Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

November 26, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Petitioner, 1965. 6842d022-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6ca01f20-5ca0-49be-bad5-02581850c3c9/georgia-v-rachel-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

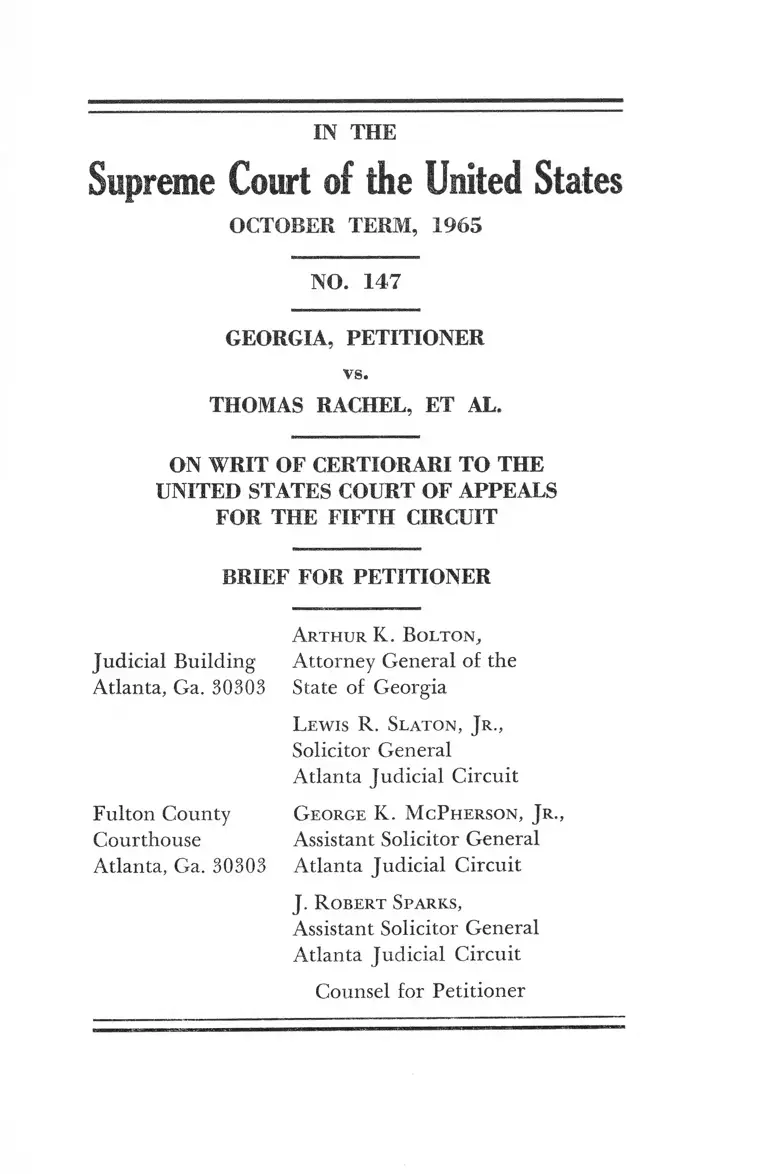

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1965

NO. 147

GEORGIA, PETITIONER

vs.

THOMAS RACHEL, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

A r t h u r K. B o l t o n ,

Judicial Building Attorney General of the

Atlanta, Ga. 30303 State of Georgia

L ew is R . Sl a to n , J r .,

Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

Fulton County G eorge K. M cP h erson , Jr.,

Courthouse Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta, Ga. 30303 Atlanta Judicial Circuit

J . R obert Sparks,

Assistant Solicitor General

Atlanta Judicial Circuit

Counsel for Petitioner

INDEX

Opinions Below______________________________ 1

Jurisdiction_________________________________- 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved___ 3

Questions Presented____________________________4

Statement of the Case__________________________ 7

Summary of Argument________________________ 10

Argument___________________________________ 13

I. The Notice of Appeal of the Remand Order

Was Not Timely Filed, and Petitioner’s

Timely Motion to Dismiss Appeal Should

Have Been Granted_____________________ 13

II. The Petition for Removal Does Not Set

Out Any Valid Ground for Removal_______ 30

III. Assuming Arguendo that Remand to the

District Court for an Evidentiary Hearing

Was Proper, the Directions Given the

Lower Court Were Clearly Erroneous______ 50

Conclusion___________________________________54

Appendices

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes

Involved________________________________ 59

Certificate of Service__________________________ 58

Appendix “A” _______________________________ 59

CITATIONS

Cases

Arkansas v. Howard, D.C.E.D. Ark., 1963, 218 F.

Supp. 626______________________________ 32, 49

Berman v. United States, 1964, 378 U.S. 530_____ 29

Page

l

INDEX (Continued)

Birmingham v. Croskey, D.C.N.D. Ala., 1963, 217

F. Supp. 947_______________________________ 49

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632___________11, 52, 53,56

City of Chester v. Anderson, 3 Cir., 1965, 347 F.

2d 823_________________________________ 44, 45

Chicago etc R. Co. v. Roberts, 1891,141 U. S. 690__26

City of Clarksdale, Miss. v. Gertge, D.C.N.D.

Miss., 1964, 237 F. Supp. 213______________47, 49

DiBella v. United States, 1962,369 U.S. 121___23, 25, 27

Gibson v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U.S. 565_________32

Griffin v. Maryland, 1964, 378 U.S. 130__________51

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, S. C., 1964, 379 U.S.

306___________________ 6, 7, 11, 12, 50, 51, 52, 53

Hill v. Pennsylvania, D.C.W.D. Pa., 1960, 183 F.

Supp. 126_________________________________ 32

Hull v. Jackson County Circuit Court, 6 Cir.,

1943, 138 F. 2d 820_________________________ 32

Kentucky v. Powers, 1906, 201 U.S. 1__32, 33, 34, 42

Maryland v. Soper, Judge, (No. 1), 1925, 270

U.S. 9____________________________________ 48

Moore v. United States, 10 Cir. 1955, 150 F. 2d

323_____________________________________ 21

Murray v. Louisiana, 1896, 163 U.S. 101___________ 32

Neal v. Delaware, 1880, 103 U.S. 370_________32, 42

North Carolina v. Jackson, D.C.M.D.N.C., 1955,

135 F. Supp. 682___________________________ 32

Nye v United States, 1941, 313 U.S. 28__13, 19, 20, 21

Parr v. United States, 1956, 351 U.S. 513_________ 25

Page

u

INDEX (Continued)

Peacock et al. v. City of Greenwood, 5 Cir., 1965,

347 F. 2d 679________________________ 34, 44, 46

People of the State of New York v. Galamison, 2

Cir., 1965, 342 F. 2d 255; cert. den. 85 S. Ct.

1342_____________________________ 38, 44, 45, 49

Peterson v. City of Greenville, S. C., 1963, 373

U.S. 244___________________________________51

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, Ala., 1963,

373 U.S. 262_______________________________ 51

Smith v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U.S. 592__________32

Snypp v. Ohio, 6 Cir., 1934, 70 F. 2d 535, cert. den.

293 U.S. 563_______________________________ 32

Texas v. Doris, D.C.S.D. Texas, 1938, 165 F. Supp.

738_______________________________________ 32

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 1962, 362 U.S. 199__51

United States v. Koenig, 5 Cir., 1961, 290 F. 2d

166_____________________ ______________ 23, 25

United States v. Lederer, 7 Cir., 1943, 139 F. 2d

861_______________________________________ 21

United States v. Robinson, 1960, 361 U.S. 220___ 29

United States v. United Mine Workers of Ameri

ca, 1947, 330 U.S. 258_______________________ 28

United States v. Williams, 4 Cir., 1955, 227 F. 2d

149_______________________________________ 18

Virginia v. Rives, 1879, 100 U.S. 313_________ 31, 42

Williams v. Mississippi, 1898, 170 U.S. 213________32

Zacarias v. United States, 5 Cir., 1958, 261 F. 2d

416_________________________________ 22, 25, 27

Page

iii

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

Constitution of the United States:

First Amendment__________________________ 59

Fourteenth Amendment_____________________ 59

Statutes and Rules:

Act of 1866, Sec. 3 (14 Stat. 27, 28)____________59

Act of 1875, Sec. 5 (18 Stat. 470, 472)__________61

Act of 1887, Secs. 2 & 5 (24 Stat. 553, 555)_____ 60

Former Sec. 71, former Title 28, U.S.C., (Ju

dicial Code Sec. 28)_______________________ 61

Former Sec. 74, former Title 28, U. S. C., (Ju

dicial Code, Sec. 31)_______________________62

Former Sec. 76, former Title 28, U. S. C., (Ju

dicial Code, Sec. 33)_______________________62

Act of February 24, 1933, c. 119, 47 Stat. 904__63

Act of March 8, 1934, c. 49, 48 Stat. 399_______ 64

Act of June 29, 1940, c. 445, 54 Stat. 688_______ 65

Act of November 21, 1941, c. 492, 55 Stat. 776„_66

Sec. 3731, Act of June 25, 1948, c. 645, 62 Stat.

