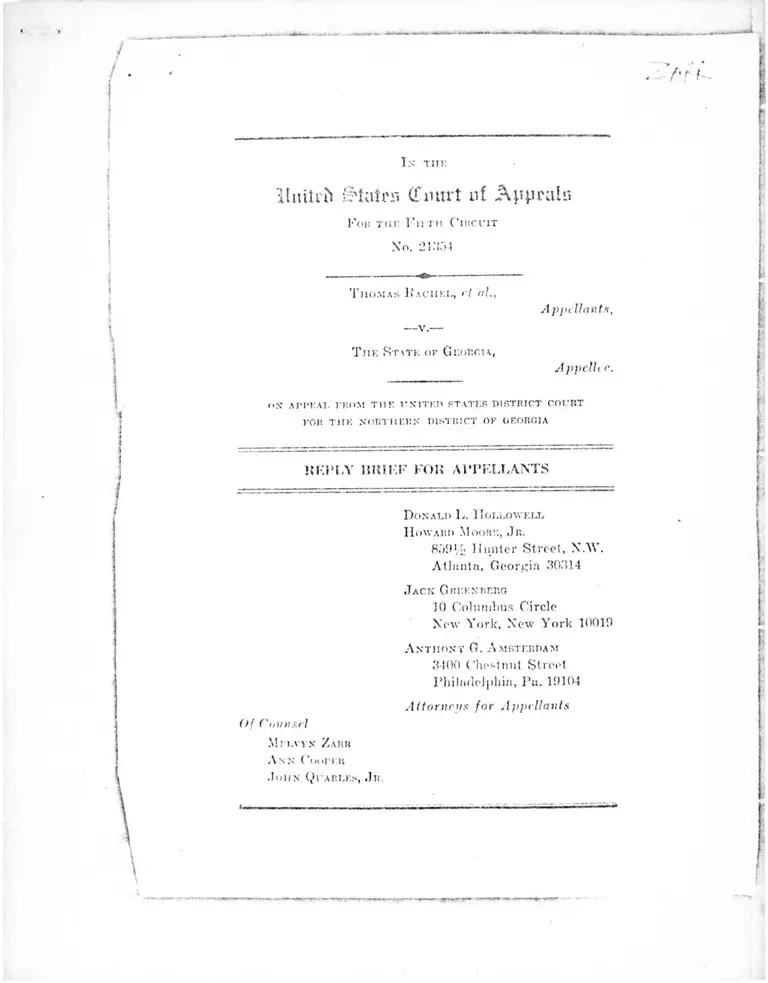

Rachel v. Georgia Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rachel v. Georgia Reply Brief for Appellants, 1964. 0cfde2bd-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c14fd7f-b322-49b7-9ac9-60945e3794a4/rachel-v-georgia-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

Ix TI1K

‘{ t u i U ^ r - f 'tatm ( f m i r t n f A y p r a l i i

Foi! THE Fll'TM C ircuit

Xn. 2 1 :1 0 4

T h o m a s L 'a c i i e l , el a!.,

-v-

T i i e State of Georgia,

A ppcllants,

Appclh

o x ARREAE FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COT TIT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

f ' t ^

KF.PI.Y HKIFF FOK APPE LLAN TS

Donald L. 3 Toi.lowell

H oward Moore, Jr.

PoiHA Hunter Street, XAY.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Jack Greenhero

10 ColmnVms Circle

New York, New York 10010

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 10104

O f C o u n s e l

A t t o r n e y s f o r A p p e l l a n t s

-M J I.VVN Z arr

A nn Coheir

.loll N Ql ARI.ES, .In.

- v i» W 'n r n » « » r * y »

I N D E X

PAGE

I. This Court may properly consider Die ease before

it as on petition in the nature of mandamus or

habeas corpus........................................................ j

II. Should the Court decline to entertain this case as

on mandamus, no doctrinal obstacle^ precludujfits

treatment as on habeas corpus............................... 4

III . The Judicial Code of Ifni, relied upon by appellee

as changing prior law, did not do so ................... 8

IV. Appellee improperly draws from the Civil Rights

Act of 19(14 the inference that remand orders were

not reviewablc prior to its effective date ............. 8

V. JJaincs v. Danville should not be followed here... 9

2 P r o o f s D-l f i -b l

I n t h e

l l m t i ' i i g l a i r s CCmtrt n f A ^ r a l o

For the F ifth Cine lit

Xo. 2inr. f

T homas Rachel, ct al.,

Appellants,

T he State ok Georgia,

Appellee.

