Maxwell v Bishop Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

62 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v Bishop Brief for Petitioner, 1968. 54155a59-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6cc0a752-255a-4da0-b687-60d9b1a46400/maxwell-v-bishop-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

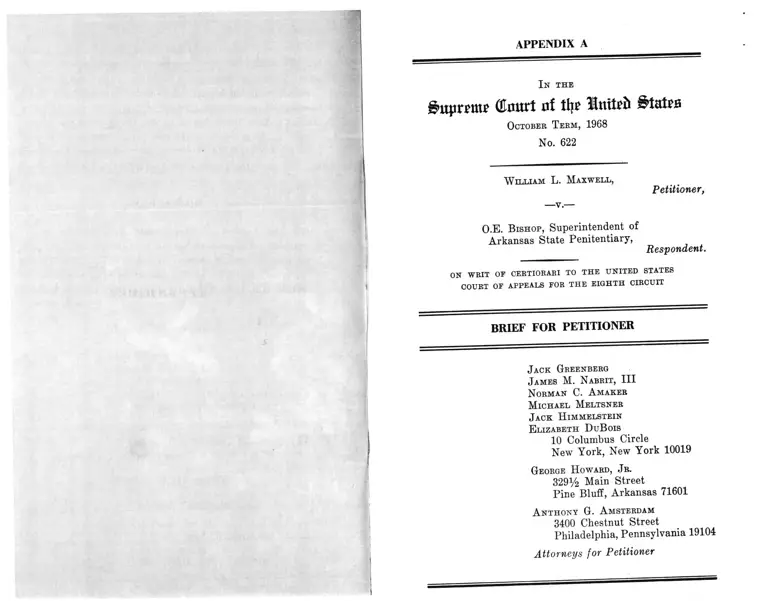

APPENDIX A

I n the

(Emtrt af tlji' Mtutefr States

October T erm, 1968

No. 622

W illiam L. M axwell,

Petitioner,

— v.—

O.E. B ishop, Superintendent of

Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

M ichael M eltsner

J ack H immelstein

E lizabeth D uB ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

George H oward, Jr.

329V2 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

I

I

I N D E X

Opinions Below ...................................................................... ^

9Jurisdiction ............................................................................... *

Questions Presented .............................................................. ^

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions In vo lved ........ 3

0

Statement ...................................................................................

Summary of Argument .......................................................... ®

A rgument

Introduction: The Fact and Implications o f

Arbitrary Capital Sentencing ................................. H

I. Arkansas’ Practice o f Allowing Capital Trial

Juries Absolute and Arbitrary Power to Elect

Between the Penalties o f Life or Death for the

Crime o f Rape Violates the Rule o f Law Basic

to the Due Process Clause ...... ..................... -....... 24

A. The Power Given Arkansas Juries is E s

sentially Lawless ................................................. 27

B. The Grant of Lawless Power in Capital

Sentencing is Unconstitutional........................ 45

II. Arkansas’ Single-Verdict Procedure for the

Trial of Capital Cases Violates the Constitution 66

Conclusion ....................................................................................

PAGE

79

11

A ppendix A

Evidence .and Findings Below Relating to Racial

Discrimination by Arkansas Juries in the Exer

cise o f Their Discretion to Sentence Capitally

for the Crime o f Rape .............................................

A ppendix B

Available Information Relating to the Propor

tion o f Persons Actually Sentenced to Death,

Among Those Convicted o f Capital C rim es....... 24a

A ppendix C

Manner of Submission o f the Death-Penalty

Issue at Petitioner Maxwell’s Trial .................... 35a

PAGE

in

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: PAGE

Alford v. State, 223 Ark. 330, 266 S.W.2d 804 (1954)

28, 30, 69

Allison v. State, 204 Ark. 609, 164 S.W.2d 442 (1942) 31

Amos v. State, 209 Ark. 55, 189 S.W.2d 611 (1945) .... 69

Andrews v. United States, 373 U.S. 334 (1963) ............ 71

Ball v. State, 192 Ark. 858, 95 S.W.2d 632 (1936) ........ 31

Baxstrom v. Herrold, 383 U.S. 107 (1966) .................. 45,53

Behrens v. United States, 312 F.2d 223 (7th Cir. 1962),

aff’d, 375 U.S. 162 (1963) ............................................. 71,72

Bevis v. State, 209 Ark. 624, 192 S.W.2d 113 (1946) .... 68

Bieard v. State, 189 Ark. 217, 72 S.W.2d 530 (1934) .... 68

Black v. State, 215 Ark. 618, 222 S.W.2d 816 (1949) -.3 1 , 68

Blake v. State, 186 Ark. 77, 52 S.W.2d 644 (1 9 3 2 ).......... 30

Bonds v. State, 240 Ark. 908, 403 S.W.2d 52 (1966) ..... 69

Boone v. State, 230 Ark. 821, 327 S.W.2d 87 (1959) ..... 29

Boykin v. Alabama, O.T. 1968, No. 642 ................7,12, 20, 22

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) ........................ 25, 27

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ...... 25

Browning v. State, 233 Ark. 607, 346 S.W.2d 210 (1961) 69

Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123 (1968) ..............36, 76

Burgett v. Texas, 389 U.S. 109 (1967) ............................ 75

Burns v. State, 155 Ark. 1, 243 S.W. 963 (1922) ........28, 30

Carson v. State, 206 Ark. 80,173 S.W .2d 122 (1943) —. 31

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940) ................. ...34, 53

Cheney v. State, 205 Ark. 1049, 172 S.W.2d 427 (1943) 31

Clark v. State, 135 Ark. 569, 205 S.W. 975 (1918) ........ 69

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445 (1927) ................ 47

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196 (1948) .............-.............. 49

Coleman v. United States, 334 F.2d 558 (D.C.Cir. 1964) 72

IV

PAGE

Cook v. State, 225 Ark, 1003, 287 S.W.2d 6 ( 1 9 5 6 , .... 31

Couck v. United StatesjM® ™ 5 1 8 58

■ ■ SCnrtis v. State, 188 Ark. 36, 64 S.W.2d 86 (1933) .......

Diaonv. State, 189 Ark. 812, 75 8 ^ .2 6 242 (1934)....... «

“ X l " u . S: 145 (1968, . . . I ................33

Edens v. State 2 3 5 68

........... 31

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) .... ........................

Fergason v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (19 1 ' 68

Fielder v. State, 206 Ark. 5 1 76 S.W.2d 233 (1943 .

Fi„ d s v. State, 203 Ark. 1046 * ^ » 78

Fradv v. United States, 348 4 .4d 84,

Freedman y. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965) ...................

Gadaden v. United States, 223 2

Gaines v. State, 208A A 293 S^W. ^ ‘Jg. 0| 69

Gerlach v. State, 217 JGfclOS,229 SI7i. .... g> ^ ^ ^

Giaccao v. Pennsylvania, 1Ana w 2 6 1 (1 9 11 )-- 35

Gilchrist v. State, 100 Ark. 330 140 A W . 261 911)..... ^

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U S . 407 1955 •-

Green r. State, 51 Ark. 189 \ 73

Green v. United States, 365 M . 30 ^

Green v. United States, 313 F.2 \ 7-̂

denied 372 U.S. 951 (1963) .........................................

V

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965) ....................... 1

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) ...............................

Hadley v. State, 205 Ark. 1027, 172 S.W.2d 237 (1943) 31

Haeue v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) .............. ------..........

Ham v. State, 179 Ark. 20,13 S.W.2d 805 (1929) ......... ^

Hamilton * A l a b « 1 U.(A 52 <19 1 — ~ 34

r ^ ^ ~ - 3 2 4 S.W.2d 520 (1959,....28, 31

Hi,l v. United States 368 VS.42 4 ^ ^ 31

r r ::v S t ; 2 18A; , * * * * « » < « « *

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U.S. 366 (18!l ) -■-"•••“ 35

" 188 a ! ’ 323, 67 S .W ,d 91 (1934, 31

____P„i o a___ _ 447 P.2d 117, 73 Cal.In re Anderson, Cal.2d

Bptr. 21 (1968) ......................................... ’ 50, si, 53, 56

49

In re Gault, 378 U.S. 1 .................... ............ 77

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961) ......................

Jackson v. '^ .W .O d ®

Jones v. State, 204 Ark. 61, 161 S.W.2d 173 (1942) ...

