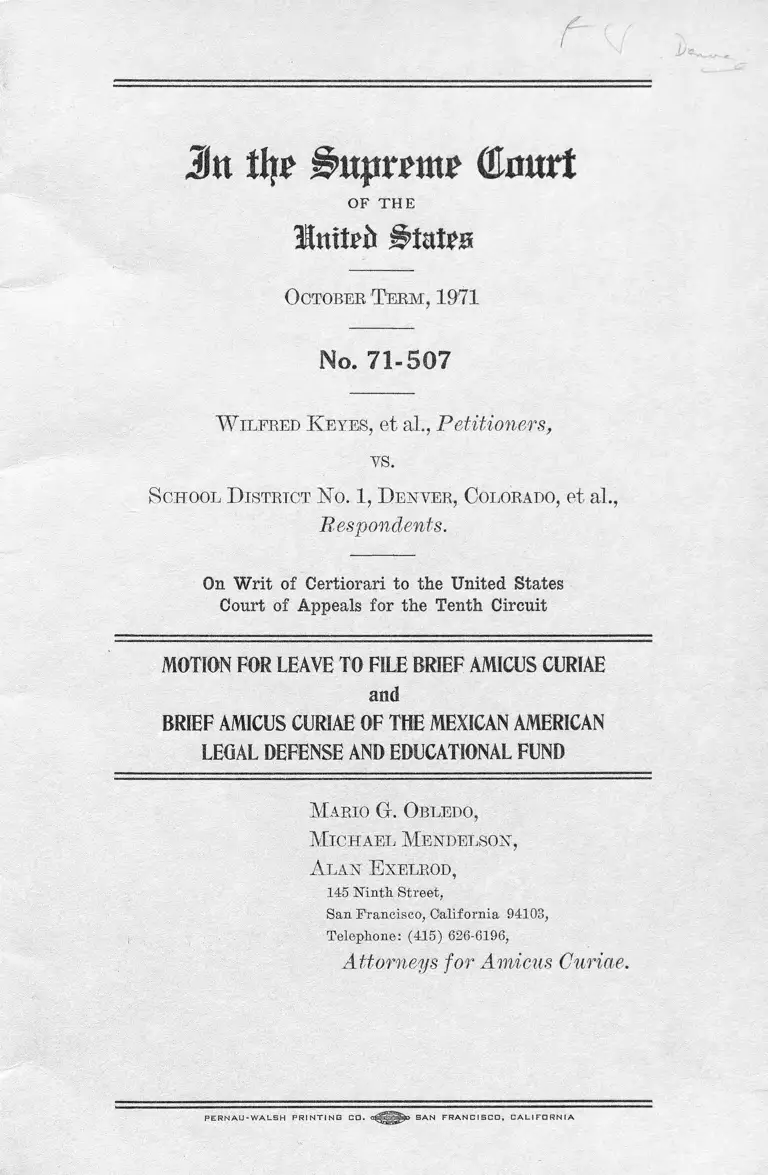

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 4, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief Amici Curiae, 1972. 1cf839ff-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6ceb58a1-fa9a-45fa-8141-68b4cf821c4e/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Jtt % $uprettt? (Eourt

OF THE

O cto ber T e r m , 1971

No. 71-507

W il f r e d K e y e s , e t a l., Petitioners,

vs.

S c h o o l D is t r ic t N o . 1, D e n v e r , C olorado , e t a l.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

and

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

M ario G. O bled o ,

M ic h a e l M e n d e l s o n ,

A l a n E x e le o d ,

145 Ninth Street,

San Francisco, California 94103,

Telephone: (415) 626-6196,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

P E R N A U - W A L S H P R I N T I N G C D . S A N F R A N C I S C O , C A L I F O R N I A

Jtt % g’uprem? Qhrart

OF THE

States

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No. 71-507

W il f r e d K e y e s , e t a l., Petitioners,

YS.

S c h o o l D is t r ic t N o . 1, D e n v e r , C olorado, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund moves this Honorable Court for leave

to file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae.

Petitioners’ attorney has granted consent for the

filing of this brief. The consent of Respondents’ at

torney was requested but refused.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund (MALDEF) is a non-profit corporation

organized under the laws of the State of Texas whose

2

purpose is the protection of the civil rights of Spanish

surriamed people in the Southwest. In pursuance of

this purpose MALDEF has represented clients in

matters involving employment discrimination, voting

rights, and public accommodations discrimination.

However, it is in the area of improving the educa

tional process that MALDEF has devoted much of

its resources.

Although Mendez v. Westminster School District,

64 F.Supp. 544 (C.D. Cal.) air'd 161 F.2d 774 (9th

Cir. 1947) held that school segregation against Chi

canes* violated the equal protection clause, there has

never been a holding by this Court to that effect. The

Chicane community in the Southwest continues to

attend segregated inferior schools.

This community believes that a quality educational

program in an integrated setting provides the only

hope for equal educational opportunity. As a result

of this mandate MALDEF is counsel for Chicano

parents and children in lawsuits throughout the South

west including Dallas, Houston, Austin, El Paso and

New Braunfels, Texas; Fullerton, California; Glen

dale, Arizona; Portales, New Mexico. These cases;

attack segregated schools and discriminatory treat

ment. Consequently, the- whole Chicano community and

MALDEF are vitally interested in the outcome of

this case.

