Chisom v. Roemer Brief of Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

December 14, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chisom v. Roemer Brief of Respondents in Opposition, 1990. ec0f2274-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c302b04-6a9e-4788-a865-09c02e6d44af/chisom-v-roemer-brief-of-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

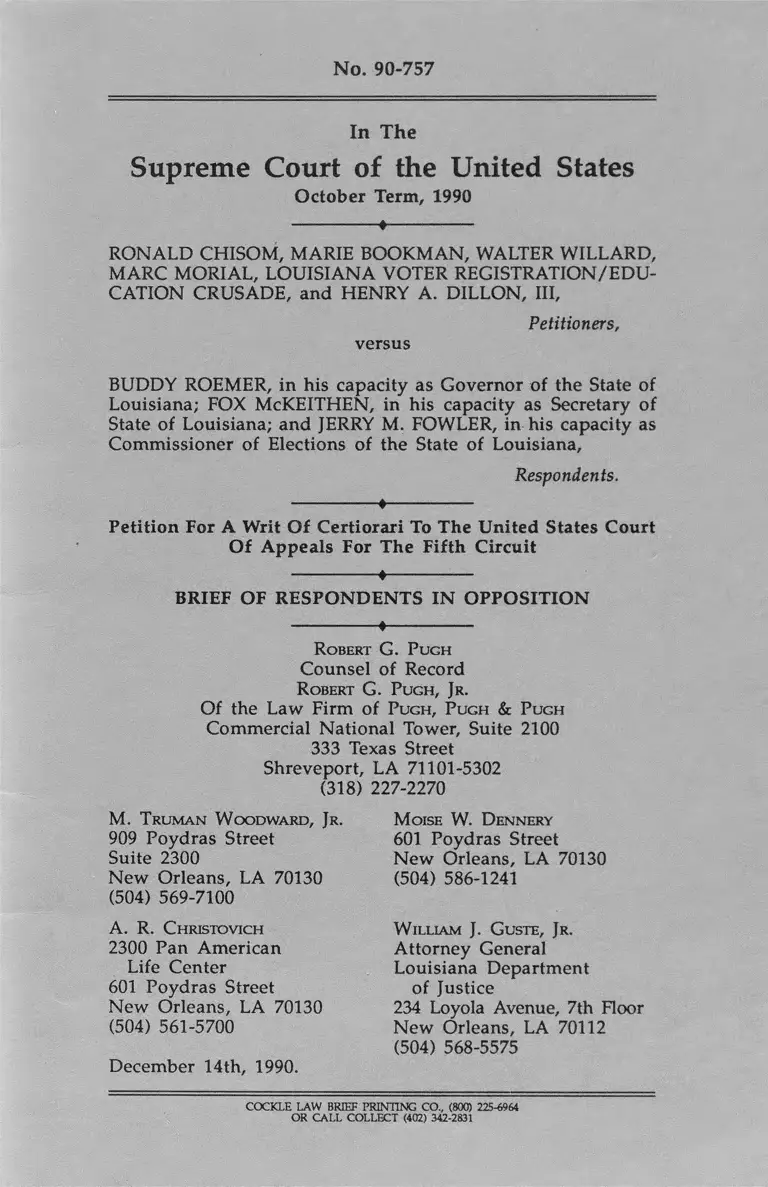

No. 90-757

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

--------------«--------------

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN, WALTER WILLARD,

MARC MORIAL, LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/EDU-

CATION CRUSADE, and HENRY A. DILLON, III,

versus

Petitioners,

BUDDY ROEMER, in his capacity as Governor of the State of

Louisiana; FOX McKEITHEN, in his capacity as Secretary of

State of Louisiana; and JERRY M. FOWLER, in his capacity as

Commissioner of Elections of the State of Louisiana,

Respondents.

--------------•--------------

Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court

Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

--------------♦--------------

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

--------------*--------------

Robert G. Pugh

Counsel of Record

R obert G. Pugh, Jr.

Of the Law Firm of Pugh, Pugh & Pugh

Commercial National Tower, Suite 2100

333 Texas Street

Shreveport, LA 71101-5302

(318) 227-2270

M. Truman W oodward, Jr.

909 Poydras Street

Suite 2300

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 569-7100

A. R. Christovich

2300 Pan American

Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 561-5700

December 14 th, 1990.

Moise W. Dennery

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1241

W illiam J. Guste, Jr.

Attorney General

Louisiana Department

of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 568-5575

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 22S-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

i

QUESTION PRESENTED

Did Congress intend the word "representatives" as

used in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2(b) as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 1973, to include judges who are selected by a

state judicial electoral process?

QUESTION PR E SEN TE D ..................................................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS......................................................... ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................... iv

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE............................................... 1

A. The First Supreme Court District in Louisiana.. 1

B. Prior Proceedings in this Litigation .................... 3

A RG U M EN T.............................................................................. 5

I. THE FIFTH C IR C U IT C O RREC TLY C O N

CLUDED THAT SECTION 2(B) OF THE VOT

ING RIGHTS ACT DOES NOT APPLY TO THE

JU D IC IA RY........................................................................ 5

A. The LULAC D ecision..................................... 5

B. The Genesis of § 2(b) of the Voting Rights

A c t ........................................ 7

C. This Court has always held that Judges are

not "representatives".................................... 8

D. Other Federal Courts have held that Judges

are not "representatives".......................... 10

E. The Term "representatives" is not a...Syn

onym for "elected o ffic ia ls " 14

F. The Fundamental Difference Between "repre

sentatives" and Members of the Judiciary is

Deeply Rooted in this Country's History. . . 17

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Ill

Page

II. IF THE ONE-MAN, ONE-VOTE REQUIREMENT

DOES NOT APPLY TO THE JUDICIARY, THE

CONCEPT OF MINORITY VOTE DILUTION SET

FORTH IN § 2(B) DOES NOT APPLY TO THE

JU D IC IA R Y ........................................................................ 22

C O N C LU SIO N .......................................................................... 29

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

IV

C ases:

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82 S.Ct. 691, 7 L.Ed.2d

663 (1 9 6 2 )........................................................................... 10, 29

Brown v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 706 F,2d 1103 (11th Cir.), affirmed, 464

U.S. 1005, 104 S.Ct. 520, 78 L.Ed.2d 705 (1983).........8

Buchanan v. Gilligan, 349 F. Supp. 569 (N.D. Ohio

1972)............................................................................................. 14

Buchanan v. Rhodes, 249 F. Supp. 860 (N.D. Ohio

1966), appeal dismissed, 385 U.S. 3, 87 S.Ct. 33, 17

L.Ed.2d 3 (1966), vacated 400 F.2d 882 (6th Cir.

1968), cert, denied, 393 U.S. 839, 89 S.Ct. 118, 21

L.Ed.2d 110 (1968)................... 13

Chandler v. Judicial Council, 398 U.S. 74, 90 S.Ct.

