Lawson v. United States of America Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawson v. United States of America Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1949. ffbd4fc2-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c3c2572-ca9f-4f59-829c-a9b2b80e789d/lawson-v-united-states-of-america-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

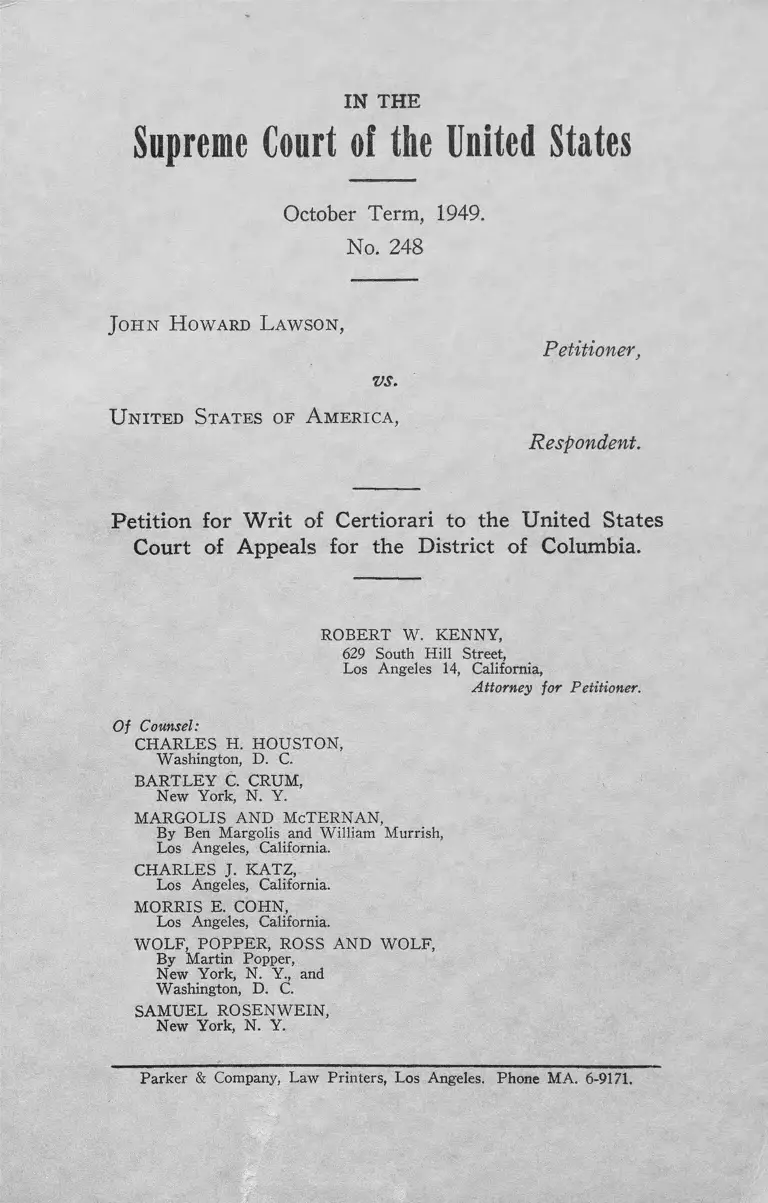

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949.

No. 248

J o h n H o w a r d L a w s o n ,

Petitioner,

vs.

U n i t e d S t a t e s o f A m e r i c a ,

Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

ROBERT W. KENNY,

629 South Hill Street,

Los Angeles 14, California,

Attorney for Petitioner.

Of Counsel:

CHARLES H. HOUSTON,

Washington, D. C.

BARTLEY C. CRUM,

New York, N. Y.

MARGOLIS AND M cTERNAN,

By Ben Margolis and William Murrish,

Los Angeles, California.

CHARLES J. KATZ,

Los Angeles, California.

MORRIS E. COHN,

Los Angeles, California.

W OLF, POPPER, ROSS AND WOLF,

By Martin Popper,

New York, N. Y., and

Washington, D. C.

SAMUEL ROSENWEIN,

New York, N. Y.

Parker & Company, Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone MA. 6-9171.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Statement of matter involved.............................. ........................... . 2

Statement as to jurisdiction.................................................. ............... 20

Statutes involved .................................................................................... 20

Questions presented ........................................... 23

Reasons for granting the writ.................................... 27

I.

The Committee’s utilization of congressional power, as an agency

of government, to compel disclosure of private political opin

ion and association is forbidden: (a) by the First, Fourth

and Fifth Amendments as unwarranted invasion into the pri

vate rights of individuals, and (b ) by the Ninth and Tenth

Amendments as unwarranted invasion into the area o f gov

ernmental powers reserved exclusively to the sovereign people 36

A. The Committee’s utilization of congressional power, as an

agency of government, to compel disclosure of private

political opinion and association is forbidden by the

First, Fourth and Fifth Amendments as unwarranted in

vasion into the private rights of individuals...................... 36

(1 ) The oath ex officio........................................................... 37

(2 ) The right of the individual to be let alone with re

spect to his beliefs and associations.......................... . 43

11.

B. The Committee’s utilization of congressional power, as an

agency of government to compel disclosure of private

political opinion and association, is forbidden by the

Ninth and Tenth Amendments as an unwarranted inva

sion into the area of governmental power reserved ex

PAGE

clusively to the sovereign people............................................. 51

(1) Petitioner’s position ................................... .................... 51

(2 ) The opinion below.................. ......................................... 55

II.

This particular inquiry into the Hollywood motion picture in

dustry lay entirely outside the lawful bounds of the power of

the House Committee because it constituted a censorship of

the content of motion pictures and thereby violated the First

Amendment ... ...................................................... _........................... 61

III.

The Committee as an agency of government used its powers

under Section 121 of legislative Reorganization Act of 1946

to impose a blacklist against the petitioner and other named

individuals, and thereby placed itself above the Constitution

and disregarded the elementary requirements of due process

of law in that: (1 ) It usurped the power to legislate con

fided by the Constitution to the concurrent action of both

Houses of Congress and the President; (2 ) It exercised

such power in a manner prohibited even to the entire legis

lature; (3 ) It invaded the area delegated exclusively to the

judiciary; and (4 ) It exercised such judicial power in a

manner prohibited even to the judiciary.......................... ............. 69

111.

IV.

The statute creating the House Committee on Un-American A c

tivities on its face and particularly as construed and applied is

unconstitutional in that: (1 ) It permits investigation of,

and as construed and applied has been used to investigate,

the content of speech and ideas, an area in which no legisla

tion is possible thereby exceeding the boundaries of legislative

power under Article I of the Constitution; (2 ) It permits

the very process of investigation to be used, and as generally

construed and applied it has been used, to expose and stigma

tize the content of any and all speech and ideas disapproved

by the members of the Committee, thereby impeding and plac

ing a burden upon free thought, speech and association in

violation of the First, Ninth and Tenth Amendments, and

(3 ) The statute is so vague and ambiguous that, as applied

in a criminal case, it violates the First Amendment and the

due process clause of the Fifth Amendment....... .................... . 77

V.

The trial court committed numerous prejudicial errors and

denied petitioner a fair trial under the Sixth Amendment by

its rulings, instructions and comments........................................... 88

A. The Subcommittee before which petitioner appeared was

not shown to be a lawfully constituted tribunal, and the

trial court committed prejudicial error by reason of its

rulings and instructions which prevented the jury from

considering this fact in reaching its verdict..................... 88

PAGE

iv.

