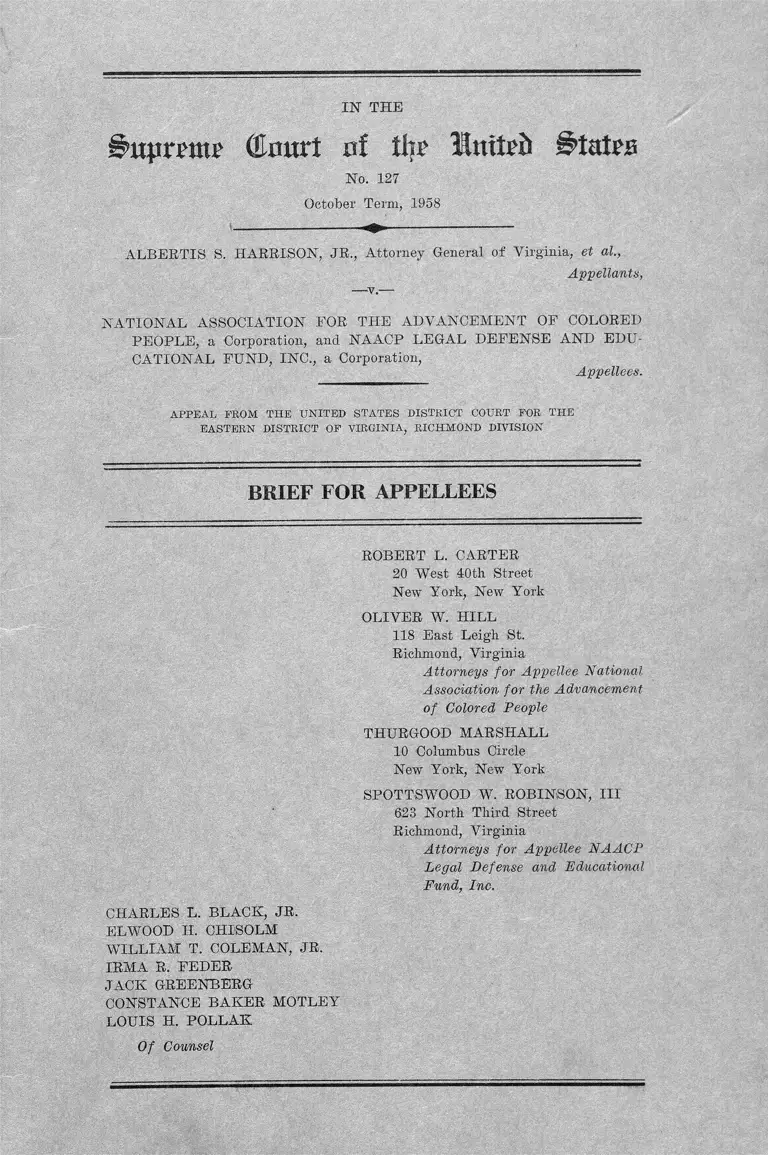

Harrison v. NAACP Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 13, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. NAACP Brief for Appellees, 1959. ae426689-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6b45e4d2-328d-445d-8289-5663cf4fd1b4/harrison-v-naacp-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

lihtprme (Emtrt of tin Mntfofi States

No. 127

October Term, 1958

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., Attorney General of Virginia, et al.,

Appellants,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE, a Corporation, and NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDU

CATIONAL FUND, INC., a Corporation,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, RICHMOND DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

ROBERT L. CARTER

20 West 40th Street

New York, New York

OLIVER W. HILL

118 East Leigh St.

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellee National

Association for the Advancement

of Colored People

THURGOOD MARSHALL

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, I I I

623 North Third Street

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellee NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.

IRMA R. FEDER

JACK GREENBERG

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

LOUIS H. POLLAK

O f Counsel

I N D E X

Table of Cases..... ...................................................... - iii

Other Authorities ............................................. vii

Statement of the Case................................................ 1-14

1. Proceedings Below......................................... 1-2

2. Statutes Involved ........................................ 2-4

3. Statement of Facts ....................................... 4-14

“The Association” ........................................ 4-10

“The Fund” ......... 10-14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....... 14-16

Argument .................................................................. 17-52

I. These Virginia statutes not only curtail law

ful activities of two membership corpora

tions and of their members, contributors,

and attorneys, but also strike at basic civil

rights and liberties guaranteed by the Con

stitution ................................. - 17-36

A. Compulsory Disclosure of Organizational

Affiliates Where Economic Reprisals and

Other Manifestations of Public Hostility

Will Ensue Violates the Fourteenth

Amendment ..... 18-22

B. Denial of Access to the Courts............... 22-23

C. Deprivation of Liberty .......................... 23-25

D. Virginia Has Shown No Justification for

Chapter 35 ....... — 25-33

E. Denial of Equal Protection..................... 33-36

PAGE

PAGE

II. There were no legally sufficient reasons to

deny appellees injunctive relief or postpone

action in deference to the state courts........ 36-52

A. The District Court Properly Enjoined

Enforcement of the Statutes Without

Their Previous Consideration by the

State Courts .................................... ..... . 36-48

B. The Cases at Bar Present Circumstances

Which Warranted Enjoining the Crim

inal Statutes in Suit ................ ..... .... . 48-52

C o n c lu sio n 52-53

I l l

T able o r C ases

page

Adams v. Tanner, 244 U. S. 590 ................ ................... 50

Air-Way Electric Appliance Corp. v. Day, 266 U. S. 71 35

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern By.,

341 U. S. 341 ............ ............................... ..........37,38,39

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 ............................ 42, 47

Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112 F.

2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940) ....... ................ ...................... 30

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

582 ................. .............. ......................................... -.38, 47

Barbier v. Connally, 113 U. S. 27 .............................. . 22

Bartels v. Iowa, 262 U. S. 404 .................. ................... 24

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. 2d 391 (4th Cir. 1949) .......... 45

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .................................... 24

Brannon v. Stark, 185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir. 1950), affd.

342 U. S. 451 ............ ........................................... 29, 30,31

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 ....... .............. .............. .........................................22, 45

Brush v. Carbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252

(1907) .................. - ..............................................27,30,31

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. I). S. C. 1957),

vacated as moot 354 U. S. 933 .......... .............. ....... 43

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60 ............................ 15, 21

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315............................ 37

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 IT. S. 296 ........................ - 30

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 IT. S. 238 ..................... 50

Chicago v. Atchison, T. & S. F. B. Company, 357 U. S.

77 .....................................................................16,42,43,46

Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, 316 IT. S. 168................. 42

Concordia Fire Ins. Co. v. Illinois, 292 IT. S. 535 ...... 35

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 ...... ................. -..........15, 21

Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 36 ............................ ....... 22

IV

Davies v. Stowell, 77 Wis. 334, 47 N. W. 370 .............. 31

Davis v. Sclmell, 81 F. Sapp. 872 (S. D. Ala. 1949),

aff’d 336 U. S. 933 ...................................................... 45

Dorchy v. Kansas, 264 U. S. 286 ............... ..................... 48

Doud v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 ....... ............................... 16, 46

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365 ................. 50, 51

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651...... ......................... 23

Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123...................................... 49

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, affirming 142 F. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) ...............................................16, 50

General Box Company v. United States, 351 U. S.

159 ............................................................................... 42

Government & Civic Employees Organizing Committee

v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364 ................................... 37, 42, 47

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Ass’n, 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E.

2d 602 (1940) ...................................... 24,28,29,30,31

Hartford Co. v. Harrison, 301 U. S. 459 ..................... 35

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24..... ..................................... 30

Hygrade Provision Co. v. Sherman, 266 U. S. 497 ...... 50

Hynes v. Grimes Packing Co., 337 U. S. 86 ................. 50

In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934) ............25, 30, 31

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 ....... ....................................... 23

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252 .... 24

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ....................................... 45

Logan v. United States, 144 U. S. 263 ......................... 23

PAGE

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501................................... 30

Mayflower Farms, Inc. v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266 ___ 35

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107................................ 25

V

Meridian v. Southern Bell T. & T. Co., 27 U. S. L.

