Hoots v. Pennsylvania Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 15, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hoots v. Pennsylvania Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1981. 86de955b-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c43b882-32e2-43c4-a8f9-bf9e2e42d2f7/hoots-v-pennsylvania-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

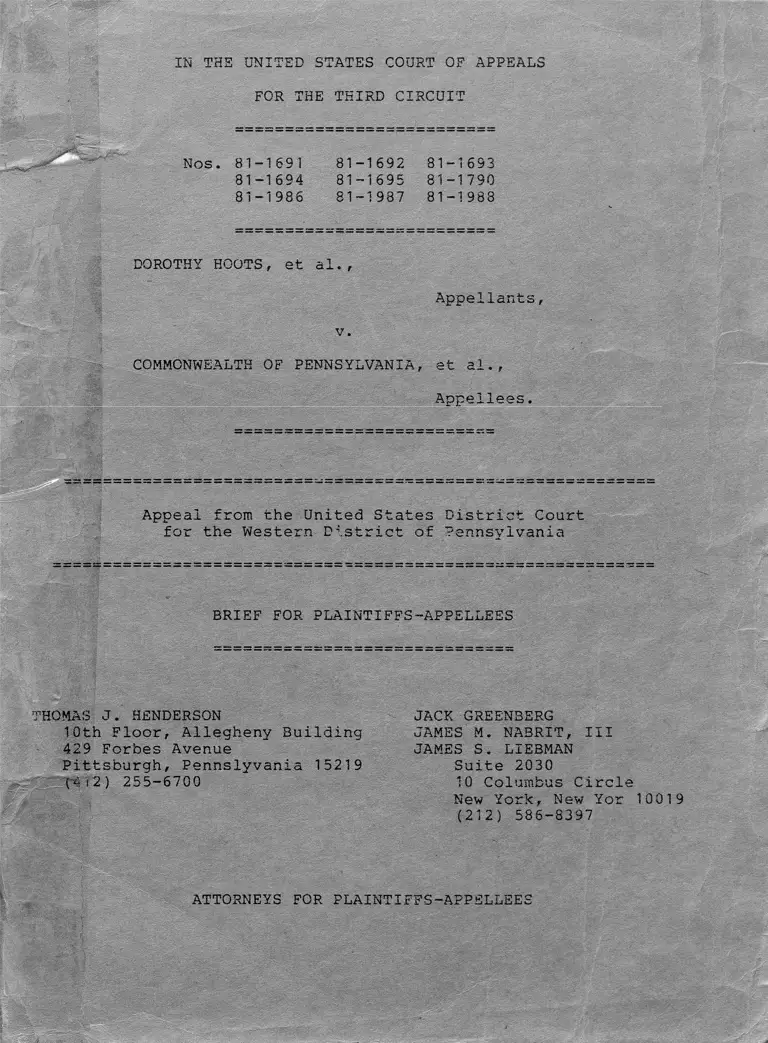

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

Nos. 81-1691 81-1692 81-1693

81-1694 81-1695 81-1790

81-1986 81-1987 81-1988

DOROTHY HOOTS, et al..

Appellants,

v.

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al..

Appellees.

THOMAS J. HENDERSON

10th Floor, Allegheny Building

429 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, Pennslyvania 15219

(4i2) 255-6700

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JAMES S. LIEBMAN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New Yor 10019

(212) 586-8397

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cross-Reference Index of Arguments ................. iv

Table of Authorities ............................... xi

List of Tables .......................... xviii

Statement of the Issues ........ 1

Summary of the Argument ............................ 1

Statement of the Case ................. 3

A. Prior Proceedings ................... 3

B. Facts ............................... 9

1. The Reorganization Acts and

administrative guidelines ...... 9' *■ s

2. The creation of GBASD and the

four former districts ......... 13

Argument ............................................ 20

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DETERMINATION THAT

PENNSYLVANIA AUTHORITIES INTENTIONALLY

SEGREGATED SCHOOL DISTRICTS AMPLY SUP

PORTS ITS CONSTITUTIONAL-VIOLATION FIND

ING, AND IS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS ....... 20

A. Relying on Proper Fourteenth Amend

ment Standards, the District Court

Has Repeatedly Found that Pennsyl

vania School Officials Intentionally

Segregated GBASD and Neighboring

School Districts on the Basis

of Race ............................. 22

1. The district court applied

the correct Fourteenth Amend

ment standard in its 1973

violation decision ............. 22

2. Between 1973 and 1981, following

additional argument and hearings,

the district court repeatedly

reaffirmed its legally un

assailable violation finding .... 31

Page

- i -

Page

B. The Trial Court's Findings of Inten

tional Racial Segregation Are Not

Clearly Erroneous ............... 34

1. The "direct" evidence of

intent .......................... 36

2. The "circumstantial" evidence of

intent .......................... 40

C. The District Court's De Jure-Dis-

crimination Finding Is Strongly

Supported by the State Board's

Peculiar Construction of Its "Race"

Guideline ........... ............... 42

II. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS BROAD

REMEDIAL DISCRETION IN CONSOLIDATING FIVE

SCHOOL DISTRICTS, WHOSE BOUNDARIES WERE ALL

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DRAWN, INTO ONE DESEGRE

GATED DISTRICT...... .................... 50

A. The District Court Applied Proper

Standards in Determining that the Vio

lation Was Interdistrict in Nature

and Involved School Districts on

Either Side of Unconstitutionally

Formulated Boundaries .............. 51

B. The District Court Applied Proper

Standards and Correctly Determined,

Based on Extensive Evidence, that

the Scope of the Violation Encom

passed GBASD and the Four Former

Districts ........................... 56

1. The district court applied

proper standards in determining

that the violation affected all

central eastern Allgheny

County .......................... 56

2. The district court's findings

that each of the former school districts was directly impli

cated in the State's line

drawing violation are supported

by extensive record evidence .... 62

- ii -

Page

a. Churchill ......................... 63

b. Edgewood .......................... 66

c- Swissvale ..................... 68

d. Turtle Creek ........... 69

3. The district court applied proper legal

standards in concluding that the vio

lation was, and that the remedy could

be, "system-wide" .................. 71

C. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Broad

Remedial Discretion in Concluding That

Five of the School Districts that Could

Properly Be Included in a Remedy Should

be Included in a Single-District-Consolida

tion P l a n ......... 74

III. THE DISTRICT COURT AFFORDED THE FORMER DISTRICTS

A LEGALLY SUFFICIENT OPPORTUNTY TO PARTICIPATE

AND BE HARD ON ALL RELEVANT ISSUES ............. 78

Conclusion ................ 65

Certification........................................... xix

- iii -

CROSS-REFERENCE INDEX OF ARGUMENTS

Appellants 1 Contentions- y

Page

•kit /

Section Page

Response

Edqewood, Turtle Creek

I. THE DISTRICT COURT COMMITTED CONSTI

TUTIONAL ERROR WHEN IT HELD THAT

DEFENDANTS HAD VIOLATED THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT EVEN THOUGH DEFEN

DANTS' ACTIONS WERE UNDERTAKEN WITH

NO SEGREGATIVE INTENT OR PURPOSEFUL

DISRIMINATION 15 I 20

A. The District Court Erred in

Holding that the Fourteenth

Amendment Was Violated in

the Absence of Any Segrega

tive Intent Or Purposeful

Discrimination

B. The District Court Erred in

Holding That the Fourteenth

Amendment Imposed upon the

State an Affirmative Duty to

Reduce Any De Facto Segrega

tion that May be Foreseen

C. The District Court Erred in

Holding That the Fourteenth

Amendment Was Violated be

cause School District Bound

aries Conformed to Patterns

of Residential Segregation.

D. The District Court Erred in

Holding That the Fourteenth

Amendment Is Violated by a

State's Refusal to Consider

Racial Criteria in Its

Official Actions.

E. The District Court's Remaining Conclusions of Law

Are Irrelevant to this Case.

V These contentions are drawn fromin the respective briefs, except

Turtle Creek, the contentions of

the text of the brief.