OXA1TEAU FROM T1IK UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

KOIt THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

r e p l y b r i e f f o r a p p e l l a n t s

The purpose of this: reply brief is 1o present such author

ities, pertinent to the points made in appellee’s brief (here

after Ur.), as cannot conveniently be put before the Court

on oral argument. Appellee's points v.hicli miss the sub

stance of appellants’ or which do not suggest the need for

consideration of additional authorities are not addressed

lie re.

I.

This Court ’May Properly Consider the Case Before It

as on Petition in the Nature of .Mandamus or Habeas

Corpus.

Appellants have urged that this Court hold their motion

of March 12, lbbl (Appellants’ Br., App. 71-7.’!) and its at

tachments jurisdictionally sufficient to put the case before

it ns on an application for an order in the nature of man-

damns or for habeas corpus. (Appellants’ Br. 30-32, 43.)

A Pi •(•lice objects that the motion looks like none of tlieso

things and cannot therefore be so treated. (Hr. 13-18, 19-

20.) Appellee correctly points out that the authorities cited

at Appellants’ Hr. 33, supporting tin* extreme liberality of

the federal courts in const riling-papers to seek whatever

relief is available consistent with their substance, are all

cases involving imprisoned criminal convicts without

lawyers; and appellee asserts that such liberality is imper

missible except in the case of “ unlettered, incarcerated de

fendants without counsel and without funds.” (Hr. 10.)

However, the cases cited by appellants were only exem

plary, In many others, lawyer-filed documents have been

accorded the same liberal treatment. K.g., Georgia Hard

wood Lumber Go. v. Campania de Xuvegacion Transmar,

S.A., 333 lb S. 334 (1943) (notice of appeal treated as ap

plication for allowance of appeal in admiralty in order to

save appeal); Crump v. Jlill, KM F.*2d 30 (3th Cir. 1939)

(tiling in Court of Appeals of acknowledgment of service

of notice of appeal and designation of record treated as fil

ing of notice of appeal in order to save appeal); Den Isles

v. Kraus, 233 F. 2d 233 (3th Cir. 1933) (application for

leave to appeal in forma puu/uris treated as notice of ap

peal in order to save appeal); Hath v. Bird, 239 F. 2d 237

(3th Cir. 1930) (same); O'Xeal v. Knifed Slates, 272 F. 2d

412 (3th Cir. 1939) (appeal bond treated as notice of ap

peal in order to save appeal); Carter v. ('ampheU, 283 F.

2d OS (3th Cir. 1900) (securing of District Court order

transmitting exhibits to Court of Appeals, and tiling in

Court of Appends a motion for leave to prosecute appeal on

typed record treated as filing notice of appeal in order to

save appeal); and for an extreme instance see I/adjipa-

h ras v. J’ad/iea, S.A., 290 F. 2d 097 (3th Cir. 1901) (motion

in District Court for allowance* of appeal in admiralty and

motion in Court of Appeals for expedited hearing treated

, r,r Bmrtfawiii - (/.'i-m.,r« u .ifctxwiSafia* --ai ■ »*t<'; * « « r« ir*» i■kw~fcBjA»TidBJir t f 3«*m• MUfii&i&Sitei.

I

3

ns ]n'titinii' to tin- respective courts for allowance of inter

locutory appeal) (alternative ground).‘ Tliese eases make

apparent that whenever a paper is tiled elearly evincing a

desire to seek appellate review, the jurisdictional require

ment is satisfied irrespective of the form of the paper.* In

the present ease, at least as early .as March 12, liHil it was

apparent to appellee and to till courts concerned that ap

pellants were seeking review of the District Court’s remand

order by any available mode.

