Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 13, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1987. 103dc423-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6b06ef90-4438-4cac-8a76-20a0c213799a/monteilh-v-st-landry-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

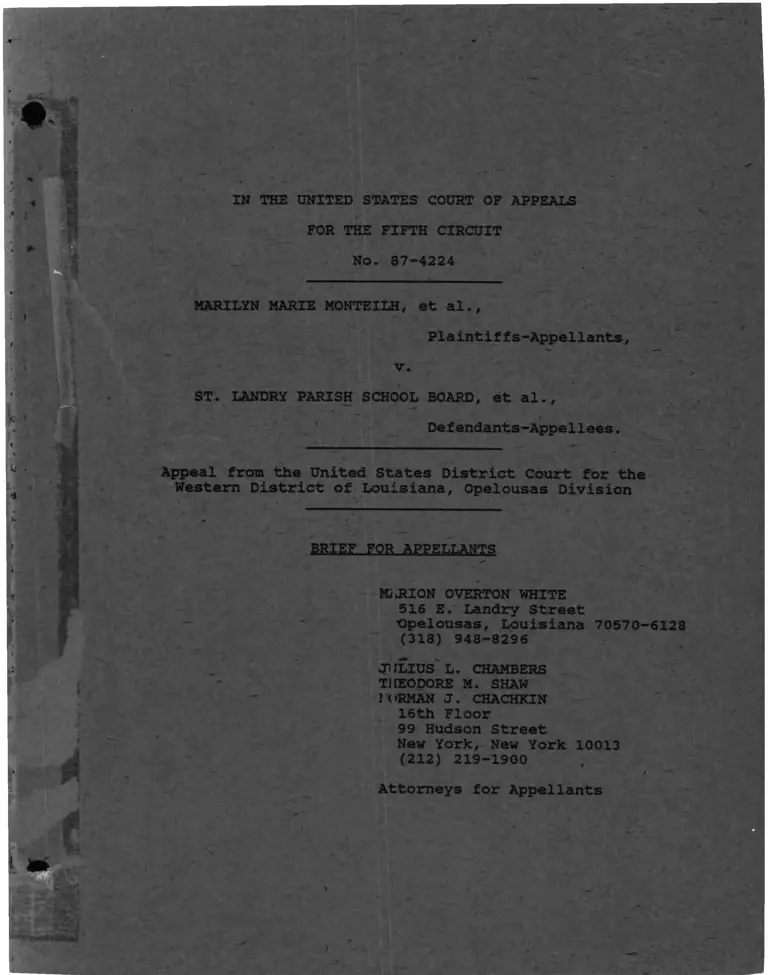

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-4224

MARILYN MARIE MONTEILH, et al.,

PIaint iffs-Appellants,

v.

ST. LANDRY PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

mammammmmmmm_______________- — mmm— mm

.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Louisiana, Opelousas Division

----- -----------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

MiiRION OVERTON WHITE

516 E. Landry Street

■Opelousas, Louisiana 70570-6128 (318) 948-8296

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

TJIEODORE M. SHAW

I (tRMAN J. CHACHKIN

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-4224

MARILYN MARIE MONTEILH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ST. LANDRY PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Louisiana, Opelousas Division

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following

listed persons and bodies have an interest in the outcome of this

case. These representations are made in order that the Judges of

this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

Marilyn Marie Monteilh, Daron Anthony Monteilh,

Martha Ann Monteilh and Geromaine Rita Monteilh, minors,

by their father and next friend Embrick Monteilh; Sandra

Ann Benson, Calvin Benson and Paul Benson, minors, by

their mother and next friend, Rose Benson; Mary Glenda

Malveau, Michael Malveau, Agnes Marie Malveau and Leo

Paul Malveau, minors, by their father and next friend,

Joseph Malveau; Elnora Malveaux, Jean Alice Malveau,

Robert Malveaux and Anthony Malveaux, minors, by their

father and next friend, George Malveaux; Richard James

Durrisseau, minor, by his father and next friend, Theo-

dule Durriseau, Jr.; Larry Alpough, Carl Alpough, Terry

Alpough, Fran Alpough, Wanda Alpough and Leon Alpough,

Jr., minors, by their father and next friend, Leon Al

pough; Hilda Mae Lewis, minor, by her father and next

friend, Clifton Lewis; Donald R. Semien and Annie Mae

Semien, minors, by their father and next friend, Adrien

Semien; Shirley Ann Semien, Wilfred Semien, Jr., Carbino

Blaze Semien, Tommy Semien, John Michael Semien, Linda

Faye Semien, Brenda Gail Semien and Blanche Semien, min

ors, by their father and next friend, Wilfred Semien.

The class of black children attending or entitled to

attend the public schools of St. Landry Parish, and their

parents and next friends

Rebecca R. Boudreaux, Veronica LeBlanc, Eula Tezeno,

McKinley Brown, Sr., Jake Paul, and Velma Savant, as

parents of children attending the public schools of St.

Landry Parish, and more particularly, Melville High School

The St. Landry Parish School Board

Joshua J. Pitre, Gus Breaux, Clifton Clause, Bryant

Goudeau, Patty Prather, Roger Young, John Miller, Gilbert

Austin, Jackie Beard, Jack Ortego, Jerry Domengeaux,

August L. Manual, and Ronald Carriere, as members of

the St. Landry Parish School Board

Henry DeMay, as Superintendent of Schools of St. Landry Parish

The United States of America

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Attorney for 'Plaintiffs-

Appellants

July 13, 1987

Request for Oral Argument

Appellants respectfully request that oral argument be sched

uled in this case, which involves issues of considerable importance

not only to the future operation of the public schools of St. Lan

dry Parish, Louisiana on a fully desegregated basis, but also is

sues central to the proper functioning of the district courts in

this Circuit in school desegregation lawsuits.

Under the plan approved below, the number of high schools

operated by St. Landry Parish would decrease from twelve to six,

including three newly constructed schools to replace existing fa

cilities, with consolidation and realignment of attendance zone

lines. The location of those new facilities and the configuration

of their attendance zones will determine the extent to which the

Parish's high schools are substantially desegregated for many years

to come. Oral argument will assist the Court in understanding,

the reasons for appellants' concern about the impact of the plan

adopted by the school board.

In addition, this appeal involves substantially irregular

litigation procedures sanctioned by the court below that call for

careful scrutiny by this Court and the exercise of its supervisory

jurisdiction. In recent years, in this and other school desegre

gation suits which have come before the district judge, modifica

tions to permanent injunctions have been made through informal

conferences in which plaintiffs' counsel was not invited to parti

cipate, and contested matters have been handled through hearings

called sua sponte by the court without appropriate motion papers

iii

having been filed by the school board. As a result, and as typi

fied by the instant appeal, essential and reliable information

about the impact of student assignment shifts upon racial enroll

ment patterns is not included in the record. Oral argument will

provide an opportunity for the members of this Court to explore

in depth the adequacy of the procedures followed in this litiga

tion.

