Memorandum in Support of Motion

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum in Support of Motion, 1970. faf0407a-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/6d0353cc-08fa-46ea-bd3e-aa8375a95e03/memorandum-in-support-of-motion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

#

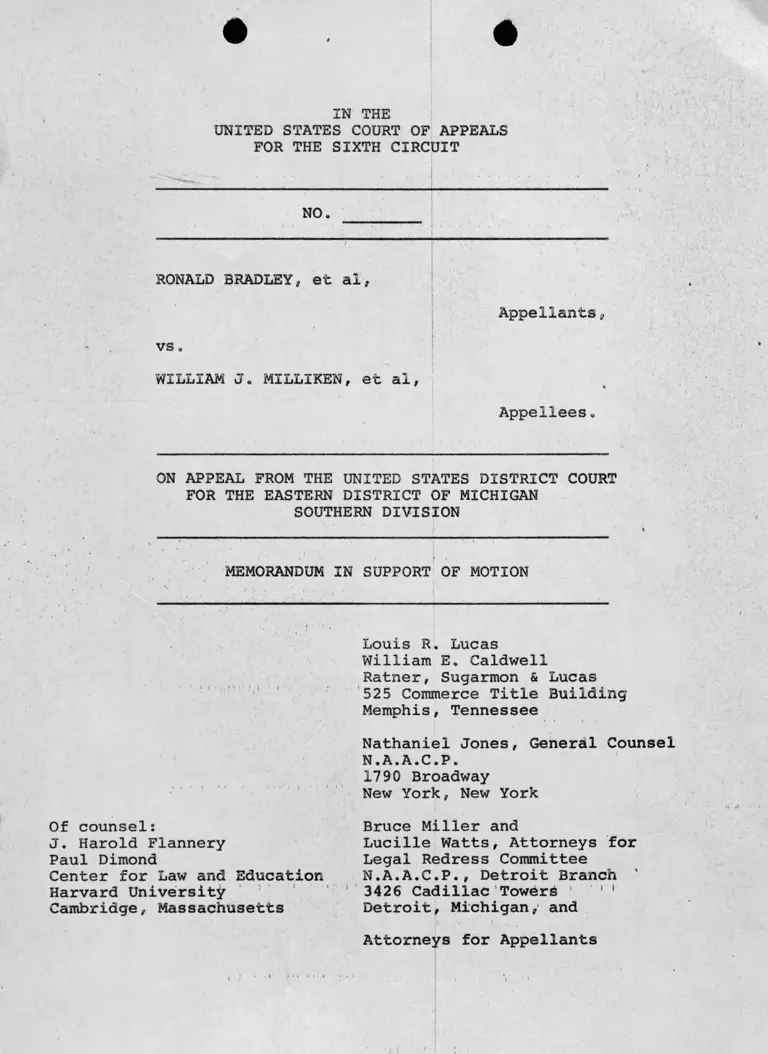

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD BRADLEY. et al

vs.

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, et al,

Appellants

Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION

Of counsel:

J. Harold Flannery

Paul Dimond

Center for Law and Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Louis R. Lucas

William E. Caldwell

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York

Bruce Miller and

Lucille Watts, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Towers 1 1 1

Detroit, Michigan,' and

Attorneys for Appellants

\

• •

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

' 'V • ;; ‘ ‘ ' . ' ■ Appellants,

V S o

WILLIAM J. MXLLXKEN, et al, *

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

■ ■ • • .................... t : 1 •• . . . . . .

! ' 1 ■ ’ I

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION

Plaintiffs sought by an application for a preliminary injunc

tion in the District Court below to enjoin the provisions of an

act of the Michigan legislature which prohibited the Detroit,

Michigan City Board of Education from implementing1 & plan of high

school desegregation adopted by it on April 7, 1970„ Plaintiffs

sought an acceleration' of1 that plan Of desegregation and modifica

tion of certain features - faculty desegregation for the entire

school system, and an injunction against any new construction pend

ing the adoption of a complete plan of desegregation for the entirei ■ i { *; i _ ■ | i * i • 1 ! ' ■' ,

system- ' ! ‘ ' 1 1 1 ‘ 1 ■

;