683, pp. 844-845__________________________66

Sec. 3732, Act of June 25, 1948, c. 645, 62 Stat.

683, p. 845_______________________________68

Sec. 1443 (1) (2), Title 28, U. S. C____________ 68

Sec. 1446 (a), (c), (d), Title 28, U. S. C________ 69

Sec. 1447 (c), (d), Title 28, U. S. C____ _______ 69

INDEX (Continued)

Page

iv

INDEX (Continued)

Sec. 2107, Title 28, U. S. C__________________ 70

Sec. 201 (b) (2), Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78

Stat. 241 (pp. 289-291)______________ _____ 70

Sec. 203, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241

(pp. 289-291)______________________ 71

Sec. 1404, Title 18, U. S. C________________ 71

Sec. 1981, Title 42, U. S. C__________________72

Revised Statutes, Title XIII, the Judiciary, Sec.

641_____________________________________ 72

Rule 37 (a) (2), Title 18, U. S. C_____73

Rule 54 (b) (1), Title 18, U. S. C_____74

Rule 45 (a), Title 18, U. S. C_________________74

Rule 59, Title 18, U. S. C____________________74

Rule 73 (a), Title 28, U. S. C________________ 75

Georgia Code Annotated, 26-3005 (Ga. Laws

1960, pp. 142 & 193)______________________ 75

Rule III, Rules of Practice and Procedure After

Plea of Guilty, etc., 292 U.S. 662______ 75

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Black’s Law Dictionary, Third Edition, 1933, pp.

1024, 1025_________________________________ 19

Page

v

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1965

NO. 147

GEORGIA, PETITIONER

vs.

THOMAS RACHEL, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The pertinent opinions of Courts below are as follows:

The remand order and opinion of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (R.

5-9) is not reported. An Order of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, staying the re

mand order of the district court, one judge dissenting,

(R. 13-14) is not reported. The opinion of the Court

of Appeals, two judges dissenting in part and concurring

1

2

in part, is reported at 342 F. 2d 336, (R. 20-35) . The

per curiam opinion of the Court of Appeals denying a

rehearing en banc, one judge dissenting and another

judge dissenting in part and concurring in part, is re

ported at 343 F. 2d 909 (R. 51).

JURISDICTION

The opinion and judgment of the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals were entered on March 5, 1965 (R. 20-36).

A petition for rehearing en banc was filed by Petitioner

on March 25, 1965 (R. 37-49) and was denied by the

Court of Appeals on April 19, 1965 (R. 51). The Peti

tion for Certiorari was filed in this Court on May 15,

1965, and was granted by this Honorable Court in an

order dated October ] 1, 1965 (R. 52).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28

U.S.C. 1254(1). The judgment to be reviewed was

rendered by a majority of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit, reversing the judgment of the

United States District Court for the Northern District

of Georgia in which the District Court remanded to Ful-

tion Superior Court twenty State of Georgia criminal

prosecutions which had theretofore been removed to said

District Court under the purported authority of the Civil

Rights Acts (28 U.S.C. 1443) . The judgment of said

Court of Appeals to be reviewed remanded the State

Court criminal prosecutions to the United States District

Court with directions to hold an evidentiary hearing and

to dismiss the prosecution if one finding of fact was

made.

3

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, RULES,

AND STATUTES INVOLVED

The First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution of the United States of America are involved.

The Statutes and Rules involved are the following:

1. Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27, 28)

2. Act of 1875 (18 Stat. 470, 472)

3. Act of 1887 (24 Stat. 553, 555)

4. Former sections 71, 74, 76, former Title 28 U.S.C.

(March 3, 1911, 36 Stat. 1094, 1096, 1097)

5. Act of February 24, 1933, c. 119, 47 Stat. 904

6. Act of March 8, 1934, c. 49, 48 Stat. 399

7. Act of June 29, 1940, c. 445, 54 Stat. 688

8. Act of November 21, 1941, c. 492, 55 Stat. 776

9. Act of June 25, 1948, c. 645, 62 Stat. 683, pp. 844-

845

10. Sections 1443 (1) (2); 1446 (a), (c), (d) ; and

1447 (c) and (d), Title 28, U.S.C. (62 Stat. 938,

1948, 63 Stat. 102, 1949) ; Section 2107 Title 28

U.S.C.

11. Civil Rights Act of 1964, Secs. 201 (b) (2) and

203, 78 Stat. 241 (pp. 289-291)

12. Sections 3731, 3732 and 1404, Title 18, U.S.C.

13. Section 1981, Title 42 U. S. C.

14. Revised Statutes, Title XIII, the Judiciary, Sec.

641

4

15. Rules 37 (a) (2), 54 (b) (1), 45 (a), and 59,

Title 18, U. S. C.

16. Rule 73 (a), Title 28, U. S. C.

17. Georgia Code Annotated, 26-3005 (Ga. Laws

1960, pages 142 and 143)

18. Rule III, Rules of Practice and Procedure After

Plea of Guilty, etc. (292 U. S. 662)

The constitutional provisions, Rules, and statutes in

volved being somewhat lengthy, their pertinent text is

set out in Appendix A for Petitioner, as authorized by

Rule 40 (1) (c) or are quoted verbatim in the text of

this brief.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether a Notice of Appeal from an order of

remand of the District Court entered in twenty State

Court criminal prosecutions theretofore removed to

said District Court under the purported authority of

28 U.S.C. 1443 is timely, where said Notice of Appeal

was not filed within ten days from the entry of said

remand order, as required by Rule 37 ( a ) ( 2 ) , Fed.

R. Crim. P.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question I are:

(a) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

holding that the ten day time limit for filing a notice

of appeal prescribed by Rule 37 (a) (2), Fed. R. Crim.

P., has no application to this case because, as held by

the majority of the Court, that Rule applies only to

criminal appeals after verdict, or finding of guilt, or plea

of guilty?

(b) Is not Rule 37 (a) (2) specifically made appli

5

cable to an appeal of a remand order entered in a re

moved criminal case by the provision of Rule 54 (b) (1),

Fed. R. Crim. P. that the Criminal Rules apply to crim

inal prosecutions removed to the United States District

Courts from state courts and govern all procedure after

removal, except dismissal?

(c) Did the Court of Appeals have jurisdiction to

entertain the appeal where the Notice of Appeal of the

order of remand was filed sixteen days after the entry

of the remand order, and should not Petitioner’s timely

Motion to Dismiss Appeal on the grounds that the Notice

of Appeal was not timely filed have been granted?

II. Assuming arguendo that Question I is decided

adversely to Petitioner and the merits of the judgment

of the Court of Appeals is reached, the following

question is presented: Whether the Petition for Re

moval, which does not allege that any Georgia statute

is unconstitutional and does not specifically allege a

denial of the equal rights of the Defendants by vir

tue of the State statute under which they were being

prosecuted in the State Court, sets forth a valid ground

for removal under Section 1443, Title 28, U.S.C.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question II are:

(a) Did the Court of Appeals err in holding that a

Petition for Removal need contain only the “bare bones

allegation of the existence of a right”; that the instant

Petition for Removal did in fact allege the denial of

protected rights by State legislation; and that the Peti

tion for Removal adequately alleged that the Defendants

suffered a denial of equal rights by virtue of the statute

under which they were being prosecuted in the State

Court?

6

(b) Whether the Defendants are entitled to a hear

ing in a federal forum for the purpose of proving a de

nial of their rights under a law providing for their equal

rights because of State legislation, under the meager alle

gations of the “notice-type” pleading in their Petition

for Removal, and whether the District Court erred in

remanding said cases to the State Court upon considera

tion of the allegations of the Petition for Removal alone,

without ordering an evidentiary hearing.