Certificate of Interested Persons ......................... i

Request for Oral Argument....................................iii

Table of Authorities.......................................viii

Statement of Jurisdiction ................................. 1

Statement of Issues Presented for Review ................. 1

Statement of the C a s e ..................................... 3

1. Proceedings below ................................. 3

a. Background of the c a s e ....................... 3

b. Recent "proceedings" ......................... 4

2. Statement of F a c t s ............................... 8

a. Status of school desegregation in the Parish . 9

b. The original consolidation p l a n ........ . . n

c. The Melville-Grand Prairie closings .... 15

d. The final board plan and the Austin-

Pitre p l a n .............................. 16

e. Projected enrollments under the plans . . . . 19

Summary of Argument....................................... 22

ARGUMENT —

I The School Board Failed To Meet Its Burden Of

Justifying Its High School Construction And

Consolidation Plan As An Acceptable Means Of

Further Dismantling The Dual School System In

St. Landry P a r i s h ................................... 25

A. The School Board's Projections of Student

Enrollment and Racial Composition for the

Consolidated High Schools are Unrealistic

Because they are Based on an Invalid Assump

tion and Insufficient Information ............ 26

Table of Contents

Page

v

B. The School Board's Consolidation Plan will

Increase Segregation in the St. Landry

Parish High S c h o o l s ........................... 29

C. The School Board did not Seek to Eradicate

the Vestiges of the Dual System in Designing

its Consolidation Program ..................... 30

1. The school board did not consider

desegregation in the crucial early

stages of designing the consolidation

p l a n ................................... 31

2. The guidelines for drawing the new at

tendance zones limited the new plan to

maintaining the status q u o ............ 33

3. The school board failed to consider all

relevant conditions in the Parish related

to desegregation....................... 35

4. The school board failed to examine the

feasibility of the Austin-Pitre plan,

despite all indications that it would

result in more desegregation than the

final consolidation plan, and has ad

vanced no acceptable justification for

rejecting it ................. .. 37

D. The School Board's Retention of a School with

a Substantially Disproportionate Racial Com

position when Feasible Alternatives Exist

does not Satisfy its Remedial Obligations . . . 40

E. The School Board's Consolidation Plan Will

Result in Unequal Educational Opportunities

for Students Attending the Predominantly Black

North Consolidated High School................. 42

II The District Court's Repeated Ex Parte Communications

And Proceedings In This Litigation, His Refusal To

Reschedule The Hearings Below Despite Inadequate Notice

To Plaintiffs' Counsel And The Need For Time To Prepare

And To Conduct Discovery, And His Refusal To Require

That The School Board File Motion Papers To Secure

Modifications Of Injunctive Orders, All Constitute

Serious Abuses Of The Court's Discretion Which Should

Be Corrected In The Exercise Of This Court's Supervisory

Jurisdiction ......................................... 44

vi

44

A. The District Court's Management of TheseProceedings .............................

B. The Denial of Plaintiffs' Requested Continuances ......................................... 47

III Further School Construction By The St. Landry Parish

School Board Should Be Enjoined Pending Formulation

Of A High School Consolidation Plan Designed To

Accomplish Desegregation And An Appropriate Hearing

Thereon, Preceded By Adequate Notice to Plaintiffs . . 49

Conclusion................................................ 50

Appendices (maps)......................................... 3.a

vii

Table of Authorities

PageCases:

Brown v. Bd. of Educ. , 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .......... 42

Brown v. Neeb, 664 F.2d 541 (6th Cir. 1981).......... 45

Castaneda v. Pickard, 781 F.2d 456 (5th Cir. 1986) . . 35

Chavez v. Balesh, 704 F.2d 774 (5th Cir. 1983) . . . . 45

Copeland v. Lincoln Parish School Bd., 598 F.2d

977 (5th Cir. 1979) ............................. 31n, 33n

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, <02

U.S. 33 (1971)................................... 34n

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 483 F.2d

1017 (5th Cir. 1973).................... 33n

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd., 721

F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983) .............. 27, 35, 36, 38

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526

(1979)............................................ 9n

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 795 F.2d 1516

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 428 (1986) . 45

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . . 27, 35

Grochal v. Aeration Processes, Inc., 759 F.2d 801

(D.C. Cir. 1985)................................. 47n

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d 801

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969) . . 3

Hughes v. United States, 342 U.S. 353 (1942) ........ 45

In re Stone, 588 F.2d 1310 (10th Cir. 1978).......... 45

Lee v. Autauga County Bd. of Educ., 514 F.2d 1140 (5th

Cir. 1975)............................... 27, 31n, 34n, 49

Littlejohn v. Shell Oil Co., 483 F.2d 1140 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1116 (1973).............. 47n

Mayberry v. Maroney, 529 F.2d 332 (3d Cir. 1976) . . . 45

Monteilh v.St. Landry Parish School Bd., No. 71-2604

(5th Cir. Jan. 3, 1972) .............. .. 3n

viii

Page

Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Bd., No. 30315

(5th Cir. June 16, 1971)......................... 3n

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir.), cert.

denied, 426 U.S. 935 (1976) ..................... 42

Pitts v. Freeman, 755 F.2d 1423 (11th Cir. 1985) . . . 25n, 36

Rhodes v. Amarillo Hospital Dist., 654 F.2d 1148

(5th Cir. 1981) ................................. 47

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept., 679 F.2d 541 (6th Cir.

1983), rev'd on other grounds sub nom. Firefighters

Local Union No. 1784 v.Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984) 45

Swann v. Chari otte-Meckle.t>urg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971)................................... 3, 36, 38n, 48

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 444 U.S. 437 (1980) ..................... 36

Tasby v.Estes, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 423

U.S. 939 (1975) ............................. ; . 31n, 49

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish School Bd., 648 F.2d 959

(5th Cir. 1981) .............. .................. 31, 34n

United States v.Board of Public Instruction of Polk

County, 395 F.2d 66 (5th cir. 1968) . . . . 27, 30, 35, 49

United States v.DeSoto Parish School Bd., 574 F.2d 804(5th Cir. 1978) ................................. 34n

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish

School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) . 42

United States v. Lawrence County School Dist., 799 F.2d

1031 (5th Cir. 1986)................ 25n, 31, 34, 35, 40

United States v. South Park Ind. School Dist., 566 F.2d

1221 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 1007 (1978) 25n, 34n

United States v. Texas, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied sub nom. Edgar v. United States, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972) ............................... 42

ix

Page

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 532 F.2d 380 (5th

Cir.), vacated and remanded, 429 U.S. 990 (1976),

reaff'd, 564 F.2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977), on rehearing,

579 F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S.

915 (1979)....................................... 25n, 30

United States & Pittman v. Hattiesburg Municipal Separate

School Dist., 808 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1987) . . . . 40

Universal Oil Products Co. v. Root Refining Co., 328 U.S.

575 (1945)....................................... 45

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 702 F.2d 1221 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 914 (1983) . . . 38n, 39, 40

Wells Rushing, 755 F.2d 376 (5th Cir. 1985) . . . . 47

Statutes and Court Rules;

28 U.S.C. § 1291 . . . .

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1)

F.R. Civ. P. 60(b) . . .

1

1

34n, 45

Other Authorities:

7 J. Moore & J. Lucas, Moore's Federal Practice (2d ed.) 45

x

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-4224

MARILYN MARIE MONTEILH, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ST. LANDRY PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Louisiana, Opelousas Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of Jurisdiction

This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 be

cause the Order appealed from is a final order for purposes of

appeal and pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) because the order ap

pealed from grants a modification of the permanent injunctive re

lief previously awarded in this case.

Statement of Issues Presented for Review

As both district judges who considered this matter in 1986

recognized, the St. Landry Parish school system has never been

adjudicated, in accordance with the procedures that are now stand

ard in this Circuit, to have achieved "unitary status." Accordingly,

its plans for new construction and school abandonment must further

the complete disestablishment of the old dual school system.

In 1986, the St. Landry Parish School Board decided to build

three new high schools, to close a number of existing facilities,

and to consolidate attendance areas so as to reduce the number of

high schools from twelve to six. Plaintiffs challenged this plan

in the court below on the grounds that the sites selected for the

new facilities and the attendance zones drawn for them would result

in the operation of three heavily black and three heavily white

high schools.

The following issues are raised on this appeal:

1. Did the school board meet its burden of demon

strating, through competent and reliable evi

dence, that its school construction and zoning

plan would not cause resegregation at the high

school level and would further the process of

completely eliminating the vestiges of the dual system?

2. Did the district court err in failing to amend

its orders so as to require that the St. Landry

Parish school authorities strictly enforce attendance zone lines?

3. Did the district court deny plaintiffs an ade

quate opportunity to conduct discovery and to

prepare for a hearing before approving the

school board's construction and zoning plan? 4

4. Should the district court be required to con

duct judicial proceedings in this matter only

upon the filing of proper motion papers by

the school board, served upon counsel for plain

tiffs, rather than scheduling hearings sua

sponte on short notice based upon what the

court "reads in the newspaper" or otherwise

learns through extrajudicial processes?

