Havens Reality Corporation v. Coleman Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Havens Reality Corporation v. Coleman Brief Amici Curiae, 1981. f3796095-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c2b400e-bb93-4f5f-8f57-0b963ff89882/havens-reality-corporation-v-coleman-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

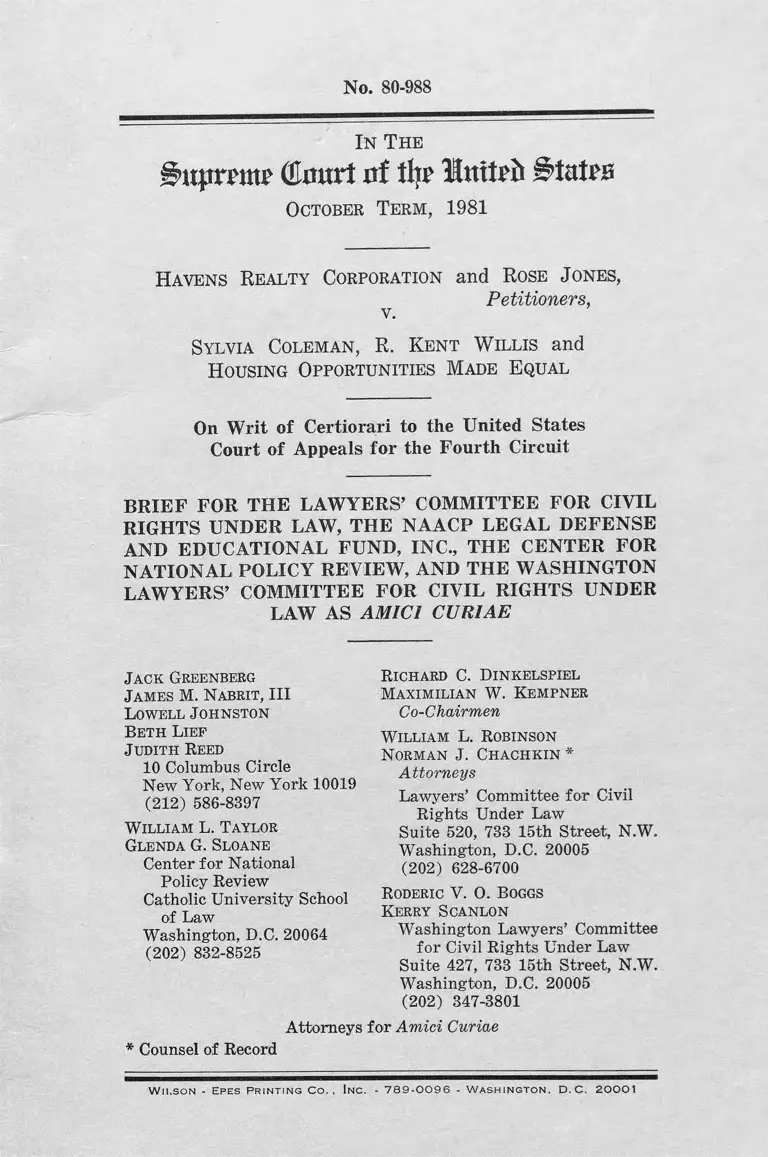

No. 80-988

I n T he

(Emtrt uf th? lUttiteh States

October Term, 1981

Havens Realty Corporation and Rose J ones,

Petitioners,v.

Sylvia Coleman, R. Kent W illis and

Housing Opportunities Made E qual

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE CENTER FOR

NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW, AND THE WASHINGTON

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW AS AMICI CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Lowell J ohnston

Beth Lief

J udith Reed

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

William L. Taylor

Glenda G. Sloane

Center for National

Policy Review

Catholic University School

of Law

Washington, D.C. 20064

(202) 832-8525

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Maximilian W. Kempner

Co-Chairmen

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin *

Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

Suite 520, 733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Roderic V. O. Boggs

Kerry Scanlon

Washington Lawyers’ Committee

for Civil Rights Under Law

Suite 427, 733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 347-3801

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

I N D E X

Table of Authorities....................... ii

Interest of Amici Curiae ........................................... - 1

Statem ent............................ 4

Summary of Argument.—.----------- 7

ARGUMENT

I. In Light of Events Which Have Occurred Sub

sequent To The Entry Of Judgment Below,

This Court Should Not Reach The Merits Of

This Case.................... 8

II. Alternatively, This Court Should Remand For

Further Development And Narrowing Of The

Issues................. 11

Conclusion ........ ............. —- .......... .............. .................... 15

Appendix—The Standing of “Testers” To Challenge

Racial Steering Under the Fair Housing

Act of 1968 ............. .......... .......................... la

Page

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Coles v. Havens Realty Corp., 633 F.2d 384 (4th

