Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

July 14, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Brief of Respondent, 1972. 65b3ca77-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c1fbcc5-e05b-4094-b6a7-cb4f16116841/trafficante-v-metropolitan-life-insurance-company-brief-of-respondent. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Copied!

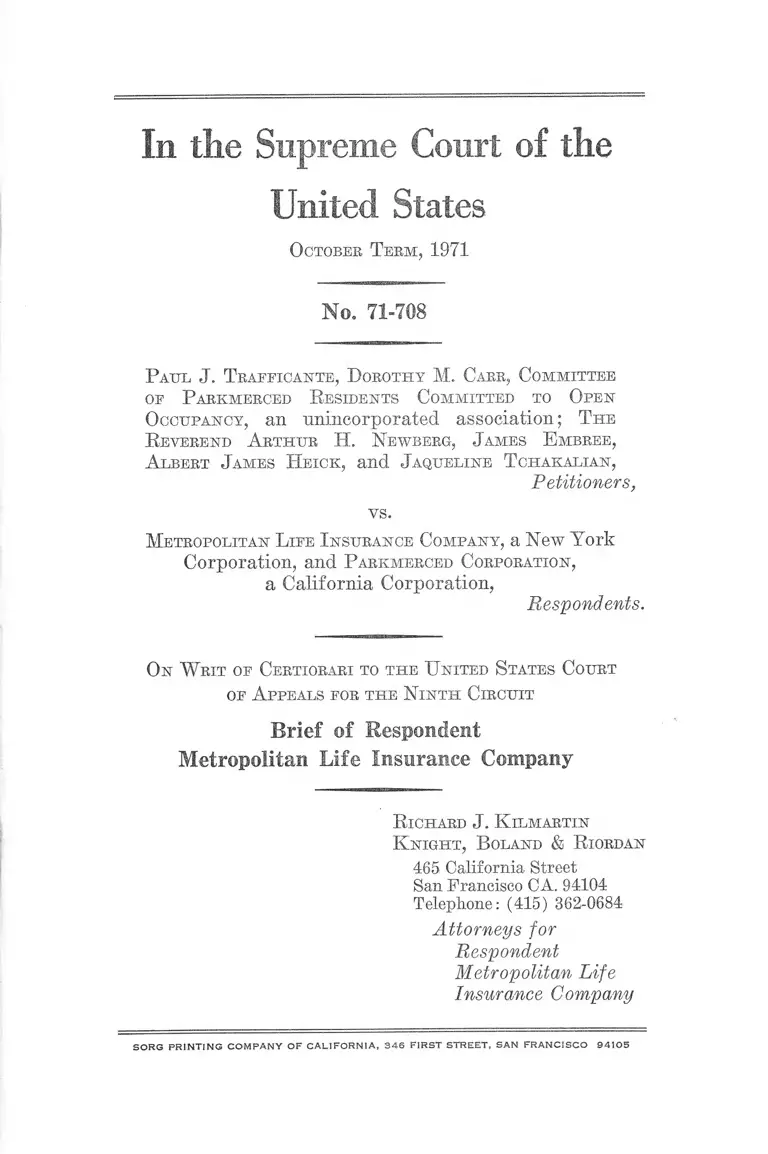

In die Supreme Court of the

United States

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No. 71-708

P a u l J. T raffica n te , D oroth y M. C arr, C om m ittee

of P arkm erced R esidents C om m itted to O pen

O ccu pan cy , ail u n in co rp o ra te d a sso c ia t io n ; T h e

R everend A r t h u r H. N ew berg , J am es E m bree ,

At,be r t J am es H e ic k , and J aq u elin e T c h a k a lia n ,

Petitioners,

vs.

M etropolitan L ife I n su rance C o m p a n y , a New York

Corporation, and P arkm erced C orporation ,

a California Corporation,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ourt

of A ppeals for t h e N in t h C ircu it

Brief of Respondent

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

R ichard J. K ilm a r tin

K n ig h t , B oland & R iordan

465 California Street

San Francisco CA. 94104

Telephone: (415) 362-0684

Attorneys for

Respondent

Metropolitan Life

Insurance Company

S O R G P R IN T IN G C O M P A N Y O F C A L IF O R N IA , 3 4 6 F IR S T S T R E E T , S A N F R A N C IS C O 9 4 1 0 5

SUBJECT INDEX

Opinions B elow ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ..................................... 2

Statutes Involved ....................................... 2

Statement ........................................................................... 2

Summary of Argument........ ................................ -......... 5

Argument ................ ..................- ......... -............................ 6

I Tenants Who Have Not Been the Direct Vic

tims of Any Act Proscribed by the Relevant

Statutes Lack Standing to Challenge Alleged

Acts of Discrimination by Their Landlord

Against Others .................................................... 6

A. The Concept of Standing in This Case..... 6

B. The Injuries Alleged and the Interests

Asserted Are Not Within the Zone of In

terests Protected by the Fair Housing Act 9

C. Petitioners Lack Standing Under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982 .............................................................. 15

D. Petitioner Committee of Parkmerced Resi

dents Committed to Open Occupancy Has

Not Alleged Any Injury to Itse lf.............. 16

E. The Cases Relied Upon by Petitioners Do

Not Support Their Claims to Standing..... 18

F. Administrative Interpretation of Title

VIII .................................................................. 20

G. There Is No Need to Grant Third Parties

Standing to Implement National Policy .... 21

Page

IX Subject Index

Page

II Jurisdiction ................ 24

A. The Federal Court Does Not Have Subject

Matter Jurisdiction Over the Claims As

serted Under the Fair Housing A c t ........... 24

1. Claims Under § 3610 .............................. 24

2. Claims Under § 3612 ............................. 28

B. Under the Circumstances of This Case the

Federal Court Should Abstain from Exer

cising Jurisdiction of the Claims Under

§ 1982 ...................................................... 30

III The Case Is Moot as to Metropolitan.............. 31

Conclusion ........................................................................... 33

Appendices

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

Pages

Adiekes v. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) .............. 18,19

Alameda Conservation Association, et al. v. State of

California, et al., 437 F.2d 1087 (Ca. 9) cert. den.

402 U.S. 928 ........................................ -........................ 32

Alejandrino v. Quezon, 271 U.S. 528 (1926) .............. 32

Association of Data Processing Service Organiza

tions, Inc. v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970) .................. 6, 7, 8

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962) ......................18,19

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ............................... 22

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970).......................... 7

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) .............. 18,19, 21

Brown v. Balias, 331 F.Supp. 1033 (D.C. Tex. 1971) ....12, 23

Brown v. Lo Duca, 307 F.Supp. 102............................. 30

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423 F.2d 57 (CA 5,

1970) ............................... 19

Carter v. Greene County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) ........... 18

Colon v. Tompkins Square Neighbors, Inc., 289 F.

Supp. 104 (S.D. N.Y.) ...........................................27,29,30

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968) ..........................7, 8, 9, 22

Golden v. Zwickler, 394 U.S. 103 (1969) ...................... 32

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 8 8 ............................... 16

Hackett v. McGuire Bros., Inc., 445 F.2d 442 (C.A. 3

1971) ............................................................................. 19

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ...................... 30

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1947) ............................. 16

Johnson v. Decker, 333 F.Supp. 88 (D.C. Ca.) ...........29,30

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .......15,16, 24, 30

Kennedy Park Homes Association, Inc. v. City of

Lackawanna, 318 F.Supp. 669 (1970) aff’d 436 F.2d

108 (C.A. 2 1970) ................................................... . 19

IV Table op A uthorities Cited

Pages

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F.Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970)

ail’d 402 U.S. 935 (1971) ............................................. 20

Marable v. Alabama Mental Health Board, 297 F.