III. Whether the majority of the Court of Appeals

erred in reversing the remand order of the District

Court and remanding the cases to said District Court

with directions to hold a hearing, and in further hold

ing that, if, upon such a hearing, it is established

that the removal of the Defendants from the various

places of public accommodation was done for racial

reasons, it would become the duty of the District

Court to order a dismissal of the prosecutions with

out further proceedings, under the holding of Hamm

v. City of Rock Hill, 1964, 379 U. S. 306, 85 S. Ct.

384.

Other subsidiary questions fairly comprised within

Question III are:

(a) Did the aforesaid directions by the majority of the

Court of Appeals to the District Court misconstrue and

expand the doctrine of Hamm, supra, to mean that all

criminal prosecutions arising from removal of persons for

racial reasons from places of public accommodation must

be abated, without regard to any possible evidence as to

the peaceful or nonpeaceful conduct of the particular

Defendants involved, and did the aforesaid directions

unduly limit the discretion of the District Court in de

7

riding whether the Hamm decision was controlling or

was distinguishable on other grounds based on the pos

sible evidence adduced at the hearing?

(b) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

remanding the case to the District Court with the direc

tions aforesaid, without requiring the removing Defend

ants to prove in the hearing that the teachings of Hamm

would not be applied fairly to them by the Georgia

Courts if the prosecutions were remanded to the State

courts?

(c) Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

failing to affirm the District Court’s order of remand,

thus allowing the Courts of Georgia to apply the doctrine

of the Hamm decision, rendered subsequent to the re

moval of these cases, to these prosecutions?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On August 2, 1963, a Grand Jury of Fulton Superior

Court, Atlanta, Georgia, indicted Thomas Rachel and

19 other defendants in separate indictments for viola

tions of Georgia Laws, 1960, pages 142 and 143, a mis

demeanor. This statute is codified as 26-3005, Georgia

Code Annotated (App. A, page 75) .

The misdemeanor with which Thomas Rachel was

charged was his failure and refusal, on June 17, 1963,

to leave the premises of another, to-wit, Lebco, Inc.,

doing business under the name of Lebs on Luckie Street

after having been requested to leave said premises by

the person in charge.

The indictments returned against the other 19 de

fendants involved here contained identical allegations

to the Rachel indictment with the exception that in some

8

instances the misdemeanor was alleged to have been com

mitted on another date and at a different restaurant in

Fulton County, Georgia.

On February 17, 1964, the Defendant Rachel and

the 19 other Defendants filed a Petition for Removal

in the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia, under the purported authority of

Sections 1443 (1) (2) and 1446, Title 28, U. S. C. (R.

1-5)

Briefly stated, the removal petition alleged that the

State of Georgia by statute was perpetuating customs

and serving members of the Negro race in places of

public accommodation on a racially discriminatory basis,

and on terms and conditions not imposed on the white

race. They further alleged that they were being prose

cuted for acts done under color of authority derived

from the Constitution and laws of the United States,

and for refusing to do an act inconsistent therewith.

(R. 1-5)

The next day after filing of the removal petition, i.e.,

on February 18, 1964, United States District Judge Boyd

Sloan issued an opinion and order remanding said cases

to Fulton Superior Court, stating in part, “the petition

for removal to this Court does not allege facts sufficient

to justify the removal which has been effected.” (R. 5-9)

On March 5, 1964, the Defendants filed a Notice of

Appeal from the order of remand to the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals. (R. 9)

The Defendants filed with the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals a Motion for Stay Pending Appeal, on March

12, 1964.

On March 12, 1964, a hearing was held before a three

9

Judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals on

the motion for stay of the remand order of the District

Court. Petitioner, the State of Georgia, filed a Motion

to Dismiss Appeal on two grounds: (1) that the remand

order of the District Court was not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise, and (2) the Notice of Appeal was not

timely filed, having been filed more than ten days from

date of the remand order. (R. 10-13)

After an oral hearing, the majority of the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals by a 2-1 division granted the stay.

District Judge G. Harrold Carswell, Northern District

of Florida, dissented, saying, “1 would, therefore, grant

appellee’s motion to dismiss.” (R. 13-14)

Thereafter, after extensive oral argument before the

Court of Appeals (R. 19), said Court on March 5, 1965,

entered an opinion by a divided three-judge Court re

versing the judgment of the District Court, and remand

ing the case to the lower Court with instructions to hold

a hearing and to dismiss the prosecutions, if it is es

tablished that the removal of the Defendants from the

various places of public accommodation was done for

racial reasons. Two Judges dissented in part and con

curred in part. (R. 20-35)

A timely Petition for Rehearing En Banc was filed by

the State of Georgia, Petitioner (R. 37-49) and was

denied in a per curiam opinion of the Court of Appeals

entered on April 19, 1965, with one Judge dissenting

and another Judge dissenting in part and concurring in

part (R. 51) .

This Honorable Court granted certiorari in an order

dated October 11, 1965 (R. 52)

The jurisdiction of the Court of first instance, the

10

United States District Court for the Northern Disrict

of Georgia, was invoked by the removing Defendants

under the purported authority of Sections 1443 and

1446 (c) (d), Title 28, U.S.C. (R. 4, 5).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

Only three very basic and important grounds for

reversal are urged by Petitioner. First, the Court of

Appeals had no jurisdiction to consider the appeal, inas

much as the Notice of Appeal of the order of remand

was filed six days too late. The majority of the Court of

Appeals has held, in the first opinion known to counsel

for Petitioner since the 1948 enactment of Title 18,

U.S.C., that the ten-day time limit of Rule 37 (a) (2) ,

Fed. R. Crim. P. for filing a notice of appeal from an

order in a criminal case applies only to criminal appeals

after verdict, or finding of guilt, or plea of guilty. This

novel construction of one of the basic Criminal Rules

originally promulgated by this Honorable Court and

subsequently incorporated by reference in an Act of

Congress in 1948, alone demands reversal. One Judge

of the panel dissented on this ground alone both in the

opinion on the merits and on the petition for rehearing.

II

Secondly, the Petition for Removal completely fails,

according to all federal judicial precedent, to set out a

valid ground for removing State prosecutions to a federal

district court for trial. Petitioner urges that there is no

requirements for a hearing of the allegations of the re

moval petition and that removability must stand or fall

upon the allegations of the petition. All federal case

precedent, including that of this Honorable Court, sup

11

port this position, and Petitioner strongly maintains that

no error was committed by the District Court in re

manding the cases without an evidentiary hearing. The

remand order of the District Court should have been af

firmed.

Ill

(a) Finally, even if Petitioner’s first twTo grounds are

decided adversely to us, the Court of Appeals should be

reversed because the majority opinion has directed the

District Court to look for only one criteria on the hear

ing, and to dismiss the State Court prosecutions if that

single element is found from the evidence. That element

is, of course, the finding that racial reasons were the

cause of the removal of the Rachel, et al, defendants from

the various restaurants. This virtual mandate to the

District Court unduly limits his judicial discretion in

considering whether or not the prosecutions are in fact

controlled by Hamm, supra. Many distinguishing factors

might be raised by the evidence on such a hearing. Were

the defendants peaceable and non-violent in their dem

onstrations? Were the restaurants places of public ac

commodation coming under the purvietv of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964? Under the directions of the Court

of Appeals, the District Court could consider none of

these factors, if the racial factor alone were found.

(b) Further, the Court of Appeals by its remand to

the District Court with directions ignores the fact that

the Supreme Court of Georgia has recognized and fol

lowed the Hamm decision and has abated five similar

State Court prosecutions. Bolton, et al v. State of Georgia,

220 Ga. 632, decided February 8, 1965. The Hamm case

had not been decided when these (Rachel, et al) prose

cutions were pending in the Georgia Courts, and the

Georgia Courts have not had an opportunity to consider

12

these eases in connection with the Hamm doctrine. They

should be afforded that opportunity, as pointed out by

Circuit Judge Bell in his partial dissent (R. 35) . The

action of the majority of the Court of Appeals amounts

to a finding that the Courts of Georgia will not apply

Hamm fairly to these Defendants before such courts have

even been given the opportunity to do so. This casual

treatment of the Georgia Courts involves jeopardy to

our dual system of courts, state and federal, as pointed

out by Circuit Judge Bell. (R. 35). Petitioner feels that,

if these cases are remanded to the District Court for a

hearing, contrary to Petitioner’s other grounds, at the

very least these Defendants should be required to prove

that the Georgia Courts will not treat them fairly, in he

light of Hamm. If they cannot prove this, the cases

should be remanded to the State Courts. The District

Court should not have its hands tied by the erroneous

directions of the majority of the Court of Appeals, in

limiting the hearing to one issue only.