**/ See Table of Contents, supra.

16 I.A.1,2 22

19 I.A.1,2 22

25 I.A.1 22

29 I.C. 42

I.A.1,2 22,31

the tables of contents in the case of Edgewood-

which are drawn from

iv

Appellants' Contentions Response

Page Section Page

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

FASHIONING THE MULTI-DISTRICT

REMEDY IT CHOSE 41 II 50

A. The District Court Erred in

Merging School Districts That

Were Not Shown To Be Involved

in the Supposed Violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment 41 II.A.B.1 50,51,56

B. The District Court Erred in

Failing To Join the Appellant

School Districts For A Hearing

on Their Involvement or Non-

Involvement in the Constitu

tional Violation 44 III 75

C. The District Court Erred in

Ordering Edgewood School Dis

trict Merged Because the Evi

dence Affirmatively Shows That

Edgewood Would Not Have Been

Merged By the County and State

Boards In the Absence of a

Constitutional Violation 46 II.B,1,2 56,62,

C. The District Court Erred in

Ordering Turtle Creek Area

School District Merged Be

cause the Evidence Affir

matively Shows That Turtle

Creek Would Not Have Been

Merged By The County and

State Boards In the Ab

sence of a Constitutional

Violation 48 II.B.1, 56,62,

Swissvale

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S 1973

DETERMINATION THAT THE BOARDS

VIOLATED THE FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT RESTED ON ERRONEOUS LEGAL

AND FACTUAL PREMISES 3 I. 20

(b)3,II.C. 66,81

2(d),3

II. C.

68,71

v

Appellants' Contentions Response

Section Page

A. The District Court, Without

Finding Segregative Intent,

Erroneously Concluded That

the Action of the Boards

Violated the Fourteenth

Amendment Merely Because

It Produced Segregative

Effects 3 I.A. 22

1. The District Court Made

No Finding That the Boards

Acted With Segregative

Intent 5 I.A.1,2 22,31

2. The Record Would Not Have

Supported Such a Finding 13 I.B.1,2 23,36,40

The District Court Erroneourly

Concluded That the Boards'

Action Violated the Fourteenth

Amendment Because It Yielded

To The Racially Motivated

Desires of the Surrounding

Municipalities 24 I.B.1,2 34,36,40

1. The Findings That the Boards'

Action Was Designed To Ac

commodate The Desires of the

Surrounding Municipalities

Were Clearly Erroneous As To

Some, if Not All, Municipal

ities 26 I.B.1,2 34,36,40

2. The Finding That the Municipal'

ities Were Racially Motivated

Was Clearly Erroneous 28 I.B.1,2 34,36,40

3. The Finding of Racial Motiva-

vation On the Part of the

Municipalities Would Not In

Any Event Establish a Con

stitutional Violation By the

Boards In the Absence of

Evidence Or Findings That

the Boards Themselves

Shared or Knew of That

Motivation 31 I.A.1,2 20,22,31

vi -

Appellants' Contentions Response

II.

III.

Page Section

4. The Court's Conclusion That

the Fourteenth Amendment

Was Violated Failed For Want

of a Finding That Either the

Municipalities or the Board

Would Have Acted Differently

But For The Racial Factor

C. The District Court Erroneously

Concluded That Discrimination

By Real Estate Brokers Con

verted De Facto School Segre

gation Into De Jure Segrega

tion

D. The District Court Erroneously

Concluded That the Boards

Violated the Constitution

By Refusing To Consider Racial

Criteria

EVEN IF THERE WAS A CONSTITUIONAL

VIOLATION, THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED

IN INCLUDING SWISSVALE IN THE REMEDY 43 II.A.B.

1 ,B.2(c )

B. 3 ,C

IF THIS COURT CONCLUDES THAT CHURCH

ILL MUST BE EXCLUDED FROM THE REMEDY,

IT SHOULD REMAND THE CASE TO THE

DISTRICT COURT FOR A CONSIDERATION

OF REMEDIAL ALTERNATIVES 47 II.C

Churchill

IT IS NOT A VIOLATION OF THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT FOR A STATE TO

MAINTAIN ADJACENT SCHOOL DISTRICTS

WHICH HAVE DISPARATE PROPORTIONS

OF MINORITY STUDENTS 18 I.A.l 2

32 I.A.1,2

35 I.A.1

38 I.C.

- vii -

Page

20,22,31

22

42

50,57,

56,68,

71

74

20,22,31

Appellants' Contentions Response

Page Section Page

II. IT IS NOT A VIOLATION OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT FOR THE

STATE TO DRAW BOUNDARY LINES

SEPARATING SCHOOL DISTRICTS SO

THAT A DISTRICT ON ONE SIDE OF

THE LINE HAS A DISPARATE NUMBER

OF MINORITY STUDENTS 18

A. There Can Be No Violation of

the Constitution in the

Absence of Evidence of Segre-

gatory Intent. There is No

Such Evidence in This Record... 21

B. The District Court Exacerbated

Its Error of Avoiding Any

Finding of Intent by Putting

the Burden of Proof of

Absence of a Violation on

the Defendants 22

C. The Court Erred in Finding

Tht the School Authorities

Acted to Satisfy the Desires

of Surrounding Municipalities 23

D. Refusal to Consider Race as

a Factor in Drawing School

District Lines Was Not the

Establishment of an Improper

Racial Classification 24

III. THE COURT ERRED BY INCLUDING

CHURCHILL IN THE REMEDY. IT WAS

NEITHER INVOLVED IN NOR AFFECTED

BY ANY CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION THAT

MIGHT HAVE OCCURRED 26

A. There Is No Evidence in the

Record to Establish That Church

ill Was Involved in or Affected

by Any Constitutional Violation 27

B. Churchill Was Established Under

Act 299 and Could Not Have Been

Merged With General Braddock

Under Act 150 34

I.A.1,2

I.B.1 ,2

I.A.1,2

I.B.1,2

I. C

II. A,B , C

II.B,1,2

(a),3 ,C

II.A,B,1

20,22,31

34,36,40

20,22,31

34,36,40

42

50,51,56

50,51,56

50,51,56

- viii -

Appellants' Contentions Response

gage Section Page

IV. THE SCHOOL DISTRICTS SUBJECT TO

THE REMEDIAL ORDER SHOULD HAVE

BEEN AFFORDED A COMPLETE HEARING

ON THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF THE

ALLEGED VIOLATIONS 37 H I

Commonwealth

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING

A CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION WHEN IT

DID NOT FIND AND COULD NOT HAVE

FOUND THAT DEFENDANTS ACTED WITH a

PURPOSE OR INTENT TO SEGREGATE 18 I.A.1,2 78

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN ITS

DENIAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH

DEFENDANTS' PRE-TRIAL MOTIONS TO

JOIN THE APPELLANT SCHOOL DISTRICTS 21 III 78

III. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO

PROVIDE THE APPELLANT SCHOOL DISTRICTS

A HEARING ON THEIR INVOLVEMENT OR NON

INVOLVEMENT IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL

VIOLATION 26

Allegheny Intermediate Unit

1. Was the District Court's 1973 decision

holding that the State and County

Boards of Education violated the 14th

Amendment in establishing the General

Braddock Area School legally erro

neous and factually unsupported by the Record? 4

(a) Did the State and County Boards

have an affirmative constitutional duty to

reduce interdistrict racial imbalance not of their own making? 4

I.B.1,2 34,36,40

I.A.1,2 20,22,31

- ix -

Appellants' Contentions Response

Paqe Section Page

(b) Did the State and County Boards

violate the Constitution by refusing to con

sider race in their redistricting plan? 4 I.C. 42

(c) Was the District Court's

holding of unconstitutional de jure

segregation legally erroneous in the

absence of any finding, or any factual

bassi for a finding, that the Board acted

with segregative intent? 4 I.B.1,2 34,36,40

Amicus Curiae, Pennsylvania School Board Ass'n

I. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN FINDING

UNCONSTITUITONAL SEGREGATION IN

THE CREATION OF THE GENERAL

BRADDOCK AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT

WHERE THERE WAS NO INTENTIONAL

OR PURPOSEFUL SEGREGATIO AND THE

GENERAL BRADDOCK AREA SCHOOL

DISTRICT WAS NOT A SEGREGATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT 6 I 20

A. General Braddock was not

created with segregative

intent or purpose 7 I.A.1,2 22,31

B. No segregated condition was

created by the creation of

General Braddock 14 B.1,2 34

II. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN ABOLISHING FIVE (5) SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND

CREATING A NEW ONE WHERE THERE WAS

NO EVIDENCE THAT MERGER WAS NEC

ESSARY OR THAT IT WAS CONSISTENT

WITH THE NATURE OF THE VIOLATION

FOUND BY THE LOWER COURT 18 II.A.B.C. 50,51

56,71

A. The abolition of school districts

is not supportable 9 II.A.C. 50,51

74

. B. A merger is not necessary to

achieve better racial balance 21

- x -

II.C 74

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

ACLU v. Board of Public Works, 357 F. Supp. 877 (D. Md.