Plaintiffs here seek by way of an injunction pending appeal

for the purpose of preserving their rights and the jurisdiction

of this Court over the issues raised by their appeal an injunction

vacating the legislative stay passed by the Michigan Legislature

following the adoption of the plan of desegregation by the Detroit

Board and reinstatement of the status quo insofar as plaintiffs5

rights are concerned, that is, the plan adopted by the Board, which

would tend no eliminate a pattern of segregation in twelve Detroit

high schools„

Rule 8 (a) of the Federal Rules of Appellate procedure provides

that the application for such relief may be made to the Court of

Appeals or to a Judge thereof. The rule requires a showing by the

moving parties that the District Court has refused to grant the

relief requested and the reasons given by the District Court for

1 ! , I I j ' I ■ ' ' ' i 1 I . 1 1 ! M r ' | I ! I ! I * 1 , |

its action. This specific relief was requested of the District

I I ' , ' i ! ■ 1 I V 1 , • I ! ■ I • ■ : i ,

Couru. A copy of the Court*s decision denying the application for

i ■ i ' i 1 i 1 1 1 ; ' ; , > I . ■ i . ! ’ i i ' '

preliminary injunction is attached. (App. 134) Unfortunately, the

1 : : ■ ' 1 : ! < 1 I ! ! ■ : s ■ . . : I ■ • • I ' I ' - 1 ‘ ' *

District Court does not substantially avert to the constitutional

• ‘ 1 ' ' • ’ j • 1 • : 4 ► 1 - f •

defects of the action of the Michigan Legislature nullifying an- . : i ' ‘ : • 1 1 ' J i 1 1

action of the Detroit Board of Education and interposing itself by

■ > • ■ ■ • i i • i , i , t i i i » • •

way of a legislative stay between the Board and plaintiffs.

i . 1 1 ' . '

In unis case, the Court of Appeals will not be in formal

i i >

session until substantially after schools have opened for the... , . I I ; I . I * ' • 1 ‘ - ■ ! »

1970-71 school term. Wherefore, plaintiffs have made their appli-

cation to the Chief Judge of this Court.; 11.;! ! ! i i t i > (•••!■» * • ■' • ! ■ • • > i t , . i i

i I i i i i i i ii.-- i i 1 i

• i 11; • i ■ i i i i i • i i i

i

2

l

4 ; < |m .

A judgment or a decision denying a motion for preliminary

injunction is an appealable order. 28 U.S.C. 1292(1). This Court,

or a single Judge thereof, has the power to issue all writs neces

sary or appropriate in aid of its jurisdiction and agreeable to

the usages and principles of law. 28 U.S.C. §1651 (a). An injunc

tion pending appeal is such a writ. Aaron v. Cooper, 8th ^ir., 2oi

F.2d 97, 101. The power granted to courts of appeals under §1651,

commonly known as the "All Writs" statute, is meant to be used

only in exceptional cases where there is clear abuse of discretion

or usurpation of judicial power. Bankers Lire & casualty company v «

Holland, 346 U.S. 379.

It is generally held that a trial court abuses its discretion

when it fails or refuses properly to apply the law to conceded orj I I 1 i I ■ ' I I ' ! ' 1 ’

undisputed facts. Union Tool Company v. Wilson, 259 U.S. 107, li2.

Misapplication of the law to the facts is in itself an abuse of

discretion. Hanover Star Milling Company v. Allen and Wheeler--- -------——;----:---- ; i i ; : ' ' '

Company, 7th Cir., 208 F.2d 513, 523. Clemons, et al, v. Board of

Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, et al, 6th Cir., 228 F.2d 853, 857.

------ ------------ ---------------!--------- '■ - ■ 1 ------- -------- -----------,

United States v. Beaty, 6th Cir., 288 F.2d 653, 656 (1961).--- --- r-n---r-r—!— I — , | ! i • • 1 1 ' .

The Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873, said

; . ■ '

"We conclude that in the field of public education

the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently

unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs

and others similarly situated for whom the actions

have been brought are, by reason of the segregation

complained of, deprived of the equal protection of

the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment."