*His.pano is the word used in the record to denote Spanish

speaking people in Denver. However, Chicano is the preferred

name for Spanish speaking people in the Southwest.

3

MALDEF requests permission to file this brief in

order to present an issue only touched upon by

Petitioners; why Chicanos are an identifiable class

for Fourteenth Amendment purposes. In addition,

Amicus believes the constitutional wrongs which Chi

canos have suffered over the years need elucidation

before this Court.

Wherefore, MALDEF prays that this Court grant

leave to file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae.

Dated, May 4, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

M ario Gr. O bled o ,

M ic h a e l M e n d e l s o n ,

A i .a u E x elr o d ,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

Subject Index

Interest of the amicus curiae ..................................................... 5

Summary of the argument ......................................................... 6

Argument ...................................................................................... 7

I. Introduction .................................... 7

II. Chieanos comprise an identifiable class for purposes of

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment .................................................................................... g

A. The Chicano in the Southwest has suffered social,

economic and political discrimination ...................... 8

B. The courts have held Chieanos to be a class pro

tected by the equal protection clause ...................... 11

III. Chicano students have been segregated and denied an

equal educational opportunity in the Denver School

System and therefore appropriate remedies must be

created to alleviate this denial of equal protection.. . . 14

A. Chieanos in the State of Colorado and the City of

Denver have suffered the same discriminatory

treatment as Chieanos in other parts of the

Southwest .................................................................. 14

B. Chieanos have been segregated and denied an

Page

equal educational opportunity in Denver ............ 15

C. The trial court correctly found that inequalities

existed in the minority schools, but it also should

have ruled that racial and ethnic isolation was

caused by school district policies and practices.. . . 19

D. Comprehensive desegregation is an appropriate

remedy to correct the existing constitutional

wrong .......................................................................... 20

E. The trial court correctly ordered a program for

equalization of educational opportunities.............. 25

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 27

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

Alvarado v. El Paso Independent School District, 445 F.2d

1011 (5th Cir. 1971) ............................................................. 18

Beare v. Smith, 321 F.Snpp. 1100 (S.D. Tex. 1971) .......... 9

Beltran v. Patterson, U. S. District Court for the Western

District of Texas, No. 68-59-W ........................................... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .......... 11

Cantwell v. Conn., 310 U.S. 296 (1940) ..................................... 24

Castro v. State, 2 Cal. 3d 223, 466 P. 2d 244 (1970) .......... 9,12

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F. Supp. 203 (S.D.N.Y.

1971) aff’d ..... F. 2d ..... (2nd Cir. 1972) ...................... 13

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 324

F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970) ................................................. 8,12

Clifton v. Puente, 218 S.W. 2d 272 (Court of Civil Appeals

Tex. 1948) ................................................................................ 8

Crawford v. Los Angeles Unified School District, Superior

Court for the County of Los Angeles, California, No.

822854 ...................................................................................... 24

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U. S. 470 (1968) .................................................................. 23

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954) ..................8,11,12,13

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School District, United

States District Court for the Northern District of Cali

fornia, No. C-70 1331 SAW ................................................. 24

Jones v. Albert Mayer & Co., 392 U. S. 409 (1968) .......... 7

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1 (1967) ................................. 24

Marquez v. Ford Motor Co., 440 F. 2d 454 ( 8th Cir. 1971) 9

McDonald v. Board of Election Comm’rs, 394 U. S. 802

(1969) ...................................................................................... 24

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184, 192 (1963) .............. 24

Muniz v. Beto, 434 F. 2d 697 (5th Cir. 1970) .................... 12

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964) ..... 24

T able of A u thorities C ited

Perez v. Sonora Independent School District, United States

District Court, for the Northern District of Texas, No.

CA-6-224 .................................................................................. 8

Regester v. Bullock, United States District Court for the

Western District of Texas, No. A-71-CA-143 ................9,10,12

Rodriguez v. San Antonio Independent School District, 337

F. Supp. 280 (W.D. Tex. 1972) ......................................... 13

Ross v. Eckels, 434 F. 2d 1140 (5th Cir. 1970) ..................23,24

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ............................... 24

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees, 328 F.

Supp. 155 (C.D. Cal. 1971) ............................................... 13

Tasby v. Estes, United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas, No. 3-4211-C ......................... 13, 24

Urquidez v. General Telephone Co., 2 EPD 1(10,145 (D.C.

N. Mex. 1970) ........................................................................ 9

U.S. v. Jefferson Co., 380 F. 2d 385, 39364 (5th Cir.

1967) ........................................................................................ 25

U.S. v. Longshoremen’s Union, 4 EPD ft7687 (S.D. Tex.

