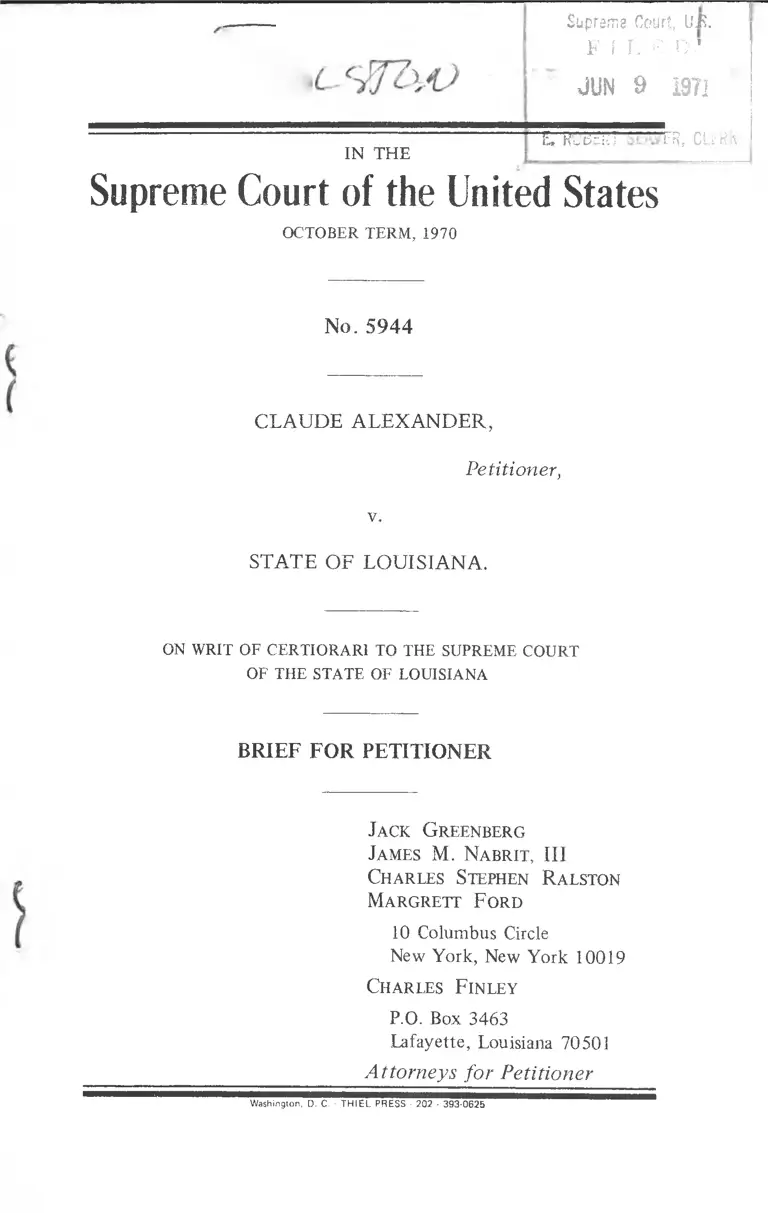

Alexander v. Louisiana Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

June 9, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Louisiana Brief for Petitioner, 1971. d9266d6d-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6bf14a26-9bf5-42c0-b8b0-57e96de36c9f/alexander-v-louisiana-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court, UE.

F 1 L £ IV

vlUN 9 197!

IN THE

E, RuteKl l R, CL.f R \

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

N o .5944

CLAUDE ALEXANDER,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF LOUISIANA.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Margrett F ord

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles F inley

P.O. Box 3463

Lafayette, Louisiana 70501

Attorneys for Petitioner

Washington. D. C. - T H IE L P R E S S • 202 - 393-0625

(i)

INDEX

Page

Opinion Below .............................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction . ............ .................................................................. 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved ............ .. 3

Questions Presented............ .. ......................................................... 4

Statement of the C ase ..................................................................... 5

Summary of Argument .................................................... .. 12

Argument:

I. PETITIONER WAS DENIED EQUAL PROTECTION

OF THE LAW IN THAT NEGROES WERE SYSTEM

ATICALLY EXCLUDED FROM THE GRAND JURY

THAT INDICTED HIM ...................................................... 13

A. Petitioner Made Out a Prima Facie Showing of

Racial Discrimination in the Selection of the

Grand Jury that Indicted Him . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

B. The Evidence Established that There Was an

“Opportunity for Discrimination” in Violation

of Whitus v. Georgia and Avery v. Georgia.................... 19

II. THE TOTAL EXCLUSION OF WOMEN FROM JURIES

IN LAFAYETTE PARISH DEPRIVED THE PETITIONER

OF A JURY REPRESENTING A CROSS-SECTION OF

THE COMMUNITY IN VIOLATION OF THE DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT . ............................................................................. .. . 22

A. This Case, Unlike Hoyt, Involves the Total Exclusion

of Women from Juries........................................................ 23

B. The Total Exclusion of Women Violates the Require

ment of Representative Juries Imposed by the Due

Process Clause..................................................................... 25

III. THE INTRODUCTION OF PETITIONER’S ALLEGED

CONFESSION VIOLATED HIS RIGHTS TO DUE

PROCESS OF LAW............................... 30

CONCLUSION ............................................ 34

Page

APPENDIX

1. Statutes of Louisiana Relating to Jury Selection............... la

2. Portion of Decision of Supreme Court of Louisiana

in State o f Louisiana v. Pratt, 255 La. 919, 233 So.2d

883 (1970), Dealing with Jury Selection.............................. 9a

CASES

Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206 (1 9 6 8 )............... ................... 20

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) .............................. 19, 20, 21

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946)........................... 25, 26

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1968) ......................... 20

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396 U.S. 320

(1970) ......................................................... ........................15, 25, 26

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967)................................ 31, 33

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) .............................. 13

Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1941) .............................. 25

Harris v. New York, 401 U.S.___ , 28 L.Ed.2d 1 (1971) ____13, 31

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) ............................................. 22

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1 9 6 1 ) ..........................................passim

Jones v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967).......................................... 15, 20

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966) ......................... 25

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ................................ passim

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935)....................................... 15

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1 9 4 7 ) ............................... .. 15

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971)............... 29

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) .............................. 28

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ..................................... 15, 20

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940)............................................ 25

State of Louisiana v. Pratt, 255 La. 919, 233 So.2d 883

(1970) ................................................................................... 1,4, 11

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1 9 4 6 ) .................... 25

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1 9 7 0 ).............................. 14, 15, 16

Page

Walder v. United States, 347 U.S. 62 (1954) ........................... 31, 33

White v. Crook, 251 F.Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1 9 6 6 )................. 27, 29

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)..................................... passim

STATUTES

Ala. Code 1940, Tit. 30, § 21 ........................................................... 27

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 40.01 (1) .............................. 23 28

Idaho Code § 2-411........................................................... 28

Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure § 402 ................. 2 6 22 23

Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure § 408 .............................. 2, 5

Minnesota Stat. Ann. § 593.02 ............................................... 28

Mississippi Code 1942 Ann. § 1762 ...................... ..................... 27

New Hampshire Rev. Stat. Ann. 1955, § 500:1 ......................... 28

North Dakota Cent. Code § 27-09-04 ........................... ................ 28

South Carolina Code 1962, § 38-52 ............................................ 27

Virginia Code § 8-178(30)................. .............................................. 2g

Washington Rev. Code § 2.36.080 ................................................. 28

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Finklestein, The Application o f Statistical Decision Theory

to the Jury Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 338

(1966) ......................................................................................... 16, 17

Moroney, Facts from Figures (3rd and Revised Edition,

Baltimore, Md., 1965, Penguin Books - Pelican) .................... 17

National Bureau of Standards Handbook of Mathematical

Functions (National Bureau of Standards, Applied Mathe

matics Series, No. 55, June 1964) U.S. Govt. Printing

Office ............... t o

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No. 5944

CLAUDE ALEXANDER,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF LOUISIANA.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Louisiana is reported

at 255 La. 941, 233 So.2d 891, and is set out in the Appendix

(A. 170-180).1

*In a companion case, State o f Louisiana v. Pratt, 255 La. 919,

233 So.2d 883 (1970), the Supreme Court of Louisiana decided issues

relating to jury discrimination common to both cases. The relevant

parts of the Pratt decision have been set out in the Appendix to this

Brief (B. A. 9aT5a).