B. The charge of the court that (a ) a non-responsive reply,

or (b ) a reply that seems unclear to the jury is per se

conclusive proof of a refusal to answer, and the com

ments of the court to the effect that petitioner was not

trying to answer the question constituted prejudicial

error ................. .......................................................................... 95

C. The trial court committed prejudicial error in refusing to

permit cross-examination of the principal prosecution

witness, J. Parnell Thomas................................ .....................101

D. The court committed prejudicial error in excluding peti

tioner’s evidence that the Committee failed to certify to

the House of Representatives all of the material facts

relating to the alleged failure to answer............................ ....104

E. Utilization of government employees as jurors in this

particular case involving the House Committee on Un-

American activities as the governmental agency directly

interested in the prosecution, constituted prejudicial

error ....................................'........................................................ 105

F. The trial court erred in denying petitioner’s challenge and

motion to dismiss the jury panel in that ( 1) the use of

questionnaire containing the question whether the pros

pective juror holds any “ views opposed to the American

form of government” was improper and invalidated the

jury panel, particularly in the present case, and (2) the

petitioner’s right to an impartial jury drawn from a

cross-section of the community was abrogated by the

establishment of qualifications for jury service other than

those required by statute and which limited the represen

tative character of the jury..................................................... 108

PAGE

V.

TA B LE OF A U T H O R ITIE S CITED

Cases page

Arine v. United States, 10 F. 2d 778...............................................103

Barnes, Matter of, 207 N. Y. 108..... ........................................11. 45

Barsky v. United States, 167 F. 2d 241...................................... 59, 68

Bihn v. United States, 328 U. S. 633............................................... 99

Bollenbach v. United States, 326 U. S. 606'............................ 100, 103

Bowe v. Commonwealth, 320 Mass. 230.............................. ............ 51

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616.............................. ....32, 43, 48

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252...................... ..42, 52, 54, 57, 68

Bridges v. Wixen, 326 U. S. 135................................................. 51, 59

Brown v. Baskin, 78 Fed. Supp. 933..... .......... .............................. 42

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 3101 U. S. 296..................................... 52

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U. S. 238......................................... 81

Catlette v. United States, 132 F. 2d 902........................................... 71

Chapman, In re, 166 U. S. 661....... .......... .................... .............32, 104

Christoffel v. United States, No. 528, Oct. Term 1948, decided

June 20, 1949......................................................... 33, 34, 90, 91, 93

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445......................................... 87

Coffin v. United States, 156 U. S. 432.—.............. 47

Coleman v. Miller, 307 U. S. 456..................................................... 94

Crawford v. United States, 212 U. S. 193....... .......................... ....107

Cummings v. Missouri, 71 U. S. 277............................ 40, 42, 63, 71

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353...... ...................................... 51, 52

Edward’s case, 13 Co. Rep. 9, 77 Eng. Rep. 1421........................ 38

Estep v. United States, 327 U. S. 114............................................. 76

Federal Trade Commission v. American Tobacco Co., 264 U.

S. 298 ....................................................... ......................................... 58

Fields v. United States, 164 F. 2d 97, 82 U. S. App. D. C. 354.. 96

Fleishman v. United States (U . S. C. A.-D. C. No. 9852, de

cided April 8, 1949, Govt. Petition for cert., No. 838, Oct.

Term, 1948) .................. ..................................................................... 93

VI.

Frankfeld, Ex parte, 32 Fed. Supp. 915............................................ 32

Gideon v. United States, 52 F. 2d 427.... 109

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652................................................ 52

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60..................................... 110

Greenfield v. Russell, 292 111. 392..................................................... 32

Grosjean v. American Press, 297 U. S. 233..............54, 62, 63, 86

Hague, Ex parte, 150 Atl. 322........................................................ . 45

Hannegan v. Esquire, 327 U. S. 146........................... ...................61, 63

Harriman v. Interstate, 211 U. S. 407............................................. 32

Harris v. United States, 331 U. S. 145........ ................................. 34

Hearst v. Black, 87 F. 2d 68............................ ............ .................... 32

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242....... ........................... ............ . 52

Interstate Commerce v. Brimson, 154 U. S. 447........................ . 32

Jones v. Opelika, 319 U. S. 103................................................... 53, 63

Jones v. S. E. C„ 298 U. S. 1...............................................32, 48, 76

Kansas v. Colorado, 206 U. S. 46................ 81, 82

Kilbourne v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 164.......................................31, 58

Kovacs v. Cooper, 93 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 379.............................. 79

Kraus v. United States, 327 U. S. 614.................... ......................... 99

Kwock Jan Fat v. White, 253 U. S. 454.......................................104

Leubuscher v. Commissioner, 54 F. 2d 998..................................... 79

Marshall v. Gordon, 243 U. S. 521....... ........................................... 32

Martin v. Hunter’s. Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304....................................52, 81

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316.......................................52, 81

McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U. S. 175...........................32, 45, 76, 82

Meyers v. United States, 171 F. 2d 800........................................... 90

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105................ .............53, 54, 63

Murphy and Glover Test Oath Cases (1867), 41 Mo. 340.......... 40

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697.............................. ..................... 66

Newport Bridge Co. v. United States, 105 U. S. 470................ 52

PAGE

Niznick v. United States, 173 Adv. F. 2d 328.......................... 75, 76

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U. S. 438.................................... 45

Pacific Railroad Commission, 32 Fed. 241.............................. ........ 31

Parker v. County of Los Angeles, Oct. Term 1949, No. 49.......... 28

Patton v. United States, 281 U. S. 276.............................................100

People v. Cleveland, 271 111. 226, 110 N. E. 843........................ 94

People v. Webb, 5 N. Y. Supp. 855................ ................................. 45

Quercia v. United States, 289 U. S. 469........................................ 100

Respublica v. Gill, 3 Yates 429, 161 U. S. 633............................ 42

Schechter v. United States, 295 U. S. 495..................................... 82

Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U. S. 118........... 51, 52, 59, 80

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91.......................................71, 76

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1................................... .................... 78

Sinclair v. United States, 279 U. S. 263..... ............ ...... ................ 58

Sinclair v. United States, 279 U. S. 747.............................. ........ . 32

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128...................... .....................................110

State ex rel. School District of Afton v. Smith, 336 Mo. 703,

80 F. 2d 858....................................................................................... 94

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217.............................. 110

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516............51, 52, 53, 54, 57, 79, 83

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88.............................. 53, 66, 83, 84

United States v. Ballard, 322 U. S. 78............................................ 79

United States v. Ballin, Joseph & Co., 44 U. S. 1.................... 91

United States v. Butler, 297 U. S. 1................................................ 81

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299.................................... 71, 76

United States v. Curtis, 107 U. S. 671, 27 L. Ed. 534............. 94

United States v. Dennis, cert, granted June 27, 1949, No.

436 ...................................................................................... 34, 105, 107

United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629......................................... 81

United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303......................71, 72, 76, 78

United States v. Murdock, 290 U. S. 392.............................. 96, 100

vii.

PAGE

PAGE

United States v. Norris, 300 U. S. 564.....................................32, 90

United States v. Paramount, 334 U. S. 131........ ......................... 61

United States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214............................................. 87

United States v. Seymour, 50 Fed. 2d 930..................................... 90

United States v. Smith, 286 U. S. 6............................................. 94

United States v. Trierweiler, 52 Fed. Supp. 4.............................. 71

Watts v. Indiana, No. 610, Oct. Term, 1948................................ 40

West Virginia v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624.......................... 33, 55, 83

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357............................................... 52

Wilson v. United States, 149 U. S. 60............................................. 39

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507.................................. ............. 87

Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356...........................................52, 84

M iscellaneous

Chafee, Free Speech, p. 529....... ........................................................ 62

Congressional Globe, 29th Cong., 1st Sess., 1845-46, App. p.

455 ............................................................ 50

Congressional Globe, 34 Cong., 3rd Sess., 439, 440, Jan. 23,

1857 .................................................... 31

Congressional Record, Nov. 24, 1947, p. 10890............................... 10

Dimock, Congressional Investigating Committees, pp. 161, 162,

163 ............................... 32

Executive Order No. 9835—................... .....106

Funk and Wagnalls International Dictionary (1935 E d.), p.