Cir. 1980) ____ ____________ _______ -----...... - 13, 14

Coles v. Havens Realty Corp., Civ. No. 79-0024

(E.D. Va., Feb. 17, 1981), reprinted in EQUAL

OPP. HOUS. H 18,031 (P-H) __________ 6,7,8,9,12

County of Los Angeles v. Davis, 440 U.S. 625

(1979) --------- ---------------------------- ---------..... 4,11

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974)............ 9

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202 (1958) ------- ------- 4a

Fair Housing Council v. Eastern Bergen County

MLS, 422 F. Supp. 1071 (D.N.J. 1976) ........... la

Gladstone, Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441

U.S. 91 (1979)....................... -- .4 , 10, 11, 12,13,14, 15

Grant v. Smith, 574 F.2d 252 (5th Cir. 1978) (per

curiam) _________ -............................ ................ 4a

Indiana Employment Security Div. v. Burney, 409

U.S. 540 (1973) ................. - --------- ---------- --- 9,11

Johnson v. Board of Educ. of Chicago, —— U.S.

-, 66 L. Ed. 2d 162 (1980) .......... ................. 4, 11

Meyers v. Pennypack Woods Home Ownership

Ass’n, 559 F.2d 894 (3d Cir. 1977).................... la, 4a

Minnick v. California Dep’t of Corrections, 49

U.S.L.W. 4609 (June 1, 1981) ............... ......... 9, 10, 13

Moore v. Townsend, 525 F.2d 482 (7th Cir. 1975).. la

Northside Realty Associates, Inc. v. United States,

605 F.2d 1348 (5th Cir. 1979)-------------- ------ 4a

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) .................... 4a

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 (1972) ......... 14

Smith v. YMCA of Montgomery, 462 F.2d 634

(5th Cir. 1972)............... ................ ........ -........ - 4a

South Spring Hill Gold Mining Co. v. Amador

Medean Gold Mining Co., 145 U.S. 300 (1892).. 9

Swift & Co. v. Hocking Valley R.R., 243 U.S. 281

(1917) - .... - - ...... - .... ...... ..... - ........... .......... .... 9

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S.

205 (1972) ------- ----- ------ ----------------- -------- 13, 2a

Turner v. A.B, Carter, Inc., 85 F.R.D. 360 (E.D.

Va. 1980) ...................... ------------------ ------------ 6, 10

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 934 (1972)___ __ _____ 4a

United States v. Real Estate One, Inc., 433 F.

Supp. 1140 (E.D. Mich. 1977) ..........-....... ........ la, 4a

United States v. Youritan Constr. Co., 370 F. Supp.

643 (N.D. Cal. 1.973), modified as to relief and

aff’d, 509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1975) ______ __ 3a

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975)_______~~ 12, 13

Wheatley Heights Neighborhood Coalition v. Jenna

Resales Co., 429 F. Supp. 486 (E.D.N.Y. 1977).. 3a, 4a

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028 (E.D. Mich.

1975), aff’d and remanded, 547 F.2d 1168 (6th

Cir. 1977) (per curiam) ......... ................ —...... - la

Statutes and Rules:

42 U.S.C. § 1982 .............................. ........ ....... ....... 6,12

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. ................... ..................... 6

42 U.S.C. § 3601 .............................. -.... ................ - 2a

42 U.S.C. § 3604(a).............. ............. ................ -la, 2a, 3a

42 U.S.C. § 3604(b)....... - ................ ... ........... - ..... 3a

42 U.S.C. § 3604(c).....- ...... -......... ........... ........ .... 4a

42 U.S.C. § 3604(d) _____________ ---- ------- ----- 3a

F.R. Civ. P. 23(b) (2) .................. ..................... ----- 6

F.R. Civ. P. 5 4 (b )..............—- ---- ------------- ----- 6,7,8

Supreme Court Rule 17.1(c) ............................ - .... 12

Other Authorities:

114 Cong. Rec. (1968).......— .... -........ -........... - .... 2a, 3a

EQUAL OPP. HOUS. If 19,905 (P-H) ............ . 9

Page

In The

Bnprme ( ta r t nf % Imtrti

October Term, 1981

No. 80-988

Havens Realty Corporation and Rose J ones,

Petitioners, v. ’

Sylvia Coleman, R. Kent W illis and

Housing Opportunities Made E qual

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE CENTER FOR

NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW, AND THE WASHINGTON

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE *

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys through

out the country in the national effort to assure civil rights

to all Americans. Through its national office in Washing

ton, D.C. and local Lawyers’ Committee such as the Wash

ington, D.C. Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under

* The parties’ letters of consent to the filing' of this brief are

being filed with the Clerk pursuant to Rule 36.1.