2

JURISDICTION

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Louisiana was entered

on March 30, 1970 and a motion for rehearing was denied

May 4, 1970 (A. 181). An extension of time for filing a

petition for writ of certiorari was granted by Mr. Justice

Black to and including September 29, 1970. The petition

for writ of certiorari and a motion for leave to proceed in

forma pauperis were filed on September 29, 1970, and were

granted on March 1, 1971 (A. 181).

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here the deprivation of rights, privileges and immu

nities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves sections 401-404, 408, 410-411,

413-417, and 419 of the Louisiana Code of Criminal Pro

cedure, the texts of which are set out in the Appendix to

this brief (B.A. la-9a).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Was petitioner, who is a Negro, denied due process

and equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment by being indicted by a grand jury

chosen from a venire from which Negro citizens were sys

tematically excluded in violation of Whitus v. Georgia, 385

U.S. 545?

2. Was petitioner denied due process of law as guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment by being indicted by a grand

jury chosen from a venire from which women had been

systematically excluded?

3. Was petitioner denied due process of law as guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment where at trial a statement

3

was introduced, for impeachment purposes, that he allegedly

had given to police officers shortly after his arrest and where

the testimony of the police officer established that petitioner

was not advised that he had the right to have a lawyer

present at the time he gave any statement and that petitioner

had not affirmatively waived his right to remain silent?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner, Claude Alexander, is under a sentence of life

imprisonment imposed by the District Court for the Fif

teenth Judicial District in Lafayette Parish, Louisiana, follow

ing his conviction for rape. His conviction was affirmed on

appeal by the Supreme Court of Louisiana (A. 170).

Prior to trial petitioner filed motions to quash the indict

ment on the grounds that: (1) citizens of the female sex

were systematically excluded from the grand jury list and

venire and from the grand jury empaneled; and (2) citizens

of the Negro race were included in the grand jury list, and

grand jury venire, in such small numbers as to constitute

only a token representation having no relationship to the

number of Negroes in the general population in the Parish

of Lafayette and in the Fifteenth Judicial District. There

fore, the indictment against him was invalid and illegal

because it was returned by a grand jury empaneled from a

grand jury venire made up contrary to the provisions of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States of America (A. 6).

\J 4

1. Facts Relating to Racial Discrimination in the

Composition of the Jury.

Prior to trial a hearing was held on petitioner’s motion

to quash the indictment.2 The evidence revealed that the

jury commission was appointed by the court and consisted

of five members (all of whom were white (A. 50)), includ

ing the clerk of the court of Lafayette Parish. The com

mission had selected a list of 400 prospective jurors to

serve for the terms in which petitioner was indicted. Of

these 400 prospective jurors 27 were Negroes, or 6.75%,

and the race of 5 persons was unknown.3 From this list

20 names were drawn, one of which was that of a Negro.

From these 20, twelve, none of whom were Negro, com

prised the actual grand jury that indicted petitioner (A. 3-

4, 16-24, 39).4 Petitioner’s challenge to the grand jury

centers on the manner in which the commissioners selected

the 400 prospective jurors from which his grand jury was

drawn.

2 A. 29-65. The hearing was held jointly in the cases of petitioner

and his co-defendant, Lee Perry Pratt. The Supreme Court of Louis

iana decided the jury discrimination issues in Pratt’s appeal. The rele

vant portions of that decision, State o f Louisiana v. Pratt, 255 La.

919, 233 So.2d 883 (1970), are set out in the Appendix to this

Brief.

3It should be noted that there are inconsistencies in the record as

to the number of Blacks and of persons whose race is unknown out

of the total of 400 persons. The State introduced as an exhibit a

certification by the clerk of the court stating that there were 25

Negroes (or 6.25%) and 4 persons with no race shown (A. 15). A

count of the actual list of jurors, however, (A. 16-24) shows 27

Negroes and 5 persons with no race. In this brief, however, the 27-5

figures will be relied on as establishing a prima facie case of racial dis

crimination.

4These figures were obtained from the testimony of the registrar

of voters (A. 39) and by comparing the lists of the grand jury venire

and the actual grand jury (A. 3-4) with the overall jury list (A. lb-

24).

5

According to United States Census reports for 1960

(which were admitted into evidence below), the total num

ber of persons in Lafayette Parish over 21 years of age and

hence eligible for service on juries was 44,986. Thirty-five

thousand, five hundred and thirteen were white and 9,473,

or 21.06%, were black. Of these totals, the male popula

tion, the only group considered for jury service (see part 2,

infra), consisted of 21,736 persons. Of this number, 17,331

were white and 4,405, or 20.27%, were Black.

The evidence as to the method used by the jury commis

sioners in compiling the grand jury lists was as follows: A

list of names was obtained from several different sources,

including the Lafayette City telephone directory, the city

directory, the registrar of voters registration list, lists sub

mitted by the parish school board or any list the commis

sioners could find, including recommendations made by the

jury commissioners themselves (A. 35, 37). A question

naire was mailed out to persons on the list to determine

whether or not the individual was qualified to be consid

ered as a candidate for the general venire list (A. 40-41).

As a result of this process, the commissioners obtained

7,374 questionnaires, 1,015 of which, or 13.76%, were

from Negroes (A. 15).s On each questionnaire there was

given the race of the individual involved (A. 8, 51). A

card was then made up on each person for whom there was

a questionnaire and was attached to the questionnaire (A.

36). Each card also designated the race of the prospective

juror (see A. 7, 51). Finally, a white slip of paper contain

ing only the name and address of the person was attached

to the questionnaire and the card (A. 55-58).

At this point, the commissioners were ready to select

four hundred6 names to place in the box from which to

5 One hundred and eighty-nine questionnaires had no racial desig

nation (A. 15).

6Article 408, La. Code of Criminal Procedure, requires that at

least three hundred names be drawn. The clerk testified, however,

that four hundred were drawn in this case (A. 44).

6

draw grand jury venires of twenty names each. For each

person they had a set of papers consisting of a question

naire, a card and a slip of paper. On the first two, the

race of the person was designated. The clerk testified that

the commission worked from about 2000 of the sets which

were placed on a table.7 Sets were picked up, purportedly

at random; the white slip of paper was removed and put in

to the box (A. 43, 48, 55-58).

At the end of this procedure the jury commission had

selected four hundred names, 27 of which, or only 6.75%,

were those of Blacks. For the purpose of selecting the

grand jury that indicted petitioner twenty slips of paper

were pulled from the box, one of which was that of a Negro

(ii . e 5% of the names were Negro). The lone Negro was

not drawn to serve on the twelve-man grand jury. Thus,

the grand jury that actually indicted petitioner included no

Negroes at all. The clerk testified that no consideration was

given to race during the selection procedure (A. 34, 35, 41,

45, 47-48, 54-57, 59). However, it was admitted that the

documents used to select the venire contained racial desig

nations, that the designation was referred to on occasion

for identification purposes, and that the commissioners

could have noticed the race of the persons during the

selection process (A. 48, 51-52, 58-59).