" ^ " S ^ c i r ^ : : ' 7 4

PAGE

VI

McDonald v. State, 225 Ark. 38, 279 S.W.2d 44 (1955) 34

McGraw v. State, 184 Ark. 342, 42 S.W.2d 373 (1931).... 68

McGuire v. State, 189 Ark. 503, 74 S.W.2d 235 (1934) 67

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964) ...............................10, 72

Marks v. State, 192 Ark. 881, 95 S.W.2d 634 (1936) .... 31

Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 (1959) ........... 74

Matter of Sims and Abrams, 389 F.2d 148 (5th Cir.

1967) ................................................................................... 4a

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) ......................... 6

Maxwell v. State, 236 Ark. 694, 370 S.W.2d 113 (1963) .....1,

4,7a

Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F. Supp. 205 (E.D.Ark. 1964)

aff’d 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), cert, denied, 382

U.S. 944 (1965) .............................................................. 2,4

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) ...........................27,71

Moore v. State, 227 Ark. 544, 299 S.W.2d 838 (1957) .... 69

Moorer v. South Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (4th Cir.

1966) ................................................................................... 4a

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1938) ................. 49

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ........ 9,35,47,59

Nail v. State, 231 Ark. 70, 328 S.W.2d 836 (1959) .....31, 35

Needham v. State, 215 Ark. 935, 224 S.W.2d 785 (1949) 30

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ................. 5

Osborne v. State, 237 Ark. 5, 371 S.W.2d 518 (1963) .... 69

Palmer v. State, 213 Ark. 956, 214 S.W.2d 372 (1948).... 31

People v. Hines, 61 Cal.2d 164, 390 P.2d 398, 37 Cal.

Rptr. 622 (1964) .......................................................41, 51, 72

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ........................... 34

Powell v. State, 149 Ark. 311, 232 S.W. 429 (1921) ..... 67

PAGE

Vll

PAGE

Rand v. State, 232 Ark. 909, 341 S.W.2d 9 (1960) ....... 69

Ray v. State, 194 Ark. 1155, 109 S.W.2d 954 (1937) ..... 28

Rayburn v. State, 200 Ark. 914, 141 S.W.2d 532 (1940) 67

Rhea v. State, 226 Ark. 664, 291 S.W.2d 521 (1956) .... 69

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963) ....................... 36

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) ......................... 53

Rorie v. Statq, 215 Ark. 282, 220 S.W.2d 421 (1949) .... 31

Rosemond v. State, 86 Ark. 160, 110 S.W. 229 (1908) .... 35

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963) ................... 6

Scarber v. State, 226 Ark. 503, 291 S.W.2d 241 (1956) ....28,

30

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87

(1965) .....|......................................................................... 58

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968) ......... 73,76

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 538 (1967) ............................... 76

Skaggs v. State, 234 Ark. 510, 353 S.W.2d 3 (1962) ..... 67

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ..... ..9,10, 27, 54,

61, 65,71, 75

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 (1931) ............................. 47

Smith v. State, 194 Ark. 1041, 110 S.W.2d 24 (1937) .... 31

Smith v. State, 205 Ark. 1075,172 S.W.2d 248 (1943).... 28

Smith v. State, 230 Ark. 634, 324 S.W.2d 341 (1959) ..... 28,

30, 31

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967) ....10, 27,49, 70, 75

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967) ........................ 75, 76

State v. Peyton, 93 Ark. 406, 125 S.W. 416 (1910) ....... 34

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 (1952) ......................... 34

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960) .... 45

Tigner v. Texas, 310 U.S. 141 (1940)............................... 61

Townsend v. Burke, 334 U.S. 736 (1948) ....................... 77

Turnage v. State, 182 Ark. 74, 30 S.W.2d 865 (1930) .... 31

Vlll

United States v. Behrens, 375 U.S. 162 (1963) .....25,71,72

United States v. Beno, 324 F.2d 582 (2d Cir. 1963) ..... 74

United States v. Curry, 358 F.2d 904 (2d Cir. 1965) .... 78

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968) .....10, 73, 77

United States v. Johnson, 315 F.2d 714 (2d Cir. 1963)

cert, denied, 375 U.S. 971 (1964) ...............................71,72

United States v. National Dairy Prods. Corp., 372 U.S.

29 (1963) ........................................................................... 60

United States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F.2d 311

(3rd Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 844 (1963) .... 74

United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Banmiller, 310 F.2d 720

(3rd Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 828 (1963) .... 74

Walton v. State, 232 Ark. 86, 334 S.W.2d 657 (1960) .... 28

Ward v. State, 236 Ark. 878, 370 S.W.2d 425 (1963) .... 69

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ....... 25

Weakley v. State, 168 Ark. 1087, 273 S.W. 374 (1925).... 69

Webb v. State, 154 Ark. 67, 242 S.W. 380 (1922) .......28, 30

Wells v. State, 193 Ark. 1092,104 S.W.2d 451 (1937) .... 28

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) ....... 10, 76

Wilkerson v. State, 209 Ark. 138,189 S.W.2d 800 (1945) 31

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) ....................... 34

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) ................... 70

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 (1959) ................... 70

Willis v. State, 220 Ark. 965, 251 S.W.2d 816 (1952)....67, 68

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948) ..................... 47

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) —.11, 27, 33, 34,

47,48,49,

61, 70, 78

Wright v. State, 243 Ark. 221, 419 S.W.2d 320 (1967)....67,

68

PAGE

IX

Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ........... 5, 9, 47, 56,

57, 62

Young v. State, 230 Ark. 737, 324 S.W.2d 524 (1959) .... 31

S ta t u t e s :

Federal:

10 U.S.C. $920 (1964) ......................................................... 21

18 U.S.C. $2031 (1964) ........................... ......................... 21

28 U.S.C. $1254(1) (1964) ................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. $1291 (1964) ......... i.......................................... 2

28 U.S.C. $2241(c)(3)(1964) ............................................. 2

28 U.S.C. $2244(b) (Supp. II, 1966) ............................... 6

28 U.S.C. $2253 (1964) ....................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. $2254 (Supp. II, 1966) ..................................... ' 6

State:

Ala. Code $$14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (Recomp. Vol. 1958) 21

Ark. Acts 1915, No. 187, $ 1 ............................................... 2®

Ark. Stat. Ann. $28-707 (1962 Repl. Vol.) ................ 68

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-2205 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ................ 35

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-3401 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ............... 34

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-2205 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ..................... 35

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-3403 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ....3,21,24,27

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-3405 (1964 Repl. Vol.) . 21

Ark. Stat. Ann. $41-3411 (1964 Repl. Vol.) . 21

Ark. Stat. Ann. $43-2108 (1964 Repl. Vol.) . 28

Ark. Stat. Ann. $43-2153 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ......3,21,27

Ark. Stat. Ann. $43-2155 (1964 Repl. Vol.) . 24

Ark. Stat. Ann. $43-2155 (1964 Repl. Vol.) ................... 24

Cal. Penal Code $190.1 (Supp. 1966) ............................... 78

Conn. Gen. Stat. Rev. $53-10 (Supp. 1965) ............... ...... 78

PAGE

X

D.C. Code Ann. $22-2801 (1961) ....................................... 21

Fla. Stat. Ann. $794.01 (1964 Cum. Supp.) ................... 21

Ga. Code Ann. $$26-1302, 26-1304 (1963 Cum. Supp.) .... 21

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. $435,090 (1963) ............................... 21

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. $14:42 (1950) ................................... 21

Md. Ann. Code $$27-463, 27-12 (1967 Cum. Supp.) ....... 21

Miss. Code Ann. $2358 (Recomp. Vol. 1956) ................... 21

N.C. Gen. Stat. $14-21 (Recomp. Vol. 1953) ................... 21

N.Y. Pen. Law $$125.30,125.35 (Cum. Supp. 1968) ....... 78

Nev. Rev. Stat. $$200,363, 200.400 (1967) ..................... 21

Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21, $$1111, 1114, 1115 (1958) ....... 21

Pa. Stat. Ann., tit. 18, $4701 (1963) ................................. 78

S.C. Code Ann. $$16-72, 16-80 (1962) ............................. 21

Tenn. Code Ann. $$39-3702, 39-3703, 39-3704, 39-3706

(1955) ................................................................................. 21

Tex. Code Crim. Pro., Art. 37.07 (1967) ....................... 78

Tex. Pen. Code Ann., Arts. 1183, 1189 (1961) ..... ......... 21

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. $559,260 (1953) ....................... 21

Va. Code Ann. $$18.1-44, 18.1-16 (Repl. Vol. 1960) ..... 21

PAGE

xi

Other Authorities:

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tent.

Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959), Comment to $201.6....... 10,70

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, $210.6

(P.O.D. May 4, 1962) .........................................62, 64, 74, 78

Bedau, A Social Philosopher Looks at the Death Pen

alty, 123 Am. J. Psychiatry 1361 (1967) ................... 16

Bedau, Death Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19

Rutgers L. Rev. 1 (1964) ...........................................13,30a

Bedau, The Death Penalty in America (1964) .......15,16, 26

Cardozo, Law and Literature (1931) ............................... 35

DiSalle, Comments on Capital Punishment and Clem

ency, 25 Ohio St. L.J. 71 (1964) ..................................... 13

Duffy & Hirshberg, 88 Men and 2 Women (1962) ......... 12

Florida Division of Corrections, Fifth Biennial Report

(July 1, 1964-June 30, 1966) (1966) ....................... 28a, 32a

Garfinkel, Research Note on Inter- and Intra-Racial

Homicides, 26 Social Forces 369 (1949) ................... 16

Handler, Background Evidence in Murder Cases, 51 J.

Crim. L., Crim . & P ol. Sci., 317, 321-327 (1960) ......... 71

H.L.A. Hart, Murder and the Principles of Punish

ment: England and the United States, 52 Nw. U.L.

Rev. 433, 438-439 (1957) ...................................... .........70-71

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, 284

Annals 8 (1952) ...............................................................16, 26

House of Commons Select Committee on Capital Pun

ishment, Report (H.M.S.O. 1930), para. 177

PAGE

70

XU

Institute of Judicial Administration, Disparity in Sen

tencing of Convicted Defendants (1954) ................... 36

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36

Social Forces 165 (1957) ............................... 13,16, 27a, 30a

Johnson, The Negro and Crime, 271 Annals 93 (1941) .. 16

Kalven & Zeisel, The American Jury (1966) ...............26, 34,

37, 41, 44, 30a

Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital

Cases, 101 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1099 (1953) .......................26, 71

Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing (1932) .... 12

Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations, 1963

Supreme Court Review 101, 110 ................................... 47

Mattick, The Unexamined Death (1966)........................... 16

New York State Temporary Commission on Revision

of the Penal Law and Criminal Code, Interim Report

(Leg. Doc. 1963, No. 8) ................................................... 70

Packer, The Limits of the Criminal Sanction (1968)

92-94 ....................................................................... ;............ 57

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964) ............................................... 65

Partington, The Incidence of the Death Penalty For

Rape in Virginia, 22 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 43 .......26a, 27a

Pennsylvania, Joint Legislative Committee on Capital

Punishment, Report (1961) ........................................... 16

Perkins, Criminal Law (1957) ........................................... 34

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice, Report (The Challenge of

Crime in a Free Society) (1967) ...............................16, 36

PAGE

70

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, 1949-1953,

Report (H.M.S.O. 1953) (Cmd. No. 8932), 6, 12-13,

195, 201-207 .........................................................................

Rubin, Disparity and Equality of Sentences—A Con

stitutional Challenge, 40 F.R.D. (1966) ............... 16, 36, 54

State of California, Department of Justice, Division of

Law Enforcement, Bureau of Criminal Statistics,

Report (Crime and Delinquency in California, 1967)

(1968) ................................................................................ 32a

State of Georgia Board of Corrections, Annual Report

(1965), (1966), (1967) .............................................28a, 32a

State of Maryland, Department of Correction, For

tieth Report (1966) ...................................................28a, 32a

Statement by Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Before

the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures

of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on S. 1760, To

Abolish the Death Penalty, July 2, 1968, Department

of Justice Release, p. 2 ................................................... 12

Symposium on Capital Punishment, 7 N.Y.L.F. (1961) 23

Tennessee Department of Correction, Departmental

Report (1966) .............................................................29a, 32a

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/SD/9-10)

(1968) .............................................T................................16,22

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Pris

ons, National Prisoner Statistics................................... 14

No. 42, Executions 1930-1967 (June, 1968) ....14,15, 24a,

28a, 32a, 33a, 34a

No. 41, Executions 1930-1966 (April, 1967)....... 24a, 27a,

28a, 29a, 31a, 32a, 33a

XIV

No 39, Executions 1930-1965 (June, 1966)....... 24a, 27a,

28a, 31a, 32a, 33a

No. 37, Executions 1930-1964 (April, 1964 [sic:

1965]) ........................... —...... 24a, 27a, 28a, 31a, 32a

No. 34, Executions 1930-1963 (May, 1964) 24a, 27a, 31a

PAGE

No 32, Executions 1962 (April, 1963) ...................13,14,

24a, 27a, 31a

No. 28, Executions 1961 (April, 1962) ....... 24a, 27a, 31a

United States Senate, Sub-Committee on Criminal

Laws and Procedures of the Committee on the Judi

ciary, Hearings on S. 1760, to Abolish the Death

Penalty (Unprinted Report of Proceedings, March

20, 1968) ...........................................................................12’ 13

West, Dr. Louis J., “ A Psychiatrist Looks at the Death

Penalty,” Paper Presented at the 122nd Annual

Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association,

Atlantic City, New Jersey, May 11, 1966, p. 2 ........ . 11

W olf Abstract of Analysis of Jury Sentencing in Capi

tal Cases : New Jersey: 1937-1961,19 Rutgers L. Rev.

56 (1964) ........................................................................... 31a

62 Harv. L. Rev. 77-78 Due Process Requirements of

Definiteness in Statutes (1948) ................................... 49> 50

109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67, 90 (1960) .............................. 47,59,61

109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 69, 81 (I960) ....................................... 52

69 Yale L.J. 1453, 1459 (1960) ........................................... 55

In t h e

CEourt of tli£ T&mUb States

October T erm, 1968

No. 622

W illiam L. Maxwell,

Petitioner,

—v.—

O.E. B is h o p , Superintendent of

Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas denying petitioner’s applica

tion for a writ of habeas corpus is reported at 257 F. Supp.

710. It appears in the Appendix [hereafter cited A ......] at

20-41. The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit affirming the district court is re

ported at 398 F.2d 138, and appears at A. 43-74.

Opinions at earlier stages of this proceeding are re

ported. The opinion of the Supreme Court of Arkansas

affirming petitioner’s conviction for the crime of rape an

sentence of death is found sub nom. Maxwell v. State, 26b

Ark 694 370 S.W.2d 113 (1963). Opinions on disposition

of an earlier application for federal habeas corpus are

2

found sub nom. Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F. Supp. 205

(E.D. Ark. 1964), aff’d, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), cert,

denied, 382 U.S. 944 (1965).

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of the district court was conferred by

28 U.S.C. §2241(c)(3) (1964). Jurisdiction of the court of

appeals was conferred by 28 U.S.C. §§1291, 2253 (1964).

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. §1254

(1) (1964).

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on

July 11, 1968. (A. 75.) The petition for a writ of certio

rari was filed in this Court on October 9, 1968, and was

granted on December 16, 1968 (A. 76), limited to Ques

tions 2 and 3 of the petition.

Questions Presented

I. Whether Arkansas’ practice of allowing capital trial

juries absolute discretion, uncontrolled by standards or

directions of any kind, to impose the death penalty upon

a defendant convicted of the crime of rape violates the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

II. Whether Arkansas’ single-verdict procedure, which

requires the jury to determine guilt and punishment simul

taneously in a capital case, and thus requires a capital

defendant to elect between the exercise of his privilege

against self-incrimination and the presentation of evidence

requisite to rational sentencing choice, violates the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The case involves the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States.

It also involves A rkansas Statutes A nnotated, §§41-

3403, 43-2153 (1964 Repl. vol.), which provide, respectively,

as follows:

41-3403. Penalty for Rape. — Any person convicted

of the crime of rape shall suffer the punishment of

death [or life imprisonment],

43-2153. Capital cases — Verdict of life imprison

ment. — The jury shall have the right in all cases

where the punishment is now death by law, to render

a verdict of life imprisonment in the State penitentiary

at hard labor.

Statement

Petitioner, William L. Maxwell, a Negro, was tried in

the Circuit Court of Garland County, Arkansas, in 1962

for the rape of a 35 year old, unmarried white woman. (A.