Week 3235 (February 24, 1959) .........................36, 38, 39

Meredith v. Winter Haven, 320 U. S. 228 ..............16, 37, 46

Meyer v. Wells Fargo & Co., 223 U. S. 298..................... 48

Meyers v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 ........ -...................... ^4

Morey v. Bond, 354 U. S. 457 ...... - - - - - ........16,35,42,48

Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958), ceit.

denied 356 U. S. 968 .........-........................................

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 ....- ..........................

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .....-......—............ 15>18

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ............ -........-............. 35

Packard v. Banton, 264 U. S. 140 ............... - .................~

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U. S. 553 .............. 59

Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176 ............-........ 37

Philadelphia Co. v. Stimson, 323 IT. S. 605 ...... - ......... 50

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510...... 15,16, 24,

Propper v. Clark, 337 U. S. 472 ........... - ............. - .....38

Public Utilities Commission v. United States, 355 U. S.

~ 534 ............................................................................. 42’46

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312

u . s. 496 ..............................................-.................

Royal Oak Drainage Dist. v. Keefe, 87 F. 2d 786 (6th

Cir. 1937) ................................................................ 3

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners of State of New

Mexico, 353 U. S. 232 .............................................. 4^’

Shanks Village Committee Against Rent Increases v.

Cary, 103 F. Supp. 566 (S. D. N. Y. 1952) ..............

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 -----............................. "

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ~~~...... -............... ’

Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall. 36 --------- ------------

PAGE

VI

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 .................................... 35

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400 .......... 35

Spector Motor Co. v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101 ....38, 39,

42, 47

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378 ............................ 49

PAGE

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U. S. 367 ............................ 45

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197 ............................ 50

Terra! v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529 ...... 15, 22

Thallheimer v. Brinekerhoff, 3 Cow. 623, 15 Am. Dec.

308 (N. Y. Court of Errors 1824) .........................16, 27

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 89................................ 29

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385 ..................... 16, 42, 43, 46

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312 ................................ 22

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 ............................ 16, 35, 49, 50

Tyson & Bro. v. Blanton, 273 U. S. 418......................... 50

United States v. Lancaster, 44 Fed. 855 ..................... 23

Utah Fuel Co. v. National Bituminous Coal Comm.,

306 U. S. 56 ................................................................ 50

Vicksburg Waterworks Co. v. Vicksburg, 185 U. S. 65 .. 50

Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchison Amusement Co., 28 F.

Supp. 528 (D. Mass. 1939) ....................................... 31

Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 ................................... 50, 51

Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Andrews, 216 U. S.

165 ............................................................................... 49

Williams v. Standard Oil Co., 278 U. S. 235 ..............47, 48

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 35

O t h e b A u t h o r i t i e s

139 A. L. E. 622-623, 10 Am. Jur., Champerty and

Maintenance, §3 (1956) .............................................

Association of the Bar of the City of New York and

the New York County Lawyer’s Association,

Opinions of the Committees on Professional Ethics

(1956) ...................................................................30,31,

Brownell, Legal Aid in the United States (1951) ......

“Champion of the Indian,” N. Y. Times, March 3,

1958 .............................................................................

Church, “Trade Unionism and Crime,” New York

Times, Oct. 1, 1922 ......................................................

Davis, Ripeness of Governmental Action for Judicial

Review, 68 Harv. L. Rev. 1122 (1955) .....................

National Ass’n of Manufacturers, The Crime of the

Century and Its Relation to Politics .....................

National Committee for the Defense of Political

Prisoners, News You Don’t Get .............................. 29,

Radin, “Maintenance by Champerty,” 24 Calif. L. Rev.

48 (1935) ......... .........................................................26,

Schlesinger, Crisis of the Old Order (1957) ..............29,

Smith, Justice and the Poor (1921) .....................29,30,

43 Ya. L. Rev. 1241 (1957) ................................. ..........

Winfield, The History of Conspiracy and Abuse of

Legal Procedure (1921) ............................................

Winfield, “The History of Maintenance and Cham

perty,” 35 Law Q. Rev. 50 (1919) ............................

28

32

31

29

29

50

29

30

27

30

31

44

26

26

I n t h e

i$>upr£m£ (ftmirt nf tlw UmfrJi #tatps

No. 127

October Term, 1958

A lb er tis S. H a rrison , J r., Attorney General

of Virginia, et al.,

Appellants,

N a tio n a l A ssociation eob t h e A d v a n c em en t of C olored

P e o pl e , a Corporation, and NAACP L egal D e f e n s e and

E d u cational F u n d , I n c ., a Corporation,

________ Appellees.

a ppea l fro m t h e u n it e d states d istrict court for t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, RICHMOND DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement o f the Case

1. Proceedings Below

On November 28, 1956, appellees National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (the Association)

and N. A. A. C. P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (the Fund) brought separate actions for declaratory

and injunctive relief against the Attorney General of

Virginia and five Commonwealth Attorneys upon the claim

that Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 361 of the Acts enacted

1 “These Acts have been respectively codified in the Code of

Virginia at §§18-349.9, et seq., 18-349.17 et seq., 54-74, 78, 79;

18-349.25 et seq., and 18-349.31 et seq.” (E. 44).

2

by the General Assembly of Virginia at the 1956 Extra

Session are unconstitutional and in violation of the Com

merce Clause, and the First and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States (R. 1-15, 24-37, 44).

Appellants responded with identical motions to dismiss

which, inter alia, urged the District Court to withhold ex

ercise of its jurisdiction (R. 17, 39); and, after the denial

of these motions following a consolidated hearing thereon,

answers were filed which renewed the contentions of these

motions (R. 20 et seq., 40 et seq., 64). Trial on the merits

was set and heard September 16-19, 1957 (R. 129, 457).

Thereafter, on January 21, 1958, the District Court, one

judge dissenting, filed an opinion which declared Chapters

31, 32 and 35 unconstitutional and enjoined their enforce

ment as violative of the requirements of equal protection

and due process; but remitted appellees to the state courts

for an interpretation of Chapters 33 and 36 (R. 43 et seq.).

Judgment was entered on April 30, 1958 (R. 122-23).

Thereupon this appeal was perfected (R. 124-26); and

this Court noted probable jurisdiction on October 13,

1958 (R. 647).

2. Statutes Involved

Full texts of the lengthy statutes involved on this

appeal, i.e., Chapters 31, 32 and 35, have been set out in

Appellants’ Appendix I. The “cardinal provisions” of the

legislation assailed below, however, are succinctly sum

marized by the District Court (R. 52-53), as follows:

The five statutes against which the pending suits

are directed, that is Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36

of the Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia,

passed at its Extra Session in 1956, were enacted for

the express purpose of impeding the integration of

the races in the public schools of the state which the

3

plaintiff corporations are seeking to promote. The

cardinal provisions of these statutes are set forth

generally in the following summary.

Chapters 31 and 32 are registration statutes. They

require the registration with the State Corporation

Commission of Virginia of any person or corporation

who engages in the solicitation of funds to be used

in the prosecution of suits in which it has no pecuniary

right or liability, or in suits on behalf of any race

or color, or who engages as one of its principal ac

tivities in promoting or opposing the passage of legis

lation by the General Assembly on behalf of any race

or color, or in the advocacy of racial integration or

segregation, or whose activities tend to cause racial

conflicts or violence. Penalties for failure to register

in violation of the statutes are provided.