Supp. 291 (N.I). Ala. 1969) .................................... .....18,19

McKee & Co. v. First National Bank of San Diego,

397 F.2d 248 (Ca 9) ............ ....................................... 32

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534

(C.A. 5 1970) ............................... ................. .............. 19

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 .............................. 18

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

400 (1968) ............................. ..................................... 19

Office of Communication of United Church of Christ

v. FCC, 359 F.2d 994 (C.A. D.C. 1966)................ . 19

Powell v. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486 (1969).................. 32

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 ................................... 26

Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. FPC, 354

F.2d 608 (C.A. 2 1965) ................................................ 19

Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (C.A. 3 1970) .............. 19

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1947) ................. ...... 19

Sierra Club v. Morton, 92 S.Ct. 1361 (1972) ....... 7, 8,14,17

18,19, 22

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134 (1944) ........................ 20

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) ..18,1.9

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S. 448

(1957) .................................................. ........................ 32

United States of America v. Alaska Steamship Com

pany, 253 U.S. 113 (1920) ......................................... 31

United States of America v. W. T. Grant Company,

345 U.S. 629 (1953) .................................................... 31, 32

Table of A uthorities Cited v

Pages

United States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export

Association, Inc., 393 U.S. 199 (1968) ...................... 31

Yargas v. Hampson, 57 C.2d 479; 20 Cal. Rptr. 618;

370 P.2d 322 ................................................................. 26

Walker v. Pointer, 304 F.Snpp. 56 (W.D. Tex. 1969) .. 18

S tatutes

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ........................................................ 1

42 U.S.C.:

§ 1982 ...............................................2, 3, 4, 5, 6,15,16, 21, 30

§ 3601 .................................................................. ..........24, 25

§ 3601 et seq.................................................................. 2

§ 3604(a), (b) and (d) ................................................. 11

§§ 3604, 3605, 3606 ........................................................ 25

§3608, 3611 .................................................................. 11

§ 3610 ...................... .......................................................24, 25

§ 3610(a) ....................................................................... 11,25

§ 3610(d) ................................... 2, 6,11, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

§ 3610 and 3612 .........................................3, 4,11,12, 28, 30

§ 3612 ................................................................. 11,12, 25, 28

§ 3613........ 11

California Civil Code, §§51 and 5 2 ............................. 2, 26

California Health and Safety Code:

§ 35700, et seq................................

§ 35720 ...........................................

§ 35731 ...........................................

§ 35732 ..........................................

§ 35734 ...........................................

§ 35738 ...........................................

§§ 35730 and 35738 ........................

§§ 35734, 35738 ...............................

Government Code § 11523 ..............

Labor Code § 1428 ..........................

6, 25

25

.25, 26

25

25

25

26

25

26

26

O th ers Page

82 Harvard Law Review 834 ......................................... 28

114 Cong. Rec.:

4987 ................................................... 27

5514 ............................................................................... 12

5515 ................................................................... 13

9560 ................................. 14

9600 ......... 13

9612 ......................................................................... 29

vi Table of A uthorities Cited

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No. 71-708

P a u l J. T raffican te , D orothy M. Carr, Com m ittee

of P arkm erced R esidents C om m itted to O pen

O ccu pan cy , an u n in corp ora ted a sso c ia t io n ; T he

R everend A rt h u r H . N ew berg , J am es E m bree ,

A t.bf.rt J am es H eicik, and J aqu elin e T c h a k a lia n ,

Petitioners,

vs.

M etropolitan L ife I nsurance C o m p a n y , a New York

Corporation, and P arkm erced C orporation ,

a California Corporation,

Respondents.

O n W rit of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ourt

of A ppeals for t h e N in t h C ircu it

Brief of Respondent

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

O PIN IO N S BELOW

Tlie opinion of the District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of California (Appendix A hereto) dismissing the

Complaint and Complaint in Intervention is reported at 322

F.Supp. 352 (N.D. Cal. 1971). The opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (Appendix A of Petitioner’s

Brief) affirming the Judgment of Dismissal is reported at

446 F.2d 1158.

JURISDICTION

The Judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit was entered on August 6, 1971. On September 13,

1971, the Court of Appeals denied a timely petition for

rehearing en banc. A copy of the Order is attached hereto

as Appendix B. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

QUESTIO N S PRESENTED

1. Do tenants of an apartment complex against whom

no aet of discrimination has been practiced and none of

whom have been deprived of the right to rent or lease real

property have standing under the Fair Housing Act (Title

VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968; P.L. 90-284, 42 U.S.C.

§ 3601 et seq.) or 42 U.S.C. § 1982 to maintain an action

against their former or present landlord for alleged acts

of discrimination against others ?

2. Does the Federal conrt lack subject matter jurisdic

tion of Petitioner’s claims under the Fair Housing Act by

reason of 42 U.S.C. § 3610(d) ?

3. Is the case moot as to respondent Metropolitan Life

Insurance Company (“ Metropolitan” ) by reason of its sale

of Parkmereed?

STATUTES INVOLVED

The statutes involved are:

1. Title VIII (Fair Housing) of the Civil Rights Act

of 1968 (P.L. 90-284; 42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq.)

2. 42 U.S.C. § 1982.

3. California Health and Safety Code §§ 35700, 35720,

35731, 35732, 35734, and 35748.

4. California Civil Code §§51 and 52.

These statutes are set forth in Appendix C hereto.

STATEMENT

This action arises under the Fair Housing Act (Title

VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968) and 42 U.S.C. § 1982.

Parkmerced is a 3500 unit garden and tower apartment

complex located on approximately 150 acres in the south

west portion of San Francisco. It is immediately contiguous

to or near hundreds of privately owned single family

residences, San Francisco State College, other unrelated

2

3

apartment complexes and several shopping areas. Com

menced in the early 1940’s and completed in the early

1950’s, it was entirely constructed with private capital by

Metropolitan which owned and operated it until December

21, 1970.1 On that date Metropolitan sold the buildings and

leased the land for a period of 30 years, with three 15-

year renewal options, to Parkmerced Corporation in a

bona fide, arm’s-length business transaction. Metropolitan

has no ownership interest whatever in Parkmerced Cor

poration and from and after the date of sale was divested

of all right to manage, control or otherwise operate the

project including the rental of apartment units. It has had

no employees engaged in Parkmerced’s operations since the

sale (R. Ex. K).

At the time of the commencement of this action, each

petitioner was a resident and tenant at Parkmerced.2 3 Since

the Order attacked by petitioners is an Order dismissing

the Complaint and Complaint in Intervention, the facts

under review are the allegations of the complaints.® The

Complaint contains three causes of action, the first and

second being based upon §§ 3610 and 3612, respectively, of

the Fair Housing Act, and the third upon 42 U.S.C. § 1982.

1. Parkmerced was one of seven projects built and financed by

Metropolitan for the purpose of providing middle income housing

in park-like setting’s in urban areas. The others were Parkchester

in the Bronx; Riverton in Harlem; Stuyvesant Town and Peter

Cooper Village in Mid-Manhattan; Park Fairfax in Alexandria;

and Pa.rklabrea in Los Angeles.

2. Except the Committee of Parkmerced Residents Committed

to Open Occupancy. The Committee is alleged to be an unincorpo

rated association, all of the members of which are residents of Park

merced. The number or identity of members of the Committee is

not disclosed by the record. Since the commencement of the action,

all of the individual plaintiffs in intervention have moved from

Parkmerced, and petitioner Carr has publicly announced her inten

tion to do so.

3. The Affidavit of Alvin F. Poussaint (R. Ex. I) is not part

of the complaints. It was filed in the District Court by petitioners

in opposition to Respondents’ Motions to Dismiss.

4

Each cause of action alleges that petitioner Trafficante is a

Caucasian and petitioner Carr a Negro; that both are ten

ants of and reside at Parkmerced; upon information and

belief only, that Metropolitan has “ for many years” prior

to the filing of the complaint discriminated against minority

groups in rental practices; and that prior to the commence

ment of the action the petitioners filed complaints with the

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (“H.U.D.” ),

pursuant to the provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 3610, which were

not resolved. The Complaint in Intervention is virtually

identical to the causes of action of the Complaint based

upon 42 U.S.C. § 3612 and 42 U.S.C. § 1982. All petitioners

assert that by reason of the alleged discrimination they have

been deprived of certain social, business and professional

benefits.