1972) ............................................... 84

Aguayo v. Richardson, 473 F.2d 1090, 1100-01 {2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1 146 (1973) .... ............ 83

Appeal of Braddock Hills, 445 Pa. 343, 285 A.2d 880

(1971 ) ......... .................................... 67,68

Arthur Nyquist, 573 F.2d 134 (2d Cir. 1978), cert

denied, 439 U.S. 860 (1979) ........................ 25,26,29,42

Barr v. Rubber Products Co. v. Sun Rubber Co., 425

F.2d (2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S.878 ( 1971 ) ......... ......................... ...... 83

Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .... 35

C.F. Richardson v. Pennsylvania Department of Health,

561 F. 2d 489 (3d Cir. 1977) .................. ..... 29

Chartiers Valley Joint Schools v. Countv Board, 418 Pa.

250, 21 1 A.2d 487 ( 1965) ........ .................. 10,1 1 ,84

City of Memphis v. Greene, U.S. , 67 L.Ed.2d

769 ( 1981 ) ......................................... 25

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) .................. 28,29,35,42,52,

72,73

Continental Insurance Co. v. Cotten, 427 F.2d 48

(2d Cir. 1970 ) .............................. 83

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala.), aff'd,

336 U.S. 933 (1949) ..................... 25

Davis v. School District, 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir. 1971),

cert.denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1972) ...... ............ 27

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman I, 433 U.S.

406 ( 1977) ......................................... 39,71,73

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman II, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) .................................... 28,29,42,72,73

Page

- xi -

gage

De La Cruz v. Tormey, 582 F.2d 45, 58 (9th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 441 U.S. 965 (1979) .................. 29

Diaz v. San Jose Unified School District, 612 F.2d 411

(9th Cir. 1979) ................................... 27,28,29

Donohue v. Board of Electors, 435 F. Supp. 957 (E.D.

N.Y. 1 976) .......................................... 83

Evans v. Buchanan II, 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del) (3-judge

court), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1975) ............... 47,48,49,58,

82,83

Evans v. Buchanan III, 416 F. Supp. 328 (D. Del. 1976),

aff'd, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir. 1977)(en banc),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 934 (1978) ...... ....51,52,53,55,57,58,

71,72,73,75,76

Evans v. Buchanan V, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir. 1977)

(en banc), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 934 (1978) ___ 50,51,52,53,

56,57,77

Evans v. Buchanan VI, 435 F. Supp. 832 (D. Del. 1977),

aff'd, 582 F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978) (D. Del 1977),

cert, denied, 446 U.S 923 (1980) .......... . 75

Evans v. Buchanan VIII, 582 F.2d 750, 762-67 (3d Cir.

1978), (en banc), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 923

(1980 ) ............ 50,51,55,72,73,

75,77

Flores v. Pierce, 617 F.2d 1386 (9th Cir. 1980),

cert, denied, 101 S. Ct. 268 ( 1 981 ) ....... ....... 27,30

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S 747

(1 976) ............................................ 50

Gentry v. Smith, 487 F.2d 511 (5th Cir. 1973) ......... 82

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974) .... 50,74

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ........... 28

Government of Virgin Islands v. Gereau, 523 F.2d 140(3d Cir. 1975) ........................... 41

Griffin v. Board of Education, 239 F. Supp. 560 (E.D.

Va. 1965) (3-judge court) ......................... 84

xii

Page

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .... 26

Hadco Products, Inc. v. Frank Dini Co., 401 F.2d 462

(3d Cir. 1968) ............................. ....... 34,39

Haney v. Board of Education of Sevier County, 410

F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) ........................... 55

Hazelton Area Shool District v. State Board, 364

A.2d 660 (Pa. 1976), aff'q 347 A.2d 324

(Cmwlth Ct. 1975) ....... .......................... 84

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 ( 1 975) ........... 51,52,53,56,57,

71,73

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots I),

334 F. Supp. 820 (W.D. Pa. 1 971 ) ................ . 4,21,68,78

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots II),

359 F. Supp. 807 (W.D. Pa. 1973), appeal dism'd,

495 F.2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S.

884 (1974) .......................................... passim

Hoots V. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots III), 495

F.2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 884

(1974) ....................................... 4,5,34,79,82,83

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots IV),

587 F. 2d 1340 (3d Cir. 1 978) .... ............... 4,6,10,34

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots V ), 639

F.2d 972 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, U.S. ,

69 L. Ed. 2d 974 (1981 ) .....................777.... 4,6,7,34,

50,74,77,81

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots VI), 510

F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Pa. 1981) ........................ passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots VII),

No. 71-538 (W.D. Pa. Apr. 6, 1981 ) ...... ......... 4,8,9,75,77

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Hoots VIII),

No. 71-538 (W.D. Pa. Apr. 28, 1981) ....... 4,8,9,14,34,38,41,

59,67,73,75,76,77

Husbands v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

359 F. Supp. 925 (E.D. Pa. 1973) ................. 84

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 ( 1965) ................ 46,47

xii i

Insurance Group Committee v. Denver & Rio Grande R.,

329 U.S. 607 ( 1947 ) ............................ . 79

Kaplan v. International Alliance, 525 F.2d 1354 (9th

Cir. 1975) .......... ..................... ......... 82

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 412 U.S. 189 (1973) __ 31,32,33,39,

72,73,79

Lee v. Macon County, 267 F.2d 458 (M.D. Ala.) (3-judge

court), aff'd, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) .................. 84

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1970)

(3-judge court), aff'd, 401 U.S. 935 (1971) ...... 46,48,49

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) .................. 46,47

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ............. 47

Milliken v. Bradley I, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ......... 7,32,33,34,51,

42,53,54,55,61

72,74,77,79,80,

81,82,84

Milliken v. Bradley II, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ............ 51

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) .......... 26

Moore v. Knowles, 482 F.2d 1070 (5th Cir. 1973) ........ 83

Morrilton School District No. 32 v. United States,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

444 U.S. 107 ( 1 980 ) ................................ 52,53,55

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F.2d 1042

(6th Cir. 1977), cert.' denied, 434 U.S.

997 (1978) ..................................... 29

National Welfare Rights Organization v. Wyman,

304 F. Supp. 1346 (E.D.N.Y. 1967) ............... . 83

North Carolina Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 31 (1971) ..................................... 48

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979) ............................................ 23,24,29,

35,42

Provident Tradesmen Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson,390 U.S. 102 (1968) ........................... 82

Page

- xiv -

Page

Reed v. Rhodes, 607 F.2d 714, 735 (6th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 445 O.S. 935 ( 1980 ) .................. 28,29

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 ( 1978) ................................ 47

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) .......... . 25,47

Resident Advisory Board v. Rizzo, 564 F.2d 126 (3d Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 435 U.S. 908 (1978) ........ 24,25,26,27,

30,35,42,46

Sealy v. Department of Public Instruction, 252

F. 2d 989 (3d Cir. 1 958) ............... ............ 32

Seattle School Dist. No. 1 v. Washington, 633 F.2d1338 (9th Cir. 1980) ............................... 48

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 388 U.S. 301 (1966) ...... 83

State Board v. Franklin Township School District,

209 Pa. Super. 410, 288 A.2d 221, 224 (1967) ...... 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

401 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................. 32,47,48,50,74

Toney v. White, 476 F.2d 203 (5th Cir. 1973) ........... 83

Turner v. Warren County Board, 313 F. Supp. 380 (E.D.N.C. 1970) 56

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144(1977) .................................. 47

United States v. Board of School Commissioners, 513

F.2d 400 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S.

824 (1978) ..................................... 27,28,29,35,42,52,

53,55,56

United States v. Missouri, 363 F. Supp. 739 (E.D.

Mo. 1973), aff'd, 515 F.2d 1368 (8th Cir.), .

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 ( 1975) ................. 55,56

United States v. Missouri, 388 F. Supp. 1058 (E.D.

Mo*)» aff'd, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,423 U.S. 951 ( 1975) ..................... 53,55,

United States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365, 1369-71

(8th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951

(1975) ....................................... 53,55,56

- xv -

Page

United States v. School Dist. 151, 301

F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969), aff*d, 432

F.2d 1147 (7th Cir.) cert, denied, 402

U.S. 943 (1970) .......... ......................... 25,27

United States v. School District of Omaha, 565 F.2d

127 (8th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

1064 (1978) ..... ........................... ....... 29

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex.),

aff'd, 447 F. 2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971) .......... ..... 56

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 564 F.2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915

(1 979) ............................................ 26,27,28,29

United States v. Unified School District No. 500,610 F. 2d 688 ( 10th Cir. 1979) ...................... 29

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S.