Chapters 33, 35 and 36 relate to the procedure for

suspension and revocation of licenses of attorneys at

law, to the crime of barratry and to the inducement

and instigation of legal proceedings. It is made un

lawful for any person or corporation: to act as an

agent for another who employs a lawyer in a proceed

ing in which the principal is not a party and has no

pecuniary right or liability; or to accept employment

as an attorney from any person known to have vio

lated this provision; or to instigate the institution of

a law suit by paying all or part of the expenses of

litigation, unless the instigator has a personal interest

or pecuniary right or liability therein; or to give or

receive anything of value as an inducement for the

prosecution of a suit, in any state or federal court

or before any board or administrative agency within

the state, against the Commonwealth, its departments,

subdivisions, officers and employees; or to advise,

counsel, or otherwise instigate the prosecution of such

4

a suit against the Commonwealth, etc., unless the in

stigator has some interest in the subject or is related

to or in a position of trust toward the plaintiff.

Penalties for the violation of these statutes are pro

vided.

The legislative history of these statutes to which we

now refer conclusively shows that they were passed

to nullify as far as possible the effect of the decision

of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483 and 349 U. S. 294.

3. Statem ent o f Facts

Although appellees know that this Court previously con

sidered the functioning of the Association in National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, and even though we believe that

the opinion of the .District Court contains a concise state

ment of the material facts (R. 45-52, 53-60, 61), we feel

obliged to present our statement of facts because appel

lants’ presentation of the case does not state all that is

material to the consideration of the questions raised on

this appeal.

The Association and the Fund are each non-profit New

York membership corporations (R. 45, 49, 276, 498-99).

Both are registered in the Commonwealth of Virginia as

foreign corporations (R. 45, 49, 191-92, 276-77). The ac

tivities engaged in pursuant to their charters, their organi

zational structure and their mode of operation, however,

differ.

“The Association”

Organized in 1909, the Association was incorporated in

1911 (R. 45, 165, 496-502) for the following principal

purposes:

5

. . . voluntarily to promote equality of rights and

eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens

of the United States; to advance the interest of

colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage;

and to increase their opportunities for securing justice

in the courts, education for their children, employ

ment according to their ability, and complete equality

before the law.

To ascertain and publish all facts bearing upon

these subjects and to take any lawful action thereon;

together with any and all things which may lawfully

be done by a membership corporation organized under

the laws of the State of New York for the further ad

vancement of these objects (R. 45-46, 498-99).

And its ultimate goal, in short, may be said to be the eradi

cation of those twin viruses of second class citizenship—

segregation and discrimination based on race or color

(R. 170).

To these ends the Association engages in three broad

types of activity: one, contributing monies to defray the

costs of litigation, including attorneys’ fees, which chal

lenges the validity of governmentally imposed or enforced

segregation and discrimination on account of race or color;

two, promoting legislation which would tend to eliminate

such segregation or discrimination and opposing legisla

tion which would restrict the opportunities/of the Negro

minority for equalitarian status or deny them rights secured

under the law of the land; and, three, disseminating through

public speeches and printed publications information which

advocates racial nonsegregation in the enjoyment of pub

lic facilities and which also publicizes the Association’s

objectives and activities (R. 170-71, 172, 179, 180). To con

duct these activities, income and fund raising, of necessity,

are constant ingredients in the program of the Association

(R. 172).

6

N.A.A.C.P. activities are carried on in Virginia by

local members of the Association and such officers or em

ployees of the Association as are requested to supply their

talents by the local membership (R. 172-73). This member

ship, in conformity with the charter and constitution of the

Association (R. 498-99, 503), is organized into 89 chartered

affiliates called Branches which, jointly with the Associa

tion, contribute toward the support of a statewide sub

ordinate unit named the Virginia State Conference of

N.A.A.C.P. Branches (the State Conference) (R. 46, 134,

135-36, 168-70).

The State Conference is the spearhead of the Associa

tion’s activities in Virginia; for it not only coordinates

the activities of the Branches and supervises local member

ship and fund raising campaigns but it also represents and

acts for the entire Virginia membership on matters of state

wide importance (B. 47, 134, 135-36). It appears before

the General Assembly and State Commissions to voice

support of, or opposition to, measures which, according to

its construction, advance or retard the status of the Negro

in Virginia (R. 47, 134, 136). It conducts intensive educa

tional programs designed to encourage Negroes to satisfy

voting requirements and vote (R, 47, 134, 135), to acquaint

the people of Virginia with the facts regarding the harmful

aspects of racial segregation and discrimination (R. 47,

134), and to instill in Negroes a knowledge of their legal

rights and encourage their assertion when violations

occur (R. 47, 135, 148). In carrying out this program all

of the media of free expression of ideas are used, e.g.,

public meetings, conferences, distribution of pamphlets,

letter writing, etc. (R. 47-48, 147-48).

Furthermore, the State Conference contributes, or obli

gates itself to contribute, financial assistance for defraying

all or part of the counsel fees and costs incurred in litiga

7

tion involving racial discrimination or segregation (E. 48,

135, 136, 142-43). Before the Conference obligates itself

in a case, several criteria must be met. First, there must

be a genuine grievance involving discrimination on account

of race or color; secondly, the complaint must involve of dis

crimination or segregation imposed under the color of state

authority and it must present a justiciable controversy (R.

48,150-52,156,184, 207, 210).

In the furtherance of its legal program the State Con

ference has established a legal committee, commonly re

ferred to as the Legal Staff; and, at present, it is composed

of thirteen members located in seven different communi

ties scattered over most of the state (R. 48, 157). The

members of the Legal Staff are elected at the annual con

vention of the State Conference and they in turn elect a

Chairman (Id.).

Cases usually arise by the aggrieved parties contacting

a member or members of the Legal Staff, but in a number

of instances the grievance is brought to the attention of

the Executive Secretary of the Conference who refers the

complaining parties to the Chairman of the State Legal

Staff if there appears to be a genuine grievance involving

racial discrimination or segregation (R. 48, 149-50, 207).

The Chairman confers with the aggrieved party and then

decides whether the discrimination or segregation suffered

is imposed under color of state authority and presents a

justiciable controversy (R. 48, 150, 209, 210). If the deci

sion is that the complaint squares with these criteria, the

Chairman informs the complainant that he will recommend

that the Conference assist him in his ease (R. 48, 150, 209).

The Chairman communicates his recommendations to the

President of the State Conference and upon his concur

rence the Conference obligates itself to defray in whole

or part the costs and expenses of the litigation (R. 48,

8

150). Counsel for the complainants, either by choice or

acquiescence, has usually been a member or members of

the Conference’s Legal Staff (E. 48, 152, 153, 159, 324).

Finally, when the Conference honors its obligation, it

reimburses the litigant’s counsel for out-of-pocket expendi

tures (for travel, stenographic service, etc.) and pays

him a per diem compensation for the days spent in prepara

tion and trial of the litigation (R. 48, 209-10, 646-47). Com

pensation of counsel on such a basis is not only modest but

far out of proportion to the actual time and energy spent

in civil rights litigation (R. 321, 325, 329); and counsel

have accepted even less than due under this formula (R.

331).

The principal source of income for the Association and

its units is derived from membership fees solicited during

the various local membership drives; other sources of in

come are public fund raising rallies or meetings and con

tributions, some of which are not solicited direetly/(R. 46,

148, 163, 169). The Association enrolled 13,595 mem

bers in Virginia during the first eight months of 1957

(R. 46, 136, 137, 174), and the majority of the Branches in

Virginia conduct their annual membership drives in the

spring and summer months (R. 176). By contrast, mem

bership figures for the same eight month period for the

previous three years were 19,436 in 1956, 16,130 in 1955 and

13,583 in 1954 (R. 46, 137, 174).

The income of the Association from its Virginia Branches

for the first eight months of 1957 was $37,470.60 as com

pared with $43,612.75 for the same period in 1956 (R. 46-47,

68, 173, 642, 643).

Of the $38,469.59 which the Association received from

all sources in Virginia during the first eight months of

1957, $37,470.60 came from Branches (R. 46, 68, 173, 642).

