Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Suggestion for Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Suggestion for Oral Argument, 1975. 980a98e2-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c03ea5a-9220-4c0a-a1f6-81af7fe91810/carr-v-montgomery-county-board-of-education-suggestion-for-oral-argument. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

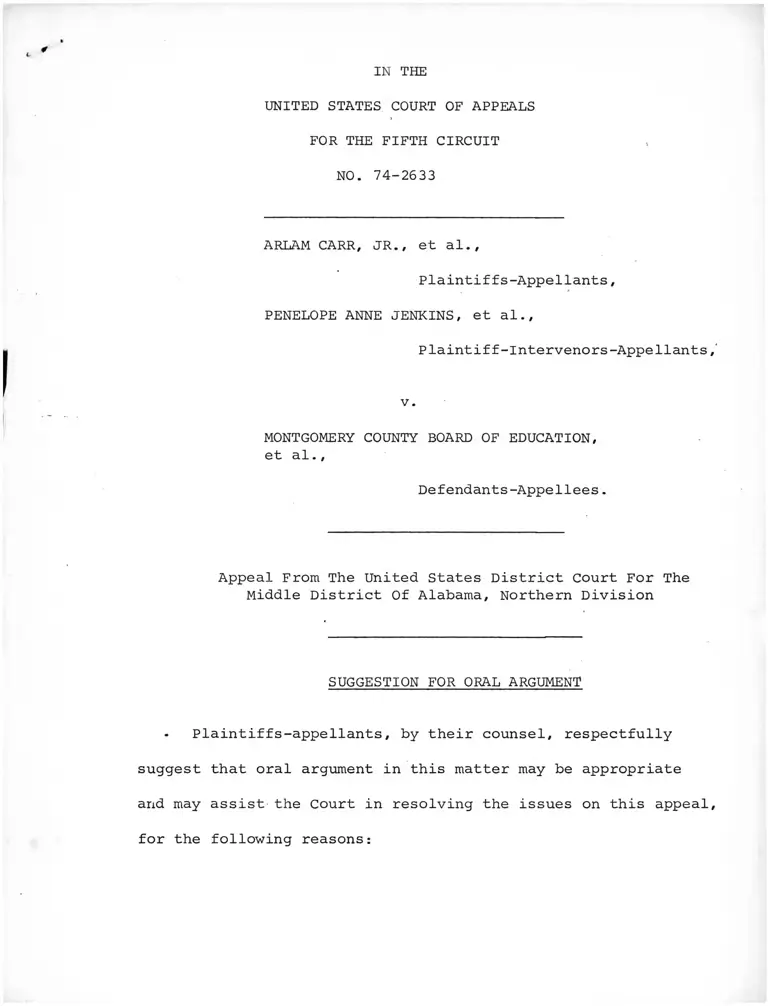

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-2633

ARLAM CARR, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

PENELOPE ANNE JENKINS, et al.,

P laint if f-Intervenors-Appellants,'

v.

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Middle District Of Alabama, Northern Division

SUGGESTION FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

- Plaintiffs-appellants, by their counsel, respectfully

suggest that oral argument in this matter may be appropriate

and may assist-the Court in resolving the issues on this appeal,

for the following reasons:

1. This is an appeal from a district court decree in

a school desegregation case approving a plan of pupil assign

ment which is attacked by the appellants herein as inadequate.

2. Pursuant to the procedure established originally in

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 419

F.2d 1211, 1222 (5th Cir. 1969) for appeals from rulings on

remand in those consolidated cases, and subsequently made

applicable by letter directive, to all school desegregation

appeals in this Circuit, the briefing schedule on this appeal

was expedited and no oral argument has been scheduled. See, £.g_.,

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 424 F .2d 320, 323 n. 1

(5th Cir. 1970) .

3. The Briefs of Appellants herein were mailed on July

9 and July 25, 1974, respectively; the Brief of the United States

as amicus curiae was mailed on July 26, and the Brief of

Defendants-appellees on August 9, 1974. Reproduction of the

record on appeal and transmission to the Clerk's office was

completed on September 3, 1974. Thus, the matter has been before

the Court for six months.

4. In their Brief, plaintiffs-appellants sought reversal

of the district court's ruling and instructions to that Court

to implement a fully constitutional plan of desegregation "at the

earliest feasible opportunity and in no event later than the

2

Second Semester of the 1974-75 school year. . . That relief

is now impossible and the necessity for appropriate planing for

the 1975-76 school year is close at hand.

5. Although oral argument in school desegregation cases

before this Circuit has become the exception rather than the

rule, but see, <2 .c[., Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied, 409 U.S. 1007 (1972), we respectfully suggest

that the presentations of counsel might be helpful to the Court

in reaching a satisfactory resolution of the issues.

For these reasons, we respectfully suggest that oral

argument in this case may be appropriate and we stand ready,

on behalf of plaintiffs-appellants, to participate in argument

of the case should the Court so desire.

Respectfully submitted,

SOLOMON

FRED T.

S. SEA^,

GRAY

Gray, Seay and Langford

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

3

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 10th day of March, 1975,

I served copies of the Suggestion For Oral Argument in this

matter upon counsel for the parties herein, by depositing same

in the United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid, addressed

to each as follows:

Vaughn Hill Robison, Esq.

Hill, Robison, Belser & Phelps

815-30 Bell Building

P. 0. Box 612

Montgomery, Alabama 36102

Hon. Ira DeMent

United States Attorney

P. 0. Box 197

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Joseph D. Rich, Esq.

William C. Graves, Esq.

Department of Justice

550 11th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20530

Howard A. Mandell, Esq.

212 Washington Building

P. 0. Box 1904

Montgomery, Alabama 36103

4