2

Law, the organization has over the past eighteen years

enlisted the services of thousands of members of the pri

vate bar in addressing the legal problems of minorities

and the poor in voting, education, employment, housing,

municipal services, the administration of justice, and law

enforcement.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

is a non-profit organization incorporated under the laws

of the State of New York in 1940. It was formed to

assist blacks to secure their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. Its purposes include rendering

legal aid gratuitously to blacks suffering injustice by

reason of race who are unable, on account of poverty, to

employ legal counsel on their own behalf, and its charter

was approved by a New York court, authorizing the or

ganization to serve as a legal aid society. The Fund is

independent of other organizations and is supported by

contributions from the public.

Attorneys employed by or associated with the Legal

Defense Fund have participated in numerous fair hous

ing cases in the federal courts, including this Court, e.g.,

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), and have sub

mitted briefs amicus curiae in other such cases, e.g.,

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205

(1972).

The Center for National Policy Review (CNPR) is a

privately-funded public interest law center located in

the Catholic University School of Law. Founded in

1970, CNPR represents the interests of the civil rights

community within the federal policy-making and admin

istrative process. Because the need for the enforcement

of the right to secure housing free of discrimination is

of primary importance, CNPR has been particularly con

cerned with the administration and implementation of

Title VIII (Fair Housing Act of 1968).

3

The Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law was founded in 1968 to help focus the en

ergies of the private bar on civil rights and poverty is

sues affecting the greater Washington area. The Wash

ington Committee has organized panels of volunteer

attorneys to work on cases affecting individuals and im

portant law reform, issues in the areas of equal housing

and employment opportunities, narcotics addiction, the

parole process, and immigration. More than 650 volun

teer attorneys from over 80 area law firms have worked

on Washington Committee projects, expending (for ex

ample) in 1978 well over 20,000 hours of lawyers’ time.

All of the amici organizations, their local committees,

affiliates and volunteer attorneys thus have been actively

engaged in providing legal representation to those seek

ing relief under federal civil rights legislation. Their

litigation includes cases raising housing discrimination

issues similar to those presented here.

This case raises a welter of questions concerning the

standing of various parties plaintiff and the timeliness

of the filing of the action. Determination of those issues

turns on the peculiar facts and circumstances involved,

but the Court’s decision will also have a significant effect

upon other lawsuits under the Fair Housing Act of 1968

and similar statutes. This is especially so because peti

tioners raise standing claims under Article III of the

Constitution.

Amici believe that the Court should proceed cautiously,

however, in addressing the issues in this case. As we

show below, events which have transpired since the entry

of the judgment below, about which the Court has not yet

been informed, have worked a significant material change

in the factual posture of this case and may render it

moot.

For this reason, amici suggest that the most appro

priate disposition of this matter would be to dismiss

4

the writ as improvidently granted. Alternatively, the

Court could remand the case to the district court for

consideration of possible mootness, and for reconsideration

of the trial court’s earlier ruling in light of this Court’s

intervening decision in Gladstone, Realtors v. Village of

Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91 (1979). See, e.g., Johnson v. Board

of Educ. of Chicago, ----- U.S. ----- , 66 L. Ed. 2d 162

(1980) (remanding for consideration of matters raised

in Suggestion of Mootness and responses thereto). That

disposition would require vacating the opinion and judg

ment below. See County of Los Angeles v. Davis, 440

U.S. 625, 634 n.6 and accompanying text (1979).

Even if the Court does not wish to dispose of the case

in this fashion, amici submit that it is neither necessary

nor appropriate to reach and decide all of the various

issues which have been raised and briefed by the parties

as a result of the alternative holdings anounced by the

Fourth Circuit. The Court should adhere to its practice

of adjudicating constitutional questions only when neces

sary to the disposition of a case. Because the substan

tive issues presented by petitioners in this matter are in

extricably interrelated on the present record, they cannot

be appropriately narrowed for decision by this Court in

the absence of further proceedings below. The remand

for this purpose which amici suggest would isolate and

sharpen the questions which must be decided here, leav

ing for another day those which should be reached only in

the context of a different case in which their determina

tion will be critical.

STATEMENT

The relevant facts of record in this matter are not

disputed. In the spring of 1978, Coleman and Willis

visited the offices of petitioner Havens to obtain informa

tion about apartment availability for their employer,

respondent H.O.M.E. (Housing' Opportunities Made

5

Equal). Subsequently, Coleman, Willis, and other

H.O.M.E. employees conducted “tests” to determine

whether prospective lessees of different races were given

the same information about availability in two apart

ment complexes managed by petitioner Havens Realty.

These “tests” involved successive visits and inquiries

about vacancies of Havens’ employees by Coleman, who

is black, and Willis, who is white (or by another white

H.O.M.E. employee, John Barr, who is not a respondent

in this case). The “tests” indicated that Havens em

ployees were “steering,” either by directing blacks who

inquired about apartment availability only to one of the

two complexes, or by representing to them that there were

no vacancies—while whites who inquired were told of

apartments available in either development.