9

The corresponding amounts for the same period in 1956

are $44,138.71 and $43,612. (R. 46, 68, 643). From the

country as a whole—the Association has branches in 44

states and the District of Columbia (R. 46, 67)—the Asso

ciation’s income for the first eight months of 1957 and 1956

was $425,608.13 and $598,612.84, respectively (R. 46-47, 68,

173, 642, 643).

The fall off in Virginia memberships and drop in income

from Branches tiled to the impact of

the challenged legislation/(R. 61, 62-63, 140, 141). Inquiries

made by solicitors working in Branch membership cam

paigns and samplings made by the Executive Secretary of

the State Conference revealed that/individuals who failed

to renew their memberships, as well as former campaign

workers, were generally apprehensive as to the application

of the assailed legislation to themselves and feared that

reprisals would be directed against them should their mem

bership in the Association be made a matter of public

record (R. 61, 137, 139-41, 236-38).

Public identification of Virginians as members of the

Association (R. 61, 234-35, 251, 254, 263), or as plaintiffs

in the antisegregation suits in which the Association is

identified (R. 230, 239, 252, 258), or as advocating compli

ance with the antisegregation decisions of federal courts

(R. 244-45, 264-65) has exposed them and their families to

threats of violence to person and property (R. 61, 232, 246,

260-61, 265, 266), various forms of intimidation such as

cross-burning (R. 61, 246-47, 265-66) and the hanging of

an effigy (R. 61, 255), social ostracism (R. 61, 248, 266),

economic reprisals (R. 239-41, 248) and a variety of per

sonal annoyances such as persistent insulting or obscene

anonymous telephone calls, letters and “bus stop editorials”

(R. 61, 230-32, 234-36, 245-46, 251-52, 253-54, 258-61, 265-66).

The experiences of most of these “exposed persons” and

1 0

many others, too, have been given widespread publicity in

Virginia newspapers (E. 61, 127, 269-72, 459-63), including

Negro as well as white publications (E. 269-72, 459-63,

492).

The local press, by publishing news stories and columns

which described the assailed legislation as being anti-

N.A.A.C.P. measures with grave penalties for any violation

thereof, again gave cause for the apprehensiveness regard

ing the application of the challenged legislation to members,

contributors and all other persons who associate themselves

with the activities of either the Association or the Fund

(E. 61, 140, 191, 236-38, 269-72, 274, 459-63). Laymen were

not alone in this boat; similar analyses made members

of the legal profession hesitant and apprehensive, too

(E. 61, 321-22, 326, 330).

“The Fund”

The Fund was incorporated in 1940 (E. 49, 276) and its

charter describes its principal purposes as follows:

(a) To render legal aid gratuitously to such Negroes

as may appear to be worthy thereof, who are suffer

ing legal injustices by reason of race or color and

unable to employ and engage legal aid and assistance

on account of poverty.

(b) To seek and promote the educational facilities for

Negroes who are denied the same by reason of race

or color.

(c) To conduct research, collect, collate, acquire, compile

and publish facts, information and statistics concern

ing educational facilities and educational opportuni

ties for Negroes and the inequality in the educational

1 1

facilities and education opportunities provided for

Negroes out of public funds; and the status of the

Negro in American life (R. 49, 277-78, 304).

Moreover, inasmuch as the Fund’s purposes include ren

dering legal aid and services, its activities as a legal aid

society have been approved by the Appellate Division of

the Supreme Court of New York, First Judicial Depart

ment, without objections from any of the several bar asso

ciations (R. 49-50, 314).

Unlike the Association, the Fund has no affiliated or

subordinate units (R. 50, 278); its one office is located in

New York City (Id.). In order to implement its objec

tives, the Fund employs a full-time staff of six resident

attorneys and three research attorneys, all of whom are

stationed in New York (R. 50, 279, 281), two educational

specialists (R. 303), one of whom is in the field, and a social

scientist who does non-legal research (R. 303). The Fund

has also secured the services of four lawyers on annual

retainers (R. 50, 279); they reside in and conduct their

private practices at Richmond, Dallas, Los Angeles and

Washington, D. C. (R. 50, 279, 288, 301-02). Moreover,

the Fund has engaged other counsel on a case-by-case fee

basis for investigations and research (R. 50, 285-86, 298,

319). And the Fund has on call about a hundred attorneys

(R. 50, 278) and a large number of social scientists (R. 50,

286, 292) whose services are available on a volunteer or

expenses-only basis.

Participation in litigation which falls within the scope

of its charter, legal and general research, the dissemina

tion of information and fund raising are the activities car

ried on by the Fund (R. 49, 50, 277-78, 279, 281)./With

respect to litigation, the Fund’s policy forbids it from tak

ing any part in a case unless a request for services or funds

is made by either the party in interest or his attorney (R.

1 2

280, 290). If this is done, and the case not only involves

a threatened or actual denial of civil rights hut is basically

meritorious, the Fund furnishes the requested assistance—

advice, services or finances including the entire cost of

litigation and lawyers fees (R. 279, 284-85, 318-19).

Since its inception, the Fund has been associated in some

way with about every leading civil rights case (R. 50,

281-83). Moreover, it is unique in that no other organiza

tion provides gratuitously the assistance and services

which it does either on a national basis or in Virginia

(R. 50, 283, 292, 293).

A considerable amount of the Fund’s efforts is devoted

to research (R. 51, 281, 298, 319). In the main, the legal

research done by staff members and volunteers is utilized

in connection with pending litigation although it is avail

able for use by lawyers and law schools (R. 50, 279, 287).

The educational activities of the Fund are varied. In

addition to disseminating research materials, staff members

do considerable public speaking at meetings sponsored by

community organizations as well as lecturing in colleges

and universities on various topics, ranging from constitu

tional law through civil rights to patterns of human rela

tions (R. 50, 281). Moreover, the staff disseminates the

fruit of case experience and field studies in the form of

memoranda and articles published by professional journals

and general periodicals (R. 279, 287).

Fund raising for the support of its activities is limited

to the solicitation of contributions; the principal fund rais

ing activity consists of four quarterly mailings sent out by

a group of volunteers called the Committee of One Hun

dred, but solicitations are also made at social affairs and

public meetings sponsored by other volunteer groups for

the benefit of the Fund (R. 51, 293, 295, 313). fContribu-

13

tions are its sole source of income since neither fees nor

dues are requirements for Fund membership (B. 51, 294).

For four or five years prior to 1957, the Fund’s income

rose steadily i in 1956, it totaled $351,283.32 (B. 51, 294,

318). Beginning September 1956, due to the fact that the

Fund’s volunteer solicitors had to drop Texas from the

list of states in which services and assistance were avail

able—the state having restrained its operations during

that time, income dropped off steadily (B. 68, 294-95).

Another drop is reflected in the comparative income for

the first eight months of 1957 and that for the same period

in 1956: $152,000 and $246,000, respectively (B. 51, 68,

294) , i.e., after the precariousness of Fund operations in

Virginia was widely publicized ( B. 68-69).

While studies by professional fund raising advisors re

veal that^he Fund’s income from Virginia cannot be deter

mined precisely because many Virginia contributors wmrk

in and mail their contributions from Washington, Fund

income from Virginia to the extent that is shown on the

books shows a decline from/$6,256.19 in 1955 to $1,859.20

in 1956 to $424.00 for the first two-thirds of 1957 (B. 51,

295) .

As to the Fund expenditures for services in Virginia,

exclusive of the services and personal counsel contributed

by the New York Staff in Virginia litigation (e.g., see B.

51, 318), the amounts are $6,344.39 in 1954, $6,000.00 in

1955, $6,490.00 in 1956 and $3,500.00 in 1957 for the first

eight months (B. 296).

There is no dispute on the record as to the effect of the

assailed statutes upon the operations of the Fund in Vir

ginia, especially in the present atmosphere of fear and un

easiness: contributions have dwindled and would cease (B.

