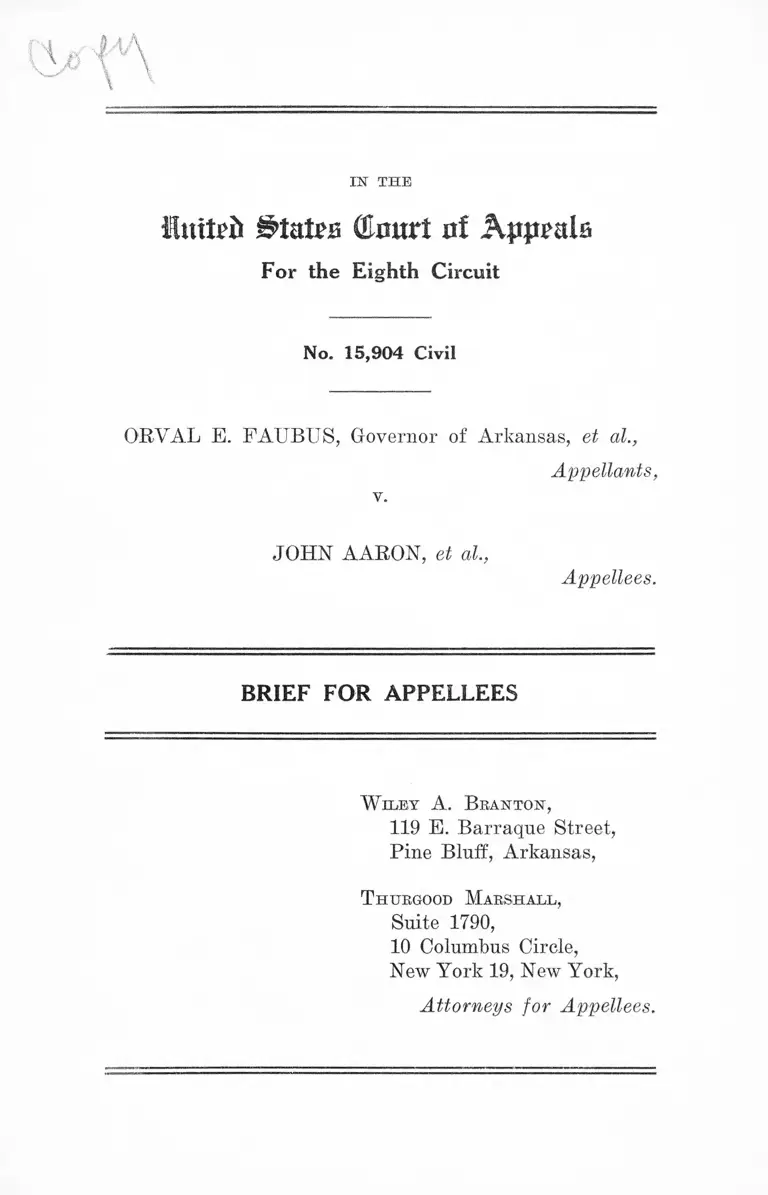

Faubus v. Aaron Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Faubus v. Aaron Brief for Appellees, 1958. 4ef02c7e-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6ca44bfc-47f0-41f2-8a4a-82423cdf81dd/faubus-v-aaron-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Hiutth States (Eaurt rtf Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 15,904 Civil

ORVAL E. FAUBUS, Governor of Arkansas, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

JOHN AARON, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

W iley A. B ran ton ,

119 E. Barraque Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

Thttrgood Marshall,

Suite 1790,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York,

Attorneys for Appellees.

I N D E X

PAGE

Table of Cases ............................................................... i

Argument:

Appellants’ Point I ............................................. 1-3

Appellants’ Point II ............................................ 3-6

Appellants’ Point III ........................................... 6-1

Table of Cases

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361, affirming 143 F.