(c) Counsel for Petitioner are not concerned in this

brief with the merits of the State Court prosecutions

against these Defendants, and as to the eventual outcome

of same if they are remanded to the State Courts. We

are deeply concerned with the grave and highly im

portant constitutional question of whether a federal ap

pellate court should accept jurisdiction over State Court

criminal prosecutions and virtually order dismissal of

the actions, without ever giving the State Courts a

chance to reconsider the cases in the light of the latest

decision from this Honorable Court. Particularly is this

so in view of the Bolton decision by the highest Court

of Georgia, which proves conclusively that Georgia

Courts are following the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in racial controversies.

13

For the foregoing reasons, Petitioner respectfully in

sists that the decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of Ap

peals should be reversed.

ARGUMENT

I. THE NOTICE OF APPEAL OF THE REMAND

ORDER WAS NOT TIMELY FILED AND PETI

TIONER’S TIMELY MOTION TO DISMISS AP

PEAL SHOULD HAVE BEEN GRANTED

The Court of Appeals, Judge Whitehurst dissenting,

held that Rule 37 (a) (2) applies only to criminal ap

peals “after verdict or finding of guilt . . . or plea of

guilty,’’ citing Nye v. United States, 1941, 313 U. S. 28,

43-44. Therefore, the Court held, that Defendants’ notice

of appeal was timely, even though filed sixteen days after

entry of the remand order. Petitioner respectfully main

tains that this was erroneous.

(a) Rule 37 ( a ) ( 2 ) controls the time limit for

filing a notice of appeal in a criminal case both be

fore and after verdict.

The history of the creation of the Rules of Criminal

Procedure require application of Rule 37 (a) (2) to the

instant case.

By the Act of March 8, 1934, c. 49, 48 Stat. 399, amend

ing the Act of February 24, 1933, c. 119, 47 Stat. 904, the

Supreme Court was given authority to prescribe “rules

of practice and procedure with respect to any or all pro

ceedings after verdict, or finding of guilt by the court if

a jury has been waived, or plea of guilty in criminal

cases . .

Pusuant to the above Act, the Supreme Court by order

14

dated May 7, 1934 and entitled “Rules of Practice and

Procedure, after plea of guilty, verdict or finding of guilt,

in criminal cases brought in the District Court of the

United States and in the Supreme Court of the District

of Columbia” adopted thirteen rules as the “Rules of

Practice and Procedure in all proceedings after plea of

guilty, verdict of guilt by a jury or finding of guilt by the

trial court where a jury is waived, in criminal cases in

District Courts of the United States . . . and in all subse

quent proceedings in such cases in the United States

Circuit Court of Appeals . . . and in the Supreme Court

of the United States.” 292 U.S. 661.

The 1934 “after verdict” enabling act did not require

the Court to submit these rules to Congress; they were

therefore made effective September 1, 1934 by the Court.

Rule III of these rules, and the predecessor to Rule

37 (a) (2), provided in part that “An appeal shall be

taken within 5 days after entry of judgment of conviction

. . .” 292 U. S. 662 (emphasis added)

It is clear that Congress, under the 1934 Act, intended

the Supreme Court to promulgate only “after verdict”

rules. It is equally clear that the Supreme Court intended

the rules adopted May 7, 1934 to apply only to “after

verdict” cases. This is manifested by the title of the order

adopting the rules, and by the language of Rule III limit

ing appeals to those cases where there has been a judg

ment of conviction. If there were no judgment of con

viction there could be no appeal as the case had not yet

reached the necessary “after verdict” stage. Of course,

in such circumstances the 5 day period for appeal was

inapplicable.

By the Act of June 29, 1940, c. 445, 54 Stat. 688, Con

15

gress gave the Supreme Court the authority to prescribe

Rules of Criminal Procedure for the District Court of

the United States governing poceedings in criminal

cases prior to and including verdict, finding of guilty or

not guilty by the court, or plea of guilty. The Act also re

quired the submission of these rules to Congress. Under

the authority of this Act, the Supreme Court promulgated

Rules 1-31 and 40-60 by order dated December 26, 1944.

323 U. S. 821. The Supreme Court, by letter dated

December 26, 1944, requested the Attorney General of

the United States to report these rules to the next regular

session of Congress. 327 U. S. 823. This was done by a

Letter of Submittal from the Attorney General of the

United States to Congress, dated January 3, 1945. 327

U. S. 824. The first regular session of Congress adjourned

on December 21, 1945. The rules therefore became ef

fective on March 21, 1946 as provided by Rule 59.

By Order dated February 8, 1946 the Supreme Court

prescribed rules 32-39 pursuant to the “after verdict”

enabling Act of 1933, as amended. The Court made those

rules effective on the same date rules 1-31 and 40-60 be

came effective. The Court further ordered that both the

“prior to verdict” rules and the “after verdict” rules be

consecutively numbered and known as the Federal Rules

of Criminal Procedure, 327 U. S. 825. Rules 32-39

were not submitted to Congress. There was no need to

submit them. The 1933 Act, as amended, did not require

submission of the rules for them to become effective.

ft is obvious from the February 8, 1946 order that the

Supreme Court intended Rules 1 through 60 to serve as

a complete set of Rules to govern criminal proceedings.

This is manifested by all of the Rules becoming effective

on the same date, and by the fact that the Court titled the

16

rules as the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. If

these rules were intended to be separated into two sets,

one embracing “verdict and before verdict” proceedings

and the other “after verdict” proceeding, as Judge Tut

tle, speaking for the majority of the Court of Appeals,

advocates, it is doubtful that the court would have gone

to the difficulty of making them effective on the same day.

It is even more doubtful that the Court would order the

rules numbered consecutively or title them the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure. It seems more reasonable

to believe the court would have kept the “before verdict”

rules separate from the “after verdict” rules and titled

them as such. This reasoning is further supported by the

fact that the old rules I through XIII now replaced by

Rules 32-39 were in fact known as the “Rules of Practice

and Procedure, after plea of guilty, verdict or finding of

guilt, in Criminal Cases . . . ”

The Supreme Court had the authority under the 1933

and 1940 enabling Acts to prescribe all rules to govern

any and all proceedings in a criminal case. It is obvious

from its above described actions that this Court intended

Rules 1 through 60 to serve all criminal proceedings be

fore and after verdict, without regard to which enabling

act authorized promulgation of a particular rule.

If a distinction as to the application of Rules 1-31 and

40-60, and Rules 32-39 ever existed because the 1940 Act

required submission of the rules to Congress and the

1933 Act did not, it no longer exists. There is no merit

in the contention that Rules 32 through 39 have not

been submitted to Congress. By the Act of June 25,

1948, c. 645, 62 Stat. 683, entitled “An Act to Revise,

Codify, and Enact into Positive Law Title 18 of the

United States Code,” Congress enacted into law all sixty

17

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Rule 37 (a) (2)

is specifically incorporated by reference under Section

3732 on page 845 of that Statute. Clearly Congress in

tended the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure to apply

to all criminal proceedings, whether before or after

verdict.

Petitioner’s viewpoint is further supported by the

language of Rule 37 (a) (2), which reads as follows:

“2. Time for Taking Appeal. An appeal by a

defendant may be taken within 10 days after entry

of the judgment or order appealed from, but if a

motion for a new trial or in arrest of judgment has

been made within the 10-day period an appeal from

a judgment of conviction may be taken within 10

days after entry of the order denying the motion.

When a court after trial imposes sentence upon a

defendant not represented by counsel, the defendant

shall be advised of his right to appeal and if he so

requests, the clerk shall prepare and file forthwith a

notice of appeal on behalf of the defendant. An ap

peal by the government when authorized by statute

may be taken with 30 days after entry of the judg

ment or order appealed from” (Emphasis added)

The last sentence allows thirty days for an appeal by

the government when authorized by Statute. 18 U.S.C.