1985 ................................................................................. 79

House of Representatives Rep. No. 2, 76th Cong., 1st Sess.,

13 (1939) ............................................... 82

House of Representatives Rep. No. 1, 77th Cong., 2nd Sess.,

16 (1940) ........................................................................................... 82

House of Representatives Report No. 2742, 79th Cong., 2nd

Sess., 16 (1940) ............................... 82

Lea, History of the Inquisition, pp. 400, 405................................... 37

viii.

IX.

Maguire, Attack of the Common Lawyers on the Oath Ex

Officio, in Essays in History and Political Theory, Harvard

(1936), p. 199 ................................................................................... 38

McGeary, The Developments of Congressional Investigative

Power, p. 104................................................ ...................................... 83

New York Herald-Tribune, Dec. 2, 1947, White.......................... SO

Report of the Joint Committee on the Organization of Con

gress— pursuant to House Cong. Res. 18— Rep. No. 1011

in Sec. 1, Subd. 6.............................................................................. 91

Swisher, Stephen J. Field, Craftsman of the Law (Wash.

1930), p. 152....................................................................................... 42

25 W ho’s Who, 1948, p. 1436.................... 2

Woodley, Thaddeus Stevens (Pa. 1934).................................... 48, 49

H oly Bible

Matthew 2 6 :33 ....................................................................................... 48

Statutes

Act of Aug. 22, 1935, Chap 605 (49 Stats. 682)....................... . 22

Act of June 22, 1938, Chap. 595 (54 Stats. 942 ; 2 U. S. C.,

Sec. 194) ...... 104

Act of June 25, 1948, Chap. 646 (62 Stats. 869, 28 U. S. C.,

Sec. 1254, Subsec. 1 ) ....................................................................... 20

Code for the District of Columbia, Title X I, Sec. 1417......... 22, 108

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 121..............16, 88, 91

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 121(b) (P . L. 601,

Chap. 753, 79 Cong., 2d Sess., 60 Stat. 828, amends Rule

X I (1 ) (2 ) of Rules of the House of Representatives)—.21, 78, 82

PAGE

Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, Sec. 133(b)..... ............ 94

Public Law 601...................................................................................... 30

Revised Statutes, Sec. 102 (Chap. 594, Act of June 22, 1938,

52 Stat. 942, U. S. C., Title II, Sec. 192)............................ 1, 20

Rules of the Supreme Court, Rule 38, par. 7.................................. 2

X.

United States Code, Title 2, Sec. 192.......................... ..................... 31

United States Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 9 ...... ....................... ..24, 25

United States Constitution, First Amendment..............................

................ .......................... 4, 24, 25, 32, 36, 44, 45, 58, 60, 79, 87

United States Constitution, Fourth Amendment....... 24, 25, 36, 44

United States Constitution, Fifth Amendment—.............................

....... ................. ............................................24, 25, 36, 39, 44, 71, 87

United States Constitution, Sixth Amendment.............................. 26

United States Constitution, Ninth Amendment........................24, 25

United States Constitution, Tenth Amendment ....... ..........24, 25

T extbooks

34 American Bar Association Journal, p. 15........... .................... 27

21 American Political Science Review, p. 47, Galloway, In

vestigative Function of Congress............................................... 83

1 Baylor Law Review, p. 212.................. 27

4 Blackstone’s Commentaries, pp. 325-327...................... 43

47 Columbia Law Review, p. 416................................. 27

33 Cornell Law Quarterly, p. 565—.................. 27

2 Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, 8th Ed., p. 886.............. 62

1 de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (N . Y. 1946), p. 196 51

3 Elliott’s Debates, pp. 445-449..................................................... 39

3 Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, p. 290, Laswell, Censor

ship ................................................................................................... 62

6 Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, p. 449, Laski, Freedom

of Association .................................... 51

26 Georgetown Law Journal, pp. 905, 918, Cousens, Investi

gations Under Legislative Authority......................................... 83

37 Georgetown Law Journal, p. 104,.................... 27

172 Harper’s, p. 171, Fredrich, Teacher’s Oaths.......................... 40

15 Harvard Law Review, p. 615 (Wigmore)............................... 37

PAGE

XI.

60 Harvard Law Review, p. 1193, Gellhorn, Report on a Re

port of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.... 27

61 Harvard Law Review, p. 592, O ’Brien, Loyalty Tests and

Guilt by Association.................. ............................................ ........ 27

Horne, Mirrour of Justices (Wash. 1903), Sec. 108, p. 245;

Subsec. 10, p. 246...................... ....................................................... 37

3 Howard, State Trials, p. 1315................................................... 38

43 Illinois Law Review, p. 253....................................... 27

46 Michigan Law Review, p. 521........................ 27

47 Michigan Law Review, p. 181, Nutting, Freedom of Si

lence : Constitutional Protection Against Governmental In

trusions in Political Affairs............................................... .......... 50

47 Michigan Law Review, p. 191..... 27

27 Nebraska Law Review, p. 608. 27

38 New Republic, p. 329, Frankfurter, Hands Off the Investi

gators ............................................................................................... 32

2 Rutgers Quarterly Law Review, p. 125..................................... 27

22 Southern California Law Review, p. 464.......... ..................... 27

23 St. John’s Law Review, pp. 1-67, 243-290, Reppy, The

Specter of Attainder in New York........................................... 41

26 Texas Law Review, p. 816...................... .................................... 27

14 University of Chicago Law Review, p. 256.............................. 27

15 University of Chicago Law Review, p. 544, Letter to Presi

dent from Yale Law School Faculty.................................... . 27

17 University of Cincinnati Law Review, p. 264..... .................. 27

74 University of Pennsylvania Law Review, p. 691, Potts,

Power of Legislative Bodies to Punish for Contempt....... 83

21 Virginia Law Review, pp. 763, 771, 787, R. Carter Pitt

man ....................................... 39

Wigmore on Evidence (3rd Ed.), par. 785........................ .............. 97

PAGE

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949.

No. 248

J o h n H o w a r d L a w s o n ,

vs.

U n i t e d S t a t e s o f A m e r i c a ,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

Petition for W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

The petitioner, John Howard Lawson, prays that a

W rit of Certiorari issue to review a judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia, rendered on June 13, 1949. On June 16,

1949, petitioner moved the Court of Appeals for an ex

tension of time to July 5, 1949, to file a petition for re

hearing. This motion was denied on June 23, 1949. On

motion of petitioner, he was granted an extension of 30

days to August 12, 1949, in which to file this petition in

this Court.

The petitioner was indicted under Rev. Stat., sec. 102,

as amended by C. 594, Act of June 22, 1938, 52 Stat.

— 2—

942, U. S. C., Title II, sec. 192 [J. A. 9] ;x was found

guilty by a jury verdict on the 19th day of April, 1948

[J. A. 43 ]; and thereafter, on the 21st day of May, 1948,

was sentenced to one year in jail and fined $1,000.00

[J. A. 44],

The petitioner perfected an appeal to the United States

Court o f Appeals, for the District o f Columbia. While

the appeal was pending in the Court of Appeals, the peti

tioner filed in this Court a petition for writ of certiorari

to the United States Court o f Appeals for the District

of Columbia (No. 334, Oct. Term, 1948). Said petition

was denied November 8, 1948. Thereafter, the Court

o f Appeals affirmed the trial court judgment and this

petition is directed to said judgment of affirmance. The

opinion below has not yet been officially reported.

Statement of Matter Involved.

Petitioner, John Howard Lawson, a dramatist and

screen writer (25 W ho’s Who, 1948, p. 1436) was sum

moned as a witness by the House Committee on Un-Amer

ican Activities (hereinafter referred to as “ the Commit

tee” ) to testify at the hearings described below [J. A.