2

Statement of the Case

1. Proceedings below

a. Background of the case

This lawsuit was originally filed in 1965 to end the dual

biracial system of public schooling in St. Landry Parish. It

progressed, in now familiar stages, through freedom of choice,

which was found ineffective in 1969 sub nom. Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Board. 417 F.2d 801 (5th 3ir.), cert, denied. 396

U.S. 904 (1969). On August 8, 1969, an JLEW-drafted plan (as modi

fied by the district court) , which inclu '.ed school pairings within

the City of Opelousas, was ordered to be implemented effective

with the 1969-70 school year.1 The following year, the district

court granted a school board motion to substitute a zoning plan

for the Opelousas schools.2 On plaintiffs' appeal, this Court

first vacated and remanded for reconsideration3 4 in light of Swann4

and then affirmed the district court's re-approval of that zoning

plan.5

1See district court's Decree, Appendix 1 to Appellees' Oppo

sition to Appellants' Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal [here

after cited as "Appellees' Opposition"] at pp. 73-77.

2See Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at pp. 44-63.

3Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Bd. . No. 30315 (5th

Cir. June 16, 1971), reprinted in Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at pp. 42-43.

4Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Bd, of Educ. . 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

5Monteilh v. St. Landrv Parish School Bd. . No. 71-2604 (5th

Cir. Jan. 3, 1972), reprinted in Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at pp. 32-33.

3

As modified, the original desegregation plan remained in ef

fect6 and there were no further proceedings concerning student

assignment in the suit until 1979, when the school board closed

Washington High School after a series of racial fights. Plaintiffs

thereupon filed a motion for further relief and for contempt

against the school board because of the closing. Following a con

ference among the court and counsel, a consent decree was entered

governing the terms ind conditions under which the school would

be reopened.7

b . Recent ’'proceedings. "

In recent years, the board has made substantial modifications

to the court-approved plan, but without following the usual course

of filing a motion, serving it upon counsel, and having an orderly

adjudication before the district court.

For example, in 1984 the board closed four school facilities

without giving notice to the court or to plaintiffs' counsel.8 In

1985, the superintendent of schools and the two-member "Bi-Racial

Committee"9 met with the district judge in the absence of counsel,

6Not all of the terms of Judge Scott's 1971 Order were carried

out by the school board, however. See infra notes 9, 10, 62 andpp. 10-11.

7See Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at pp. 30-31.

8See Appellees' Opposition, at pp. 6-7.

9As originally conceived by the district court in orders en

tered in 1970 and 1971, the bi-racial committee was to be composed

of twenty-two members (eleven of each race) who were parents of

children attending public schools and who were not employed by the

system nor related to employees of the system. Plaintiffs and

the school board, respectively, were to select the members of the

4

and agreed upon zone line changes between Grolee Elementary School

and Lawtell Elementary School, and between Washington High School

and Port Barre High School; in each instance, students affected

by the zone changes were given "freedom of choice" to attend either

the predominantly black or the predominantly white school (3 R.

42-43, 67-69, 102-04). The only entry in the case file resulting

f.vom the meeting was an Order concerning the Grolee-Lawtell zone

change,* 3 * * * * * * 10 which was served upon plaintiffs' counsel after it was

committee. See Docket Entries, pp. 16-17, 19, 23 [Orders of June

3 1970, June 10, 1970, March 29, 1971,and October 7, 1971].)

Paragraph 7 of Judge Scott's August 12, 1971 Order required the

school board to consult with the bi-racial committee concerning

the promulgation and maintenance of school zone lines, the selec

tion of sites for new schools, school transportation policies,

and student transfers (see Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at p. 40).

Some time between 1971 and 1985, the bi-racial committee be

came a two-member body. At the time of trial, the members were a

Mr. Champaign and a Mr. Jerome (a former school principal) (R.

Vul. 3 [8/12/86 Tr.] [hereafter cited as "3 R."] 26-28). Neither

the proposed construction sites nor the realignment of attendance

zones at the high school level were submitted to this "Bi-Racial

Committee." The Docket Entries fail to indicate that any motion

to modify the committee's composition or responsibilities was ever

filed; no notice of any such changes was ever received by plain

tiffs' counsel, no hearing was ever held, and no order was ever entered concerning these subjects.

10See Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at p. 29. Accord

ing to testimony at the TRO hearing, Judge Shaw had indicated that

he would inform plaintiffs' counsel about both modifications (3

R. 69) . Plaintiffs' counsel did not become aware of these zone

changes from changes in enrollment figures: although paragraph 6

of Judge Scott's 1971 decree (Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition,

at p. 40) requires the school board to submit semi-annual Hinds

County reports to the district court and the Bi-Racial Committee,

the Docket Entries reflect no filings and plaintiffs' counsel have not received a copy of any such report since 1972.

5

entered by the court — but no hearing was ever held on any of

these matters.11

Despite consideration by the St. Landry Parish School Board,

over a period of several years, of proposals for high school con

solidation and new construction, no motion to modify the outstand

ing injunctive decrees was ever filed by the school board once it

adopted a specific consolidation plan. During the summer of 1986,

plaintiffs' counsel learned that the board had approved interim

steps for 1986-87, with full implementation of the consolidation

plan to follow in the 1987-88 school year.12 on August 4, 1986,

plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further Relief and Temporary Re

straining Order, seeking to enjoin the- 1986-87 changes (R. 1-9).

On the following day, the district judge instructed the clerk to

place in the official court file correspondence from the school

superintendent about these changes that had been sent to the court

on June 10, 1986 (R. 11-23) —— along with the district judge's

June 16, 1986 response stating that the court had "no objections

^Similarly, on June 6, 1985 and June 26, 1985, the district

court entered orders modifying portions of Judge Scott's August

12, 1971 decree (see Docket Entries, p. 25). Again, counsel re

ceived copies of these orders after they were entered; no motion

requesting this relief was ever submitted by school authorities

nor was any hearing held. On January 9, 1986, the court (again,

apparently sua sponte) vacated a paragraph in the school system's

affirmative action plan, retroactive to January 1, 1986. The dock

et sheet indicates that the court expressly directed that no notice

of entry of this order should be given (Docket Entries, p. 25)

and no copy was received by plaintiffs' counsel.

12These interim steps included the closing of the Melville

High School building, transfer of its grades to the former middle

or junior high school, and reassignment of high school students

residing in the Krotz Springs community to Port Barre High School.

6

to the plan or the transfers approved by the Board" (R. 10).13

On the same date, August 5, 1986, the motion for temporary restrain

ing order was set for hearing before Judge Duhe in Lafayette on

August 12, 1986 (R. 24).14 Relief was denied following the hearing

(see 3 R. 26—33).

After the school board approved final zone lines for the con

solidation plan, it still submitted no formal motion for modifica

tion of the outstanding orders. Instead, on December 9 1986 the

district court filed a Minute Entry scheduling a hearirg for De

cember 29, 1986 "to consider approval of the new high sch'ol atten

dance zones approved by the St. Landry Parish School Board on

November 20, 1986" (R. 40). As Judge Shaw later sought to explain,

he had "read in the newspaper" that the school board was purchasing

sites for new schools under a consolidation plan and accordingly

decided to schedule the hearing (R. 116).

On December 2, 1986 Judge Shaw had made an ex parte request

of the school superintendent for documents concerning the consoli

dation plan, which were transmitted ex parte to the court on Decem

ber 4, 1986 (R. 41-42; see R. Vol. 2 [12/29/86 Tr. ] [hereafter

13Copies of these letters were never served upon plaintiffs7 counsel when they were sent.

14That hearing concerned only the 1986-87 changes, rather

than the entire consolidation and construction plan (which had

not yet received final approval by the school board, according to the testimony).

7

cited as "2 R."] 6-7). These documents were never served upon

plaintiffs' counsel.15

Requests for continuances to provide an opportunity for ade

quate preparation and discovery, and to secure the services of an

expert witness were denied (R. 70-79; see 2 R. 18 [request renewed

at start of hearing]).