Coleman and Willis were “testers” because at the times

they visited Havens’ offices, they had no present intention

to enter into a lease of any apartment which might be

available in either complex; rather, their motivation was

to determine whether Havens treated black and white

prospective lessees differently on account of race. The

complaint alleges that both Coleman and Willis are

“residents of the City of Richmond or Henrico

County . . . .”

On July 13, 1978, a black man named Paul Allen Coles,

who did wish to reside in one of the apartment develop

ments handled by Havens, inquired about availability

from Havens’ employees. Coles was informed that the

only apartment available was in the other complex, to

which the earlier “tests” indicated that blacks were being

steered. Later that same day, the complaint alleges,

white “tester” John Barr visited Havens’ offices and was

told of an available apartment in the complex in which

Coles had wished to reside.

This lawsuit, charging Havens Realty with racial

steering in violation of the Fair Housing Act (Title VIII

6

of the Civil Rights Act) of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et

seq., and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1982,

was filed 180 days later. Plaintiffs in the suit were Coles,

Coleman, Willis, and H.O.M.E. Broad injunctive relief,

damages, and attorneys’ fees were sought. In response to

Havens’ motion, the district court dismissed all of the

plaintiffs except Coles, on the grounds that Coleman,

Willis and H.O.M.E. lacked standing, and that the suit was

filed too late with respect to Coleman and Willis in any

event since their last “test” of Havens’ practices occurred

more than 180 days prior to the filing of the suit.

Respondents were then granted a final judgment as

to the standing and timeliness issues, pursuant to F.R.

Civ. P. 54(b), and they appealed to the Fourth Cir

cuit, which on September 11, 1980 rendered its opinion

and judgment reversing the district court’s rulings. This

Court granted certiorari to review that judgment on April

20, 1981.

The additional relevant facts about which the Court

appears not yet to have been advised are as follows:

After respondents appealed with respect to plaintiffs

Coleman, Willis and H.O.M.E., proceedings in the dis

trict court continued on behalf of plaintiff Coles. On

February 13, 1980, pursuant to F.R. Civ. P. 23(b) (2),

Coles was recognized as the representative of a certified

plaintiff class of “all black persons who may have been

injured monetarily by the alleged racial steering prac

tices of [Havens]on or since January 9, 1977,” Coles v.

Havens Realty Corp., Civ. No. 79-0024 (E.D. Va,, Feb.

17, 1981), reprinted in EQUAL OPP. HOUS. 18,031

(P-H). See Turner v. A.B. Carter, Inc., 85 F.R.D. 360

(E.D. Va. 1980). The case was tried June 22 and 23,

1980, and the parties thereafter entered into a Consent

Decree approved by the district court on February 17,

1981, which recites that

The Court finds from the evidence presented in this

case that the policies and acts of the defendants

7

Havens Realty Corporation and Rose Jones violated

the provisions of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and

the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Coles v. Havens Realty Corf., supra, at 18,136. The con

sent decree permanently enjoined the petitioners from vio

lating either statute and granted extensive additional in

junctive relief for a period of three years, including

recordkeeping of visitors to Havens’ offices and appli

cants for apartments, posting of racial occupancy and

vacancy information in its offices on a current basis for

both apartment complexes, display of fair housing logos

in the office, and use of the logos on all forms and in all

advertisements. It awarded $2250 damages to Coles and

established a $13,500 claim fund for class members, per

mitting H.O.M.E. to counsel prospective claimants against

the fund. Finally, it required the payment of $17,500 in

attorneys’ fees by Havens. Id. at 18,136-38. The only

matters not addressed explicitly in the consent decree are

the claims of Coleman, Willis and H.O.M.E. for damages.

On July 1, 1981, the district court approved payment of

various claims filed by class members against the $13,500

fund established by the consent decree. The court further

directed that the case be “closed,” subject to the terms of

the permanent injunction which had issued as part of

the decree.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The appeal below involved an order of dismissal as to

some, but not all, of the plaintiffs in this case, pursuant

to F.R. Civ. P. 54(b). After the Court of Appeals issued

its decision, the remaining plaintiff (who had been certi

fied as representative of a class) and the petitioners en

tered into a consent decree which appears to grant sub

s tan tia l all of the relief sought in the complaint, and

which includes language that may be interpreted as re

linquishing the claims of the dismissed plaintiffs who had

appealed. The Court should, therefore, dismiss the writ

8

as improvidently granted or remand this case for a de

termination as to possible mootness.

Alternatively, the Court should remand so that the is

sues can be further developed and narrowed with the re

sult of limiting the number or scope of constitutional ques

tions which this Court would be required to decide in

this case. Because of the alternative holdings announced

below, the issues cannot be narrowed absent such a

remand.

