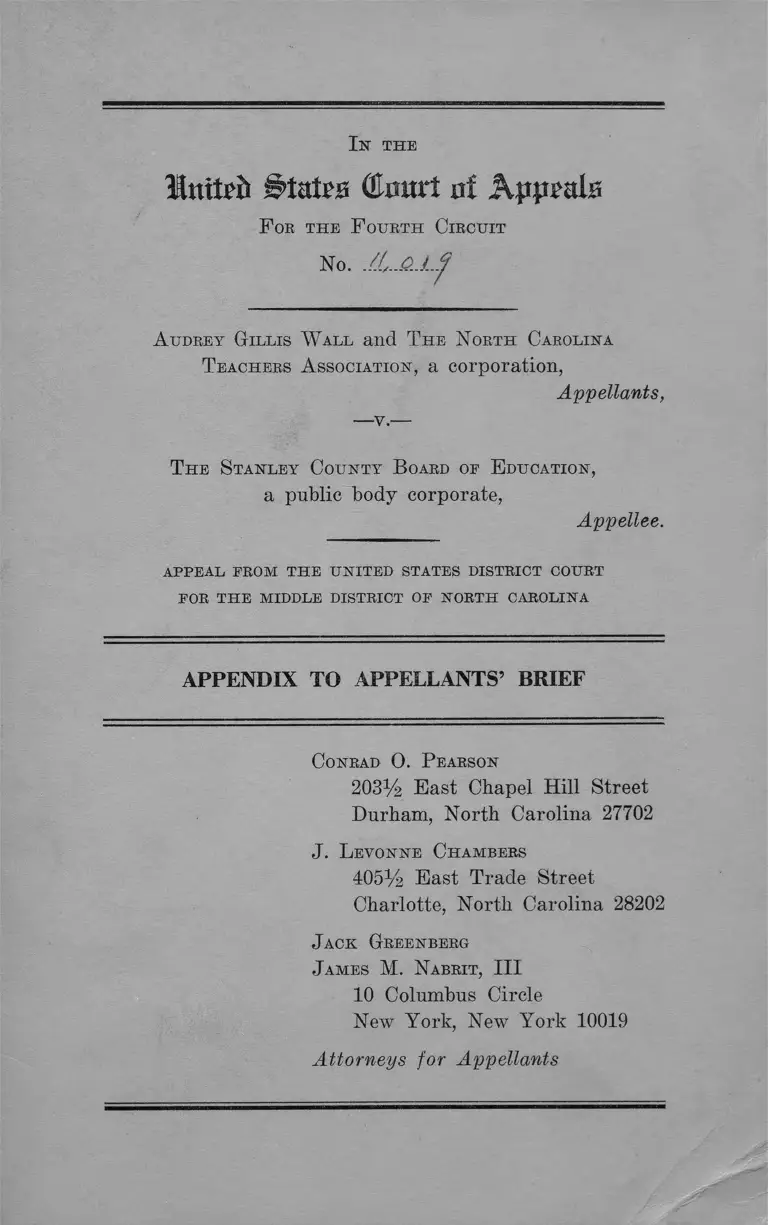

Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

November 9, 1965 - September 22, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1965. c0a5e259-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c44cdf0-6530-4166-b477-0ceb6b12f5e2/wall-v-stanley-county-north-carolina-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed December 07, 2025.

Copied!

I n t h e

Intteii States (ttnurt a! Appeals

F or t h e F ou rth C ir c u it

No. IL .C .l J

A udrey G illis W a l l and T h e N orth C arolina

T eachers A ssociation , a corporation,

Appellants,

— v .—

T h e S ta n le y C o u n ty B oard oe E du cation ,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

J . L evonne C h am bers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack G r e e n b e r g

J am es M. N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Motion for Preliminary Injunction................................. 7a

Answers and Motions of Defendant ........................... 8a

Defendant’s Exhibit “A” ................................................ 19a

Response....................................................................... - 31a

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference ......................... 35a

Motion ................................................................................ 37a

Order Dated November 9, 1965 Denying Defendant’s

motions to Dismiss and for Summary Judgment

and Denying Plaintiffs’ Motion for a preliminary

injunction ................................................................... 39a

Order Dated November 9, 1965 granting plaintiffs’

motion to amend complaint and other pleadings to

show correct spelling of Stanly County Board of

Education and Stanly County.................................... 40a

Motion of Leave to Amend Complaint ...................... 41a

Memorandum ................................................................. 42a

Order on Final Pretrial Conference .......................... 44a

Order Dated February 9, 1966 ........................................ 51a

Memorandum ........................................................ 52a

PAGE

Complaint ........................................................................... la

11

Stipulation ...................................................................... 53a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion 54a

Judgment, Entered September 26, 1966 .................. 94a

Interrogatories ............................................. -................ 95a

Answers to Interrogatories ......................................... 97a

Schedule I ...................................................................... 100a

Schedule II .................................................................... 102a

Schedule III (a) ............................................................ 104a

Schedule 111(b) ............................................................ 118a

Schedule I V .................................................................... 132a

Schedule V ...................................................................... 140a

Schedule V I .................................................................... 141a

Interrogatories of Defendant ..................................... 154a

Answers to Interrogatories ......................................... 156a

Teacher Allotmens for 1965-66 ..................................... 161a

List of New Teachers for 1965-66 .............................. 175a

List of Teachers Not Returning for 1965-66 .............. 179a

List of Schools by Race 1965-66 .................................. 180a

PAGE

I ll

List of All Teachers 1965-66 ......................................... 181a

Letter of Luther A. Adams to Agricultural and Tech

nical College of Greensboro ................................... - 200a

Minutes of Stanly County Board of Education,

June 7, 1965 and July 7, 1965 ................................. 201a

Form of Contract for Instructional Service.............. 212a

Letter of Robert E. McLendon to Audrey G. Wall .... 214a

Minutes of Stanly County Board of Education,

April 15, 1966 and Resolution of Teacher Hiring

Policies ........................................................................ 216a

Deposition of G. L. Hines............................................. 233a

Deposition of Robert McLendon................................. 259a

Deposition of Luther A. Adams ............. 287a

Deposition of Reece B. McSwain................................. 351a

Deposition of Audrey Gillis Wall .............................. 357a

Transcript of Proceedings, April 26, 1966

Proceedings ............................................................ 396a

Luther Adams

Direct ...................................................... 403a

Colloquy .................................................................. 439a

Audrey Gillis Wall

Direct ...................................................... 461a

PAGE

IV

Transcript of Proceedings, April 27, 1966

Proceedings ............................................................. 4^ a

E. Edmund Eentter, Jr.

Direct ....................................................... 417a.

Colloquy .................................................................. 483a

Notice of Appeal............................................................ 51 â

PAGE

I n- t h e

United States Siatrirt fflnnrt

F or t h e M iddle D istr ic t oe N o rth C aro lin a

S a lsib u r y D ivisio n

Civil Action No. C-140-S-65

A u drey G illis W a l l an d the N o rth C arolin a

T each ers A ssociation , a c o rp o ra t io n ,

Plaintiffs,

— Y .----

The S t a n l e y C o u n t y B oard of E d u c a tio n , a public

body corporate of Stanley County, North Carolina,

Defendant.

Complaint

I

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, U. S. C. §1343(3), this being a suit in equity au

thorized by law, Title 42, U. S. C. §1983, to be commenced

by any citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to redress the deprivation under

color of statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage

of a State of rights, privileges and immunities secured

by the Constitution and laws of the United States. The

rights, privileges and immunities sought herein to be re

dressed are those secured by the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Constitution of the United States.