At the conclusion of the December hearing the district court

approved the board's consolidation jv.an (R. 86). Plaintiffs sub

mitted a Motion for New Trial or, ir the alternative, to Alter or

Amend the court's ruling (R. 90-115), which was denied except that

the court announced that once the consolidation plan was fully

implemented, inter-district transfers would no longer be permitted

(R. 116-17) . It is from the denial of the Motion for New Trial

or to Alter or Amend that this appeal is prosecuted.16

2. Statement of Facts

This case concerns modifications of the attendance zones orig

inally set out in a 1971 court-ordered desegregation plan for St.

Landry Parish, resulting from the school board's adoption of a

high school consolidation plan.

15After receiving the December 9 Minute Entry setting the

hearing, plaintiffs' counsel was forced to pick up a copy of the

board's submission from the district court's chambers.

160n March 20, 1987 the district court extended the time with

in which a Notice of Appeal could be filed (R. 125), an extension

necessitated by a postal delivery mixup (see R. 118-23). There

after, on March 31, 1987, plaintiffs sought a Temporary Restraining

Order and Injunction Pending Appeal to delay the board's proposed

new high school construction (R. 128-42), relief which the district

court denied on April 13, 1987 (R. 154-60); similar relief was denied by this Court on April 29, 1987.

8

The Parish encompasses a geographic area of some 930 square

miles.17 In the 1985-86 school year, 17,480 students were enrolled

in forty-one public schools, including twelve high schools.18

(The number of students has been steadily decreasing since 1972-

73, when there were 21,572 students).19

a. Status of school desegregation in the Parish

Although Par: sh-wide enrollment is 53.3% black,20 there are

six "virtual one race" schools21 and another six schools have en

rollments of 80% :o 89% one race. At the high school level (grades

9 through 12),22 23 eleven schools were operated in 1986-87.22 Five

17Defendants' Exhibit 1, introduced at the hearing held Decem

ber 29, 1986, includes a map of the Parish.

18See Defendants' Exhibit 3, 12/29/86 hearing. The original

court decree provided for a thirteenth high school, Morrow, which

burned in 1984? its students were reassigned to Palmetto, see infra note 26.

19See Defendants' Exhibit 1, 12/29/86 hearing, at 4.

20Defendants' Exhibit 3, 12/29/86 hearing.

21"Virtual one race schools" refers to schools with student

enrollments of 90% or more one race. Davton Bd. of Educ. v. Brink-

man , 443 U.S. 526, 528 n.l (1979). The "virtual one race schools"

were Creswell Elementary, Krotz Springs Elementary, Morrow Elemen

tary, North Elementary, Plaisance High, and Southwest Elementary.

22There is no uniform grade structure in the Parish. Eunice

and Opelousas High Schools house only grades 10-12; Arnaudville,

Plaisance and Washington are K-12 schools; Port Barre is a 4-12

school; Leonville and Melville are 6-12 schools; Palmetto High is

a 7-12 school; and Lawtell and Sunset are 9-12 schools.

23The twelfth high school, Grand Prairie, was closed after

the 1985-86 school year and its students reassigned to Plaisance and Washington. See infra p. 15.

9

had student enrollments of 80% or more one race.24 Three of these

five high schools were "virtual one race schools."

The administrative staff requirements of the 1971 desegrega

tion order have never been fulfilled.25 At predominantly black

Plaisance High, Washington High, and Palmetto High, the admini

strative staffs are entirely black except for one white assistant

principal in each school (3 R. 34). Also, no predominantly white

high school has ever had a black principal or head coach (id. at

99-100). A black has never been considered for a principal's posi

tion at a majority-white high school (id. at 100).

Many pupils in the Parish attend schools outside their zone

of residence, including a substantial number who cross district

lines.26 The school system has no effective policy for enforcing

24Plaisance was 98% black; Palmetto was 91% black; Arnaudville

was 91% white; Washington was 83% black; Port Barre was 82% white.

(Percentages were calculated from enrollment figures in Attachment

VIII to Defendants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing (R. 59-69).)

25Paragraph 9 of the 1971 desegregation order states: "[T]he

Board is to specifically assign personnel in the positions of prin

cipal, assistant principal, guidance counselor, and head coach in

each school so that the race of these does not indicate that the

school was intended for Negro students or for white students."

Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at p. 40.

26For example, when Morrow High School burned down in 1984-

85, its students were assigned to the adjacent, but virtually all

black, Palmetto High. The majority of the white former Morrow

students suddenly developed allergies and produced doctors' notes

recommending that they attend an air-conditioned school. St. Lan

dry School Superintendent DeMay sent the Morrow students to the

two-member "Bi-Racial Committee," which approved their transfer to schools in Avoyelles Parish (3 R. 27) .

When Grand Prairie High school was closed at the end of the

1985-86 school year, and its students reassigned to Washington

High or Plaisance, none of the approximately 55 students so trans

ferred actually attended Plaisance; a maximum of thirteen went to

10

its zone lines. Primary responsibility is placed upon individual

school principals, but the amount of their salaries is dependent

in part upon student attendance at their schools (2 R. at 109) .

The school district's attendance officers investigate "zone jump

ing" only if a specific complaint is made (id. at 100, 109; 3 R.

68, 94). The system does not have a pupil locator map.

The "Bi-Racial Committee" also has approved intra-district

transfers which detract from integration of the schools (see, e.q.

2 R. 43); its recommendations and approvals are sent to the dis

trict court but no notice is provided to counsel (id. at 44).

b. The original consolidation plan

Consolidation of the St. Landry Parish high schools has been

under consideration for a number of years (2 R. 38) , but the school

board's present effort apparently began in late 1985 or early

1986.27 School superintendent DeMay admitted that further dismant

ling of the dual school system was not a consideration in designing

the consolidation plan (id. at 32).

The original proposal, upon which the final consolidated

school zone plan is based, was drawn up by the school system's

Washington (2 R. 103-09). The balance either went to public school

in Evangeline Parish, see, e.q.. Plaintiffs' Exhibit 1, 12/29/86

hearing, or to other St. Landry Parish high schools — for in

stance, by driving a family car to another school (2 R. at 108-09).

27According to Superintendent DeMay, the factors behind the

consolidation were the high cost of maintaining multi-floored

schools up to the Fire Marshal's standards, the cost of overstaf

fing caused by having many schools with small enrollments, and

the corresponding ability of the system to offer a broader cur

riculum at larger schools (3 R. 11-12).

11

two supervisors of child welfare and attendance, Mr. Boudreaux

and Mr. Auzenne (id. at 106). This proposal, including tentative

zone lines, was considered by a school district supervisory com

mittee headed by Mr. Dartez and, virtually unchanged by that com

mittee, was then presented to the school board for approval on

February 13, 1986 (id. at 106; Attachment I to Defendants' Exhibit

2, 12/29/86 hearing). It consolidated the twelve high schools of

the parish into six schools with rearranged attei.c.ance areas.28

In drafting the proposal, Auzenne and Boudreaux did not consider

desegregation but based the plan solely upon administrative con

venience (3 R. 116); the same factors (excluding desegregation)

influenced their review of alternative zoning and construction

proposals (id. at 124). Although Auzenne and Boudreaux calculated

projections for the racial composition of the new schools, the

implications of these results for the desegregation status of the

Parish schools were never discussed (id. at 116).

On December 8, 1985, over ten weeks before the consolidation

plan was even presented to the school board, the district published

a notice in the newspaper soliciting offers for the sale of land

upon which to build the North Consolidated High School.29 On Jan

28Auzenne and Boudreaux called for a North Consolidated

School, Northwest Consolidated High school, Southwest Consolidated

High School, Port Barre High, Opelousas High School, and Eunice

High School. Port Barre, Opelousas, and Eunice would be renovated,

and the other three schools would be newly constructed (id.).