2. The Facts Relating to the Exclusion

of Women from the Jury Rolls.

The evidence established that women were totally

excluded from juries in Lafayette Parish because of the

operation of Article 402, La. Code of Criminal Procedure,

which prohibits the selection of a woman unless she has

filed a written declaration of her desire to serve (A. 32-33).

7 After the questionnaires and cards were made up, they were re

viewed and persons not qualified or exempted under the law were ex

cluded (A. 52, 54-55).

7

The clerk of the jury commission testified that question

naires were deliberately not sent to women (A. 35-36).

Only preliminary efforts had been made to encourage wo

men to declare their desire to serve.8

8The clerk of court (who is also a member of the jury commis

sion) testified as follows:

Q. Did you act as a member of jury commission in draw

ing up a grand jury venire which made its return in the first

week or two of September of this year?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. That would be the same grand jury that returned an in

dictment against Claude Alexander, do you know that, sir?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Yes, Mr. LeBlanc, are you familiar with the procedures

followed by the Jury Commission in drawing up the venire

of three hundred names for the grand jury?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you participated in that procedure?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. In drawing up the list of three hundred names, were any

citizens of the female sex included?

A. No.

Q. In fact, all women were excluded, isn’t that right?

A. We didn’t have any names submitted to us of any with

the intention of willing to serve.

Q. And you didn’t look for any names of women to serve

on the jury, the grand jury?

A. That’s right.

Q. And none were listed on the grand jury venire.

A. That right. (A. 32)

* * * * *

Q. Mr. LeBlanc, you would include the names of any women

who volunteered service. Is that correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And as I understand, the reason you did not include

women is because they are exempt from service unless they

specifically volunteer and offer their service. Is that right?

A. Yes (A. 53).

* * * * *

8

According to the United States Census Report for 1960,

the total number of women in Lafayette Parish over 21

years of age and hence eligible for service on juries over

23,250, with 5,068, 21.8%, being Black. By excluding

women, therefore, more than 50% of the persons eligible

to serve were automatically kept off juries. The jury list,

the grand jury venire and the grand jury that indicted peti

tioner contained no women at all.

3. The Facts Relating to the Admissibility

of Petitioner’s Confession.

At the trial the prosecutrix and her boyfriend identified

petitioner as one of the men who had committed the assault

and rape. Policemen who came upon the scene similarly

identified him as the person they had apprehended as he

tried to flee. Petitioner took the stand and testified in his

own defense. His story was that he had been in the park

on his way to burglarize a club on the premises. As he was

walking along, at about 1:30 A.M., he heard moans. He

investigated and saw a white girl, nearly nude, at the bot

tom of a culvert. He went into the culvert, looked at the

girl and started back out to go get help. At this instant, a

light was shone in his face and he was arrested by police

officers.

When petitioner had finished his direct testimony, the

prosecutor announced that he would introduce a statement

Q. Were any invitations or notices sent to women advising

that they had a right to declare their desire to serve on the

jury?

A. I’ve discussed that with the Assistant District Attorney

and I’ve sent her at different women’s clubs to explain to

the women the possibility of being on the jury. The reason

so far that the women have not served is because facilities

and accommodations for ladies were not available in the old

courthouse. But since the new place is being constructed

we’re working on the women to submit names and intention

to serve (A. 54).

9

allegedly given to police officers immediately after peti

tioner’s arrest. The jury was excused, and a hearing was

held before the judge to determine the admissibility of the

alleged confession (A. 65-67). The testimony o f the offi

cers was that one o f them advised petitioner that he had

the right to remain silent, that anything he said could be

used against him in court, that he was entitled to an attor

ney, that if he couldn’t afford an attorney one would be

offered to him, and also that he had the right to stop talk

ing at anytime he felt like it (A. 70, 74, 85, 100-101). In

response to a question by petitioner’s counsel, however, the

officer testified positively that petitioner had not been

informed that an attorney would be appointed to be pres

ent at the time he gave a statement (A. 157-158).9 Further,

two of the officers testified positively that petitioner made

no response to the warning given him. Rather, the inter

rogating officer testified that he just began asking questions

and petitioner responded to them (A. 78-79, 90, 92).10

Q. Captain, you did tell this man, did you, that he had a

right to be advised by an attorney?

A. I advised him that he had a right to a lawyer.

Q. And that he had a right to have an attorney present

when the statement was taken?

A. No, sir.

Q. You didn’t tell him that?

A. No, sir (A. 157-158).

10 Thus:

Q. Capt. Picard, you said that you told him something about

his right to remain silent?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And did he remain quiet and gave you no answer when

you told him that?

A. Not during that saying, no, sir.

* * * * *

A. After I advised him of his rights I said, “What happened

in the park?” , and he told me.

* * * * *

Q. But he didn’t tell you that yes, he would agree to talk

did he?

10

The questioning took place in the detective’s office at the

city police station at 2:30 A.M., immediately after peti

tioner’s arrest (A. 67-68). The petitioner and three police

officers were the only persons present. One officer asked

questions, took notes of petitioner’s answers (A. 93), and

then reduced the alleged oral statement to writing (A. 68).

The notes were then discarded (A. 95).

Petitioner testified that at the time of his arrest he had

been handled roughly by the officers (A. 110-111). He

further testified that he was refused the use of a telephone

to call his mother at the time of the interrogation (A. 111-

112), and that he told the interrogating officers that he

was sleepy (A. 112-114). These allegations were denied by

the officers.

All the witnesses testified that petitioner refused to sign

the statement when the interrogating officer read it to him.

The officers testified that the reason he gave was that he

wouldn’t sign it until he got his shoes back (A.- 71, 73, 88).

Petitioner testified, however, that it was because he hadn’t

said the things that were in the statement (A. 116, 117-

119). In any event, the only signature on the statement

from which the interrogating officer testified was that of

the officer (A. 152).

The trial judge overruled petitioner’s objections to the

introduction of the purported confession, holding that it

had been made voluntarily and that the proper Miranda

warnings had been given (A. 123-126). The jury was re-

A. No, he just started talking.* * * * *

Q. He just kept silent. Is that right, sir?

A. He kept silent until he told me what happened in the

park.* * * * *

Q. He said nothing to show you the state of his mind in

response to your warnings until he began to say what occur

red in the park, isn’t that right, sir?

A. No, sir. (A. 78-79; see also A. 158.)

called, and the interrogating officer was permitted to tes

tify as to the statement. It was an admission of the crime

and directly contradicted the story petitioner had given

on the witness stand.11

4. Proceedings in the Courts Below.

As stated above, petitioner raised his constitutional

objections to the jury selection procedures by motion prior

to trial and objected at trial to the introduction of his

alleged confession. As to the jury claims the trial court

denied the motion to quash, relying on Louisiana and federal

court decisions dealing with racial exclusion and on this

Court’s decision in Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57, dealing

with the exclusion of women from juries (A. 26). With

regard to the introduction o f the confession, the court

held: (1) the confession was voluntary; and (2) there had

been compliance with Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436.

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Louisiana, in the com

panion case o f State v. Pratt, 255 La. 919, 233 So.2d

883 (1970) (B.A. 9a) rejected both challenges to the grand

jury venire (A. 172-174). The court held that purposeful

exclusion of Negroes had not been shown, and also relied

on Hoyt v. Florida to uphold the exclusion of women.

With regard to the confession issue, the Supreme Court

accepted the factual determination of the trial judge (A.

179). A rehearing was denied (A. 181), and a writ of

certiorari was sought here.

Petitioner also testified that the morning after his arrest he had

given another statement to a detective that was substantially the same

as the testimony he gave at the trial (A. 137-138).