2a

II

This is a proceeding for an injunction, enjoining the

Stanley County Board of Education, its members and

those acting in concert with them or at their direction

from continuing the policy, practice, custom and usage of

discriminating against the individual plaintiff, members

of plaintiff organization and other Negro citizens of Stanley

County, North Carolina, because of race or color, and from

hiring, assigning, or dismissing or refusing to hire teachers

and other school personnel in the Stanley County School

System on the basis of race or color, and for other relief

as hereinafter more fully appears.

III

The individual plaintiff in this case is a Negro citizen

of the United States and State of North Carolina, resid

ing in Stanley County, North Carolina. Said plaintiff pos

sesses the necessary qualifications for teaching and has

taught in the Stanley County School System for the past

thirteen years but has been dismissed and refused re

employment solely because of her race. Said plaintiff

brings this action on her own behalf and on behalf of all

other Negro teachers and school personnel in the Stanley

County School System, who are similarly situated and

affected by the policy, practice, custom and usage com

plained of herein. The members of the class on behalf

of whom individual plaintiff sue are so numerous as to

make it impracticable to bring them all individually before

this Court, but there are common questions of law and

fact involved, common grievances arising out of common

wrongs and common relief is sought for each member of

Complaint

3a

the class. The plaintiff fairly and adequately represents

the interests of the class.

The plaintiff North Carolina Teachers Association is a

professional teachers association, organized as a private,

non-profit, membership corporation pursuant to the laws

of the State of North Carolina, with authority to sue and

be sued in its corporate name. The Association has a

membership of approximately 12,500, most of whom are

Negro teachers, teaching in the public schools of North

Carolina, including the Stanley County Public Schools.

One of the objectives of the Association is to support the

decisions of the United States Supreme Court on segre

gation in public education and to work for the assignment

of students to classes and teachers and other professional

personnel to professional duties within the public school

systems without regard to race, and to work against dis

crimination in the selection of such professional personnel.

Plaintiff Association is the medium by which its members

are enabled to express their views and to take action with

respect to controversial issues relating to racial discrimina

tion. The Association asserts here the right of its members

not to be hired, assigned or dismissed on the basis of their

race or color.

IV

The defendant in this case is the Stanley County Board

of Education, a public body corporate organized and ex

isting under the laws of the State of North Carolina. The

defendant Board maintains and generally supervises the

public schools of Stanley County, North Carolina, acting

pursuant to the direction and authority contained in the

State’s constitutional and statutory provisions. As such,

the Board is an arm of the State of North Carolina, en

forcing and exercising State laws and policies. Among its

Complaint

4a

duties, defendant assigns students to the various public

schools and hires, assigns and dismisses teachers and pro

fessional school personnel to duties in the Stanley County

School System.

Y

Defendant, acting under color of the authority vested in

it by the laws of the State of North Carolina, has pursued

and is presently pursuing a policy, practice, custom and

usage of operating the public school system of Stanley

County on a basis that discriminates against plaintiffs be

cause of race or color, to wit:

1. Defendant has in the past and presently hires and

assigns all teachers and professional school personnel on

the basis of race and color. Negro teachers and profes

sional personnel are assigned to schools reserved for

Negro students.

2. Effective with the beginning of the 1965-66 school

year, defendant has adopted a plan for the assignment of

students to the various schools which permits students to

indicate the school they desire to attend. Under defen

dant’s plan, approximately 100 Negro students have re

quested reassignment from the formerly all-Negro schools

which they formerly attended to previously all-white

schools and pursuant to defendant’s policy and practice

of making racial assignments of teachers and professional

school personnel, defendant has dismissed individual plain

tiff herein and other Negro teachers, in anticipation of

the decrease in enrollment in the formerly all-Negro

schools, solely on the basis of their race and color. Defen

dant has continued to hire white teachers and school per

sonnel to fill positions in all-white or formerly all-white

schools and refused to consider the application of in

Complaint

5a

dividual plaintiff solely because of her race. Defendant

refuses to eliminate its racial policies regarding teachers

and professional personnel and continues to hire, assign

and dismiss such personnel solely on the basis of their

race and color.

VI

Plaintiffs have made reasonable efforts to communicate

to defendant their dissatisfaction with defendant’s racially

discriminatory practices, but without effecting any change.

Further efforts by plaintiffs would prove fruitless in pro

viding the relief which plaintiffs seek in view of defendant’s

continued avowed adherence to the racially discriminatory

practices set forth herein.

VII

Individual plaintiff and members of plaintiff Associa

tion are irreparably injured by the acts of defendant com

plained of herein. The continued racially discriminatory

practices of defendant in hiring, assigning and dismissing

teachers and professional school personnel violate the

rights of individual plaintiff and members of plaintiff

Association secured to them by the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, and Title 42,

U. S. C. §§1981, 1982 and 1983.

The injury which plaintiffs suffer as a result of the

action of the defendant is and will continue to be irrepara

ble until enjoined by this Court. Any other relief to which

plaintiffs could be remitted would be attended by such

uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial relief,

would involve a multiplicity of suits, cause further ir

reparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and in

convenience to the plaintiffs.

Complaint

6a

W h e r e f o r e , plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy hear

ing of the action according to law and, after such hearing,

enter a preliminary and permanent decree, enjoining the

defendant, its agents, employees, and successors and all

persons in active concert and participation with them from

hiring, assigning and dismissing teachers and professional

school personnel on the basis of race and color, from dis

missing, releasing, refusing to hire or assign individual

plaintiff and other Negro teachers and professional school

personnel on the basis of race or color and from continuing

any other practice, policy, custom or usage on the basis

of race or color.

Plaintiffs further pray that this Court retain jurisdic

tion of this cause pending full and complete compliance

by the defendant with the order of the Court, that the

Court will allow them their costs herein, reasonable counsel

fees and grant such other, further and additional or al

ternative relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable

and just.

Respectfully submitted,

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J . L e vo n n e C h a m b e r s

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

D e rrick A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Complaint

7a

Plaintiffs, upon their complaint filed in this case, move

the Court for a preliminary injunction pending final hear

ing and determination of this case, enjoining the defendant,

its agents, servants, employees, successors, and all persons

in active concert and participation with them for dismiss

ing, refusing to hire or assign Negro teachers, now teach

ing in the Stanley County School System, on the basis of

race or color and from hiring, assigning and dismissing

teachers and professional school personnel on the basis of

race.

Plaintiffs further pray that the Court will retain juris

diction of this cause pending full and complete compliance

by the defendant with the order of the Court, that the

Court will allow them their costs herein, reasonable at

torney fees, and grant such other, further additional or

alternative relief as may appear to the Court to be equi

table and just.

Respectfully submitted,

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J . L e vo n n e C h a m b e r s

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J a c k G reenberg

D e r rick A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

8a

The Defendant, Answering the Complaint of the Plain

tiffs, and Requesting That This Answer Be Used as

an Affidavit in Support of the Motions Herein Alleged

and as Notice of Said Motions, for Its Motions and

Answer Alleges:

F irst D efen se

This action should be dismissed for that:

a) The Complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted.

b) Under the allegations of the Complaint Plaintiffs

would be entitled to no relief under any state or set of

facts which could be proved in support of its claim or

allegations.

c) Under the allegations of the Complaint Plaintiffs

have no possible right to relief on any theory, under any

discernible circumstances and their is an utter lack of law

and alleged facts.

d) For that the circumstances upon which Plaintiffs

attempt to base their cause of action are governed by

State law under Federal Rules of Decision Statute (28

USCA 1652) and, therefore, Defendant did not owe Plain

tiffs any statutory or other legal duty.

e) The Complaint discloses that Defendant acted within

the scope of its legal, lawful rights and pursuant to valid

State Statutes, and acts of the Defendant could not amount

to a violation of any rights of the Plaintiffs.

f) The Plaintiffs have no legal, statutory or constitu

tional right to public employment and cannot be deprived

of any rights related thereto.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

9a

g) The Defendant has never had any legal or con

tractual relationship with the Corporate Plaintiff, and

therefore the Corporate Plaintiff is not a proper party

to maintain this action, and therefore for a defect of Party

Plaintiff as to the Corporate Plaintiff this action should

be dismissed.