188].

Between October 20 and October 30, 1947, members

of the Committee, purporting to act as a sub-committee,

held hearings, in Washington, D. C., on the subject, as

designated by them, “ Communist Infiltration of the Mo

tion Picture Industry” [J. A. 197].

The petitioner was not a voluntary witness. He ap

peared in response to subpoena served upon him at his

residence in California [J. A. 381].

Pursuant to paragraph 7 of Supreme Court Rule 38, there are

filed herewith copies of the joint appendix printed for use in the

United States Court of Appeals, for the District of Columbia. Ref

erences “ J. A .” are to pages of that printed record.

— 3—

At the outset of the hearings (according to petitioner’s

offer o f proof), counsel for petitioner presented to the

Committee a motion to quash the Committee’s subpoena

[rejected Exhibits 4 and 5 for identification, J. A. 394-

406], and were advised by the Chairman that the motion

should be renewed before petitioner was called to the

stand [J. A. 212],

Twenty-four witnesses preceded the petitioner [J. A.

200]. Some of the witnesses testified that petitioner was

a Communist, active as such in the motion picture indus

try, and attacked his character, integrity, and reputation

[J. A. 223-235], Prominent employers in the motion

picture industry, some of whom preceded petitioner on

the witness stand and others of whom followed him, were

directly asked by the Committee to discharge petitioner

Lawson, and others, to establish a blacklist and to use the

Motion Picture Producers Association of America as an

instrumentality for the effectuation of that blacklist [J.

A. 240-242; see also offers of proof referred to below,

pp. 513-545],

As petitioner offered to prove [J. A. 212], his counsel

renewed in writing their motion to the Committee to

quash the Committee’s subpoena [rejected Exhibit 6 for

identification, J, A. 406] on October 27, 1947, and at the

same time filed a written “ Application to Compel the

Return of Witnesses for the Purposes of Cross-Ex

amination” [rejected Exhibit No. 7 for identification,

J. A. 409],

By his renewed motion to quash, petitioner raised be

fore the Committee constitutional objections that the sub

ject matter of the investigation was outside the power of

the Committee as an agency of government, that the in

vestigation had the non-legislative object and aim of estab

4

lishing and maintaining “a system of blacklists and to tell

the motion picture industry whom to hire and whom to

fire, without regard to the ability or talent of the employee

involved and without regard to the choice of the particu

lar employer” [rejected Defendant’s Exhibit 6, J. A. 407]

and had the non-legislative object and aim “ to direct the

motion picture industry to make only those films which

the Committee feels reflect its ideas o f the American way

of life. This investigation is thus intended to deprive

not only the motion picture industry of its free choice to

select film subjects. More important, it will deprive the

American people of the privilege of selecting such films

as they may desire to see, solely upon the basis o f quality,

content and the public’s unhampered choice.” [Rejected

Exhibit 6, J. A. 407.]

By his written application for the allowance of cross-

examination of witnesses who had testified before the

Committee against him, petitioner asserted and offered to

prove to the Committee that these witnesses conspired

with the Committee “ to conduct this investigation for the

purpose of controlling and censoring the motion picture

industry and to deny persons engaged in the production

of motion pictures the fundamental guarantees of freedom

of speech, thus violating the Constitution o f the United

States and particularly the First Amendment thereof. An

examination of the record o f this investigation to date

discloses that out of a total of 200,000 words o f testimony

submitted into evidence, 185,000 consisted of hearsay.

When there is added to this shocking fact the accumu

lation of unsubstantiated accusation, slander and vilifica

tion, it becomes clear that the right o f cross-examination

is even more essential in this hearing than in a Congres

sional inquiry where minimum standards of decent proce

dure are observed.” [Rejected Exhibit 7, J. A. 410.]

— 5-

Both the motion and application were denied and peti

tioner Lawson then proceeded to testify.

At the outset o f the petitioner’s testimony before the

Committee, he asked leave, and was denied the oppor

tunity, to read a statement. The Chairman said, “ The

statement will not be read. I read the first line.” [J. A.

188.]

The petitioner protested this refusal and called atten

tion to the fact that executives of motion picture produc

ing companies had been accorded the privilege of reading

their statements.

Then the petitioner was asked and answered prelimi

nary, identifying questions. The Committee next asked

whether he was a member of the Screen Writers’ Guild.

The petitioner first objected to the question, urging that

the Committee had no power to ask it. He was inter

rupted numerous times in the course of his reply before

he was able to and did say that it was a matter of public

record that he was a member of the Guild. The Commit

tee interrogated him concerning his activities as a mem

ber and officer o f the Screen Writers’ Guild. The peti

tioner answered these questions, protesting them, assert

ing they violated his constitutional rights, and stating

that the information sought was a matter o f public record,

and that he was a former President of the Guild. Simi

lar questions concerning his screen writing were answered

in the same way.

The petitioner was then asked: “ Are you now or have

you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”

Again the petitioner replied by protesting, by saying that

the question violated his rights and exceeded the powers

o f the Committee. He asked that witnesses who had

testified concerning him be recalled for cross-examination

so that he could show they had perjured themselves. Mem

bers of the Committee and its counsel, Mr. Stripling,

repeatedly interrupted the petitioner’s reply. The testi

mony was brought to a close by the Chairman in the fol

lowing manner:

“ The Chairman: Then you refuse to answer that

question; is that correct?

Mr. Lawson: I have told you that I will offer my

beliefs, affiliations, and everything else to the Ameri

can public, and they will know where I stand.

The Chairman (pounding gavel): Excuse the

witness . . .

Mr. Lawson: As they do from what I have writ

ten.

The Chairman (pounding gavel) : Stand away

from the stand . . .

Mr. Lawson: I have written Americanism for

many years, which you are trying to destroy.

The Chairman: Officers, take this man away

from the stand . . .” [J. A. 196-197.]

Petitioner offered and the Court refused to allow proof

that when the Committee certified the alleged contempt

to Congress it did not submit any part o f Lawson’s state

ment which he had offered to the Committee during the

hearing, nor was it in any way presented to or considered

by Congress before or during the debate on the citation

for contempt. Similarly proof was offered and rejected

that the defendant’s various motions made before the

Committee to quash the subpoenas and for the cross-

examination of witnesses were not submitted to or con

sidered by Congress either before or during the debate

on the citation for contempt [J. A. 301-309].

7-

With this preliminary statement of the Committee hear

ings and the certification to the House o f Representatives

as developed at the trial, we now turn to a consideration

of the proceedings in the trial court.

Prior to the trial, petitioner filed a Motion to Dismiss

the Indictment, which was denied [J. A. 5, 6, 11].

A t the trial, the following was the only evidence offered

by the Government to establish the existence of a com

petent tribunal at the time that the petitioner testified at

the Committee hearings. The Committee had been created

and its personnel of eight members designated by virtue

of and pursuant to the Legislative Reorganization Act of

1946 [J. A. 174-175, Government’s Exhibits 1, 2 and 3,

J. A. 379-380], On the morning of October 27, 1947, the

session at which petitioner Lawson was called, three

members of the Committee, Congressman Thomas, Chair

man, of New Jersey, Congressman Vail of Illinois, and

Congressman McDowell of Pennsylvania, were present.

The Chairman opened the hearing on that day by saying:

“ The record will show that a sub-committee is present

consisting of Mr. Vail, Mr. McDowell and Mr. Thomas.”

[J. A. 183.] Over petitioner’s objections, the Chairman

of the Committee testified that as a matter of law he, as

chairman of the Committee, has authority to designate

whether a full committee or a sub-committee shall sit, and

in the latter event, to appoint the sub-committee; that he

had appointed a sub-committee at the outset o f the hearing

on October 27, 1947, by making the statement in the

record to the effect that a sub-committee consisting of

himself, Mr. Vail and Mr. McDowell was present [J. A.