ARGUMENT

I

In Light Of Events Which Have Occurred Subsequent

To The Entry Of Judgment Below, This Court Should

Not Reach The Merits Of This Case

As indicated in the brief Statement, supra, this case

reaches the Court in a rather unusual posture. As a re

sult of the F.R. Civ. P. 54(b) judgment permitting an

appeal of the trial judge’s standing and timeliness deter

minations as to respondents, those issues were litigated

before the Fourth Circuit at the same time as the factual

allegations of the complaint were made the subject of

evidentiary proof and hearing.1 Following the hearing,

the remaining plaintiff (represented by the same coun

sel as respondents) and the petitioners stipulated to a

finding of racial steering in violation of the Fair Hous

ing Act of 1968 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866—and

to the entry of a judgment awarding broad injunctive

relief, damages to Coles and to the class of plaintiffs

whom he represented, and attorneys’ fees to plaintiffs’

counsel.

1 Although it is not apparent from the record before this Court

nor from the consent decree entered February 17, 1981, Coleman

and Willis testified as H.O.M.E. employees on behalf of Coles at the

June, 1980 trial. The consent decree makes specific provision for

H.O.M.E. to counsel class members. See Coles v. Havens Realty

Cory., supra at 18,138.

9

In these circumstances, it simply is not clear what is

left of this lawsuit, as it was originally framed in the

complaint filed by respondents and Coles. On its face,

the consent decree appears to provide substantially the

relief sought in the case. To be sure, respondents had

been dismissed as formal plaintiffs in the case at the time

the consent decree was negotiated and approved, and

their respective claims for damages from petitioner

Havens were not addressed explicitly in that decree.

However, the decree on its face does appear to resolve

the claims of

. . . all plaintiffs, including those that may hereafter

be joined by the Court pursuant to the class certifica

tion of this action, for all damages, costs, expenses,

and fees incurred in all negotiations and/or other

activities arising out of the Complaint filed herein.

Coles v. Havens Realty Corp., supra, at 18,138 (emphasis

supplied). The effect of this language has not yet been

determined, but it is certainly conceivable that, either

as a result of this provision of the decree or by virtue of

the substantial relief awarded in the decree, the con

troversy between the parties is now moot.2

2 Neither petitioners (in their petition for certiorari or their

brief on the merits) nor respondents (in their Brief in Opposition

to Certiorari or in a subsequent filing) have yet advised the Court

of the entry of the consent decree. Respondents may have felt

bound to defend the judgment and opinion of the court below—or

may wish to obtain a ruling from this Court because H.O.M.E.’s

operations in the Richmond area continue. See, e.g., EQUAL OPP.

HOUS. ft 19,505 (P~H). Petitioners similarly may desire to have

this Court’s views on the reasoning of the court below. Of course,

the parties may not stipulate a case to be within the jurisdiction

of this Court. See Minnick v. California Dep’t of Corrections, 49

U.S.L.W. 4609 (June 1, 1981) ; DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312

(1974) ; Indiana Employment Security Div. v. Burney, 409 U.S. 540

(1973) ; Sw ift & Co. v. Hocking Valley R.R., 243 U.S. 281, 289

(1917) ; South Spring Hill Gold Mining Co. v. Amador Medean

Gold Mining Co., 145 U.S. 300 (1892).

10

Petitioners have advanced serious constitutional

claims, but that fact only underscores the urgency of de

termining whether or not this litigation has continuing

vitality. For this Court has many times emphasized that

it follows a “ ‘policy of strict necessity in disposing of

constitutional issues,’ Rescue Army v. Municipal Court,

331 U.S. 549, 568 . . . Minnick v. California Dep’t of

Corrections, 49 U.S.L.W. 4609, 4613 (June 1, 1981).

The mootness determination can best be made by the

district court, which is also in the best position to con

strue the terms of the consent decree. Further pro

ceedings in the trial court, if the case is determined not

to be moot, would have several additional advantages:

(1) the trial court could reconsider its rulings as to the

standing of the various respondents in light of this

Court’s subsequent decision in Gladstone, Realtors v. Vil

lage of Bellwood, supra [hereinafter cited as “Bell-

wood”].3 (2) The ambiguities of the record, upon which

petitioners focus significant attention (see Brief for Peti

tioners, at 26-27, 30-31), could be clarified by appropri

ate amendment of the complaint to delineate the exact

location of Coleman’s and Willis’ residences, and the pre

cise impact upon the surrounding neighborhoods of

Havens’ adjudicated racial steering practices, see Bell-

wood, supra, 441 U.S. at 112 n.25. (3) Similarly, uncer

tainties concerning the residential location of H.O.M.E.’s

membership {see Brief for Petitioners, at 13-14) could

be eliminated through amendment of the pleadings. (4)

The question of the timeliness of the filing of this action

could be redetermined by the district court with respect

to the claims of Coleman and Willis as residents of the

affected community (see pp. 12-14 infra), if the trial *

* The district judge apparently recognized that his ruling was

open to question after Bellwood, for he sought a remand of this

case from the Fourth Circuit in light of that decision. See Turner

v. A.B. Carter, Inc., supra, 85 F.R.D. at 363 n.3.