Supp. 855 ..................................................................... 3

A. B. Dick Co. v. Marr, 2 Cir. 1952, 191 F . 2d 498.. 3, 4, 5

Barnes v. United States, 9 Cir. 1956, 241 F. 2d 252 .. 2

Baskin v. Brown, 4 Cir. 1949, 174 F. 2d 391 .......... 3

Beecher v. Federal Land Bank, 9 Cir. 1945, 153 F. 2d

987 ................................................................................. 2

Berger v. United States, 1921, 255 U. S. 2 2 .............. 2

Cox v. McNutt, S. D. Ind., 1935, 12 F. Supp. 355 . . . . 6

Craven v. United States, 1 Cir. 1927, 22 F. 2d 605 2

Dakota Coal Co. v. Fraser, 8 Cir. 1920, 267 F. 130 6

Durkin v. Pet Milk Co., W. D. Ark., 1953, 14 F. R. D.

375 ......... 4

Eisler v. United States, 1948, 83 U. S. App. D. C. 315,

170 F. 2d 273 ................................................. 2

Ex parte American Steel Barrel Co., 1913, 230 U. S.

35 ................................................................................... 2

Ferrari v. United States, 9 Cir. 1948, 169 F . 2d 353 .. 3

Hazel-Atlas Class Co. v. Hartford Empire Co., 1944,

322 U. S. 238 ............................................................. 5

Helmbright v. John A. Gebelein, Inc., D. Md. 1937,

19 F. Supp. 621 ......................................................... 4

11

Howard v. Illinois Central E. Co., 1908, 207 U. S. 463 4

Hurd v. Letts, 1945, 80 U. S. App. D. C. 233,152 F. 2d

121 ................................................................................. 1

In re Linahan, 2 Cir. 1943, 138 F. 2d 650 .................. 2

In re St. Louis Institute of Christian Science, 1887,

27 Mo. App. 633 ......................................................... 4

Jewel Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local 6167, Etc., W. D. Va.

1943, 3 F. E. D. 2 5 1 ..................................................... 4

Joyner v. Browning, W. D. Tenn., 1939, 30 F. Supp.

512 ................................................................................. 6

Keown v. Hughes, 1 Cir. 1932, 54 F. 2d 1027 .............. 2

Kind v. Markham, S. D. N. Y. 1945, 7 F. E. D. 265 .. 4

Littleton v. De Lashmutt, 4 Cir. 1951, 188 F. 2d 973 3

Loew’s, Inc. v. Cole, 9 Cir. 1950, 185 F. 2d 641 . . . . 2

Miller v. Rivers, M. D. Ga. 1940, 31 F. Supp. 540 .. 6

Minnesota & Ontario Paper Co. v. Molyneaux, 8 Cir.

1934, 70 F. 2d 545 ..................................................... 2

Morse v. Lewis, 4 Cir. 1932, 54 F. 2d 1027 .............. 2

Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 1903, 191

U. S. 555 ..................................................................... 4

O ’Malley v. United States, 8 Cir. 1942, 128 F. 2d

676 ................................................................................. 3

Phillips v. United States, 1941, 312 U. S. 246 .......... 6

Power Mercantile Co. v. Olson, D. Minn., 1934, 7

F. Supp. 865 ................................................................. 6

Price v. Johnson, 9 Cir. 1942, 125 F. 2d 806 .......... 1

R. C. Tway Coal Co. v. Glenn, W. D. Ky., 1935, 12

F. Supp. 570 ............................................................... 4

Refior v. Lansing Drop Forge Co., 6 Cir., 1942, 124

F. 2d 440 ..................................................................... 2

Robinson v. Lee, C. C. S. C., 1903,122 F. 1010.......... 4

Root Refining Co. v. Universal Oil Products Co., 3

Cir., 1948, 169 F. 2d 514 ......................................... 3

PAGE

Ill

Scott v. Beams, 10 Cir., 1941,122 F. 2d 777 ................ 2

Sterling v. Constantin, 1932, 287 U. S. 378 ................ 6

Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olson, D. Minn., 1936, 13

F. Supp. 384 ............................................................... 6

Tucker v. Kerner, 7 Cir., 1950, 186 F. 2d 7 9 .......... 3

United States v. Onan, 8 Cir., 1951, 190 F. 2d 1 . . . . 2

United States v. Pendergast, W. D. Mo., 1941, 39

F. Supp. 189 ............................................. 3

Universal Oil Products Co. v. Boot Refining Co.,

1946, 328 U. S. 575 ..................................................... 4, 5, 6

Whitney v. Randall, 1937, 58 Idaho 49, 70 P. 2d

384 .'............................................................................... 4