Neither the Complaint nor the Complaint in Intervention

contain any allegation that the petitioners, or any of them,

have themselves been deprived of housing or any right

guaranteed them by the Fair Housing Act or 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982. The complaints are also devoid of any allega

tion that respondents have denied or interferred with the

free access to Parkmerced of any person seeking business

or social contact with plaintiffs; or interfered with plain

tiffs’ business or social activities with any person; or cur

tailed any service to plaintiffs because of their activities,

guests, or business invitees; or otherwise interferred with

plaintiffs’ right of free inter-racial association.

Upon motion of Respondents4 the District Court, on

February 10, 1971, dismissed the action upon the ground

that petitioners were not persons aggrieved under the rele

vant statutes and were without standing to maintain the

action.

4. Immediately after the sale of Parkmerced the purchaser,

Parkmerced Corporation, was joined as a defendant in the action.

On February 25, 1971, petitioners’ attorneys filed a Com

plaint entitled Charles Burbridge (et al.) vs. Parkmerced

Corporation and Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

(U.S.D.C. N.D. California No. 71 378), a copy of which is

Appendix 1) hereto. That case is now pending. The defend

ants have answered, and discovery procedures are being

pursued. The plaintiffs, all Negroes, allege that they are

the direct victims of discriminatory housing practices which

resulted in their exclusion from Parkmerced and according

ly their standing to maintain the action has not been chal

lenged. Reference to Burbridge will be made further in

this brief.®

The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit unanimously

affirmed the District Court noting, as had the District

Court, that the plaintiffs had not alleged, “nor can they

that they themselves have been denied any of the rights

granted by Title VIII or by 42 U.S.C. § 1982 to purchase or

rent real property.” Both Courts held squarely that the

“ interests” and “ injuries” alleged in the Complaint were

not the interests and injuries contemplated by the Fair

Housing Act or § 1982 and concluded that petitioners were

without standing to maintain the action. Neither Court

reached the jurisdictional or mootness question.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Respondents contend that the purpose of the Fair Hous

ing Act was to make housing available to all persons without

discrimination based on race, color, religion or national

origin. To effect that policy and purpose, Congress specif-

icallv defined acts which it declared to be unlawful and

provided a comprehensive scheme of remedies to any person

who had been denied housing in violation of the Act. 5

5

5. Infra p. 22

The Act does not contemplate this type of action or provide

redress for the “ injuries” asserted. Petitioners are not the

intended beneficiaries of the Act.

Similarly, petitioners are not within the class of persons

afforded protection by 42 U.S.C. § 1982 since they6 7 have

not been denied the right to lease property.

In addition to petitioners’ lack of standing, the Federal

Court lacked subject matter jurisdiction of the claims

predicated on the Fair Housing Act by virtue of 42 U.S.C.

§ 3610(d) which prohibits federal jurisdiction if a State or

local fair housing law provides substantially equivalent

rights and remedies as the Fair Housing Act and contains

a judicial remedy. California’s Rumford Act6 and Unruh

Civil Rights Act7 provide such rights and remedies.

Finally, the case is moot as to respondent Metropolitan

by reason of its sale of Parkmerced. Metropolitan no longer

controls any aspect of the operation at Parkmerced and it

would be idle for a court to enter an injunction against

it. The damage claims asserted do not save the case from

the doctrine of mootness because they are not cognizable

under the statutes involved.

ARGUM ENT

I

TENANTS W H O HAVE NOT BEEN THE DIRECT VICTIMS OF ANY

ACT PROSCRIBED BY THE RELEVANT STATUTES LACK

STANDING TO CHALLENGE ALLEGED ACTS OF DISCRIM

INATION BY THEIR LANDLORD AGAINST OTHERS

A. The Concept of Standing in this Case.

The cases involving the issue of standing are legion, hut

the final formula for standing in this case may be extracted

from Association of Data Processing Service Organizations,

6. Cal. Health & Safety Code §35700, et seq.

7. Cal. Civ. Code §51, et seq.

6

Inc. v. Cam.p, 397 U.S. 150 (1970); Barlow v. Collins, 397

U.S. 159 (1970); Sierra Club v. Morton, 92 S.Ct. 1361

(1972); and Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968). In Data

Processing and Barlow this Court granted standing to

obtain judicial review of governmental agency action where

the petitioners themselves had suffered direct economic

injury and were clearly persons aggrieved within the mean

ing of the Administrative Procedure Act. In Data Process

ing it was held (pp. 151,153) :

“ Generalizations about standing to sue are largely

worthless as such. One generalization is, however,

necessary and that is that the question of standing in

the federal courts is to be considered in the framework

of Article III which restricts judicial power to ‘eases’

and ‘controversies.’

# * * # #

“ * # * [The question of standing] concerns, apart

from the ‘case’ or ‘controversy’ test, the question

whether the interest sought to be protected by the

complainant is arguably within the zone of interests

to be protected or regulated by the statute or consti

tutional guarantee in question. Thus the Administra

tive Procedure Act grants standing to a person ‘ag

grieved by agency action within the meaning of a

relevant statute.’ ”

and (p. 154):

“ Apart from Article III jurisdictional questions,

problems of standing, as resolved by this Court, have

involved a ‘rule of self-restraint for its own govern

ance.’ Barrows v. Jackson, 346 US 249. Congress can,

of course, resolve the question one way or another,

save as the requirements of Article III dictate other

wise. Muskrat v. United States, 219 US 346.”

Subsequently, in Sierra Club this Court affirmed that the

“ injury in fact” element necessary to satisfy Article III

requirements for standing could be of a noneconomic na-

7

8

tore provided toe party seeking review had himself suffered

an injury to a “ cognizable interest” (p. 1366) and had a

“direct stake in toe outcome” (p. 1369; emphasis added).

The Court however denied standing to purely “ special

interest” organizations which had not alleged cognizable

injury to itself, and observed (p. 1368):

“ The requirement that a party seeking review must

allege facts showing that he is himself adversely af

fected does not * * * prevent any public interests from

being protected through the judicial process. It does

serve as at least a rough attempt to put the decision as

to whether review will be sought in the hands of those

who have a direct stake in the outcome. That goal would

be undermined were we to construe the relevant stat

ute to authorize judicial review at the behest of organi

zations or individuals who seek to do no more than

vindicate their own value preferences through toe

judicial process.” (Emphasis added)

In Flast the Court had previously summarized (pp. 99,100):

“ In other words, when standing is placed in issue in

a case, the question is whether the person whose stand

ing is challenged is a proper party to resquest an ad

judication of a particular issue and not whether the

issue itself is justiciable.”

Under those holdings it is not sufficient that petitioners

advance merely any injury or interest but they must assert

an injury which is “ cognizable” (Sierra Club at 1366) and

“ arguably within the zone of interests to be protected or

regulated by the statute” (Bata Processing at 153). Peti

tioners satisfy neither requirement but respondent believes

that in the context of this case the “ injury in fact” element

necessary to satisfy Article III ‘case’ or ‘controversy’

requirements and the “ zone of interests” test are so in

separably interwoven that an attempt to dissect and treat

them separately or independently would be an exercise in

futility. Thus, if petitioners have not alleged an injury

cognizable under the relevant statutes they are not within

the zone of interests sought to be protected by the statutes.

Conversely, if they are not within the zone of interests to

be protected by the statutes they have not suffered a cog

nizable injury.8

B. The Injuries Alleged and the Interests Asserted Are Not With

in the Zone of Interests Protected by the Fair Housing Act.

The petitioners’ “ injuries” are alleged to be :

“ (a) plaintiffs are deprived of the social benefit of

living within a community which is not artificially im

balanced in a manner which excludes minority group

members;

“ (b) plaintiffs suffer the loss of business and pro

fessional advantages which accrue from contact and

association with minority group members;

“ (e) plaintiffs are stigmatized within both the white

and minority group communities as residents of a

segregated ‘white ghetto’, causing such residents both

embarassment and economic damage in social, business

and professional activities.” (It. Ex. A at 5 and Ex. B

at 5; Pet.App. C at 5.)