I M

, I f i i i f

} i

} i ,

The existing segregation of the schools is detailed in the

motion which quotes statistics from the testimony of Superintendent

Drachler. Also, the admissions of the defendant made in the Citizens

Committee study, reaffirmed with examples in the testimony of the

Superintendent, also a defendant in this cause, establishes a clear

underlying base for a finding of acts in the maintenance of a

pattern of segregation in the Detroit school system, which pattern

is yet to be overcome. However, it is not necessary for the Court

to reach those issues in order to find the Michigan legislative

interposition and nullification of the Board9s plan and preventing

its implementation an unconstitutional form of state action perpet

uating and maintaining segregation as it currently appears in those

schools. In Keyes v. School District No. One, Denver, Colorado,

313 F.Supp. 61 (1970) the Court discussed the rescission of a

previous board5s plan to take action for the purpose of preventingI ’ ' ' ! 1 ‘ ’ ’ i t ' [ ■■ I . '

the ultimate segregation of certain schools in the City of Denver,

the Court having previously refused to act with respect to those

schools. The Court stated the proposition as follows:* ' • » t

"It perhaps looked to ultimate desegregation.

We must hold that this frustration of the board i ! :

plan which had for its purpose relief of the

effects of segregation at the polls was unlaw

ful. Resolutions 1520 and 1524, as they apply

to East and Cole, should be implemented.

"In reaching the above conclusion we have very

carefully considered both the majority and

minority opinions in the nbw famous Supreme Court

decision in Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 87

S.Ct. 1627, 18 L.Ed.2d 830 (1967$, and have " "■ 1 ■

concluded that both opinions fully support the

position which we have taken. ■ , 1

4

i f t ? *

• t

1 ' i < i

* I

"It will be recalled that Mulkey, like the case

at bar, had to do with the repeal of legislative

acts which recognized rights guaranteed by the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

"Our case is like Mulkey in that it also involves

repeal or rescission of a previous enactment

which extended and upheld nondiscriminatory rights.

Our case is stronger than Mulkey in that there the

statute was brought to bear on private transactions.

Here, on the other hand, there could be no question

about whether it is the state which is discriminat

ing .

"It cannot be argued in the case at bar that the

legislative action of the school board was neutral.

The board specifically repudiated measures which

had been adopted for the purpose of providing a

measure of equal opportunity to plaintiffs and

others. The school board action was, to say the

least, not neutral and the causal relation between

the school board action and the injuries is

direct. We find and conclude then that Mulkey

\ not only supports our position, it is a compelling

authority in support of the conclusion which we

have reached. It is so closely analogous that we

would be remiss if we failed to follow it."

In Keyes, the Court was faced with the necessity of drawing

...................... » ! • » , i !

the conclusion that the action of the newly elected school board

* ' ‘ ■ ‘ : I ‘ ‘ ‘ \ 1 t : ' i i i *

in rescinding a previous board8s plan constituted a legislative

1 , ' ‘ ' ' , I 1 ! ,■ 1 I

1 » 1 . ' 'act and was therefore state action prohibited under the Fourteenth

: « i .

Amendment. Here no such link in the chain of logic is necessary.

The state by legislative act has specifically interposed and

reversed a board-adopted plan to provide equal educational opportunity

by desegregating twelve high schools in the system.

In a somewhat analogous situation, the Fifth Circuit Court of1 I ! < 1 l 1 I i

Appeals acting under the 88All Writs88 statute, directed the District

I i i : i • (

rii t i I I

! .: , m i ■ • i i : ! i

* . . I . ■ ! 1 it . '