1 The clear weight of federal authority supports the Fifth Circuit

decisions cited. /.*.</.. I ii i'i /.< o/h, 139 j*. ltd .Isiti ( 1). C. Cir. 1013)

(petition to Court of Appeals for special appeal treated as notice of

appeal in order to save appeal) ; Soci i t i I nh r n a tw n a h Pour Pur-

t ic i /Hi 1 ions Industri i lies i t ('oinnii relates, S. *i. v. McGrath, ISO

F. od .((it; ( 1), ( ’ . Cir. 1930) (same; ; The Asturian, f>7 F. 2d 8f> ( 9th

Cir. 1032) (petition for lihel of review treated ns petition for re

hearing in order to extend appeal time and save appeal) ; Dickey v.

Pnit i i l S t a h s , 332 1'. 2d 77tt ( 9th Cir. 19ti4 ) (notice of motion for

new trial treated as motion tor lew trial m order to extend appeal

(inn* and save appeal). Itv contrast, tin* Seventh Circuit tends to

insist on technical perfection. Unison v. Atchison, Topeka <(• Santa

/■’. liy. Co., 2s0 1'. 2d 72ti ( 7111 Cir. 10(11 ), a r t . t lcniul, 3(58 U. S.

s:;,') (lotil i. tint this Court has previously taken “ the more liberal

rule" in such matters. P nih i l S t u b s v. Stromhi ry, 227 F. 2d 1*03,

tint Cith Cir. to:.:.) i notice of appeal from denial of post-trial

motion* treated as addressed to underlying judgment as Well), and

tin Supreme Court has suhsetpiently agreed. Ponton v. Davis, 371

t S . tvs (1 fi('.2 ) ( same).

" Appellants' counsel would he worse than disingenuous not to

concede that 111 * * i r papers were b.nlh styled and that they are now

in tin* era eel *ss posture, as appellee puts it, of “ scrambling” (Hr. 8 )

to preserve their clients' rights of review. In February and March,

l!m I do* manlier of obtaining r< \ iew of a district court remand

order was far from clear and. while this do**s not excuse counsel’s

ii-ititiii-.il :.*ii 1 uto s, it does suggest do* harshness of visiting irrepara

ble eon vi|iii*nei*s on appellants, t ' t . IS construct ion Finance t'or)i,

v. Prinh n c St curitii s Advisory Group, 311 C. S. f)7!t ( 1911)

(notiec of appeal treal'-d as petition to Court of Appeals for leave

to appeal where method ot' appeal was unsettled); Pn l t in y v. Hill-

h id ie k . 17s K. 2(1 771 i!Mh Cir. ICC* i notice of motion for n stay

of exeention pending posting of a supersedeas bond treated as

notice of appeal where manic r of a notice of appeal was unsettled).

..'>PKWtW . .•**.. liUS* hwJ£*rWS-.-wA«»w «^.--iS*

•1

II.

Should the Court Decline to F.ntertuin This Case up

on '.!; iitl.iiiiti'. No Doctrinal Uli'-taclcs Frccude Its

I reatioeitl as on Habeas Corpus.

Appellants’ principal reliance is upon the availability of

mandamus in this Court to review the District Court’s er

roneous construction of the civil rights removal statute.

(See Appellant-‘ Hr. 30-42.) If mandamus is unavailable,

appellants have urged (1) that the question of the validity

of the order below is cognizable within the jurisdiction of

the judges of this Court to issue writs of habeas corpus

(Appellants' Hr. -Id U). or (2) that under 2S U. S. C. §2253

(1!»5S), this Court has jurisdiction on appeal to determine

whether the allegations of the removal petition did not

state a sufficient case for anticipatory federal habeas cor

pus. so that the District Court might have entertained the

petition under 2K C. S. C. '2211(e)(3) (IdoS). Appellee

relies principally that appellants neither were alleged to

he, nor were in fact, in custody for habeas corpus purposes.

(Hr. 20 24.)