183-186, 197-198],

The petitioner served subpoenas duces tecum on the

Committee calling, among other things, for the records

of the Committee relating to the appointment of or any

authority given to appoint a sub-committee to sit in the

hearings in Washington in October of 1947. The Gov

ernment’s motions to quash the subpoenas in their entirety

were granted, despite petitioner’s contention, among other

things, that these records would show that the Committee

was authorized to conduct the October, 1947, hearings

only by and through the full committee [J. A. 318-28,

343-346],

Upon submission o f the case to the jury, the judge

instructed it that if the Chairman designated a sub

committee on October 27, 1947, the body so designated

was a validly constituted sub-committee of the Committee,

thereby deciding as a matter of law and without regard

to the facts that the Chairman had authority to designate

a sub-committee [J. A. 355], The Court refused to give

petitioner’s proposed instructions, either that a quorum

of the full Committee was necessary in order to consti

tute a legally competent tribunal, or that a sub-committee

could act only if it had been designated by the full Com

mittee or pursuant to its authorization [Petitioner’s Pro

posed Instructions 37 to 48, inclusive, J. A. 372-375],

The trial judge held immaterial and refused to permit

evidence in support o f petitioner’s contentions that the

Committee used its powers as an agency of government

to establish a blacklist against petitioner and others, to

censor motion pictures and to conduct an unlimited in

vestigation into the content of speech and ideas, designed

to impede and resulting in the impediment of free speech

and association. In support o f his contentions the peti

tioner made a number of offers o f proof, after Govern

ment objections to appropriate questions had been sus

tained. All of said offers were rejected. With respect

— 9—

to blacklisting the petitioner offered to prove the follow

ing:

(a ) A sub-committee of the Committee, with its chief

investigator, Stripling, went to Los Angeles in the Spring

of 1947 and there examined a number of motion picture

producers, and called upon them to discharge and to sus

pend certain writers and directors whom the Committee

considered to be Communists, among whom was the peti

tioner, Lawson.

(b ) The producers at first rejected the demand of the

sub-committee that certain writers be discharged and

blacklisted and said that such conduct was unlawful [J. A.

545].

(c ) In the Summer of 1947, the Committee sent two

of its investigators, Leckie and Smith, to Hollywood, there

to call upon the producers, including Louis B. Mayer,

executive in charge o f production at Metro-Goldwyn-

Mayer Studios, and Dore Schary, executive in charge of

production at RKO Radio Pictures. These investigators

urged the producers “ to clean out their houses of certain

writers, including petitioner, else there would be trouble

in the industry from the House Committee.” [J. A. 312-

316.]

(d ) During the hearings at which petitioner testified

all o f the members of the Committee and the Committee’s

chief investigator urged the Motion Picture Producers

Association and individual producers to establish a black

list o f persons, including the petitioner, whose alleged

views and affiliations were disapproved by the Committee.2

2For example one Committee member stated that the industry

should “ concern itself with cleaning house in its own industry . . .

I don’t think you can improve the industry to any greater degree

and in any better direction than through the elimination of the

writers and the actors to whom definite Communistic leanings can

— 10—

(e ) In November, 1947, following the close of the

Washington hearing, the industry capitulated to the

Committee’s demand for a blacklist; the petitioner and

nine other writers and directors named by the Committee

were blacklisted by the industry. Unexpired contracts

o f other so-called “ unfriendly” witnesses were abruptly

terminated and further employment in any branch o f the

industry was denied to all o f them, including petitioner

[J. A. 263 and 167 F. (2d) 241, 254, note 8],

( f ) Thereafter, the Committee in its request for con

tempt citations claimed “ the credit for these discharges

and this blacklist.” * I * 3

be traced.” The Committee’s counsel joined in the demand that

“ Communistic influences . . . and I say Communist influences;

I am not saying Communists” ; be eliminated from the industry by

cutting “these people off the payroll” [J. A. 517], One of the

members of the Committee stated the function of the hearing in this

way: “ . . . of course, we have the problem of eliminating the

Communist element from not only the Hollywood scene but also

other scenes in America, and we have to have the full support and

cooperation of the executives for each of those divisions” [J. A.

518]. At another point, the Chairman of the Committee stated that

four of the unfriendly witnesses (the term used by the Committee

in referring to petitioners Lawson, Dalton Trumbo, and other w r i

ters) before the Committee have been shown to have “ extensive

Communist and Communist-front records. Yet, this kind of people

are writing scripts in the moving picture industry” [J. A. 521].

He then went on to state that that was one of the reasons for the

investigation, and that the investigation will be beneficial to the

American people and to the industry “because you are the people

. . . you persons high up in the industry can do more to clean

your own house than can anybody else, but you must have the will

power, and we hope that by spotlighting these Communists you

will acquire that will” [J. A. 522],

3[See Transcript. J. A. 263-4]; Congressional Record, Monday

November 24, 1947, at page 10890, et seq.:

“ Congressman Mundt: . . . Then to go on I want to

congratulate the Fox Moving Picture Co., the Twentieth Cen

tury-Fox, I believe it is called, which passed a resolution the

other day, and I want to read it to you. ‘Resolved, that the

officers of this corporation be and they are hereby directed, to

the extent that the same is lawful, to dispense with the services

— 11—

With respect to censorship the petitioner offered and

the Court refused to permit the following p roof:

(a ) The Committee utilized its hearings to stop the

production o f motion pictures, the over-all approach of

which did not meet the approval o f the Committee mem

bers. Included in this category were pictures like “ Mis

sion to Moscow,” based upon the book of the same title

written by former Ambassador Davies [J. A.. 489-490]

and pictures which depicted Negroes in a favorable light.

One of the reasons why the petitioner was called as a wit

ness by the Committee was that he wrote pictures which

did so treat Negro characters [J. A. 325-326],

(b ) The Committee utilized its hearings and the ques

tions put to petitioner to compel the motion picture in

dustry to make only the kind of pictures the Committee

believed should be seen by the American public. Thus

for example the chairman asked one witness whether he

believed that these public hearings would “ aid the industry

in giving it the will to make these [anti-Communist]

pictures,” and the witness replied: “ It is my opinion that

they will.” [J. A. 488.]

(c ) The Committee utilized its hearings to establish

standards for the content o f motion pictures. It called

on the motion picture industry to eliminate from pictures

of any employee who is an acknowledged Communist or of any

employee who refuses to answer a question with respect thereto

by any committee of the Congress of the United States and is

cited for contempt by reason thereof.’

“ I congratulate Twentieth Century-Fox on that progressive

and patriotic step. I think it is time, and I think it is just a

little late, that Hollywood take that action but I congratulate

it now because it is highly important that Communists be

purged out of the moving picture industry. This desirable

objective has been materially aided by the recent hearings in

Washington as the general public is becoming rapidly alert to

the problem.”

- 12-

anything which the Committee considered Communistic

or un-American or subversive propaganda. The Com

mittee chairman and other Congressmen, members of the

Committee, recognizing that “ it would be very foolish for

a Communist or a Communist sympathizer to attempt to

write a script advocating the overthrow of the govern

ment by force or violence,” found un-American propa

ganda in “ innuendos and double meanings, and things

like that” [J. A. 504], in “ slanted lines” [J. A. 505], in

“ subversion” inserted in the motion pictures “ under the

proper circumstances, by a look, by an inflection, by a

change in the voice.” [J. A. 505.] Among the sub

versive manifestations in motion pictures specified by the

Committee were reference to some crooked members of

Congress, to dishonest bankers or Senators, to a minister

shown as the tool of his richest parishioner, and to pre

sentation of bankers as unsympathetic men [J. A. 506-

510].