20.) As we shall describe more fully below, his trial was

conducted pursuant to the ordinary Arkansas procedures

for trying a capital case upon a plea of not guilty. The

issues of guilt and punishment were simultaneously tried

and submitted to the jury, which was given no instruc

tions limiting or directing its absolute discretion, in the

event of conviction, to elect between the punishments of

life or death.1 (A. 28-30, 40-41; see pp. 27-32, 66 n. 69, 35a

infra.)

1 Technically, an Arkansas jury chooses life by returning the

“verdict of life imprisonment” authorized by Ark. Stat. A nn.

§43-2153 (1964 Repl. vol.), text, supra. It chooses death by re

turning a guilty verdict without mention of life imprisonment,

upon which the death sentence is imposed as a matter of course

under Ark. Stat. A nn. §41-3403 (1964 Repl. vol.), text, supra.

(See A. 29, 44.)

4

Maxwell’s jury elected the punishment of death. The

Supreme Court of Arkansas affirmed. Maxwell v. State,

236 Ark. 694, 370 S.W.2d 113 (1963).2 A 1964 federal

habeas corpus proceeding challenging his rape conviction

and death sentence brought no relief. Maxwell v. Stephens,

229 F. Supp. 205 (E.D. Ark. 1964), aff’d, 348 F.2d 325

(8th Cir. 1965) (one judge dissenting), cert, denied, 382

U.S. 944 (1965).

The present habeas corpus proceeding was commenced

by a second federal petition, filed July 21, 1966. (A. 2-12.)

This petition raised, inter alia, three related constitutional

attacks upon petitioner’s death sentence. First, it com

plained of “ the unfettered discretion of the jury to choose

between the sentence of life or death. The jury’s choice

was . . . unregulated by legal principles of general appli

cation, was left to be determined by arbitrary and dis

criminatory considerations, and was in fact arbitrary and

discriminatory in petitioner’s case.” (A. 8.) Second, the

petition challenged Arkansas’ capital trial practice under

which “ the issues of guilt or innocence and of life or death

sentence [are] . . . determined by a jury simultaneously,

after the jury has heard evidence on both issues in the

same proceeding.” (A. 9.) This single-verdict procedure

(as we shall hereafter call it) not merely empowers, but

virtually compels, arbitrary capital sentencing because it

deprives the sentencing jury of information that is requi

site to rational sentencing choice, since “ evidence perti

nent to the question of penalty could not be presented

without prejudicing the jury against the petitioner on the

issue of guilt. . . . Nor could petitioner exercise his con

stitutional right of allocution before the jury which sen

tenced him, without thereby waiving his privilege against

self-incrimination held applicable to the states under the

2 No review of this decision was sought in this Court.

5

Fourteenth Amendment. . . . ” (A. 9-10.) Finally, petitioner

alleged that the arbitrary capital sentencing practices

which he attacked had in fact resulted in arbitrary appli

cation of the death penalty by Arkansas juries for the

crime of rape: Negroes convicted of the rape of white

women were discriminatorily sentenced to die on account

of race. (A. 5-7.)

The federal district court allowed a thorough evidentiary

hearing on the racial discrimination claim. (A. 17-18.)

That claim has been excluded from the present phase of

the case by this Court’s limited grant of certiorari (A. 76);

and we need not extend this Statement by describing the

evidence presented at the hearing. However, we shall have

occasion to refer to it in the argument portions of this1

brief, under the principle that where a state practice is

challenged as conferring arbitrary and lawless power tend

ing to abuse, in a manner forbidden by the Fourteenth

Amendment, proof that the power has in fact been regularly

abused is entitled to considerable weight.2 For this reason,

we set forth in Appendix A to the brief, pp. la-23a infra,

a detailed description of petitioner’s evidence in the dis

trict court relating to a thorough and extensive empirical

study of capital sentencing by Arkansas juries in rape

cases during the period 1945-1965, together with the find

ings of the district court and of the court of appeals in

reference to this study. [Appendices to the brief will here

after be cited as App., p......a, infra.]

After hearing, the district court rendered its opinion of

August 26, 1966 (A. 20-41), rejecting petitioner’s conten

tion of discrimination (A. 33-40) and upholding the A r

kansas procedures of unfettered jury discretion in capital

3 Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 5 ); Niemotko v.

Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1 951); Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496

(1 939); Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

6

sentencing (A. 28-33) and the single-verdict capital trial

(A. 40-41). The court declined to stay petitioner’s execu

tion, set for September 2, 1966 (A. 41) and declined to

issue a certificate of probable cause for appeal. Circuit

Judge Matthes of the Eighth. Circuit similarly refused a

stay or a certificate; but petitioner’s execution was stayed

by Mr. Justice White on September 1, 1966; and this

Court subsequently reversed Judge Matthes’ orders and

remanded to the Court of Appeals for hearing of the

appeal. Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967).

By its opinion of July 11, 1968 (A. 43-74), the court of

appeals rejected on the merits each of petitioner’s consti

tutional claims (A. 47-64 (racial discrimination), 64-68

(unfettered jury discretion), 68-69 (single-verdict proce

dure)). It accordingly affirmed the judgment of the dis

trict court denying petitioner’s application for habeas

corpus relief. (A. 75.)*

Summary of Argument

All informed observers of the institution of capital

punishment in this country have noted its salient char

acteristic: it is unevenly, arbitrarily and discriminatorily

applied. That observation is strikingly borne out on this

record, which demonstrates that Arkansas juries have per

4 Adjudication on the merits was appropriate. State remedies

were exhausted, within 28 U.S.C. §2254 (Supp. II, 1966), since

no procedures are available in the Arkansas courts by which Peti-

tioner can raise his federal constitutional claims. This was alleged

in petitioner’s habeas application (A. 11), and admitted by respon

dent’s response (A. 14). The district court exercised its discretion

under Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963), and 28 U.S.C.

§2244(b) (Supp. II, 1966), to entertain on the merits each of

petitioner’s present constitutional contentions, although presented

in a second federal habeas corpus petition; and the propriety of its

doing so cannot be questioned. See Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S.

650 (1967).

7

sistently discriminated on grounds of race in sentencing

men to die. The court of appeals below admitted there

are “ recognizable indicators” that “ the death penalty for

rape may have been discriminatorily applied over the

decades in that large area of states whose statutes pro

vide for it.” (A. 63.) But whether or not racial discrim

ination was here proved or is provable statistically, it

can hardly be denied that the evidence relating to actual

exercise of jury discretion in capital cases “ casts con

siderable doubt upon the quality of justice in those partic

ular cases throughout the system.” 4 * 6 * Extreme arbitrariness

in the selection of the few men sentenced to death and

executed, out of the great number convicted of capital

offenses each year, is patent; and (as we have pointed

out in greater detail in our amicus curiae brief in a com

panion case)6 the very extremity of this arbitrariness may

effectively conceal the workings of racial discrimination

and of every other invidious prejudice forbidden by the

Constitution. At the very least, the record compels this

Court’s strictest scrutiny under the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the regularity and fairness o f the procedures by

which state courts, through their juries, choose the men

who will die.

I.

Petitioner challenges here the practice of uncontrolled

and undirected jury discretion in capital sentencing that

lies at the root of arbitrary and discriminatory imposition

of the death penalty. This is a practice which, even its

defenders must admit, is arbitrary in a legal sense. It

confers upon a group of twelve jurors, selected ad hoc to

6 The phrase is that of petitioner’s expert witness, an eminent

criminologist, testifying in the district court below. See note 19

infra.

* Boykin v. Alabama, O.T. 1968, No. 642. See note 17 infra.

8

decide a particular case, a power to determine the question

of life or death that is unlike any other power possessed

by a jury, or even by a court, in our legal system. The

life-or-death decision is made utterly without standards

or governing legal principles; it is made without the

limitation of requisite factual findings, or of required

attention to any range or realm of fact, or of required

consideration of any general rule or policy of law; it is

made without any judicial control over the process or

the consequence of the jurors’ determination. The con

scientious and fairminded juror is given not the slightest

idea what he is to do, while the covert discriminator is

given absolute license to practice his biases in the matter

of taking human life. This unfettered jury discretion-

or, rather, naked and arbitrary power, lacking every at

tribute of legal discretion—can be likened only to the

unimaginable procedure of submitting to a jury in a civi

case the unadorned question whether the defendant ought

to be liable to the plaintiff; or, in a criminal case, whether

the defendant has done something for which he should be

punished. Such submissions are not made anywhere m

American law -except in the enormous decision whether

men shall live or die. They violate the rule of law that

is basic to Due Process, and especially critical m regard

to the choice of life or death.