1970) ..................................... . . . ............................................ 9

U.S. v. Texas, 252 F. Supp. 234 (W.D. Tex. 1966) .......... 9

U.S. v. Texas, United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Texas, No. 5281 (E.D. Tex. 1971) .................. 13

U.S. v. Texas Education Agency (Austin I.S.D.), United

States District Court for the Western District of Texas,

No. A-70-CA-80 ....................................................................... 13,24

ii i

Pages

Other Authorities

Burma, John—Mexican Americans in the United States,

1970 .......................................................................................... 9

Carter, Thomas—Mexican Americans in School: A History

of Educational Neglect, 1970, pp. 67-74 ............................. 10

Coleman, James Dr.—Equality of Educational Opportunity 21

Colorado Commission on Spanish Surnamed Citizens, Report

to the Colorado General Assembly—The Status of Spanish

Surnamed Citizens in Colorado, Jan. 1967 ....................... 14,15

Grebler, Moore, Guzman—The Mexican American People:

The Nation’s Second Largest Minority, p. 1970 ................ 15

Hearings Before the Select Committee on Equal Educa

tional Opportunity of the U.S. Senate, 91 Congress, Sec

ond Session, Part 4, Mexican American Education, Aug,

18-21, 1970 .............................................................................. 9

Reynoso, Cruz—La Raza, The Law and the Law Schools,

1970 U. Tol. L.R. 809 (1970) ............................................... 9

Salinas, Guadalupe—Mexican Americans and Desegregation

of the Schools in the Southwest, 8 Houston L.R. 929

(1971) ...................................................................................... 9

Schmidt, Fred—Spanish Surnamed Employment in the

Southwest, U.S. Civil Rights Commission ......................... 9,15

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Mexican Americans and

the Administration of Justice in the Southwest, 1970___ 9

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Mexican American Study

Project Report No. 1 ............................................................. 9

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Unfinished Revolu

tion, Mexican American Study Project Report No. 2. .. . 10

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions

Arizona Revised Stats., Sec. 16-101 ...................................... 9

Bilingual Education Act, 20 TJ.S.C., Section 880 .................. 26

United States Constitution:

14th Amendment, §1 (equal protection). .6, 8,11,12,14, 22, 24

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............................. 12

iv Table oe A uthorities Cited

Pages

In % g»upmn? (Enurt

OF THE

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No. 71-507

W il f r e d K e y e s , e t a l., Petitioners,

vs.

S c h o o l D is t r ic t N o . 1, D e n v e r , C olorado, e t a l.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund is a non-profit corporation established

in 1968 under the laws of the State of Texas. Its

purpose is to represent Spanish surnamed people in

the Southwest whose civil rights are being violated.

MALDEF offices are located in San Francisco, Los

Angeles, San Antonio and Denver.

A primary goal of the organization since its in

ception has been to end the patterns of ethnic isolation

and inferior schools that pervade the Southwest. To

6

this end MAL I) EF is representing clients throughout

the Southwest. See the Motion for Leave to File an

Amicus Brief. Since it is likely that these eases will

be strongly affected by the outcome of this ease, MAL-

DEF has an immediate direct interest in this lawsuit.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Amicus curiae make the following argument:

Chieanos in the Southwest are subject to deeply

ingrained patterns of economic, political and educa

tional discrimination. As a result, they are entitled to

be considered an identifiable class for equal protection

clause purposes. The demographic data and the evi

dence in this record prove that Chieanos in Denver

have been discriminated against in this traditional

Southwestern manner.

The District Court erred in refusing to find that,

Chieanos had been segregated by policies and prac

tices of the Denver school district. The record showed

a consistent unlawful pattern of discrimination in

student and faculty assignment practices. The Dis

trict Court correctly ruled that inequalities in educa

tion existed at minority schools. However, it erred in

distinguishing between schools that had over 70'% of

one minority and schools that had over 70|% of the

two minorities, Negro and Chicano, for purposes of

relief. The purposes of desegregation are not accom

plished by integrating two economically and educa

tionally disadvantaged minority groups.

7

The Court of Appeals erred by rejecting the equal

ization plan adopted by the District Court. The Dis

trict Court’s plan in regard to Spanish language

training, teaching of Chicano culture and use of

teacher aides was an appropriate use of his equitable

powers to correct a proven constitutional wrong.

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

The Chicano1 is the forgotten minority.2 He is the

largest minority group in the Southwestern United

States, He is the field hand. He is the janitor. Much

as the Negro was. foreeably made part of this nation

as a slave and still today bears the badges of this

servitude, Jones v. Albert Mayer & Go., 392 U.S. 409

(1968), so too were Chieanos foreeably made part of

this nation—they were the vanquished remnants., con

quered heirs of the Spanish Conquistadores, Their

vanquishment has made them exiles in their own land

—the dominant Anglo3 society has treated them as

second class citizens,

Chieanos in Denver and the Southwest generally

receive an inferior education, suffer occupational dis

crimination, and are deprived of crucial political

rights and power that would allow them to change

1Hispano. is the word used in the record to denote Spanish

speaking people in Denver. However, Chicano is the preferred

name for Spanish speaking people in the Southwest.

2The Southwest for purposes of this brief includes Arizona,

California, Colorado, New Mexico and Texas.

3An Anglo is a non-Spanish surname! member of the Caucasian

race.

8

their socio-economic status through the political proc

ess. The opinion of the courts in this case does not

overtly describe this exclusion of the Chicano. The

purpose of this brief is to inform the Court of the

plight of the Chicano and to help the Court under

stand why the remedies of desegregation and equal

ization are so important to him.

II. CHICANOS COMPRISE AN IDENTIFIABLE CLASS FOR PUR

POSES OF THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

A. The Chicano in the Southwest Has Suffered Social, Economic

and Political Discrimination

The Chicano has been subjected to the traditional

methods used to create second class citizenship. He

has been segregated in swimming pools,4 hospitals,5

movie theaters,6 toilet facilities.7 Racial and ethnic

restrictive covenants in real estate deeds regularly

included Chicanes.8 The result was segregated barrios9

and little opportunity to move into Anglo neighbor

hoods.