1648, 26 L.Ed.2d 100 (1970).............................................. 29

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D.La. 1 9 87 ).........4

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D.La. 1 9 8 8 ) . . . . . 4

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988)..............4

Chisom v. Edwards, 850 F.2d 1051 (5th Cir. 1988)..............4

Chisom v. Edwards, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988)..............4

Chisom v. Roem er,__F. S u p p .___ (E.D. La. 1989)

■ • • .......................................................................... .. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Chisom v. Roem er,___F. Supp. ____(E.D. La. 1 9 9 0 ).......... 5

Chisom v. Roemer, 917 F.2d 187 (5th Cir. 1 9 9 0 )...........5, 7

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490

64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980)..................................7, 23, 24, 25, 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Consumer Products Safety Comm'n v. GTE Sylvania,

447 U.S. 102, 100 S.Ct. 2051, 64 L.Ed.2d 766

(1980 )............................................................................................ 14

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494, 71 S.Ct. 857,

95 L.Ed. 1137 (1951).............................................................. 10

Dickerson v. New Banner Institute, Inc., 460 U.S. 103,

103 S.Ct. 986, 74 L.Ed.2d 845 (1983).............................. 15

Edge v. Sumter County School District, 775 F.2d 1509

(11th Cir. 1985)............................................ 8

Escondido Mut. Water Co. v. La Jolla Indians, 466

U.S. 765, 104 S.Ct. 2105, 80 L.Ed.2d 753 ( 1 9 8 4 ) . . . . 15

Fahey v. Darigan, 405 F. Supp. 1386 (D.C.R.I. 1975) . . . . 14

Gilday v. Board of Elections of Hamilton County, 472

F.2d 214 (6th Cir. 1972).......................................................... 13

Gomez v. City of Watsonville, 863 F.2d 1407 (9th Cir.

1988), cert, d en ied ,___U.S. ____, 109 S.Ct. 1534,

103 L.Ed.2d 839 (1989)............................................................. 8

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 85 S.Ct. 1678,

14 L.Ed.2d 510 (1965).......................................................... 10

Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F. Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C.

1971), affirmed, 409 U.S. 807, 93 S.Ct. 43, 34

L.Ed.2d 68 (1972)............................................................. 10, 11

Jordan v. Winter, 604 F. Supp. 807 (N.D. Miss.),

affirmed, 469 U.S. 1002, 105 S.Ct. 416, 83 L.Ed.2d

343 (1984)....................................................................................... 9

Kail v. Rockefeller, 275 F. Supp. 937 (E.D.N.Y. 1967) . . . . 13

Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1135, 105 S.Ct. 2673, 86

L.Ed.2d 692 (1985)......................................................................8

vi

Latin American Citizens Council #4434 v. Clements,

902 F.2d 293 (5th Cir. 1990).................................................6

Latin American Citizens Council #4434 v. Clements,

914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990) (en banc)................. passim

New York State Association of Trial Lawyers v. Rock

efeller, 267 F. Supp. 148 (S.D.N.Y. 1967)....................... 12

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12

L.Ed.2d 506 (1964).......................................... 10, 12, 23, 29

Roemer v. Chisom, 488 U.S. 955, 109 S.Ct. 390, 102

L.Ed.2d 379 (1988)................................................................... . 4

Romiti v. Kerner, 256 F. Supp. 35 (N.D. 111. 1966)......... 14

Sagan v. Commonwealth o f Pennsylvania, 542 F.

Supp. 880 (W.D. Pa. 1 9 8 2 )................................................... 14

Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964) .11, 29

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1 9 8 6 ).............................7, 23, 24, 27, 28

United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731

F,2d 1546 (11th Cir.), appeal dismissed & cert,

denied, 469 U.S. 976, 105 S.Ct. 375, 83 L.Ed.2d

311 (1984)................................................ 8

Velasquez v. City of Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir.

1984)........................................................................... 8

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972)

..................................................................................... 9, 23, 26, 27

Wells v. Edwards, 409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34

L.Ed.2d 679 (1973).................................. 9, 22, 23, 26, 27

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 91 S.Ct. 1858, 29

L.Ed.2d 363 (1971)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

28

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 37

L.Ed.2d 314 (1973).................................................................... 7

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) . . . . 27

C onstitutional and S tatutory P rovisions:

United States Constitution Fourteenth Amend

ment ...................................................................... .................. 1, 25

United States Constitution Fifteenth A m endm ent. .1, 25

28 U.S.C. § 1 3 3 1 . . . . ......................................................................1

28 U.S.C. § 1343...............................................................................1

28 U.S.C. § 2201 ...............................................................................1

28 U.S.C. § 2202 ...............................................................................1

42 U.S.C. § 1973 [Voting Rights A ct)...............................passim

42 U.S.C. § 1983............................................... 1

1879 Louisiana Constitution Article 8 2 ................................ 2

1898 Louisiana Constitution Article 8 7 ............... 2

1913 Louisiana Constitution Article 8 7 ................................ 2

1921 Louisiana Constitution Article 7 § 9 ............................2

1974 Louisiana Constitution Article 5 § 4 ................... 2, 3

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

viii

R ules:

Fed.R.Civ.P. 1 2 (b )(6 ) ......................................................................3

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

L egislative H istory:

S.Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. reprinted in

1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 177,

196..................................................................................................23

B ooks:

A. Bickel, The Supreme Court and the Idea of Progress

(1978 Yale University Press paperback edition) .20, 21

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust (1980 Harvard Uni

versity Press hardbound edition)....................................20

L. Friedman, A History of American Law (Simon &

Schuster 1973 paperback e d itio n ).................................. 20

E. Hickok, Judicial Selection: The Political Roots

of Advice and Consent in Judicial Selection:

Merit, Ideology and Politics (National Legal Cen

ter for the Public Interest 1990)...................................... 17

G. W hite, The American Judicial Tradition (1978

Oxford University Press edition).............17, 18, 19, 20

N ew spapers:

Baton Rouge State-Times, October 9th, 1 9 8 9 . .............3

New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 8th, 1989............... 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners brought this suit in the United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana on behalf

of all black registered voters in Orleans Parish, approx

imately 135,000 people. The suit challenged the at-large

election of two Justices to the Louisiana Supreme Court

from the parishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines

and Jefferson (the First Supreme Court District) as being

in violation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended,

because of alleged dilution of the voting strength of the

Petitioners. Jurisdiction was based on 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331

and 1343 as well as 42 U.S.C. § 1973. The action sought

declaratory and injunctive relief, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973 and

1983. Petitioners also sought relief under 28 U.S.C.

§§ 2201 and 2202 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. Peti

tioners sought the division of the First Supreme Court

District into two districts, one to be comprised of the

parishes of Jefferson, Plaquemines and St. Bernard and

the other of Orleans Parish where blacks constituted a

majority of the registered voters.

A. The First Supreme Court District in Louisiana.

The Louisiana Supreme Court is the highest court in

the State of Louisiana. The Court is composed of seven

Justices, elected from six Supreme Court districts for a

term of ten years. Chisom v. Roemer,___F. S u p p .____, Slip

Opinion 3 (E.D. La. 1989) (hereinafter cited as "Slip Op.