S econd D efen se

That for the reasons set forth in the First Defense, the

Defendant specifically moves that this alleged cause of

action be dismissed.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

T h ird D efen se

The Defendant adopts and realleges the matters and

things set forth in the First Defense and further alleges

that the contracts of the teachers for the benefit of whom

this action is allegedly instituted had expired and termi

nated in accordance with valid statutory law of the State of

North Carolina, and therefore the Defendant moves the

Court for judgment upon the pleadings in favor of the

Defendant and to the end that Plaintiffs’ alleged claim

and cause of action be dismissed.

F ou rth D efense

The defendant, by its Attorneys of Record, hereby move

the Court to enter summary judgment for the Defendant,

in accordance with the provisions of Rule 56(b) and (c) of

the Rules of Civil Procedure, on the ground that the plead

ings, answer of the Defendant used as an affidavit, and

other exhibits, show that the Defendant is entitled to

judgment as a matter of law. That Defendant will bring

this motion on for hearing before the District Judge of the

10a

United States Court for the Middle District of North Caro

lina at the Federal Courtroom in Salisbury, North Caro

lina, or at such other place as this proceeding or action is

set for hearing, or at such time as the Court may direct.

The Defendant alleges in support of said motion for sum

mary judgment the following:

a) The Defendant adopts and realleges the matters set

forth in the previous defense of this Answer.

b) That there are no genuine issues of material facts

existing which are determinative of any duty or right which

the Defendant owes the Plaintiffs, and as a matter of law

Defendant is entitled to a summary judgment.

c) That there are no genuine, relevant and material facts

as to deprivation of any constitutional rights of the teach

ers in whose behalf the Plaintiffs attempt to maintain this

action for that the circumstances upon which Plaintiffs

attempt to base their alleged claim or cause of action are

governed by State law, and, the Defendant having acted

within the scope of its legal rights according to State law

and State Statutes, no cause of action inures to the Plain

tiffs in behalf of said teachers.

d) That the Plaintiff Audrey Grillis Wall was formerly

employed by the Defendant to teach in the public schools

administered by the Defendant under a written legal con

tract which was entered into on a yearly basis as related

to the school year, and said contract expired or terminated

under the statutes and laws of the State of North Carolina,

and there was no legal duty on the part of the Defendant

Board of Education and its officers and agents to employ

said Plaintiff for another or prospective year, and said

Plaintiff had never had any right of employment or re

Answer and Motions of Defendant

11a

employment in the public schools of the Defendant nor did

any member of the Corporate Plaintiff organization have

any such right. That under the Rules of Decision Statute

enacted by Congress it is the duty of the Court to enforce

the State law which governs the rights and duties of the

parties.

e) That the Defendant, the Stanly County Board of Ed

ucation, is an agent of the State and an instrumentality of

government, as well as a body politic, and is, therefore,

not subject to the provisions of T itle VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, and therefore the Defendant is immune from

any action or proceeding such as this claim of the Plain

tiffs on behalf of the individual plaintiff and the corperate

plaintiff in behalf of its teacher members; and the Defend

ant in these circumstances owes the Plaintiff and the said

teacher members no duty and is therefore not liable to the

individual Plaintiff the Corporate Plaintiff, or any other

school teacher who claims to have an interest in this action.

F if t h D efen se

The Plaintiffs having prayed for equitable relief have

failed to show a failure on the part of the Defendant to

perform a clear, legal duty so as to provide grounds for

equitable relief and a valid basis for a proper decree in

equity; that the teachers in whose behalf the Plaintiffs at

tempt to maintain this action have no valid and enforceable

right to public employment, their contracts having been

for a definite period of time and having expired, and said

teachers are not entitled to any exceptional or superior

prerogative and privileges because they happen to be mem

bers of the Negro race; that the rights and privileges as

to employment or re-employment of said public school

Answer and Motions of Defendant

12a

teachers are governed by the laws of the State of North

Carolina and these laws have been observed and complied

with by the Defendant; that the pnpils in the schools of

said teachers were assigned to other public schools in order

to comply with T itle VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and there is therefore no equitable basis for the extraor

dinary relief of injunction or otherwise; that the laws of

the State of North Carolina govern and control in this

case under the Rules of Decision Statute, and Plaintiff is

not entitled to any form of equitable relief.

S ix t h D efense

That the Defendant has a constitutional right to enter

into contracts of employment with public school teachers,

including the teachers herein affected and has a constitu

tional right in its judgment and discretion to refuse to

reemploy these teachers or any other teachers in its public

school system; that any attempt on the part of the Plain

tiffs to force or compel the Defendant to again enter into

a new contract or to re-employ the teachers herein con

cerned is a violation of the constitutional rights of the De

fendant, is a violation of the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution and is therefore

in violation of the equal protection and due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment and further is in violation

of the Law of the Land clause as set forth in Article I,

Section 17, of the Constitution of North Carolina and fur

ther is an impairment of the Defendant’s right to con

tract ; that such constitutional infringement of the Defend

ant’s constitutional rights and such deprivation of the

Defendant’s privileges and immunities are here alleged as

a bar to the Plaintiffs’ right to recover in this action.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

13a

Answer and Motions of Defendant

S e v e n t h D efen se

That the individual Plaintiff Audrey Gfillis Wall was not

employed as a teacher in the public school system under the

jurisdiction of the Defendant for the school year 1965-1966

for the reason that the principal of the school in which

she taught for the school year 1964-1965 refused to recom

mend her reemployment on account of her incompetency,

lack of qualification, and past adverse record of employ

ment in said school system, and because no white or Negro

principal of any of the public schools of the Defendant

wanted or would accept her (except by compulsion on the

part of the Board of Education) on account of her past

record of insubordination and absenteeism in the schools

in which she had previously taught and her general reputa

tion for being a ‘Trouble maker” in the schools in which

she had taught.

E ig h t h D efense

The Defendant alleges and says that as an agency and

political subdivision of the State of North Carolina it is not

as such subject to suit without its consent, and the Court

is without jurisdiction to hear and determine the pur

ported claim for relief asserted against it as an entity and

“an arm of the State of North Carolina.”

N in t h D efen se

T h e D e fe n d a n t S pe c if ic a l l y A n sw e r in g t h e V arious

P aragraphs of th e C o m pl a in t for its A n sw e r A lleges :

1) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 1 of the

Complaint, it is admitted that the Federal Statutes desig

nated in said paragraph are set forth in the United States

Code, but it is denied that they have any application to the

14a

Defendant or that any constitutional rights of the Plain

tiffs or the said teachers have been violated or abridged or

that any unconstitutional discrimination has been enforced

or administered by the Defendant; except as admitted

herein, all allegations of Paragraph 1 are untrue and are

denied.

2) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 2 of the

Complaint, it is denied that the Plaintiffs or either of

them are entitled to any preliminary or permanent injunc

tion or that the Defendant, or any of its members or any

one acting in concert with them or at their direction or

otherwise, has engaged or is continuing to engage in a pol

icy, practice, custom, and usage of discriminating against

the individual plaintiff members of the plaintiff organiza

tion or other Negro citizens of Stanly County, North Caro

lina, because of race or color, or that they are hiring, as

signing, dismissing, or refusing to hire teachers and other

school personnel in the Stanly County School system on

the basis of race or color, and that all the allegations of

said paragraph are untrue and are denied.

3) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 2 of the

Complaint, it is admitted that the individual Plaintiff is a

Negro citizen of the United States, and of North Carolina,

residing in Stanly County, North Carolina, and that she has

taught in the Stanly County School system for eleven (11)

years; further answering said paragraph, the Defendant

affirmatively alleges that the individual plaintiff was not

re-employed in its school system for the year 1965-1966

because of the lack of qualification only, as has herein

before in this answer been set forth in detail. Further an

swering the allegations of said paragraph, the Defendant

says it does not have sufficient knowledge or information

Answer and Motions of Defendant

15a

to form a belief relative to those matters in said paragraph

asserting the nature and purpose of the North Carolina

Teachers Association and therefore denies the same.

Except as herein admitted, all the allegations of said

paragraph are denied.

4) Each and every allegation contained in Paragraph 4

of the Complaint are admitted, and, further affirmatively

answering the said allegations, the Stanly County Board of

Education alleges and says that as an agency and political

subdivision of the State of North Carolina it is not as

such subject to suit without its consent, and that the Court

is without jurisdiction to hear and determine the pur

ported claim for relief asserted against it as an entity and

“an arm of the State of North Carolina.”

5) The allegations of Paragraph 5 of the Complaint and

sub-paragraphs 1 through 4, inclusive, are untrue and de

nied, except to the extent that an admission to portions

thereof may be made in the further affirmative answer to

said allegations contained herein.

Further affirmatively answering allegations of Para

graph 5 of the Complaint, the Stanly County Board of

Education alleges that it submitted to the United States

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare a com

prehensive plan, prepared and designed in good faith to

comply with all lawful requirements of the Acts of Con

gress and judicial decisions and interpretations relating

thereto as they affect the desegregation of the public

schools over which the Stanly County Board of Education

has jurisdiction, which plan was adopted by the Board on

April 26, 1965, revised and re-adopted by the Board after

revision on June 7, 1965; that said plan was approved by

the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, by let

Answer and Motions of Defendant

16a

ter to Luther A. Adams, Superintendent of the Stanly

County School Administrative Unit, on June 18, 1965,

under signature of Francis Keppel, United States Com

missioner of Education; that said plan has been imple

mented in good faith by the Board of Education to the ex

tent possible at this time; that a copy of said plan, marked

“Exhibit A” is attached hereto and requested to be made

a part of this paragraph as if fully set forth herein.

Further answering allegations of said paragraph, the

Defendant alleges that it has not engaged in any discrimi

natory practices with reference to the Plaintiffs or any

teachers now employed or formerly employed in its school

system, and that the action taken hy it was done and per

formed in the effort to comply with T it l e VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. It is specifically denied that the in

dividual plaintiff or any other teacher affected by com

pliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was dismissed

because of race or were in fact dismissed at all. That the

Defendant did not reemploy the individual plaintiff be

cause her contract had expired, because she was unqualified

and incompetent, and the Board had no need for her; that

the failure to re-employ public school teachers because of

transfer of students and consolidation of schools or any

other cause bringing about a reduction in the number of

teachers allotted to the schools has happened throughout

the State for many years and has affected both white and

Negro teachers.

6) The allegations of paragraph 6 of the Complaint are

denied.

7) The allegations of paragraph 7 of the Complaint are

denied.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

17a

W h erefore , having fully answered the Plaintiffs’ Com

plaint, the Defendant prays that the Court hold, rule,

adjudge, and decree as follows:

1) That the Court not consider this Answer to be a sub

mission to the jurisdiction of the Court.

2) That the Court grant the motions of the Defendant

to dismiss this action, for judgment on the pleadings and

the motion that the Court enter a summary judgment in

favor of the Defendant.

3) That the Court hold that the Complaint does not state

a claim upon which relief can be granted, and that the

Court has no jurisdiction over the Defendant and the sub

ject matter of this action.

4) That the Corporate Plaintiff has no legal capacity or

status to maintain this action.

5) That there is not sufficient equitable basis or facts

alleged for the granting of a permanent injunction of a

mandatory nature or of any other nature.

6) That this verified answer be treated as an affidavit for

the purpose of the motions alleged herein and in passing

upon the injunctive relief demanded by the Plaintiffs.

7) That no costs or fees be awarded or charged against

the Defendant.

8) That the costs of this action, together with reasonable

attorney fees, incurred by the Board of Education herein,

be taxed to the Plaintiffs; that the Plaintiffs be required

to file a bond or other security in order to secure the

same; and

Answer and Motions of Defendant

18a

9) That the Defendant have such other and further re

lief as to the Court may seem just and proper in the

premises.

Respectfully submitted this 2 day of September, 1965.

S taton P . W il l ia m s ,

Albemarle, N. C.

H e n r y C. D oby , Jr.,

Albemarle, N. C.

Attorneys for the Defendant.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

N o rth C aro lin a

S t a n l y C o u n t y

R eece B. M cS w a in , being duly sworn, says:

That he is Chairman of the Stanly County Board of Ed

ucation, the Defendant in this case, and that he verifies

this Answer in behalf of said Defendant; that he has read

the foregoing Answer and the same is true to his own

knowledge and belief, except as to the matters and things

therein stated upon information and belief, and as to those

matters and things he believes it to be true.

R eece B. M cS w a in

Chairman of the Stanly County

Board of Education

Sworn and subscribed to before

me on this the 1st day of September, 1965.

M argaret M . W il l ia m s

Notary Public

19a

C omes N o w , the Stanly County Board of Education,

a body politic and the governing authority for the opera

tion of the public schools in the Stanly County Admin

istrative Unit, Stanly County, North Carolina, under the

provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

and submits for approval as compliance with said provi

sions and requirements of said Act the plan as follows:

A rticle I

G e n eral P rovisions an d C o m plia n c e I n f o r m a tio n

Section 1. The Stanly County Administrative Unit em

braces all of the County of Stanly other than that portion

of said County that lies within the boundaries of the

Albemarle City School Administrative Unit.

Section 2. The territory of the Stanly County Admin

istrative Unit comprises one (1) school district.

Section 3. Racial Characteristics of School Population

(a) There are approximately 6,934 children of school age

residing in the district, 5,870 of whom are white, and

1,064 of whom are Negro. There are no other races in

the district.

(b) The number of Negroes presently attending pre

dominantly white schools is two (2).

(c) The number of white children attending predom

inantly Negro schools is none (0).

(d) The number of Negro pupils presently attending

classes with white pupils in the public schools of the dis

trict by grade is: first grade, none; second grade, none;

Defendant’s Exhibit “A”

20a

third grade, none; fourth grade, none; fifth grade, none;

sixth grade, none; seventh grade, none; eighth grade, none;

ninth grade, none; tenth grade, none; eleventh grade, none;

twelfth grade, two.

(e) The number of pupils attending public schools out

side the district on a tuition paid basis is: (i.e., tuition

paid by the parent or guardian with no contribution of

school tax funds from Stanly County) white, 278; Negro,

none; Other, none. The situation is this: Approximately

150 Negro High School children residing in the County

are presently assigned to the Albemarle City Administra

tive Unit. Under the exercise of the Freedom of Choice

Plan approximately two-thirds (% ) of the Negro students

assigned to the Albemarle Administrative Unit elected to

attend white schools in the Stanly County Administrative

Unit. At this point it is proposed to let the remaining

one-third (y3) continue to attend school in the City Ad

ministrative Unit. White children residing in the County

Administrative District are permitted to attend the Al

bemarle City Administrative Unit upon payment of a

tuition. This tuition is paid by the parents of the child

and no tax funds are involved.