The administration of justice has been infected

with the evil of second class citizenship for the Chi-

4Beltran v. Patterson, U. S. District Court for the Western

District of Texas, No. 68-59-W.

^Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District, 324

F.Supp. 599, 613 (S.D. Tex. 1970) appeal pending1.

6Perez v. Sonora Independent School District, U. S. District

Court for the Northern District of Texas, No. CA-6-224.

7Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 480 (1954).

8Clifton v. Puente, 218 S.W.2d 272 (Court of Civil Appeals

Texas 1948). ref.

9That part of town where Chicano homes are concentrated.

9

caiio.10 The Texas Rangers hired their first Chicane

two years ago. There are few Chicane district attor

neys, judges,11 or even law students.12 Employment

discrimination has been documented extensively.13

Political rights were for a long period suppressed

but only recently have the courts opened up; the

political process.14

I t is in the area of education that the; Chicane

suffers extraordinary deprivation. Segregation prac

tices are widespread.15 16 The reasons for the discrim

ination are much like those used to justify segregation

10U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Mexican Americans and the

Administration of Justice in the Southwest, 1970.

11Ibid, p. 48.

12Reynoso, Cruz, La Raza, The Law and the Law Schools, 170

U.Tol.L.R. 809 (1970).

13Schmidt, Fred, Spanish Surnamed Employment in the South

west published by U. S. Civil Rights Commission. Burma,, John,

Mexican Americans in the United States, 1970 p. 147-208. For

case law see Marquez v. Ford Motor Co., 440 F.2d 457 (8th

Cir. 1971). Urquidez v. General Telephone Co., 2 EPD 1(10,145

(D.C. N.Mex. 1969), U. S. v. Longshoremen’s Union, 4 EPD

1J7687 (S.D. Tex. 1970).

14Texas had a poll tax which keep the Chicano poor from the

polling place, U. S. v. Texas, 2,52 F.Supp. 234 (W.D. Tex. 1966)

and a restrictive registration procedure which excluded Chicanes,

Beare v. Smith, 321 F.Supp. 1100 (S.D. Tex. 1971). California

had literacy requirements which prevented even thosfe' fully liter

ate in Spanish from voting, Castro v. State, 3 Cal.3rd 223, 466

P.2d 244 (1970). Arizona similarly had stringent literacy re

quirements. Ariz. Revised Stat. §16-101. See also Regesier v.

Bullock, U. S. District Court for the Western District of Texas,

No. A-71-CA-143 (Holding multi-member state representative

districts discriminated against Chicanes).

16For information about the isolation of Chicano school children

see U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Mexican American Study

Project Report No. 1; Salinas, Guadalupe, Mexican Americans

and the Desegregation of Schools in the Southwest, 8 Houston

L.R. 929 (1971); Hearings before the Select Committee on Equal

Educational Opportunity of the U. S. Senate, 91 Congress Second

Session, Part 4, Mexican American Education, Aug. 18-21, 1970.

10

in the South,16 The result of this segregation with

its creation of inferior status has been a dismal record

of achievement in the schools. In 1960 in the South

west the median years of school of Chicanos 25 years

and older was 7.1 as compared to 12.1 for Anglos and

9.0 for non-whites,16 17 Drop-out rates for Chicanos even

today are considerably higher than for any other

racial or ethnic group.18 19 Later portions of this brief

will re-veal that the Denver school system fits too

easily into- this Southwestern pattern of segregation

and inferior education.

The Chicano is living this legacy of a conquered

people. Applying the words of a Texas Federal Court

to the Southwest generally:

“Because of long standing, educational, social,

legal, economic, political and other widespread

and prevalent restrictions, customs, traditions,

biases and prejudices, some of a so-called de jure

and some of a so-called de facto character, the

Mexican American population of Texas . . . has

historically suffered from and continues to suffer

from, the results and effects of invidious discrimi

nation and treatment in the fields of education,

employment, economies, health, politics and

others,”18

16 Carter, Thomas, Mexican Americans in School; A History of

Educational Neglect. 1970, pp. 67-74.

17IMd., p. 23.

18U. S. Commission on Civil Eights, The Unfinished Revolution,

Mexican American Study Series Part II 1971, p. 20.

19Regester, supra, Note 14, p. 45.

11

B. The Courts Have Held Chicanos To Be A Class Protected

By The Equal Protection Clause

This Court, shortly before deciding the landmark

case for Negro Americans, Brown v. Bd. of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954), recognized for the first time that

Chicanos are also entitled to Fourteenth Amendment

protections. In Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475

(1954), the total exclusion of Chicanos from grand

juries was proven. The Court in finding this uncon

stitutional stated:

“Throughout our history differences in race and

color have defined easily identifiable groups which

have at times required the aid of the courts in

securing equal treatment under the law. But com

munity prejudices are not static, and from time

to time other differences from the common norm

may define other groups which need the same

protection. Whether such a group exists within a

community is a question of fact. When the ex

istence of a distinct class is demonstrated, and it

is further shown that the laws, as written or as

applied, single out that class for different treat

ment not based on some reasonable classification,

the guarantees of the Constitution have been vio

lated. The1 Fourteenth Amendment is not directed

solely against discrimination due to a Two-class’

theory—that is, based upon differences between

‘White’ and ‘Negro’.” 347 U.S. at 478.