#"). No parish lines are cut by any of the election districts

for the Supreme Court. Slip Op. 4.

1

2

The First Supreme Court District, consisting of the

city of New Orleans and its surrounding environs,1 has

been the only district that has elected two Justices since

adoption of the 1879 Louisiana Constitution more than

110 years ago. Slip Op. 16; see Louisiana 1879 Constitution

Article 82; Louisiana 1898 Constitution Article 87; Louisi

ana 1913 Constitution Article 87; Louisiana 1921 Consti

tution Article 7, § 9; and Louisiana 1974 Constitution

Article 5, § 4.

The most recent Louisiana Constitution took effect in

1974 after the 1973 Louisiana Constitutional Convention.

Twelve of the 132 delegates to the Convention were black.

Slip Op. 17. During the Convention three amendments

were proposed to divide the Supreme Court into single

member districts. The first failed 27-85, with one black

delegate voting for the proposal, eleven [sic - should be

ten] against, and one absent. Slip Op. 18. The second

failed 47-67, with seven blacks voting for the amendment,

four against, and one absent. Slip Op. 18. The final

amendment proposed splitting the First Supreme Court

District into two districts, with one Justice to be elected

from each. When a white delegate argued in favor of the

proposal, a black delegate from Orleans Parish responded

that the present arrangement should not be changed. Slip

Op. 19. This amendment was defeated 50-63, with five

blacks voting for the amendment and seven against. Slip

Op. 19. The final districting plan, leaving the First

Supreme Court District with two Justices, was adopted

103-9, with eight blacks voting for the plan, one against,

1 The parishes in the First Supreme Court District include

Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson Parishes.

3

and two absent. Slip Op. 19. Four of the blacks voting for

the plan were delegates from Orleans Parish.

The proposed Constitution was approved by the

United States Department of Justice and ratified by the

voters of Louisiana on April 20th, 1974. Slip Op. 19.

Although the Louisiana Legislature has the authority to

change districts and . the number of Justices by a two-

thirds vote, 1974 Louisiana Constitution Article 5, § 4, it

has never done so. Slip Op. 19. A proposed constitutional

amendment to split the district so that Orleans Parish

would constitute a district by itself was defeated by the

Louisiana voters in October, 1989 with the unofficial

Associated Press totals showing a vote of 151,342 for the

amendment and 451,845 against the amendment. Baton

Rouge State-Times, October 9th, 1989. In Orleans Parish

the amendment was defeated by a three-to-one majority,

with 16,526 voting for the amendment and 46,354 voting

against the am endm ent. New Orleans Times-Picayune,

October 8th, 1989.2

B. Prior Proceedings in this Litigation.

After the complaint was filed, respondents filed a

Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss for the failure of

the petitioners to state a claim upon which relief could be

2 Given that Orleans Parish is majority black in both popu

lation (55.2%) and registered voters (53.6%), and given that the

amendment was defeated three to one in Orleans Parish, it is

fair to surmise that blacks in Orleans Parish opposed the

amendment which would bring about the very same remedy

sought by petitioners herein.

4

granted. The district court agreed with respondents' con

tention that it was not the intention of Congress to apply

the word "representatives" in Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, to embrace members of the

judiciary. Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La.

1987). The district court drew a distinction between the

impartial functions performed by the judiciary without a

constituency and the functions performed by representa

tives who are not expected to be impartial but rather

reflective of the needs and wishes of their constituency.

659 F. Supp. at 186.

The petitioners appealed to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which reversed the judg

ment of the district court and remanded the case because

the Court concluded that Section 2 does apply to the

election of state court judges. Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d

1056 (5th Cir.), rehearing and rehearing en banc denied, cert,

denied sub nom. Roemer v. Chisom, 488 U.S. 955, 109 S.Ct.

390, 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988).

The petitioners then successfully moved to enjoin the

election of a Justice from the First Supreme Court District

during the regularly scheduled Fall, 1988 election. Chisom

v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La. 1988). The Fifth

Circuit stayed the injunction, 850 F.2d 1051 (5th Cir. 1988),

and ultimately reversed the injunction, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th

Cir. 1988).

After a trial on the merits, the district court dis

missed petitioners' statutory and constitutional claims.

Chisom v. Roemer, ___ F. Supp. ___ (E.D. La. 1989). The

court concluded:

5

that the petitioners had not proven that the use

of a multi-member electoral structure operates

to minimize or cancel out their ability to elect

their preferred candidates. As detailed in the

court's findings of fact, the statistical evidence

regarding judicial and non-judicial elections

shows that the blacks have had full access to the

political process and routinely elect their prefer

red candidates, often times joining forces with a

significant portion of the white electorate, and

thereby creating significant crossover voting.

Slip Op. at 40-41. The petitioners appealed the Voting

Rights Act decision.3 The Fifth Circuit remanded for dis

missal for failure to state a claim upon which relief may

be granted. 917 F.2d 187 (5th Cir. 1990). On remand the

case was dismissed. ___ F. Supp. ___ (E.D. La. 1990).

Thereafter, this Petition was filed.

--------------- ♦ — ------ — —

ARGUM ENT

I. THE FIFTH CIRCU IT CORRECTLY CONCLUDED

THAT SECTIO N 2(b) OF THE VO TIN G RIG H TS

ACT DOES NOT APPLY TO THE JUDICIARY.

A. The LULAC D ecision.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit dismissed the appeal in this case based on the en

banc decision of that Court in Latin American Citizens

Council #4434 v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990) (en

3 Petitioners did not appeal the district court's rejection of

their constitutional claim of intentional discrimination.

6

banc) (hereinafter "LULAC").4’ The plaintiffs in LULAC

challenged the county-wide, at-large election of trial

judges in Texas as violative of § 2(b) of the Voting Rights

Act and of the United States Constitution. The trial court

denied the constitutional claims, finding that the requisite

discriminatory intent had not been proven. 914 F.2d at

623. The trial court, however, did find "that the Texas law

produced an unintended dilution of m inority voting

strength" in violation of the "results" test of § 2(b) of the

Voting Rights Act. 914 F.2d at 623 (emphasis in original).

On appeal, a panel of the Fifth Circuit held that § 2(b) did

not apply to trial judges because they are single-member

officeholders who can be elected only at-large. 902 F.2d

293 (5th Cir. 1990).

The Fifth Circuit granted an en banc hearing sua

sponte. A majority held that judges are not "representa

tives" within the meaning of § 2(b) of the Voting Rights

Act and that the "results" test of § 2(b) does not apply to

the judiciary. 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990). Five judges

concurred, agreeing with the view of the panel that trial

judges are single-member officeholders. 914 F.2d at 634.

Chief Judge Clark also concurred, limiting the case to its

facts. 914 F.2d at 631. Only one Judge, Judge Sam John

son, dissented. 914 F.2d at 651. After the en banc opinion

was published, the panel in Chisom remanded this case to

4 On November 21, 1990, a group of plaintiffs-intervenors

in that case, the Houston Lawyers' Association and six individ

uals, filed a petition for a writ of certiorari asking this Court to

review the judgment and opinion of the Fifth Circuit in

LULAC. That petition is pending.