3731 (App. A, p. 66) authorized appeal by the govern

ment in criminal cases in the following instances:

(1) from a decision or judgment setting aside, or dis

missing any indictment or information, or any count

thereof;

(2) from a decision arresting a judgment of convic

tion for insufficiency of the indictment or information;

(3) from a decision or judgment sustaining a motion

in bar, when the defendant has not been put in jeopardy.

18

One and three of the foregoing are “before verdict

appeals.” The government is also authorized a “before

verdict appeal” of an order suppressing evidence in a

narcotics case and in certain internal revenue cases.

(18 U.S.C. 1404) . In fact it is the rule rather than the

exception that the government’s right to appeal is in

“before verdict” circumstances. If Rule 37 (a) (2) ap

plies only to “after verdict” situations as urged by the

Court of Appeals, why does the last sentence of the Rule

deal with “before verdict” appeals? The Court of Ap

peals’ reasoning becomes even more illogical when com

bined with their interpretation of the 1933 and 1940 en

abling Acts. Accept for the moment arguendo that Rules

32 through 39 applied only to “after verdict” rules and

that 1-31 and 40-60 applied only to “prior to and in

cluding verdict” rules. (This of course ignores the 1948

Act codifying the Rules) . Since Rule 37 (a) (2) was

promulgated under the “after verdict” enabling Act of

1933, the last sentence of the rule dealing with Appeals

by the government must be limited to “after verdict” ap

peals only. Therefore, Rule 37 (a) (2) would be a nullity

as to “before verdict” appeals as authorized by 18 U.S.C.

3731 and 18 U.S.C. 1404. Clearly such appeals are au

thorized.

In United States v. Williams (4th Cir. 1955) 227 F.2d

149, the Defendant was charged with removing and con

cealing non-tax paid whiskey. After defendant’s motion

to suppress evidence had been sustained and the indict

ment dismissed the Government appealed, but did so

more than 30 days after entry of the order. The Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal, holding:

“The order was not a final order made in a civil

proceeding, from which an appeal would lie and

from which the government would have 60 days in

19

which to take an appeal, but an order in a criminal

proceeding. . . . In so far as it (the order of the

lower court) ordered a dismissal of the indictment

in the case, it (the appeal) was not taken within 30

days and must be dismissed for that reason under

Rule 37 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.

18 U.S.C.A.” (Explanatory words added)

Petitioner’s interpretation of Rule 37 (a) (2) is

further strengthened by comparing it with its predeces

sor, Rule III. This rule allowed only for appeal . . after

entry of judgment of conviction.” Rule 37 (a) (2) al

lows appeal “. . . after entry of the judgment or order ap

pealed from, . . . ” Surely if the court had intended Rule

37 (a) (2) to apply only to “after verdict” situations it

would have retained the language, “judgment of convic

tion.” By broadening the language to “judgment or order

appealed from” the Court removed the “after verdict”

limitation. A judgment may be defined as “a decision of

a court of justice upon respective rights and claims of the

parties to an action.” (Black’s Law Dictionary, Third

Edition, 1933, page 1024) Judgments are classified ac

cording to the time or stage of the action when rendered.

(Black, supra, p. 1025). A judgment may be final or in

terlocutory. An order may be defined as “every direction

of a Court or a Judge made or entered in writing.”

(Black, supra, p. 1298) . An order may be final or inter

locutory. Therefore, the use of the general terms “judg

ment” and “order” can not be construed in Rule 37

(a) (2) as a “judgment of conviction” limiting appeal to

“after verdict” situations only.

Judge Tuttle bases his opinion for the majority of

the Court that Rule 37 (a) (2) is inapplicable on Nye v.

United States, 1941, 313 U.S. 28, 43-55. Nye is not con

trolling. It was decided before the Federal Rules of

20

Criminal Procedure were adopted. Nye was not con

cerned with Rule 37 (a) (2) but rather with its pre

decessor, Rule III, which we have seen was limited to

“after verdict” appeals. Further, Nye was an adjudication

of a criminal contempt arising out of a civil case. In

deciding that the Criminal Appeals Rules then in effect

did not apply to criminal contempt cases, the Supreme

Court held that these Rules

were adopted as the Rules of Practice and Pro

cedure in all proceedings after plea of guilty, verdict

of guilt by a jury or finding of guilt by the trial

court where a jury is waived in criminal cases (292

U.S. 661) . In this case there was no plea of guilty,

there was no verdict of guilt by a jury, and there

was no finding of guilt by the court where a jury

was waived. It is our view that the rules describe

the kinds of cases to which they are to be applied.”

This holding is correct. The words of limitation in

Rule III are “entry of Judgment of Conviction.” It is

clear from the title of these Rules and the language of

Rule III that Rule III would not apply to an appeal be

fore a judgment of conviction.

The title of the current Rules and Rule 37 (a) (2)

are void of any language limiting application to “after

verdict” cases. Following the Nye reasoning it is logical

to conclude that Rule 37 (a) (2) does apply to “before

verdict” situations since the language in the title and

Rule 37 (a) (2) limiting application to “after verdict”

appeals has been deleted.

As mentioned above, Nye was decided when Rule III

was in effect. The whole history of the promulgation of

Rule 37 (a) (2) and the Federal Rules of Criminal Pro

cedure presents such a changed picture from the factual

21

situation presented at the time of the Nye decision as to

refute any contention that it is controlling authority for

the proposition that Rule 37 (a) (2) applies only to

“after verdict” cases. Also, Nye has been interpreted

merely as standing for the proposition that the Criminal

Appeals Rules did not apply to a criminal contempt case.

See Moore v. United States (10 Cir. 1945), 150 F.2d 323,

cert. den. 326 U.S. 740; United States v. Lederer (7 Cir.

1943) 139 F. 2d 861. This interpretation finds strength

in the Act of November 21, 1941, C. 492, 55 Stat. 776

which provided that the rules would apply to criminal

contempt proceedings.

(b) Rules 54 (b) (1 ) and 59 of the Federal Rules

of Criminal Procedure require application of Rule

37 (a) (2 ) to the instant case.

Rule 54 (b) (1) reads as follows:

“Removal Proceedings These rules apply to

criminal prosecutions removed to the district courts

of the United States from state courts and govern

all procedures after removal, except that dismissal

by the attorney for the prosecution shall be governed

by state law.” (Emphasis added)

The instant case is a criminal prosecution, begun in

the Superior Court of the State of Georgia. It was re

moved by the defendants to the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Georgia. Clearly, then

Rule 54 (b) (1) applies. The phrase “govern all proce

dure after removal” must include any appeal of a remand

order. A remand order can not be issued until after a

case has been removed from State to Federal Court. It

can not be said that appeal of a remand order is an ex

ception to Rule 54 (b) (1) because the rule provides for

only one exception, dismissal by the prosecuting attorney.

22

Applying the principle of Inclusio unius est exclusio al-

terius, the listing of one exception excludes all other ex

ceptions. If appeal of a remand order were to be an ex

ception of Rule 54 (b) (1), it would have been so stated

in the Rule.

The last sentence of Rule 59 states that the Rules shall

“. . . govern all criminal proceedings thereafter com

menced . . .’’ To hold that Rule 37 (a) (2) does not

apply to an appeal of a remand order in a criminal case

ignores and contradicts the specific requirement of Rule

54 (b) (1) and the general requirement of Rule 59. The

opinion of the Court of Appeals that Rule 37 (a) (2) is

not applicable flies in the teeth of Rule 54 (b) (1) and

can only circumvent Rule 59 by a finding that the pro

ceedings removing the case to Federal court was civil

rather than criminal. But the proceedings are criminal

in nature. They are made so by Rule 54 (b) (1) . They

are also made so by decisions of the court. The facts

of the instant case meet even the requirements of a

criminal proceeding set forth by Judge Tuttle in

Zacarias v. United States, 5 Cir., 1958, 261 F.2d 416. The

Court of Appeals held in that case that a motion to sup

press evidence brought after the defendant had been ar

rested, taken before a U. S. Commissioner where a com

plaint was filed against him, and bound over to the

grand jury, was incidental to the criminal proceeding al

ready commenced and pending. An indictment had not

yet been returned against the defendant. Since the mo

tion was ancillary to the criminal proceeding, it was held

to be interlocutory and not directly appealable. The ap

peal was dismissed by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The point at which a criminal proceeding begins was

more fully explored by the Fifth Circuit Court of Ap

23

peals in United States v. Koenig, 1961, 290 F.2d 166.