(f) No pupils residing in the district presently attend

private schools on a tuition grant basis.

Section 4. Racial Characteristics of Schools of the

District

(a) The number of elementary schools (grades 1-8) in

which the pupils enrolled are all white is eleven (11);

all Negro, three (3); integrated, none.

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

21a

(b) There are no junior high schools operated in the

district.

(c) The number of high schools (grades 9-12) in which

the pupils enrolled are all white is two (2), all Negro,

one (1); integrated, one (1).

Section 5. Racial Characteristics of Teaching and

Administrative Staff

(a) By race, the number of teachers in the district who

are white is 237; Negro, 33; other, none.

(b) By race, the number of non-teaching staff members is

(clerical help, etc.) white, 124; Negro, 19; other, none.

(c) The number of elementary schools having teachers

who are all white is eleven (11); all Negro, three (3);

integrated, none.

(d) No junior high schools are operated in the district.

(e) The number of high schools having teachers who

are all white is three (3); all Negro, one (1); integrated,

none.

Section 6. School Bus Routes and Practices

A dual bus system is operated in the district; that is,

Negroes are assigned to and are transported in busses

carrying only Negroes; white children are assigned to

and transported on busses carrying only whites. The

children board the busses from pick-up stations along the

route. No child has to go more than one-half (Mj) mile to

board a bus, and virtually all pick-ups are made along the

bus route on a house to house basis.

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

22a

A rticle II

P l a n for C o m plia n c e

WITH

T it l e VI of t h e C iv il R ig h t s A ct of 1964

ADOPTED BY

T h e S t a n l y C o u n t y B oard of E d u cation

S t a n l y C o u n t y S ch ool A d m in ist r a t iv e U n it

A lb e m a r le , S t a n l y C o u n t y , N o rth C aro lin a

ON

J u n e 7, 1965

Section 1. Present Patterns, Practices, Policies and

Procedures Governing School Organization

and Pupil Assignment

(a) The schools by name, grades taught, enrollment by

race, and teaching staff by race are as follows:

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

S c h o o l

G ra d es

Taught

E n r o ll m e n t

b y ra ce

T e a c h in g

S t a ff

b y ra ce

Millingport 1-8 266 W 9 W

Richfield 1-8 246 W 9 W

New London 1-8 531W 17 W

Badin 1-8 322 W 11W

Norwood 1-8 698 W 25 W

Aquadale 1-8 324 W 12 W

Endy 1-8 266 W 10W

Oakboro 1-8 484 W 17 W

Stanfield 1-8 315 W 11 W

Ridgecrest 1-8 165 W 6 W

Locust 1-8 337 W 12 W

North Stanly 9-12 697 W 2 N 33 W

South Stanly 9-12 523 W 30 W

23a

Defendant’s Exhibit ‘ ‘‘A ”

S c h o o l

G ra d es

T a u g h t

E n r o llm e n t

b y ra ce

T e a c h in g

S t a f f

b y ra ce

West Stanly 9-12 672 W 35 W

West Badin 9-12 151 N 9 N

West Badin 1-8 305 N ION

South Oakboro 1-8 125 N 4 N

Lake View 1-8 261 N ION

Kingsville (in 9-12 150 N

Albemarle City 1-8 69 N

Administrative

Unit-pupils

assigned by

agreement)

(b) Presently, pupil assignments to the respective

schools are made pursuant to the provisions of Article 21,

Chapter 115, of the General Statutes of North Carolina,

with the right of re-assignment of any child by request.

Over the years white children have been assigned to all

white schools, and Negro children have been assigned to

all Negro schools. All requests for re-assignment made

for the school year 1964-65 were granted by the Board

of Education.

(c) Presently, 5,002 pupils are being transported by bus

to the respective schools. A dual transportation system

is used, and Negro children are assigned to busses trans

porting only Negroes, and white children are assigned to

busses transporting only white children, under the direc

tion of the County Superintendent and the principals of

the respective schools, pursuant to State Law.

(d) Staff personnel of the respective schools are not

presently assigned on an integrated basis, but county-wide

24a

staff meetings are held and conducted on a completely

integrated basis. This means that teachers’ meetings, prin

cipals’ meetings, supervisors’ meetings, and other admin

istrative meetings, including committee meetings etc., work

entirely on an integrated basis.

(e) The three (3) all-Negro schools operated in the

County Unit are located in the geographical centers of

areas densely populated with Negroes. These areas are

Negro communities that have developed over the years.

A r tic l e III

P roposed P olicies G overn in g E n r o l l m e n t an d A ssig n m e n t

an d R e- A ssig n m e n t op P u p il s to S chools in t h e

S ch ool A d m in ist r a t iv e U n it

Section 1. Commencing with the 1965-66 school year and

each year thereafter, children entitled to attend the schools

in the Administrative Unit will be given complete freedom

of choice as to the school to be attended, and to this end:

(a) Parents of all children entering the school system

for the first time and parents of all children in all grades

already enrolled in the school system will he given full

opportunity to indicate their choice of schools, before the

Board of Education makes any assignment of pupils.

Teachers, principals, and other school personnel are

not permitted to advise, recommend, or otherwise influence

the decision; nor will school personnel either favor or

penalize children because of the choice made.

(b) Should more requests be submitted for a particular

school or facility than can be honored because of over

crowding of facilities, preference will be accorded solely

on the basis of proximity of the residence of the child to

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

25a

the school chosen. No request will be denied for any reason

other than over-crowding. The Board of Education will

honor all “Freedom of Choice” requests and will make

facilities available where necessary.

(c) Parents whose original requests for assignment can

not be granted, will be given an opportunity to indicate a

second choice, in a like manner as they would have indicated

a first choice.

(d) Under the freedom of choice plan, it is mandatory

for parents to express a choice of school or schools to

which they wish their child or children to be assigned

without regard to race, color, or national origin.

A rticle IV

P rocedures for A d m in ist e r in g t h e P u p il A ssig n m e n t

P o licy for 1965-66 and S u b seq u en t Y ears

Section 1. As stated in Article III, the pupil assignment

policy becomes operative for the school year 1965-66.

Section 2. Pre-Registration of Pupils Planning to

Enroll in First Grade

(a) Beginning .............................. 1965 (a date at least

four weeks before pre-registration is to commence) and

once a week for three successive weeks the announcement

below shall be conspicuously published in the Stanly News

and Press, Albemarle, N. C.:

“ P re-R egistration of F irst G rade P u p il s for F a l l 1965

“Pre-registration of pupils planning to enroll in first

grade in Stanly County Schools for the fall 1965 semester

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

will take place for a period of .............. days, from

............................ . 1965 through ........................ . 1965.

26a

Under policies adopted by the Stanly County Board of

Education, parents or guardians may register pupils dur

ing this period at the school of their choice. All assign

ments heretofore made with respect to such pupils shall

be rescinded. At the time of pre-registration a choice must

be expressed. No child may attend school until a choice

has been made. In the event of over crowding, preference

will be given without regard to race, color, or national

origin to those choosing the school who reside closest to it.

Those whose choices are rejected because of over crowding

will be notified and permitted to make an effective choice

of another school, without regard to race, color or national

origin.

The choice is granted to the parent or guardian and the

child. Teachers, principals and other school personnel

are not permitted to advise, recommend or otherwise

influence the decision. Nor will school personnel either

favor or penalize children because of the choice made.