Maps of the existing and proposed zones drawn by Auzenne and Bou

dreaux are Plaintiffs' Exhibits 1 and 2, 8/12/86 hearing, and are contained in the record, R. 38-39.

29See Exhibit 1 to Appellees' Opposition.

12

uary 23, 1986, the board approved the purchase of forty acres of

land at Lebeau which was recommended by the all-white Building,

Lands, and Sites Committee.30 (The Lebeau site was chosen because

it lies geographically midway between Morrow and Melville.31)

The land was actually purchased on February 26, 1986.32

On March 6, 1986, the school board approved the consolidation

plan and called for a public vote on approval of a bond issue to

finance both salary increases arc the construction of three new high

schools.33 (The map showing the tentative consolidated high school

attendance zone lines, which hac. been made available at the school

board meeting, was published in the newspaper;34 35 the Lebeau site

was marked on the map.) The vote was held on May 3 and the bond

issue was approved.3^

At some point after the March 6 board meeting, the zone lines

were changed in one significant respect. Under the original

(Auzenne-Boudreaux) proposal, the Lawtell zone was to be divided

30See Exhibit 3 to Appellees' Opposition; 3 R. 54.

312 R. 143.

32See Exhibit 2 to Appellees' Opposition.

33See Defendants' Exhibit 1, 8/12/86 hearing [Official Pro

ceedings of St. Landry Parish School Board, March 3, 1986].

343 R. 54. The map was Plaintiffs' Exhibit 2 at the August 12, 1986 hearing and is found at R. 39.

35R. 15-16. During the bond approval campaign, the predomi

nantly white Port Barre and Krotz Springs communities were promised

that the Port Barre lines would not be changed except to bring

Krotz Springs within the zone, as shown on the map published in

the newspaper. DeMay admitted that this promise was made to get

the communities to vote for the bond issue (2 R. 35-36).

13

roughly in half between Eunice High and Opelousas High. See R.

39. After the revision, however, the Eunice and Opelousas zones

remained virtually unchanged, while all of the former Lawtell zone

(except for the Lewisburg region) was assigned to the Northwest

Consolidated zone, which also included the former Plaisance zone,

the southern third of the former Washington High zone, and most

of the former Grand Prairie High zone.36

Also, tire Southeast consolidated zone, combining Araaudville,

Leonville, and Sunset, now included the Lewisburg region (previously

assigned to Lawtell High and originally transferred to Opelousas

High in the tentative proposal crafted by Auzenne and Boudreaux.)37

Mr. Austin, the black school board member whose district includes

Lewisburg, disagreed with the superintendent's estimates that the

area transferred from Opelousas to the Southeast consolidated high

school was racially mixed; he thought it was 99% white (2 R. 127-

28, 137-38, 140).

36The Lawtell change was made in response to a survey of par

ents' wishes conducted in March, 1986, which indicated that most

preferred that students then enrolled in Lawtell Elementary and

Lawtell High School attend the Northwest consolidated school (2

R. 15) . The change was decided upon before the August, 1986 hearing

on plaintiffs' motion for temporary restraining order, well before

the supervisory committee's full review of the attendance zones

described below (see Defendants' Exhibit 1, 8/12/86 hearing [projections at pp. 2-3]).

37Compare R. 39 (tentative zones prepared by Auzenne and Bou

dreaux) with R. 54 (Superintendent's revision to supervisory committee's recommended plan).

14

c. The Melville-Grand Prairie closings

On June 5, 1986, the board approved a decision made by Super

intendent DeMay to close predominantly white Melville and Grand

Prairie High Schools for the upcoming 1986-87 school year. Under

the Superintendent's proposal, the Melville students would move

to classrooms in Melville Junior High, except for the students

from the 99% white Krotz Springs area previously attending Mel

ville, who would be assigned to predominantly white Port Barre

High. The Grand Prairie students would be reassigned to predomin

antly black Washington High and Plaisance High (R. 13-15). While

student reassignments from the schools to be closed followed the

tentative attendance zone lines of the proposed consolidation plan,

the school board did not consider the impact of the Melville-Grand

Prairie closings on the receiving schools' racial compositions, and

no projections of the resulting 1986-87 enrollments, by race, were

made (3 R. 58).

After plaintiffs filed a motion for a TRO on August 4, 1986,

a hearing was held before Judge Duhe, following which the request

for emergency relief to bar the 1986-87 changes was denied.38

38Judge Duhe found that despite the "non-unitary status" of

the St. Landry Parish School System, the school board had failed

to consider or include desegregation objectives in the decision

making process by which the Melville-Grand Prairie closing plan

had been approved (R. 29-30). However, Judge Duhe approved the

plan because he found that (a) the motivations behind the school

closings and student transfers were financial rather than racial,

(b) although the school board did not consider racial issues in

approving the Melville-Grand Prairie plan, they had been a factor

considered in devising the overall consolidation plan, and (c) the

school board's projections indicated that no major change would

occur in enrollments by race in the schools affected by the Mel

ville-Grand Prairie closings; students from predominantly white

15

d. The final board plan and the Austin-Pitre plan

On August 28, 1986, a school board committee requested that

central office staff set the attendance zones and determine what

the racial composition of each high school would be under those

zones.39 Superintendent DeMay delegated these tasks to a super

visory committee under Mr. Dartez, and he directed the committee

to follow four guidelines in establishing the final zones: (1)

current attendance areas for elementary and junior high schools

should not be changed, (2) new attendance zones were needed only

for the three new consolidated high schools to be built, (3) new

zone lines should enable students to attend school as near as pos

sible to their residence, and (4) the racial makeup of the new

consolidated schools should reflect the racial makeup of those

former high schools which they would replace (2 R. 11-12; Defen

dants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, at p. 1).

On October 16, the Dartez committee's zones were presented

to the school board, which requested its Executive Committee to

look more closely at the lines, and, for the first time, asked

Grand Prairie would be transferred to predominantly black schools,

while the predominance of whites at Melville would be reduced (R.

31-33). These expectations did not materialize at Grand Prairie. See supra note 26.

39Exhibit 7 to school board's Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motions

for Temporary Restraining Order and Injunction Pending Appeal

and/or Motion for Filing of a Bond (submitted in district court),

at p. 3. This pleading, having been filed after the Notice of

Appeal, is not a part of the record on this appeal but has been

transmitted separately to this Court by the District Court Clerk.

It is referred to only for the purpose of providing a more complete

narrative description of the events. Exhibit 7 consists of ex

cerpts from school board minutes filed on behalf of the St. Landry Parish School Board.

16

that alternate plans be submitted40 On November 20, the Board

received the supervisory committee's plan with a minor revision

made by Superintendent DeMay,41 and an alternate plan drawn by Mr.

Austin and Mr. Pitre (two of the Board's three black members).42

The Austin-Pitre plan contemplated five high schools serving

the northeast, northwest, Opelousas, Eunice and southern areas of

the Parish. The northeast zone would combine the previous Palmetto

(including Morrow), Melville, and Port Barre areas. The northwest

school would combine the Plaisance, Grand Prairie, and Washington

zones along with portions of the Lawtell and Op.slousas High atten

dance areas. Opelousas High would serve a redrawn area including

parts of its former zone along with portions of the prior Leonville

and Lawtell attendance areas. Eunice High would serve its former

area along with a portion of the old Lawtell zone. Finally, the

southern consolidated school would combine Sunset, Arnaudville

and part of the Leonville zone. Under the Austin-Pitre proposal,

Eunice High and Opelousas High would be renovated and the other

40Id. at p. 4.

41The Superintendent's revision consisted of moving the north

ern boundary of the Northwest Consolidated School zone in the Wash

ington region to the intersection of La. Highway 10 and U.S. I-

49. Compare map of "Proposed Consolidation High School Lines,"

Plaintiffs' Exhibit 1, 8/12/86 hearing, R. 39 with overlay map,

Defendants' Exhibit 1, 12/29/86 hearing. Otherwise, the supervisory

committee's plan was virtually identical to the original Auzenne-

Boudreaux proposal that had been approved by the school board on

March 6, 1986, as subsequently modified with respect to the Lawtell area, supra pp. 13-14.