51, 68, 295, 296, 297-99) with a resulting cessation of con

tributions from the intransigent South (B. 297); many law

14

yers, white as well as Negro, would not work for or with the

Fund (R. 298, 322, 326, 330); and the Fund would be re

strained from participating in civil rights litigation and

utterly destroyed (R. 298-99).

It is on the basis of the foregoing facts, plus a considera

tion of companion enactments passed by the General As

sembly of Virginia (R. 54-60, 131-32, 506 et seq.),"ttet the

District Court concluded (R. 61-62):

In view of all the evidence, we find that the activities

of the State authorities in support of the general plan

to obstruct the integration of the races in schools in

Virginia, of which plan the statutes in suit form an

important part, brought about a loss of members and

a reduction of the revenues of the [appellees] and made

it more difficult to accomplish [their] legitimate aims.

Summary o f Argument

Immediately after the 1954 decision in the Brown case,

the Commonwealth of Virginia acting through its Governor

and legislature set out to prevent compliance with that

decision. Thus, Virginia embarked on its plan of “massive

resistance”, which included resolutions of “Interposition”

and other attacks on this Court followed by the convening

of the 1956 Extra Session of its General Assembly to con

sider recommendations “to continue our system of segre

gated public schools.” The General Assembly responded

by promptly adopting legislation (1) prohibiting use of

public funds for integrated schools, closing of integrated

schools and establishing a pupil assignment law; and (2)

the statutes here complained of “as parts of the general

plan of massive resistance to the integration of schools

of the state under the Supreme Court’s decrees.”

15

The combined effect of the statutes in suit is to prevent

Negroes in Virginia from effectively securing compliance

with the Brown decision. In so doing, these statutes deny

and curtail First Amendment rights of freedom of expres

sion and other rights protected by the equal protection and

due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chapters 31 and 32, requiring appellees to annually file

membership lists and, if requested, to file lists of contribu

tors as a prerequisite to continuing their activities, run

afoul of the protections guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment. National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449.

All three statutes deny free access to the courts, a right

which has long been recognized and protected by the Con

stitution. Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529.

While Chapters 31 and 32 seriously impair effective liti

gation by destroying the posibility of obtaining necessary

funds, Chapters 32 and 35 go a step further and prevent

lawyers from continuing to participate in group sponsored

racial segregation cases. The prohibitions in these statutes

apply to pending as well as future litigation to bring about

compliance with this Court’s decisions in racial segregation

cases. Such state interference with these lawful practices

denies liberty within the meaning of the Constitution.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510; Sckware v.

Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232.

Appellants have not and cannot show any overriding

justification for state interference with lawful activities.

Their claims that these statutes are necessary to preserve

peace and order in regard to racial matters has long since

been declared to be without constitutional significance.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1; Buchanan v. War ley, 245

U. S. 60.

<

The barratry statutes, while defended as expressions of

the common law, are in fact in derogation thereof. Thall-

heimer v. Brinckerhoff, 3 Cow. 623, 15 Am. Dec. 308 (N. T.

Court of Errors 1824).

To an unprecedented degree in Chapter 35, and to a lesser

degree in Chapters 31 and 32, Virginia deliberately ex

cluded every conceivable group other than appellants from

the restrictions of freedom of expression, enforcement of

barratry provisions and other repressive measures. Such

unwarranted classifications certainly deny equal protection.

Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457.

The District Court was not required by the doctrine of

equitable abstention to postpone decision of the constitu

tional issues pending previous consideration of the statutes

by the state courts. The cases did not present issues

peculiar to the state’s jurisprudence, or necessitate resolu

tion of local law questions preliminary to consideration of

the federal issues. The statutes are clear and unambiguous,

and remission for definitive construction was unnecessary.

Chicago v. Atcheson, T. & S. F. R. Co., 357 U. S. 77;

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. 38. 385. There being no recognized

policy that remission could serve, the District Court prop

erly decided the issues here on appeal. Meredith v. Winter

Haven, 320 U. S. 228; Doud v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485.

Finally, whatever may be the rule as to enjoining en

forcement of state criminal statutes in other circumstances,

the District Court properly restrained appellants from

enforcing Chapters 31, 32 and 35 under the circumstances

shown in these cases. See Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33;

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 IT. S. 510; Gayle v. Browder,

352 U. S. 903, affirming 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956).

16

17

A R G U M E N T

I.

These Virginia statutes not only curtail lawful activi

ties o f two m em bership corporations and o f their m em

bers, contributors, and attorneys, but also strike at basic

civil rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution.

Chapters 31 and 32 violate rights secured to appellees,

their members, contributors and attorneys, by the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Chapters 31 and 32 accomplish this by re

quiring disclosures, from the making of which appellees

are constitutionally immune, as conditions precedent to the

exercise of all of their major functions. Chapter 35 addi

tionally operates to totally prohibit activities vital to their

continued existence.

Chapter 31 provides that before appellees may solicit or

expend funds to defray the expenses of civil rights litiga

tion they must annually file with the State Corporation

Commission a certified list of the names and addresses of

their members and, if requested, the names and addresses

of their contributors.

Chapter 32 requires registration and similar disclosures

before either appellee may advocate compliance with the

decision of this Court in the Brown ease or raise or expend

funds to aid in civil rights litigation toward that end, and

before the appellee Association may promote or oppose

legislation in behalf of any race or color.

Chapter 35 unqualifiedly prohibits either organization

from paying any part or all of the expenses of litigation in

which it is not personally or pecuniarly involved.

18

The effect of these laws is to abridge, not merely one,

but each of several constitutional freedoms to which the

appellees may justly lay claim. Each, in the exercise

of its right of free speech, advocates the abolition of govern-

mentally-imposed racial discrimination, by aiding litigation

in the civil rights field as well as by more traditional

media, and, in the case of the Association, by promoting

legislation according to its views. They have for many

years exercised a liberty, inherent in due process, by as

sisting others in their litigation to obtain protection from

state abridgements of their federally-protected rights.

In so doing, and by necessary exercise of their freedom of

association, appellees, their members, contributors and

others of a like mind have pooled their efforts and financial

resources with a view to making possible the attainment of

these objectives.

The legislative mandates of Chapters 31, 32 and 35 pro

hibit the appellees, and all persons affiliated with them,

either absolutely, or on pain of disclosure of affiliation that

due process renders inviolate, from taking collective action

to effectively vindicate the constitutional principles they

each espouse. And, this is sought to be accomplished by

legislation so framed, not only as to leave similar group

sponsored suasion and litigation activities free from regula

tion, but also to put the appellees “out of business by for

bidding them to encourage and assist colored persons to

assert rights established by the decisions” (R. 90).

A. C om pu lsory D isclosure o f O rganisational Affiliates W here

E conom ic R eprisa ls and O th er M anifestations o f Public

H o stility W ill E nsue V iolates the F ourteen th A m en dm en t.

There can no longer be doubt as to the protection ex

tended by the Fourteenth Amendment against “compelled

disclosure of affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy.”

National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo-

19

pie v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 462. This Court there held

invalid an Alabama court order similar to the membership

disclosure requirements of Chapters 31 and 32, and said:

Effective advocacy of both public and private points

of view, particularly controversial ones, is undeniably

enhanced by group association, as this Court has more

than once recognized by remarking upon the close nexus

between the freedoms of speech and assembly. . . . It

is beyond debate that freedom to engage in association

for the advancement of beliefs and ideas is an insep

arable aspect of the “liberty” assured by the Due Proc

ess Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which em

braces freedom of speech.. . . Of course, it is immaterial

whether the beliefs sought to be advanced by associa

tion pertain to political, economic, religious or cultural

matters, and state action which may have the effect of

curtailing the freedom to associate is subject to the

closest scrutiny (at pp. 460-461).