Children not pre-registered by the assigned date may

be registered at the school of their choice on ..........................

(a date to be set) immediately prior to the opening of

schools for the fall 1965 semester, but first preference in

choice of schools will be given to those who pre-registered

at the appointed date and time.

(b) Annually after 1965, similar practices will be fol

lowed with respect to registering and enrolling pupils for

the first time in the first grade.

Section 3. Notice to Parents of Pupils Moving into the

County School District from outside the

District

“ The Office of the Superintendent will furnish, upon

application, to parents or guardians of pupils moving into

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

27a

the school district, forms and instructions necessary to

complete registration and enrollment in the School of their

choice.”

Section 4. Notice to Parents of Pupils graduating from

Elementary to High School

“Pupils promoted from 8th grade (elementary school)

to 9th grade (high school) will be furnished by their class

room teacher or principal, for delivery to their parents

or guardians, on a date fixed by the Superintendent of

Schools prior to their graduation, the appropriate in

structions and forms on which their parents or guardians

may exercise their choice of the school next to be attended

by such pupils. A reasonable time (15 days) will be pro

vided for returning the form after it has been distributed,

and the written instructions accompanying the form shall

set forth in detail the Board of Education policies per

mitting a free choice of the school next to be attended.

A choice must be exercised, as to each child, as a condition

to his being admitted to school.”

Section 5. Lateral Transfers by Pupils, Eligible to

Continue in a School where Currently En

rolled. Notice!

“Prior to the end of classes for each school year, pupils

eligible to continue in the same school will be assigned

for the forthcoming year. At a date fixed by the Super

intendent and in advance of the time that re-assignment

for the coming year is made, all pupils will be furnished

by their classroom teachers appropriate forms and in

structions for use by their parents in exercising their right

to apply for a transfer of their child to a school of their

choice for the coming year. Such instructions will set

Defendant’s Exhibit “A”

28a

forth in detail the Board of Education policies respecting

transfers without regard to race, color, or national origin

for the coming year, and will state that it is mandatory

for parents to sign and return the freedom of choice

forms.”

Section 6. Forms and Notices to be sent by School to

Parents

(a) Notice of Board Policy. “For the school year 1965-66

and for all school years thereafter, the Stanly County

Board of Education has adopted a plan for registering,

enrolling, and assigning pupils giving parents the right

to make a choice to be attended by their child, without

regard to race, color, or national origin. Use the enclosed

form to state your preference as to the school to which

you wish your child assigned. You must write into the

form on the lines indicated, the name of the child, the

grade he will be in, and the name of the school you wish

him to attend. Sign and date the form. This form must

be properly filled out and returned to your child’s teacher

or principal not later than .............................. 1965.

A freedom of choice request must be submitted for each

child as a condition to his being admitted to a school. If

more requests for a school are made than the school can

accommodate, due to over crowding of facilities, the Board

of Education will make assignments by giving preference,

without regard to race, color, or national origin, to those

choosing the school residing closest to it. If your child

is denied his choice for this reason, you will be notified,

and you may on appropriate forms state a second choice

of assignment.”

(b) Form to be used by Parent:

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

29a

“I am the parent or guardian o f .................................. -.....

(p u p il’s name and address)

whom I wish enrolled for the school year 1965-66 in the

.................. grade at th e ....................................... School.

Dated th e.................. day o f ............................... 1965.

(signed) .............................................”

(Parent or Guardian)

Section 7. Capacity o f Schools

Capacity of schools will be determined by the standards,

requirements, and regulations promulgated by the State

Board of Education.

Section 8. Transportation

(a) Where transportation of pupils is provided, children

will be assigned to busses on a non-segregated basis. All

services, facilities, activities and programs in each school

shall henceforth be available to every pupil of each school

on a non-discriminatory basis.

(b) If a parent chooses a school not normally served

by the transportation system of the district as now set up,

transportation must be furnished by the parent or guardian.

Section 9. Procedures for Informing and Preparing

Staff for Transition

Staff will be informed and prepared for the transition

by convocation of all staff personnel on an integrated basis.

Section 10. Policy of Board of Desegregation of Staff

The Board of Education is aware of and recognizes that

school desegregation includes desegregation of faculty and

is now in the process of developing a policy whereby staff

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

30a

and professional personnel will be employed solely on

the basis of competence, training, experience, and personal

qualifications and will be assigned to and within the schools

of the nnit without regard to race, color, or national origin.

This policy will be put into effect immediately after it is

developed, but in any event to commence by the 1966-67

school term.

Section 11. Plans for Future

The Board of Education recognizes that eventually the

all-Negro schools in the district will have to be abandoned,

and to this end the Board will develop a plan for additions

to present all-white schools or the construction of new

plants, and all pupils in the district will be assigned on a

non-discriminatory basis.

As of June 1, 1965 slightly less than one-half (% ) of the

approximately 1,000 Negro children had been assigned to

schools of their choice. In each instance assignment was

made to previously all-white schools as requested.

The Board of Education expects to completely desegre

gate all Negro schools by September, 1967 by providing

adequate facilities.

Section 12. Certification

This is to certify that the foregoing Plan for Compliance

was adopted by the Stanly County Board of Education

in called session on June 7, 1965.

Date June 7, 1965

s / Reece B. McSwain

C h a ir m a n

Date June 7, 1965

s / Luther A. Adams

S e c r e t a r y a n d S u p e r in t e n d e n t

Defendant’s Exhibit “A ”

31a

Come now the plaintiffs, by their undersigned attorneys,

and in response to the several motions of defendant, show

the Court as follows:

I

This action was initially tiled by plaintiffs on August 11,

1965, seeking a preliminary and permanent injunction

against the racially discriminatory practices of defendant

in dismissing and refusing to hire individual plaintiff, mem

bers of the class said plaintiff represents, and members of

corporate plaintiff in the public schools under defendant’s

jurisdiction. Plaintiffs also sought injunctive relief against

defendant’s racially discriminatory practices in assigning

teachers and school personnel in the Stanly County School

System. Along with their complaint, plaintiffs filed a mo

tion for preliminary injunction and brief. Defendant has

filed an answer moving

(1) to dismiss the action

(a) for failure to state a claim for relief, and con

tending

(b) and (c) that plaintiffs would be entitled to no

relief;

(d) that defendant owes plaintiffs no legal duty un

der 28 U. S. C. §1652;

(e) that defendant acted within its legal rights;

(f) that plaintiffs have no legal statutory or con

tractual right to public employment ;

(g) that defendant has had no legal or contractual

relation with corporate plaintiff and that said

Response

32a

plaintiff is not a proper party to maintain the

action;

(2) to dismiss the action because the contracts for teach

ers were only for one year which expired;

(3) for summary judgment on the pleadings, affidavits

and exhibits, realleging the matters set forth in (1)

and (2) above and alleging that defendant, being an

agent of the State, was not subject to the provisions

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964;

(4) to dismiss the action because defendant has a con

stitutional right to enter into contracts for employ

ment with public school teachers and that the action

here would violate defendant’s right of due process

under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States as an impairment of defendant’s

right to enter into contracts.

II

To all said motions of defendant, plaintiffs say and

allege:

(1) That the First Defense of defendant is denied;

(2) That the Second Defense of defendant, realleging

the allegations of the First Defense, is denied;

(3) That the Third Defense of defendant is denied;

(4) That the Fourth Defense of defendant is denied;

(5) That the Fifth Defense of defendant is denied;

(6) That the Sixth Defense of defendant is denied;

(7) That the Seventh Defense of defendant is denied;

Response

33a

(8) That the Eighth Defense of defendant is denied.