The Chieano community was at first slow to use the

potent combination of Hernandez and Brown to> rem

edy the pervasive discrimination described in Section

I I A above. But in recent years, one court after an

other has held that the constitutional guarantees of

12

the Fourteenth Amendment apply to Chicanos no less

than to Negroes. For example, the Hernandez rule

regarding discrimination against Chicanos in the com

position of grand juries has been applied to a large

Texas city, Muniz v. Beto, 434 F.2d 697 (5th Cir.

1970). Chicano political rights are now being protected

under the Fourteenth Amendment, see Reg ester, su

pra, Note 14, Castro v. State, supra, Note 14. Em

ployment discrimination under Title V II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 has been proven, see eases cited

in Note, 13, supra.

Because education is at the root of many of the

socio-economic problems of the Chicano, there has

been considerable litigation attempting to undo school

segregation. Courts have been most diligent in elabo

rating upon the reasons for considering Chicanos an

identifiable class for equal protection purposes in

these cases. In Cisneros v. Corpus Christi I.S.D., 324

F.Supp. 599, 607 (SJD. Tex. 1970) appeal pending,

the Court observed:

“. . . [I] t is clear to this Court that these people

for whom we have used the word Mexican Amer

icans to describe their class, group, or segment

of our population, are an identifiable ethnic

minority in the United States, and especially so

in the Southwest [and] in Texas, . . . This is not

surprising; we can notice and identify their phys

ical characteristics, their language, their pre

dominant religion, their distinct culture, and, of

course, their Spanish surnames. And if there

were any doubt in this court’s mind, this court

could take; notice, which it does, of the congres

sional enactments, government studies and com

missions on this problem.”

13

See also U.S. v. Texas, LT.S. District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas, No. 5281 (E.D. Tex. 1971) ;

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees,

328 F.Supp. 155 (C.D. Cal. 1971); Alvarado v. El

Paso Independent School District, 445 F.2d 1011 (5th

Cir. 1971). Even where courts have refused, to find

that de jure segregation has been practiced against

Chicanes, they have held that Chicanos are an identi

fiable minority group, cf. Tasby v. Estes, U.S. Dis

trict Court for the Northern District of Texas, No.

3-4211-C, appeal pending. U.S. v. Texas Education

Agency (Austin I.S.D.), U.S. District Court for the

Western District of Texas, No-. A-70-CA-80, appeal

pending.20

The legal reality of the Chicanos’ situation in the

Southwest has seen courts remedy past legal depriva

tion only recently. Political, economic and educational

freedoms have only now begun to receive constitu

tional protection by the courts. A holding that Chi

canos are not a separate identifiable class would have

widespread repercussions in all areas of the law as it

is developing in the Southwest. Eor these reasons

Amicus urge this Court to reaffirm Hernandez•

to hold that Chicanos are, historically, a deprived

class, and are thereby, an identifiable group,

entitled to receive protection under the Fourteenth

Amendment.

20Sehool financing systems have also discriminated against Chi

canos. Rodriguez v. San Antonio I.S.D., 337 F.Supp. 280, 282

(W.D. Tex. 1972) appeal pending U. S. Supreme Court. See also

Chance v. Bd. of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203 (S.D.N.Y. 1971)

aff’d ..... F.2d ..... (2nd Cir. 1972) where an examination for an

administrative position in the public schools was held to dis

criminate against Puerto Ricans.

14

III. CHICANO STUDENTS HAVE BEEN SEGREGATED AND

DENIED AN EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITY IN THE

DENVER SCHOOL SYSTEM, AND THEREFORE APPROPRI

ATE REMEDIES MUST BE CREATED TO ALLEVIATE THIS

DENIAL OF EQUAL PROTECTION.

A. Chicanos In The State of Colorado And The City of Denver

Have Suffered The Same Discriminatory Treatment As Chi

canos In Other Parts of The Southwest

The most comprehensive study about the condition

of the Chicano in Colorado ever written concludes :

“In general, the average Spanish surnamed res

ident. of Colorado belongs to most of the following

minority groups and possesses the traits associ

ated with these groups.

1. The poor;

2. The poorly educated;

3. The unhealthy;

4. The victims of discrimination;

5. The illhoused;

6. The rural folk;

7. The Spanish-Mexican-American tradition;

8. The law violator ;

9. The legally unprotected;

10. The politically unrepresented.”21

These conclusions are borne out by the available data.

In the area of employment, Chicanos are under

represented at all levels of the job rolls and over

21Colorado Commission on Spanish-Surnamed Citizens, Report

to the Colorado General Assembly: The Status of Spanish Sur

named Citizens in Colorado, Jan. 1967, p. 15.

15

represented on the unemployment rolls.22 “Employ

ment rosters within Colorado public institutions gen

erally show a very low incidence of Spanish-surnamed

employees.” “I t is clear from this data [on munici

palities] that the Spanish-surnamed population is ex

tremely under-represented in public employment in

general.”23 A recent study shows that in Denver the

same pattern prevails. Although 9.3% of the total

work force in three of the most important industries

in Denver are “Officials and Managers”, only 1.3%

of the Chicanes are in this category. 82% of employed

Chieanos in these industries are in blue collar jobs,

nearly twice the percentage in the total work force.24

Health conditions reveal “a serious differential be

tween the Spanish-surnamed and the general popula

tion.”25 Mortality rates show that Chieanos die on an

average of ten years earlier than the rest of the

population.26

Housing segregation in Denver is acute and is worse

than the Southwest generally.27

B. Chieanos Have Been Segregated and Denied An Equal Edu

cational Opportunity in Denver

The education afforded Chicano students in the

defendant school district mirrors the inferior educa

22Ibid., p. 27, “The figures show that the percent of all unem

ployed which is Spanish surnamed is, in most countries, signifi

cantly higher than the percent of the labor force which is

Spanish-surnamed. ’ ’

™IMd., p. 35.