These considerations apply with peculiar force to appel

lees—organizations which are media of expression for those

who affiliate to oppose racial discrimination. In Alabama,

this Court recognized “the vital relationship between free

dom to associate and privacy in one’s associations” (at

p. 462) and stated:

Inviolability of privacy in group association may in

many circumstances be indispensable to preservation

of freedom of association, particularly where a group

espouses dissident beliefs.

There, this Court also held that:

We think that the production order, in the respects

here drawn in question, must be regarded as entailing

the likelihood of a substantial restraint upon the exer

cise by petitioner’s members of their right to freedom

2 0

of association. Petitioner has made an uncontroverted

showing that on past occasions revelation of the iden

tity of its rank-and-file members has exposed these

members to economic reprisal, loss of employment,

threat of physical coercion, and other manifestations

of public hostility. Under these circumstances, we think

it apparent that compelled disclosure of petitioner’s

Alabama membership is likely to affect adversely the

ability of petitioner and its members to pursue their

collective effort to foster beliefs which they admittedly

have the right to advocate, in that it may induce mem

bers to withdraw from the Association and dissuade

others from joining it because of fear of exposure of

their beliefs shown through their associations and of

the consequences of this exposure (at pp. 462-463).

Similarly, in the cases at bar, the District Court found:

[T]he Acts now before the court were passed as parts

of the general plan of massive resistance to the integra

tion of schools of the state under the Supreme Court’s

decrees. The agitation involved in the widespread dis

cussion of the subject and the passage of the statutes

by the Legislature have had a marked effect upon the

public mind which has been reflected in hostility to the

activities of the plaintiffs in these cases. This has been

shown not only by the falling off of revenues, indicated

above, but also by manifestations of ill will toward

white and colored citizens who are known to be sympa

thetic with the aspirations of the colored people for

equal treatment, particularly in the field of public edu

cation (R. 60-61).

and that the statutes will bring about the imposition of

hostile sanctions on appellees’ members:

2 1

Begistration of persons engaged in a popular cause

imposes no hardship while, as the evidence in this case

shows, registration of names of persons who resist the

popular will would lead not only to expressions of ill

will and hostility but to the loss of members by the

plaintiff Association (B. 79).

Here, as in Alabama, the record falls short of demonstrat

ing “a controlling justification for the deterrent effect on

the free enjoyment of the right to associate” which the dis

closures required by Chapters 31 and 32 will have./To sup

port Chapter 32, appellants say that its purposes are “ (1) to

help in selection of deputies, and prevent deputizing a per

son participating actively in an organization agitating vio

lence ; (2) to identify certain known troublemakers as mem

bers of particular organization, and to thereby identify their

leaders; (3) to keep a check on agitators from outside the

community; (4) a list of the members of a local organiza

tion would apprise sheriffs of the possibilities of violence

from such organization; and (5) a possible deterrent to

persons against joining organizations under irresponsible

leadership or engaged in unlawful activities” (Brief for

Appellants, p. 58).

Chapter 31 is sought to be justified “as an aid to detect

those persons who are engaged in barratry, maintenance,

unauthorized practice of law and related offenses” (Brief

for Appellants, p. 59).

Assuming arguendo that the above “justifications rep

resent the statutes’ true purposes, and conceding the desira

bility of a state being able to detect law violators, and sup

press racial conflicts or violence, nevertheless such ends

may not be achieved by denying rights secured by the Con

stitution. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 II. S. 1; Buchanan v. War-

ley, 245 U. S. 60, 81. Furthermore the legislative history of

2 2

the statutes, as well as their explicit exemptions for all

but those seeking racial equality before the law, casts the

gravest doubt on whether these considerations are in fact

the State’s basis for having enacted the laws in question.

B . D enial o f Access to the C ourts.

As the court below found: “The legislative history of

these statutes to which we now refer conclusively shows

that they were passed to nullify as far as possible the effect

of the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of

Education . . . ” (R. 53). When these statutes were adopted

there were several cases pending in federal courts in Vir

ginia seeking compliance with the Brown decision (R. 82),

including the Prince Edward County Case (one of the four

cases consolidated in the Brown decision) (R. 82).

Each appellee is well known for its willingness to

assist in litigation and to protect Negroes from unlawful

racial discrimination (R. 82). Most of the money by which

appellees are enabled to render charitable aid by defraying

court costs (and, in the case of the Fund, providing legal

assistance) is raised by public fund solicitation.

Chapters 31 and 32 require disclosure of membership

lists, etc., as a prerequisite for such public solicitation

as well as for such charitable aid. Chapter 35 expressly for

bids such charitable assistance. What Chapter 35 does

directly is also indirectly accomplished by Chapters 31 and

32. The three statutes together effectively block access to

the courts by Negroes in Virginia who are desirous of se

curing judicial protection for their constitutional rights.

Unfettered access to the courts is the right of every citi

zen. Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529. See

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312, 334; Barbier v. Connolly,

113 U. S. 27, 31; Slaughter House Cases, 16 Wall. 36; Cran

dall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 36, 44. The primary right of Virginia

23

residents to resort to the federal courts to secure relief

from state-imposed racial segregation stems from the Con

stitution itself (Article III, Section 2, Clause 1). Cases

involving state enforced racial segregation arise under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and the civil

rights statutes enacted by the Congress pursuant thereto,

e.g., Title 42, United States Code, §§1971, 1981-83. And

see, Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3).

Implied in this right of access to the federal courts is

the right to assist and the right to accept assistance neces

sary to adequately present the issues to these courts.2 The

cases against state-imposed racial segregation are too

costly for the average individual Negro litigant, Arrayed

against such litigant is the state treasury, the attorney-

general, his staff and an unlimited number of special assist

ants, as well as attorneys-general from other southern

states anxious “to lend a hand in the fight against the

NAACP” (E. 472). To leave the federal courts open to

only those litigants individually able to finance such a case

and the appeals involved is to effectively close the door to

the great majority of aggrieved Negro citizens.

C. D ep riva tion o f L iberty .

Although the Court has not assumed to define

“liberty” with any great precision, that term is not con

fined to mere freedom from bodily restraint. Liberty

2 As in the case of all other constitutional rights, powers, and

duties, there are a number of rights which clearly arise by neces

sary implication, e.g., Logan v. United States, 144 U. S. 263, held

that there was an implied duty on the part of the United States

to protect prisoners in its custody against lawless violence (at

285) ; United States v. Lancaster, 44 Fed. 855, where the court

upheld an indictment charging interference with the right to

bring an action in the federal court. Ex parte Yarbrough, 110

U. S. 651, involving protection of federal elections from violence

and corruption and In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1, involving protection

of federal judges in the exercise of their judicial function.

24

under law extends to the full range of conduct which

the individual is free to pursue, and it cannot be re

stricted except for a proper governmental objective.

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 TJ. S. 497, 499-500.

The right to engage in lawful activities or to pursue a

profession free from arbitrary governmental restraint is

protected by the Constitution. Appellees’ activities are

aimed at the eradication of racial discrimination from

public life in America through peaceful persuasion and

the securing of rights guaranteed Negroes by the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States by aiding these persons

to obtain vindication thereof in the courts.

The lawyers who cooperate with appellees toward achieve

ment of these aims are of course engaged in the pursuit

of their professions. Cf. Konigsberg v. State Bar of Cali

fornia, 353 U. S. 252; Schwure v. Board of Bar Examiners

of the State of New Mexico, 353 U. S. 232; Pierce v. Society

of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510; Bartels v. Iowa, 262 U. S. 404;

Meyers v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390.

The destructive impact of Chapter 35 on the right of

attorneys associated with appellees to practice their pro

fession and of appellees to render charitable legal aid is

clear. Lawyers who volunteer their professional services

in cases which appellees support are restricted by the

burdensome disclosure provisions of Chapters 31 and 32,

and, far more serious, are subject to disbarment as well

as original penalties under Chapter 35.

