has given a definition in the

Broussard case, supra, as follows:

. “

"., . . it would appear that an 'integrated, unitary

school system' is provided where every school is

open to every child. It affords 'educational oppor-

tunities on equal terms to all.' That is the obli-

gation of the Board."

This Court in the Jefferson decision, supra, in banc,

stated as follows:

"The governmental objective of this conversion is

-- educational opportunities on equal terms to all."

It is submitted that this concept is clear, can be fol-

lowed and implemented by school trustees of all school dis-

tricts. The school districts throughout the nation, whether

they have a history of de jure, de facto, or no segregation

at all, must be operated on a unitary, nonracial basis. This

is easily understood and can be easily implemented by the

trustees that are acting in good faith. If the trustees are

not acting in good faith, such can be easily demonstrated

to and corrected by the district court and will not require

that the federal courts become involved in the day to day

operations of the schools in the school districts.

It is submitted that, if this Court in banc expressly

adopts the definition of a unitary, nonracial, nondiscriminatory

school system as succinctly set out in Broussard, supra, which,

with deference, it ought to do, then the only problem which

would remain would be to properly deal with the second concept.

B. What are the vestiges of the dual system which

must be eradicated by the trustees of the school districts?

Quite frankly, it would also appear that the answer to this

question should not be too difficult. It is submitted, however,

that some of the recent decisions of various panels of this

Court have made requirements of school districts that are not

in keeping with the obligation to remove the vestiges of the

dual system and have thereby created confusion and consternation

concerning the meaning of this obligation.

Our discussion here will be based upon the assumption that

we are correct in that the obligation of the trustees of the

school districts located in formerly de jure segregated states

is the affirmative duty to eradicate the last vestiges of the

dual system. If this be true, then these vestiges must be

identified and eradicated. It is not enough to operate a uni-

tary system at this time. These trustees must go further and

eradicate or eliminate any vestiges of the dual system.

Illustrative of the points we are attempting to make here

is the decision by a panel of this Court in the Adams case,

supra. The panel in the Adams case, supra, with no record

before it, and with no opportunity being offered counsel to

be heard, made a specific finding that an all-Negro school was

a vestige of the dual system and must be eradicated in all dis-

tricts in the Fifth Circuit. Since that time, the language in

the Adams decision, supra, has been quoted by several panels

of this Court. Insofar as we know, however, no case has ever

been presented to this Court which contained facts which would

support a finding that this is a vestige of a dual system.

A study of the history of litigation in this field indicates

that the "racial statistics'" approach as a measuring device

for determining whether the last vestiges of the dual system

have been removed originated with the office of Health, Educa-

tion and Welfare. That office promulgated guidelines which

contained statistical requirements to be used in determining

whether funds would be madeavailable to the various school

districts. It is submitted that this approach has been adopted

by some of the panels in this Circuit as a constitutional re-

quirement, when, as a matter of fact, the office of Health,

Education and Welfare has no authority to make constitutional

interpretations that are binding on the courts and that office

had no hearing or proof upon which to reach such a conclusion

in the first place. Certainly the decisions of this court

should be supported by proof.

If it be assumed that the Fifth Circuit has found, with-

out the benefit of any proof of any kind, that an all-Negro school

constitutes a vestige of the dual system, then we think it

important that this Court's attention be called to the case of

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, Tennessee, 406 F.2d

1183 (decided February 10, 1969). In the Goss case, supra,

the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit specifically found

and adjudicated that:

"The fact that there are in Knoxville some schools which

are attended exclusively or predominantly by Negroes

does not by itself establish that the defendant Board

of Education is violating the constitutional rights of

the school children of Knoxville. . . Neither does the

fact that the faculties of some of the schools are

exclusively Negro prove, by itself, violation of

Brown."

We do not know the extent of the proof, if any, on this

particular point that was in the record in the Goss case;

however, for purposes of presenting the point here being dis-

cussed we are assuming that there was no actual proof before

the court and that the Sixth Circuit, like the Fifth Circuit,

has made a finding based on taking judicial notice.

The situation is, therefore, that we have Courts of Appeal

for different circuits reaching opposite conclusions based on

judicial notice and without the benefit of any actual proof

in the record on which these conclusions could be based.

In these proceedings now before this Court, there is proof,

which was uncontradicted, that the existence of all-Negro schools

is not a vestige of the dual system. In addition, there has

been filed in the Fifth Circuit statistical information taken

from the official records of the office of Health, Education

and Welfare showing the racial composition of schools in the

one hundred largest school districts in this nation. Most of

these districts have never had a dual system. These statistics

show, and we submit this is conclusive, that all-white and all-

Negro schools exist in every school district where there is a

large percentage of both white and Negro pupils. These sta-

tistics show, beyond question, that all-white and all-Negro

schools do exist in school districts that have never had a dual

system. As a matter of fact, of the 12,497 schools in these

one hundred school districts, assuming that a school with

less than one percent of the minority race is an all-Negro

or all-white school, 6,137 are either all-white or all-Negro.