Hoth the removal petition (K. 0) and the motion for re

lief in this Court (Appellants* Hr., App. 72) clearly allege

that appellants are on bail, and the motion additionally

alleges that they are in imminent danger of reincarceration

hv reason of raised bond ( ilml.). Appellee takes the posi

tion that bail status is insufficient eii-tody to support habeas

corpus under the concept o| custody authoritatively ad

vanced in ,lnn'.. \. ( ' mi a i n (fleiiii, 571 1 . S. 250 (1!l(i5), be

cause a defendant on bond. "i.~io tar as the State is con

cerned. . . . can go where he ph ases and do as lie pleases,

provided lie appear- to au-wer the charges against him.

(Hr. 22.) This assertion is dally belied by (h-orgia statute,

On. Cod.- Ann.. 105.3, 27 HOI, Appendix, infra, which an-

thorizes a surety to urro.d at

any tilin' <>a tin- surety s iti'T

llic Georgia c o u r t w hose

threatened hero— to increase

defendant and so cati'-e liis r

stances, appellants wen* in ]>i

held in custody, for they tve

shared by the public goner:

supra, ."71 1 . fv ut 2 Ml, and

time . . . and . . . thrown hack

the procedural safeguards t!

provided to those charged w

apjieilants’ circumstances in

carious than those of the |>ar

rearrest a hailed defendant

than the jiowcr to retake a ]>i

nest that appellants arc frv

do as they please so long a

ti 1 ile of incurring the dhp!

empoweretl to reincarcerate

h1 surrender his principal at

I- whim, and by the jiowcr of

exercise was immediately

the bond required of a bailed

earrest. 1’nder these circum-

actical tact as well as theory

re subject to “ restraints not

illy," Joins v. Cinniiiii/hani,

could he “ rearrested at any

in jail . . . with lew’, if any, of

lint normally must be and aro

ith crime," id. at 2-12. Indeed,

these regards were more pro-

(,!ee in J o i n s , for the power to

in Georgia is itiore arbitrary

moled. It blinks reality to sug-

c to go where they please and

s their every action is suscep-

casure of courts and sureties

them at will.4

Aj i j ie l lee twi ts appellants for their suggestion (alterna

tive (2) supm) that their removal petition is cognizable as

a petition for habeas corjius in the District Court. Antici-

S ’1 1 1,, entire raison </V/r« of lh<- hail oh! i cut ion, o f course, is to

i m I a im* eoie.lniiiils on the hailed defendant. See Stack v. Hoyle, 312

|- s. 1. ,'i in.'il). Hi torieally. a liaih'd defendant is deemed to

remain in . nstody. 2 H a m :. I ' m as or Tin. ( nows 124 (1st Ameri-

i'im i d.. I ’ liila 1 s ]7 t ; •_> poi.i oi k x M aitt.anh, H istohv or K nouish

l,\\V .'|S?l CM III. p lug) ; l l|tl III l>, 1'HIMINAI 1 'KOI I HU II I'. ITiOM A !!-

r mu A m u . 123 MOIT-. ami win re- as in Georgia— this eon-

ptinn is at tend i-d liy an arbitrary power of narrest, the hailed

di' limtant is tni lv “ *on a string.’ ’ tuylor v. l am to r , 10 "NN all. .100,

I'.', 1-2,72 1''7 2 ).

1 The alms.- of hail to |iunisli un)io|mlar defendants in civil rights

i liv.-s ha h ■■ n d"i-ui:nnl>-d by lie' I'.'iiorl.'l's n! lt.\ll. IN THU 1 NITKl)

S i a ii .s: 100 1. A l(i i'-.ut io n i l : X ai ionai ( 'unit .him i; on Hail, and

( ’him in ai, .1 i s hi i: (May 27-23, 130 1), at a3

___ »>«».. ■uiw 2K*U 1- fcn

6

jiatorv habeas corpus is designated a ‘‘new legal notion.”