Wilkes v. United States, 9 Cir., 1935, 80 F . 2d 285 .. 3

PAGE

IN THE

iluttcii States (Jkmrt of Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 15,904 Civil

•o-

Obval E. F a u b u s , Governor of Arkansas, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

John A abon, et al.,

--------------o—-----------

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

I

Appellants’ first contention is that the District Judge

erred in striking their affidavit of prejudice and in refusing

to disqualify himself because of bias. Assuming arguendo

that their affidavit was filed with reasonable promptitude,

i.e., good cause was shown for their failure to file it within

the statutory period, and accepting appellants’ own state

ment of facts in support of the allegation of prejudice,

appellees submit that the application for recusation was

legally insufficient under 28 U. S. C. A. § 144 and without

merit.

According to the terms of this statute, “ prejudice”

which requires recusation must he personal; judicial bias

and impersonal prejudice are not within its ambit. Price

v. Johnson, 9 Cir., 1942, 125 F. 2d 806, 811, cert, denied,

1942, 316 U. S. 677; Hurd v. Letts, 1945, 80 U. S. App.

D. C. 233, 152 F. 2d 121; Loew’s, Inc. v. Cole, 9 Cii\, 1950,

185 F. 2d 641. See Eisler v. United States, 1948, 83 U. S.

App. D. C. 315, 170 F. 2d 273, 278, and the cases there

cited, cert, dismissed, 1949, 335 U. S. 883. The question

of legal sufficiency, therefore, turns on whether the affidavit

of prejudice asserts facts from which a sane and reasonable

mind might infer personal bias or prejudice against the

affiants, or in favor of the opposite parties, by reason of

which the presiding judge is unable to exercise his func

tions in the case. Ex parte American Steel Barrel Co.,

1913, 230 U. S. 35, 43-44; Berger v. United States, 1921,

255 U. S. 22, 23; Keown v. Hughes, 1 Cir., 1920, 265 F.

572, 577. Cf. Morse v. Lewis, 4 Cir., 1932, 54 F. 2d 1027,

1032.

The facts and reasons assigned for the prejudice alleged

by appellants in this case suggest that they “ entertain a

fundamentally false notion of the prejudice which dis

qualifies a judicial officer.” In re Linahan, 2 Cir., 1943,

138 F. 2d 650, 651. First, the statement that the District

Judge conferred privately with counsel for the United

States is not a fact, of itself, showing bias or prejudice

in civil as well as criminal cases. Compare Scott v. Beams,

10 Cir., 1941, 122 F. 2d 777; United States v. Onan, 8 Cir.,

1951, 190 F. 2d 1; Barnes v. United States, 9 Cir., 1956,

241 F. 2d 252 (civil litigation), with Craven v. United

States, 1 Cir., 1927, 22 F. 2d 605, cert, denied, 1928, 276

U. S. 627 (criminal prosecution).

Similarly, it is well settled that the bias or prejudice

which can be urged against the District Judge must be

based upon something other than rulings in the case, Ex

parte American Steel Barrel Co., supra, at p. 43; Berger

v. United States, supra, at p. 31; Morse v. Lewis, supra,

at p. 1031; Minnesota & Ontario Paper Co. v. Molyneaux,

8 Cir., 1934, 70 F. 2d 545, 547; Befior v. Lansing Drop

Forge Co., 6 Cir., 1942, 124 F. 2d 440, 444-445; Beecher

v. Federal Land Bank, 9 Cir., 1945, 153 F. 2d 987, 988;

Littleton v. De Lashmutt, 4 Cir., 1951, 188 F. 2d 973, 975,

or at the trial of factually related proceedings. Wilkes v.