Here, the government was attempting to appeal from an

order sustaining a motion to suppress evidence seized.

The Court held that the government could not appeal be

cause . . . “an order to suppress has no finality because

it does not of itself terminate the criminal proceedings”.

Certainly removal of a criminal case from State to Federal

court does not terminate the criminal proceedings. The

Supreme Court of the United States granted certiorari in

Koenig and decided it together with DiBella v. United

States, 1962, 369 U. S. 121. The Court said in part, at

page 128:

“. . . ‘the final judgment rule is the dominant rule in

federal appellate practice’. 6 Moore, Federal Practice

(2d ed. 1953) 113. Particularly is this true of

criminal prosecutions. See, e.g., Parr v. United

States, 351 U.S. 513, 518-521. Every statutory excep

tion is addressed either in terms or by necessary

operation solely to civil actions. Moreover, the de

lays and disruptions attendant upon intermediate

appeal are especially inimical to the effective and

fair administration of the criminal law. The Sixth

Amendment guarantees a speedy trial. Rule 2 of

the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure counsels

construction of the Rules ‘to secure simplicity in

procedure, fairness in administration and the elimin

ation of unjustifiable expense and delay’; Rules

39 (a) and 50 assign preference to criminal cases on

both trial and appellate dockets”.

# * * * #

“We should decide the question here — we are

free to do so — with due regard to historic principle

and to the practicalities in the administration of

criminal justice. An order granting or denying a

pre-indictment motion to suppress does not fall

within any class of independent proceedings other

24

wise recognized by this Court, and there is every

practical reason for denying it such recognition. To

regard such a disjointed ruling on the admissibility

of a potential item of evidence in a forthcoming

trial as the termination of an independent proceed

ing with full panoply of appeal and attendant stay,

entails serious disruption to the conduct of a crim

inal trial.8 The fortuity of a preindictment motion

may make of appeal an instrument of harassment,

jeopardizing by delay the availibility of other es

sential evidence.” (at page 129).

“Presentations before a United States Commis

sioner, GoBart Co. v. United States, 282 U.S. 344,

352-354, as well as before a grand jury, Cobbledick

v. United States, 309 U. S. 323, 327, are parts of the

federal prosecutorial system leading to a criminal

trial. Orders granting or denying suppression in the

wake of such proceedings are truly interlocutory,

for the criminal trial is then fairly in train. When at

the time of ruling there is outstanding a complaint,

or a detention or release on bail following arrest, or

an arraignment, information, or indictment — in

each such case the order on a suppression motion

must be treated as ‘but a step in the criminal case

preliminary to the trial thereof’. Cogen v. United

States, 278 U. S. 221, 227. Only if the motion is

solely for return of property and is in no way tied

to a criminal prosecution in esse against the movant

can the proceedings be regarded as independent.

See Carroll v. United States, 354 U. S. 394, 404 n.

17; In re Brenner, 6 F. 2d 425 (C.A. 2d Cir. 1925) .”

Petitioner urges that the instant case had proceeded so

8“It is evident, for example, that the form of independence has

been availed of on occasion to seek advantages acquired by the

rules governing civil procedure, to the prejudice of proper ad

ministration of criminal proceeding, e.g., Green v. United States,

296 F 2d 841, 843-855 (C. A. 2d Cir., 1961) (extended time for

a p p e a l ) .

25

far within the doctrine of DiBella, Koenig and Zacarias,

supra, that the removal to federal court was but a step in

the criminal train. The defendants had already passed

the steps of arrest, commitment hearing and indictment.

The State of Georgia was proceeding at full speed to give

the defendants their day in court when the cases were re

moved to federal court. The first case was to be tried on

February 17, 1964 (R. 4), the same day the removal

petition was filed. Removal to federal court does not dis

miss or dispense with prosecution. It merely changes the

forum. No independent right is involved and the de

fendants can not qualify the removal as not being tied to

the prosecution in esse as required by DiBella. In fact

the Supreme Court has held that removal is merely a step

in a criminal proceeding, therefore interlocutory and not

directly appealable. In Parr v. United States, 351 U. S.

513 (1956) , the defendant was indicted in one division

of the Federal District Court and that court granted his

motion to transfer the case to another division, on the

ground that local prejudice would prevent a fair trial in

the division where he was indicted. The government

then obtained a new indictment for the same offenses in

another district and moved in the first court for a dismis

sal of the first indictment. The dismissal was granted and

the defendant appealed. The Court stated, in holding

that the order was not appealable because it was not

final, that:

“ ‘Final judgment in a criminal case means sen

tence. The sentence is the judgment.’ Berman v.

United States, (302 U. S. 211). And viewing the

two indictments together as a single prosecution . . .

the petitioner has not yet been tried, much less con

victed and sentenced. The order dismissing the

(first) indictment was but an interlocutory step in

26

this prosecution and its review must await the con

clusion of the ‘whole matter litigated’ between the

Government and the petitioner (defendant) —name

ly ‘the right to convict the accused of the crime,

charged in the indictment’. Heike v. United States,

217 U.S. 423, at p. 429” (Explanatory words added).

The Court further held that since the order dismissing

the first indictment was but a “ ‘step toward final dis

position of the merits of the case’ ” it would “ ‘be merged

in the final judgment;’” citing Cohen v. Beneficial In

dustrial Loan Corp., 337 U. S. 541, at p. 546.

The Supreme Court added (351 U. S. at 519) :

“The lack of an appeal now will not deny effective

review of a claim fairly severable from the context

of a larger litigious process. Sivift & Company Pack

ers v. Compania Columbiana de Caribe, (339 U.S.

684.) at p. 689. True, the petitioner will have to

hazard a trial under the Austin (second) indictment

before he can get a review of whether he should

have been tried in Laredo under the Corpus Christi

(first) indictment, but ‘bearing the discomfiture

and cost of a prosecution for crime even by an in

nocent person is one of the painful obligations of

citizenship.’ Cobbledick v. United States, supra, at

p. 325.” (Explanatory words added)

See also, Chicago etc. R. Co. v. Roberts, 1891, 141 U. S.

690 which held that a remand order was not appealable

because it was not a final order. In fact under 28 U. S. C.

1447 (d) no remand order was appealable until amended

by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 giving for the first time

the right to appeal a remand order in civil and criminal

cases involving civil rights. Based upon the foregoing the

removal must be viewed as but a part of the criminal

proceeding. If the Defendants had been denied the right

to appeal the remand order of the District Court an ef-

fective review could still have been had on appeal on the

merits of the case.

If the removal of the instant case to federal court was

part of the criminal proceeding, should not the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure apply to its appeal?

The Petitioner unequivocally contends that these

principles of law, and therefore Rule 37 (a) (2) must

be applied to the case at hand.

Judge Tuttle, in holding that Rule 37 (a) (2) is in

applicable does not state what Rule or statute does govern

the time limit for filing the Defendants’ notice of ap

peal. Surely he would not advocate a limitless time to

appeal. Therefore he must have applied either Rule 73

(a), Fed. R. Civil P. or Section 2107, Title 28, U. S. C.

to hold this appeal timely, it being filed sixteen days

after the remand order.

28 U. S. C. 2107 reads as follows:

2107 Time for appeal to courts of appeals.

“Except as otherwise provided in this section, no

appeal shall bring any judgment, order or decree in

an action, suit or proceeding of a civil nature before a

Court of Appeals for review unless notice of appeal

is filed within 30 days after entry of such judgment,

order or decree.” . . . (As amended May 24, 1949,

c. 139, 107, 108, 63 Stat. 104) (Emphasis added)

The rule expressly provided that the action must be of

a civil nature. Following the rulings of Parr, DiBella,

Koenig, and Zacarias, all supra, the Petitioner respect

fully urges that the instant case is not of a civil nature

and therefore neither Rule 73 (a) , Fed. R. Civil P. nor

28 U. S. C. 2107 can apply.

Forgetting for the moment Rule 37 (a) (2) of the

Criminal Rules, Rule 73 (a) of the Civil Rules and 28

U. S. C. 2107, should the Rules of Civil Procedure and

the Rules of Criminal Procedure be intermingled at

all? Counsel for Petitioner think not,

“At times in our system the way in which courts

perform their function becomes as important as what

they do in the result. In some respects matters of

procedure constitute the very essence of ordered

liberty under the Constitution.