1Aj \ aJL'xJ

12

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

Petitioner made out a prima facie case of racial discrimi

nation in the selection of the venire from which the grand

jury that indicted him was chosen. Although adult Negro

males compose 20.27% of the population of Lafayette

Parish, they represented only 6.75% of the jury venire of

four hundred persons. The jury commissioners claimed that

the four hundred persons were selected at random from a

pool that was 13.76% black. However, statistical analysis

demonstrates that it was improbable in the extreme that

the reduction in the percentage of blacks could have resulted

from random selection methods.

No explanation was given for these disparities, except for

denials that race was considered when the venire was

selected. However, at critical stages in the selection process

the jury commission had a clear opportunity to discriminate,

since the documents they worked with designated the race

of the persons being considered for jury duty. Therefore,

the grand jury was empaneled in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

II

By operation of a Louisiana statute that excludes all

women from jury duty unless they volunteer for service,

no women whatsoever were on the jury rolls. This result

largely was caused by the jury commission’s deliberately

not sending jury questionnaires to women during the proc

ess by which they developed a pool of names to be consid

ered for service. Thus, this case is distinguishable from

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961), relied on by courts

below, since the affirmative action of the commission was

responsible for the total absence of women from the rolls.

In contrast, there were at least some women on the rolls in

Hoyt.

13

The total exclusion of women from jury service denied

petitioner his right to a jury venire reasonably representa

tive of a cross-section of the community as a whole. Louis

iana has offered no valid justification for the use of a

scheme that has had the totally exclusionary effect shown

here. Therefore, the indictment of petitioner violated his

right to due process of law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Ill

At petitioner’s trial, an alleged confession was introduced

by the state for impeachment purposes that was obtained

without compliance with Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436

(1966). This case is distinguishable from Harris v. New

York, 401 U.S. ___ , 28 L.Ed.2d 1 (1971), in that the cir

cumstances surrounding the giving of the confession raise

serious doubt as to its reliability. Harris should be limited

to those cases where the confession involved is of the same

order of reliability as physical evidence that has been seized

in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Therefore, peti

tioner was denied his right to due process by the introduc

tion of the confession against him.

ARGUMENT

I

PETITIONER WAS DENIED EQUAL PROTECTION OF

THE LAW IN THAT NEGROES WERE SYSTEMATICALLY

EXCLUDED FROM THE GRAND JURY THAT INDICTED

HIM.

At the time of the indictment of petitioner the grand

jury list and venire for Lafayette Parish, Louisiana was

made up from various lists secured by the jury commis

sioners (A. 35-36).12 A questionnaire was mailed out to

12In this case, only the grand jury was challenged. Thus, this case

is like, e.g., Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958).

14

every eighth person on the list thus compiled by the jury

commission (A. 40-41).13 The race of the individual was

listed on the questionnaire (A. 8). When the questionnaires

were returned, the commissioners determined which per

sons were qualified for jury service. For each such person

a card was made out which also designated race (A. 7) and

the card was attached to the questionnaire. Slips of paper

on which were written only the name and address of the

individual were then attached to the questionnaire and

card. Sets of questionnaires, cards and slips were picked

until 400 names were chosen. The slips of paper alone

were then deposited in the general venire box from which

jury venires were drawn.

At the beginning of this process the jury commission had

started with an eligible male population that was 20.27%

black. They received back 7,374 questionnaires, 1,015 of

which, or 13.76%, were from Negroes.14 From these ques

tionnaires they picked a jury venire of 400 names, 27 of

which, or only 6.75% were black,15 and finished with a

20-man venire containing only one black. The twelve men

on the grand jury that actually indicted petitioner were all

white.

A. Petitioner Made Out a Prima Facie Showing of

Racial Discrimination in the Selection of the

Grand Jury that Indicted Him.

This Court has long held that where statistically signi-

cant disparities between the percentage of Negroes eligible

to serve on juries and the percentage on jury rolls has been

shown, a prima facie case of racial discrimination has been

made. Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 359 (1970); Sims

13If the eighth person was exempt by law from jury service, how

ever, then the next eligible individual was selected (A. 35-36).

14One Hundred and Eighty Nine had no racial designation (A. 15).

15Five of the 400 were unidentifiable as to race.

15

v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967); Jones v. Georgia, 389 U.S.

24 (1967); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967); Patton

v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947); Norris v. Alabama, 294

U.S. 587 (1935). Once such a showing has been made, the

state has a heavy burden of rebuttal, which may not be

satisfied by testimony, as here (A. 34; 35; 41; 45; 47-48;

54-57; 59), of jury officials that they did not include or

exclude any one because of race. See, Turner v. Fouche,

396 U.S. at 361, and cases cited there at n. 21.

Petitioner here made such a showing. Lafayette Parish

has a population of 20.27% black males. Only 13.76% of

the names of persons obtained by the commission by use of

questionnaires were black. The actual jury list compiled

from these questionnaires and from which the grand jury

was drawn contained only 6.75% black names. And even

if the five persons whose race was not known are assumed

to have been Negro, the percentage was still only 8%.

The state has simply failed to provide any adequate rea

son for these results. With regard to the disparity between

the percentage of blacks in the parish and the percentage

of blacks among those returning questionnaires, the clerk

of the commission testified that he was aware of the fact

that there had been a lower rate of response from Negroes.

Indeed, he admitted that because of the sources of names

that were used, “naturally there was a greater percentage

of personal mail to the white people than to the Negroes.

And for that reason it follows that we had larger replies

from the white than from the colored” (A. 45-46). Thus,

it was clearly established that the commission had failed in

its constitutional duty to utilize methods that would result

in a jury list . . ‘truly representative of the commu

nity,’ “ as required by Carter v. Greene County, 396 U.S.

320, 330 (1970), and by Turner.

Even more serious, and as equally lacking in a constitu

tionally acceptable explanation, is the large drop from

13.76% blacks returning questionnaires and 6.75% blacks

on the actual jury list. The clerk testified that the more

16

than 7,000 returned questionnaires were examined to deter

mine who among the returnees were eligible for service until

about 2000 were left (A. 52; 54-55). No evidence was

offered by the state as to the racial breakdown of those

excluded, so it is not known whether the remaining ques

tionnaires reflected the same 86.24% white - 13.16% black

ratio as did the total number of questionnaires. It is clear

from Turner, however, that the burden was on the state to

justify and explain any drop in the percentage of blacks

resulting from this weeding out process, if any in fact did

take place. 396 U.S. at 359-361.

The two thousand or so questionnaires that were left

were then placed on a table, and 400 were picked. Of

these, only 27 were blacks, and for five the race was not

known. The selection procedure was purportedly a ran

dom one (A. 55-58). Petitioner urges, however, that by

the use of accepted methods of statistical analysis it can be

shown that the chances of this result being obtained by a

random system are so small as to lead irresistibly to the

conclusion that random methods were not used in fact.16

The approach to be used is that described at length in

Finkelstein, The Application o f Statistical Decision Theory

to the Jury Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 338

(1966), referred to by Mr. Justice Clark, writing for the

Court in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552, note 2.

In that article, Finkelstein suggests an approach to jury dis

crimination cases more exact than simply attempting to

infer discrimination from what appear to be significant dis

parities between percentages of Negroes in the general pop

ulation and in jury lists, the intuitive approach typically

used. He points out that statistical analysis provides a

ready tool by which courts can determine the probability

16The argument that follows is based on the assumption that the

proportion of blacks in the 2000 questionnaires used for selection

was the same as that in the 7,434 received, i.e., 13.76%. As noted

above, if the percentage was significantly less than that, the state

failed in its burden to explain any disparity.