In addition, as the court below held, Chapter 35 violates

the right of appellees and the lawyers associated with them

without due process of law by its failure to take into ac

count the well established rule that lawyers may volunteer

their services to the poor and exploited, Gunnels v. Atlanta

Bar Association, 191 da. 366, 12 S. E. 2d 602, even in

25

controversial causes, In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467, 475 (D.

Md. 1934), when acting for benevolent purposes, and may-

act for charitable societies without violating the ethics of

the profession (Canon 35, Canons of Professional Ethics,

ABA). And as the court below found, “the activities of

the plaintiff corporations are not undertaken for profit or

for the promotion of ordinary business purposes, but,

rather, for the securing of the rights of citizens without

any possibility of financial aid.” Their activities are also

covered by Canon 35. Finally, the court below held that

Chapter 35 violates due process “for it is designed to put

the plaintiff corporations out of business by forbidding

them to encourage and assist the colored persons to assert

rights established by the decisions” of this court (R. 281,

298, 319).

D. V irgin ia Has Show n No ju stifica tio n fo r C h apter 35 .

Appellants’ sole justification for Chapter 35 is “that the

State is merely regulating the activities that have long

been prohibited by the common law and condemned by the

legal profession” (Appellants’ Brief, p. 63). Unlike the

statute in McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107, Chapter 35

is not simply a reaffirmation of a common lawT principle of

wide acceptance. Rather, it is an undertaking to innovate

upon the common law by introducing a prohibition of con

duct heretofore considered valid.

Common law and statutory barratry contain two ele

ments: (1) continuously stirring up groundless judicial

proceedings; (2) doing so either for one’s own profit or for

the purpose of vexing the defendants.3 Barratry, says one

3 For common law definitions see Winfield, P. H., The History

of Conspiracy and Abuse of Legal Procedure (Cambridge 1921),

p. 200. For a typical statutory definition see Consolidated Laws

of New York §320 “common barratry is the practice of exciting

groundless judicial proceedings,” and §322 “No person can be

26

writer, is closely related to maintenance; one common

law definition holds it to be continuous maintenance.4 Pre

cise statutory definitions of maintenance as a separate

offense are rare,5 but at common law it was generally

defined as the offense of officiously aiding another in his

suit.6 Champerty is said to be a species of maintenance.7

Widely condemned by statute,8 champerty is the offense of

maintaining another’s suit pursuant to agreement to re

ceive part of the proceeds.9

Barratry, maintenance and champerty reached their

zenith in England as a concomitant of the feudal system.

convicted of common barratry except upon proof that he has

excited actions or legal proceedings, in at least three instances,

with a corrupt or malicious intent to vex and annoy.” See also

Arizona Revised Statutes (1956) §13-261; California Ann. Code

1954 §§158-159; Colorado Revised Statutes (1953) §40-7-40;

Georgia Code Ann. (1935) §26-4701; Idaho Code Ann. (1940)

§18-1001; Illinois Statutes Ann. Chapter 38, §65; Montana Revised

Code (1947) §94-3533-34; Nevada Revised Statutes (1957)

§199,320; New Mexico Statutes (1953) Chapter 40-26-1; North

Dakota Revised Code (1943) Chapter 12-1716 and 1717; Okla

homa Statutes Ann. (i937) Title 21, §§550 and 552; Pennsyl

vania Statutes Ann. (1945) Title 18, §4306.

4 Radin, Max, “Maintenance by Champerty,” 24 California Law

Review 48, 64 (1935).

5 See Illinois Statutes Annotated, Ch. 38, §66 and Colorado Re

vised Statutes (1953) §40-7-41.

6 Winfield, P. H., “The History of Maintenance and Champerty,”

35 Law Quarterly Rev. 50, 56 (1919).

7 Winfield, op. cit., supra, ftn. 3, at 131, 140.

8 Ala. Code (1940) Title 16, §53; Del. Code Annotated (1953)

11 §371; Kentucky Revised Statutes Annotated (1955) §§372.060,

372.080, 372.110; Maine Revised Statutes (1954) C. 135, §18;

Michigan Statutes Annotated (1937) §27.94; New Jersey Statutes

Annotated (1952) 2A:170-83; N. Y. Penal Law §274; Oklahoma

Statutes Annotated (1937) Title 21, §§547, 548, 554, 558, 562-564;

Tennessee Code Annotated (1956) 64-406, 64-407; Utah Code

Annotated (1953) §78-51-27; Virginia Code (1950) §54-70.

9 Winfield, op. cit., supra, ftn. 3, at 131.

27

The evil consisted primarily of “support given by a feudal

magnate to his retainers in all their suits, without any refer

ence to their justification.” 10 “This type of support be

came in fact one of the means by which powerful men

aggrandized their estates and the background was unques

tionably that of private war.” 11 The need for heavy crimi

nal sanctions ceased with the decline of feudalism.12 Con

sequently, although barratry and champerty remain on

the books, convictions nowadays are rare.13

The common law soon recognized exceptions to mainte

nance, Thallheimer v. Brinckerhoff, 3 Cow. 623, 15 Am. Dec.

308 (New York Court of Errors 1824) noted these excep

tions :

. . . consanquinity or affinity between the suitor and

him who gives aid to the suit . . . relation of landlord

and tenant, that of master and servant, acts of charity

to the poor and the exercise of the legal profession, . . .

(Emphasis added.)

[The laws] were intended to prevent the interference

of strangers having no pretense of right in the subjects

of the suit, and standing in no relation of duty to the

suitor . . . to prevent traffic in doubtful claims, and to

operate upon buyers of pretended rights, who had no

relation to the suitor or the subject, otherwise than

as purchasers of the profits of litigation (at 647-648).

See also, Brush v. Carbondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252

(1907).

10 Radin, supra, ftn. 4, at 64.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Id. at 67.

28

With the development of a mercantile society, champerty

has been modified to permit contingent free arrangements,

etc.14

Statutory barratry remains essentially as set forth

above, but an exception has developed: “ . . . the offense

of barratry does not consist in promoting either private

suits or public prosecutions when the sole object is the at

tainment of public justice or private rights, but on the

prostitution of these remedies to mean and selfish pur

poses.” 10 See also Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Assn., 191 Gla.

336,12 S. E. 2d 602 (1940).

Disregarding the basic elements of barratry and the

well established exceptions thereto, Virginia, under the

guise of protecting the administration of justice, now de

fines barratry in such a way as to put appellees out of

business.16 Virginia’s definition of barratry seems never

to have appeared before, and individual or group financing

of litigation founded on bona fide charitable motives seems

never to have been condemned in the past.

Because of the severity of the opposition of states offi

cially resisting desegregation Negro citizens must act col

lectively to secure their constitutional rights. No indi

vidual Negro can effectively pit his strength against the

organized resistance of state governments. Consequently,

the challenge to state-enforced racial segregation is being

made on a group basis. In view of this, civil rights cases

14 Id. at 68.

15139 A. L. R. 622-623, quoted in 10 Am. Jur., Champerty and

Maintenance, §3, p. 551 (1956) (Supp. p. 53 “add, following note

19” ) .

16 Chapter 35, Acts of Special Session, General Assembly of

Virginia, 1956, does not make, as essential elements of the crime

of barratry, stirring up (1) groundless suits (2) for one’s own

profit or for the purpose of vexing the defendant.

29

have become group-sponsored litigation—an American free

speech phenomenon.17

Group sponsorship of litigation is as indigenous to twen

tieth century America as group sponsorship of welfare and

charities. Groups which engage in such activity are too

numerous to mention individually. However, they may be

placed in the following general classifications: labor

unions,18 trade associations,19 consumer organizations,20

nationality groups,21 bar associations,22 racial groups,23

17 Cf. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88.

18 E.g., thg following publications describe cases in which labor

unions supplied counsel or funds for members involved in litiga

tion: _ See reprint of testimony of Walter Drew before Senate

Judiciary Committee (1914) in “The Crime of the Century and

Its Relation to Politics”, p. 24 (Nat’l Assn, of Manufacturers

publication); News You Don’t Get, August 11. 1936, April 27 and

May 5, 1938 (published by National Committee for the Defense of

Political Prisoners), pages unnumbered; Church, S. H., “Trade

Unionism and Crime,” New York Times, Oct. 1, 1922.