11

court reaches a different result as to their standing in

this capacity under Bellwood, supra.

For these reasons, and in light of the altered posture

of this case, amici suggest that the writ of certiorari be

dismissed as improvidently granted, which will have the

effect of returning the matter to the district court. Alter

natively, the Court may wish to vacate the judgment be

low and remand the case to the district court for con

sideration of possible mootness, see, e.g., Johnson v.

Board of Educ. of Chicago, supra; Indiana Employment

Security Div. v. Burney, supra-, this disposition would

remove any precedential weight from the ruling below,

see County of Los Angeles v. Davis, supra, 440 U.S. at

634 n.6.

II

Alternatively, This Court Should Remand For Further

Development And Narrowing Of The Issues

As we have previously remarked, the Court is pre

sented with a multiplicity of issues relative to respond

ents’ standing and the timeliness of this suit’s commence

ment because of the alternative holdings by the Fourth

Circuit. At the same time, as we show below, many of

the issues are interrelated and their disposition in this

case depends upon specific additional factual allegations

or proof. Amici urge the Court to remand this case,

rather than attempting to decide all of these questions,

so as to allow reconsideration of the district court’s rul

ings in light of Bellwood, supra, amendment of the plead

ings, and narrowing of the issues. This disposition is

likely to result in avoiding the necessity for this Court

to decide at least some of the multiple questions pre

sented in the current posture of this action.

All of the issues raised before the Court are inter

related with each other, and decision of some will make

unnecessary disposition of the others. For example, if

12

Willis and Coleman have standing as residents of areas

affected by the discriminatory steering practices of Ha

vens,4 there would be no need to address the timeliness

issues, since in their capacity as residents of the “target

area,” 5 6 see Bellwood, supra, 441 U.S. at 112 n.25, they

would have suffered injury when Coles was steered on

July 13, 1978 B—and their complaint, filed 180 days later,

would clearly have been timely. Similarly, if standing

were sustained under § 1982, as the district court recog

nized there would be no problem regarding timeliness.

On the other hand, if Willis and Coleman have standing

as “testers,” 7 then the timeliness questions must be de-

4 The district court held racial steering to violate both the 1968

Fair Housing Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1982. Coles v. Havens Realty Corp., supra, at 18,136. This holding

was not disturbed by the Court of Appeals and petitioner has not

contested that determination here. Hence, this Court need not

pass upon the matter. See Bellwood, supra, 441 U.S. at 115 n.32.

(The Court in that case did recognize the severe consequences which

could follow steering on a major scale, id. at 109-11.)

6 The complaint alleges that Coleman and Willis are “residents

of the City of Richmond or Henrico County,” which is certainly

broad enough to encompass residence within the “target area.”

As this Court suggested in Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 501

(1975), if there was a need for “further particularized allegations

of fact deemed supportive of plaintiff [s’] standing,” the district

court should have “require[d] the plaintiff [s] to supply [them], by

amendment to the complaint or by affidavits,” rather than dis

missing.

6 Steering “testers” does not affect their ability to reside in

integrated communities nor deprive them of interracial associations

since by definition “testers” are not seeking to relocate. But as

residents of a “target area,” “testers” would suffer injury when

ever a bona fide minority applicant for purchase or lease of property

is steered.

7 Amici believe that the issue of “tester standing” involves a

novel question as to which this Court’s guidance would be of

assistance to the lower courts, see Supreme Court Rule 17.1(c),

and that there is strong support in the statute, the legislative

13

eided—but not whether the allegations of the complaint

were sufficient to support their alternative claims of

standing as residents of the area affected by Havens’

steering who were denied the benefits of interracial

associations by Havens’ conduct. The questions of

H.O.M.E.’s standing—either in a capacity as representa

tive of its members or suing in its own organizational

status—and the timeliness of its filing, are likewise inter

twined.

This phenomenon is not unusual, and ordinarily it

would not counsel a remand. Here, however, such a dis

position is appropriate for several reasons. First, this

Court has traditionally sought to avoid unnecessary de

cision of constitutional issues. See Minnick v. California

Dep’t of Corrections, supra, and cases cited therein. De

velopments on remand of this action may obviate the

need for a decision of the constitutional questions raised.

Second, as we have noted, petitioners’ arguments concern

ing the standing of H.O.M.E. as representative of its

history and the case law for recognizing- “tester” standing to

challenge racial steering practices. The question was briefed by

the Lawyers’ Committee in its amicus brief in Bellwood, supra, but

not reached by the Court, see id., 441 U.S. at 111. For the Court’s

convenience, we repeat those arguments in an appendix hereto.