24Schmidt, supra, Note 13, p. 16.

25Colorado Commission, supra, p. xviii.

26Schmidt, supra, p. 55.

27Grebler, Moore, Guzman, The Mexican American People: The

Nation’s Second Largest Minority, 1970, p. 277.

16

tion provided in the Southwest generally. Ethnic iso

lation and unequal treatment pervade the Denver

school system.

Chicanos are in large part isolated from the ma

jority Anglo community. Several schools are almost

totally Chieano (App. 2040a). Many Chicane children

attend school with Negroes, the other disadvantaged

minority in Denver. 31.6% of Chieano elementary

students attend schools that are over 75% minority

(App. 2038a). 28 out of 93 elementary schools in the

district are over 50% minority (App, 2040).

The sources of this racial and ethnic isolation are

the policies and practices of the defendant school

district. The district assigned minority faculty to

minority schools because the Anglo community re

fused to permit these teachers in the Anglo schools

(303 F'.Supp. at 294). The district maintained a

neighborhood school policy that was shot through with

optional zones to allow Anglo children to escape min

ority schools, The district constructed the predomin

antly minority New Manual High School with just

enough capacity to insure that it would remain a

minority school. The district maintained enrollment

at minority schools under capacity while overcrowding

Anglo schools to avoid mixing the two groups (313

F.Supp. at 71).

Whatever nonracial explanations are conjured up

for these actions, the simple fact remains, the op

erative effect of the school board assignment policies

was to exclude Negroes and Chieano® from Anglo

schools and to place Negroes and Chicanos together in

predominantly minority schools.

17

Along with segregation, the school district provided

distinctly unequal educational opportunities for mi

nority students.

Looking first to teacher assignment policies, the

record reflects that in 1968: 1. The minority schools

had almost twice as many probationary teachers as

the Anglo schools (App. 2062a); 2. The minority

schools had less than one half as many teachers with

10 or more years experience in the Denver public

schools than the Anglo schools (App. 2064a) ; 3. The

median years of Denver public school experience of

teachers in minority schools was less than half that

of Anglo schools (App. 2066a).

Turning next to physical facilities, Anglo schools

are on the average half the age of minority schools

(App. 2070a,). Although these schools were built at

a time when there was much more land available in

urban areas than at present, minority schools have

considerably less land per child than Anglo schools

(App. 2068a).

In the area of curriculum, the Voorhees Report

(Plaintiff’s Exhibit 20) implies that the existing uni

form curriculum throughout the school system met

the needs of the Anglo majority but not the needs of

the disadvantaged minorities. The same treatment in

this ease was in fact “unequal” treatment.

The results of this disparity in treatment are pre

dictable. Achievement levels at the minority schools

fall far below those at the Anglo schools at every stage

of the education process.

18

Stanford A chievement Tests, April 1969

Mean Scores B y School and Grade

(A p p . 2102a, 2104a)

Grade Level A t W hich Tests W ere A dministered

2.6 3.6 4.6 5.6 6.6

Average Grade Level

Score for Minority Schools 2.27 2.85 3.58 4.42 4.91

Average Grade Level

Score for Anglo Schools 3.12 4.26 5.44 6.53 7.01

One need only compare Plaintiff’s Exhibit 375 (App.

2094a.) with Plaintiff’s Exhibit 372 (App. 2088a),

which show that achievement levels at the minority

schools in Northwest Denver are considerably lower

than at Anglo schools in the Southwest, to understand

fully the impact of unequal educational opportunity.

If more proof is necessary, let us check the ultimate

test of a school system, the extent to which students

complete high school. I t is here that the human

tragedy resulting from unequal treatment and low

achievement are reflected. The Chicano drops out

earlier and in greater numbers in Denver than either

of the other two groups. By seventh grade some Chi

cano students are lost from the schools and by twelfth

grade, the exodus is a torrent.

School P opulation Statistics B y Race, and

E thnic Origin for 1968

Chicano Negro Anglo Other

No. % No. % No. % No. %

Sr. High School

(Grades 10-12) 2,996 12.8 2,447 10.4 17,821 76.1 160 .7

Jr. High School

(Grades 7-9) 3,629 19.5 2,888 15.5 11,886 64.0 173 1

Elementary School

(K-6) 11,986 22.0 8,304 15.2

(These figures are from App. 2038a).

33,678 61.7 608 1.1

19

Amicus has demonstrated that Chicanes in the

Southwest are subject to the same kind of overt and

subtle differences in treatment as Negroes in this

country. The discrimination documented above proves

that the Denver school system is but a microcosm of

the educational system of the Southwest.

C. The Trial Court Correctly Found That Inequalities Existed

In The Minority Schools, But It Also Should Have Ruled

That Racial And Ethnic Isolation Was Caused By School

District Policies and Practices

The trial court concluded that except for those

schools dealt with in the 1969 school hoard resolutions,

nonracial explanations for ostensibly segregating prac

tices prevented a finding of de jure segregation.