With respect to his contentions that the Committee used

its hearings and powers to conduct an unlimited investiga

tion into the content of speech and ideas designed to

impede and resulting in the impediment of free speech and

association, the petitioner offered and the Court refused to

permit the following p roo f:

(a ) During its entire existence the Committee has con

sidered its authority sufficiently broad in scope to permit

investigation and examination o f every kind of organiza

tion, whether fraternal, social, political, economic, or

otherwise, and of every kind of propaganda, including

limitless and unrestricted inquiry into any and all ideas,

opinions, beliefs, and associations, of any and all indivi

duals and organizations. In determining whether the in

vestigation into the Hollywood motion picture industry

— -13—

should be made, hearings held, and questions put, the Com

mittee interpreted and applied the resolution and rules

under which it acted in accordance with said construction

of its powers [J. A. 420; rejected Exhibit 9].

(b ) The Committee conducted its Hollywood investiga

tion, determined the pertinency o f questions, and other

wise proceeded upon the basis that its authority was

established by its own definition and application of the

terms “ un-American propaganda activity” and “ subversive

and un-American propaganda that . . . attacked the

principles o f the form of government as guaranteed by

our Constitution.” The Committee’s concept of what is

un-American and subversive runs the whole gamut of

what are often denominated progressive ideas in Ameri

can life, from support of the New Deal to opposition to

the Committee on Un-American Activities; from opposi

tion to monoply to defense of sit-down strikes; from ad

vocacy of the Geyer Anti-Poll Tax Bill to opposition to

the method of choosing members of the legislature in

New Jersey; from supporting, during the war, friendship

with “ our allies, the Russian people” to the belief that the

government of Franco-Spain is not democratic; from a

belief in absolute racial and social equality to signing a

resolution in opposition to outlawing of the Communist

Party; from criticism of Congress to criticism of Chiang-

Kai-Shek [rejected Exhibit 9 for identification; J. A.

420-479; 249-253].

(c ) Upon the basis o f the aforesaid premises as to

what constitutes un-American, subversive activity, the

Committee has built up files containing names of more

than a million individuals and more than a thousand or

ganizations accused of being subversive. It has asserted

that it functions as “ the Grand Jury of America,” as a

— 14—

“ vigilante committee,” and that it is a “ democratic” sub

stitute for the gestapo [rejected Exhibit 9 for Ident.,

J. A. 420-479],

(d ) Representative Herman E. Eberharter as a mem

ber of Congress and a former member of the Committee

thoroughly familiar with its activities would state on the

basis of his expert knowledge that the Committee had not

been engaged in obtaining information for any matter

within the scope of any lawful legislative power but that

it had engaged in attacking ideas with which it disagreed

and which could not be considered subversive by any

reasonable standard and that it was a conscious political

instrumentality directed against the new deal [J. A. 307-

309],

(e ) The Hollywood hearings directly impeded the ex

ercise of free speech and association. The effect o f these

hearings was recognized by a witness called by the Com

mittee, who said he could not answer a question as to

whether Communism was increasing or decreasing in

Hollywood, because “ It is very difficult to say right now,

within these last few months, because it has become un

popular and a little risky to say too much. You notice

the difference. People who were quite eager to express

their thoughts before begin to clam up more than they

used to.” The effect o f the Committee’s action was also

pointed out by Mr. Eric Johnston, of the Motion Picture

Producers’ Association, who stated that while Senator

Robert Taft need not worry about being called a Com

munist, not every American was in that position. Charges

of this kind can take away everything that a man has—

“ his livelihood, his reputation, and his personal dignity.”

[Exhibit 10 for Ident., J. A. 542.]

The petitioner contended that the procedures of the

Committee were such as to deny him due process of law.

- 15-

The trial court held that any evidence on this point was

immaterial. The petitioner then offered to prove and the

Court rejected proof that during the Hollywood hearings

and at all other times the Committee while using its pow

ers to accomplish the unconstitutional objectives set forth

above including the destruction o f individuals by black

listing, character assassination and otherwise has con

sistently denied the basic rights of confrontation and cross-

examination o f witnesses, effective aid of counsel, the

right to produce evidence, and that the Committee at all

times has assumed “guilt by association” and unqualifiedly

accepted hearsay upon hearsay and unsubstantiated gos

sip [rejected Exhibits 9 and 10 for Ident., supra].

The Government’s evidence on pertinence was tried be

fore the judge alone and not before the jury, over peti

tioner’s objection, which was overruled [J. A. 220],

The only evidence to support the claim that the question

put to petitioner was pertinent came from Congressman

Thomas, who read from the Committee Transcript por

tions o f the testimony given by three witnesses before the

Committee during the investigation [J. A. 219-228].

These three witnesses, relied on to establish pertinence,

were witnesses as to whom petitioner had in his “ Appli

cation for Cross-Examination” [rejected Exhibit No. 7]

— sought the right of cross-examination. Meaningful ef

forts to cross-examine Mr. Thomas on the issue o f perti

nence were disallowed, the Court saying:

“ The Court: Suppose they did not have any testi

mony. Suppose they decided to investigate the infil

tration of Communists in the motion picture industry

and they called Mr. Lawson as the first witness and

asked him whether or not he was a Communist.

Mr. Margolis: I take the position that they can’t

— 16-

call 140,000,000 Americans to the stand and ask

them if they are members o f the Communist Party.

The Court: I think I have had enough. I will

rule. I will rule that the question is pertinent.” [J. A.

242.]

The petitioner claimed that even by the Government’s

own test the inquiry into the motion picture industry was

not pertinent to the subject-matter which the Committee

by the terms of Section 121 of the Legislative Reorganiza

tion Act of 1946 was authorized to investigate and par

ticularly that the writers’ lack of control over the content

of motion pictures rendered the questions put to petitioner

not pertinent. In this connection the petitioner offered

proof which the Court refused to permit that:

(a ) There is nothing in American motion pictures gen

erally or in the motion pictures written by petitioner spe

cifically which by any reasonable standard or definition

could be considered subversive or which would otherwise

justify inquiry by the Committee [J. A. 270-280],4 “ A c

tion on the North Atlantic,” as one example of the pictures

written by petitioner was classified by the organization as

desirable for family or mature audiences and received a

4In addition to producers of long standing and high repute, heads

of great studios including the largest studio in the world, prominent

writers, story analysts, and drama critics, Richard Griffith, a re

viewer, critic and executive director of the National Board of

Review, was offered as a witness on this point. Mr. Griffith has

reviewed many thousands of films as a critic and on behalf of his

organization, whose purpose it is to organize audience support for

meritorious pictures. Its seal is placed on approved films. The

organization has two to three hundred community councils con

sisting of representatives of civic, religious, educational and cultural

organizations. The governing body is composed of delegates from

such organizations as the Boy Scouts of America, the American

Bar Association, the Association of American Colleges, the Na

tional Association of Better Business Bureaus, the Daughters of

the American Revolution, the Y.M.C.A., etc. [J. A. 266-70],

— 17—

star as a picture especially worth seeing and as one which

had done a great service for the American Merchant Ma

rine [J. A. 272].5 6

(b ) As a matter of undeviating practice in the motion

picture industry it is impossible for any screen writer to

put anything into a motion picture to which the executive

producers object; the content of motion pictures is con

trolled exclusively by producers; every word, scene, situ

ation, character, set, costume, as well as the narrative line

and the social, political and religious significance of the

story are carefully studied, checked, edited and filtered by

executive producers and persons acting directly under

their supervision; and consequently the content of every

motion picture is determined by the producer; all of these

facts were matters o f common knowledge when petitioner

Lawson was subpoenaed by the House Committee.

Petitioner further claimed that the question was not

pertinent and was an invasion of his constitutional rights

because the Committee did not ask the question in order

to get information which it believed it needed. In this

connection the Court rejected petitioner’s offer of proof

that every Congressman before whom Lawson testified on

October 27, 1947, and a majority of the members o f the

whole Committee, and the Committee itself announced in

their official statements that they were convinced before

Lawson was put on the stand that he was a Communist

and that nothing he could have said would change their

minds, and that his disavowals would not be believed [J.