An examination of the Fair Housing Act is necessary to

determine whether the injuries and interests asserted are

within the purview of the statutes involved and whether,

consequently, the petitioners have or lack standing. The Act

itself defines the rights that it creates and protects, the

injuries it prohibits, and persons aggrieved by its violation.

In relevant parts it provides:

“ § 3610. (a) Any person who claims to have been

injured by a discriminatory housing practice or who

believes that he will be irrevocably injured by a dis

8. Compare this Court’s statement in Mast v. Cohen (p. 95)

that: “ Thus, no justiciable controversy is presented when # * #

there is no standing to maintain the action. ’ ’

9

10

criminatory housing practice that is about to occur

(hereafter ‘person aggrieved’) may file a complaint

with the Secretary.

“ (d) * * * the person aggrieved may, within thirty

days thereafter, commence a civil action in any appro

priate United States district court, against the respond

ent named in the complaint, to enforce the rights

granted or ‘protected by this subchapter, insofar as

such rights relate to the subject of the complaint: * * *”

“ § 3602. As used in this title—

^

“ (f) ‘Discriminatory housing practice’ means an act

that is unlawful under section 3604, * #

“ § 3604. As made applicable by section 3603 and

except as exempted by sections 3603(b) and 3607, it

shall be unlawful—

“ (a) To refuse to sell or rent after the making of a

bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale or

rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a

dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion,

or national origin.

“ (b) To discriminate against any person in the

terms, conditions, or privileges of sale or rental of

a dwelling, or in the provision of services or facilities

in connection therewith, because of race, color, religion,

or national origin.

# # # =K=

“ (d) To represent to any person because of race,

color, religion, or national origin that any dwelling is

not available for inspection, sale, or rental when such

dwelling is in fact so available.”

“ § 3612. (a) The rights granted by sections * * *

3604 * * * may be enforced by civil actions in appropri

ate United States district courts without regard to the

amount in controversy and in appropriate State or

local courts of general jurisdiction.” (Emphasis added)

Read in context it is clear that petitioners are not and were

not intended to be, persons aggrieved within the meaning

11

of § 3610(a). As tenants and residents of Parkmerced, none

of the acts proscribed by § 3604(a), (b) and (d) have been

practiced against them, nor have they been deprived of any

of the rights specifically defined by § 3604 which could

be the subject of enforcement action under § 3610(d) or

§ 3612.® The rights granted by § 3604 which are enforceable

under §§ 3610 and 3612 are not the rights asserted by peti

tioners but the right to obtain housing free of discrimina

tion. This personal right is directly enforceable only by

the person to whom given.9 10 11 Many parts of the Fair Housing

Act compel this conclusion. For example, a person claiming

to have been injured by a discriminatory housing practice

may file an administrative complaint with the Secretary

(§ 3610(a)); the complaint must be filed within 180 days

after the specific acts complained of occur (§ 3610(b)); the

complaint filed with the Secretary must state the specific

facts upon which it is based (§ 3610(b)) ;X1 an action under

§ 3610(d) must be filed within thirty days after the Secre

tary is unable to resolve the administrative complaint

(§ 3610(d)); an action under §3612 must be filed within

180 days of the occurrence of the alleged discriminatory

housing practice or be barred (§ 3612(a)); and federal

administrative assistance is available to persons aggrieved

(§§ 3608, 3611). Many parts of the Act, including the specific

and exact time limitations for seeking redress, become

9. While the language of § 3612 is arguably narrower than that

of § 3610, respondent does not contend that different tests of stand

ing'are applicable under the two sections. Rather, the precise word

ing of § 3612 reinforces the conclusion that in providing enforce

ment machinery Congress intended to provide remedies only for the

direct victims of discriminatory housing practices.

10. In a broader sense the Pair Housing Act is enforceable by

the Attorney General under § 3613.

11. Compare the complaint, the charging allegations of which

are based upon information and belief only (R. Ex. A at 2, 3; Pet.

Br. App. C at 2, 3) ; and Ex. A and B to Complaint which state no

facts whatever.

12

meaningless if third parties who have not been deprived

of any of the rights created by the Act are allowed to main

tain an action such as this. § 3610 does not provide for an

award of damages (Brown v. Balias, 331 F.Supp. 1033

(D.C. Tex. 1971) but its injunctive and affirmative action

provisions are obviously designed only to obtain housing

for persons who have been discriminated against. Similarly,

the provisions of § 3612 authorizing an award of damages,

costs and attorney’s fees clearly contemplate redress of an

injury inflicted upon a person who has been wrongfully

denied housing.

The congressional history of the Fair Housing Act is

replete with indications that Congress intended actions

under § 3610 and § 3612 only by the direct victims of a

discriminatory act. In a discussion of costs and attorney’s

fees in the Senate, Senator ITart stated pointedly:

“ Mr. President, I think it important to note that

Section 212(b) and (c) as those provisions now stand

do reveal a clear congressional intent to permit, and

even encourage, litigation by those who cannot afford

to redress specific wrongs aimed at them because of

the color of their skin. Of course a court must judge

what fees are appropriate, as well as what damages

may apply, but this Section should not be read as

permitting courts to deny costs solely at its discretion.

We cannot prevent unwitting enforcement of this pro

vision to shut the courthouse doors to those whose

rights are violated simply because they lack the funds

to protect those rights."12 (Emphasis added.)

Similarly, the following colloquy occurred in a discussion of

§ 3612:

Senator Mondale:

“As I understand the intent of the amendment, as

modified, offered by the Senator from Colorado [Mr.

12. 114 Cong. Bee. at 5514

Allott] it is this: when a person really wants to rent

a particular leasehold or when he wants to buy a par

ticular piece of property, he is clearly within the pro

tection of this measure. But when the offer is in effect

a phony one, when he has no intention, when it is not

a good safe offer, because he is on a lark or whatever,

when it is a contrived sort of situation with which he

would never go through, he would not be protected.”

Senator Allott:

“I think that bona fide means a man has to be ready,

willing and able to perform. Without these three ele

ments it would not be a bona fide offer capable of

enforcement if accepted.18

Speaking of the Act generally, Representative Corman

observed:

“It would assure that anyone who answered an

advertisement for housing not be turned away on the

basis of his race.”13 14

On April 10,1968, the date the Act was passed in the House

of Representatives, Representative Celler commented:

“ A person aggrieved files his complaint within 180 days

after the alleged acts of discrimination. The Secretary

of Housing and Urban Development would have 30

days after filing of the complaint to investigate the

matter and give notice to the person aggrieved whether

he intended to resolve it. * * * If conciliation failed, or

if the Secretary declined to resolve the charge or other

wise did not act within the 30-day period, the aggrieved

person would have 30 days in which to file a civil

action in either a State or Federal court.

̂ ̂ ̂ ^

“ The bill further provides that any sale, encumbrance,

or rental consummated prior to a court order issued

13

13. 114 Cong. Rec. at 5515.

14. 114 Cong. Rec. at 9600.

under this act and involving a bona fide purchaser,

encumbrancer, or tenant, shall not be affected.”15

These statements are only a few from many expressed in

varying contexts. The theme central to all discussions, how

ever, was the dignity of man, his right to housing and

equal treatment regardless of the color of his skin, and

the guarantee of those rights to him. Nowhere did either

the Senate or the House express any concern whatever for

the enhancement of the business and social activities of

any third persons, including tenants. The discussions fail

to disclose any intent on the part of Congress to grant

standing to sue to any but the direct victims of discrim

inatory housing practices and the Attorney General.

Similarly, there is no indication whatever in either the

Act itself or its congressional history that Congress in

tended to require private landlords to enter into meaning

less and inconclusive injunctive or damage litigation with

any tenant who happened to disagree with the landlord’s

business practices, procedures or social views, nor to sub

ject private landlords to the possible harassment of a multi

tude of lawsuits which would be binding upon no one. If

upon a trial petitioners, who sue in their right alone, were

denied the relief they seek, the judgment would not and

could not be binding upon the next group of plaintiffs

asserting a real or imagined grievance. On the other hand,

if any measure of relief was granted by a court the extent

of the judgment would not and could not be binding or

conclusive upon persons not parties to the action. Hence,

any third person16 being dissatisfied with the result could

commence another action to attempt to implement his views

or to “vindicate [his] own value preferences” (Sierra Club

15. 114 Cong. Ree. at 9560.