7

the district judge with orders to dismiss all Voting Rights

Act claims. 917 F.2d 187 (5th Cir. 1990).

B. The Genesis of § 2(b) of the Voting Rights Act.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 forbade

imposition or application of any "voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or pro

cedure" to prevent any citizen from voting on account of

race or color. 42 U.S.C. § 1973. This Court in City of Mobile

v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980),

held that enforcement of § 2 required proof of racially-

discriminatory intent.

Congress then passed the Voting Rights Act of 1982

amending § 2 to

restore the "results test" — the legal standard

that governed voting discrimination cases prior

to [the Supreme Court's] decision in Mobile v.

Bolden * * * * Under the "results test," plaintiffs

are not required to demonstrate the challenged

electoral law or structure was designed or main

tained for a discriminatory purpose.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 43 n. 8, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92

L.Ed.2d 25, 42 n. 8 (1986) (citations omitted). In writing

§ 2(b), Congress chose - with one significant exception -

the words of Justice White in White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973). Justice White

stated that plaintiffs' burden of proof was to show:

that its members had less opportunity than did

other residents in the district to participate in

the political processes and to elect legislators of

their choice.

8

412 U.S. at 766, 93 S.Ct. at 2339, 37 L.Ed.2d at 324

(emphasis supplied). Section 2(b) provides that a plaintiff

class of citizens must show:

that its members have less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to participate in

the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice.

42 U.S.C. § 1973(b) (emphasis supplied). As the majority

in LULAC recognized, the choice of the word "representa

tives" was a deliberate one: "the Congress was at some

pains to adapt and broaden the Court's phrases so as to

convey its precise meaning." 914 F.2d at 625.

C. This Court has always held that Judges are not

"representatives."

As stated in the prior section, § 2(b) applies to "rep

resentatives." Members of the legislative and executive

branches are certainly representatives, and the case law is

replete with decisions holding that § 2(b) applies to such

entities. See, e.g., Gomez v. City of Watsonville, 863 F.2d

1407 (9th Cir. 1988), cert, denied, ___U.S. ____ , 109 S.Ct.

1534, 103 L.Ed.2d 839 (1989) (city council and mayor);

Edge v. Sumter County School District, 775 F.2d 1509 (11th

Cir. 1985) (school board); Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398

(7th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1135, 105 S.Ct. 2673,

86 L.Ed.2d 692 (1985) (city aldermen); United States v.

Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir.),

appeal dismissed & cert, denied, 469 U.S. 976, 105 S.Ct. 375,

83 L.Ed.2d 311 (1984) (county commission); Velasquez v.

City of Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1984) (city council);

Brown v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

706 F.2d 1103 (11th Cir.), affirmed, 464 U.S. 1005, 104 S.Ct.

9

520, 78 L.Ed.2d 705 (1983) (board of school commission

ers); Jordan v. Winter, 604 F. Supp. 807 (N.D. M iss.),

affirmed, 469 U.S. 1002, 105 S.Ct. 416, 83 L.Ed.2d 343

(1984) (congressmen).

Judges, however, traditionally have not been consid

ered "representatives." This Court so held by affirming a

three judge court voting rights decision that the "one-

man, one-vote" concept does not apply to the judiciary.

Wells v. Edwards, 409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.Ed.2d

679 (1973). In refusing to apply "one-man, one vote"

precepts, the three judge court reasoned as follows:

[Ajs stated in Buchanan v. Rhodes [249 F. Supp.

860 (N.D. Ohio 1960), appeal dismissed, 385 U.S.

3, 87 S.Ct. 33, 17 L.Ed.2d 3 (1966)]:

"Judges do not represent people, they

serve people." Thus, the rationale behind

the one-m an, one-vote principle, which

evolved out of efforts to preserve a truly

representative form of government, is sim

ply not relevant to the makeup of the judici

ary.

"The State judiciary, unlike the legislature,

is not the organ responsible for achieving

rep resen tative governm ent." New York

State Association of Trial Lawyers v. Rock

efeller, 267 F.Supp. 148, 153.

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972) (three

judge court). The LULAC majority opinion reasons that

[i]t is impossible, given the single point at issue and the

simple reasoning stated, to believe that the majority of

the Supreme Court, in affirming Wells, did not concur in

that reasoning." 914 F.2d at 627.

10

Similarly, Justice Frankfurter has stated: "Courts are

not representative bodies. They are not designed to be a

good reflex of a democratic society." Dennis v. United

States, 341 U.S. 494, 575, 71 S.Ct. 857, 95 L.Ed. 1137,

1160-61 (1951) (Frankfurter, J., concurring in the judg

ment). And Justice Stewart has contrasted the Court's

duty with that of the people's representatives:

It is the essence of judicial duty to subordinate

our own personal views, our own ideas of what

legislation is wise and what is not. If, as I should

surely hope, the law before us does not reflect

the standards of the people of Connecticut, the

people of Connecticut can freely exercise their

true Ninth and Tenth Amendment rights to per

suade their elected representatives to repeal it.

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 530-31, 85 S.Ct. 1678,

14 L .Ed .2d 510, 542 (1965) (Stew art, J., d issenting)

(emphasis supplied).

D. Other Federal Courts have held that Judges are

not "representatives."

The lower federal courts have also held that judges

are not representatives. The plaintiffs in Holshouser v.

Scott, 335 F. Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C. 1971) (three judge

court), attacked the North Carolina system of nominating

judges by districts and electing them statewide, contend

ing that it denied voters equal protection of the laws.

They cited, inter alia, Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82 S.Ct.

691, 7 L.Ed.2d 663 (1962), and Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964). The court distin

guished these and the other cases because they "dealt

with the election of the representatives of the people -

11

officials who make laws, levy and collect taxes, and gen

erally manage and govern people." 335 F. Supp. at 930.

After discussing two precedents involving reapportion

ment, the court stated:

While Buchanan [v. Rhodes, 249 F. Supp. 860

(N.D. Ohio 1960), appeal dismissed, 385 U.S. 3, 87

S.Ct. 3 3 ,1 7 L.Ed.2d 3 (1966)] and [New York State

Association of Trial Laivyers v.j Rockefeller [267 F.

Supp. 148 (S.D.N.Y. 1967], deal with the appor

tionment of judges rather than their election,

they nevertheless point up the many pitfalls and

briar patches which the courts will encounter if

the one man, one vote principle is made applica

ble to the judiciary. The function of judges, con

trary to some popular views of today, is not to

make, but interpret the law. They do not govern

nor represent people nor espouse the cause of a

particular constituency. They must decide cases

exclusively on the basis of law and justice and

not upon the popular view prevailing at the

time.

335 F. Supp. at 932. The Holshouser case was affirmed by

the Supreme Court. 409 U.S. 807, 93 S.Ct. 43, 34 L.Ed.2d

68 (1972).

A similar system of electing judges in Georgia was

upheld in Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga.