A. 262-266; rejected Exhibit 11 for Ident., J. A. 546].

5An offer to exhibit each of the motion pictures which Lawson

had written to the Court and to the jury was also rejected by the

Court.

In addition to rejecting the offers of proof hereinabove

referred to, the Court refused to permit or sharply cur

tailed cross-examination of the principal prosecution wit

ness, Congressman J. Parnell Thomas, on the issues re

ferred to above. Nor was the petitioner allowed to cross-

examine the Congressman on the issue of his bias and

prejudice as a prosecution witness against the petitioner

[J. A. 202-203; J. A. 207; J. A. 214-244], On the Gov

ernment’s motions the Court quashed subpoenas duces

tecum directed to the Committee calling for its records

relating to the aforesaid issues [J. A. 318-328; J. A. 343-

346],

At the close of Government’s case, petitioner made a

motion for acquittal which was denied [J. A. 300.]

During the course o f the argument of defense counsel

to the jury, the Court interrupted the argument and stated

to the jury that “ there is nothing in the record to indicate

that he was trying to answer the question. You can refer

to the record” [J. A. 348-349], and charged the jury that

(a ) a non-responsive reply, or (b ) a reply that seems un

clear to the jury was per se conclusive proof o f a refusal

to answer and that such reply required the jury to return

a verdict of guilty as against petitioner [J. A. 358, 359].

All of the petitioner’s prayers and requested instruc

tions to the jury were denied by the Court [J. A. 360].

Included in the instructions denied were some to the

effect that a failure to answer or a non-responsive answer

was not necessarily a refusal to answer [J. A. 377-378].

Prior to and at the outset of the trial, motions to trans

fer the cause to another district for trial on the ground

that juries in the District of Columbia contain many Gov

ernment employees and their relatives and that it was

impossible to have a fair trial in this particular cause

wherein the principal prosecution agency was the House

Committee on Un-American Activities, which Committee

exercised meaningful control and authority over the jobs

and the political views o f the Government employees and

their near relatives who might be called to sit upon such

a jury; the motion to transfer to another district for trial

was denied [J. A. 13-25, 57], Prior to the final selection

of the jury, petitioner moved to excuse for cause from

the trial jury selected all those jurors who were govern

ment employees and government pensioners and their near

relatives, and this motion was denied [J. A. 166]; as

finally constituted, the trial jury in the case was composed

o f five persons employed by the Government, one juror

who was receiving a pension from the Government, and

one juror whose mother was receiving such a pension

[J. A. 142, 143, 167]; the petitioner’s request for addi

tional peremptory challenges so that he might attempt to

get non-government employees into the jury box was like

wise denied [J. A. 166],

Immediately prior to the trial a challenge to the array

and a motion to dismiss the jury panel was made on the

ground that it was selected in fi manner neither designed

nor calculated to obtain a representative cross-section of

the community. In support thereof, petitioner proved that

one o f the qualifications for jury service in the District of

Columbia is an affirmative response to the question “ Have

you any views opposed to the American form of govern

ment?” [J. A. 87, 92.] In addition, the jury commis

sioner examined handwriting on questionnaires returned

by talesmen for the alleged purpose of determining the in

telligence of the prospective jurors; persons of low income

groups with “ poor handwriting” were disqualified on the

— 19—

-20—

alleged ground that such poor handwriting- disclosed a

lack of intelligence in members of such groups. How

ever, those in higher income brackets who likewise had

“ poor handwriting” were accepted for jury service [J. A.

97], This motion also was denied [J. A. 29-32, 57-98].

Following the jury’s verdict of guilty, petitioner made

a motion for a new trial and in arrest o f judgment, both

of which motions were denied [J. A. 8].

Statement as to Jurisdiction.

The conviction was affirmed by judgment of Court of

Appeals on June 13, 1949. The jurisdiction of this Court

is based on the Act o f June 25, 1948, c. 646 (62 Stats.

869), U. S. C., Title 28, sec. 1254, subsec. 1, which pro

vides that a writ of certiorari may issue to the Court o f

Appeals of the District o f Columbia “after rendition of

judgment or decree.”

Statutes Involved.

(1 ) Rev. Stats., Par. 102, as amended by Chap. 594,

Act of June 22, 1938, 52 Stat. 942; U. S. C. A., Title 2,

Par. 192:

“ Every person who having been summoned as a

witness by the authority of either house o f Congress

to give testimony or to produce papers upon any mat

ter under inquiry before either house or any joint

committee established by a joint or concurrent reso

lution of the two houses o f Congress, or any com

mittee of either house of Congress, wilfully makes

default, or who, having appeared, refuses to answer

any questions pertinent to the question under inquiry,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, punishable

by a fine of not more than $1000.00 nor less than

$100.00 and imprisonment in a common jail for not

less than one month nor more than twelve months.”

-21

(2 ) Sec. 121(b), Legislative Reorganization Act

1946, P. L. 601, Chap. 753, 79 Cong., 2d Sess., 60 Stat.

828, amends Rule X I ( 1 ) (2 ) o f Rules o f the House of

Representatives to provide:

‘■'The Committee on Un-American Activities, as a

whole or by subcommittee, is authorized to make from

time to time investigations o f :

“ ( i ) The extent, character, and objects o f Un-

American propaganda activities in the United States,

“ (ii) the diffusion within the United States of sub

versive and Un-American propaganda that is insti

gated from foreign countries or o f a domestic origin

and attacks the principle of the form of government

as guaranteed by our Constitution, and

“ (iii) all other questions in relation thereto that

would aid Congress in any necessary remedial legisla

tion.

“ The Committee on Un-American Activities shall

report to the House (or to the clerk of the House if

the House is not in session) the results of any such

investigation, together with such recommendations as

it deems advisable.

“ For the purpose of any such investigation, the

Committee on Un-American Activities, or any sub

committee thereof is authorized to sit and act at such

times and places within the United States, whether or

not the House is sitting, has recessed, or has ad

journed, to hold such hearings, to require the attend

ance of such witnesses and the production of such

books, papers, and documents, and to take such testi

mony as it deems necessary. Subpoenas may be issued

under the signature of the chairman of the committee

or any subcommittee, or by any member designated by

any such chairman, and may be served by any person

designated by any such chairman or member.”

(3 ) Title XI, Section 1417 o f the Code for the District

o f Columbia, relating to qualifications for jurors, pro

vides :

“ No person shall be competent to act as a juror

unless he be a citizen o f the United States, a resident

of the District o f Columbia, over twenty-one and

under sixty-five years of age, able to read and write

and to understand the English language, and a good

and lawful person, who has never been convicted of a

felony or a misdemeanor involving moral turpitude.”

(4 ) 49 Stats, at Large 682, Act of Congress of August

22, 1935, Chap. 605, provides:

“ All executive and judicial officers o f the Govern

ment of the United States and of the District of

Columbia, all officers and enlisted men of the Army,

Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard of the United

States in active service, those connected with the po

lice and fire departments of the United States and o f

the District of Columbia, counselors and attorneys of

law in actual practice, ministers of the gospel and

clergymen of every denomination, practicing physi

cians and surgeons, keepers o f hospitals, asylums,

almshouses, or other charitable institutions created by

or under the laws relating to the District o f Colum

bia, captains and masters and other persons employed

on vessels navigating the waters of the District of

Columbia shall be exempt from jury duty, and their

names shall not be placed on the jury lists.