In other words, over forty-eight percent of the schools in

the one hundred largest school districts in this m tion are

either all-white or all-Negro. Most of these districts are

in areas that have never had a dual system. We submit, there-

fore, that for this Court to adjudicate that the existence

of an all-Negro or an all-white school is, in and of itself,

a vestige of the dual system is without support of any proof,

is incorrect, and is clearly erroneous.

It is submitted that such a finding by a panel of this

Court is not in keeping with the opinion of this Court in the

in banc Jefferson decision. The language of this Court in

Jefferson, sitting in banc, was that there was to be "no

Negro schools and no white schools -- just schools'. This

language of this Court in its in banc decision is in accord

with the obligation of the school trustees to operate a unitary

school system. The schools are not to be Negro schools nor are

they to be white schools. They are to be just schools. This

does not, however, mean that there must be both white and Negro

pupils in attendance at each and every school. Since the

existence of schools at which only Negroes attend, or the existence

of schools at which only whites attend is not, in and of itself,

a vestige of the dual system, then there is no constitutional

basis on which the courts may or can require their elimination

or eradication as being a vestige of the dual system.

For the benefit of this Court, we are attaching as Ex-

hibit "A" to this petition the report of Peat, Marwick,

Mitchell and Company, dated June 27, 1969, which, it is sub-

mitted, is self-explanatory.

In addition to the foregoing, there is in this record

testimony of emponts which demonstrates conclusively that (1)

all-Negro or all-white schools are not vestiges of the dual

system and (2) a definite or specific amount of integration of

the races in the schools is not an indication or even proof

that the schools are operated on a unitary basis with the

vestiges of the dual system eliminated or eradicated -- at

best, it is only peripherally relevant to the issues.

This evidence also stands uncontradicted and will be

discussed and presented in full, if this petition is granted

and this Court hears these cases in banc.

What we have stated concerning pupils isequally appli-

cable to faculties. The proof is that an all-Negro faculty

or an all-white faculty is not, in and by itself, a vestige

of the dual system and does not destroy the unitary nature

of the school system. |

Other illustrations could be given. It is submitted,

however, that the foregoing discussion points up the absolute

necessity of this Court, in banc, determining the issues

presented by these cases. We feel that this is particularly

true in view of the fact that some of the panels of this

Court, without the benefit of a record, have adjudicated

that all-Negro schools cannot exist, while other panels of

this Court have, upon review of the record, permitted all-

Negro schools to exist.

THE DECISION OF THIS PANEL IS CONTRARY TO THE CIVIL

RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 AND OTHER FEDERAL STATUTES ENACTED

UNDER AUTHORITY OF SECTION 5 OF THE FOURTEENTH AMEND-

MENT.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides '"The Con-

gress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legisla-

tion, the provisions of this article'. There is no need to cite

the long line of cases upholding this right, including many

specific congressional actions which preempt the particular

field involved.

U.S.C.A., Title 42, § 2000c(b), et seq.; Pub.L. 88-352,

Title 4, § 401(b), § 407(a), § 410, covers particularly the

desegregation of public schools and colleges. The decree here

is directly contrary to federal statute which provides:

"Section 401(bY: . . . but 'desegregation' shall not

mean the assignment of students to public schools in

order to overcome racial imbalance."

"Section 407(a): . . . provided that nothing herein

shall empower any official or court of the United

States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial

balance in any school by requiring the transportation

of pupils from one school to another or one school

district to another in order to achieve such racial

balance or otherwise enlarge the existing power of

the court to insure compliance with constitutional

standards."

"Section 410: Nothing in this title shall prohibit

classification and assignment for reasons other than

race, color, religion, or national origin."

The effect of the decree is to require assignment of stu-

dents against their will and the will of their parents in order

to overcome racial imbalance by direct assignment, racial

gerrymandering of zones or other devices. Not only does the

Civil Rights Act itself prohibit such action, but Congress has

continued to express the congressional intent. Its latest

expression is contained in the current appropriation act for

the Departments of Health, Education and Welfare and Labor

(Pub. L. 90-557; 82 Stat. 969), Section 409 of Title 4, relating

to elementary and secondary education, containing the following

clear prohibition:

"No part of the funds contained in this Act may be used

to force busing of students, abolishment of any school,

or to force any student attending any elementary or

secondary school to attend a particular school against

eee.

the choice of his or her parents or parent in order to

overcome racial imbalance." (Emphasis added).