1964) (three judge court). The court stated:

[E]ven assuming some disparity in voting

power, the one man-one vote doctrine, applica

ble as it now is to selection of legislative and

executive officials, does not extend to the judici

ary. Manifestly, judges and prosecutors are not

representatives in the same sense as are legisla

tors or the executive. Their function is to admin

ister the law, not to espouse the cause of a

particular constituency. Moreover there is no

12

way to harmonize selection of these officials on

a pure population standard with the diversity in

type and number of cases which will arise in

various localities, or with the varying abilities of

judges and prosecutors to dispatch the business

of the courts. An effort to apply a population

standard to the judiciary would, in the end, fall

of its own weight.

234 F. Supp. at 577.

In two New York cases the plaintiffs sought judicial

reapportionment on the basis of population, again relying

on legislative reapportionment cases such as Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964). In

New York State Association of Trial Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267

F. Supp. 148 (S.D.N.Y. 1967), the court rejected the com

parison, stating that:

The state judiciary, unlike the legislature, is

not the organ responsible for achieving repre

sentative government. Nor can the direction that

state legislative districts be substantially equal

in population be converted into a requirement

that a state distribute its judges on a per capita

basis.

* * * *

In contrast to legislative apportionm ent,

population is not necessarily the sole, or even

the most relevant, criterion for determining the

distribution of state judges. The volume and

nature of litigation arising in various areas of

the state bears no direct relationship to the pop

ulation of those areas.

267 F. Supp. at 153-54. A three judge court rejected a

similar suit in the Eastern District of New York, quoting

the Rockefeller opinion's statement that the state judiciary

13

is not "responsible for achieving representative govern

m ent." Kail v. Rockefeller, 275 F. Supp. 937, 941 (E.D.N.Y.

1967) (three judge court).

The Ohio judicial structure guaranteeing each county

at least one judge in the court of general jurisdiction came

under attack in Buchanan v. Rhodes, 249 F. Supp. 860 (N.D.

Ohio 1966), appeal dismissed, 385 U.S. 3, 87 S.Ct. 33, 17

L.Ed.2d 3 (1966), vacated, 400 F.2d 882 (6th Cir. 1968), cert,

denied, 393 U.S. 839, 89 S.Ct. 118, 21 L.Ed.2d 110 (1968).

Once again, the com plaint was predicated upon the

Supreme Court's reapportionment cases. The court noted

that when representatives to a legislative body are malap-

portioned, the voting strength of individual citizens

becomes unequal, causing a dilution of power. 249 F.

Supp. at 865. Judges, however, are not governed by such

a rule:

But in determining the reasonableness of a

judicial system which permits at least one judge

operating a court of general jurisdiction in each

county, we must recognize one glaring distinc

tion between the functions of legislators and the

functions of jurists. Judges do not represent peo

ple, they serve people.

249 F. Supp. at 865.5

5 Numerous other decisions make a similar distinction

between judges and representative officials. See Gilday v. Board

of Elections of Hamilton County, 472 F.2d 214, 217 (6th Cir. 1972)

(rejecting application of one-man, one-vote to judicial selection

in Ohio and holding "that equal protection does not require the

(Continued on following page)

14

E. The Term "representatives" is not a Synonym

for "elected officials".

Earlier sections of this Response demonstrate that

this Court and the lower federal courts do not consider

judges to be "representatives." This section argues that

the word "representative" as used in § 2(b) is not syn

onymous with "elected official" and should instead be

given its commonly understood meaning. This Court has

laid down definitive guidelines for construing language

which appears in Congressional acts.

In Consumer Products Safety Comm'n v. GTE Sylvania,

447 U.S. 102, 100 S.Ct. 2051, 64 L.Ed.2d 766 (1980), the

Court stated:

(Continued from previous page)

allocation of state judges on this basis"); Sagan v. Common

wealth of Pennsylvania, 542 F. Supp. 880, 882 (W.D. Pa. 1982)

(distinguishing judicial candidates from legislative and execu

tive candidates because judges administer the law rather than

espouse the cause of a particular constituency); Fahey v. Dar-

igan, 405 F. Supp. 1386, 1391 n. 6 (D.R.I. 1975) (holding one-

man, one-vote precepts inapplicable to "the selection of offi

cials not intended to serve in a representative role, such as

judges"); Buchanan v. Gilligan, 349 F. Supp. 569, 571 (N.D. Ohio

1972) (three judge court) (rejecting application of one-man,

one-vote to Ohio judiciary because "[t]he state judiciary is not

responsible for achieving representative government"); Romiti

v. Kerner, 256 F. Supp. 35, 46 (N.D. 111. 1966) (three judge court)

(expressing "little doubt" that "there is a valid distinction

between applying the 'one man, one vote' rule in a legislative

apportionment case to the election of a state supreme court

judiciary").

15

We begin with the familiar canon of statutory

construction that the starting point for interpret

ing a statute is the language of the statute itself.

447 U.S. at 108, 100 S.Ct. 2051, 64 L.Ed.2d at 773.

Four years later, in furtherance of this concept of

construction, the Court held in Escondido Mut. Water Co. v.

La Jolla Indians, 466 U.S. 765, 104 S.Ct. 2105, 80 L.Ed.2d

753 (1984):

Since it should be generally assumed that Con

gress expresses its purposes through the ordi

nary meaning of the words it uses, we have

often stated that " '[a]bsent a clearly expressed

legislative intention to the contrary, [statutory]

language must ordinarily be regarded as conclu

sive.' "

466 U.S. at 772, 104 S.Ct. 2105, 80 L.Ed.2d at 761 (citations

omitted).

And in Dickerson v. New Banner Institute, Inc., 460 U.S.

103, 103 S.Ct. 986, 74 L.Ed.2d 845 (1983), the Court said:

[W]e state once again the obvious when we note

that, in determining the scope of a statute, one is

to look first at its language * * * * If the language

is unambiguous, ordinarily it is to be regarded

as co n clu siv e u n less there is " 'a c learly

expressed legislative intent to the contrary.' "

460 U.S. at 110, 103 S.Ct. 986, 74 L.Ed.2d at 853 (citations

omitted).

The term "representatives" refers to those who serve

a specialized constituency and whose role is to represent

the needs and interests of that constituency. The term

"representatives" has never been commonly accepted as

including the judicial branch; indeed, the reverse is true -

16

namely, the judicial branch always has been treated as sepa

rate and distinct from the two representative arms of govern

ment.

A representative of a district, be it federal, state, or local,

exists to serve and favor his or her constituency, while

hopefully also working for the good of the governmental

jurisdiction as a whole. United States representatives are

expected to help obtain government contracts for their dis

tricts; no one, however, would expect a federal judge to

uphold such a contract citing as a reason the need of his area

for governmental business. State legislators are expected to

seek bridges and roads for their districts; no one, however,

would expect a state judge to mandate that such bridges and

roads be built merely because the people want them. City

councilmen are expected to promote drainage projects for

their council district; no one, however, would expect a city

judge to require them to keep his voters happy.