F u r t h e r a n s w e r in g a n d r e s p o n d in g to t h e m o t io n s o p

DEFENDANT, PLAINTIFF SAYS AND ALLEGES:

I

That by this action, plaintiffs seek an injunction against

defendant’s use of race and color in employing and assign

ing teachers and school personnel in the Stanly County

School System. Such practices by defendant are clearly

violative of the rights of individual plaintiff and others of

her class and members of corporate plaintiff. See Alston

v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir.

1940); Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

------F. Supp.------ (Civil No. 64-C-73-R, W.D, Va., June 3,

1965).

II

That while the contracts of employment between defend

ant and Negro teachers and school personnel ran for one

year, defendant follows a practice of automatically renew

ing such contracts upon indications by employees of a de

sire to remain in the system; that individual plaintiff, and

others of her class and members of corporate plaintiff indi

cated a desire to remain in the system but defendant refused

to renew their contracts or refused to consider their appli

cations for employment on the basis of race and color in

violation of their rights under the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. See Franklin v. County

School Board of Giles County, supra.

Response

34a

III

Plaintiffs have alleged, and defendant denied, that de

fendant has refused to rehire individual plaintiff and others

of her class and that defendant has followed and has con

tinued to follow a practice, custom and usage of hiring, as

signing and dismissing Negro teachers solely on the basis

of race and color. There are thus genuine, relevant and

material facts in dispute and no basis for summary judg

ment. Rule 56, FRCP; Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice

& Procedure <§§1232.2, 1234 (1958).

IV

Corporate plaintiff is a proper party to seek the relief

prayed for in its complaint and motion for preliminary

injunction. Franklin v. County School Board of Giles

County, supra; Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk,

supra; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510; NAACP

v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, ------ F. Supp. ------ (Civil No. 1974,

W.D. N.C., July 14, 1965).

W h e r e f o r e , plaintiffs pray that the several motions of

defendant be denied and that plaintiff be granted relief as

prayed in its complaint and motion for preliminary injunc

tion.

Response

Respectfully submitted,

35a

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference

Counsel for each of the parties in the above-entitled ac

tion, pursuant to notice, appeared on the 20th day of Octo

ber, 1965, for an initial pre-trial conference. J. LeVonne

Chambers, Esq., appeared as counsel for the Plaintiffs, and

Staton P. Williams, Esq., and Henry C. Doby, Jr., Esq.,

appeared as counsel for the Defendant.

After conferring with counsel for the parties, the follow

ing order is entered on initial pre-trial conference:

( 1 ) It is O r d e r e d that each of the parties commence

forthwith the processes of appropriate discovery and that

same be completed on or before the 20th day of December,

1965.

(2) At the time of the initial pre-trial conference, the

Court overruled all pending motions previously lodged by

the Plaintiffs and the Defendant without prejudice to the

right of the parties to reassert any or all of the pending mo

tions after the facts have been fully developed. Counsel

for the Plaintiffs will he responsible for the preparation of

all the necessary orders and present them to the Court for

signing after they have been seen and endorsed by counsel

for the Defendant with respect to form.

(3) To the extent presently known, the parties estimated

that the trial would consume less than half a day.

(4) The parties were advised that it was anticipated that

the final pre-trial conference would be held during the early

36a

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference

part of January 1966, and that the case would he tried

shortly thereafter.

/ s / E d w in M. S t a n l e y

United States District Judge

October 28,1965

A True Copy

Teste:

H e b m a n A m asa S m it h , Clerk

By: D e a n J. S m it h

Deputy Clerk

37a

Motion

Come now the plaintiffs by their undersigned attorneys

and respectfully move the Court for leave to amend their

complaint and other pleadings filed in the above subject

cause to correctly show the name of the party-defendant,

and, as grounds therefor, show the Court as follows:

1. This action was initially filed by plaintiffs on August

11, 1965, seeking a preliminary and permanent injunction

against the defendant for refusing to hire individual plain

tiff and members of plaintiff association and from employ

ing and assigning members of plaintiff association on the

basis of race or color.

2. In the style of their action and in the body of their

complaint and motion for preliminary injunction and other

pleadings, plaintiffs listed the defendant as the Stanley

County Board of Education.

3. That the correct spelling of the party-defendant is

the Stanly County Board of Education.

4. Despite the misspelling of the name of the party-

defendant no prejudice has resulted to the defendant since

it was properly served with summons and process and had

due notice of the pendency of this action and has filed an

answer and other pleadings in response to same.

W h e b e f o k e , plaintiffs respectfully move the Court for

leave to amend their complaint and other pleadings as

follows:

(a) To change the spelling of the party-defendant to

“ The Stanly County Board of Education, a public body cor

porate of Stanly County, North Carolina,” in lieu of “The

38a

Motion

Stanley County Board of Education, a public body corpo

rate of Stanley County, North Carolina,” where it appears

in the style of the action and the body of plaintiffs’ com

plaint and other pleadings.

(b) To change the spelling of “ Stanley” County to

“ Stanly” County where it appears in the style of the action

and body of plaintiffs’ complaint and other pleadings.

39a

Order Dated November 9 , 1965

This cause coming on to be heard upon motions by defend

ant to dismiss and for summary judgment and upon motion

of plaintiffs for preliminary injunction and it appearing to

the Court that the same should be denied at this time but

without prejudice to the right of the parties to renew their

motions, or any of them, at some future date if the parties

desire.

It is , t h e r e f o r e , o r d e r e d that the motions of defendant

to dismiss and for summary judgment be and the same are

hereby denied without prejudice to the right of the defend

ant to renew its motions, or any of them, at some future date

if defendant so desires.

It is f u r t h e r o r d e r e d that the motion of plaintiffs for pre

liminary injunction be and the same is hereby denied with

out prejudice to the right of the plaintiffs to renew their

motion at some future date if plaintiffs so desire.

/ s / E d w in M. S t a n l e y

Chief Judge, United States District Court

Dated: Nov. 9,1965

40a

Order Dated November 9, 1965

This cause coming on to be heard before the undersigned

District Judge upon motion of plaintiffs to amend their

complaint and other pleadings to show the correct spelling

of the Stanly County Board of Education and Stanly

County, and it appearing to the Court that there is good

cause therefor and that counsel for defendant has consented

to same.

It is , t h e r e f o r e , o r d e r e d that the complaint and other

pleadings of plaintiffs be amended to designate the party-

defendant as “The Stanly County Board of Education, a

public body corporate of Stanly County, North Carolina,”

in lieu of “The Stanley County Board of Education, a pub

lic body corporate of Stanley County, North Carolina,”

wherever it appears in the style of the action and body of

the complaint and other pleadings.

It is f u r t h e r o r d e r e d that the pleadings be amended to

read Stanly County in lieu of “ Stanley” County wherever

the same appears in the style of the action and body of the

complaint and other pleadings.

/ s / E d w in M. S t a n l e y

Chief Judge, United States District Court

Dated: Nov. 9,1965

41a

Motion of Leave to Amend Complaint

Come now the plaintiffs by their undersigned attorneys

and respectfully move the Court for leave to amend their

complaint, heretofore filed in the above subject cause, by

adding the following paragraph to the prayer for relief,

immediately following the first paragraph thereof;

“That the plaintiff be reinstated as a teacher in the School

System in the same or comparable position.”

Respectfully submitted,

42a

Memorandum

This matter was scheduled for Final Pre-Trial Confer

ence in the United States Courtroom, Post Office Building,

Salisbury, North Carolina, on Wednesday, February 2,

1966. J. LeVonne Chambers, Esquire, appeared as counsel

for the Plaintiffs; and Staton P. Williams, Esquire, and

Henry C. Doby, Jr., Esquire, appeared as counsel for the

Defendant.