374 ( 1948) ............................... .......... 35

United States v. United States Smelting, Refining &

Mining Co., 339 U.S. 186 (1949) .................... 32

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 338 U.S. 338

( 1 949) ............................. ................ 35

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ....___ 22,23,24,25,26,

27,28,29,30,31,

32,34,35

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....... 23,28,29,30,32,35

Whiting v. Jackson State University, 616 F.2d 116

(5th Cir. 1980 ) ................ ................... 27

Williams v. Anderson, 562 F.2d 2082 (8th Cir. 1977) .... 26

Zaslawsky v. Board of Education, 610 F.2d 661

(9th Cir. 1979) .................................... 47

CONSTITUIONAL PROVISIONS

U.S. Const., amend. 5 ................................... 83

- xvi -

Page

STATUTES AND ROLES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 1 9 ................................. 4,78,82,83,85

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 ............................... 4,78

Fed. R. Civ. P. 46 ................................. 39

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 ................................. 39

Fed. R. Evid. 201 .............................. 41

Act 561, September 12, 1961, P.L. 1283

No. 561 , 24 P.S. § 2-291, et. seq. ............ passim

Act 299, August 8, 1963, P.L. 564, No. 299, 24

P.S. § 2-290 se. seq. ......................... passim

24 P.S. § 2-291 ............................... 11

24 P.S. § 2-292 ............................... 1 1

24 P.S. § 2-293 ............. ................. 10,1 1

24 P.S. § 2-295 ..................... 10

24 P.S. § 2-296 ............................... 10

Act 150, July 8, 1968, P.L. 299, No. 150, 24 P.S.

§ 2400.1 ....................................... passim

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Final Report of the Governor's Committee on

Education ..................................... 10

3A Moore's Federal Practice ....................... 84

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, Policy

on Education.... ............................. 12

Sedler, Metropolitan Desegregation After Milliken,

1975 WASH. U. L. Q. 535 34

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure,

Civil ........................................ 82,83

-xvii-

LIST OF TABLES

Table(i): School Districts, 1961; Enrollment,

1964, 1967 ......................... 13

Table (ii): County Board Plan Under Act 561

(1964 Figures) ..................... 15

Table (iii): Final County Board Plan Under Act

299 (1967 Figures) ................ 16

Table (iv): Final Plan (1971, 1975, 1981

Enrollment Figures) ................ 20

Page

xviii

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

(1) Whether the district court's repeated finding, based on

extensive evidence, that Pennsylvania public school officials inten

tionally created GBASD and its neighbors as racially segregated

school districts is a sufficient basis for the court's constitutional-

violation determination.

(2) Whether the district court abused its discretion in conclud-

ing that the proper remedy in this case is to consolidate into one,

desegregated school district five pre-existing school districts that

public officials unconstitutionally created as segregated units in

the 1960's.

(3) Whether, over the course of ten years of litigation, during

all of which the former school districts were invited to, and during

much of which they did, participate, the district court as a matter of

law or fact denied the districts the requisite opportunity to be heard.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Notwithstanding Appellants' attempt to cloud these appeals with

a scatter-gun attack on various alternative findings and offhand

remarks by the district court over the ten-year course of this "long

and complex" litigation, Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 639

F.2d 972 (3d Cir. 1981), their contentions amount to no more than a

feeble assault on the sufficiency of the voluminous evidence support

ing the district court's violation and remedial determinations.

Applying the Fourteenth Amendment standard and multiple "eviden

tiary source[s]" test endorsed in Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro

politan Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265-67 (1977), the district

1

court properly concluded in 1973, and repeatedly since, that Pennsylva

nia officials violated the Constitution by drawing segregative

school-district boundaries "based wholly or in part on" and "because

of" the race of the students involved. Hoots v. Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp. 807, 822 (W.D. Pa. 1973). Although appel

lants microscopically analyze certain statements by the district

court that are "ancillary and supportive of" its "deliberate segrega

tion" conclusion, Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 334 F. Supp.

820, 822 (W.D. Pa. 1971), their only attack on that principal holding

is a futile sufficiency of the evidence argument belied by extensive

"direct" and "circumstantial" record evidence of intentional discrimi

nation.

Likewise, the district court properly applied the clear standards

in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 745 (1974), in granting inter

district relief "where district lines have been deliberately drawn on

the basis of race." Furthermore, the court properly defined the

scope of the violation, and determined, based on extensive record

evidence cementing each district to the State's invidious line-drawing

activities, that each of the districts was the product of and affected

by the violation. See Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284, 298-300

(1975); Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 208 (1973).

The record also demonstrates that, despite their deliberate

and inequitable resistance to participation, the appellant districts

all had a full opportunty to — and did — participate in the disposi

tion of every issue in this case. In any event, state law deprives

those districts of any vested interest in their state-drawn boundaries,

and they accordingly were not subject to mandatory joinder under

Fed. R. Civ. P. 19.

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Prior Proceedings

Plaintiffs are a class of parents (black and white) whose

children attended the public schools in General Braddock Area School1/District (GBASD) — a tiny (2.64 square miles; 2,042 pupils),

predominantly (63%) black school district located in central eastern

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, east of Pittsburgh, and bordered by

the predominantly or all-white Churchill (99.2% white), Turtle Creek

(98.1% white), Edgewood (97.8% white) and Swissvale (87.3% white)

school districts. (3233a.)

On June 9, 1971, plaintiffs filed this action, alleging that the

Pennsylvania State Board of Education ("the State Board") and the

Allegheny County Board of Education ("the County Board," later super

seded by "the Intermediate Unit"), in reorganizing school districts in

central eastern Allegheny County pursuant to three school-district-re

organization statutes enacted bv the Pennsylvania legislature in the 1/1960's, deliberately created GBASD as a segregated and identifiably

black school district in order to maintain the immediately contiguous

school districts (Churchill, Edgewood, Swissvale and Turtle Creek) as

segregated and identifiably white school districts. (20a-35a.) Named

in the complaint as defendants were the Commonwealth of Pennsylva

nia, the State Board, the County Board and several of their officers.

1/ By Order dated April 28, 1981 , the district court dissolved

GBASD and the four neighboring school districts and consolidated

them into one desegregated district. (896a.) Appellants' repeated

efforts to stay that order in the district court, this Court and the

Supreme Court were unsuccessful, and accordingly these districts are

no longer in existence. (3180a, 3181a, 3185a, 3186a, 3372a.)

2/ Act of September 12, 1961, P.L. 1283, No. 561, 24 P.S. § 2-281,

et seq. ("Act 561"); Act of August 8, 1963, P.L. 564, No. 299, 24

P.S. § 2-290, et se£. ("Act 299"); Act of July 8, 1968, P.L. 299,No. 15U, 24 P.S. § 2400.1 ("Act 150").

3

to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a cause of action,

concluding that "allegations of deliberate creation of a racially

segregated school district state a cause of action." Hoots I, 334

3/

F. Supp. at 822 (959a). The district court also rejected

motions by defendants seeking involuntarily to join as defendants

the five school districts discussed in the complaint. The district

court held that, because the defendant State and County Boards

"created [the five districts] without their assent and could ...

alter [them] similarly," those districts were not essential parties

whose joinder was mandatory under Fed. R. Civ. P. 19.. However, the

district court stated that it would permit the school districts

voluntarily to "intervene in this action under Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 if

they so desire.'" Id. at 823 (962a). The school districts did not so

desire. Instead, after the district court "instructed [the Common

wealth] to give notice" of the suit to the those school districts,

and after the Attorney General of Pennsylvania wrote the five dis

tricts "urg[ing]" them "to intervene in this action immediately," the

districts informed the district court that they had "no interest in

being" in the lawsuit, and were "deliberately not intervening."

(56a-61 a, 6l4a-18a, 2712a, 3383a, 3389a.) See Hoots II, 359 F. Supp.

at 821 (775a); Hoots III, 495 F.2d at 1097 (2848a).

In December 1971, the district court denied defendants' motion

3/ During its ten-year history, this case has been the subject of

six published opinions. A seventh and eighth opinion have not yet

been published. All eight opinions are captioned Hoots v. Common

wealth of Pennsylvania, and will be referred to here as Hoots I -

VIII, as indicated below: Hoots I, 334 F. Supp. 820 (W.D. Pa. 1971)

^958a); Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. 807 (W.D. Pa. 1973) (749a); Hoots

III_, 495 F. 2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 884 ( 1974)

(2846a); Hoots IV, 587 F.2d 1340 (3d Cir. 1978) (2653a); Hoots V,

639 F.2d 972 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, ___ U.S. , 69 L.Ed.2d 974

(1981) (2769a); Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Pa. 1981) (866a);

Hoots VII, Order and Opinion of April 6, 1981 (W.D. Pa.) (1378a);

Hoots VIII, Order and Opinion of April 28, 1981 (W.D. Pa.) (883a).