Judges thus are not representatives; further, they should

not be representatives. The larger the constituency, the less

parochial pressures can be brought to bear. An advantage to

at-large elections for judges is that judges can make the

difficult decisions without undue fear of dissatisfaction in

the electorate. A judge would be much less likely to vote

against the residents of a neighborhood on a zoning issue if

that judge was elected solely by that neighborhood. Justice

ought to be identical throughout a judicial system; electing

judges from neighborhoods, however, might make for a

system of individualized justice currently foreign to the

United States. Admittedly, many problems could be cured on

appeal; however, it can be extremely difficult to reverse a

detailed record of fact-finding even when the facts have been

slanted. Further, the petitioners here seek to make appellate

17

districts smaller also, again lessening the number and mix of

a judge's electorate.

Congress, had it wanted specifically to include judges

under Section 2(b) of the Voting Rights Act, could have done

so by substituting the term "elected official" for the term

"representative"; it did not do so. In a representative form of

government, such as ours, it is always true that a "represen

tative" is an "elected official"; however, the converse is not

always true.

Representatives have a constituency which numbers in

the hundreds to hundreds of thousands, to each of whom

they owe fidelity and from many of whom they are likely,

sooner or later, to receive correspondence or a telephone call

or even perhaps a personal visit. Judges have but one con

stituency, the blindfolded lady with the scales and sword.

F. The Fundamental Difference Between "representa

tives" and Members of the Judiciary is Deeply

Rooted in this Country's History.

In holding that "the judiciary serves no representative

function whatsoever," 914 F.2d at 625, the LULAC Court

quoted Professor Eugene Hickok as stating that, "The judici

ary occupies a unique position in our system of separation of

powers, and that is why the job of a judge differs in a

fundamental way from that of a legislator or executive."

Hickok, "Judicial Selection: The Political Roots of Advice and

Consent" in Judicial Selection: Merit, Ideology and Politics 5

(National Legal Center for the Public Interest 1990), quoted at

914 F.2d at 926.

Other scholars have also recognized this difference. Pro

fessor G. Edward White has written in The American Judicial

Tradition that the American judicial tradition emerged with

18

Chief Justice John Marshall.6 A core element of that tradition

has always included "a measure of true independence and

autonomy for the appellate judiciary from the other two

branches of government." Judicial Tradition 9. Professor White

summarized Chief Justice Marshall's views concerning the

judiciary as follows:

An independent judiciary was logically the ulti

mate necessity in Marshall's jurisprudence, the cul

mination of his beliefs about law and government.

He sought to show that judicial independence was

not merely a side effect of federalism but a first

principle of American civilization * * * * Against

the potential chaos attendant on mass participatory

democracy, republicanism erected the institutional

buffers of legislative representatives and an inde

pendent judiciary. The excesses of the people were

moderated by representation, a process by which

their passionate demands were reformulated by an

enlightened and reasonable class of public ser

vants. The need of the populace for an articulation

of their individual rights under law was met by the

presence of a body of judges not beholden to the

masses in any immediate, partisan sense.

Judicial Tradition 18, 20.

Chief Justice Marshall's vision of the American judi

cial tradition was not unique. A lexander Ham ilton

"envisaged jud icial review as an exercise in politics

through which an independent judicial elite could temper

the democratic excesses of legislatures by affirming the

republican political balances inherent in the Constitu

tion." Judicial Tradition 24. Some of the Founding Fathers

6 Citations are hereinafter abbreviated as Judicial Tradition.

Page references refer to the 1978 Oxford University Press

paperback edition.

19

thought an independent judiciary necessary because

"even a government made up of the people's representa

tives was not a sufficient buffer against the excesses of

the m ob." Judicial Tradition 320.

This American judicial tradition has also been appli

cable to the state judiciary. Professor White commented

that the state constitutions "were patterned on the federal

Constitution, with its tripartite division of powers." Judi

cial Tradition 109. James Kent, Chief Judge of the New

York Supreme Court and later Chancellor of New York,

"viewed the judiciary as a buffer between established

wealth and the excessively democratic legislature." Judi

cial Tradition 112. Much more recently, Chief Justice Roger

Traynor of the California Supreme Court wrote that

judges "enjoyed a 'freedom from political and personal

pressures and from adversary bias' [and that] [t]heir

'environment for work' was 'independent and analyt

ically objective.' " Judicial Tradition 296, quoting Traynor,

"Badlands in an Appellate Judge's Realm of Reasons," 7

Utah L.Rev. 157, 167, 168 (1960).

Professor W hite traced "modern liberalism" trends

throughout the Twentieth Century. According to this

political theory, judges "were not, by and large, represen

tatives of the people, and their nonpartisan status insu

lated them from the waves of current opinion." Judicial

Tradition 320. Legislatures, on the other hand, "were 'rep

resentative of popular opinion' and could 'canvass a wide

spectrum of views.' " Judicial Tradition 322. One Twentieth

Century Justice, Felix Frankfurter, has called the judiciary

20

the "antidemocratic, unrepresentative" branch of govern

ment." Judicial Tradition 367.7

Various legal theorists have also stated that judges are

not "representatives." Perhaps the most provocative book to

appear on judicial review during the last few years is Democ

racy and Distrust by Professor John Hart Ely.8 Professor Ely

contrasts the role of the courts with the role of the represen

tative branch of government, the legislative branch. He

sought an approach to judicial review "not hopelessly incon

sistent with our nation's commitment to representative

democracy." Democracy and Distrust 41. In his book, Professor

Ely developed a representation-reinforcing theory of judicial

review in which the non-representative branch (the judici

ary) would review legislation to determine the motivation of

the representative branch (the legislature) to make sure that

the views of all groups were represented in lawmaking. He

concluded by stating that "constitutional law appropriately

exists for those situations where representative government

cannot be trusted." Democracy and Distrust 183.

Professor Alexander Bickel spoke of the importance of

judicial independence in The Supreme Court and the Idea of

Progress.9

7 Professor Lawrence Friedman also has written about the

history of a strong, independent judiciary in both federal and

state governmental systems. L. Friedman, A History of American

Law 116, 118 (Simon & Schuster 1973 paperback edition).

8 Page references are to the 1980 Harvard University Press

hardbound edition.

9 Citations are hereinafter abbreviated as Supreme Court

and Progress. Page references refer to the 1978 Yale University

Press paperback edition.

21

The restraints of reason tend to ensure also

the independence of the judge, to liberate him

from the demands and fears - dogmatic, arbi

trary, irrational, self-or group-centered, - that so

often enchain other public officials. They make

it possible for the judge, on some occasions, at

any rate, to oppose against the will and faith of

others, not merely his own will or deeply-felt

faith, but a method of reaching judgments that

may com m and the allegiance, on a second

thought, even of those who find a result dis

agreeable. The judge is thus buttressed against

the world, but what is perhaps more significant

and certain, against himself, against his own

natural tendency to give way before waves of

feeling and opinion that may be as momentary

as they are momentarily overwhelming.