Amicus urges this Court to reverse this finding. Racial

and ethnic motivations pervaded the decisions of the

Denver school board. The evidence on inequalities in

school services is self-explanatory. The trial court

additionally found that the school board was aware

of the effect of its policies but practiced “eye-closing”

and “head-burying” (313 F.Supp. at 76) to avoid in

tegration. Further, the Court found that the decisions

of the school board were dictated by a consensus of

the community (313 F.Supp. at 73). However, this,

controlling Anglo28 consensus was in part responsible

for the existing housing segregation.29 Because the

primary contributors to the consensus were those who

helped establish segregated housing patterns, their

intent to segregate should be imputed to the board.

28Negroes and Chicanos never seemed to be a part of this con

sensus. (313 F. Supp. at 70, 71)

29“ [I]f cause or fault has to be ascertained it is that of the

community as a whole in imposing, in various ways, housing

restraints.” (313 F. Supp. at 75)

20

In regard to unequal educational opportunities the

trial court concluded :

“The evidence in the case at bar establishes, and

we do find and conclude, that an equal educational

opportunity is not being provided at the subject

segregated schools within the District. . . . The

evidence establishes this beyond any doubt.”

Amicus agrees with this determination. However,

the court erred in leaving out of its list of schools

those where the combined total of Negro and Chieano

students was over 70% but neither of the groups was

individually over 70%. The same factors of teach

er turnover, inferior physical facilities, and lower

achievement are present in these over 70% black and

Chieano schools (App. 2122a, 2124a), and therefore

the same relief should be afforded.

The Court of Appeals reversed the trial court with

regard to both the desegregation and equalization

remedies. It, did not deny the existence of the inequali

ties but by using the wrong constitutional standard

and disregarding these inequalities the appellate

court found no state action. The error in the appel

late court’s reasoning is manifest and Amicus defers

to Petitioners’ argument on this issue (Brief of Pe

titioners, p. 114).

D. Comprehensive Desegregation Is An Appropriate Remedy

To Correct The Existing Constitutional Wrong

After hearing extensive evidence on the issues of

relief the trial court concluded:

“. . . The only feasible and constitutionally ac

ceptable program—the only program which fur

21

nishes anything approaching substantial equality

—is a system of desegregation and integration

which provides compensatory education in an

integrated environment” (313 F.Supp. at 96).

This decision was clearly correct and within its equi

table powers.

Those reasons normally supporting desegregation as

a remedy exist in full force in Denver. Students will

have heterogeneous, cross-cultural experiences, physr

ical facilities at the inferior school will improve,

teacher turnover will be reduced and the psychological

stigma attached to attending an inferior school will

be eliminated. For the Chicano, an important addi

tional reason exists for desegregation. He often conies

to school speaking Spanish as his mother tongue. To

isolate him with other Spanish speaking students as

the school district has done in the Elmwood, Fairmont

and Fairview Elementary Schools deprives him of the

opportunity to use his adopted language, English.

That is not to say that his retention and development

of Spanish should not be encouraged; however, he

will never receive a balanced language learning ex

perience in his most crucial years unless he is placed

in a position to use Spanish on a regular basis. Often

times the only chance he has to speak English is at

school because at home, the language in common use

is Spanish.

The evidence in the record supports desegregation

as a remedy for Chicanos. The testimony of Dr. James

Coleman, author of Equality of Educational Oppor

tunity, found that both Chicanos and blacks did better

22

in a school with students of diverse socio-economic

backgrounds. (App. 1534a).

Amicus strongly supports the position of Petitioners

that the trial court should have ordered system-wide

desegregation. Excluding two race inferior schools

from relief is simply not a decision grounded on the

reality of Denver. Chieanos and blacks need cross-

cultural interaction with Anglos, the dominant com

munity in Denver. Maintaining minority schools con

tinues the stigma attached to the schools. Teachers

will continue to want to escape, physical facilities will

remain inferior and peer group high-achievers will

remain absent from these schools. Placing two

economically and educationally disadvantaged groups

together does not satisfy the policy underlying de

segregated education. Professor Coleman found that

a school population comprised of two disadvantaged

minority groups is ordinarily as inferior as a school

with one segregated minority, (App. 1538a).

In view of the facts set forth in Section I I B of

this brief, Chieanos in the district are themselves

directly entitled to affirmative desegregation relief.

However, even if this Court finds that the school

board has practiced de jure discrimination against

blacks only, with the result that blacks but not Chi-

canos are entitled to affirmative relief, neither sound

policy nor the Fourteenth Amendment would permit

treating Chieanos as Anglos nor leaving Chieanos

completely out of the desegregation process.

Treating Anglos as Chieanos will result in continued

segregation of minorities. Because of the proximity

23

of Cliicaiio and Negro neighborhoods in Northeast

Denver it will be poor Negros and Chicanos. who. are

integrated together. Of course, none of the benefits

of desegregation will accrue. The effect of such a

decision will be to maintain all Anglo schools.30

The consequences of considering Chicanos as Anglo

can be seen in the Houston desegregation litigation,

Ross v. Eckels, 434 F.2d 1140, 1148 (5th Cir. 1970).