19 E.g., The National Erector’s Association retained Walter Drew

to represent it in litigation. See reprint referred to in note 17,

supra. It is virtually impossible to document the fact that trade

associations support litigation involving the applicability and con

stitutionality of laws affecting the trade since the reports of the

cases do not give such information. Brannon v. Stark, 185 F 2d

871 (D. C. Cir. 1950).

20 E.g., The Consumer’s League sponsored litigation involving

the constitutionality of social welfare legislation in the 1930’s.

Schlesinger, A. M., Crisis of the Old Order (1957) pp. 113 and 419.

21 E.g., between 1856 and 1875 the German Society provided a

special legal committee to protect newly arrived immigrants.

Smith, R. H., Justice and the Poor (1921) p. 134, American Com

mittee for the Defense of Puerto Rican Political Prisoners. News

You Don’t Get, May 7, 1935, pages unnumbered, op. eit., supra

ftn. 18. ’

22 E.g., The Atlanta Bar Association in the 1940’s sponsored liti

gation for persons who had been victims of unscrupulous money

loaning businesses. Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar Association, 191 Ga

366, 12 S. E. 2d 602 (1940).

23 See New York Times feature article “Champion of the Indian ”

March 3, 1958.

30

religious groups,24 labor defense committees,25 child welfare

organizations,26 civil liberties groups,27 property owners,28

tenants,29 professional groups,30 committees for protection

of immigrants,31 and hoc committees32.

It appears that no court in the United States has ever

denied the right of individual or group sponsorship of

litigation as involved here where there is no agreement to

share the proceeds and where the members of the group

have a common or general or patriotic interest in the

principle of law to be established. Indeed, the courts have

expressly upheld it. Brannon v. Stark, 185 P. 2d 871 (D. C.

Cir. 1950), aff’d 342 U. S. 451; Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar

Assn., 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E. 2d 602 (1940); Brush v. Car-

24 E.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses apparently sponsored a number of

cases in this Court, e.g., Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, and

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296. The Methodist Federa

tion for Social Service provided financial assistance in the Scotts-

boro case. News You Don’t Get, Jan. 3, 1936, pages unnumbered,

op. cit., supra, ftn. 18.

25 International Labor Defense sponsored cases as evidenced by

In re Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934).

26 E.g., The Children’s Aid Society of Boston, Smith R. H.,

Justice and the Poor (1921) p. 223.

27 E.g.,The American Civil Liberties Union. See the annual

reports of this organization for any year.

28 E.g., Opinions of the Committees on Professional Ethics of the

Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the New York

County Lawyers’ Association, Columbia Univ. Press, 1956, Op. No.

113. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24.

29 E.g., Shanks Village Committee Against Bent Increases v.

Cary, 103 F. Supp. 566 (S. D. N. Y. 1952).

30 E.g., Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

992 (4th Cir. 1940).

31 E.g., American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign

Born assisted Otto Richter, a German refugee seeking political

asylum. News You Don’t Get, Feb. 25, 1935, pages unnumbered,

op. cit., supra, ftn. 18.

32 E.g., Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee, Schlesinger, A. M.,

Crisis of the Old Order, 1957, p. 113.

31

bondale, 299 111. 144, 82 N. E. 252 (1907); Davies v. Stowell,

78 Wis. 334, 47 N. W. 370; Royal Oak Drain. Dist. v. Keefe,

87 F. 2d 786 (6tli Cir. 1937); Vita-phone Corp. v. Hutchison

Amusement Co., 28 F. Supp. 526 (D. Mass. 1939). In re

Ades, 6 F. Supp. 467 (D. Md. 1934).33 Moreover, a

species of such cooperative activity has been approved by

bar associations. The Committee on Professional Ethics

of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York

says: “A litigant may solicit the cooperation of persons

interested in the same question, or in establishing the

same principle of law; and such solicitation may properly

be done by his attorney, when it is primarily and funda

mentally in the interest of the client . . 34 And the same

committee says: “under proper circumstances and where

real interests are involved, lawyers may act for one party

where legal fees and other expenses are defrayed by

another.” 35

33 Brannon v. Stark, supra, upheld the right of certain handlers

of milk to finance the litigation of certain milk producers. Gunnels

v. Atlanta Bar Assn., supra, upheld the right of the Atlanta Bar

Association to furnish counsel for the litigation of those who had

been victims of the loan sharks. Brush v. Carhondale upheld the

right of a citizen to finance an appeal by the city in a test case.

Davis v. Stowell upheld the right of buyers of worthless stock

to prosecute a test ease brought by plaintiff to determine defen

dant’s case. Royal Oak Drain. Dist. v. Keefe upheld the right of

a bondholders’ protective committee to bring a class suit to deter

mine validity of bonds. Vitasphone Corp. v. Hutchison upheld the

maintenance of a copyright protection bureau by a group of movie

producers and distributors to protect their copyrights by bringing

suit where necessary. In re Ades upheld the right of a lawyer,

who had been employed by the International Labor Defense, a

group which sponsored litigation, to volunteer his services to

persons accused of crimes.

84 Opinions of the Committees on Professional Ethics of the

Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the New York

County Lawyers’ Association, Columbia University Press, 1956

Opinion No. 343. See also Nos. 113, 170, 281, 321, 363, and 586.

35 Id, Op. No. 707. In this instance the expense bearer was merely

interested in a final determination of the question of law as he

might have a similar case in the future.

32

The Canons of Professional Ethics of the American Bar

Association expressly recognize the activities of charitable

societies in paying the expenses of the litigation of others.

Canon 35. See also, Opinions of ABA Committee on Pro

fessional Ethics and Grievances, Opinion 148 (1935).

The development of the law has always been toward ex

panding the opportunities of litigants to present their cases

as fully and completely as justice may require and to avail

themselves of whatever assistance they need in their pre

sentation.36 There has been continued liberalization of rules

of procedure which has facilitated the development of

group sponsored litigation, e.g., rules permitting class

actions, intervention and permissive joinder. Recognizing

that large groups of people are often interested in a deter

mination of common questions of law and fact, the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure permit one member of the group

to sue on behalf of all.37 If Virginia fears that its courts

will become overburdened with frivolous contentions, it

has only to look to the admonition of this Court: “The ex

penses of litigation deter frivolous contentions. If numer

ous parallel cases are filed, the courts have ample authority

to stay useless litigation until the determination of a test

case.” Stark v. Wickard, 321 U. S. 288, 310.

Virginia now seeks to reverse this trend by prohibiting

certain activity with respect to the conduct of litigation

which is the antithesis of this development and which has

the singular effect, in the circumstances of this case, of

divesting indigent Negro litigants of their only means of

3( Brownell, Emery, Legal Aid in the United States (1951);

Smith, R. H., Justice and the Poor (1921).

37 Rule 23(a) (3) F. R. C. P. See also Opinions of the Committee

on Professional Ethics, etc., op. cit., supra, ftn. 35, Op. No. 113

where the Bar Association’s Committee on Professional Ethics

affirmed the right of an attorney to ask each member of the group

to contribute to the payment of his fee.

access to the courts. Virginia can hardly claim that this

anomaly constitutes due process in that it merely codifies

existing law or custom of the bar.

Virginia’s real purpose in prohibiting contributions to

litigation is not to safeguard the administration of justice,

but to erect an economic barrier to the courts on questions

of racial discrimination. The exemptions contained in

Chapter 35 support this assertion.

E. D enial o f E qual P ro tec tion .

The Virginia legislature, recognizing the sweep of these