17

of particular numbers of blacks being on lists if a random

method of jury selection was indeed used. If the probabil

ity in a particular case is significantly small, then it can be

concluded that the selection process was not random. Thus,

in the absence of an alternative explanation of why the

number of Negroes is small, it can be inferred that race

was a factor in choosing the jury. In his conclusion, Finle-

stein points out:

A basic legal principle in the jury discrimination

cases is that the selection of an improbably small

number of Negroes is evidence of discrimination . . .

The second legal principle controlling these cases

is that a disparity between the proportion of Negroes

on venires and in the population generally is evi

dence of the improbability of random selection. 80

Harv. L. Rev. at 374.

In his article Finkelstein demonstrates how a number of

methods can be used to calculate these probabilities. Here,

we will use a simplified version of the chi-square method

he describes at 80 Harv. L. Rev. at 365-373. The method

and formula used are explained in Moroney, Facts from

Figures, a book explaining statistical method and written

for laymen without mathematical training.17 This method,

it should be noted, is a conservative one—that is, it approxi

mates the highest possible probability of the particular

result coming about by chance. As will be noted, the actual

probability is much lower.

Turning to the facts in the present case, the first step in

the calculation is to ascertain the number of blacks that

would have appeared on the final jury list of 400 people if

the proportion was the same as for the questionnaires. Since

this was 13.76%, there would have been 55.04 blacks rather

than only 27. What, then, is the probability that 27 or

173rd and Revised Edition, Baltimore, Md., 1965 (Penguin Books-

Pelican), Ch. 15, pp. 246-270. The formula can be found on page

250. A copy of this book has been deposited with the Clerk for the

convenience of the Court.

18

fewer Negroes would appear on the list if the selection were

random as claimed by the jury clerk? The chi-square for

mula, explained in detail in the margin below,18 shows

18The steps in the computation were as follows:

1. The formula used was:

chi-square = (Aw - Ew)2 + (An - En)2

Ew En

2. The arithmetic values were as follows:

Actual (A) Expected (E)

White (w) 373 (Aw) 344.96 (Ew)

Negro (n) 27 (An) 55.04 (En)

Total 400 400.00 .

(As noted above, the “expected” figures given above merely reflect

the relative percentages of Negroes and whites among the question

naires, i.e., total jurors times percentage of Negroes among question

naires equals expected Negro jurors, or 400 x 13.76% = 55.04.)

Applying the formula, thus:

chi-square = (373 - 344.96)2 + (27 - 55.04)2

344.96 55.04

= (28.04)2 + (-28.04)2

344.96 55.04

= 786.24 + 786.24

344.96 55.04

= 2.279 + 14.285

chi-square = 16.564

4. To translate the chi-square numbers to determine probability

we used the table published in the National Bureau of Standards

Handbook of Mathematical Functions (National Bureau of Standards,

Applied Mathematics Series, No. 55, June 1964, Govt. Printing Office,

p. 982.) For a chi-square number of 16.564, the probability is five

in 100,000, or .00005.

19

that that probability is at best only .00005, or five in

100,000.19 Stated another way, the probability is that

this result would obtain only once in 20,000 random selec

tions.20

Thus, it has been established that, because of the num

ber of Negroes selected, the probability that the four hun

dred names were selected at random, as claimed by the

state, is so low as to render that claim inherently suspect.

The disparity shown, as the Court said in Whitus, “strongly

points” to the conclusion that race was considered by the

jury commissioners. 385 U.S. at 551. As will now be

shown, the commissioners had a clear opportunity to uti

lize racial considerations.

B. The Evidence Established That There Was an

“Opportunity for Discrimination” in Violation

of Whitus v. Georgia and Avery v. Georgia.

In Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967), and Avery v.

Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953), this Court dealt with a com

bination of a disparity between blacks eligible for jury duty

and blacks on the jury rolls and of what it termed an “oppor

tunity for discrimination” by those involved in the jury

selection process. 385 U.S. at 552. In Avery, different

colored tickets were used for white and Negro prospective

19 Dr. John de Cani, a professor of statistics at the University of

Pennsylvania has calculated the exact probability as being only

.0000043, or less than 5 in one million. Thus, it may be noted, is

less than the probability noted by Mr. Justice Clark in Whitus, which

was .000006, or six in one million. 385 U.S. at 552, no. 2.

20Even if it is assumed that all five of the persons whose race was

unknown were black, the probability is only three in ten thousand.

(.0003). The relevant figures under this assumption are Aw=368, An=32,

Ew=344.96, En=55.04, chi-square=l 1.184. And if the five unknowns

are excluded altogether, the probability is five in one hundred thou

sand. (.00005). (Aw=368, An=27, Ew=340.65, En=54.35, total

jurors=395, chi-square= 15.959.)

20

jurors. In Whitus, names of prospective jurors were selected

from tax digests segregated according to race. See also

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1968); Jones v.

Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967); Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S.

404, 407-08 (1967); Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206

(1968). In both instances, convictions were reversed

because of the danger of abuse inherent in a system where

the race of jurors could be known at critical stages in the

jury selection process.

This case presents facts indistinguishable from Whitus

and A very. A significant statistical disparity has been shown

above, and an opportunity to discriminate was present at

at least two stages in the process. As has already been

noted, race was requested on the questionnaires sent out to

all prospective jurors; the inquiry was answered in all but

189 of 7,374 of the returned questionnaires (A. 15). A

card was filled out for each juror which also contained a

racial designation. The questionnaire and card were attached

together and were used in the process by which the possi

ble percentage of Negroes to be included in the jury rolls

was reduced from 13.76% to 6.75%.

Thus, the questionnaires were used to reduce the num

ber of possible jurors from 7,374 to about 2000. The

questionnaires and cards were also used to select from that

2000 the 400 names that would be put into the venire

box. The only justification given for the racial designation

was that it was used, on occasion, for the purpose of iden

tifying the individual who had sent back the questionnaire

(A. 51). No explanation was given, however, as to why

the race of the person had any relevance in determining his

qualifications to serve. Moreover, it was admitted that the

commissioners had the opportunity to look at the question-

21

naires and notice the race of the person in question (A.

58).21

Thus, this case presents precisely the situation that

obtained in Avery and Whitus. There was a significant dis

parity between eligible Negroes and those ultimately placed

on the jury rolls that was unexplained by the State except

for general statements that the commissioners did not take

race into account. There was a clear opportunity to dis

criminate because prospective jurors were identifiable as to

race at critical stages in the selection process. Just as in

Whitus, it cannot be said “on this record that [the oppor

tunity to discriminate] was not resorted to by the commis

sioners.” 385 U.S. at 552.

In summarizing petitioner’s contentions concerning racial

discrimination in the selection of the grand jury venire, we

wish to re-emphasize the cumulative effect of the jury selec

tion process detailed above. The commissioners began with

an adult male population that was 20.27% black. If the

final venire of four hundred persons had reflected this pro

portion, it would have contained 81 Negroes and 319 whites

instead of the actual 27 Negroes and 373 whites. However,

the commission developed a basic pool that was only 13.76%

black (6359 whites, 1015 Negroes) by the use of methods

that they knew were likely to elicit a smaller proportion of

black than white responses. Even so, a 13.76% figure for

the venire would produce 55 black persons and 345 whites.

The wide divergence from these figures indicates, as shown

above, that a random method of selection was not used.

At two crucial steps in the process, when the question

naires were reduced to two thousand and when the final

selection of the four hundred names was made, there was

21 Significantly, the clerk agreed that the proof of whether race

was considered would be “how many colored or how many white are

actually included in the four hundred selected from the two thou

sand” (A. 58).