United States, 9 Cir., 1935, 80 F. 2d 285, 289; Ferrari v.

United States, 9 Cir., 1948, 169 F. 2d 353; Tucker v. Kerner,

7 Cir., 1950, 186 F. 2d 79, 83-84. “ Judges may, and indeed

must, make rulings as matters present themselves, and,

having done so, are not subject to a charge of prejudice.”

O’Malley v. United States, 8 Cir., 1942, 128 F. 2d 676, 685,

reversed on other grounds, Pendergast v. United States,

1943, 317 U. S. 412.

Finally, appellants’ statements that the District Judge

derived a prejudgment of the merits of this case and

acquired a personal bias from reports furnished by the

United States Attorney and the Federal Bureau of Investi

gation—in the course of ancillary proceedings for the

purpose of rendering complete justice between the original

parties in Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361, affirming 143

F. Supp. 855—are without merit. United States v. Pender

gast, W. D. Mo., 1941, 39 F. Supp. 189, 191, affirmed

O’Malley v. United States, supra, at pp. 681-682. See

A. B. Dick Co. v. Marr, 2 Cir., 1952, 191 F. 2d 498; Root

Refining Co. v. Universal Oil Products Co., 3 Cir., 1948,

169 F. 2d 514.

In sum, as Chief Judge Parker concluded in Baskin

v. Brown, 4 Cir., 1949, 174 F. 2d 391, 394: ‘ ‘ The facts set

forth in this affidavit * * * show no personal bias on the

part of the judge against any of the defendants, but, at

most, zeal for upholding the rights of Negroes under the

Constitution and indignation that attempts should be made

to deny them their rights. A judge may not be disqualified

merely because he believes in upholding the law # *

II

Appellants next contend that the trial court erred in

overruling their motion to dismiss the pleading filed by

the law officers of the United States as amici curiae. In

4

short substance the question presented is whether the Dis

trict Judge should or should not have received and con

sidered the petition of the amici, suggesting that appellants

be added as parties defendant and that they be enjoined

from obstructing or interfering with the execution and

effectuation of orders previously entered in this ease so as

to protect the integrity of the judicial process of the courts

of the United States and maintain the due administration

of justice. On this question, appellants offer several propo

sitions. None are grounds for reversal; appellants’ whole

contention, in our view of the applicable law, is clearly

without merit.

For the first proposition, it is said that the status of the

Attorney General appearing solely as amicus curiae is not

sufficient to justify the aggressive act of filing the petition.

But this proposition is not substantial in view of the dis

tinction which can be drawn between amici curiae, so

labeled, as in the instant case, who have been invited by

the court on its own initiative to perform specific services

for it, and those who merely represent interested clients.

The latter ordinarily cannot file a pleading in a cause.

That the former may, we think, is clear from the language

in Universal Oil Co. v. Root Refining Co., 1946, 328 U, S.

575, 580, 581; A. R. Dick Co. v. Marr, 2 Cir., 1952, 197 F.

2d 498, 502, cert, denied, 344 U. S. 905. And see, for

example, Hoivard v. Illinois Central R. Co., 1908, 207 U. S.

463, 490; Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 1903,

191 U. S. 555, 556; Durkin v. Pet Milk Co., W. D. Ark.,

1953, 14 F. R. D. 375; Kind v. Markham, S. D. N. Y., 1945,

7 F. R. D. 265; R. C. Tway Coal Co. v. Glenn, W. D. Ky.,

1935, 12 F. Supp. 570; Jewel Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local

6167, etc., W. D. Va., 1943, 3 F. R. D. 251; In re St. Louis

Institute of Christian Science, 1887, 27 Mo. App. 633;

Whitney v. Randall, 1937, 58 Idaho 49, 70 P. 2d 384;

cf. Helmbright v. John A. Gebelein, Inc., D. Md., 1937, 19

F. Supp. 621; Robinson v. Lee, C. C. S. C., 1903, 122 F.

1010. Furthermore, in private litigation such as this, it

is primarily the function of the law officers of the United

States, serving as amici, to protect the public interest in

the agencies of public justice, the administration of justice

and the integrity of judicial processes. See Universal Oil

Co. v. Root Refining Co., supra, at p. 581; A. B. Dick Co.

v. Marr, supra, at 502. Cf. Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. v. Hart

ford Empire Co., 1944, 322 U. S. 238, 246, where in con

nection with a similar affront to judicial processes the

Supreme Court said:

This matter does not concern only private parties.