Court to issue an injunction, the terms of which were spelled out

in the opinion of the Court of Appeals. As here, the school board

had adopted a voluntary plan to desegregate to some extent the

schools in its system. Its voluntary plan of desegregation was

stayed as a result of the temporary restraining order the District

Court had granted at the request of white parents who sought to

prevent the Board of Education from going forward with its

voluntary plan of desegregation. The Court of Appeals said:

if"We have the power to grant any necessary relie:

to prevent irreparable damage to the minor

appellants. Title 28 U.S.C.A. §1651. The pre

trial order is also a final order within the

meaning of 28 U.S.C.A. 1291 in that it determines

substantial rights of the six minor Negro

children and these rights will be irreparably

lost if relief is delayed pending final judgment«

See United States v. Wood, 5th Cir., 1961, 295

F.2d 772, 778; cert, denied 369 U.S. 850, 82 ! «

S.Ct. 933, 8 L.Ed.2d 9; Kennedy v. Lynd, 5th Cir.,

1962, 306 F.2d 222, 228; Hodges v. Atlantic

Coastline Railroad Company, 5th Cir., 19*>2, 310

F .2d 438, 443. ' ‘ ‘ 1

' "Under the school segregation cases, Brown v .

Board of Education, 1954, 347 U.S. 483 [citations

omitted] 349 U.S. 294 [citations omitted]; Cooper

v. Aaron, 1958, 358 U.S. 1, the irreparable damage

being sustained by appellants consists of being 1 ‘

forced to attend a racially segregated school.

No comparable injury will be suffered by the

appellee-plaintiffs if the motion for injunction

pending appeal Is granted. Harris v. Gibson, 322

F .2d 780, 5th Cir., 1963.

The Court went on to require that the injunction be issued

against uhe school board despite the fact that the matter arose

out of the adoption of a voluntary plan.

.. . , ■ . - . > i i > ! * i 1 ' I 1

It follows from what we have said that an injunc

tion pending appeal should be granted. This will

'

H

\ • ; ! 1 M f J

» »

also solve the dilemma of the school board

caught as it is between its own voluntary plan

and the preventive order of the District Court

as expressed in their request for direction.

322 F.2d 780, 782.

To the same point the Court in Lee v, Macon County Board of

of Education, 231 F.Supp. 743, 1964 (three judge District Court)

stated that

"the evidence in the case reflected that the

Macon County School Board and the individual

members thereof, and the Macon County Superin

tendent of Education, have throughout this

troublesome litigation fully and completely

attempted to discharge their obligations as

public officials and their oaths of office.

It is no answer however that these Macon County

officials may have been blameless with respect

to the situation that has been created in the

school system in Macon County, Alabama. The

Fourteenth Amendment and the prior orders of

this Court were directed against actions of the

State of Alabama; not only the action of County

school officials, but the actions of all other

officials whose conduct bears on this case is

state action. In this connection see Cooperv.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1401, 3 L.Ed.2d 37

1958, where the Supreme Court of the United

States, among other things, discussed the

contention advanced by the Little Rock, Arkansas

school officials that they were to be excused

from carrying out the prior orders of the Court

by reason of conditions and tensions and dis

order caused by the actions of the governor and

the state legislature." 231 F.Supp. 743 at 752.

As it was in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, a case in the Fifth Circuit, 318 F.2d 425, 1963, it was in

Detroit, Michigan in 1970, a clear abuse of the trial court*s

discretion to deny plaintiff-appellants8 motion for preliminary

injunction requiring the defendant school board to make a prompt

and reasonable start toward desegregation of its schools.

'. ’ ' ' i! ‘ . , I _ , !; ■' I ' i | . !:' • I I , I ! • |

These cases which we have cited to the Court involving

.

preliminary injunctive relief through the action of the Court of

Appeals all arose in the context of the "deliberate speed" doctrine

since replaced by the United States Supreme Court in Alexander v .

Holmes County, 396 U.S„ 19 (1969) , with a clear doctrine of

%

immediacy. Here unless this Court acts to require the implementa

tion of the Board’s desegregation plan* members of the appellants®

class will be denied their constitutional rights for yet another

school term or longer. In McCoy v. Louisiana State Board of Educa

tion , 332 F.2d 915 (1964) 5th Cir. , the Court ordered action to be

taken because of the pendency of the summer school term. See also

Woods v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir., 1964). With respect to

a contention that administrative problems might arise if changes

■ : ; . * 1 , | ! I I i i . 1 . . I | | j ;

are made at this date in the operation of the school system, it isi i i ; i ■ ■ . 1 ! t

sufficient to point out that the courts have repeatedly held that

* ' 1 ‘ . : ; . ? . < i i i v ' y

administrative problems are not those created by the plaintiffs.