22

the clear opportunity to discriminate condemned by this

Court, because racial designations appeared on the forms

used by the commission. The net result was that only 27

Negroes were on the grand jury venire of 400 persons.

When 20 names were drawn in order to constitute the

actual grand jury that indicted petitioner, only one person

was black and he was not picked to serve on the twelve-

man jury. Thus, by a consistent process of progressive and

disproportionate reduction of the number of blacks, the

ultimate result was reached—an all-white grand jury that

returned the indictment challenged here. Because of racial

discrimination in the selection of the grand jury, the indict

ment must be quashed and the conviction based on it

vacated, Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942).

II

THE TOTAL EXCLUSION OF WOMEN FROM JURIES IN

LAFAYETTE PARISH DEPRIVED THE PETITIONER OF

A JURY REPRESENTING A CROSS-SECTION OF THE

COMMUNITY IN VIOLATION OF THE DUE PROCESS

CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

It is clear in this case that there were no women on the

jury rolls in Lafayette Parish. The clerk of the jury com

mission testified that this was because of the effect of Arti

cle 402, La. Code of Criminal Procedure, on the manner in

which the commission proceeded to obtain names of pros

pective jurors. That section expressly excludes all women

except for those who had previously filed a declaration

stating their desire to serve.

The clerk testified that in selecting names of persons to

whom questionnaires were to be sent, the names o f women

were deliberately passed over. Moreover, only preliminary

efforts had been made to encourage women to volunteer

to serve.

According to the United States Census Report for 1960,

the total number of women in Lafayette Parish over 21

23

years of age, and hence otherwise eligible for service on

juries, was 23,250, with 5,068 being black. Since the total

population of the Parish over 21 was 44,986, therefore,

51.7% of the persons eligible to serve were automatically

kept off juries by the exclusion of women.

Both the trial court and the Supreme Court of Louisiana

relied on the decision of this Court in H oyt v. Florida, 368

U.S. 57 (1961), in upholding this result, the latter saying that

“ [i] t is well settled that the fact that women do no appear

on a general venire list for jury duty furnishes no cause for

quashing an indictment in view of Article 402 of the Code

of Criminal Procedure.” (A. 173.)

Petitioner contends that the Louisiana Supreme Court’s

reliance on Hoyt was misplaced, since his case raises the

issue left open by Hoyt, viz., whether the total exclusion

of women from juries violates the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. Petitioner urges that Hoyt

should not be extended to approve such total exclusion.

A. This Case, Unlike Hoyt, Involves the Total

Exclusion of Women from Juries.

In Hoyt, this Court sustained a Florida statute22 essen

tially the same as Article 402 against attacks on its con

stitutionality both on its face and as applied. It is with

regard to the latter aspect of H oyt that petitioner contends

that the present case presents facts sufficiently different to

require a different result.

22Fla. Stat. Ann. § 40.01(1): “ . . . provided, however, that the

name of no female person shall be taken for jury service unless said

person has registered with the clerk of the circuit court her desire to

be placed on the jury list.” As will be discussed below, in 1967 this

section was amended to remove this provision and substitute an

exemption limited to “expectant mothers and mothers with children

under eighteen (18) years of age, upon their request . . .” Laws

1967, C. 67-154, § 1.

24

In Hoyt, the Court pointed out that it found “no sub

stantial evidence whatever in this record that Florida has

arbitrarily undertaken to exclude women from jury service”

(386 U.S. at 69). Similarly the Chief Justice and Justices

Black and Douglas concurred in the result since they could

not say “from this record that Florida is not making a good

faith effort to have women perform jury duty without dis

crimination on the ground of sex.” {Ibid.) These conclu

sions were supported by the facts that there were women

on the jury rolls in the county, and that efforts had been

made to include all eligible women on the rolls. Thus, it

could not be concluded that the jury commissioners had

acted in any way to purposefully exclude women discrimi-

natorily (368 U.S. at 68).

The record in this case presents a far different picture

when the jury selection procedures utilized are examined.

The jury commissioners used a variety of sources to obtain

names of persons to whom preliminary questionnaires would

be mailed. These questionnaires were not for the purpose

of actually summoning persons to jury duty, but only to

determine eligibility. Despite this, women were deliberately

passed over as persons to whom questionnaires would be

sent.23 Moreover, only preliminary attempts had been

made to encourage women to declare their desire to serve

on juries (A. 54). The result of these practices was that

there were no women whatsoever on the jury lists. No

explanation was given as to why it would not have been

possible to send questionnaires encouraging women to vol

unteer to serve and thereby to obtain at least some repre

sentation on the jury rolls.

Thus, unlike Hoyt, the record in this case demonstrates

that the jury selection procedures deliberately avoided

placing women on juries. The affirmative actions of the

23 Questionnaires were sent to every eighth person on the registrar

of voter’s list. However, if that person “was a doctor or i f it was a

lady or if it was a school bus driver” the name was passed over and

no questionnaire was sent (A. 35-36).

25

commissioners were an important factor in there being no

women on the jury lists at all.

B. The Total Exclusion of Women Violates the

Requirement of Representative Juries Imposed

by the Due Process Clause.24

In Carter v. Jury Commission o f Greene County, 396

U.S. 320 (1970), this Court defined “the very idea of a

jury” as being ‘“ a body truly representative of the commu

nity.’ ” (396 U.S. at 330.) Thus, the Court established

firmly what it had earlier suggested in Smith v. Texas, 311

U.S. 128 (1940), that the exclusion from jury service to

any large, identifiable, and significant group in the commu

nity violates the requirements of due process. See Labat v.

Bennett, 365 F.2d 698, 719-24 (5th Cir. 1966.)25

It is clear that the practice approved by the courts of

Louisiana in the case violated this fundamental requirement.

First, as shown above, more than 50% of adults were auto

matically and totally kept off the jury rolls. Second, the

persons were excluded solely because they belonged to a

particular group, women. Third, it is clear that women are

a significant, identifiable group of the community within

the meaning of the cases cited above.

This Court specifically so held in a case involving the

administration of the federal jury selection statutes, Ballard

v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946).

24Since petitioner is male, his challenge arises under his due proc

ess right to a jury venire from which no class has been arbitrarily ex

cluded. See Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698, 723-24 (5th Cir. 1966).

25In Labat, the Fifth Circuit, in dealing with the total exclusion

of wage earners as a class from Louisiana juries, read into the consti

tutional requirement of representative jury rolls this Court’s holdings

in Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1941), and Thiel v. South

ern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946), which dealt with interpreta

tions of federal jury statutes.

26

It is said, however, that an all male panel drawn

from the various groups within a community will

be as truly representative as if women were included.

The thought is that the factors which tend to influ

ence the action of women are the same as those

which influence the action of men—personality,

background, economic status—and not sex. Yet it

is not enough to say that women when sitting as

jurors neither act nor tend to act as a class. Men

likewise do not act as a class. But, if the shoe were

on the other foot, who would claim that a jury

was truly representative of the community if all

men were intentionally and systematically excluded

from the panel? The truth is that the two sexes

are not fungible; a community made up exclusively

of one is different from a community composed of

both; the subtle interplay of influence one on the

other is among the imponderables. To insulate the

courtroom from either may not in a given case make

an iota of difference. Yet a flavor, a distinct quality

is lost if either sex is excluded. The exclusion of

one may indeed make the jury less representative o f

the community than would be true i f an economic

or racial group were excluded. (329 U.S. at 193-

94) (Emphasis added; footnotes omitted.)

Hence, it was concluded, the exclusion of women denied

the right to a jury selection procedure that would result in

rolls being representative of the community as a whole.