( lir. 25.) Quite apart from tIn* fart that habeas corpus is

<»! im memo rial Fn " 1 is li u - a: ■ e ( nine! i mes accompanied by a

writ of privilege) for tie precise purpose of removing

cases from one court to another in anticipation of trial, see

8 I!i.ackston!'. CoM.MF.xTAiiir.K 1‘J:t (fit!) rib, Dublin 177a) ;

.Teaks, '1 he Story of the Habeas Corpus, IS H. Q. ItKV. G4

(1902), anticipatory federal habeas corpus for state pris

oners has had long and considerable usage. A cable's case,

oiled in Appellants’ Hr. ft! n. 49, discusses this use of the

writ ii, detail; and, in addition to the cases cited in that

foonote. see, »•.//.. Hunter v. I f W , 200 I T. S. 207) (1908);

Amlermn, v. Illlintl, 101 Fed. 009 ( Ith Cir. 1900), dism’d, 22

S. Ct. 9.80 (1902); IIV.s7 I 'irnhtin v. Lamp. 133 Fed. 887

(4th Cir. 1901); Had v. Mnilthn. 87 F. 2d 810 (8th Cir.

1937); finite Cninraif, -18 Cod. 77 (C. C. I). S. C. 1891);

/•;./• parte li 'inner, 21 F. 2d 542 (X. D. Okla. 1927); lirawn

v. ('niit. 50 1’. Supp. 50 ( F. I'. Pa. 19-1 I) ; Lima v. Lanier, 03

F. Ktipp. 110 ( F. 1). Va. 19-15). As appellants stated at Ap

pellants’ Mr. 15-17, la p v. Sain, 372 F. S. 391, -110 (1903),

suggests that the conditions justifying anticipatory fed

eral habeas corpus are very similar to those justifying re

moval under 28 l . S. ('. II 18 ( 19.>S), and thus that the al

legations of this removal petition appropriately stated a

case for habeas corpus rebel.'

A|> p- 11- at 1Hr. 21 :M I/O‘s on ;i | r.is- age from tli e r emova l pe t i t ion

" lii, li. il ,nys. <1 i- * • 1 a ir-I > n ny i l ^\r. for 1l.lht .'In (•orjms n •li-f. The

: a - of r e a r lie i• 1 y S , l \ S 1ft at the i'Niianrc of l i ft In i is m r j m s

( 1)1 )■■ .It | pi I p- •> 1\ S o'. II lie 1 ■ ; u.v, i i> uiinci* - - a r y ; it

•In.-, n sp- ak to til I'stion a f i-siia •me of I m U m s r o r f i n s m l

u b l i c i t m i n m iflite r 2 - I '. S. ( ’. ; 22 11 '<•1(8) i 19 5 s | to secure

. • 1 iciprat«»ry feeit-ra) a • !.iu» beat ion o f a pi • l latUs’ ! e«!eral (h’felises.

Sie-li a at icip:ii<ri•y f -.! r;il iinl jmlie itiou i. eV.'O't ly what tli <• r emoval

pet i t ion seeks.

-----AsStfe

III.

Tho Judicial Cod.- of l ‘>l I. Relied Upon by Appellee

„« Changing Prior 1-nw, I>i<* ^ ot 1)0 So-

At I’li*. 2ft ::0 n]»|><• 11 *•<* concedes that appellants’ argument

supporting non-applieahility ol termer 1 14 < ( tl) (l.t.)S) to

criminal removal eases •‘might seem sound" under the origi

nal 1887 legislation hut for the effort of the codifications of

1 -j The 1919 legislative history refuting any

contention that Congress then meant to change prior law

is set forth at Appellants’ Hr. 2f.-27. As for the Judicial

Code of 1911 (and wholly apart from the eilect of v~9' of

the Code, see Appellants’ P.r. 21, 89-40), appellee’s argu

ment is foreclosed hv express declaration of Congress. Ju

dicial Code of 1911. §291, 80 Stat. 1««7. 1107;" General In

vest im,it Co. v. Luke Shove <f Miehif/mi Southern Ihj. Co.,

200 It. S. 201, 278 (1922).

IV.

Appellee Improperly Draws From the Civil Rights

Net of 100 1 the Inference That Remand Orders Were

Not Review aide Prior to Its Khedive Date.