Unfettered jury discretion in capital sentencing exhibits

those vices that have repeatedly been condemned by this

Court under the constitutional principles forbidding in

definiteness in penal legislation. First, a capital defendant

with his life at stake, does not fairly know how to conduct

his defense. He does not know—to take one example

whether the jurors will regard mental disorder as a

mitigating circumstance or an aggravating one; or whether

five jurors will think the circumstance mitigating while

seven vote to kill him for it. As a result, the capital trial

is a grisly game of blind-man’s buff, played for the

defendant’s life. Second, and more important, the con

ferring on the jury of “ a naked and arbitrary power”

(Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 366 (1886)) to take a

man’s life for any reason or for no reason offends the

principle of legality, of regularity—the principle requiring

a rule of law and not of men—which the Due Process

Clause asserts as a protection against laws that would

otherwise he “ susceptible of sweeping and improper ap

plication” (N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 433 (1963),

“ lest unwittingly or otherwise invidious discriminations

are made against groups or types of individuals in viola

tion of the constitutional guarantee of just and equal

laws” (Skitmer v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942)).

Due Process of Law fundamentally repudiates any such

power, which “ leaves . . . jurors free to decide, without

any legally fixed standards” (Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382

U.S. 399 (1966)), whether human life shall or shall not

be forfeit, even as a punishment for crime.

U.

The vices of unfettered jury discretion are compounded

when the jury’s life-or-death decision is made under a

single-verdict procedure. Whereas unfettered discretion

allows the jury arbitrary power, the single-verdict trial

virtually requires that that power be exercised arbitrarily.

This is so because information that is absolutely requisite

to rational sentencing choice cannot be presented to the

jury except at the cost o f an unfair trial on the issue of

guilt or innocence, and of enforced waiver of the defen

dant’s privilege against self-incrimination.

The single-verdict capital trial is federally unconstitu

tional for two reasons. First, it unnecessarily compels

a choice between the defendant’s Fifth and Fourteenth

10

Amendment privilege against self-incrimination (Malloy

v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964)) and his Fourteenth Amend

ment right “ to be heard . . . and to offer evidence of his1

own” (Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605, 610 (1967))

on the vital question of capital sentencing. As a result,

it unconstitutionally burdens the Privilege (United States

v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968); Simmons v. United States,

390 U.S. 377 (1968)) by attaching to its exercise the in

dependently unconstitutional consequence that the capital

sentencing decision is made irrationally (Skirmer v. Okla

homa, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)), because made “upon less than

all of the relevant evidence” (Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S.

368, 389 n. 16 (1964)). Second, this procedure that forces

the capital defendant to a “choice between a method which

threatens the fairness of the trial of guilt or innocence

and one which detracts from the rationality of the deter

mination of sentence” 7 presents a “ grisly, hard, Hobson’s

choice” 8 * which is fundamentally unfair, in the Due Process

sense, where the wages of the gamble are death.

• • •

Logical presentation requires that our arguments relat

ing to unfettered jury discretion and to the single-verdict

procedure be stated separately. Either argument alone is,

in our view, sufficient to vitiate William L. Maxwell’s sen

tence of death under the Fourteenth Amendment. How

ever, it must be remembered that both of the challenged

procedures were employed at Maxwell’s trial. Their vices,

as we have pointed out, are mutually compounding. Used

together, they deprive Maxwell of his life after a trial ut

terly lacking in the rudimentary fairness and regularity

7 A merican Law Institute, Model P enal Code, Tent. Draft

No. 9 (May 8, 1959), Comment to §201.6, at 64.

‘ Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1964). Cf.

Pay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 440 (1963).

11

that Due Process assuredly demands when a state em

powers its jurors “ to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question

whether this defendant was fit to live” ( Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 521 n. 20 (1968)).

ARGUMENT

Introduction: The Fact and Implications of

Arbitrary Capital Sentencing

Knowledgeable observers of the administration of capital

punishment in the United States agree that death is meted

out among persons convicted of capital crimes in a fashion

that is uneven, rationally unsupportable and arbitrary in

the extreme.

“ Of all the uncertain manifestations of justice, capi

tal punishment is the most inequitable. It is primarily

carried out against the destitute, forlorn and forgotten.

. . . Members of racial and cultural minority groups

suffer most. The hundreds of extraneous factors, in

cluding geography, that decide whether a convicted

man will actually live or die, makes capital punishment

a ghastly, brainless lottery.” (Dr. Louis J. West, “ A

Psychiatrist Looks at the Death Penalty,” Paper Pre

sented at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American

Psychiatric Association, Atlantic City, New Jersey,

May 11,1966, p. 2.)

Arbitrariness in the selection of men to be put to death

takes several forms. First, there is simply the matter of

baseless discrimination among individuals: freakish, whim

sical, erratic difference in the treatment of similar men

guilty o f similar offenses. As the Attorney General o f the

United States put it recently:

12

“A small and capricious selection of offenders have

been put to death. Most persons convicted of the same

crimes have been imprisoned. Experienced wardens

know many prisoners serving life or less whose crimes

were equally, or more atrocious, than those of men on

death row.” (Statement by Attorney General Ramsey

Clark, Before the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and

Procedures of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on

S. 1760, To Abolish the Death Penalty, July 2, 1968,

Department of Justice Release, p. 2.)

Those who should surely know—the respected long-time

wardens of Sing-Sing and San Quentin prisons—corrobo

rate the Attorney General. L awes, T wenty T housand

Y ears in S ing S ing (1932) 302, 307-310; D uffy & H irsh-

beeg, 88 Men and 2 W omen (1962) 254-255.®

Second, there is economic and caste discrimination.

“ [T]he death penalty . . . almost always hits the

little man, who is not only poor in material possessions

but in background, education, and mental capacity as

well. Father Daniel McAlister, former Catholic chap

lain at San Quentin, points out that ‘the death penalty

seems to be meant for the poor, uneducated, and legally

impotent offender.’ ” (D uffy & H ieshberg, op. cit.

supra, 256-257.)

8 See also the testimony of Clinton T. Duffy, in United States

Senate, Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures of the

Committee on the Judiciary, Hearings on S. 1760, To Abolish the

Death Penalty (unprinted report of proceedings, March 20, 1968),

vol. 1, pp. 44 -44A : “ I have often said, and I repeat here, that I

can take you into San Quentin Prison or to Sing Sing, Leaven

worth or Atlanta Prisons and I can pick out many prisoners in

each institution serving life sentences or less, and can prove that

their crimes were just as atrocious, and sometimes more so, than

most of those men on the row.”

13

Former Ohio Governor Michael DiSalle has made the same

point: “ I want to emphasize that from my own personal

experience those who were sentenced to death and appeared

before me for clemency were mostly people who were with

out funds for a full and adequate defense, friendless, un

educated, and with mentalities that bordered on being de

fective.” (DiSalle, Comments on Capital Punishment and

Clemency, 25 Ohio State L. J. 71, 72 (1964).)10

Third, there is persuasive evidence of that most corrosive

and invidious form of discrimination, racial prejudice, in

the selection of the men who will die. The Federal Bureau

of Prisons maintains reliable statistics on executions in the

United States since 1930. Between that year and 1962, the

year in which petitioner Maxwell was sentenced to die, 446

persons were executed for rape in this country.11 Of these,

10 See also the testimony of Michael DiSalle, in Hearings, note 9

supra, vol. 1, pp. 14-16. The Governor’s observations are supported

by those of scholars who have undertaken to describe the charac

teristics of men on death row in other states. E.g., Bedau, Death

Sentences in New Jersey 1907-1960, 19 R utgers L. Rev. 1 (1964) ;

Johnson, Selective Factors in Capital Punishment, 36 Social

F orces 165 (1957). And see the study of Florida’s death row

population described in the Brief for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., and the National Office for the Rights

of the Indigent, as Amici Curiae, in Boykin v. Alabama, O.T. 1968,

No. 642, at p. 7 n. 8.

11 The figures below are taken from United States D epartment

of Justice, B ureau of Prisons, National P risoner Statistics,

No. 32, Executions 1962 (April, 1963), which was put in evidence

as petitioner’s Exhibit P-6 at the habeas corpus hearing below.