It should be particularly noted that the federal statutes

are not limited to prohibition of actions to achieve "racial

balance” =-- they are much broader, covering any action for

the purpose of removing racial imbalance.

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that no

state shall make or enforce any law which shall deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws. It would be a presumptuous waste of time to reiterate

the arguments so forcefully advanced by the separate opinions

of Circuit Judges Gewin, Bell, Coleman and Godbold in Uni ted

States v. Jefferson County Bcard of Education, in banc, 380

F.2d 385 at p. 397, et seq. Suffice it to say that the heart

of the argument is embodied in Judge Gewin's opinion:

"It is not our function to condemn the children or

the school authorities because the free choices

actually made do not comport with our own notions

of what the choices should have been. When our

concepts as to proportions and percentages are im-

posed on school systems, notwithstanding free choices

actually made, we have destroyed freedom and liberty

by judicial fiat; and even worse, we have done so in

the very name of that liberty and freedom which we so

avidly claim to espouse and embrace."

With deference, neither this Court nor the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals in banc, nor the Supreme Court of the United

States has the slightest constitutional prerogative to require

these appellees to discharge their official duties in a manner

different from that vouchsafed by the Constitution to all the

citizens of this nation and as legislated by the Congress.

The Fourteenth Amendment, as "enforced" by "appropriate legis-

lation" by Congress, does not require integration of schools.

THIS IS A CASE OF FIRST IMPRESSION IN WHICH IT HAS

BEEN PROVED BY COMPETENT EVIDENCE ADMITTED BY THE

DISTRICT COURT AND BY THE COURT OF APPEALS THAT

FREEDOM OF CHOICE IS THE MOST PROMISING COURSE OF

ACTION TO BRING ABOUT MEANINGFUL AND LASTING DE-

SEGREGATION.

The courts have always recognized that constitutional

rights will not be sacrificed to violence, disorder or disagree=-

ment of any person, see particularly Cooper. The courts do

not act upon apprehensions or possibilities. In Monroe,

the Supreme Court stated:

"We are frankly told in the (school board's) brief

that without the transfer option it is apprehended

that white students will flee the school system

altogether." (Emphasis added).

The apprehension thus expressed was necessarily disregarded

by the Court.

Nevertheless, the courts consider the best evidence of

what may be reasonably expected to occur in the future. In

Green the duty was placed upon the district courts to weigh

the plan administered or propose

"in the light of the facts at hand and in the light of

any alternatives which may be shown to be as feasible

and more promising in their effectiveness.'" (Emphasis

added) .

In that case further reference was made to the possibility of

"more promising courses of action' which may be shown to be

open to the board.

In thece cases there was introduced evidence, prepared

and presented in conformity with all the authorities, which

proved that racial geographic zoning, pairing, assignment of

pupils on a racial basis or other massive immediate mixing of

the races would not result in meaningful desegregation. This

evidence, based upon an educational survey by disinterested

and qualified experts, demonstrated that freedom of choice,

implemented by the right of school authorities to use their

influence with parents to "make it work now', holds promise

of bringing about '"now'" (in the sense described in Carr, Green

and Raney) meaningful desegregation.

If a hearing is granted in banc, the school districts

will have an opportunity for this evidence to be considered

by this Court of Appeals.

RECALL OF THE MANDATE OR STAY OF FURTHER PROCEEDINGS

BY THE DISTRICT COURT 1S NECESSARY IF JUSTICE IS TO

BE DONE IN THESE TWENTY-FIVE CASES,

As the decree provided for the issuance of a mandate to

the district court immediately, without opportunity for the

filing of a petition for rehearing and such mandate has been

issued, it will be necessary that the mandate be recalled or

further proceedings by the district court be stayed in order

that justice may be done.

This application for stay is addressed only to the compulsory,

affirmative or mandatory features of the decree. The actions

ordered by the decree are irrevocable, and the injury to the

appellees, the parents and the pupils in all of the school

systems which are affected thereby will be irremedial. The

actions required will require expensive and substantial changes

in the operation and administration of the various school

systems. Irrevocable injury will be done to the teachers in

each of the school systems.

This petition is filed by authority of all counsel of

record for the defendant-appellees in all of the cases involved

and is signed in their behalf.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that it is essential that

the relief sought herein be granted. Not only are the school

districts included in this proceeding vitally affected --

but every district in this Circuit. In some of the larger

districts, the eradication of schools attended only by Negroes

or only by whites will be an impossibility =-- yet, this,

according..to a panel of this Court, is unconstitutional. Ob-

viously, this holding is, in effect, a holding that the Consti-

tution requires one thing in one school district and an entirely

different thing in another school district. If an attempt is

made to justify such inconsistency by referring to the factual

situation in the respective school districts, then the fact is

that the record in these cases was not even examined to attempt

to determine the facts.