Ballard, of course, involved the administration of the

federal jury selection statutes. Petitioner urges, however,

that its reasoning compels the same result under the con

stitutional standard as enunciated in Carter. The right in

both instances is to a jury list selected so as not to exclude

a representative cross-section of the community; for the

reasons set out in Ballard a selection process that excludes

all women violates that fundamental right.

Thus, a three-judge federal district court struck down an

Alabama statute which, by prescribing that one of the qual

ifications for jury service was that the person be a male cit-

27

izen,26 totally excluded women for jury service (White v.

Crook, 251 F.Supp 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966). The court said:

The time must come when a state’s complete

exclusion of women from jury service is recognized

as so arbitrary and unreasonable as to be unconsti

tutional. 251 F. Supp. at 409.

Therefore, the court held, the Alabama statute violated

the Fourteenth Amendment.

This case, of course, like Hoyt, involves a statute which

is not on its face an absolute prohibition on women serving

on juries.27 Petitioner urges, however, that on the factual

showing made here the statute operates as such a prohibi

tion, so that this case is in all essentials the same as White

v. Crook.

The Louisiana statute singles out women and excludes

them automatically unless they volunteer to serve by filing

a declaration to that effect with the court. Presumably,

the state will seek to justify a scheme which operates to

exclude all women on the ground that it is not wholly

irrational in light o f assumptions concerning the general

role of women in society. Petitioner contends, on the

other hand, that once a denial of a constitutional right has

been shown—here, to jury selection methods that result in

jury lists representative of the community as a whole—the

State must be put to a much stricter test of justifying what

it has done. Thus, it must show that its legitimate goal-

exempting women with family responsibilities who would

suffer hardships if forced to serve on juries—cannot be

26Title 30, § 21, Code of Alabama, Recompiled 1958.

27At the present time, no state has such an absolute prohibition.

The three states that barred women totally at the time of the deci

sion in Hoyt have since amended their statutes. Compare the stat

utes cites in Hoyt, 368 U.S. at 62, n. 5, with Ala. Code 1940, Tit.

30, §§ 21, 21.1, as amended 1966 Ex. Sess. p. 429, § 4, p. 427, § 1;

Mississippi Code 1942 Ann. (1956), § 1762, as amended by laws,

1968, Ch. 335, § 1; and South Carolina Code 1962, § 38-52, as amend

ed, 1967 (55) 895.

28

accomplished by more narrow means that will not result

in fact in a denial of constitutional rights. In other words,

a compelling need for Article 402 must be shown. Shapiro

v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 634 (1969).

It is submitted that such a showing simply cannot be

made. Rather, Louisiana is now in the position, along

with one other state, New Hampshire,28 as having a jury selec

tion scheme most likely to keep all women from serving

on juries. As pointed out above, Alabama, Mississippi, and

South Carolina no longer exclude women from jury serv

ice,29 and Florida, the state involved in Hoyt, now calls

women for jury service on the same basis as men and limits

its special exemption to women who are pregnant or who

have children under eighteen who affirmatively request

exemptions.30 Of the sixteen jurisdictions (excluding Louis

iana and New Hampshire) noted by this Court in H oyt31

that allowed women an absolute exemption based on their

sex i f requested, five states have now placed women on

essentially the same basis as men and allow exemptions

only for specific occupations.32

Thus, the vast majority of states either treat women no

different than men, or allow women to be excused from

jury duty by focusing specifically on the question of

whether family duties in the particular case require an ex

emption. Even those states which allow a blanket exemp-

“ N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann., 1955 § 500:1.

29 See footnote 27, supra.

^Fla. Stat. Ann. § 40.01, as amended, Laws 1967, C. 67-154, § 1.

31368 U.S. at 62, n. 6.

32Idaho (Idaho Code § 2-411 has been rep ea led Minnesota (Minn.

Stat. Ann., § 593.02, as amended); North Dakota (North Dakota Cent.

Code § 27-09-04, repealed by S.L. 1967, Ch. 251, § 1); Virginia (Va.

Code § 8-178(30) amended, now exempts housewives rather than wo

men); Washington (Wash. Rev. Code, § 2.36.080, amended to remove

exemption of women per se).

29

tion based on sex call women for jury duty and put the

burden on them to request the exemption. Such a scheme

is at least far more likely to result in women being on jury

rolls in some numbers in contrast to the operation of the

Louisiana statute as shown here.

In sum, the Louisiana statutory scheme simply goes

much further than necessary to achieve any legitimate goal

of the state. It very well may be permissible to excuse

women with family obligations from jury duty. But the

statute does not focus with sufficient particularity on this

restricted objective. Rather, it rests on the wholly unwar

ranted assumption that all women are bound to be so en

meshed in family obligations that they can be assumed not

to be able to serve on juries. Recently, this Court has

rejected such an assumption as a basis for denying employ

ment to women because of the operation of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S.

542 (1971). Surely the Constitution’s requirement that

jury rolls be representative of the community as a whole

compels the same result.33 This is particularly true in

light of the fact that virtually every other state has found

it possible to achieve the legitimate state purpose of exempt

ing those women nwho would actually suffer hardships be

cause of family responsibilities without resorting to a statu

tory scheme whose result is to have no representation of

women on jury rolls whatsoever.

33As the Court in White v. Crook found and held:

[T] he exclusion of women from jury service in Alabama by

a statutory provision is arbitrary in view of modem political,

social, and economic conditions . . . .” 251 F.Supp. at 409.

30

III

THE INTRODUCTION OF PETITIONER’S ALLEGED

CONFESSION VIOLATED HIS RIGHTS TO DUE PRO

CESS OF LAW.

It is clear from the record that the requirements of Mir

anda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), were not complied

with in two important respects before petitioner’s state

ment was taken.34 Unquestionably, an attempt to give a

Miranda warning was made;35 however, the interrogating

officer failed to inform petitioner that he was entitled to

have an attorney present at the time a statement was given.

Indeed, he testified explicitly that he had not informed

petitioner of that right.36 In Miranda, however, this

Court held that that specific warning was “an absolute pre

requisite to interrogation.” 384 U.S. at 471.

The second failure to comply with Miranda arose from

the fact that there was no affirmative, intelligible waiver of

the defendant’s rights, and that such a waiver does not

appear on the record. This Court specifically rejected the

notion that waiver could be inferred by the silence of the

accused, or by the fact that he responded to questioning

after the warning was given:

Moreover, where in-custody interrogation is involved,

there is no room for the contention that the privi

lege is waived if the individual answers some ques

tions or gives some information on his own prior to

invoking his right to remain silent when interrogated.

384 U.S. at 475-76.

Here, however, the interrogating officer testified that after

he gave petitioner a warning, petitioner simply began answer-

34Petitioner was tried in 1968, after the effective date of Miranda.

35See, A. 70, 74, 85, 100-101.

36A. 157-158 (quoted supra, in footnote 9).

31

ing questions. There clearly was no affirmative waiver of

his rights as required by Miranda. 37

Hence, the conclusion is inescapable that the testimony

of the officers themselves establishes a failure to comply

with Miranda, and the conclusions of the courts below to

the contrary rested on a misunderstanding of that decision.

If, therefore, the confession had been introduced as part

of the prosecution’s case in chief, rather than for impeach

ment purposes, the conviction would have to be reversed.38

However, after the petition for writ of certiorari was filed

in this case, this Court handed down its decision in Harris

v. New York, 401 U .S .____ , 28 L.Ed.2d 1 (Feb. 24, 1971).

Harris held that, even though a confession was taken in

violation of Miranda, it could be used to impeach the tes

timony of a defendant. Petitioner urges that his case is dis

tinguishable from Harris, and that that decision should be

limited to circumstances where there is no question but

that the confession to be introduced is fully reliable.