16. Parkmereed alone houses over 8000 persons (R. Ex. A at 2).

14

at 1369). Further, the specter of a person obtaining housing

through the administrative or judicial process followed

immediately by a claim for damages against his new land

lord for injuries allegedly being suffered as a result of

living in a segregated community would be an exercise in

circuity devoid of logic and contrary to the ennobling pur

pose of the statutes. Such profound disorder could not only

not have been contemplated by Congress but is totally

unnecessary to achieve the purpose of the Act.17 The

injuries and interests asserted are simply not those con

templated by the Fair Housing Act. Petitioners are not

therefore persons aggrieved within the meaning of the Act

and their noneognizable injuries cannot be made the sub

ject of an action for damages.

C. Petitioners Lack Standing Under 42 U.S.C. § 1982.

Petitioners’ lack of standing under § 1982 is patent. In

concise terms that section provides:

“All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by

white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell,

hold, and convey real and personal property.”

In interpreting the statute this Court, in Jones v. Mayer

Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), stated (p. 420):

“We begin with the language of the statute itself.

In plain and unambiguous terms, § 1982 grants to all

citizens, without regard to race or color, ‘the same

right’ to purchase and lease property ‘as is enjoyed by

white citizens.’ ”

Petitioners do not and cannot fall within the purview of

that statute. Obviously none has been denied the right to

lease real property. Consequently, they have suffered no

15

17. Infra at 28.

“ injury in fact” at all, nor can their claims fall “ arguably

within the zone of interests to be protected * * * by the

statute.” The entire rationale of Jones v. Mayer Go. is

inimical to the status petitioners represent and does not

remotely purport to grant them standing. In fact, all of the

implications of Jones are directly to the contrary. Quoting

its earlier decision in Hurd v. Hodge, 334 TJ.S. 24 (1947),

this Court stated (p. 419):

“Hurd v. Hodge, supra, squarely held, therefore,

that a Negro citizen who is denied the opportunity to

purchase the home he wants ‘ [sjolely because of [his]

race and color,’ 334 U.S., at 34, has suffered the hind of

injury that § 1982 was designed to prevent.” (Emphasis

added.)

The entire thrust of Jones was the protection of the rights

of Negroes to purchase or lease property. Indeed, the

constitutionality of § 1982 was predicated upon its attempt,

as authorized by the Thirteenth Amendment, to abolish

a “badge of slavery” . The kind of injury that § 1982 was

designed to prevent is simply not present in this case.18

16

D. Petitioner Committee of Porkmerced Residents Committed

to Open Occupancy Has Not Alleged Any Injury to Itself.

What has been said heretofore applies with equal force

to all petitioners. There is, however, an additional fatal

defect in the complaint in intervention filed by the Com

mittee of Parkmerced Residents Committed to Open Occu

pancy (“ Committee” ).

18. The contention of the United States that to the extent peti

tioner Carr claims to be a victim of tokenism her complaint is with

in the terms of § 1982 (Brief of United States, n. 36 at 20 is

neither suggested nor supported by Jones v. Mayer Go. or Griffin v.

Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 in both of which the plaintiff was the

direct victim of a specific offense. Further, the claim of “ tokenism”

attributed to petitioner Carr does not appear in her complaint.

It is alleged that the Committee is “ an unincorporated

association of Caucasian and Negro individuals who are

residents of Parkmerced committed to correction of the

racial imbalance presently existing at Parkmerced” (R. Ex.

B at 2). But the only injuries allegedly suffered by the

Committee are the same loss of social, business and pro

fessional benefits alleged by the individual plaintiffs.19 In

Sierra Club this Court held (p. 1366):

“ But the ‘injury in fact’ test requires more than an

injury to a cognizable interest. It requires that the

party seeking review be himself among the injured

17

and (p. 1368):

“But a mere ‘interest in a problem,’ no matter how

longstanding the interest and no matter how qualified

the organization is in evaluating the problem, is not

sufficient by itself to render the organization ‘adversely

affected’ or ‘aggrieved’ within the meaning of the

[relevant statute]. The Sierra Club is a large and long-

established organization, with an historic commitment

to the cause of protecting our Nation’s natural heritage

from man’s depredations. But if a ‘special interest’ in

this subject were enough to entitle the Sierra Club to

commence this litigation, there would appear to be no

objective basis upon which to disallow a suit by any

other bona fide ‘special interest’ organization, how

ever small or short-lived. And if any group with a

bona fide ‘special interest’ could initiate such litigation,

it is difficult to perceive why any individual citizen with

the same bona fide special interest would not also be

entitled to do so.”

The holding in Sierra Club was premised upon lack of an

allegation of injury to the Sierra Club itself or an individ

ualized injury to any of its members. The Committee in this

19. Supra at 13.

case thus appears to be a “ special interest” group formed

for the sole purpose of correcting an alleged racial imbal

ance at Parkmerced. As such, it has not and cannot have

suffered the only “ injuries” which are alleged. Further, as

in Sierra, there is no allegation whatever that the individual

members of the Committee have suffered any “ injury in

fact.”20

E. The Cases Relied Upon by Petitioners Do Mot Support Their

Claims to Standing.

Since Congress has designated the persons entitled to file

actions under the Fair Housing Act, it is unnecessary to

consider a host of authorities in which standing or lack of

standing was determined by nonstatutory standards or the

phrase “person aggrieved” was not defined. Similarly, the

clear lack of any cognizable injury to or interest in peti

tioners makes it unnecessary to consider what injury or

interest would qualify to grant standing under § 1982. But

it should not go unsaid that the cases principally relied

upon by petitioners do not grant or purport to grant

standing to them. In each such case the plaintiff was

clearly the person directly aggrieved and had a cognizable

interest in the subject matter of the action.

Thus, in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229

(1969) , Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953), Carter v.

Greene County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970), Bailey v. Patterson,

369 U.S. 31 (1962), Aclickes v. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144

(1970) , Marable v. Alabama Mental Health Board, 297

F. Supp 291 (N.D. Ala. 1969) and Walker v. Pointer, 304

F.Supp. 56 (W.D. Tex. 1969), the plaintiff was the person

against whom an act of discrimination had been directly

20. The Committee’s status is unlike that of the petitioner in

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, wherein the Court granted

standing to a corporation which had alleged direct injuries to itself,

its purpose and its functions, as well as injury to its members.

18

practiced. In Sullivan the plaintiff himself had been expelled

from a corporation because he had leased Ms residence to a

Negro and accordingly was granted standing to maintain an

action for damages to himself. In Barrows the defendant

was accorded the right to assert the doctrine of Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1947) on Ms own behalf as a defense

to an action for damages against him. (The Court there

reiterated the rule that one may not claim standing to

vindicate the rights of another but held that the contem

plated action of a State Court could result in a denial to

the defendant of his own constitutional rights.) In Carter

the plaintiffs had been unlawfully excluded from jury serv

ice. The petitioners themselves in Bailey had been denied

nonsegregated treatment, while in Adickes the plaintiff had

been refused service in the defendant’s restaurant facili

ties and had been arrested upon her departure from the

defendant’s store. The plaintiffs in Marable were the direct

victims of the practices complained of and in Walker were

the persons actually evicted from rented property in viola

tion of their own rights.

Similarly, in Newman v. Biggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 (1968), Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

426 F.2d 534 (C.A. 5 1970), Blackett v. McGuire Bros., Inc.,

445 F.2d 442 (C.A. 3 1971) and Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc.,

423 F.2d 57 (CA 5, 1970) the plaintiff was the person

against whom an act of discrimination had been directly

practiced and the action was authorized by a specific statute.