42See Attachment III to Defendants Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, R. 48-51.

17

three schools would be newly constructed. (See Court Exhibit 2,

12/29/86 hearing.)

The objectives of the Austin-Pitre plan were markedly dif

ferent from the superintendent's instructions to his staff: (1)

There would be five consolidated high schools, each housing a uni

form grade structure (9-12) ; (2) Student bodies at each school would

be equal in number or as close thereto as possible; (3) The schools

would each have the same nu:i>er of teachers; (4) The schools would

offer the same curriculum; ;5) The schools would have equal facil

ities; and (6) The three n« w schools would each cost the same to

construct. (2 R. 117-20; Court Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, at p.

1.)

As an appendix to this brief, three maps show the pre

consolidation high school zone lines for the Parish and the final

school board plan as well as the Austin-Pitre proposal. These

schematic drawings are approximate and were traced from Defendants'

Exhibit 1, 12/29/86 hearing [overlays] and Court Exhibit 2 from

the same hearing. But they indicate, when compared, the major

differences in approach between the board plan and the Austin-Pitre

alternative.43

43The board's plan, as revised by the superintendent from

the Auzenne-Boudreaux draft, draws zones generally in an east-west

direction with the effect of combining whiter areas together (as

in the zones for Port Barre and the South consolidated high schools)

and more heavily black areas together (as in the case of the North

west consolidated high school and the North consolidated high

school). On the other hand,the Austin-Pitre proposal has atten

dance areas aligned differently in a manner which includes black

and white residential areas in the same zones (as in the case of

the Northeast and Northwest consolidated high schools and the revised Opelousas zone).

18

At the school board meeting on November 20, 1986, after pres

entation of the Superintendent's revisions to the Auzenne-Boudreaux

proposal and of the Austin-Pitre plan, Austin made a motion to

hire a professional firm to conduct a demographic study of the

Parish before attempting to adopt final zone lines. A white board

member, Mrs. Prather, agreed, noting that the members knew little

about the actual population distribution. Five of the eleven school

board members present, including the three black members, felt

that an objective demographic study was necessary. However, over

their opposition, the six other members of the school board voted

to approve the Superintendent's revisions to the zones effective

for the 1987-88 school year without further inquiry. (Attachment

III to Defendants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, R. 49; see 2 R. 80.)

e. Projected enrollments under the plans

Projections of 1989-90 and 1991-92 high school student enroll

ment and racial composition, under the consolidation plan zone

lines adopted on November 20, 1986, were prepared by the supervisory

committee chaired by Mr. Dartez in late October, 1986 (2 R. 8-9,

29-30) .44 They consist simply of tallies of present student enroll

ment in the lower grades of the schools expected to feed the con

solidated high schools (id. at 5-10; 3 R. 116-17 [same method used

for projections made by Auzenne and Boudreaux under tentative zones

they drafted, discussed at August hearing on TRO motion]).

44The actual projections are Attachments VI and VII to Defendants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, R. 55-58.

19

The projections assume that 100% of the present lower-grade

students will advance from the feeder schools to the corresponding

high schools (2 R. 37; 3 R. 117) — in spite of Dartez' own ex

perience as an administrator at a predominantly black junior high

school in Opelousas, where only 30% to 35% of the white students

in the feeder school continued to the corresponding upper-grade

school (2 R. 75). Dartez also testified that there is a general

trend for students to drop out of high school when they reach the

age of sixteen (id. at 74) and that, from his experience, white

students in St. Landry Parish attending predominantly black schools

drop out or change schools in the eighth or ninth grade (id. at

75) .

Moreover, projections made by the Louisiana Department of

Education are also inconsistent with those of the school system's

supervisory committee. The state figures indicate that in two

years, 19.4% of the pupils in the St. Landry feeder grades will

not advance into the public high schools, and in four years, 25%

of the students in the feeder grades will not reach the public high

schools.45

45See Plaintiffs' Exhibit 3, 12/29/86 hearing [Item 2]. Com

paring the number of St. Landry Parish students in grades 7 through

10 in 1984-85 to the number projected in grades 9 through 12 in

1986-87 yields a 19.4% decline. Comparing the number of students

in grades 5 through 8 in 1984-85 to the number projected in grades

9 through 12 in 1988-89 yields a 25% decline.

The state's projections appear to be substantially accurate.

For example, they indicated that in 1986-87 St. Landry Parish would

have 4,439 students in grades 9-12. The actual total for grades

9-12 shown in Attachment VIII to Defendants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86

hearing, R. 59-69, excluding only students in grade 9 who attend

Eunice Junior High and Opelousas Junior High, is 3,768.

20

In drawing the attendance zones and calculating projections,

the supervisory committee did not take into account demographic

trends,46 drop-out rates, zone-jumping patterns47 or students leav

ing public schools for private schools. As indicated previously,

no demographic study was made. Not surprisingly, therefore, there

was some disagreement among school officials and board members

about the projections. For example: (1) Mr. Auzenne, who drew the

original consolidation plan along with Mr. Boudreaux, estimated

that the North consolidated high school would be about 80% bleick,

rather than 67% black as projected (3 R. 101). (2) Under the f: nal

plan the Lewisburg area would be transferred from predominantly

black Opelousas High to the heavily white South consolidated school;

the projections show 25 white and 20 black students from Lewisburg.

Board member Austin, who represents the electoral district inclu

ding Lewisburg and who has campaigned there, disagreed with the

superintendent's description of the area, and with the projections;

he said it is 99% white (see 2 R. 128, 137-38, 140).

Similarly, while the projections for Port Barre High, following

transfer of the virtually all-white Krotz Springs area from Mel

ville, were for no change in racial composition (see 3 R. 19) ,

46A critical demographic factor addressed by the Austin-Pitre

plan is the sparse population in the north and northwestern areas

of St. Landry Parish. Mr. Dartez explained that the population

of the Parish is moving southward and decreasing generally and

Board member Austin stated that farmers are leaving the northern

parts of the Parish (2 R. 73, 120, 149).

47See supra pp. 10-11.

21

in 1986-87 the high school grades increased from 79% white to 82%

white (see 3 R. 19, R. 69).

Austin and Pitre requested that the school system's central

office prepare projected enrollments and racial breakdowns for

their alternative plan. According to the incomplete figures fur

nished to them, each of the high schools would enroll approximately

700 students, except for Opelousas Senior High which would have

about 1,000 students (see Court Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing). A

complete racial breakdown was provided only for the Palmetto-Morrow-

Melville-Port Barre-Krotz Springs school, vhich would be 58% white

and 42% black (see Court Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, at p. 2).48

Summary of Argument

I

St. Landry Parish has not achieved unitary status, and the

school board therefore had the burden of showing that its proposed

high school construction and consolidation plan would further the

complete dismantling of the dual system. The court below erred

48A variety of cost savings were built into the Austin-Pitre

plan. Port Barre High would be converted to a kindergarten through

eighth-grade school. Port Barre Elementary, presently a kinder

garten through third-grade school, could then be closed, saving

$43 6,095. The cost of renovating Port Barre High up to high school

standards would also be saved (2 R. 118-19). Although the mileage

for transporting students from Morrow would increase, only one

bus would be needed (id. at 142). Moreover, the mileage would

decrease for transporting a far greater number of students from

Melville and Krotz Springs (id. at 120). Because the three new

high schools would be the same size, the same architectural plan

could be used for all three (id. at 129). Operating five schools

instead of six would also yield savings from not having to duplicate

utilities and staff salaries (id. at 132) . Austin estimated his

plan would save close to $1 million (id. at 143).

22

in concluding that the board had met its burden and should not

have approved the plan.

A. The board relied entirely upon a set of "projections"

purporting to show enrollments by race anticipated under the plan,

but the method of calculating the projections was fatally flawed

because it ignored demographic trends, widespread zone jumping

under the present plan (which the district court refused to correct)

and a high drop-out rat<>. among white students assigned to predomin

antly black schools.