Table 1 thereof shows the following numbers and percentages of

executions under civil authority in the United States between 1930

and 1962:

Negro

Rape 399 (89.57c)

Murder 1619 (49.1% )

Other 31 (45.6% )

Total 2049 (53.77c)

White Other Total

45 (10.17c)

1640 (49.77c)

37 (54.4% )

1722 (45.2% )

2 (0.47c) 446 (1007c)

39 (1.2%.) 3298 (1007c)

_0 (0.07o) 68 (1007c)

41 (1.170 3812 (1007c)

(Continued on p. 14)

14

399 were Negroes, 45 were whites, and 2 were Indians. All

were executed in Southern or border States or in the Dis

trict of Columbia. The States of Louisiana, Mississippi,

Oklahoma, Virginia, West Virginia and the District never

executed a white man for rape during these years. Together

they executed 66 Negroes. Arkansas, Delaware, Florida,

(Continued from p. 13)

Table 2 thereof shows the following numbers of executions under

civil authority in the United States between 1930 and 1962, for the

offense of rape, by race and state:

Jurisdiction Negro White Other Total

Federal ............................... 0 2 0 2

Alabama ............................. .... 20 2 0 22

Arkansas .......................... .... 17 1 0 18

Delaware ............................. 3 1 0 4

District of Columbia .... 2 0 0 2

Florida ............................... .... 35 1 0 36

Georgia ............................... .... 58 3 0 61

Kentucky ........................... 9 1 0 10

Louisiana .......................... .... 17 0 0 17

Maryland .......................... .... 18 6 0 24

Mississippi ........................ .... 21 0 0 21

Missouri ............................. 7 1 0 8

North Carolina ............... .... 41 4 2 47

Oklahoma .......................... 4 0 0 4

South Carolina ............... .... 37 5 0 42

Tennessee ........................... .... 22 5 0 27

Texas .................................... .... 66 13 0 79

Virginia ............................. .... 21 0 0 21

West Virginia ................. 1 0 0 1

Total ................................... .... 399 45 2 446

The figures have not changed appreciably since 1963. According

to the latest National Prisoner Statistics Bulletin, United States

Department of J ustice, B ureau of Prisons, National Prisoner

Statistics, N o. 42, Executions 1930-1967 (June, 1968), p. 7, table

1, the following are the numbers and percentages of executions

under civil authority in the United States between 1930 and 1967:

Negro White Other Total

Rape 405 (89 .0% ) 4 8 (1 0 .6 % ) 2 ( 0 .4 % ) 455 (100% )

Murder 1630 (48 .9% ) 1664 (49.9% ) 4 0 (1 .2 % ) 3334 (100% )

Other 3 1 (4 4 .3 % ) 39 (55.7% ) 0 (0 .0 % ) 70 (100% )

Total 2066 (53 .1% ) 1751 (45.4% ) 4 2 (1 .1 % ) 3859 (100% )

(Continued on p. 15)

15

Kentucky and Missouri each executed one white man for

rape between 1930 and 1962. Together they executed 71

Negroes. Putting aside Texas (which executed 13 whites

and 66 Negroes), sixteen Southern and border States and

the District of Columbia between 1930 and 1962 executed

30 whites and 333 Negroes for rape: a ratio of better than

one to eleven. The nationwide ratio of executions for the

crime of murder was considerably less startling—one Negro

for each one white—but still startling enough, since Negroes

constituted about one-tenth of the Nation’s population dur

ing these years.

Of course, these suspicious figures might be explained, not

by arbitrary and discriminatory administration of the death

penalty, but by some rather extravagant hypotheses about

the Negro crime rate.12 Responsible analysts have rejected

Buch an explanation. With virtual unanimity, commissions

and individuals studying capital punishment have found

(Continued from p. 14)

The following is the breakdown of the 435 men reported under

sentence of death in the country as of December 31, 1967 {id., pp.

22-23, table 1 0 ):

Negro

Nine Northeastern States ........... 33

Twelve North-Central States .... 24

Thirteen Western States ............. 21

Sixteen Southern States ............. 159

Federal ............... :.............................. 1

Total ................................................... 238

White Other Total

29 0 62

31 0 55

68 2 91

66 0 225

1 0 2

195 2 435

12 In fact, the number of crimes committed by Negroes appears

to be three to six times higher than that which the ratio of Negroes

in the population would lead one to expect. See Bedau, T he D eath

Penalty in A merica (1964) 412. Negroes constitute one-tenth or

one-ninth of the population (depending upon the time periods

under consideration). So, instead of the expectable one Negro-

committed crime to every nine white-committed crimes, there are

three to six Negro crimes to every nine white crimes. Far more

crimes numerically are obviously committed by whites than by

Negroes. Yet one Negro murder convict is executed for every

white murder convict executed; and nine Negro rape convicts are

executed for every white rape convict executed. See text, supra.

16

evidence that the imposition of the death sentence and the

exemse of dispensing power by the courts and the execu

tive follow discriminatory patterns. The death sentence is

disproportionately imposed and carried out on the poor,

e egro, and the members of unpopular groups.” P resi-

dent s Commission on L aw E nforcement and A dminister,

tion oe justice, R epoet (T he Challenoe op Ceime in a

F ree Society) (1967) 143. See also United Nations, De-

aetment of E conomic and Social A ffairs, Capital P un

J oint 1̂ (ST/SO A^ SD/ 9-10) <1968) 32, 98; Pennsylvania,

J oint L egislative Committee on Capital P unishment B e-

mee Ur ° K’

(1964 THE DEATH Penaltt ™ A merica

n /t p t 5 Bedau’ A S°cial Phil0^pher Looks at the

ea Penalty, 123 A m . J. P sychiatry 1361, 1362 (1967) •

t in t* !'n .T ntyr t EqUaUty °f 8entences-A Constitu-

tional Challenge, 40 F.B.D. 55, 66-68 (1966); Johnson, Selec

1957^H0rV n ° T tal Punishment> 36 Social F orces 165

2S4 A J HartU0Df Prends in th° Use of Capital Punishment,

284 A nnals 8, 14-17 (1952); Garfinkel, Research Note on

(19491 ° WT k ra'R™ al Hom™ides, 26 Social F orces 369

(1941) : J0hI1S0n, The Negr° and Crime> 271 A nnals 93

In order to provide a more systematic and rigorous ex

amination of the evidence of racial differentials in capital

sentencing, an extensive empirical study of sentencing pat-

terns in rape cases was undertaken in 1965 by Dr. Marvin

E. Wolfgang, an eminent criminologist, at the request of

counsel for petitioner Maxwell (who also represenTnumer-

ous condemned men in other States). Dr. Wolfgang’s study

covered every case of conviction for rape in 250 counties in

e even States during the twenty-year period 1945-1965. The

data gathered in Arkansas, and Dr. Wolfgang’s analysis of

that data, were the subject of his testimony at the habeas

corpus hearing below. The testimony and the findings of

17

the lower courts relating to it are described in detail in

Appendix A, pp. la-23a infra. We summarize them briefly

here because of the importance of Dr. Wolfgang’s conclu

sions, which confirm the earlier impressions of racial dis

crimination on the basis of the first fully controlled, exact

ing scientific study of the subject.

Dr. Wolfgang’s study began with the collection of data

concerning every case of conviction for the crime of rape

on the docket books of nineteen randomly selected Arkansas

counties, containing 47% of the State’s total population,

for the twenty years 1945-1965. The nineteen counties were

selected by accepted areal sampling methods with the goal

of producing a sample that would be representative of the

State of Arkansas as a whole; and, in the opinion of the

expert statistician whom Dr. Wolfgang employed to per

form the sampling operation, “ inferences drawn from this

sample . . . are valid for the State of Arkansas.” One point

should be stressed. The study, from the outset, concerns

cases of conviction for the capital crime of rape, and what

is studied is the performance of Arkansas juries in select

ing the convicted defendants upon whom they impose the

death penalty. It thus controls completely the possibility,

suggested above, that high frequencies observed in the

sentencing of Negroes to die for the crime of rape might he

explained by the supposition that Negroes commit rape, or

are convicted of rape, more frequently than whites. This

study compares the rate of death sentencing for Negro and

white defendants all of whom have been convicted of rape.

Field researchers dispatched to Arkansas conducted an

exhaustive investigation of each case where a rape convic

tion had been had in the sample counties. They followed a

predetermined pattern for exploring the available sources

of information about each case, beginning with court rec

ords, trial transcripts, witness blotters, file jackets, judicial

opinions, etc., then proceeding to prison and pardon board

18

records, and finally to newspaper files and interviews with

trial counsel. They had uniform procedures for assigning

priorities to information sources in the event of conflicts;

and they used a uniform schedule, with objectively defined

categories, for recording the data found. At the hearing

below, the State of Arkansas conceded the validity of all of

the data thus gathered and recorded.