There are issues of great moment to the public * * *.

Furthermore, the tampering with the administration

of justice in the manner indisputably shown here

involved far more than an injury to a single litigant.

It is a wrong against the institutions set up to

safeguard the public * * *. Surely it cannot be that

preservation of the integrity of the judicial process

must always wait upon the diligence of litigants.

The public welfare demands that the agencies of

public justice be not so important * * *.

This brings us to appellants’ second proposition, i.e.,

that the petition was improperly allowed to be filed under

Rules 15(d) and 21 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

This proposition is untenable. For federal courts have

‘ ‘ inherent power” to “ effectively” vindicate their honor

and, as Mr. Justice Frankfurter put it in the Universal

Oil Products Co. case, supra, at p. 580: “ Accordingly,

a federal court may bring before it by appropriate means

all those who might be affected by the outcome of its

investigation.” The appropriate, if not the only, means

for filing the supplemental complaint and adding appel

lants as parties plaintiff were Rules 15(d) and 21. More

over, although appellants choose to gloss over it, the

original plaintiffs in the case had also moved for leave

to file a supplemental complaint and add additional parties

(R. 10). Finally, here, unlike the lower court in the

8

Universal Oil Products case, all of “ the usual safeguards

of adversary proceedings’ ’ were observed.

There is no need to speculate as to appellants’ third

proposition; it is clearly without support. The instant

action is not a suit against the state but against state

officers acting illegally; and it is frivolous to contend that

the District Court lacked jurisdiction. See Sterling v.

Constantin, 1932, 287 U. S. 378; Phillips v. United States,

1941, 312 U. S. 246; Dakota Coal Co. v. Fraser, 8 Cir.,

1920, 267 F. 130; Miller v. Rivers, M. D. Ga., 1940, 31 F.

Supp. 540, reversed on non-jurisdictional grounds, 1940, 112

F. 2d 439; Joyner v. Browning, W. D. Tenn., 1939, 30 F.

Supp. 512; Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olson, D. Minn., 1936,

13 F. Supp. 384; Cox v. McNutt, S. D. Ind., 1935, 12 F.

Supp. 355; Power Mercantile Co. v. Olson, D. Minn., 1934,

7 F. Supp. 865.

I I I

Appellants’ third contention is that the pleadings in

this matter required the convening of a statutory district

court of three judges pursuant to 28 U. S. C. A. $ 2281.

With numerous decisions squarely against this contention,

appellees submit that appellants’ counsel misunderstand the

components of three-judge court procedure.

Here, as in Phillips v. United States, 1941, 312 U. S.

246, only restraint of executive action was sought ; there

was no attack on the constitutionality of state statute.

Moreover, in the words of Mr. Justice Frankfurter, speak

ing for the Supreme Court in the Phillips case, at 253-254:

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378, 53 S. Ct.

190, 77 L. Ed. 375, which is invoked as a precedent,

was a very different case. There martial law was

employed in support of an order of the Texas Rail

road Commission limiting production of oil in the

East Texas field. The Governor was sought to

7

be restrained as part of the main objective to enjoin

“ the execution of an order made by an administra

tive * * * commission,’ ’ and as such was indubitably

within § 266 [now § 2281].

W herefore, for the reasons stated above, appellees

submit that the judgment appealed from should be affirmed.

W iley A. Brauton,

119 E. Barraque Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

Thurgood Marshall,

Suite 1790,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York 19, New York,

Attorneys for Appellees.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 54 Lafayette Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320