Finally, this case does not present any challenge to

governmental administrative agency action as in Scenic

Hudson Preservation Conference v. FPC, 354 F.2d 608

(C.A. 2 1965), Shannon v. IIUD, 436 F.2d 809 (C.A. 3 1970),

Kennedy Park Homes Association, Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 318 F.Supp. 669 (1970) aff’d 436 F.2d 108 (C.A. 2

1970), Office of Communication of United Church of Christ

19

v. FCC, 359 F.2d 994 (C.A. D.C. 1966), and Lee v. Nyquist,

318 F.Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970), aff’d 402 U.S. 935 (1971).

In each of those cases the plaintiff, who was the person

directly aggrieved, was granted standing to challenge

administrative action of a government agency in order to

assure its regularity and compliance with the Constitution

or pertinent statutes or regulations.

None of the eases cited by petitioners, including Civil

Rights cases, grant standing to sue to any except the direct

victims of the discriminatory practice complained of and

they are not therefore germane to the issue of standing in

this case.

F. Administrative Interpretation of Title VIII.

Respondent acknowledges that an administrative inter

pretation of an Act by an agency charged with its enforce

ment is entitled to consideration. The consideration, how

ever, is subject to the limitation imposed by this Court in

Skidmore v. Swift, 323 U.S. 134 (1944), that (p. 140):

“ The weight of [an administrative determination] in

a particular case will depend upon the thoroughness

evident in its consideration, the validity of its reason

ing, its consistency with earlier and later pronounce

ments, and all those factors which gave it power to

persuade if lacking power to control.”

In this case, the “ determination” by an employee of

H.U.D. that petitioners have standing (Pet. Br. at 21)

is entitled to no weight at all. This gratuitous unarticu

lated conclusion, which is directly contrary to that of

the District Court and the Ninth Circuit Court of

Appeals, made only in a letter to petitioners’ attorneys

while the case ivas pending in District Court cannot even be

deemed a semi-official declaration of the Department.

20

21

The desire of the Department of Justice for assistance,

upon which its interpretation of the statutes appears pri

marily based, is understandable, but denial of standing to

petitioners will in no way detract from the assistance

legitimately available to it. Respondent asks only that any

action filed against it be brought and prosecuted by a

proper plaintiff with a cognizable grievance in a proceed

ing that will terminate on a final and conclusive note.

Neither the need for assistance nor the size of the Depart

ment’s Civil Rights staff can confer or create standing

where none exists. The “ private Attorney General” con

cept will not be undermined in the slightest degree by a

denial of standing to these petitioners.

G. There Is No Need to Grant Third Parties Standing to Imple

ment National Policy.

Citing Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 259 (1953),

petitioners and amici curiae contend that somehow ten

ants may be the only or most effective adversaries to

challenge discriminatory practices of a landlord. This con

tention is somewhat of an indulgence in naivete for it is

well known that suits such as this are backed by persons

or groups active in the movements they represent. If indeed

any discriminatory housing practices have occurred on the

scale asserted, or on any scale, it imposes no undue burden

or hardship whatever to prosecute the action in the name

or names of the victims of the discrimination. Unlike this

case, the issues in such an action would be real, live and

subject to rebuttal or settlement. The exact contrary is

true when the action is brought by third persons who have

not been the victims of an unlawful act. Thus, there is

no way to resolve the dispute by providing housing to the

person offended, the primary objective and purpose of the

Fair Housing Act and § 1982. Instead, the action would

inevitably devolve into one of “ value preferences” (ef.

Sierra Club v. Morton at 1369) in which the plaintiff tenant

would attempt to substitute his judgment for that of his

landlord.

The ready availability of 'proper plaintiffs was demon

strated by occurrences related to this case. On February 25,

1971—fifteen days after the District Court dismissed this

action—petitioners’ counsel commenced an action entitled

“ Burbridge v. Parkmerced Corporation and Metropolitan

Life Insurance Company.” A copy of the complaint in that

action is Appendix D hereto. The plaintiffs there, all

Negroes, allege that they have been the direct victims of

discriminatory housing practices which resulted in their

exclusion from Parkmerced. The charging allegations are

otherwise virtually the same as in this case. The very filing

and pendency of that case dissolves and demonstrates the

fallacy of the notion that somehow tenants may be the only

or most appropriate persons to enforce fair housing laws.

Notwithstanding Burbridge, resident tenants are perhaps

the least desirable persons to attempt implementation of

the national policy of fair housing. They would lack the

“ personal stake in the outcome of the controversy” (Baker

v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 204 (1962)) which would ensure

that “ the dispute * * * will be presented in an adversary

context and in a form historically viewed as capable of

judicial resolution” (Blast v. Cohen, supra). Each would be

necessarily dedicated to his own personal social views rather

than to a fair and orderly effectuation of the statutes in

volved. Further, the inherent transiency of residential ten

ancies robs tenants of the qualities requisite to standing.

The facts of this case provide a compelling lesson in this

regard. As heretofore noted (n. 2 p. 6), every individual

plaintiff in intervention has moved from Parkmerced and

one plaintiff is about to move. Even under their own

theories of standing they now have neither a personal stake

in the outcome of the controversy nor a cognizable—or

22

perhaps any—interest in the subject matter of the com

plaint.21

Finally, it is totally unnecessary to grant standing to

petitioners to implement the enforcement features of the

statutes. Private enforcement by proper plaintiffs is

expressly authorized. Additionally, Congress has specific

ally authorized the Attorney General, and only the Attorney

General, to maintain this type of “pattern or practice” case.

§ 3613 of the Fair Housing Act provides:

“Whenever the Attorney General has reasonable

cause to believe that any person or group or persons

is engaged in a pattern or practice of resistance to the

full enjoyment of any of the rights granted by this

title, or that any group of persons has been denied

any of the rights granted by this title and such denial

raises an issue of general public importance, he may

bring a civil action in any appropriate United States

district court by filing with it a complaint setting forth

the facts and requesting such preventive relief, includ

ing an application for a permanent or temporary

injunction, restraining order, or other order against

the person or persons responsible for such pattern or

practice or denial of rights, as he deems necessary to

insure the full enjoyment of the rights granted by this

title.”

This specific statutory grant of authority to the Attorney

General evidences Congress’ intent that this type action be

brought only by the Attorney General. Had Congress in

tended otherwise it would have said so. Had it intended to

authorize any volunteer to bring this type action § 3613

would have been unnecessary.22

21. Cf. Brown v. Balias, 331 F.Supp. 1033, which held that the

injunctive aspects of a case brought under the Fair Housing Act

became moot when the plaintiff was given the housing sought,

22. Respondent does not contend that the authority granted to

the Attorney General diminishes the right of a person directly

aggrieved to seek private enforcement of the Fair Housing Act to

the extent contemplated by the statutes.

23

& *“ It is the policy of the United States to provide for

fair housing” (42 U.S.C. § 3601). The national policy can be

implemented and enforced fully and effectively by the

extensive procedures and efficient machinery contained in

the Fair Housing Act itself. In Jones v. Mayer this Court

described the Act as (p. 417) :

“ * * * a detailed housing law, applicable to a broad

range of discriminatory practices and enforceable by

a complete arsenal of federal authority.”

The arsenal need not be augmented to include unnecessary,

meaningless and inconclusive lawsuits by volunteers.

II

JURISDICTION

A. The Federal Court Does Not Have Subject Matter Jurisdic

tion Over the Claims Asserted Under the Fair Housing Act.

1. CLAIMS UNDER 5 3610.

§ 3610 of the Fair Housing Act provides:

“ (d) I f within thirty days after a complaint is filed

with the Secretary or within thirty days after expi

ration of any period of reference under subsection (c)

of this section, the Secretary has been unable to obtain

voluntary compliance with this subchapter, the person

aggrieved may, within thirty days thereafter, com

mence a civil action in any appropriate United States

district court, against the respondent named in the

complaint, to enforce the rights granted or protected

by this subchapter, insofar as such rights relate to the

subject of the complaint: Provided, That no such civil

action may he brought in any United States district

court if the person aggrieved has a judicial remedy

under a State or local fair housing law which provides

rights and remedies for alleged discriminatory housing

practices which are substantially equivalent to the

rights and remedies provided in this sub chapter. * * *”

(Emphasis added.)