Harris relied on the decision in Walder v. United States,

347 U.S. 62 (1954). Walder involved the admissibility of

physical evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amend

ment to impeach testimony given by a defendant. Walder,

who was being jlrosecuted for violation of the federal nar

cotics laws, testified that he had never sold or possessed

any narcotics in his life. The government then put in evi

dence concerning a heroin capsule seized from Walder’s

home, including testimony of a chemist who had analyzed

the capsule. As is the case in virtually all cases involving

the admissibility of physical evidence, there was no ques

tion as to the reliability of the particular piece of evidence;

as to that issue, the illegality of the search had no bearing.

37(A. 78-79; 90; 92; 158.) See footnote 10, supra, for the Offi

cer’s testimony.

38 As will be discussed below, the impact of the confession was

such so that its introduction could not said to be harmless error under

the rule of Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967).

32

Confessions, on the other hand, present an entirely dif

ferent question. Miranda is rooted in this Court’s long

experience in grappling with problems of the inescapable

uncertainties that arise when it is claimed that a defendant

has confessed in a police station, in the presence of officers

only, and without aid of counsel or any other assistance.

The circumstances of this case vividly illustrate the validity

of that concern.

Petitioner, a black teenager, was placed alone in an inter

rogation room with three armed police officers at about

2:30 a.m. He was charged with a serious crime—the rape

of a white woman. He was without counsel and had not

contacted his parents. The interrogating officer failed to

inform him fully of his constitutional rights, and the rec

ord shows that he did not waive those rights. There was

no stenographer to take down his statement and no tape

recording was made, even though court reporters and record

ing machines were available (A. 93-94). One officer asked

questions and responses were given; the officer jotted down

notes and then typed a statement.

When the officer read the statement to petitioner, he

refused to sign it. The officers testified that he said he

would not sign it because he didn’t have his shoes; petitioner

testified that he refused because the statement was not what

he said. He contended that he did not commit the crime,

while the statement was an admission of his participation

in it. The next morning he gave a statement to a detective

that, he claimed, substantially agreed with the version he

gave at trial.

Thus, this case presents a classic example of the circum

stances Miranda sought to avoid. Although it cannot be

said that the statement was coerced, the atmosphere in

which petitioner was placed, together with his adamant

refusal to sign the alleged confession must give rise to seri

ous doubt as to what in fact went on and what in fact

was said by petitioner. The inherent and inescapable ques

tions as to the reliability of the statement compel the con-

33

elusion that, in the absence of proper Miranda warnings, it

was inadmissible for any purpose.

This result under these facts would not mean, of course,

that confessions unaccompanied by proper Miranda warn

ings, would necessarily be unreliable. The use of a court

reporter or the tape recording of a statement or the sign

ing of a statement by a defendant would create the same

kind of reliability that attaches to physical evidence such

as was involved in Walder and other search and seizure cases.

Absent such objective indicia of reliability, however, the con

cerns that prompted the decision in Miranda must prevail.

Finally, it is clear that the use of the alleged confession

was not harmless error within the meaning of Chapman v.

California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967). Petitioner gave in his de

fense a story that was consistent with his presence at the

scene of the crime but which exculpated him. Whether the

jury would have believed him without the confession being

introduced is, of course, impossible to tell. But there can

be no doubt that the introduction of a confession to the

crime that directly contradicted his direct testimony could

only have had a devastating impact against him that made

it improbable in the extreme that the jury would accept

his story.

34

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the indictment against peti

tioner should be dismissed and his conviction reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

lack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Margrett Ford

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Charles Finney

P.O. Box 3463

Lafayette, Louisiana 70501

Attorneys for Petitioner

la

APPENDIX

1. STATUTES OF LOUISIANA RELATING TO JURY SELECTION

Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure, Vol. 1, pp. 317-

391, articles 401 -04, 408, 410-411, 413-417, 419. Note:

In 1968, following the trial of petitioner, amendments were

made to certain of these statutes. Following is the text of

the statutes as of the time of petitioner’s trial. The amended

statutes are set out in a footnote to each of the altered sec

tions.

Art. 401 — In order to qualify to serve as a juror, a per

son must:

(1) Be a citizen of the United States and of this state

who has resided within the parish in which he is to serve

as a juror for at least one year immediately preceding his

jury service;

(2) Be at least twenty-one years of age;

(3) Be able to read, write, and speak the English language;

(4) Not be under interdiction, or incapable of serving as

a juror because of a mental or physical infirmity; and

(5) Not be under indictment for a felony, nor have

been convicted of a felony for which he has not been par

doned.

Art. 402 - A woman shall not be selected for jury serv

ice unless she has previously filed with the clerk of court

of the parish in which she resides a written declaration of

her desire to be subject to jury service.

Art. 403 - The following persons are exempt from jury

service, but the exemption is personal to them and is not

a ground for challenge:

(1) The governor, lieutenant governor, state comptroller,

state treasurer, secretary of state, superintendent of public

education, their clerks and employees, the members, offi

cers, and clerks of the legislature, and the judges and active

officers of the several courts of this state;

2a

(2) Any other public official, if jury service would seri

ously interfere with the performance of his official duties;

(3) Attorneys-at-law, peace officers, ministers of the

gospel, physicians and dentists actively engaged in the prac

tice of their professions, school teachers, school bus drivers,

pharmacists, members of paid fire departments, chiefs and

their first assistants of bona fide volunteer fire departments,

and persons who are required to travel regularly and routinely

in the course and scope of their employment;

(4) Persons who because of age, sickness, or other phys-

incal infirmity would suffer serious detriment if required to

serve as a juror; and

(5) Persons who have served as grand or petit jurors in

criminal cases or as trial jurors in civil cases during a period

of twelve months immediately preceding their selection for

jury service. Amended by Acts 1968, No. 108. S i . 1

1 Art. 403 — The following persons are exempt from jury service,

but the exemption is personal to them and is not a ground for chal

lenge:

(1) The governor, lieutenant governor, state comptroller, state

treasurer, secretary of state, superintendent of public education, their

clerks and employees, the members, officers, and clerks of the legisla

ture, and the judges and active officers of the several courts of this

state;

(2) Any other public official, if jury service would seriously

interfere with the performance of his official duties;

(3) Attorneys-at-law, peace officers, ministers of the gospel,

physicians and dentists actively engaged in the practice of their pro

fessions, school teachers, school bus drivers, pharmacists, members of

paid fire departments, chiefs and their first assistants of bona fide

volunteer fire departments, and persons who are required to travel

regularly and routinely in the course and scope of their employment;

(4) Persons who because of age, sickness or other physical

infirmity would suffer serious detriment if required to serve as a juror;

and

(5) Persons who have served as grand or petit jurors in criminal

cases or as trial jurors in civil cases during a period of three years

immediately preceding their selection for jury service.

3a

Art. 404 — The jury commission of each parish shall con

sist of five members, each having the qualifications set forth

in Article 401.

In Orleans Parish the jury commission shall be appointed

by the governor, and the commissioners shall serve at his

pleasure. In other parishes the jury commission shall con

sist of the clerk of court or a deputy clerk designated by

him in writing to act in his stead in all matters affecting

the jury commission, and four other persons appointed by

written order of the district court, who shall serve at the

court’s pleasure.

Before entering upon their duties, members of the jury

commission shall take an oath to discharge their duties

faithfully.

Three members of the jury commission shall constitute

a quorum.

Meetings of the jury commission shall be open to the

public.

Art 408. — In parishes other than Orleans, the jury com

mission shall select impartially at least three hundred per

sons having the qualifications to serve as jurors, who shall

constitute the general venire.

A list of the persons so selected shall be prepared and

certified by the clerk of court as the general venire list

and shall be kept as part of the records of the commission.

The name and address of each person on the list shall