“ All other persons, otherwise qualified according to

law whether employed in the service of the Govern

ment of the United States or of the District o f Co

lumbia, all officers and enlisted men of the Na

tional Guard of the District of Columbia, both

active and retired, all officers and enlisted men of

•23—

the Military, Naval, Marine, and Coast Guard

Reserve Corps of the United States, all notaries

public, all postmasters and those who are the re

cipients or beneficiaries of a pension or other gratu

ity from the Federal or District Government or who

have contracts with the United States or the District

o f Columbia, shall be qualified to serve as jurors in

the District o f Columbia and shall not be exempt

from such service: Provided, That employees of the

Government o f the United States or of the District

of Columbia in active service who are called upon to

sit on juries shall not be paid for such jury service

but their salary shall not be diminished during their

term of service by virtue of such service, nor shall

such period of service be deducted from any leave of

absence authorized by law.”

Questions Presented.

I.

As a matter of law in a contempt proceeding such as

this, is there a conclusive presumption which attends every

Congressional investigation that such investigation is

lawful, that the Committee had jurisdiction of the subject

matter under inquiry, that the Committee acted within

the lawful bounds of its power, and that it denied no Con

stitutional rights or privileges to the witnesses, as was all

conclusively presumed by the trial and appellate courts

below in the face of petitioner’s attempt to prove the con

trary in each respect?

II.

May a private individual, called as a witness by the

Committee in an investigation into a private industry

wherein he is employed, be compelled to disclose his politi

cal opinions and associations, particularly where the Com

— 24—

mittee’s proceedings are used to impose loss of employment

and other penalties upon him; or does such compulsion

violate Article One, Section Nine, and the First, Fourth,

Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Amendments to the Constitution?

III.

Does an investigation in which the Committee uses its

powers to censor the content of motion pictures lay outside

the lawful bounds of the Committee’s power; and may a

witness before the Committee be compelled to answer a

question which is put as part of the process o f censorship,

or would such compulsion violate the First Amendment?

IV.

Does an investigation in which the Committee uses its

powers to secure the discharge and blacklisting o f per

sons whose alleg’ed ideas and affiliations are deemed “ un-

American” and “ subversive” by the Committee lay out

side the lawful bounds of the Committee’s power; and may

a witness before the Committee be compelled to answer a

question which is put as part of the process to secure his

discharge and blacklisting, or would such compulsion be a

usurpation of power and a violation of the due process

clause of the Fifth Amendment?

V.

When a witness before the Committee is being threat

ened with discharge and blacklisting- in and by the Com

mittee’s use of its power, is it a denial o f due process

under the Fifth Amendment to refuse to allow the wit

ness the effective aid of counsel, the right to make a state

ment and offer evidence in his own behalf, the right to

cross-examine witnesses who attack him, and other essen

tials of a fair hearing?

Is the statute establishing- the House Committee on

Un-American Activities, on its face and as construed

and applied generally and in the present case by the

Committee, unconstitutional as in contravention o f the

First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Amendments and

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution?

VII.f*

Did the trial court, by its instructions, refusals to

admit evidence and quashing of subpoenas duces tecum,

commit prejudicial error in taking away from the jury

the questions of fact relating to the issue o f the existence

of a lawfully constituted tribunal and, in effect, determin

ing that issue as a matter of law?

VIII.

Did the trial court commit prejudicial error in instruct

ing the jury that a failure to give a responsive answer or

the giving of a reply which is unclear to the jury is per se

conclusive proof o f a refusal to answer, and in comment

ing to the jury that the petitioner was not trying to answer

the question?

IX.

Did the trial court commit prejudicial error in sharply

curtailing cross-examination of the only prosecution wit

ness as to some issues and refusing to permit cross-

examination at all as to others?

X.

Did the trial court commit prejudicial error by refus

ing to admit evidence that the Committee, in presenting

to the House of Representatives the citation for contempt,

did not inform it as to all o f the material parts thereof?

V L

XI.

Did the utilization, over the objection of petitioner, of

government employees as jurors in this particular case,

involving the House Committee on Un-American Activi

ties as the governmental agency directly interested in the

prosecution and based upon the charge that petitioner re

fused to disclose whether or not he was a member of the

Communist Party constitutes prejudicial error?

XII.

May the Jury Commission of the District of Columbia

validly impose as a requirement for jury service a nega

tive answer to the question, “ Do you have any views

opposed to the American form of government?” ; and

did the trial court commit prejudicial error in denying

petitioner’s challenge and motion to dismiss the jury panel

based on the aforesaid requirement?

X III.

Was petitioner’s right to an impartial jury drawn from

a cross-section of the community abbrogated by the estab

lishment of qualifications for jury service other than those

required by statute and which limited the representative

character of the jury; and did the denial of the challenge

and motion to dismiss the jury panel based upon the

aforesaid grounds constitute prejudicial error?

XIV .

Was petitioner denied a fair trial in violation of the

Sixth Amendment by reason of the matters set forth in

questions V II to X III, inclusive.

— 26—

Reasons for Granting the Writ.

The court below decided important questions of federal

law which have not been, but should be, settled by this

Court. It decided federal questions in a way in conflict

with applicable decisions of this Court. The court below

has so far departed from accepted and usual course of

judicial proceedings, and so far sanctioned such a de

parture by the trial court herein as to call for an exercise

of this Court’s power of supervision.

This is the first of the ten now famous “ Hollywood

writers” contempt cases. The widely publicized hearings

out of which these cases arose were held in Washington,

D. C., from October 20-30, 1947, by the House Committee

on Un-American Activities. Since then a great debate,

international in scope, has arisen over the constitutional

questions presented by this case.* These comments have

been numerous and highly important.

*See 46 Mich. L. Rev. 521; 47 Mich. L. Rev. 191; 33 Cornell

L. Q. 565; 17 Univ. of Cincinnati L. Rev. 264; 14 Univ. of Chi

cago L. Rev. 256; 61 Harvard L. Rev. 592 ( “ Loyalty Tests and

Guilt by Association,” John Lord O ’Brien) ; 43 111. L. Rev. 253; 60

Harvard L. Rev. 1193 ( “ Report on a Report o f the House Com

mittee on Un-American Activities” ), Walter Gellhorn; 47 Col.

L. Rev. 416; 37 Georgetown L. Journal 104; 1 Baylor L. Rev. 212;

2 Rutgers Q. Law Rev. 125; 27 Neb. L. Rev. 608 ; 26 Texas L.

Rev. 816; 15 Univ. of Chicago L. Rev. 544 ( “ Letter to President

from Yale Law School Faculty” ) ; 34 A. B. A. J. 15; 22 So. Cal.

L. Rev, 464.

-28—

1. The instant case and its companion, Tnmibo v.

United States, are the first cases to reach this Court which

squarely present the issue whether the House Committee

on Un-American Activities has the power under our

Constitution to summon before it individual Americans

and require them to make compulsory disclosure to it of

their political affiliations. The determination of this issue

is essential, for not only has this agency of government

claimed and exercised such power of compulsory disclo

sure, but the precedent set by the agency of government

has sired a host of similar claims to like power through

out the length and breadth of the nation. In the wake

of this assertion of official power, governmental agencies

of every kind and character, local, state and federal, are

presently asserting power, through various devices of

compulsory disclosure, to require persons to render unto

such bodies an accounting not only of their affiliation or

non-affiliation with a given political party, but an account

ing as well with respect to the newspapers, books and

magazines they read, the causes, beliefs and ideas they

embrace, the religion to which they adhere, and the

associations into which they have entered whether transient

or enduring.*

Standing alone this question presents constitutional

problems of great importance the answer to which will

have a great impact upon American life. Moreover the

problem is so posed in this case that it presents a host of

additional constitutional issues.

The court below recognized that the compulsory dis

closure demanded by this agency of government invaded

*The consitutionality o f such a broad assertion of power is pres

ently before this court for review in the case of Parker v. County

of Los Angeles, October Term 1949, No. 49.

-29—