The “critical” data for each case were race of defendant,

race of victim, and sentence. Dr. Wolfgang analyzed these

variables and found conclusively that Negro defendants

convicted of the rape of white women were disproportion

ately frequently sentenced to death. Applying tests of

statistical significance that are generally used in the social

sciences (and in other disciplines, such as medical research,

as well), he found that the disproportionate frequency with

which the death sentence was imposed on these Negro de

fendants was so great that there was a less than two per

cent probability of its having occurred by chance. Put

another way, if race were not really related to the capital

sentencing patterns of Arkansas juries, the results observed

in the twenty years between 1945 and 1965 could have oc

curred fortuitously in fewer than two twenty-year periods

since the birth o f Christ. Not surprisingly, the district court

agreed with Dr. Wolfgang in finding that the markedly

over-frequent sentencing to death of Negroes convicted of

rape of white women “could not be due to the operation of

the laws of chance.”

Dr. Wolfgang next proceeded to determine whether any

other ascertainable circumstance in these rape cases could

account for the differential sentencing. The data gathered

by the researchers included not merely race and sentence,

but 28 pages of information about each case: characteris

tics of the defendant (age, family status; occupation; prior

criminal record; etc.) and of the victim (age; family status;

19

occupation; husband’s occupation if married; reputation

for chastity); nature of the defendant-victim relationship

(prior acquaintance; prior sexual relations, manner

which defendant and victim arrived at the scene of the of

fense); circumstances of the offense (number of offenders

and victims; place; degree of violence or threat employed;

degree of injury received by victim; housebreaking or con

temporaneous offenses committed by defendant; presence

of members of the victim’s family and threats or violence

employed against them; nature of intercourse; involvement

of alcohol; etc.); and circumstances of the trial (plea,

presentation of defenses of insanity or consent; joinder for

trial of other charges against the defendant or co-defen

dants; whether defendant testified; nature of his legal rep

resentation (retained or appointed); etc.). Every one o f

these variables for which sufficient information could be

gathered from the official records and other sources studied

was analyzed with a view to determining whether it might

explain or account for the phenomenon of racially differen

tial sentencing. Dr. Wolfgang concluded that no non-racial

variable of which analysis was possible could account for

the differential observed. His ultimate conclusion was that

Negro defendants who rape white victims have been dis

proportionately sentenced to death, by reason of race, dur

ing the years 1945-1965 in the State of Arkansas.

The district court disagreed with this ultimate conclu

sion but for reasons that the court of appeals appears to

have thought unpersuasive and which will hardly

scrutiny of the record. See Appendix A, PP. 19a-23a infra.

The court of appeals itself rejected petitioners legal con

tention of racial discrimination, for doctrinal reasons that

are not now relevant; but it obviously thought that Dr.

Wolfeang’s factual finding of discrimination was not re

buttable. It expressly found that “ [tjhere are recognizable

20

indicators . . . that the death penalty for rape may have

been discriminatorily applied over the decades in that large

area of states whose statutes provide for it.”

We have set forth this evidence of arbitrary and dis

criminatory capital sentencing at the outset of our argu

ment for three reasons. First, our specific constitutional

attacks upon the Arkansas death-sentencing procedures by

which petitioner Maxwell was condemned are, in essence:

(1) that the unfettered discretion given Arkansas juries

to select between the penalties of life and death, without

the guidance of standards or control by legal principles of

any sort, allows wholly arbitrary deprivation of human

life, in violation of Due Process, and (2) that Arkansas’

single-verdict practice in capital trials in effect compels the

arbitrary exercise of this arbitrary power because it de

prives the defendant who exercises his privilege against

self-incrimination of the opportunity to present to the

sentencing jury information that is the indispensable pre

requisite of rational sentencing choice. As this Court’s

prior decisions in several differing sorts of cases make

clear, evidence that abuse has in fact occurred has a con

siderable bearing on the issue whether a practice chal

lenged on the ground of lawlessness tending to abuse is sus

ceptible to that challenge. See cases cited in note 3 supra.

Second, there is obviously the most intimate sort of re

lationship between laws maintaining the death penalty,

procedures which allow its imposition arbitrarily, and racial

and caste discrimination in its actual administration. In the

Brief for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the

Indigent, as Amici Curiae, in the companion case of Boykin

v. Alabama, O.T. 1968, No. 642, we have analyzed one as

pect of that relationship: the point that the “public can

easily bear the rare, random occurrence of a punishment

21

which, if applied regularly, would make the common gorge

rise.” (Id., at 55.) “ A legislator may not scruple to put a

law on the books whose general, even-handed, non-arbitrary

application the public would abhor-precisely because both

he and the public know that it will not be enforced generally,

even-handedly, non-arbitrarily.” (Id., at 39; see generally

id., at 35-61.)

This is most obviously the case with regard to the death

penalty for rape. Only sixteen American jurisdictions re

tain capital punishment for that offense. Nevada permits

imposition of the penalty exclusively in cases where rape is

committed with substantial bodily harm to the victim. ̂

The remaining fifteen jurisdictions—which allow their

juries absolute discretion to punish any rape with d ea th -

are all Southern or border States.13 14 * The federal jurisdiction

and the District of Columbia also allow the death penalty

for rape in the jury’s unfettered discretion.16 We think the

13 Nev Rev. Stat. §200.363 (1967). See also §200.400 (1967)

(assault with intent to rape, accompanied with acts of violenc

resulting in substantial bodily harm).

14 The following sections punish rape or carnal knowledge unless

otherwise specified. Ala. Code §§14-395, 14-397 14-398 Becomp.

Vol. 1958); Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-3403, 43-2153 (1964 Repl. Vo . ) ,

see also §41-3405 (administering potion with n 964 Cum

&41-3411 (forcing marriage); Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 ( l yo

S »p p 5 G . Cod, Ann. §§26-1302, 26-1304 (196 C u m -S u p P .h

K y Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963); La. Rev. Stat. Ann §14.42

(1950) (called aggravated rape but slight force is su c

constitute offense; also includes carnal knowledf e) = ^ th

Code §27-463 (1967 Cum. Supp.) ; see also §27-12 (assault witn

intent to rape); Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (Recomp. Vol 1956),

Vernon s Mo" Stat. Ann. §559.260 (1953) ; N O. Gem Stat §14-21

("Recomn Vol 1953) ; Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21, §§1111, 1114, l i t

1958); S.C. Code Ann. §§16-72, 16-80 (1962) (includes assault

' • Q(.+OTTirit tn rane as well as rape and carnal knowledge) , lenn.

S d , A n” W 9 4 7 0 2 39 3703, 39P3704, 39-3706 (1 9 5 5 ,; Tea r « .

Code A nn, arte. 1183,1189 (1 961); Va. Code Ann. §18.1-44 (Repl.

Yol 1960); see also §18.1-16 (attempted rapel>-

is i s u .s .c . §2031 (1964); 10 U.S.C. §920 (1964); D.C. Code

Ann. §22-280i (1961).

22

relationship is obvious between this map of the legal inci

dence of capital punishment for rape and the discriminatory

exercise of juries’ discretion in the actual imposition of

death sentences. It is also worth noting that, outside the

United States, rape is punishable by death only in Malawi,

Taiwan, and the Union of South Africa.1'

The mediating links between the allowability on the

statute books of the death penalty for a crime and its actual

use against the few, arbitrarily selected outcasts yearly

chosen to die are provided by the death-sentencing proce

dures challenged in the present case. It is these procedures

by which laws of apparently uniform application are con

verted in practice into instruments of the most vicious dis

crimination. Their rare, arbitrary and discriminatory use

against the poor and the disfavored insulates the laws, in

turn, against fair public scrutiny and reprobation. At the

same time that a capricious, ad hoc selection of the men to

be killed makes sentencing patterns virtually immune

against judicial control under the Equal Protection Clause,16 17 *

the indefinite and arbitrary character of the sentencing

procedures themselves effectively precludes constitutional

control of particular death sentences rendered by individual

16 United Nations, Department of E conomic and Social A f

fairs, Capital P unishment (S T /S O A /S D /9 -1 0 ) (1968), pp. 40,

86.