Historically, plaintiffs in this cause have sought desegregation

’ . . : " , i , t . . . . I • ' • ! ( * ( I

in the Detroit school system, as reflected in the minutes of the

• l '< j • ! . 1 i , , . ■ . . • . • f ; ■ ; S * - i , t •

Board of Education. The desegregation process would have been

• 1 | ‘ ■ ! . , | , i | > . , . < ( • *

begun, although in a small way, at twelve Detroit high schools but‘ ’ ’ •:'■■■! i • !* : ■ 1 , I . i (■ ,

for the action of the Michigan legislature in passing Act 48. In

, i . . . . . . ♦ • . * • • ( * * ■ *

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, Alabama,

332 F.2d 356, 358 (5th Cir., 1963) the Court was faced with the

» ■ , J . . , < - i , • ‘ »! ‘ ■ ’contention that the trial date, as the trial date here, was fixed; , i . <, . i . ’ 11 i < t ; i ’ * 1 ’ ’ 1. • * 1 >

in November and it saids

> I : - , f rr i ■ , i I i • i ■ . | • i 1 I I is > • ‘ 1 i i • . > • • 1

■ . ' ■ i ’ :: '

i ■ f i i . ; , ! . ! . • • >. 1 i . • .• . ■ . • i • • j I • !. • ! 1 . . ! • ■ i ,

I I I • I , , , I • i , . 1 > 1 • . 1 f ■ , « . 1 ) 1 I , . I I i . |’ 1 i I ■ 1

I ' • V

I .

: , I : • I i j | > | ■ I i. i i i * ! g < ' 1 ! 1 i i ;• ! i i -It I ’ 1

"With the trial date now fixed in Novembers, it

seems that effective relief is denied for another

school year with no assurance that even at such

later date anything but a reaffirmation of the

teachings of the Brown decision will be forth

coming . "

The Court in Davis also pursuant to the "All Writs" statute in the

exercise of the appropriate jurisdiction, proceeded to order the

*

District Court for the Southern District of Alabama to enter an

order for an immediate start of the desegregation of the Mobile

schools.

With respect to the uncontroverted evidence of acts which

tended to establish and maintain a pattern of segregated schools

in Detroit, referred to above, Superintendent Drachler admitted a

number of examples of discriminatory acts on the part of the Detroit

Board. These acts, as more fully set forth in the Motion, are:

The Detroit Board has in the past utilized such discriminatory

techniques as optional attendance zones (Tr. 142-43), intact busing

(Tro 139-40). busing of black children past white schools with

I ; . I , , i ' i .i ’ ' ■ . i i ■ ! , ■ " i I i I 1 i 1 • t I , t ; ,

available space (Tr. 141-42), gerrymandering zone lines (Tr. 143-44) ,

* I I , | i *» I t , ’ • > • • 1 ‘ j •• f ' ' • I

and "open enrollment" or "free transfer" provisions (Tr. 50-52) , all

in a manner which created and perpetuated segregated schools., Also

uncontroverted in this record is the fact that at least as late as

1961 the Detroit system utilized a racially discriminatory policy• ... • M • ‘ 1

and practice of faculty assignments to the effect that there was

a pattern of white teachers assigned to white schools while black

c . i i . i * i , ! 1 I • ' ! ' 1 I

teachers were assigned only to black or racially mixed schools

, , , ! ! ! , I i I , I . , . , ' ■ i ' ■' , ■’ l l I ' ‘ ' ' I I 1 > 1 ' ‘ 1

(Tr• 133-35)v This proof, taken together with the 1969 statistical

i ' i ■ i i •, 1 !' i t / . , •. i • i 1 i ! i | - i , I , , t

. V

t ■ , . .1 i . . , ! I I ■ , I ' . I » ,•* ' ’ ‘ , ! 1 ' 1 1

i : 1 • i ■ I . ' i i i • i i i i i i . ' i ' 1 i i

data showing 62.8 percent of the pupils in the system in schools

over 90 percent one race or the other and the fact that, while the

faculty is 38.4 percent black system-wide, there are 56 faculties

less than 10 percent black {47 of them in schools over 80 percent

white) and 61 faculties over 60 percent black (all 61 of them in

schools over 90 percent black), is although not necessary for a

decision on the Motion, evidence of a racially segregated school

system. This evidence stands in the record without contradiction.