4

Trial was held on December 5 and 6, 1972. Plaintiffs intro

duced the testimony of three expert and five lay witnesses, as well

as 63 documentary, summary and/or graphic exhibits, which were admitted

into evidence pursuant to a stipulation of the parties. (696a.)

On May 15, 1973, the district court issued an opinion and order

holding that the State and County Boards' creation in the 1960's of

identifiably black GBASD and identifiably white Churchill, Edgewood,

Swissvale and Turtle Creek Districts "constituted an act of de jure

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment." Hoots II,

359 F. Supp. at 823 (779a). The district court thereupon ordered

defendants to "prepare and submit to this Court within 45 days from

the date of this Order a comprehensive plan of school desegregation"

which "shall alter the boundary lines of [GBASD] and as appropriate of

adjacent and/or nearby school districts." Id. at 824 (781-82). Defen-

1/dants did not appeal.

Defendants did not submit a "comprehensive plan of school

desegregation" within 45 days. Indeed, over the course of the next

eight years, after granting defendants numerous extensions of time

within which to develop effective desegregation plans, the district

court found it necessary to reject as inadequate all six plans

(Plans 22W, A, B and Z, the Tuition Plan and the Upgrade Plan) sub-

4/ After the district court entered its May 15, 1973 decision,

Churchill, Edgewood, Swissvale and Turtle Creek petitioned to

intervene. The district court granted these petitions insofar as

they sought prospective intervention, but denied them insofar as

they also sought retroactive intervention. (996a.) Two districts

(Churchill and Turtle Creek) appealed the partial denial of their

motions. This Court affirmed the district court, holding that the

retroactive intervention petitions were "untimely." Hoots III, 495

F.2d at 1097 (2848a.) The Supreme Court denied certiorari. 419 U.S. 884 (1974).

5

1031a, 1378a-81a.) All but one of defendants' plans were inter

district in nature, and all but two called for the consolidation of

some or all of the school districts presently involved in this case

into one or more new school districts. See generally, Hoots IV, 587

F.2d at 1344-46 (2657a-59a); Hoots V , 639 F.2d at 975-77; id. at

984-86 (Higginbotham, J., concurring) (2772-74a, 2781a-83a). During

this 1973-1980 period, the district court also twice (in October 1975

and October 1980) permitted defendants to present additional evidence

and argument relevant to the violation (as opposed to the remedy).

(2684a-706a, 2929a-3015a.) On both occasions, the district court

reaffirmed its finding of a constitutional violation based on all of

the evidence before it. (874a, 892a, 2761a-62a, 3201a-02a.)

Plaintiffs twice appealed during this period. In both in

stances, plaintiffs asked this Court for a remedial order ending

school segregation in central eastern Allegheny County, which re

mained unremedied — and worsened (3233, 3243a-57a) — during the

1973, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979 and 1980 school years.

Although this Court dismissed plaintiffs' first appeal in 1978, it

stated that it was "confident that — an appropriate final order"

would "be entered by year end" 1978. Hoots IV, 587 F.2d at 1351

(2664a.) In August 1980, after the district court denied plaintiffs'

5/ In addition to the Commonwealth and the Intermediate Unit, the

Swissvale and Churchill districts participated as defendants in all

of the proceedings in this case from October 1973 to the present. GBASD voluntarily intervened in February 1979 (2588a), and the Court

mandatorily joined the Edgewood and Turtle Creek districts in May

1979 (853a). During the 1973-1975 period, the district court

thrice remanded the case to the State Board for remedial hearings,

the transcripts of which are part of the record. (1128a-29a, 3194—

95a.) All of the school districts presently involved in this case

participated actively in the State Board's hearings. E.q., 9/10/73 St. Bd. Tr.; 3/6/74 St. Bd. Tr.

mitted by the Commonwealth and the defendant districts.- (843a,

6

motion for injunctive relief for the second school year since

1978, plaintiffs again appealed. In Hoots V , issued on January 26,

1981, this Court granted plaintiffs the following relief:

We believe it to be essential that the

district court afford relief to [plaintiffs]

that will be effective in the fall of 1981.

Under no circumstances should a new school

year begin in the fall of 1981 without an

acceptable remedial plan in place.

Accordingly, we order the district court

... within ninety days of the issuance of the

mandate [to]: (1) complete all hearings and

necessary proceedings on the merits of the

competing remedial plans for the desegregation i

of GBASD; (2) decide the Milliken v. Bradley

issue of which school districts may be included

within an interdistrict remedy; and (3) enter

an appropriate final order granting [plain

tiffs] the relief to which they are entitled

under the district court’s order of May 15,

1973, such relief to be effective and imple

mented by the beginning of the first semester

of the school year in the fall of 1981.

Hoots V , 639 F.2d at 980-81 (2777a-78a).

On March 5, 1981, the district court entered an opinion and

order deciding the so-called Milliken v. Bradley issue. The district

court reaffirmed its 1973 "interdistrict violation" finding, concluded

that the racially motivated "drawing or redrawing of ... boundaries"

involved seven central eastern area school districts (including the

five districts presently involved in the case), and determined that

"a multi-district remedy" involving some or all of those districts

was "appropriate." Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 619 (874a). On March

26, 1981, plaintiffs filed a five-district consolidation plan con

forming to the district court's March 5 guidelines. (1409a.)

Subsequently, on April 6, 1981, the district court rejected the

only two remedial plans filed by defendants since 1975— the Upgrade

Plan and the Tuition Plan — because neither could "achieve effective

7

desegregation." Hoots VII, at 2, 4 (1379a, 1381a). Based on "all

of the hearings held," the district court also concluded "that only

an interdistrict remedy is feasible here, and ... that only a single

district formed from the consolidation" of pre-existing districts

would solve the "many difficulties" revealed in "prior hearings" on

defendants' plans. Id. at 3 (1380a). The court accordingly

scheduled hearings tor April 20-23, 1981, "to determine the districts

to be consolidated" in a single new district. Id. at 4 (1381a). At

those hearings, plaintiffs presented expert testimony favoring a

five-district consolidation of Churchill, Edgewood, GBASD, Swissvale

and Turtle Creek. The school districts other than GBASD (using only

one of the two days that the district court allotted to them) pre

sented lay and expert testimony in opposition to a five-district

plan. (1690a, 3215a.) GBASD supported plaintiffs' plan. (3435a.)

On April 28, 1981 ,. the district court entered its first remedial

order since it found the constitutional violation in 1973. Hoots

(883a). Reiterating its prior finding that the "intentional

creation [of GBASD] as a racially identifiable black district

constituted the constitutional violation found in this case," the

district court held "that a new school district composed of the

present school districts of Churchill, Edgewood, Swissvale, General

Braddock and Turtle Creek would achieve desegregation [and] the

highest beneficial results over and above the results of any other

plan submitted to this Court by any party during the whole period of

this litigation." Id. at 6, 9 (889a, 892a). The court accordingly

ordered those five districts consolidated into a "New School Dis

trict," which it then ordered to desegregate itself. _Id. at 17

(900a).

8 -

Finally, after still further hearings, the district court

entered two orders on July 23 and August 13, 1981, setting forth

the details of a plan of desegregation of the*8 New District. That

plan was implemented on September 8, 1981, and the school children of

central eastern Allegheny County are presently attending desegregated

schools for the first time in ten years. Orders of July 23 and

August 13, 1981.

None of the defendants, including the newly joined New School

District, appealed the district court's final desegregation orders.

However, some of the defendants appealed certain aspects of the

district court's 1973 decision in Hoots II and its spring 1981

6/decisions in Hoots VI, Hoots VII, and Hoots VIII. This Court

consolidated those appeals by order of August 20, 1981.

B. Facts

1. The Reorganization Acts and administrative guidelines

In the I960's, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania em

barked on an ambitious program of mandatory statewide reorgan

ization and consolidation of existing school districts. In fur

therance of this program, the Pennsylvania legislature passed

three statutes, Act 561 in 1961, Act 299 in 1963 and Act 150

in 1968. See note 2, supra. "[T]he legislative objective em-

6/ Six defendants below, the former Churchill, Edgewood, Swiss-

vale and Turtle Creek School Districts ("the former school dis

tricts"), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania ("the Commonwealth"),

and the Allegheny County Intermediate Unit Board of School Direc

tors ("the Intermediate Unit") have appealed. Three defendants

below, the school districts of East Allegheny, Gateway and the "New

School District," have not appealed. GBASD is proceeding here as

an appellee. The term "appellants" will be used to refer collec

tively to those defendants that have appealed.