17 W e make this point at greater length in the Brief for the

N .A A .C .P . Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and the

National Office for the Rights of the Indigent, as Amici Curiae,

in Boykin v. Alabama, O.T. 1968, No. 642, at 53-55. The opinion

of the district court below presents an obvious instance of judicial

inability to detect racial discrimination where it is concealed under

the additional veil of ad hoc arbitrariness. See A. 37-40. “ Ob

viously, a State can discriminate racially and not get caught at it

if it kills men only sporadically, not too often. By being arbitrary

in selecting the victims of discrimination, a State can get away

with both arbitrariness and discrimination.” Boykin Brief, supra,

at 54.

23

. . . . . H the arbitrariness and discrimination infecting

^ administration of the

^ r ^ ^ C - ^ a r i n e s s a n d

discrimination. . . fi

, . Q to our third point relating to the signifi- Thm brings ns to our t h P discriminstory capi-

CT °tf n c i n r t l e r f w e l i e r has observed that: '-most

tal sentencing. nerDe alitv is a most im-

dramatically when h e m a ^ m Cofli(oi P m is h .

portent ebsmen i ' ^ The Fourteenth Amend-

merit, 7 Jn.x .Jj. _ > aoK|D Plpment 0f justice under the

ConstHutkm^ aneTthe^Due

upon the individual.

What is in issue in this case is the

regularity and to take human

in proceedings by w 1 procedures

fife. Where the consequences o the use of those P

are marked by what the court of appeals belo ^ ^

edged were applied

penalty for ™pe ” 7 , area of states whose statutes

o « r the decades in a„ extensive, painstaking

S £ o ' 1 — study of the application of those pro-

i!The opinion of the court of appeals below

eaJord in L ily well I . rests part of the

the court cannot de.te,ct ned petitioner to die. See A- 59-64.

particular jury winch condemn P bp impossible be-

Any such work of detection woMd o standards governing

cause the entire absence ^ Arkansas al of the propriety

the jury’s sentencing dec* on preclu P^mination which might

S t S t r : T o t S ^ i c a b l e act of impropriety.

24

cedures “ casts considerable doubt upon the quality of

justice in those particular cases throughout the system” 19—

surely the procedures which allow these uses and conse

quences call for the most critical and searching scrutiny of

which courts are capable, to assure consistency with Due

Process. Such scrutiny, as we shall now show, finds Arkan

sas’ capital sentencing procedures drastically deficient.

I.

Arkansas’ Practice of Allowing Capital Trial Juries

Absolute and Arbitrary Power to Elect Between the

Penalties o f Life or Death for the Crime of Rape Vio

lates the Rule o f Law Basic to the Due Process Clause.

Reading the formal provisions o f Arkansas statutory

law governing punishment for the crime o f rape, it is

easy to be lulled into a quite misleading frame o f mind.

The statutes say, in effect, that the penalty for rape is

death, except that the jury may instead elect to sentence

a defendant convicted o f rape to life imprisonment. A r k .

S tat. A n n . $§41-3403, 43-2153 (1964 Repl. vol.), p. 3 supra.

The image conveyed is that death is the ordinary and

usual consequence o f a rape conviction, while the sentence

o f life imprisonment is some form o f extraordinary dis

pensation from the true course o f the law.

This image is as dangerous as it is wrong. Its danger

lies not primarily in the sort o f simplistic legal reasoning

which has sometimes been supposed to be applicable to it:

that a dispensing procedure which grants a gratuitous

benefit, rather than imposing a burden, escapes the con-

19 Dr. Marvin E . W olfgang, testifying on cross examination be

low (Tr. 8 1 ) , quoted by the court of appeals at A . 53. Compare

the phraseology of the court of appeals relative to “ suspicion . . .

with regard to southern interracial rape trials as a group over a

long period of time.” (A . 61-62.)

25

trol of constitutional safeguards designed to protect the

individual from arbitrary and overreaching state actio .

W e do not suppose that this Court would for a momen

countenance any such legal argument." The more insidious

danger of the image is a subtle attitude which it engenders

that the process of decision-making by which ^ ly

is selected as the penalty for crime is not really 7

l l o v Z t The defendant, after all, has been convicted

offense whose punishment is death-although some

few defendants may be exempted from the^ctual neces^ y

of dying This attitude fosters a view of the procedur

tor M e e t in g the men who will live and the men who

t i l l die, from among the total number o f men convicte

^ capital offenses, that is both unreal and irresponsible.

W e hope that there can be no doubt about the facts.

The penalty for rape is not d ea th -in Arkansas or any

where else.7 Only one quarter of the total n u m berof A r

kansas rape convictions analyzed by Dr. W olfgang

Suited in a death sentence.91 The twenty-five per e - t

figure is probably somewhat high even for Arkansas,

20 The Fourteenth Amendment s 9 ?, ^ & state is federally

equality apply not merely to sue ^ processes of dis-

compelled to give its C1̂ lzen®’ choose to give them, however

pensing such benefits as the ^ ate “ y ({on 347 u .S . 483 (1954) ;

gratuitously. Broum v. B o a r d / g 526 (1 9 6 3 ); Cox v. Louisiana,

Watson v. City of M em p h is373 U.S. applied to

379 U S 536, 555-558 (1965). The P ™ P ie TT a 162 (1963 ,

criminal sentencing, ^

and to capital sentencing in ^ i c r d a r \ rkansas-

U.S. 83 (1963). So, even i f t h e the conferring

capital sentencing procedures defendant those procedures

of the benefit of life to a «on^ uf J ^ c S T ^ d Equal Protec-

are nonetheless constrained by the Due Process

tion Clauses, as Brady squarely holds. were

21 See Petitioner’s Exhibit P -4 A p p e n d s B teble ^

fourteen death sentences imposed in a footnote are

22 The fifty-five cases ?ew case! found on the

all of those analyzed by Dr. woiigaug

26

and it appears far higher than the percentage of rape

convicts who are sentenced to death in other states where

the offense is potentially capital.23 It is also true that

the penalty for first-degree murder is not death—in A r

kansas or anywhere in the United States.24 By far the

greater number of first-degree murder convicts, like rape

convicts, are sentenced to some punishment other than

death.25 The testimony of Attorney General Clark, quoted

at p. 12 supra, was neither heedless nor uninformed:

“ Most persons convicted of the same crimes [for which

“a small and capricious selection of offenders have been

put to death” ] have been imprisoned.”

What is important here is not the respective percentages

of men sentenced to life and to death (we shall recur to

their significance shortly), but rather the point that a

highly selective process of making individuating judgments

is occurring, called forth by a state’s statutes which give

its juries the option between a death sentence and some

thing less. This process begins at the point of a defen-

docket books could not be analyzed, because information relating

to the critical variables was not discoverable. These were ordi

narily non-death cases, since official record-keeping in death cases

tends to be more fulsome.

23 See Appendix B, pp. 24a-34a infra.

24 The death penalty for first-degree murder is no longer manda

tory anywhere in the United States. See B edau, The D eath

! Penalty in A merica (1964) 27-30, 45-52.

j Indeed, there are very few crimes in the United States today

j that carry a mandatory death penalty, and those few are for the

j most part of the obscure sort under which no one is ever charged

i (treason, in several states; perjury in a capital case, etc.). See

I ibid. And see Ka lven & Zeisel, T he A merican J ury (1966) 301,

435; Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, 284

A nnals 8 (1952); Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in

Capital Cases, 101 U. Pa . L. Rev. 1099 (1953).

25 See Appendix B, pp. 24a-34a infra.

27

dant’ s conviction for a capital crim e; it applies to all

defendants so convicted; and it involves the m aking of

differentiations between them, choosing those ones am ong

their total number whose lives are to be taken.

The question is not w orth debating whether the F o u r

teenth Am endm ent’s basic requirem ents o f regularity ,

fundam ental fairness, and even-handedness operate as

constraints upon such a process of ° T i T s V

they do. W ith ersp oon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (19 ) .

B ra d y v. M aryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963). And see Spech t

v. P a tterson , 386 U.S. 605 (1967); M em p a v. R h a y , ^

U.S. 128 (1967); Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535

As Judge Sobeloff has written in another connection:

“ Under our constitutional system, the payment

which society exacts for transgression of the law does

not include relegating the transgressor to arbitrary

and capricious action.” (Landm an v. P eyto n , 370 F.2d

135, 141 (4th Cir. 1966).)

The issue is whether the selection process used by the

State o f A r k a n s a s -a n d by m ost other A m erican states

which retain capital punishm ent, we m ust a d d -c o m p o r ts

with the relevant Fourteenth A m endm ent constraints o