Appellee argues (Hr. 81 88) that enactment of '901 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1901, 78 Stat. 211, 200, expressly con

firming appellate jurisdiction to review remand orders in

civil rights eases establishes lhat. prior to the effective date

of the 1901 act, such orders were not revicwable. “ That

*' *’Sre ‘.I’M. The provisions of this Act. so fur as the\ are suh-

stantwillv the same as existing statutes, shall lie construed as con

tinuations thermf. and not is new enactments, and there shall tie

no implieation of a char:..... . intent l>y r a-oii of a ehange of words

in sijeh statute, unless sueli e h a n g e u| intent shall he elearly mani

fest."

' " I T . - • “ ■ •vr-»r

. a ' MsbJM’-akk. i raAWtilwM-. .i. WiiMnia H ia sH *-^ *** ’ ~ ... J

8

type of argument is always unsatisfactory. At times, legis

lation expressly fixing rights and obligations may serve as

a make-weight in interpreting earlier legislation as not in-

tended to include any such rights or obligations; but such

a canon of interpretation should always bo cautiously em

ployed.” J,ou(jhm<tu v. Town of Pellioni, 139 F. 2d 989, 994

(2d Cir. 1918), cert, denied, 322 U. S. 727 (1944), per Cir

cuit .Judge Frank. The Supreme Court has otton enough

rejected this proposed canon of interpretation, e.cj., Ttoin-

walcf v. United Stoles, 3.>f> 1 . S. .>90. .>9.> (19.>8); [jiiitcd

Stoles v. Price, 3(11 V. S. 304, 313 (1900); United States v.

H'/sc, 870 V. S. 40.">, 414 (1902), and exposed the absurdity

of looking to congressional understanding in 1901 for the

interpretation of legislation enacted three-quarters of a cen

tury earlier, cf. United Stoles v. Phitodrl])hio National

n 874 V. s. 321, 848-349 (1903). As Professor Lusky

suggested in the November 1903 issue of the Columbia Law

Review, notwithstanding the respectability of ihe argument

that former 28 V. K. C. $1417(d) (1988) did not apply to

civil rights cases, it was “ preferable for Congress to take

the initiative and establish clearly the appealability of re

mand orders in eases removed under Section 1443.” Lusky,

Racial Discrimination and the 1‘ edernl Law: A 1 roblem

in Nullification, 0.8 Coi.r.M. L. Ri.v. 1103, 1189-1190 (1903).

Section 901 is not the only provision of the Civil Rights Act

of 1901 which affirms prior law. See, eg/., the “ State action”

provisions of \201(a), (h), (d), 78 Stat. 243. It is poorly to

esteem contemporary congressional solicitude tor ci\ il

Debts to twist the 1904 act, by devious reasoning, into a

ground for refusing these appellants a judicial remedy

which Congress has always allowed and which it now sa\s

in so many words shall he allowed.

V.

Haines \. Danville Should Not He Followed Here.

It is in order to advert at this point to Unities v. Danville

and cnni]>anion caso, till < ‘ir., Nos. OdSO-OOSl, 01 40-01 at),

O'JI2, derided Augu-t 111. lOtil, relied u]><>n by appellee at

Hr. (in 07. Unities indeed dismisses appeals and refuses pre

rogative writs to review remand orders in criminal civil

rights cases pending on appeal on duly 2, 1001. With till

deference to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit,

its decision is only binding on ihis Court insofar ns its rea

soning is persuasive. Inspection of the Unities opinion dis

closes ( ! ) that the court does not discuss at all the applica

bility to the cases of the Civil Wights Act of 1004, under the

doctrine relied on by appellants here (see Appellants’ Hr.

27-2H); (2) that appellants' argument that former 28

C. S. C. { 1147(d) (1 ‘.la's) did not apply to criminal cases

was not put hoi ore the fourth Circuit or considered by it

(see Appellants' Hr. S 27, .’52 .’S) ; and (.">) that, with re

spect to tlie contention that former i 117(d) did not apply

to civil rights cases, the Fourth Circuit (which writes at

S.<). OS; “ The .Judicial ( ’ode [of 1011] contained nothing

comparable to a of the Act of 1SS7") was not alerted to

the existence of ,207 of the Judicial ('ode, relied on by ap

pellants here (see Appellants' Hr. 21, .‘50-40). Appellants’

arguments were not presented in the briefs in Haines, but

were presented to the Supreme Court of the I ’nited States

in the brie! sueeessfully resisting (Jeorgia's application for

prerogative writs to upset this Court’s stay order in the

present case. Hrief for Wespondents llnehel i f al., in Op

position, tiled in drurt/i'i v. Tuttle | ( l.T. Hid.'!, Mise. Xo.