24

Petitioners Traffieante and Carr elected to pursue the pro

cedure of filing a complaint with the Secretary of H.IT.D. as

authorized by § 3610 (R. Ex. A at 5). The State of Cali

fornia has a comprehensive fair housing law generally

known as the Rumford Act (Health and Safety Code,

§ 35700 et seq.) which provides rights and remedies for

alleged discriminatory housing practices which are sub

stantially equivalent to the rights and remedies provided

by the Fair Housing Act.23 The statement of policy in both

Acts is substantially the same (Federal Act §3601; State

Act § 35700). Both make unlawful the same practices (Fed

eral Act §§ 3604, 3605, 3606; State Act § 35720), and both

allow an aggrieved party to file a complaint with an admin

istrative agency (Federal Act § 3610(a); State Act § 35731).

Both State and Federal agencies are required to conduct

appropriate investigations (Federal Act § 3610; State Act

§ 35732). Both Acts provide for injunctive relief (Federal

Aet §§ 3610(d), 3612; State Act § 35734). An award of

damages is authorized by both Acts under certain circum

stances (Federal Act § 3612; State Act § 35738) and both

have judicial remedies (Federal Act §§ 3610(d), 3612; State

Act §§ 35734, 35738). In many respects the Rumford Act

confers upon an aggrieved person remedies superior to

those of the Fair Housing Act but in any event there is

little, if anything, that could not be accomplished under the

Rumford Act that could be achieved under the Fair Housing-

Act. The Rumford Act contains the judicial remedies con

templated by § 3610(d), such remedies being provided by

25

23. Equivalence is recognized by the H.IT.D. In a letter to

Metropolitan the Department said (K. Ex. D at Ex. 1) :

* * * we have found that the State law provides rights

and remedies substantially equivalent to those provided by

the Federal law.”

California Health and Safety Code §§ 35730 and 35738;

Government Code § 11523; and Labor Code § 1428.24 25 26

The Unruh Civil Rights Act (Civ. Code §§ 51, 52) pro

vides further, although alternative,28 remedies to a person

aggrieved. Like the Fair Housing Act, TJnruh prohibits

discrimination in housing (Civ. Code § 51), provides a dam

age remedy (Civ. Code § 52) and authorizes injunctive

relief (Vargas v. Hampson, 57 C.2d 479; 20 Cal. Rptr. 618;

370 P.2d 322):28

Congressional concern for deference to State or local

remedies is pointedly expressed in the congressional history

of the Fair Housing Act. In commenting on judicial enforce

ment procedures, Senator Miller stated:

“ It seems to me that if a State or local fair housing

law provides substantially equivalent rights and reme

dies, if we are going to let the local agencies of govern

ment carry out their responsibilities, they should be

given the opportunity to do so.

# # # # *

“ That is why I provide in the second part of my

amendment that no civil action may be brought in any

U. S. district court if the person aggrieved has a

judicial remedy under a State or local fair housing law

which provides substantially equivalent rights and

remedies to this act.

“I believe it is a matter of letting the State and

local courts have jurisdiction. We in the Senate know

that our Federal district court calendars are crowded

enough, without adding to that load if there is a good

remedy under State law.”

24. To bar a Federal forum, § 3610(d) requires only that there

be a judical remedy under a State or local fair housing law which

provides rights and remedies which are substantially equivalent to

the rights and remedies provided in the Fair Housing Act. It does

not require that the judicial remedy itself be equivalent to the

judicial remedy under the Federal statute.

25. Health and Safety Code § 35731.

26. The Unruh and Romford Acts were the subjects of this

Court’s decision in Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369.

26

to which Senator Hart responded:

“ Mr. President, the Senator from Iowa in making

the suggestion may very well have improved the Bill.

It certainly recognizes the desire all of us share that

the State remedies, where adequate, be availed of

and that unnecessary burdening litigation not further

clog the court calendars.

“ The Senator from Iowa in developing this approach

has made the Bill much more acceptable. The senior

Senator from Illinois [Mr. Dirksen] whose substitute

we are actually discussing, shares this opinion.”27

In Colon v. Tompkins Square Neighbors, Inc., 289

F.Supp. 104 (S.D. N.Y.), the Court refused to assume

jurisdiction of a cause based on alleged racial discrimina

tion in housing because of the existence of a State statute

providing rights and remedies substantially equivalent to

the Federal Fair Housing Act. The Court noted Congres

sional intent, viz.: (pp. 109-110)

“However, as this Court pointed out in its original

decision, the Congress, in Section 810(d) of the 1968

Civil Rights Act, clearly expressed its intent that any

person who claims to have been injured as a result of

an alleged discriminatory housing practice must, as

a prerequisite to the commencement of a suit in any

United States district court, pursue his remedy in the

state forum, assuming such a remedy is available and

is substantially equivalent to the rights and remedies

provided by Congress in the 1968 legislation.”

The Federal and State Acts clearly provide substantially

equivalent rights and remedies and, accordingly, the juris

dictional proviso of § 3610(d) is operative.

27

27. 114 Cong. Rec. 4987.

28

2. CLAIMS UNDER § 3612.

Petitioners Trafficante and Carr have also proceeded

under § 3612 of the Fair Housing Act. The latter Section

does not contain the specific prohibition of Federal juris

diction appearing in § 3610(d) but the legislative history

of the Act makes it reasonably clear that Congress intended

the jurisdictional proviso of § 3610(d) to be applicable to

any suit brought under the Act. Nothing in the discussions

or comments relating to jurisdiction indicate an intent to

provide a broader base of federal jurisdiction under § 3612

than under § 3610. There is no apparent reason for allowing

an action to be brought in a Federal Court under § 3612 if

the same action under § 3610 is prohibited.28

In any event, the remedies provided in §§ 3610 and 3612

are alternative, not concurrent. On April 10, 1968 Repre

sentative Ford quoted from a study memorandum, viz.:

“ Section 812 states what is apparently an alternative

to the conciliation-then-litigation approach above

28. In commenting upon §§ 3610 and 3612, the author of 82

Harvard Law Review 834 observed (pp. 855-856) :

“ It has been tentatively assumed throughout this Note that

direct access is available under section 812 of title VIII. This

assumption may not be easily accepted by courts. Section 812

may be thought to refer only to those actions properly before

a federal court after the procedures outlined in section 810

have been followed. The argument is persuasive for the same

reasons advanced to deny direct access under title VII. The

agency procedures under title V III are quite detailed. To

permit bypassing threatens to render useless the elaborate steps

taken to promote voluntary compliance and state and local

participation in eliminating discrimination. In addition, the

anomalies which apparently result from permitting direct

access under title V III are even less capable of rationalization

than those which would result in the context of title VII. For

example, section 810(d) explicitly requires federal courts to

defer to appropriate state courts. If section 812, which con

tains no such requirement, is interpreted as an independent

and direct route to the court, the concern for deferral is

abandoned for no apparent reason.”

stated: an aggrieved person within 180 days after the

alleged discriminatory practice occurred, may, without

complaining to HUD, file an action in the appropriate

U. S. district court. * * * If the aggrieved party has

first sought the assistance of the Secretary and then

files an action within thirty days of his filing the com

plaint with the Secretary, then the civil action arises

under section 810(d), a section to which the expedition

requirement of section 814 does not apply.” (Emphasis

added)29

Having availed themselves of the procedures set forth in

§ 3610, Trafficante and Carr should be held subject to the

mandates of that Section.30 It was noted in Colon v. Tomp

kins Square Neight ors, I n c supra that: (p. 107)

“ * * * the Court never intended to provide alternative

forums, the choice of which depended solely on the

whim of the plaintiff with total disregard for the

adequacy of state mechanisms.”

The plaintiffs in intervention, who have proceeded

directly under § 3612 without prior resort to the adminis

trative procedures of § 3610, occupy no better jurisdictional

position than petitioners Trafficante and Carr. Since Cali

fornia has fair housing laws which provide rights and

remedies for discriminatory housing practices which are

substantially equivalent to the rights and remedies of the

Fair Housing Act, the plaintiffs in intervention should be

relegated to their State law remedies by reason of § 3610(d)

29

29. 114 Cong. Ree. 9612.