* # * *

“I do not think the Constitution contemplated

that there should be in any case an admixture of civil

and criminal proceedings in one. Such an idea is

foreign to its spirit.

“The founders did not command the impossible.

They could not have conceived that procedures so

irreconcilably inconsistent in many ways could be

applied simultaneously. Nor was their purpose to

create any part of judicial power,. . . wholly at large,

free from any constitutional limitations or to pick

and choose between the conflicting civil and criminal

procedures and remedies at will. Much less was it

to allow mixing civil remedies and criminal punish

ments in one lumped form of relief, indistinguish-

ably compounding them and thus putting both in

unlimited judicial discretion, with no possibility of

applying any standard of measurement on review”.

Mr. Justice Rutledge, dissenting in United States

v. United Mine Workers of America, 1947, 330 U. S.

258, pp 363-365.

To hold that Rule 37 (a) (2) does not apply to the

case at hand contravenes every ruling of the Supreme

Court and the purpose for creating the Federal Rules of

Criminal Procedure. It would cause chaos in the orderly

and impartial administration of justice in criminal cases.

29

(c) An appeal not timely filed confers no juris

diction upon the Court of Appeals

Applying Rule 37 (a) (2), the Defendants’ appeal

was not timely filed. Defendants’ notice of appeal was

filed sixteen days after entry of the remand order. A

notice of appeal in a criminal case not filed within the

10 day time limit required by Rule 37 (a) (2) confers

no jurisdiction upon the Court of Appeals. United States

v. Robinson, 1960, 361 U. S. 220; Berman v. United

States, 1964, 378 U. S. 530.

Nowhere in this record is this Honorable Court shown

any reason or excuse for the late filing of the notice of

appeal. One can only surmise that these defendants, or

their counsel, have slept on their right to appeal. Realiz

ing too late that the 10 day time limit of Rule 37 (a) (2)

had passed before their notice of appeal was filed, the

Defendants are trying frantically to justify the sixteen

day interval as proper and to “stay in court”. However,

even they did not urge the novel construction given Rule

37 (a) (2) by the Court of Appeals.

For the foregoing reasons, the Court of Appeals erred

in holding this appeal to be timely. Therefore, Peti

tioner’s timely Motion to Dismiss Appeal should have

been granted, as District Judge Whitehurst, sitting as a

member of the Fifth Circuit panel hearing this appeal,

has insisted in dissenting opinions both on the merits and

on the petition for rehearing.

30

II. THE PETITION FOR REMOVAL DOES NOT

SET OUT ANY VALID GROUND FOR REMOVAL.

(a) There is nothing in the Petition for Removal

to warrant the exercise of Federal jurisdiction.

Petitioner respectfully maintains that the Petition for

Removal is completely devoid of any valid ground for

removal of these criminal prosecutions from State to Fed

eral court. What it does not contain is more important

than the skimpy allegations set forth. The Petition for

Removal (R. 1-5) does not allege (1) that any statute

or law of the State of Georgia is unconstitutional (2)

that any civil right, or the enforcement thereof, of the

Defendants is destroyed by any statute of the State of

Georgia or by its Constitution (3) that any statute of

the State of Georgia, or its Constitution creates an in

ability on the part of Defendants to enforce in the

Courts of Georgia their equal civil rights under the

United States Constitution.

Furthermore, there is a complete failure in the Peti

tion for Removal to set out sufficient facts to support a

removal. Only bare allegations are made that certain

Defendants sought service, food, entertainment and

comfort in certain restaurants and hotels in Atlanta,

Georgia, and were arrested pursuant to Georgia Code

Annotated 26-3005. Then appears a mere conclusionary

allegation that these arrests were effected for the sole

purpose of perpetuating customs and usages of the City

of Atlanta with respect to serving and seating Negroes,

and white persons accompanying Negroes, in places of

public accommodation upon a racially discriminatory

basis. They allege, in a pure conclusion, that they cannot

enforce their rights in the Georgia courts, but do not

allege a single fact, showing why they cannot do so. They

31

do not specify one single Georgia law which prevents

enforcement of their rights in the State courts. More

over, they do not allege that any judge, law enforcement

officer, prosecuting attorney, or other officer of the State

of Georgia has in any way violated any of their civil

rights, or prevented them from asserting any of such

rights. In other words, there is no allegation of improper

conduct by any State official. Even if such allegations

were contained in the Petition for Removal, many fed

eral decisions hold that such allegations would not justify

removal. This woefully inadequate removal petition was

everything that the District Court had before him when

he considered, on his own motion as it was his duty

to do, the question of whether a cause for removal was

shown.

Petitioner will discuss briefly just a few of the con

trolling cases which illustrate beyond the shadow of a

doubt that this case is not removable under any possible

construction of the Petition for Removal.

In Virginia v. Rives, 1879, 100 U. S. 313, where two

Negroes removed their pending State trial for murder

to federal court, and the State of Virginia filed a petition

for mandamus to the United States Supreme Court to

force the remand of said cases, Justice Strong said, in

part, for the Court, in granting the petition for man

damus:

“.. . But in the absence of constitutional or legisla

tive impediments he cannot swear before his case

comes to trial that his enjoyment of all his civil rights

is denied to him. When he has only an apprehension

that such rights will be withheld from him when his

case shall come to trial, he cannot affirm that they are

actually denied, or that he cannot enforce them. Yet

such an affirmation is essential to his right to remove

32

his case. By the express requirement of the statute

his petition must set forth the facts upon which he

bases his claim to have his case removed, and not

merely his belief that he cannot enforce his rights at

a subsequent stage of the proceedings. The statute

was not, therefore, intended as a corrective of errors

or wrongs committed by judicial tribunals in the ad

ministration of the law at the trial.” (Emphasis

added)

Virginia v. Rives, supra, holds categorically that a case

is not removable under the civil rights acts (the prede

cessor of 28 U.S.C. 1443) unless a State Constitution or

Statute on its face denies the removing defendant his

federal constitutional rights. In other words, there must

be discriminatory state legislation depriving him of those

rights before he can remove the case. Since that time,

federal courts have followed that rule without deviation

or modification. To list just a few, Petitioner cites Ken

tucky v. Powers, 1906, 201 U. S. 1; Williams v. Missis

sippi, 1898, 170 U. S. 213; Murray v. Louisiana, 1896,

163 U. S. 101; Gibson v. Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 565;

Smith v Mississippi, 1896, 162 U. S. 592; Hull v. Jackson

County Circuit Court, 6 Cir., 1943, 138 F. 2d 820; Snypp

v. Ohio, 6 Cir. 1934, 70 F. 2d 535, cert. den. 293 U. S.

563; Arkansas v. Howard, D.C. E.D. Ark., 1963, 218 F.

Supp. 626; North Carolina v. Jackson, D.C. M.D. N.C.,

1955, 135 F. Supp. 682; Hill v. Pennsylvania, D.C. W.D.

Pa., 1960, 183 F. Supp. 126; Texas v. Doris, D.C., S.D.

Texas, 1938, 165 F. Supp. 738; and Neal v. Delaware,

1880, 103 U.S. 370. Each of the foregoing was a criminal

case, and removal was sought in each under the civil

rights act.

The Kentucky v. Powers case, supra, appears to be the

last Supreme Court ruling on exactly what grounds will

authorize a removal under color of the civil rights acts,

33

and it has been followed in every instance by the lower

federal courts in the cases previously cited in this section

of this Brief. In Powers, supra, the Supreme Court said,

(201 U. S. at page 30) :

“The question as to the scope of section 641 of

the Revised Statutes again rose in the subsequent

cases of Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 386: Bush

v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 116; Gibson v. Missis

sippi, 162 U. S. 565, 581, 584, and Charley Smith v.

Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592, 600. In each of these cases

it was distinctly adjudged, in harmony with previous

cases, that the words in section 641 — ‘who is denied

or cannot enforce in the judicial tribunals of the

State or in the part of the State where such suit or

prosecution is pending, any right secured to him

by any law providing for the equal civil rights of

citizens of the United States, or of all persons within

the jurisdiction of the United States’ — did not give

the right of removal, unless the constitution or the

laws of the State in which the criminal prosecution

was pending denied or prevented the enforcement

in the judicial tribunals of such State of the equal

rights of the accused as secured by any lawr of the

United States. Those cases, as did the prior ones,

expressly held that there was no right of removal

under section 641, where the alleged discrimination

against the accused, in respect of his equal rights,

was due to the illegal or corrupt acts of administra

tive officers, unauthorized by the constitution or laws

of the State, as interpreted by its highest court. For

wrongs of that character the remedy, it was held, is

in the state court, and ultimately in the power of

this court, upon writ of error, to protect any right

secured or granted to an accused by the Constitution

or laws of the United States, and which has been

denied to him in the highest court of the State in

which the decision, in respect of that right, could

be had.”