* * * *

The independence of the judges is an absolute

requirement if individual justice is to be done, if a

society is to ensure that individuals will be dealt

with in accordance with duly enacted policies of

the society, not by the whim of officials or of mobs,

and dealt with evenhandedly, under rules that

would apply also to others similarly situated, no

matter who they might be.

Supreme Court and Progress 82, 84.

Professor Bickel contrasted the Court with the people

and its representatives, stating, "Virtually all important

decisions of the Supreme Court are the beginnings of

conversations between the Court and the people and

their representatives." Supreme Court and Progress 91.10

10 Supreme Court and Progress also contains much material

on reapportionment. Supreme Court and Progress 35, 158-59,

(Continued on following page)

22

II. IF THE ONE-MAN, ONE-VOTE REQUIREMENT

DOES NOT APPLY TO THE JUDICIARY, THE CON

CEPT OF MINORITY VOTE DILUTION SET FORTH

IN § 2(B) DOES NOT APPLY TO THE JUDICIARY.

This Court has held that the one-man, one-vote require

ment does not apply to the judiciary. Wells v. Edwards, 409

U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.E.2d 679 (1973). If this require

ment is inapplicable, the concept of minority vote dilution in

at-large districts is similarly inapplicable to the judiciary. As

the Fifth Circuit held in LULAC,

Absent the one-person, one-vote rule - that the

vote of each individual voter must be roughly

equal in weight to the vote of every other individ

ual voter, regardless of race, religion, age, sex, or

even the truly subjective and uniquely individual

choice of where to reside - there is no requirement

that any individual's vote weigh equally with that

of anyone else. This being so, and no such right

existing, we can fashion no remedy to redress the

non-existent wrong complained of here.

The notion of individual vote dilution, first

developed by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506

(1964), was the foundation for the concept of

minority vote dilution to be later elaborated in

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 91 S.Ct. 1858,

29 L.Ed.2d 363 (1971), White v. Regester, [412

U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973)],

and Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th

Cir. 1973). In d iv id u a l vo te d ilu tio n w as

remedied by the Court through the concept of

(Continued from previous page)

168-73. Never in that discussion is there any intimation that

reapportionment requires judicial redistricting. Indeed, such a

notion would run counter to his strong arguments for judicial

independence.

23

one-person, one-vote - the guarantee of sub

stantial equality among individual voters. With

that guarantee in mind, remedial schemes to

combat minority vote dilution were devised on

a case by case basis.

914 F.2d at 627 (emphasis in original). The Senate Report

concerning the 1982 amendment to the Voting Rights Act

states "[t]he principle that the right to vote is denied or

abridged by dilution of voting strength derives from the

one-person, one-vote reapportionment case of Reynolds v.

Sims." S.Rep.No. 417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess., reprinted in

1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News at 177, 196.

The key issue, therefore, is whether Section 2(b) of

the Voting Rights Act enshrines the "one-man, one-vote"

principle as the touchstone test. If it does, then it cannot

be used to analyze judicial elections, because the "one-

man, one-vote" test was expressly rejected as applying to

the judiciary in Wells v. Edwards, 347 RSupp. 453 (M.D.

La. 1972), affirmed 409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.Ed.2d

679 (1973).

The express language of the plurality opinion in Gin-

gles, bolstered by the language of the concurring opin

ions, shows that Section 2(b) is solely a "one-man, one-

vote" litmus test. Justice Brennan, in speaking for the

plurality, began by noting that when Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act was amended in 1982 to add Section

2(b), the Congressional revision was a response to the

plurality opinion in Mobile v. Bolden, 478 U.S. at 35, 106

S.Ct. at 2759, 92 L.Ed.2d at 37. The plurality in Gingles, in

interpreting what evidence it takes under Section 2(b) to

prove a Section 2(a) violation, established a three-fold

test:

24

First, the minority group must be able to dem

onstrate that it is sufficiently large and geo

graphically compact to constitute a majority in a

single-member district. * * * Second, the minor

ity group must be able to show that it is politi

cally cohesive. * * * Third, the minority must be

able to dem onstrate that the white majority

votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it, - in the

absence of special circum stances, such as a

m i n o r i t y c a n d i d a t e r u n n i n g u n o p p o s e d

* * * usually to defeat the minority's preferred

candidate * * * * In establishing this last circum

stance, the minority group demonstrates that

the submergence in a white multi-member dis

trict impedes its ability to elect its chosen repre

sentatives.

478 U.S. at 50-51, 106 S.Ct. at 2766-67, 92 L.Ed.2d 46-47.

As Justices O'Connor, Powell, Rehnquist, and Chief

Justice Burger recognized in their concurring opinion in

Gingles, this three-fold test equates to a requirement of

proportional representation; i.e., one-man, one-vote. Jus

tice O'Connor, speaking for these Justices, stated:

Third, although the Court does not acknowledge

it expressly, the combination of the Court's defi

nition of minority voting strength and its test

for vote dilution results in the creation of a right

to a form of proportional representation in favor

of all geographically and politically cohesive

minority groups that are large enough to consti

tute m ajorities if concentrated within one or

more single-member districts.

478 U.S. at 85, 106 S.Ct. at 2784-2785, 92 L.Ed.2d at 69.

In my view, the C ourt's test for m easuring

minority voting strength and its test for vote

dilution, operating in tandem, come closer to an

absolute requirement of proportional represen

tation than Congress intended when it codified

the results test in § 2.

25

478 U.S. at 94, 106 S.Ct. at 2789, 92 L.Ed.2d at 74.

The Court's standard for vote dilution, when

combined with its test for undiluted minority

voting strength, makes actionable every devia

tion from usual, rough, proportionality in repre

sentation for any cohesive minority group as to

which this degree of proportionality is feasible

within the framework of single-m ember dis

tricts. Requiring that every minority group that

could possibly constitute a majority in a single

member district be assigned to such a district

would approach a requirement of proportional

representation as nearly as is possible within the

framework of the single-member districts. Since

the Court's analysis entitles every such minority

group usually to elect as many representatives

under a multi-member district school, it follows

that the Court is requiring a form of proportional

representation.

478 U.S. at 97, 106 S.Ct. at 279, 92 L.Ed.2d at 76-77

(emphasis supplied).

Justice O'Connor, and the other Justices who joined

in her concurring opinion, recognized that proportional

representation (one-man, one-vote) is the result of the

plurality's opinion. It was exactly this type of propor

tional representation that the.plurality in Mobile v. Bolden

had rejected in its analysis of both Section 2 (pre-1982

amendments) and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments:

The theory of [Justice Marshall's] dissenting

opinion - a theory much more extreme than that

espoused by the District Court or the Court of

Appeals - appears to be that every "political

group," or at least every such group that is a

minority, has a federal constitutional right to

e l e c t c a n d i d a t e s in p r o p o r t i o n to i t s

numbers. * * *

26

Whatever appeal the dissenting opinion's view

may have as a matter of political theory, it is not

the law.

446 U.S. at 75, 100 S.Ct. at 1504, 64 L.Ed.2d at 63-64.

The plurality in Mobile recognized that what is now

Section 2(a) does not require a "proportionality" test.