Idol). St S. ( 't. 1010 ( 1001). In view of the Supreme

Court’s traditional willingness to i--ue prerogative writs

tit the instance of ti State to review the lower federal

/ ? " ’V

\> i , r

/

C On/

1 ;—

; t/

ilritfHtfaSffiiMMfe ■ —■ ynjttn, v. <— A<fai

f

in

<•<»u11̂ im|*»•<»jm r :i sumption ot jurisdiction in criminal ro-

nioval ciim's, l'n*/h/i'i v. /w'r, ,, Kin I'. S. Mid (1S79); I'ir-

V. /’"id. 1 IS r . S. in: (ls<i::) . /{, „/„, !,■;/ v. rol l ers. 201

j r. s. 1 ( 1900); Mnriflatif/ v. Soper (Xo. 1), 270 IT. S.-9

( l0-(»), the stimmary denial ol prohibition here, prior to on-

nctrneiit of the Civil Rights Art of 1904, clearly suggests

that tlie ( ourt found considerable force in tin* arguments

made l»v the present appellants. There is at least enough

in the Supreme Court’s action to justify this Court's con

sideration of those arguments free of the baneful constraint

of the Fourth Circuit’s decision.

Respect fully submitted,

OoN.W.n ],. 1 f01.1,0wi.u,

11nWAim Mi >o|:K, a.

.‘-atlC. Hunter Street, XAV.

Atlanta, (leorgia OOdM

Jack (iiii:KNisr.nr;

10 ( 'olumlms Circle

New York, Xew York 10019

< I

A ntho ny fi. A msttkoam

Kit) ( best II111 Si I’eet

1’hiladelphia, Fa. 19101

-I llniin i/s fur .1 npelltnifs

\ i

^ I

Of ( (I mtficl

M i.i.vyx Z.Kun

A x x ( i ion a

John Qr.wu.rs, ,Tit.

1

I

■****ma&s*W* .;A<S.JVÛ .w--v,a.~i.«U.a. .■,,& ̂ ..- C.M*. ..n. .■.-•̂.Jf

M

Certificate of Scrviop

Thi> is ,u '•‘•>'til'y that on tin. dnv of Soptom-

1"T. I Wt . ! -<• r \ 1 (I copy of ) Ilf fon-sroimr If,.ply B r ie f for

;,pell..i!.‘x upon Ifol,, it Sp.-irl;-. A^ i-tant So lic ito r (,’en-

er;il. Atlanta -1 n. i i, • i a 1 C ircuit, Ifontn fit)], Fulton ( ’ounfy

Court!.un-e llmldintr. Atlanta. C ro rd 'i, A ttorney for Ap-

il,‘,,‘ |’.v ,ll!lili»?' » <*«»py thereof to him nt the above a<l-

(lie>> via l . S. mail, postage prepaid.

.i/Ionia/ for Appellants

« •

AIMMMHX

Oroiir-.i \ ( '<"'i A N NI'T\T1!» '27-901

; r u ! ‘ l ^ v r n ^ n t u . i ! i i y " a n ( l J u h 1.riv il . 'KO Shall c-ontmue

;,..lKm.-nl. Hi.- I~.il miiy- «>

. ........all. ..I' Ha- priit.-i 1*..I ..I " " " ' 10

I.all ........ .. l-.a ................ „,„1 ll.o oomt ►ha 1.

..f,,.,- fin:.I judgment . r - l i f v r 111** ” 1 * .

\ ,• nriiu’ipiil «uul pavilion! ol, 1„. {...ml ui'ini surn-ntlcr <■> 1M ,m MM1 1 *

the ruMs. (Acts 1943, 1*. •>-.)

I

i

\

\

i