Our submission is, in short, that the racial steering to which

respondents Coleman and Willis were subjected deprived them of

specific rights guaranteed by the Fair Housing Act—and that

invasion of those rights therefore constitutes the requisite personal

injury supporting their standing to sue. Warth v. Seldin, supra,

422 U.S. at 514 (“. . . Congress may create a statutory right or

entitlement the alleged deprivation of which can confer standing

to sue even where the plaintiff would have suffered no judicially

cognizable injury in the absence of statute”) ; Trafficante v. Metro

politan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205 (1972). This was not the

reasoning of the Court of Appeals, which viewed respondents as

“bona fide surrogates” for the victims of discrimination and relied

upon “strong public policy” considerations, Coles v. Havens Realty

Corp., 633 F.2d 384, 387 (4th Cir. 1980).

14

members and of Coleman and Willis as residents of the

“target area” primarily involve the degree of specificity

of the allegations of the complaint (see Brief for Peti

tioners at 11-17), a matter to which the court below was

sensitive. The Fourth Circuit panel emphasized in its

ruling that it was merely permitting respondents to pro

ceed to trial, and that adequate proof to support the

standing claims would have to be adduced; and it sug

gested that the district court require amendment of the

complaint to provide greater specificity. Coles v. Havens

Realty Corp., supra, 633 F.2d at 391; see note 5 supra;

see also Belhvood, supra, 441 U.S. at 112 n.25; Sierra

Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 735 n.8 (1972). Third,

the district court did not reject these alternative stand

ing claims on the grounds now advanced by petitioners.

Instead, the trial judge—acting in advance of this

Court’s ruling in Bellwood—held that respondents (who

claimed that the racial stering practiced by Havens de

nied them the valuable benefits of interracial associa

tions) “assert no more than the general public interest.”

Remanding the matter would therefore give the trial

court an occasion to reconsider that ruling in light of

jBellwood,8 as well as to afford the opportunity for amend

ment of the complaint which the Court of Appeals con

templated. These developments could very well result

in removing the need for further constitutional adjudi

cation by this Court.

8 See note 3 supra.

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici suggest respectfully

that the writ of certiorari previously granted herein be

dismissed as improvidently granted; that the judgment

below be vacated and the case remanded to the district

court to consider possible mootness, reconsider its rul

ings in light of Bellwood, and permit amendment of the

complaint; or that the case be remanded for further

development of the issues, to include such reconsidera

tion and allowance of amendment.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Lowell J ohnston

Beth Lief

J udith Reed

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Maximilian W. Kempner

Co-Chairmen

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin *

Attorneys

(212) 586-8397

William L. Taylor

Glenda G. Sloane

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Policy Review

Catholic University School

Center for National

Rights Under Law

Suite 520, 733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

of Law

Washington, D.C. 20064

(202) 832-8525

Roderic V. O. Boggs

Kerry Scanlon

Washington Lawyers’ Committee

for Civil Rights Under Law

Suite 427, 733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 347-3801

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

The Standing of “Testers” to Challenge Racial Steering

Under the Fair Housing Act of 1968

The statute identifies expansively the discriminatory

practices which it is intended to outlaw. 42 U.S.C.

§ 3604(a) makes it unlawful

To refuse to sell or rent after the making of a bona

fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale or

rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a

dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion

or national origin.

(Emphasis supplied.) The italicized terms are very

broad indeed. The “refusal to negotiate” language is in

dependent of the limiting words, “after the making of a

bona fide offer,” a which appear in the first phrase. The

statute confers on individuals the right to participate in

negotiations for the sale or rental of property free from

racial discrimination whether or not they have a bonu

fide intention to follow through with actual lease or pur

chase. The practice of racial steering constitutes a self-

imposed limitation (on the ground of race or color) of a

realtor’s willingness to negotiate.”

a At least one court has suggested that it is these words which

have prompted decisions holding that “testers” have no standing.

Meyers v. Pennypack Woods Home Ownership Ass’n, 559 F.2d

894, 898 n.4 (3d Cir. 1977).

b Racial steering practices uniformly have been held to be within

the coverage of the Act, though generally on the theory that they

are included within §3604 (a) ’s catchall phrase, “otherwise make

unavailable or deny.” E.g., United States v. Real Estate One, Inc.,

433 F. Supp. 1140 (E.D. Mich. 1977); Fair Housing Council v.

Eastern Bergen County MLS, 422 F. Supp. 1071 (D.N.J. 1976) ;

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028, 1047 (E.D. Mich. 1975), aff’d

and remanded, 547 F.2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977) {per curiam). Cf.

Moore v. Townsend, 525 F.2d 482 (7th Cir. 1975).

2a

The three phrases of § 3604(a) are in the disjunctive;

each applies “to any person” but only the first is re

stricted by the language, “after the making of a bona

fide offer.” Thus, construing § 3604(a) broadly to effec

tuate the Congressional purpose “to provide, within con

stitutional limitations, for fair housing throughout the

United States,” 42 U.S.C. § 3601; see Trafficante v. Met

ropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205 (1972), the ban

on racial steering extends to “testers” and other indi

viduals who may not, at any given moment, be planning

to make bona fide offers for the purchase or lease of par

ticular property.