34

Petitioner maintains that the Powers case still controls

the federal case law on this question of removability,

and that it has not been altered, modified, or watered-

down by any subsequent decision of the Supreme Court,

or any inferior federal court, except by the Fifth Circuit

in this case, and in Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347

F.2d 679, (1965) which will be discussed later in this

brief.

Thus, Petitioner has clearly shown that according to

prevailing federal case law discriminatory state legislation

which interferes with a constitutional right of defense

by the defendant must exist before a case is removable

under the civil rights acts. The Defendants’ Petition

for Removal does not allege this. The only statute they

mention is Georgia Code Annotated, 26-3005, which

simply makes it unlawful for any person who is on the

premises of another to refuse and fail to leave said prem

ises when requested to do so by the owner or other person

in charge of said premises. There is nothing discrimi

natory about that statute, and nothing which in any

manner deprives a defendant of any right of defense.

The statute on its face has application to many situations

other than racial ones. It authorizes prosecution of the

drunken visitor in one’s home, the person behaving in a

disorderly manner in one’s church, or the disreputably

dressed, boisterous customer in a store, who refuses to

leave when requested. If the gist of Defendants com

plaint is that 26-3005 is being unconstitutionally applied,

then they have no grounds for removal. Their remedy

is to defend themselves through the State courts and

then seek review by certiorari in the United States Su

preme Court.

The Court of Appeals in their opinion impliedly rec

35

ognize the lack of sufficient allegations in the removal

petition. The majority refers to “the bare bones allega

tion of the existence of a right,” and to “liberality of

pleadings under the (Civil) rules.” Circuit Judge Bell

refers in his partially concurring and partially dissenting

opinion to the removal petition as “notice type plead

ings.” In fact, the whole Court agreed to send the case

back to the District Court to allow Defendants to prove

the allegations of the removal petition, or as Judge Bell

stated “to determine just what appellants do claim.”

(R. 35)

A brief summary of the legislative history of Para

graphs (1) and (2) of 28 U.S.C. 1443, under either of

which these Defendants may attempt to justify removal

of these cases, might be profitable here. In its present

form Section 1443 sets out in two paragraphs circum

stances under which civil actions or criminal prosecutions

may be removed by the defendants to the federal district

court embracing the place wherein the case is pending.

These two types of cases are: (1) Against any person

who is denied or cannot enforce in the courts of such

State a right under any law providing for the equal rights

of citizens of the United States, or of all persons within

the jurisdiction thereof. Hereinafter in this Brief we

will refer to this Paragraph as the “denial” clause, for

the sake of brevity. (2) For any act under color of au

thority derived from any law providing for equal rights,

or for refusing to do any act on the ground that it would

be inconsistent with such law. Hereinafter we will refer

to this Paragraph as the “color of authority” clause.

The forerunner of Section 1443 was Section 3 of the

first Civil Rights Act, 14 Stat. 27 (1866) enacted under

power of the recently adopted Thirteenth Amendment

36

and prior to adoption of the Fourteenth. Section 1 of

the Act confers on all persons born in the United

States, of every race and color and without regard to

previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude

the same rights enjoyed by white persons to contract;

sue and be parties; testify; inherit, hold and dispose of

property; and to the full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of person and property,

and to be subject to like punishment, pains and penalties

and to none other.

Section 2 of the Act of 1866 made it a crime for any

person “under color of law” to deprive any person of any

right secured by the Act. Section 3 was the removal pro

vision and authorized removal of criminal and civil causes

“affecting persons who are denied or cannot enforce in

the courts . . . of the State . . . any of the rights secured

to them by the first section of the Act.” Section 3 further

authorized removal of any suit or prosecution com

menced in any State court against “any officer, civil or

military, or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment,

trespass or wrongs done or committed under color of au

thority derived from this Act . . . or for refusing to do

any act on the grounds that it would be inconsistent

with this Act.”

Thus the first part of Section 3, Act of 1866, marks

the first appearance of the “denial” clause, now Para

graph (lj of Section 1443, and the latter part of Section

3 is the predecessor of the “color of authority” clause,

now Paragraph (2) of Section 1443.

Although the Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140, added

the safeguard of the equal rights of citizens to vote, and

defined a crime for conspiracy to injure a citizen in the

37

exercise of Constitutional or statutory rights, it did not

significantly alter the removal section of the Act of 1866.

However, in the Revised Statutes of 1875 and 1878,

former Section 1 of the Act of 1866 became Title XIV,

entitled “Civil Rights”, in two sections, 1977 and 1978

which are now 42 U. S. C. 1981, 1982. The jurisdictional

proceedings, both original and on removal, became part

of Chapter 7, Title XIII, “The Judiciary”. Old Section

3 of the Act of 1866 became Section 641 (See App. A,

Page 72 for complete text) . Both the “denial” and the

“color of authority” clauses were re-worded somewhat

in Section 641, although the latter still retained the

words “against any officer, civil or military, or any other

person.”

Section 641 became Section 31, Judicial Code of 1911,

35 Stat. 1096 without any real change. However, the

1948 codification of Title 28, U. S. C. made a number

of changes. Procedural details were split off into other

Sections and structure was altered by dropping clauses

and rearranging them. The most important changes

were that the words “against any officer, etc.” were

dropped from the “color of authority” clause, and noth

ing was substituted therefor. Also, the words “arrest,

imprisonment, wrongs or trespass” in that clause were

shortened to “any act under color of authority.”

The 1948 codification of Title 28 made a significant

change in the removal right of federal officers in Section

1442. Formerly the class of persons with such removal

right had been limited to officers acting under the reve

nue laws. (Former Section 643, Title XIII; subsequently

Section 33, Judicial Code of 1911, 36 Stat. 1097.) Sec

tion 1442(a) (2) expanded this coverage to allow re

moval by any federal officer, or persons acting under him

38

for any act done under color of such office or on account

of any right claimed under any Act of Congress for the

apprehension of criminals or collection of the revenue.

With this admittedly skimpy review of the history of

present Sections 1443 (1) and (2), we will discuss four

federal decisions of very recent vintage which bear di

rectly upon the issue presented in this case. The first of

these is People of the State of New York v. Galamison,

2 Cir. 1965, 342 F. 2d 255, cert. den. 85 S. Ct. 1342

(April 26, 1965), where some sixty persons were being

prosecuted by the State of New York for acts committed

during demonstrations conducted to publicize their

grievances over “the denial of equal protection of the

laws to Negroes in the City, State, and Nation with ref

erence to housing, education, employment, police action,

etc.” (342 F. 2d at 257). The demonstrators disrupted

highway and subway traffic to the New York World’s

Fair, passed out leaflets at a public school in protest

against lack of integration, and staged a “sit-down” at

City Hall protesting the same subject. The Defendants

removed their cases to the respective federal district

courts having territorial jurisdiction, and the federal

district courts promptly remanded the cases to the New

York Courts without evidentiary hearings. (342 F. 2d

at 258) .

Before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the Ap

pellants abandoned any reliance upon the “denial” clause

of Section 1443 and relied entirely upon the second, or

“color of authority” clause. In a most thorough, exhaus

tive, and scholarly analysis of the entire history of Sec

tion 1443, Judge Friendly in the majority opinion pre-

termitted the contention of the State of New York that

Section 1443 (2) , the “color of authority” clause, is lim

39

ited to officers and persons assisting them or acting in

some way on behalf of government. But moving beyond

that contention, Judge Friendly held that the cases were

not removable from state to federal district courts under

the “color of authority” clause, stating in part:

“ . .. We begin by returning to the text we must

construe. We have agreed with appellants that Sec.

1443 (2) affords a ground for removal separate from

Sec. 1443 (1) , and We are henceforth assuming, argu

endo, that Sec. 1443 (2) is not limited to officers

or persons acting at their instance or on their behalf.

it