- 9 -

I

bodied in [these statutes was] the prompt and expeditious reorgani

zation of the Commonwealth's public school system in order to

/

accomplish fewer and larger administrative units." Chartiers

Valley Joint Schools v. County Board, 418 Pa. 250, 211 A.2d 487, 494

(1965). Accord, Hoots IV, 587 F.2d at 1342 (2655a); Hoots VI, 510 F.

Supp. at 617 (869a).

Although the three acts (each of which superceded all earlier

legislation) differed in certain procedural respects, they were

virtually identical in substance. Because of the failure of

earlier voluntary reorganization efforts, the acts emphasized the

7/

Boards' responsibility to mandate school district consolidations,

and required the County Board to propose, and the State Board

to review, revise (if necessary), and then order, school district

consolidations. E.g., 24 P.S. §§ 2-293(a), 2-295, 2-296. The acts

also gave the State and County Boards authority to require dis

tricts that were previously formed by the voluntary merger of two

or more districts to consolidate into even larger districts, and to

merge existing districts that already met statutory requirements

7/ The reorganization statutes were passed in response to the

Final Report of the Governor's Committee on Education, see

Chartiers Valley Joint Schools v. County Board, 211 A.2d at 494-95

n.18, which concluded that:

There can be no doubt that most of our school

districts and even our joint school systems are

too small to offer an adequate program. ... The

lesson is plain. There can be no true reorganiza

tion of school districts unless it is mandated

by the state. The choice is simple. Either we

mandate reorganization or we do not reorganize.

Report, supra, quoted in id.

10

into larger districts, so long as such a merger would aid the

less healthy districts involved in the merger. Hoots VI, 510 F.

Supp. at 617-18 (870a); 304a, 307a-08a, 446a, 585a.

In carrying out their district-consolidation responsibilities,

the County and State Boards were directed by the acts to comply with

certain reorganization standards set forth in the statute and with

such additional guidelines as the State Board promulgated. E.g. , 24

P.S. §§ 2-291, 2-292. Chief among the statutory reorganization

standards was the requirement that no reorganized school district

"contain a pupil population of less than four thousand (4,000),"

except in "unusual" circumstances, ^d. § 2-293(a); Chartiers Valiev

Joint Schools v. County Board, 211 A.2d at 494. The State Board's

reorganization guidelines interpreted this 4000-pupil standard as

only a starting point, and required reorganized school districts, in

addition, to "include the largest feasible pupil population which

assures the maximum efficiency of operation, and which justifies

curricular offerings and other essential services not economically

8/possible in smaller administrative units." (320a; see also 660a.)

The district court also found as a fact that two race-related

administrative regulations governed the State and County Boards'

district-consolidation activities during the 1960's. Hoots II, 359

F. Supp. at 812, 819-20 (754a, 771a-72a). The first was an "Affirma

tive Action Policy on Education" promulgated by the Pennsylvania

8/ Additional statutory and administrative standards required the

Boards to consider contiguity, transportation, existing facilities,

community characteristics, future population changes, and in

general to make each district large enough to "promote a comprehen

sive program of education." 24 P.S. § 2-291; 319-21 a, 660-61 a; see

Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 819-20 (771a-72a); note 31, infra.

Human Relations Commission (HRC) in the early 1960's (simultaneously

with Act 299) and repromulgated in 1968. (246a-52a, 574a, 652a.)

Under that Policy, the HRC required public school officials in Penn

sylvania to take certain steps to end all forms of segregation in the

1/public schools of Pennsylvania — de facto as well as de jure.

The second applicable guideline on race was promulgated by the

State Board in 1963 (under Act 299) and again in 1968 (under Act

150). This guideline provided that:

Race, religion, national origin and differ

ences in the social and economic levels of

the population shall not be factors in

determining administrative boundaries.

(660a; see 320a.) The existence of two conflicting interpreta

tions of this latter guideline caused considerable controversy during

the 1960's. (256a-58a.) One ("segregation blind") interpretation,

9/ The HRC Policy on Education states:

Even when school segregation is the result

of housing conditions and not because of deliberate

discrimination, the Commission feels it is necessary

that affirmative steps must be taken by boards of

public school districts to alleviate racial imbalance,

regardless of its cause....

To help eliminate de facto segregation and

to accelerate total integration, the boards of

education of the public school districts throughout

Pennsylvania should observe the following guidelines:

1. Every public school district must strive to

foster desegregation and integration of schools....

2. Each public school should enroll pupils

from varied backgrounds to the fullest possible

extent. Public school enrollment should be a

part of a comprehensive plan for the entire district

rather than local neighborhood interests.

3. Boundary lines within public school

districts should be redrawn to effect integrated

student bodies.

(575a-76a.)

1 2

which placed this guideline directly in conflict with the HRC regula

tion quoted in note 9, supra, permitted officials to draw boundary

lines that maintained and perpetuated pre-existing racial segregation

among school districts, even where such segregation was "recognized"

as a gravely serious problem. (701a-02a, 2702a.) The second

("segregation opposed") construction prohibited both "de facto

segregation on the basis of race" and "de jure segregation, through

the fixing of school boundaries ... for racial __ reasons." (573a,

see 256-58a.) Although late in 1968, after all of the school-district

reorganiztion decisions relevant to this case had been made, the

State Board officially acknowledged that the "segregation opposed"

intrepretation was the proper one, the County and State Boards

stipulated that when they drew the school district boundaries in

central eastern Allegheny County, they applied the improper, "segrega

tion blind," interpretaion. Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 818-19 (767a-

68a); 257a-58a, 573a, 701-02a.

2. The creation of GBASD and the former districts

When the Pennsylvania legislature passed Act 561 in 1961,

the following school districts were operating in central eastern

Allegheny County:

Table (i): School Districts, 1961; Enrollment, 1964, 1967

1961 District (Post-Re

organization District)

(331a-36a, 417a-

1964 Enrollment

-20a,

1 967

476a, 498a

Enrollment

Total % Black Total % Black

Braddock (GBASD) 1436 56% 1303 63%

Rankin (GBASD) 678 46% 614 51 %

N. Braddock (GBASD) 2293 14% 2071 20%

Brad. Hills (Swissv.) 433 10% "V 2350 10%

Swissvale (Swissv.) 1897 6% JE. Pitts . (T. Creek) 516 14% 411 6%T. Creek (T. Creek) 1709 0% 1487 0%

Edgewood (Edgewood) 824 0% 976 0%

Wilkins (Church. ) -nF. Hills (Church.) V 4828 0% 5810 0%

Chalfant (Church. )

13

Although administratively distinct, all of these districts

had important interconnections during the early 1960's in the form of

"tuition" arrangements (under which one district educated another

district's students in return for tuition payments), commercial

11/ties and voluntary-merger negotiations. Opposed to these

centripetal forces, however, was an important centrifugal force: "the

State and County Boards in devising the plan of administrative units

for the central eastern portion of Allegheny County were influenced

by the desires of the sourrounding municipalities to avoid being

placed in a district with Braddock and Rankin because of the high

concentration of blacks in these two municipalities." Hoots II, 359

F. Supp. at 821. Although the district court based its intentional-

segregation finding on numerous factors (see pp. 25-31, infra), it

placed particular emphasis on the Boards' unbroken pattern of compli

ance with their constituents' racially motivated demands. Hoots II,

359 F. Supp. at 816-17, 821, 822 (764a, 774a, 777a-78a). Accordingly,

the remainder of this factual statement is devoted to a discussion of

the portions of the record cited by the district court in support

19/

10/ In Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 617 (870a), the district court

found that on "May 15, 1962," i.e., after Act 561 was effective, but

"before the County Board had established [an Act 561] plan for

reorganization, Chalfant, Wilkins and Forest Hills voted to voluntar

ily merge into a single district, [Churchill, which] was later

approved by the State Board on June 25, 1962."

11/ For example, prior to merging into the Churchill district, the pre-existing districts of Chalfant, Wilkins and Forest Hills:

educated their high school children in Edgewood and Turtle Creek

pursuant to tuition arrangements; discussed the possibility of

merging with Braddock Hills and Turtle Creek; and had commercial ties

with Rankin, Edgewood, Braddock Hills, and Turtle Creek. Similar

ties linked North Braddock with Braddock Hills, Turtle Creek and East

Pittsburgh; Rankin with Forest Hills and Swissvale; and Edgewood with

Braddock Hills and Wilkins. (117a-26a, 303a, 446a-49a, 582a, 585a,

589a-90a, 622a, 642a) See Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 817-18 (766a);

Hoots VIII. at 9-11 (892a-94a).