The record reflects testimony from the defendant Board that the

desegregation plan was adopted to provide equality of educational

opportunity, to desegregate the high schools involved? that the

act of the legislature was passed with the intention and purpose

of "turning back the page" on the Board's efforts to begin desegre

gation and that it was Act 48 which prevented and continues to

prevent the implementation of the Board's plan. All of this testi-

’ ' * - ! • • . * • - ? ' . » 1 *

mony remains uncontradicted. Again, the testimony remains uncontra

dicted that little or no additional pupil transportation will be

* t i » , ■ ! f I

required, that there are no physical plant reasons why the plan

• > . j . . i 1

cannot be implemented at once (Tr. 310-312), and that the plan

would require only a brief administrative period to implement.

i ' , 1 ; i , . 1 i • i I ’ 1 i . : i 1 i ' I i ! ■ ' ' .

It is the obligation of every school system to desegregate• , l ! • r , i ! 11 i . . i 1 ‘ < : '

its schools "at once and to operate now and hereafter only unitary

| • , , ' • . ■ I ■ ' < i

schools." Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969).

This obligation is to be carried out, insofar as there is a plan

! > 1 • • ; ■ , ; I I I . . i ! 1 • • i •* i • i ' 1 I 1 ' I I i

in existence (e.g., the Board's April 7 plan), pending (not follow-

ing) litigation. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,

i i i ■ ■ • ' ■ • ■ 1 • ' ■ . . -

> i . . . i .. . . i , i , . , , , . , t » ' . t . • ; ' . i ! ‘ ■ f 1 1 ■ i 1

i . , i ; : : ' . • | 1 ’ • '

10

I t i l i l t I I I .................. I. * . i t I I I i . i t . . . I I I i I • - f : ! I

i

396 U.S. 290 (1970) . As the Fifth Circuit has held with regard to

existing HEW plans: "Because the tenor of ... [Alexander and

Carter] is to shift the burden from the standpoint of time for

converting to unitary school systems from a status of litigation

to one of unitary operation pending litigation, we have, in the

past, ordered immediate implementation of the HEW plan despite

defects it might have where it was the only plan in the record

which currently gave any promise of ending the dual system. See,

United States v. Board of Education of Baldwin County,

F-23 ____ (5th Cir., No. 28,880, March 9, 1970)." Andrews v. City

of Monroe, ____ F.2d ___ , No. 27358 (5th Cir. 1970) (Slip Op. 6-7).

Accord, Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Ed., 418 F.2d 1040 (4th

Cir. 1969)(en banc).

' ) I . 1 ! ! i ' , . i ' , ,

The constitutional obligation to operate schools which are

' • •. : • ■' } ' . . : . • I

• • - I ? ! '

not racially identifiable is imposed upon every school sysuem in

* ' • ' ' . r ; i ; , r , i ,

the United States.

As stated by the Court in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg case,1 * ' 1 > • • • i j ■ *11 i i i 1 • i ■ ’ i ■ i ■ . f i , i 11 .

quoting the first Brown decision:

i i . i , i ; ----------- :------

i • ■ ! » 1 I i '

"We conclude that in the field of public educa

tion the doctrine of 3 separate but equal9 has

no place. Separate educational facilities are

inherently unequal ... (emphasis added). ...

" ••• such segregation has long been ‘a nation-' .

wide problem, not really one of sectionaT

concern7*"! ' (emphasis added) . * r 1 '' . ' ■ > • - 1

The selection of cases for the Brown decision demonstrates

the nationwide reach of that concern; Brown lived in Kansas

and the defendant Board of Education was that of Topeka, !