30. Johnson v. Decker, 333 F.Supp. 88 (D.C. Ca.) is distinguish

able. There an action was filed under § 3612 by several plaintiffs

after one had filed an administrative complaint under § 3610.

Unlike this case, no attempt was made to assert claims under § 3610

and § 3612 at the same time in the same judicial proceeding.

of the Fair Housing Act.31 There appears to be no reason or

justification for permitting this action to be filed in a

Federal Court in California. If such action is authorized

without regard to the adequacy of State remedies the juris

dictional limitation of § 3610(d) will have been nullified.

B. Under the Circumstances of This Case the Federal Court

Should Abstain from Exercising Jurisdiction of the Claims

Under § 1982.

The Federal Court should not accept jurisdiction of the

causes of action of the Complaint and Complaint in Inter

vention which are predicated upon an alleged violation of

42 U.S.C. § 1982. In Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385

(1969), this Court admonished that the (p. 388):

“ * * * 1866 Civil Rights Act considered in Jones [v.

Mayer, 392 U.S. 409] should be read together with the

later statute on the same subject (citations) so as not

to pre-empt the local legislation which the far more

detailed Act of 1968 so explicitly preserves.” (Emphasis

added.)

The subject matter of the petitioners’ § 3610, § 3612, and

§ 1982 claims are exactly the same and they should not be

allowed to strip the Fair Housing Act’s mandatory defer

ence to State and local fair housing laws by simply resorting

to § 1982. The combined rationale of Jones, Hunter, and

Colon requires that, at the very least, Federal Courts should

abstain from exercising jurisdiction under the circum

stances of this case.

30

31. In Brown v. Lo Duca, 307 F.Supp. 102, and Johnson v.

Decker, 333 F.Supp. 88, direct access to the District Court under

§ 3612 was allowed. Those decisions, however, appear irreconcilable

with the combined effect of Jones v. Mayer, Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385, Colon v. Tompkins Square Neighbors, Inc., the con

gressional history of the Fair Housing Act, and the specific mandate

and spirit of § 3610(d).

31

III

THE CASE IS MOOT A S T O METROPOLITAN

As heretofore noted, on December 21, 1970, Metropolitan

sold the buildings, structures and improvements consti

tuting Parkmerced and leased the underlying land to Park-

merced Corporation for an initial term of thirty years.

On that date, Metropolitan was divested of all right to

manage, control or otherwise operate Parkmerced, including

the rental of apartment units, and it no longer has any

employees engaged in Parkmerced operations (R. Ex. K

at 1, 2).

In United States of America v. W. T. Grant Company,

345 U.S. 629 (1953) this Court stated (p. 633):

“Along with its power to hear the case, the court’s

power to grant injunctive relief survives discontinu

ance of the illegal conduct. (Citations.) The purpose of

an injunction is to prevent future violations, (citation)

and, of course, it can be utilized even without a showing

of past wrongs. But the moving party must satisfy

the court that relief is needed. The necessary deter

mination is that there exists some cognizable danger of

recurrent violation, something more than the mere

possibility which serves to keep the case alive.”

(Emphasis added.)

Similarly, in United States v. Concentrated Phosphate

Export Association, Inc., 393 U.S. 199 (1968), the Court

observed (p. 203):

“A case might become moot if subsequent events made

it absolutely clear that the allegedly wrongful behavior

could not reasonably be expected to recur. (393 U.S.

199, 203.)

See, also:

United States of America v. Alaska Steamship Com

pany, 253 U.S. 113 (1920);

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S.

448 (1957);

Alejctndrino v. Quezon, 271 U.S. 528 (1926);

Golden v. Zwickler, 394 U.S. 103 (1969);

Alameda Conservation Association, et al. v. State of

California, et al., 437 F.2d 1087 (Ca. 9) cert. den.

402 U.S. 928;

McKee d Co. v. First National Bank of San Diego,

397 F.2d 248 (Ca9)

In Powell v. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486 (1969), this Court

capsuled the mootness rale, viz.: (p. 496)

“ Simply stated, a case is moot when the issues pre

sented are no longer dive’ or the parties lack a legally

cognizable interest in the outcome.”

This action is now moot as to Metropolitan. There exists

no “ cognizable danger of recurrent violation” (United

States of America v. W. T. Grant Company, snpra). The

fact that the petitioners have claimed damages does not

save the ease from the mootness doctrine as it did in Powell

and Textile Workers Union. Petitioners here are not

entitled to damages in any event.

The prayer for injunctive relief against Metropolitan is

now academic. While petitioners challenged Metropolitan’s

claim to mootness in the courts below they did concede that

“ a court would have difficulty in enforcing an affirmative

action order against a seller who no longer controlled the

rental offices or the business operations of the project * *

Having no control whatever over the operation of Park-

mereed, Metropolitan would be powerless at this time to

comply with any injunctive order, either prohibitory or

mandatory, that a Court might otherwise theoretically

make.

32

33

CO N CLU SIO N

For the foregoing reasons the Judgment of the Court of

Appeals should be affirmed.

Dated: July 14, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

R ichard J. K il m a r t in

K n ig h t , B oland & R iordan

Attorneys for

Respondent

Metropolitan Life

Insurance Company

Appendix A.

In the United States District Court for the

Northern District of California

Case No. C-70 1754(RHS)

Paul J. Trafficante, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

and

Committee of Parkmerced Residents Com

mitted to Open Occupancy, et al.,

Plaintiffs in Intervention,

v.

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company,

et al.,

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

DISMISSING COMPLAINT AND COMPLAINT

IN INTERVENTION

Plaintiffs, residents of the Parkmerced complex of apart

ments and town houses in San Francisco, brought this

action under 42 U.S.C. § 1982 and the fair housing provi

sions of Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.,

Chapter 45, alleging that defendant Metropolitan, the then

owner and operator of Parkmerced, was engaging in dis

criminatory housing practices in violation of the Act,

making Parkmerced what plaintiffs have repeatedly re

ferred to in this litigation as a “white ghetto” and depriving

plaintiffs of their alleged right to live in a racially integrated

community. A complaint in intervention was filed by com

munity organizations and civic-minded individuals reiterat

ing substantially the same claims. During the course of the

litigation Metropolitan sold substantially all its interests in

Parkmerced to Parkmerced Corporation, which now oper

ates it and was joined as a defendant.

2 Appendix

The threshold question, of course, is whether the plain

tiffs have standing to maintain this action. They do not

allege, nor can they, that they themselves have been denied

any of the rights guaranteed by Title VIII or by 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982 to purchase or rent real property. Rather, they assert

that the denial of such rights to others not parties to this

action violates the policies of the Act and has resulted in

denying them the benefits of living in the type of integrated

community which Congress hoped to achieve by enacting

Title VIII.

The Court, after full review of the voluminous memo

randa submitted, has concluded that plaintiffs and plain

tiffs in intervention have no such generalized standing as

they assert to enforce the policies of the Act. More specifi

cally, they are not “persons aggrieved” under § 810 of the

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3610(a), and therefore may not maintain

this suit under § 812, 42 U.S.C. § 3612, or under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982. The enforcement of the public interest in fair housing

enunciated in Title VIII of the Act and the creation of

integrated communities to the extent envisioned by Con

gress are entrusted to the Attorney General by § 814, 42

U.S.C. § 3613, and not to private litigants such as those

before the Court.

In reaching this conclusion the Court is not unmindful

of the “private attorneys general” cases heavily relied upon

by plaintiffs, including, quite recently, Data Processing

Service v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970). Each of such cases,

however, was brought under the Administrative Procedure

Act or otherwise involved action by a government agency

and not the activities of private individuals such as are in

volved here. These cases are extensively reviewed and dis

tinguished in Sierra Club v. Hided, 433 F. 2d 24 (9th Cir.

1970).

Appendix 3