That Court ordered 14 elementary schools paired on

a black-white basis. Chicanos were considered white.

The result of these pairings was that 13 of the 14

schools were over 80% minority (see Appellant's

brief, Ross, Rodriguez, U.S. v. Eckels, U.S. Court of

Appeals, No. 71-2357, appeal pending from denial of

intervention to Chieano plaintiffs).

Recognizing that Chicanos are an identifiable group

for equal protection purposes, but leaving them out

of a black-Anglo desegregation plan results in differ

ent problems. There is the continuing stigma attached

to Chicanos of going to isolated second class schools.

In addition, the benefits accruing to the black, Anglo

and Chicane children from the mutual understanding

engendered by cross-cultural interaction would be lost.

Isolating Chicanos from blacks and Anglos also

raises serious equal protection questions. No one could

dispute that if a school board moving on its own ini

tiative to end a supposedly de facto segregation situ

ation were to desegregate blacks and Anglos to the

S0Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 470 (1968) prescribed a realistic approach to desegregation,

an approach that actually works.

24

exclusion of the Chicanos, it would violate the mandate

of equality required by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The school board would be treating a discreet, iden

tifiable group differently without any compelling rea

sons for doing so-.31 It would be ironic if the courts,

under the guise of remedying discrimination against

one minority could permissibly discriminate against

another. And the courts are not of course immune

from the requirements of the equal protection clause.

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964);

Cantwell v. Conn., 310 U.S. 296 (1940); cf. Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

This Court’s resolution of desegregation issues in

a multicultural school district is crucial. Situations

similar to Denver exist; throughout the Southwest.

Attorneys for Amicus are counsel in cases from

Austin, Houston and Dallas, Texas.32 Other pending

litigation involves California cities such as Los

Angeles and San Francisco.33 Equal educational op

portunity in America’s cities requires desegregation

81Distinetions based on. race and ethnicity are the archtypical

classifications subject to the strict equal protection standard.

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192 (1963). Loving v. Vir

ginia, 388 U.S. 1, 9 (1967). See McDonald v. Board of Election

Comm’rs. 394 U.S. 802, 807 (1969).

“And a careful examination on our part is especially war

ranted where lines are drawn on the basis of wealth or race,

two factors which independently render a classification

highly suspect and thereby demand a more exacting judicial

scrutiny. ”

32Austin, U.S. v. Texas Education Agency, supra, Houston,

Boss, Rodriguez U.S. v. Eckels, supra, Dallas, Tasby v. Estes,

supra.

83Crawford v. Los Angeles Unified School District, Superior

Court of Los Angeles, California, No. 822854; and Johnson v.

San Francisco Unified School District, U.S. District Court for the

Northern District of California, No. C-70 1331 SAW (1971).

25

plans which realistically take account of their ethnic

ally diverse character.

E. The Trial Court Correctly Ordered a Program For Equali

zation of Educational Opportunities

Both apart from and ancillary to the issue of de

segregation, this Court should reinstate the District

Court’s order requiring the equalization of school

facilities in which racial and ethnic minorities are

concentrated. The record is clear that these schools

are inferior to the Anglo schools, and this inequality

is attributable only to action by the defendant district.

As the Fifth Circuit noted in U.S. v. Jefferson Go.,

380 F.2d 385, 393-4 (5th Cir. 1967), the equalization

of school facilities is an essential precondition to

effective: desegregation. But if this Court should hold

that Chicano schools need not be desegregated, equal

ization of schools becomes all the more crucial—

indeed, it then becomes the only hope for the district’s

Chicano children to receive a decent education.

The District Court approved a program which con

tains at least the following:

“1. Integration of teachers and administrative

staff;

2. Encouragement and incentive to place skilled

and experienced teachers and administrators

in the core of city schools;

3. Use of teacher aides and para-professionals;

4. Human relations training for all School Dis

trict employees;

5. In-service training on both district-wide and

individual school bases;

26

6. Extended school years;

7. Programs under Senate Bill 174;

8. Early childhood programs such as Head Start

and Follow Through;

9. Classes in Negro and Hispano culture and his

tory; and

10. Spanish language training.” (313 F.Supp. at

99.)

Spanish language training is crucial to development

of a Spanish speaking child. If the language and

culture that he brings to the school are rejected, his

self-esteem and subsequent ability to succeed in school

are adversely affected.34 The use of teacher aides and

para-professionals is of great benefit in implemen

tation of these Spanish language programs.

The Court of Appeals reversed the District Court’s

equalization order in reliance on a resolution of the

defendant board (445 F.2d at 1010). This was error.

The constitutional rights of minority students should

not depend on the good faith, of a school board proven

to have discriminated. Furthermore, the order of the

District Court, is much more particular than the reso

lution and provides specifically for programs for

Chicanos. Finally, the school board’s plan is not, really

a plan at all because it is dependent on the vagaries,

of the finances of the school district.

34Congress has recognized the need for these types of language

programs. Bilingual Education Act, 20 U.S.C. Section 880.

27

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, Amicus Curiae prays that this Court

grant the relief requested by the Petitioners and

reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeals insofar

as it reverses the judgment of the District Court and

remand the, case to the District Court with instruc

tions, that, it institute a comprehensive desegregation

plan for the Denver school system.

Dated, May 4, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

M ario Gr. O bled o ,

M ic h a e l M e x d e l s o n ,

A l a n E x elr o d ,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.