14

of that conclusion. See id. at 816-17 (764a).

In September 1962, the County Board proposed the following

Act 561 reorganization plan for the school districts in central

eastern Allegheny County:

Table (ii): County Board Plan Under Act 561 (1964 Figures)

(292a, 331a-37a, 476a , 498a..

UNIT: Districts involved Enrollment % Black

UNIT 12: Gateway/T. Creek 8660 1%

UNIT 13: Wilkins/Chalfant/F. Hills 4836 0%

UNIT 14: Braddock/Rankin/N.Brad./

E. Pitts./Brad. Hills 5356 29%

UNIT 15: Swissvale/Edgewood/

Wilkinsburg 7350 14%

TOTAL 27,211 10%

This proposal encountered immediate opposition from Braddock

Hills, which objected to being placed in an adminstrative unit that

included Braddock and Rankin but did not include the recently formed

Wilkins-Chalfant-Forest Hills (i.e., Churchill) district. (447a-48a;

see note 10, supra.) Because the legislature repealed Act 561 in

1963, the Allegheny County plan was never formally adopted. See

State Board v. Franklin Township School District, 209 Pa. Super. 410,

228 A.2d 221, 224 (1967).

In place of Act 561, the legislature enacted Act 299, pursuant

to which the bulk of the violational activity cited by the district

court occurred. Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 617-18 (879a-21a). The

first reorganization plan considered by the County Board under Act

299 simply replicated its Act 561 proposal. See Table (ii), supra.

Once again, however, Braddock Hills vehemently objected to its

15

inclusion in a unit with Braddock and Rankin but without its neighbor

to the east, Churchill. (585a-91a. ) Braddock Hills officals at

tributed the County Board's exclusion of Churchill to that district's

"objections ... based on politics, race, color and creed [that] are

not acceptable under the law known as Act 299." (588a.)

In a May 1964 compromise designed to mollify Braddock Hills

(585a), the County Board removed Braddock Hills from the Braddock/

Rankin unit, but included it in a sub-4,000-pupil district with

Swissvale and Edgewood rather than in a 4000-plus district with

Churchill. (331a-37a, 585a.) Turtle Creek was substituted for

Braddock Hills in the Braddock/Rankin unit:

Table (iii): Final County Board Plan Under Act 229 (1967 Figures)

(331a-37a, 476a, 696a-97a)

UNIT: Districts involved (present district) enrollment % Black

UNIT 15: Wilkins/Chalfant/F.Hills (Church.) 5810 0%

UNIT 16: Braddock GBASD) 1303 64%Rankin (GBASD) 614 51%N. Braddock (GBASD) 2079 20%E. Pittsburgh (T. Creek) 41 1 6%T. Creek (T. Creek) 1487 0%Total 5894 27%

UNIT 19: Swissv./Brad. Hills (Swissv.) 2350 10%Edgewood (Edgewood) 976 0%Total 3326 7%

TOTAL 1,5030 12%

Following Braddock Hills' example, Turtle Creek (0% black) and

East Pittsburgh (6% black) now began to place intense pressure on

the State and County Boards to remove them from the unit with

Braddock (64% black) and Rankin (51% black). These secessionist

efforts began with a letter and petition campaign in which Turtle

16

Creek and East Pittsburgh citizens informed the Boards that they

did not want to "send [their] child[ren]" to school with "colored

people [of] the kind that live in North Braddock, Braddock and

Rankin. (299a-301a, 698a~99a.) The Turtle Creek and East Pitts

burgh municipal governments also officially protested their inclu

sion with Braddock, Rankin and North Braddock in the County Board's

plan. As had Braddock Hills before them, they sought to have

Churchill included in their district. (698a; Pretrial Statement of

County Board, Docket No. 54, at K 7.) Alternatively, they were

willing to merge with Gateway or East Allegheny, or be joined in a

sub-4,000 pupil unit composed solely of themselves. (307a-10a,

579a-80a, 698a.) In August 1964, State Board staff members reported

to the Board that, faced with the East Pittsburgh-Turtle Creek

campaign, some County Board members were now of the opinion that

predominantly white Turtle Creek and East Pittsburgh should be

separated from predominantly black Braddock and Rankin and placed

_12/together in a "socio-economic[ally] homogenous unit."

In response to this campaign, Braddock School Board Member

Thomas Harper and NAACP Chapter President LaRue Frederick jointly

wrote to State and County Board officials opposing the efforts to

isolate Braddock and Rankin from their neighbors. Harper and

Frederick attributed those efforts to fears of an "influx of a large

number of Negro students into heretofore predominantly white units."

(592a-93a.) These claims were verified in court by Joseph Suley, a

member of the North Braddock Board of School Directors during the

~ / "Economically," Braddock and Rankin, on the one hand, and

East Pittsburgh and Turtle Creek, on the other, were virtually

identical communities in the 1960's. (341a-79a, 599a-613a.)

Socially, " they differed in only one respect— race. Hoots II,■359 F. Supp. at 816 (762a-64a).

17

reorganization battles. Mr. Suley testified that, throughout the

1960's, municipal officials in the area opposed merger with Braddock,

Rankin and North Braddock because of "the black issue," which he

defined as the "bitterness" of "whites" toward "the blacks" in

Braddock, Rankin and North Braddock. (117a-26a.)

An important juncture was reached at a State Board meeting in

September 1964. Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 618 (871a). "Although

aware" of the various school districts' "strenuous objections" to

being placed with Braddock and Rankin, at least in the absence of

Churchill or one of the other larger and richer districts in the

area, the Board nonetheless voted to allow Churchill, East Allegheny

and Gateway to stand alone. Id; see 305a, 580a, 698-99a. By rejec

ting the proposals to include these stronger districts in a unit with

some or all of the smaller neighboring districts, the State Board

left itself thereafter "with few options with which to deal" with the

smaller, chronically controversial districts in the area, particularly

Braddock and Rankin. Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 618 (871a).

With Churchill and the other richer districts in the area thus

immunized, Turtle Creek and East Pittsburgh concentrated their

efforts on withdrawing from the Braddock/Rankin unit and forming

their own, sub-4000-pupil district. Following hearings in 1964 and

1965, State Board staff members recommended that the Board approve

the Braddock/Rankin/North Braddock/East Pittsburgh/Turtle Creek unit

because such a combination was "a natural," given reasonable trans-

portational interconnections, the 4000-plus-pupil population and

other favorable factors. Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 817 (765a). The

post-hearing report noted, however, that East Pittsburgh and Turtle

Creek officials were still seeking to have their municipalities

"established as a [separate] unit," in part because of "[t]he non-

white population ... factor." (309a-10a, 699a.)

In 1965, the State Board rejected the recommendation of its

staff and granted the request of Turtle Creek and East Pittsburgh

to be placed in a separate sub-4000 unit. This decision completed

the isolation of Braddock, Rankin and North Braddock from all of the

surrounding municipalities, and the Board merged those districts into

a soon-to-be sub-4000, and predominantly black, unit. Hoots II, 359

F. Supp. at 819-20 (771a). State Board Chairman Dr. Paul Christman

later testified in the district court that State Board members

"recognized" when they took this action "that there was a black-white

factor that was improperly dealt with __ [which] in years to come

... would become even worse than it was at the time." (2702a-03a.)

Although appeals kept the Braddock/Rankin/North Braddock, Brad

dock Hills/Swissvale/Edgewood and Turtle Creek/East Pittsburgh mer

gers from going into effect before Act 299 expired in 1966, those

J Vunits later became effective under Act 299's extension, Act 150.

When Act 150 was passed early in 1968, the County Board resurrected

the State Board's final Act 299 plan. In a hearing on North Braddock's

objection to this plan, County Board President L.W. Earley noted that

Board members were "painfully aware" that "over the years" the other

"surrounding school districts had [successfully] avoid[ed] a school

merger which would include Braddock and Rankin in their school

district and that ... North Braddock was going to be 'left holding

the bag.'" (701a.) Nonetheless, the County Board approved the plan,

and the State Board followed suit. (700a-02a.) As Dr. Christman testi-

13/ The only change the State Board made between 1965 (Act 299) and

1968 (Act 150) was to free Edgewood of inclusion with Swissvale and

Braddock Hills, thereby leaving 0%-black Edgewood intact as a 900-

pupil district, while merging Swissvale and Braddock Hills into a

9%-black, 2300-pupil district. Hoots VI, 510 F. Supp. at 618 (871a-72a).

19

fied, these 1968 occurrences were preordained by the Board's earlier

actions under Act 299 (particularly the approval and immuniza

tion of Churchill, East Allegheny and Gateway) since thereafter the

Board had "no further options." (2688a.)

