Youth-Lawyer Partnership Hailed for Rights Triumphs

Press Release

June 26, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Youth-Lawyer Partnership Hailed for Rights Triumphs, 1964. 2948f485-bd92-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6c8cfae0-662e-4285-a6ea-ab9b05e0f925/youth-lawyer-partnership-hailed-for-rights-triumphs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

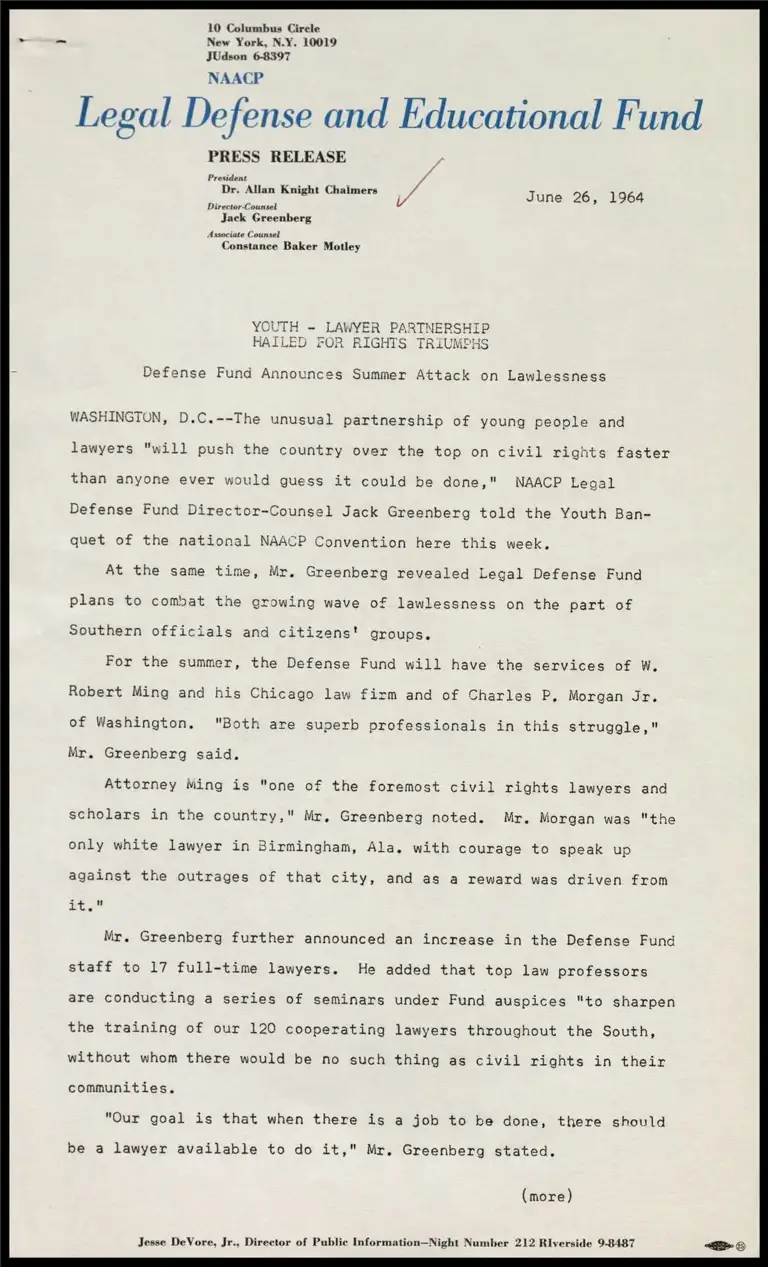

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President j : i

rn aie Jone 26, 1964

Teck C-ccatiery

Associate Counsel

Constance Baker Motley

YOUTH - LAWYER PARTNERSHIP

HAILED FOR RIGHTS TRIUMPHS

Defense Fund Announces Summer Attack on Lawlessness

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The unusual partnership of young people and

lawyers "will push the country over the top on civil rights faster

than anyone ever would guess it could be done," NAACP Legal

Defense Fund Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg told the Youth Ban-

quet of the national NAACP Convention here this week.

At the same time, Mr. Greenberg revealed Legal Defense Fund

plans to combat the growing wave of lawlessness on the part of

Southern officials and citizens' groups.

For the summer, the Defense Fund will have the services of Ww.

Robert Ming and his Chicago law firm and of Charles P. Morgan Jr.

of Washington. "Both are superb professionals in this struggle,"

Mr. Greenberg said,

Attorney Ming is "one of the foremost civil rights lawyers and

scholars in the country," Mr, Greenberg noted. Mr. Morgan was "the

only white lawyer in Birmingham, Ala. with courage to speak up

against the outrages of that city, and as a reward was driven from

to

Mr. Greenberg further announced an increase in the Defense Fund

staff to 17 full-time lawyers. He added that top law professors

are conducting a series of seminars under Fund auspices "to sharpen

the training of our 120 cooperating lawyers throughout the South,

without whom there would be no such thing as civil rights in their

communities.

"Our goal is that when there is a job to be done, there should

be a lawyer available to do it," Mr. Greenberg stated.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 Ss

Youth - Lawyer Partnership -2- June 26, 1964

Hailed for Rights Triumphs

In his talk to the assembled young paople, Mr. Greenberg

traced the pace-setting role of the law that led to the historic

precedent of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954,

Lashing out at tokenism, Mr. Greenberg warmly praised the

youths who, in seeing through the "hypocrisy of our community

leaders," initiated the sit-ins and peaceful demonstrations in

the ‘60's.

"It is no accident that the sit-ins began in Greensboro, N,C.

and rapidly spread through Raleigh, Durham, Charlotte and else-

where in that state because those are the communities where token-

ism was practiced as a fine art," he continued,

Mr. Greenberg said that attorneys are now at work to secure

enforcement of the precedents Legal Defense Fund suits have

created over the years. He stressed the efforts to integrate

schools and hospitals, and to defend demonstrators.

Citing the recent U.S, Supreme Court reversal of 77 sit-in

convictions, Mr. Greenberg emphasized that the law has repeatedly

sanctioned peaceful demonstrating, and that "violence almost

always has come from white supremacists.

"The hallmark of a demonstration is what NAACP youth and the

youth of other organizations were doing when they quietly sat

at the lunch counters all over the South, or paraded on the state

house grounds and made solemn witness against the greatest moral

crime that exists in this country.

"We will triumph if we keep it that way, as I am sure we will,"

Mr. Greenberg told the banquet meeting.

S230 =