Kansas; defendants in companion cases included school

authorities in Delaware and the District of Columbia.

' I ’ • • ' • ' i ' ' I 1 I ■ ' ‘ I i t 1 r • j t i i I I I ■ . . ■ | . I , H t ' < • 11 - I ' | | ( ' , h , , < .

■ 1 ' I ' ' 1 1 1 I 1 l« * > • i • I ‘ • ! i •"! • ■ ■ ■ 1 M I M I • • . ' • ) ! > ! | , • ,,; . I .

11

♦

Later important cases have involved not just southern

schools, but also schools in New York, Chicago, Ohio,

Denver, Oklahoma City, Kentucky, Connecticut and other

widely scattered places.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 306 F.Supp.

1299, 1309-10 (W.D. N.C. 1969). See also, Keyes v. School District

No. One, Denver, 303 F.Supp. 289 and 298 (D. Colo. 1969), preliminary

injunction stayed (10th Cir. 1969), stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215

(1969); Crawford v. Board of Educ. of Los Angeles, No. 822-854

(Superior Ct. Calif. Feb. 11, 1970); Berry v. School Dist. of the

City of Benton Harbor, Civ. Act. No. 9, (W.D. Mich. Feb. 3, 1970)

(oral opinion); Davis v. School Disc, of the Cxty of Pontiac, 309

F.Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. Feb. 17, 1970)? United States v. School

Dist. 151 of Cook County, 111., 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968),

affirming 286 F.Supp. 786 (N.D. 111. 1968).

"[Ijn 1954 the Supreme Court was dealing not just with a

multiracial community but with a multiracial nation and dealing

with segregation ... IT]he Supreme Court was dedicated ootn educa

tionally and constitutionally that where Negro students dad to

attend ma ority Negro scnools or al^ Negro schools t*.ey were

being deprived of an educational opportunity to fulfill &ix of

their dreams, at least m this country." (Spongier v. Paoadena

City Board of Education, No. 68-1438-R (C.D. Calif. Jan. 20, .̂970)

(oral opinion at 2400) . Therefore, the obligation of every school

system i. the nation is to establish "a system without a 'white*

schoo. and a ’Negro' school, but just schools." Gigc.i v. ounty

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 442 (1968). The obj active ii aonooi

12

♦

system without schools which are racially identifiable. Kemp v .

Beasley, No. 19,782 (8th Cir. Mar. 17, 1970) (per Blackmun, J.);

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, No. 19,795 (8th Cir.

May 13, 1970) (en banc); Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir.

1968); Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, No. 14,335 (4th

Cir. June 17, 1970); Whitley v. Wilson City Bd. of Educ., No.

14,517 (4th Cir. May 26, 1970).

CONCLUSION

Unless this Court acts, the personal rights of each Negro

child affected directly or indirectly by this plan will be effec

tively denied for at least another term. The injury is irreparable

and the denial of equal educational opportunities recognized by

the defendant Board.

Unless this Court acts, the issue for this semester and

possibly the entire year may become moot, thus depriving this Court

of jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court said in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S.

526, 535 (1963): "The rights here asserted are, like all such

rights, present rights; they are not merely hopes to some future

enjoyment of some formalistic constitutional promise (Emphas:

in original). Plaintiffs respectfully submit that where the trial

court has refused properly to apply the law to the conceded or

, ' s t , i ! I -

undisputed facts and permitted almost without comment a section of

\

a legislative act which, from the proof in this record, had no

other purpose than a racial one to continue to stay the implementation

i

1 i ; < I

13

4i

of a starr on high school desegregation. The intervention of

this Court is required to preserve its jurisdiction and prevent

irreparable injury and manifest injustice.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis R. Lucas

William E. Caldwell

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York

Bruce Miller and

Lucille Watts, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan, and

Attorneys for Appellants

a . t i ■ ' ■ ■ ■ ■ •

i • i . ..

i n i •

* • i i t > f m r *

j »

* • i i ' ! ■ I • • I A l l I 1 I

i . •; i

i * ! /

Of counsel:

J. Harold Flannery

Paul Dimond

Center for Law and Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

14