All of the reorganized districts in central eastern Allegheny

11/County were operating by 1971. The final configuration of cen

tral eastern area districts is shown below, along with the resulting

and continuing pattern of racial segregation among the school districts.

Table (iv): Final Plan (1971, 1975, 1981 Enrollment Figures)

(3233a, 3246a)

GBASD Swissvale Churchill

(Braddock- (Swissv.- (Wilkins- Edgewood T. Creek TOTALRankin-No. Braddock Chalfant (Edge- (T. CreekBraddock) Hills) For.Hills) wood) E. Pitts.)

Year Total % B. Total % B. Total % B. Total % B. Total % B. Total % B.

1971 3735 45% 2275 9% 5773 1% 970 0% 1825 1 % 14,578 12%1975 2668 55% 2051 10% 4892 1% 869 1% 1515 2% 11,995 14%1981 2042 63% 1757 13% 3342 1% 731 2% 1260 2% 9,132 17%

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DETERMINATION THAT PENNSYLVANIA

AUTHORITIES INTENTIONALLY SEGREGATED CENTRAL EASTERN

AREA SCHOOL DISTRICTS AMPLY SUPPORTS ITS CONSTITUTIONAL-

VIOLATION FINDING AND IS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

On December 8, 1971, the district court denied defendants'

motion to dismiss plaintiffs' June 1971 complaint for failure to

j_4/ Immediately after its creation, the State concluded that GBASD was

unable to support itself financially, declared it a "distressed dis

trict" and placed it in receivership. (703a.) GBASD's financial diffi

culties continued throughout its 10-year existence. (2171a, 3232a.)

20

state a cause of action. In its opinion, the district court

described the principal violation issue in the case:

Plaintiffs' Complaint contains allegations that:

(a) In preparing and adopting the school re

organization plans defendants intentionally and

knowingly created racially segregated school

districts....

We have no doubt that the allegations of

deliberate creation of a racially segregated

school district state a cause of action, and

that the remaining allegations are ancillary

and supportive, of this claim. 15/

Hoots I, 334 P. Supp. at 821-22 (958a-59a). After trial the district

court concluded in 1973 that plaintiffs had proved their principal

allegations by establishing that Pennsylvania authorities drew

school district boundaries "based wholly or in part on consideration

of the race of students." Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 822 (777a).

The district court also ruled favorably on some (see pp. 46-50,

16/

infra), but not all, of plaintiffs' "ancillary and supportive"

allegations. See Hoots I, 334 F. Supp. at 822 (959a).

Appellants devote the major part of their briefs to an attack

on the district court's conclusion that Pennsylvania school offi

cials violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. However, in a transparent,effort to draw the Court's

attention away from the crucial issue in the case, appellants

15/ Plaintiffs' complaint alleged that school officials drew

boundary lines in the central eastern area "for racial reasons."

(29a, 35a.) Defendants themselves acknowledged at the violation

trial in 1972 that "the gravamen of [the] complaint goes to the

motivation of state officers, county officers, local officers."

(79a. )

16/ Plaintiffs' complaint included an "economic discrimination"

cause of action. The district court rejected this claim, as did the

Supreme Court in its contemporaneous decision in San Antonio Indepen

dent School District v. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

21

focus their attack entirely on the district court's self-styled

"ancillary and supportive" findings, while virtually ignoring Chief

Judge Weber's principal holding that Pennsylvania officials inten

tionally segregated school districts in central eastern Allegheny

County. As is discussed infra, the district court's ancillary

findings {for example, on "forseeability," see note 24, infra,

and on the Board's application of an "explicit racial classification,"

see PP* 46-49, infra) are appropriate bases for the violation found

by the district court and strongly "supportive" of the court's

principal holding. Nonetheless, whatever the propriety of those

"ancillary" — or, as appellants call them, "alternative" (Brief of

Swissvale at 9-10) — findings, it is absolutely clear as a matter of

both law and fact, that the district court's principal, intentional-

segregation holding is a sufficient basis in itself for the court's

ultimate conclusion that Pennsylvania school authorities violated the

Fourteenth Amendment by creating racially segregated school districts.

A. Relying on Proper Fourteenth Amendment Standards, the

District Court Has Repeatedly Found that Pennsylvania

School Officials Intentionally Segregated GBASD and

Neighboring School Districts on the Basis of Race

1. The district court applied the correct Fourteenth Amendment standard in its

1973 violation decision.

In finding a constitutional violation based on deliberate dis

crimination, the district court applied precisely the same "well-

established" legal standards as the Supreme Court endorsed and

elaborated on in the following passage in Village of Arlington Heights

y- Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977):

22

[The requirement of] proof of racially discrimi

natory intent or purpose is ... well-established

in a variety of contexts.

[This principle] does not require a plain

tiff to prove that the challenged action rested

solely on racially discriminatory purposes.

Rarely can it be said that a legislature or

administrative body operating under a broad

mandate made a decision motivated solely by a

single concern, or even that a particular purpose

was the "dominant" or "primary" one. ... But

racial discrimination is not just another com

peting consideration. When there is a proof that

a discriminatory purpose has been a motivating

factor in the decision, judicial deference is no

longer justified.

Determining whether invidious discriminatory

purpose was a motivating factor demands a sensi

tive 'inquiry into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available. The

impact of the official action— whether it "bears

more heavily on one race than another," Washing

ton v. Davis, 426 U.S. [229,] 242 [(1976)]— may

provide an important starting point. Sometimes

a clear pattern, unexplainable on grounds other

than race, emerges from the effect of the state

action even when the governing legislation appears

neutral on its face....

The historical background of the decision is

one evidentiary source, particularly if it reveals

a series of official actions taken for invidious

purposes. The specific sequence of events leading

up to the challenged decision also may shed some

light on the decisionmaker's purposes.... Depar

tures from the normal procedural sequence also

might afford evidence that improper purposes are

playing a role. Substantive departures too may be

relevant, particularly if the factors usually

considered important by the decisionmaker strongly

favor a decision contrary to the one reached.

Id. at 265-67 (citations and footnotes omitted).

Embodied in this passage from Arlington Heights are both

the legal standard for a violation of the Equal Protection Clause

and a discussion of the "evidentiary source[s]" that courts may

consider in determining whether that standard is met. _Id. at 267.

See Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 279 n.24 (1979)

23

Resident Advisory Board v. Rizzo, 564 F.2d 126, 142-45 (3d Cir.

1977). Hoots II clearly conforms both to that legal standard and

to the prescribed method for assessing if it has been satisfied.

First, in its 1973 decision in Hoots II, the district court

found that "race was a factor" in the formation of school districts

(Finding 60), and it thereupon concluded that a "violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment has occured" because Pennsylvania "public

school authorites ... made [segregative] educational policy deci

sions:" (i) "based wholly or in part on considerations of the race

of students" (Conclusion 2), (ii) "because of community sentiment"

favoring "segregated schools" (Conclusion 3), and (iii) in order to

"conform[J to and buil[d] upon patterns of residential segregation"

(Conclusion 5). Hoots II, 359 F. Supp. at 821-23 (774a, 777-78a).

These findings and conclusions embody precisely the determination

that the Equal Protection Clause requires the courts to make: that

"a discriminatory purpose has been a [not necessarily "the 'dominant'

or 'primary'"] motivating factor in the decision," Arlington Heights,

429 U.S. at 265 (emphasis added), and that the decision was made

"'because o f ... its adverse effects upon [blacks]." Personnel

Administrator, 442 U.S. at 279.

Second, not only in Hoots II in 1973, but also in its thorough

reexamination of the evidence in Hoots VI in 1981, the district

court clearly premised the conclusion that race was a motivating

factor on "a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and

direct evidence as [was] available," Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

266, including at least eight proper and convincing "evidentiary

sources," with regard to which the district court made the findings

set out below:

24

(a) "The State and County Boards in devising the plan of

organization of administrative units for the central

eastern portion of Allegheny County were influenced

by the desires of the surrounding municipalities to

avoid being placed in a school district with Braddock

and Rankin because of the high concentration of blacks

within those two municipalities." Hoots II, 359 F.

Supp. at 821 (774a), reaffirmed in Hoots VI, 510 F.Supp. at 619 (873a).

The courts, this one included, have long and consistently

recognized official conformance to the racially motivated desires

of constituents as sufficient in itself to prove an invidious racial

motivation. E.q., Arthur v. Nyguist, 573 F.2d 134, 144 (2d Cir.

1978) (finding intentional discrimination because the school board

was "strongly influenced by residents who opposed integrated school