If the courts are to require the trustees and boards of

education to take action that is not based upon constitutional

concepts, then the courts will have launched into the detailed

operations of the schools of this Circuit which will become only

more involved and to which there will be no end. The issues

here presented are vital and should receive the attention of

this full Court, sitting in banc. Until this has been done

and the decision made after full consideration, the action of

the district court in these cases should be stayed or the mandate

should be recalled. The actual continued existence of a

responsible public educational program may be involved in many

Of the districts in this Circuit.

UR

A, 4 0/2

Attorney General

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

hf 2 res

Gis (if CANNADA

700 Petroleum Building

Post Office Box 22567

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

: A

OHN M. PUTNAM

523 Bankers Trust Plaza Building

Post Office Box 2075

doch son, Mississippi 39205

Pe ld

2 Lisiteer Le. 2A

CHARLES CLARK >

1741 Deposit Guaranty Bank Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Asch (N=

WALTER R. BRIDGFORTH

Post Office Box 48

Yazoo City, Mississippi

3 Lu (7 LL 4 17 ey pd :

SATTERFIELD

Post Offite Box 466

" Yazoo City, Mississippi

FOR AND ON BEHALF OF:

M. M. ROBERTS

Post Office Box 870

Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401

®

HOWARD L. PATTERSON, JR.

Post Office Box 808

Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401

THOMAS H. WATKINS

Post Office Box 650

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

3... P. SPINRS :

DeKalb, Mississippi 39238

JOHN GORDON ROACH

Post Office Box 506

McComb, Mississippi 39648

R. BRENT FORMAN

Post Office Box 1377

Natchez, Mississippi 39120

RICHARD D. FOXWORTH

216 Newsom Building

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

PHILIP SINGLEY

203-04 Newsom Building

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

ROBERT GOZA

Canton, Mississippi 39046

W. S. CAIN

133 South Union Street

Canton, Mississippi 39046

JOE R. FANCHER

Post Office Box 245

Canton, Mississippi 39046

ROBERT S. REEVES

Post Office Box 998

McComb, Mississippi 39648

THAD LEGGETT, III

Post Office Box 307

Magnolia, Mississippi 39652

WILLIAM B. COMPTON

Post Office Box 845

Meridian, Mississippi 39301

ROBERT B. DFAN, JR.

Post Office Box 888

Meridian, Mississippi 39301

HERMAN ALFORD

424 Center Avenue

Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350

LAUREL G. WEIR :

Post Office Box 150

Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350

ERNEST L. BROWN

Macon, Mississippi 39341

HAROLD W, DAVIDSON

Carthage, Mississippi 39051

MAURICE DANTIN

Post Office Box 604

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

J. D. GORDON

Liberty, Mississippi 39645

WILLIAM D. ADAMS

Post Office Box 521

Collins, Mississippi 39428

JOHN K. KEYES

Collins, Mississippi 39428

CARY C, BASS, JR.

Post Office Box 626

Monticello, Mississippi 39654

HERMAN C. GLAZIER

506 Walnut Street

Rolling Fork, Mississippi 39159

J. WESLEY MILLER

401 Pine Street

Rolling Fork, Mississippi 39159

RICHARD T. WATSON

Woodville, Mississippi 39669

HENRY W. HOBBS, JR.

Post Office Box 356

Brookhaven, Mississippi 39601

CALVIN R. KING

106 Mulberry Street

Durant, Mississippi

G. MILTON CASE

114 West Center Street

Canton, Mississippi

THOMAS H, CAMPBELL, JR.

Post Office Box 35

Yazoo City, Mississippi

J. EF. SMITH

111 South Pearl Street

Carthage, Mississippi

ROBERT E. COVINGTON

Jeff Carter Building

Quitman, Mississippi

TALLY D. RIDDELL

Post Office Box 199

Quitman, Mississippi

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned, acting for and on behalf of all of the

counsel of record for the appellees in the above entitled

causes, does hereby CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of

the above and foregoing petition was this day mailed, via

United States mail, postage prepaid, to Honorable Robert E.

Hauberg, United States Attorney, Post Office Box 191, Jackson,

Mississippi 39205, and to Honorable David D. Gregory, Attorney,

Appeals Division, Department of Justice, Waslinston. D.C. 20530,

attorney of record for the United States of America; and to

Honorable Reuben V. Anderson, Melvyn R. Leventhal, 538% North

Farish Street, Jackson, Mississippi 39202, and Honorable Jack

Greenberg, 10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030, New York, New York

10019, attorneys of record for private plaintiffs.

,. 1969,

I Lo LZ oti afom

2

CERTIFIED, this the /4/= day of July

Y