When the matter was called for Final Pre-Trial Con

ference, the parties presented to the Court the proposed

O r d e r on Final Pre-Trial Conference, which had been

signed by counsel for the parties. The O r d e r was approved

and O r d e r e d filed in the form submitted.

The case is set for trial on April 25, 1966, at Salisbury,

North Carolina. The actual calendar for this term should

be mailed to the parties not later than thirty days prior to

the time set for trial.

The estimated trial time is two days. Trial briefs will

be filed with the Court on or before the 15th day of April,

1966.

The motion to amend the complaint, filed by the plain

tiffs, is allowed; and the plaintiff will accordingly prepare

an O r d e r for the signature of the Court, first presenting

same to counsel for the defendant for approval as to form.

I, Graham Erlacher, Official Reporter of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina, do hereby certify that the foregoing is a true

transcript from my notes of the entries made in the above-

entitled Case No. C-140-S-65 before and by Judge Eugene

A. Gordon, on February 2, 1966, in Salisbury, North Caro

lina, and I do hereby further certify that a copy of this

43a

Memorandum

transcript was mailed to each of the below-named attorneys

on February 7, 1966.

Given under my hand this 7th day of February, 1966.

/ s / G r a h a m E rlacher

Official Reporter

cc: J. LeVonne Chambers, Esq.

Staton P. Williams, Esq.

Henry C. Hoby, Jr., Esq.

44a

Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 16 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rule 22, a final pretrial

conference was held in the above-entitled cause on the 2nd

day of February, 1966.

J. LeVonne Chambers appeared as counsel for plaintiffs.

Staton P. Williams and Henry C. Doby, Jr. appeared as

counsel for defendant.

1. It is stipulated that all parties are properly before the

Court, and that the Court has jurisdiction over the parties

and the subject matter, except that defendant contends that

it is an agency and political subdivision of the State of

North Carolina and as such is not subject to suit without

its consent, and the Court is without jurisdiction to hear

and determine the purported claim.

2. It is stipulated that all parties have been correctly

designated, and there is no question as to misjoinder or

nonjoinder of the parties, except that defendant contends

that as to the corporate plaintiff, there is a defect in parties

plaintiff.

3. Plaintiffs’ contentions are:

That prior to and since the Brown decision the defendant

Board has followed a policy of hiring and assigning teachers

and school personnel on a racial basis, that Negro teachers

and school personnel are, without exception, assigned to

schools attended entirely by Negro students; that white

teachers and school personnel are assigned to schools at

tended by white students that for the 1965-66 school year,

approximately 287 Negro students transferred to formerly

all-white schools; that the School Board reduced the teacher

Order on Final Pretrial Conference

45a

allotment at the Negro schools and dismissed Negro teach

ers, including plaintiff Audrey Gillis Wall, solely because of

her race, pursuant to defendant’s continued practice of mak

ing racial assignments of teachers.

4. Defendant’s contentions are:

(a) Plaintiff Audrey Gillis Wall was not employed by

defendant School Board as a teacher in its public school

system for the 1965-66 school year because the principal

under whom she had taught in the prior school year recom

mended that she not be employed for the reason she was

not a fit and suitable teacher.

(b) Plaintiff Audrey Gillis Wall had no right in fact or in

law of employment as a schoolteacher by defendant School

Board.

(c) Plaintiffs do not state a claim in law or in fact upon

which the relief sought can he granted.

(d) Defendant has never had any legal or contractual re

lationship with the corporate plaintiff, and the corporate

plaintiff cannot in law maintain this action.

(e) Any contractual relation that had existed between

plaintiff Audrey Gillis Wall and defendant had terminated

and expired, and plaintiff Audrey Gillis Wall was not en

titled to employment by defendant.

5. Stipulations:

(a) At the beginning of the 1962-63 school year defend

ant School Board consolidated ten all-white schools in its

system into three high schools.

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

46a

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

(lb) Defendant hired the following new teachers since the

institution of this action:

G ra d e or

C ertifica te N a m e o f T ea c h er S c h o o l S u b je c t T a u g h t

Sec. A M ary C. Plummer W est Stanly English and B iology

Sec. A Mildred T. Lee W est Stanly H om e Economics

Prob. B Gretchen J. Corbitt Locust 4th-5th Combination

Elem. A Doris I. Melchor Locust 5th-6th Combination

Sec. A Irm a D. Altman W est Stanly H om e Economies

Prov. Y oc. H arold E. Burris W est Stanly Bricklaying

Prim . A Barbara A . Jackson Locust 5th Grade

Elem. B Sandra B. Biles Norwood 4th Grade

Sec. A Samuel Caldwell, Jr. North Stanly Social Studies

Sec. A Lois H . M abry Stanly County Teacher o f Hom e-

bound Children

6. Plaintiffs’ exhibits to be offered at trial:

(a) Answers to interrogatories.

(b) Minutes of Board meeting June 7, 1965.

(c) Teacher allotment form and allotments for the 1965-

66 school year.

(d) List of new teachers.

(e) List of teachers not returning for the 1965-66 school

year.

(f) List of schools and enrollment for the 1965-66 school

year.

(g) Teacher directory.

(h) Contract for instructional service.

(i) Letter of April 30, 1965.

(j) List of resignations and contracts to be approved

July 7,1965.

47a

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

/

7. It is stipulated and agreed that defendant’s counsel

has been furnished a copy of each exhibit identified by the

Plaintiffs.

8. It is stipulated and agreed that each of the exhibits

identified by plaintiffs is genuine and, if relevant and ma

terial, may be received in evidence without further identifi

cation or proof.

9. Defendant’s exhibits to be offered at trial:

(a) Answers to interrogatories.

10. It is stipulated and agreed that plaintiffs’ counsel has

been furnished a copy of each exhibit identified by the de

fendant.

11. It is stipulated and agreed that each of the exhibits

identified by defendant is genuine and, if relevant and ma

terial, may be received in evidence without further identifi

cation or proof.

12. List of names and addresses of all known witnesses

that plaintiffs may offer at trial, together with a brief state

ment of what counsel proposes to establish by the testimony

of each witness:

S ta te m e n t o f F a c ts

W i tn e s s A d d r e s s to be E sta b lish e d

S. Edmund Reutter, Jr. Columbia University General policies re-

Professor o f Education New York, New Y ork garding hiring and as-

Columbia University aigning school person

nel including person

nel in the Stanly County

School System.

Luther A . Adams Albemarle, N. C. Procedures follow ed in

hiring and assigning

teachers in school per

sonnel in Stanly County

School System.

48a

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

Audrey Gillis W all Charlotte, N. C. Qualifications and ex

perience in Stanly

County School System.

C. L. H ines Albemarle, N. C. General policies fo l

lowed in recommending

teachers fo r em ploy

m ent; dismissing teach

ers at the reduction in

allotm ent;

Reece B. M cSwain Albemarle, N. C. P olicy o f Board in hir

ing and assigning teach

ers and students.

Robert M cLendon Albemarle, N. C. General policies fo l

lowed in recommending

teachers fo r em ploy

ment, dismissing teach

ers at the reduction in

allotm ent;

13. List of names and addresses of all known witnesses

that defendant may offer at trial, together with a brief

statement of what connsel proposes to establish by the

testimony of each witness:

W i t n e s s

Luther A . Adams

A d d r e s s

Albemarle, N. C.

S ta te m e n t o f F a c ts

to be E s ta b lish e d