This reading of the statutory language is confirmed by

the legislative history. Title VIII of the 1968 Civil

Rights Act did not appear in the original House of Rep

resentatives version. It was added by an amendment on

the Senate floor introduced by Senator Dirksen. 114

Cong. Rec. 4570 (February 28, 1968). However, § 204(a)

in Senator Dirksen’s amendment omitted the language in

question and would have made it a discriminatory prac

tice

To refuse to sell or rent, to refuse to negotiate for

the sale or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable

or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race,

color, religion, or national origin.

114 Cong. Rec. 4571 (February 28, 1968). The words

“after the making of a bona fide offer or” were added

subsequently, as the result of an amendment suggested

by Senator Allott and accepted by the bill’s Floor Man

ager, Senator Mondale. 114 Cong. Rec. 5515-16 (March

6, 1968).

When his amendment was brought up for discussion

(cloture having been invoked on the bill), Senator All

ott was very specific about its reach and effect. He

stated that it

. . . applies to sale or rental—the first four words

only of line 7.

It will be noted that the latter part of paragraph (a)

is not conditioned upon a bona fide offer, because the

amendment as offered concludes with the word “or”

rather than “and.”

114 Cong. Rec. 5515 (Mar. 6, 1968). On this basis, the

amendment was accepted by Senator Mondale and incor

porated into the bill. Id. at 5516-17.°

In addition, 42 U.S.C. § 3604(b) prohibits discrimina

tion because of race or color

against any person in the terms, conditions of sale or

rental of a dwelling, or in the provision of services or

facilities in connection therewith . . .

(emphasis supplied). Just as requiring more onerous

application procedures for blacks can be viewed as dis

crimination in the terms or conditions of sale or rental,

cf. United States v. Youritan Constr. Co., 370 F. Supp.

643, 648 (N.D. Cal. 1973), modified as to relief and

aff’d, 509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1975) (holding such con

duct to be within “otherwise make unavailable or deny”

language of § 3604(a)), so may racial steering prac

tices be interpreted to be within the prohibitions of this

subsection, which bars these prohibited practices from

being applied to “any person.” Wheatley Heights Neigh

borhood Coalition v. Jenna Resales Co., 429 F. Supp.

486, 488 (E.D.N.Y. 1977).

Finally, § 3604(d) makes it illegal

To represent to any person because of race, color,

religion, or national origin that any dwelling is not

available for inspection, sale, or rental when such

dwelling is in fact so available.

0 There was no discussion of this language in the House, which

passed the Senate version of the bill without change.

4a

Racial steering constitutes an implicit, and sometimes a

verbal, representation about the availability of housing.

Hence it can be considered within the reach of this sub

section. Compare United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d

205, 215 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 934 (1972)

(implicitly discriminatory advertising; § 3604(c));

United States v. Real Estate One, Inc., supra n.b. (racial

steering effect of assignment of black and white em

ployees by realty firm).

Thus, we submit, the Fair Housing Act creates sub

stantive rights of nondiscriminatory access to informa

tion and related housing market services in favor of

any person, not just persons who make “bona fide offers”

to purchase or lease property. These rights are pre

cisely analogous to the “right to occupy certain public

accommodations or conveyances” which petitioners con

cede was the basis for recognition of “tester” standing

in Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) and Evers v.

Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202 (1958). See Brief for Petitioners

at 23-24.*,

Lower federal courts, while differing as to the appli

cable statutory subsection, have followed this general

analysis, with the result of construing the Act to pro

tect “testers,” as well as “bona fide purchasers,” from

racial steering. Grant v. Smith, 574 F.2d 252, 255 (5th

Cir. 1978) {per curiam) ; Wheatley Heights Neighbor

hood Coalition v. Jenna Resales Co., supra. See also

Northside Realty Associates, Inc. v. United States, 605

F.2d 1348, 1355 (5th Cir. 1979) ; Meyers v. PennypacJc

Woods Home Ownership Ass’n, supra n.5, 559 F.2d at

898; Smith v. YMCA of Montgomery, 462 F.2d 634,

645-46 (5th Cir. 1972).

a Thus, the fact that an individual’s motivation for visiting a

realty office was to conduct a “test” is irrelevant to his or her

standing to redress deprivations of rights guaranteed by the Fair

Housing Act. See Evers v. Dwyer, supra,, 358 U.S. a t 204.

Both Coleman and Willis sought to obtain accurate in

formation about apartment availability by visiting the

Havens Realty offices. Both were subjected to the de

meaning experience of having Havens’ employees’ re

sponses to their inquiries vary according to their racial

identities. Each was, therefore, denied rights guaran

teed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and had standing

to sue for redress.