Section 2(a) was not substantially changed in the 1982

amendments. Thus, if Section 2(b) establishes a "one-

man, one-vote" test, then under Wells it cannot be used

against the judiciary.

The petitioners may take the position that there is a

distinction between a "proportionality" test and a "one-

man, one-vote" test. Such an argument would be unavail

ing, as the plurality opinion in Mobile v. Bolden expressly

recognized.

After discussing (and rejecting) the dissent's argu

ment concerning proportionality, the plurality in Mobile

went further and determined that the "proportionality"

argument equated to a "one-man, one-vote" test.

The dissenting opinion erroneously discovers

the asserted entitlement to group representation

within the "one person, one vote" principle of

Reynolds v. Sims, supra, [377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct.

1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964)] and its progeny.

446 U.S. at 77, 100 S.Ct. at 1505, 64 L.Ed.2d at 65. As

Mobile v. Bolden recognized, the term "vote dilution" is

equivalent to holding that there is a "one-man, one-vote"

test. 446 U.S. at 78, 100 S.Ct. at 1505, 64 L.Ed.2d at 65-66.

As the plurality in Mobile v. Bolden stated:

There can be, of course, no claim that the "one-

person, one-vote" principle has been violated in

this case * * * it is therefore obvious that

nobody's vote has been "diluted" in the sense in

which that word was used in the Reynolds case.

27

* * *

It is, of course, true that the right of a person to

vote on an equal basis with other voters draws

much of a significance from the political associa

tions that its exercise reflects, but it is an alto

gether different m atter to conclude that political

groups themselves have an independent consti

tutional claim to representation.

446 U.S. at 78, 100 S.Ct. 1505, 1507, 64 L.Ed.2d at 65, 66.

Because Gingles involves only the interpretation of

Section 2(b), and because Wells prohibits the use of a

"one-m an, one-vote" test involving judicial elections, it is

clear that the Section 2(b) results test cannot be used to

prove a violation of Section 2(a) in judicial elections.

The concept of dilution of group voting strength

[which is embodied in subsection (b) of amended Section

2] rests on two assumptions: (1) that each person's vote

should have the same weight as another person's vote,

and (2) that a given (protected) group should wield

roughly the aggregate voting strength of its members. See

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1303 (5th Cir. 1973). If

the first assumption is not true, the second cannot be

made. For without the assumption of substantial equality

among voting shares made possible by the one-man, one-

vote principle, no aggregate measure of minority voting

strength - and therefore no measure of dilution of that

strength - is conceivable. Because the one-man, one-vote

rule does not apply to the judiciary, the conceptually

dependent notion of m inority group vote dilution,

embodied in subsection (b), has no field of operation in

judicial elections.

This argument has nothing to do with statutory inter

pretation, does not depend on a particular construction of

the word "representative" as used in subsection (b), and

28

is not based on whether Congress intended that amended

Section 2 have some field of operation with respect to

judicial elections. It is, instead, based on an explanation

of why, regardless of what breadth Congress intended for

amended Section 2, minority group vote dilution - as that

concept has developed in the voting rights jurisprudence

- simply cannot exist unless the one-man, one-vote rule

applies.

Thornburg v. Gingles, the Court's definitive exegesis of

Section 2 vote dilution, sharpens this point. In her con

curring opinion, Justice O'Connor, joined by Powell,

Rehnquist, and Chief Justice Burger, notes that "[i]n order

to evaluate a claim that a particular multimember district

or single-m em ber d istrict has diluted the m inority

group's voting strength to a degree that violates § 2 . . . it

is . . . necessary to construct a measure of 'undiluted'

minority voting strength." Gingles, 478 U.S. at 88, 106

S.Ct. 2786, 92 L.Ed.2d at 71. There is no doubt that the

yardstick adopted by the Gingles Court - a calculation of

the m inority's potential voting strength in a single-mem

ber district system - rests on the assumption that the one-

man, one-vote rule applies and that each district has

roughly the same population. See 478 U.S. at 50-51 n. 17,

89-90, 106 S.Ct. 2766-67 n. 17, 2787, 92 L.Ed.2d at 46-47

n.17, 72. Otherwise, to paraphrase Justice Harlan, the

Court would be unable even to measure what it purports

to equalize. Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. at 169, 91 S.Ct.

1883, 29 L.Ed.2d at 391 (Harlan J., separate opinion).

Without the measure of individual voting strength

provided in legislative cases by the one-man, one-vote

rule, Gingles’ first prong is meaningless in the judicial

29

context. It is always possible to construct a geograph

ically compact black voting majority district by continu

ing to reduce the total population in that district down to,

if necessary, a minimum of one. There ARE no "judicially

discernable and manageable standards" by which a court

could find that a given judicial election system does not

dilute minority voting strength if the population size of

the hypothetical single-member subdistrict can be con

tracted or expanded at will. See Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186,

217, 82 S.Ct. 691, 7 L.Ed.2d 663, 686 (1962). As one lower

court has held, "A n effort to apply a population standard

to the judiciary would, in the end, fall of its own weight."

Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575, 577 (N.D. Ga. 1964).

--------------- •--------------

CONCLUSION

This Court has always recognized the importance of

an independent judiciary, holding in Chandler v. Judicial

Council, 398 U.S. 74, 90 S.Ct. 1648, 26 L.Ed.2d 100 (1970):

"There can, of course, be no disagreement among us as to

the imperative need for total and absolute independence

of judges in deciding cases or in any phase of the decisio

nal function." 398 U.S. at 84, 90 S.Ct. 1648, 26 L.Ed.2d at

108. In a dissent in the same case, Justice Douglas stated,

"An independent judiciary is one of this Nation's out

standing characteristics." 398 U.S. at 136, 90 S.Ct. 1648, 26

L.Ed.2d at 137 (Douglas, J., dissenting).

A quarter of a century ago this Court declared, "Leg

islators represent people, not trees or acres." Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 562, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506, 527

(1964). Unlike legislators, judges are not "instruments of

government elected directly by and directly representa

tive of the people." 377 U.S. at 562, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12

30

L.Ed.2d at 527. Making judges representatives would do

violence to (and perhaps destroy) the American concept

of an independent judiciary.

For the reasons set forth herein, this Court should

deny the Petition for Certiorari.

All of the above and foregoing is thus respectfully

submitted.

R obert G . P ugh

Counsel of Record

R obert G . P ugh, J r .

Of the Law Firm of

P ugh, P ugh & P ugh

Commercial National Tower

Suite 2100

333 Texas Street

Shreveport, LA 71101-5302

(318) 227-2270

M oise W. D ennery

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1241

M . T ruman W oodward, J r .

909 Poydras Street

Suite 2300

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 569-7100

SPECIAL ASSISTANT

A. R. C hristovich

2300 Pan American Life

Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 561-5700

ATTORNEYS GENERAL

W illiam J. G uste, Jr.

Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 568-5575

December 14th, 1990.

■ ........... 1 . ' : .... . • .................