B. The currei t enrollments of schools grouped together

for purposes of consoliJation indicate that the plan will increase

high school segregation in the Parish.

C. Promoting desegregation was not a factor in the design

of the consolidation plan, the selection of the site for a new

high school, or the configuration of attendance zones under the

plan; rather, the plan was drawn to conform to a guideline that

required maintaining existing attendance patterns to the greatest

extent possible. Accordingly, the drafters of the plan failed to

consider either important demographic factors or the availability

of more desegregative alternatives, such as a consolidation plan

proposed by two black members of the school board.

D. The board advanced no acceptable justification for

the maintenance of Port Barre High as a disproportionately white

school.

23

E. The plan will create a small, heavily black, unequal

and inferior high school in the northern part of the Parish and

thus deny equal educational opportunity to its students.

II

The district court abused its discretion in permitting ex

parte communications to the court from the school superintendent,

in conducting "informal hearings" with school officials without

not .ce to or participation of plaintiffs' counsel, and in scheduling

headings sua sponte on the basis of its extrajudicial observations,

rather than following submission of appropriate motion papers by

the school board. The court similarly abused its discretion by

setting the hearing below on short notice, without allowing adequate

opportunity for discovery, preparation, or retention of expert

witnesses on behalf of the plaintiffs, and in denying requests

for continuance of the hearing on those grounds. These matters

require correction by this Court in the exercise of its supervisory

jurisdiction.

Ill

Further school construction in St. Landry Parish should be

enjoined on remand pending formulation and approval, following a

hearing with adequate notice and opportunity for preparation by

plaintiffs' counsel, of a consolidation plan designed to accomplish

desegregation.

24

ARGUMENT

I

The School Board Failed To Meet

Its Burden Of Justifying Its High

School Construction And Consolidation

Plan As An Acceptable Means Of Further

Dismantling The Dual School System In

____________ St. Landry Parish___________

Because St. Landry Parish is not a unitary school system,49

it has an "affirmative duty to seek means to eradicate the vestiges

of the dual system,"50 and must, at a minimum, make a reasonably

sophisticated and realistic examination of the impact of its pupil

assignment policies and school construction plans on desegregation.

The district failed to demonstrate that it had met its affirmative

duty, and the court below erred in approving the high school con

solidation and construction plan.

49Both Judge Duhe and Judge Shaw concluded that St. Landry

Parish remains a non-unitary system (R. 29; 2 R. 156). Although

Judge Scott labelled the Parish "unitary" in his 1972 desegregation

order, the district court retained jurisdiction for a minimum of

three years (see Appendix 1 to Appellees' Opposition, at p. 41) .

Retention of jurisdiction is standard practice in this Circuit

and indicates a continuing non-unitary status. United States v.

Lawrence County School Dist.. 799 F.2d 1031, 1037 (5th Cir. 1986);

United States v. South Park Independent School Dist.. 566 F.2d

1221, 1225 (5th Cir.), cert, denied. 439 U.S. 1007 (1978). Also,

a hearing, with previous notice given to the parties, is required

before a school system can be declared unitary. United States v.

Lawrence County School Dist.. 799 F.2d at 1037-38 and cases cited;

see Pitts v. Freeman. 755 F.2d 1423 (11th Cir. 1985).

50United States v. Texas Education Aaencv. 532 F.2d 380, 398

(5th Cir.), vacated and remanded. 429 U.S. 990 (1976), reaff'd.

364 F.2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977), on rehearing. 579 F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 443 U.S. 915 (1979).

25

A. The School Board's Projections of Student Enrollment

and Racial Composition for the Consolidated High

Schools are Unrealistic Because they are Based on an

Invalid Assumption and Insufficient Information_____

The school board claims, based upon its enrollment projections,

that its consolidation plan will increase integration in the public

schools of St. Landry Parish. But the assumption underlying the

projections is invalid, and the information on which the projec

tions are based is grossly insufficient. Therefore, the projec

tions do not realistically portray the future student enrollment

and racial composition of the consolidated high schools, and the

district court erred in relying upon them as a basis for approving

the plan.

The supervisory committee's projections were based solely on

present enrollment in the lower grades that will feed the consoli

dated high schools. Their validity thus rests upon the assumption

that present lower-grade students will attend the Parish's high

schools. The only rationale for this approach, according to Super

intendent DeMay, was that "factual information is better than pull

ing numbers out of your head anytime" (2 R. 21). Judge Shaw echoed

this rationale in his oral opinion, stating: "We only know where

we are, we don't know where we may be" fid, at 155) . Such reasoning

negates the basic premise of projections, which is that by gathering

all relevant data and examining demonstrable trends, one.can make

an informed prediction about the future.

In examining the effect of its construction plans upon desegre

gation, a school board is obligated to consider demographic pat

terns and changes, student residence, the availability of private

26

academies, etc. See Green v. County School Board. 391 U.S. 430,

439 (1968); Davis v. East Baton Rouae Parish School Board. 721

F.2d 1425, 1435 (5th Cir. 1983); Lee v. Autauga Countv Board of

Education, 514 F.2d 646, 648 (5th Cir. 1975); United States v.

Board of Public Instruction of Polk Countv. 395 F.2d 66, 70 (5th

Cir. 1968). However, both the supervisory committee and the St.

Landry Parish School Board looked only at present feeder school

enrollments. No attempt was made to tcke account of other cogniz

able factors that will certainly afcect the student enrollment

and racial composition of the consolidated high schools, including:

(a) the shift of population out of the northern area of the Par

ish,51 (b) substantial zone jumping by white high school students,52

and (c) the significant drop-out rate between the lower grades and

high school.53

The significance of the drop-out rate and of white student

zone-jumping was dramatically evidenced by the testimony of Mr.

51See supra note 46.

52See supra pp. 10-11.

5 3 The Louisiana Department of Education's projections for

student enrollment in the St. Landry Parish public school system

show that a substantial percentage of feeder school students (19.4%

oyer two years and 25% over four years) do not advance into the

higher grades. The school board did not consider this trend in

making its projections. Therefore, the board's projections for general student enrollment are inflated.

Moreover, the school board should have compared the black

drop-out rate to the white drop-out rate. Because whites assigned

to attend heavily black secondary schools in St. Landry Parish

often do not appear, see text infra, it is likely that the drop

out rate in predominantly black schools is higher for whites than

for blacks, and that the proposed North and Northwest consolidated

schools will be much more heavily black than projected.

27

Dartez, who chaired the supervisory committee responsible for cal

culating the board's projections. In his experience, white stu

dents assigned to heavily black schools drop out or change schools

in the eighth or ninth grade: only 30% to 35% of the white students

in feeder schools went on to the junior high school where he worked

(2 R. 75). This suggests, particularly in light of the Parish's

loose or nonexistent procedures for enforcing its zone lines and

the ease with which students obtain approval for transfers from the

"Bi-Racial Committee," that the number of white students who will

attend the predomir -mtly black consolidated schools is substantially

over-estimated in the supervisory committee's projections.

If there were to be any hope at all for realization of the

enrollment projections prepared on behalf of the school board, it

would rest upon an effective mechanism to insure that students

attend the school serving their zone of residence. In their Motion

to Alter or Amend, plaintiffs sought this relief from the district

court and submitted two examples of federal court decrees in other

cases requiring it (see R. 96-114). However, the district court

ignored the request, except to enjoin students from attending school

outside the Parish when consolidation is implemented. This, of

course, will do nothing to prevent white students who in the past

have preferred to go out of the Parish rather than attend predomin

antly black schools, from zone jumping within the Parish in the

future. Indeed, the likelihood that this will occur is great,

because of the substantial disparity in racial composition among

the consolidated high schools which the school board's own figures

reveal.

B. The School Board's Consolidation Plan will Increase

Segregation in the St. Landrv Parish High Schools

The consolidation plan approved by the school board consti

tutes a major step backwards in the process of desegregation be

cause it will eliminate all of the currently non-racially identi

fiable high schools in the Parish, and then create three racially

identifiable white schools and three racially identifiable black

schools. A close look at the map of the original high school at

tendance zones makes this conclusion evident. See infra p. la.

In a school district like St. Landry Parish with so many sub

stantially white and substantially black schools, any forthright

attempt at using consolidation to further eradicate the dual system

would combine substantially one-race schools of opposite racial

composition. However, the school board's plan does the reverse:

— Substantially white Port Barre High is combined with the

Krotz Springs area, which is 99% white, resulting in a readily identifiable white school.

— The Southeast consolidated school combines Arnaudville

High, Leonville High, and Sunset High (a virtually all-white school,

a predominantly white school, and a well-integrated school), resulting in a larger, identifiably white school.54

54The Southeast consolidated high school will also include the

Lewisburg area, formerly a part of the Lawtell zone. As noted

above, the Superintendent and Board member Austin disagree about

the racial composition of the area, which Austin believes to be

99% white (see supra p. 21) . Lewisburg is closer to the center

of the Northwest zone than to the center of the Southeast zone,

and the school board offered no explanation why this one portion

was separated from the rest of the Lawtell zone in its final consolidation plan.

29

— The North consolidated high school combines Palmetto High,

part of Washington High, and Melville High (two heavily black

schools and one previously well-integrated school), resulting in

an identifiably black school, and one which is likely to be much

more heavily black than officially projected. See. e.g.. 3 R.

101 [Auzenne: school will be 80% black]; id. at 27 [white students

reassigned to Palmetto from Morrow did not attend school but trans

ferred to Avoyelles Parish schools because of •'allergies"]).

— The Northwest consolidated school combines Plaisance High,

part of Washington High, Grand Prairie High, and Lawtell High (a

virtually all-black school, a predominantly black school, a small,

predominantly white school, and an integrated school), resulting in an identifiably black facility.

In light of the established practice for white students in

St. Landry Parish to avoid attending heavily black high schools,

the board's consolidation plan will further accentuate the dif

ferentiation of public education in the Parish along racial lines

— exactly the opposite of the objectives to which this litigation

has been addressed for more than twenty years.

C. The School Board did not Seek to Eradicate the Vestiges

of the Dual System in Designing its Consolidation Program

Because school construction has such a profound effect on

racial composition, a school board which has operated a dual school

system has "an affirmative duty overriding all other considerations

with respect to the locating of new schools, except where inconsis

tent with 'proper operation of the school system as a whole,' to

seek means to eradicate the vestiges of the dual system." United

States v. Texas Education Agency. 532 F.2d at 398, guoting United

States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk Countv [emphasis in

30

original].55 "The failure sufficiently to satisfy this obliga

tion continues the constitutional violation." United States v.

Lawrence County School District. 799 F.2d at 1044, quoting Tavlor

v. Ouachita Parish School Board. 648 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1981) [em

phasis omitted]. Further, a school board does not satisfy its

constitutional obligation by choosing a school construction plan

that merely maintains the status quo.56 57 It must actively seek

to promote complete dismantling of the dual system.5’

1. The school board did not consider

desegregation in the crucial early

stages of designing the consolidation plan__________________________________

Auzenne and Boudreaux did not consider how their plan would

affect school desegregation until after they had configured high

school zones based solely on geography. Similarly, alternative

55See United States v. Lawrence County School District: Pitts

v. Freeman; Tavlor v. Ouachita Parish School Board. 648 F.2d 959

(5th Cir. 1981) ; Copeland v. Lincoln Parish School Board. 598 F.2d

977 (1979); Tasbv v. Estes. 517 F.2d 92, 105 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 423 U.S. 939 (1975); Lee v. Autauga County Board of Education.

56As we have suggested in the preceding section, there is in

fact every reason to believe that the school board's consolidation

plan will substantially decrease the level of desegregation in the high schools.

57For example, in Lee v. Autauga Countv. a school board oper

ating under a 1970 desegregation order had considered how its plans

to construct a new school would affect the existing attendance

zone in which it was to be located. This Court ordered the board

to examine alternatives that might alleviate continuing segregation

within the school system as a whole. 514 F.2d at 648. In Copeland

3L_Lincoln Parish School Board, in comparison, a school construc

tion plan was approved because the new schools would have racial

compositions closely approximating that of the school system as a

whole, and achievement of desegregation was a critical element in

the school system's planning and site selection. 598 F.2d at 981.

31

plans were compared and eliminated by them solely on the basis of

administrative convenience. Although projections of student en

rollment and racial composition were made, they were not affirma

tively considered in fashioning the plan but were looked at only

after the plan was completed; no revisions to the plan were made

in light of the projections.

The approach used by Auzenne and Boudreaux is significant in

that their plan defined the essertial design of the attendance

zones. This was the only plan presented to the school board for

approval in February, 1986, and '.t served as the basis for the

final attendance zones drawn in the fall of 1986. Moreover, the

Lebeau site for the North consolidated high school was chosen even

before any consolidation plan was approved by the school board;

in selecting the site, the board d;.d not consider how desegregation

might be advanced but simply chose a location approximately halfway

geographically between Morrow and Melville without regard to popu

lation distribution in the Parish 'see 2 R. 143-44). This decision

limited the options available to the board for designing attendance

zones.58 A location more central to the entire Morrow, Melville,

58Placing the North consolidated high school in Lebeau effec

tively limits the school's attendance zone to the Morrow, Palmetto

and Melville regions. At the same time, it creates the need for

a separate school to serve Port Barre and Krotz Springs (3 R. 25) .

The result is a small, predominantly (under the official projec

tions) or overwhelmingly (plaintiffs' concern) black school with

few students in each grade in the north, and a small, heavily white

school with few students in each grade in Port Barre. (See Attach

ment VII to Defendants' Exhibit 2, 12/29/86 hearing, R. 55-58 [pro-

jections] ; Attachment VIII to id. , R. 66 [small numbers of students

in each grade in 1986—87 at Port Barre High, already joined with

Krotz Springs area in that school year].) The small size of the

schools will limit their funding, which is allocated on a per-

32

Palmetto, Port Barre and Krotz Springs areas would have avoided

the creation of a disproportionately white school at Port Barre.

See 2 R. 68-69 [Dartez agrees that school serving entire area would

be more desegregated than Lebeau site].

2. The guidelines for drawing the new

attendance zones limited the new plan

to maintaining the status cruo________

In the fall of 1986, when the supervisory committee was asked

to draw a fins.l attendance zone plan, Superintendent DeMay gave

the committee 'our guidelines on which to base the plan.59 These

guidelines in no way directed the committee "to seek means to erad

icate the vestiges of the dual system."60 In fact, the Superinten

dent's guidelines called for as little change as possible and re

stricted the plan to maintaining the status cruo? when the committee

finished its work, the attendance zones approved by the St. Landry

student basis and may limit the breadth of their curricula (2 R.

20, 89-91, 131; see also Attachment III to Defendants' Exhibit 2,

12/29/86 hearing, R. 49 [official proceedings of November 20, 1986

meeting at which Superintendent DeMay stated that smaller schools

may have fewer electives]). The Austin-Pitre plan envisions one

large school in an area central to the Morrow, Palmetto, Melville, Port Barre and Krotz Springs regions (2 R. 120).

59The guidelines are set out supra at p. 16.

60Compare the Superintendent's guidelines to the standard set out in Davis v. Bd. of School Commissioners of Mobile County. 483

F.2d 1017, 1019 (5th Cir. 1973): "Site must be as centrally located

as possible to maximize desegregation." In Copeland v. Lincoln

Parish School Bd.. a guideline stipulating "maintenance of racial

balance" was approved, but no school in that parish was more than

56% black, 598 F.2d at 981, and the two new schools approved in

Copeland were both projected to have student enrollments within

5% of the racial ratio of the school system as a whole.

33

Parish School Board for the consolidated high schools followed

the existing zone lines as closely as was feasible.